Abstract

The lack of interest in the reuse of phosphorus in agriculture is mainly due to the high abundance of pathogens, organic pollutants, microplastics, and possibly toxic metals. Therefore, different forms of treatment are necessary to take advantage of phosphorus recovery potential, one of which is the use of ash from incinerated/calcined biological sludge. A high rate of conversion of the non-apatite inorganic phosphorus fraction into apatite phosphorus was obtained in this study because of the use of commercially pure CaO additive in the dry sludge calcination tests, which is more bioavailable to plants. The obtained phosphorus pentoxide content ranged from 12 to 17%, surpassing several phosphorus-based raw materials and fertilizers. In addition, the ashes have been shown to contain toxic metals far below those recommended by Brazilian and international environmental legislation, so they can be applied directly to the soil for crop fertilization, or be used in P extraction and separation technologies for fertilizer production.

1. Introduction

The impact of climate change on environmental preservation has been analyzed more intensively in recent years. The environment has always been treated as a supplier of infinite natural resources and consequently a depository for waste, and it is not sustainable to coexist with this type of situation. Humanity has begun to realize the need to reuse, recycle, and treat waste generated due to environmental chaos and public health, which is identified by the absence of environmentally correct measures. The indiscriminate exploitation of natural resources is also a concern, as its growth may impact, in the absence of essential resources, the survival of humanity in a shorter period; that is, sustainable development must be the primary objective of world leaders.

Faced with such an environmental problem, it is alarming to see the growing demand for and accelerated extraction of ores, such as phosphorus mineral resources, and the consequent risk of depletion of deposits, which is estimated to occur around 50 to 100 years from now. In addition, 75% of the phosphorus extracted worldwide comes from Morocco; that is, the country holds more than half of the world’s viable reserves of extraction, which can generate high food insecurity for countries in the event of wars or problems in trade relations. There are no other substitute chemical elements, as the element is an essential macronutrient for plants along with nitrogen and potassium, and it is even necessary in the form of an additive for livestock feed in a considerable amount, as reported by Cordell et al. [1,2] and Ye et al. [3].

Phosphorus also has a polluting potential, as it is a limiting agent in the blooms of algae such as cyanobacteria frequently observed in water sites around the world, and the occurrence is facilitated both by transporting fertilizers to the water site, and mainly by non-treated sewage, rich in phosphorus and nitrogen, naturally discharged into water resources (Rosa et al. [4] and Sawska et al. [5]).

Although there are considerable amounts of phosphorus, nitrogen, and organic matter in domestic sewage owing to the mixture of urine and feces, the use of untreated sewage for fertilization and crop irrigation purposes is not recommended, as there are, for example, many pathogenic microorganisms present. The use of treated sewage is a viable alternative (Eagle et al. [6], Lima et al. [7], Ye et al. [3], Kominko et al. [8], and Olasupo et al. [9]).

Domestic sewage has a high influent Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD); that is, there is a high amount of biodegradable organic matter, so it is necessary to apply biological treatments in effluent treatment plants (ETPs) at affordable costs. The major drawback of this technique is the amount of waste generated in the form of biological sludge that grows at the expense of the assimilated food, which is rich in pathogens, organic micro pollutants, microplastics, partially and/or stabilized organic material, and toxic metals (depending on the influx of industrial sewage the station), and also contains nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, and potassium (Cieslik et al. [10], Husek et al. [11], and Sawska et al. [5]).

The phosphorus load in an ETP comes from the large quantity of powdered detergents, urine, and feces that are disposed of in domestic sewage. Thus, there are normally considerable concentrations of the element in the sludge formed (solid phase) and a smaller part in the liquid phase (treated effluent), with the concentration in the solid phase being approximately 70 to 98%. This is mainly because of the ability to incorporate phosphorus into solid biomass particles and the need for phosphorus consumption by the cells of microorganisms (Chrispim et al. [12], Eagle et al. [6], and Gerardi [13]).

The high generation of biological sludge provided by ETPs has become a problem in the vast majority of cases because the costs for disposal in landfills are very high. Owing to the high amount existing, it is estimated that the biggest cost for a waste water treatment plant (WWTP) in operation is the disposal and transportation of this biological sludge, which can reach up to 60% of operating expenses.

Although several studies have addressed the issue of the direct application of sanitized biological sludge—for example, in some crops as a soil conditioner, including improving soil compaction due to the presence of organic matter—its use is becoming increasingly restricted. With the technological advances in ETPs, it was verified in the analyses carried out that the sludge has presented a very large amount of pathogens, microplastics, and organic pollutants, and also the possibility of high concentrations of potentially toxic metals, making its use inadvisable, due to the possibility of environmental contamination. Furthermore, the phosphate present in excess STP sludge is present in high proportions in organic and non-apatite inorganic forms, which is a problem for plants since such forms can be absorbed directly in very limited quantities, or simply cannot be absorbed; thus, sewage sludge has low phosphorus bioavailability for plants when directly applied to crops (Hudcová et al. [14] and Li et al. [15]). A possible alternative for disposing of this high quantity of contaminated biological sludge is incineration. In this process, there is a considerable reduction in the volume, mass, and elimination of pathogens, microplastics, and organic micropollutants from the solid phase. Due to recent studies on the impacts of sludge contaminants on soil, many countries are gradually restricting their legislation regarding land application, with incineration increasingly being used as a method of sewage sludge disposal. The ash from incineration contains a large amount of concentrated nutrients, such as phosphorus, on the order of 14% to 25%. The inconvenience that can be observed is the maximization of the toxic metal contents if the sludge comes from an ETP that receives industrial sewage in a large part of the influent flow; therefore, it is necessary to use an additive in incineration to overcome this problem, for example, MgCl2 or CaCl2 (Husek et al. [11], Li et al. [15], Yang et al. [16], Kominko et al. [8], and Olasupo et al. [9]).

According to the National Mining Agency, Brazil is the fourth largest consumer of fertilizers based on nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Unfortunately, the majority of fertilizers used in Brazilian crops are imported products, as arable areas have increased every year; however, the production of phosphorus-based fertilizers has not increased in the same way. The use of phosphorus recovered from sewage sludge brings several benefits to sustainable development, such as extending natural phosphorus reserves, eliminating potentially contaminated sludge disposed in landfills, generating heat during burning, and reducing the operating cost of a WWTP due to expenses related to transportation and disposal of sludge, among others, such as meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2) in the areas of food security and sustainable agriculture (Eagle et al. [6], and Law and Pagilla [17]).

Therefore, this work is essential for the continuation of studies related to the transformation of NAIP (non-apatite) phosphorus into AP (apatite), as it innovatively investigates the transformation of NAIP phosphorus into AP using commercially pure quicklime containing 37% MgO, 54% CaO, and 12% other impurities. Furthermore, the study examines the behavior of toxic metals and nutrients after the application of commercial lime, contributing significantly to potential industrial applications.

2. Materials and Methods

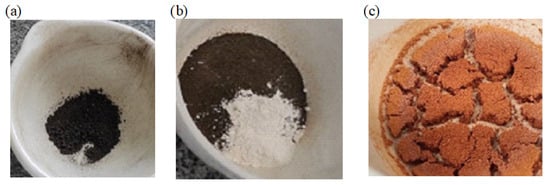

The sludge sample was collected in the last week of April 2021 at ETP-Pitico of SAAE (Serviço Autônomo de Água e Esgoto) in Sorocaba, São Paulo, Brazil (Figure 1a) and then frozen to stop microbiological activity. The ETP-Pitico treats mainly domestic sewage with a maximum design flow of 251 L/s, and the treatment is carried out using an activated sludge system by prolonged aeration with moisture removal through horizontal axis centrifuges. A moisture content of 79.5% was found in the sludge collected at the centrifuge outlet, as measured with a moisture meter (Quimis model Q533M). The moisture content found in the centrifuged sludge from ETP-Pitico is within what is expected from the literature, which predicts 77.5 to 81.5% water and 18 to 22.5% ST. The sludge was thawed for approximately 12 h at room temperature (Figure 1b) and placed in a drying and sterilization oven for 48 h at 105 °C to eliminate the water present in the sludge (Figure 1c). After drying, the sludge was stored in a desiccator to prevent moisture reabsorption (Li et al. [15,18]).

Figure 1.

The sludge sample. (a) Sample collected. (b) Sample after thawing. (c) Dry sample.

2.1. Sample Preparation and Calcination

The sludge removed from the desiccator was crushed and passed through a 500 µm particle size sieve. The sludge was then placed in porcelain crucibles (Figure 2a) with a mass varying between 6 and 15 gr, and calcined in a muffle furnace at the chosen temperatures, with and without the commercial quicklime additive. For calcination without lime, temperatures from 650 °C to 1050 °C were chosen, and in the treatment with lime, three intermediate temperatures were chosen—650, 750, and 950 °C—in relation to treatments without commercial quicklime. The calcination temperatures used are listed in Table 1. In the samples with lime, the proportions of lime weight in relation to the weight of sludge were chosen as 3, 6, and 12%, homogenized (Figure 2b) to investigate the conversion rate of non-apatite inorganic phosphorus (NAIP) into apatite phosphorus (AP). The samples were left for 1 h in a muffle furnace at the defined temperatures after the temperature was reached. The muffle does not allow adjustment of the heating rate; however, it starts at a heating rate of 22.8 °C/min from 0 to 10 min, and then from 10 min onward it stabilizes at 4.8 °C/min (Figure 2c). The average mass loss for each calcination temperature was in the range of 70%.

Figure 2.

The sludge sample. (a) Crushed dry sludge. (b) Added quicklime (without homogenization). (c) Ash obtained after calcination.

Table 1.

Temperatures used in sludge calcination and % lime per sample weight.

2.2. Sample Characterization

The amount of P in the forms apatite phosphorus, non-apatite inorganic phosphorus, and total phosphorus (TP) was determined using the spectrophotometer colorimetric method. In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM-EDX) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) were performed.

2.2.1. Phosphorus Extraction and Quantification

To obtain the P fractions, pulverized samples of dry sludge and ash with/without additives were subjected to acid and basic extraction processes. All analyses were performed in triplicate, and the results obtained had a relative standard deviation of less than 1%. For the dry sludge sample, the organic phosphorus (OP) fraction was also analyzed, which was chemically linked to organic compounds. The non-apatite inorganic phosphorus fraction consists of the Mn/Al/Fe-P compounds, apatite phosphorus fraction, Ca/Mg-P compounds, and total phosphorus the sum of all fractions. The harmonized Standards, Measurements, and Testing (SMT) protocol was used, as summarized in Pardo et al. [19] (Figure 1) and Ruban et al. [20] (Figure 2). Pre-digestion was not carried out in the TP of the harmonized protocol for the analysis of calcined sludge (ash), with direct extraction being carried out with 20 mL of HCl 3.5 mol/L since there was no organic matter to digest in the ash. Ethik Tecnology’s Dubnoff 304 TPA bath equipment (Ethik Technology, Sao Paulo, Brazil) was used with reciprocal agitation for acidic/basic extraction of P, which was recovered in the form of PO43− (phosphate). The extraction time was 20 h at 25 °C and a stirring speed of 220 rpm.

Total phosphorus—The acidic extract of TP (HCl 3.5 mol/L) and the residue were placed in Falcon tubes for centrifugation for 12 min at 3000 rpm to separate the residue from the extract and enable color analysis in a spectrophotometer of the liquid phase (TP).

Non-apatite inorganic phosphorus—The basic NAIP extract (NaOH 1.0 mol/L) and the residue were separated by filtration through medium filter paper, with the residue carrying the AP fraction being retained in the filter, and the liquid collected in the beaker, the extract NAIP. Ten milliliters of NAIP extract was discarded, and the remaining 10 mL was neutralized with 4 mL of HCl 3.5 mol/L. The NAIP extract was then centrifuged to extract the supernatant for color analysis using a spectrophotometer.

Phosphorus apatite—The acid extract of AP (HCl 1.0 mol/L) with the residue was placed in Falcon tubes and centrifuged for 12 min at 3000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected for color analysis.

P quantification was carried out using the Vanadomolybdophosphoric Acid spectrophotometric method described in the manual of official analytical methods for fertilizers and correctives of the Ministry of Agriculture, Supply and Livestock of Brazil, using at Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). From the concentrated solution of 500 mg/L of KH2PO4 (Monopotassium phosphate), dilutions were made to create an analytical curve of absorbance (ABS) and concentration, with 10 points chosen to guarantee greater precision of the method [21]. When carrying out the analysis on the spectrophotometer, from the dry/calcined sludge extract, the concentration of P (mg/g) was obtained through PO43− (mg/L), and the content of phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5).

2.2.2. Metal Analysis

The method used for digestion and extraction was described by Melo and Silva [22], with DMF (digestion in a muffle furnace), with adjustments. The pre-digestion step at 550 °C for 2 h was eliminated from the ash samples, as they were calcined at a minimum temperature of 650 °C. The dry sludge and ash samples were crushed until they reached 250 µm, for a higher contact area during solubilization.

To carry out multi-element analysis of 15 metals (potentially toxic and nutrients) by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), multi-element standards were read according to spectral lines, and the respective analytical analysis curves were prepared for each, one with low concentration and the other with high concentration, where seven points were chosen for each calibration curve. All data were acquired in triplicate, similarly to samples P, maintaining the same precision error with a relative standard deviation of less than 1%.

3. Results

3.1. Phosphorus Analysis

3.1.1. Dry Sludge

As shown in Table 2, the amount of TP, 25.66 mg/g, found in the dry sludge was quite similar to the amounts reported by Bairq et al. [23] and Li et al. [15], which were 25.29 and 25.68 mg/g, respectively. The values obtained in the phosphorus fractions demonstrated that more than half of the phosphorus content of the sludge was in the form of NAIP (Al/Fe/Mn-P) and OP (organic phosphorus) compounds, which have low bioavailability for plants, whereas the fraction AP (Ca/Mg-P), the most important because of the possibility of being directly absorbed by plants, is present in small quantities. Previous studies by Li et al. [15] and Li et al. [18] also confirmed this trend of low AP values in the analyzed sewage sludge, with approximately 2.5 mg/g of the AP fraction, which is still approximately 1/3 lower than the value found in this study.

Table 2.

Phosphorus results obtained from the spectrophotometer.

3.1.2. Calcined Sludge

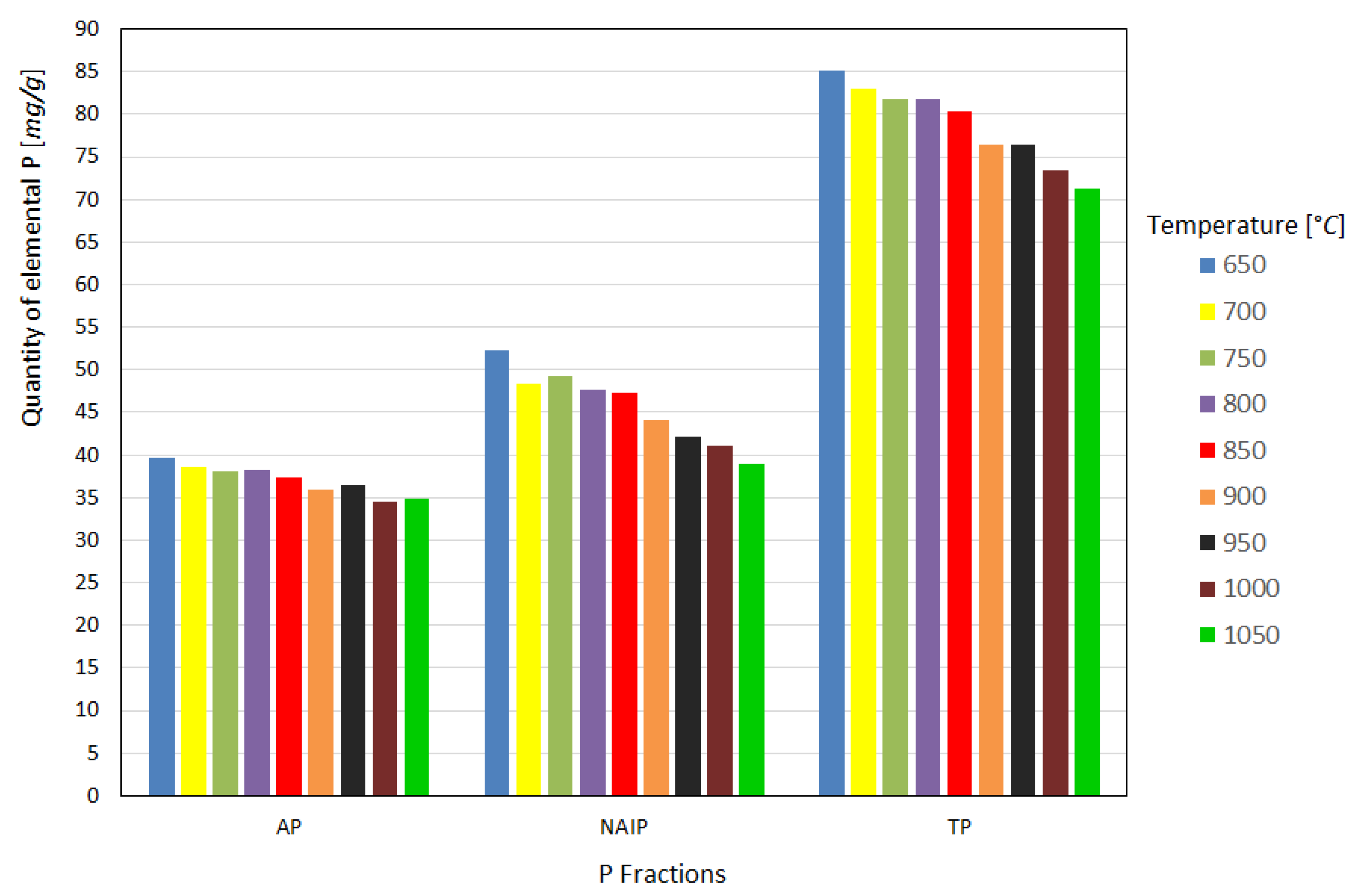

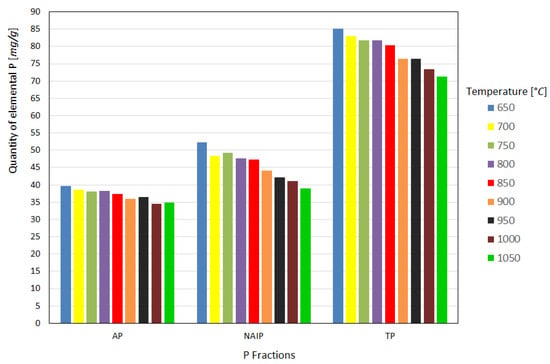

After analysis in the spectrophotometer, the elemental phosphorus content in the ash was obtained, as shown in Figure 3, for the different temperatures studied. Analyzing the results regarding the P fractions in the ash, it is possible to verify that as the calcination temperature increases, there is a substantial loss of recovery of the NAIP fraction and a slight loss of AP, implying a reduction in the TP fraction, but this behavior becomes more significant from 850 °C onward in the analyzed samples. It is also noticeable that the AP fraction has a much lower tendency to volatilize during the sludge-burning process at the different temperatures studied, as reported in previous studies, which is highly desirable from the point of view of reusing ash in agriculture [15,18,23].

Figure 3.

Quantity of elemental P recovered from the fractions as a function of the heat treatment temperature.

The results obtained for the fractions presented a certain disagreement with the findings of Li et al. [15,18], who showed that at high temperatures, similar to that used in this work, there is a conversion of a large part of the NAIP fraction into AP, and that as the temperature increases up to the limit of 900 °C there is a slight increase in the TP fraction in the ashes.

The difference from the work of Li et al. [15] can occur, for example, when using a fluidized bed furnace, which has a highly oxidizing atmosphere caused by the abundance of oxygen gas, or unlike the laboratory muffle furnace used, which does not have an air injection system. Thus, we tend to have a less oxidizing atmosphere. Han et al. [24] tested both an inert nitrogen atmosphere and an air-oxidizing atmosphere in their sludge heat treatment experiments and found that the inert atmosphere greatly favors the loss of phosphorus by volatilization compared to the oxidizing atmosphere. Therefore, it is assumed that the more oxidizing the atmosphere inside the furnace, the greater the quantity of phosphorus that can be retained in the ash. In addition, Li et al. [15] observed there was no loss of fly ash due to the furnace’s capture and retention system, which found around 6% of the sample’s total phosphorus retained in this portion of the ash.

Regarding the findings of Li et al. [18], despite using identical calcination conditions, the pulverized dry sludge samples were 150 µm in diameter, whereas in this work a maximum diameter of 500 µm was used. According to Li et al. [15], the smaller the particle size during calcination, the greater the favorability of the NAIP to the AP transformation mechanism because of the greater contact area between the particles.

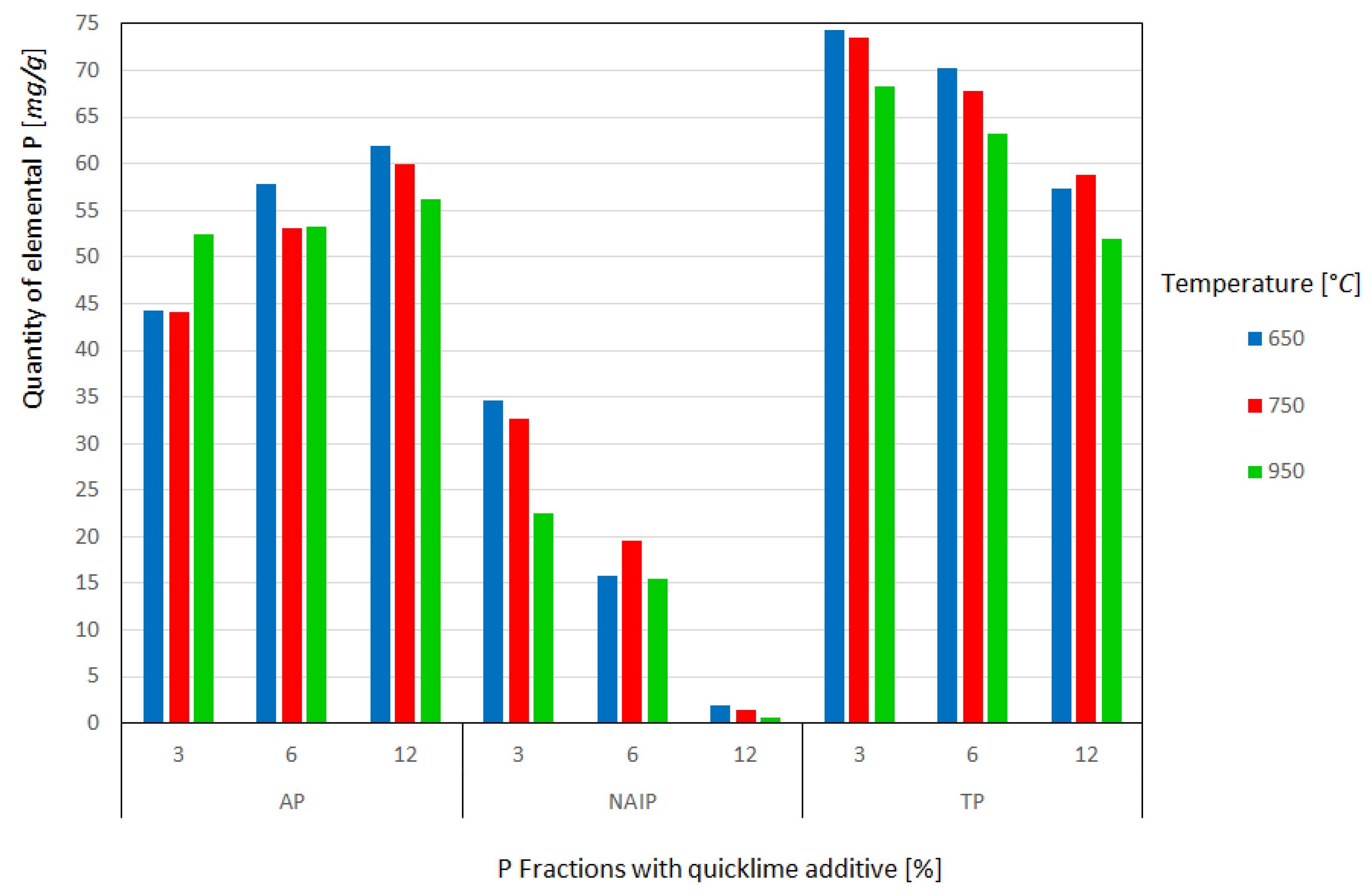

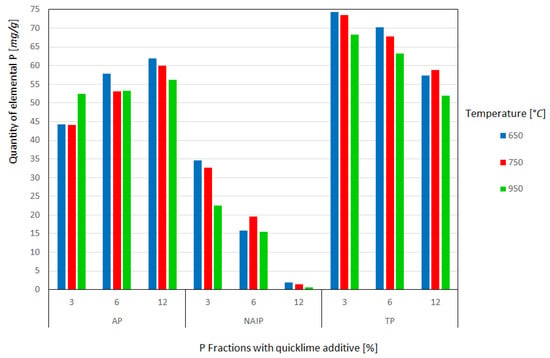

3.1.3. Sludge Calcined with Commercial Lime

The results for elemental phosphorus at each temperature and the respective amounts of lime are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that the introduction of commercial CaO causes the transformation of the NAIP phase into AP even at the lowest temperature of 650 °C with 3% additive. The AP content recovered at this temperature without the addition of the additive was approximately 40 mg/g and with 3% almost 45 mg/g, that is, there was a gain of approximately 11% in phosphorus apatite content. Li et al. [15,18] observed identical trends in their experiments but used an additive CaO of analytical purity. The highest AP content was obtained at a temperature of 650 °C with 12% of additive, around 62 mg/g, thus there is an enrichment of approximately 35% of the fraction in the ash, while at temperatures of 750 and 950 °C it is notable a small reduction in the AP fraction was observed, demonstrating that it is more stable and less subject to volatilization losses, as described by Li et al. [15]. However, a slight increase in the content of the AP mineral phase with increasing temperature and maintaining the additive proportion was observed. These discrepancies in the results can be explained by the reasons mentioned before and mainly by the use of analytical purity CaO, unlike this work, which used commercial purity CaO with 37% MgO and 54% CaO in its composition.

Figure 4.

Quantity of elemental P recovered from the fractions as a function of the heat treatment temperature and quantity of quicklime additive.

It is also evident that the conversion of NAIP to AP is dependent on the temperature and amount of additive added; however, this dependence has been shown to have a greater impact on the amount of additive than on temperature. For example, at a constant 650 °C and varying the additive (%) between 3, 6, and 12%, the recovered AP content started at approximately 45 mg/g at 3%, reaching approximately 62 mg/g in 12%. In addition, at high temperatures such as 950 °C it is not possible to obtain the same amounts of AP at lower temperatures, even by increasing the amount of additive. This behavior suggests greater volatilization of the AP phase at 950 °C, probably due to the high concentration of MgO in the additive.

In the NAIP fraction, high dependence on the additive for conversion to AP was clearly observed. By analyzing the temperature of 650 °C and varying the weight percentage of commercial CaO by 3, 6, and 12, it was verified that the NAIP content starts from approximately 35 mg/g at 3% to approximately 2 mg/g at 12%, which demonstrates the high conversion of NAIP to AP and greater volatilization of NAIP, as cited by Li et al. [15] and Li et al. [18]. The influence of temperature on the conversion of NAIP to AP was reduced, corroborating the formation of the AP phase. There was a significant and beneficial decrease in the NAIP phase, in the experiments with 3, 6, and 12% in weight percentage of commercial CaO: very little of the NAIP phase remained, and the values did not exceed 2 mg/g, demonstrating that the addition of commercial lime was extremely viable for NAIP to AP phase conversion.

According to the chemical reactions presented by Li et al. [18], in the transformation of aluminum NAIP phases into calcium AP at different temperatures, calcium pyrophosphate and calcium phosphate are formed in the products, which are calcium AP and the consumption of aluminum phosphate and phosphite NAIP. In the case of the transformation of iron NAIP phases into calcium AP, the consumption of iron NAIP results in calcium phosphate and hypophosphate products that are AP. According to Li et al. [18], during the calcination/incineration process using CaO as an additive, several chemical reactions occur that transform NAIP phosphorus into AP, as follows:

Aluminum NAIP to calcium AP:

Iron NAIP to calcium AP:

Considering that phosphorus compounds containing magnesium are also apatites, and that magnesium belongs to the same family as calcium in the periodic table, similar reactions are expected to occur, leading to the formation of magnesium-containing apatites.

For the TP phase, there was a drop in the TP content in relation to the condition without additive, proportional to the percentage of weight of commercial lime added to the sludge before calcination; this drop presented values of the order of up to 30% for the three temperatures investigated with the maximum percentage of 12% lime added. Such complications may be related to the use of commercial lime and the consequent greater volatilization of the AP and NAIP phases, contributing to the decrease in TP. This loss from the point of view of agronomic use is not desirable due to the lower P content per unit mass of ash.

The percentages of P2O5 obtained for the different temperatures and additive proportions studied are presented in Table 3, and it was found that the levels varied between 12% and 17%, with these values being slightly below the range proposed in the literature, which varies from 14% to 25%, as mentioned by Li et al. [15].

Table 3.

Content in % of phosphorus pentoxide as a function of temperature and quantity in % of commercial CaO.

The P2O5 values follow exactly the same trend previously demonstrated with elemental P. For example, for a constant % of additive of commercial quicklime, there is a decrease in the percentage of P2O5 with an increase in temperature, occurring in the same way when the temperature is maintained constant, and varying the weight % of commercial CaO.

3.2. Analysis of Potentially Toxic Metals and Nutrients

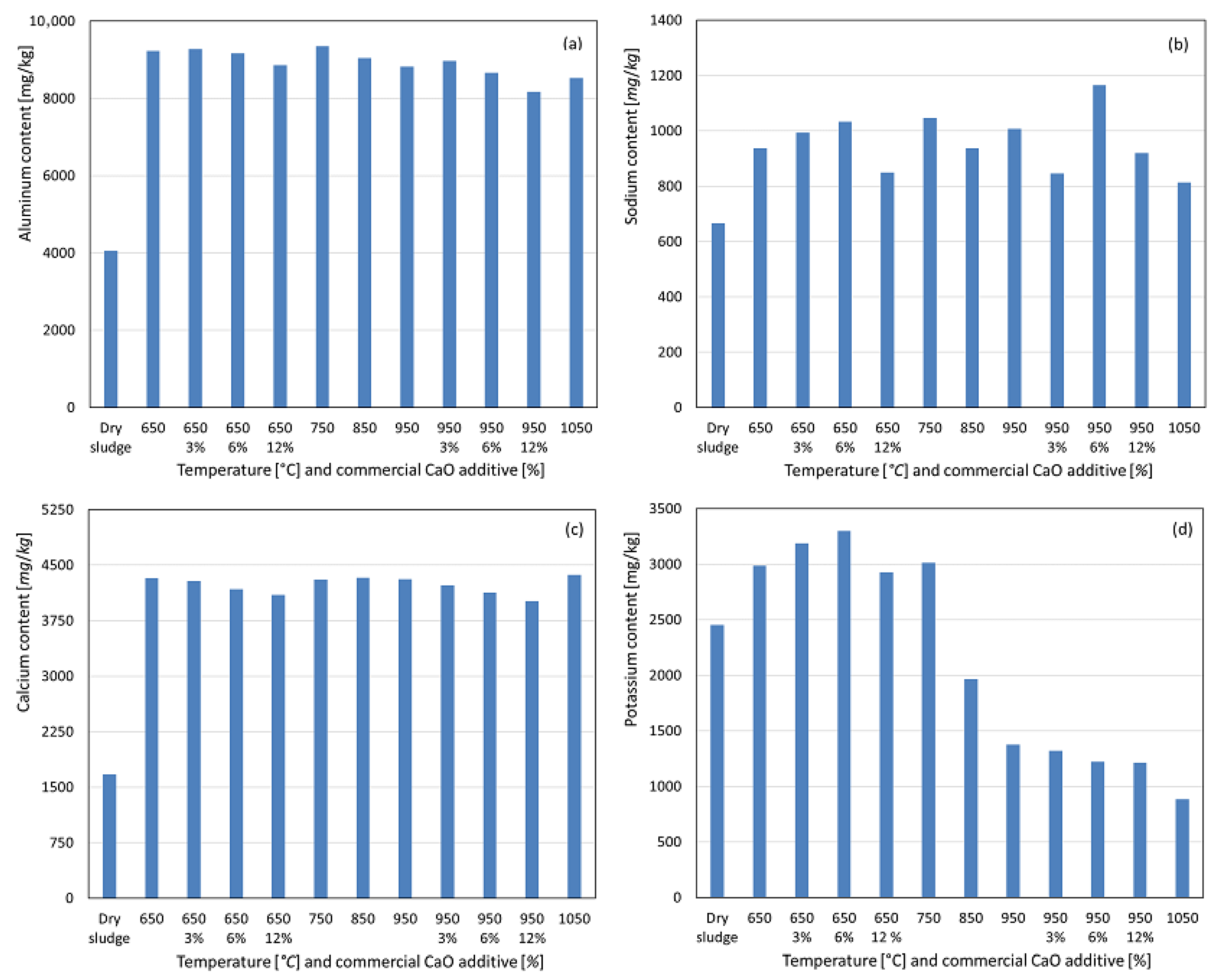

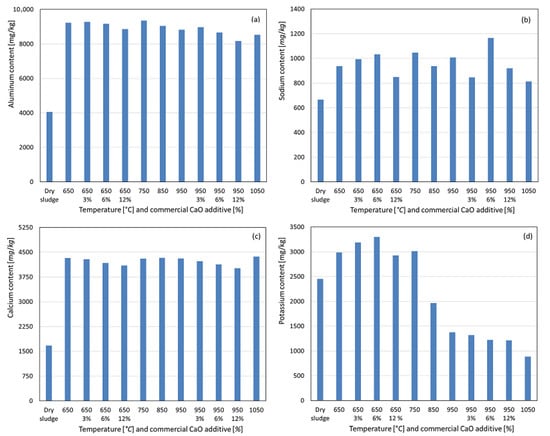

The contents of the different metals obtained at different calcination temperatures and percentage of commercial CaO additives are presented and discussed in the following section. The metals analyzed were aluminum, sodium, calcium, potassium, iron, magnesium, copper, zinc, molybdenum, nickel, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, and barium.

For aluminum, calcination at 650 °C resulted in a significant mass loss of the initial sludge due to volatilization, leading to a concentration of the element in the resulting ashes, as observed in Figure 5a. In the absence of the additive, a slight decrease in Al content was observed with increasing temperature, suggesting a greater susceptibility of the non-apatite inorganic phosphorus phase, potentially P-Al, to volatilization, as reported by Li et al. [15,18] and Bairq et al. [23]. At temperatures between 650 °C and 950 °C, with additive weight percentages of 3%, 6%, and 12%, this trend was more pronounced, indicating that aluminum may be partially substituted by calcium and/or magnesium in the apatite phase, with residual aluminum potentially volatilized. For sodium, a similar concentration trend was observed in the ash post incineration, albeit less pronounced, as shown in Figure 5b. Without the additive, the sodium content increased up to 750 °C, which was likely due to the formation of acid-soluble compounds or the release of sodium bound to organic matter after combustion. Beyond 750 °C, the sodium content decreased, likely due to volatilization, as sodium has a boiling point of approximately 883 °C, within the temperature range studied. With the additive, enhanced sodium fixation was observed at 750 °C and 950 °C for 3% and 6% additive conditions, resulting in higher recovery. However, at 12% additive, this effect was not observed, indicating a lower sodium recovery compared to the no-additive condition. Calcium exhibited a significant concentration in the ashes at 650 °C, with minimal variation at higher temperatures, and remained nearly constant. With the CaO additive in both temperature ranges, increasing the additive percentages led to a slightly lower calcium recovery. This suggests that the newly formed calcium apatite may be less soluble in concentrated nitric acid under these experimental conditions, contrary to expectations due to calcium addition. For potassium, a slight concentration increase was observed at 650 °C compared to dry sludge, remaining stable at 750 °C. From 850 °C onward, a significant decrease in potassium content was observed, likely due to volatilization, as potassium has a boiling point of approximately 758 °C. With the additive, enhanced potassium recovery was observed at 650 °C, with the highest recovery at 12% additive. However, at 950 °C, increasing the additive percentage slightly reduced the potassium content. Sodium, calcium, and potassium are considered agronomically beneficial parameters for soil fertilization because of their proven benefits to crops [25,26,27].

Figure 5.

Content recovered as a function of temperature variation and percentage by weight of commercial CaO additive. (a) Aluminum. (b) Sodium. (c) Calcium. (d) Potassium.

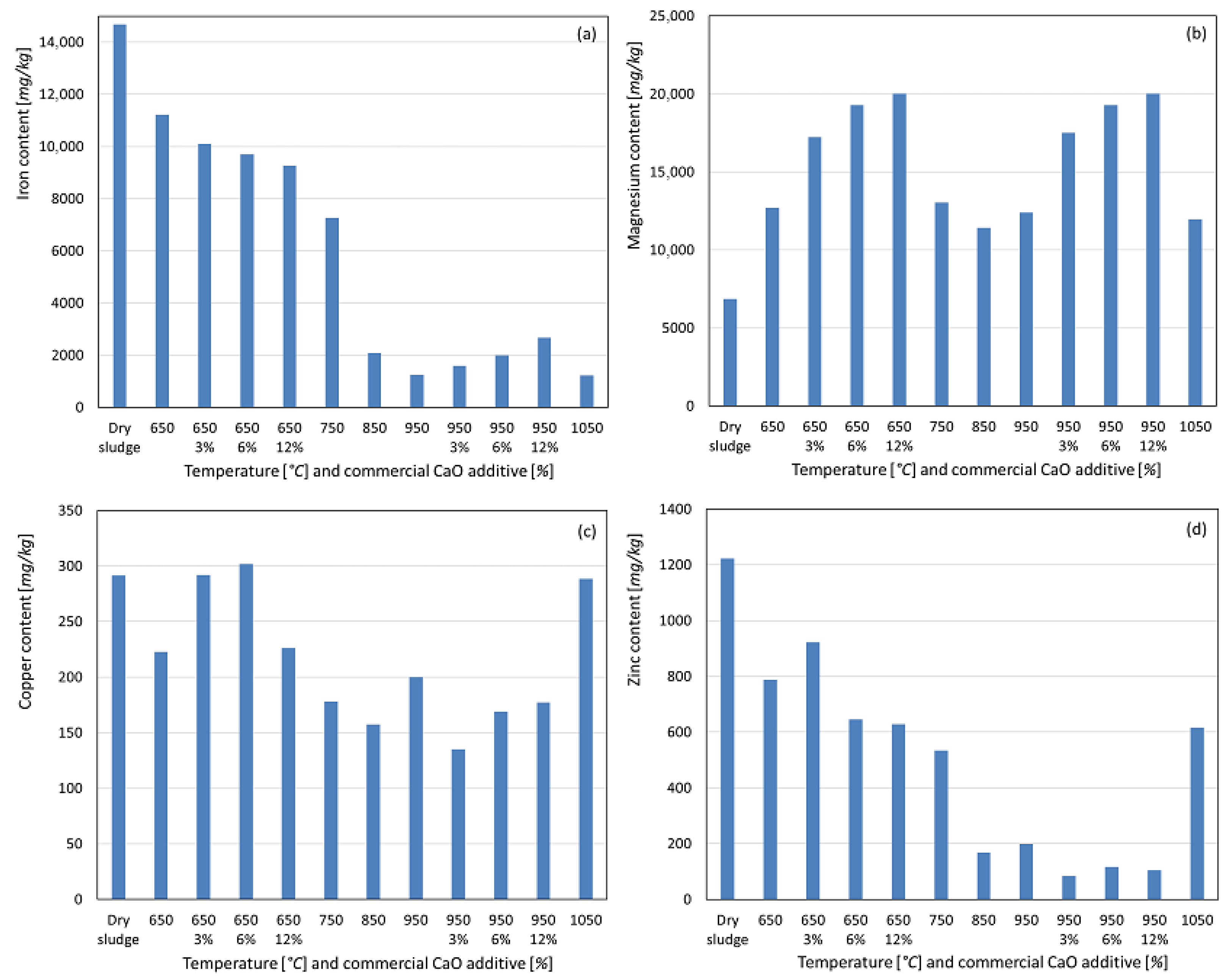

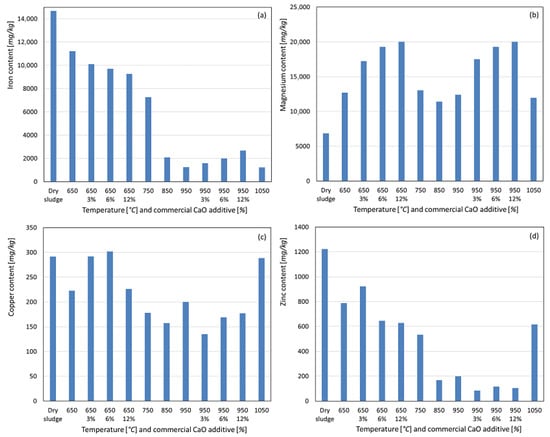

The iron concentration did not increase at the lowest calcination temperature, as shown in Figure 6a. The recovered iron content decreased with increasing temperature, with a sharp decline at 850 °C and a less pronounced decrease thereafter. As iron compounds typically have boiling points well above the studied temperature range, the reduced recovery is likely due to the formation of less acid-soluble oxides rather than volatilization. With the additive at 650 °C, increasing the additive percentages reduced the recovered iron content, whereas at 950 °C, a slight increase was observed with higher additive levels. For magnesium, a slight increase in concentration was noted at 650 °C compared to dry sludge, with minimal variation and a slight decrease at higher temperatures, as observed in Figure 6b. With the additive, higher CaO percentages increased magnesium recovery at both temperatures, likely due to the 37% MgO content in the commercial CaO and the potentially higher solubility of magnesium apatite in the acid used for solubilization. Magnesium is also considered an agronomically beneficial parameter for soil fertilization [25,26]. As shown in Figure 6c, no concentration increase was observed for copper at 650 °C; instead, a slight decrease in the recovered copper was noted, continuing at 750 °C and 850 °C. At 950 °C and 1050 °C, this trend was reversed, suggesting the formation of more acid-soluble copper compounds. With the additive, increasing percentages slightly increased the copper recovery at 650 °C and 950 °C compared to the no-additive condition. For zinc, no concentration increase was observed at 650 °C compared to dry sludge (see Figure 6d), with a significant decrease occurring up to 950 °C. At 1050 °C, zinc recovery increased slightly but remained below the 650 °C level, suggesting partial volatilization of metallic zinc or its compounds (boiling point 907 °C) and the formation of more acid-soluble compounds at 1050 °C. With the additive, increasing percentages reduced zinc recovery at both temperatures, indicating enhanced volatilization or formation of less acid-soluble compounds. Copper and zinc have maximum limits of 1500 mg kg−1 and 2800 mg kg−1, respectively, for sewage sludge used in soil fertilization, and the concentrations in the ashes were below these Brazilian legislative limits [25,26].

Figure 6.

Content recovered as a function of temperature variation and percentage by weight of commercial CaO additive. (a) Iron. (b) Magnesium. (c) Copper. (d) Zinc.

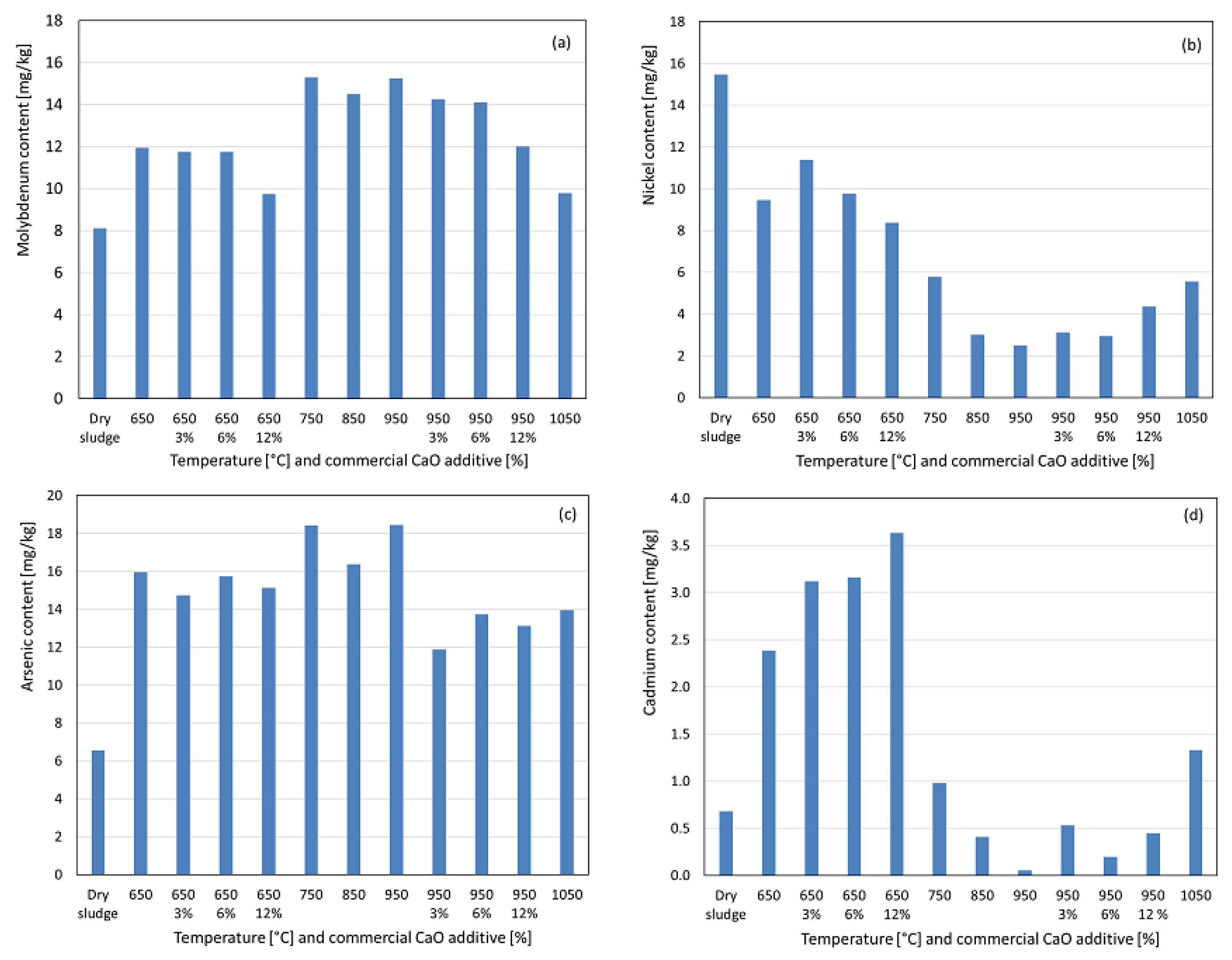

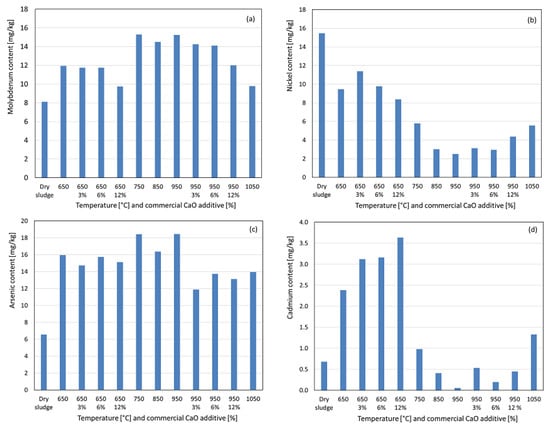

Molybdenum exhibited a concentration at 650 °C, with a pronounced increase at 750 °C, likely due to the elimination of residual organic matter bound to the metal or the formation of more acid-soluble compounds. As observed in Figure 7a, the concentrations remained relatively stable at subsequent temperatures until a significant decrease at 1050 °C, approaching dry sludge levels, suggesting the formation of less acid-soluble compounds. With 3% and 6% additives, no significant impact on molybdenum recovery was observed compared to the no-additive condition. However, at 12% additive, the reduced recovery indicated increased insolubility or the formation of more volatile compounds. In Figure 7b, we can observe that for nickel, no concentration increase was observed at 650 °C; instead, the recovered nickel decreased by nearly half compared to dry sludge, continuing to decline up to 950 °C, suggesting the formation of less acid-soluble compounds, as nickel and its compounds have boiling points well above the studied range, reducing the likelihood of volatilization losses. At 1050 °C, a significant increase in the recovered nickel was observed, approaching 750 °C levels, indicating the formation of more acid-soluble compounds. With the additive at 650 °C, increasing percentages reduced nickel recovery, suggesting less acid-soluble compounds, whereas at 950 °C, a slight increase in recovery with higher additive percentages suggested more soluble compounds. Molybdenum and nickel have maximum limits of 50 mg kg−1 and 420 mg kg−1, respectively, for sewage sludge used in soil fertilization, and their concentrations in the ashes were below these Brazilian legislative limits [25,26]. Arsenic exhibited a significant concentration from 650 °C to 950 °C, with a slight increase compared to the initial calcination condition, suggesting the formation of more acid-soluble compounds, as observed in Figure 7c. At 1050 °C, a considerable decrease in the recovered arsenic was observed, likely due to the low boiling point of elemental arsenic (613 °C), allowing for the volatilization of certain compounds or the formation of less acid-soluble compounds. With the addition of the additive at 650 °C, varying percentages had no significant impact on the recovered arsenic. At 950 °C, the additive reduced the recovered arsenic, particularly at 3%, with further reductions of 6% and 12% compared with the no-additive condition. For cadmium, a significant concentration was observed at 650 °C compared to dry sludge (see Figure 7d), which was attributed to a 70% mass loss during calcination–incineration. At 750 °C, 850 °C, and 950 °C, the recovered cadmium decreased progressively, increasing slightly at 1050 °C to levels similar to those in dry sludge. This behavior suggests partial volatilization owing to the low boiling point of cadmium (767 °C) and the formation of less acid-soluble compounds, with a reversal at 1050 °C favoring more soluble compounds. Arsenic and cadmium have maximum limits of 41 mg kg−1 and 39 mg kg−1, respectively, for sewage sludge used in soil fertilization, and their concentrations in the ashes were below these Brazilian legislative limits [25,26].

Figure 7.

Content recovered as a function of temperature variation and percentage by weight of commercial CaO additive. (a) Molybdenum. (b) Nickel. (c) Arsenic. (d) Cadmium.

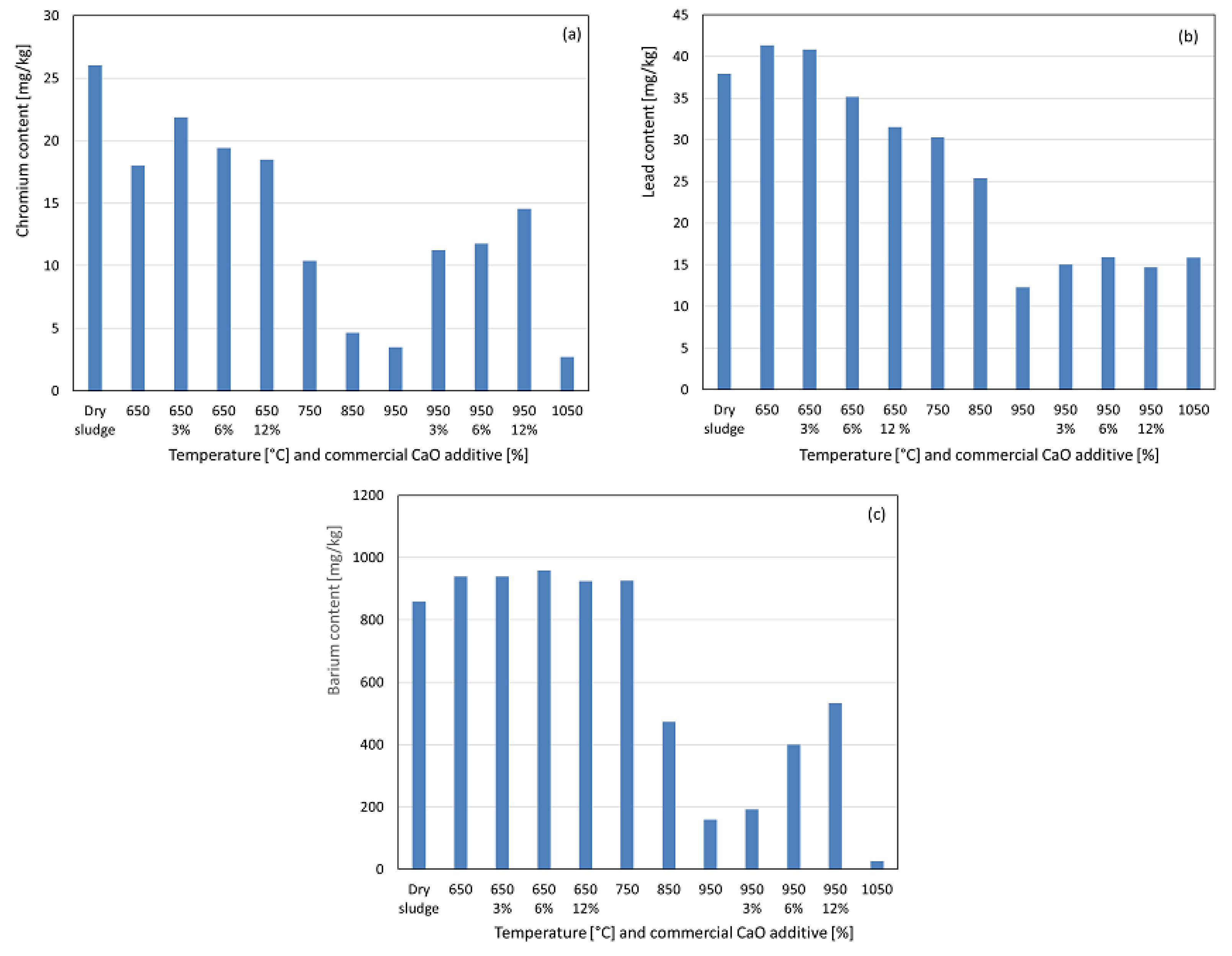

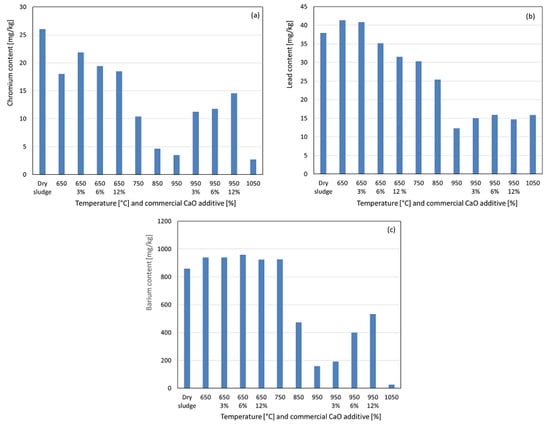

In Figure 8a, it can observed that chromium showed no concentration increase at 650 °C. This slight decrease in the recovered chromium indicates the possible formation of less acid-soluble compounds after significant organic matter elimination. This trend persisted up to 1050 °C, resulting in a very low recovery of chromium at the highest temperature. The formation of less acid-soluble compounds is more likely than significant volatilization losses, as chromium and its compounds have high boiling points well above the studied range. With the additive at 650 °C, the recovered chromium increased by 3%, but the recovery decreased by 6% and 12% compared to the no-additive condition. At 950 °C, the additive significantly increased the recovered chromium, particularly at 3%, with that trend continuing less intensely at 6% and 12%, suggesting the formation of more acid-soluble chromium compounds. For lead, a slight concentration was observed at 650 °C (see Figure 8b), followed by a significant decrease up to 950 °C, likely due to the formation of less acid-soluble compounds, as volatilization is unlikely to occur given the high boiling points of lead and its compounds. With the additive at 650 °C, 3% had no effect, but 6% and 12% reduced the recovered lead, suggesting less soluble compounds. At 950 °C, 3% slightly increased the recovered lead, with minimal changes at 6% and 12%, indicating a negligible influence on compound solubility. Barium exhibited a slight concentration at 650 °C after the significant elimination of organic matter, as observed in Figure 8c. At 750 °C, the recovered content remained stable, followed by a significant decrease from 850 °C to 1050 °C. This behavior is likely linked to the formation of less acid-soluble compounds, as barium and its compounds have boiling points well above the studied range, reducing the likelihood of volatilization losses. With the additive at 650 °C, minimal interference was observed across all percentages, with recovered values similar to those in the no-additive condition. At 950 °C, increasing the additive percentage significantly increased the recovered barium, indicating the formation of more acid-soluble compounds. Chromium, lead and barium have maximum limits of 1000 mg kg−1, 300 mg kg−1, and 1300 mg kg−1, respectively, for sewage sludge used in soil fertilization, and the concentrations in the ashes were below these Brazilian legislative limits [25,26].

Figure 8.

Content recovered as a function of temperature variation and percentage by weight of commercial CaO additive. (a) Chromium. (b) Lead. (c) Barium.

Overall, the commercial CaO additive generally increased the recovery of potentially toxic heavy metals such as barium, lead, chromium, and cadmium, for the range of studied weight percentages. These findings align with those of Han et al. [24], who reported that CaO enhances the metal retention in ash during combustion. Given the high boiling points of these metals and their compounds, CaO likely promotes greater solubility and bioavailability rather than solely preventing volatilization because only metal chlorides have boiling points below the maximum temperature studied. For potentially toxic micro-nutrients such as nickel, copper, magnesium, and iron, a similar effect was observed, particularly at 950 °C, when additives were used. However, this was not the case for molybdenum, zinc, potassium, calcium, sodium, and aluminum [28,29].

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

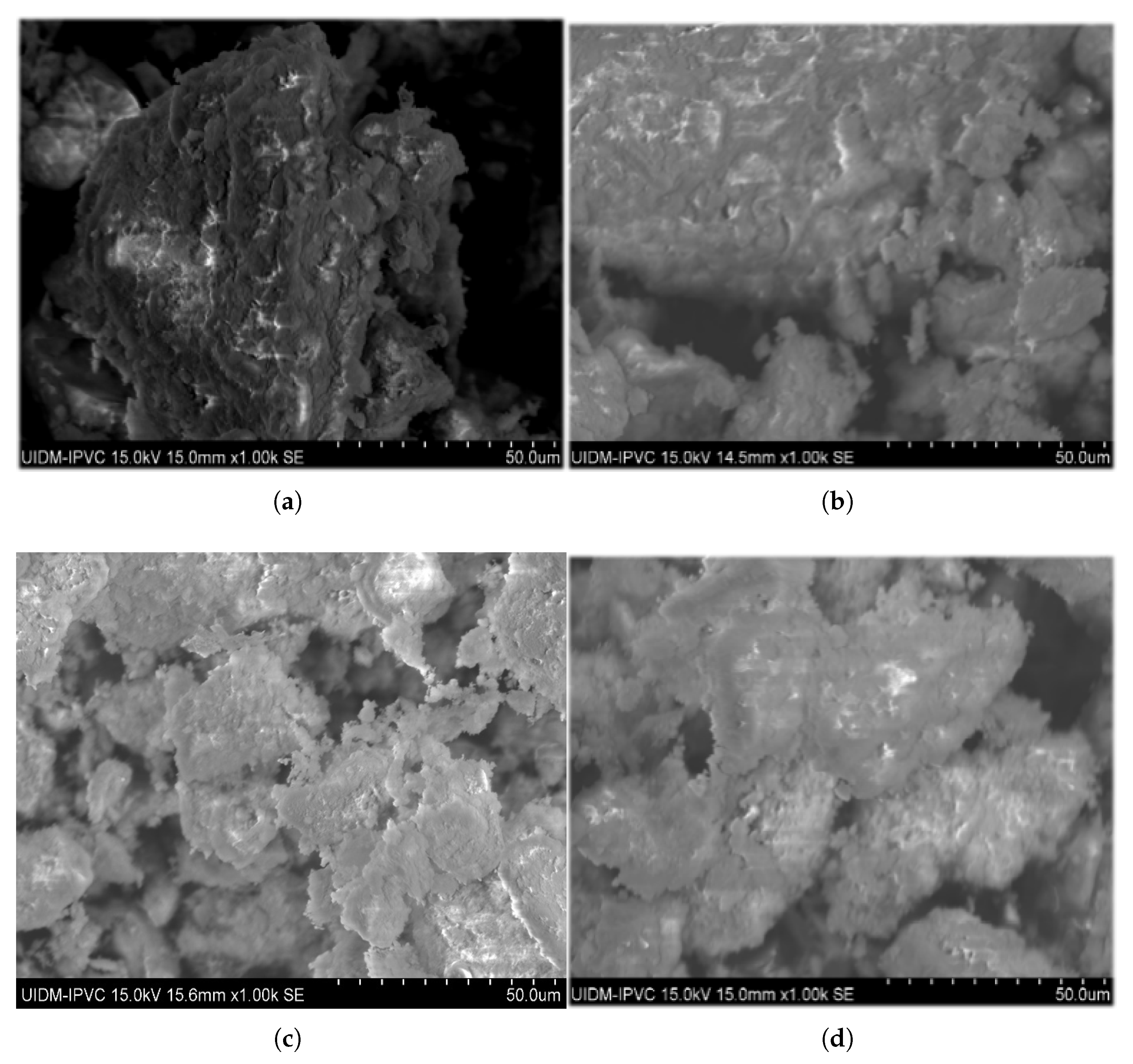

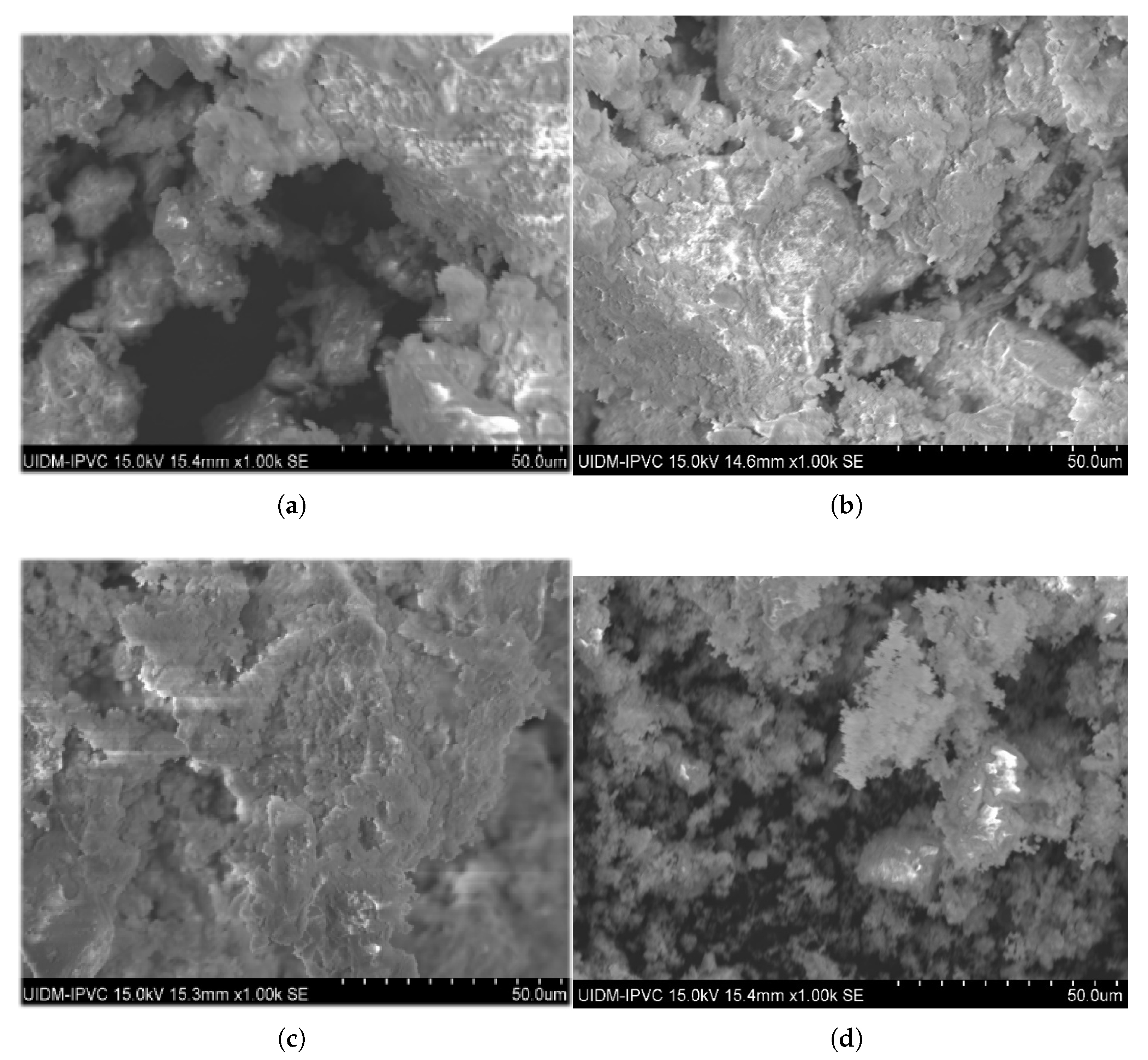

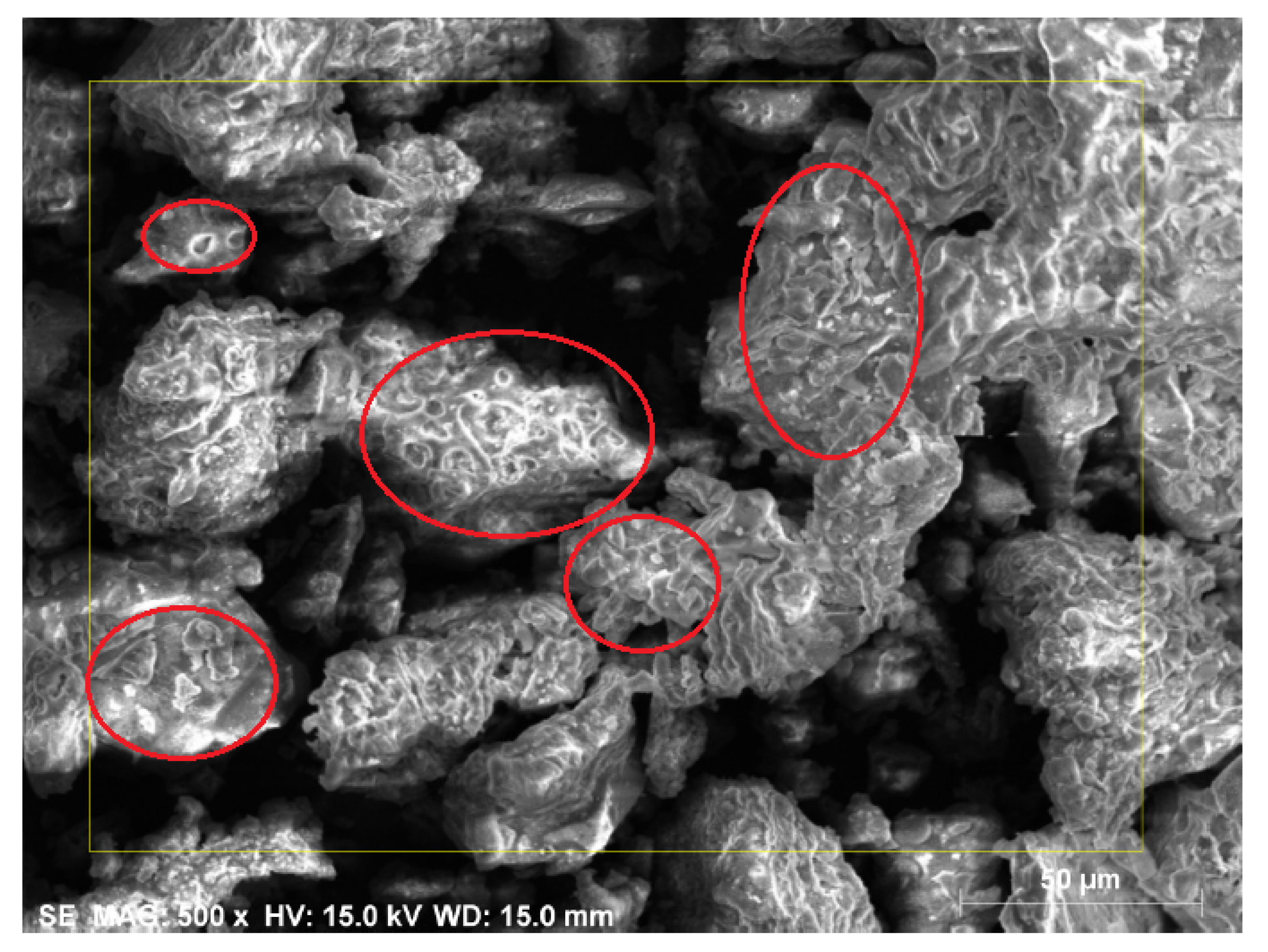

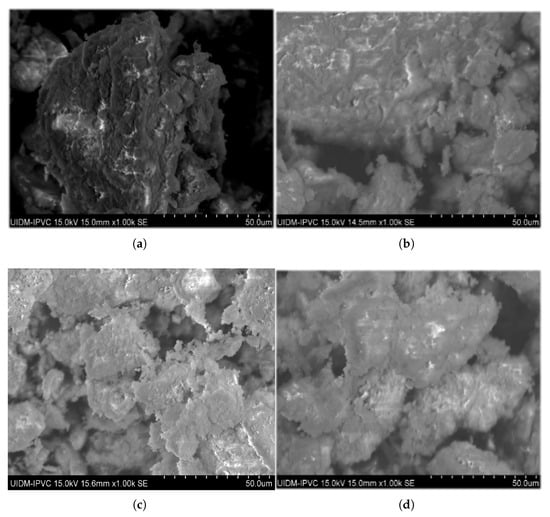

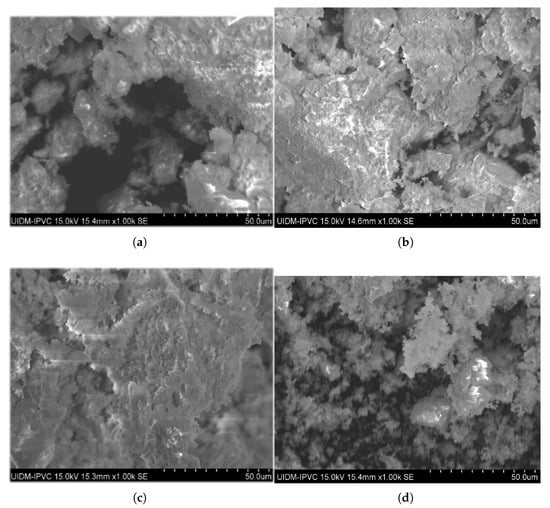

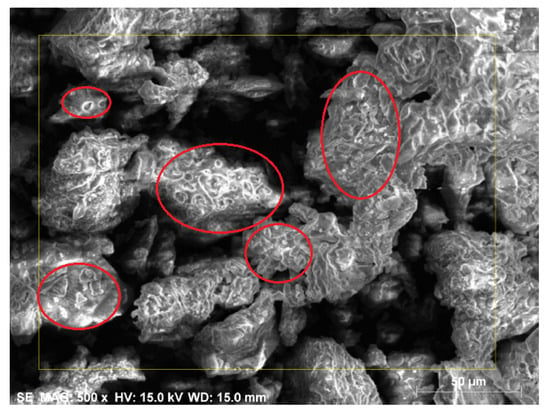

The surface morphology of the calcined sludge was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at magnifications of 1000 across the range of temperatures from 650 °C up to 1050 °C and different proportions of commercially pure CaO additive, as shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 9.

Micrographs of ashes after calcination at 650 °C during 1 h with percentage of commercial CaO additive. (a) 0%. (b) 3%. (c) 6%. (d) 12%.

Figure 10.

Micrographs of ashes after calcination at 950 °C during 1 h with percentage of commercial CaO additive. (a) 0%. (b) 3%. (c) 6%. (d) 12%.

Figure 11.

Micrographs of ashes after calcination at 1050 °C during 1 h without commercial CaO additive.

In the absence of the additive, the micrographs at 650 °C (Figure 9) reveal a highly porous grain surface, which progressively decreases with increasing calcination temperature. At 1050 °C (Figure 11), the grains appeared more agglomerated and rounded, with less porosity, as observed in the circled regions in the figure. These changes can be attributed to the gradual elimination of organic matter with rising temperature, volatilization of metals and their compounds with lower boiling points, and other processes such as dehydration, dehydroxylation, and decomposition of carbonates into oxides, leading to densification of calcinated sludge grains [30]. In addition, potential sintering was observed, which was characterized by reduced porosity and the formation of nearly non-porous crystals. Morais [31] reported similar sintering effects with greater clarity, likely due to a higher magnification (5000×) compared to the 1000× used in this study and a longer calcination time of 3 h versus 1 h, which may have influenced crystal formation.

When additives were used at 650 °C (Figure 9), the increase of percentage proportions (3%, 6%, and 12%) resulted in reduced porosity and apparent densification compared with the no-additive condition. At 950 °C (Figure 10), this effect was observed only for the 3% and 6% additive percentages; for the 12% additive, the calcinated material was finely pulverized with highly porous grains. The presence of non-reacted CaO and MgO particles in apatite formation likely adheres to the ash pores, smoothing the surface topography with increasing additive percentages. At 12% (Figure 10d), the excess non-reacted additive may have filled most pores, creating an appearance of increased porosity at this proportion and temperature.

3.4. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

Qualitative and semi-quantitative elemental analyses of the calcined samples were performed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) coupled with SEM, as presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Elemental atomic percentages in calcinated sludge ashes at various temperatures.

Table 5.

Elemental atomic percentages in calcinated sludge ashes at 650 °C with varying commercial CaO additive percentages.

Table 6.

Elemental atomic percentages in calcinated sludge ashes at 950 °C with varying commercial CaO additive percentages.

The analysis of the atomic percentages revealed minimal variation with increasing calcination temperature, with a slight increase in the detected quantities closer to 1050 °C, particularly for silicon and aluminum. This trend is likely due to the elimination of greater organic matter at higher temperatures, concentrating elements in a smaller surface area. Morais [31] reported carbon contents of 0.236% at 550 °C and 0.152% at 1010 °C in calcinated sludge from the Barueri WWTP, approaching near-zero at 1050 °C. Sulfur volatilization began at 550 °C, with near-zero percentages at 1000 °C, consistent with the non-detection of sulfur at 950 °C and 1050 °C in this study. However, trace sulfur may persist within the grain interior, which is undetected by surface-limited EDS analysis. Sulfur is considered an agronomically beneficial secondary macronutrient for soil fertilization [25,26,27].

At 650 °C with the additive, increasing the CaO percentages slightly reduced the atomic percentages of most elements, likely due to masking by non-reacted CaO that was not incorporated into phosphorus apatite. Aluminum showed a slight reduction, consistent with the partial volatilization of the NAIP aluminum phase, as discussed in Section 3.2. Sulfur exhibited a slight increase in atomic percentage with higher CaO levels, likely due to enhanced fixation in the ashes, as the commercial CaO used (San Francisco manufacturer) contained no sulfur. A significant increase in calcium and magnesium with higher CaO levels was expected, given the additive composition of 37% MgO and 54% CaO. The phosphorus atomic percentages decreased with increasing CaO, corroborating the volatilization losses discussed in Section 3.2.

At 950 °C, increasing CaO percentages resulted in a similar trend of reduced atomic percentages for most elements, which was attributed to masking by non-reacted CaO and MgO from apatite formation. This effect was pronounced for titanium, potassium, and sodium, with no atomic percentages detected at 12% CaO, although ICP-OES analysis confirmed their presence, highlighting the surface-limited nature of EDS. The calcium and magnesium concentrations increased with higher CaO levels, as expected from the additive composition. Phosphorus followed the same trend as at 650 °C, with greater reductions at 950 °C, particularly at 12% CaO, consistent with the significant phosphorus loss at this temperature and proportion, as demonstrated in Section 3.2.

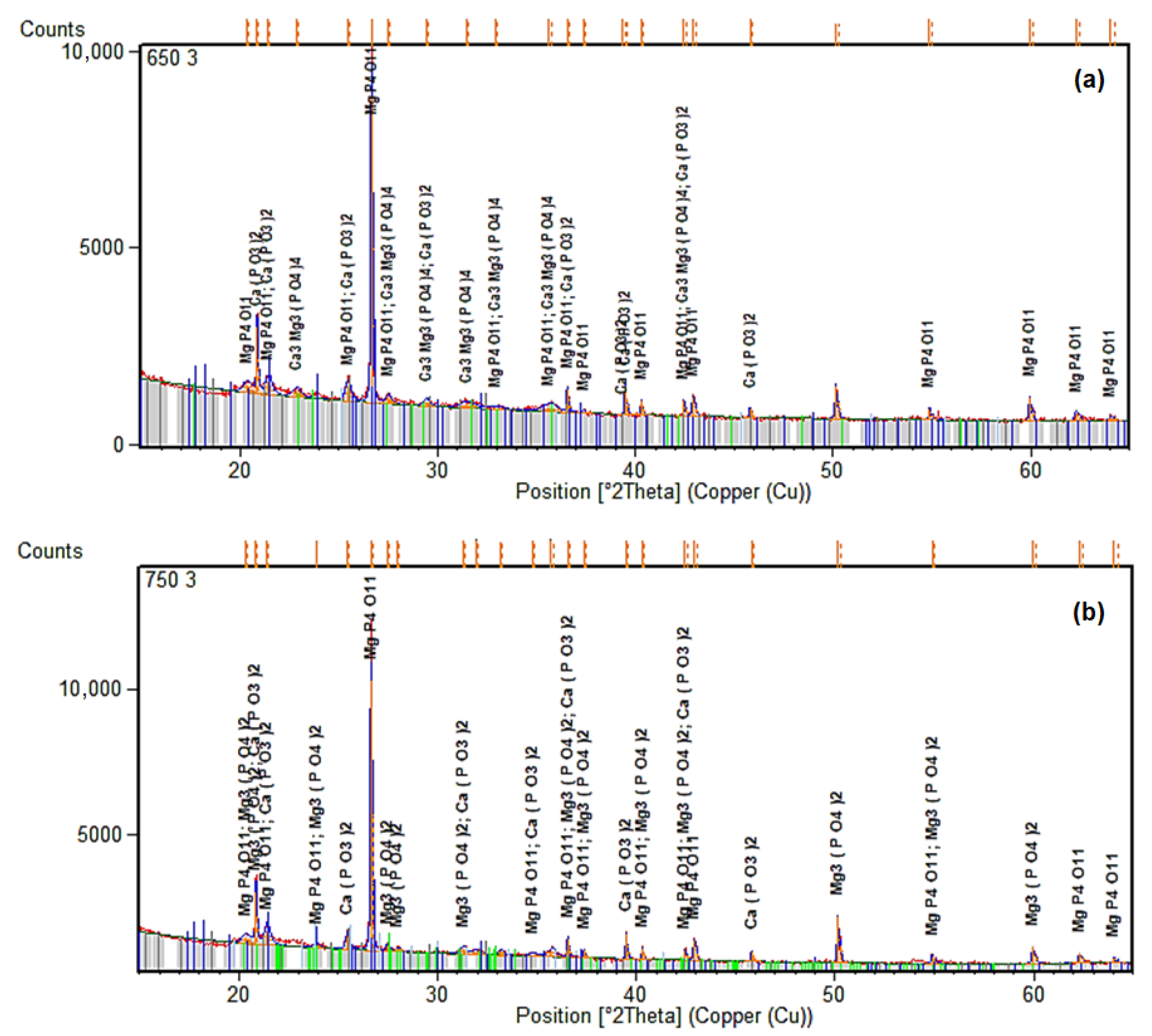

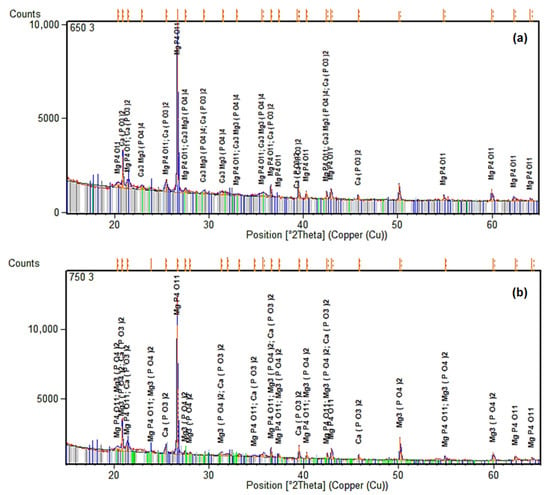

3.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The sewage sludge ashes were investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) to clarify the changes induced by thermal treatment and the addition of commercial quicklime (containing 54% CaO and 37% MgO). This analysis provides complementary evidence to the phosphorus recovery, confirming the conversion of non-apatite inorganic phosphorus (NAIP, primarily Al/Fe/Mn-P) to more bioavailable apatite phosphorus (AP, Ca/Mg-P).

Figure 12 presents the XRD patterns for ashes calcined at 650 °C and 750 °C with a 3% commercial CaO addition. These were chosen because of the higher AP recovery (up to about 45–50 mg/g) and a low TP loss (less than 10%), as shown by spectrophotometry. The patterns show that there are calcium–magnesium phosphate phases, including whitlockite (β-Ca3(PO4)2), which is structurally similar to apatite and may take in Mg2+ ions since the additive has a lot of MgO in it. Figure 12a shows that the whitlockite peaks are stronger than the quartz peaks at 650 °C. This suggests that phosphate minerals form more easily in less intense circumstances, where volatilization losses are reduced (as seen in Figure 4). At 750 °C (Figure 12b), however, there are fewer phosphate phases, but TP retention still high.

Figure 12.

XRD patterns of ashes after calcination at different temperatures with 3% of commercial CaO additive. (a) 650 °C. (b) 750 °C.

The phosphate peaks show that adding commercial CaO speeds up the interaction between NAIP and Ca2+ and Mg2+ to make stable apatite-like structures. This transformation is favored at temperatures around 650–750 °C, where CaO decomposes to provide reactive Ca2+, facilitating the substitution of Al/Fe-bound P with Ca/Mg-P bonds. The Mg incorporation stabilize the apatite phase against volatilization at higher temperatures, which is in line with the AP enrichment (up to 35% increase at 650 °C with 12% addition). These results confirm earlier research by Li et al. [15,18], which documented analogous NAIP-to-AP conversions with CaO in fluidized bed or muffle furnaces. However, using commercial CaO here adds MgO, which could make magnesium-substituted apatites (like ((Ca,Mg)5(PO4)3(OH)), which could make P more available in Brazil’s acidic soils. The SEM-EDX results support this evidence, demonstrating that the percentages of Ca and Mg went higher (up to 8.3% Ca and 5.7% Mg at 650 °C with 12% CaO), which means that phosphate minerals are becoming more concentrated on the surface. The XRD data show that calcining commercial CaO makes ashes that are high in bioavailable phosphate phases. These ashes can be used directly in agriculture or as a source of P fertilizer.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that calcination with commercially pure CaO effectively induces the conversion of non-apatite inorganic phosphorus to apatite phosphorus, enhancing the agronomic value of the resulting ash for phosphorus recycling or extraction for phosphate fertilizer production. The ashes from the Pitico WWTP exhibited low concentrations of potentially toxic metals, well below the limits set by the Brazilian legislation for sewage sludge application in agricultural soils [25,26], allowing direct soil application without additional treatment. The ash contained significant levels of primary macro-nutrients (phosphorus and potassium, with phosphorus as P2O5 ranging from 12% to 17%), secondary macro-nutrients (calcium, magnesium and sulfur), and essential micronutrients (copper, zinc, molybdenum and nickel) for crops. However, incineration at high temperatures (1050 °C without additives) induces sintering, potentially hindering nutrient release in the soil. Phosphorus recycling from sewage sludge ashes is highly promising, particularly with the expanding sanitation infrastructure in Brazil, which will increase sludge production. Current landfilling practices for most sludge are unsustainable due to limited landfill capacity and the loss of valuable nutrients, especially phosphorus, which faces projected scarcity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.M.; Methodology, J.B.G. and R.S.L.; Validation, L.C.M., J.B.G. and R.S.L.; Formal Analysis, J.B.G. and R.S.L.; Investigation, J.B.G.; Resources, L.C.M. and P.R.R.; Data Curation, J.B.G. and R.S.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.B.G., P.R.R. and A.M.A.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.M.A., A.H.R., L.C.M. and P.R.R.; Supervision, L.C.M.; Project Administration, L.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

A. M. Afonso acknowledges FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia for financial support through LA/P/0045/2020 (ALiCE), UIDB/00532 and UIDP/00532 (CEFT) funded by national funds through FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC).

Conflicts of Interest

No potential competing interests were reported by the authors.

References

- Cordell, D.; Drangert, J.; White, S. The story of phosphorus: Global food security and food for thought. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; White, S. Tracking phosphorus security: Indicators of phosphorus vulnerability in the global food system. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, H. Insight into chemical phosphate recovery from municipal wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.H.; Fraceto, L.F.; Carlos, V.M. Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade, 1st ed.; Grupo A: São Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sawska, K.; Gorazda, K.; Tarko, B.; Kominko, H. Triple superphosphate based on sewage sludge ash and chicken manure ash—production and agronomic usefulness. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, C.; Rechberger, H.; Krampe, J.; Zessner, M. Phosphorus recovery from municipal wastewater: An integrated comparative technological, environmental and economic assessment of P recovery technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 522–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.S.; Calvalcante, V.S.; Garcia, J.B.F.; Filho, H.G.; Morais, L.C.; Tonetti, A.L. Evaluation of the use of wastewater treated with Lemnas minor in bean yield and nutrition. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2022, 43, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominko, H.; Gorazda, K.; Wzorek, Z. Evaluation of the potential use of sewage sludge ash in phosphoric acid production and phosphorus recovery technologies. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 107054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasupo, A.; Ishola, B.; Ajiboye, T.O.; Esan, A.O.; Omenesa Idris, M.; Lawal, B.; Suah, F.B.M. Sewage sludge: A source of renewable energy and resources for circular bioeconomy. Chem. Eng. J. Green Sustain. 2026, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslik, B.; Konieczka, P. A review of phosphorus recovery methods at various steps of wastewater treatment and sewage sludge management. The concept of “no solid waste generation” and analytical methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1728–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husek, M.; Mosko, J.; Poherelý, M. Sewage sludge treatment methods and P-recovery possibilities: Current state-of-the-art. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrispim, M.C.; Sholz, M.; Nolasco, M.A. Phosphorus recovery from municipal wastewater treatment: Critical review of challenges and opportunities for developing countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerardi, M.H. Wastewater Bacteria; Wiley-Intersciense: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hudcová, H.; Vymazal, J.; Roskosný, M. Present restrictions of sewage sludge application in agriculture within the European Union. Soil Water Recearch 2019, 14, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Teng, W.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Cui, R.; Yang, T. Potential recovery of phosphorus during the fluidized bed incineration of sewage sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chen, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, W.; Xu, Y.; Qian, G. Phosphorus recovery from sewage sludge via incineration with chlorine-based additives. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.P.; Pagilla, K.R. A solution to the limited global phosphorus supply: Regionalization of phosphorus recovery from sewage sludge ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Teng, W.; Wang, W.; Yang, T. Transformation of apatite phosphorus and non-apatite inorganic phosphorus during incineration of sewage sludge. Chemosphere 2015, 141, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, P.; Sánchez, J.F.L.; Rauret, G. Relationships between phosphorus fractionation and major components in sediments using the SMT harmonized extraction procedure. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 376, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, V.; López-Sánchez, J.F.; Pardo, P.; Rauret, G.; Muntau, H.; Quevauviller, P. Harmonized protocol and certified reference material for the determination of extractable contents of phosphorus in freshwaters sediments. Fresenius’ J. Anal. Chem. 2001, 370, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA). 4500-p Phosphorus: Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, L.C.A.; SIlva, C.A. Influência de métodos de digestão e massa de amostra na recuperação de nutrientes em resíduos orgânicos. Quím. Nova 2008, 31, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairq, Z.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Sema, T.; Teng, W.; Kumar, S.; Liang, Z. New advancement perspectives of chloride additives on enhanced heavy metals removal and phosphorus fixation during thermal processing of sewage sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Fururuchi, M.; Kanchanaplya, P. The behavior of phosphorus and heavy metals in sewage sludge ashes. Int. J. Environ. E Pollut. 2009, 37, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CETESB. Aplicação de Lodo de Sistemas de Tratamento biolóGico de Efluentes líQuidos sanitáRios em Solo—Diretrizes e Critérios Para Projeto e Operação, 2nd ed.; Companhia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021; Norma téCnica P4.230.

- CONAMA. Define Critérios e Procedimentos, Para o Usoagrícola de Lodos de Esgoto Gerados em Estações Detratamento de Esgoto Sanitário e Seus Produtosderivados, e dá Outras Providências; Resolução 375, 29 de Agosto de 2006; Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2006.

- Malavolta, E.; Morais, M.F.; Júnior, J.L.; Malavolta, M. Micronutirentes e Metais Pesados—Essencialidade e Toxidez; Ciência, Agricultura e Sociedade; Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária: Brasília, Brazil, 2006; Chapter 4, pp. 117–154.

- Adam, C.; Peplinsk, B.; Michaelis, M.; Simon, F. Thermochemical treatment of sewage sludge ashes for phosphorus recovery. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, L.; Caneghem, J.V. Recovery of phosphorus from sewage sludge ash: Influence of chemical addition prior to incineration on ash mineralogy and related phosphorus and heavy metal extraction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.B.; França, S.C.A.; Braga, P.F.A. Tratamento de Minérios, 6th ed.; CETEM-MCTIC: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018.

- Morais, L.C. Caracterização, em Escala de Laboratório, do Produto Proveniente da Calcinação do Lodo de Esgoto Resultante do Tratamento de águas Residuárias. Ph.D. Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.