Abstract

To achieve real-time and accurate pose estimation for weakly textured or occluded targets, this study proposes a feature-enhancement 6D pose estimation method based on DenseFusion. Firstly, in the image feature extraction stage, skip connections and attention modules, which could effectively fuse deep and shallow features, are introduced to enhance the richness and effectiveness of image features. Secondly, in the point cloud feature extraction stage, PointNet is applied to the initial feature extraction of the point cloud. Then, the K-nearest neighbor method and the Pool globalization method are applied to obtain richer point cloud features. Subsequently, in the dense feature fusion stage, an adaptive feature selection module is introduced to further preserve and enhance effective features. Finally, we add a supervision network to the original pose estimation network to enhance the training results. The results of the experiment show that the improved method performs significantly better than classic methods in both the LineMOD dataset and Occlusion LineMOD dataset, and all enhancements improve the real-time performance and accuracy of pose estimation.

1. Introduction

Six-dimensional target pose estimation refers to the prediction of the target’s rotation matrix and translation vector in the camera coordinate system, and it has been extensively applied in many fields, including robotic manipulation, autonomous driving, and augmented reality. These applications encounter significant challenges in achieving accurate and real-time performance, particularly when objects are occluded or weakly textured. Early approaches relied exclusively on RGB images for object pose estimation, which inherently limited their capacity to capture the full three-dimensional structure of objects. RGB images primarily provide appearance information and are highly sensitive to occlusion, lighting variations, and weak texture. Consequently, when objects are partially occluded or lack visual patterns, these methods fail to extract robust spatial features, resulting in significant degradation of pose estimation accuracy.

The development of deep learning has significantly promoted the advancement of computer vision. CNNs excel at spatial feature extraction (e.g., A-YONet [1]), and LSTMs are effective in sequential data, such as treatment prediction [2], medical dialogs [3], financial risk forecasting [4], and ICU outcome prediction [5]. Deep learning supports weak-label training in IoHT scenarios [6], while adversarial models like HAA enhance robustness via graph neural networks [7]. Multimodal fusion methods typically leverage PointNet++ [8] for point cloud feature extraction and segmentation networks such as CRF-enhanced U-Net [9] for RGB image feature learning, thereby integrating heterogeneous data sources. RNNs with attention mechanisms have been proven effective in semantic and quality analysis [10], and IoT-based systems combined with deep learning enhance the accuracy of image detection [11]. In resource-limited environments, DRL-based scheduling [12] and blockchain-enhanced logistics frameworks ensure traceability and efficiency of scheduling and logistics processes [13]. Deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling [14] and adaptive architectures [15] further refine feature discrimination. A neural network, optimized by genetic algorithms, also shows strong performance in financial forecasting [16]. Some researchers combined Bi-GRU with the Mayfly Algorithm (MFA) for supply chain sales forecasting, achieving lower errors than traditional models [17]. This idea is similar to the one outlined in our work, which enhances overall performance by improving core system elements. These deep learning techniques form the foundation of our feature enhancement framework for pose estimation, demonstrating the potential of deep methods in various application domains.

The emergence of RGB-D cameras introduces additional in-depth information, offering new solutions for pose estimation problems. Traditional pose estimation methods for RGB-D images involve manually extracting features from RGB-D images and matching them. They are easily affected by many factors such as target occlusion and light changes, resulting in poor practical application performances. With the widespread use of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), some researchers have applied these networks to solve RGB image pose estimation problems. These methods can be categorized into two types. The first category utilizes CNNs to detect 2D keypoints in RGB images, and then employs the Perspective-n-Point (PnP) algorithm to calculate 6D pose parameters, as seen in PVNet [18] and OSOP [19]. It solves the problem of keypoint detection for textureless objects, which traditional methods cannot achieve. However, in the case of occlusion, the detection method of 2D keypoints cannot accurately estimate the pose of the target. The second category directly uses CNN to obtain the 6D pose of the target. Xiang [20] utilizes the advantages of two data sources in a cascade design to estimate the initial pose from RGB images, but the accuracy of the pose is not sufficient. These methods rely on Iterative Closest Point (ICP) or multi-view hypothesis verification schemes to refine the estimation results, which are very time-consuming.

In response to the shortcomings of the above two types of methods, Charles [21] and Xu [22] utilize a point cloud network and a CNN to extract dense features from cropped RGB images and point clouds. Then, they connect these extracted dense features for pose estimation. DenseFusion [23] employs CNNs to extract color features and PointNet [24] to extract point cloud features, which are subsequently fused at the pixel level to estimate object poses. It achieves higher accuracy in scenarios with occlusion and low illumination. However, it is extremely challenging to estimate the pose of objects with similar appearances or reflective surfaces. Many researchers believe that this is due to the insufficient fusion of the two types of data, and they focus on improving the fusion method for color features and point cloud features. FFB6D proposes a full-stream bidirectional fusion network that performs fusion at each encoding and decoding layer. The appearance information of RGB and the geometric information of point clouds serve as complementary information in the feature extraction process [25]. NF6D proposes a novel network, similar to PointNet++ [8], to process fused features and estimate the pose of an object [26].

To address the limitations of existing fusion-based methods, which often suffer from incomplete feature representation and suboptimal fusion under occlusion or weak texture, we propose a novel 6D target pose estimation framework with feature enhancement. Specifically, we introduce skip connections and attention modules into the image feature extractor to enrich deep semantic information. For point cloud features, we employ an improved PointNet++ to capture both geometric and semantic cues. Furthermore, we design an adaptive feature selection module to optimize the dense fusion of RGB and point cloud features and integrate a supervision network to refine the training process. Together, these innovations enable more robust and accurate 6D pose estimation in challenging scenarios, outperforming previous methods in both occluded and low-texture conditions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Pose Estimation from RGB Images

The RGB-based method utilizes only RGB images to estimate object pose. The classic method typically first finds the keypoints, then matches them to calculate a 6D pose. Recently numerous new methods using neural networks to estimate a 6D pose have been developed, which can be categorized into two types: holistic methods [27,28] and correspondence-based methods [29,30]. The holistic method uses neural networks to directly regress the 6D pose: Hu et al. [31] propose a single-stage 6D pose estimation network, which first establishes the correspondence between 3D object keypoints and 2D image positions, and then directly regresses the 6D pose from the correspondence using a deep architecture. Avery et al. [32] propose a novel recursive network architecture, DeepRM, for 6D pose refinement. The correspondence-based method mainly uses CNN to detect keypoints, then uses algorithms such as PnP to establish 2D-3D correspondence and obtain the 6D pose: Li et al. [33] propose a coordinate-based disentangled pose network to characterize the rotation and translation of objects, which unifies the indirect PnP strategy and the direct regression strategy to estimate object pose. Zakharov et al. [34] propose the DPOD method to estimate dense multi-class 2D-3D correspondence between input images and known 3D models, utilizing PnP and RANSAC algorithms to estimate object poses.

2.2. Pose Estimation from RGB-D Images

The RGB-D-based method attempts to estimate the pose of weakly textured or occluded objects by depth or point cloud information. The RGB-D-based method can be categorized into two types: direct regression methods [35,36] and two-stage methods [37,38]. The direct regression method predicts object poses using features of RGB-D data. For example, DenseFusion uses CNNs and PointNet to extract features from RGB images and point clouds, respectively, and then integrates them using a specific feature fusion method to estimate the object pose. Petitjean et al. [39] propose a robust 6D pose estimation method based on quality the evaluation of RGB-D fusion, which can improve robustness for low-quality depth and RGB inputs. The two-stage method first establishes correspondences between 2D and 3D information using PnP and other algorithms, and then calculates the 6D pose using a least squares algorithm. For example, PVN3D [40] integrates RGB and point cloud information to generate 3D keypoints using a full-pixel voting network. PointPoseNet [41] takes a point cloud as input and regresses per-point unit vectors, which point into 3D keypoints. The frameworks of direct regression and two-stage methods differ; most researchers focus on the fusion of point cloud and RGB data [42,43,44], whereas our study focuses on the richness and effectiveness of feature information.

3. Method

3.1. Overall Process

Six-dimensional target pose estimation adopts known pose models to predict the 6D pose of real-world objects. DenseFusion takes segmented images as real scenes, and uses CNN and improved PointNet to extract color features and point cloud features for deep fusion. Therefore, feature extraction is an extremely crucial step, where the effectiveness and richness of color features and point cloud features have a significant impact on the accuracy of pose estimation. We improve DenseFusion by enhancing feature information.

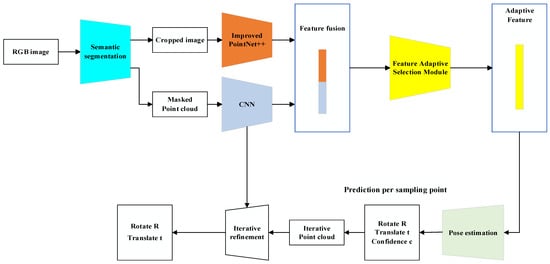

The algorithm framework is shown in Figure 1, consisting of three main parts. The first part involves semantic segmentation of RGB images. Firstly, the color and depth maps are cropped based on the mask bounding box; subsequently, the depth values within the masked region are converted into a point cloud. The second part involves feature extraction and fusion. First, we use CNN and an improved PointNet++ to extract color and point cloud features. Second, we fuse the color and point cloud features at each pixel level. Then, the fused features are input into the adaptive feature selection module to generate adaptive features for each sampling point. The third part performs pose estimation by passing the adaptive features into the supervised pose estimation network, which predicts the pose of each sampling point; and outputs the pose estimation result with the highest confidence level. Finally, the pose iteration module of DenseFusion is applied to further improve the accuracy of pose estimation.

Figure 1.

Overall network framework.

3.2. Semantic Segmentation

The semantic segmentation framework consists of an encoder and a decoder, which encode and decode color images to generate N+1 channel result maps. We use the semantic segmentation network in PoseCNN [20] to crop images. It crops target objects from RGB-D images, ultimately generating color and depth maps that contain information about targets. Finally, we convert the depth map of the mask position into the point cloud using the camera intrinsic parameters. The formula is as follows:

where (, ) is the position coordinate of each pixel in the depth map, (, , ) is the 3D position coordinate of the point cloud, d is the depth data of the pixel at (, ), is the camera scale factor, (, ) is the camera center coordinate and (, ) is the focal length of the camera on the x and y axis, respectively.

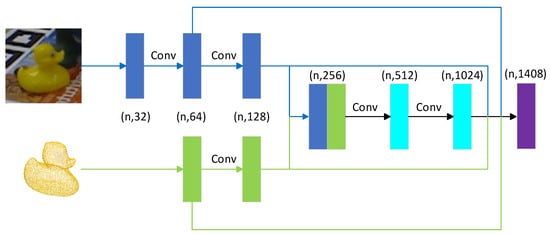

3.3. Feature Extraction and Fusion

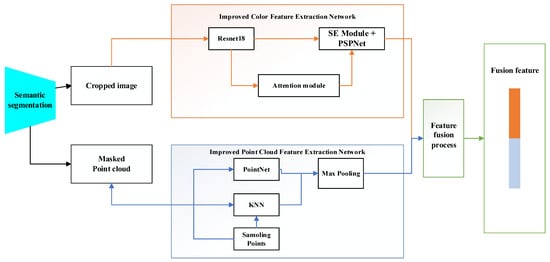

As shown in Figure 2, the cropped image and masked point cloud are obtained through semantic segmentation. The cropped image is processed by the Improved Color Feature Extraction Network, and the masked point cloud is processed by the Improved Point Cloud Feature Extraction Network. The resulting image and point cloud features are subsequently fused by the Feature Fusion Network to produce a fusion feature. The detailed design of each network will be described in the following section.

Figure 2.

Proposed feature extraction and fusion framework.

3.3.1. Color Feature Extraction

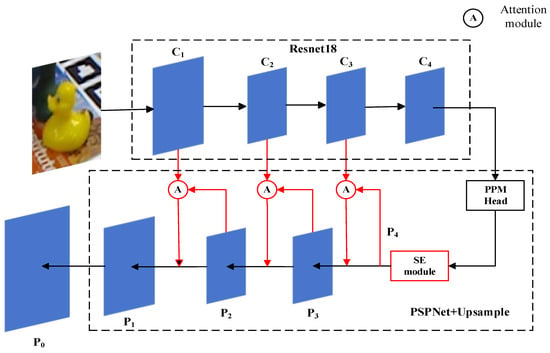

DenseFusion constructs a network to extract color features, applying ResNet [45] as the encoder and PSPNet [46] as the decoder. The extracted deep features contain rich semantic information. However, multiple convolution layers could cause the loss of positional information, resulting in incomplete semantic information of deep features. To solve this issue, we add skip connections and attention mechanism modules into the network, as shown in the red part of Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Improved Color Feature Extraction Network.

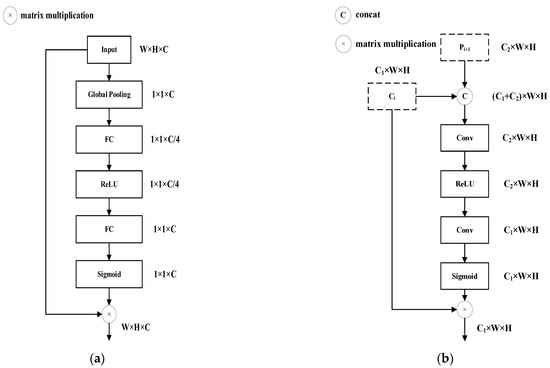

We first add a Squeeze and Excitation (SE) module [47] after the Pyramid Pooling Module (PPM), then add an attention mechanism module [48] into the connection channel between the encoding and decoding processes. The SE module and the attention mechanism module are shown in Figure 4. The SE module obtains an attention-weighted graph through global pooling, fully connected layers, and a sigmoid function; subsequently, the attention-weighted graph assigns weights to input channels. The attention mechanism module takes the current level feature Ci of ResNet and the higher-level feature Pi+1 of the upsampling layer as inputs. Through two convolutional layers and a sigmoid function, the attention-weighted graph, the same size as Ci, is generated. Then the weighted Ci is added to Pi+1 via a skip connection.

Figure 4.

(a) Image of SE module; (b) image of attention mechanism module.

Through the attention mechanism module and skip connection, the network can more effectively utilize low-level features, obtain more effective contextual semantic information, and consequently improve the accuracy of pose estimation. In addition, because the size of the input segmented image is small, the image size in the four Bottlenecks of ResNet is only reduced by half, thereby retaining more feature information. When the sizes of Ci and Pi+1 are different, Pi+1 achieves double upsampling through the bilinear interpolation algorithm. Finally, P1 is sampled into the feature map P0 which is the same size as the input image.

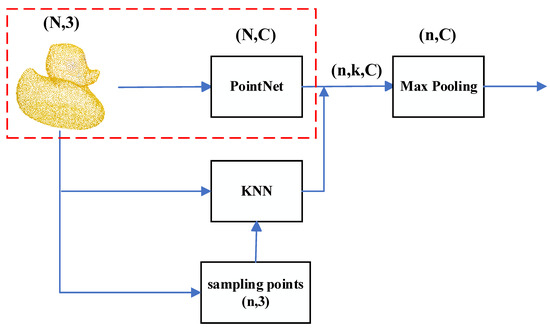

3.3.2. Point Cloud Feature Extraction

DenseFusion only uses PointNet for feature extraction from randomly sampled points, which limits the precision of the extracted features and results in a lack of semantic information in the point cloud. To obtain more comprehensive extract point cloud features, we improve PointNet++ using the K-nearest neighbor (KNN) method, max pooling, and random sampling. The process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Improved Point Cloud Feature Extraction Network.

Firstly, PointNet is employed to perform initial feature extraction of the point cloud data. The network input is the (N × 3) point cloud, which is converted from the masked depth map. N denotes the number of points in the masked point cloud, and 3 represents the three-dimensional spatial coordinates. The point cloud (n × 3) is randomly sampled from the mask point cloud (N × 3). Subsequently, the K-nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm is applied to compute the neighbor feature indices of each randomly sampled point, thereby constructing a local feature matrix of size (n × k × C). Finally, local features are aggregated through max pooling. In this study we set k = 6 to balance local geometric information and computational overhead. A smaller k may lead to the loss of local structures, whereas an excessively large k could introduce background noise and increase computational cost. In addition, the farthest point sampling method often mostly focuses on sampling edge points, since errors in semantic segmentation masks are often concentrated at the edges, which increases the likelihood of invalid points in farthest point sampling. Therefore, random sampling is adopted to improve pose estimation accuracy.

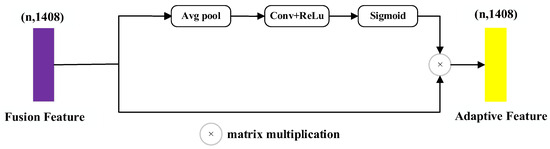

3.3.3. Feature Fusion

So far, we have obtained dense features from both the image and the 3D point cloud. The two features are fused by their corresponding coordinate relationship, and dense RGB-D features are generated. The fusion steps are shown in Figure 6. In addition, we believe that there is no fixed hierarchical distinction between point clouds and images; their importance may change in different scenarios. Therefore, in the final output section, we introduce an adaptive feature selection module to obtain more accurate feature information.

Figure 6.

Feature fusion process.

The adaptive feature selection module weighs the channel dimension to determine whether color features or point cloud features are more suitable for the current scene. Through global pooling layers, convolutional layers, ReLU function, and Sigmoid function, the fused features are processed to obtain an attention-weighted image, which is the same size as the input channel. The adaptive feature selection module is shown in Figure 7. The adaptive feature selection module ensures that the minimum weight of the channel is 0.5, which not only performs channel filtering, but also effectively preserves the basic information of all channels.

Figure 7.

Fature adaptive selection module.

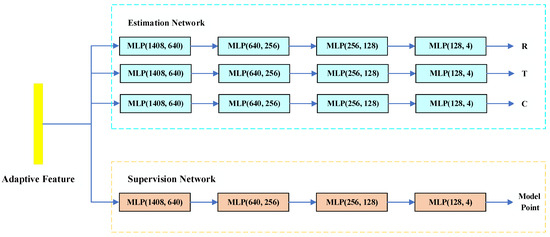

3.3.4. Pose Estimation and Refinement

Through the above steps, we obtain the fused features of the sample points. In the pose estimation stage, the fused features are fed into the neural network, where they are used to regress the rotation matrix R, the translation vector T, and the confidence score c. The pose estimation network of DenseFusion consists of three identical small networks, each containing four layers of one-dimensional convolution. The network loss function is set as follows:

where represents the number of fused features. represents the confidence score of the regression pose. Higher confidence scores indicate higher accuracy of pose parameters. w represents a balancing hyperparameter. represents the pose loss of the ith fused feature; The loss formula of asymmetric objects is as follows:

This formula represents the average distance between each corresponding coordinate of the sampled point cloud under the ground-truth pose and the estimated pose. is a point cloud randomly selected from the target model. is the jth point cloud in the dataset of random point clouds. is the coordinate from the real pose transformation. is the estimated coordinate after the ith fusion feature.

Although the loss function (3) is clearly defined for asymmetric objects, symmetric objects do not have unique normative frames. Therefore, the loss function is the average distance between each corresponding point of the estimated model and the closest point of the ground truth model. The formula is as follows:

We add a supervised network into the original pose estimation network; this network directly supervises the prediction of model points. Since both networks have the same adaptive features as inputs, the regressed 6D pose of the estimation network is aligned with the standard model point cloud predicted by the supervised network; their outputs remain consistent. Compared to using only estimation networks to regress 6D poses, the supervised network provides auxiliary supervision for training the estimation network. Supervised networks are used to train feature extraction networks to output more refined features, which improves the accuracy of predicting poses. The estimation networks and the supervised network are shown in Figure 8, where the blue frame represents the estimation networks; the orange frame represents the supervised network, which outputs the predicted CAD model point cloud.

Figure 8.

Structure of estimation network and supervision network.

In the supervision network, we calculate the gap between the predicted point cloud q and the CAD model point cloud y, then calculate the average value of the gap, for asymmetric objects:

For symmetric objects:

Finally, and are summed as the total loss, and the hyperparameters is applied to balance the two losses. We set = 0.05 to reduce the dominance of the reconstruction loss from the supervision network in pose regression, ensuring that the supervision serves as an auxiliary signal rather than substituting the primary task:

After obtaining the results of pose estimation, we perform pose refinement to achieve better results. The common refinement method, ICP, is too time-consuming to satisfy the requirements of real-time applications. Referring to DenseFusion, we employ a CNN-based refinement method comprising three fully connected layers. The fused features are transformed into global features by a max pooling layer, and the iterative network simultaneously outputs the residual pose. After k iterations, the predicted residual pose is cascaded with the original pose to obtain the final pose, which is shown in Formula (8):

where represents the residual attitude result after the kth iteration, and represents the initial pose output of the pose estimation network.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. LineMOD Dataset

The LineMOD dataset consists of video frame images of 13 weakly textured objects; the images of eggbox and glue have rotational symmetry. It is a benchmark dataset used for object pose estimation. The LineMOD dataset features cluttered scenes, varying lighting conditions, and weak object textures.

4.1.2. Occlusion LineMOD Dataset

The Occlusion LineMOD dataset is created by adding annotations to each scene on the LineMOD dataset, and each image is significantly obscured. It is suitable for detecting the effectiveness of algorithms in estimating the pose of occluded objects.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate the accuracy of pose estimation by the average distance (ADD) and the average closest point distance (ADD-S). For asymmetric objects, ADD is used as an evaluation metric, which calculates the average distance between the corresponding point pairs of the target model point cloud in both the real pose and the estimated pose. The definition of ADD is as follows:

where M represents the point set of the target model point cloud. [|] denotes the ground truth pose. [|] denotes the estimated pose. For symmetric objects, ADD-S is used as an evaluation metric, which calculates the average distance between each point of the estimated model and the closest point of the ground truth model. The definition of ADD-S is as follows:

If the average distance is less than 10% of the target’s diameter, we think the estimated 6D pose is considered correct.

4.3. Implementation Details

The experiment is conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 2060 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), utilizing software platforms that include CUDA 11.1, PyTorch 1.8, and Python 3.6. During the training process, we follow the settings in NF6D [26], using 15% of the images for training and the remaining images for testing. For the LineMOD dataset, the training dataset contains 2372 RGB-D images, and the test dataset contains 13,406 RGB-D images. For the Occlusion LineMOD dataset, 181 images are used for training, and 1031 images are used for testing. The training process is repeated 20 times for each epoch. Due to the varying image sizes obtained through semantic segmentation, only one image can be used per extraction in the CNN stage. To accelerate the acquisition of training results, we utilize a single category for training. Firstly, we train the pose estimation backbone network until convergence. Secondly, we train the refinement network. The optimal parameters are determined through tuning as follows: the batch size is 8, the maximum epoch of iterative training is 500, the learning rate is 0.0001, the loss function hyperparameter w is 0.015, both the learning decay rate and the hyperparameter decay rate are set as 0.35, and the iteration number of the network is 2.

4.4. Results on the Datasets

4.4.1. Result on the LineMOD Dataset

Table 1 presents the performance comparison between the proposed method and classic RGB and RGB-D methods on the LineMOD dataset. Symmetric objects are shown in bold in Table 1. Bold numbers indicate relatively higher performance metrics. The experimental results show that the pose estimation accuracy of our proposed method is 99.2% on the LineMOD dataset. Under the same pose optimization strategy, compared with representative RGB methods such as RNNPose [49], CDPN, DPOD, and RKDT [50], the accuracy of our proposed method is improved by 1.7%, 9.2%, 3.9%, and 6.2%, respectively. Compared to DenseFusion, our method improves pose estimation accuracy for all 13 objects on the LineMOD dataset and has an overall average accuracy improvement of 4.8%. Compared with representative RGB-D methods such as NF6D, Uni6D [42], Uni6Dv2 [43], and CA6D [44], our method achieves accuracy improvements of 2.3%, 1.7%, 1.5%, and 1.2%, respectively, and is only slightly inferior to FFB6D [25].

Table 1.

Pose estimation results of the LineMOD dataset. Objects with bold name are symmetric.

Experimental results demonstrate that, compared with recent methods such as Uni6D and CA6D, our approach exhibits distinct advantages in feature representation and fusion strategy. Uni6D primarily mitigates projection errors through a unified framework, while CA6D enhances robustness via context modeling. In contrast, our method strengthens the feature representations of both images and point clouds prior to fusion Further, it incorporates an adaptive feature selection module during fusion to dynamically balance the contributions of the two modalities. In addition, a supervision network aligns with the CAD model geometry to impose further constraints on feature learning. Consequently, our method achieves stronger scene adaptability and robustness while maintaining lightweight characteristics.

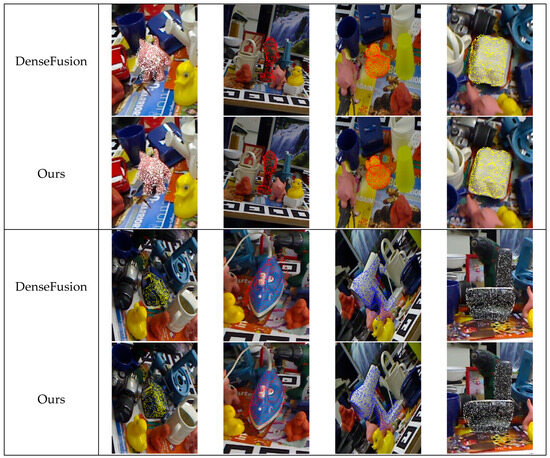

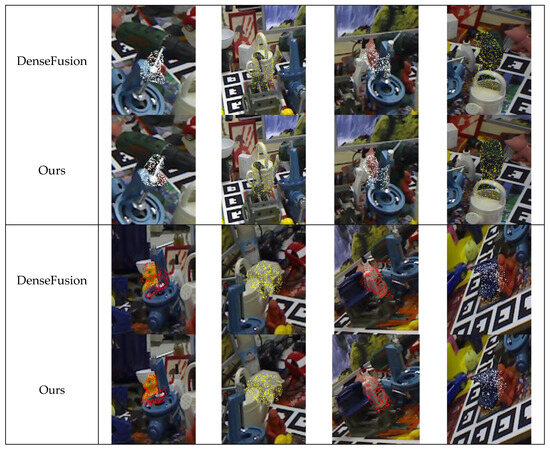

In addition, we apply rotation and translation to the point cloud model, and then project it onto the image to visually compare our method with DenseFusion on the LineMOD and Occlusion LineMOD datasets, as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10. Each box displays the results of four types of objects. As shown in Figure 9, for the same object in the same scene, the estimation error of DenseFusion exceeds the threshold. In contrast, the error of our method remains within the allowable range, demonstrating the effectiveness of our method.

Figure 9.

Visualization comparison of partial results of LineMOD dataset.

Figure 10.

Visualization comparison of partial results of Occlusion LineMOD dataset.

4.4.2. Result of the Occlusion LineMOD Dataset

For the Occlusion LineMOD dataset, our method is compared with FFB6D, DenseFusion and NF6D. The accuracy has been improved by 26.9%, 2.5%, and 0.3% compared with FFB6D, DenseFusion, and NF6D, respectively. Figure 10 shows that, compared with DenseFusion, our method exhibits better performance on seven occluded objects, except for the driller, which is consistent with the results in Table 2. Bold numbers indicate relatively higher performance metrics. Specifically, our method performs well on all other targets except for the ape and duck. After analyzing the experimental results, we conclude that the severe occlusion of the two objects results in only a small portion being visible. Consequently, the features extracted from color images and point clouds are significantly influenced by background interference, resulting in insufficient and ineffective feature representations. This suggests that, under extremely severe occlusion scenarios, even our enhanced feature extraction network may not be able to extract sufficiently effective image and point cloud features for fusion and enhancement, thereby leading to suboptimal subsequent pose estimation.

Table 2.

Pose estimation results of the Occlusion LineMOD dataset.

At the same time, the comparison with FFB6D is noteworthy. While our method is slightly inferior to FFB6D on the LineMOD dataset, it substantially outperforms FFB6D on the Occlusion LineMOD dataset. This not only validates the effectiveness of our feature utilization and enhancement strategy but also demonstrates the superiority of our approach under severe occlusion. The reason for this lies in the design of FFB6D, which performs static bidirectional fusion at each encoding and decoding layer. Although this ensures sufficient information interaction, it incurs high computational complexity and neglects the varying importance of different modalities across diverse scenarios. In contrast, our method enhances image and point cloud features separately prior to fusion. It incorporates an adaptive feature selection module during fusion to dynamically adjust the weights of the two modalities. In addition, an auxiliary supervision network aligns the learned features with CAD model geometry, further constraining feature learning. As a result, our approach maintains lightweight characteristics while achieving stronger scene adaptability and robustness.

4.4.3. Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the performance of various improvements, we conduct several ablation experiments. Firstly, we compare the performance of DenseFusion with three different settings:

- Improving only the color feature extraction network.

- Improving only the point cloud feature extraction network.

- Improving both, all under the setting without the refinement network.

As shown in Table 3, both the improved image feature extraction network and the Improved Point Cloud Feature Extraction Network outperform the original DenseFusion algorithm, with a notable enhancement in pose estimation accuracy for thirteen objects. Bold numbers indicate relatively higher performance metrics. The average accuracy is increased by 8.4% and 4.5% over DenseFusion, respectively. The experimental results indicate that the improved image feature network is notably superior to the point cloud network because it can effectively integrate shallow feature information and enrich the semantic content of deep features. Although the improvement in the point cloud network enhances feature extraction capability, a substantial gap remains in terms of semantic information density. When both improved networks are employed simultaneously, their performance increases by 0.9% and 4.7%, respectively, compared to using only the image feature network or only the point cloud feature network. Moreover, the accuracy of pose estimation for test objects is improved. This demonstrates the complementary mechanism of the two modal features. Image features supply rich semantic information, while point cloud features enhance geometric representation. The synergistic effect of the two-types of feature significantly improves the overall performance of the system.

Table 3.

Evaluation of extraction networks. Objects with bold name are symmetric.

In addition, based on the improved feature extraction network, we evaluate the impact of incorporating the adaptive feature selection module and the supervised network on pose optimization. Table 4 shows that incorporating the adaptive feature selection module and the supervised network enhances the accuracy of target pose estimation. Bold numbers indicate relatively higher performance metrics. Specifically, besides slightly worse performance on cats, the pose estimation accuracy of all other targets is satisfactory. After adding a supervised network, the average estimation accuracy increases by 1.8%. After adding a feature adaptive selection step, the average estimation accuracy increases by 1.9%. When the two networks are combined, the average estimation accuracy increases by 2.6%.

Table 4.

Evaluation of supervision network and adaptive feature selection module. Objects with bold name are symmetric.

The ablation results indicate that enhancing the color feature extraction network leads to a substantially larger performance improvement than the enhancements of the point cloud network, the supervision module, or the adaptive feature selection network. This is mainly because RGB images, even under weak-texture or partially occluded conditions, still provide relatively rich semantic and boundary information. Skip connections help preserve fine spatial details from shallow layers, while the attention mechanism highlights the most important features, together enhancing the complementarity between shallow and deep features. In contrast, point cloud features, although useful for capturing local geometric structures, contribute less due to sampling sparsity, depth noise, and limited global semantic information. The adaptive feature selection network dynamically balances the contributions of RGB and point cloud features, thereby further enhancing feature fusion. The supervision network primarily facilitates feature alignment and stabilizes training, resulting in a relatively limited standalone contribution.

5. Conclusions

We have made two improvements to the feature extraction network to address the problem of insufficient and ineffective feature extraction. The first improvement introduces skip connections and attention mechanism modules into the CNN, enabling the network to fully utilize shallow features and effectively highlight the semantic information of deep features. The second improvement utilizes the enhanced PointNet++ for point cloud processing, thereby addressing the insufficient semantic information provided by the original PointNet. The experimental results indicate that the improved feature extraction networks can extract richer and more effective semantic information, effectively integrating image and point cloud features. Whether the improved feature extraction networks are applied individually or in combination, the accuracy of pose estimation can be enhanced. Additionally, we believe that there is no primary distinction between point clouds and images. The relative importance of point clouds and images may change in different scenarios. Therefore, in the final output section, this study introduces an adaptive feature selection module to obtain more accurate feature information for pose estimation. Finally, a supervised network is introduced to output more refined features for matching the regressed 6D pose of the estimation network. The experimental results demonstrate that our method significantly outperforms DenseFusion and other approaches, with real-time performance and accuracy in pose estimation effectively improved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and K.Z.; methodology, X.L.; software, Q.Z.; validation, X.L., K.Z. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, Q.Z.; data curation, Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, K.Z.; visualization, Q.Z.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, P.L.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 61773330), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2020YFA0713501), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (grant number 2021JJ50126).

Data Availability Statement

This study used publicly available datasets. The LineMOD and Occlusion LineMOD datasets are available as part of the BOP benchmark at https://bop.felk.cvut.cz (accessed on 22 September 2024). These datasets were used for evaluation purposes and were not modified during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; Liang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Yan, Z. Deep-Learning-Enhanced Multitarget Detection for End–Edge–Cloud Surveillance in Smart IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12588–12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, R.; Wang, X.; Tu, W.; Zhang, M. Nonlinear Prediction with Deep Recurrent Neural Networks for Non-Blind Audio Bandwidth Extension. China Commun. 2018, 15, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, W. CNN-RNN Based Intelligent Recommendation for Online Medical Pre-Diagnosis Support. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2021, 18, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S. A Novel Study on Deep Learning Framework to Predict and Analyze the Financial Time Series Information. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 125, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Zheng, H. A Mortality Risk Assessment Approach on ICU Patients Clinical Medication Events Using Deep Learning. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2021, 128, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Wang, K.I.K.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.T.; Jin, Q. Deep-Learning-Enhanced Human Activity Recognition for Internet of Healthcare Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6429–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Li, W.; Yan, K.; Shimizu, S.; Wang, K.I.K. Hierarchical Adversarial Attacks Against Graph-Neural-Network-Based IoT Network Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 9310–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5099–5108. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3295222.3295263 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Lv, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, C. Deep Supervision and Atrous Inception-Based U-Net Combining CRF for Automatic Liver Segmentation from CT. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chen, Z. English Text Quality Analysis Based on Recurrent Neural Network and Semantic Segmentation. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 112, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Sun, W. Point-by-Point Feature Extraction of Artificial Intelligence Images Based on the Internet of Things. Comput. Commun. 2020, 159, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, K.; Dong, L.; Pan, C.; Xu, W.; Yang, K. AI Driven Heterogeneous MEC System with UAV Assistance for Dynamic Environment: Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Netw. 2021, 35, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Yu, X. Pharmaceutical Cold Chain Management Based on Blockchain and Deep Learning. J. Internet Technol. 2021, 22, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Wang, K.I.K.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.T.; Jin, Q. Edge-Enabled Two-Stage Scheduling Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for Internet of Everything. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3295–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z. Efficient Complex ISAR Object Recognition Using Adaptive Deep Relation Learning. IET Comput. Vis. 2020, 14, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X. Research on Investment Portfolio Model Based on Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm in Big Data Era. J. Wirel. Com. Netw. 2020, 2020, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, G.S.; Meesala, M.K.; Addula, S.R.; Ravipati, P. Optimizing Retail Supply Chain Sales Forecasting with a Mayfly Algorithm-Enhanced Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Bao, H. PVNet: Pixel-Wise Voting Network for 6DoF Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4556–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugurov, I.; Li, F.; Busam, B.; Ilic, S. OSOP: A Multi-Stage One Shot Object Pose Estimation Framework. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 6825–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Schmidt, T.; Narayanan, V.; Fox, D. Posecnn: A convolutional neural network for 6d object pose estimation in cluttered scenes. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.00199. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Liu, W.; Wu, C.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. Frustum PointNets for 3D Object Detection from RGB-D Data. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Anguelov, D.; Jain, A. PointFusion: Deep Sensor Fusion for 3D Bounding Box Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Martín-Martín, R.; Lu, C.; Fei-Fei, L.; Savarese, S. DenseFusion: 6D Object Pose Estimation by Iterative Dense Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 June 2017; pp. 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Huang, H.; Fan, H.; Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Yi, L. FFB6D: A Full Flow Bidirectional Fusion Network for 6D Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3003–3013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Yao, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, Q. A Novel Depth and Color Feature Fusion Framework for 6D Object Pose Estimation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 23, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Manhardt, F.; Tombari, F.; Ji, X. GDR-Net: Geometry-Guided Direct Regression Network for Monocular 6D Object Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 16606–16616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.T.; Cai, M.; Pham, T.; Reid, I. Deep-6DPose: Recovering 6D Object Pose from a Single RGB Image. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Patten, T.; Vincze, M. Pix2Pose: Pixel-Wise Coordinate Regression of Objects for 6D Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7667–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Chen, S.; Ma, X.; Xu, Y. An Efficient Optimization Framework for 6D Pose Estimation in Terminal Vision Guidance of AUV Docking. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Robotics and Computer Vision (ICRCV), Nanjing, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Fua, P.; Wang, W.; Salzmann, M. Single-Stage 6D Object Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2927–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, A.; Savakis, A. DeepRM: Deep Recurrent Matching for 6D Pose Refinement. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–20 June 2023; pp. 6206–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Ji, X. CDPN: Coordinates-Based Disentangled Pose Network for Real-Time RGB-Based 6-DoF Object Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7677–7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, S.; Shugurov, I.; Ilic, S. DPOD: 6D Pose Object Detector and Refiner. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Xie, L.; Pan, H.; Wang, Z. A Lightweight Two-End Feature Fusion Network for Object 6D Pose Estimation. Machines 2022, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl, W.; Manhardt, F.; Tombari, F.; Ilic, S.; Navab, N. SSD-6D: Making RGB-Based 3D Detection and 6D Pose Estimation Great Again. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y. NeRF-Pose: A First-Reconstruct-Then-Regress Approach for Weakly-Supervised 6D Object Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Paris, France, 1–2 October 2023; pp. 2115–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugurov, I.; Zakharov, S.; Ilic, S. DPODv2: Dense Correspondence-Based 6 DoF Pose Estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 7417–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitjean, T.; Wu, Z.; Laligant, O.; Demonceaux, C. QaQ: Robust 6D Pose Estimation via Quality-Assessed RGB-D Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications (MVA), Hamamatsu, Japan, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sun, W.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Fan, H.; Sun, J. PVN3D: A Deep Point-Wise 3D Keypoints Voting Network for 6DoF Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11629–11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Duan, J.; Basevi, H.; Chang, H.J.; Leonardis, A. PointPoseNet: Point Pose Network for Robust 6D Object Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Snowmass, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 2813–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, D.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wu, L. Uni6D: A Unified CNN Framework without Projection Breakdown for 6D Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 11164–11174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zheng, Y.; Bao, T.; Chen, J.; Jin, G.; Wu, L.; Zhao, R.; Jiang, X. Uni6Dv2: Noise Elimination for 6D Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 May 2023; pp. 1832–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Shukla, P.; Kushwaha, V.; Nandi, G.C. Context-Aware 6D Pose Estimation of Known Objects Using RGB-D Data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.05560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6230–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Situ, H.; Zhuang, C. 6D Pose Estimation for Bin-Picking Based on Improved Mask R-CNN and DenseFusion. In Proceedings of the 2021 26th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Vasteras, Sweden, 7–10 September 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, K.-Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Li, H. RNNPose: 6-DoF Object Pose Estimation via Recurrent Correspondence Field Estimation and Pose Optimization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 4669–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, X.; Yang, B.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, B. RGB-Based Set Prediction Transformer of 6D Pose Estimation for Robotic Grasping Application. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 138047–138060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).