Abstract

Minimizing the photon losses by depositing an anti-reflection layer can increase the conversion efficiency of the solar cells. In this paper, the impact of anti-reflection coating for enhancing the efficiency of silicon solar cells is presented. Initially, the refractive indices and reflectance of various materials were computed numerically using the calculator. After which, the reflectance of with different refractive indices were used for analyzing the performance of a silicon solar cells coated with these materials using simulator. and as single-layer anti-reflection coating yielded a short circuit current density () of and respectively. Highest efficiency of was obtained for the ARC layer with . With Double-layer anti-reflection coating , the improved by ∼0.5 for layer and hence the efficiency by . Blue loss reduces significantly for the compared with and hence increase in by 1 is observed. The values obtained is in good agreement with the reflectance values of the layers. The solar cell with obtained from the study showed that improved conversion efficiency of is obtained. Finally, it is essential to understand that the key parameters identified in this simulation study concerning the fabrication will make experimental validation faster and cheaper.

1. Introduction

With the substantial technological advancements, the potential for high conversion efficiency of crystalline silicon solar cells. Photovoltaic market dominated by crystalline silicon solar cells [1] by larger than worldwide. The efficiency of has been reached with based modules and is continuously escalating both in the research and in the commercial market. Theoretically, the bandgap, long radiative recombination lifetimes, Auger recombination of the generated carriers restrict the conversion efficiency to about [2,3,4]. It is mandatory to reduce the various losses (optical, carrier, and electrical loss) in solar cell to achieve the maximum conversion efficiency [5]. One of the key issues of the contemporary PV industry is reducing the optical losses which make up about efficiency loss in solar cells [6]. An approach to reduce the optical loss is to use an ARC at the front surface, which reduces the reflection losses and enhances the consequently, improving the conversion efficiency. Several researchers employed various ARCs that might be used to increase the efficiency of the solar cell. Thin films such as , etc., were used as layers [7,8,9,10,11]. was a commonly used on the front surface, owing to its versatility and inexpensive [7]. Though coatings possess better optical properties (high refractive index, low absorption coefficient) in the visible region, the passivation properties in addition to the optical properties made the manufacturers shift to plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposited . In the recent study by various researchers, films demonstrated the potential of delivering the exceptional passivation on boron-doped emitters [12,13,14]. is the ideal material for the encapsulated cell as its 2.1 at the wavelength of . In the earlier days of solar cell fabrication, was considered only for purposes. Later researchers found that / layers provided both surface passivation as well as layers. Hence the solar cell industry utilizes the / layers. However recent research found the passivation properties especially provided better surface passivation with surfaces. However, the change in its crystalline phase at higher temperatures hinders the application of in conventional commercial solar cells fabrication, which requires high-temperature metallisation firing. Hence it might be considered. Thus, optimizing the film with a trade-off between optical and passivation properties will be valuable for the industry.

However, the single-layer s employed in silicon solar cells still instigate substantial optical reflectance loss in a wide-ranging of the solar spectrum. Thus, high-efficiency solar cells utilize double-layer ARCs which improves the carrier collection by reducing the reflectance in the visible and in the near-IR range [15,16,17,18]. The ( or ) is a favorable design to enhance the efficiency owing to its benefits in both antireflection and surface passivation properties. Doshi et.al. optimized the film thickness and their refractive indices and utilized the / for their simulation [15]. With / layer, Lennie et al. obtained an efficiency of [16] using Silvaco ATLAS simulation. Similar work with simulation can be found elsewhere [17,18,19]. is the most commercially accessible software utilized by several groups to simulate solar cells with unique layers [20]. In most of the simulation studies, the maximum conversion efficiency of 3–13% only has been achieved [16,17,18,19].

In the present study, we employed the and on the actual industrial solar cell with a surface area of . Similarly, we analyzed the loss for each layer, to find the most optimum specification that can be employed for solar cell application. For , varying the thickness of the and its capping layer was one of the most novel concepts explored in this manuscript. This simulation-based approach highlighted in this manuscript plays a vital role in identifying the most optimal configuration of the layers for achieving increased efficiency of silicon solar cells. The simulation approach highly reduces the time and cost involved in testing the different combinations of layers and helps in identifying the optimal configuration of the layers. with different refractive indices were chosen as a capping layer when experimentally testing the layer. Mono-crystalline silicon solar cells were simulated using . The simulated device results were validated by comparing the solar cell fabricated with identical device parameters. This study offers a better insight into solar cell performance.

2. Simulation of Solar Cell

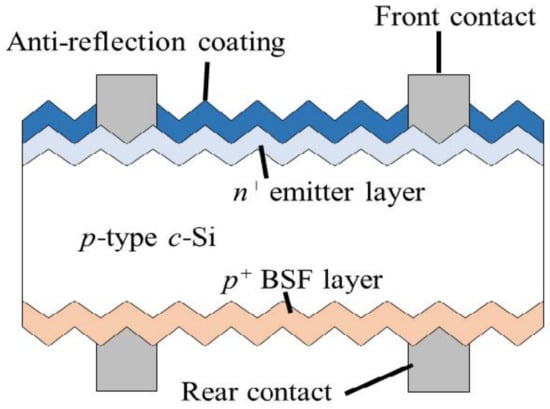

To simulate the solar cell behaviour software package is used in this study. The mathematical modelling tool used a more detailed silicon solar cell model as shown in Figure 1. To increase the conversion accuracy of solar cells we need an accurate solar cell modelling tool. After studying each layer’s physical and electrical parameters of the solar cell the tool helps in studying the impact of various parameters considered in the fabrication of the solar cells. In this study, the actual device configuration for simulating and optimizing the anti-reflection coating layer of solar cell is evaluated using simulation and the optimized configuration for achieving higher accuracy is obtained. Using numerical modelling tools such as to optimize the layer configurations reduces the cost, time, and effort required to analyze the impact of the change in the design of the solar cells.

Figure 1.

Silicon solar cell structure used for this study.

In the simulation tool, crystalline Si () solar cell device simulations are carried out using the following numerical equations representing the quasi-one-dimensional transportation of electrons and holes of a semiconductor material (Solar cells). Equations (1)–(7) gives us a clear cut idea of creating a model of a silicon cell and optimizing various process parameters including the coating layer properties [21].

The current densities of the electrons and the holes are represented as and respectively and they are numerically formulated as indicated in Equations (1) and (2). In which, the parameters n and p are the electron and hole density, and is the mobility of the electron and holes. The and are the diffusion coefficients that represents the difference in electron and hole quasi-Fermi energies and .

Equations (3) and (4) are derived from the law of conservation of charge or the continuity equation. where and are generation rate and recombination rate. Equation (5) represents Poisson’s equation for solving the electrostatic field problems. where and are acceptor and donor doping concentrations.

Here and are the effective density of states in the conduction and valence bands. To describe the type of material used, Fermi-Dirac statistics directly related to the band edges and and carrier densities are expressed in the Equations (7) and (8). The finite element approach is used to solve the three basic equations that assist in simulating the solar cell behaviours using the modelling tool. Many other process parameters are optimized using the simulation tool in the literature, but the proposed research aims to optimise the design process characteristics of the layer used in the fabrication of the solar cells. Finally, the efficiency of solar cells is calculated using the following equations.

where, represents the efficiency of the solar cell which is calculated using , , , , , and that indicates the maximum power, incident power, current at maximum power point, voltage at maximum power point, saturation current density, Open circuit voltage and fill factor.

In this present study, we have considered p-type wafer with resistivity of 1 (doping of , device area of , front surface textured with 3 depth. The emitter and back surface field was formed with doping concentration of and respectively. Bulk lifetime of 100 and front and rear surface recombination velocity of 10,000 were considered for solar cell simulation by PC1D. Numerous simulations were performed to study the impact of different parameters on the solar cell device performance. Base resistance , internal conductance S), light intensity (0.1 were kept constant during simulation. spectrum was used in this modelling.

3. Results and Discussion

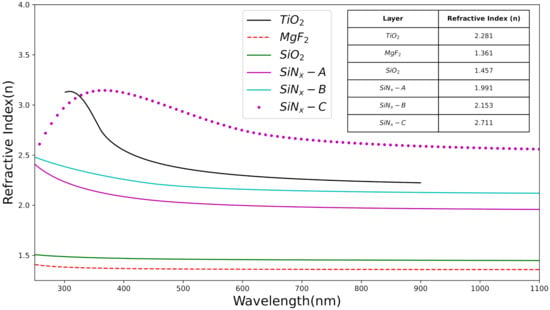

The refractive index as a function of wavelength defines the characteristics of an layer [22]. Figure 2 shows the wavelength dependent refractive indices of the layers such as [14], [23], [24], [9] thin films determined using the spectroscopic ellipsometer. The inset of Figure 2 shows the refractive index corresponding to each layer. The refractive index values of the and C at were about , and respectively.

Figure 2.

Refractive indices of various layers.

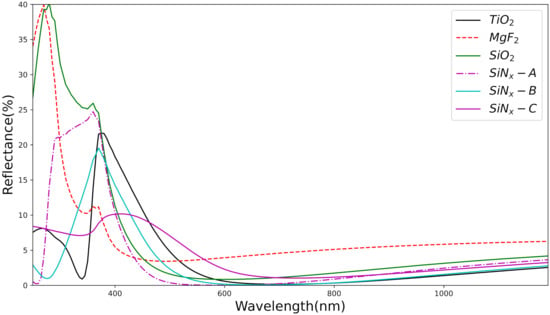

Reflectance spectra as a function of wavelength feed significant insights that can be used for investigating the optical properties of the , textured surface, and internal reflectance at the rear surface of the solar cell device. An optimal film for solar cells should possess (i) low optical losses and (ii) provide good surface passivation. Reflectance spectra exhibit characteristic minima that are defined by the following equation:

where t represents the thickness of the , represents the characteristic minimum wavelength, and n represents the index of refraction. For each layer with a different refractive index, the thickness of the layer was varied from 70–100 to keep the optical thickness of the film constant. Figure 3 shows the measured reflectance of the different layers coated on the textured surface. These reflectance values were measured using software. The simulator was also used to optimise the layer thickness of the single/double-layer coatings. The reflectance values were measured at the wavelength of . The reflectance of layers such as and are , and respectively. Overall, the lowest reflectance value is for and layer, closely followed by . Similar behaviour is observed in the case of saturation current density . Table 1 represents the parameters as well as the calculated blue loss and loss with different layers of was obtained for and layer and and for respectively. The values obtained is in good agreement with the reflectance values of the layers. Highest efficiency of was obtained for the layer with and . Current is one of the easiest factor that can be improved with substantial margin. Thus it is significant to enumerate systematically the source of loss, breaking them into (i) optical losses and (ii) collection losses. The optical loss is due to metal shading, reflection and parasitic absorption and the collection losses arises due to imperfect emitter collection. By investigating the losses, it gives a clear representation of possible improvement areas which helps the PV manufacturers to predict and plan the strategies on the cell and module level fabrication for the future. Despite the well-known fact that the Mg-based material is considered as the highly impactful material its associated drawback in terms of the loss was highlighted and alternative materials loss was evaluated and a detailed overview of the results was presented in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Reflectance spectra as a function of wavelength for some optimised single-layer anti-reflection coating.

Table 1.

parameters and ARC loss calculation based on the different SLARC layers.

Table 2.

parameters of the different layers.

To explain the variation in the with different layers, the ARC loss was calculated by considering the photon flux spectrum [25] and internal quantum efficiency of the solar cell.

where q is the elementary charge, lam denotes the photon flux of the standard air mass solar spectrum between 300 to is the reflectance and is the internal quantum efficiency as a function of wavelength.

Reflection loss lead to a reduction of in for layers, for thermal and for layers with different refractive indices, thus decreasing the efficiency with respective ARC layers. The front metal coverage is not considered while calculating the values and hence, the variation. By considering the metal coverage area (4–7%), the calculated unshaded values is in good agreement with the measured .

This loss may be reduced by tuning the optical properties (e.g., refraction index and thickness), as well as through improved front surface texturing for better light-trapping. In general, the optical properties of the materials are modified by replacing them with an alternate material to be used as the material. One other alternate way of reducing the loss is by optimizing the refractive indices of the layer. In this study, layers have been used with different refractive indices from n = 1.99; 2.15 and 2.711 to analyse the impact of the material used as the in the manuscript. From Table 1 it is inferred that the loss was higher for the layers with the highest refractive indices, and it reduces significantly with a reduction in the refractive indices. The blue loss is the combined effect of absorption, imperfect emitter collection, and front surface recombination. -related blue loss may be reduced to a certain extent by tuning the optical properties. Optimizing the emitter doping profile and junction depth can also help reduce emitter recombination losses. Front surface recombination can be reduced by improved front surface passivation.

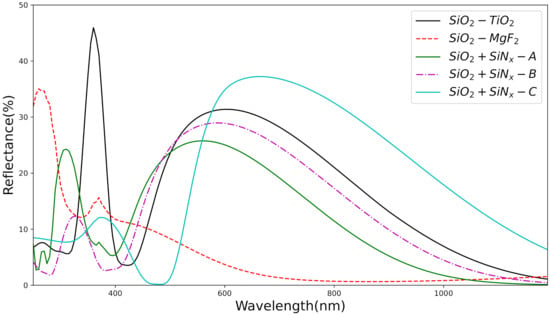

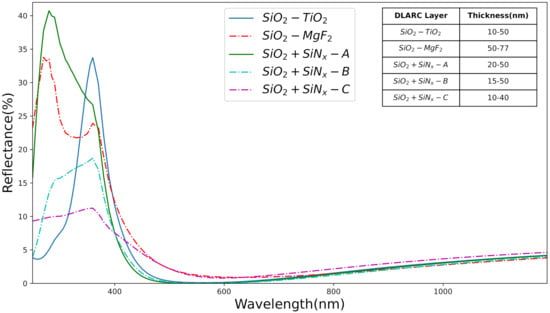

For further reduction in the reflectance, we considered the . Figure 4 depicts the reflectance spectra of various layers. The layer was capped with and layers. The thickness of the layer and the capping layers were fixed as and respectively. The reflectance was higher for all the layers and hence poor values which are depicted in Table 2. The high reflectance values for all the layers are attributed to the unequal optical thickness of the layer. The necessary and sufficient refractive index condition for a with equal optical thickness to give zero reflectance is [26]:

where is the admittance of the surrounding medium.

Figure 4.

Reflectance spectra as a function of wavelength for some double-layer anti-reflection coating.

Based on Equation (11) the optical thickness of the layers was optimized to obtain a minimum reflectance. Figure 5 shows the reflectance spectra of the layers. The inset of Figure 6 shows the thickness variation for both and the capping layer. The layer capped with and showed a reflectance of whereas for the and layers the reflectance was and respectively with the thickness of ∼60–70 . From the optimized reflectance curves, we can observe that when the reflectivity is substantially mitigated at the front surface, the gain in efficiency of the solar cell. Table 3 represents the parameters as well as the calculated blue loss and loss with optimized layers. With , the improved by ∼0.5 when the was capped with layer and hence the efficiency by . It can be observed that the blue loss reduces significantly for the compared with . This reduction can be attributed to the effective passivation provided by the layer. With , the reflection loss reduced by i.e., ∼1 in compared with .

Table 3.

parameters and loss calculation based on the optimized layers.

Table 3.

parameters and loss calculation based on the optimized layers.

| Layer | (mA/cm2) | (mV) | Eff (%) | Blue Loss (%) | ARC Loss [%] | Unshaded (mA/cm2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38.29 | 654.2 | 82.42 | 20.65 | 0.13 | 1.03 | 40.13 | |

| 38.11 | 654.1 | 82.43 | 20.55 | 0.13 | 1.42 | 39.74 | |

| 38.41 | 654.3 | 82.42 | 20.72 | 0.13 | 0.83 | 40.34 | |

| 38.52 | 654.4 | 82.42 | 20.78 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 40.49 | |

| 38.16 | 654.1 | 82.42 | 20.57 | 0.13 | 1.03 | 40.13 |

Figure 5.

Reflectance spectra as a function of wavelength with optimized thickness of double-layer anti-reflection coating.

Figure 6.

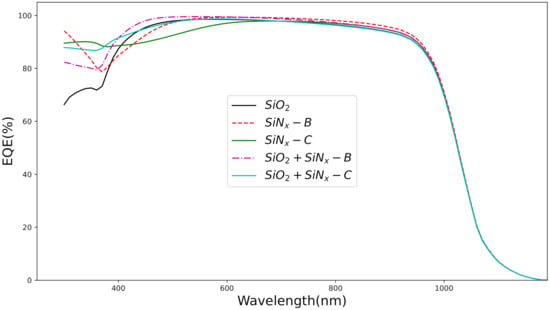

measurement carried on selected layers.

Figure 6 depicts the obtained on the selected ARC layers. of layer showed a better blue response compared with layers. However, the increase in for the layers is due to the better response i.e., more absorption in the long-wavelength region. From Figure 6 it is obvious that with the utilization of the layer, the carrier collection has improved significantly in the short wavelength range leading to the best conversion efficiency and . This enhancement in is attributed to the decrease in reflection with . It is sufficient to say, this effective collection of carriers reduce the recombination at the interface, and hence the overall is enhanced [10].

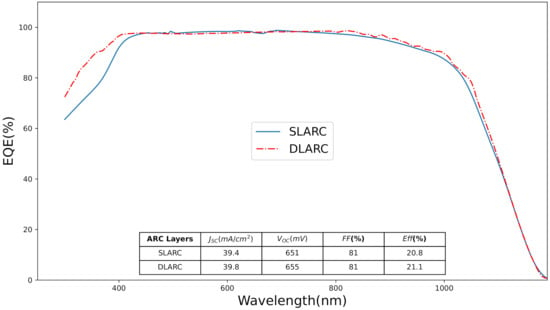

To validate the simulation data, a simulated device with identical parameters was compared to the measurements of actual solar cells in real application conditions. The industrial silicon solar cell was fabricated with both and . thick layer with the refractive index of was used as layer. with thick and with thick were used as layer. The monocrystalline silicon solar cell showed the conversion efficiency of and shown in the inset of Figure 7. spectra indicate that the efficiency improvement for a solar cell with the compared to the . This improvement at the short wavelength region is vital and it’s attributed mainly to the role of the . Thus, the stacked layers reduce the reflection of high energy photons. In addition, the layers provide better passivation thus enhancing the overall by reducing the surface recombination at the interface. The efficiency of the solar cell using the optimized layer settings is compared with the results obtained from the literature and presented in Table 4. The result indicated that the identified layer configuration outperforms the previously identified and layers highlighted in the literature.

Figure 7.

EQE measurement carried on single and double layer layers. Inset shows the IV results obtained with the solar cell measurement.

Table 4.

Comparison of the results obtained with different layers.

4. Conclusions

The impact of different anti-reflective coating layers on improving the efficiency of silicon solar cells has been studied in this manuscript. Initially, simulator was used to compute the refractive indices and reflectance of , and as materials. The calculated reflectance value of the material was later used in analyzing its performance on the silicon solar cells using software. The impact of the ARC as single and double-layered was studied in this research and results indicated that the and as yielded a of and respectively. Highest efficiency of was obtained for the layer with layer capped with , and layers showed the lowest reflectance of and respectively. layer increases the by ; thereby by increasing the efficiency by . The increase in by for is attributed to significant reduction in blue loss compared with .

Therefore, it is clear from the observation that the use of over will be advocated considering the impact of increased efficiency and reduced blue loss. This enhancement in for the is attributed to the decrease in reflection as well as a decrease in recombination at the interface. The values obtained is in good agreement with the reflectance values of the layers. Further research insights would be targeted towards experimentally evaluating the simulation results on the impact of identified layers with silicon solar cell efficiency. The simulation approach highlighted in this manuscript has a bigger advantage in terms of reducing the cost and time required for identifying the best-suited combination of ARC layers that can be considered for the silicon solar cells with finally resulting in higher efficiency. Future research can be benefited from the methodology used in the simulation study to identify the impact of new materials in or fabrication or to identify the optimized parameters required for the fabrication of the silicon solar cells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. (Maruthamuthu Subramanian), O.M.A. and S.G.; methodology, M.A., M.U. and M.S. (Maruthamuthu Subramanian); software, O.M.A., G.S.T. and E.J.; validation, M.S. (Maruthamuthu Subramanian), O.M.A., L.V., S.G. and M.S. (Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian); formal analysis, G.S.T.; investigation, M.A., S.G. and M.U.; resources, M.S. (Maruthamuthu Subramanian) and O.M.A.; data curation, G.S.T., E.J. and M.S. (Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian); writing—original draft preparation, S.G., M.S. (Maruthamuthu Subramanian) and G.S.T.; writing—review and editing, E.J., M.S. (Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian), A.S., M.A., M.U. and S.M.; visualization, G.S.T., E.J., L.V. and M.S. (Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project Grant (RSP-2021/61), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/61), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for the financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andreani, L.C.; Bozzola, A.; Kowalczewski, P.; Liscidini, M.; Redorici, L. Silicon solar cells: Toward the efficiency limits. Adv. Phys. X 2019, 4, 1548305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tiedje, T.; Yablonovitch, E.; Cody, G.D.; Brooks, B.G. Limiting efficiency of silicon solar cells. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1984, 31, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A. Limits on the open-circuit voltage and efficiency of silicon solar cells imposed by intrinsic Auger processes. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1984, 31, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga, T. Advances in crystalline silicon solar cell technology for industrial mass production. NPG Asia Mater. 2010, 2, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tavkhelidze, A.; Bibilashvili, A.; Jangidze, L.; Gorji, N.E. Fermi-Level Tuning of G-Doped Layers. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.D.; Cousins, P.; Westerberg, S.; De Jesus-Tabajonda, R.; Aniero, G.; Shen, Y.C. Toward the practical limits of silicon solar cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2014, 4, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, B. Comparison of TiO2 and other dielectric coatings for buried-contact solar cells: A review. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2004, 12, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, A.G.; Hezel, R. Progress in low-temperature surface passivation of silicon solar cells using remote-plasma silicon nitride. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 1997, 5, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttagupta, S.; Ma, F.; Hoex, B.; Mueller, T.; Aberle, A.G. Optimised antireflection coatings using silicon nitride on textured silicon surfaces based on measurements and multidimensional modelling. Energy Procedia 2012, 15, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ju, M.; Balaji, N.; Park, C.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Cui, J.; Oh, D.; Jeon, M.; Kang, J.; Shim, G.; Yi, J. The effect of small pyramid texturing on the enhanced passivation and efficiency of single c-Si solar cells. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 49831–49838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remache, L.; Mahdjoub, A.; Fourmond, E.; Dupuis, J.; Lemiti, M. Influence of PECVD SiOx and SiNx: H films on optical and passivation properties of antireflective porous silicon coatings for silicon solar cells. Phys. Status Solidi C 2011, 8, 1893–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.F.; McIntosh, K.R. Light-enhanced surface passivation of TiO2-coated silicon. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2012, 20, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Hoex, B.; Shetty, K.D.; Basu, P.K.; Bhatia, C.S. Passivation of boron-doped industrial silicon emitters by thermal atomic layer deposited titanium oxide. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2015, 5, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Allen, T.; Wan, Y.; Mckeon, J.; Samundsett, C.; Yan, D.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Y.; Verlinden, P.; et al. Titanium oxide: A re-emerging optical and passivating material for silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 158, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, P.; Jellison, G.E.; Rohatgi, A. Characterization and optimization of absorbing plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposited antireflection coatings for silicon photovoltaics. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 7826–7837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennie, A.; Abdullah, H.; Shila, Z.; Hannan, M. Modelling and simulation of SiO/Si N as anti-reflecting. World Appl. Sci. J. 2010, 11, 786–790. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, G.; Rashid, M.J.; Mahmood, Z.H.; Hoq, M.; Rahman, M.H. Investigation of the impact of different ARC layers using PC1D simulation: Application to crystalline silicon solar cells. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2018, 12, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, R. Silicon nitride as antireflection coating to enhance the conversion efficiency of silicon solar cells. Turk. J. Phys. 2018, 42, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.N.; Marstein, E.S.; Holt, A. Double layer anti-reflective coatings for silicon solar cells. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the Thirty-First IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 3–7 January 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1237–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Clugston, D.; Basore, P. PC1D version 5: 32-bit solar cell modeling on personal computers. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Anaheim, CA, USA, 29 September–3 October 1997; pp. 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukkarasu, G.S.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Chandran, J.; Stojcevski, A.; Subramanian, M.; Marnadu, R.; Alfaify, S.; Shkir, M. Optimization of Mono-Crystalline Silicon Solar Cell Devices Using PC1D Simulation. Energies 2021, 14, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; McIntosh, K.R.; Thomson, A.F. Characterisation and optimisation of PECVD SiNx as an antireflection coating and passivation layer for silicon solar cells. AIP Adv. 2013, 3, 032113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueiros, J.M.; Machorro, R.; Regalado, L.E. Determination of the optical constants of MgF2 and ZnS from spectrophotometric measurements and the classical oscillator method. Appl. Opt. 1988, 27, 2549–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edward, D.P.; Palik, I. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.M.; Conibeer, G.J. Limiting efficiency of generalized realistic c-Si solar cells coupled to ideal up-converters. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.T.; Hass, G. Antireflection coatings for optical and infrared materials. Phys. Thin Film. 1968, 2, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji, N.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Park, C.; Ju, M.; Raja, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Jeyakumar, R.; Yi, J. Electrical and optical characterization of SiOxNy and SiO2 dielectric layers and rear surface passivation by using SiO2/SiOxNy stack layers with screen printed local Al-BSF for c-Si solar cells. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2018, 18, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, N.; Lee, S.; Park, C.; Raja, J.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Chatterjee, S.; Nikesh, K.; Jeyakumar, R.; Yi, J. Surface passivation of boron emitters on n-type c-Si solar cells using silicon dioxide and a PECVD silicon oxynitride stack. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 70040–70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Gong, D.; Balaji, N.; Lee, Y.J.; Yi, J. Stability of SiN X/SiN X double stack antireflection coating for single crystalline silicon solar cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).