Abstract

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) also known as drones have created many challenges to the digital forensic field. These challenges are introduced in all processes of the digital forensic investigation (i.e., identification, preservation, examination, documentation, and reporting). From identification of evidence to reporting, there are several challenges caused by the data type, source of evidence, and multiple components that operate UAVs. In this paper, we comprehensively reviewed the current UAV forensic investigative techniques from several perspectives. Moreover, the contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) discovery of personal identifiable information, (2) test and evaluation of currently available forensic software tools, (3) discussion on data storage mechanism and evidence structure in two DJI UAV models (e.g., Phantom 4 and Matrice 210), and (4) exploration of flight trajectories recovered from UAVs using a three-dimensional (3D) visualization software. The aforementioned contributions aim to aid digital investigators to encounter challenges posed by UAVs. In addition, we apply our testing, evaluation, and analysis on the two selected models including DJI Matrice 210, which have not been presented in previous works.

1. Introduction

The use of flying Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) has increased over the past five years among hobbyists, photographers, and journalists. The number of licensed pilots in the USA has tremendously increased to 212 thousand of certified remote pilots [1]. However, the accessibility of such technology has created a series of challenges to the digital forensics field. As most of the world faces issues related to the forensic investigation of UAVs, the INTERPOL recently has collaborated with communities, researchers, and practitioners by developing a drone incident response framework that could aid in the investigation of such flying devices by addressing the challenges that are faced by drone forensic examiners [2]. It is crucial to classify artifacts recovered from UAVs to enhance the performance of drone incident investigations and response. The Computer Forensic Reference Data Sets (CFReDS) provides access to acquired drone images including—remote controls, mobile devices, chip-offs, internal and external SD cards from a wide range of UAV models [3]. Challenges to the UAV ecosystem include cyber threats that could impact the reliability of the investigated digital evidence.

Therefore, in this paper, we focus on examining two types of flying devices to build up on the existing knowledge in this area. Moreover, we consider the integrity of any acquired, analyzed, and interpreted digital evidence recovered from the selected UAVs. This paper provides an extensive analysis and evaluation of the two models because they have been involved in criminal and terrorist activities since 2018. To the best of our knowledge, the DJI Matrice 210 has not been forensically analyzed and our approach is to compare these two models from perspectives such as forensic tool performance, tractability of digital evidence, and technical challenges.

Contributions of the Paper

In this paper, we address forensic challenges related to the investigations of drones. The contributions of this research are:

- A comparison of varied drone forensic analysis.

- Address varied forensics tools capabilities related to the reliability, integrity, and recoverability of digital evidence.

- Explore digital evidence structure recovered from the two selected UAV models.

- Apply a three-dimensional (3D) visualization technique on the recovered flight trajectories for interpretation purposes.

This paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we discuss related work in drone forensics. Section 3 explores the methodology used in this research. Section 4 presents our analysis and findings. Section 5 discusses the summary of the findings of our research, and lastly, we conclude our paper with directions of future research in Section 6.

2. Related Work

Some of the early work in the area of drone forensics has proposed a Drone Open Source Parser (DROP) as a tool that is specifically dedicated to the forensic analysis of the DJI Phantom 3 [4]. The researchers examined the decryption of digital evidence (e.g., flight logs) that are essential to drone investigation. Additionally, another study [5], discussed the link between digital evidence recovered from drones and mobile devices when used as a remote control. Moreover, the authors claimed that a high rate of drone incidents are attributed to the increased usage of flying devices. In later studies, researchers conducted a comparative analysis of three devices: the drone, mobile device, and internal memory of the drone. The analysis showed that the drone body held no valuable evidence to the potential interest of investigators. On the contrary, a separate study examined a drone chip, internal memory, and controller, and found that the correlation between these three components held justifiable and reliable digital evidence [6].

Flying devices operate and function using different communication protocols through preprogrammed sensors and manual tasks. From a digital forensic perspective, the drone vital signs in-flight are invaluable to any investigation, and that is due to artifacts being typically stored in the drone chip. Conducting a forensic analysis on a drone chip provides a greater understanding and assurance of the incident due to the device’s stored system events and software-related data. In knowing this, numerous researchers have proposed a technical forensic investigation process based on such validated and verified approaches. In a recent study, the importance of ‘lessons learned’ in the drone incident response cycle and challenges related to anti-forensic techniques have been presented [7]. Supplementing the previous researcher’s findings, work presented in [8] proposed a drone forensic framework by examining five commercial drones to aid in the digital forensic identification phase. The researchers discussed the procedures used to recognize customization in drones, whereas [7] explored the currently-available customization techniques that could be used during drone crime.

Researchers in [9] cited the pivotal artifacts in drone forensic investigation as the classification of drones, fingerprints, volatile data, and the utilization of the live acquisition technique; while [10] conducted drone forensic investigation on DJI Phantom 3, and explained the importance of particular automation techniques to parse drone data. However, parsing and recovering drone data does pose challenges due to software development and the varied system architectures. In an interesting article [11], the experimentation of incorporating open source tools in drone forensics was conducted on the Parrot AR, Drone 2.0, and DJI Phantom 3. The experiment led to the discovery of recovered artifacts from both drones and mobile devices during operation. The authors illustrated a 46% reduction of drone data tampering during real-life scenario operations. The results indicated that different technologies, such as block-chain and self-adaptive forensics, enhance drone data security through time intervals, distance, and boundary techniques. Contrastingly, the security of drone live-stream data runs the risk of being tampered with.

Clark et al. [4] have made a great contribution to the analysis and interpretation of flight logs extracted from DJI drones. They developed an open-source parser to decode encrypted flight logs and convert them from .DAT to .TXT format. Visualizing extracted and recovered flight logs is an important process for digital forensic examiners to aid in geographically representing the flight trajectory. Although the study focused on information related to the drone and GPS data and pointed out some interesting facts regarding the owner of the drone, they have left behind many files that are stored inside the application that could have supposedly helped in discovering more information regarding the owner of the drone and their activities. These artifacts and system logs might contain valuable network records that ease the investigation process.

Researchers in [12], have demonstrated the usefulness of using multiple sources of information to geographically distinguish important locations and approximately locate the user from network artifacts, such as IP addresses, which are retrieved from a handful of mobile applications (apps). An Experiment in [9] considered simulating a drone in a crime scene scenario while using a mobile device as a controller. The researchers found an association between the drone components in regard to timestamp and GPS data from the recovered artifacts. Alternatively, researchers in [10] presented an investigative framework considering the ‘identification’ phase of digital forensics, suggesting that the drone forensic field is challenged by validated tools and the interpretation of recovered data in a readable format. Some flying devices are controlled with smartphones and mobile apps such as the Parrot Bebop. This requires forensic analysis of cloud and mobile storage to recover captured media and/or flight logs. However, the absence of some components of the drone (e.g., drone body) might reveal some challenges related to the identification of the owner, especially if it is abandoned at the crime scene [13]. This work concentrates on forensically sound approaches to identify the device owner considering several case scenarios missing some drone components (e.g., remote control).

Moreover, other researchers demonstrated a technical investigative framework specifically for drones considering anti-forensic and validation challenges [6]. The technical framework consists of ten important phases that illustrate processes during the analysis and validation phases. In addition, a framework has been presented in [8] that elaborates on crime scene investigation.

A recent study [14] developed a threat assessment model to enhance the security of flying devices through the consideration of three layers of data flow. Moreover, researchers emphasized the importance of amending the firmware update mechanism to cope with the advancement in technology. Due to the rapidly increasing adoption of drones, researchers discussed potential security threats including GPS spoofing, maldrone, and unencrypted data transmission. The authors presented a maldroning proof-of-concept (POC) by gaining control of another flying device by dropping malware over the air to take control of it. Through the demonstrated POC, the authors exhibited how crucial it is to secure proper safety measures when operating a drone. These flying devices are being utilized for numerous critical operations, such as crime scene mapping, policing, and medical transportation. Data tampering is an additional example that could potentially impact the usage of drones. Researchers [7,15,16] stated issues related to information disclosure through the initiation of an eavesdropping attack; whereas, researchers in [17] presented a Denial of Service (DoS) on an AR.drone 2.0 that demonstrated the malfunctioning of live transmitted data. Throughout our research, we will concentrate on the security of transmitted data by evaluating the data that is generated during drone operation. To speculate, we concentrate on the data integrity making sure that the recovered data is reliable with proper security measures (e.g., data encryption and secure transmission).

3. Methodology

The selected research methodology in this paper aims to comprehensively evaluate the capabilities of forensic software tools (both open-source and proprietary), demonstrate the analysis of recovered artifacts, and discuss the integrity and reliability of recovered digital evidence. Table 1 illustrates all selected tools to conduct our analysis including—forensic examination, data comparison, entropy measurement, and data visualization. Some of these tools (e.g., Cellebrite) gained popularity among law enforcement agencies (LEAs) and the digital forensics community. These tools help us in evaluating the selected UAV models and highlight the differences between them. In addition, we consider the integrity of any recovered digital evidence from the two drones to make sure that our analysis and selected tools meet the minimum investigation requirements. These requirements include a range of standards and are out of the scope of this research; however, we analyze the file checksum values before and after running any additional needed software tools. This will help us in avoiding the implications pertaining to the integrity of these recovered files. Note that, conducting a UAV forensic analysis might not consist of all UAV components (remote control, body of the drone, SD cards, etc.) in a crime scene. For instance, conducting the analysis of the drone body (e.g., external SD card) only might not reveal all associated digital evidence.

Table 1.

A set of tools used to conduct our analysis.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no forensic examination on DJI Matrice 210. UAVs consist of several components (external and internal SD cards, memory chips, remote control, sensors, actuators, etc.) that are important for digital investigation. In our work, we use publicly available drone images provided by the VTO labs [3]. The available drone forensic images contain different forensic acquisition processes [18]. For instance, chip-off forensic, internal and external memory acquisition, and mobile forensic images. We conducted the forensic analysis on internal and external memory cards—including components such as camera, controller, memory storage, and chip off acquisition. The analysis will run as a comparison against three well-known forensic software tools that are used widely by law enforcement and investigators including Autopsy [19], Magnet AXIOM [20], and Cellebrite [21]. This comparison will include a discussion of the current gaps that these software tools have, a recommendation for optimized drone forensic analysis, and evidence interpretation challenges. Moreover, we selected several open-source tools in this research to support our analysis (see Table 1 for a complete list of used tools in this research).

4. Findings

The comprehensive analysis of the DJI Matrice 210 and DJI Phantom 4 has led us to discover several issues that could be enhanced to support drone forensic examiners. Our evaluation was limited to the two selected drone models and forensic software tools. The outcome of our evaluation highlights some deficiencies pertaining to the tool’s performance. In addition, the results of our research help practitioners and researchers in the field to enhance the UAV investigative tools and techniques to overcome several technical challenges. The following Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 discuss our findings in detail.

4.1. Digital Forensic Tools Evaluation

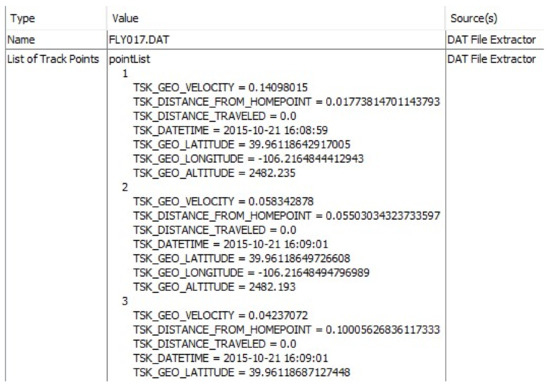

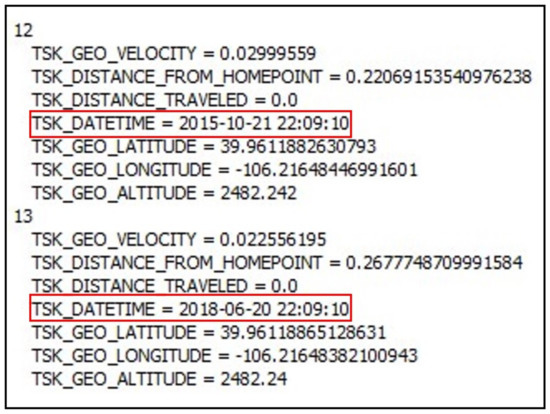

Most UAVs utilize a certain encryption structure for the processed and stored data. Flight logs, personally identifiable information, and event logs are necessary information that need to be analyzed and documented when conducting UAV forensic investigations. Our analysis indicates that Magnet Axiom forensic tool was not able to decrypt the recovered .DAT (i.e., encrypted) files and does not visualize flight routes at least on the two selected UAV models. On the contrary, Autopsy and Cellebrite tools were able to decrypt the .DAT files from both UAV models. These tools were supported by the DatCon file structure to process the file decryption. Although Autopsy was able to decrypt .DAT files, it displays the wrong timestamps on several waypoints at the beginning of the file (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A .DAT file parsed by the Autopsy tool.

Figure 2.

Highlighting the date issue on the parsed flight log by Autopsy.

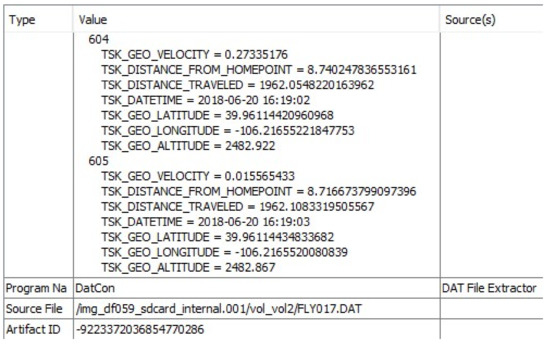

Moreover, we found that the DatCon tool is able to decrypt flight logs and convert the file format from .DAT to .CSV. The analysis was conducted on one extracted flight log from the DJI Matrice 210. In addition, DatCon tool provides investigators with a complete set of variables (e.g., blackbox data) such as the three principles of aviation including, yaw, pitch, and roll. The additional data recovered by DatCon is essential in an investigation; whereas, other forensic software tools (e.g., Autopsy and Cellebrite) do not demonstrate the original and complete set of variables recovered from the flight log. To this end, we emphasize the importance of presenting and documenting complete, reliable, and justifiable digital evidence. An example of the importance of these data is when an incident has an inadvertent intent and it has to be proofed at court by an investigator. The outcome of the extracted .DAT file after running the DatCon resulted in a file with 279 columns that hold much more data than what is represented in both tools (Autopsy and Cellebrite). Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the number of waypoints recovered by Autopsy and Cellebrite respectively. Moreover, Figure 5 displays Cellebrite two-dimensional (2D) visualization window.

Figure 3.

Autopsy decrytped and parsed 605 waypoints out of 17,998 waypoints.

Figure 4.

Cellebrite decrypted and parsed 946 waypoints out of 17,998 waypoints.

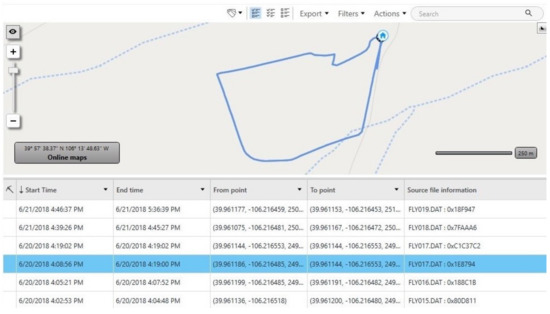

Figure 5.

A visualization map of the 946 waypoints recovered by Cellebrite.

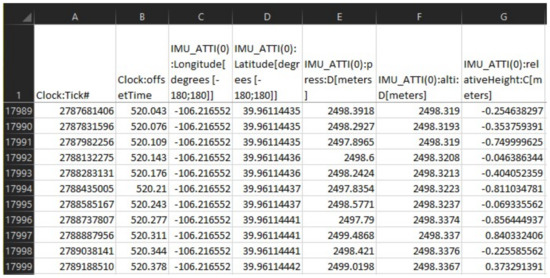

DatCon has provided the needful results to an investigator compared to Autopsy and Cellebrite tools. To the best of our knowledge, we discovered that Autopsy and Cellebrite generalize the recovered waypoints. For instance, they could be aggregating waypoints based on another column such as GPS:Time. Furthermore, the flight log illustrated in Figure 6 demonstrates the outcome of running the Datcon tool on the investigated .DAT file. The file comprises of sensor-based data including satellite channels, GPS signal, controller signal strength, battery level, motor speed, and precise three-dimensional GPS coordinates. We argue that these data could be useful in an investigation. However, Autopsy and Cellebrite tools consider only minimal flight records to the investigators.

Figure 6.

A screenshot of the decrypted .DAT file in .CSV format.

In addition, the CsvView tool helps in visualizing the flight trajectory by automatically parsing the .DAT file and decrypting it to a visualized map as shown in Figure 7. CsvView tool extracts and decrypts all event logs. These event logs are not well represented in some digital forensic tools (e.g., Autopsy). Our analysis indicates that DatCon performs better as it generates an identical decrypted file in .CSV format that aids in a complex investigation. Whereas, Autopsy and Cellebrite skip vital variables after processing the decryption of the file. Therefore, we discovered that flight logs decrypted by Autopsy and Cellebrite tools are not complete and identical to the original encrypted file (i.e., DAT file). This might raise some implications pertaining to the admissibility of digital evidence in court. In Section 4.3, we discuss these constraints in detail.

Figure 7.

A visual representation of the flight route using the CsvView.

Furthermore, we investigated an attribute (i.e., altitude) that could be a priority to UAV forensic investigators. Our analysis showed that there are differences in the representation and visualization of altitude associated with a flight route. Therefore, after digging deep into the file structure, which Autopsy and Cellebrite tools display after decrypting the .DAT files, we found that each tool selects a different variable to represent the altitude of the UAV. Autopsy parses the altitude from GPS:heightMSL[meters] column, whereas Cellebrite parses it from IMU_ATTI(0):alti:D[meters] column. According to the signal description provided by DatCon [22], IMU_ATTI(0):alti:D[meters] is calculating altitude/elevation based on barometer sensor and GPS:heightMSL[meters] is calculating the altitude based on mean sea level (MSL).

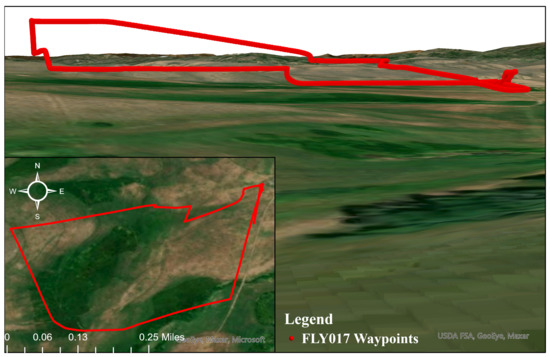

Moreover, our analysis shows that there is an approximate difference of 10–20 m from the parsed altitude for each of these two fields. Therefore, this difference in the altitude between Autopsy and Cellebrite tools might lead to inconsistency, hence possible wrong conclusions. In addition, there are more than one type of altitude fields that the drone logs (e.g., relative height, elevation from MSL, and elevation calculated using measuring the air pressure). We tested and plotted one flight path using multiple elevation columns. As a result of our three-dimensional representation of the data, we found that the altitude in GPS:heightMSL[meters] column, provides a more precise and realistic elevation. Figure 8 shows a 2D map supported by a 3D representation of the flight waypoints that were recovered from the DJI Matrice 210 for experiment purposes using ArcGIS Pro software. Our analysis has led us to apply a useful visualization approach using three-dimensional GPS coordinates. This will enhance the current visualization techniques when investigating drone incidents.

Figure 8.

2D and 3D representation of the flight log using ArcGIS Pro.

4.2. Technical Investigative Challenges

There are several challenges associated with the analysis, visualization, reporting, and documenting of digital evidence recovered from UAVs. These are obviously due to the different mechanism and data structures deployed on flying devices. However, we highlight the major technical issues that impact the integrity of digital investigations. For instance, our analysis indicated that timestamps are reported differently between Autopsy and Cellebrite tools. In Cellebrite, the plaintext output of the encrypted .DAT file) recovered from the following path: /img_df059_sdcard_internal.001/vol_vol2/FLY017.DAT with a date timestamp of 20/06/2018 at 4:08:56 pm in universal time coordinated-6 (UTC-06:00); whereas, Autopsy has processed the date timestamps of the same file as 21/10/2015 at 16:08:59 (UTC-06:00). For an ambiguous reason that could be associated with how Autopsy is processing the decryption of the .DAT files, we noticed that the first couple waypoints have off-date timestamps. Furthermore, Autopsy processes the encryption of the first waypoints of .DAT files with invalid date timestamp. The reason is not obvious as it requires the creation of multiple case scenarios to investigate this problem (see Figure 2 and Figure 4). In addition, we assume that there were some constraints pertaining to the decryption process due to the encrypted file structure and the decryption process.

On the other hand, a detailed explanation is given in Table 2 about the symbols used in Table 3 that illustrates a comparative analysis between several types of artifacts and two UAV models.

Table 2.

Explanation of symbols used in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tool evaluation based on DJI Phantom 4 and DJI Matrice 210 UAVs.

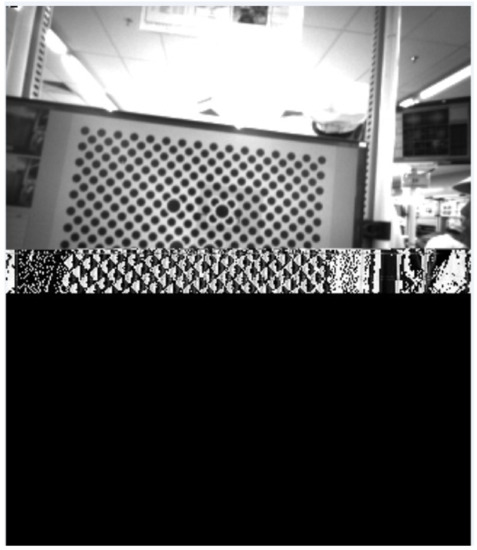

For the personal identifiable information (PII), we were able to partially recover some information from several sources such as the external and internal SD cards, and chip-offs for both UAV models. The PII data represent serial numbers, network records, and account setup timestamps. For instance, the drone serial number 095XF1800201C0 was recovered from the internal SD card within .DAT files and chip-off recovered from /img_eMMC_Chip_Off.001/Unalloc_1_0_62537072640 using Autopsy and Cellebrite; however, Magnet Axiom was not able to locate this information. Furthermore, our analysis on the Phantom 4 using Cellebrite has led us to the discovery of geolocations recovered from chip-offs, external, and internal SD cards. Cellebrite parses and displays the drone serial number and the battery-associated serial numbers to the investigator.

In comparison, Autopsy requires an investigator to conduct keyword searches to recover information such as BSSID, SSID, drone serial number, battery serial number, etc. Moreover, Figure 9 shows a partially recovered picture using Cellebrite and Magnet AXIOM tools from the chip-off image of the Phantom 4. This picture might be taken during the setup of the drone and was deleted. Therefore, we recommend investigators to conduct a chip-off forensic analysis with complex cases that might involve deleted data.

Figure 9.

A deleted picture recovered from chip-off.

4.3. Digital Evidence Integrity Using Open-Source Tools

We used the entropy analysis technique to measure and visualize the data for the four files in different formats. The technique was derived by Claude Shannon [23] and an explanation of the formula is given in Table 4. Shannon entropy is computed as follows:

Table 4.

Explanation of shannon entropy formula.

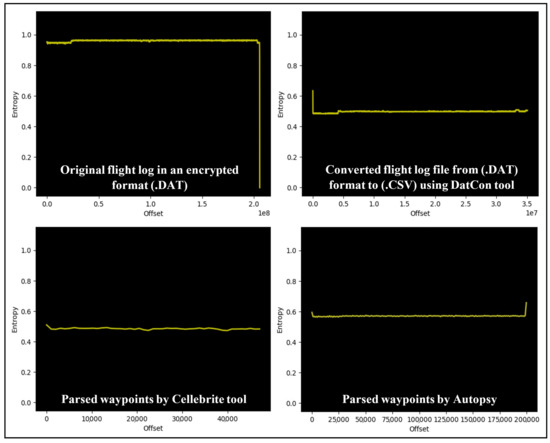

The comparison analysis illustrated in Figure 10 indicates that flight logs extracted from Autopsy and Cellebrite are not identical. Furthermore, there are differences between the original .DAT when converting the flight logs from .DAT to .CSV using DatCon.

Figure 10.

Entropy analysis of several flight logs parsed with different tools for integrity analysis.

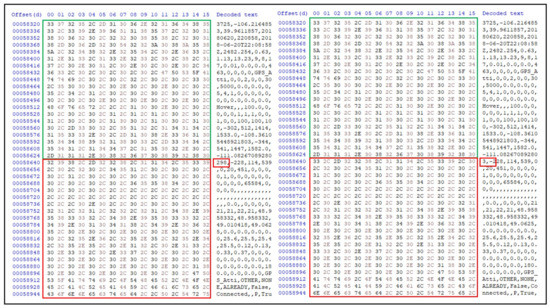

In Table 5, we show the comparative analysis of the original flight log file. For this analysis, we extracted the FLY017.DAT file from Cellebrite and recorded its MD5 hash values. The analysis was conducted using two different forensic workstations, and cross-validated using one forensic workstation, but storing the .DAT files in two different locations. Using the DatCon tool to decrypt the FLY017.DAT into a .CSV file format and record the hash values using forensic workstation one. Similarly, we repeated the process on the forensic workstation two to validate the integrity of the DatCon tool. Surprisingly, the generated hash values were not the same, indicating that the decryption process alters data in the file during the decryption process. The changes were not significant, but still considered as none reliable and might lead to inadmissibility of digital evidence in a court. We noted the difference in the size of the decrypted files from the two forensic workstations to show the slight changes in the size of these files. This means that these slight changes occurring with each decryption process of .DAT files might lead to unreliable digital evidence. For instance, a modification to the decrypted flight log by an investigator or tampered with by an attacker might be difficult to reasonably justify any changes to the recovered digital evidence. Furthermore, Figure 11 illustrates the changes in data after two decryption attempts of the same .DAT file using DatCon tool. The highlighted red box shows the starting offset of data change between the two files. We think that these changes occur when the tool rounds some values, which could question the integrity of digital evidence.

Table 5.

A checksum analysis to evaluate UAV digital evidence integrity.

Figure 11.

Data comparison analysis of the recovered flight log showing the beginning of byte change.

5. Discussion

Overall, the conducted evaluation and its outcome propose another direction that requires investigators, LAEs, and researchers to enhance the analysis, reporting, visualization, and documentation of UAV forensics. We illustrated some gaps linked to the analysis and visualization only considering the integrity and reproducibility of any recovered digital evidence. No common tool is able to perform a complete forensic analysis for UAVs, as we have demonstrated in Section 4. One reason is the large volume and heterogeneity of data transmitted via drone devices. Although there was no major difference between the files before and after the decryption process, the slight bit changes in the files could result in dismissing the evidence and issues to justify the analysis technique. Finally, we explored a new three-dimensional modeling technique that enables investigators in visualizing the complete patterns considering the altitude as an important factor that distinguishes between take-off and landing waypoints.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we conducted a comprehensive forensic analysis on two UAV models (DJI Phantom 4 and DJI Matrice 210) to connect the gap between UAV forensic tool developers and researchers. In our analysis, we examined personally identifiable information, tested and evaluated three well-known digital forensic tools along with open source available tools, discussed the integrity of the encryption and decryption procedures, and proposed a three-dimensional modeling technique to interpret the flight trajectory recovered from UAVs. For future work, we plan to further investigate the integrity and reliability of other artifacts recovered from UAVs, conduct a survey to understand the current system requirements for UAV forensic tools, and cover possible anti-forensic techniques.

Author Contributions

The authors of this paper have contributed to this work in the following ways. Conceptualization, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; methodology, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; validation, F.E.S. and M.M.M. and U.K.; formal analysis, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; Project administration, F.E.S. and M.M.M. Resources, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; investigation, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; writing—review and editing, F.E.S. and M.M.M. and U.K.; visualization, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; supervision, U.K.; project administration, F.E.S. and M.M.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FAA. UAS by the Numbers. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/uas/resources/by_the_numbers/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- INTERPOL to Issue Drone Guidelines for First Responders. Available online: https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2018/INTERPOL-to-issue-drone-guidelines-for-first-responders (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Watson, S. Drone Forensic Program. Available online: https://dfrws.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/pres_drone_forensics_program.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Clark, D.R.; Meffert, C.; Baggili, I.; Breitinger, F. DROP (DRone Open source Parser) your drone: Forensic analysis of the DJI Phantom III. Digit. Investig. 2017, 22, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.; Barton, T.E.A.; Islam, T. Drone forensic analysis using open source tools. J. Digit. Forensics Secur. Law 2018, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salamh, F.E.; Karabiyik, U.; Rogers, M.K. RPAS forensic validation analysis towards a technical investigation process: A case study of yuneec typhoon H. Sensors 2019, 19, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamh, F.E.; Karabiyik, U.; Rogers, M.; Al-Hazemi, F. Drone disrupted denial of service attack (3DOS): Towards an incident response and forensic analysis of remotely piloted aerial systems (RPASs). In Proceedings of the 15th International Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Tangier, Morocco, 24–28 June 2019; pp. 704–710. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, U.; Rogers, M.; Matson, E.T. Drone forensic framework: Sensor and data identification and verification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS), Glassboro, NJ, USA, 13–15 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, D.Y.; Chen, M.C.; Wu, W.Y.; Lin, J.S.; Chen, C.H.; Tsai, F. Drone Forensic Investigation: DJI Spark Drone as A Case Study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 159, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roder, A.; Choo, K.K.R.; Le-Khac, N.A. Unmanned aerial vehicle forensic investigation process: Dji phantom 3 drone as a case study. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.08649. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Barthaud, D.; Price, B.A.; Bandara, A.K.; Zisman, A.; Nuseibeh, B. LiveBox: A Self-Adaptive Forensic-Ready Service for Drones. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 148401–148412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.M.; Karabiyik, U. Enhancing IP Address Geocoding, Geolocating and Visualization for Digital Forensics. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC): Trust, Security and Privacy (ISNCC-2021 TSP), Dubaï, United Arab Emirates, 1–3 June 2021. Manuscript Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- Horsman, G. Unmanned aerial vehicles: A preliminary analysis of forensic challenges. Digit. Investig. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamh, F.E.; Karabiyik, U.; Rogers, M.K. Constructive DIREST Threat Model and Threat Assessment Framework for Drone as a Service (DaaS). J. Digit. Forensics Secur. Law 2021, 16, 2. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Chan, S.; Guizani, M. Drone-Assisted Public Safety Networks: The Security Aspect. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Qu, Z.; Zhou, C. Effects of a navigation spoofing signal on a receiver loop and a UAV spoofing approach. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, G.; Carrijo, G.; Miani, R.; Souza, J.; Guizilini, V. The Impact of DoS Attacks on the AR.Drone 2.0. In Proceedings of the XIII Latin American Robotics Symposium and IV Brazilian Robotics Symposium (LARS/SBR), Recife, Brazil, 8–12 October 2016; pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST: Drone Data Set. Available online: https://www.cfreds.nist.gov/drone-images.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Technology, B. Autopsy—Basis Technology. Available online: https://www.basistech.com/autopsy/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Forensics, M. Software and Downloads. Available online: https://support.magnetforensics.com/s/software-and-downloads (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Cellebrite. Products—Cellebrite. Available online: https://www.cellebrite.com/en/product/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- V3 .CSV Column Descriptions. Available online: https://datfile.net/DatCon/fieldsV3.html. (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).