Operationalising the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in Life Cycle Assessment Ecolabelling: Exploring Indicator Selection Through Delphi Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How can circular economy principles support the development of a WEFE-Nexus-based indicator set, for a life-cycle-based ecolabelling scheme for pasta production?

- RQ2: In what ways can life-cycle-based instruments be adapted to operationalise the WEFE Nexus within business practices?

2. Materials and Methods

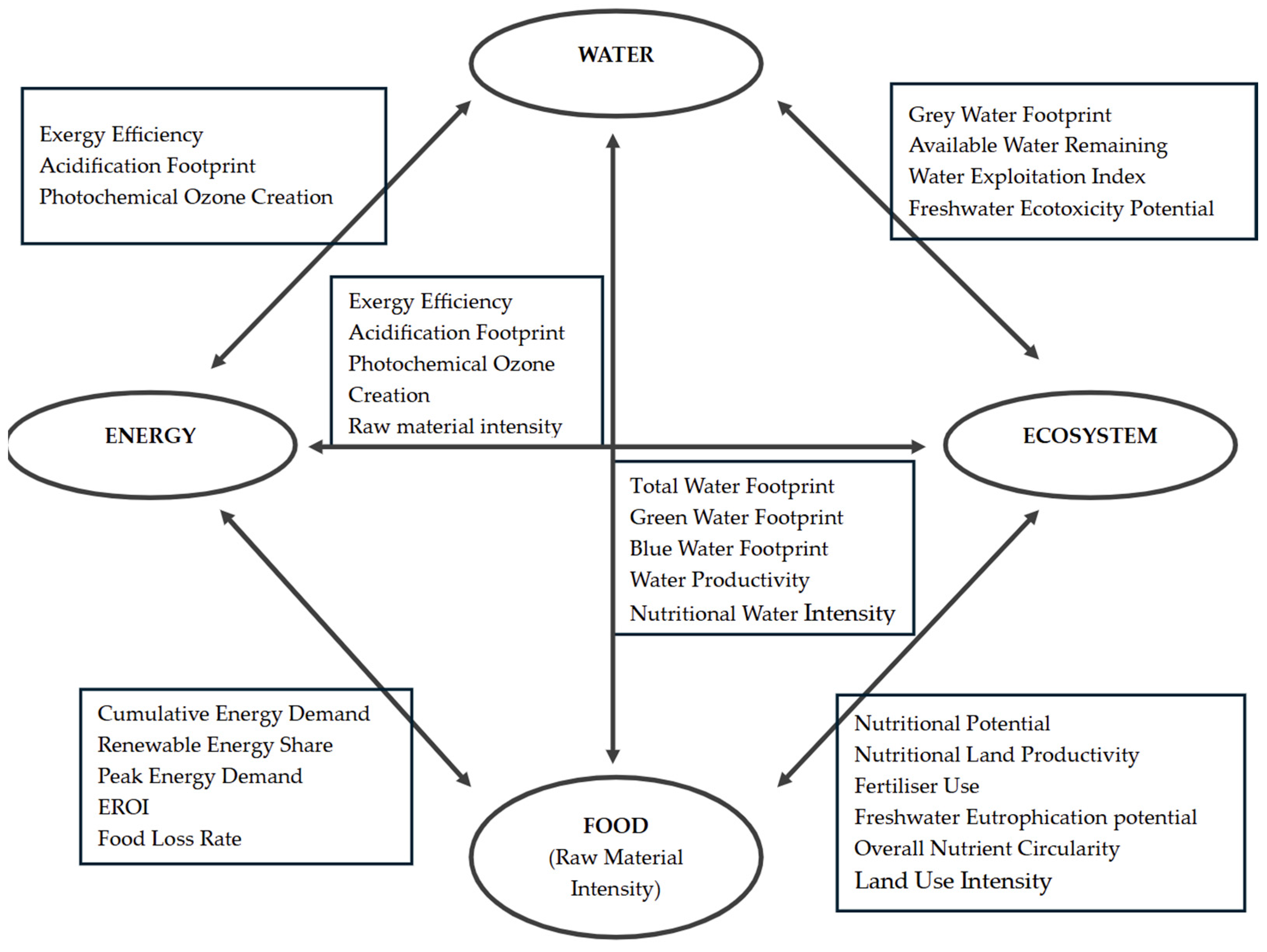

2.1. Selecting Life-Cycle-Based Indicators and Assigning Them to the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Dimension

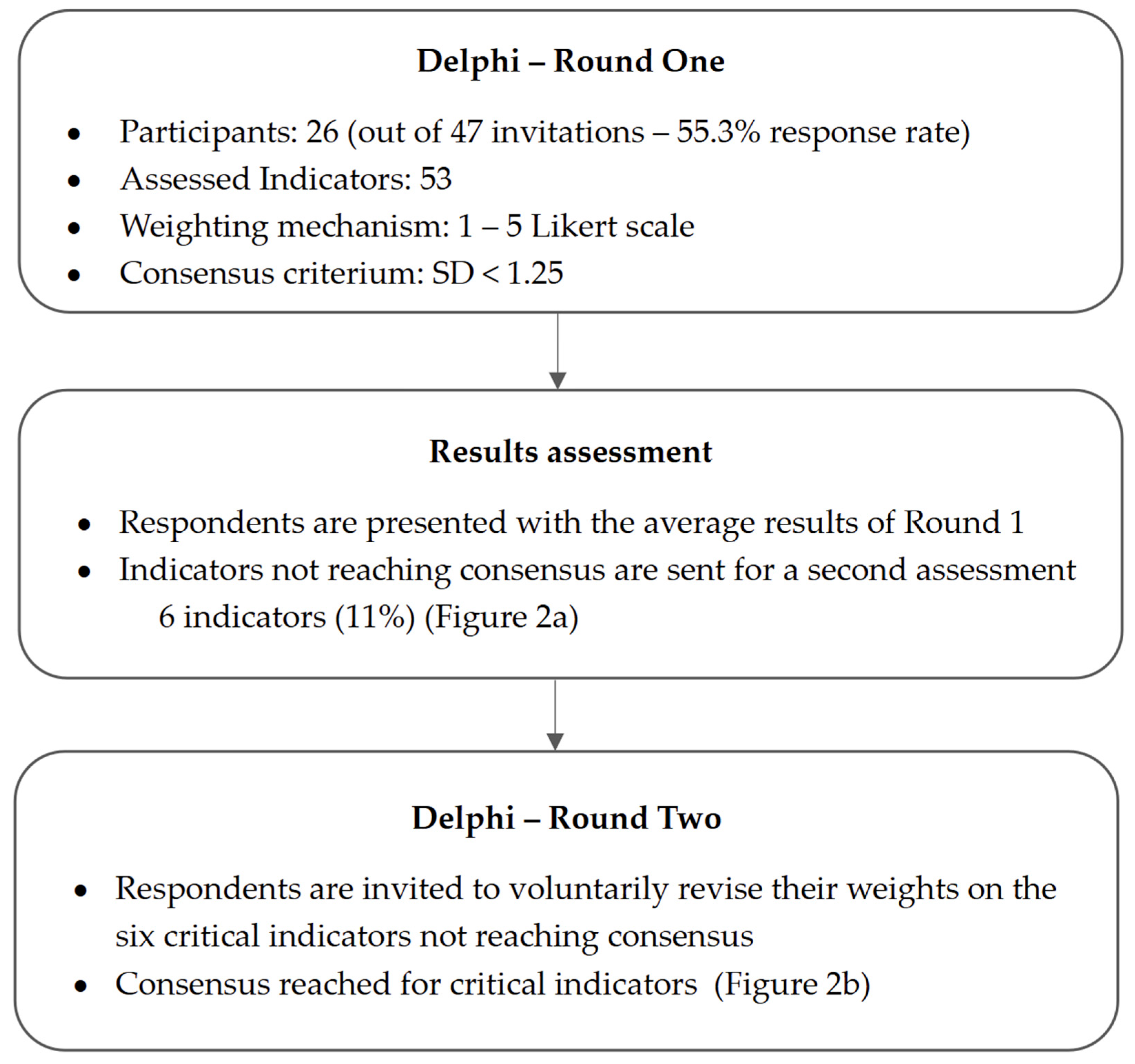

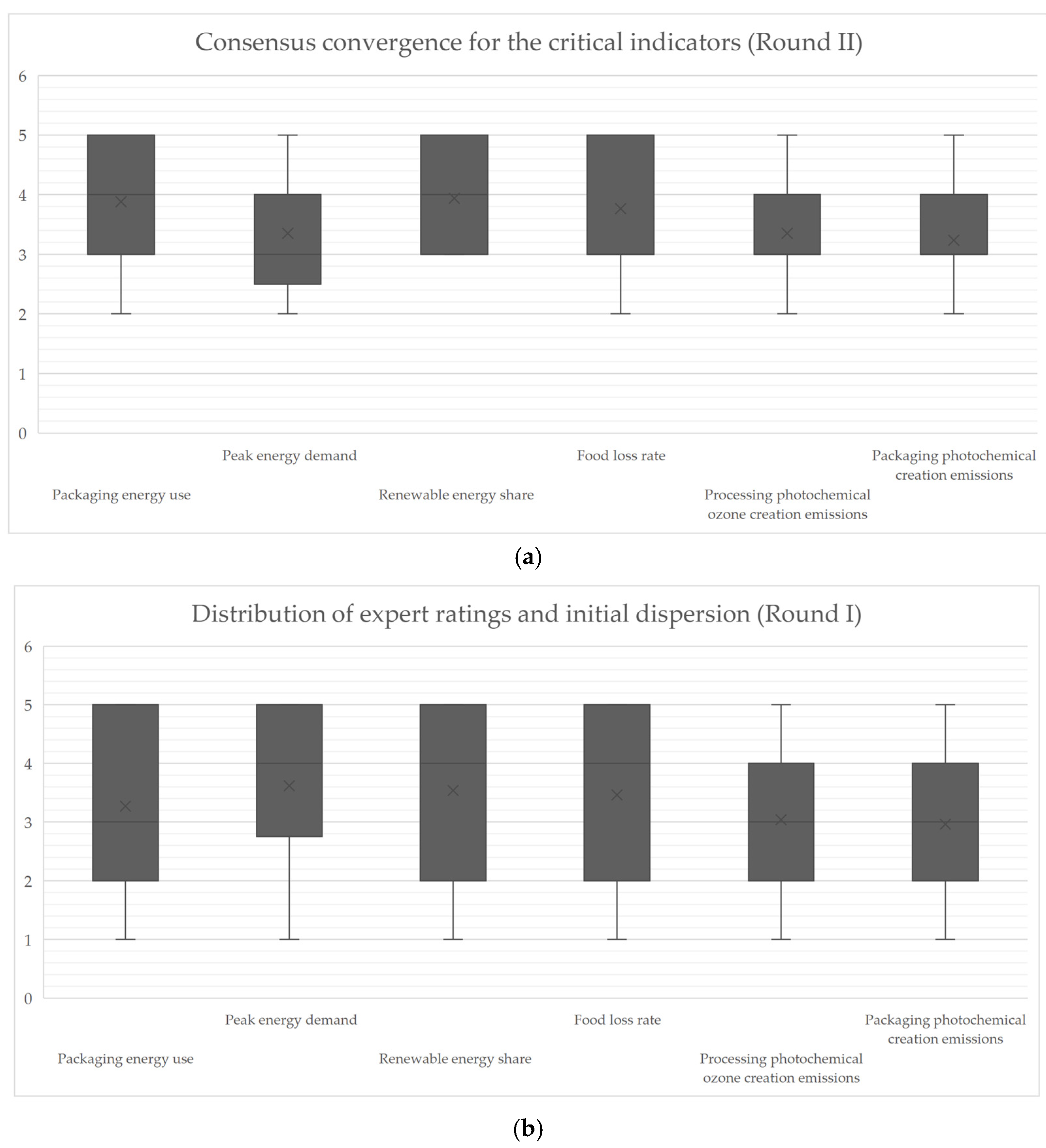

2.2. Direct Weighting of the Indicators: Engaging with a Set of Experts Through a Delphi Process

2.3. Validation of the Indicators Set Based on Data Availability

3. Results

3.1. Final Indicators Batch

- Energy: 4 indicators

- Water: 6 indicators

- Food: 7 indicators

- Ecosystem: 6 indicators

3.1.1. Energy-Related Indicators

Full-Life-Cycle Energy-Related Indicators

- Cumulative energy demand

- Renewable energy share

Non-Life-Cycle Energy-Related Indicators

- Exergy efficiency

- Peak energy demand

3.1.2. Water-Related Indicators

Life-Cycle-Related Indicators

- Water footprint

- Blue, green, and grey water footprints

- Blue water footprint

- Green water footprint

- Grey water footprint

- Available water remaining (AWARE)

Non-Life-Cycle-Related Indicators

- Water productivity

- Water exploitation index

3.1.3. Food Indicators

Life-Cycle-Based Indicators

- Nutritional water intensity

- Nutritional water intensity

- Nutritional energy intensity

Non-Life-Cycle-Based Indicators

- Nutritional potential

- Nutritional land productivity

- Fertiliser use

- Material intensity-related food indicators

3.1.4. Ecosystem-Related Indicators

Life-Cycle-Based Indicators

- Acidification potential and photochemical ozone creation potential

- Freshwater eutrophication potential

- Freshwater ecotoxicity potential

Non-Life-Cycle-Related Indicators

- Overall nutrient circularity

- Land use intensity

3.2. Validation: Checking for Data Availability

- Energy dimension

- Available: 50%

- Not available: 50%

- Partially available: 0%

- Water Dimension

- Available: 26%

- Not available: 57%

- Partially available: 17%

- Food dimension

- Available: 0%

- Not available: 69%

- Partially available: 31%

- Ecosystem dimension

- Available: 61%

- Not available: 39%

- Partially available: 0%

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchical Process |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| PCR | Product Category Rules |

| SWARA | Step-Wise Assessment Ratio Analysis |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| WEFE | Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem |

| WEI | Water Exploitation Index |

References

- Praneetvatakul, S.; Vijitsrikamol, K.; Schreinemachers, P. Ecolabeling to Improve Product Quality and Reduce Environmental Impact: A Choice Experiment with Vegetable Farmers in Thailand. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5, 704233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Haugaard, P.; Olesen, A. Consumer Responses to Ecolabels. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1787–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.; Bastounis, A.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Stewart, C.; Frie, K.; Tudor, K.; Bianchi, F.; Cartwright, E.; Cook, B.; Rayner, M.; et al. The Effects of Environmental Sustainability Labels on Selection, Purchase, and Consumption of Food and Drink Products: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 891–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Cricelli, L.; Mauriello, R.; Strazzullo, S. Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraldo, F.; Testa, F.; Bartolozzi, I. An Application of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as a Green Marketing Tool for Agricultural Products: The Case of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil in Val di Cornia, Italy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrane, S.J.; Acuto, M.; Artioli, F.; Chen, P.Y.; Comber, R.; Cottee, J.; Farr-Wharton, G.; Green, N.; Helfgott, A.; Larcom, S.; et al. Scaling the Nexus: Towards Integrated Frameworks for Analysing Water, Energy and Food. Geogr. J. 2019, 185, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, R.K. The Environmental Impacts of Agriculture: A Review. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 18, 165–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, L.; Cappelli, A.; Cini, E.; Garbati Pegna, F.; Boncinelli, P. Environmental Sustainability of Pasta Production Chains: An Integrated Approach for Comparing Local and Global Chains. Resources 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruini, L.; Ferrari, E.; Meriggi, P.; Marino, M.; Sessa, F. Increasing the Sustainability of Pasta Production through a Life Cycle Assessment Approach. In Proceedings of the 20th Advances in Production Management Systems (APMS), State College, PA, USA, 9–12 September 2013; pp. 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catellani, E.; Manfredini, S.; Amico, C.; Ciccullo, F.; Cigolini, R. Sustainability on the plate: Unveiling the environmental footprint of pasta supply chain through Life Cycle Assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingale, S.; Licciardello, F.; Giunta, G.; Mistretta, M. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment for Improved Management of Agri-Food Companies: The Case of Organic Whole-Grain Durum Wheat Pasta in Sicily. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasilnikov, P.; Taboada, M.A.; Amanullah. Fertilizer Use, Soil Health and Agricultural Sustainability. Agriculture 2022, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrena-Barbero, E.; Santos, S.C.; Cortés, A.; Esteve-Llorens, X.; Moreira, M.T.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Quiñoy, D.; Almeida, C.; Marques, A.; Quinteiro, P.; et al. Methodological Guidelines for the Calculation of a Water-Energy-Food Nexus Index for Seafood Products. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Cranston, G.R.; Sutherland, W.J.; Tranter, H.R.; Bell, S.J.; Benton, T.G.; Blixt, E.; Bowe, C.; Broadley, S.; Brown, A.; et al. Research Priorities for Managing the Impacts and Dependencies of Business upon Food, Energy, Water and the Environment. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Borghi, A.; Moreschi, L.; Gallo, M. Circular Economy Approach to Reduce Water–Energy–Food Nexus. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. Sci. Health 2019, 41, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulvoulis, N. The Potential of Water Reuse as a Management Option for Water Security under the Ecosystem Services Approach. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 3263–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammer, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. The Influence of Eco-Labelling on Consumer Behaviour—Results of a Discrete Choice Analysis for Washing Machines. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkov, N.; Schneider, L.; Lehmann, A.; Finkbeiner, M. Type III Environmental Declaration Programmes and Harmonization of Product Category Rules: Status Quo and Practical Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, C.; Meyer, K.; Rutherford Carr, G.; Hill, J.P.; Hort, J. Taking a Consumer Led Approach to Identify Key Characteristics of an Effective Ecolabelling Scheme. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Borghi, A.; Strazza, C.; Magrassi, F.; Taramasso, A.C.; Gallo, M. Life Cycle Assessment for Eco-Design of Product–Package Systems in the Food Industry—The Case of Legumes. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 13, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zanten, J.A.; van Tulder, R. Towards Nexus-Based Governance: Defining Interactions between Economic Activities and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, H. Understanding the Nexus. Background Paper for the Bonn2011 Conference: The Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011; 51p. [Google Scholar]

- Estoque, R.C. Complexity and Diversity of Nexuses: A Review of the Nexus Approach in the Sustainability Context. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigolin, E.; Rossetto, R.; Corsini, F.; Frey, M. The Integration of the Water-Energy-Food Nexus Framework into Corporate Sustainability Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 7490–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F.; Bullock, G. Nexus Thinking in Business: Analysing Corporate Responses to Interconnected Global Sustainability Challenges. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, P.; Yang, L.; Fan, Y.V.; Klemeš, J.J.; Wang, Y. Extended Water-Energy Nexus Contribution to Environmentally-Related Sustainable Development Goals. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreschi, L.; Gagliano, E.; Gallo, M.; Del Borghi, A. A Framework for the Environmental Assessment of Water-Energy-Food-Climate Nexus of Crops: Development of a Comprehensive Decision Support Indicator. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrena-Barbero, E.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Vásquez-Ibarra, L.; Fernández, M.; Feijoo, G.; González-García, S.; Moreira, M.T. Water-Energy-Food Nexus Index Proposal as a Sustainability Criterion on Dairy Farms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Borrion, A.; Fonseca-Zang, W.A.; Zang, J.W.; Leandro, W.M.; Campos, L.C. Life Cycle Assessment of a Biogas System for Cassava Processing in Brazil to Close the Loop in the Water-Waste-Energy-Food Nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 126861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites-Lazaro, L.L.; Giatti, L.L.; Puppim de Oliveira, J.A. Water-Energy-Food Nexus Approach at the Core of Businesses—How Businesses in the Bioenergy Sector in Brazil are Responding to Integrated Challenges? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Cudennec, C.; Gain, A.K.; Hoff, H.; Lawford, R.; Qi, L.; Zheng, C. Challenges in Operationalizing the Water–Energy–Food Nexus. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14025:2006; Environmental Labels and Declarations—Type III Environmental Declarations—Principles and Procedures. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- EPD International. Product Category Rules (PCR) 2010:01 Uncooked Pasta, Not Stuffed or Otherwise Prepared, UN CPC 2371 (Version 4.0.5); EPD International AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025; Available online: https://www.environdec.com/pcr-library/pcr2010-01 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of the Delphi Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEXUS Energy-Water-Food-Land Network. Available online: https://nexusnet-cost.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- EPD International. Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) Library Search: Pasta. Available online: https://www.environdec.com/library?q=pasta (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Frischknecht, R.; Jungbluth, N.; Althaus, H.-J.; Doka, G.; Dones, R.; Heck, T.; Hellweg, S.; Hischier, R.; Nemecek, T.; Rebitzer, G.; et al. Overview and Methodology: Data v2.0 (2007); Ecoinvent Report No. 1; Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories: Dübendorf, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14046:2014; Environmental Management—Water Footprint—Principles, Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Crops and Derived Crop Products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghbashlo, M. Exergy-Based Sustainability Analysis of Food Production Systems. Planet. Sustain. 2023, 1, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgenannt, P.; Huber, G.; Rheinberger, K.; Kolhe, M.; Kepplinger, P. Comparison of Demand Response Strategies Using Active and Passive Thermal Energy Storage in a Food Processing Plant. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulay, A.M.; Bare, J.; Benini, L.; Berger, M.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Manzardo, A.; Margni, M.; Motoshita, M.; Núñez, M.; Pastor, A.V.; et al. The WULCA Consensus Characterization Model for Water Scarcity Footprints: Assessing Impacts of Water Consumption Based on Available Water Remaining (AWARE). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D. Improving Agricultural Water Productivity: Between Optimism and Caution. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadei, S.; Peppoloni, F.; Pierleoni, A. A New Approach to Calculate the Water Exploitation Index (WEI+). Water 2023, 12, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Hung, P.Q. Virtual Water Trade: A Quantification of Virtual Water Flows Between Nations in Relation to International Crop Trade; Value of Water Research Report Series No. 11; IHE Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bajan, B. Edible Energy Production and Energy Return on Investment—Long-Term Analysis of Global Changes. Energies 2021, 14, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, M.; Goedkoop, M.; Guinee, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; De Schryver, A. Recommendation for Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) in the European Context—Based on Existing Environmental Impact Assessment Models and Factors; JRC Scientific and Technical Reports 2011, EUR 24571 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Keast, D.R.; Drewnowski, A. Development and Validation of the Nutrient-Rich Foods Index: A Tool to Measure Nutritional Quality of Foods. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnielka, A.E.; Menzel, C. The Impact of the Consumer’s Decision on the Life Cycle Assessment of Organic Pasta. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixen, P.E.; Bruulsema, T.W.; Mikkelsen, R.; Sulewski, G.; Williams, C. Nutrient/Fertilizer Use Efficiency: Measurement, Current Situation and Trends. In Managing Water and Fertilizer for Sustainable Agricultural Intensification; Drechsel, P., Heffer, P., Magen, H., Mikkelsen, R., Wichelns, D., Eds.; International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA): Paris, France, 2015; Volume 270, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Bai, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yin, Y. Variations of soil microbial communities accompanied by different vegetation restoration in an open-cut iron mining area. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibelli, F.; Mistretta, M.; Raggi, A.; Raugei, M.; Reck, B.; Rugani, B.; Vázquez-Rowe, I. Environmental Profile of Organic Pasta. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Braglia, M.; Carmignani, G.; Zammori, F.A. Life cycle assessment of pasta production in Italy. J. Food Qual. 2007, 30, 932–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaya, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The water needed for Italians to eat pasta and pizza. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijdam, D.; Rood, T.; Westhoek, H. The Price of Protein: Review of Land Use and Carbon Footprints from Life Cycle Assessments of Animal Food Products and Their Substitutes. Food Policy 2012, 37, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. Ellen MacArthur Foundation Report 2013. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Wackernagel, M.; Rees, W. Perceptual and structural barriers to investing in natural capital: Economics from an ecological footprint perspective. Ecol. Econ. 1997, 20, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubako, S.T. Blue, Green, and Grey Water Quantification Approaches: A Bibliometric and Literature Review. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2018, 165, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele-Alemu, T. Rethinking Progress: Harmonizing the Discourse on Genetically Modified Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1547928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngongolo, K. Necessities, Environmental Impact, and Ecological Sustainability of Genetically Modified (GM) Crops. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R. Ecotoxicological Effect Factors for Calculating USEtox Ecotoxicity Characterization Factors. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Schenk, G.; Robinson, N.; John, S.; Dayananda, B.; Krishnan, V.; Adam, C.; Hermann, L.; Schmidt, S. The Circular Phosphorus Economy: Agronomic Performance of Recycled Fertilizers and Target Crops. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2025, 188, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, P.; De Paula, J.; Keeler, J. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry, 11th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, M.; Al-Ansari, T.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Quantifying the Energy, Water and Food Nexus: A Review of the Latest Developments Based on Life-Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell-Perez, M.E.; Gomes, C.; Tahtouh, J.; Moreira, R.; McLamore, E.S.; Knowles, H.S., III. Food Processing and Waste Within the Nexus Framework. Curr. Sustain./Renew. Energy Rep. 2017, 4, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, L.; Passarini, F. Editorial: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Environmental and Energy Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, B.A.; Nurdiawati, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Freshwater Use in LCA: Established Practices and Current Methods. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2025, 11, 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzai, H.; Lahmandi-Ayed, R. Ecolabel: Is More Information Better? Environ. Model. Assess. 2022, 27, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Objective | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| a. Selecting life-cycle-based indicators and assigning them to the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem dimension | Literature search for relevant indicators | Scopus search: TITLE-ABS-KEY: “((WEFE) OR (Wate Energy Food) Nexus) AND (LCA OR Ecolabel* OR certification OR (green label))” and “(Pasta) AND (LCA OR Ecolabel* OR certification OR (green label))”. |

| Indicator selection | (i) Simple indicators excluding ratios or complex models, and (ii) indicators clearly falling into a specific WEFE dimension | |

| Allocation to the WEFE dimensions | Allocation of the indicators to the dimension that best captured the described impact | |

| Categorisation of the indicators between LCA-based and non-LCA-based indicators, within each dimension | (i) LCA-based indicators following ISO 14040-44 [33,34] standards, and (ii) non-LCA-based indicators not following ISO 14040-44 standards. | |

| b. Direct Weighting of the indicators: engaging with a set of experts through a Delphi process. | First round of Delphi engagement with the experts of the “Nexus Net” Cost Action (CA 20138) | Direct weighting on a 1–5 Likert scale according to the indicator’s capability to: (i) provide clear and effective information to producers about their WEF performance; and (ii) serve as a direct instrument to inform consumers and guide their choices. |

| Second round of Delphi engagement with the experts of the “Nexus Net” Cost Action (CA 20138) | Reassessments of the indicators collecting a Standard Deviation above 1.25 on the received weighting. | |

| c. Validation of the indicators set based on data availability | Collection of valid EPDs in the pasta sector | Six EPDs for the LCA of some pasta brands were collected from https://www.environdec.com/services/what-is-pcr (accessed on 16 October 2025). |

| Evaluation of indicator fulfilment based on data availability in standard LCA inventories of the selected EPDs | Each indicator was classified into three categories: (i) identical or different but fully computable with available inventory data; (ii) partially computable with available data; and (iii) not computable with available data. |

| ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional unit | 1 kg | 1 kg | 1 kg | 1 kg | 1 kg | 1 kg |

| Geographical area | Thiva, Greece | Marcianise, Italy | Italy and Greece | Imperia, Italy | Fossano, Italy | Castello di Godego, Italy |

| Type of LCA certification | EPD ISO 14025 | EPD ISO 14025 | EPD ISO 14025 | EPD ISO 14025 | EPD ISO 14025 | EPD ISO 14025 |

| System boundaries | Cradle to grave | Cradle to grave | Cradle to grave | Cradle to grave | Cradle to grave | Cradle to grave |

| Used PCR | PCR 2010:01—CPC 2371 | PCR 2010:01 v. 4.0.4 | PCR 2010:01 v. 4.0.4 | PCR 2010:01 v. 4.01 | PCR 2010:01 v. 4.01 | PCR 2010:01 v. 3.11 |

| Validity period | 2014–2023 | 2024–2030 | 2025–2030 | 2022–2026 | 2022–2026 | 2020–2025 |

| Number of revisions | 7 | 7 | 0 (1st edition) | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| ENERGY | WATER | ||||

| Name | UM | Weight | Name | UM | Weight |

| LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | ||||

| Cumulative energy demand [40] | MJ/kg | 4.1 | Water footprint (WF) [41] | L or m3/kg | 4.5 |

| Renewable energy share [8] | % (MJ renewable/MJ total) | 3.5 | Green water footprint [42] | m3GNWF/m3WF% | 4.1 |

| NON-LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | Blue water footprint [42] | m3BWF/m3WF% | 4.1 | ||

| Exergy efficiency [43] | % (Exergy output/Exergy input) | 3.3 | Grey water footprint [42] | m3GYWF/m3WF% | 4.1 |

| Peak energy demand [44] | ∑max_i(Ptot,i) | 3.9 | NON-LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | ||

| AWARE (Available water remaining) [45] | AMD_world/AMD_region | 3.9 | |||

| Water productivity [46] | kg crop yield/L or m3 | 4.2 | |||

| Water exploitation index (WEI) [47] | (m3/available m3)% | 3.8 | |||

| FOOD | ECOSYSTEM | ||||

| Name | UM | Weight | Name | UM | Weight |

| LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | ||||

| Nutritional water intensity, adapted from [41,48] | m3/100 kcal or m3/g protein | 3.9 | Acidification footprint [11] | kg SO2 eq/kg | 3.5 |

| Energy return on investment (EROI) [49] | MJ output/MJ input (per kg pasta) | 3.7 | Photochemical ozone creation [11] | kg C2H4-eq/kg | 3.1 |

| NON-LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | Freshwater eutrophication potential (FEP) [50] | kg P-e/kg | 3.5 | ||

| Nutritional potential (nutrient-rich food index, NRF 9.3) [51] | Composite indicator (g or mg/100 g); % by weight for processed products | 3.6 | Freshwater ecotoxicity potential (FET) [50,52] | kg 1,4-DCB-eq/kg | 3.8 |

| Nutritional land productivity [50] | kcal/m2 | 3.6 | NON-LIFE CYCLE INDICATORS | ||

| Fertiliser use [53] | N + P + K kg/kg | 3.7 | Overall nutrient circularity [54] | [(Recycled N/Total N) + (Recycled P/Total P) + (Recycled K/Total K)]/3 × 100 | 3.9 |

| Raw material intensity [55] | kg harvested grain/kg pasta | 3.5 | Land use [56] | m2 year/kg | 4.0 |

| Food loss rate | % of edible harvested kcal lost | 3.7 | |||

| n. | Indicator Name | Organisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 2 | Renewable Energy Share | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 3 | Exergy Efficiency | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | Peak Energy Demand | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| n. | Indicator Name | Organisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Water Footprint | PA | PA | PA | A | A | A |

| 2a | Green Water Footprint | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2b | Blue Water Footprint | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2c | Grey Water Footprint | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | AWARE (Available Water Remaining) | A | A | A | A | A | PA |

| 5 | Water Productivity | NA | NA | NA | A | A | A |

| 6 | Water Exploitation Index+ (WEI+) | NA | NA | NA | PA | PA | PA |

| n. | Indicator Name | Organisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Nutritional Water Intensity | NA | NA | NA | PA | PA | PA |

| 2 | Energy Return on Investment (EROI) | PA | PA | PA | PA | PA | PA |

| 3 | Nutritional Potential (Nutrient-rich food index, NRF 12.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | Nutritional Land productivity | NA | NA | NA | PA | PA | NA |

| 5 | Fertiliser Use | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | Raw Material Intensity | NA | NA | NA | PA | PA | NA |

| 7 | Food Loss Rate (Edible food loss along the value chain) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| n. | Indicator Name | Organisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Acidification Footprint | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 2 | Photochemical Ozone Creation | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 3 | Freshwater Eutrophication Potential (FEP) | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 4 | Freshwater Ecotoxicity Potential (FET) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | Overall Nutrient Circularity | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | Land Use | NA | A | A | A | A | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bigolin, E.; Rajić, M.; Rađenović, T.; Caucci, S.; Adamos, G.; Frey, M. Operationalising the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in Life Cycle Assessment Ecolabelling: Exploring Indicator Selection Through Delphi Engagement. Resources 2026, 15, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020023

Bigolin E, Rajić M, Rađenović T, Caucci S, Adamos G, Frey M. Operationalising the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in Life Cycle Assessment Ecolabelling: Exploring Indicator Selection Through Delphi Engagement. Resources. 2026; 15(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleBigolin, Edoardo, Milena Rajić, Tamara Rađenović, Serena Caucci, Giannis Adamos, and Marco Frey. 2026. "Operationalising the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in Life Cycle Assessment Ecolabelling: Exploring Indicator Selection Through Delphi Engagement" Resources 15, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020023

APA StyleBigolin, E., Rajić, M., Rađenović, T., Caucci, S., Adamos, G., & Frey, M. (2026). Operationalising the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in Life Cycle Assessment Ecolabelling: Exploring Indicator Selection Through Delphi Engagement. Resources, 15(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020023