Design and Characterization of Cosmetic Creams Based on Natural Oils from the Rosaceae Family

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Cosmetic Creams

2.2.2. Characterization of Cosmetic Creams

2.2.3. Emulsion Stability

2.2.4. Spreadability

2.2.5. Rheological Studies

2.2.6. Antioxidant Activity

- DPPH Assay

- Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Cosmetic Creams by Varying the Content of Individual Oils and Technological Parameters

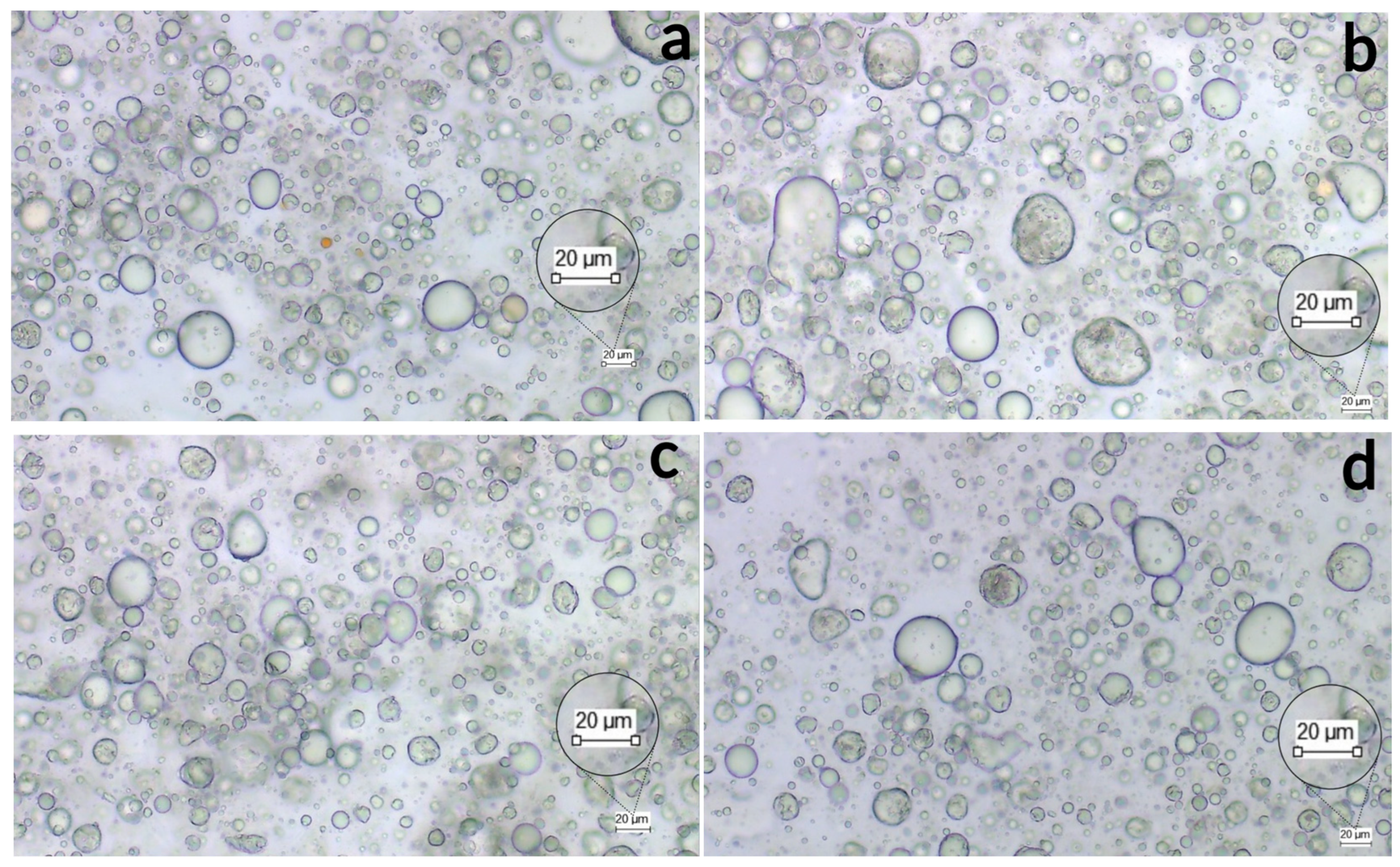

3.2. Emulsion Stability

3.3. Spreadability

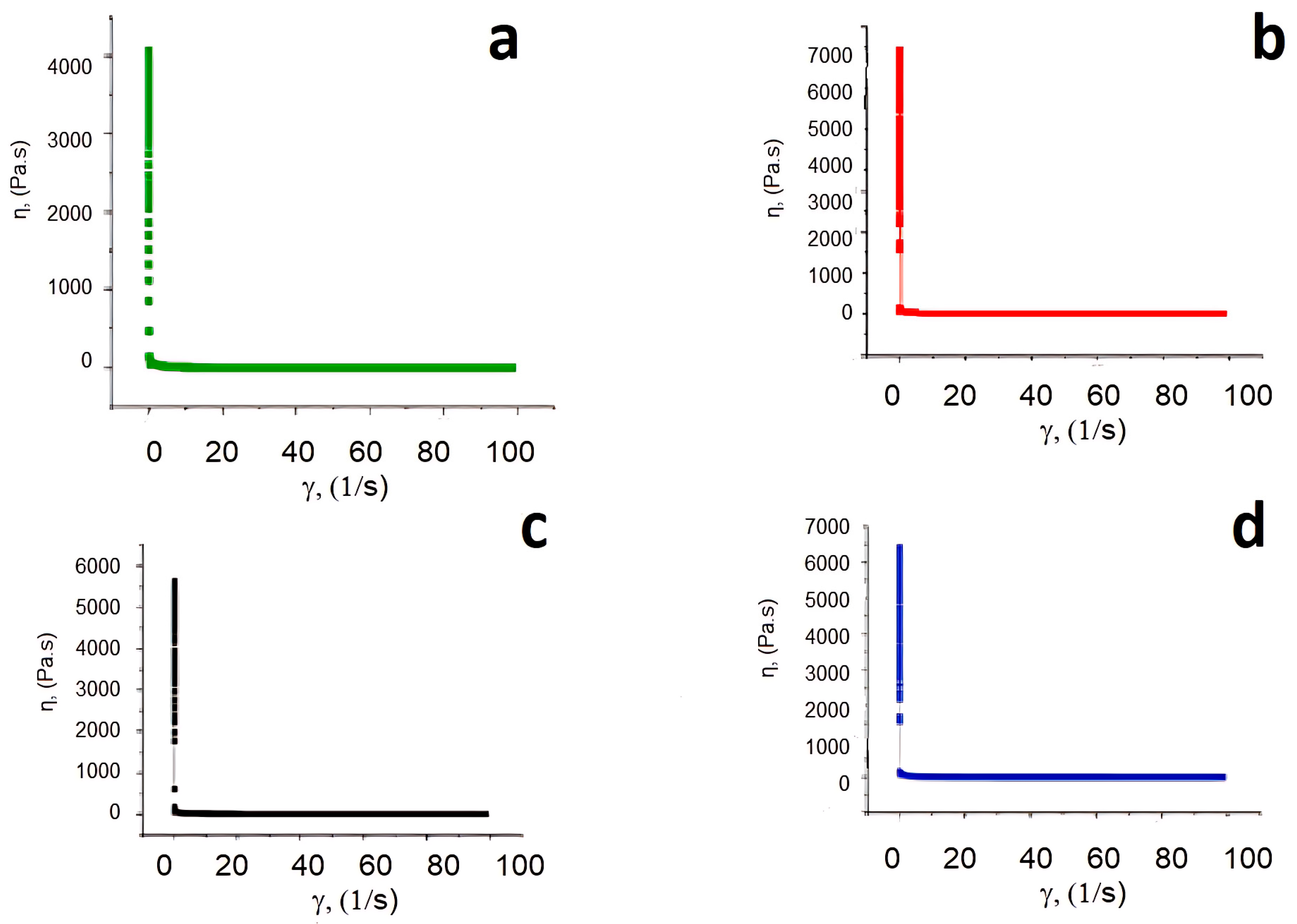

3.4. Rheological Studies

3.5. Freeze–Thaw Test

3.6. Antioxidant Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| HAT | Hydrogen atom transfer |

| O/W | Oil-in-water |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| TEWL | Transepidermal water loss |

| TPTZ | 4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| W/O | Water-in-oil |

References

- Tekade, G.; Bhosle, N.; Chavan, R.; Deshmukh, S.; Patil, G.; Wagh, P. Creams: An Overview of Classification, Preparation Techniques, Assessment, and Uses. IJERMDC 2024, 11, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Oargă, D.P.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Nemeș, S.A.; Cordea, M.I. The Effectiveness of a Topical Rosehip Oil Treatment on Facial Skin Characteristics: A Pilot Study on Wrinkles, UV Spots Reduction, Erythema Mitigation, and Age-Related Signs. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Vaidya, D.; Gupta, A.; Kaushal, M. Formulation and evaluation of wild apricot kernel oil based massage cream. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Othman, S.; Bleive, U.; Kaldmäe, H.; Aluvee, A.; Rätsep, R.; Karp, K.; Maciel, L.; Herodes, K.; Rinken, T. Phytochemical characterization of oil and protein fractions isolated from Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica) wine by-product. LWT 2023, 178, 114632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nováčková, A.; Sagrafena, I.; Pullmannová, P.; Paraskevopoulos, G.; Dwivedi, A.; Mazumder, A.; Růžičková, K.; Slepička, P.; Zbytovská, J.; Vávrová, K. Acidic pH Is Required for the Multilamellar Assembly of Skin Barrier Lipids In Vitro. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamińska, W.; Neunert, G.; Siejak, P.; Polewski, K.; Tomaszewska-Gras, J. Cold Pressed Oil from Japanese Quince Seeds (Chaenomeles japonica): Characterization Using DSC, Spectroscopic, and Monolayer Data. Molecules 2025, 30, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, E.; Marina, M.; García, M. Apricot. In Valorization of Fruit Processing By-Products, 1st ed.; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bhanger, M.; Anwar, F.; Memon, N.; Qadir, R. Cold pressed apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) kernel oil. In Cold Pressed Oils Green Technology, Bioactive Compounds, Functionality, and Applications, 1st ed.; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 725–730. [Google Scholar]

- Saçkesen, S.; Karakaya, S.; Durmaz, G.; Gündüz, O.; Şahingil, D.; Hayaloğlu, A. Unveiling the Potential of EU PDO Registered Malatya Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.): Compositional, Functional, Nutritional, and Economic Aspects. ACS FST 2025, 5, 909–924. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Lu, Y.; Wei, J.; Han, L. Amygdalin alleviates psoriasis-like lesions by improving skin barrier function. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, M.; Grant-Kels, J. Healing fats of the skin: The structural and immunologic roles of the omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. Clin. Dermatol. 2010, 4, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryjecka, M.; Kiełtyka-Dadasiewicz, A.; Micha, M. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Rosa canina L. Seeds and Determining Their Potential Use. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseke, T.; Opara, U.L.; Fawole, O.A. Fatty acid composition, bioactive phytochemicals, antioxidant properties, and oxidative stability of edible fruit seed oil: Effect of preharvest and processing factors. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padamwar, M.; Pawar, A.; Daithankar, A.; Mahadik, K. Silk sericin as a moisturizer: An in vivo study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2005, 4, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Xu, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, D.; Xing, T.; Chen, G. Study on the application of sericin in cosmetics. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 796, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragojlov, I.; Aad, R.; Ami, D.; Mangiagalli, M.; Natalello, A.; Vesentini, S. Silk Sericin-Based Electrospun Nanofibers Forming Films for Cosmetic Applications: Preparation, Characterization, and Efficacy Evaluation. Molecules 2025, 30, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, K.; Hongo, N.; Karato, M.; Yamashita, E. Cosmetic benefits of astaxanthin on human subjects. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2012, 59, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santocono, M.; Zurria, M.; Berrettini, M.; Fedeli, D.; Falcioni, G. Influence of astaxanthin, zeaxanthin and lutein on DNA damage and repair in UVA-irradiated cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2006, 85, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pârvănescu, R.; Trandafirescu, C.; Musuc, A.M.; Ozon, E.A.; Culita, D.C.; Mitran, R.-A.; Stănciulescu, C.-I.; Șoica, C. Comparative Physicochemical and Pharmacotechnical Evaluation of Three Topical Gel-Cream Formulations. Gels 2025, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocai, A.; Memete, A.; Ganea, M.; Vicas, L.; Gligor, O.; Vicas, S. The Formulation of Dermato-Cosmetic Products Using Sanguisorba minor Scop. Extract with Powerful Antioxidant Capacities. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Chaudhary, S.; Chaudhary, A. Emulgel—Emerging as a Smarter Value-Added Product Line Extension for Topical Preparation. Indo Global J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 12, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkreli, R.; Terziu, R.; Memushaj, L.; Dhamo, K.; Malaj, L. Selected Essential Oils as Natural Ingredients in Cosmetic Emulsions: Development, Stability Testing and Antimicrobial Activity. Indian. J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2023, 57, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Ren, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z. Investigating Texture and Freeze–Thaw Stability of Cold-Set Gel Prepared by Soy Protein Isolate and Carrageenan Compounding. Gels 2024, 10, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Santonocito, D.; Puglia, C.; Montenegro, L. Effects of Lipid Phase Content on the Technological and Sensory Properties of O/W Emulsions Containing Bemotrizinol-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leusheva, E.; Brovkina, N.; Morenov, V. Investigation of Non-Linear Rheological Characteristics of Barite-Free Drilling Fluids. Fluids 2021, 6, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.; Vrancheva, R.; Marchev, A.; Petkova, N.; Aneva, A.; Denev, P.; Georgiev, V.; Pavlov, A. Antioxidant activities and phenolic compounds in Bulgarian Fumaria species. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Benzie, I.; Strain, J. Ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurman, S.; Yulia, R.; Irmayanti; Noor, E.; Candra Sunarti, T. The Optimization of Gel Preparations Using the Active Compounds of Arabica Coffee Ground Nanoparticles. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannozzi, C.; Foligni, R.; Scalise, A.; Mozzon, M. Characterization of lipid substances of rose hip seeds as a potential source of functional components: A review. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 721–733. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjecka, M.; Kiełtyka-Dadasiewicz, A.; Michalak, M.; Rachoń, L.; Głowacka, A. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Oils from the Seeds of Five Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Cultivars. J. Oleo Sci. 2019, 68, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Siger, A.; Juhņeviča, K.; Lācis, G.; Šnē, E.; Segliņa, D. Cold-pressed Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. ex Spach) seed oil as a rich source of α-tocopherol, carotenoids and phenolics: A comparison of the composition and antioxidant activity with nine other plant oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Hassan, M.; Lu, H. Effects of flow behavior index and consistency coefficient on hydrodynamics of power-law fluids and particles in fluidized beds. Powder Technol. 2020, 366, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezger, T.G. The Rheology Handbook, 2nd ed.; Mezger, T.G., Ed.; Vincentz Network Gmbh & Co KG: Hannover, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Calienni, M.N.; Martínez, L.M.; Izquierdo, M.C.; Alonso, S.d.V.; Montanari, J. Rheological and Viscoelastic Analysis of Hybrid Formulations for Topical Application. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Gil, M.E.; Graça, A.; Martins, A.; Marto, J.; Ribeiro, H.M. Emollients in dermatological creams: Early evaluation for tailoring formulation and therapeutic performance. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 653, 123825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danby, S.G.; Andrew, P.V.; Taylor, R.N.; Kay, L.J.; Chittock, J.; Pinnock, A.; Ulhaq, I.; Fasth, A.; Carlander, K.; Holm, T.; et al. Different types of emollient cream exhibit diverse physiological effects on the skin barrier in adults with atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghi, M.; Namjoshi, S.; Panchal, B.; Grice, J.E.; Prakash, S.; Roberts, M.S.; Mohammed, Y. Viscoelastic and Deformation Characteristics of Structurally Different Commercial Topical Systems. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djiobie Tchienou, G.E.; Tsatsop Tsague, R.K.; Mbam Pega, T.F.; Bama, V.; Bamseck, A.; Dongmo Sokeng, S.; Ngassoum, M.B. Multi-Response Optimization in the Formulation of a Topical Cream from Natural Ingredients. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Ueno, S. Crystallization, transformation and microstructures of polymorphic fats in colloidal dispersion states. Curr. Opin. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2011, 5, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.P.; Masuchi, M.H.; Miyasaki, E.K.; Domingues, M.A.; Stroppa, V.L.; de Oliveira, G.M.; Kieckbusch, T.G. Crystallization modifiers in lipid systems. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 3925–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Błońska-Sikora, E.; Dobros, N.; Spałek, O. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Properties, and Cosmetic Applications of Selected Cold-Pressed Plant Oils from Seeds. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, M.; Deniz, I.; Okan, O.; Baltaci, C.; Karatas, S. Determination of the Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Different Parts of Rosacanina L. and Rosa pimpinellifolia L. Essential Oils. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2021, 24, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, S.; Bayraktar, N. Chemical Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Rosa canina L. from Çekerek Region of Yozgat, Türkiye. Bozok J. Sci. 2024, 2, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, I.; Stănilă, A.; Stănilă, S. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of Rosa canina L. biotypes from spontaneous flora of Transylvania. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, D.; Čukanović, J.; Kolarov, R.; Galečić, N.; Skočajić, D.; Vujičić, D.; Ocokoljić, M. Chaenomeles japonica (thunb.) Lindl.—Fruit crop in the context of climate change: Cultural and ecosystem services. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Challenges of Contemporary Hight Education, Kopaonik, Serbia, 3–7 February 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanavičiūtė, I.; Liaudanskas, M.; Bobinas, C.; Šarkinas, A.; Rezgienė, A.; Viskelis, P. Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles japonica) as a Potential Source of Phenols: Optimization of the Extraction Parameters and Assessment of Antiradical and Antimicrobial Activities. Foods 2020, 9, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratianni, F.; d’Acierno, A.; Ombra, M.; Amato, G.; De Feo, V.; Ayala-Zavala, J.; Coppola, R.; Nazzaro, F. Fatty Acid Composition, Antioxidant, and in vitro Anti-inflammatory Activity of Five Cold-Pressed Prunus Seed Oils, and Their Anti-biofilm Effect Against Pathogenic Bacteria. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 775751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, V.; Bele, C.; Poiana, M.; Dumbrava, D.; Raba, D.; Jianu, C. Evaluation of bioactive compounds and of antioxidant properties in some oils obtained from food industry by-products. Rom. Biotech. Lett. 2011, 16, 6234–6241. [Google Scholar]

- Grajzer, M.; Szmalcel, K.; Kuzminski, L.; Witkowski, M.; Kulma, A.; Prescha, A. Characteristics and Antioxidant Potential of Cold-Pressed Oils—Possible Strategies to Improve Oil Stability. Foods 2020, 9, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunik, O.; Saribekova, D.; Lazzara, G.; Cavallaro, G. Emulsions based on fatty acid from vegetable oils for cosmetics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohvina, H.; Sándor, M.; Wink, M. Effect of Ethanol Solvents on Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Properties of Seed Extracts of Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) Varieties and Determination of Phenolic Composition by HPLC-ESI-MS. Diversity 2022, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Mathematical Equation |

|---|---|

| Power law model (PLM) | |

| Herschel–Bulkley model (HBM) |

| Composition (% w/w) | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neofin Nat | 8% | 8% | 8% | 8% |

| Chaenomelis japonica seed oil (Japanese quince seed oil) | 8% | - | - | 2.7% |

| Rosa canina seed oil (Rosehip oil) | - | 8% | - | 2.7% |

| Prunus armeniaca kernel oil (Apricot kernel oil) | - | - | 8% | 2.7% |

| Astaxanthin | 0.005% | 0.005% | 0.005% | 0.005% |

| Silk protein (Sericin) | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Phenoxyethanol | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Purified water | up to 100% | up to 100% | up to 100% | up to 100% |

| Fragrance | Cydonia oblonga (quince) 4 drops | - | Prunus armeniaca (apricot) 4 drops | Mixture of Cydonia oblonga (2 drops) and Prunus armeniaca (2 drops) |

| Physical Appearance | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical state | semisolid | semisolid | semisolid | semisolid |

| Color | orange-light beige | peach beige | pale pink-beige | pale orange-light beige |

| Fragrance | quince | rosehip | apricot | fruity |

| Texture | smooth | smooth | smooth | smooth |

| Consistency | thick viscous | thick viscous | thick viscous | thick viscous |

| pH | 5.5 ± 0.07 | 5.34 ± 0.04 | 6.03 ± 0.08 | 6.12 ± 0.02 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic Type | Diameter (µm) | Diameter (µm) | Diameter (µm) | Diameter (µm) |

| Mean | 8.084 | 7.963 | 7.268 | 11.111 |

| Standard Error | 1.025 | 0.665 | 0.755 | 1.113 |

| Confidence Interval Lower | 6.075 | 6.659 | 5.788 | 8.928 |

| Confidence Interval Upper | 10.094 | 9.267 | 8.748 | 13.294 |

| Total Count | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Type of Model | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLM | K = 40.015 ± 0.985 Pa·sn n = 0.143 ± 0.006 R2 = 0.858 | K = 46.465 ± 0.824 Pa·sn n = 0.164 ± 0.002 R2 = 0.951 | K = 46.302 ± 0.857 Pa·sn n = 0.164 ± 0.004 R2 = 0.946 | K = 57.368 ± 1.521 Pa·sn n = 0.171 ± 0.006 R2 = 0.911 |

| HBM | τ0 = 0.003 ± 0.000 Pa K = 40.199 ± 1.286 Pa·sn n = 0.143 ± 0.004 R2 = 0.856 | τ0 = 0.002 ± 0.000 Pa K = 52.310 ± 1.090 Pa·sn n = 0.148 ± 0.002 R2 = 0.940 | τ0 = 0.001 ± 0.000 Pa K = 52.270 ± 1.020 Pa·sn n = 0.147 ± 0.003 R2 = 0.9276 | τ0 = 0.002 ± 0.000 Pa K = 57.371 ± 1.180 Pa·sn n = 0.170 ± 0.032 R2 = 0.911 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | η (Pa·s) | η (Pa·s) | η (Pa·s) | η (Pa·s) |

| 1 | 2030.32 ± 22.57 | 688.61 ± 3.71 | 7114.67 ± 19.76 | 9827.00 ± 15.31 |

| 2 | 4918.52 ± 27.66 | 6482.68 ± 11.12 | 5436.83 ± 17.78 | 9300.54 ± 17.29 |

| 3 | 7849.30 ± 16.80 | 2.50 ± 0.25 | 6879.00 ± 18.03 | 9100.27 ± 16.80 |

| Cream Formulation | DPPH Method (μmol TE/100 g) | FRAP Method (μmol TE/100 g) |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | 79.85 c ± 1.47 | 122.17 a± 5.47 |

| C2 | 105.37 a ± 2.20 | 120.10 a ± 3.01 |

| C3 | 72.57 d ± 2.32 | 82.87 b ± 2.56 |

| C4 | 93.38 b ± 2.40 | 120.40 a ± 3.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hutova, K.; Andonova, V.; Panova, N.; Ivanov, I.; Nikolova, K.; Gugleva, V. Design and Characterization of Cosmetic Creams Based on Natural Oils from the Rosaceae Family. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060248

Hutova K, Andonova V, Panova N, Ivanov I, Nikolova K, Gugleva V. Design and Characterization of Cosmetic Creams Based on Natural Oils from the Rosaceae Family. Cosmetics. 2025; 12(6):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060248

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutova, Katya, Velichka Andonova, Natalina Panova, Ivan Ivanov, Krastena Nikolova, and Viliana Gugleva. 2025. "Design and Characterization of Cosmetic Creams Based on Natural Oils from the Rosaceae Family" Cosmetics 12, no. 6: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060248

APA StyleHutova, K., Andonova, V., Panova, N., Ivanov, I., Nikolova, K., & Gugleva, V. (2025). Design and Characterization of Cosmetic Creams Based on Natural Oils from the Rosaceae Family. Cosmetics, 12(6), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060248