Abstract

It is common to implement challenge-response entity authentication with a MAC function. In such an entity authentication scheme, aggregate MAC is effective when a server needs to authenticate many entities. Aggregate MAC aggregates multiple tags (responses to a challenge) generated by entities into one short aggregate tag so that the entities can be authenticated simultaneously regarding only the aggregate tag. Then, all associated entities are valid if the pair of a challenge and the aggregate tag is valid. However, a drawback of this approach is that invalid entities cannot be identified when they exist. To resolve the drawback, we propose group-testing aggregate entity authentication by incorporating group testing into entity authentication using aggregate MAC. We first formalize the security requirements and present a generic construction. Then, we reduce the security of the generic construction to that of aggregate MAC and group testing. We also enhance the generic construction to instantiate a secure scheme from a simple and practical but weaker aggregate MAC scheme. Finally, we show some results on performance evaluation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

A MAC function is one of the most basic symmetric-key primitives for cryptography. Its typical application is challenge-response entity authentication, which assumes that a server and an entity share a secret key. In this scheme, the server first sends a challenge to the entity. Next, the entity computes a tag for the challenge using the MAC function with the shared secret key and returns it to the server. Finally, the server computes the tag in the same way and verifies the received tag.

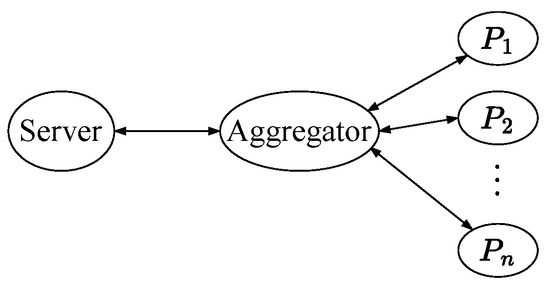

Entity authentication is often crucial in identifying invalid entities to secure network applications and services. Additionally, a server may need to authenticate many devices simultaneously in an IoT network. In scenarios where an edge device plays the role of an aggregator, as shown in Figure 1, aggregate MAC [1] is suitable for efficient communication between the server and the aggregator for entity authentication. Aggregate MAC allows users to aggregate multiple tags into a tag so that the aggregate tag is as short as each of the multiple tags. In the situation shown in Figure 1, if the aggregator aggregates tags from devices and sends the aggregate tag to the server, then the server can authenticate the devices based only on the aggregate tag. If the aggregate tag is valid, then the server knows that all devices are valid. On the other hand, if the aggregate tag is invalid, then the server only knows that one or more invalid devices are included, which cannot be identified. The problem is if the server can identify invalid devices without knowing individual tags. As far as we know, it has not been addressed for entity authentication.

Figure 1.

Targeted system configuration.

1.2. Our Contribution

We observe that group testing [2] can be employed to solve the above problem. For group testing, each item is assumed to be positive or negative. Multiple items are assumed to be able to be inspected by a test whose result is positive only if one or more positive items are included. All positive items can be identified with fewer tests than individual tests if the number of positive items is relatively small [3].

We introduce and explore group-testing aggregate authentication. It is a protocol participated in by multiple entities, an aggregator, and a server. Each entity has its own secret key shared with the server. The aggregator broadcasts a challenge from the server to the entities and collects their responses. The server then identifies the invalid entities by verifying the responses with the help of the aggregator.

We first formalizesd the scheme and its security requirements. The security requirements are impersonation resistance, completeness, and soundness. Impersonation resistance represents the notion that adversaries cannot impersonate an entity without knowing its secret key. Completeness requires that a valid response must not be judged invalid. Soundness requires that an invalid response must not be judged valid.

Furthermore, we present a generic construction combining a group-testing scheme and an aggregate MAC scheme. For each test in group testing, it aggregates the tags of entities examined by the test and verifies the aggregate tag. The aggregate tag is valid (negative) if all the involved tags are valid. Thus, invalid entities can be identified with fewer tests than by examining them individually. We also show that the generic construction satisfies impersonation resistance if the underlying aggregate MAC scheme is unforgeable, completeness if the underlying group-testing scheme satisfies completeness, and soundness if the underlying aggregate MAC scheme satisfies soundness. Furthermore, considering that the simple and practical Katz-Lindell aggregate MAC scheme [1] does not satisfy soundness, we enhance the generic construction to instantiate group-testing aggregate entity authentication satisfying soundness by using aggregate MAC not satisfying soundness.

Finally, we evaluate the performance of the proposed construction instantiated with SHA-256 [4] and HMAC [5] by software implementation.

1.3. Related Work

Katz and Lindell [1] introduced and investigated aggregate MAC. They presented a provably secure scheme for generating an aggregate tag by XOR of the associated tags. Eikemeier et al. [6] formalized sequential aggregate MAC and presented provably secure schemes. Sato et al. [7] proposed a sequential aggregate MAC scheme for aggregating tags without using the secret keys of associated users. Ishii and Tada [8] presented an aggregate MAC scheme that aggregates tags following the structure represented by a series-parallel graph.

Goodrich et al. [9] applied group testing to MAC schemes for identifying tampered data items. Along this line of research, Minematsu [10] proposed a computationally efficient scheme of group testing MAC based on PMAC [11]. Minematsu and Kamiya [12] proposed a method for reducing the number of tags.

Hirose and Shikata [13,14] applied group testing to aggregate MAC for identifying invalid messages from multiple senders. They used non-adaptive group testing for a generic construction. Sato and Shikata [15] presented a generic construction using adaptive group testing. Anada and Kamibayashi [16] followed the discussion by Sato and Shikata [17] and discussed the quantum security of aggregate MAC combined with non-adaptive group-testing. Ogawa et al. [18] presented a scheme reducing the number of aggregate tags based on biorthogonal codes.

1.4. Organization

Section 2 defines notations and cryptographic primitives and describes group testing. Section 3 provides the syntax and security requirements of aggregate MAC and its concrete schemes. Section 4 formalizes group-testing aggregate entity authentication and presents its generic construction, combining group-testing and aggregate MAC. Section 5 discusses the security of the generic construction and presents its enhancement. Section 6 shows some results of the performance evaluation by software implementation. Section 7 gives a brief concluding remark.

This article is an extended and improved version of our conference paper [19]. We refine the formalization of security requirements, which are described in Section 4, based on the idea by Bellare and Rogaway [20]. Accordingly, we revise the theorems and proofs, which are given in Section 5. We also add the results on performance evaluation.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Notation

is regarded as the set of all binary sequences of length l. Let . For binary sequences , their concatenation is denoted by .

Let be a set. For and , let , where and iff . For , let be their component-wise disjunction. Let represent that s is sampled uniformly at random from .

2.2. MAC Function and Pseudorandom Function

Let be a keyed function with its key space . is often denoted by .

f is called a secure MAC function or unforgeable if it is intractable to predict unknown outputs of , where . An adversary is given a tagging oracle and a verification oracle and is allowed to make queries adaptively to them. In response to a query , returns . In response to a query , returns 1 if and 0 otherwise. is not allowed to ask to after asking X to . is successful iff returns 1 in response to at least one query. The advantage of against f is

f is called a secure pseudorandom function (PRF) if it is intractable to distinguish with from a uniform random function . An adversary is given either or as an oracle and is allowed to make adaptive queries in . outputs 0 or 1. The advantage of against f is

where is regarded as a random variable which takes values in . It is easy to see that a secure PRF is a secure MAC function, and that a secure MAC function is not necessarily a secure PRF.

2.3. Cryptographic Hash Function

A cryptographic hash function is often simply called a hash function. Among its various security requirements, our work is concerned with the random oracle model and collision resistance.

The random oracle model [21] assumes that H is an ideal function such that, for any , is chosen uniformly at random from . H is called a random oracle.

H is said to satisfy collision resistance if it is intractable to find a pair of distinct inputs of H mapped to the same output. The advantage of an adversary against H is

Notice that the above definition is not theoretically precise: H should be sampled from a sufficiently large number of hash functions at random.

2.4. Group Testing

Suppose that there exists a set of items, each of which is either positive or negative. It is assumed that a test can inspect multiple items simultaneously and that the result is positive iff one or more positive items exist among them. Then, it may be possible to identify positive items with fewer tests than by inspecting all the items individually.

A group-testing algorithm can be described as a sequence of sets of tests. Suppose that there are n items. Then, each test can be denoted by a vector in such that the j-th element equals 1 iff the test examines the j-th item. Let be a sequence of sets of tests, where u is the number of its stages. The sets of tests are conducted in this order, and the order of the tests in each stage is arbitrary. A group-testing algorithm is called non-adaptive if all the tests are determined beforehand. Thus, it has only a single stage. A group-testing algorithm is called adaptive if the tests in the next stage are determined after the tests in the current stage.

Let . It is reasonable to assume that each test examines at least one item and that the whole set of tests examines all items. Namely, and . The group-testing algorithm extracts candidates of positive items in the following way. For , let denote the j-th item. For , let . Let , where .

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- For , do the followings: (a) ; (b) For , if the result of is negative, then .

- (3)

- Output .

We call the group-testing algorithm complete if does not include any negative elements. We call it sound if includes all the positive elements. It is sound if the results of the tests are always correct. On the other hand, it may not be complete in general.

For non-adaptive group testing, let us see the matrix whose rows are the vectors in a set of tests, which is called a group-testing matrix. We call d-disjunct if the component-wise disjunction of any d columns in does not equal the component-wise disjunction of itself and any other single column. Suppose that non-adaptive group testing is represented by a d-disjunct matrix. Then, it is complete if there are at most d positive items. Specifically, all the positive items are identified.

Suppose that there are at most d positive items. For non-adaptive group testing, it is known that there exists a complete algorithm with tests [3,22,23,24]. In addition, a non-asymptotic lower bound was conjectured as [25] while it is true for , and actually derived as [26] and [27]. For adaptive group testing, it is known that there exists a complete algorithm with tests [3,28,29]. A tight lower bound is shown as [3].

3. Aggregate MAC

3.1. Syntax

A tuple of algorithms formalizes an aggregate MAC scheme. It is associated with an ID space , a key space , a message space , a tag space , and an aggregate-tag space .

- is a key-generation algorithm such that , where is a security parameter and . Each entity is assigned a secret key independently generated by .

- is a tagging algorithm such that , where and .

- is an aggregate algorithm such that where for and . ’s are required to be distinct from each other. It is often the case that T depends only on .

- is a verification algorithm such that , where and for , if and otherwise, and . ’s are required to be distinct from each other. With respect to , the pair and T are valid if and invalid otherwise.

satisfies correctness. For and , let for and . Then, it holds that In particular, for , if , then .

3.2. Security Requirement

Unforgeability and soundness are formalized as security requirements for aggregate MAC. Soundness is required for applying group testing to aggregate MAC [14].

3.2.1. Unforgeability

We introduce a game to define unforgeability, where is an adversary allowed to make queries adaptively to the oracles , , and .

- is called a tagging oracle. It returns in response to a query , where is the key of the entity .

- is called a key-disclosure oracle. It accepts a query and returns .

- is called a verification oracle. It accepts a query and returns

For a query made by to , we call a fresh pair if does not ask it to and does not ask to prior to the query. does not accept a query with no fresh pair. outputs 1 iff gets 1 from for at least one query. The advantage of against for unforgeability is defined by

It is informally stated that is unforgeable or satisfies unforgeability if, for any efficient , is negligible.

3.2.2. Soundness

To define soundness, we specify a game , where is an adversary allowed to make queries adaptively to the aggregate-then-verify oracle in addition to the oracles , , and . accepts a query and computes

- for ,

- , and

- .

Then, it returns . outputs 1 iff gets 1 from for at least one query. The advantage of against for soundness is defined by

It is informally stated that is sound or satisfies soundness if, for any efficient , is negligible.

3.3. Aggregate MAC Scheme by Katz and Lindell

Let be a MAC function. The Katz-Lindell aggregate MAC scheme [1] using F is specified as follows:

- Each entity is given a secret key .

- The tagging algorithm returns a tag in response to .

- The aggregate algorithm returns an aggregate tag in response to .

- Taking and as input, the verification algorithm outputs 1 iff .

Let denote the Katz-Lindell aggregate MAC scheme. is shown to be unforgeable for any efficient adversary asking the verification oracle a single query [1]. It is also shown to be unforgeable even for any efficient adversary asking the verification oracle multiple queries:

Proposition 1

([14]). Let be any adversary against with ℓ users. Suppose that asks the tagging oracle queries and the verification oracle queries. Suppose that each verification query by consists of at most p pairs of ID and message. Then, there exists some adversary satisfying

asks the tagging oracle at most queries and the verification oracle at most one query. ’s running time is at most about that of .

It is easy to see that is not sound. Let be an adversary working as follows. first asks and to the tagging oracle and gets and . Then, gets 1 from the aggregate-then-verify oracle by asking such that and .

3.4. Aggregate MAC Scheme Using Hashing

We refer to the aggregate MAC scheme using a hash function to aggregate tags [14] as . is specified as follows:

- The key generation and tagging algorithms are identical to those of .

- For , the aggregate algorithm returns . For the uniqueness of the aggregate tag T, are assumed to be ordered in a lexicographic order.

- Taking and as input, the verification algorithm outputs 1 if and 0 otherwise.

is shown to be unforgeable if F is unforgeable and H is a random oracle [14]:

Proposition 2.

Let be any adversary against with ℓ users. Suppose that asks the random oracle H queries, the tagging oracle queries, and the verification oracle queries. Suppose that each verification query by consists of at most p pairs of ID and message. Then, there exists some adversary satisfying

asks the random oracle at most queries, the tagging oracle at most queries, and the verification oracle at most one query. ’s running time is at most about that of .

The soundness of is reduced to the collision resistance of H [14]:

Proposition 3.

For any adversary against concerning soundness, there exists some adversary satisfying

The running time of is at most about that of .

4. Group-Testing Aggregate Entity Authentication

4.1. Scheme

We present a group-testing aggregate entity authentication scheme. It is a challenge-response protocol between a server and a set of entities, and they communicate through an aggregator (Figure 1). It consists of a group-testing algorithm and an aggregate MAC scheme and is denoted by .

Let denote the set of entities. Each has an ID and shares a secret key with the server. proceeds as follows:

- Step 1:

- The server sends a challenge to the aggregator, which broadcasts it to the entities.

- Step 2:

- In response to c, each entity returns to the aggregator, where .

- Step 3:

- The aggregator sends to the server.

- Step 4:

- With the help of the aggregator, the server identifies the valid entities using , , and in the following way:

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- Let u be the number of stages of . For ,

- (a)

- According to , both the server and the aggregator determine the set of tests .

- (b)

- The aggregator computes for and sends to the server.

- (c)

- The server first sets . Then, for , it computesand if . Finally, it sends to the aggregator.

- 3.

- Output .

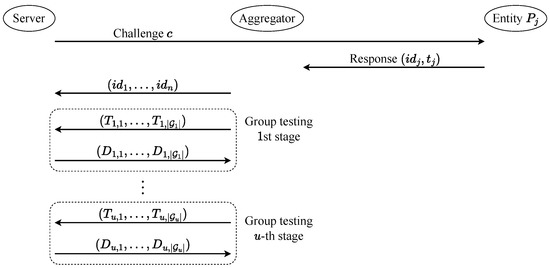

The communication among the server, the aggregator, and the entities in is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The communication among the server, the aggregator, and the entities in .

For the description above, Step 3 can be merged with the first move of 2(b) in Step 4 if the server knows the number of entities to be authenticated in advance. If is non-adaptive, then , and both the server and the aggregator know all the tests in advance. In addition, the server does not have to send the results of the tests to the aggregator in Step 4(c). If is adaptive, then the results of determine . Since the server sends the results of the current tests to the aggregator, the aggregator can also determine the new set of tests.

4.2. Security Requirement

The security requirements of are impersonation resistance, completeness, and soundness.

4.2.1. Impersonation Resistance

We introduce a game to formalize impersonation resistance. In this game, the adversary is supplied with oracles working as the server. For the i-th run of , triggers , which starts the protocol by returning a challenge to . is also supplied with oracles working as entities.

The i-th run of proceeds with the communication between and . Multiple runs may proceed concurrently in general. Each accepts two kinds of queries. For a tagging query , returns . For a corrupt query , it returns . Once gets , is allowed to ask it only to . At the end of the run, outputs the set of IDs of invalid entities. may abort the run if does not follow the protocol.

outputs 1 iff there exist some and such that , does not ask to , and does not ask to for any i. The advantage of against for impersonation resistance is

4.2.2. Completeness and Soundness

Completeness and soundness are security requirements for the identifiability of (in)valid responses to a challenge. We introduce games and . In both games, the adversary is not allowed to corrupt the server and the aggregator, and the communication channel between them is authenticated. Notice that, if is allowed to tamper aggregate tags, then any valid response by an entity can be judged invalid by the server.

In both of the games, the adversary is supplied with oracles playing the roles of the server and the aggregator. is also supplied with oracles working as entities, which are specified in Section 4.2.1. For the i-th run of , triggers , which starts the protocol by returning a challenge to . Once gets , is allowed to ask it only to . In response to , returns to . runs the protocol step by step. Each step is triggered by . can also see the messages communicated during the protocol. At the end of the run, outputs the set of IDs of invalid entities. Multiple runs may proceed concurrently in general.

outputs 1 iff there exists some such that

outputs 1 iff there exists some such that

The advantage of for completeness and soundness of is

respectively.

Remark 1.

The unforgeability of the tagging algorithm is irrelevant to soundness. This is because, for soundness, is allowed to ask and to for any i and j. If the tagging algorithm is unforgeable and is not allowed to ask them to , then it cannot return a valid tag to . Thus, impersonation resistance can be regarded as weak soundness in that

All in all, impersonation resistance is sufficient to identify invalid entities. Soundness is required to achieve the same function as individual verification of each response, that is, to identify invalid responses.

5. Discussion on Security

5.1. Impersonation Resistance

The impersonation resistance of is reduced to the unforgeability of :

Theorem 1.

For any adversary against for impersonation resistance, triggering at most runs of and making at most tagging queries and corrupt queries, there exists some adversary satisfying

The number of queries made by to is at most . The number of queries made by to is at most . The number of queries made by to is at most the total number of tests completed by ’s in . The running time of is at most about that of .

Proof.

In , runs . If makes a tagging query to , then asks to and gets , which is returned to . If makes a corrupt query to , then asks to and gets , which is returned to . simulates by making use of .

Suppose that outputs 1. Then, there are two cases:

- There exists some such that the challenge of the -th run of collides with some previous challenge () or c in a previous tagging query.

- There exists some and such that, for some test with during the -th run of , , and does not ask to and to any .

For the first case, notice that triggers at most runs of and makes at most tagging queries. Thus, the probability of the first case is at most

For the second case, gets 1 from in response to the query , and is a fresh pair. Thus, outputs 1. □

5.2. Completeness and Soundness

It is easy to see that the completeness of is reduced to the completeness of since satisfies correctness:

Theorem 2.

If satisfies completeness, then, for any adversary against ,

Proof.

Since satisfies completeness, for any valid tag, there exists some test such that it examines the tag and all the other tags it examines are valid. Since satisfies correctness, any aggregate tag generated only from valid tags is judged valid. □

The soundness of is reduced to the soundness of :

Theorem 3.

For any adversary against for soundness, triggering at most runs of and making at most tagging queries and corrupt queries, there exists some adversary satisfying

The number of queries made by to is at most . The number of queries made by to is at most . The number of queries made by to is at most the total number of tests during the runs of . The number of queries made by to is also at most the total number of tests during the runs of . The running time of is at most about that of .

Proof.

In , runs in the similar way described in the proof of Theorem 1. simulates by making use of . Suppose that returns to in response to the challenge . Then, for each test during the i-th run of , also makes a query to .

Suppose that outputs 1 in . Then, there exists some and such that . Thus, during the -th run of , there exists some test with such that and , where . Thus, gets 1 from in response to . □

5.3. Enhancing the Generic Construction

From the results so far, we confirm that and satisfy impersonation resistance and satisfy completeness if satisfies completeness. On the other hand, does not satisfy soundness, while satisfies soundness. We enhance the proposed scheme and present , which achieves soundness even with .

is equipped with a PRF , where is its key space. A shared secret key is given to the server and the aggregator. Notice that, for soundness, the communication channel between the server and the aggregator is assumed to be authenticated. Thus, the assumption is not critical that the server and the aggregator share a secret key. is specified as follows:

- Steps 1 to 3:

- Identical to those of .

- Step 4:

- for .

- Step 5:

- Identical to Step 4 of .

The sole difference between and is that the former utilizes R to randomize the tags from the entities. Thus, Theorems 1 and 2 hold for as well as for . In addition, satisfies soundness if R is a secure PRF:

Theorem 4.

Let be any adversary against for soundness. Suppose that triggers at most runs of and makes at most tagging queries. Suppose that the runs of conduct at most tests in total and R is called at most times in total. Then, there exists some adversary such that

makes at most queries to its oracle, and its running time is at most about that of .

Proof.

Let be identical to except that the former uses chosen uniformly at random instead of with . The adversary against R is given access to either or . runs or with the use of or , respectively. outputs 1 iff is successful for soundness. Then,

since

For , let be the event that there exists a collision among the challenges generated in the runs of . Then,

Since triggers at most runs of ,

Finally, let us see that

Let be the challenge in the i-th run of and . If does not occur, then is chosen uniformly at random. Thus, the probability that the result of a test involving such that happens to be valid is at most . □

6. Performance Evaluation

We implemented the verification algorithms of group-testing aggregate entity authentication for , , and . We used the MAC function HMAC-SHA-256 for tagging and SHA-256 to aggregate tags for . For , we adopted non-adaptive group testing and used d-disjunct matrices generated by the shifted transversal design (STD) [30], where d is the upper bound on the number of invalid entities.

We implemented the algorithms in Python 3.10.9 and utilized the modules hmac and hashlib for SHA-256 and HMAC-SHA-256. We evaluated the performance of our implementations on a MacBook Pro with Apple M1, 16 GB of memory, and macOS Ventura 13.3.1.

The results are summarized in Table 1. For the numbers of the entities 100, 1000, and 10,000, the sizes of the matrices are , , and 10,000, respectively. They are 5-, 17-, and 68-disjunct matrices, respectively.

Table 1.

Runtime (milliseconds).

Each time presented in Table 1 is the smallest of ten measurements. The “Tagging” column shows the time required to generate all the tags for the entities. Thus, they almost equal the time to verify all the tags of the entities one by one. For the same number of entities, there is no significant difference in the times required for verification by , , and . They depend on the numbers of 1’s in the group-testing matrices, which are 600, 18,000, and 690,000 for 100, 1000, and 10,000 entities, respectively.

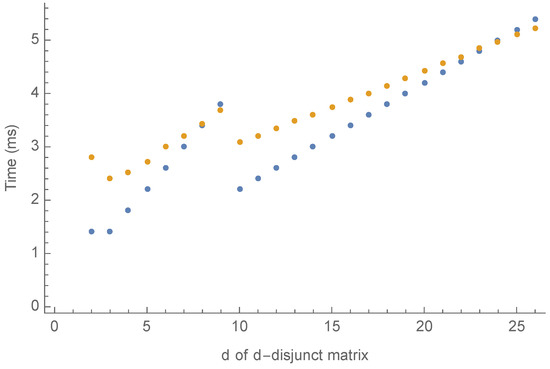

Figure 3 presents more details on the runtime for verification of with 1000 entities and . Table 2 presents the number of rows and the number of 1’s in the group-testing matrices used for the experiments. If , then cannot reduce the amount of communication between the server and the aggregator.

Figure 3.

Runtime for verification of with 1000 entities.

Table 2.

The number of rows and the number of 1’s of d-disjunct matrices used for the experiments on Figure 3.

In Figure 3, the orange dots represent the times. For reference, we also give the blue dots representing the values of . As shown in Table 2, for group-testing matrices based on STD, the number of rows increases with the value of d. On the other hand, this is not necessarily the case for the number of 1’s.

7. Concluding Remark

We have introduced and explored group-testing aggregate authentication. We have first formalized the scheme and security requirements. Then, we have presented a general construction utilizing a group-testing scheme and an aggregate MAC scheme. We have reduced the security properties of the generic construction and its enhancement to those of the underlying group testing and aggregate MAC. Finally, we have shown results on the performance evaluation of the proposed construction instantiated with SHA-256 and HMAC.

The proposed construction can easily be deployed due to its simplicity. In addition, any progress in group testing and aggregate MAC will benefit it. Future work is to improve the performance further. It is interesting to see if the idea of Minematsu and Kamiya [12] is effective for our proposed construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and J.S.; methodology, S.H. and J.S.; software, S.H.; validation, S.H. and J.S.; formal analysis, S.H. and J.S.; investigation, S.H. and J.S.; resources, S.H.; data curation, S.H. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H. and J.S.; visualization, S.H.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, J.S.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

These research results were obtained from the commissioned research (No.03901) by National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT), Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kazuhiko Minematsu for providing us disjunct matrices generated by using the STD method.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAC | Message authentication code |

| IoT | Internet of things |

| XOR | Exclusive or |

| PRF | Pseudorandom function |

| STD | Shifted transversal design |

References

- Katz, J.; Lindell, A.Y. Aggregate Message Authentication Codes. In Proceedings of the Topics in Cryptology—CT-RSA 2008, The Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference 2008, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–11 April 2008; Malkin, T., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 4964, pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, R. The Detection of Defective Members of Large Populations. Ann. Math. Stat. 1943, 14, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.Z.; Hwang, F.K. Combinatorial Group Testing and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; Series on Applied Mathematics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2000; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- FIPS PUB 180-4; Secure Hash Standard (SHS). National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015.

- FIPS PUB 198-1; The Keyed-Hash Message Authentication Code (HMAC). National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2008.

- Eikemeier, O.; Fischlin, M.; Götzmann, J.; Lehmann, A.; Schröder, D.; Schröder, P.; Wagner, D. History-Free Aggregate Message Authentication Codes. In Proceedings of the Security and Cryptography for Networks, 7th International Conference, SCN 2010, Amalfi, Italy, 13–15 September 2010; Garay, J.A., Prisco, R.D., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6280, pp. 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Hirose, S.; Shikata, J. Sequential Aggregate MACs from Any MACs: Aggregation and Detecting Functionality. J. Internet Serv. Inf. Secur. 2019, 9, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Tada, M. Structurally aggregate message authentication codes. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Information Theory and Its Applications, ISITA 2020, Kapolei, HI, USA, 24–27 October 2020; pp. 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, M.T.; Atallah, M.J.; Tamassia, R. Indexing Information for Data Forensics. In Proceedings of the Applied Cryptography and Network Security, Third International Conference, ACNS 2005, New York, NY, USA, 7–10 June 2005; Ioannidis, J., Keromytis, A.D., Yung, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3531, pp. 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minematsu, K. Efficient Message Authentication Codes with Combinatorial Group Testing. In Proceedings of the Computer Security—ESORICS 2015—20th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Vienna, Austria, 21–25 September 2015; Proceedings, Part I. Pernul, G., Ryan, P.Y.A., Weippl, E.R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 9326, pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Rogaway, P. A Block-Cipher Mode of Operation for Parallelizable Message Authentication. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2002, International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28 April–2 May 2002; Knudsen, L.R., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2332, pp. 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minematsu, K.; Kamiya, N. Symmetric-Key Corruption Detection: When XOR-MACs Meet Combinatorial Group Testing. In Proceedings of the Computer Security—ESORICS 2019—24th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Luxembourg, 23–27 September 2019; Proceedings, Part I. Sako, K., Schneider, S., Ryan, P.Y.A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11735, pp. 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S.; Shikata, J. Non-adaptive Group-Testing Aggregate MAC Scheme. In Proceedings of the Information Security Practice and Experience—14th International Conference, ISPEC 2018, Tokyo, Japan, 25–27 September 2018; Su, C., Kikuchi, H., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11125, pp. 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S.; Shikata, J. Aggregate Message Authentication Code Capable of Non-Adaptive Group-Testing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 216116–216126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Shikata, J. Interactive Aggregate Message Authentication Scheme with Detecting Functionality. In Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, AINA 2019, Matsue, Japan, 27–29 March 2019; Barolli, L., Takizawa, M., Xhafa, F., Enokido, T., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 926, pp. 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anada, H.; Kamibayashi, D. Quantum Security and Implementation Evaluation of Non-adaptive Group-Testing Aggregate Message Authentication Codes. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Computing and Networking Workshops, CANDAR 2020 Workshops, Naha, Japan, 24–27 November 2020; pp. 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Shikata, J. Quantum-Secure (Non-)Sequential Aggregate Message Authentication Codes. In Proceedings of the Cryptography and Coding—17th IMA International Conference, IMACC 2019, Oxford, UK, 16–18 December 2019; Albrecht, M., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11929, pp. 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Sato, S.; Shikata, J.; Imai, H. Aggregate Message Authentication Codes with Detecting Functionality from Biorthogonal Codes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, ISIT 2020, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 21–26 June 2020; pp. 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S.; Shikata, J. Group-Testing Aggregate Entity Authentication. In Proceedings of the IEEE Information Theory Workshop, ITW 2023, Saint-Malo, France, 23–24 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bellare, M.; Rogaway, P. Entity Authentication and Key Distribution. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO ’93, 13th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 22–26 August 1993; Stinson, D.R., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; Volume 773, pp. 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellare, M.; Rogaway, P. Random Oracles are Practical: A Paradigm for Designing Efficient Protocols. In Proceedings of the CCS ’93, Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Fairfax, VA, USA, 3–5 November 1993; Denning, D.E., Pyle, R., Ganesan, R., Sandhu, R.S., Ashby, V., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dýachkov, A.G.; Rashad, A.M.; Rykov, V.V. Superimposed distance codes. Probl. Control Inf. Theory 1989, 18, 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Porat, E.; Rothschild, A. Explicit Non-adaptive Combinatorial Group Testing Schemes. In Proceedings of the Automata, Languages and Programming, 35th International Colloquium, ICALP 2008, Reykjavik, Iceland, 7–11 July 2008; Proceedings, Part I: Tack A: Algorithms, Automata, Complexity, and Games. Aceto, L., Damgård, I., Goldberg, L.A., Halldórsson, M.M., Ingólfsdóttir, A., Walukiewicz, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5125, pp. 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, M.; Johnson, O.; Scarlett, J. Group Testing: An Information Theory Perspective. Found. Trends Commun. Inf. Theory 2019, 15, 196–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdös, P.; Frankl, P.; Füredi, Z. Families of Finite Sets in Which No Set Is Covered by the Union of r Others. Isr. J. Math. 1985, 51, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dýachkov, A.G.; Rykov, V.V. Bounds on the Length of Disjunctive Codes. Probl. Inf. Transm. 1982, 18, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan, C.; Ge, G. New Bounds on the Number of Tests for Disjunct Matrices. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2016, 62, 7518–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H. A Sequential Method for Screening Experimental Variables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1962, 57, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppstein, D.; Goodrich, M.T.; Hirschberg, D.S. Improved Combinatorial Group Testing Algorithms for Real-World Problem Sizes. SIAM J. Comput. 2007, 36, 1360–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry-Mieg, N. A new pooling strategy for high-throughput screening: The Shifted Transversal Design. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).