Abstract

In low-light environments, light field (LF) images are often affected by various degradation factors, which impair the performance of subsequent visual tasks such as depth estimation. To address these challenges, although numerous light-field low-light enhancement methods have been proposed, they generally overlook the importance of frequency-domain information in modeling light field features, thereby limiting their noise suppression capabilities. Moreover, these enhancement methods mainly rely on pixel- or semantic-level cues without explicitly incorporating disparity information for structural modeling, thereby overlooking the stereoscopic spatial structure of light field images and limiting enhancement performance across different depth levels. To address these issues, we propose a light field low-light enhancement method named DDPNet. The method integrates a depth-guided mechanism to jointly restore light field images in both the spatial and frequency domains, employing a multi-stage progressive strategy to achieve synergistic improvements in illumination and depth. Specifically, we introduce a Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) module, which incorporates spatial-frequency analysis to efficiently extract both global and local light field features. In addition, we propose a Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) module, which utilizes depth maps to guide the enhancement process, effectively restoring edge structures and luminance information. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that DDPNet significantly outperforms existing methods.

1. Introduction

Light Field Imaging records the direction and intensity of each light ray in a scene, thereby forming 4D light-field data. This capability provides a solid foundation for computational photography applications such as refocusing [1], depth estimation [2], and 3D reconstruction [3]. However, under low-light conditions, image noise is significantly amplified and the dynamic range is severely compressed, leading to the loss of fine structural details and color distortions. In addition, sub-aperture images (SAIs) from different viewpoints exhibit pronounced differences in noise levels, undermining angular consistency and thereby causing biased disparity estimation as well as conspicuous artifacts in synthesized views. Therefore, effectively enhancing light-field images in low light is crucial not only for improving overall image quality but also for ensuring the accuracy of downstream vision tasks.

Early methods for light-field low-light enhancement typically applied single-image methods to each view individually, which failed to effectively model the geometric relationships between views and consequently led to inconsistencies in brightness, contrast, and texture across the enhanced views. To this end, Lamba et al. [4] proposed a light field-specific low-light enhancement method, L3Fnet, which reconstructs each light field view by encoding the geometric structure of all views. Subsequently, some methods [5,6,7] attempted to combine spatial–angular modeling to simultaneously capture inter-view correlations and single-view detail features; however, their insufficient exploitation of spatial–angular correlations limits performance in large-disparity scenes. Therefore, methods [8,9,10] incorporates epipolar information to reorganize the 4D light-field image into different 2D representations and explore the relationships among them. MSPnet [11] constructs view stacks in different directions to leverage disparity-specific information for feature extraction and denoising through averaging. However, these methods typically capture only the limited relationships between neighboring pixels or adjacent views, overlooking the role of frequency-domain representation, and thus fail to achieve a global understanding of the light field’s geometry and illumination with relatively low computational cost. In addition, they do not take into account that light field low-light enhancement is an enhancement in stereoscopic space, resulting in imbalanced enhancement effects across different depth layers and potentially having adverse impacts on downstream tasks such as depth estimation, as shown in Figure 1.

Inspired by the method proposed by Hibbard et al. [12], there is a negative correlation between luminance and distance, and the human visual system does not rely solely on directly perceived pixel luminance when interpreting a scene, but rather perceives three-dimensional structure through the joint contribution of luminance and disparity. Since a light field records the light intensity distribution from multiple viewpoints, the magnitude of disparity directly reflects depth information, and thus luminance variations across different views change with disparity. In addition, depth maps can provide edge information, serving as a structural prior to assist in the enhancement of image details [13]. Therefore, we adopt a depth-guided mechanism that, to some extent, simulates the human ability to perceive the world through geometric understanding under low-light conditions, thereby enhancing the quality and angular consistency of light field images.

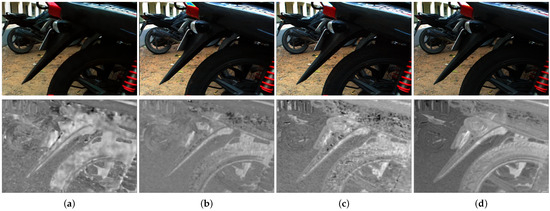

Figure 1.

Visual comparison of the enhancement results and depth estimation results on the L3F-20 dataset [4] between our method and other state-of-the-art methods. (a) LLFlow [14]; (b) DCUNet [9]; (c) Ours; (d) GT.

In this paper, we propose a depth-guided dual-domain progressive light field enhancement method to address the limitations of existing methods in noise suppression and detail restoration. Specifically, we first extract frequency-domain information from the light field to complement its spatial representation, enabling effective fusion of global and local features to improve noise removal effectiveness and texture reconstruction quality. Then, we incorporate depth information from multiple views of the light field and model the correlation between depth and brightness to achieve adaptive brightness adjustment and structural detail refinement. To facilitate mutual enhancement between image restoration and depth estimation, we design a multi-stage progressive learning strategy that allows the model to iteratively improve enhancement quality and structural consistency. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms state-of-the-art methods across multiple evaluation metrics.

Our main contributions can be summarized as follows:

- We propose a depth-guided dual-domain progressive enhancement method for light field images, named DDPNet, which leverages depth information to progressively enhance the image in both the spatial and frequency domains.

- We introduce a Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) module to fuse global and local features of the light field, and propose a Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) module that effectively models the relationship between depth and brightness enhancement, enabling more accurate recovery of illumination and texture details.

- Experimental results demonstrate that our method significantly outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods in terms of reconstruction quality and structural fidelity.

2. Related Work

2.1. Low-Light Image Enhancement

Low-light image enhancement is a classic task in the field of image restoration, aiming to improve image visibility and detail representation under low-light conditions. In recent years, data-driven deep learning methods have achieved remarkable success in low-light enhancement. Following RetinexNet [15], most methods combine neural networks with the traditional Retinex theory to produce restoration results that better align with human visual perception. KinD models multiple degradation factors present in low-light scenes and introduces improved training loss functions to alleviate the unnatural enhancements observed in RetinexNet. LLFlow [14] formulates low-light enhancement as the learning and sampling of a conditional probability distribution, enabling more flexible modeling of complex illumination variations and noise patterns. Zero-DCE [16] proposes an unsupervised enhancement framework that learns image-specific adjustment curves to directly optimize brightness and contrast without requiring paired training data; its upgraded version, Zero-DCE++ [17], significantly reduces model size while maintaining competitive performance, thus improving its practicality in real-world applications. LLFormer [11] introduces an axial attention mechanism that applies self-attention along the height and width dimensions of feature maps, effectively capturing cross-channel contextual information. In recent years, some studies have reformulated low-light enhancement as an image generation problem. For example, LLDiffusion [18] treats enhancement as a conditional generative process, progressively generating a clean image from pure noise using the low-light image as a condition. Although these methods achieve outstanding performance in single-image enhancement tasks, they fail to exploit the angular information of light field images, making it difficult to maintain structural coherence and perceptual quality in light field enhancement tasks.

2.2. Low-Light Light Field Enhancement

Early light field low-light enhancement methods, such as L3Fnet [4], primarily extracted features from all angular views and enhanced each SAI individually. To address L3Fnet’s high computational and memory overhead, its successor FERNet [19] was inspired by the structure of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and adopted a feed-forward network to fuse global, local, and view-specific information, enabling the simultaneous restoration of multiple views, reducing the number of forward passes, and improving efficiency. Subsequently, several methods [5,6,7] began exploring the interaction and fusion between spatial and angular dimensions to better model the structural characteristics of light field data. Among them, Zhang et al. introduced the Retinex theory into light field enhancement and employed an alternating spatial–angular feature extraction strategy, while LRT [7] introduced long-range dependency self-attention mechanisms in both spatial and angular dimensions, though with high computational complexity when processing large-scale light field data. MSPnet [11] reconstructed the light field into multi-directional view stacks and performed cross-view averaging for denoising, achieving strong noise suppression performance. However, this strategy tends to cause over-smoothing in large-disparity scenes, leading to the loss of fine texture details. Another line of methods leveraged disparity information in light fields; for example, Lyu et al. [9] decoupled the light field into spatial, angular, and epipolar plane image (EPI) domains for separate enhancement, fully exploiting the EPI’s advantage in implicitly modeling spatial–angular relationships and achieving good results in texture recovery. Nevertheless, most methods still focus on local spatial feature extraction and lack frequency-domain modeling of the global light field structure, limiting their ability to represent global textures and details. In addition, existing methods generally lack explicit depth-guided mechanisms, resulting in insufficient structural hierarchy in brightness enhancement across different depth layers, which in turn compromises the perceptual consistency and structural fidelity of the enhanced results.

2.3. Light Field Depth Estimation

Light field depth estimation aims to infer the depth of objects in three-dimensional space by analyzing the disparity of the same object across different angular views. EPInet [20] achieved disparity estimation by constructing end-to-end multi-stream EPI encodings. Tsai et al. [21] proposed a view selection network that assigns different weights to each SAI using attention maps to evaluate their contributions to depth estimation. Chen et al. [22] combined a multi-level fusion structure with an attention mechanism, enabling high-accuracy depth estimation even in complex regions. Wang et al. [23] designed convolutions with specific dilation rates and dynamically modulated the pixel contributions of different views, effectively alleviating view distortions caused by occlusion. Yang et al. [24] proposed a hybrid cost volume structure that disentangles and fuses local matching information and global contextual information, while incorporating an occlusion-aware loss, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of light field depth estimation in textureless and occluded regions.

However, these supervised methods rely on real datasets for training, which limits their generalization ability to unseen scenes. To address this issue, some studies have explored unsupervised depth estimation methods. Peng et al. [25] proposed a zero-shot learning framework that generates depth maps through iterative optimization. Li et al. [26] introduced an occlusion-pattern-aware loss to constrain unsupervised depth estimation. In contrast, our task requires depth guidance for all sub-aperture images in the light field, and thus we adopt the unsupervised depth estimation method from [27].

3. Method

3.1. Light Field Representation

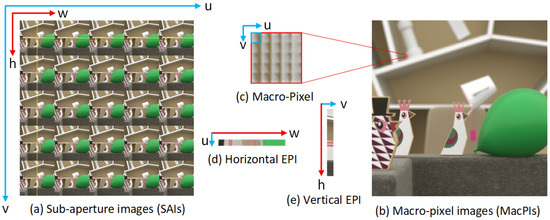

The light field captures light rays originating from different positions and directions in space, and can be represented as a four-dimensional function , where denote the angular dimensions corresponding to the incident direction or views of the light rays, and denote the spatial dimensions representing the position of the light rays in space. For more intuitive visualization, the light field image is often rearranged into sub-aperture images, which consist of images of size arranged along the angular dimensions, Each sub-aperture image is denoted as , as shown in Figure 2. The macro-pixel image (MacPI) rearranges the angular and spatial dimensions of the light field in an interleaved manner, resulting in a large 2D image that preserves both spatial and angular information. The epipolar plane image, on the other hand, represents a slice of the light field showing how pixels vary across viewpoints; its linear patterns reflect the continuity of the scene and can be used to detect object edges, texture information, or estimate depth. Adjusting the luminance and structural details of the light field in the frequency domain can further enhance the enhancement performance.

Figure 2.

Visualization of light field images. (a) Sub-aperture images (SAIs); (b) macro-pixel images (MacPIs); (c) locally enlarged view of the macro-pixel; (d) horizontal EPI (EPI-H) extracted at the position of the horizontal yellow line; (e) vertical EPI (EPI-V) extracted at the position of the vertical yellow line. Here, u and v denote the angular dimensions, while h and w denote the spatial dimensions.

Our network takes the light field function as input and utilizes depth guidance to perform restoration and enhancement in both spatial and frequency domains. Through a progressive process consisting of k enhancement stages, the network ultimately produces an enhanced light field image , achieving high-quality restoration under extremely low-light conditions.

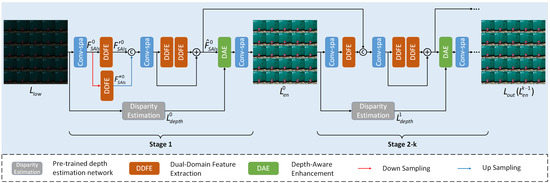

3.2. Network Architecture

The overall architecture of DDPNet is illustrated in Figure 3. This method adopts a depth-guided dual-domain progressive restoration strategy to gradually enhance low-light LF images. In the initial stage, spatical dimension convolutional operations are first applied to the input low-light SAIs to extract high-dimensional features:

where, denotes the high-dimensional features of the input image. ⊗ represents the convolution operation, and is a Conv2D with a kernel size of 3. Then, the Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) module is applied to feature maps at both the original scale and the downsampled scale. This module decouples the spatial domain features of the light field and integrates frequency-domain information to achieve effective multi-scale feature extraction of both global and local representations. Subsequently, the multi-scale features are concatenated and reduced in dimension through convolution along the spatial dimension. Then, two DDFE modules are employed with residual connections to fuse the information and further enhance the feature representation:

where, represents the features enhanced by multiple DDFE modules, and and denote the feature representations extracted at different scales. and denote the downsampling and upsampling operations, respectively. , , and refer to different DDFE modules. Subsequently, we first adopt the pre-trained depth estimation network from method [27] to extract the depth map. Unlike conventional light field depth estimation methods that typically compute the depth of only the central sub-aperture image, this method obtains the depth information of all SAIs at each stage in an unsupervised manner, enabling more accurate illumination and detail enhancement for each SAI. A Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) module is used to establish correlations between the depth maps and the low-light images in both spatial and frequency domains, thereby effectively recovering texture details and luminance information. Afterward, another spatial convolution is applied for dimensionality reduction, yielding the enhanced light field output of the initial stage :

where, denotes the DAE module, and represents the depth map at the first stage. In the subsequent stages, the deep dual-domain features from the previous stage are fused with the shallow features of the current stage, effectively preventing information loss during transmission. This is followed by a depth-aware enhancement operation similar to that in the initial stage. This strategy facilitates mutual optimization between low-light enhancement and depth estimation, thereby progressively improving image quality throughout the multi-stage process.

Figure 3.

The overall framework of DDPNet adopts a k-stage progressive restoration strategy, where each stage comprises depth estimation, dual-domain feature extraction, and depth-aware enhancement.

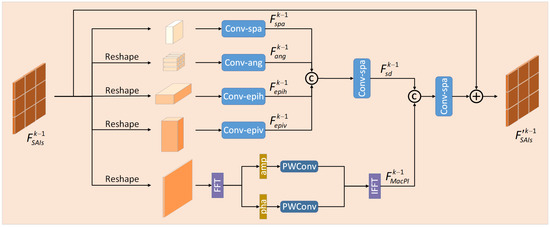

3.3. Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) Module

Existing methods typically reconstruct light field images into simple stacked forms or extract only spatial and angular information, while ignoring the crucial disparity information inherent in light fields. As a result, these methods struggle to fully exploit the potential of light field features when dealing with images containing large disparities. Moreover, due to the high resolution of light field images, directly applying self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies leads to quadratic computational complexity.

Since the spatial domain can effectively capture local geometric and texture information, while the frequency domain has a remarkable advantage in suppressing global noise, combining the two in a complementary manner enables both structural detail recovery and global consistency of the image, thereby significantly improving the overall restoration performance. Therefore, we propose a Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) module. As shown in Figure 4, this module first reorganizes the 4D light field features into multiple forms and applies parallel convolutional operations to extract features along the spatial, angular, and EPI dimensions. Then, spatial convolutions are used to reduce dimensionality while effectively integrating both intra-view and inter-view information, thereby enhancing the representation capacity of light field features:

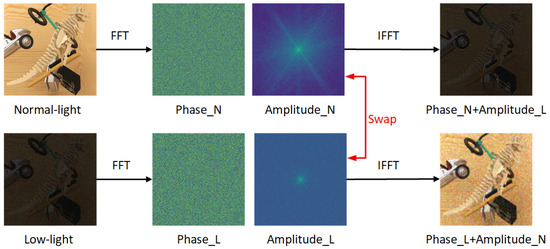

where, is the feature map of the input image at the k-th stage. , , , represent the features extracted along the spatial, angular, EPI-horizontal (epih), and EPI-vertical (epiv) dimensions, respectively, while denotes the fused spatial domain feature. We further perform a frequency-domain transformation on the entire light field image by reorganizing the input features into a Macro-Pixel Image (MacPI) representation to capture global frequency information. According to method [28], in the Fourier frequency domain, the amplitude typically corresponds to image brightness, while the phase encodes structural information. As shown in Figure 5, by swapping the frequency-domain amplitude between the low-light and normal-light images, the original normal-light image becomes darker and the low-light image is significantly brightened. Therefore, we apply a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to the input features, followed by point-wise convolution to adjust the amplitude and phase components separately. An Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT) is then performed to obtain the modulated frequency-domain features:

where, denotes the frequency-domain feature extraction process, and represents the obtained global MacPI frequency-domain features. The frequency-domain features are concatenated with the fused spatial-domain light field features and integrated through a spatial convolution. Subsequently, a residual connection is introduced by adding the fused result to the input features to prevent information loss, ultimately yielding the enhanced output feature :

Figure 4.

Our Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) module adopts a decoupled strategy for spatial-domain feature extraction, in which the light field is reshaped into different two-dimensional representations. For frequency-domain feature extraction, the light field is reshaped into MacPI and processed in the Fourier domain.

Figure 5.

The normal-light and low-light images are each subjected to a fast Fourier transform (FFT) to obtain their respective amplitude and phase spectra. Subsequently, the amplitude spectra of the two images are swapped, and an inverse Fourier transform (IFFT) is applied. As a result of this operation, the original low-light image is enhanced and becomes brighter, while the original normal-light image is dimmed.

3.4. Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) Module

Previous illumination restoration methods mainly rely on two-dimensional semantic information for modeling. However, these methods overlook the inherently three-dimensional nature of illumination: the perceived brightness varies significantly at different depths in human vision. Particularly in light field images, traditional end-to-end restoration methods lack explicit modeling of brightness variations, making it difficult to achieve depth-aware brightness adjustment.

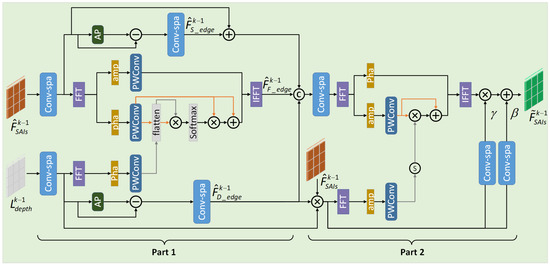

Depth maps can not only enhance the edge structures of low-light images but also enable differentiated brightness enhancement across varying depths and regions, which helps maintain the geometric consistency of light field images. Based on this, we propose a Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) module that models the correlation between depth and low-light images to achieve hierarchical brightness enhancement. Our module consists of two parts: the first part enhances the edge details of the low-light image by leveraging the edge information from the depth map; the second part performs brightness enhancement by modeling the correlation between the depth map and the low-light image, enabling depth-aware luminance adjustment across different regions, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Our Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) module consists of two components: the first part leverages edge information from the depth map in both the spatial and frequency domains to enhance the edge details of low-light images; the second part models the influence of the depth map on image brightness in the spatial and frequency domains, thereby achieving depth-aware luminance adjustment.

As mentioned above, the amplitude and phase in the frequency domain correspond to image brightness and texture, respectively. Therefore, we consider combining spatial and frequency domain features to achieve complementary enhancement. For the input low-light image features and depth map at the k-th stage, we first perform feature mapping using spatial convolutions, and then separately extract their edge information in the spatial domain:

where, denotes the edge features extracted from the low-light image features, and represents the average pooling operation. Similarly, the edge features of the depth map are denoted as . In the frequency domain, we further leverage the phase information of the depth map to modulate the phase components of the low-light image via a cross-modal attention mechanism, thereby obtaining edge-enhanced low-light features in the frequency domain, denoted as :

where, denotes the phase attention map, is the phase component of the low-light feature map, represents the phase of the depth feature map, and is the enhanced phase map. Next, we concatenate and fuse the low-light feature map , the edge features of the low-light image , the edge features of the depth map and edge-enhanced features in the frequency domain to obtain the edge-enhanced feature map.

In the second part, we perform element-wise multiplication between the depth map features and the low-light image features to obtain a relational map that captures their correlations. Then, based on the weights in this relational map, we modulate the amplitude spectrum of the image, thereby enabling targeted brightness enhancement across different depth regions:

where denotes the low-light amplitude spectrum of the feature map, is the amplitude spectrum of the relational map, and represents the enhanced amplitude spectrum. Finally, we apply Spatial Feature Transform (SFT) [29] to modulate the frequency-adjusted features in the spatial domain, resulting in the enhanced feature map .

3.5. Loss Function

Our network is trained by minimizing the reconstruction loss, structural similarity loss, perceptual loss, and frequency-domain loss between the enhanced image and the ground truth . The total loss function is formulated as follows:

where, = = . For the reconstruction loss, we impose an L1 constraint on the intermediate results .

where, denotes the weight of the k-th stage. For the three-stage DDPNet, we set . In the ablation study, when , we set . We also introduce the SSIM loss to prevent artifacts by enforcing structural consistency.

Perceptual loss compares images in the feature space using a VGG-19 [30] network, enabling the generation of high-quality images that better align with human visual perception.

where, denotes the feature map obtained from VGG-19 network. For the frequency-domain loss, we apply L1 loss to constrain both the amplitude and phase components.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Datasets

We evaluated the performance of the proposed method on the publicly available L3F real-world dataset [4] as well as the DCUNet-syn synthetic dataset. The L3F dataset contains real light field images captured using a Lytro Illum camera (Lytro, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). For each scene, a well-exposed light field is first acquired as the ground truth. Then, three low-light versions are generated by reducing the exposure time to 1/20, 1/50, and 1/100 of the ground truth, corresponding to three subsets: L3F-20, L3F-50, and L3F-100. Each exposure-level subset contains 27 distinct scenes, with an angular resolution of 15 × 15 and a spatial resolution of 433 × 625 for each view. Among them, 18 scenes are used for training and the remaining 9 for testing. To reduce the adverse effects of peripheral views and improve computational efficiency, only the central 5 × 5 views are used in our experiments. The DCUNet-syn dataset [9] contains 24 light field images from HCI [31] and 37 images from Inria [32]. The test set includes 2 light field images from HCI and 4 from Inria, where low-light scenarios are simulated by adding noise and reducing exposure.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

We train our model using PyTorch (version 2.2.1) on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and update the network parameters with the Adam optimizer. During training, data augmentation is performed through random horizontal and vertical flips. To reduce the computational cost of light field images, each SAI is cropped into 64 × 64 patches for training. The learning rate is set to , the batch size is 2, and training stops after 180k iterations.

4.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.2.1. Comparison Methods

We compare the proposed DDPNet with three single-image enhancement methods (ZeroDCE++ [17], KinD++ [33], and LLFlow [14]), four light field low-light enhancement methods (L3Fnet [4], FERNet [19], MSPnet [11], and DCUNet [9]), and one light field super-resolution method PDistgNet [34]. For PDistgNet, we remove its pixel shuffle layer and retrained it based on the RGB channels. We use PSNR, SSIM [35], and LPIPS [36] to evaluate the visual quality of the enhanced results.

4.2.2. Quantitative Comparison

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, we conducted quantitative experiments on the real-world L3F dataset [4] and the synthetic low-light light field dataset DCUNet-syn [9], as shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Traditional single-image enhancement methods ignore the correlations between different views, resulting in suboptimal performance in low-light light field image restoration. We also compare our method with several state-of-the-art LF enhancement methods. It is worth noting that the L3F-100 dataset presents a significant challenge due to its severe degradation, leading to relatively low overall performance metrics. The transformer-based PDistgNet [34] shows promising results on synthetic datasets, yet its inference time is considerably high. Among all the methods, our method achieves competitive results in terms of PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS, with a particularly notable improvement in PSNR. This indicates that our method exhibits superior capabilities in noise suppression and detail restoration.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparisons on L3F dataset [4]. Best and second-best results are marked in Red and Cyan, respectively.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparisons on DCUNet-syn dataset [9]. Best and second-best results are marked in Red and Cyan, respectively.

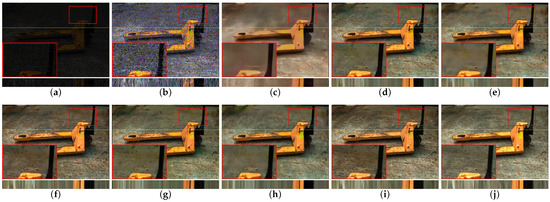

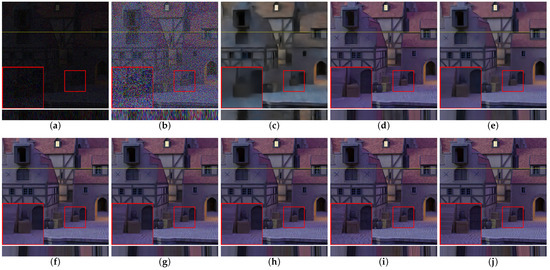

4.2.3. Qualitative Comparison

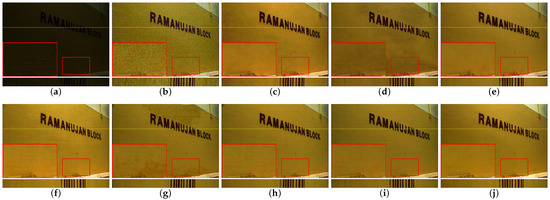

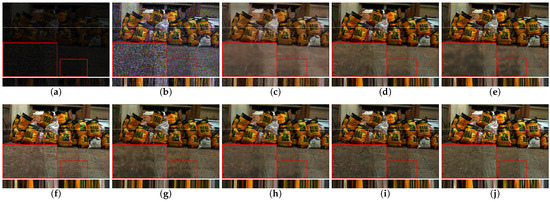

To objectively evaluate the enhancement performance of our method, we conducted qualitative comparisons, as shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. To more clearly observe the overall content of the low-light images, we applied linear brightness amplification with varying degrees to the input images. We enlarged the local regions of the center views from different scenes to demonstrate the restoration quality, and further incorporated the EPIs of the light field to evaluate the geometric consistency of the enhanced light field images. Experimental results demonstrate that directly applying 2D image enhancement methods to light field images, without considering angular information, leads to severe information loss and inconsistent enhancement across views, thereby violating the geometric consistency of the light field, especially in severely underexposed scenes. Light field-specific low-light enhancement methods, such as L3Fnet [4] and FERNet [19], show promising overall restoration performance. MSPnet [11], proposed subsequently, suppresses noise by averaging across multiple directional stacks; however, this often introduces over-smoothing, resulting in the loss of texture details. DCUNet [9], on the other hand, exhibits poor brightness perception in different regions, frequently causing either overexposed or underexposed outputs. In contrast, our method explicitly models brightness variations across different depth levels and integrates disparity information to preserve structural consistency. As a result, it effectively avoids artifacts and better retains the epipolar geometry, achieving more natural and geometrically consistent light field enhancement.

Figure 7.

Visual comparisons of zoomed-in regions (red boxes) and EPIs of the enhanced center SAI by different methods on the L3F-20 dataset [4]. (a) Input (5× amplified); (b) Zero-DCE++ [17]; (c) LLFlow [14]; (d) L3Fnet [4]; (e) FERNet [19]; (f) MSPnet [11]; (g) DCUNet [9]; (h) PDistgNet [34]; (i) Ours; (j) GT.

Figure 8.

Visual comparisons of zoomed-in regions (red boxes) and EPIs of the enhanced center SAI by different methods on the L3F-50 dataset [4]. (a) Input (10× amplified); (b) Zero-DCE++ [17]; (c) LLFlow [14]; (d) L3Fnet [4]; (e) FERNet [19]; (f) MSPnet [11]; (g) DCUNet [9]; (h) PDistgNet [34]; (i) Ours; (j) GT.

Figure 9.

Visual comparisons of zoomed-in regions (red boxes) and EPIs of the enhanced center SAI by different methods on the L3F-100 dataset [4]. (a) Input (15× amplified); (b) Zero-DCE++ [17]; (c) LLFlow [14]; (d) L3Fnet [4]; (e) FERNet [19]; (f) MSPnet [11]; (g) DCUNet [9]; (h) PDistgNet [34]; (i) Ours; (j) GT.

Figure 10.

Visual comparisons of zoomed-in regions (red boxes) and EPIs of the enhanced center SAI by different methods on the DCUNet-syn dataset [9]. (a) Input; (b) Zero-DCE++ [17]; (c) LLFlow [14]; (d) L3Fnet [4]; (e) FERNet [19]; (f) MSPnet [11]; (g) DCUNet [9]; (h) PDistgNet [34]; (i) Ours; (j) GT.

4.2.4. Computational Efficiency

We evaluated the number of parameters and inference time of the 5 × 5 central subviews on the L3F-20 [4] dataset using an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, and the results are shown in Table 1. It can be observed that single-image-based low-light enhancement methods generally incur significantly higher computational costs when applied to light field data as network complexity increases, compared to methods specifically designed for light field enhancement. Although our network introduces a depth estimation module, resulting in slightly higher parameter count and inference time than some end-to-end methods, its enhancement performance surpasses theirs. DCUNet [9] and PDistgNet [34] outperform our model in certain metrics, but their inference time is excessively long. Overall, our method achieves a favorable balance between performance and efficiency.

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. The Numbers of Iterative Stages

As shown in Table 3, the model’s parameter count increases progressively as the number of stages increases from 2 to 4. When , all performance metrics reach their optimal values, indicating that increasing the number of stages and parameters does not necessarily lead to better performance.

Table 3.

Ablation study on the number of iterative stages on the L3F-20 dataset [4]. The best performance results are marked in Red.

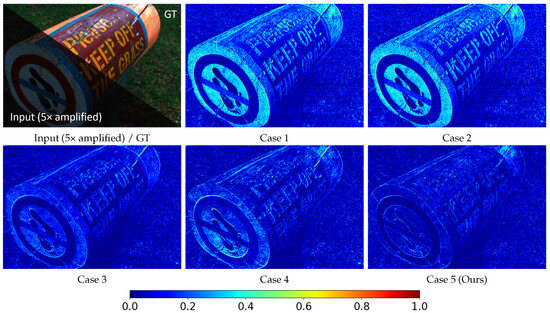

4.3.2. DDFE

To verify the impact of the dual-domain structure in the DDFE module on overall performance, we conducted an experiment by removing its frequency-domain branch. As shown in Table 4, the network exhibited a decrease in both PSNR and SSIM metrics. The visual comparison in Figure 11 also reveals that removing the frequency-domain branch results in larger errors compared to the ground-truth image. These results indicate that the frequency-domain branch plays a significant role in capturing global information and suppressing noise.

Table 4.

Ablation study of the DDFE and DAE on the L3F-20 dataset [4]. “Spa” denotes the spatial domain branch in DDFE, while “Fre” represents the Fourier frequency domain branch in DDFE. “Part 1” refers to the edge enhancement part in DAE, and “Part 2” corresponds to the brightness enhancement part in DAE. The best performance results are marked in Red.

Figure 11.

Visual comparison of grayscale error maps for different components on the L3F-20 dataset [4].

4.3.3. DAE

We further conducted ablation experiments on the two submodules of the DAE module, the texture enhancement part and the brightness enhancement part. As shown in Table 4, completely removing the DAE module results in a significant decline across all evaluation metrics; removing the texture enhancement submodule causes a noticeable drop in PSNR, while removing the brightness enhancement submodule leads to a substantial decrease in SSIM. The visual comparisons in Figure 11 further confirm these findings: removing the texture enhancement part leads to a significant increase in edge errors, while removing the brightness enhancement part results in deviations in overall brightness. These results demonstrate that the DAE module effectively leverages depth information to guide low-light image enhancement, playing a vital role in both detail restoration and brightness correction.

4.3.4. Analysis of Disparity Estimation Errors

Since disparity estimation in light fields inherently contains errors, we simulate different types of degradation on the estimated depth maps to evaluate the impact of depth map quality on enhancement results and the robustness of our method under unreliable guiding information. The degradations are divided into two categories: the first adds mixed noise (Gaussian noise, uniform noise, and salt-and-pepper noise) to the estimated depth maps; the second applies blurring using a Gaussian kernel of size 5 with . Experimental results are shown in Table 5. Adding noise significantly reduces enhancement performance, especially in terms of PSNR, while blurring the depth maps has a relatively minor effect. Nevertheless, enhancement results under both types of degradation still outperform those obtained without using depth estimation, indicating that our method maintains a certain level of robustness under unreliable guidance. Moreover, higher-quality depth maps have a more positive impact on low-light enhancement performance.

Table 5.

Ablation study on the impact of depth estimation quality by applying different degradations to the depth maps on the L3F-20 dataset [4]. The best performance results are marked in Red.

4.3.5. MacPI Resolution

To investigate the impact of MacPI size on the accuracy of frequency-domain feature extraction, we downsampled the MacPI using bilinear interpolation to extract frequency-domain features, and then upsampled them back to the original resolution for concatenation with spatial features. The downsampling scales were set to 1, 1/2, and 1/4. Since downsampling reduces the number of pixels, the number of FFT output points also decreases, which weakens the ability to distinguish low- and high-frequency details. As shown in Table 6, experimental results indicate that downsampled MacPIs perform worse in feature extraction compared to images at the original resolution, and the performance gradually deteriorates as the downsampling scale decreases.

Table 6.

Ablation study on the MacPI size on the L3F-20 dataset [4]. The best performance results are marked in Red.

4.3.6. Loss Function

We conducte ablation experiments by configuring different loss components. As shown in Table 7, since the reconstruction loss provides the most fundamental and stable constraint, we retain it and individually remove the structural loss and frequency-domain loss for comparison. The experimental results indicate that removing any of these loss terms leads to a decrease in PSNR and SSIM, while the LPIPS metric increases. These results fully validates the rationality and effectiveness of each loss component in our design.

Table 7.

Ablation study of , , ,and on the L3F-20 dataset [4]. The best performance results are marked in Red.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

In this paper, we propose a depth-guided progressive light field low-light enhancement method, named DDPNet. This method performs multi-stage depth estimation to progressively enhance light field images in both the spatial and frequency domains, thereby effectively improving image quality. We design a Dual-Domain Feature Extraction (DDFE) module, which decouples and extracts spatial-domain features along different dimensions of the light field, while leveraging frequency-domain information to adjust the global representation and enhance feature expressiveness. Additionally, we introduce a Depth-Aware Enhancement (DAE) module, which explicitly uses the estimated depth maps to guide the restoration of texture details and luminance under low-light conditions. Extensive experiments on multiple real-world datasets demonstrate that our method outperforms state-of-the-art methods in terms of reducing artifacts, enhancing detail reconstruction, and maintaining multi-view consistency, showing superior performance in light field low-light enhancement.

Although our method demonstrates remarkable enhancement performance and benefits subsequent tasks such as depth estimation, excessive noise and errors in depth map utilization may still compromise the overall restoration quality. To address this issue, future research may introduce more robust depth map preprocessing and refinement mechanisms. Meanwhile, considering that objects closer to the camera typically exhibit larger motion amplitudes and thus suffer from more severe blurring compared to distant objects, we also plan to incorporate depth-estimation-based motion deblurring as a preprocessing step, thereby further exploring low-light light field enhancement in dynamic scenes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Y.; investigation, T.Y.; methodology, X.W.; visualization, X.W.; resources, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61902151).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available at https://github.com/MohitLamba94/L3Fnet, https://github.com/lyuxianqiang/LFLL-DCU, accessed on 1 July 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fiss, J.; Curless, B.; Szeliski, R. Refocusing plenoptic images using depth-adaptive splatting. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Computational Photography (ICCP), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2–4 May 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, S.; Goldluecke, B. Variational light field analysis for disparity estimation and super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 36, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Zimmer, H.; Pritch, Y.; Sorkine-Hornung, A.; Gross, M.H. Scene reconstruction from high spatio-angular resolution light fields. ACM Trans. Graph. 2013, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, M.; Rachavarapu, K.K.; Mitra, K. Harnessing multi-view perspective of light fields for low-light imaging. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 30, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Lam, E.Y. An effective decomposition-enhancement method to restore light field images captured in the dark. Signal Process. 2021, 189, 108279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. PMSNet: Parallel multi-scale network for accurate low-light light-field image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 2041–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Meng, N.; Lam, E.Y. LRT: An efficient low-light restoration transformer for dark light field images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 4314–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Liu, G.; Lu, Z.; Li, K.; Yang, J. Efficient Low-Light Light Field Enhancement with Progressive Feature Interaction. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 9, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Hou, J. Enhancing low-light light field images with a deep compensation unfolding network. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 4131–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lin, J.; Chen, K.; Huang, W.; Wang, Z.; Yuanlong, D. RLNet: Reshaping Learning Network for Accurate Low-Light Light Field Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2025, 11, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, S. Multi-stream progressive restoration for low-light light field enhancement and denoising. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2023, 9, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, P.B.; Goutcher, R.; Hornsey, R.L.; Hunter, D.W.; Scarfe, P. Luminance contrast provides metric depth information. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 220567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, R. Multimodal low-light image enhancement with depth information. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 4976–4985. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wan, R.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Chau, L.P.; Kot, A. Low-light image enhancement with normalizing flow. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 2604–2612. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Wang, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Deep retinex decomposition for low-light enhancement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.04560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; Loy, C.C.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Cong, R. Zero-reference deep curve estimation for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1780–1789. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Guo, C.; Loy, C.C. Learning to enhance low-light image via zero-reference deep curve estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 4225–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, A.; Fan, H.; Han, S.; Liu, S. Low-light image enhancement with wavelet-based diffusion models. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, M.; Mitra, K. Fast and efficient restoration of extremely dark light fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 1361–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, C.; Jeon, H.G.; Yoon, Y.; Kweon, I.S.; Kim, S.J. Epinet: A fully-convolutional neural network using epipolar geometry for depth from light field images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4748–4757. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Ouhyoung, M.; Chuang, Y.Y. Attention-based view selection networks for light-field disparity estimation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 12095–12103. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y. Attention-based multi-level fusion network for light field depth estimation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 1009–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, Z.; Yang, J.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Occlusion-aware cost constructor for light field depth estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 19809–19818. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Deng, J.; Chen, R.; Cong, R.; Ke, W.; Sheng, H. Disentangling Local and Global Information for Light Field Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 3418–3426. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Zero-shot depth estimation from light field using a convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2020, 6, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Deng, C.; Han, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, T. Opal: Occlusion pattern aware loss for unsupervised light field disparity estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Yue, H.; Li, K.; Yang, J. Disparity-guided light field image super-resolution via feature modulation and recalibration. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2023, 69, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Jin, Z. Fourllie: Boosting low-light image enhancement by fourier frequency information. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 7459–7469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Dong, C.; Loy, C.C. Recovering realistic texture in image super-resolution by deep spatial feature transform. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Honauer, K.; Johannsen, O.; Kondermann, D.; Goldluecke, B. A dataset and evaluation methodology for depth estimation on 4D light fields. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 November 2016; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, X.; Guillemot, C. A framework for learning depth from a flexible subset of dense and sparse light field views. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 28, 5867–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. Kindling the darkness: A practical low-light image enhancer. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1632–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Yue, H.; Yang, J. Efficient light field image super-resolution via progressive disentangling. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 6277–6286. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).