Enhancing Flood Mitigation and Water Storage Through Ensemble-Based Inflow Prediction and Reservoir Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

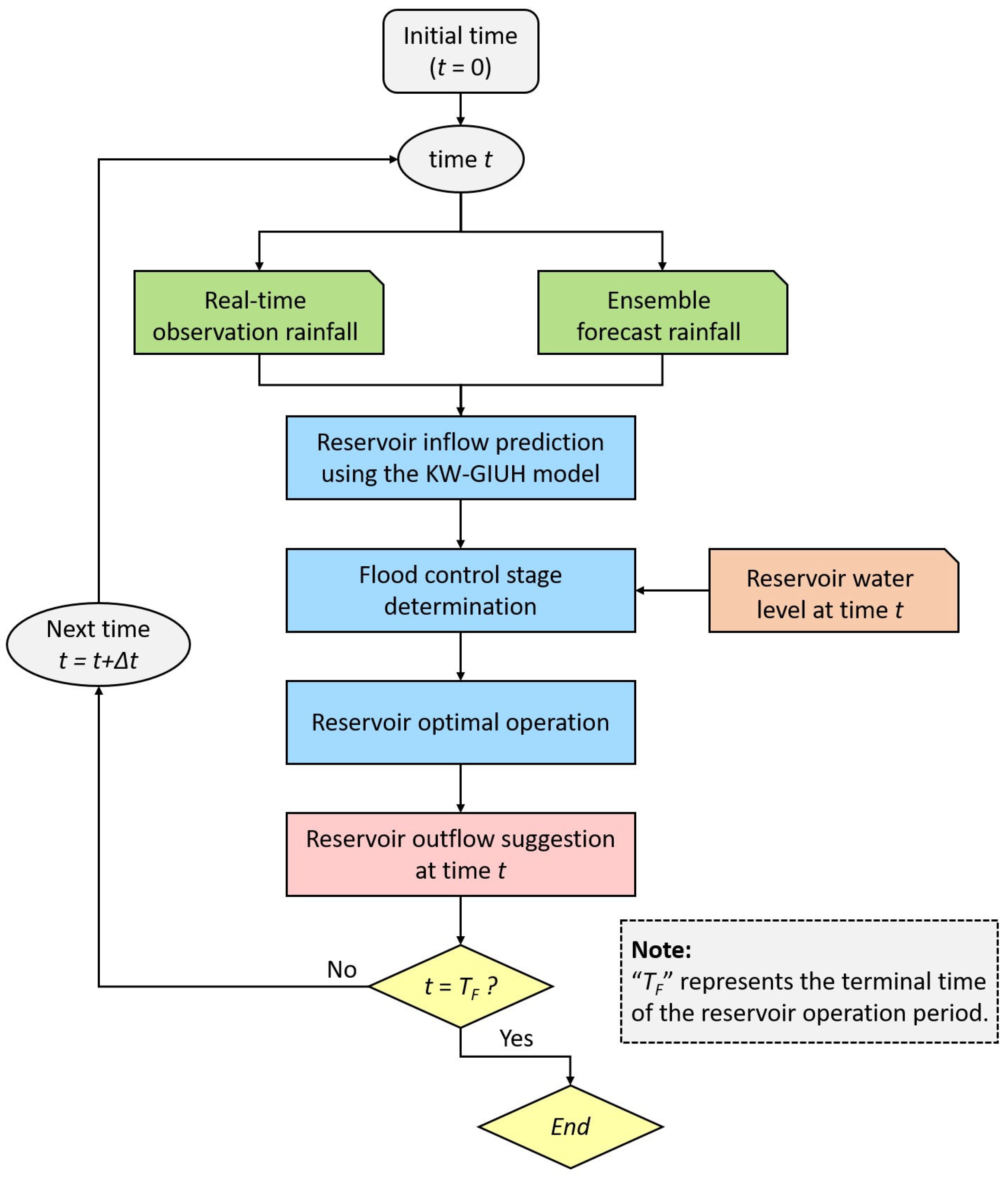

2. Reservoir Operation Algorithm for Typhoon Storms

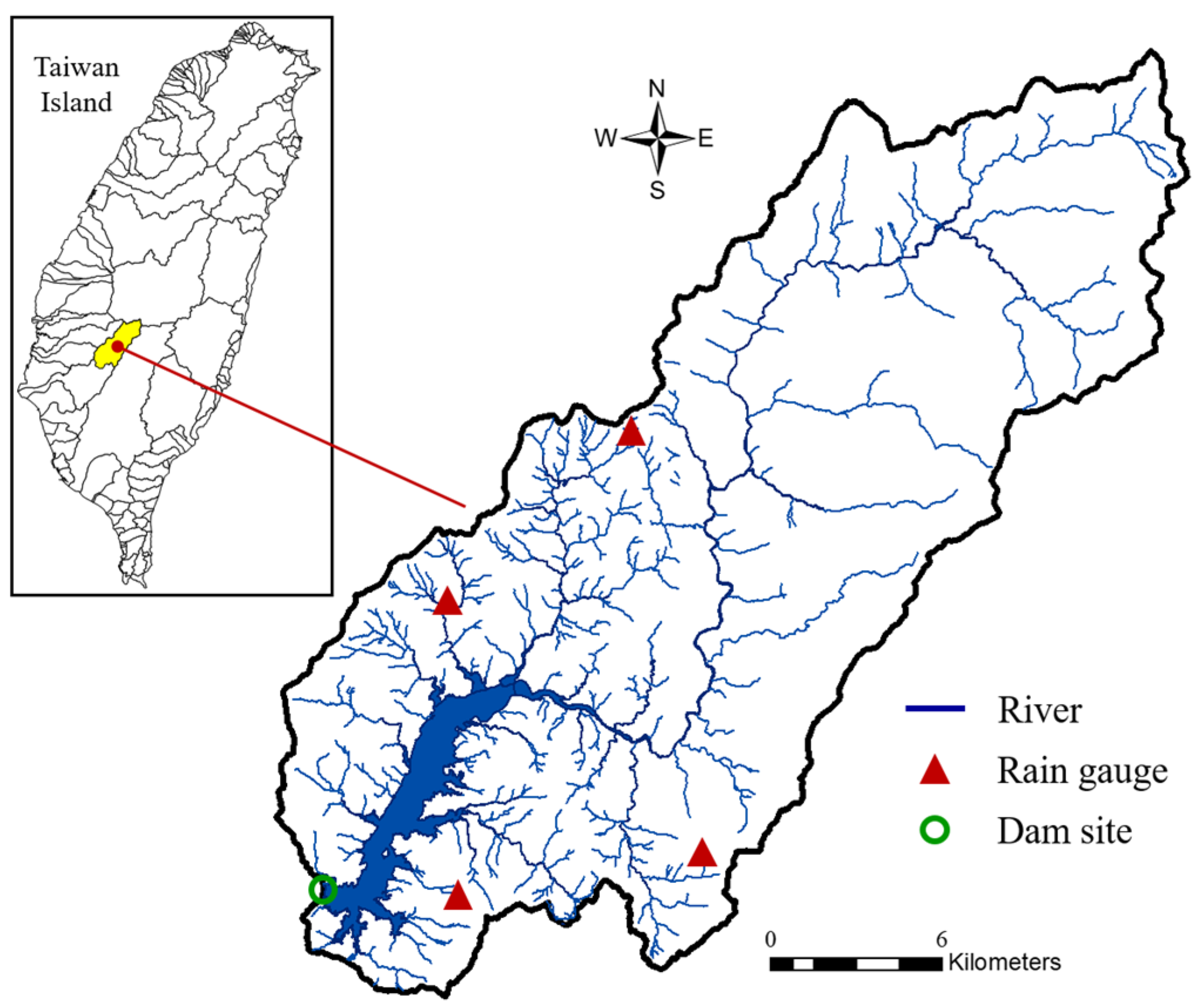

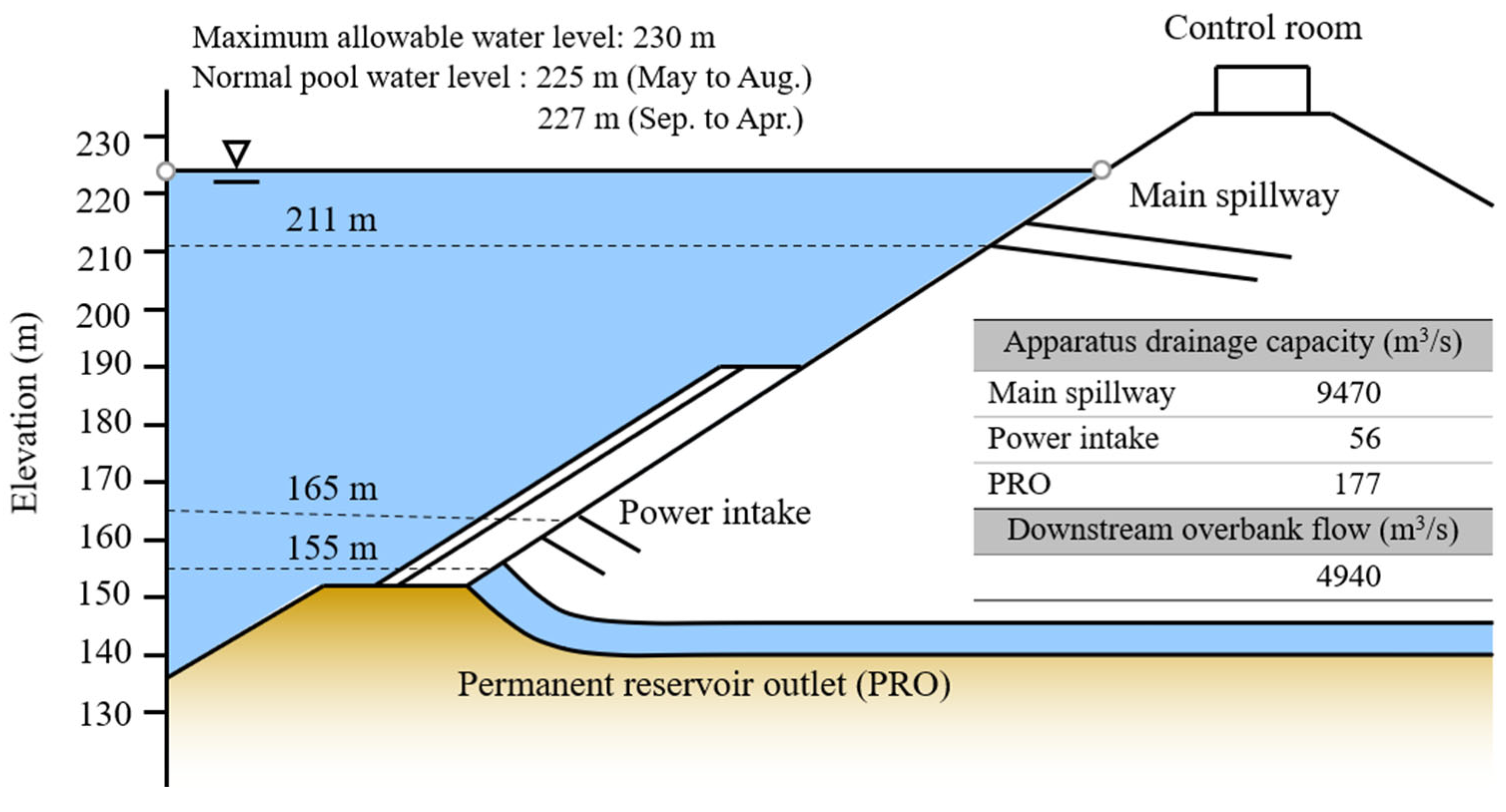

2.1. Description of the Study Watershed

2.2. Estimation of Reservoir Upstream Inflow

2.3. Optimization of Reservoir Operation

- (1)

- Before the onset of flood (Stage I):

- (2)

- Flood occurrence period (Stage II):

- (3)

- Flood recession period (Stage III):

2.4. Summary of Reservoir Operation

3. Ensemble Rainfall Forecast

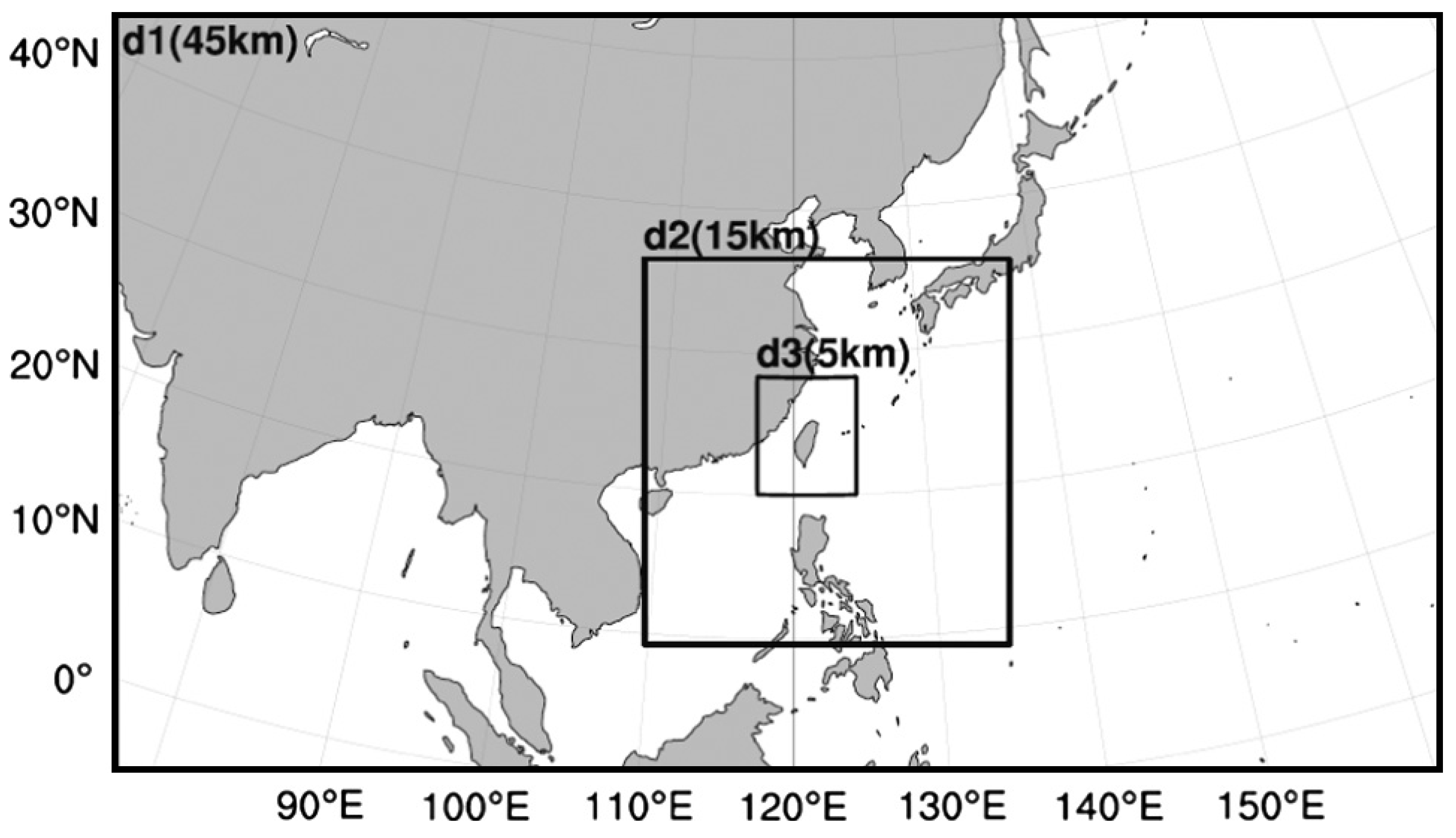

3.1. Mesoscale Meteorological Models

- (1)

- Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model

- (2)

- Fifth-generation Mesoscale Model (MM5)

3.2. Ensemble Configuration

- (a)

- Cold-start or partial-cycle initializations, which generate different atmospheric first-guess states;

- (b)

- Variations in data assimilation, with some members incorporating synthetic (bogus) typhoon observations while others rely solely on observational datasets; and

- (c)

- Different nesting strategies, including one-way and two-way interactive coupling between domains, modify feedback strength across spatial scales.

| Ensemble Member | Model | ICs | LBCs | Cumulus Scheme | Microphysics Scheme | Boundary Layer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR (CV5 + OL) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | GD | Goddard | YSU | |

| 02 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR | Bogus | NCEP GFS | G3 | Goddard | YSU | |

| 03 | WRF | Partial cycle | (CV5 + OL) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | Goddard | YSU | ||

| 04 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR (CV5) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | BMJ | Goddard | YSU | |

| 05 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR | Bogus | Two-way interaction | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU |

| 06 | WRF | Cold Start | (CV5 + OL) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU | |

| 07 | WRF | Cold Start | 3DVAR | Bogus | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU | |

| 08 | WRF | Cold Start | (CV5 + OL) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | GD | Goddard | YSU | |

| 09 | WRF | Cold Start | 3DVAR (CV5 + OL) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | G3 | Goddard | YSU | |

| 10 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR (CV3 | NCEP GFS | BMJ | Goddard | YSU | ||

| 11 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR (CV5 + OL) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU | |

| 12 | WRF | Partial cycle | 3DVAR (CV3) | CWB GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU | ||

| 13 | WRF | Cold Start | 3DVAR | Bogus | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU | |

| 14 | WRF | Cold Start | (CV3) | Bogus | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU | |

| 15 | WRF | Cold Start | 3DVAR | Bogus | Two-way interaction | NCEP GFS | KF | Goddard | YSU |

| 16 | WRF | Cold Start | NODA | NCEP GFS | KF | WSM5 | YSU | ||

| 17 | MM5 | Cold Start | NODA | NCEP GFS | Grell | Goddard | MRF | ||

| 18 | MM5 | Cold Start | 4DVAR | Bogus | NCEP GFS | Grell | Goddard | MRF |

4. Model Testing

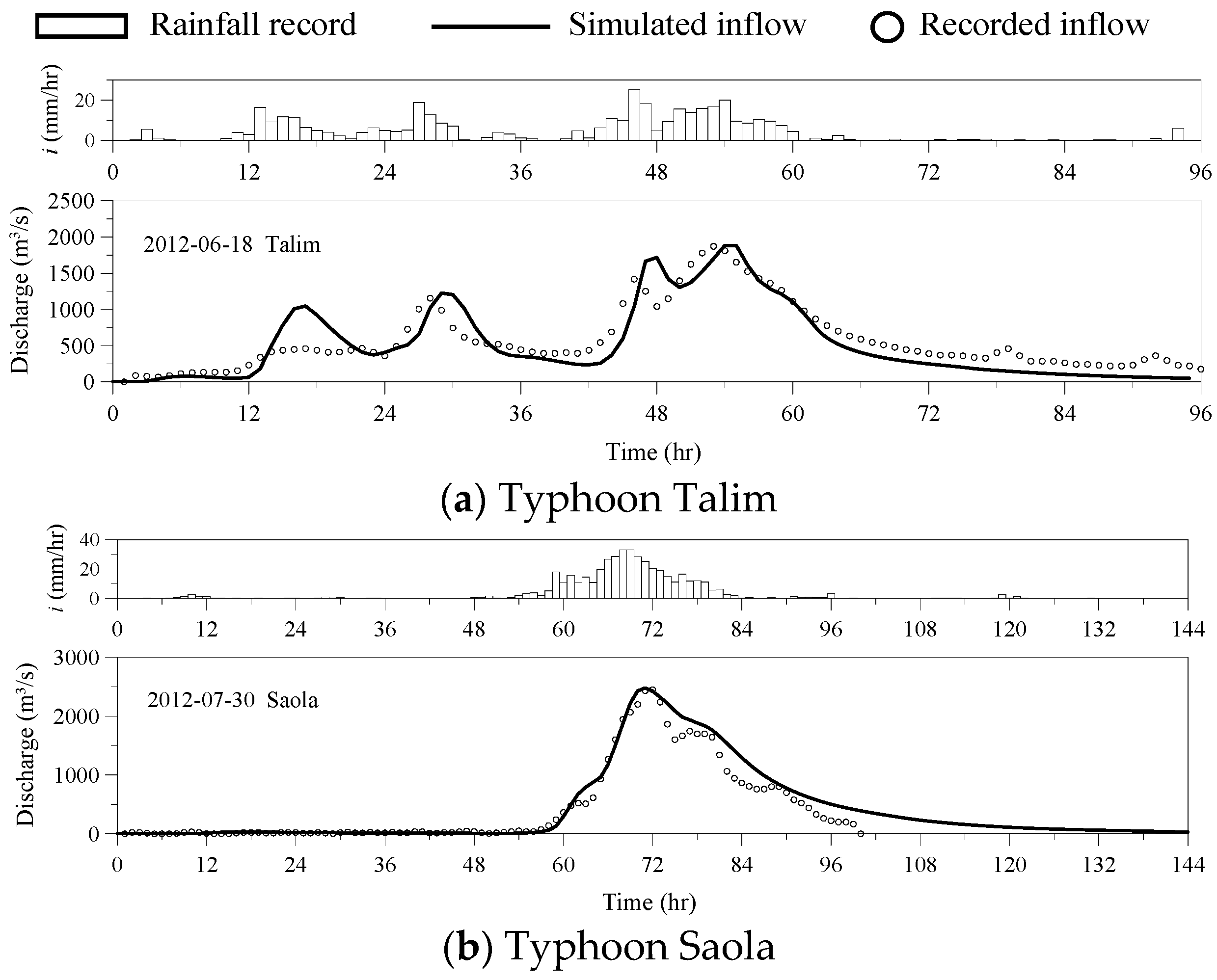

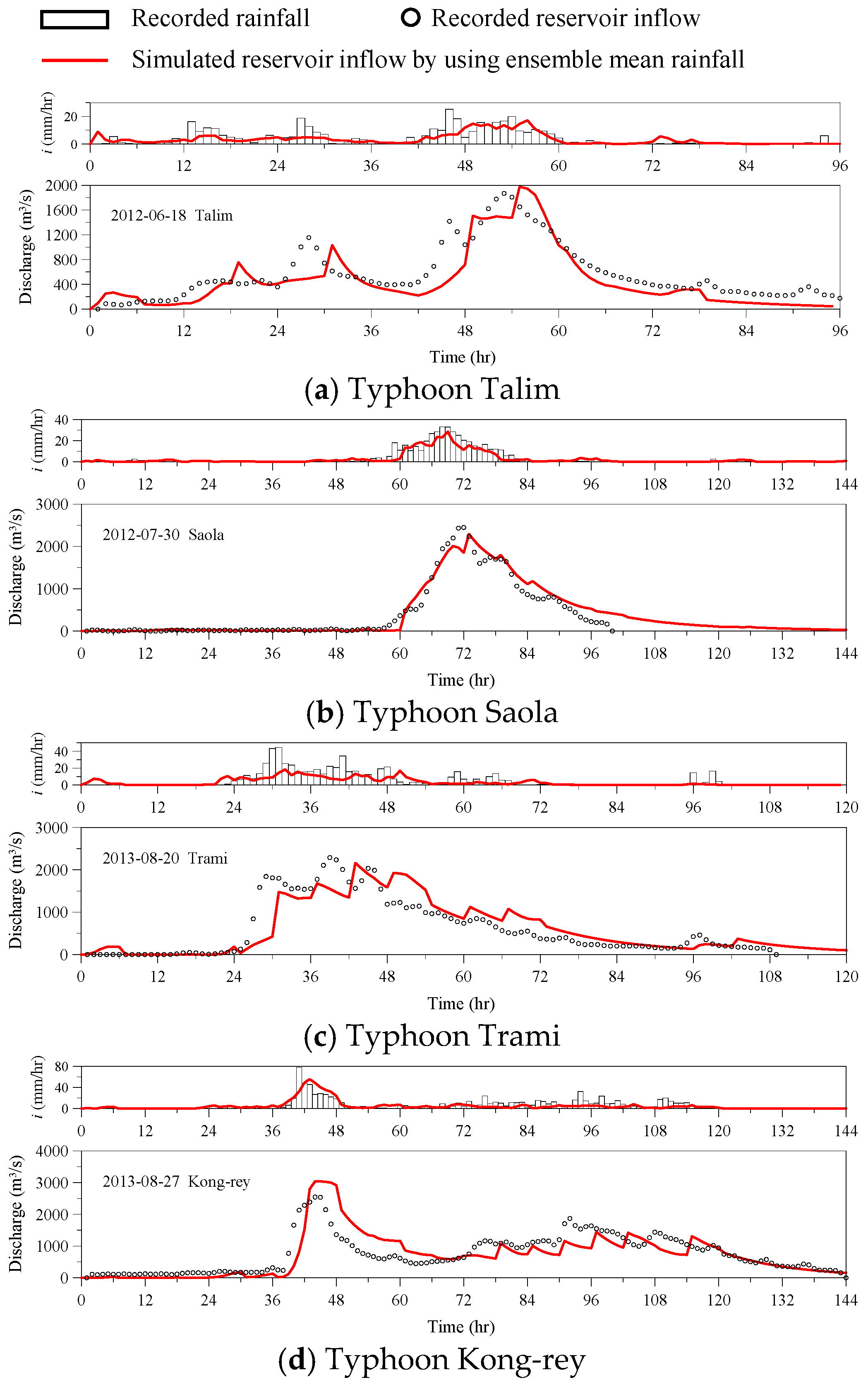

4.1. Test of the Rainfall–Runoff Model Using Recorded Rainfall

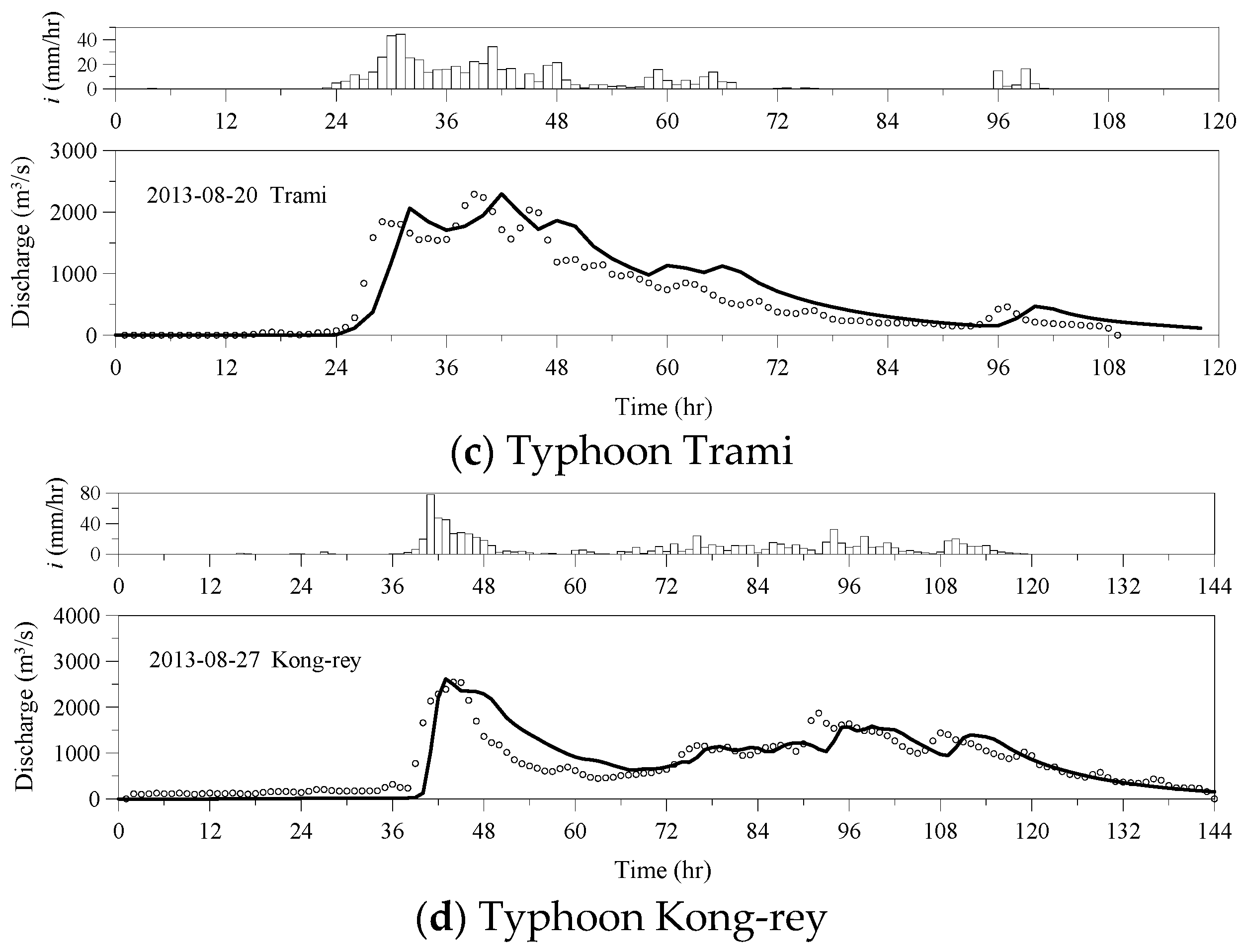

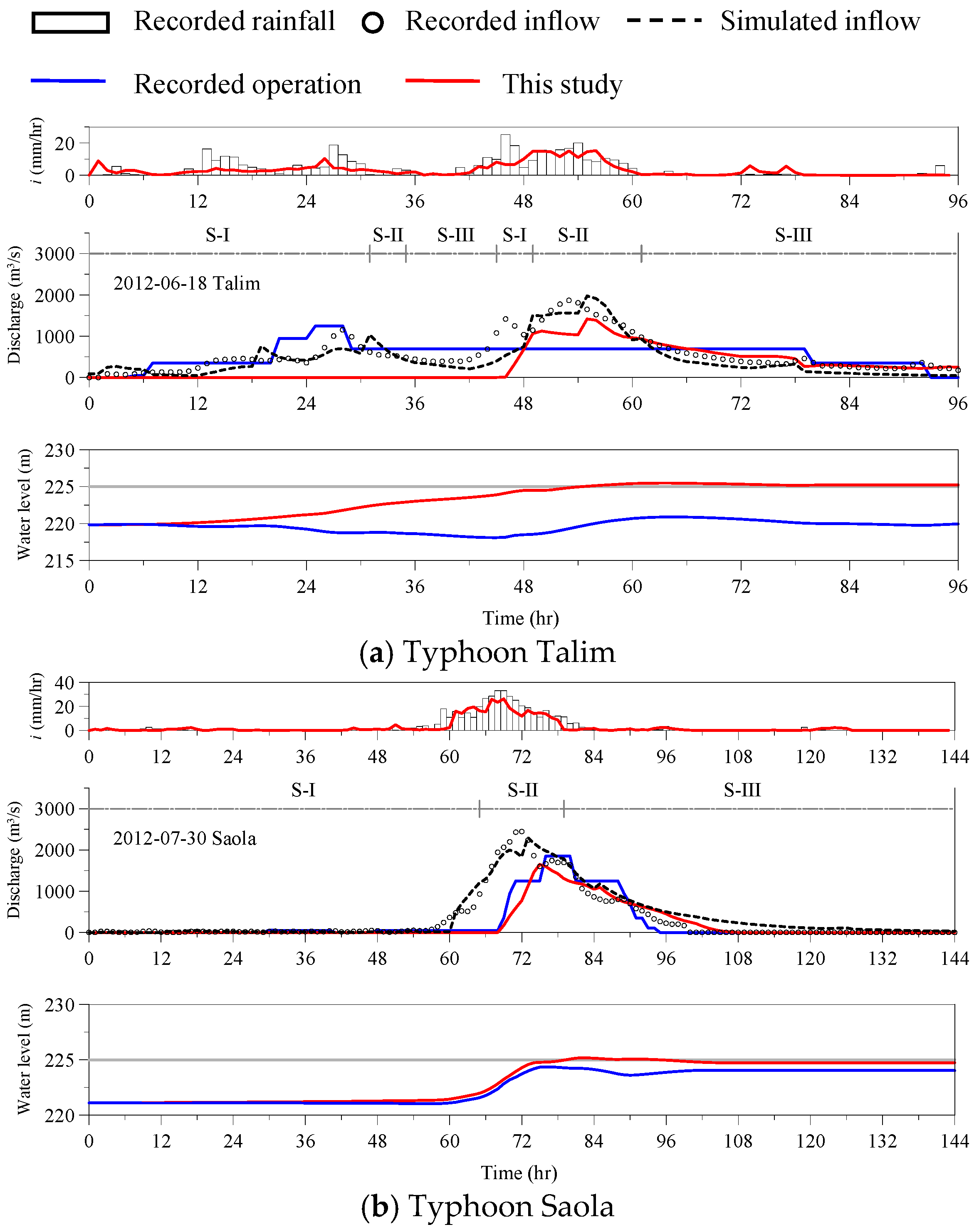

4.2. Test of Reservoir Operation Algorithm Using Recorded Inflow

5. Results and Discussions

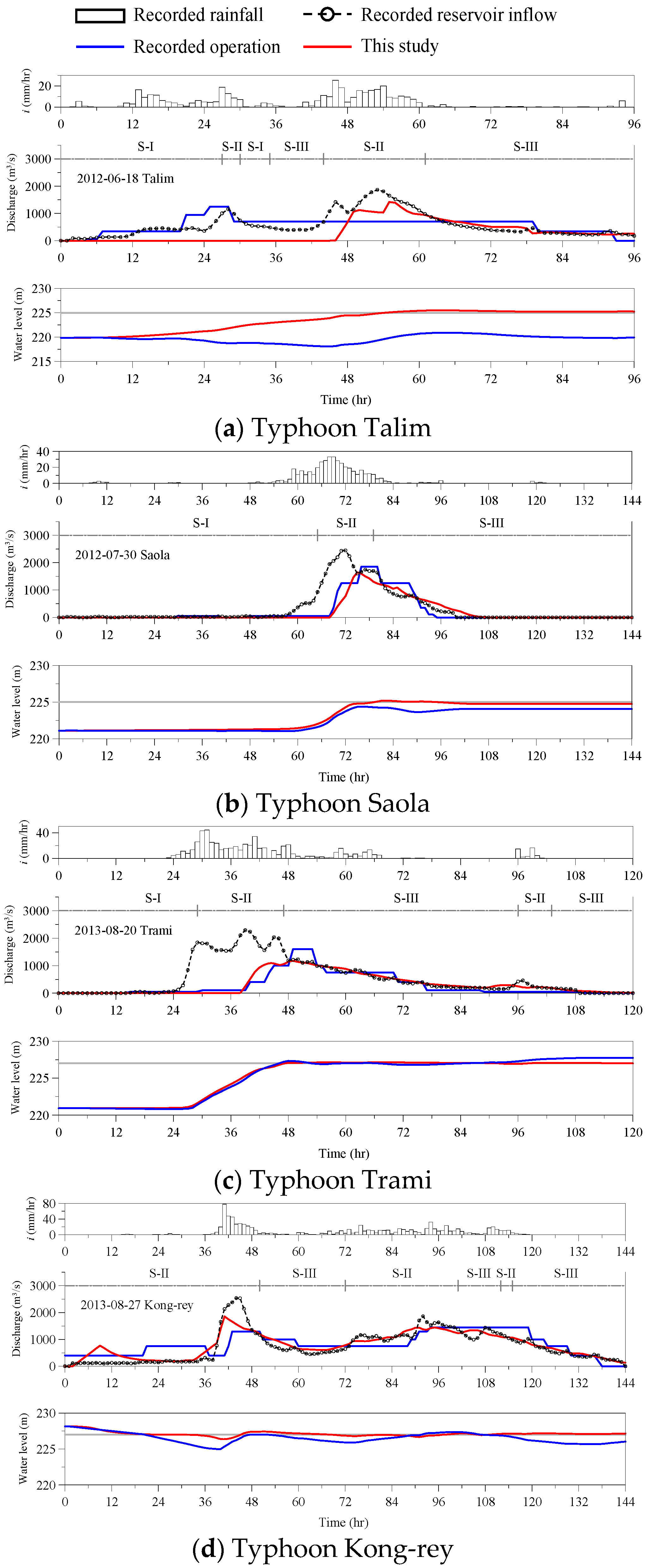

5.1. Application of Forecast Rainfall for Reservoir Inflow Prediction

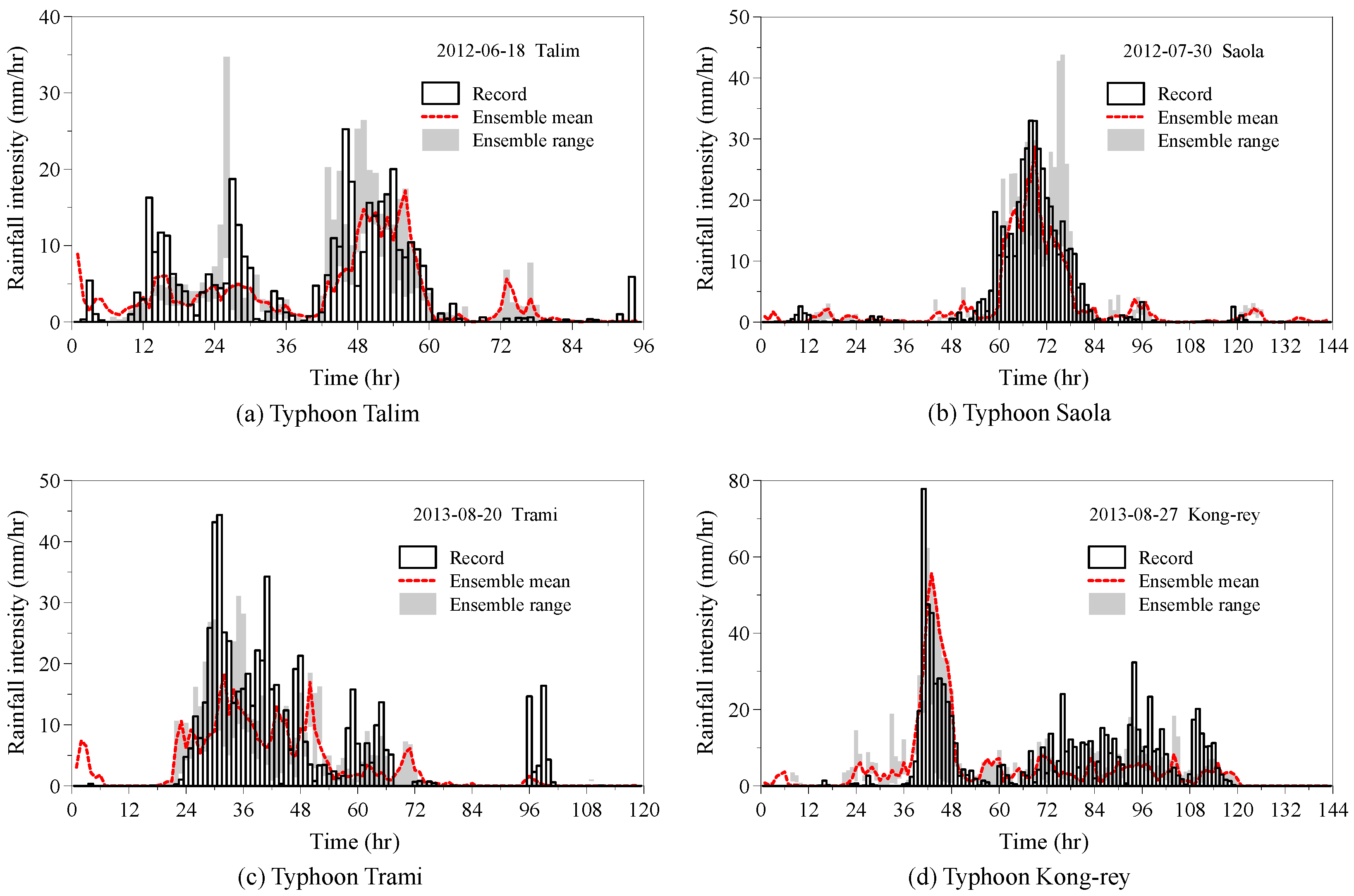

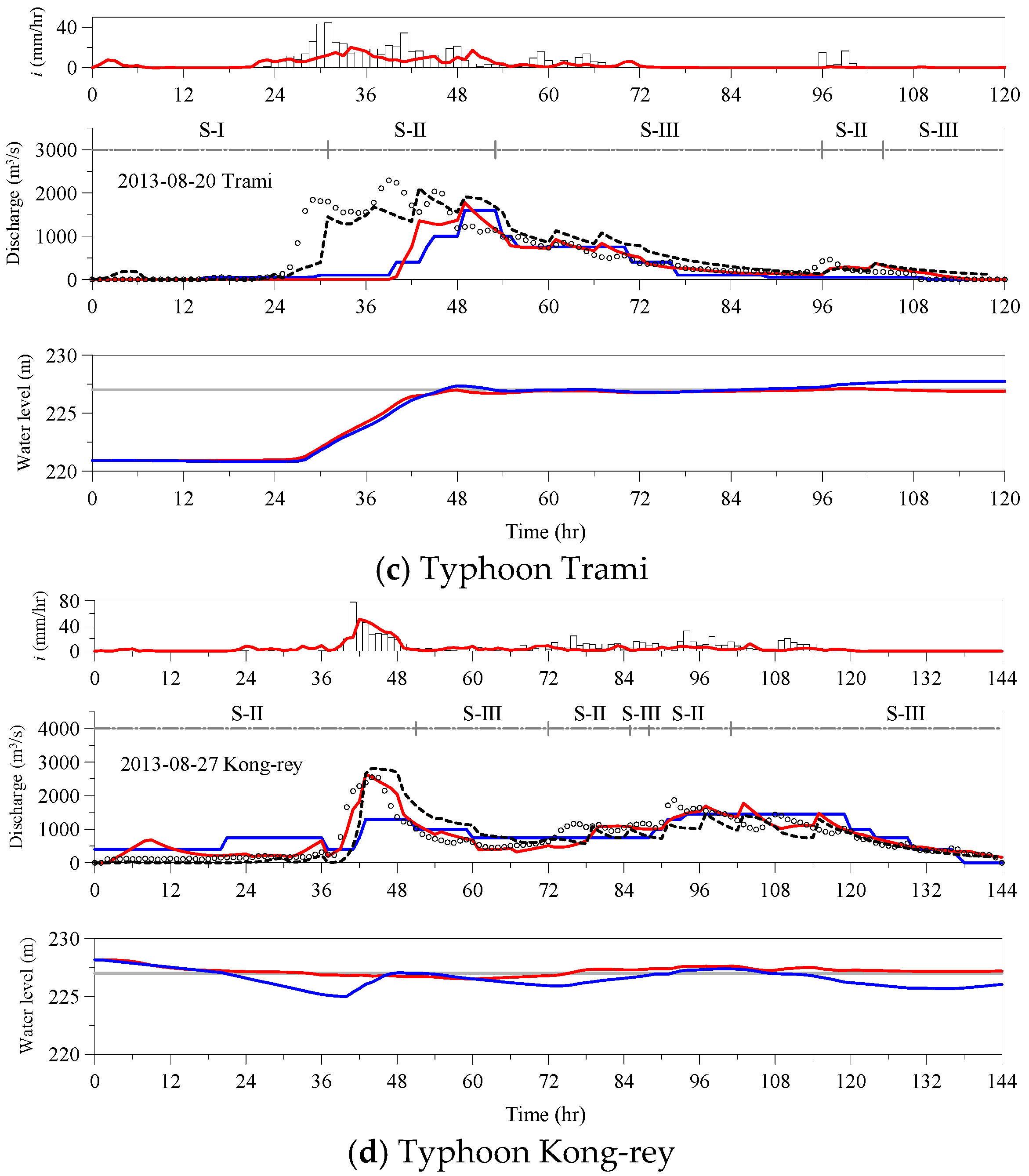

5.2. Application of Ensemble Rainfall for Real-Time Reservoir Operation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Kinematic-Wave Approximation for Runoff Travel Estimation

References

- Tu, M.-Y.; Hsu, N.-S.; Yeh, W.W.-G. Optimization of reservoir management and operation with hedging rules. J. Water Resour. Plann. Manag. 2003, 129, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, N.S.; Wei, C.-C. A multipurpose reservoir real-time operation model for flood control during typhoon invasion. J. Hydrol. 2007, 336, 282–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.-F.; Chen, G.-R.; Huang, P.-Y.; Chou, Y.-C. Support vector machine-based models for hourly reservoir inflow forecasting during typhoon-warning periods. J. Hydrol. 2009, 372, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Singh, V.P.; Lu, W.W.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhou, J.Z.; Guo, S.L. Streamflow forecast uncertainty evolution and its effect on real-time reservoir operation. J. Hydrol. 2016, 540, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Ye, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; Dai, L.; Zhou, J. Risk analysis of flood control reservoir operation considering multiple uncertainties. J. Hydrol. 2018, 565, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Lyu, L.; Cai, X. Uncovering historical reservoir operation rules and patterns: Insights from 452 large reservoirs in the contiguous United States. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Resources Agency. Key Points for the Operation of Tengwen Reservoir; Water Resources Agency: Taichung, Taiwan, 2014.

- Buizza, R. The new ECMWF variable resolution ensemble prediction system. In Book of Abstracts of the 3rd HEPEX Workshop, Stresa, Italy, 27–29 June 2007; Thielen, J., Batholmes, J., Schaake, J., Eds.; European Commission EUR22861EN; OPOCE: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, N.E.; Arribas, A.; Mylne, K.R.; Robertson, K.B.; Beare, S.E. The MOGREPS short-range ensemble prediction system. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 2008, 134, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Sakai, R.; Kyoda, M.; Komori, T.; Kadowaki, T. Typhoon ensemble prediction system developed at the Japan Meteorological Agency. Mon. Weather Rev. 2009, 137, 2592–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, T.M.; Whitaker, J.S.; Fiorino, M.; Benjamin, S.G. Global ensemble predictions of 2009’s tropical cyclones initialized with an ensemble Kalman filter. Mon. Weather Rev. 2011, 139, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, B.W. Quantitative precipitation forecasting in the UK. J. Hydrol. 2000, 239, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; DiMego, G.; Toth, Z.; Jovic, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, J.; Chuang, H.; Wang, J.; Juang, H.; Rogers, E.; et al. NCEP short-range ensemble forecast (SREF) system upgrade in 2009. In Proceedings of the 19th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction and 23rd Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting, Omaha, NE, USA, 2009; The Meteoritical Society: Chantilly, VA, USA, 2009; 4A.4. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.J.; Gallus, W.A.; Xue, M.; Kong, F. Convection-allowing and convection-parameterizing ensemble forecasts of a mesoscale convective vortex and associated severe weather environment. Weather Forecast. 2010, 25, 1052–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, T.N.; Correa-Torres, R.; Rohaly, G.; Oosterhof, D. Physical initialization and hurricane ensemble forecasts. Weather Forecast. 1997, 12, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.D.; Pu, Z.; Zhu, Y. Tracking and verification of east Atlantic tropical cyclone genesis in the NCEP global ensemble: Case studies during the NASA African monsoon multidisciplinary analyses. Weather Forecast. 2010, 25, 1397–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Emerton, R.; Duan, Q.; Wood, A.W.; Wetterhall, F.; Robertson, D.E. Ensemble flood forecasting: Current status and future opportunities. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Ren, F.; Ding, C.; Jia, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Feng, T. Improvement of the ensemble methods in the dynamical–statistical analog ensemble forecast model for landfalling typhoon precipitation. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2022, 100, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collischonn, W.; Haas, R.; Andreolli, I.; Tucci, C.E.M. Forecasting River Uruguay flow using rainfall forecasts from a regional weather-prediction model. J. Hydrol. 2005, 305, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Yen, B.C. Geomorphology and kinematic-wave based hydrograph deviation. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 1997, 123, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.C.; Sudheer, K.P.; Ramasastri, K.S. Fuzzy computing based rainfall-runoff model for real time forecasting. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Huang, J.-K. Runoff simulation considering time-varying partial contributing area based on current precipitation index. J. Hydrol. 2013, 486, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T. Generating design hydrographs by DEM assisted geomorphic runoff simulation: A case study. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Ho, Y.-H.; Chyan, Y.-J. Bridge blockage and overbank flow simulations using HEC-RAS in the Keelung River during the 2001 Nari typhoon. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 2006, 132, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-K.; Chan, Y.-H.; Lee, K.T. Real-time flood forecasting system: A case study of Hsia-Yun watershed, Taiwan. J. Hydrol. Eng. ASCE 2016, 21, 05015031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Ho, J.-Y.; Kao, H.-M.; Lin, G.-F.; Yang, T.-H. Using ensemble precipitation forecasts and a rainfall-runoff model for hourly reservoir inflow forecasting during typhoon periods. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2019, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-C.; Lee, K.T. A novel method of estimating dynamic partial contributing area for integrating subsurface flow layer into GIUH model. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, B.C.; Lee, K.T. Unit Hydrograph Derivation for Ungauged Watersheds by Stream Order Laws. J. Hydrol. Engrg. ASCE 1997, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadeed, S.; Shaheen, H.; Jayyousi, A. GIS-based KW-GIUH hydrological model of semiarid catchments: The case of Faria Catchment, Palestine. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2007, 32, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang STachikawa, Y.; Takara, K. Hydrological Model Performance Comparison through Uncertainty Recognition and Quantification. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 1179–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, D. Predicting Direct Runoff from Hilly Watershed Using Geomorphology and Stream-order Law Ratios: Case Study. J. Hydrol. Engrg. ASCE 2008, 13, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Chen, N.C.; Gartsman, B.I. Impact of stream network structure on the transition break of peak flows. J. Hydrol. 2009, 367, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Chang, C.-H. Incorporating subsurface-flow mechanism into geomorphology-based IUH modeling. J. Hydrol. 2005, 311, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Dudhia, J.; Stauffer, F. A Description of the fifth-generation Penn State/NCAR Mesoscale Model (MM5). In NCAR Technical Notes; NCAR: Boulder, CO, USA, 1994; NCAR/TN-398 STR. [Google Scholar]

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Barker, D.M.; Duda, M.G.; Huang, X.Y.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Version 3. In NCAR Technical Notes; NCAR: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008; TN-475STR; 113p. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, L.-F.; Yang, M.-J.; Lee, C.-S.; Kuo, H.-C.; Shih, D.-S.; Tsai, C.-C.; Wang, C.-J.; Chang, L.-Y.; Chen, D.Y.-C.; Feng, L.; et al. Ensemble forecasting of typhoon rainfall and floods over a mountainous watershed in Taiwan. J. Hydrol. 2013, 506, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. Analysis of runoff plot experiments with varying infiltration capacity. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1939, 20, 693–711. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.; Zhang, F. Impacts of typhoon track and island topography on the heavy rainfalls in Taiwan associated with Morakot (2009). Mon. Weather Rev. 2012, 140, 3379–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-S.; Fong, C.-T.; Hsiao, L.-F.; Yu, Y.-C.; Tzeng, C.-Y. Ensemble typhoon quantitative precipitation forecasts model in Taiwan. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, F.M.; Wooding, R.A. Overland flow and groundwater flow from a steady rainfall of finite duration. J. Geophys. Res. 1964, 69, 1531–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Typhoon | EQp | ETp | CE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (hr) | |||

| 18 June 2012 | Talim | 0.67 | 2 | 0.75 |

| 30 July 2012 | Saola | 1.26 | −1 | 0.95 |

| 20 August 2013 | Trami | 0.17 | 3 | 0.78 |

| 27 August 2013 | Kong-rey | 2.71 | −1 | 0.68 |

| Mean value | 0.79 |

| Event Date | Typhoon | Initial Water Level | Target Water Level | Final Water Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recorded | Simulated | ||||

| (m) | (m) | (m) | (m) | ||

| 18 June 2012 | Talim | 219.85 | 225 | 220.01 | 225.24 |

| 30 July 2012 | Saola | 221.11 | 225 | 224.05 | 224.73 |

| 20 August 2013 | Trami | 220.91 | 227 | 227.75 | 227.01 |

| 27 August 2013 | Kong-rey | 228.14 | 227 | 226.02 | 227.16 |

| * Mean deviation | |||||

| Event Date | Typhoon | Ensemble Mean Rainfall | Reservoir Inflow Prediction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETCR (%) | CE | EQp (%) | ETp (hr) | CE | ||

| 18 June 2012 | Talim | −20.01 | 0.75 | 5.64 | 2 | 0.67 |

| 30 July 2012 | Saola | −16.49 | 0.86 | −6.18 | 1 | 0.94 |

| 20 August 2013 | Trami | −35.25 | 0.71 | −5.53 | 4 | 0.70 |

| 27 August 2013 | Kong-rey | −17.99 | 0.76 | 19.57 | 1 | 0.52 |

| Mean value | 0.77 | 0.71 | ||||

| Event Date | Typhoon | Target Water Level | Recorded Water Level | Simulated Water Level Using Recorded Rainfall | Simulated Water Level Using Ensemble Forecast Rainfall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | (m) | (m) | (m) | ||

| 18 June 2012 | Talim | 225 | 220.01 | 225.24 | 225.42 |

| 30 July 2012 | Saola | 225 | 224.05 | 224.73 | 225.20 |

| 20 August 2013 | Trami | 227 | 227.75 | 227.01 | 227.08 |

| 27 August 2013 | Kong-rey | 227 | 226.02 | 227.16 | 227.01 |

| Mean deviation | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, K.T.; Huang, J.-K.; Huang, P.-C. Enhancing Flood Mitigation and Water Storage Through Ensemble-Based Inflow Prediction and Reservoir Optimization. Resources 2026, 15, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020021

Lee KT, Huang J-K, Huang P-C. Enhancing Flood Mitigation and Water Storage Through Ensemble-Based Inflow Prediction and Reservoir Optimization. Resources. 2026; 15(2):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020021

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Kwan Tun, Jen-Kuo Huang, and Pin-Chun Huang. 2026. "Enhancing Flood Mitigation and Water Storage Through Ensemble-Based Inflow Prediction and Reservoir Optimization" Resources 15, no. 2: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020021

APA StyleLee, K. T., Huang, J.-K., & Huang, P.-C. (2026). Enhancing Flood Mitigation and Water Storage Through Ensemble-Based Inflow Prediction and Reservoir Optimization. Resources, 15(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15020021