Abstract

Research has shown that neural machine translation performs poorly on low-resource and specific domain parallel corpora. In this paper, we focus on the problem of neural machine translation in the field of electrical engineering. To address the mistranslation caused by the Transformer model’s limited ability to extract feature information from certain sentences, we propose two new models that integrate a convolutional neural network as a feature extraction layer into the Transformer model. The feature information extracted by the CNN is fused separately in the source-side and target-side models, which enhances the Transformer model’s ability to extract feature information, optimizes model performance, and improves translation quality. On the dataset of the field of electrical engineering, the proposed source-side and target-side models improved BLEU scores by 1.63 and 1.12 percentage points, respectively, compared to the baseline model. In addition, the two models proposed in this paper can learn rich semantic knowledge without relying on auxiliary knowledge such as part-of-speech tagging and named entity recognition, which saves a certain amount of human resources and time costs.

1. Introduction

Neural machine translation (NMT) aims to use computers to translate one language into another, and it plays a critical role in various scientific fields. Since 2014, NMT has developed rapidly, from recursive neural networks [1], to convolutional neural networks [2], and then to the Transformer neural network based on self-attention [3], which has achieved good results. Among several NMT models, Transformer performs the best, both in terms of efficiency and translation quality.

As various scientific fields continue to develop, the demand for NMT is also increasing rapidly. Different professional fields have different professional corpora, and some fields have very limited parallel corpora resources. Traditional NMT cannot meet the translation needs of some professional fields. The English–Chinese corpus in the field of electrical engineering is a typical low-resource corpus. The traditional Transformer does not perform well in the English–Chinese corpus in the field of electrical engineering, often causing mistranslation or misinterpretation of certain feature information in sentences, which makes it difficult for personnel in the electrical industry to use professional equipment and read professional English literature. The field of electrical engineering plays a crucial role in the development of many scientific fields. Therefore, it is essential to study how to design an efficient and stable model on a small-scale parallel corpus to improve the current situation of NMT in the field of electrical engineering.

Low-resource neural machine translation has long been an area of interest in natural language processing, and many researchers have made significant efforts to address this problem. Common improvement methods include data augmentation, introducing prior knowledge, and structural improvements. Tonja used monolingual source-side data to improve low-resource neural machine translation and achieved significant results on the Wolaytta–English corpus, further fine-tuning the best-performing self-learning model which resulted in +1.2 and +0.6 BLEU score improvements for Wolaytta–English and English–Wolaytta translations, respectively [4]. Mahsuli, MM proposed a method to model the length of a target (translated) sentence given the source sentence using a deep recurrent neural structure—and apply it to the decoder side of neural machine translation systems to generate translation sentences with appropriate lengths which have a better quality [5]. Pham, NL; Nguyen, V; and Pham, TV used back-translation to enhance the parallel database of English–Vietnamese machine translation, significantly improving the translation quality of the model [6]. Laskar, SR improved English–Assamese machine translation through pre-training models, and the best MNMT model, Transformer (transliteration-based phrase-augmentation), attained scores of +0.58, +1.86 (BLEU) [7]. Park, YH enhanced low-resource neural machine translation data through EvalNet and the NMT systems for English–Korean and English–Myanmar, built with the guidance of EvalNet, and achieved 0.1~0.9 gains in BLEU scores [8]. While these methods have achieved good results, they often require significant time and cost in the data preprocessing stage and have certain drawbacks. Dhar, P introduced bilingual dictionaries to improve Sinhala–English, Tamil–English, and Sinhala–Tamil translation and introduced a weighted mechanism based on small-scale bilingual dictionaries to improve the measurement of semantic similarity between sentences and documents [9]. Gong, LC achieved good results on several low-resource datasets by guiding self-attention with syntactic graphs [10]. Hlaing, ZZ added an additional encoder to the transformer model to introduce part-of-speech tagging, improving Thai-to-Myanmar, Myanmar-to-English, and Thai-to-English translation, outperforming such models developed through the existing Thai POS tagger in terms of BLEU scores (+0.13) and chrF scores (+0.47) for Thai-to-Myanmar, and BLEU scores (+0.75) and chrF scores (+0.72) for Myanmar-to-Thai translation pairs [11]. Considering that convolutional neural networks can extract feature information from sentences, this paper integrates a convolutional neural network as a feature extraction layer into the Transformer model. This method can introduce feature information into the Transformer model without additional processing of the corpus, improving the translation quality of the Transformer model while also saving research time and costs. The main contributions of this article are as follows:

In order to address the issue of feature information misinterpretation and omission in the corpus of electrical engineering with Transformer, a method is proposed to integrate a convolutional neural network as a feature extraction layer into Transformer, which effectively improves the translation accuracy of the model.

Two new model structures are proposed based on Transformer, and the specific structures of the two models are introduced in Section 3 and Section 4, respectively.

Comparative experiments and ablation experiments are designed to verify the performance of the two models proposed in this paper on the dataset of electrical engineering, and their performance is compared with the baseline model, demonstrating that the Transformer model integrated with a convolutional neural network has a better performance.

2. Model

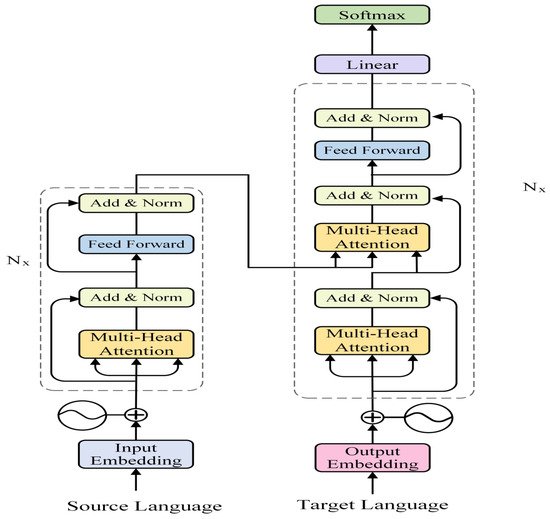

This paper adopts the Transformer model proposed by Google’s machine translation team in 2017 as the baseline model, which mainly consists of four parts: input layer, output layer, encoder, and decoder (the structure of the baseline model [3] is shown in Figure 1). Since its introduction, Transformer has shown an outstanding performance in many natural language-processing tasks. The models proposed in this paper are all based on the baseline model but have improved upon it. Considering the weak ability of Transformer to extract local feature information, a convolutional neural network can be used to extract feature information, which can compensate for the shortcomings of Transformer. In this paper, we improve the traditional Transformer structure by integrating a convolutional neural network composed of pooling and convolutional layers as a feature information extraction layer into Transformer. We fuse the feature information separately at the source language side and target language side and obtain two new models: Source-Side-CNN-Transformer (SSCT) and Target-Side-CNN-Transformer (TSCT).

Figure 1.

Baseline model.

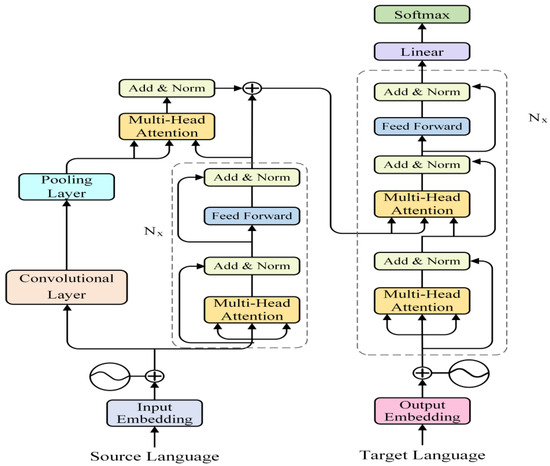

The structure of SSCT is shown in Figure 2. Compared to the baseline model, SSCT adds a feature information extraction layer on the left side of the encoder, which consists of convolutional and pooling layers. Its purpose is to perform local feature extraction on the source language vectors after passing through the embedding layer. In order to integrate the convolutional neural network as the feature extraction layer into the Transformer model, SSCT connects the convolutional layer with the embedding layer of the baseline model, facilitating the convolutional layer to extract features from the source language vectors. In addition, a multi-head attention mechanism is added to the entire model framework, allowing the pooling layer of the feature extraction layer to be associated with the encoder part of the baseline model, thereby fully integrating the feature extraction layer into the Transformer model. The role of the multi-head attention mechanism between the convolutional neural network and the source language encoder is to fuse the locally extracted feature vectors from the feature extraction layer with the output vectors from the encoder. The fused vector is then used as the input to the decoder’s context multi-head attention mechanism, which is associated with the contextual information in the decoder. This enables the decoder to effectively learn the relationship between global information and feature information.

Figure 2.

Source-Side-CNN-Transformer.

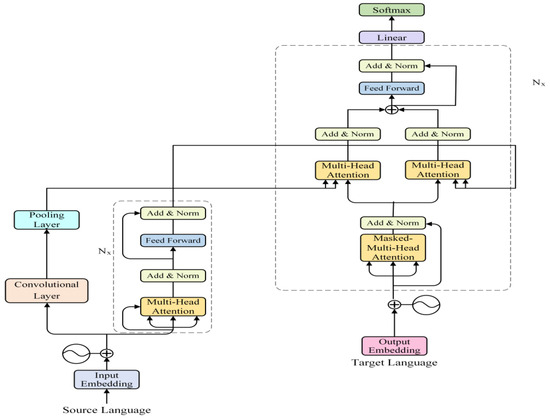

TSCT and SSCT share the same structure for the feature information extraction layer but differ in their integration methods. As shown in Figure 3, TSCT also connects the convolutional layer to the embedding layer. However, in the second sub-layer of the decoder, an additional multi-head attention mechanism is introduced (on the left side of the global attention mechanism). This allows the pooling layer of the feature extraction layer to be connected to the global attention of the decoder, enabling it to receive feature information. The attention calculation is performed between the feature information and the internal information of the decoder, allowing the decoder to learn the relationship between feature information and global information comprehensively. This integration reduces translation errors, mistranslations, and other phenomena that occur in the Transformer model.

Figure 3.

Target-Side-CNN-Transformer.

3. Source-Side-CNN-Transformer

3.1. Embedding and Positional Encoding

The Transformer model cannot directly process text sequences; thus, it needs to map raw data with high dimensions to low-dimensional data through embedding layers, converting text into vector form so that the data can be processed by neural networks [12,13]. For any language, the position and arrangement of words in a sentence are very important. They are not only a part of the grammatical structure of the sentence but also important concepts for expressing semantics. If the position and sequence of a word in a sentence are different, the meaning of the entire sentence will deviate. The Transformer model itself does not have the ability to learn sequential information like an RNN, so it needs a positional encoding layer to combine the sequential information with the word vectors and input them to the transformer, enabling the model to learn sequential information.

The two models proposed in this article have not made any changes to the embedding layer or positional encoding layer and still use the baseline model’s embedding layer and positional encoding layer [3]. Defining the source language sequence after word segmentation as , the target language sequence is defined as , and the numerical identifier is defined as . Taking the embedding process of the source language as an example (the embedding process of the source language and the target language are the same), after linear transformation (Equation (1)), it is represented as , and then the position information of each word (Equation (2)) is added to the embedding layer to obtain a result with positional information (Equation (3)):

where is the numerical identifier, represents the linear transformation, is the result after linear transformation, dim is the word vector dimension, is the positional information, and is the word vector with positional information.

3.2. Encoder

In this section, no changes have been made to the encoder of the baseline model, which is composed of N = 6 independent layers stacked together. Each encoder contains two sub-layers: multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feedforward neural network. Each sub-layer is followed by a residual network and a normalization layer. The encoder takes the source language vectors processed by the embedding layer as the input for the multi-head self-attention mechanism and performs attention calculation and normalization processing on it (Equation (4)). Finally, the output of the encoder is obtained through the feedforward neural network (Equation (5)).

represents the output of the i-th layer of the encoder. The output of each layer is used as the input for the next layer. The input for the first layer of the encoder is the embedded source language vector. represents multi-head self-attention mechanism, represents the feedforward neural network, and represents the residual connection and layer normalization.

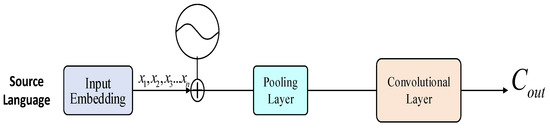

3.3. Feature Extraction Layer

Convolutional neural networks are generally used for image classification and object detection in the field of computer vision. However, since the proposal of Text CNN in 2014 [14], there have been more and more works applying convolutional neural networks to natural language processing tasks. Considering the strong ability of convolutional neural networks to extract local features, which can compensate for the weak ability of Transformer to extract local information, this article selects a convolutional neural network composed of a convolutional layer with a height of 3 and a width of 512 and a max-pooling layer with a height of 2 and a width of 1 as the feature extraction layer of the model (Figure 4). The parameters of the convolution kernel is shown in Table 1. The role of the convolutional layer is to extract feature information from the sentence, while the role of the max-pooling layer is to select the extracted feature information from the convolutional layer.

Figure 4.

Feature information extraction layer.

Table 1.

The parameters of the convolution kernel.

3.3.1. Convolutional Layer

The input of the convolutional layer is the sentence of which is represented as the vector matrix . The convolution is composed of filters, each of which extracts features from the corresponding vector matrix, producing feature (where the maximum sentence length is 100 and dim is 512):

where represents the vector matrix, is the activation function, represents the filters and represents the maximum sentence length. Each filter extracts features from windows of each input matrix, producing feature vectors , and then filters are used to process m sequentially, producing feature map :

where represents the feature vectors and represents the feature map.

3.3.2. Pooling Layer

The pooling layer first selects the maximum value in the adjacent feature maps , and then normalizes the selected feature maps using the tanh function to obtain the feature information :

The reason for selecting the max-pooling layer is because we believe that its mechanism can extract more precise feature information and reduce the impact of useless information. If we were to use the average pooling layer, the extracted information may contain more useless information, leading to the poor performance of the model. To validate our idea, we conducted a comparative experiment between models with a max-pooling layer and an average pooling layer. The experimental results (Table 2) demonstrated that the model with the max-pooling layer had a better performance. The relevant parameter settings and the models used for the comparative experiments on pooling layers are described in Section 5.1 and Section 5.2 of the manuscript.

Table 2.

Comparative experiment of pooling layer.

3.4. Attention Fusion Layer

In this article, the context multi-head attention mechanism is used to fuse all of the outputs of the encoder and the output of the feature extraction layer, which allows for sufficient correlation between the local feature information extracted by the convolutional neural network and the vectors output by the encoder. The calculation process of the fusion is shown in Equation (11).

, , and represent the output of the attention fusion layer, encoder, and feature extraction layer, respectively. Influenced by previous works [15,16,17], and are concatenated along the last dimension of to calculate the balancing factor:

where is the balancing factor, is the activation function, and the value of y is (0~1). Finally, a simple weight-based sum operation is adopted for the calculation of the attention fusion layer output:

3.5. Decoder

The decoder is similar to the encoder, consisting of N = 6 independent layers. However, each layer of the decoder has an additional sub-layer, which is composed of a multi-head attention mechanism, residual connections, and normalization. This sub-layer is used to receive outputs from the encoder. The calculation process of multi-head attention in the first sub-layer of the decoder is shown in Equation (14):

represents the output of the i-th layer of the decoder. Each layer of the decoder uses the output of the previous decoder layer as its input. The input of the first decoder layer is the target language after embedding. In the second sub-layer, and are used as inputs for the context multi-head attention calculation (Equation (15)). After that, the output is passed through a feedforward neural network to obtain the final output of the decoder (Equation (16)).

4. Target-Side-CNN-Transformer

Due to the fact that the embedding layer and feature extraction layer of TSCT are the same as those of SSCT, this chapter will not introduce these two parts in detail. Readers can refer to Section 3.1 and Section 3.3 of this paper for specific details.

4.1. Encoder

The encoder used in the TSCT model is consistent with the encoders used in the baseline model and SSCT. Therefore, its structure will not be described in detail in this section (please refer to Section 3.2 for specific details on the calculation process of the TSCT encoder). The calculation process of the TSCT encoder is as follows.

represents the output of the i-th layer of the encoder. The output of each layer is used as the input for the next layer. The input for the first layer of the encoder is the embedded source language vector, and represents the total output of the source language encoder.

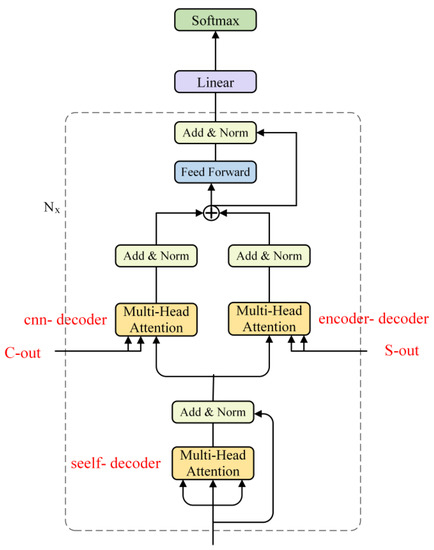

4.2. Decoder

Since the feature information is the input to the decoder in the TSCT model, a CNN-Decoder attention mechanism needs to be added to the decoder unit of the baseline model to receive the output from the feature information extraction layer, facilitating further fusion of the feature information and global information. The improved decoder unit has three sub-layers: a self-attention sub-layer, a multi-head attention sub-layer composed of Encoder–Decoder and CNN-Decoder, and a fully connected feedforward network sub-layer.

The specific structure of the decoder is shown in Figure 5. The attention mechanisms in the TSCT model are Self-Decoder, Encoder–Decoder, and CNN-Decoder. The internal structures and calculation methods of these three attention mechanisms are the same, and their main difference lies in the query vector Q and key–value pairs K and V:

Figure 5.

The decoder of TSCT.

The role of Self-Decoder is to learn the target information fully; thus, its query vector Q, key K, and value V are all source sentence vectors after embedding. The calculation process is shown in Equation (19).

Encoder–Decoder is mainly used to transmit encoder information to the decoder, so that better weight allocation can be achieved based on the target information for the source language representation vector obtained by the encoder during the decoding process. Therefore, the query vector Q of Encoder–Decoder is the output of Self-Decoder, and the key–value pairs K and V still come from the output vectors of the encoder and have the same numerical values. The calculation process is shown in the Equation (20).

The main role of CNN-Decoder is to transmit feature information to the decoder, so that the target information in the decoder can be fully associated with the feature information. Therefore, the query vector Q of CNN-Decoder is the output of Self-Decoder, and the K and V are the outputs of the feature information extraction layer.

By using a balancing mechanism to control the information flow [15,16,17], more valuable information can be obtained. In this paper, and are concatenated on the last dimension of to calculate the balancing coefficient .

A simple summation operation is performed to obtain :

5. Experiment

In this part, we conducted experiments and research about the two models proposed in this paper on the Chinese–English parallel corpus in the field of electrical engineering. We compared the models proposed in this paper with the baseline model and conducted ablation experiments on the two models proposed in this paper.

5.1. Dataset

All the datasets used in this paper are Chinese–English parallel corpora in the field of electrical engineering, mainly collected from certain Chinese and English materials in the field of electrical engineering, including several professional books [18,19,20,21], equipment manuals, literature, and some technical forums and official websites related to electrical engineering. The training set used in the experiment has about 190,000 bilingual parallel corpora, and the validation set and test set each have 2000 bilingual parallel sentence pairs.

5.2. Parameter Settings

We used the open-source system OpenNMT [22] to implement the baseline model Transformer. In terms of data processing, the sentence length in the corpus was limited to within 100, that is, sentences longer than 100 were filtered out, and the vocabulary size was set to 44,000. Chinese segmentation was conducted using Jieba, and English segmentation was conducted using NLTK. During the training process, the dimension of word vectors and the hidden layer dimension of the encoder and decoder were both set to 512. The batch size was set to 64, and the Adam optimization algorithm was used. The dropout rate was set to 0.1. A total of 25,000 steps were trained in this experiment, and the model was validated every 1000 steps. The beam search method was used in decoding, with a beam size of 5 and other parameters using OpenNMT’s default parameters. All parameters in the experiment were kept consistent (Table 3), and the translation results were evaluated using BLEU [23]. All experiments were conducted on the same GPU device, specifically the RTX-3090 model.

Table 3.

Experimental parameters.

5.3. Experiment and Analysis

5.3.1. Source-Side Model Experiment

In this section, we conducted comparative experiments between the Source-Side-CNN-Transformer and the baseline model. The Source-Side-CNN-Transformer integrates the output of the feature extraction layer with the output of the encoder through a multi-head attention mechanism, and then gates the fused vector with the residual-connected encoder output. The obtained vector is used as the input of the decoder’s multi-head attention mechanism and associated with the target information. The experimental results of this method are shown in Table 4, and the improved model has a 1.63% higher BLEU score than the baseline model.

Table 4.

Source-side experiment.

This experiment shows that after the fusion of vectors with local feature information is completed at the source language end, it can effectively improve the translation performance of Transformer and mitigate its weakness in extracting local feature information.

5.3.2. Target-Side Model Experiment

In this section, we conducted comparative experiments between TSCT and the baseline model. This model integrates the output of the feature extraction layer into the target end of Transformer, enabling it to learn the feature information (Table 5).

Table 5.

Target-side experiment.

The experimental results show that fusing local information with global information in the target end can improve the performance of Transformer.

5.3.3. Ablation Experiment

To prove that the Transformer integrated with convolutional neural network has a better performance, this section conducted comparative experiments between the original models proposed in Section 3 and Section 4 and the models with the convolutional neural network removed (SST and TST represent the models after removing the feature extraction layer from SSCT and TSCT, respectively). The experimental results are as shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

SSCT-ablation experiment.

Table 7.

TSCT-ablation experiment.

5.3.4. Comparison Experiment

In order to further demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach, comparative experiments were conducted on an electrical engineering dataset with our model and baseline models such as Sentence-level [24], Key Information Fusion [25], Pos Fusion [11], and Prior Knowledge [26]. The experimental conditions were kept consistent, and the results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

The BLEU values of comparison experiments.

Sentence-level: Proposed in 2019 by Kehai Chen et al., this method uses a convolutional neural network to extract sentence-level contextual information and integrates it into the Transformer model to improve translation performance.

Key Information Fusion: Proposed in 2023 by Shije Hu et al., this method utilizes a dual-encoder structure to incorporate key information from the text into the Transformer model, aiming to enhance its performance.

Pos Fusion: Proposed in 2022 by Z et al., this method first performs part-of-speech tagging on the corpus, and then integrates the part-of-speech tagging information into the Transformer model using a dual-encoder structure. A stacked decoder structure is used to associate the part-of-speech tagging information with the target information.

Prior Knowledge: Proposed in 2022 by Rui Wang et al., this method extracts prior knowledge which is then fused with the source language information in the form of matrix-vector. This enriches the semantic knowledge learned by the Transformer model. From the comparative experiment results, it can be observed that our approach achieves a better translation performance compared to other models on the electrical engineering dataset.

Compared to the baseline model, our approach shows noticeable improvements in BLEU. Additionally, our approach outperforms the other comparative models in all the metrics, indicating that it effectively utilizes contextual information and key information to enhance translation quality.

The baseline, sentence-level, and SSCT models do not integrate prior knowledge into the Transformer model, and the processing time or extraction time consumed is zero. The Key Information Fusion, Prior Knowledge, and Pos Fusion models all need to extract and process prior knowledge. The tools used and the time spent in each stage are shown in Table 9.

where represents the total time, represents the execution time, and and represent the processing time that the model needs to process or extract prior knowledge.

Table 9.

Time cost.

5.3.5. Extended Experiment

To further investigate the universality of the proposed method, the models presented in this paper were tested on publicly available general corpora, and the experimental results are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

The result of the extended experiment.

The experimental results indicate that even on general Chinese-to-English corpora, the two models proposed in this paper still exhibit a certain effectiveness. This also confirms the validity of the improvements made to the Transformer structure in this study. Integrating convolutional neural networks as the feature extraction layer into the Transformer’s structure indeed enhances the translation capability of the model. With the improved model obtaining crucial local information, it continuously learns richer semantic relationships and correct logical connections during training, leading to more accurate translation outcomes.

5.3.6. Analysis

Based on the results of the experiments in Section 5.3, we draw the following conclusions:

The results of Section 5.3.1 and Section 5.3.2show that the two new structures proposed in this paper based on Transformer significantly improve the performance compared to the baseline model, and fusing feature information with Transformer at either the source or target end can improve translation quality. As can be seen from the translation examples in Table 11 and Table 12 (These red fonts in the table are technical terms), compared to the baseline model, SSCT and TSCT translate key information in the sentence more accurately, and the translated sentences are also closer to the reference translation.

Table 11.

Translation samples (a).

Table 12.

Translation samples (b).

SSCT performs better than TSCT, and Transformer has better results in vector fusion at the source end. The reason for this result may be that Transformer loses more source language vectors when fusing vectors at the target end, causing the fused vector of and lose some semantic information, resulting in slightly lower performance for TSCT than SSCT.

The ablation experiment in Section 5.3.3 further proves that the method proposed in this paper is effective. Integrating the convolutional neural network as a feature extraction layer into Transformer can enable it to learn the feature information in the sentence and improve its translation performance.

The results of comparative experiments show that compared with the previous models, the model proposed in this paper has a better performance on datasets in the field of electrical engineering and saves a lot of time and cost than other models using prior knowledge.

The results of extended experiments prove that the method in this paper is also applicable to the general corpus, not only in the field of electrical engineering. The method proposed in this article has a certain versatility.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we improved the Transformer model by integrating the convolutional neural network as a feature extraction layer into its overall structure and obtained two new models, SSCT and TSCT, which respectively perform vector fusion of feature information at the source and target sides. This allows the improved Transformer model to learn semantic knowledge containing feature information.

SSCT introduced a multi-head attention mechanism between the feature information extraction layer and the source language encoder, which is used to fuse the feature vector and encoder output vector. The fused vector is used as the and vector in the decoder multi-head attention mechanism and is calculated with the internal vector of the encoder layer. Through this method, the model can continuously learn semantic information containing feature vectors during training, thereby enhancing the performance of the translation model. TSCT has the same feature information extraction layer as SSCT, but the decoder unit of TSCT adds a multi-head attention mechanism, which uses the output of the feature information extraction layer as the vector and the output of the first sub-layer of the decoder as the and vectors. The result of the calculation is fused with the output of the second sub-layer of the decoder, allowing the Transformer model to further learn the relationship between feature information and global information. The results of the comparative experiments and ablation experiments designed in this paper show that the BLEU values of SSCT and TSCT are 1.63 and 1.12 percentage points higher than the baseline model, respectively, which fully demonstrates the effectiveness of our proposed method.

Indeed, while the model designed in this paper exhibits an excellent performance on the English-to-Chinese dataset in the electrical engineering domain, its performance may show some decline on large-scale parallel corpora, indicating the limitations of this approach. In future work, we plan to explore the integration of bidirectional gated recurrent units (GRUs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) into both the source and target sides of the Transformer model. By doing so, the improved Transformer model will be able to learn from both memory information and local information, enhancing the overall performance and generalizability of the model. This will enable the model to achieve better results on corpora from various domains.

Author Contributions

Research conceptualization and model building: Z.L.; data collection: Z.L. and Y.C.; experiment design: Z.L., Y.C. and J.Z.; manuscript preparation: Z.L.; manuscript review: Z.L., Y.C. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Partial data are available (https://github.com/zikangliu0612/zikang). (https://opennmt.net). The access date accessed on 23 August 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, J.; Auli, M.; Grangier, D.; Yarats, D.; Dauphin, Y.N. Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–17 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Tonja, A.L.; Kolesnikova, O.; Gelbukh, A.; Sidorov, G. Low-Resource Neural Machine Translation Improvement Using Source-Side Monolingual Data. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahsuli, M.M.; Khadivi, S.; Homayounpour, M.M. LenM: Improving Low-Resource Neural Machine Translation Using Target Length Modeling. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.L.; Pham, T.V. A Data Augmentation Method for English-Vietnamese Neural Machine Translation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 28034–28044. [Google Scholar]

- Laskar, S.R.; Paul, B.; Dadure, P.; Manna, R.; Pakray, P.; Bandyopadhyay, S. English–Assamese neural machine translation using prior alignment and pre-trained language model. Comput. Speech Lang. 2023, 82, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Yun, S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, K.J. Robust Data Augmentation for Neural Machine Translation through EVALNET. Mathematics 2022, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Bisazza, A.; van Noord, G. Evaluating Pre-training Objectives for Low-Resource Translation into Morphologically Rich Languages. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 20–25 June 2022; pp. 4933–4943. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Yu, Z.; Gao, S. Enhancing low-resource neural machine translation with syntax-graph guided self-attention. Knowl. Based Syst. 2022, 246, 108615. [Google Scholar]

- Hlaing, Z.Z.; Thu, Y.K.; Supnithi, T.; Netisopakul, P. Improving neural machine translation with POS-tag features for low-resource language pairs. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannay, S.; Favre, B.; Esteve, Y.; Camelin, N. Word embedding evaluation and combination. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’16), Portorož, Slovenia, 23–28 May 2016; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, O.; Goldberg, Y. Neural word embedding as implicit matrix factorization. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wallace, B. A sensitivity analysis of (and practitioners’ guide to) convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1510.03820. [Google Scholar]

- Gulcehre, C.; Firat, O.; Xu, K.; Cho, K.; Barrault, L.; Lin, H.C.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. On using monolingual corpora in neural machine translation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.03535. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Tian, F.; Gao, F.; Qin, T.; Zhai, C.X.; Liu, T.Y. Neural machine translation with soft prototype. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Xiong, D. Encoding gated translation memory into neural machine translation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October 31–4 November 2018; pp. 3042–3047. [Google Scholar]

- Bimal, K. Modern Power Electronics and AC Drives; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bimal, K. Modern Power Electronics and AC Drive; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, H., Translators; Machinery Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Glover, J.D. Power System Analysis and Design (Adapted in English); Machinery Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, J.D. Power System Analysis and Design (Chinese Edition); Wang, Q.; Huang, W.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y., Translators; Machinery Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G.; Kim, Y.; Deng, Y.; Senellart, J.; Rush, A.M. Opennmt: Open-Source Toolkit for Neural Machine Translation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.02810. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.-J. Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Wang, R.; Utiyama, M.; Sumita, E.; Zhao, T. Neural machine translation with sentence-level topic context. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 27, 1970–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, X.; Bai, J.; Lei, H.; Qian, W.; Hu, S.; Zhang, C.; Kofi, A.S.; Qiu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Neural Machine Translation by Fusing Key Information of Text. CMC Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 74, 2803–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, R.; Utiyama, M.; Sumita, E. Integrating prior translation knowledge into neural machine translation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 30, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).