Abstract

Salicornia spp. is a halophytic plant with great potential in sustainable agriculture due to its ability to thrive in saline environments where conventional crops cannot grow. This study investigated Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods cultivated under two systems: hydroponics and substrate environments. The plants produced were subsequently preserved for food applications and chemically characterized within biorefinery processes. Analyses were performed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR-ATR), Ultraviolet/Visible Spectrophotometry, and Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC). The hydroponic system proved to be the most promising cultivation method, promoting superior aerial growth ranging from 14% to 50% higher than substrate-grown plants throughout the cultivation period and achieving a higher biomass yield. Regarding pigment preservation, freezing best maintained compound integrity, as observed through TLC analysis, while desiccator and vacuum storage at room temperature were most suitable for hydroponically grown samples. Under vacuum storage, pigments pheophytin A and B and chlorophyll A showed an estimated 33% higher retention compared with desiccator storage. Both cultivation methods demonstrated potential for large-scale applications, highlighting Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods as a valuable crop for saline agriculture and sustainable food production.

1. Introduction

Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods is halophyte succulent plant (plants that tolerate salinity levels) belonging to the subfamily Chenopodiaceae, which is commonly known as glasswort and sea asparagus [1]. According to the study of Bárrios et al. [1], this edible plant is notable for its ability to tolerate high-salinity concentrations in soil and water and thrive in challenging environments such as salt marshes (coastal areas periodically flooded by tides), salt flats, and muddy beaches in the temperate and subtropical regions of the world, including coastal ocean areas [1,2]. Its foliage is predominantly green, yet it may turn pinkish–red [3] or purple in autumn due to increased pigment production, which serves as a form of protection against environmental stresses, such as low temperatures (between −5 °C and −10 °C) and lower sunlight (winter season). Additionally, the day length reduction can also influence the production of these pigments. However, this color change may indicate the plant’s maturation phase, preparing it for seed reproduction and dispersion [4].

The growth and development of Salicornia plants is directly linked to photosynthetic pigments, which may vary with changes in sodium chloride (NaCl) concentration. Therefore, when these pigments decrease, it may indicate a significant increase in NaCl concentration within the plant tissues [5]. Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods contains chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phenolic pigments such as anthocyanins, which act as natural antioxidants and photoprotective agents. Carotenoid content has been quantified at approximately 8.15 µg g−1 DW, while hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives can reach 23 mg g−1 DW, both contributing to antioxidant capacity and stress tolerance [6]. Moreover, the total phenolic content can reach 67 mg GAE g−1 extract, showing strong DPPH radical scavenging activity [7]. These pigments not only enhance the plant’s adaptation to saline and light stress but also contribute to its nutritional and functional properties, supporting its potential as a health-promoting food source [6].

From a resource management standpoint, Salicornia agriculture can contribute to the circular bioeconomy by using salty water and damaged soils, lowering the demand on freshwater and fertile land resources that are normally required for crop production. Furthermore, its biomass has the potential for a variety of value-added applications, including food, feed, cosmetics, and bioenergy, improving overall resource usage efficiency and economic resilience in salty environments. The economic feasibility of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods cultivation has also been supported by several studies. By valorizing agriculture by-products, such as using Salicornia residues in aquafeed formulations (replacing up to 10% of wheat flour without affecting growth performance in Dicentrarchus labrax), farmers could generate up to EUR 14 million annually if 60,000 t of biomass residues were utilized [8]. Additionally, its potential as a bioenergy feedstock has been demonstrated, achieving methane yields of approximately 300 mL CH4 g−1 VS, comparable to conventional energy crops [9]. Although large-scale production still faces challenges related to infrastructure and processing costs, cultivation in marginal lands using saline water presents an economically viable and sustainable alternative to conventional agriculture [10].

Furthermore, the plant’s maximum maturation is achieved through the lignification process, which results in a high salt content within the plant structure (5–7 PSU). Due to these characteristics, the plant becomes a non-edible agricultural by-product. Nevertheless, there is substantial potential for its use in biorefineries, adding value and optimizing resources. In line with Bueno et al. [4], considering the source of raw material that halophyte plants, such as Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods, can provide for biorefineries, bioactive extracts were obtained from the plant shoots to be used in high-value industries. For this purpose, two approaches are possible regarding plant development: green biorefineries from partly lignified plants and more traditional lignocellulose biorefinery. The first one is focused on extracting juice and fibers from the biomass with the aim of producing biochemicals, animal feed, and biofuels such as bioethanol. The second approach involves a more conventional lignocellulose biorefinery, processing fully lignified plants after seed production [4].

The agriculture of halophyte plants has gained prominence as an alternative strategy to address future challenges of food security and nutrition, especially in the context of freshwater scarcity and climate change. Given the global prevalence of high-salinity water resources, aquatic-based food sources emerge as one of the primary focus areas in eradicating hunger and preserving the planet. Consequently, halophytic plants have become a significant attraction in terms of food supply [6]. Its unusual capacity to survive in salty and marginal areas makes it a promising contender for tackling global issues such as food security, freshwater shortage, and soil erosion. Halophyte cultivation is a sustainable option that can help enhance resource efficiency, especially in areas with high salt and limited access to arable land or freshwater.

Halophytic plants have been utilized in gourmet cuisine and the food industry as a substitute for common table salt. Due to their salty flavor, they are nutritionally appealing, as they are a source of phenolic acids, flavonoids, coumarins, vitamins, and carotenoids, which benefit human health [7]. Seeds from these plants are rich in fatty acids, increasing their nutritional value [5]. Additionally, they are also rich in sodium (Na), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), lipids, and linoleic and oleic acids [8].

The sensory property of Salicornia spp. is highly valued as it has fleshy tissues that conserve moisture, which results from increased water content in a plant. This feature is a strategic response to stress and exposure to extreme conditions, making the plant more attractive for consumption [7,8].

This study aimed to study the ex situ cultivation of the halophytic plant Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods under two controlled systems, hydroponics- and substrate-based environments, to observe their performance. This study additionally explored Salicornia maintenance methods for food and biochemical characterization, including Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR-ATR), Ultraviolet/Visible Spectrophotometry, and Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC), to help define the best plant environment for preserving its compounds for the food industry, applying low-cost and sustainable technologies.

2. Methodology, Materials, and Methods

2.1. Study Location and Collection of Plant Material

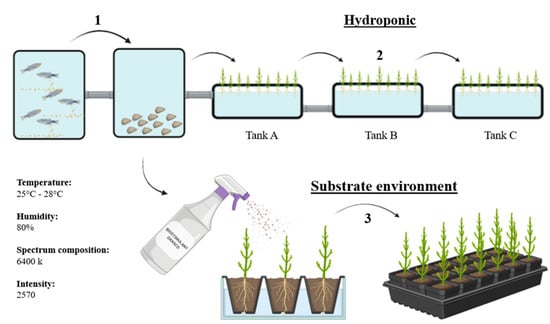

The study was conducted at Umimare, Lda, located on Morraceira Island in Figueira da Foz, Portugal (40°07′42.8″ N 8°48′14.2″ W). The trial spanned a period of 62 days under controlled laboratory and nursery conditions. Young specimens of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods were collected from a mud tank (tank 5) at the aquaculture facility. The experimental workflow, including the cultivation system, sample processing, and analytical stages, is illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Schematic survey of the experimental design, sample preparation, and plant cultivation phases. (1) Fish and oyster aquaculture tank supplying water enriched with suspended solids. This effluent is used in two plant production systems: (2) a hydroponic system composed of three sequential tanks (A, B, and C) and (3) a substrate environment irrigated with the same aquaculture water. All plant cultivations were carried out under controlled conditions. Source: Authors’ own work.

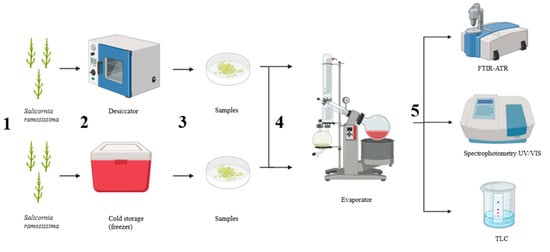

Figure 2.

Schematic survey of the experimental design, including sample preservation methods and subsequent analytical procedures. (1) Fresh Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods biomass was harvested and processed for preservation. (2) Different storage preservation approaches were tested. (3) Preserved samples were prepared for extraction. (4) Pigments and lipids were extracted using an evaporator system. (5) The resulting extracts were analyzed for compound identification and characterization. Source: Authors’ own work.

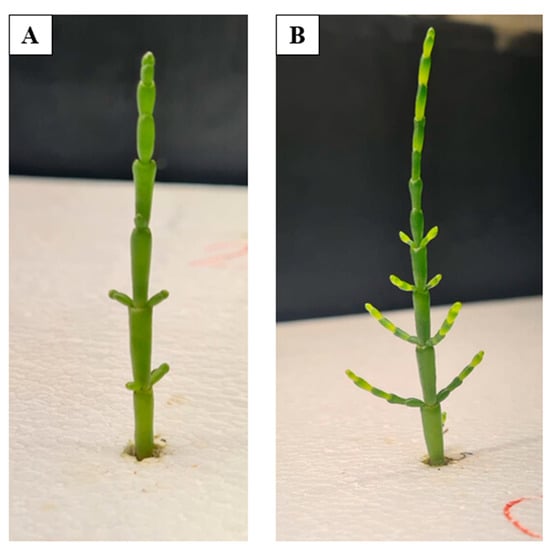

2.2. Selection of the Most Suitable Plants for the Study

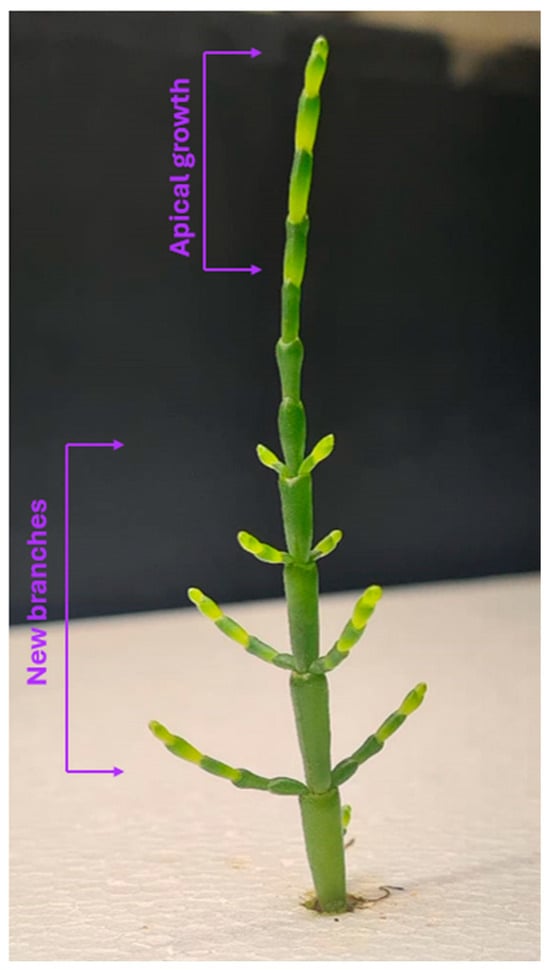

Prior to cultivation, plant material was visually screened to ensure in morphological stage consistency. Only young and structurally similar individuals were selected to minimize developmental variability. This standardization was essential for evaluating the growth behavior and comparative performance between cultivation systems. Representative examples of morphological development are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Growth and development of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods during cultivation in a hydroponic system; its apical growth and new branches. Source: Authors’ own work.

2.3. Plant Growth and Morphological Analysis

The cultivation trial was carried out over 62 days under controlled environmental conditions. Two cultivation systems were evaluated: a hydroponic setup (tank A, B, and C) with continuous aeration and a substrate environment. Plants were monitored weekly to assess their development under each system [9].

Plant growth was qualified through measurements of “plant height” and “root length”, taken using a standard ruler (Shatterless 75 S.50, Molin, Portugal). Fresh biomass (with and without roots) was recorded using an analytical precision balance (HCB 123-Highland®, Adam Equipment, Milton Keynes, UK). These measured parameters were used to compare the growth performance between cultivation systems and evaluate the influence of the biostimulant.

Environmental conditions were monitored throughout cultivation. A multiparametric portable probe (HANNA HI98289-00042, Limena, Italy) was used to measure pH, dissolved oxygen (DO%), salinity, and electrical conductivity (EC) at regular intervals. Light exposure was monitored using a digital luxmeter (UNI-T UT383S, Shenzhen, China). These measurements ensured the stability of the growing conditions and allowed the physiological responses of plants to be correlated with their respective environments.

2.3.1. Hydroponic Cultivation

The structure used for the hydroponic system included three black polypropylene plastic containers (86 cm in length × 62 cm in width × 35 cm in height) (Black rectangular container, Open Grow™, Viseu, Portugal), an aeration pump with outlets for each container, three Styrofoam boards (810 cm × 50 cm), and 95 L of oyster and tap water. The water volume consisted of 57 L of oyster tank water (salinity of 6 PSU). Additionally, 1% “Grasco” liquid solution (Umimare, Figueira da Foz, Portugal) was added (47.5 mL) weekly [10].

Initially, the containers were cleaned and disinfected using commercial gel sodium hypochlorite (2%) followed by 70% ethanol solution to ensure that there was not any contamination. The mixture of saltwater and freshwater was then added to the containers along with the aeration pump, which was prepared with three silicone tubes, each leading to the respective containers of water. Three Styrofoam boards were cut to the ideal size (80 cm × 50 cm) to fit inside the containers, and each board was perforated 13 times to insert the Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods plants so that they could remain stable with their roots in direct contact with the tank liquid media. The biostimulant, 1% Grasco, was added weekly (47.5 mL into the tanks, with 1% applied to the leaf areas using a commercial gardening sprayer) to all containers to strengthen the plants.

To better analyze the plants’ development in the cultivation system, three Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods plants were prepared in a mixture of oyster water (160.5 mL) and distilled water (75.5 mL) with an aeration system but without the addition of the biostimulant; these were considered as control plants. Control plants were used as testimony with the aim of comparing the plants’ responses when biostimulant was added to the water, allowing us to understand any potential influence of the biostimulant on the plants’ growth.

For the analysis of parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen percentage, salinity, and electrical conductivity, the portable multiparametric device HANNA, model HI9829-00042 (Limena, Italy), was used. For light analysis, a LINI-T digital luxmeter, model UT383S (Shenzhen, China), was employed.

2.3.2. Substrate Environment Cultivation

A substrate environment is a carefully prepared growing medium designed to promote seed germination and early plant development; however, in this study, Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods cuttings were used instead of seeds.

For the substrate environment cultivation, a black plastic box (52 cm length × 42 cm width × 28 cm height) (Essentials electric propagator, Stewart, UK) with a transparent lid featuring an opening on the top for ventilation was used. A Styrofoam board (44.7 cm in length × 33.5 cm in width × 6 cm in height) pre-drilled with 234 holes was inserted inside the black plastic box. Before use, all materials were cleaned and disinfected using commercial gel sodium hypochlorite (2%) followed by 70% ethanol solution.

The substrate mixture was prepared using clay soil, sand, and saline water. The clay soil was collected from the lateral side of an aquaculture tank (40°07′38.0″ N 8°49′14.8″ W) at Umimare, Lda, in Figueira da Foz. The clay soil was then mixed with sandy soil, retrieved from the bottom from the same aquaculture tank (1:1 m:m), and estuarine water (15 PSU), and was placed into the 21-hole commercial perforated plant cuvette which held the Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods plants. The substrate environment system is an organized cultivation method in which a specially prepared growing medium provides the optimal conditions for early plant development before transplantation or further growth. This substrate environment system had 1% “Grasco” biostimulant, (GR) commercial algal extract under IP protection from UC (Umimare, Figueira da Foz, Portugal), which was added weekly (2.6 µL), as in the hydroponic system, and was conducted in a closed system.

A negative control was also implemented for this system, a single sample of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods with no biostimulant added. The negative control was initially set up with 236 mL of liquid media, consisting of 160.5 mL of distilled water and 75.5 mL of saltwater, prepared in the laboratory (with a salinity of 11 PSU), resulting in a final salinity of 6 PSU. During the experiment, we realized that the plants did not react to the negative control and there was a need to adjust this liquid media, decreasing it by half its volume (80.25 mL of distilled water and 37.75 mL of saltwater), also performed in the laboratory (with a salinity of 10 PSU).

2.4. Biomass Conservation Methods

Some weak plants were substituted on the first day of the experiment, before the weekly measurements began. After that, no plants were replaced and the experiment remained intact.

The Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods specimens were initially weighed both with and without roots in their fresh form and were categorized according to their cultivation environment (hydroponic system and substrate environment) to assess the plants’ development. For this purpose, three plants from both cultivation environments were selected and introduced using four different conservation methods: storage at room temperature without vacuum, storage at room temperature with vacuum, cold storage (−20 °C), and storage in a desiccator using Petri dishes. The purpose was to compare how these plants behave in these conservation environments.

After selecting and categorizing the plants, a conservation period was established for each method (storage at room temperature without vacuum, storage at room temperature with vacuum, cold storage (−20 °C), and storage in a desiccator using Petri dishes). A plastic bag for food was used for the vacuum procedure, followed by analyses using FTIR-ATR, a UV/VIS Spectrophotometer, and finally, Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) analysis, as described by Mamede et al. [9].

2.4.1. Storage at Room Temperature Without Vacuum

The purpose of conserving a plant at room temperature without vacuum is to analyze how the plant’s characteristics are preserved under these conditions. This is particularly relevant for studies involving the analysis of plant chemical compounds and plants’ responses to environmental stresses.

For conservation at room temperature without vacuum, the analysis period was established based on the time between harvesting and the fifth day, when visible physical changes occur in the plant.

2.4.2. Storage at Room Temperature Under Vacuum

The use of a vacuum in plant conservation introduces several changes compared to the process without a vacuum. When vacuuming is applied, the oxidation process of the plant is prevented, helping to preserve pigments, lipids, bioactive compounds, thereby better maintaining the plant’s chemical properties [11]. It also reduces the rate of decomposition as the absence of air inhibits the growth of aerobic microorganisms, which in turn slows down the plant’s breakdown, extending the sample’s lifespan. By minimizing the effects of the external environment, the plant material remains close to its original condition.

In this maintenance method, the vacuum-sealed bags were exposed to LED light at 2693 lux for 5 days, until they exhibited physical changes. The procedure followed here was identical to that described in Section 2.4.1.

2.4.3. Vacuum Cold Storage

This method of conservation offers additional benefits beyond those previously mentioned, especially for biological samples such as Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods. When vacuum sealing is combined with extremely low temperature in a freezer, it virtually halts enzymatic and microbial activity, keeping the plant in an almost-unchanged state. Volatile and sensitive compounds are retained in near-original form, and the extreme cold helps maintain the integrity of the plant’s molecular structure [12].

The samples were placed in a freezer at −20 °C for 5 days. After the cold storage, the experiments proceeded in the same manner as the previous maintenance methods, and the samples were maintained at room temperature.

2.4.4. Storage in a Desiccator Using Petri Dishes

Unlike the other methods, conservation in a dry storage instrument offers distinct advantages and effects. Controlled drying allows the process to proceed gradually, which helps to reduce microbial and enzymatic activity, though it is less effective than freezing [13]. However, as it occurs relatively quickly, it minimizes the risk of mold formation on the sample. As the plant water content decreases, certain compounds, such as secondary metabolites, may become more concentrated, which is beneficial for chemical analysis [14]. The maintenance in the oven was carried out in Petri dishes for a period of 2 days at 60 °C, a temperature commonly used for drying plants.

2.5. Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods Characterization

After the storage period, all the samples from the plates were dried and weighed on plates at 60 °C for 48 h to obtain the differences between the initial and final weights. The samples were milled with a commercial miller, CASO Design, and the Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods was introduced into test tubes for analysis using the FTIR-ATR technique.

Sample characterization was conducted as described by [12], by grinding the plants. A sequential extraction technique was used to separate non-polar (lipids) and polar (phenolics and pigments) compounds for further study, as described in [15]. This is essential for accurately identifying and quantifying the various metabolites present, as they have distinct polarities and interact differently with solvents and stationary phases in the analytical techniques. For the extraction of non-polar compounds, the powdered Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods sample was immersed in hexane (1:20 w:v) with constant agitation for 40 min at 130 rpm using an orbital shaker (Orbital Shaker, ORB-B2). Vacuum filtration was performed using a Gooch funnel (G3), and the samples were evaporated (rotary evaporator: 2600000, Witeg, Wertheim am Main, Germany) until all the pigments adhered to the surface of the round-bottom flask. The second step consisted of the extraction of polar compounds using methanol and the Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods residue (1:20 initial weight: v) recovered from the first extraction. Vacuum filtration was performed using a Gooch funnel (G3), and the samples were evaporated (rotary evaporator: 2600000, Witeg, Germany) until all the pigments adhered to the surface of the round-bottom flask. The pigments were resuspended again with 2 mL of the initial solvent.

For UV/VIS Spectrophotometry analysis, a dilution of 1:10 was prepared, consisting of 0.3 mL of methanol sample after biorefining and 2 mL of pure methanol, resulting in a total of 3 mL of this mixture, to achieve the optimal volume for the equipment analysis.

2.5.1. FTIR-ATR

FTIR-ATR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance) analysis is an analytical technique that uses a crystal to measure the infrared absorption of a sample in direct contact, thereby allowing the analysis of its chemical composition. This is a rapid technique noted for its ability to identify specific molecular vibration modes, thereby obtaining quantitative results [16]. The FTIR-ATR analysis was performed following the method described by [17], used for the identification of chemical bonds and organic compounds.

This analysis was conducted after grinding the samples obtained from the dried plants using a grinder (Miller, CASO Design, Caso, Arnsberg, Germany). The samples were then subjected to direct analysis using the equipment (Bruker ALPHA II FTIR Spectrometer, 2023) (Karlsruhe, Germany). The spectra obtained from this analysis were recorded over a range of 400 to 4000 cm−1, each with a resolution of 5 cm−1 [12].

2.5.2. UV/VIS Spectrophotometry

Ultraviolet/Visible Spectrophotometer analysis is an analytical technique that measures the substance absorption capacity in the ultraviolet (UV) region (200–400 nm) and the visible (VIS) light region (400–700 nm) of the spectrum. It uses light to determine which wavelengths (colors) a substance absorbs and to measure turbidity, thereby quantifying the amount of chemical substances in a sample [17]. The study cited in Section 2.5.1 identifies the bioactive substances present and notes that these compounds exhibit UV absorption.

For qualitative and quantitative analyses of pigments, a spectrophotometer was used (VWR® UV-6300PC, VWR, Lutterworth, UK). It was necessary to dilute the sample extracts obtained with acetone (1:4 | 500 µL:2 mL) to achieve the best overall results. Subsequently, the analysis involved interpreting the graphs and identifying the compounds.

2.5.3. TLC

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) is a technique used for the separation and identification of the components in a mixture based on their different migration rates on an adsorbent layer, such as silica gel, applied to a flat plate [18]. According to Hamdan et al., 2024 [17], the TLC method is used to identify the pigments present in the analyzed samples.

For chromatography analysis, ground samples of dried plant material (0.100 g of biomass) were used [17] and combined with 20 mL of a methanol (9:1) solution. The mixture was continuously agitated (shaker: Orbital Shaker, ORB-B2—Labbox, Barcelona, Spain) at 130 rpm for 40 min. After that, the solution was vacuum-filtered using a Gooch funnel (rotary evaporator: 2600000, Witeg, Germany) until the pigments adhered to the flask. To obtain a concentrated extract, the pigments were redissolved in 2 mL of methanol (9:1) solution.

Subsequently, silica gel plates for TLC analysis (ALUGRAM SIL-G Sheets-MACHEREY-NAGEL, Duren, Germany) were activated at 120 °C for 5 min in a forced-air oven (oven: Heraeus Raypa DAF-135, Barcelona, Spain). Following activation, 20 µL of each concentrated extract was applied to the plates. The plates were developed in a chromatography chamber using a petroleum ether/acetone (7:3 v/v) solution as the elution solvent until the solvent front reached a height of 10 cm. The plates were then removed with a tweezer, and the solvent was allowed to evaporate at room temperature (25 °C). The pigments were identified by calculating the retention factor (Rf) (Rf = distance traveled by the compound (cm)/distance traveled by the eluent) and comparing these values with previously published data in the literature.

2.6. Data Analysis

Before being analyzed, the data were checked for normality and variance homogeneity. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine statistically significant differences between treatments for each measured variable. Differences were judged statistically significant at p < 0.05. When a significant impact was found, the Holm–Sidak test was used to do post hoc multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed with the SigmaPlot version 14.0.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Cultivation Method

The physiochemical parameters monitored during cultivation remained within the ranges suitable for halophytic plant growth in both systems. pH values were close to neutral, dissolved oxygen levels indicated adequate oxygen availability, and electrical conductivity reflected saline conditions typical for Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods.

Although differences were observed between the hydroponic tanks and the substrate environments, these variations did not represent limiting factors for plant development. Overall, the data presented in Table 1 indicate that both systems provided comparable growing conditions, allowing subsequent differences in plant performance to be attributed mainly to the cultivation strategy rather than to environmental constraints.

Table 1.

The parameters of pH, dissolved oxygen DO (%), and electrical conductivity (EC) in the different tanks and substrate environments. DO (%) serves as an indicator of oxygen availability in water, which is essential for aerobic biological processes. Tanks A, B, and C exhibited levels consistent with adequate oxygenation. Substrate environments showed lower values, possibly due to reduced photosynthetic activity and increased respiratory consumption.

3.2. Hydroponic Systems Compared with Substrate Environments

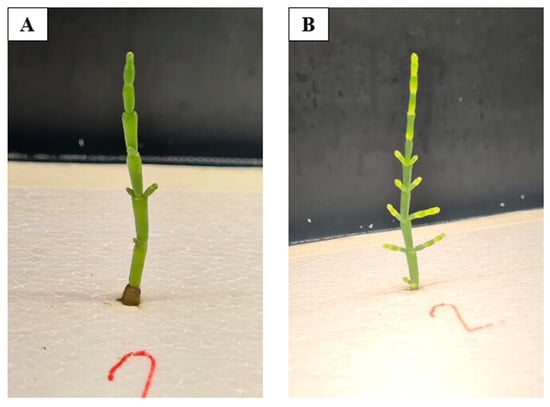

In both cultivation environments, Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods plants exhibited significant morphological development throughout the experiment. It was observed that plants treated with the 1% “Grasco” and the respective negative controls showed promising development (Figure 4 and Figure 5). However, plants that received the biostimulant demonstrated faster growth and more robust branch development, as well as enhanced photosynthetic protection [10], which is one of the beneficial effects attributed to this biostimulant.

Figure 4.

Development of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods during hydroponic cultivation in tank B. The images depict the plant’s progression from the first week of the experiment (A) to the final week (B). Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 5.

Development of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods during hydroponic cultivation in tank C. The images depict the plant’s progression from the first week of the experiment (A) to the final week (B). Source: Authors’ own work.

It was noted that the plants developed in similar environments for four weeks, showing remarkable growth in both the aerial parts and the roots as well as the emergence of new branches (Figure 3). Plant growth was proportional across all observations made throughout the procedure.

3.3. Morphological Data

Plants were cultivated under controlled conditions at 25 °C and with a pH of around 7–8. To evaluate the growth and development of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods, measurements were conducted for four weeks to compare the growth patterns between the hydroponic and substrate environment systems. Plant height (aerial growth) and root length were used as primary indicators of biomass development over time, while length-to-weight ratios were used to assess biomass allocation at the end of the cultivation period.

Plant growth data were studied by comparing the growing methods at each time point (week). This strategy enabled the study of culture method impacts independent of temporal development patterns. The Materials and Methods Section as well as the image legends contain details on the statistical tests employed.

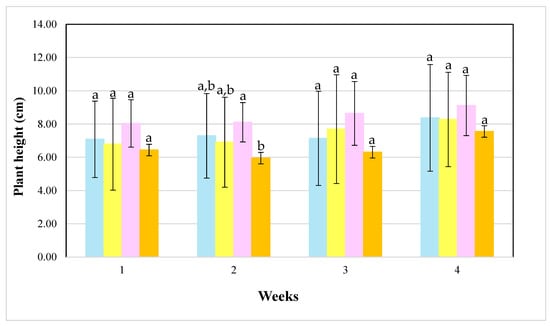

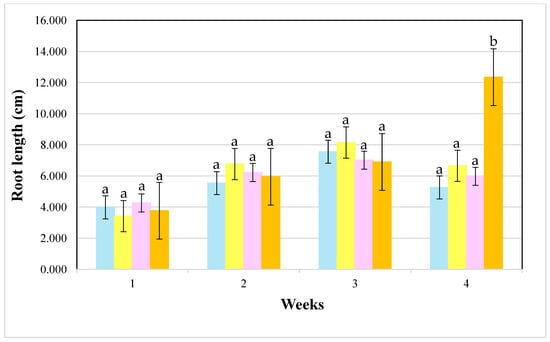

Figure 6 shows the temporal evolution of growth. During the first week, no significant differences were observed among the cultivation systems, indicating similar initial adaptation. From the second week onward, the hydroponically cultivated plants exhibited a more pronounced increase in plant height, particularly in Tank C. By weeks 3 and 4, the plants grown in Tank C reached the highest average aerial height, while substrate-grown plants consistently showed lower values, though without being statistically different.

Figure 6.

Averages of salicornia plant aerial growth during four weeks of cultivation. The blue bars represent salicornia plants in tank A, the yellow in tank B, the pink in tank C, and orange in the substrate (same letters show no statistical differences between the parameters (p > 0.05)). One-way ANOVA comparing treatments per week separately (isolating week 1, week 2, week 3, and week 4) (Holm–Sidak test to identify the differences).

Root growth followed a different pattern (Figure 7). While root length increased over time in all systems, the substrate-grown plants showed a higher increase in root development by week 4, reaching significantly higher root lengths than the hydroponically cultivated plants. In contrast, the hydroponic system exhibited more moderate and uniform root growth throughout the experiment, with no significant differences among tanks at the end of the cultivation period.

Figure 7.

Averages of plant root growth during four weeks of cultivation. The blue bars represent salicornia plants in tank A, the yellow in tank B, the pink in tank C, and orange in the substrate (same letters show no statistical differences between the parameters (p > 0.05)). One-way ANOVA comparing treatments per week separately (isolating week 1, week 2, week 3, and week 4) (Holm–Sidak test to identify the differences).

The contrasting trends observed in Figure 6 and Figure 7 indicate some distinct biomass allocation strategies between cultivation systems (week 4 in the roots). Hydroponic cultivations may have favored aerial biomass development (although they were not statistically different), whereas the substrate environment promoted greater investment in root growth.

Additionally, plant responses to biostimulant application were evaluated to assess its potential effects on biomass and root development. All systems showed a progressive increase in plant length throughout the cultivation period, indicating that the applied conditions supported the continuous growth of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods.

The morphological ratios calculated at the end of the experiment (Table 2) highlight differences in biomass allocation among the cultivation systems. Tank A and C exhibited higher aerial length-to-weight ratios, indicating a greater investment in aerial biomass and development with a balanced aerial-to-root ratio, reflecting more proportional growth. In contrast, Tank B presented a markedly higher root length-to-weight ratio, indicating pronounced root elongation accompanied by a higher overall plant weight.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of the length and weight ratios between the aerial part (AP) and the root (R) for the different samples of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods (measured at the end of the cultivation period): tank A, tank B, tank C, and substrate environment.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing aerial and root growth between the hydroponic system and substrate environment revealed no statistically significant difference (p = 0.280 > 0.05), indicating an overall growth equivalence among systems. Nevertheless, the morphological ratios reveal consistent differences in biomass allocation patterns, with the hydroponic cultivation favoring aerial development and the substrate environment cultivation promoting root growth.

3.4. FTIR-ATR Analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR-ATR) is a technique used to measure infrared absorption in samples in direct contact with a crystal, allowing for the analysis of chemical composition due to the ability to identify specific molecular vibration modes.

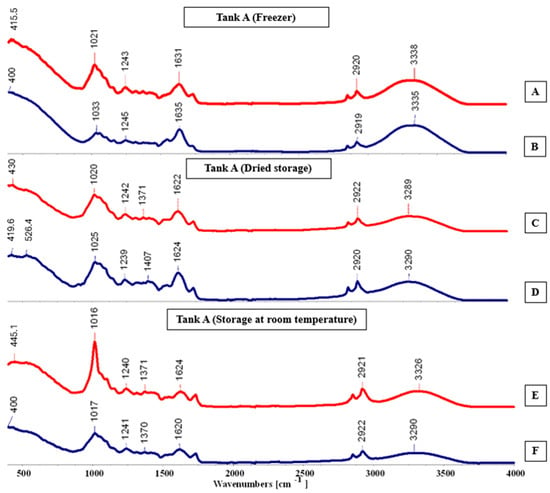

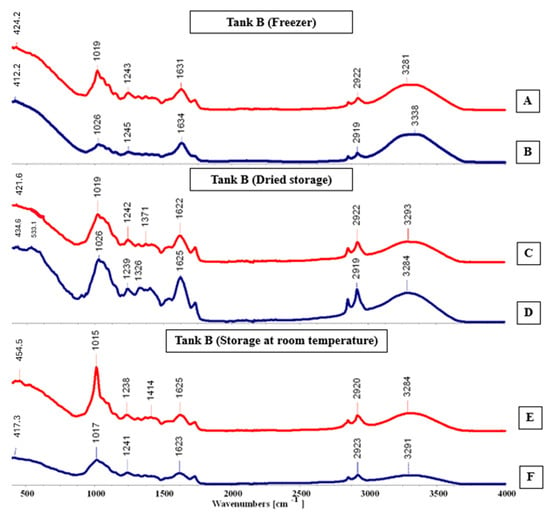

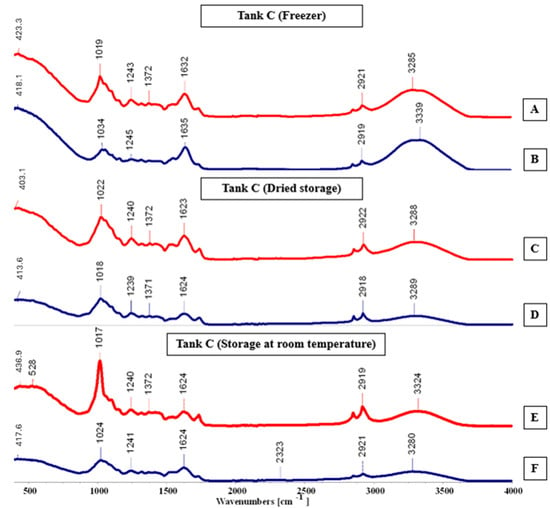

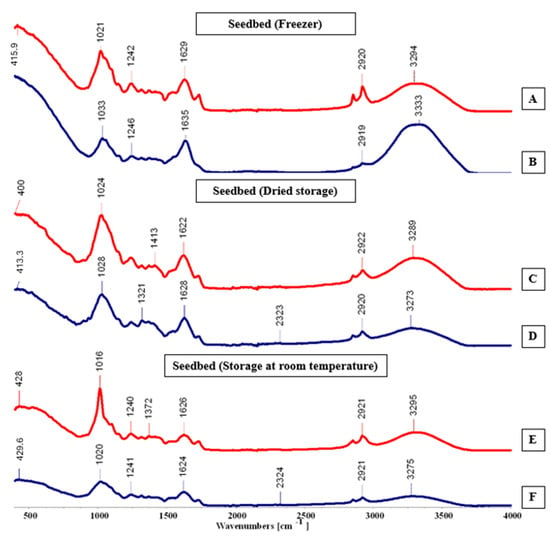

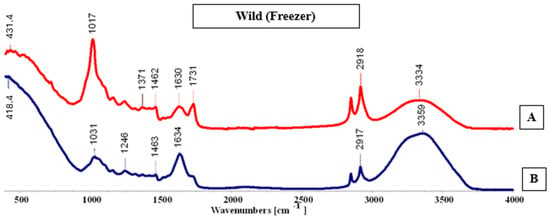

This analysis aims to provide a detailed understanding of the chemical composition of the samples through infrared absorption and molecular vibrations. For the food industry, it is valuable due to its speed, simplicity, and the accuracy of results [19]. The FTIR-ATR spectra of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods can be analyzed within the range of 400–4000 cm−1, as shown in all spectra (A-F) in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, along with the compounds identified in each specified interval, according to the study by [20] and Table 3.

Figure 8.

FTIR-ATR spectra (A–F) for tank A, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

Figure 9.

FTIR-ATR spectra (A–F) for tank B, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

Figure 10.

FTIR-ATR spectra (A–F) for tank C, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

Figure 11.

FTIR-ATR spectra (A–F) for the substrate environment, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

Figure 12.

FTIR-ATR spectra (A,B) for the wild plant, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

Table 3.

Analysis of the peaks in the FTIR-ATR spectra for Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods. The analysis is presented across different graphs, numbered 1 to 13, each corresponding to a specific band range. For each band range, the chemical vibrations and the specification of the identified bonds are indicated. The numbers in the band interval column represent the locations of the chemical vibrations, which result in the identification of the chemical bonds and thus provide the specification of the bond, indicating the compounds present in the sample [9,20].

In the range of 400–1800 cm−1, known as the “fingerprint” region, is where the identification of the analyzed sample occurs. In the spectral analysis for Tank A, it was observed that there were more peaks in the “Dried storage” and “Room temperature” conservation types, particularly in spectra C, D, E, and F, with more pronounced peaks in spectrum E. As shown in Figure 8, distinct absorption peaks can also be observed at 445.1, 1033, and 1407 cm−1, corresponding to the characteristic vibrational modes of functional groups present in the analyzed material.

In tank B (Figure 9), significant differences were observed among the spectra, with spectrum E displaying the most intense and well-defined peaks, whereas spectrum B exhibited the weakest signal. There were also clear variations in the number and distribution of peaks across all spectra. Distinct absorption bands were detected at 454.5, 1326, 1414, and 3338 cm−1, which correspond to the characteristic molecular vibrations associated with different chemical groups.

In tank C (Figure 10), peaks in spectrum E were the most prominent, showing greater sharpness and intensity, while those in spectrum F were less intense and fewer in number. The remaining spectra exhibited a similar pattern, except for spectrum B, which presented a noticeably smaller number of peaks. The main absorption bands identified occurred at 403.1, 528, 2323, and 3339 cm−1, indicating the presence of specific functional groups within the analyzed material.

In spectrum E (Figure 11), the peaks appeared more pronounced and displayed higher intensity and frequency when compared with the other spectra. Spectrum B, however, showed fewer peaks, consistent with the patterns observed in Tanks A and B. Notable absorption bands were found at 400, 1321, and 1372 cm−1, reflecting molecular vibrations typical of organic compounds found in Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods.

In the sample containing wild Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods collected after the cultivation period (Figure 12), no major differences were detected when compared with the cultivated samples. Spectrum A exhibited the most pronounced peaks, with a higher overall number of absorption bands throughout the analysis. Characteristic peaks were observed at 1246 and 1731 cm−1, suggesting the presence of similar functional groups to those identified in the cultivated plants.

Similarities were observed when the cultivation method was compared between the plants (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). Therefore, it was possible to obtain similar results using different conservation and cultivation approaches, and it was possible to identify the chemical compounds present in the samples (Table 3).

3.5. UV/VIS Spectrophotometry

Ultraviolet/Visible (UV/VIS) Spectrophotometry is an analytical technique used to measure the absorption of electromagnetic radiation by substances within the ultraviolet (200–400 nm) and visible (400–800 nm) spectral regions. By determining the wavelength of light absorbed by a sample, this method provides valuable information regarding the color characteristics, turbidity, and concentrations of the chemical compounds present. Each pigment exhibits a distinct absorption profile with characteristic peaks at specific wavelengths, which enables both its identification and quantitative determination. The resulting absorption spectra are therefore fundamental for elucidating the chemical composition of complex biological matrices.

In the present study, UV/VIS Spectrophotometry was employed for the quantitative analysis of leaf pigments extracted from Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods. Following Thin-Layer Chromatography, which was performed using a UV-3100PC spectrophotometer (VWR, Lutterworth, UK), scanning was conducted at 665.2 nm, 652.4 nm, 535 nm, and 470 nm. The concentrations of chlorophyll A and B and carotenoids (expressed in mg/100 g) were subsequently determined using standard equations. The choice of solvent system and dilution ratio ensured optimal spectral resolution and reproducibility [17].

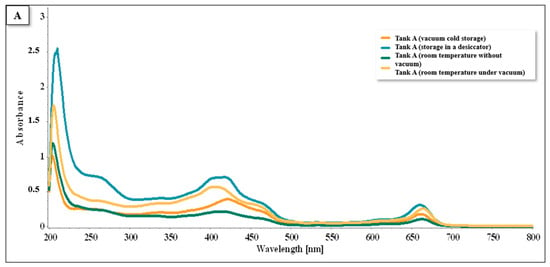

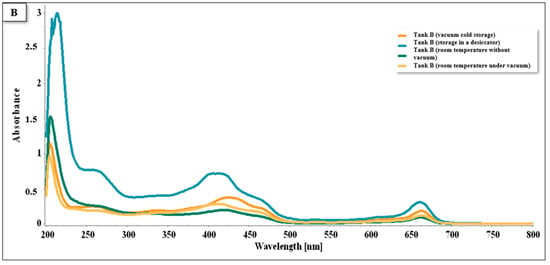

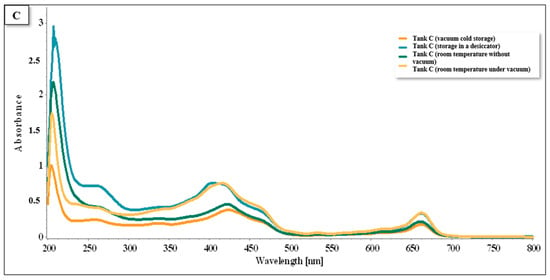

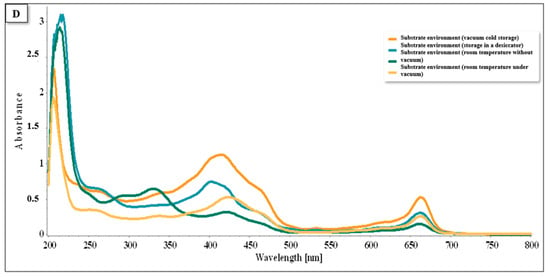

The spectrophotometric assessment of the aerial parts of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods encompassed two spectral regions: the ultraviolet domain (200–400 nm) and the visible domain (400–800 nm). The resulting spectra displayed comparable profiles across all cultivation methods, revealing the consistent presence of flavonoids, chlorophylls A and B, and carotenoids.

Regarding tank A (Figure 13), flavonoids were found in the range of 200–280 nm, and pigments such as carotenoids and chlorophylls A and B were present in the range of 400–500 nm, with chlorophylls A and B also detected between 630 and 700 nm. The conservation method with the greatest predominance throughout the graph was the oven method.

Figure 13.

Spectra UV/VIS for tank A, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

In the samples from tank B (Figure 14), the presence of flavonoids was observed in the range of 200–280 nm, carotenoids and chlorophylls A and B in the range of 400–450 nm, and chlorophylls A and B in the intervals of 640–685 nm. Like in tank A, the oven method was also the most prominent conservation method observed.

Figure 14.

Spectra UV/VIS for tank B, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

Analyzing tank C (Figure 15), we noted the presence of flavonoids, chlorophylls A and B, and carotenoids in the same intervals (Figure 13 and Figure 14). However, there is a difference in the conservation methods. While in the previous graph the highest peak was exclusively associated with oven conservation, in graph C, significant peaks are observed for both the oven conservation and vacuum environment temperature.

Figure 15.

Spectra UV/VIS for tank C, cultivated in the hydroponic system.

In Figure 16, which refers to cultivation in the seed bed, the peaks in the spectra were more pronounced and intense compared to those in the other graphs. This showed that cold conservation through freezing was the most prominent method, with the presence of flavonoids in the range of 220–280 nm, carotenoids and chlorophylls A and B between 350 and 470 nm, and only chlorophylls A and B between 400 and 700 nm.

Figure 16.

Spectra UV/VIS of the plants cultivated in the substrate environment system.

Table 4 clearly demonstrates that in acetone, there is a higher concentration of pigments than in methanol, where the substrate environment and conservation in a desiccator formed the best method for biomass production for pigment extraction using acetone.

Table 4.

Identification of chlorophylls A and B and carotenoids in Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods samples, including the calculation of the retention factor (RF). The results for each sample are presented in the following table, which is organized by cultivation method.

3.6. TLC

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) is a technique used for the separation and identification of components in complex mixtures. This method is valuable in phytochemical studies for analyzing pigments and other substances in plants. Pigment identification was conducted by calculating the retention factor (RF) for each component. This indicator is fundamental for characterizing components, as each substance has a characteristic RF under specific solvent and adsorbent conditions [12].

For the chromatography analysis (TLC), plates were subjected to four different conditions: in desiccator, at environmental temperature with and without vacuum, and finally, under cold conditions. The samples in the plates were labeled according to their cultivation location: sample A refers to tank A, sample B to tank B, and so on, with the final sample labeled “Wild” for the wild sample of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods collected after cultivation to compare the species in its natural environment with the plants grown under controlled conditions.

In a general analysis of the TLC plates, a significant presence of pigments was observed on plate C, where pigmentation was quite apparent, with the highest concentration found in sample “S” from the substrate environment, which showed the greatest quantity of pigments detected. This observation suggests that conservation at environmental temperature with vacuum was the most effective in maintaining pigment integrity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Identification of pigments in Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods samples, including the calculation of the retention factor (RF). The results for each sample are presented in the following table, which is organized by cultivation method.

Plates A, B, and D also showed pigmentation, with plate B exhibiting more noticeable pigments compared to plates A and D. The analysis of plates A and D, despite showing some pigmentation, suggests potential degradation of the biological material or less effective conservations methods, resulting in less pronounced pigmentation compared to the other samples.

The sample “Wild” was conserved under cold conditions. However, this sample did not present a pigment concentration sufficient for visualization.

4. Discussion

The shortage of freshwater, climate change, and rising soil salinity as a result of unsustainable farming methods have intensified global interest in halophyte-based agriculture as a promising alternative for sustainable food production and resource management. However, despite the scientific world’s recognition of the importance of selecting and cultivating a viable halophyte crop plant, most research has been mainly concentrated on disclosing the presence of extreme salt tolerance, often neglecting their agronomic and commercial potential. As halophytes differ greatly in terms of salt tolerance ranges and in growth rates, it is essential to determine the optimal salinity threshold for maximum yield before establishing cultivation protocols. Wild-collected plant material frequently exhibits limited consistency, variable product quality, and unstable availability and is restricted to natural growth periods and local species abundance [21,22].

There is a general lack of information in the literature concerning both the dynamics and biochemical composition of Salicornia spp. Halophytes typically possess a high ash and mineral content, traits linked to their saline habitats and adaptative tolerance mechanisms. The main physiological challenge for plants in saline environments is maintaining water uptake, which requires lowering tissue water potential relative to the surrounding environment [23,24]. This adjustment is achieved through osmotic mechanisms such as reduced cell size or the accumulation of solutes. In dicotyledonous halophytes, such as Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods, osmotic adjustment primarily results from the accumulation of inorganic ions—particularly sodium and chloride—within vacuoles, allowing the plant to sustain turgor and metabolic function under saline stress. Thus, the salinity level of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods in its natural habitat is significantly higher than that to which it was subjected in this experiment. Plants exhibited a positive response, including apical and root growth and branching [4,23,24].. Therefore, the salinity level for cultivating this halophyte was not critical, given that it thrived in water with salinity levels between 5 and 7 PSU, which is within its natural environmental conditions. These plants can tolerate a range of salinity levels, from 5 to 37 PSU [25].

The biostimulant 1% “Grasco” (Umimare, Figueira da Foz, Portugal) was applied as a spray on the plants. This biostimulant, 1% “Grasco”, provided sufficient nutrients for the plants to survive, develop, and grow uniformly. During the trial, there was a fungal attack on the plants, but the plants were not disturbed by them and continued to grow. Three days after spraying was applied, when boxes were open to ventilate, no fungi were observed on the plants. This showed that the fungi appeared due to the high humidity in the substrate environment box, when boxes were half open, but also that “Grasco” application influenced the reduction of the fungi. The gourmet vegetable and herb industry expects the best quality foods. In addition, plant products should have healthy performance in terms of freshness and color and be presented to consumers with a uniform threshold that results from high-quality maintenance modes [21].

Maintenance methods exhibited significant variations depending on the plant cultivation technique. Among the tested approaches, oven drying proved most effective for hydroponically cultivated plants, while room temperature vacuum storage (Tank C) also maintained satisfactory quality. Conversely, plants grown in the substrate environment responded better to cold preservation, showing superior compound stability. These results indicate that maintenance efficiency was influenced by the cultivation system, and that distinct maintenance techniques may optimize pigment and compound retention according to biomass origin.

Each molecule has a unique set of vibrational modes, resulting in a specific absorption pattern in the infrared spectrum. By comparing the obtained spectra with the existing literature, the main chemical constituents of the samples were identified using FTIR-ATR, confirming the presence of characteristic plant compounds such as flavonoids, carotenoids, chlorophylls A and B, polysaccharides, and alcohols [9].

Values obtained with Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) were compared with the literature data [9], allowing for the precise identification and qualitative assessment of the pigment profile in Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods. TLC results confirmed the presence of key photosynthetic pigments—chlorophylls, carotenoids, and flavonoids—with variations in concentration depending on the cultivation environment. Samples derived from the substrate system exhibited higher pigment intensities, suggesting that moderate soil contact and nutrient exchange may enhance pigment biosynthesis. These findings indicate that both the cultivation medium and maintenance method directly influence pigment stability and retention. The hydroponically cultivated plants preserved through oven drying or vacuum storage maintained pigment integrity more effectively, whereas freezing proved optimal for the substrate-grown samples, minimizing degradation.

The comparative pigment distribution observed in this study aligns with previous findings [4,26], which report that the total carotenoid content in Salicornia spp. is highly variable across experiments, largely depending on environmental conditions such as light intensity, temperature, and salinity. Carotenoids act as non-enzymatic antioxidants, protecting the photosynthetic apparatus from oxidative stress, and their concentrations typically increase as part of the plant’s adaptive response to environmental stimuli. The differences detected between cultivation systems in this experiment reinforce the idea that pigment composition—particularly carotenoid and flavonoid content—serves as a sensitive biomarker of physiological adaptation in halophytes. Carotenoids and chlorophylls play crucial roles not only in salt tolerance mechanisms but also in the optimization of photosynthetic efficiency among species of the Amaranthaceae family [4,26,27,28]. In this study, moderate salinity levels (5–7 PSU) appeared to sustain pigment production without imposing stress, supporting the balanced synthesis of chlorophylls and carotenoids. This balance contributed to the stable growth rates observed, indicating that pigment accumulation served both a protective and a functional role in maintaining photosynthetic activity.

Consistent with [29], our results revealed a clear distribution pattern among the pigments: flavonoids were most abundant, followed by chlorophylls and carotenoids. Chlorophyll levels increased with plant maturity, while carotenoids showed variable expression across developmental stages—an expected pattern for halophytes adapting to fluctuating environmental conditions. Together, these compounds facilitate the absorption of light across different wavelengths, ensuring optimal photosynthetic performance even under saline stress.

The hydroponic system proved to be the most advantageous cultivation method when compared with the substrate environment, primarily due to its superior biomass production. Since this study is focused on exploring Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods’ potential as an edible crop, biomass yield represents a decisive parameter for food industry applications. The plants that were grown hydroponically exhibited higher aerial growth, more consistent morphology, and faster development rates, confirming the system’s efficiency in nutrient delivery and water management. Moreover, among all the conservation methods tested, freezing was the most effective for maintaining pigment and compound stability, as it prevented oxidative degradation and color loss. Therefore, the combination of hydroponic cultivation with freezing maintenance can be regarded as the optimal strategy for maximizing both the productive and nutritional potential of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods.

Beyond pigment characterization, this study demonstrated that Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods cultivated under hydroponic conditions enhanced aerial biomass production and vigorous root systems, highlighting its potential as a viable crop for sustainable agriculture. This dual advantage—efficient root anchorage and aerial biomass yield—reinforces its suitability for scaling up within controlled systems and integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA).

The broader implication of these results lies in Salicornia’s capacity to transform saline habitats into productive agricultural systems. The hydroponic approach tested here surpassed expectations in terms of nutrient and water use efficiency, providing evidence of the plant’s capacity to recycle nutrient-rich effluents and reduce nitrogen and phosphorus accumulation from aquaculture wastewater. This demonstrates a tangible contribution to sustainable biomass valorization and environmental remediation. Therefore, integrating Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods cultivation into circular production frameworks can promote both environmental sustainability and economic viability, maximizing the productive use of saline and marginal areas while minimizing reliance on freshwater and arable land.

The cultivation strategies and treatments applied in this study not only demonstrate pilot-scale feasibility but also present strong potential for scaling into resource-efficient, commercially viable systems. Future work should focus on life-cycle assessments and energy–water–land trade-offs to fully quantify the contribution of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods cultivation to global resource sustainability and the circular bioeconomy.

5. Conclusions

In this study, two cultivation methods were employed: hydroponic and substrate environment cultivation. Both proved to be suitable for Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods development, achieving significant success in plant and biomass production. Additionally, plant response to the biostimulant indicated uniform plant growth and development, with promising reactions across the different maintenance methods, highlighting the most effective approach for preserving the desired compounds. It can be concluded that the methodologies and treatments used in this study are suitable for pilot-scale trials and scaling up for large-scale production.

This study demonstrated the viability of cultivating Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods under controlled hydroponic and substrate environments, highlighting its potential for sustainable food production and biorefinery integration. The methodologies employed—ranging from morphological assessment to advanced analytical techniques such as FTIR-ATR, UV/VIS Spectrophotometry and TLC—provided robust evidence of the plant’s biochemical richness, particularly in terms of pigments and bioactive compounds. These findings open the way for future applications, including the development of functional food products and the integration of this halophyte into green or lignocellulosic biorefinery processes.

Regarding its practical use, Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods can be consumed fresh as a gourmet vegetable, added to salads, seafood dishes, or used as a natural salt substitute due to its mineral content and slightly salty taste. When preserved, it can be pickled, dehydrated, or lyophilized, extending its shelf life while maintaining its nutritional and bioactive properties. Preserved forms allow for its incorporation into processed foods, functional ingredients, or nutraceutical formulations, ensuring year-round availability and minimizing post-harvest degradation losses.

The experimental framework outlined in this work may serve as a basis for pilot-scale trials, with the potential to scale up for industrial applications. Further research is recommended to explore the species’ resilience under variable salinity and environmental conditions, as well as to isolate and valorize specific compounds for use in nutraceutical or pharmaceutical industries. In this way, Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods emerges not only as a resilient crop for saline agriculture, but also as a promising resource for high-value industrial applications, reinforcing its relevance in future strategies addressing climate change, food security, and sustainable resource use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C., J.C., and K.B.; methodology, G.C. and J.C.; software, J.C.; validation, K.B., L.P., and O.F.; formal analysis, G.C. and J.C.; investigation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.; writing—review and editing, K.B., L.P., J.C., and O.F.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, J.C., K.B., L.P., and O.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by national funds through the FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. to the Centre for Functional Ecology—Science for People and the Planet (CFE; UIDB/04004/2020; https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04004/2020), financed by FCT/MCTES through national funds (PIDDAC), Associate Laboratory TERRA (LA/P/0092/2020; https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0092/2020).

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Umimare, Lda, for the Salicornia samples and the hypotheses of experimental working in the company laboratory and nursery. Special thanks to Gonçalo Pereira. Also, special thanks to Sofia Pereira Costa for the supporting working and help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bárrios, S.; Copeland, A. Salicornia perennis. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/192003584/192139092 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Kim, S.; Lee, E.Y.; Hillman, P.F.; Ko, J.; Yang, I.; Nam, S.J. Chemical Structure and Biological Activities of Secondary Metabolites from Salicornia europaea L. Molecules 2021, 26, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, J.R.; Silva, A.M.; Barroca, M.J. Propriedades Antioxidante e Anticancerígena Da Planta Halófita Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods. In Investigação Aplicada no Politécnico de Coimbra: Coletânea de Estudos; Henriques, M., Pereira, C.D., Eds.; Cinep: Coimbra, Portugal, 2020; pp. 81–100. Available online: https://www.ipc.pt/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Coletania3_Investigacao-Aplicada-2020.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Bueno, M.; Del, M.; Cordovilla, P.; Luque, M.M.; Isayenkov, S.; Sini, L.; Hulkko, S.; Rocha, R.M.; Trentin, R.; Fredsgaard, M.; et al. Bioactive Extracts from Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods Biorefinery as a Source of Ingredients for High-Value Industries. Plants 2023, 12, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas-Pérez, S.; Rajabi Dehnavi, A.; Leszczyński, K.; Lubińska-Mielińska, S.; Ludwiczak, A.; Piernik, A. Salicornia europaea L. Functional Traits Indicate Its Optimum Growth. Plants 2022, 11, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzner, M.; Fricke, A.; Schreiner, M.; Baldermann, S. Utilization of Regional Natural Brines for the Indoor Cultivation of Salicornia europaea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Alves, S.C.; Andrade, F.; Sousa, J.; Bento-Silva, A.; Duarte, B.; Caçador, I.; Salazar, M.; Mecha, E.; Serra, A.T.; Bronze, M.R. Soilless Cultivated Halophyte Plants: Volatile, Nutritional, Phytochemical, and Biological Differences. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, O.; Conte, P.; Maria Gonçalves Moreira da Silva, A.; João Barroca, M.; Fadda, C. Use of Response Surface Methodology to Investigate the Effect of Sodium Chloride Substitution with Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods Powder in Common Wheat Dough and Bread. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 99, 105349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamede, M.; Cotas, J.; Bahcevandziev, K.; Pereira, L. Seaweed Polysaccharides in Agriculture: A Next Step towards Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L.; Bahcevandziev, K. Algae Extracts in Horticulture: Characterization of Algae-Based Extracts and Impact on Turnip Germination and Radish Culture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Stojceska, V.; Tassou, S.A. A Systematic Review on the Recent Advances of the Energy Efficiency Improvements in Non-Conventional Food Drying Technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamede, M.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L.; Bahcevandziev, K. Seaweed Polysaccharides as Potential Biostimulants in Turnip Greens Production. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ramírez, P.J.; Pascual-Mathey, L.I.; García-Rodríguez, R.V.; Jiménez, M.; Beristain, C.I.; Sanchez-Medina, A.; Pascual-Pineda, L.A. Effect of Relative Humidity on the Metabolite Profiles, Antioxidant Activity and Sensory Acceptance of Black Garlic Processing. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.Q.; Xu, L.L.; Xue, C.H.; Jiang, X.M. Effect of Stored Humidity and Initial Moisture Content on the Qualities and Mycotoxin Levels of Maize Germ and Its Processing Products. Toxins 2020, 12, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Figueirinha, A.; Pereira, L.; Batista, T. The Effect of Salinity on Fucus ceranoides (Ochrophyta, Phaeophyceae) in the Mondego River (Portugal). J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2019, 37, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, C.; Dupuy, N.; Ta, C.D.; Huvenne, J.P.; Legrand, P. Quantitative analysis of water-soluble vitamins by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Food Chem. 1998, 63, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.F.; Ramadhani, N.N.; Aziz, A.Y.R.; Sahra, M.; Agrabudi, A.I.; Permana, A.D. Development and Validation of UV–Vis Spectrophotometry-Colorimetric Method for the Specific Quantification of Rivastigmine Tartrate from Separable Effervescent Microneedles: Ex Vivo and in Vivo Applications in Complex Biological Matrices. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1303, 137589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J. Fucus ceranoides (Ochrophyta, Phaeophyceae): Bioatividades Dependentes Do Gradiente Salino. Master’s Thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barroca, M.J.; Guiné, R.P.F.; Amado, A.M.; Ressurreição, S.; da Silva, A.M.; Marques, M.P.M.; de Carvalho, L.A.E.B. The Drying Process of Sarcocornia perennis: Impact on Nutritional and Physico-Chemical Properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 4443–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D..; Oktiani, R.; Ragadhita, R. How to Read and Interpret FTIR Spectroscope of Organic Material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 1, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Y.; Sagi, M. Halophyte Crop Cultivation: The Case for Salicornia and Sarcocornia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 92, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D. International Trade in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Actors, Volumes and Commodities. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Katschnig, D.; Broekman, R.; Rozema, J. Salt Tolerance in the Halophyte Salicornia dolichostachya Moss: Growth, Morphology and Physiology. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 92, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Roque, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Ramos, F. Nutrient Value of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods—A Green Extraction Process for Mineral Analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 104, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Castañeda-Loaiza, V.; Salazar, M.; Nunes, C.; Quintas, C.; Gama, F.; Pestana, M.; Correia, P.J.; Santos, T.; Varela, J.; et al. Influence of Cultivation Salinity in the Nutritional Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Microbial Quality of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods Commercially Produced in Soilless Systems. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulkko, L.S.S.; Chaturvedi, T.; Thomsen, M.H. Extraction and Quantification of Chlorophylls, Carotenoids, Phenolic Compounds, and Vitamins from Halophyte Biomasses. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, A.E.M.F.M.; Mohamed, E.; Kasem, A.M.M.A.; El-Ghamery, A.A. Differential Salt Tolerance Strategies in Three Halophytes from the Same Ecological Habitat: Augmentation of Antioxidant Enzymes and Compounds. Plants 2021, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, M.M.; Mendes, C.R.; Doncato, K.B.; Badiale-Furlong, E.; Costa, C.S.B. Growth, Phenolics, Photosynthetic Pigments, and Antioxidant Response of Two New Genotypes of Sea Asparagus (Salicornia neei Lag.) to Salinity under Greenhouse and Field Conditions. Agriculture 2018, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Gavilán, M.; Muñoz-Martínez, M.; Zuasti, E.; Canoura-Baldonado, J.; Mondoñedo, R.; Hachero-Cruzado, I. Yield, Nutrients Uptake and Lipid Profile of the Halophyte Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods Cultivated in Two Different Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture Systems (IMTA). Aquaculture 2024, 583, 740547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.