Abstract

Commercial electricity is increasingly being generated by renewable energy sources, and the photovoltaic conversion of sunlight is the fastest-growing renewable source. In addition to its rapid growth, solar electricity generation has seen very dramatic reductions in cost, as well as continuing increases in its conversion efficiency and installation lifetime. The growth between 2014 and 2024 in the record cell-level performance of four commercial technologies based on Si, CdTe, CuInGaSe2, and perovskites is compared with each other, with the highest achieved by GaAs, which is primarily used in space applications. Si, CdTe, and CuInGaSe2 have each narrowed the gap with their ideal efficiencies by about 5%, whereas perovskites, starting from a much lower base, have improved by closer to 20%, and GaAs, already much closer to its ideal value, has advanced by only a modest additional amount. Other important comparisons such as costs, stability, and environmental impact are not addressed here.

1. Introduction

There is an increasing demand for renewable energy to limit global warming and climate change as addressed by the Paris Agreement (COP21, 2015) [1]. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) net-zero scenario, the share of wind and solar electricity will need to increase to 40% by 2030 and reach nearly 70% by 2050 [2]. Within the field of renewable energy, photovoltaic (PV) generation is the fastest-growing technology, as it is a distributed energy resource with low-cost and easy installation that helps to decarbonize society. In 2024, PV exceeded a global installed capacity of 2 TWdc and is postulated to reach 75 TWdc by 2050 [3]. However, competing technologies have emerged in response to the increasing impact of photovoltaic electricity.

This article reviews the cell-level, lab-scale performance of some of the commercially available solar cells, including silicon (Si), cadmium telluride (CdTe), copper indium gallium diselenide (CIGS), perovskite and gallium arsenide (GaAs). The status and potential of some of these solar cells have been analyzed previously by R.M. Geisthardt [4], M. Topic in 2014 [5], and recently by the authors [6,7]. Here, we revisit the ten years of progress and compare what has changed for each. This comparison should provide insight into the status and trends of the different technologies, but other factors such as manufacturing costs, transition of cells to panels, and stability issues will also play a large role in the development of each technology. The selection of the highest efficiencies here was based on the periodic compilations by M. Green et al. [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], which set generally recognized criteria for declaring a record efficiency. In addition, originally published current–voltage curves were digitized to the extent practical for the figures that follow and to evaluate key secondary parameters.

2. Record Solar Cell Efficiencies (2014 vs. 2024)

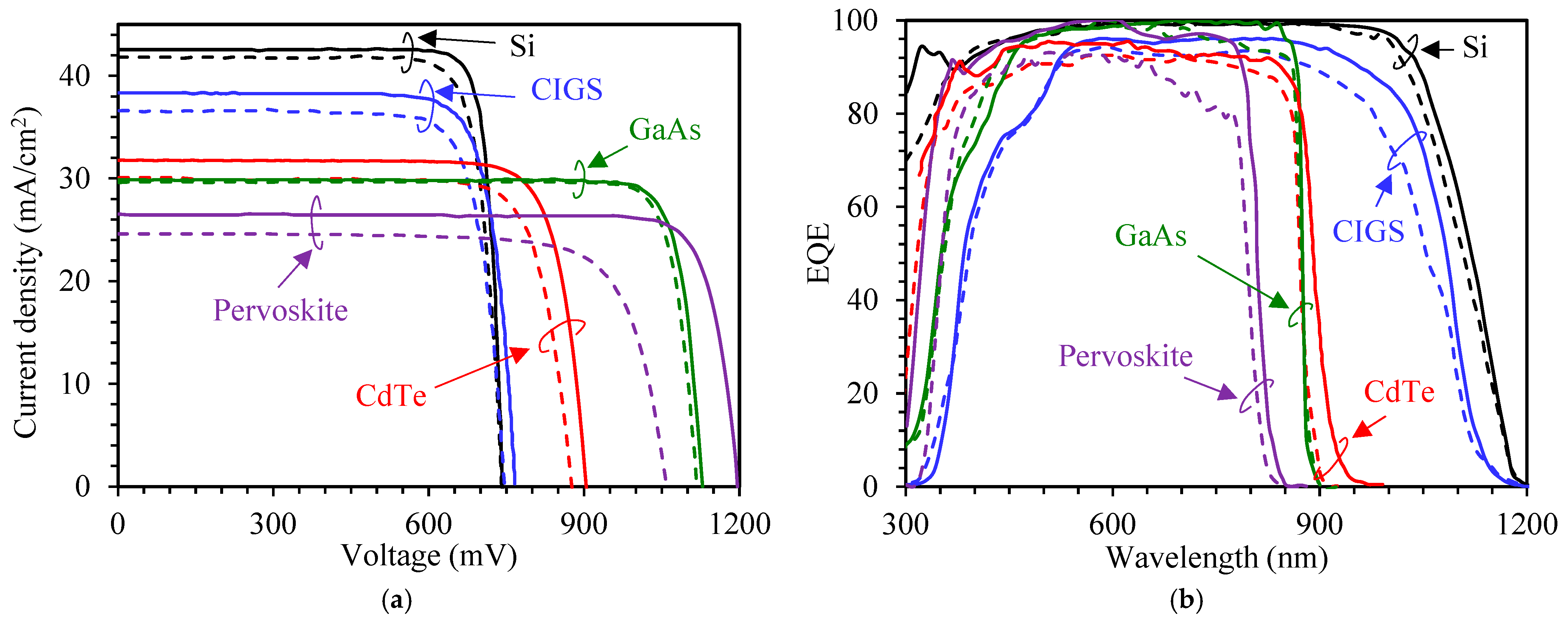

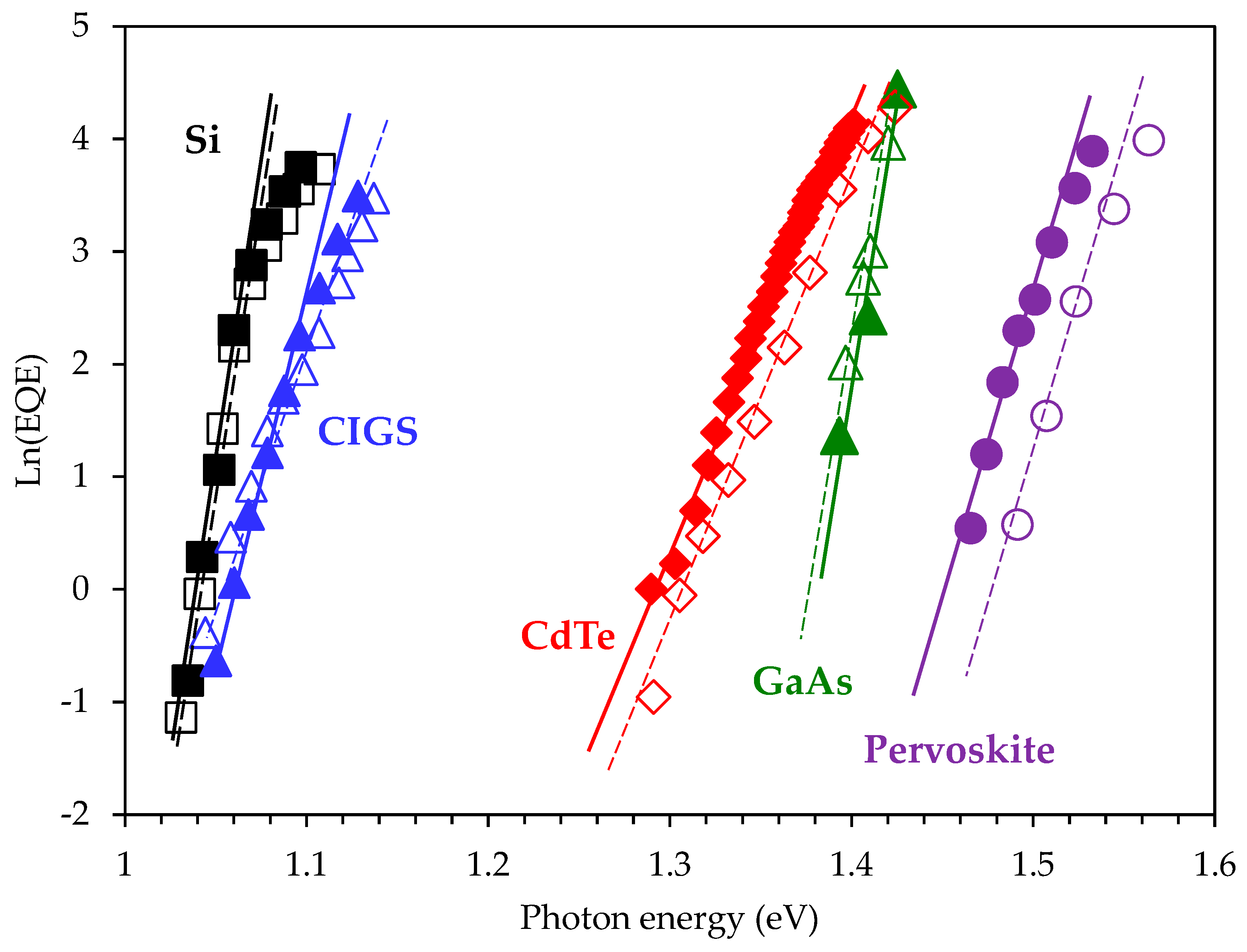

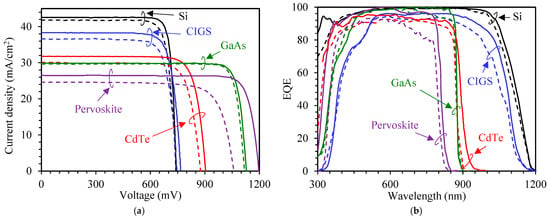

Figure 1a,b show the current–voltage (J-V) and external quantum efficiency (EQE) curves of record solar cells in 2014 (dotted lines) and 2024 (solid lines) of different technologies measured under AM 1.5G [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The manufacturers of each, the standard detailed photovoltaic parameters contrasted with ideal Shockley–Queisser (SQ) values based on their band gap, and the references for each are given in Table 1. The effective band gap of these solar cells was approximated as 30% of the EQE maximum; as can be seen in Figure 1b, the band-gap cutoffs, especially for the thin-film cells, were not always clean. In addition, the effective band gaps of the CIGS, CdTe, and perovskite cells decreased slightly in the 2024 record devices, which is reflected in their cutoff wavelengths (Figure 1b). This indicates variation in the elemental composition of the absorber layers.

Figure 1.

(a) J-V and (b) EQE curves from five technologies of the record solar cells in 2014 (dotted lines) and 2024 (solid lines).

Table 1.

Photovoltaic parameters of the record solar cells (2024 vs. 2014) measured under AM 1.5G.

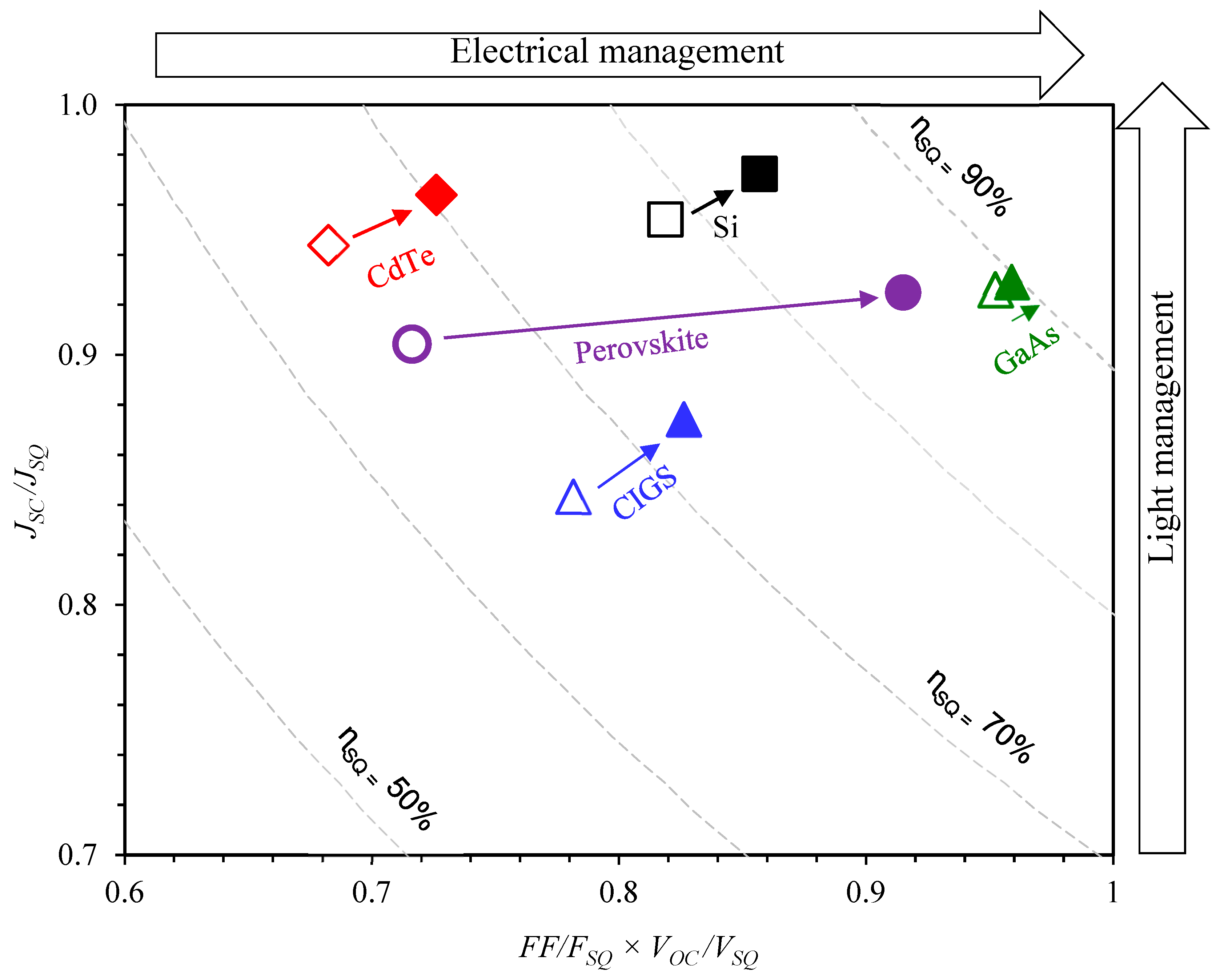

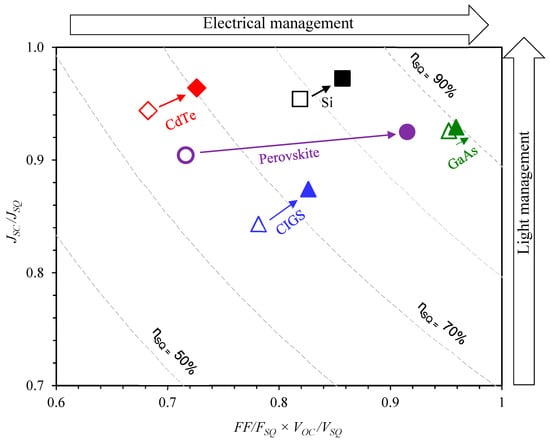

3. Optical and Electrical Efficiencies

Optical and electrical efficiencies are analyzed to understand light and charge carrier management properties. When normalized to the SQ limit, optical efficiency (J/JSQ) represents the degree of light coupling, absorption, and trapping in the active layer(s) of the cells and depends on the carrier collection. Electrical efficiency represents the product of voltage (V/VSQ) and fill factor (FF/FSQ) ratios. The voltage ratio is mainly related to the degree of recombination of carriers in the bulk, surfaces, and interfaces (front and back). The fill factor ratio is related to parasitic resistance and other electrical nonidealities in devices. As can be seen in Figure 2, all solar cell technologies showed at least some improvement in both optical and electrical efficiency over the ten-year period.

Figure 2.

Current and voltage/fill factor product of the record solar cells normalized to the Shockley–Queisser limit. Open symbols are for 2014 and filled symbols for 2024.

As can be seen, single-crystal GaAs is closest to ideal and has reached nearly 90% of its SQ limit. The Si and perovskite technologies have both achieved approximately 85% of their limits. This demonstrates that, regardless of the grain boundaries in polycrystalline technology, their efficiency can rival the level of single-crystalline material. Perovskite solar cells showed a major increase from ~0.65 to ~0.85 in SQ utilization, and CdTe and CIGS demonstrated more moderate improvements, during those 10 years. All the solar cell technologies, except for CIGS, achieved nearly 95% of their JSC limits. Therefore, future efficiency improvements, especially for CdTe, will need to focus on electrical efficiency.

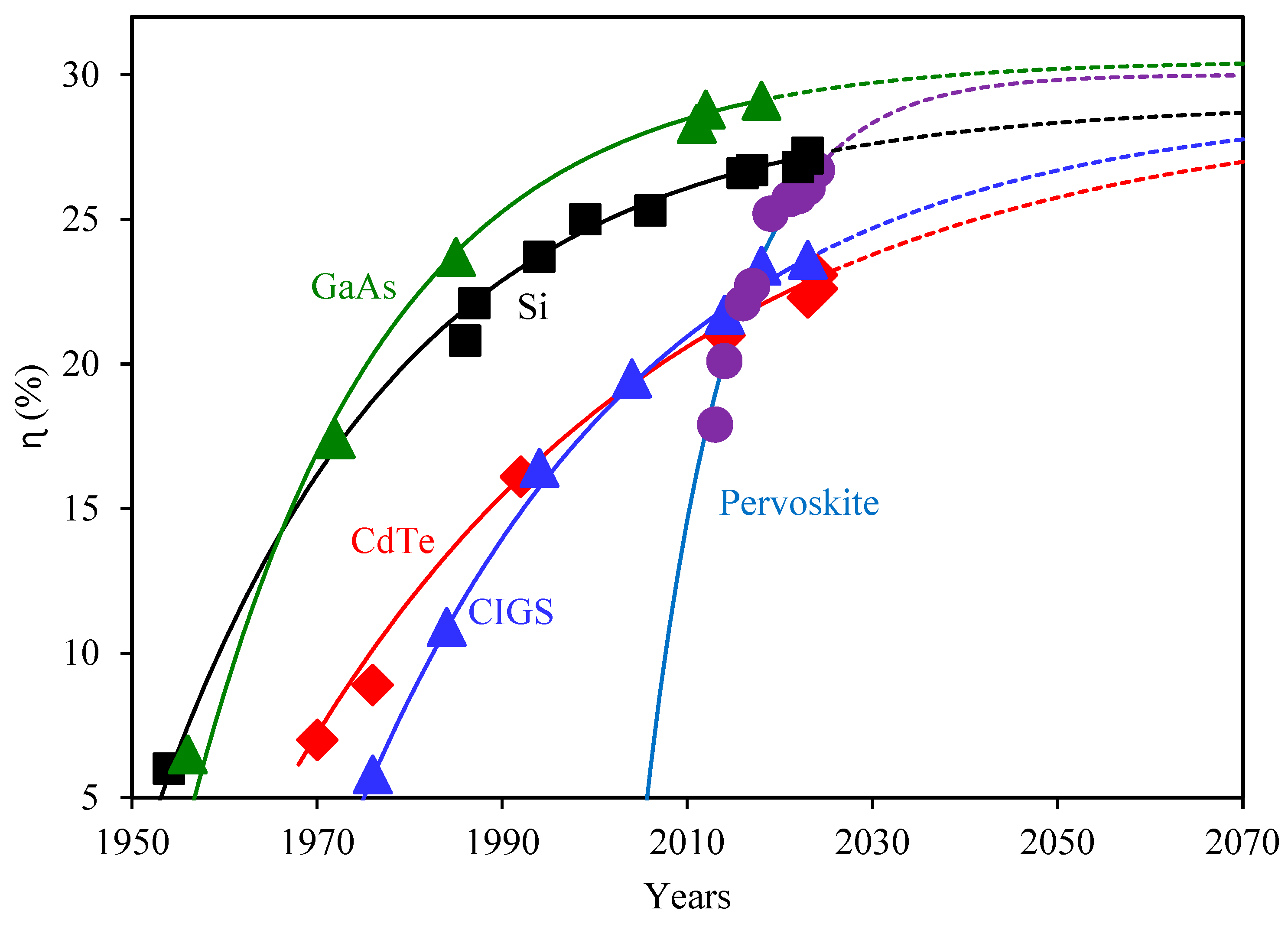

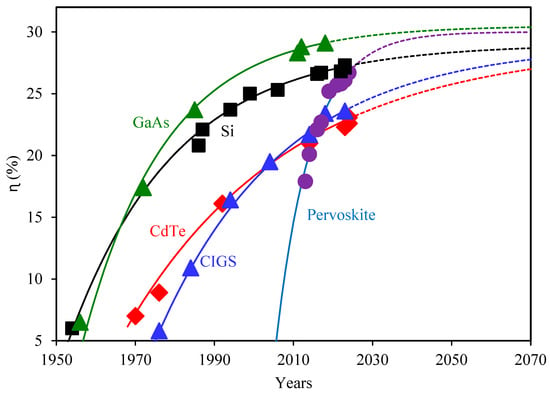

4. Efficiency Trends

Figure 3 summarizes the long-term development trend of the different solar cell technologies. The efficiencies represented with solid symbols for the various solar cell technologies are taken from Refs. [18,19], and the extrapolation following Ref. [20] shows that the progress of the GaAs, Si, and perovskite solar technologies is approaching the practical limit, whereas CdTe and CIGS have more room for further efficiency improvement.

Figure 3.

Record efficiencies of various types of solar technology. Dashed lines follow Goetzberger’s extrapolation equation [20].

4.1. Silicon Technology

Silicon PV technology dominates the large-scale commercial market. Crystalline–silicon solar cells, based on wafer technology, account for over 90% of the global photovoltaics module production for terrestrial applications. In Si technology, JSC greater than 42 mA/cm2 has been reported [21,22] in lab-scale devices, which represents an excellent optical efficiency of nearly 98%. PERC (Passivated Emitter and Rear Cell), IBC (Integrated Back-Contact), and TOPCon (Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact) exhibit relatively superior optical efficiency [21]. On the other hand, HIT (Heterostructure with Intrinsic Thin Layer), HBC (Heterojunction Back-Contact), and SHJ (Silicon Heterojunction) have superior electrical efficiency due to the formation of strong built-in electric fields that separate electron–hole pairs effectively [9,21,22,23]. VOC and FF above or near 751 mV and 86% have been reported in these types of solar cells [22,23]. Hydrogenated doped amorphous or nanocrystalline Si are generally used to passivate the surface of crystalline Si. This layer helps to form better junction quality for higher efficiency. Further improvements in efficiency in Si technology are still possible with (i) the use of higher-quality wafers, (ii) excellent passivation with a p-nc-Si:H stack, (iii) a damage-free laser patterning process, (iv) lower contact resistivity between a-Si:H (or p-nc-Si:H) and TCO at the front end, and (v) multi-layer antireflecting coatings.

4.2. CdTe Technology

For thin-film PV technology, the U.S-based company First Solar, which produces CdTe modules, makes up ~40% of the utility scale market in the U.S and has a large number of modules installed worldwide. CdTe technology also has an optical efficiency of nearly 95% in lab-scale devices [6,7], which is primarily due to the use of higher-band-gap emitters and alloying with selenium (Se). Se incorporation and Group V doping have significantly improved the minority carrier lifetime, carrier concentrations, and radiative efficiency [24]. However, the activation ratio of dopants has been poor. This leads to the formation of carrier trap energies and increases band fluctuations [25]. In the past, activation ratios approaching 100% have been reported in single-crystal thin-film CdTe deposited by photo-assisted molecular beam epitaxy [26]. It is suggested that introduction of light during the growth process increases the rate of Te desorption from CdTe surfaces and favors the incorporation of substitutional acceptors (AsTe). Illumination provides additional energy beyond that accessible by thermal means, which promotes the atomic mobility of anions/cations species during film growth that in turn promotes crystallinity. Polycrystalline CdTe technology should also be able to take advantage of the photo-assisted deposition process for the activation of Group V elements and crystallinity improvement. A further efficiency boost is also possible by better passivation of the rear interface and improvements in back-contact conductivity and band alignment. The selenium profile, thickness optimization, and grain-boundary passivation of the absorbers are additional important factors that should also be investigated in detail.

4.3. Perovskite Technology

Perovskite technology is also moving towards large-scale commercialization. The defect-tolerant nature of perovskites enables perovskite solar cells to maintain both high optical and electrical efficiencies. Within a short span of time, organic–inorganic perovskite solar cells have demonstrated the highest power conversion efficiency among polycrystalline thin-film solar technologies, mainly due to composition engineering, fabrication protocols, interface passivation, charge carrier management, advanced device architecture, and contact design [16,27,28]. The primary challenges that must be addressed for perovskite technologies to be commercially successful are (i) stability and durability, (ii) power conversion efficiency at scale, (iii) manufacturability, and (iv) technology validation. Lead (Pb)-based perovskite materials pose a greater toxicity issue than CdTe and GaAs due to their higher water solubility and lower vaporization temperature. This increases the danger of environmental exposure in the event of module encapsulation failures such as breakage or fire. Many of these issues can be overcome by replacing the cations in the halide perovskite (ABX3) with a Pb-free, all-inorganic composition [28].

4.4. CIGS Technology

CIGS technology has been promising, but it is not currently being produced on a large scale for terrestrial applications. The optical efficiency of CIGS technology (~87%) in lab-scale devices is lower than that of the Si and CdTe technologies due in part to the typical use of cadmium sulfide (CdS) as a buffer layer [10], though several other buffer layers have been explored. However, CdS forms a good homojunction due to the substitution of Cu vacancies (VCu) at the near-surface region of the absorber layer with Cd ions forming a CdCu (donor) [29]. Band-gap tuning by varying the In/Ga and in some cases Se/S ratio is a useful strategy to reduce interfacial recombination [30,31]. Recently, heavy-alkali-metal treatments with potassium (K), rubidium (Rb), and cesium (Cs), as well as silver incorporation at the absorber layer, have boosted both optical and electrical efficiency. Post-treatments with alkali metals modify absorbers at the near-surface region as well as bulk and grain boundaries in positive ways [32], whereas silver alloying has been shown to increase grain growth, enhance reaction rates during phase evolution, and reduce structural disorder [10]. Further efficiency boosts in CIGS technology are possible with the use of higher-band-gap emitters, better control of the stoichiometry ratio, and general improvements in material quality.

4.5. GaAs Technology

GaAs and related alloys have been the core of multijunction and concentrator solar cells for space applications. As a result of research and development, GaAs solar cells offer the highest photovoltaic conversion efficiencies of any single-junction technology. GaAs efficiency was improved by changing the device structure from a homojunction to a heteroface structure, and then to a double-hetero structure [33]. Photon recycling is an important concept in GaAs-based solar cells. It refers to the process by which photons absorbed in the GaAs absorber are radiatively re-emitted and then reabsorbed in the same GaAs absorber to again generate electron–hole pairs. This process increases carrier density within the device, which in turn leads to greater quasi-Fermi level splitting, thus increasing electrical efficiency [34]. Further efficiency improvements may come through still higher-quality epitaxial layers with less or no lattice mismatch of active layers, further reduction in defect density, increased interface passivation, and reduced leakage current. The high manufacturing cost of GaAs solar cells can be reduced using low-cost 2D materials as templates and/or by growing absorber layers using dynamic hydride vapor phase epitaxy (D-HVPE). D-HVPE enables the creation of abrupt heterointerfaces with fast deposition rates [35], which can reduce the fabrication cost.

5. Additional Cell Comparisons

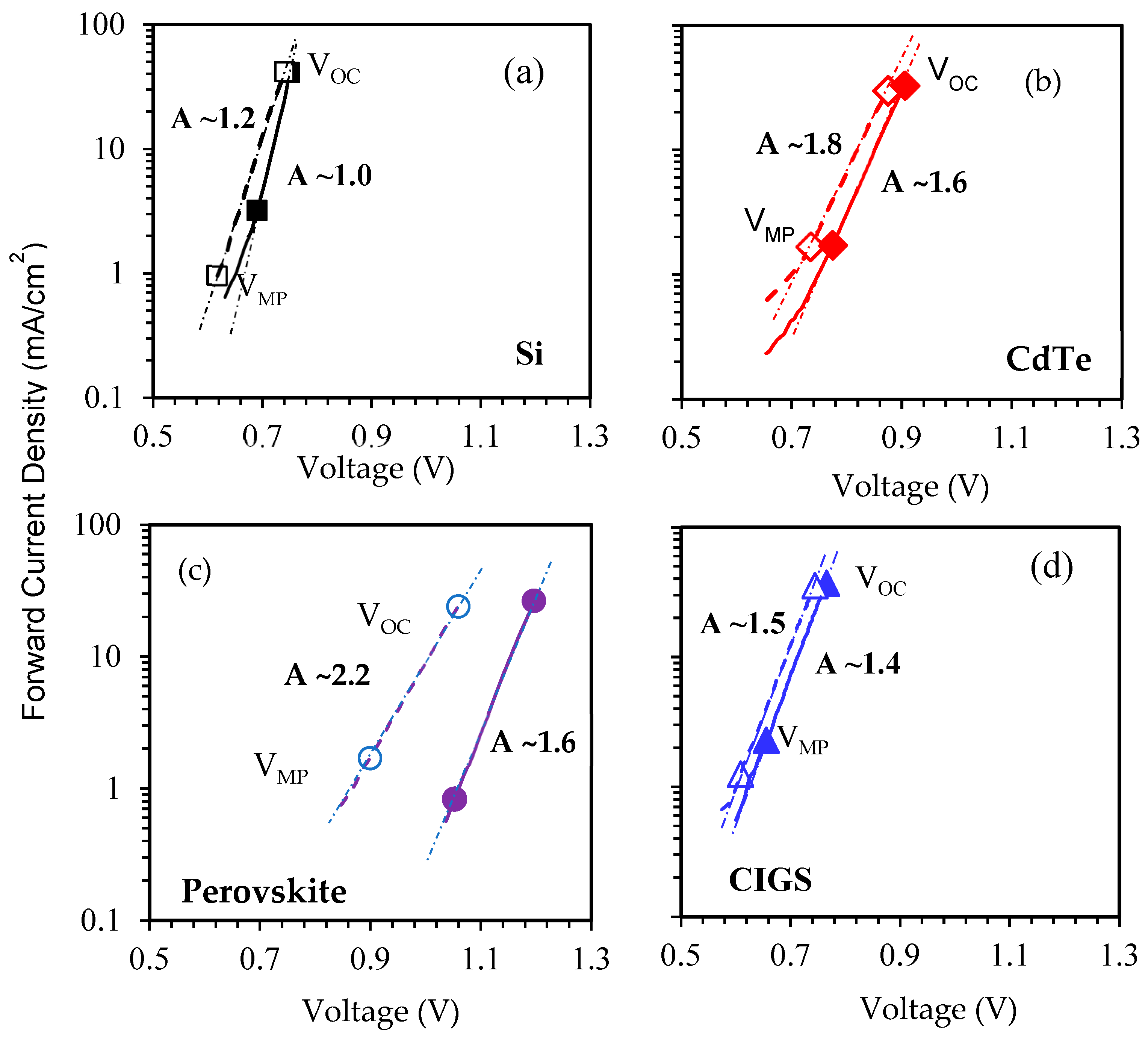

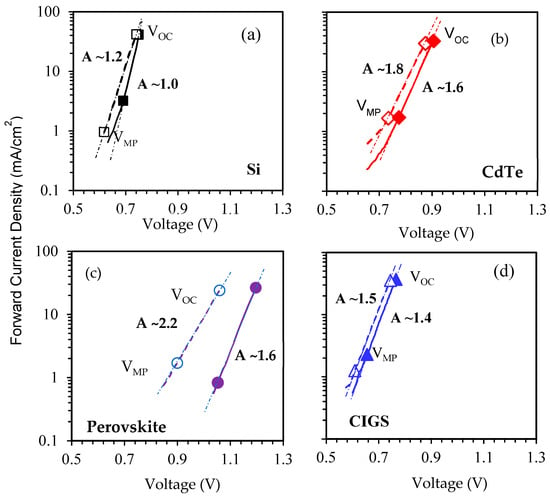

In addition to the visual comparison of J-V and EQE for the record cells in Figure 1 and the listing of standard parameters in Table 1, a comparison of two less obvious parameters is also helpful. One of these is the diode quality factor A, which reflects a primary fill factor loss, and the other is the Urbach energy from EQE that is partially responsible for voltage loss.

The A-factor is found from the slope of the forward current, the difference between total current and photocurrent, plotted against voltage on a log scale with emphasis on data between VMP and VOC [36,37]. In the ideal case, it is 1.0, but recombination involving states within the band, along with perhaps other factors, leads to larger values of A. Forward current plots and their changes in the past ten years are shown in Figure 4; GaAs, which gave a value close to 1.0 for A in this range for both years, is omitted.

Figure 4.

Forward current vs. voltage to determine ideality factors A. Dashed fits are for 2014 and solid for 2024. GaAs was close to 1.0 in both years.

The primary message from Figure 4 is that the A-factor, and hence recombination loss, is larger for the polycrystalline technologies. For example, A = 1.6 for the CdTe and perovskite cells shown corresponds to a fill factor reduction of about 5% [7]. The four technologies shown in Figure 4 have all seen reductions in A-factor over the ten-year period, but the impact for the perovskites has clearly been the largest.

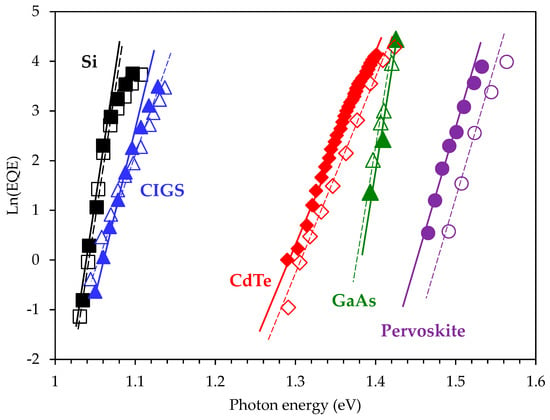

Urbach energy (Eu), which can be derived from EQE through the absorption spectrum of photons slightly below the absorber band gap, is another measure of solar cell quality [38,39,40]. These band tails, which are generally exponential, are shown in Figure 5 for the same cells as in the earlier figures. As can be seen, the slopes of the curves for each type of cell have not changed significantly over the ten years, and the Urbach energies deduced here are consistent with published values [13,25,41,42,43,44,45].

Figure 5.

Ln(EQE) for photon energies below but approaching the band gap for the record solar cells of 2014 (open symbols) and 2024 (filled symbols).

The Urbach energy of a cell is an indicator of fluctuations in its band energies which can result from several possible causes, including lattice distortions and charging effects, particularly at grain boundaries. A major consequence of these distortions is a reduction in voltage. As seen in Table 2, based on unpublished calculations, the Eu values and likely voltage reductions from the band tails are greater for the polycrystalline cells. Of particular note, the low activation to date for CdTe dopants has necessitated large amounts of dopants and greater potential for distortion and voltage loss.

Table 2.

Urbach energies for Figure 5 and estimated voltage reductions.

Both the diode quality factors and the Urbach energies extracted from J-V and EQE measurements play a significant role in the differences among the PV technologies. They are, therefore, useful for identifying the larger loss mechanisms and for tracking progress over time.

6. Conclusions

The five PV technologies highlighted here have all seen efficiency enhancements during the last ten years and now achieve a top-end range between 23 and 30% for single-junction cells. Each now has features that are attractive for different applications, and each general category except for silicon includes significant variations in composition. Silicon and CdTe are clearly commercially competitive today, perovskites and possibly CIGS are moving in that direction, and GaAs along with various alloys and partners plays a central role in space power. Each of the five has achieved a high current density with the remaining JSC losses well understood. The single-crystal technologies now have fill factors approaching their ideal, whereas the polycrystalline ones are reduced by an additional 5% or so due in large part to excessive recombination. The voltage deficit compared to the ideal ranges from about 2% for GaAs to 20% for CdTe, and the larger losses are less well understood than those from either current or fill factor. It has been a productive ten years for PV performance growth, and even more so for reductions in cost and the impact on electrical generation.

Future increases in efficiency will vary among the technologies and will largely depend on the amount of effort dedicated to each and on creative ideas to better evaluate current cell structures and quite possibly develop alternative ones. Especially for the thin-film technologies, it will continue to be important to quantify individual losses and to focus on strategies to minimize the larger ones. The performance of photovoltaic cells has been making impressive progress, and there is clearly room for additional progress towards the ideal limits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K., C.K. and J.R.S.; review and editing, I.K., C.K. and J.R.S.; supervision, J.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, Managing and Operating Contractor for the National Renewable Energy Laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy under Agreement SUB-2021-10714.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be available on request to authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. “The Paris Agreement”, unfccc.int. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Haegel, N.M.; Verlinden, P.; Victoria, M.; Altermatt, P.; Atwater, H.; Barnes, T.; Breyer, C.; Case, C.; De Wolf, S.; Deline, C.; et al. Photovoltaics at multi-terawatt scale. Waiting is not an option. Science 2023, 380, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisthardt, R.M.; Topic, M.; Sites, J.R. Status and Potential of CdTe Solar-Cell Efficiency. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2015, 5, 1217–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topic, M.; Geisthardt, R.M.; Sites, J.R. Performance Limits and Status of Single-Junction Solar Cells with Emphasis on CIGS. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2015, 5, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, I.; Kasik, C.; Sites, J.R. Performance of State-of-the-Art CdTe-Based Solar cells: What Has Changed? IEEE J. Photovolt. 2024, 14, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasik, C.; Jost, M.; Khatri, I.; Topic, M.; Sites, J.R. Top-Performing Photovoltaic Cells Compared to the Shockley-Queisser Limit. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2025, 15, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Siefer, G.; Hinken, D.; Rauer, M.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Hao, X. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 64). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2024, 32, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuko, K.; Shigematsu, M.; Hashiguchi, T.; Fujishima, D.; Kai, M.; Yoshimura, N.; Ichihashi, Y.; Mishima, T.; Matsubara, N.; Yamanishi, T.; et al. Achievement of More Than 25% Conversion Efficiency with Crystalline Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cell. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2014, 4, 1433–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Siefer, G.; Hao, X.; Jiang, J.Y. Solar Cell Efficiency Tables (Version 65). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2025, 33, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Emery, K.; Hishikawa, Y.; Warta, W.; Dunlop, E.D. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 45). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2015, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Noh, J.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Ryu, S.; Seo, J.; Seok, S. High-performance photovoltaic perovskite layers fabricated through intramolecular exchange. Science 2015, 348, 1234–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Kiselman, K.; Gargand, O.D.; Martin, N.M.; Babucci, M.; Lundberg, O.; Wallin, E.; Stolt, L.; Edoff, M. High-concentration silver alloying and steep back-contact gallium grading enabling copper indium gallium selenide solar cell with 23.6% efficiency. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.; Hariskos, D.; Wuerz, R.; Kiowski, O.; Bauer, A.; Friedlmeier, T.M.; Powalla, M. Properties of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 solar cells with new record efficiencies up to 21.7%. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2015, 9, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Siefer, G.; Hao, X. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 63). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2023, 32, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Emery, K.; Hishikawa, Y.; Warta, W.; Dunlop, E.D. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 40). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2012, 20, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.; Ebinger, J.H.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Hao, X. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 57). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2021, 29, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Lab. “Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart”, nrel.gov. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Yamaguchi, M.; Lee, K.H.; Araki, K.; Kojima, N.; Yamada, H.; Katsumata, Y. Analysis for efficiency potential of high-efficiency and next-generation solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2018, 26, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzberger, A.; Luther, J.; Willeke, G. Solar cells: Past, present, future. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2002, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Altermatt, P.P.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Shang, X.; Xu, J.; Feng, Z.; Shen, H.; Verlinder, P.J. Technology evolution of the photovoltaic industry: Learning from history and recent progress. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2023, 3, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Yang, M.; Ru, X.; Wang, G.; Yin, S.; Peng, F.; Hong, C.; Qu, M.; Lu, J.; Fang, L.; et al. Silicon heterojunction solar cells with up to 26. 81% efficiency achieved by electrically optimized nanocrystalline-silicon hole contact layers. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Müller, R.; Benick, J.; Feldmann, F.; Steinhauser, B.; Reichel, C.; Fell, A.; Bivour, M.; Hermle, M.; Glunz, S.W. Design rules for high-efficiency both-sides-contacted silicon solar cells with balanced charge carrier transport and recombination losses. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.; Li, X.; Reich, C.; Shan, X.; Zhang, W.; Nagle, T.; Bok, L.; Bicakci, E.; Rosenblatt, N.; Modi, D.; et al. Arsenic-Doped CdSeTe Solar Cells Achieve World Record 22.3% Efficiency. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2023, 13, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuciauskas, D.; Nardone, M.; Bothwell, A.; Albin, D.; Reich, C.; Lee, C.; Colegrove, E. Why increased CdSeTe charge carrier lifetimes and radiative efficiencies did not result in voltage boost for CdTe solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, R.L.; Hwang, S.; Giles, N.C.; Schetzina, J.F.; Dreifus, D.L.; Myers, T.H. Arsenic-doped CdTe epilayers grown by photoassisted molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1989, 54, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Mao, K.; Cai, F.; Meng, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, T.; Yuan, S.; Xu, Z.; Feng, X.; Xu, J.; et al. Reducing nonradiative recombination in perovskite solar cells with a porous insulator contact. Science 2023, 379, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, T.; Kulkarni, A.; Kim, G.M.; Oz, S.; Jena, A.K. Perovskite Solar Cells: Can We Go Organic-Free, Lead-Free and Dopant-Free? Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1902500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T.; Kunioka, A. Direct evidence of Cd diffusion into Cu(In,Ga)Se2 thin films during chemical-bath deposition process of CdS films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 74, 2444–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, I.; Fukai, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sugiyama, M.; Nakada, T. Effect of potassium fluoride post-deposition treatment on Cu(In,Ga)Se2 thin film and solar cells fabricated onto sodalime glass substrates. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Energy 2016, 155, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T.; Ohbo, H.; Watanabe, T.; Nakazawa, H.; Matsui, M.; Kunioka, A. Improved Cu(In,Ga)(S,Se)2 thin film solar cells by surface sulfurization. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Energy 1997, 49, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, I.; LaGrow, A.P.; Bondarchuk, O.; Nicoara, N.; Sadewasser, S. Effect of solution-processed cesium carbonate on Cu(In,Ga)Se2 thin-film solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2024, 32, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M. High Efficiency GaAs-Based Solar Cells. In Post-Transition Metals; Diamond Light Source: Oxford, UK, 2021; p. 107. ISBN 978-1-83968-261-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, B.M.; Nie, H.; Twist, R.; Spruytte, S.G.; Reinhardt, F.; Kizilyalli, I.C.; Higashi, G.S. 27.6% Conversion efficiency, a new record for single-junction solar cells under 1 sun illumination. In Proceedings of the 2011 37th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 19–24 June 2011; pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J.T.; Schulte, K.L.; Ptak, A.J.; Simon, J. Development of HVPE-Grown III-V Solar Cells Passivated with AlInP. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Photovoltaics Specialists Conference (PVSC), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 5–10 June 2022; p. 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sites, J.R.; Liu, X. Performance Comparison Between Polycrystalline Thin-Film and Single-crystal Solar Cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 1995, 3, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sites, J.R.; Liu, X. Recent efficiency gains for CdTe and CuIn1−xGaxSe2 solar cells: What has changed? Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 1996, 41–42, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troviano, M.; Taretto, K. Urbach Energy in CIGS extracted from quantum efficiency analysis of high performance CIGS solar cells. In Proceedings of the 24th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Hamberg, Germany, 21–25 September 2009; pp. 2933–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, T.; Carron, R.; Sevilla, G.T.; Fu, F.; Pisoni, S.; Romanyuk, Y.E.; Buecheler, S.; Tiwari, A.N. Efficiency Improvment of Near-Stoichiometric CuInSe2 Solar Cells for Application in Tandem Devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantana, J.; Kawano, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Mavlonov, A.; Minemoto, T. Impact of Urbach energy on open-circuit voltage deficit of thin-film solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2020, 210, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, G.D. Urbach edge of crystalline and amorphous silicon: A personal review. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1992, 141, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A. Self-Consistent Optical Parameters of Intrinsic Silicon at 300 K including Temperature Coefficients. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturge, M.D. Optical Absorption of Gallium Arsenide Between 0.6 and 2.75 eV. Phys. Rev. 1963, 129, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R.; Tiedje, T. Temperature Dependence of the Urbach Edge in GaAs. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 78, 5609–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.D.; Holovsky, J.; Moon, S.J.; Loper, P.; Niesen, B.; Ledinsky, M.; Haug, F.J.; Yum, J.H.; Ballif, C. Organometallic Halide Perovskites: Sharp Optical Absorption Edge and Its Relation to Photovoltaic Performance. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).