Abstract

Video-based point cloud compression (V-PCC) is a 3D point cloud compression standard that first projects the point cloud from 3D space onto 2D space, thereby generating geometric and attribute videos, and then encodes the geometric and attribute videos using high-efficiency video coding (HEVC). In the whole coding process, the coding of geometric videos is extremely time-consuming, mainly because the division of geometric video coding units has high computational complexity. In order to effectively reduce the coding complexity of geometric videos in video-based point cloud compression, we propose a fast segmentation algorithm based on the occupancy type of coding units. First, the CUs are divided into three categories—unoccupied, partially occupied, and fully occupied—based on the occupancy graph. For unoccupied CUs, the segmentation is terminated immediately; for partially occupied CUs, a geometric visual perception factor is designed based on their spatial depth variation characteristics, thus realizing early depth range skipping based on visual sensitivity; and, for fully occupied CUs, a lightweight fully connected network is used to make the fast segmentation decision. The experimental results show that, under the full intra-frame configuration, this algorithm significantly reduces the coding time complexity while almost maintaining the coding quality; i.e., the BD rate of D1 and D2 only increases by an average of 0.11% and 0.28% under the total coding rate, where the geometric video coding time saving reaches up to 58.71% and the overall V-PCC coding time saving reaches up to 53.96%.

1. Introduction

With the increasing maturity of 3D acquisition technologies, 3D point cloud data have become an important data representation in cutting-edge fields such as autonomous driving, digital cultural heritage, and virtual reality (VR) due to their ability to provide highly immersive visual experiences [1,2,3]. However, point cloud data not only contain a large amount of geometric structural information, but also include rich attribute features, which lead to a sharp increase in data volume and pose serious challenges for real-time data transmission and efficient storage [4]. In this context, it is particularly important to develop efficient and fast point cloud compression methods.

The Motion Picture Experts Group (MPEG) has proposed two standards with different strategies for point cloud compression: the geometry-based G-PCC [5] and the video-based V-PCC [6,7,8]. G-PCC is suitable for both static and dynamically captured point clouds and deals directly with the 3D point cloud itself, compressing either static or dynamic data by exploring the spatial and temporal correlation of the point cloud [9,10]. In contrast, V-PCC is designed for dynamic point clouds, and its core idea is to project 3D point cloud data into 2D image sequences, which are then compressed using proven 2D video coding techniques [11]. The research in this paper focuses on the optimization of V-PCC.

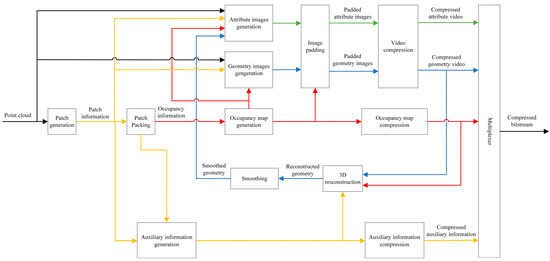

The V-PCC coding framework is shown in Figure 1. Specifically, V-PCC first divides the point cloud sequence into 3D facets and then projects each 3D facet independently into a 2D facet to produce three images, an occupancy map, a geometric image, and an attribute image [12], as shown in Figure 2. Among them, the occupancy map is a binary image indicating whether a pixel corresponds to a valid 3D projection point; the geometric image contains depth information indicating the distance between the position of each point and the projection plane; and the attribute video contains texture and color information. Finally, lossless compression is performed on the occupancy map, while lossy compression is performed on the geometric and attribute images using a conventional 2D video encoder (High-Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC) is considered in this work) [13]. Therefore, the key to improving the compression efficiency of V-PCC is to optimize the coding performance of its 2D projection video [14]. However, the projected geometric video has a double frame rate and high resolution, which creates a heavy computational burden in the coding process and severely limits the practical application of V-PCC. Therefore, designing efficient and fast coding algorithms for 2D projected geometric videos to ultimately realize fast V-PCC compression is a key problem to be solved.

Figure 1.

V-PCC coding framework diagram.

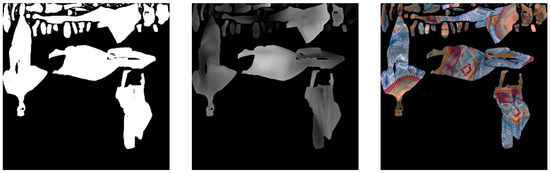

Figure 2.

Occupancy, geometry, and attribute maps.

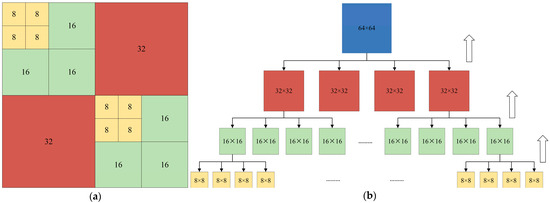

CU division is the first stage in High-Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC), and the CU division framework diagram is shown in Figure 3. In the HEVC coding process, the video frame is first segmented into fixed-size 64 × 64 coding tree units (CTUs). Subsequently, each CTU explores all possible segmentation modes, including quadtree (QT) segmentation or no segmentation, in a recursive manner until reaching the minimum permissible block size of 8 × 8. In order to determine the optimal segmentation structure, the encoder makes decisions based on the rate-distortion optimization (RDO) criterion; i.e., it performs a complete coding process including prediction, transform, quantization, and other operations for each possible segmentation mode and calculates the corresponding rate-distortion cost. Ultimately, the encoder selects the least costly division scheme as the optimal coding structure by comparing the rate-distortion cost of all candidate patterns, and this decision-making process based on RDO is one of the main sources of computational complexity in HEVC [15,16]. Obviously, this leads to very high computational complexity. Therefore, it is feasible to propose algorithms to speed up the CU division of geometric videos and reduce unnecessary RDO overhead so as to realize the fast coding of V-PCC.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic diagram of the quadtree division of CU. (b) Detailed process of CU division.

Although there are many studies aimed at speeding up the CU division of HEVC and reducing its coding complexity, they are mainly designed for natural videos without considering the characteristics of point clouds, which may not be suitable for geometrically projected videos in V-PCC and are less efficient when applied directly to V-PCC. This is because the geometric projection video has different characteristics; unlike the continuous and uniformly textured natural video, the geometric video has a large number of empty pixels and is affected by geometric structure and block arrangement rules, which exhibit irregular shapes and significant discontinuities between neighboring blocks. Therefore, it is necessary to design specialized algorithms for geometric videos to achieve the fast CU segmentation and fast compression of V-PCC.

Aiming at the problem of the high computational complexity of geometric video coding unit (CU) division, we propose an efficient fast CU division algorithm for geometric videos based on the characteristics of geometric videos, aiming at significantly reducing the coding time. The core innovations of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The CU blocks of geometric videos are categorized into three types, unoccupied blocks, partially occupied blocks, and fully occupied blocks, based on the occupancy map, and the corresponding fast CU segmentation strategies are carried out for CUs of different occupancy types. For occupied blocks, in order to determine the segmentation pattern more accurately, we statistically analyze the non-segmentation probability of unoccupied blocks in different sequences and calculate the mean absolute deviation (MAD_AP) between adjacent pixels to evaluate the complexity of unoccupied blocks, and, finally, conclude that the segmentation of unoccupied blocks is terminated directly.

- (2)

- In order to divide partially occupied blocks more accurately, we design the geometric visual perception factor, GVP, in combination with the characteristic of varying spatial depths of partially occupied blocks, and categorize partially occupied blocks according to the sensitivity degree based on GVP, and then statistically analyze the optimal range of the dividing depths of partially CU blocks with different visual sensitivity degree categories, so as to skip the dividing depths outside the optimal depth range in advance.

- (3)

- For fully occupied blocks, in order to more accurately realize the early division decision, we extract the direct and indirect features of fully occupied CUs and design the lightweight network, and then put the extracted features into the trained lightweight network to output a value, and determine whether the CU needs to be further divided or not by comparing the output value with the threshold size.

- (4)

- The experimental results show that our algorithm can guarantee a small quality loss while substantially reducing the time complexity. In particular, the coding time saving for geometric videos is 58.71%, and the overall coding time saving for V-PCC reaches 53.96%, while the average BD rates of the D1 and D2 components are slightly increased by 0.11% and 0.28%, respectively, at the total bit rate.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the research related to fast CU segmentation for HEVC and V-PCC; Section 3 describes in detail the algorithm proposed in this paper, including the early termination of the segmentation of unoccupied blocks, the early skipping of the segmentation of partially occupied blocks, and the early segmentation decision of fully occupied blocks; Section 4 summarizes the overall algorithmic flow; Section 5 demonstrates the experimental results of the proposed algorithm; and Section 6 provides a summary of the overall algorithm.

2. Related Work

In this section, we review the fast CU segmentation algorithms in HEVC and the fast CU segmentation algorithms in V-PCC when coding with the 2D encoder HEVC, and analyze the features of the existing methods so as to propose our fast CU segmentation algorithm for geometric videos.

2.1. Fast CU Segmentation Algorithm in HEVC

In the V-PCC framework, when the geometric video is coded using High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC), the coding complexity of HEVC directly affects the overall coding efficiency of V-PCC. Among them, the coding unit (CU) size decision-making process of HEVC is one of the key factors leading to its high computational complexity. To address this problem, academics have proposed a variety of methods to optimize the fast CU division for HEVC. For example, the researchers Ahn et al. [17] designed an efficient CU segmentation acceleration strategy for inter-frame coding by exploiting spatio-temporal coding parameters, which mainly contains an optimized early CU detection and CU segmentation decision scheme. Meanwhile, Kuo et al. [18] proposed a depth range prediction method based on temporal correlation (utilizing the previous frame information) and spatial correlation (referring to the coding data of neighboring CTUs), which effectively reduces the redundant CU delineation computation. In order to quickly determine the size of the optimal CU, Hou et al. [19] skipped the further division of the texture uniform region by calculating the texture complexity of the current CU and predicted the optimal division depth based on the division information of the neighboring CUs, thus reducing the evaluation range. Li et al. [20] proposed a CU depth prediction method based on spatial correlation and rate distortion (RD) cost analysis, which effectively reduces the coding time by establishing an adaptive thresholding mechanism to terminate the segmentation process early when the rate distortion cost of CUs is lower than a set threshold.

With the rapid development of machine-learning techniques, a variety of machine-learning methods have been introduced for fast CU division optimization in HEVC. Typical methods include Bayesian, Markov random field, decision tree, and support vector machine [21,22,23,24,25]. Among them, Chen et al. [21] designed an innovative cascaded Bayesian classification framework: the scheme adopts a two-stage classifier cascade structure, which firstly utilizes a three-class classifier to divide the CUs into undivided, divided, and fuzzy regions, and then uses a two-class classifier to divide the fuzzy regions into divided and undivided regions, and the classifier thresholds are set according to the Bayesian risk, which can realize the coding quality balancing. Werda et al. [25] used a fuzzy support vector machine (FSVM)-based approach to predict coding decisions without calculating the RD cost, which saves a lot of computational time used to check all the block decision candidates and enables efficient and fast coding unit (CU) decisions.

Compared with machine-learning methods that require manual feature extraction, deep learning can reduce the complexity of CU classification by automatically extracting features using techniques such as neural networks [26,27,28,29], thus achieving a high prediction accuracy, but there are also drawbacks such as the difficulty in constructing datasets and the complex network structure. Among them, Kim et al. [26] proposed a fast CU depth decision algorithm based on a neural network; they constructed a neural network database while considering the image and coding characteristics of CUs to achieve high accuracy testing, and, finally, used the trained neural network to predict the current CU depth, and, when the prediction result was no division, the further division of CUs was stopped. Xu et al. [29] proposed a hybrid network architecture based on deep learning to construct an early termination hierarchical (ETH) prediction model by combining the properties of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. The model adopts a two-branch structure: the ETH-CNN branch analyzes the pixel features of the whole frame and performs deep prediction, while the ETH-LSTM branch processes the prediction distortion features of the coded block and performs deep prediction, and this decision significantly accelerates the CU segmentation process.

However, the above algorithms cannot be directly applied to geometric projection videos because projection videos contain a large number of null pixels, the contents of which are very different from traditional natural videos, and the spatio-temporal correlation is also low, so we need to further combine the characteristics of geometric videos to design efficient CU segmentation algorithms.

2.2. Fast CU Division Algorithm in V-PCC

Currently, there are also some algorithms dedicated to fast CU classification for 2D projected videos, thus reducing the coding complexity of V-PCC. Among them, Xiong et al. [30] proposed an optimization method based on occupancy information, which evaluates the complexity by analyzing the local gradient characteristics of the blocks and combines with the correlation between temporal layers to design an accelerated division strategy guided by the occupancy graph, which significantly improves the coding efficiency. On the other hand, Lin et al. [31] exploited occupancy flags and the spatial homogeneity of pixels to terminate the early segmentation of unoccupied blocks and homogeneous pixel regions, and also introduced image order counting (POC) to optimize the rate-distortion optimization (RDO) process, thus improving the coding speed while ensuring the quality. Although these methods can effectively reduce the coding complexity of V-PCC in the random access (RA) configuration, the current research on fast coding algorithms for the all-in-frame (AI) configuration is still limited. Therefore, how to improve the coding efficiency of V-PCC under the AI configuration is still a direction worth exploring in depth.

Fast algorithms for HEVC [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], which are mainly designed for natural videos, do not take into account the large number of empty pixels and projection discontinuity in geometric videos, and are inefficient when directly applied to V-PCC. Therefore, we propose a dedicated framework for geometric videos that categorizes CUs into three categories (unoccupied/partially occupied/fully occupied) based on the occupancy map, which is a basic framework designed specifically for geometric video characteristics. Early fast algorithms for V-PCC [30,31], which mainly focus on random-access configurations, have limited research on full intra-frame configurations and have a relatively simple strategy that fails to take full advantage of the human visual system characteristics of geometric videos for more effective V-PCC. Therefore, our work focuses on complexity reduction in full intra-frame configurations, and, for the most complex partially occupied CUs, we innovatively design geometric visual perception factors to achieve depth range advance skipping based on visual sensitivity. Generalized approaches are based on machine/deep learning [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]: the models tend to be complex and unsuitable for lightweight, demonstrate low-latency fast decision-making, are not integrated with the semantic information (e.g., occupancy type) of geometric videos, and shows a lack of specificity. Therefore, for full-occupancy CUs, we design minimalist fully-connected networks to achieve fast inference while guaranteeing accuracy, and our LFCN is tightly coupled with the aforementioned CU triple classification framework and is part of a hybrid strategy rather than an isolated complex model.

Combining the above analysis, in Section 3, we propose an algorithm to speed up the CU division of geometric videos in the full intra-frame (AI) configuration for the characteristics of geometric videos, thus reducing the coding complexity of V-PCC.

3. Proposed Methodology

When point cloud video is compressed using the V-PCC standard, the 3D video is first projected into a 2D video sequence, and, during this projection process, a large number of empty pixels, i.e., unoccupied pixels, are created. Among them, the occupancy map is used to indicate whether a pixel is an occupied or unoccupied pixel, which is expressed in binary. Therefore, we can use the occupancy map to classify the CU blocks in the geometric video as unoccupied (all unoccupied pixels in the CU block), partially occupied (both unoccupied and occupied pixels in the CU block), and fully occupied (all occupied pixels in the CU block), and adopt different CU fast division strategies for the different occupancy types of the CU blocks, which can realize the balance between time saving and coding performance. The occupancy type of CU block OCT_CU can be defined as follows:

where , , and indicate the occupancy type of the CU block as unoccupied, partially occupied, and fully occupied, respectively. is the number of pixels in the current CU, denotes the ith pixel in the current CU block, and is the binary value corresponding to the occupancy map: a value of 1 represents that the pixel is an occupied pixel, a value of 0 means that the pixel is an unoccupied pixel, and denotes the binary value corresponding to the ith pixel in the current CU block in the occupancy map.

3.1. Early Termination Segmentation Algorithm for Unoccupied CUs

During the point cloud compression coding process, unoccupied CU blocks do not contribute to the final point cloud reconstruction as they do not contain valid occupied pixels. However, traditional coding methods are not optimized for such unoccupied blocks and still perform the complete recursive division process, leading to unnecessary computational overhead. Therefore, we can quantitatively analyze the impact of unoccupied blocks on coding efficiency, and terminate the division of unoccupied CU blocks in advance, which can significantly reduce the redundant computation and improve the overall coding efficiency.

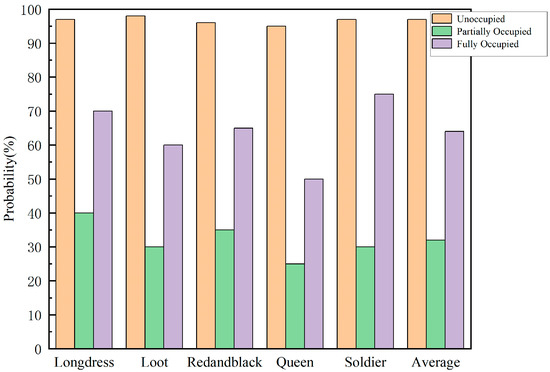

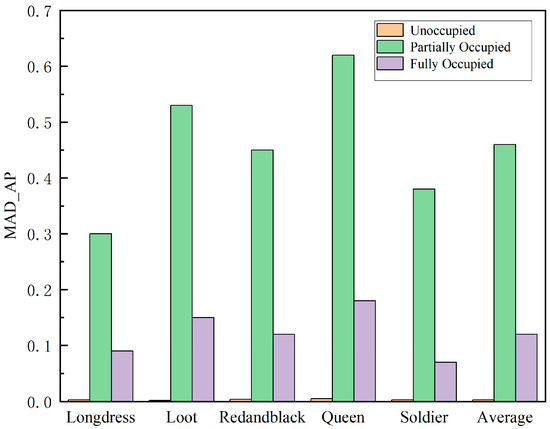

We encode five point cloud sequences, Loot, Longdress, Redandblack, Soldier, and Queen, using V-PCC’s reference software TMC2-V18.0 with bit rates ranging from r1 to r5 under generalized test conditions. Then, we count the undivided probabilities of unoccupied CUs, partially occupied CUs, and fully occupied CUs, as shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that more than 90% of the unoccupied CUs are not further divided, while the probability of not dividing the partially occupied CUs is less than 50%, and the probability of not dividing the fully occupied CUs is slightly more than 50%. Therefore, it is reasonable that unoccupied blocks are not further divided, while partially occupied blocks and fully occupied blocks need to be further divided.

Figure 4.

Undivided probability of each occupancy type in different sequences.

To validate the above analysis, we further introduce the mean absolute deviation of adjacent pixels (MAD_AP) as a quantitative metric, and evaluate the texture complexity characteristics of coding units (CUs) of different occupancy types by calculating this value. MAD_AP is defined as follows:

where represents the pixel value with pixel coordinates ; and , , , , , , , , are the values of neighboring pixels of pixel .

The MAD_AP values for different types of CU blocks are shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the MAD_AP values for unoccupied blocks are negligible, which indicates that unoccupied CUs have a very low complexity and do not need to be further divided, while, for partially occupied blocks and fully occupied blocks, the corresponding MAD_AP values are relatively high, indicating that partially occupied CUs and fully occupied CUs need to be further divided. Therefore, we can terminate the division of unoccupied CUs early.

Figure 5.

MAD_AP values for each occupancy type in different sequences.

Based on the above analysis results, we propose a division termination strategy for unoccupied CUs. The algorithm first detects the occupancy status of the CU block, and immediately terminates the division process if it is determined to be an unoccupied CU, thus significantly improving the coding efficiency.

3.2. Early Skip Segmentation Algorithm for Partially Occupied CUs Based on Visual Saliency

Through the analysis in Section 3.1, it can be seen that the partially occupied CU blocks have high complexity, and further CU division is needed to improve the coding quality. Upon observation, it can be found that most of the partially occupied CUs are distributed in the edge region, but a few are distributed in the non-edge region, which contain both occupied and unoccupied pixels, and usually have locally flat and locally complex texture features, with different degrees of spatial depth variation within the CU blocks. Studies have shown that the human visual system exhibits a high sensitivity to gradient changes in spatial depth.

Based on this visual property, we propose a fast CU segmentation algorithm based on spatial saliency. In spatial saliency detection, we determine the edge regions with dramatic spatial depth changes as high saliency regions, and categorize the non-edge regions with uniform spatial depth changes as low saliency regions. Through spatial saliency extraction, we designed the geometric visual perception factor, GVP, classified partially occupied CU blocks into visually sensitive CUs (VS Poc_CU), moderately visually sensitive CUs (MVS Poc_CU), and non-visually sensitive CUs (NVS Poc_CU) by the visual perception factor, and obtained the optimal depth ranges of partially occupied CU blocks of different kinds of sensitivities through statistical analysis, and, finally, obtained the optimal depth ranges of partially occupied CU blocks of different kinds of sensitivities through statistical analysis. The optimal depth range of partially occupied CU blocks is obtained through statistical analysis, and, finally, according to the obtained optimal CU depth range, the depths outside the optimal depth range are skipped in advance, while the division depths within the optimal depth range are calculated through the original RD cost calculation to arrive at the final optimal division depths; thus, the redundant division process of partially occupied CU blocks is skipped, and an optimized balance between coding efficiency and image quality is achieved under the premise of maintaining the quality of visual perception by the human eye, which significantly improves the overall coding speed.

3.2.1. Spatial Significance Extraction Based on Occupancy Graph Improvement

The main purpose of saliency extraction is to identify the region of an image or video that attracts the most visual attention. Traditional saliency extraction methods will mainly focus on the key points that the user notices at first glance, but, in practice, the context of the key points and the key points are inextricably linked, so the salient region should not only contain the main key points, but also the contextual part of the background region.

Context-based salient extraction methods follow three core principles: local low-level features, such as contrast and color, etc., are used to identify surrounding pixels that are significantly different, and a block of pixels is considered as salient when the pixel value is significantly different from other pixels; frequent usual features are suppressed and unusual features are highlighted from a global perspective; and, based on the laws of visual organization, salient regions should be clustered and distributed rather than isolated Based on the law of visual organization, salient regions should be clustered rather than isolated and dispersed. Based on these principles, it can be seen that saliency extraction needs to be based on the pixel blocks around the pixel rather than individual pixels, and also consider the spatial distribution relationship; i.e., a pixel block will be more salient when it is significantly different from the surrounding pixel blocks and there are other pixel blocks similar to the pixel block in the vicinity, and the saliency of this pixel block will be weakened when the pixel blocks that are similar are far away from the pixel block.

Based on the above analysis, we design an effective extraction method for spatial saliency by suppressing regions with relatively flat spatial locations and highlighting regions with high spatial contrast from both global and local perspectives, combined with contextual parts. According to the three core principles of saliency extraction, for the local image block centered at pixel with radius r, the degree of saliency is determined by calculating its visual feature difference with other image blocks , and the Euclidean distance of the normalized luminance component, , is used to represent the visual feature luminance difference between image blocks and . This luminance difference value directly reflects the significance strength; i.e., the larger is, the stronger the significance of the center pixel is indicated. Based on the law of visual perception, i.e., similar image blocks with spatial proximity will enhance the saliency, while similar image blocks with farther positional distance will weaken the saliency, the normalized Euclidean distance is introduced to measure the spatial positional distance between image blocks and . Therefore, the dissimilarity between image blocks and is expressed as follows:

where is the control coefficient, where it takes the value of 3. As seen in the equation, the variability between a pair of image blocks is proportional to the difference in luminance components and inversely proportional to the spatial location distance.

In significance extraction, in order to assess the difference of an image block , it is only necessary to examine the degree of difference of its most similar N neighboring blocks in order to effectively assess its significance. The basis of this design is that, if even the most similar N blocks are significantly different from , it can be deduced that is significantly different from the overall image content. This is achieved by first filtering the N most similar image blocks by the difference measure for each image block , and, when the difference value between these most similar blocks and is large, it can be determined that the center pixel of this block has a high significance. This approach maintains the accuracy of the saliency assessment and significantly reduces the computational complexity. From this, it can be introduced that the significance value of pixel on the r scale is as follows:

where is a natural exponential function that maps the output to (0,1]: when the average difference is larger, is closer to 1—i.e., the pixel is more significant; and, when the average difference is larger, is closer to 0—i.e., the pixel is less significant. According to the experimental statistics, the significance extraction is better when N is taken as 256. Here, r = 4 is chosen as the basic unit of image processing.

However, the above saliency extraction methods require complex computation for each pixel with a high time complexity. Therefore, we propose a hierarchical strategy: first, the original image is down-sampled by a factor of 4 to reduce the computational scale, and then up-sampled to restore the original resolution after completing the significance detection in the low-resolution space, which ensures the accuracy of the results and significantly improves the efficiency at the same time. In addition, the geometric image is composed of multi-projection surface patches with significant depth differences, and the direct significance extraction of the geometric image may suffer from accuracy degradation. Therefore, we innovatively introduce the occupancy map-guided chunking mechanism, i.e., we utilize the occupancy map to independently perform the significance extraction for each patch, so that the significance extraction result of each patch is only affected by the occupied pixels and will not be affected by the other patches and unoccupied pixels, which makes the saliency extraction results more consistent with the perception of the human eye, and achieves a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

3.2.2. Design of Geometric Visual Perception Factor, GVP

Since different CUs have different visual importance, we designed a Geometry Visual Perception factor (GVP) to measure the visual importance of each partially occupied CU. After introducing the occupancy map, the saliency mean value of the occupied pixels in each partially occupied CU is used as the saliency value V of the current partially occupied CU, which is calculated as follows:

where is the significance value of the xth partially occupied CU. The significance value of unoccupied pixels is 0 since no significance extraction is performed for unoccupied pixels, and N is the number of occupied pixels in the current partially occupied CU.

Next, we take the saliency mean of all partially occupied blocks in the current frame as the average visual importance value of the current frame, which is defined as follows:

where is the number of partially occupied blocks in the current frame.

Finally, the geometric visual perception factor, GVP, for each partially occupied block in the current frame is defined as follows:

where is the intensity factor, and a larger value of indicates a larger range of values for . The optimal should lie in the interval that makes most sensitive to changes in /, usually 1 < < 3. The role of is to regulate the sensitivity of the to changes in /. When = , is constant at 1 regardless of the value of . We analyzed the distribution range of / and tested different values of = 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and so on. When = 2, the best balance between “avoiding to categorize too many CUs into fuzzy moderately sensitive categories” and “ensuring effective differentiation of visual sensitivity” is achieved. = 2 produces the most optimal nonlinear mapping of the over the typical range of / variations. Therefore, in this paper, is set to 2.

When is less than 1, it means that the xth part of the occupied CU belongs to a non-significant region—i.e., the human eye is not sensitive to this region; while, when is greater than 1, it means that the xth part of the occupied CU belongs to a significant region, and the human eye is sensitive to this region. This significance-based analysis can effectively determine the visual importance of different regions in the point cloud video, which facilitates the optimal design of the subsequent coding process.

3.2.3. Early Skip CU Division Algorithm Based on Spatial Significance

- (1)

- Correlation analysis of geometric visual perception factor, GVP, size and partially occupied CU block division:

Regions with larger GVPs represent visually perceptually sensitive areas and usually contain more information. In the process of CU division for video coding, in order to improve the prediction efficiency, such regions can be divided into smaller CUs—i.e., the division depth is larger, while, for non-visually sensitive regions, they are always divided into large CUs—i.e., the division depth is small. Therefore, there is a positive correlation between GVP and CU depth; i.e., the higher the GVP, the greater the coding unit division depth.

Since the degree of HVS sensitivity has a positive correlation with the division depth of CUs, we use the GVP size to categorize all partially occupied CUs and obtain the optimal depth division range by statistical methods. Based on the optimal depth range, the encoder can skip the division depths that exceed the optimal depth range, thus saving coding time.

- (2)

- Partial occupancy CU classification based on GVP size:

Based on the GVP size, the partially occupied CUs in a video frame are classified into three categories: visually sensitive coding blocks (VS Poc_CU), moderately visually sensitive coding blocks (MVS Poc_CU), and non-visually sensitive coding blocks (NVS Poc_CU). The classifier is shown in the following equation:

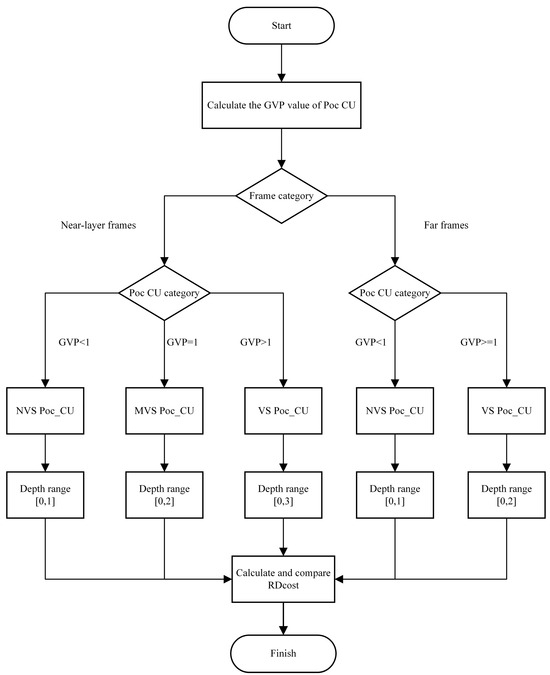

V-PCC has a unique dual frame rate structure; i.e., a far-layer frame and a near-layer frame will be generated in one dynamic point cloud frame. The statistics of the CU division pattern probability between the far-layer frame and the near-layer frame reveals that there is a significant difference in the coding unit division pattern probability between the near-layer frame and the far-layer frame under the same Quantization Parameter (QP). Therefore, we classify the partially occupied CUs of near-layer frames and far-layer frames separately. The optimal depth range is obtained by counting the different categories of CU division depths for near-layer frames and far-layer frames separately.

- (3)

- Optimal depth range for partially occupied CUs:

The partially occupied CUs of geometric videos are categorized using the above formulae, and the depth ranges of different kinds of partially occupied CU divisions are statistically analyzed to obtain the optimal depth ranges of partially occupied CUs of geometric videos.

Table 1 represents the probability of dividing the partial CUs of the three visual sensitivity levels at each depth under the near-layer frame. By analyzing Table 1, it can be concluded that the probability of selecting depths 0 and 1 for NVS Poc_CU is 98.21% on average, and all other depth levels are less than 2%, so the depth of NVS Poc_CU tends to select depths 0 and 1; the average probability of selecting depths 0, 1, and 2 for MVS Poc_CU is 96.68%, and the average probability of selecting depth 3 is only 3.32%, and, therefore, MVS Poc_CU tends to choose depths 0, 1, and 2; and, although the average probability of VS Poc_CU choosing depth 0 is only 2.15%, its depths are chosen to be 0, 1, 2, and 3 due to the large influence of geometric video near-layer frames on the quality of the point cloud reconstruction and the significant influence of VS Poc_CU on the subjective perception quality.

Table 1.

Division probabilities of the three partially occupied CUs at various depths under the near-layer frame.

Table 2 represents the depth distribution of partially occupied CUs for the three types of geometric video far-layer frames. By analyzing Table 2, it can be concluded that the average probability of NVS Poc_CU selecting depth 2 and depth 3 is only 1.66% and 1.71%, respectively, and, thus, tends to select depths 0 and 1; the average probability of MVS Poc_CU selecting depths 0 and 1 is 96.30% while the average probability of selecting other depths is less than 3%, and, thus, MVS Poc_CU also tends to select depths 0 and 1; and the average probability of VS Poc_CU selecting depths 0, 1, and 2 is 97.70%, while the average probability of selecting depth 3 is only 2.30%, so the depths tend to select 0, 1, and 2.

Table 2.

Segmentation probabilities of the three partially occupied CUs at each depth under the far frame.

Since the optimal delineation depths of the NVS Poc_CU and the MVS Poc_CU in the distant frames are the same and the data of the distant frames are the supplements of the data of the nearer frames, the delineation is relatively simple and has less impact on the reconstruction quality; the geometric video far layer partially occupied CUs are, therefore, divided into two categories, NVS Poc_CU and VS Poc_CU. Based on the above analysis, the optimal depth ranges of partially occupied CUs in geometric videos with different degrees of visual sensitivity under near-layer frames and far-layer frames are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Optimal depth ranges of three partially occupied CUs under near-layer frames.

Table 4.

Optimal depth ranges of three partially occupied CUs under far-layer frames.

3.2.4. Overall Flow of Partially Occupied CU Early Skip Segmentation Algorithm Based on Spatial Significance

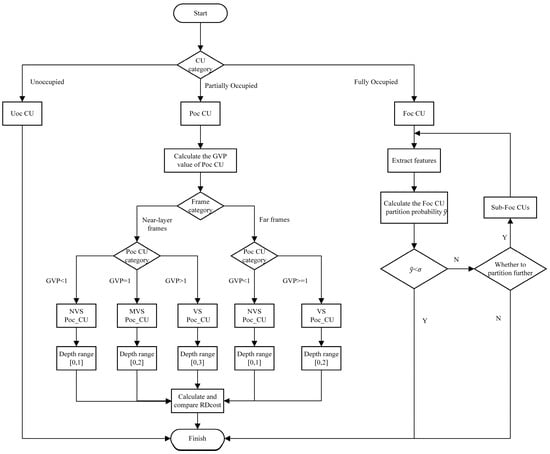

The algorithm designs the geometric visual perception factor, GVP, by extracting the value of significance, and then uses the GVP to classify the partially occupied CUs, and obtains the optimal depth ranges of different kinds of partially occupied CUs through statistical analysis, realizing the partially occupied CUs to skip the division in advance, so as to save the coding time, and to ensure that the coded geometric video has a high quality of clarity under the human eye. The flow of the algorithm is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of fast segmentation algorithm for partially occupied CUs.

3.3. Segmentation Decision for Fully Occupied CUs Based on Lightweight Fully Connected Networks

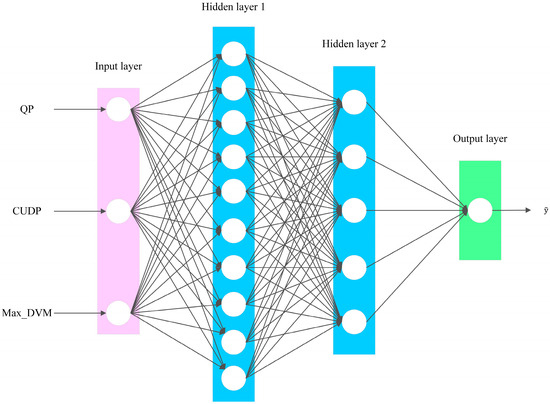

From the analysis in Section 3.1, it can be seen that the complexity of the fully occupied CU block is relatively high, which requires further CU division. However, the spatial depth of fully occupied CU blocks varies more uniformly, and it is impossible to judge the sensitivity of the human eye to CUs through spatial saliency detection as a means of realizing the early skip division of CUs. Therefore, we can design a neural network to accurately predict the optimal coding unit division of fully occupied CU blocks. First, we extract the effective features QP, CUDP, and Max_DVM of the fully occupied CU block in order to improve the prediction accuracy of the neural network, in which Max_DVM is obtained by the distortion transformation of the fully occupied CU. Then, we put the above extracted features into our designed Lightweight Fully Connected Network (LFCN) as the input of this neural network, which can accurately predict whether the fully occupied CU is divided or not by training.

3.3.1. Feature Extraction

- (1)

- QP and coding unit depth, CUDP, extraction:

QP: The size of CU divisions varies with different QPs; usually, larger QPs divide into larger CUs and smaller QPs divide into smaller CUs. Therefore, QPs are needed as a valid feature related to CU divisions.

CUDP: Since different depths of CUs correspond to different sizes of CUs, the number of pixels contained in them also varies significantly, which, in turn, leads to different texture complexities. Therefore, the coding unit depth, CUDP, is also a key feature for CU segmentation.

- (2)

- Extraction of Maximum Distortion Variance, Max_DVM:

CU division is closely related to the RD cost of that CU. In general, the higher the RD cost, the higher the probability that the CU will be classified, and vice versa. The RD cost is calculated as follows:

where denotes the distortion of the currently encoded CU, is the Lagrange multiplier, and is the bits required for encoding. However, the magnitude of the RD cost varies greatly with the size of the CU and cannot be used as a valid characterization of the CU. According to the RD calculation formula, it is known that CU distortion and RD cost are strongly correlated; therefore, we have selected distortion as a valid feature for CU division. The distortion matrix of a CU block with width w and height h is defined as follows:

where and denote the real pixel value and the coded predicted pixel value of the CU block with width w and height h, respectively. However, under a different QP, the value of will change, and there is a positive correlation between them. In order to normalize the value of so that it is in the interval [0,1], which is easy to input into the neural network, we transform into the following:

where is the transformation coefficient, which is compromised based on the QP configurations in the geometry video and is set to 24. The QP configurations are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Different QP values corresponding to different bit rates in geometric video.

Since the CU contains more distortion values, in order to more accurately characterize the overall distortion properties of the CU of the coding unit, we adopt the variance as the distortion metric. Specifically, the overall distortion of the CU is defined as follows:

where and represent the horizontal and vertical coordinate positions of the pixel points within the block of coding units (CUs) of width w and height h, respectively. In order to fully evaluate the distortion characteristics, we need to compute not only the global distortion but also the local distortion of the CUs, so we use a quadtree partitioning strategy to uniformly decompose the distortion matrix of the coding unit (CU) into four submatrices of the same size, namely, , where is equal to , and these four submatrices are used as the local distortion of CU. Finally, we take the maximum of the overall distortion and the four local distortions as the effective feature Max_DVM of the CU, which is used to guide the division of the CU. Max_DVM is defined as follows:

- (3)

- Correlation between QP, CUDP, Max_DVM, and other features:

In order to characterize the coding unit CU more comprehensively, we introduce two additional key features: the coding block flag (CBF) is used to detect the presence of non-zero transform coefficients in the current CU, and, thus, to judge the necessity of its coding; meanwhile, the occupancy mode (OCM) is used to accurately represent the distribution of pixels within the CU, and to judge the occupancy type of this CU. Since we are using a lightweight fully connected network, we need to keep fewer valid features, and features with high correlation can be represented to each other, so we can analyze the correlation between different features so that we can keep the weakly correlated features and one of the strongly correlated features, as well to reduce the features. We determine the correlation between features by analyzing the Spearman’s coefficient of equal variance between features. Through the analysis, we can see that there is a weak correlation between Max_DVM, QP, and CUDP, which cannot represent each other, and a strong correlation between Max_DVM, CBF, and OCM, which can represent each other. Therefore, we further calculate the correlation between Max_DVM, CBF, and OCM with each other, and find that Max_DVM presents a strong correlation with CBF and OCM at the same time. In summary, we select features QP, CUDP, and Max_DVM as features to be input into the lightweight network for training.

3.3.2. Neural Network Structure

This lightweight fully connected network adopts a four-layer structure: the input layer is responsible for receiving preprocessed feature data; of the two subsequent hidden layers, the first hidden layer (HD1) contains 10 neurons and uses ReLU as the activation function, while the second hidden layer (HD2) is set up with 5 nodes and chooses Sigmoid as the activation function; and the final output layer uses a single neuron and uses Sigmoid as the activation function. The output value of the LFCN indicates the fully occupied CU. The probability of further division ranges from 0 to 1. The LFCN schematic is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Fully connected lightweight network diagram.

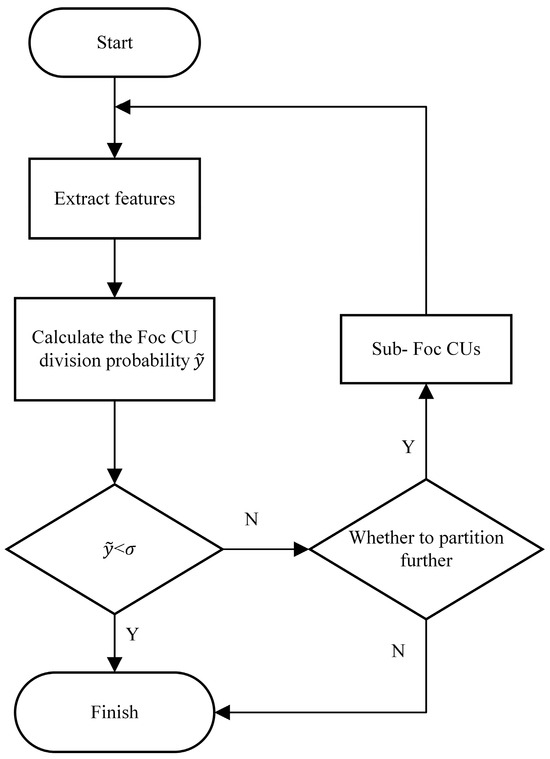

3.3.3. Fast Segmentation Decision for Fully Occupied CUs

The flow of the fully occupied CU fast segmentation algorithm based on lightweight fully connected networks is shown in Figure 8. For a fully occupied CU block, the encoder first extracts its effective features. Then, these features are fed into the LFCN network to obtain an output value . represents the probability of further segmentation of this fully occupied CU. However, in different scenarios, the requirements for the delineation accuracy are different, so we set a threshold to facilitate flexible decision making based on different scenario requirements for applying different scenarios. Specifically, when is less than , the division is ended; when is greater than or equal to , further division is judged according to the original method. For the I-frame and P-frame of the geometric video, we set the corresponding thresholds and , respectively. Through a large number of experimental analyses, in order to realize the fast CU segmentation decision, we set the thresholds and to be 0.3 and 0.9, respectively. The thresholds we set are able to achieve the balance between the coding time saving and the coding quality. These two thresholds were determined on the validation set after the model training was completed by weighing the coding time savings against the loss of BD-Rate performance. We tested the variation in coding time savings with respect to the BD-Rate growth for different values of . For for I-frames, we found that, at < 0.3, time savings grow slowly but BD-Rate starts to deteriorate significantly, and, therefore, we chose = 0.3. For for P-frames, we found that a more conservative threshold (higher ) is needed to protect the quality of the inter-frame prediction, and that = 0.9 ensures sizable time savings while keeping the BD-Rate loss at a very low level. On this basis, the thresholds can be adjusted appropriately when facing different requirements. For the case where the coding quality requirement is relatively high but the time saving requirement is relatively low, the thresholds can be lowered appropriately; conversely, the thresholds can be raised appropriately.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of fast segmentation algorithm with fully occupied CUs.

4. Overall Algorithmic Flow

We categorize CU blocks into unoccupied blocks, partially occupied blocks, and fully occupied blocks based on the occupancy graph. According to different CU blocks, we adopt different segmentation strategies, respectively. For unoccupied blocks, we directly terminate their segmentation; for partially occupied blocks, we classify them into visually sensitive partially occupied CUs, moderately visually sensitive partially occupied CUs, and non-visually sensitive partially occupied CUs based on the degree of visual sensitivity by visual saliency extraction, and statistically calculate the optimal segmentation depth ranges of the partially occupied CU blocks with different sensitivities, so as to skip the segmentation beyond the optimal depth based on the optimal segmentation depth range; and, for fully occupied CUs, we extract the effective features of fully occupied CU blocks and put them into the trained neural network for output, and compare the output value with the threshold value, so as to realize the fast division decision of fully occupied CUs. The overall algorithm flow is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Overall flowchart of the fast segmentation algorithm for geometric video CUs.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Experimental Configuration and Evaluation Indicators

Our proposed method is implemented under the full intra-frame (AI) configuration of the V-PCC Common Test Conditions (CTC) based on the TMC2-V18.0 reference software platform [32], in which the HEVC encoder of version HM16.20-SCM8.8 is used [33]. To validate the effectiveness of the algorithm, five typical dynamic point cloud sequences, Longdress, Loot, Redandblack, Queen, and Soldier [34], were selected as the test dataset. The QPs and corresponding bit rates used in the experiments are shown in Table 5 above. For the evaluation of the algorithms, we evaluate the coding performance of geometric videos using the BD-Rate metrics of point-to-point error (D1) and point-to-face error (D2); we evaluate the coding performance of attribute videos using the BD-Rate metrics of the Luma, Cb, and Cr components; and we use the coding time-saving to evaluate the speedup effect of the algorithms. The time saving is defined as follows:

where is the coding time savings, is the coding time required by the proposed algorithm, and denotes the coding time required by the original approach.

5.2. Neural Network Model Training

We use eight frames from the dynamic point cloud video basketball_player, i.e., frames 555 to 562, as the dataset for our experiments; each sample in the dataset contains the valid features QP, CUDP, Max_DVM, and labels used to indicate whether or not the CU is further segmented, with a label value of 1 indicating that the CU needs to be further segmented, and a value of 0 indicating that the CU does not require further segmentation. During the training process, we mainly use the accuracy of the model to evaluate how well the model is trained. The mean square error (MSE) can supervise the network structure during the network training process, thus making the neural network more accurate and efficient after training. To eliminate ambiguity, we define the loss function as follows:

where is the full set of parameters in this network, containing the weights and biases of each neuron; is the input to the neural network; and are the predicted and true values, respectively; and is the number of training samples.

5.3. Overall Algorithm Performance

Table 6 details the time savings of the proposed method compared to the original method, where ∆T-Uoc CU, ∆T-Poc CU, and ∆T-Foc CU denote the time savings for unoccupied CUs, partially occupied CUs, and fully occupied CUs in the geometric video, respectively, ∆T-Geom denotes the time savings for the geometric video, and ∆T-Total denotes the total coding time savings for the V-PCC. For unoccupied, partially occupied, and fully occupied blocks in geometric video, the corresponding time savings are 31.31%, 15.04%, and 12.37%, respectively, which indicates that our proposed algorithm achieves the corresponding coding time savings for different occupied types of CU blocks. The time savings for geometric video coding range from 53.87% to 63.01%, which are all more than 50%, with an average coding time savings of 58.71%. Combined with the coding time of the attribute video, the overall coding time of V-PCC ranges from 50.12% to 57.26%, with an average coding time saving of 53.96%, which indicates that the algorithm can well realize the fast division of CUs and reduce the coding time complexity. In this case, the video sequence Soldier saves less time compared to other sequences due to the fact that it has fewer unoccupied blocks, more partially occupied blocks, and a higher depth complexity.

Table 6.

Time savings for different CUs in geometric videos.

In addition, the experimental results show that the method in this paper can effectively improve the coding efficiency under different quantization parameter (QP) conditions. As shown in Table 7, the algorithm as a whole can achieve an average coding time saving of 53.96%. It is particularly noteworthy that the time saving effect is more significant as the QP value increases, which is attributed to the fact that the coding units (CUs) at high QP values are more inclined to maintain a larger size or are not divided, thus significantly reducing the coding time consumed.

Table 7.

Time savings of different sequences at different QPs.

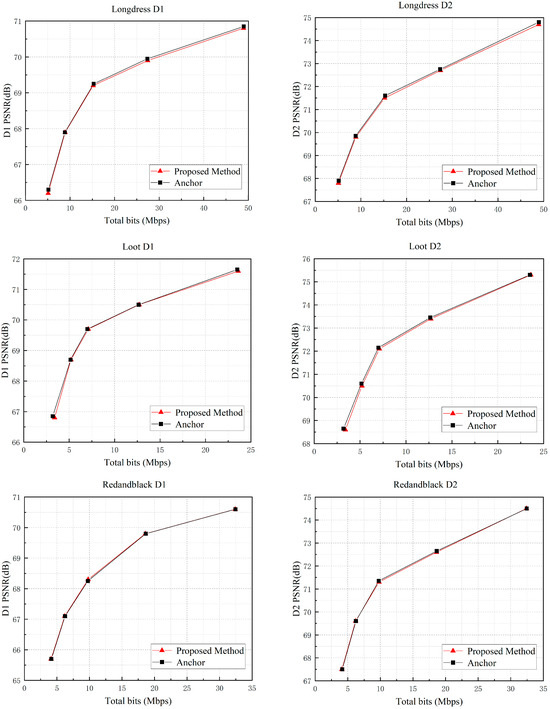

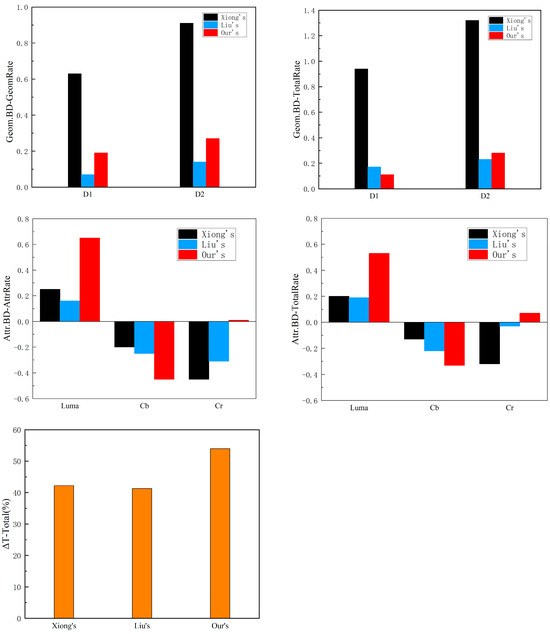

We have compared the proposed algorithm with the V-PCC benchmark method in our experiments and the results are shown in Table 8 and Figure 10. Due to the correlation effect of geometric video coding on attribute video coding, the proposed algorithm also brings a slight performance improvement in attribute video coding. The experimental data show that the BD rate variations in the D1, D2, Luma, Cb, and Cr components are 0.19%, 0.27%, 0.65%, −0.45%, and 0.01% when only geometric and attribute video coding bit rates are considered, while the BD rate variations of the corresponding components are 0.11%, 0.28%, 0.53%, −0.33%, and 0.07%, respectively, when considering the total bit rate. These results show that the present algorithm significantly improves the coding efficiency with only a negligible impact on the coding quality, achieving a good balance between coding speed and quality.

Table 8.

Comparison of performance and time savings between the proposed algorithm and the original approach.

Figure 10.

RD curve of the proposed algorithm compared to the original method.

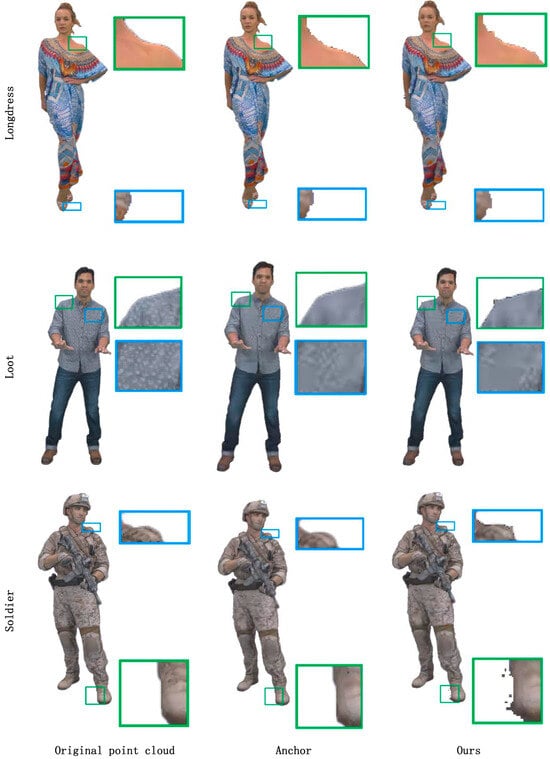

In order to emphasize the visual quality effects of the method, we select representative frames from the test sequence and show the following versions of the reconstructed point cloud side by side: the original point cloud, the reconstructed point cloud using the original V-PCC method, and the reconstructed point cloud using our proposed fast method. To clearly demonstrate subtle differences, we will focus on texturally complex regions (e.g., clothing folds, and hair) and geometrically edged regions. As shown in Figure 11, it can be seen that the visual quality of our proposed method is only slightly degraded.

Figure 11.

Visual quality comparison of original point cloud, original V-PCC, and our methods.

5.4. Comparison with Other Advanced Methods

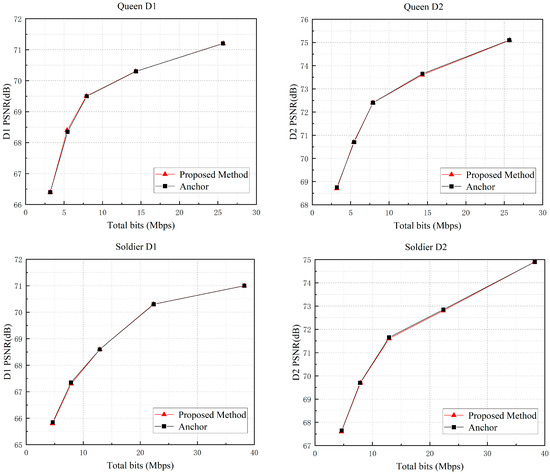

Under the same experimental conditions, we compare the proposed method with the state-of-the-art methods of Xiong et al. [30] and Liu et al. [35]. The proposed method of Xiong et al. accelerates the mode and partitioning decision of geometric and attribute videos by utilizing a threshold. Liu et al. choose LightGBM to generate the training model and invoke Bayesian optimization to determine the model’s optimal hyperparameters. Thus, the fast decision of geometric video coding units is realized. The comparison results are shown in Table 9 and Figure 12. It can be seen that, although Xiong et al.’s method can save 43.3% more time, the BD rate of each component is higher and the quality loss is relatively larger. Compared with Xiong’s method, our method can save 53.96% more time while guaranteeing a lower BD rate. Liu et al.’s method saves relatively little coding time, only 40.13%, although the BD rate is very low and the coding loss is almost negligible. Compared to Liu’s method, our method saves more time, 13.83% more than Liu’s time savings. The results show that our method outperforms the other two algorithms in both time savings and is better in terms of coding performance, and can achieve a relative balance between time savings and coding quality.

Table 9.

Comparison of performance and time savings between the proposed algorithm and other state-of-the-art methods.

Figure 12.

Visualization of the comparison results between the proposed algorithm and other state-of-the-art methods in the same environment.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a fast division algorithm for geometric videos based on the time-consuming problem of dividing the coding units of geometric videos in V-PCC coding. Specifically, we categorize the coding units of geometric videos into different occupancy types of CUs based on the occupancy graph, and adopt different segmentation strategies for each of them. For unoccupied CUs, we terminate the segmentation directly; for partially occupied CUs, we further classify them according to the visual sensitivity of the human eye, and statistically analyze the optimal segmentation depths of partially occupied CUs with different sensitivity levels, so as to skip the segmentation depths outside the optimal segmentation depths; and, for fully occupied CUs, we design and train a neural network to accurately predict whether to segment them further or not. The experimental results show that the method can achieve an average 58.71% coding time saving for geometric videos, and the overall coding time saving for V-PCC reaches 53.96% on average, while the average BD rates of D1 and D2 components are only slightly increased by 0.11% and 0.28%, respectively, at the total bit rate, which ensures a small coding quality loss while substantially reducing the time complexity. It is worth noting that our approach mainly reduces the coding complexity of V-PCC by speeding up the coding of geometric videos, and, in the future, we will further investigate fast coding algorithms for attribute videos as a way to reduce the coding complexity of V-PCC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and T.Z.; methodology, N.L.; software, Q.Z.; validation, T.Z., N.L. and J.Z.; formal analysis, N.L.; investigation, N.L.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Z. and Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, N.L.; visualization, Q.Z.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, Q.Z.; funding acquisition, N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Nos. 61771432 and 61302118, the Key Projects Natural Science Foundation of Henan 232300421150, the Zhongyuan Science and Technology Innovation Leadership Program 244200510026, and the Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province 232102211014, 242102211020, 242102210220, and 232102210069.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to our esteemed colleagues at the university for their unwavering support and invaluable insights throughout the research process. We also express our sincere gratitude to the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their diligent review and constructive suggestions, which greatly contributed to the enhancement of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cao, C.; Preda, M.; Zakharchenko, V.; Jang, E.S.; Zaharia, T. Compression of Sparse and Dense Dynamic Point Clouds-Methods and Standards. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1537–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, R.; Freitas, P.G.; Farias, M.C. Point Cloud Quality Assessment Based on Geometry-Aware Texture Descriptors. Comput. Graph. 2022, 103, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Pan, W.; Lu, R.X. Random Screening-Based Feature Aggregation for Point Cloud Denoising. Comput. Graph. 2023, 116, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Q.; Hou, J.; Liu, J. A Comprehensive Study and Comparison of Core Technologies for MPEG 3-D Point Cloud Compression. IEEE Trans. Broadcast 2019, 66, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 23090-9:2023; Information Technology—Coded Representation of Immersive Media—Part 9: Geometry-Based Point Cloud Compression. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO/IEC 23090-5:2023; Information Technology—Coded Representation of Immersive Media—Part 5: Visual Volumetric Video-Based Coding (V3C) and Video-Based Point Cloud Compression (V-PCC). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Cao, C.; Preda, M.; Zaharia, T. 3D Point Cloud Compression: A Survey. ACM Trans. Graph. 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Gao, W.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Jia, W.; Liu, S. Video-Based Point Cloud Compression Artifact Removal. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 24, 2866–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Preda, M.; Baroncini, V.; Budagavi, M.; Cesar, P.; Chou, P.A.; Cohen, R.A.; Krivokuća, M.; Lasserre, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Emerging MPEG Standards for Point Cloud Compression. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2018, 9, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziosi, D.; Nakagami, O.; Kuma, S.; Zaghetto, A.; Suzuki, T.; Tabatabai, A. An Overview of Ongoing Point Cloud Compression Standardization Activities: Video-Based (V-PCC) and Geometry-Based (G-PCC). APSIPA Trans. Signal Inf. Process 2020, 9, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.S.; Preda, M.; Mammou, K.; Tourapis, A.M.; Kim, J.; Graziosi, D.B.; Rhyu, S.; Budagavi, M. Video-Based Point-Cloud-Compression Standard in MPEG: From Evidence Collection to Committee Draft [Standards in a Nutshell]. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2019, 36, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, H. Occupancy-Map-Based Rate Distortion Optimization and Partition for Video-Based Point Cloud Compression. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 31, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, G.; Yu, M. Depth-Perception Based Geometry Compression Method of Dynamic Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Video and Image Processing (ICVIP 2021), Hayward, CA, USA, 22–25 December 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Gao, W.; Li, G.; Li, Z. Rate-Distortion-Guided Learning Approach with Cross-Projection Information for V-PCC Fast CU Decision. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 3085–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Yuan, H.; Li, G.; Li, Z. Low Complexity Coding Unit Decision for Video-Based Point Cloud Compression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ma, H.; Chen, Y. Gradient Based Fast Mode Decision Algorithm for Intra Prediction in HEVC. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Communications and Networks (CECNet, 2012), Yichang, China, 21–23 April 2012; pp. 1836–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Lee, B.; Kim, M. A Novel Fast CU Encoding Scheme Based on Spatiotemporal Encoding Parameters for HEVC Inter Coding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2015, 25, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.T.; Chen, P.Y.; Lin, H.C. A Spatiotemporal Content-Based CU Size Decision Algorithm for HEVC. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2020, 66, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X. Fast CU Size Decision Based on Texture Complexity for HEVC Intra Coding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechatronic Sciences, Shengyang, China, 20–22 December 2013; pp. 1096–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, Z.; Rogeany, K.; Cen, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, W. A Fast CU Partition Method Based on CU Depth Spatial Correlation and RD Cost Characteristics for HEVC Intra Coding. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2019, 75, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, L. Effective HEVC Intra Coding Unit Size Decision Based on Online Progressive Bayesian Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME, 2016), Seattle, WA, USA, 11–15 July 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, F.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y. Fast Mode and Partition Decision Using Machine Learning for Intra-Frame Coding in HEVC Screen Content Coding Extension. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top Circuits Syst. 2016, 6, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Li, H.; Meng, F.; Zhu, S.; Wu, Q.; Zeng, B. MRF-Based Fast HEVC Inter CU Decision with the Variance of Absolute Differences. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2014, 16, 2141–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kwong, S.; Wang, X.; Yuan, H.; Pan, Z.; Xu, L. Machine Learning-Based Coding Unit Depth Decisions for Flexible Complexity Allocation in High Efficiency Video Coding. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 2225–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werda, I.; Maraoui, A.; Belghith, F. HEVC Coding Unit Decision Based on Machine Learning. Signal Image Video Process. 2022, 16, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Ro, W.W. Fast CU Depth Decision for HEVC Using Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, M.; Tang, R.; Chen, Y.; Xing, Q. DeepQTMT: A Deep Learning Approach for Fast QTMT-Based CU Partition of Intra-Mode VVC. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 5377–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kang, J.W. Fast Multi-Type Tree Partitioning for Versatile Video Coding Using a Lightweight Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 23, 4388–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Yang, R.; Guan, Z. Reducing Complexity of HEVC: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 5044–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Lin, W. Occupancy Map Guided Fast Video-Based Dynamic Point Cloud Coding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-L.; Bu, H.-B.; Chen, Y.-C.; Yang, J.-R.; Liang, C.-F.; Jiang, K.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Yue, X.-F. Efficient Quadtree Search for HEVC Coding Units for V-PCC. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 139109–139121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Point Cloud Compression Category 2 Reference Software. Available online: https://github.com/MPEGG (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- High Efficiency Video Coding Test Model, HM-16.20+SCM-8.8. Available online: https://hevc.hhi.fraunhofer.de/svn/svn_HEVCSoftware/tags/HM-16.20+SCM-8.8 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Eon, E.; Harrison, B.; Myers, T.; Chou, P. 8I Voxelized Full Bodies, Version 2–A Voxelized Point Cloud Dataset. In Proceedings of the ISO/IEC JTC1/SC29 Joint WG11/WG1 (MPEG/JPEG) Input Document M40059, Macau, China, 16–20 October 2017; Volume 74006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; He, B.; Huang, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M. Fast CU Decision Algorithm Based on LightGBM for Geometry Video in V-PCC. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering (EITCE 2023), Xiamen, China, 20–22 October 2013; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).