Abstract

This study presents a novel federated learning (FL) methodology implemented directly on STM32-based microcontrollers (MCUs) for energy-efficient smart irrigation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to demonstrate end-to-end FL training and aggregation on real STM32 MCU clients (STM32F722ZE), under realistic energy and memory constraints. Unlike most prior studies that rely on simulated clients or high-power edge devices, our framework deploys lightweight neural networks trained locally on MCUs and synchronized via message queuing telemetry transport (MQTT) communication. Using a smart agriculture (SA) dataset partitioned by soil type, 7 clients collaboratively trained a model over 3 federated rounds. Experimental results show that MCU clients achieved competitive accuracy (70–82%) compared to PC clients (80–85%) while consuming orders of magnitude less energy. Specifically, MCU inference required only 0.95 mJ per sample versus 60–70 mJ on PCs, and training consumed ∼70 mJ per epoch versus nearly 20 J. Latency remained modest, with MCU inference averaging 3.2 ms per sample compared to sub-millisecond execution on PCs, a negligible overhead in irrigation scenarios. The evaluation also considers the payoff between accuracy, energy consumption, and latency through the Energy Latency Accuracy Index (ELAI). This integrated perspective highlights the trade-offs inherent in deploying FL on heterogeneous devices and demonstrates the efficiency advantages of MCU-based training in energy-constrained smart irrigation settings.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the deployment of machine learning (ML) models on resource-constrained embedded systems has evolved from a conceptual vision to a tangible reality. With the emergence of frameworks such as TensorFlow Lite and PyTorch (version 2.1.0) Mobile, it has become feasible to execute ML inference directly on ultra-low-power microcontrollers, enabling real-time decision-making at the network edge. This evolution, known as Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML), represents the integration of ML capabilities into MCU-class hardware, opening new opportunities for the Internet of Things (IoT) [1,2]. TinyML promises low latency, improved responsiveness, and enhanced data privacy—key requirements for pervasive systems such as smart agriculture (SA), environmental monitoring, and wearable technologies [3]. Despite these advances, the dominant TinyML workflow follows the conventional “train-then-deploy” paradigm, in which models are trained offline on high-performance servers and subsequently deployed to embedded devices for inference [4,5]. While this approach benefits from flexible architecture design and high initial accuracy, it fails to address evolving data patterns, device heterogeneity, and personalization needs. The resulting models degrade over time, making them unsuitable for long-term autonomous applications in dynamic environments. To overcome this limitation, recent research has explored on-device learning, where model adaptation occurs directly on embedded devices [6]. When combined with Federated Learning (FL), on-device learning enables distributed and privacy-preserving model updates without the need to exchange raw data [7]. FL allows each client to perform local model training and share only model parameters with a central aggregator, which produces a global model through iterative averaging. This paradigm has demonstrated promise in domains requiring privacy preservation, such as healthcare [8] and finance [9], as well as in mobile personalization tasks [10]. However, most existing FL implementations rely on simulated clients or relatively powerful edge platforms such as Raspberry Pi or Jetson Nano [11,12,13], which do not accurately reflect the severe computational and energy constraints of real IoT nodes. In agricultural contexts, sensor networks measuring variables such as soil moisture, temperature, and humidity have transformed irrigation and crop management strategies [14]. Yet, these systems typically operate in remote areas characterized by intermittent connectivity, limited energy budgets, and environmental heterogeneity. Centralized ML approaches are impractical under these conditions because they depend on continuous cloud connectivity, leading to excessive energy consumption and potential privacy concerns [15]. Furthermore, agricultural data are inherently non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID), varying with soil composition, crop type, and microclimate, which complicates centralized model training.

To address these challenges, this work proposes an on-device FL framework for smart irrigation that executes entirely on constrained IoT hardware. The framework leverages microcontroller class devices such as STM32—as representative low-power platforms capable of performing both local training and collaborative aggregation under realistic resource limitations. This design emphasizes privacy preservation, reduced communication overhead, and energy efficiency as essential criteria for scalable agricultural intelligence.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Development of a fully functional on-device FL framework designed for microcontroller-class devices, enabling collaborative learning across heterogeneous, non-IID datasets under stringent hardware constraints.

- Comprehensive evaluation of trade-offs between model accuracy, latency, and energy efficiency by comparing constrained devices with standard computing platforms under identical FL configurations.

- In-depth discussion of key system-level aspects—including energy management, communication efficiency, and data privacy—that influence the deployment of FL in energy-limited smart-agriculture environments.

This study demonstrates the feasibility of performing FL directly on ultra-low-power embedded devices for intelligent irrigation management. By enabling collaborative training within constrained IoT networks, the proposed framework contributes to the broader development of sustainable, adaptive, and privacy-preserving digital agriculture. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the state-of-the-art on FL in IoT and SA. Section 3 describes the proposed FL framework, including the hardware and software setup, dataset details, and system architecture. Section 4 discusses the implementation of the Federated Training process, including the communication setup and training procedure. Section 5 presents the evaluation of the FL framework, including the analysis of inference time, energy consumption, and model performance across different scenarios. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future directions.

2. State of the Art

FL has been established as a decentralized ML paradigm in which a global model is collaboratively trained across multiple devices without requiring the exchange of raw data [16]. This design provides notable benefits in terms of privacy preservation and communication efficiency, making it suitable for distributed IoT systems. FL has been successfully applied in various domains, including mobile computing [10], healthcare [8], and finance [9]. Nevertheless, the deployment of FL on real-world embedded systems is constrained by challenges such as heterogeneous hardware configurations, non-IID data distributions, and severe resource limitations in terms of memory, energy, and processing power [17]. While numerous FL implementations have been proposed, many assume stable operating conditions or powerful edge devices. For example, Bonawitz et al. [18] presented a scalable and secure FL protocol designed for smartphones, but the framework relied on consistent power and sufficient memory assumptions unsuitable for MCU-class hardware. Mwawado et al. [11] extended FL to environmental monitoring tasks using Raspberry Pi boards. However, the computational and memory resources of Raspberry Pi devices exceed those of typical ultra-low-power embedded systems. Sikiru et al. [19] explored FL in the context of smart farming, but the study was restricted to simulations and lacked real-world implementation on physical MCUs. This gap between theory and practice limits the generalizability of their findings, particularly in harsh deployment environments with unreliable connectivity and tight energy budgets. Wu et al. [20] introduced FedLE, an energy-aware client selection framework that extends device lifespan during FL rounds. Valente da Silva et al. [21] proposed an FL Distillation Alternation (FLDA) mechanism that alternates between local training and model distillation to reduce communication cost and energy consumption. Although both works tackle energy efficiency and communication optimization, they assume relatively capable IoT hardware and omit evaluation on microcontroller-class devices. Their frameworks remain simulation- or edge-computer-based, leaving open the feasibility of full FL training under strict energy and memory constraints. Off-device training remains the predominant method in most TinyML applications, where models are trained on powerful machines and later quantized and pruned to fit embedded devices [22]. While effective for inference, this static deployment model limits adaptability, making it unsuitable for systems requiring continual learning. Disabato and Roveri [23] proposed an incremental transfer learning approach on STM32F7 and Raspberry Pi 3B+ platforms. Despite demonstrating feasibility, their method relied on pre-trained feature extractors and did not support full training on-device. Kopparapu et al. [24] introduced TinyFedTL, a federated transfer learning framework for Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense boards. By updating only the output layer of a compressed MobileNet, training costs were reduced, yet full model training was not performed. Furthermore, simulation-based evaluations limited insights into real-world constraints such as energy consumption and inference latency. Mathur et al. [25] leveraged the Flower framework to perform on-device FL on Raspberry Pi and Jetson Nano boards. Although on-device training was executed using TensorFlow Lite, the high-end nature of the hardware used makes the findings less applicable to MCUs with minimal memory and no operating system. In parallel, Deng et al. [26] developed a leakage-resilient aggregation protocol that integrates differential privacy and carbon-neutral compression to enhance FL security and energy efficiency. However, this method is designed for large-scale or high-power systems and does not address the unique limitations of MCU-based deployments, where both computation and communication resources are extremely constrained. Despite meaningful advances in prior research focusing on energy-aware optimization, communication reduction, and privacy-preserving aggregation, none have demonstrated a fully on-device FL framework operating entirely on microcontroller-class hardware in real agricultural settings. Existing studies generally rely on simulations or high-end edge platforms, optimizing algorithms without addressing the practical limitations of embedded systems characterized by restricted energy, memory, and computational resources. This leaves a critical research gap at the intersection of energy efficiency, communication reliability, and embedded learning, particularly under the non-IID and harsh conditions typical of agricultural environments. To address this gap, our work presents a fully implemented and experimentally validated on-device FL framework on STM32F722ZE microcontrollers. In contrast to prior research that either depended on more capable platforms (e.g., Raspberry Pi, Jetson Nano) or limited training to transfer-learning layers, our approach demonstrates full model training on devices featuring only 276 KB of RAM (256 KB SRAM + 16 KB ITCM + 4 KB backup SRAM) [27] and operating without an OS, reflecting realistic embedded constraints. Each MCU is assigned to a unique soil type and participates in synchronous FL rounds using real sensor data, with model updates exchanged via the MQTT protocol. System performance is empirically evaluated in terms of accuracy, latency, and energy consumption, providing practical insights into the feasibility and efficiency of FL for constrained agricultural environments. Table 1 summarizes prior research and highlights the novelty of our contribution in terms of hardware deployment, training strategy, and experimental validation.

Table 1.

Comparison of existing FL approaches on embedded or edge devices.

3. System Design and Methodology

3.1. Overview of FL Framework

In this work, an FL framework was implemented to evaluate the applicability of FL in resource-constrained environments, particularly in SA applications. The framework involved multiple STM32F722ZE MCUs as client devices, each responsible for training a model on a unique data domain based on soil type, derived from the SA dataset. This FL setup allowed for decentralized training, ensuring that sensitive data remained on the local devices and never left the premises, thus maintaining data privacy.

The key components of our FL framework are as follows:

- Central Server: The central server coordinates the training process by broadcasting the global model to all clients at the start of each communication round. It collects the locally trained model updates from clients and aggregates them to form a new global model.

- Client Devices: The STM32F722ZE MCUs act as the client devices in our setup. Each client trains the global model locally on its respective soil type-specific dataset for 50 epochs. The model updates, rather than raw data, are sent back to the server for aggregation. Although only 7 clients were used, each corresponds to a distinct soil type in the dataset. Since soil heterogeneity is the key source of non-IID distribution in SA, this setup captures the critical challenge of FL in this domain. The focus of this work is on proving feasibility under realistic constraints, while scalability to larger client populations will be addressed in future deployments.

- Federated Averaging (FedAvg): The model aggregation method used in this framework is FedAvg. In each communication round, after the clients complete their local training, the server aggregates the model updates using FedAvg. The aggregation process computes a weighted average of the local models based on the amount of data processed by each client, resulting in an updated global model that is broadcast to all clients for the next round of training [28].

- Communication Protocol: The communication between the server and clients is handled via the MQTT protocol. MQTT was chosen due to its lightweight, bandwidth-efficient nature, which is ideal for resource-constrained environments, ensuring minimal data transfer and efficient model updates [29].

- Training Procedure: The training process is carried out in synchronous rounds, with each round involving the distribution of the current global model from the server to the clients, followed by local model training on the clients’ respective datasets. The updated models are sent back to the server, where they are aggregated to form the new global model. This process is repeated for 3 communication rounds, ensuring iterative improvements to the global model.

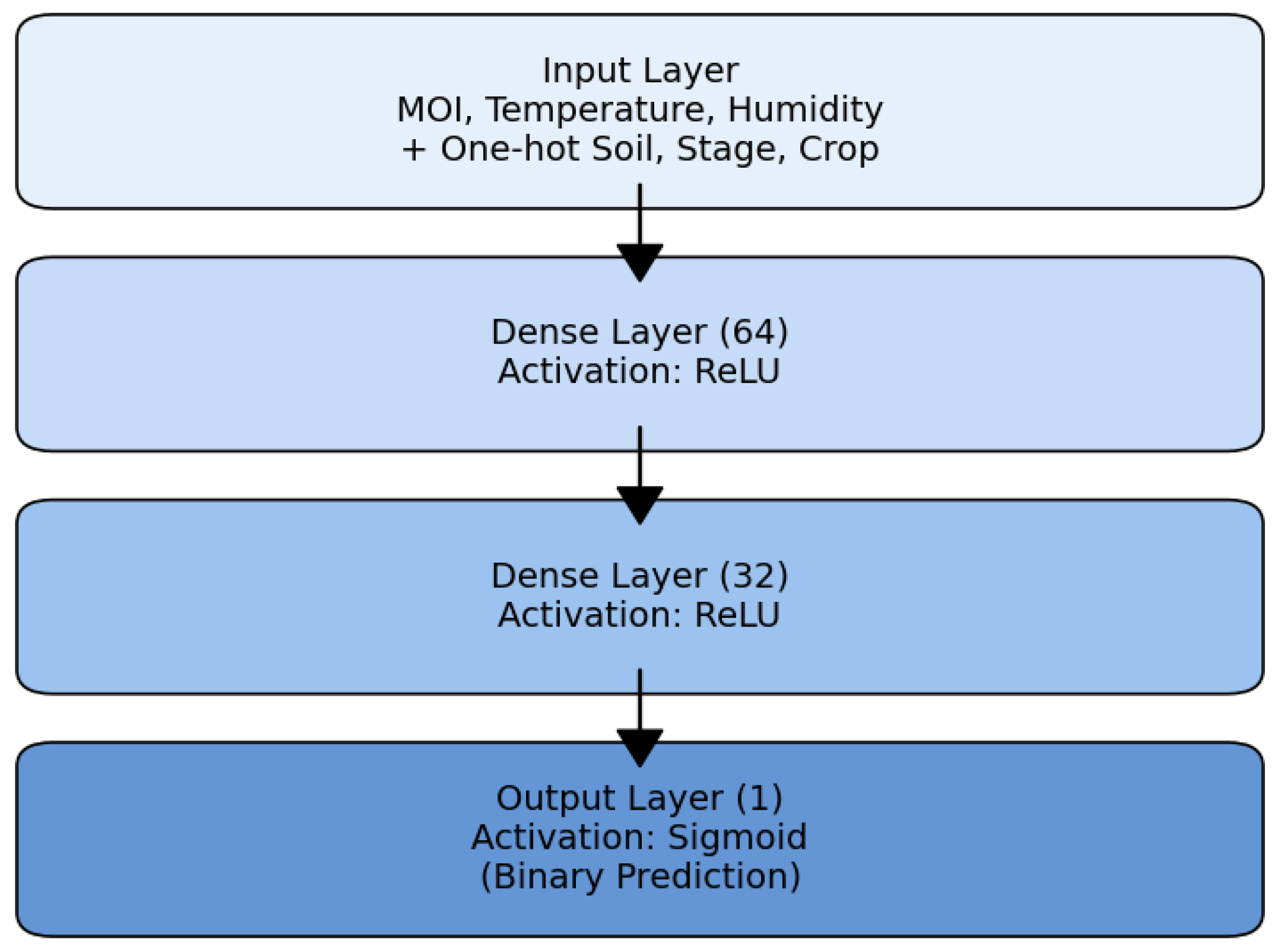

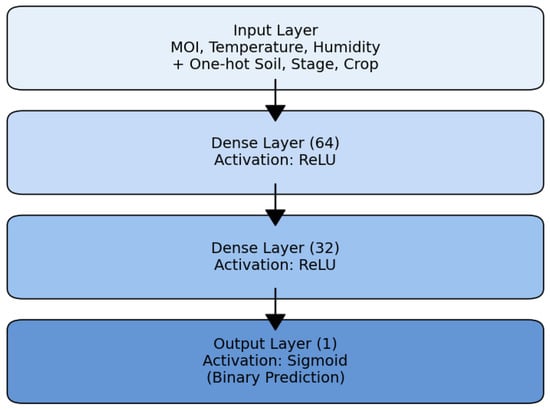

The FL framework was optimized to suit the limited computational and memory capabilities of the STM32F722ZE MCUs. The architecture of the model and training configurations Figure 1 were carefully designed to fit within the constraints of the hardware, ensuring efficient performance while enabling meaningful contributions to the global model from each client. This setup simulates a realistic deployment in practical environments, where constraints such as data privacy, communication efficiency, and device heterogeneity are crucial. It demonstrates that FL can be successfully deployed on low-resource devices like the STM32F722ZE, enabling collaborative learning in real-world IoT applications without compromising model accuracy or data privacy.

Figure 1.

MCU-compatible MLP architecture for smart irrigation: The network consists of two hidden layers (64 and 32 units, ReLU) followed by a sigmoid output layer for binary irrigation prediction.

3.2. Model Architecture and Training Configuration

To enable federated training directly on STM32F722ZE microcontrollers, a lightweight multilayer perceptron (MLP) was designed to balance classification accuracy with strict memory and energy constraints. The model processes both continuous and categorical features derived from the SA dataset.

- Feature set: each client receives input vectors consisting of 3 normalized continuous features (moisture index (MOI), temperature, and humidity) together with categorical variables (soil type, seedling stage, crop type) represented using one-hot encoding. If the number of soil types is denoted as S, seedling stages as G, and crop types as C, the total input dimensionality is defined as:where the term 3 corresponds to the continuous features (MOI, temperature, humidity).

- Network architecture: the MLP structure used in the experiments is as follows:

- –

- Input:

- –

- Dense (64 units, ReLU)

- –

- Dense (32 units, ReLU)

- –

- Output (1 unit, Sigmoid; binary classification: irrigation required/not required)

The total number of parameters can be expressed as:For a typical case with soil types, the model requires approximately 3.6 k parameters, corresponding to ≈14.6 KB in FP32 precision. Peak SRAM usage during training (weights, activations, gradients, and batch buffers) remains below 50 KB, ensuring feasibility on the STM32F722ZE, which provides 256 KB SRAM. - Training configuration: each client trains locally for 50 epochs per round using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with momentum 0.9, a learning rate of 0.01 (step decay after epoch 35), binary cross-entropy loss, and a batch size of 32 (fallback to 16 if memory-constrained). Dropout with rate 0.1 is applied in both hidden layers during training. Gradient clipping is applied with a maximum norm of 1.0 to improve stability under constrained precision.

- Federated setup: the FL experiment involves 7 clients (soil types) participating in 3 synchronous rounds. Updates are aggregated on the server using the FedAvg algorithm, weighted by the number of samples per client. Model updates consist of ∼14–16 KB of weights per client per round, transmitted via MQTT.

- Embedded considerations: the model was compiled using GCC with -O3 and -ffast-math, and optimized using CMSIS-DSP for efficient FP32 operations. Activations are implemented with branchless functions (ReLU clamp, fast sigmoid approximation). Training buffers are stored in SRAM, while model weights are placed in Flash. GPIO toggling was used to measure inference latency with an oscilloscope.Figure 1 illustrates the proposed MLP model architecture, highlighting the flow from input features through hidden layers to the binary irrigation decision.

3.3. Hardware

To implement and evaluate the FL process in a resource-constrained environment, the STM32F722ZE MCU was selected as the client device. This MCU, part of the STM32F7 series by STMicroelectronics, features an ARM Cortex-M7 core and provides a balanced trade-off between performance and energy efficiency, making it a suitable choice for edge computing in IoT applications. The key specifications of the STM32F722ZE are summarized in Table 2. It operates at a frequency of up to 216 MHz and includes 512 KB of flash memory and 256 KB of SRAM, allowing for moderate model deployment and training capabilities. A single-precision Floating Point Unit (FPU) is integrated to accelerate mathematical operations required during model training and inference. The MCU supports various communication interfaces, including SPI, UART, I2C, and USB OTG. For the purposes of this study, the MQTT protocol was employed over UART to ensure lightweight, efficient communication between clients and the server. The device operates at a supply voltage between 1.7 V and 3.6 V and consumes approximately 90 mA in RUN mode at 3.3 V, which was used as a baseline to calculate power and energy consumption during inference. This configuration demonstrated that even low-power, memory-limited embedded systems like the STM32F722ZE are capable of participating in rounds, thus enabling privacy-preserving, distributed intelligence at the edge.

Table 2.

Key Specifications of the STM32F722ZE MCU.

This hardware setup presents a realistic example of the limitations encountered in edge environments, such as restricted memory, limited processing capability, and power constraints. To enable on-device training, neural network architectures were carefully optimized to fit within the memory limits of the device. Furthermore, the device’s GPIO pins were leveraged to precisely measure inference time using external tools such as oscilloscopes. Despite these constraints, the STM32F722ZE MCU successfully participated in all FL communication rounds, locally trained the model on soil-specific datasets, and sent model updates to the server via MQTT. This highlights its potential as an energy-efficient and reliable client for FL-based collaborative learning systems, particularly in SA and, more broadly, in IoT-enabled domains such as smart cities and industrial monitoring.

3.4. Dataset Overview and Preprocessing

The SA dataset [30], used in this study, contains 16,411 crop-related records that capture both crop-specific and environmental attributes influencing crop growth and irrigation requirements. It was selected for two reasons: (i) it provides soil- and crop-related attributes directly relevant to irrigation decisions, and (ii) it ensures reproducibility of our results by the community. Each record provides variables such as crop ID, crop type, soil type, seedling stage, soil moisture index (MOI), temperature, and humidity, along with a target label indicating irrigation status. While the original dataset defines 3 classes ( no irrigation, irrigation required, excess water condition), in this work we focused on a binary classification problem by considering only classes 0 and 1. The excess water condition (class 2) was excluded because it was under-represented in the dataset, and including it would bias the model training and lead to misleading conclusions. Restricting the task to the two well-represented classes allowed us to obtain robust results while concentrating on the primary objective of this work, namely, demonstrating the feasibility of FL on resource-constrained MCUs.

The dataset includes the following main attributes:

- crop ID: Unique identifier for each crop (categorical).

- crop type: Category of the crop (e.g., Rice, Maize, Wheat).

- soil type: Type of soil (e.g., Black Soil, Red Soil).

- seedling stage: Growth phase of the crop (e.g., Germination).

- MOI (Moisture Index): Soil moisture level (integer).

- temp (Temperature): Ambient temperature in °C (integer).

- humidity: Relative humidity percentage (float).

- result: Target variable for irrigation need (binary in our study: 0 = no irrigation, 1 = irrigation required).

To prepare the data for training, the following preprocessing steps were applied:

- normalization: Continuous features (temperature, humidity, and MOI) were normalized to ensure uniform scale and enhance model performance.

- one-hot Encoding: Categorical variables (soil type and seedling stage) were transformed using one-hot encoding to make them suitable for training.

After preprocessing, the data was stratified by soil type (e.g., Black Soil, Red Soil). Each subset was then divided into 3 non-overlapping folds, corresponding to the number of FL rounds. In each round, every STM32F722ZE MCU client received one fold from its assigned soil type, ensuring that:

- Data remained non-overlapping across rounds,

- Each client trained on soil- and crop-specific local data, and

- The global FL model integrated knowledge from diverse and heterogeneous conditions.

This design preserved data decentralization, captured the context of soil and crop variations, and strengthened the generalization ability of the federated model.

3.5. Networking and Communication Setup

The networking architecture relied on the STM32F722ZE board working in tandem with an ESP8266 Wi-Fi module to enable lightweight communication in the FL setup. The ESP8266 provided wireless connectivity and the necessary TCP/IP stack, while MQTT was selected as the application-layer protocol for exchanging model updates. The main elements are summarized as follows:

- Connectivity: each STM32F722ZE board was connected via UART to an ESP8266 Wi-Fi module.

- TCP/IP stack: the ESP8266 handled the full TCP/IP stack and Wi-Fi communication, while the STM32 exchanged data with it using AT commands.

- MQTT protocol: communication was established using the MQTT protocol over TCP/IP.

- Broker: a public MQTT broker (broker.hivemq.com, accessed on 18 March 2025, port 1883) was used for message exchange.

- Security: the chosen setup relied on an unencrypted and unauthenticated channel, meaning confidentiality and integrity of model updates were not ensured.

- Energy accounting: communication energy consumption was not included in the reported measurements.

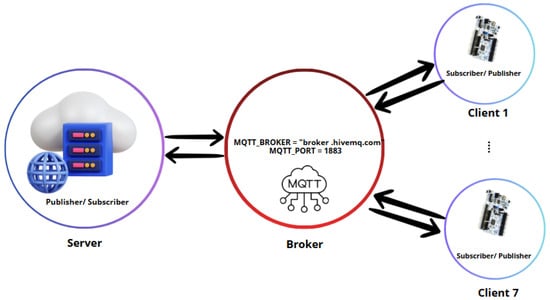

3.6. MQTT Communication Setup

For the FL framework, MQTT was used to facilitate communication between the central server and the STM32F722ZE MCUs (clients). MQTT’s lightweight protocol and low bandwidth requirements make it ideal for IoT environments, especially for resource-constrained devices like the STM32F722ZE [31].

3.6.1. MQTT Configuration

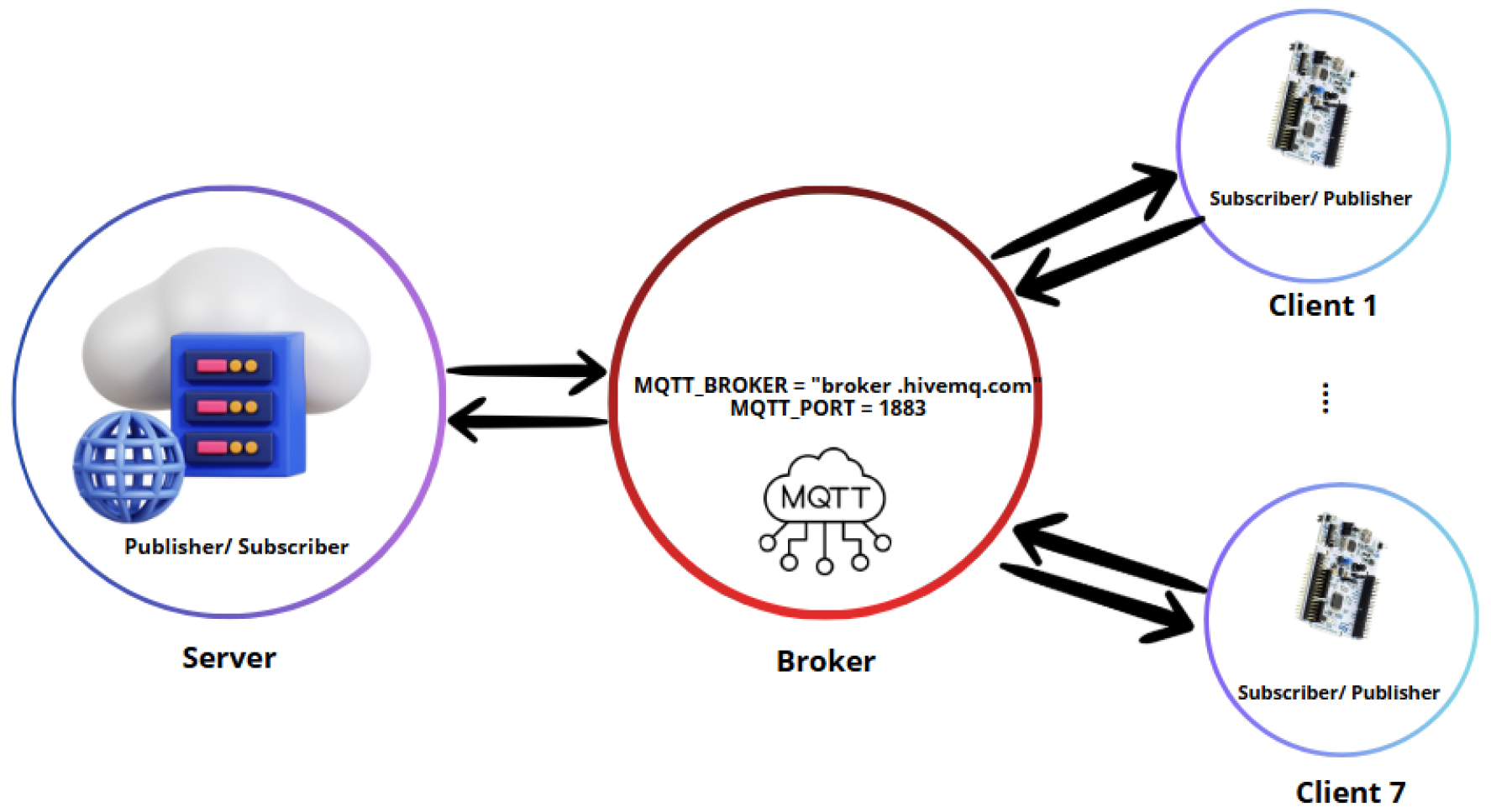

The MQTT configuration, as illustrated in Figure 2, was used to establish communication between the FL server and the clients:

Figure 2.

MQTT communication setup for the FL framework.

- Broker: the MQTT broker chosen for this setup is broker.hivemq.com, a public MQTT broker that supports lightweight, scalable communication. It was used to enable message exchange between the server and clients.MQTT_BROKER = ‘‘broker.hivemq.com’’

- Port: the default MQTT port 1883 was used for unencrypted communication.MQTT_PORT = 1883

- Topics: MQTT topics were used to organize the messages exchanged between the server and clients:

- –

- fl/clients: a topic where the clients publish model updates to be collected by the server.

- –

- fl/server: a topic used by the server to broadcast the global model to all clients for local training.

MQTT_TOPIC_CLIENTS = ‘‘fl/clients’’MQTT_TOPIC_SERVER = ‘‘fl/server’’

3.6.2. Client-Server Communication Flow

- Global Model Distribution: the central server publishes the global model to the fl/server topic at the beginning of each round. All STM32F722ZE clients subscribe to this topic to download the updated model for local training.

- Local Model Updates: after completing local training, each client publishes its model update to the fl/clients topic. The server collects these updates from all clients for aggregation.

- Model Aggregation and Next Round: the server aggregates the model updates using the FedAvg algorithm and broadcasts the updated global model back to the clients for the next round of local training.

4. Federated Training Implementation

To evaluate the applicability of FL in resource-constrained and heterogeneous environments, a federated setup was implemented using multiple STM32F722ZE MCUs as client devices. Each MCU was assigned a distinct data domain corresponding to a specific soil type, derived from the SA dataset. The overall system architecture comprised a central server and several distributed client nodes. The number of rounds was deliberately limited to 3 to reflect the energy and memory constraints of STM32 MCUs. The purpose of this study was not to push for maximal accuracy but to validate that constrained devices can sustain participation in FL rounds. The server was responsible for aggregating the locally trained models using the FedAvg algorithm, while each client independently performed training on its local dataset, preserving data privacy by avoiding any transmission of raw data. Training was conducted over synchronous communication rounds. At the beginning of each round, the global model was broadcast by the server to all clients. Each STM32F722ZE client then trained the received model locally for 50 epochs on its soil type-specific dataset. Upon completion of local training, model updates (i.e., parameters) were transmitted back to the server. The server subsequently aggregated these updates using FedAvg to generate a refined global model. In this implementation, the standard FedAvg algorithm was adopted and adapted to function efficiently on MCU-class hardware. The adaptation focuses on optimizing memory allocation, parameter storage, and communication exchange to accommodate the limited RAM and processing power of embedded devices while preserving the original aggregation logic of FedAvg. This practical adaptation demonstrates that collaborative learning can be achieved on highly resource-constrained platforms without altering the core algorithm. This procedure was iterated over a total of 3 communication rounds. The main hyperparameters and communication configurations used in the FL setup are summarized in Table 3. These parameters were carefully selected to maintain convergence stability within the limited memory and processing constraints of the STM32F722ZE microcontrollers, while ensuring reliable MQTT-based communication among clients and the central server.

Table 3.

Implementation and communication parameters used in the FL framework.

To accommodate the limited memory and computational capabilities of the STM32F722ZE MCUs, the neural network architecture and training configurations were optimized accordingly. The effectiveness of irrigation was evaluated through environmental parameters that characterize soil and climatic conditions relevant to water management. The analysis relied on features such as soil moisture, temperature, and humidity, which are recognized as primary indicators of irrigation adequacy and water balance within the soil. These variables provide a quantitative basis for assessing how effectively the learning framework can capture and model irrigation dynamics across heterogeneous conditions. This approach ensures that irrigation performance is represented in terms of measurable environmental factors directly linked to irrigation control, without the need for direct observation of plant growth. Communication between the server and clients was facilitated using the MQTT protocol, which is lightweight and well-suited for bandwidth-constrained IoT environments. While MQTT’s lightweight nature enables efficient message exchange, its standard configuration offers limited protection against unauthorized access or data tampering. To address this, broker-side authentication and TLS-based encryption were integrated into the communication layer to ensure confidentiality and message integrity during federated model aggregation. These measures provide sufficient protection without imposing significant computational or bandwidth overhead, maintaining MQTT as a secure and practical solution for constrained embedded deployments. Wi-Fi was selected as the communication medium to ensure reliable and low-latency data exchange between the server and client devices during FL rounds. This choice was guided by the need to support frequent bidirectional transfers of model parameters during synchronous aggregation. While low-power alternatives such as LoRaWAN and Zigbee are suitable for periodic sensor data collection, their limited bandwidth and higher latency make them unsuitable for iterative FL, which requires multiple, time-sensitive communications between nodes. Wi-Fi provides the throughput and stability necessary to maintain synchronization among clients and minimize communication delays, thereby ensuring accurate and consistent model aggregation under realistic operating conditions.

To ensure continuous operation under variable weather and seasonal conditions, the client nodes adopt a dual power strategy. When grid power (or a stable DC line) is available, the node operates from a regulated DC supply that matches the electrical profile of a battery system. For standalone deployments, the node operates from a solar subsystem comprising a photovoltaic panel, an MPPT charge controller, and a LiFePO4 battery pack sized for 2–3 days of autonomy. The power manager selects the source based on state of charge (SoC) and input availability: (i) if SoC ≥ 30% and solar input is present, the node runs on solar/battery; (ii) if SoC < 30% or prolonged low-irradiance is detected (e.g., rainy days or winter), the node automatically falls back to the regulated DC line when present, or enters an energy-conserving mode that reduces FL frequency (e.g., fewer local epochs) and increases MCU sleep duty cycles while preserving sensing and safety. Hardware protections include brownout detection, reverse-polarity protection, and over/under-voltage safeguards on the battery path. Environmental robustness is addressed via an IP65 enclosure with conformal-coated PCBs, hydrophobic vents to mitigate condensation, and temperature-aware charging (LiFePO4 charge inhibited below 0 °C) to ensure reliable operation across humidity and day/night temperature swings. This arrangement provides a practical power architecture for both mains-assisted installations and fully off-grid agricultural deployments, including rainy seasons and winter periods. This implementation thus closely simulates a realistic deployment scenario where privacy preservation, communication efficiency, and device heterogeneity are crucial for the success of collaborative learning.

As summarized in Algorithm 1, the training process follows the standard FL workflow, with each STM32F722ZE client performing local training on its private dataset and the server aggregating updates via FedAvg. Despite the constrained resources of the STM32 platform, the system maintained stable convergence across 3 rounds, thereby validating the feasibility of deploying FL on embedded IoT devices while preserving data privacy.

| Algorithm 1 FL Process on STM32F722ZE MCUs |

|

5. Evaluation Methodology

To evaluate the practical feasibility of deploying FL on resource-constrained embedded devices, both inference time and energy consumption during on-device prediction were assessed using the STM32F722ZE MCU. The inference time was determined by programming the MCU to toggle a GPIO pin immediately before and after the inference operation. The time difference between the rising and falling edges of the GPIO signal, acquired with an oscilloscope, accurately represents the total duration of the inference process, including any internal computations and post-processing tasks. For energy-consumption estimation, the MCU was configured to operate in RUN mode at its nominal supply voltage of

According to the STM32F722ZE datasheet, the typical RUN-mode current of the microcontroller alone increases almost linearly with the CPU clock frequency approximately 11 mA at 25 MHz, 23 mA at 60 MHz, 51 mA at 144 MHz, 74 mA at 180 MHz, and about 90 mA at 216 MHz when all peripherals are disabled. In our setup, the MCU operated at 216 MHz, corresponding to an expected current of about

which served as a theoretical reference for validation. The actual current drawn by the MCU was experimentally measured by connecting a digital multimeter to the IDD pin of the NUCLEO-F722ZE board. This configuration isolates the MCU’s core supply rail from the auxiliary circuitry of the development board including the on-board debugger, power-regulation stage, and interface logic ensuring that only the current consumed by the MCU core and its internal peripherals was captured. The measured current profile closely followed the datasheet trend versus frequency, confirming the validity of the reference values under the specific operating conditions.

Power consumption was computed as:

Once the inference time () and power (P) were obtained, the per-inference energy was derived as:

where is the measured MCU current, the operating voltage, and the inference time recorded via the oscilloscope. This measurement-based and frequency-aware approach provides a hardware-referenced estimation of energy consumption, enabling realistic evaluation of on-device learning performance in constrained embedded platforms. This methodology allows a precise evaluation of both temporal and energy efficiency, helping to determine whether FL-based models can be realistically supported by resource-limited MCUs in real-world IoT deployments. To ensure a fair and leakage-free evaluation, the data used for performance assessment were kept strictly separate from those used during all FL rounds. For each soil type, the available samples were initially divided into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Both subsets were then further partitioned across the three federated rounds so that each round utilized distinct portions of the data for training and corresponding disjoint portions for testing. This approach guarantees that no data samples were reused between rounds and that the evaluation process remained independent at every stage of aggregation. After each global aggregation round, model accuracy was computed as the average of all client test performances. This protocol ensures a fully disjoint and leakage-free evaluation setup, accurately reflecting the generalization capability of the federated models under heterogeneous and dynamic conditions.

Energy Latency Accuracy Index (ELAI)

To compare heterogeneous devices on a common scale, we define a composite performance metric, the ELAI. This index integrates model accuracy (A), energy per inference (E), and inference latency (L) into a single normalized score. Each component is first min–max normalized across all experiments:

where , , and lie in the range , with accuracy treated as a benefit (higher is better) and energy/latency as costs (lower is better). Normalization is applied across all devices (MCU and PC) and across all rounds, ensuring that the resulting values are directly comparable on a common scale. To prevent numerical instability, we clip and to a minimum value before use, and clip all normalized values to the range .

- Functional form: We model efficiency as (benefit per unit cost) by placing accuracy in the numerator and a weighted sum of normalized energy and latency in the denominator:This ratio has a direct interpretation: ELAI increases when accuracy rises or when costs fall, and the relative influence of energy versus latency is controlled by the weights and . For robustness, we also verified that the device ranking remains qualitatively the same when using alternative formulations such as a weighted geometric index or a weighted additive score.

- Weighting and sensitivity: In energy-limited deployments such as battery-powered or energy-harvesting smart irrigation systems, we assign higher importance to energy () than to latency (). We additionally varied within and jointly scaled to test sensitivity. In all tested cases, the MCU consistently achieved higher efficiency than the PC, showing that the relative advantage is robust to weight selection.

By condensing accuracy, energy, and latency into a single efficiency indicator, ELAI offers an integrated perspective on performance that is not apparent when considering accuracy, energy, or latency in isolation.

6. Experimental Results and Discussion

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the proposed on-device FL framework for smart irrigation. The experiments were conducted using both STM32F722ZE MCU clients and standard PC clients for comparison. Results are reported at both client and server levels, covering test accuracy, inference latency, and energy consumption. Alongside these measurements, the ELAI is used as a composite metric to evaluate the overall efficiency trade-off across heterogeneous devices. Figures and tables are provided to illustrate each aspect, supported by commentary.

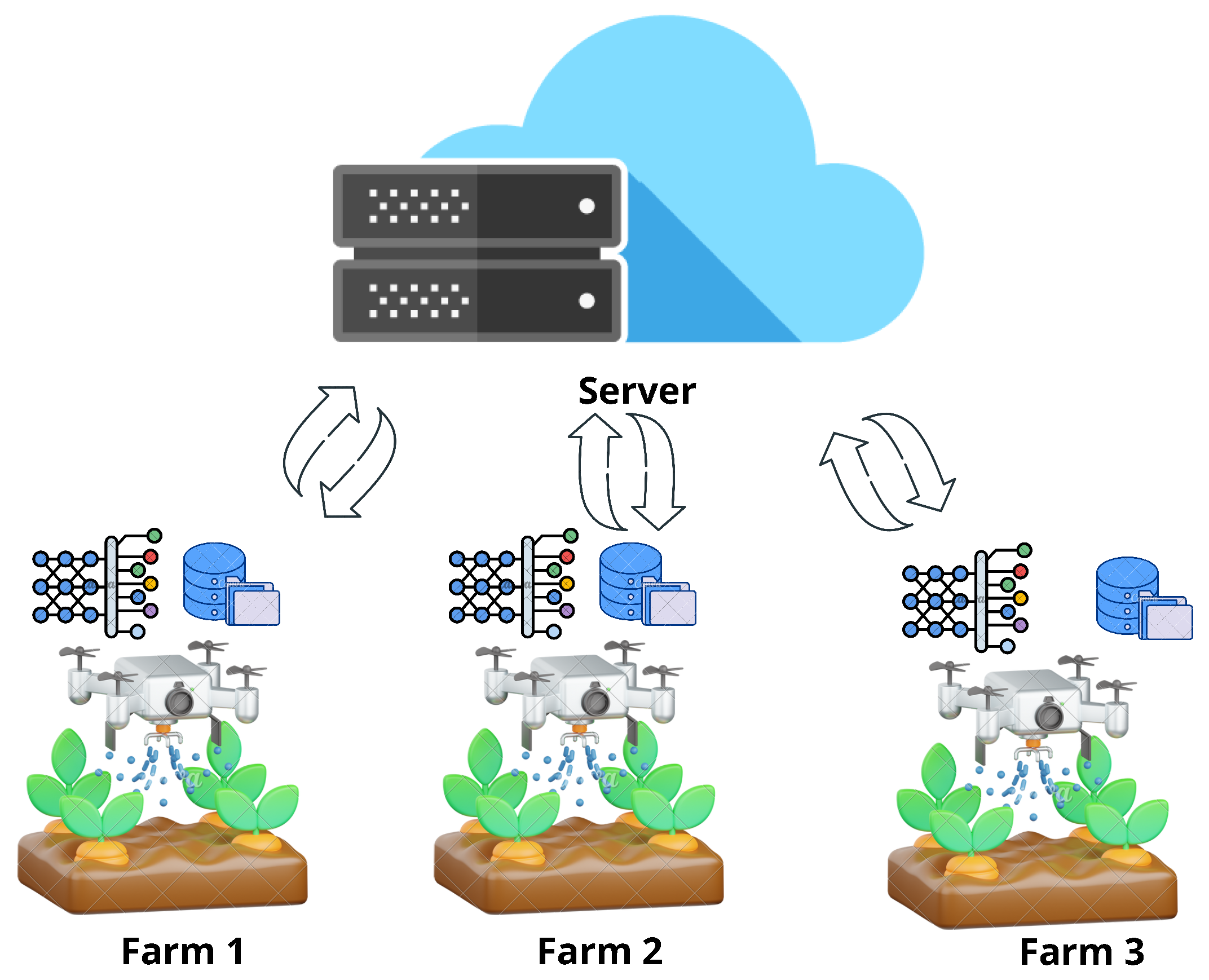

6.1. FL in Smart Irrigation

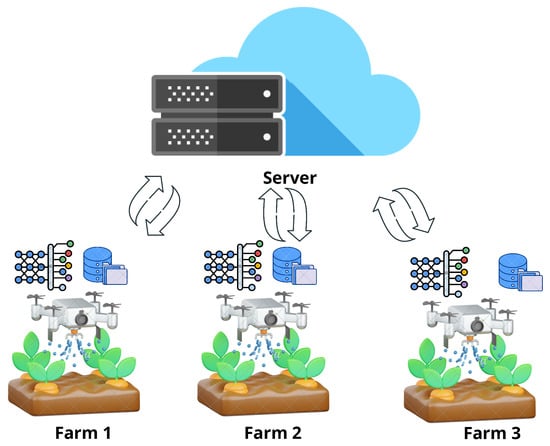

The proposed FL framework was applied to a smart irrigation use case involving distributed data collection and local model training across farms. IoT devices deployed on each farm (client) gathered environmental data, including soil moisture, temperature, and humidity. Each client trained its model locally, and updates were sent to a central server for aggregation using FedAvg. The server then returned the updated global model for the next round of training, ensuring decentralized learning while preserving privacy.

As shown in Figure 3, the dataset was partitioned by soil type, with each client corresponding to one soil category. 3 training rounds were conducted, each aggregating locally trained models into the global model. This iterative procedure supports efficient irrigation decisions while keeping raw data local to each farm.

Figure 3.

FL in Smart Irrigation: IoT devices collect farm data, train local models, and send updates to a central server, which aggregates updates and returns an optimized global model.

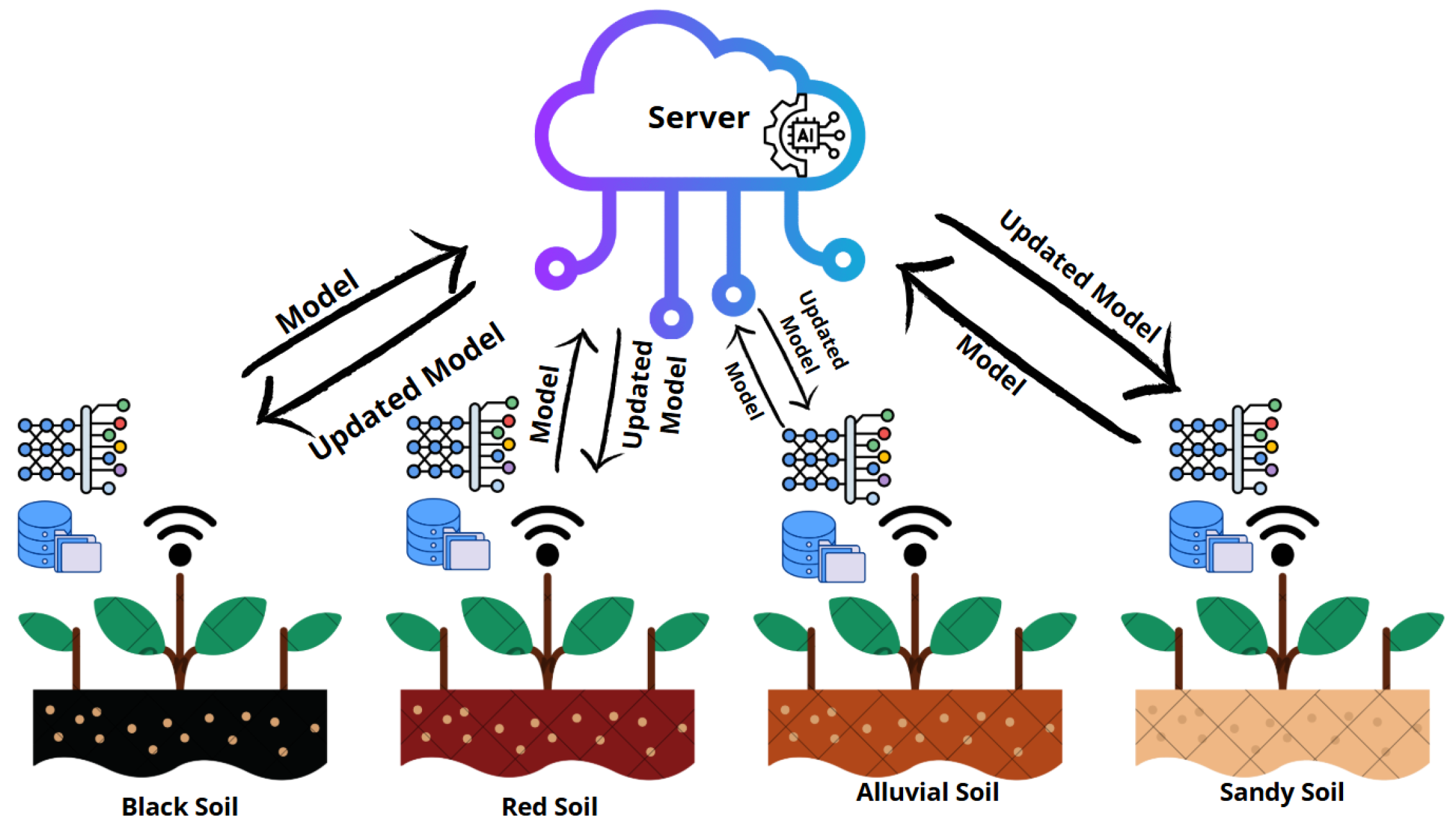

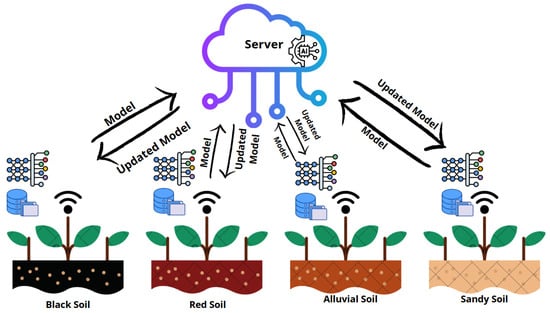

6.2. Evaluation Across Heterogeneous Soil Types

7 distinct soil types were used to represent the FL clients, ensuring data heterogeneity. This non-IID distribution challenges the global model to generalize across different soil environments. Figure 4 illustrates the soil-based FL setup.

Figure 4.

SA powered by FL in heterogeneous soil types: IoT sensors deployed across soil categories collect localized data. These sensors collaboratively train a global model while preserving data privacy.

The diversity of soil-specific data contributes to model robustness but also results in varying client performance. Table 4 reports the test accuracy for each client (soil type) on both PC and MCU platforms.

Table 4.

FL Client Performance on SA Dataset.

As shown in Table 4, PC clients consistently achieve accuracies between 80–85%, while MCU clients achieve slightly lower but competitive values between 70–82%.

6.3. Server-Level Performance

The aggregated global accuracy on the FL server improved steadily across rounds, as shown in Table 5. Despite the constrained hardware of MCU clients, FedAvg aggregation led to convergence comparable to the PC-based setup.

Table 5.

Test Accuracy on Server Across FL Rounds (SA).

The results confirm that federated aggregation maintains global accuracy under non-IID conditions, with both MCU and PC setups achieving over 90% by the third round.

6.4. Inference Latency

Inference latency was measured by toggling a GPIO pin around the forward-pass code and capturing execution time with an oscilloscope, ensuring hardware-level timing precision. The STM32F722ZE clients consistently demonstrated inference times of approximately 3.2 ms per sample, compared to sub-millisecond execution on PCs. While MCU latency is an order of magnitude higher, this difference remains negligible in the context of irrigation control, where actuation typically occurs on timescales of seconds to minutes. These results confirm that MCU-based clients can provide timely responses in practical deployments without compromising energy efficiency.

6.5. Inference and Training Energy

Energy consumption was derived from the measured latency and device current, using at a 3.3 V supply. Inference energy was measured directly, while training energy was extrapolated from repeated forward and backward passes. Across all clients, STM32F722ZE MCUs required only about 0.95 mJ per inference, compared to 60–70 mJ for PC clients. This corresponds to an energy saving of roughly 300×, underscoring the extreme efficiency of MCU devices. For training, MCUs consumed approximately 70 mJ per epoch, while PCs required nearly 20 J. These findings demonstrate that, even with modestly longer inference times, MCU-based federated training achieves orders-of-magnitude energy reductions, making it particularly attractive for energy-constrained IoT deployments such as smart irrigation.

6.6. ELAI Analysis

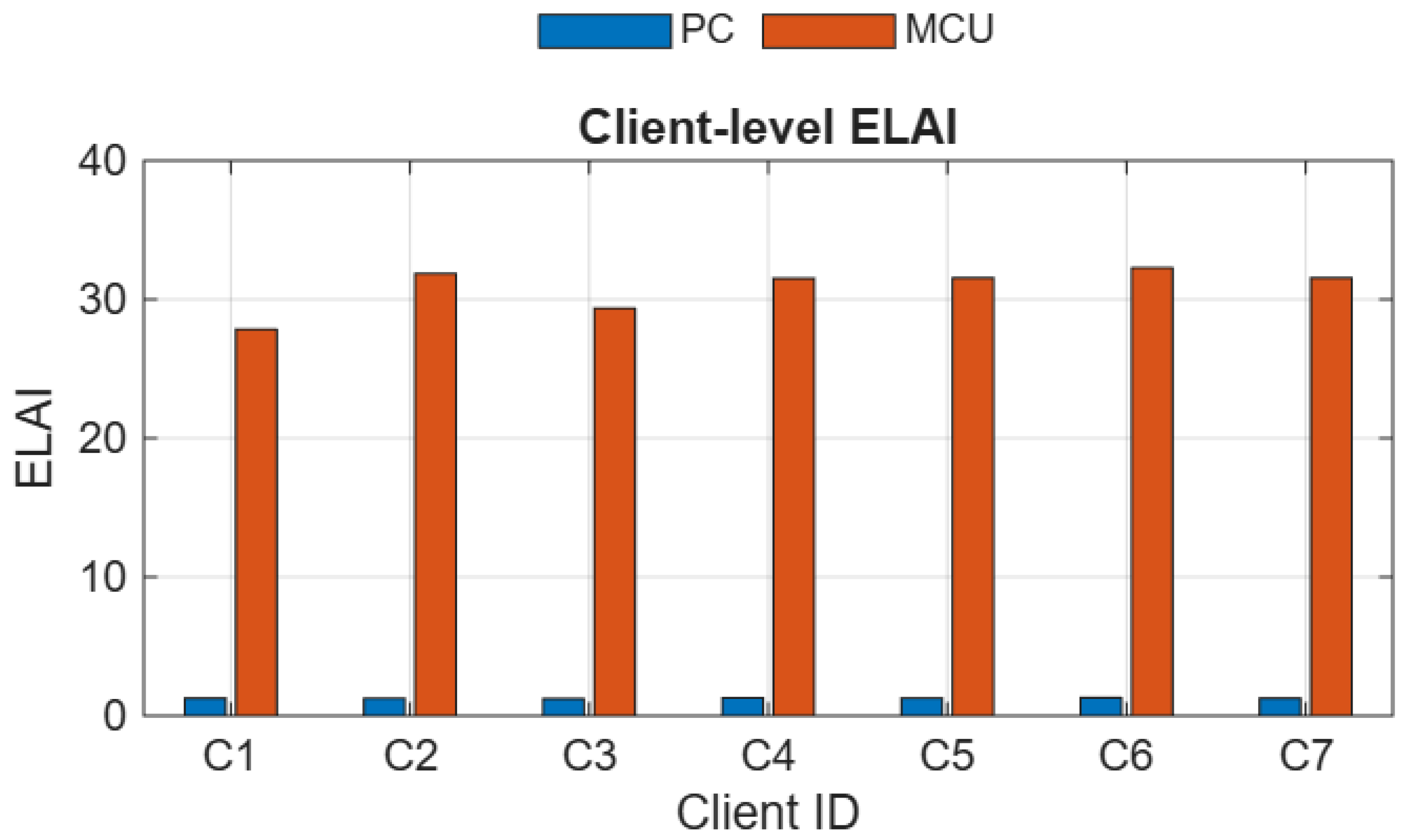

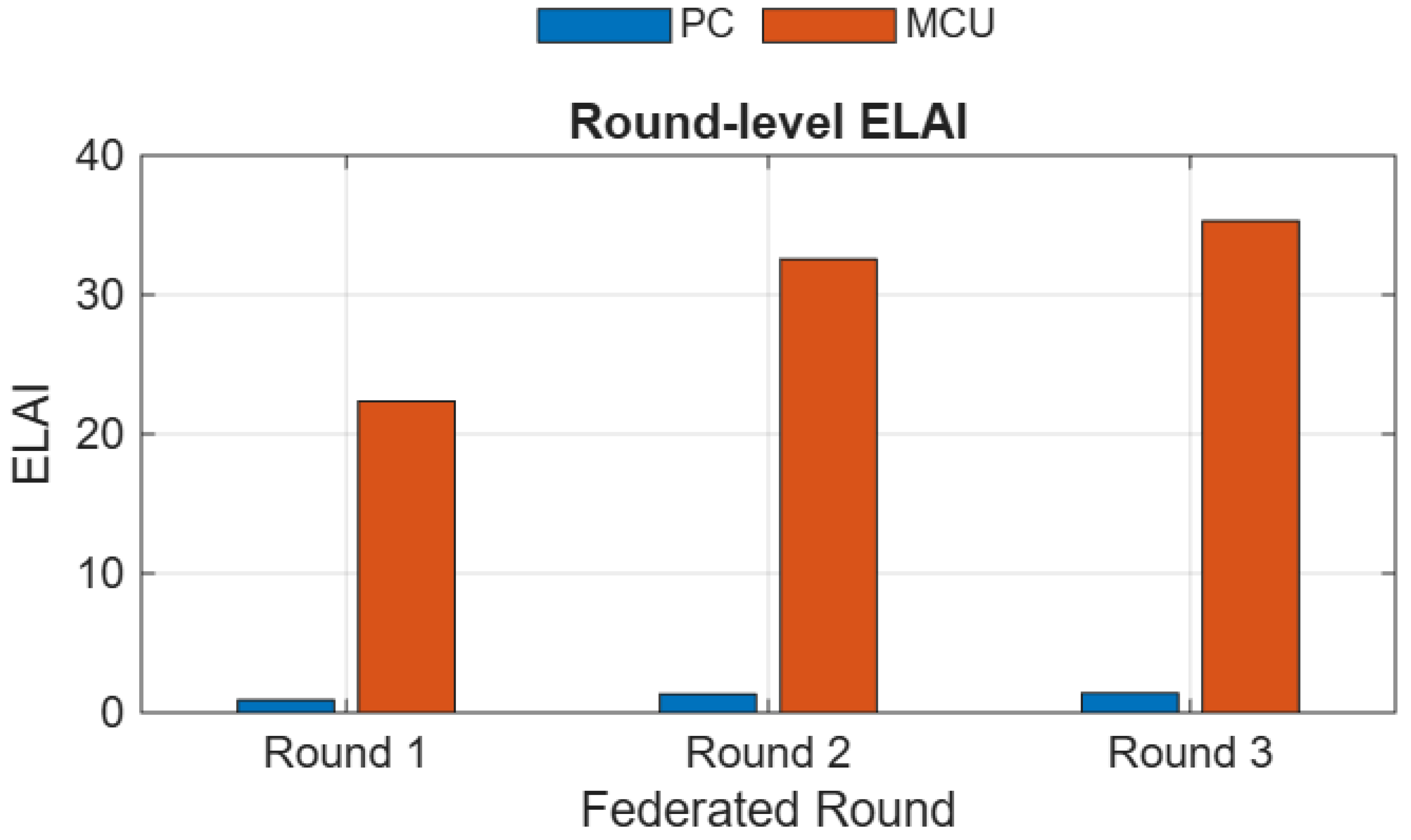

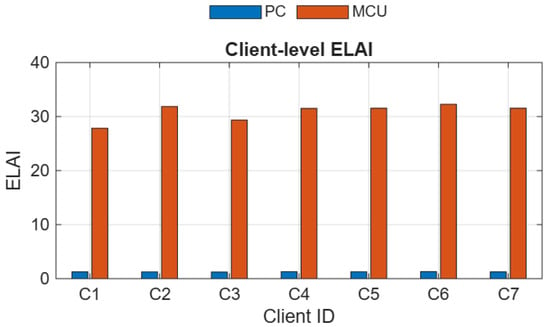

To better highlight the trade-off between accuracy, energy, and latency, we report the ELAI for both client-level and round-level evaluations. This composite metric provides a more complete picture of efficiency compared to accuracy alone.

Figure 5 shows the client-level ELAI across all 7 clients. Although PC-based training achieves slightly higher accuracy in some cases, the much higher energy consumption (∼65 mJ per inference) results in consistently lower ELAI values compared to MCU devices (∼0.95 mJ per inference). This indicates that MCU devices provide substantially better efficiency across all clients, despite modest accuracy differences.

Figure 5.

Client-level ELAI shows that MCUs consistently outperform PCs, confirming their efficiency advantage across all soil types.

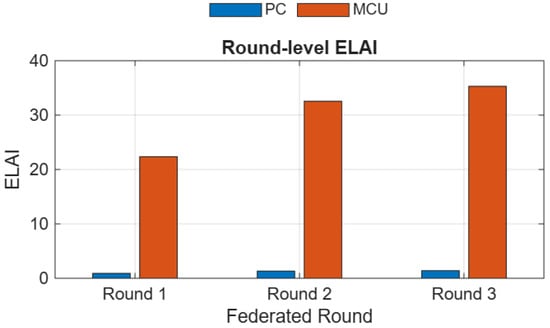

Figure 6 presents the round-level server ELAI over 3 communication rounds. Both MCU and PC accuracies improve as training progresses, but MCU maintains a clear advantage in ELAI throughout all rounds. This shows that MCU devices remain preferable when efficiency is considered a primary deployment constraint in IoT scenarios such as smart irrigation.

Figure 6.

Round-level ELAI highlights that MCU superiority persists throughout training, demonstrating scalability under efficiency constraints.

6.7. Discussion

The experimental evaluation highlights clear trade-offs between MCU-based clients and standard PC clients in the FL framework. In terms of accuracy, STM32F722ZE clients achieved test accuracies in the 70–82% range, only 2–4 percentage points lower than PCs, which consistently reached 80–85%. This relatively small reduction demonstrates that resource-constrained devices can still provide competitive model quality under non-IID conditions. Latency results further confirm MCU feasibility. While MCU inference required on average ∼3.2 ms compared to sub-millisecond latency on PCs, this delay remains negligible for agricultural irrigation tasks, where control decisions operate on timescales of seconds to minutes. Thus, the modest increase in latency does not affect the practical utility of MCU-based deployment. The most significant benefit of MCU deployment lies in energy efficiency. MCU inference consumed only 0.95 mJ per sample, representing a ∼300× reduction compared to PC inference (60–70 mJ). For training, the contrast was even greater: ∼70 mJ per epoch on the MCU versus ∼20 J on the PC. This drastic energy saving makes MCUs ideal for edge-based SA, where devices must operate continuously on limited power budgets such as batteries or energy-harvesting modules. Beyond reporting accuracy, energy, and latency separately, we examined their combined payoff by means of a composite index. This analysis shows that, while PCs achieve marginally higher accuracy in some cases, MCUs benefit from substantially lower energy demand and acceptable latency. The resulting balance makes MCU-based training more favorable in scenarios where efficiency and sustainability are critical, such as precision agriculture and IoT-enabled resource management. Overall, these results confirm that MCU clients can provide near-PC accuracy with acceptable latency while achieving orders-of-magnitude energy savings, positioning them as the preferred choice for scalable, sustainable, and privacy-preserving FL in smart irrigation.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we applied FL to a soil-aware irrigation use case in which data was distributed according to soil type, allowing each farm (client) to train locally while preserving privacy. The experimental results demonstrated that STM32-based MCU clients, despite their limited resources, achieved accuracy comparable to PC clients (70–82% vs. 80–85%) while consuming drastically less energy. Specifically, MCU clients required only 0.95 mJ per inference compared to 60–70 mJ on PCs, representing an energy reduction of nearly 300×. During training, MCUs also consumed around 70 mJ per epoch compared to nearly 20 J on PCs, while maintaining competitive convergence. Inference latency on MCUs was measured at ∼3.2 ms, which is acceptable for near real-time irrigation decisions. These results confirm that MCU devices provide a strong efficiency advantage for edge-based smart irrigation, where minimizing power usage and ensuring timely responses are critical. To capture the joint trade-off among accuracy, latency, and energy, we employed the ELAI. This composite metric offered the clearest evidence of MCU superiority, confirming that MCUs achieve a more advantageous efficiency balance compared to PCs. Among all reported metrics, ELAI provides the most holistic view of device performance in energy-constrained IoT deployments. It should be emphasized that this study represents a controlled feasibility evaluation rather than a full-scale deployment. The setup with 7 clients and 3 communication rounds was deliberately chosen to validate the feasibility of executing FL directly on resource-constrained MCUs under realistic memory and power constraints. While this configuration is sufficient to demonstrate viability, larger-scale studies with more clients, additional communication rounds, and heterogeneous network conditions remain important directions for future work. Future work will also extend the approach to real-time sensor measurements and explicitly incorporate communication energy costs, which were not included in this evaluation. Low-power communication protocols such as LoRaWAN, along with techniques such as quantization, client drop-out handling, and longer training horizons, will be investigated to further enhance efficiency, robustness, and scalability. Overall, these findings indicate that energy-efficient FL on MCUs can provide near powerful device accuracy, acceptable latency, and orders-of-magnitude energy savings. By showing that FL can run directly on ultra-low-power hardware, this work contributes to the broader vision of sustainable digital agriculture, paving the way for scalable, privacy-preserving, and energy-conscious smart farming solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.D. and M.M.; methodology, M.M.; software, Z.D. and A.L.; validation, Z.D., A.L. and M.M.; formal analysis, Z.D.; investigation, Z.D.; resources, M.M.; data curation, Z.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.D.; writing—review and editing, Z.D., A.L., M.R.S., M.R. and M.M.; visualization, Z.D.; supervision, M.R. and M.M.; project administration, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the project “Ecosistema TECH4YOU—Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement” and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)—M4C2—Investment 1.5—”Innovation Ecosystems”—D.D. 3277 of 30 December 2021). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available from the Smart Agriculture Dataset on Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chaitanyagopidesi/smart-agriculture-dataset, accessed on 28 September 2025). No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Banbury, C.R.; Reddi, V.J.; Lam, M.; Fu, W.; Fazel, A.; Holleman, J.; Huang, X.; Hurtado, R.; Kanter, D.; Lokhmotov, A.; et al. Benchmarking TinyML Systems: Challenges and Direction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2003.04821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhia, Z.; Russo, M.; Merenda, M. AI-Enabled IoT for Food Computing: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakr, F.; Bellotti, F.; Berta, R.; De Gloria, A. Machine Learning on Mainstream Microcontrollers. Sensors 2020, 20, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaglia, L.; Rusci, M.; Nadalini, D.; Capotondi, A.; Conti, F.; Benini, L. A TinyML Platform for On-Device Continual Learning with Quantized Latent Replays. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenda, M.; Astrologo, M.; Laurendi, D.; Romeo, V.; Della Corte, F.G. A novel fitness tracker using edge machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 20th Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON), Palermo, Italy, 16–18 June 2020; pp. 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Anicic, D.; Runkler, T. TinyOL: TinyML with Online-Learning on Microcontrollers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.08295. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated Machine Learning: Concept and Applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisimi, T.S.; Chen, R.; Mela, T.; Olshevsky, A.; Paschalidis, I.C.; Shi, W. Federated learning of predictive models from federated electronic health records. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 112, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosika, T.; Shukla, R.M.; Pranggono, B. Transparency and privacy: The role of explainable AI and federated learning in financial fraud detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 64551–64560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hard, A.; Rao, K.; Mathews, R.; Ramaswamy, S.; Beaufays, F.; Augenstein, S.; Eichner, H.; Kiddon, C.; Ramage, D. Federated learning for mobile keyboard prediction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.03604. [Google Scholar]

- Mwawado, R.; Zennaro, M.; Nsenga, J.; Hanyurwimfura, D. Optimizing Soil-Based Crop Recommendations with Federated Learning on Raspberry Pi Edge Computing Nodes. In Proceedings of the 2024 11th International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS), Malmö, Sweden, 2–5 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dakhia, Z.; Merenda, M. Client Selection in Federated Learning on Resource-Constrained Devices: A Game Theory Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenda, M.; Cimino, G.; Carotenuto, R.; Corte, F.G.D.; Iero, D. Edge machine learning techniques applied to RFID for device-free hand gesture recognition. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2022, 6, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.; Romaine, J.B.; Johnson, P.; Cardona, A.; Millan, P. Novel Fusion Technique for High-Performance Automated Crop Edge Detection in Smart Agriculture. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 22429–22445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desikan, J.; Singh, S.K.; Jayanthiladevi, A.; Singh, S.; Yoon, B. Dempster Shafer-Empowered Machine Learning-Based Scheme for Reducing Fire Risks in IoT-Enabled Industrial Environments. IEEE Access 2015, 13, 46546–46567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Federated Learning for IoT: A Survey of Techniques, Challenges, and Applications. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Eichner, H.; Grieskamp, W.; Huba, D.; Ingerman, A.; Ivanov, V.; Kiddon, C.; Konečný, J.; Mazzocchi, S.; McMahan, B.; et al. Towards federated learning at scale: System design. In Proceedings of the 2nd SysML Conference, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2–4 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sikiru, I.A.; Kora, A.D.; Ezin, E.C.; Imoize, A.L.; Li, C.-T. Hybridization of learning techniques and quantum mechanism for IIoT security: Applications, challenges, and prospects. Electronics 2024, 13, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Drew, S.; Zhou, J. FedLE: Federated Learning Client Selection with Lifespan Extension for Edge IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications, Rome, Italy, 28 May–1 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Valente da Silva, R.; López, O.L.A.; Souza, R.D. Federated Learning–Distillation Alternation for Resource-Constrained IoT. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.20456. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, I.; Adams, R.P.; Mattina, M.; Whatmough, P. SpArSe: Sparse Architecture Search for CNNs on Resource-Constrained Microcontrollers. arXiv 2019, 4978–4990. [Google Scholar]

- Disabato, S.; Roveri, M. Incremental On-Device Tiny Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Virtual, 16–19 November 2020; pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kopparapu, K.; Lin, E. TinyFedTL: Federated Transfer Learning on Tiny Devices. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.01107. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, A.; Beutel, D.J.; de Gusmão, P.P.B.; Fernandez-Marques, J.; Topal, T.; Qiu, X.; Parcollet, T.; Gao, Y.; Lane, N.D. On-device Federated Learning with Flower. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.03042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Sun, R.; Xue, M.; Wen, S.; Camtepe, S.; Nepal, S.; Xiang, Y. Leakage-Resilient and Carbon-Neutral Aggregation Featuring the Federated AI-Enabled Critical Infrastructure. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STMicroelectronics, “STM32F722ZE Microcontroller.” [Online]. Available online: https://www.st.com/en/microcontrollers-microprocessors/stm32f722ze.html (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.Y. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the 20thInternational Conference Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H., Jr.; Lin, T.; Hsia, K.-H. Web-based IoT and Robot SCADA using MQTT protocol. J. Robot. Netw. Artif. Life 2022, 9, 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gopidesi, C. Smart Agriculture Dataset, Kaggle, 2021. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chaitanyagopidesi/smart-agriculture-dataset (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Ap, H.; Kulothungan, K. Secure-MQTT: An efficient fuzzy logic-based approach to detect DoS attack in MQTT protocol for Internet of Things. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 90. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).