Abstract

This paper examines the impact of natural resource rents on the economic growth of Tunisia between 1990 and 2023, emphasizing the aspect of resource diversification. The annual time-series data extracted from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators were analyzed using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag model to outline both the short- and long-run dynamics. The results confirm the existence of a long-term relationship between economic growth and oil, natural gas, mineral, and forest rents. Among them, oil and forest rents have strong positive long-term impacts, whereas natural gas and mineral rents contribute relatively moderately due to the structural inefficiencies and absence of value-added activities in these sectors. It was also found that the labor force participation has been affecting growth adversely with continuous impacts, which are driven by skill mismatches, low productivity, and high unemployment, hence indicating structural labor market imbalance that weakens the growth effect of labor. On the other hand, capital formation is still one of the key drivers of long-term growth. The findings highlight the rationale for diversification of the economy, governance reforms, and sustainable management of resources. However, the study suffers from some limitations due to data availability and excluded institutional variables, apart from being narrowed to a single-country case study, which might affect the generalizability of the results. Future works could consider incorporating the indicators of governance, examining nonlinear effects, or expanding the analysis into a multi-country framework.

1. Introduction

Despite the wealth of literature on the resource–growth nexus, there is still a noticeable gap in explicitly considering the disaggregated role that natural resource rents and the degree to which resource diversification contributes to long-run macroeconomic stability among North African countries. Most of the studies rely on aggregated resource measures, which mask sector-specific differences that impede a clear analysis of the impact of oil, gas, mineral, and forest rents on growth in structurally constrained economies. In addition, Tunisia, a moderately resource-rich country, has received scarce empirical attention. Therefore, this paper fills this lacuna with a resource-specific assessment, elaborates an explicit Resource Diversification Index, and derives empirical evidence of how the unique mix of natural resource endowments shapes Tunisia’s economic performance over 1990–2023. These contributions clear up the heterogeneity of resource effects and explain why Tunisia is an analytically meaningful and policy-relevant case.

The link between natural resource rents and economic growth has long been central to debates on development economics, particularly in resource-rich developing countries. Whereas natural resources can stimulate growth through revenue generation, employment, and industrial development, they may also expose economies to vulnerabilities such as price volatility, institutional weakness, and limited diversification. This duality has given way to contrasting narratives of the “resource curse” and “resource blessing,” depending on country-specific governance, economic structures, and diversification capacity.

Tunisia therefore presents a particular case for such an analysis. It is well-endowed with oil, natural gas, minerals, and forest resources that have contributed substantially to the GDP, government revenue, and exports of the country. However, there are a number of inefficiencies, governance challenges, and limited value addition in transforming these resources into more valued products in Tunisia’s extractive industries. The Tunisian economy has equally been susceptible to external shocks, particularly changes in commodity prices and global energy demand.

Tunisia is a relevant case for resource–growth nexus analysis because of its diversified mix of oil, natural gas, minerals, and forest resources, which are combined with structural constraints that limit value addition in the extractive sectors. The economy has also been exposed to external shocks arising from fluctuations in global commodity markets and energy demand. Furthermore, the institutional transformation initiated in 2011 introduced new governance dynamics-increased transparency but also institutional fragility-that contributed to reshaping how natural resources were managed, fiscal policy was conducted, and investment decisions were made. For this reason, the period 1990–2023 is analytically meaningful since it captures both the pre-2011 centralized governance framework and the post-2011 transition toward a more open yet institutionally volatile environment.

Despite the presence of natural resources, progress on resource diversification-defined as the diversification of economic dependence beyond a narrow set of extractive industries-has been slow in the case of Tunisia [1,2]. Diversification is instrumental in reducing vulnerability to sectoral shocks, providing opportunities for industrial linkage development, and finally attaining sustainable long-term growth [3]. Nonetheless, the empirical examination of resource diversification mechanisms with regard to Tunisia’s growth dynamics remains scant, especially within a long-run macroeconomic model framework.

In this context, this study evaluates the relationship of different categories of natural resource rents, such as oil, gas, minerals, and forests, with respect to economic growth in Tunisia, and whether diversification across resources strengthens the long-term growth outcomes. By using the ARDL approach, the study investigates long-term and short-term relationships related to resource rents, capital formation, labor force participation, and GDP. Its three key contributions are as follows. First, this research provides the first resource-specific analysis of rents in Tunisia, avoiding the common aggregation that masks sectoral differences. Second, it provides an empirical linkage between resource diversification mechanisms such as risk dispersion, industrial synergy, and spillover effects on productivity to the growth performance of Tunisia. Third, it presents policy-relevant evidence as to how Tunisia can leverage resource diversification and improved governance to support sustainable development.

Apart from the empirical contribution, this paper provides several elements of novelty, extending beyond conventional ARDL applications in natural resource–growth literature. While most ARDL applications have relied on an aggregated measure of total natural resource rents, this paper uses a fully disaggregated specification-separating oil, natural gas, mineral, and forest rents-to uncover heterogeneous long-run effects that are usually hidden in aggregate analyses. This study innovates by constructing a Resource Diversification Index (RDI) that allows for a systematic investigation into how diversification across resource categories contributes to macroeconomic stability, an aspect not addressed by prior ARDL frameworks for Tunisia or comparable economies. The period spanned in this analysis is unique, ranging between 1990 and 2023, and encompasses both Tunisia’s pre- and post-2011 institutional regimes, thereby allowing the model to incorporate structural and governance shifts absent from previous studies. Combining these features makes the paper a novel contribution that has gone beyond traditional ARDL approaches, with deeper insight into how resource heterogeneity and diversification interact to determine long-term economic growth.

2. Literature Survey

The relationship between natural resource rents and economic growth has been a central theme in economic literature, with extensive theoretical and empirical studies exploring the mechanisms through which natural resource wealth influences economic development. This literature survey is divided into two main sections: a review of theoretical literature and a review of the empirical literature. Theoretical literature provides the foundational frameworks for understanding the resource curse and resource blessing hypotheses, while the empirical literature examines the real-world outcomes of natural resource dependence, with a particular focus on diversification, institutional quality, and governance. This review will also highlight recent studies and their relevance to the Tunisian context, including the countries studied, the periods of estimation, the empirical methodologies used, and the results found.

2.1. Theoretical Literature: The Resource Curse and Resource Blessing

The theoretical discourse on natural resource rents and economic growth is largely framed around the resource curse hypothesis, which posits that countries rich in natural resources tend to experience slower economic growth, higher levels of corruption, and greater political instability compared to resource-scarce countries [4,5]. This hypothesis is rooted in several interconnected mechanisms, including the Dutch disease, rent-seeking behavior, and volatility in commodity prices.

2.1.1. The Dutch Disease

The Dutch disease refers to the phenomenon where a boom in natural resource exports leads to currency appreciation, making other sectors, such as manufacturing and agriculture, less competitive in international markets [6]. This results in a decline in non-resource sectors, reducing economic diversification and making the economy more vulnerable to external shocks. For example, in countries like Nigeria and Venezuela, oil booms have led to the neglect of other sectors, resulting in long-term economic stagnation [7].

2.1.2. Rent-Seeking and Corruption

Natural resource wealth often creates opportunities for rent-seeking behavior, where elites capture resource rents at the expense of broader economic development [7]. This is particularly prevalent in countries with weak institutions, where resource revenues are mismanaged or siphoned off by corrupt officials. Auty [5] argues that rent-seeking behavior not only undermines economic growth but also exacerbates inequality and social unrest.

2.1.3. Volatility in Commodity Prices

Natural resource-dependent economies are highly susceptible to fluctuations in global commodity prices, which can lead to macroeconomic instability. For instance, a sudden drop in oil prices can result in budget deficits, reduced public spending, and economic recessions [3]. This volatility makes long-term economic planning difficult and discourages investment in other sectors.

2.1.4. The Resource Blessing Hypothesis

While the resource curse hypothesis has dominated literature, some scholars argue that natural resources can be a blessing rather than a curse, provided that countries have strong institutions and effective governance [8]. According to this view, natural resource wealth can fuel economic growth by providing the financial resources needed for infrastructure development, education, and healthcare. For example, Norway has successfully managed its oil wealth by investing in a sovereign wealth fund and diversifying its economy into sectors such as technology and fisheries [9].

2.1.5. The Role of Institutions

The quality of institutions plays a critical role in determining whether natural resources become a curse or a blessing. Mehlum [8] argue that in countries with strong institutions, natural resource wealth is more likely to be used productively, fostering economic growth and development. Conversely, in countries with weak institutions, resource wealth often leads to corruption, inequality, and economic stagnation. This highlights the importance of governance and institutional quality in managing natural resource rents.

2.2. Empirical Literature: Natural Resource Rents and Economic Growth

The empirical literature on natural resource rents and economic growth has produced mixed results, reflecting the complexity of this relationship. While some studies have found evidence of a resource curse, others have shown that natural resources can have a positive impact on economic growth, particularly when combined with sound economic policies and strong institutions.

2.2.1. Evidence of the Resource Curse

Several empirical studies have found a negative correlation between resource dependence and economic growth, particularly in countries with weak institutions. For example, Collier and Hoeffler [10] found that resource-rich countries are more prone to civil conflict, which undermines economic growth. Similarly, Bulte et al. [11] Bulte found that resource abundance is associated with lower levels of human capital accumulation, which is a key driver of long-term economic growth. In the case of Tunisia, Ben Slimane and Ben Hassine [12] found that the country’s reliance on oil and phosphate exports has exposed its economy to external shocks, such as fluctuations in global commodity prices, leading to economic instability.

2.2.2. Evidence of the Resource Blessing

On the other hand, some studies have found that natural resources can have a positive impact on economic growth, particularly in countries with strong institutions and effective governance. Lederman and Maloney [13] found that natural resource abundance is positively associated with economic growth in countries with good governance. Similarly, Brunnschweiler and Bulte [14] argue that the resource curse is not a universal phenomenon and that the negative effects of resource dependence can be mitigated through appropriate policy interventions. For example, Botswana has successfully used its diamond revenues to invest in education, healthcare, and infrastructure, leading to sustained economic growth [15].

2.2.3. The Role of Economic Diversification

Economic diversification is widely regarded as a key strategy for mitigating the resource curse. By reducing dependence on volatile commodity markets, diversification creates a more resilient economic structure [1]. In the context of natural resources, diversification can take several forms, including the development of downstream industries, investment in renewable resources, and the promotion of sectors such as manufacturing and services. For example, Malaysia has successfully diversified its economy by developing its manufacturing and technology sectors, reducing its dependence on oil and gas exports [2]. In Tunisia, efforts to diversify the economy have been a key policy objective, particularly in the post-revolution period. The country has sought to develop sectors such as tourism, agriculture, and renewable energy, but progress has been hindered by challenges such as political instability, bureaucratic inefficiency, and limited access to finance [16]. These challenges highlight the importance of institutional quality and governance in determining the outcomes of diversification strategies.

2.2.4. Mechanisms Through Which Resource Diversification Affects Economic Growth

Resource diversification affects economic growth through two key mechanisms reported in literature:

- Risk Dispersion and Macroeconomic Stability

A highly resource-concentrated base makes countries especially vulnerable to external shocksin the form of price and demand fluctuations, among geopolitical risks [3]. Resources spread across extraction industries such as oil, gas, minerals, and renewable resources lower the volatility of revenue, increase stability at a macroeconomic level, and help to budget public spending with better predictability [1]. This risk-dispersion mechanism is very important for Tunisia considering its high vulnerability to external shocks and narrow dependence on few export commodities.

- Industrial Synergy and Productivity Spillovers

Diversification encourages forward and backward linkages between the resource sectors and other industries, especially manufacturing, services, logistics, and energy technologies. These linkages increase value addition, promote innovation, and raise resource efficiency. For instance, developing downstream industries in the processing of gas or refining minerals enhances job opportunities and technological upgrading. This is the industrial-synergy mechanism that provides a theoretical underpinning to the role of resource diversification in long-run growth.

2.2.5. The Role of Governance and Institutional Quality

The role of governance and institutional quality in determining the impact of natural resources on economic growth has been a major focus of recent empirical studies. Strong institutions are essential for ensuring that resource revenues are managed transparently and used to promote broad-based economic development [8]. In countries with weak institutions, resource wealth often leads to rent-seeking behavior, corruption, and inequality, which undermine economic growth [7]. For example, in many oil-rich countries in the Middle East and Africa, resource revenues have been captured by elites, leading to widespread poverty and social unrest [10]. In Tunisia, the post-revolution period has seen increased attention to governance and transparency in the management of natural resource revenues. However, challenges remain, particularly in terms of bureaucratic inefficiency and corruption [12]. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for ensuring that natural resource wealth contributes to sustainable economic growth in Tunisia.

2.2.6. Recent Empirical Studies

Recent empirical studies have further explored the relationship between natural resource rents and economic growth, with a focus on the role of technological innovation, human capital, and environmental sustainability. For example, Badeeb et al. [17] found that technological innovation can mitigate the negative effects of resource dependence by promoting economic diversification and improving productivity. Similarly, Al Mamun et al. [18] found that investment in human capital is essential for ensuring that natural resource wealth contributes to long-term economic growth. In the context of environmental sustainability, Ahmed et al. [19] argues that the exploitation of natural resources must be balanced with efforts to protect the environment and promote renewable energy. Bakari [20] investigated the effects of natural resources, CO2 emissions, energy use, domestic investment, innovation, trade, and digitalization on economic growth across 52 African countries from 1996 to 2021. Using random effect models, fixed effect models, and the Hausman test, the study found that domestic investment, exports, natural resources, and final consumption expenditure positively impacted economic growth, while labor force, imports, and energy use had a negative effect. Interestingly, CO2 emissions, innovation, and internet use were found to have no significant impact on economic growth. The study recommended policies to enhance domestic investment and trade while managing energy consumption and digitalization to maximize their economic contributions. Bakari [21] extended this analysis to 17 East Asia-Pacific countries from 2004 to 2023, using descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, the Static Gravity Model, Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), and Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS). The results confirmed that capital, labor, financial development, and trade openness were key drivers of economic growth, while digitalization and natural resources had limited or non-significant impacts. These findings suggest that despite technological advancements, digitalization has yet to play a major role in economic growth in the East Asia-Pacific region.

Singh et al. [22] examined the impact of natural resource rent on economic growth in P5+1 countries (US, UK, France, China, Russia, and Germany) using quantile-on-quantile regression and a cross-sectional autoregressive distributed lag (CS-ARDL) approach. Their findings revealed a negative relationship between natural resources and economic growth in the panel, except for China and the US, where a positive effect was observed. The study emphasized the need for investments in renewable energy and technological innovations to mitigate the adverse effects of natural resource dependence. Zhang et al. [23] focused on Pakistan from 1985 to 2018 using a dynamic autoregressive distributed lag (DARDL) approach. Their findings indicated that while natural resources negatively influenced carbon emissions in the long run, economic growth contributed positively to emissions. The study confirmed the presence of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), suggesting that economic growth initially degrades the environment but improves it after reaching a certain threshold. Haseeb et al. [24] examined the natural resource curse hypothesis in five Asian economies from 1970 to 2018 using quantile-on-quantile regression. Their results confirmed that natural resources positively impacted economic growth in all countries except India, where the effect was negative. The study recommended better resource management strategies to optimize economic benefits.

Arslan et al. [25] explored the trade-offs between natural resources, environmental sustainability, and economic growth in China from 1970 to 2016. Their findings suggested that while natural resources improved environmental sustainability, they came at the cost of economic growth. Conversely, financial development and trade exacerbated environmental degradation, indicating a need for governance mechanisms to balance these effects. Lee and He [26] investigated the resource curse hypothesis in China from 2008 to 2018 using a finite mixture model. Their study identified two distinct growth paths: one where natural resource hindered green economic growth (resource curse) and another where they contributed positively (resource blessing). Market-oriented institutions played a crucial role in determining the direction of this relationship. Rahim et al. [27] analyzed the Next Eleven countries from 1990 to 2019, utilizing econometric models addressing cross-sectional dependence. Their results supported the resource curse hypothesis, as natural resource rents negatively impacted economic growth. However, human capital development mitigated this effect, highlighting the importance of investing in education and skills development. Tabash et al. [28] examined 24 African economies from 1995 to 2017 using the system GMM model. Their findings indicated that natural resource rents negatively affected economic growth, whereas economic complexity had a positive impact. However, when natural resources interacted with economic complexity, the effect on growth became positive, suggesting that higher economic complexity can transform resource wealth into a growth driver. Xie et al. [29] explored the nonlinear relationship between natural resources and economic growth in 57 developing countries from 2008 to 2019 using the System GMM model. Their study found an inverse-U-shaped relationship, where resource availability initially boosted growth but later hindered it beyond a threshold. The research emphasized the role of frontier technologies, such as artificial intelligence and renewable energy, in enhancing the positive effects of natural resources on economic growth. Xiaoman et al. [30] focused on the MENA region from 1980 to 2018 using second-generation panel cointegration techniques. Their results indicated that natural resource abundance improved environmental quality, while trade openness and urbanization negatively impacted it. The study provided policy recommendations emphasizing the role of economic globalization in sustainable development.

The theoretical and empirical literature on natural resource rents and economic growth highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of this relationship. While natural resources have the potential to drive economic development, their impact is heavily influenced by factors such as institutional quality, governance, and economic diversification. In the case of Tunisia, the country’s experience with natural resource rents underscores the importance of diversification and good governance in maximizing the benefits of resource wealth. By examining the impact of natural resource diversification on economic growth in Tunisia, this study aims to contribute to the broader academic discourse on the resource curse and provide valuable insights for policymakers seeking to promote sustainable development in resource-dependent economies.

3. Empirical Methodology

The empirical methodology section provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing the relationship between natural resource rents and economic growth. By employing the ARDL model, this study effectively captures long-run dynamics, ensuring robust estimation in the presence of mixed integration orders of variables. Furthermore, the methodology incorporates essential diagnostic tests to validate model reliability, addressing concerns related to serial correlation, heteroskedasticity, and parameter stability.

3.1. Theoretical Framework

In conventional growth theory, the essential determinants of output in the Cobb–Douglas production function are capital and labor. It has been argued, however, that in natural resource-based economies, natural resources represent an indispensable input in the creation of output level and productivity [3,4]. While a number of empirical and theoretical works include natural resource rents in the standard production function either as an input of production or as an indicator of resource-based revenues that fund capital accumulation and technological improvement, it is recognized that, in developing countries, an excessive dependence on natural resources generally suppresses economic development [13,14].

Natural resource rents, such as those from oil, gas, minerals, and forests, are therefore a factor of production and also part of the national income of Tunisia. Such rents affect economic growth through the following:

- Their contribution to extraction-based industries.

- Their role in financing public investment and infrastructure.

- Their impact on national savings, energy supply, and export revenues.

Thus, taking into consideration the literature on resource-dependent economies such as [6,7,8], we adopt an augmented Cobb–Douglas production function that embeds natural resource rents (NRR) as a further production input:

where Excellence is reached as the reflectivity can be controlled without changing the conductivity of the material. refers to disaggregated natural resource rents: oil, gas, minerals, forests. The inclusion of these rents is theoretically justified because they have a direct effect on production capacity, foreign exchange availability, and government investment—three important channels for long-term growth in developing economies. This theoretical basis is the foundation for the empirical ARDL model.

3.2. Estimation Strategy

Given the mixed order of integration among variables (stationary at level or first difference), the study employs the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) bounds testing approach to co-integration developed by [31]. The ARDL model is particularly well-suited as it allows estimation in the presence of both and variables while preserving the efficiency of short- and long-run relationship estimation. The ARDL model takes the following form:

The Solow–Swan and Cobb–Douglas growth frameworks suggest that formation of capital and labor force participation are two key factors in determining economic output and, as such, the former two variables must be used as a priori baseline controls. These two variables have been employed universally as basic production factors throughout the analysis of macro-growth studies and form the bare minimum factor required to retain theoretical consistency.

While other variables such as institutional quality, trade openness, financial development, and globalization are indeed relevant for growth, in this study they were intentionally not included for the following three methodological reasons:

- (1)

- Avoiding Over-parameterization in a Small Sample

In fact, ARDL models necessitate parsimonious specifications, particularly when the sample one uses covers only 1990–2023, hence 34 observations. Controls should not be too many, because they will reduce the degree of freedom, weaken statistical power, and make estimates unstable.

- (2)

- Multicollinearity avoidance

Institutional quality, openness, and governance indicators are often highly correlated with natural resource rents and income levels [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Their inclusion risks masking the true long-run contribution of resource rents.

- (3)

- Focus on the Core Research Question

The main goal of the study is to estimate the distinct effect of each category of natural resource rents on the economy’s growth, rather than to build a broad growth model.

Including only capital and labour allows the model to isolate how oil, gas, mineral, and forest rents influence growth while maintaining the structure consistent with theoretical production functions.

- (4)

- Implicit Capture of Institutional and Openness EffectsInstitutional quality and openness have the following indirect impacts:

- Investment (capital formation);

- Labor market outcomes;

- Efficiency in resource management.

Thus, their influence is partially captured through the included variables. The estimation approach follows earlier resource–growth studies using similar parsimonious specifications [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Before estimating the ARDL model, unit root tests are conducted using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP) tests to determine the integration order of the variables. The results confirm that the variables exhibit mixed stationarity properties, justifying the use of the ARDL approach.

The bounds test for cointegration is applied to examine the existence of a long-run relationship among variables. The null hypothesis (no long-run relationship) is tested against the alternative , where at least one . If the computed F-statistic exceeds the upper critical bound, we reject in favor of cointegration.

Once cointegration is established, the ARDL model estimates both long-run coefficients and short-run dynamics via an Error Correction Model (ECM), which is specified as:

where is the error correction term, capturing the speed of adjustment towards long-run equilibrium. A significant and negative confirms the presence of cointegration, with its magnitude indicating the speed at which deviations from long-run equilibrium are corrected.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the estimated ARDL model, a series of diagnostic tests are conducted, evaluating key econometric properties such as serial correlation, heteroskedasticity, and model stability. These tests are crucial in confirming that the model is correctly specified and that its estimated coefficients can be interpreted with confidence.

The presence of serial correlation in the residuals can lead to inefficiency in the estimators, potentially biasing the standard errors and rendering hypothesis tests invalid. To detect serial correlation, we employ the Breusch-Godfrey LM test, which examines whether the error terms exhibit autocorrelation up to a specified lag order. The null hypothesis of the test states that there is no serial correlation in the residuals:

where represents the autocorrelation coefficients at different lag levels. If the test statistic does not exceed the critical value, we fail to reject the null hypothesis, confirming that the residuals are independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.), thereby validating the efficiency of the model estimates.

Heteroskedasticity occurs when the variance of the error term is not constant across observations, which can lead to inefficient estimators and unreliable statistical inference. To examine this property, we apply both the Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test and the ARCH test. The Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test evaluates whether the variance of residuals is dependent on the explanatory variables, with the null hypothesis given by

where represents the conditional variance of residuals. A failure to reject the null hypothesis indicates homoskedasticity, confirming that the residuals maintain constant variance over time. Additionally, the ARCH test is employed to detect autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity, where the variance of residuals depends on past squared residuals. The null hypothesis assumes no ARCH effects:

where represents the coefficients of past squared residuals. If the test fails to reject the null hypothesis, this suggests that the variance of residuals does not exhibit time-dependent fluctuations, further strengthening the robustness of the estimated model.

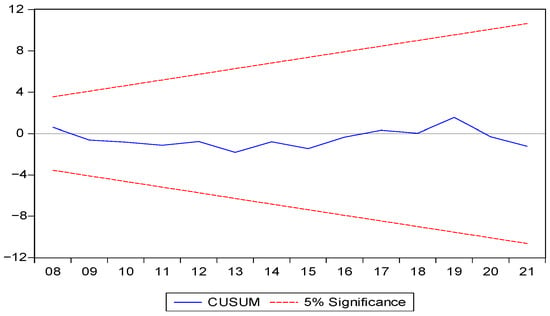

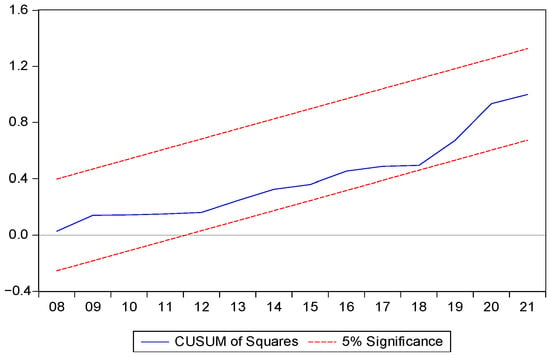

To assess the stability of the model parameters over time, the CUSUM (Cumulative Sum) and CUSUM-SQ (CUSUM of Squares) tests are applied. These tests evaluate whether the estimated coefficients remain stable throughout the sample period. The CUSUM test is based on the recursive sum of recursive residuals, with the null hypothesis stated as

where represents the estimated coefficients at time . If the cumulative sum remains within the 5% significance boundaries, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, indicating coefficient stability.

Similarly, the CUSUM-SQ test extends this analysis by considering squared recursive residuals, providing additional confirmation of model stability. If the CUSUM-SQ statistics remain within the critical bounds, we conclude that there are no structural breaks in the estimated relationships.

The results of the diagnostic tests indicate that the estimated ARDL model satisfies key econometric assumptions. The Breusch-Godfrey test confirms the absence of serial correlation, ensuring the efficiency of the model’s parameter estimates. The heteroskedasticity tests (Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey and ARCH) reveal that the residuals exhibit homoskedasticity, further supporting the reliability of the statistical inferences drawn. Lastly, the CUSUM and CUSUM-SQ tests affirm the stability of the estimated coefficients over time, demonstrating the robustness of the model in explaining the dynamics of economic growth and natural resource rents in Tunisia. The ARDL model provides a robust framework for analyzing the impact of natural resource rents on economic growth in Tunisia. By distinguishing between long-run effects and incorporating diverse natural resource categories, the empirical methodology ensures comprehensive insights into the sustainability of Tunisia’s resource-dependent growth model. The findings of this methodology will be instrumental in providing policymakers with targeted strategies to mitigate the negative consequences of resource dependence and promote economic diversification.

3.3. Resource Diversification Index—RDI

Using a Herfindahl-Hirschman-type measure, we constructed for Tunisia a Resource Diversification Index (RDI) to capture the overall degree of natural resource diversification. The index is defined as follows:

where denotes the share of each natural resource rent i (oil, gas, minerals, and forests) in total natural resource rents at time t.

The RDI ranges from 0 to 1, where

RDI → 0 indicates strong concentration (dependence on one dominant resource),

RDI → 1 reflects strong diversification, or said otherwise, a balanced distribution across resources.

This index allows us to examine the comprehensive effect of resource diversification on economic growth, complementing the analysis based on the four individual natural resource categories.

4. Empirical Results

This section presents the empirical findings of the study, including stationarity tests, cointegration analysis, and long-term modeling results. These analyses provide insights into the dynamic relationships between economic growth, capital, labor, and natural resource rents in Tunisia, helping to understand the impact of these variables on sustainable development.

4.1. Interpretation of Stationarity Test Results

To ensure the robustness of the empirical analysis, it is imperative to assess the stationarity properties of the time series variables used in the model. The presence of unit roots in time series data can lead to spurious regression results, making it necessary to determine whether the variables are stationary at level or require differencing to achieve stationarity. Table 1 presents the results of the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) tests, both of which assess the null hypothesis that a given series has a unit root, implying non-stationarity.

Table 1.

Results of the ADF and PP stationarity tests.

At the level form, the test statistics for most variables fail to reject the null hypothesis of non-stationarity at conventional significance levels. In the case of the PP test with a constant (C), only the logarithm of GDP ‘Log(Y)’ and labor ‘Log(L)’ show evidence of stationarity at the 5% and 1% significance levels, respectively, with t-statistics of −3.0765 and −5.0324. However, all other variables, including capital ‘Log(K)’, natural gas rents ‘Log(NGR)’, mineral rents ‘Log(MR)’, oil rents ‘Log(OR)’, and forest rents ‘Log(FR)’, exhibit t-statistics that do not exceed the critical values, indicating the presence of unit roots. When a constant and trend (CT) are included in the PP test, none of the variables exhibit stationarity, as all t-statistics remain above the critical values. This suggests that the time series properties of these variables contain deterministic trends or stochastic trends that require differencing to attain stationarity. The ADF test results at level largely align with those of the PP test. With a constant included, GDP ‘Log(Y)’ and labor ‘Log(L)’ show some degree of stationarity, but the remaining variables retain their unit roots. When a constant and trend are added, all variables exhibit test statistics that fail to reject the null hypothesis, reinforcing the need for differencing.

To address the issue of non-stationarity, we apply the ADF and PP tests to the first-differenced series. The results demonstrate that after taking first differences, all variables become stationary at conventional significance levels. Specifically, under the PP test with a constant (C), GDP ‘Log(Y)’, capital ‘Log(K)’, natural gas rents ‘Log(NGR)’, mineral rents ‘Log(MR)’, oil rents ‘Log(OR)’, and forest rents ‘Log(FR)’ all exhibit t-statistics exceeding the 1% or 5% critical values, confirming their stationarity. Under the PP test with a constant and trend (CT), the results remain consistent, further validating that the variables no longer contain unit roots after first differencing. The same pattern is observed for the ADF test, where all variables become stationary at first difference under both constant-only and constant-and-trend specifications.

The mixed stationarity results, where some variables are ‘I(0)’ (stationary at level) and others are ‘I(1)’ (stationary at first difference), justify the application of the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model. The ARDL bounds testing approach, developed by [31], is particularly well-suited for analyzing relationships in the presence of a mixture of stationary and non-stationary variables. The fact that none of the variables are integrated at ‘I(2)’ (stationary only after second differencing) is crucial because the ARDL method requires that all variables be either ‘I(0)’ or ‘I(1)’. If any variable were ‘I(2)’, the computed F-statistics for the bounds test would become invalid, making co-integration analysis inappropriate. Given these findings, we proceed with the ARDL estimation, incorporating both level and differenced variables as needed. This approach allows for the examination of both short-run and long-run relationships between economic growth, capital formation, labor, and natural resource rents in Tunisia. The confirmation of stationarity after first differencing ensures the reliability of the estimated results and prevents the possibility of spurious regressions.

4.2. Cointegration Test Results

To assess the presence of a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables under study, the ARDL bounds testing approach is employed. This method, developed by [31], is particularly suitable for models where variables exhibit a mixture of stationarity at levels ‘I(0)’ and first differences ‘I(1)’. The bounds test evaluates whether a meaningful long-run association exists among economic growth, capital, labor, and natural resource rents by testing the null hypothesis of no cointegration.

The bounds test is based on computing an F-statistic, which is then compared against two sets of critical values:

- ✓

- The I(0) bound, which assumes that all variables are stationary at level.

- ✓

- The I(1) bound, which assumes that all variables are stationary at first difference.

The decision criteria are as follows:

- ✓

- If the computed F-statistic is below the lower bound I(0), we fail to reject the null hypothesis, indicating no cointegration.

- ✓

- If the F-statistic is above the upper bound I(1), the null hypothesis is rejected, confirming the presence of a long-run relationship.

- ✓

- If the F-statistic falls between the two bounds, the result is inconclusive, requiring further confirmation through additional tests such as the error correction model (ECM).

Table 2 presents the results of the ARDL bounds test, where the computed F-statistic is 4.999 with k = 6 explanatory variables. When comparing this value to the critical value bounds at various significance levels, the following results are observed: at the 10% significance level, the lower and upper bounds are 2.12 and 3.23, respectively; at the 5% significance level, the bounds are 2.45 and 3.61; at the 2.5% significance level, the bounds are 2.75 and 3.99; and at the 1% significance level, the bounds are 3.15 and 4.43. Since the computed F-statistic (4.999) exceeds the upper bound (I1) at all significance levels, we can confidently reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration at the 1% significance level. This result strongly supports the existence of a stable long-run relationship between economic growth, capital accumulation, labor force participation, and natural resource rents in Tunisia.

Table 2.

Results of the Bounds Test cointegration test.

The confirmation of a long-run relationship carries important implications for economic policy and empirical modeling. It suggests that any short-term deviations from equilibrium will eventually self-correct, guiding the economy back to its long-term trajectory. This finding justifies the inclusion of an error correction term (ECT) in the subsequent estimation of the short-run dynamics. Additionally, the presence of cointegration ensures that the long-run coefficients estimated are meaningful and not the result of spurious correlations. Following this outcome, the study proceeds with the estimation of the ARDL long-run model and the corresponding short-run error correction model (ECM) to analyze the speed of adjustment to equilibrium. The results confirm that natural resource rents, capital, and labor collectively influence Tunisia’s long-term economic growth trajectory.

The results of the ARDL bounds test provide robust evidence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between the key economic variables. The rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration at the 1% significance level emphasizes the interconnections between economic growth, capital investment, labor market dynamics, and resource rents. This finding supports the continuation of the ARDL estimation to quantify both the long-term and short-term effects of these variables on GDP growth. Furthermore, the presence of cointegration highlights the need for policies that ensure long-term stability in resource revenue management and productive investments.

4.3. Long-Term ARDL Model Estimation Results

Table 3 presents the results of the long-term estimation of the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model, with the logarithmic first difference in economic growth (Log(Y)) as the dependent variable. The ARDL approach is well-suited for analyzing long-term relationships because it accounts for dynamic adjustments over time, estimating both short-term and long-term effects. The estimated long-term coefficients reflect the lasting impact of key macroeconomic variables—such as capital, labor, and various natural resource rents—on Tunisia’s overall economic growth trajectory.

Table 3.

Long-run ARDL Estimated Coefficients.

The coefficient of capital formation (Log(K)) is 0.146437, statistically significant at the 1% level (p-value = 0.0007). This suggests that, in the long run, a 1% increase in gross fixed capital formation leads to a 0.146% increase in economic growth. This finding aligns with classical economic theories, particularly the Solow-Swan growth model, which emphasizes the critical role of capital accumulation in driving long-term economic expansion. The strong significance of capital underscores the importance of continued investment in infrastructure, machinery, and technology to boost Tunisia’s productive capacity.

In contrast, the coefficient for labor (Log(L)) is negative, measuring −0.116194, and is statistically significant at the 5% level (p-value = 0.0150). This suggests that, in the long run, a 1% increase in the labor force corresponds to a 0.116% decrease in GDP growth. This seemingly counter-intuitive result points to structural inefficiencies within the labor market, such as skill mismatches, low productivity, or underemployment. The negative effect of labor highlights the need for comprehensive labor market reforms that address these inefficiencies. Key policy measures should include improving education, offering vocational training, and creating employment opportunities to enhance labor’s contribution to economic growth.

The coefficient for forest rents (Log(FR)) is 0.075847 and is statistically significant at the 5% level (p-value = 0.0497). This indicates that, in the long run, a 1% increase in forest rents contributes to a 0.075% increase in economic growth. These results suggest that revenues derived from sustainable forest resource management can positively support economic development. Therefore, policymakers should emphasize sustainable forestry practices to ensure that resource exploitation does not compromise environmental stability, while still benefiting economic growth.

The estimation results showed that natural gas rents and mineral rents are statistically insignificant in the long run, which implies that these sectors are unable to produce stable or strong growth effects under the prevailing structural and institutional conditions.

The coefficient for oil rents (Log (OR)) is 0.031137, with a p-value of 0.0340, making it statistically significant at the 5% level. This suggests that in the long run, a 1% increase in oil rents leads to a 0.031% increase in GDP growth. Given that oil has historically played a central role in Tunisia’s economy, this result reaffirms its ongoing importance as a driver of long-term economic expansion. However, in light of global shifts toward renewable energy and concerns over fossil fuel dependency, Tunisia must adopt policies that foster economic diversification, reducing its reliance on oil revenues.

The error correction term (ECT) is highly significant at the 1% level (p-value = 0.0000), with a coefficient of −1.106102. This negative and significant coefficient confirms the existence of a stable long-run relationship among the variables. The magnitude of the coefficient suggests that deviations from long-term equilibrium are corrected at a rapid speed of approximately 110.6% per year. This rapid adjustment indicates that any short-term disruptions to Tunisia’s economic growth path are corrected within a year, reinforcing the stability of the estimated long-run relationship. The high speed of adjustment also reflects Tunisia’s economic resilience to external shocks, but it underscores the necessity of maintaining effective economic policies to sustain this stability.

4.4. Short-Run Dynamics and Error Correction Term (ECM)

The short-run coefficients from the ECM reveal the immediate effects of changes in natural resource rents on economic growth. From this, it can be seen that oil rents and forest rents have statistically significant short-run effects, meaning that changes in these sectors are quickly transmitted to GDP.

Capital formation has a positive and significant short-run effect, while labor force participation demonstrates a negative short-run impact-as would be expected, given the existing structural conditions in the Tunisian labor market.

The error-correction term is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, which confirms the existence of a stable long-run relationship among the variables. The estimated coefficient (ECT = −1.1061) indicates that about −1.11% of the deviations from long-run equilibrium are corrected annually. This means the Tunisian economy adjusts at a moderate speed toward long-run equilibrium after a short-run shock in natural resource rents or other macroeconomic variables.

4.5. Policy Implications for Long-Term Growth

The long-term ARDL model estimation results provide several important policy insights. First, the strong positive role of capital investment highlights the need for policies that encourage both public and private investments in productive sectors. Expanding access to finance, improving infrastructure, and fostering technological innovation will be essential for sustaining long-term economic growth. Second, the negative impact of labor emphasizes the need to address structural inefficiencies in the labor market. Policymakers should focus on improving workforce skills, aligning education with market demands, and creating job opportunities that enhance labor productivity and economic contributions.

Third, the significant role of natural resource rents, particularly from oil and forests, indicates the importance of implementing sustainable resource management policies. Strengthening governance, ensuring transparency in revenue allocation, and investing in renewable energy sources will be crucial for mitigating risks associated with resource dependency and ensuring long-term economic stability. Finally, the rapid speed of adjustment, as indicated by the error correction term, suggests that Tunisia’s economy is highly responsive to policy changes. To maintain stability, the government must adopt proactive fiscal and monetary policies that mitigate external shocks while fostering sustainable growth.

The results from Table 3 affirm the presence of significant long-term relationships between economic growth, capital, labor, and natural resource rents in Tunisia. While capital investment remains a key driver of economic expansion, the negative impact of labor points to inefficiencies that require urgent policy intervention. The role of natural resource rents varies across categories, with oil and forest rents having a substantial effect on GDP growth. The highly significant negative error correction term confirms the model’s stability, suggesting that deviations from long-run equilibrium are quickly corrected. Moving forward, targeted economic policies focused on investment, labor market efficiency, and sustainable resource management will be essential for ensuring Tunisia’s long-term economic prosperity.

4.6. Diagnostic Test Results

To ensure the reliability and robustness of the estimated ARDL model, several diagnostic tests were conducted. These tests assessed important econometric assumptions, such as heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and model specification, which are essential for validating the unbiasedness and efficiency of the model’s estimates. The results, as presented in Table 4, offer critical insights into the model’s performance and help verify that the estimated coefficients can be relied upon for economic policy analysis.

Table 4.

Results of the diagnostic tests.

One of the key assumptions in regression models is that the variance of the residuals remains constant across observations—this is known as homoskedasticity. If heteroskedasticity exists, it could lead to inefficient and biased estimates. To check for heteroskedasticity, four different tests were applied: the Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test, the Harvey test, the Glejser test, and the ARCH test.

The Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test produced an F-statistic of 0.584170 with a p-value of 0.8430, suggesting that the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity cannot be rejected. Furthermore, the ObsR-squared statistic of 17.21342 with a p-value of 0.6391 adds further support to this conclusion. Similarly, the Harvey test provided an F-statistic of 0.542138 and a p-value of 0.8726, which also indicates the absence of heteroskedasticity. The ObsR-squared value of 16.68758 with a p-value of 0.6732 corroborates this finding. Likewise, the Glejser test and the ARCH test produced results that further confirm the homoskedasticity assumption. The F-statistic of 0.637456 in the Glejser test and the F-statistic of 0.000337 in the ARCH test, both with high p-values, indicate that there is no evidence of heteroskedasticity or autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Taken together, these tests consistently show that the residuals do not exhibit heteroskedasticity, which assures that the model’s estimated coefficients remain efficient and unbiased.

Serial correlation, or autocorrelation, refers to the correlation of residuals across time periods, which can result in inefficient estimators and invalid inferences. To detect any serial correlation, the Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM test was employed. The results revealed an F-statistic of 0.394878 with a p-value of 0.6822, meaning that the null hypothesis of no serial correlation could not be rejected. The Obs-R-squared statistic of 1.790722 and its p-value of 0.4085 also support this finding. This confirms that the residuals from one period are not correlated with those from previous periods, implying that the model does not suffer from autocorrelation problems. As a result, the model’s standard errors are reliable, ensuring that hypothesis testing is sound. The results of these diagnostic tests provide a reassuring validation of the ARDL model. The absence of heteroskedasticity confirms that the model’s estimated coefficients are both efficient and unbiased. The lack of serial correlation in the residuals strengthens the reliability of the standard errors, ensuring that the statistical inference drawn from the model is sound. Additionally, the lack of ARCH effects assures that volatility clustering, which can affect time series models, is not a concern here. Overall, these findings suggest that the ARDL model is well-specified and free from any major econometric issues.

Given the consistency of these results, we can confidently conclude that the ARDL model provides robust and reliable estimates of the long-run and short-run relationships between economic growth, capital accumulation, labor force participation, and natural resource rents. The model’s robustness increases the validity of the empirical results, making them highly suitable for informing economic policy decisions.

The diagnostic test results presented in Table 4 validate the robustness of the ARDL model, confirming that it adheres to key econometric assumptions. The tests for heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity all point to a well-specified model that can provide reliable insights into the relationships between key economic variables in Tunisia. These findings enhance confidence in the model’s ability to accurately capture the dynamics of Tunisia’s economic growth, offering valuable guidance for policymakers seeking to design effective economic strategies. The model’s reliability is critical for ensuring that policy decisions are based on sound and empirical economic evidence.

4.7. Stability Test Results: CUSUM and CUSUM Square Tests

Assessing the stability of the estimated model parameters over time is a critical step in validating the reliability and consistency of the ARDL model. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the results of the CUSUM (Cumulative Sum) test and the CUSUM of Squares (CUSUM-SQ) test, respectively. These tests are widely used in econometric analysis to detect potential structural changes in the model and ensure that the estimated coefficients remain stable over the sample period.

Figure 1.

Result of the CUSUM test.

Figure 2.

Result of the CUSUM Square test.

The CUSUM test is designed to assess the stability of the estimated parameters by tracking cumulative sums of recursive residuals over time. The test plots the cumulative sum against critical boundaries at a 5% significance level. If the plot remains within these boundaries, the null hypothesis of parameter stability cannot be rejected, confirming that the estimated coefficients do not exhibit significant shifts over time.

As shown in Figure 1, the CUSUM test results indicate that the cumulative sum remains within the 5% critical bounds throughout the entire observation period. This implies that there are no significant parameter instabilities or structural shifts affecting the model. The stability of the coefficients suggests that the estimated relationships between economic growth, capital, labor, and natural resource rents remain valid and consistent over time. This finding reinforces the reliability of the long-term and short-term ARDL model estimates, ensuring that the derived policy implications are based on stable economic relationships.

While the CUSUM test assesses the stability of model parameters in terms of mean shifts, the CUSUM of Squares (CUSUM-SQ) test evaluates the variance stability of the residuals over time. This test is particularly useful in detecting abrupt structural breaks or changes in the volatility of the estimated relationships. If the plotted CUSUM-SQ line remains within the 5% significance boundaries, it confirms that the variance of the residuals is stable and that the model does not experience structural instability.

As depicted in Figure 2, the results of the CUSUM-SQ test also indicate that the plotted statistic remains well within the critical boundaries. This finding provides strong evidence against the presence of structural breaks or changes in the variance of residuals. The absence of significant fluctuations in the squared residuals further strengthens the argument that the ARDL model is correctly specified and that its estimates are robust over time.

The results of both the CUSUM and CUSUM-SQ tests provide compelling evidence that the estimated model is statistically stable and structurally sound over the sample period. The fact that both test plots remain within the 5% significance bounds confirms that the estimated coefficients do not experience sudden shifts or unexpected variations. This is particularly important in economic modeling, as unstable parameter estimates can lead to misleading conclusions and unreliable policy recommendations.

The stability of the model implies that the estimated long-run and short-run relationships between economic growth and its determinants are consistent and reliable over time. This ensures that the insights derived from the ARDL model are valid and applicable to economic policy formulation. Policymakers can thus rely on these results when designing long-term strategies for investment, labor market reforms, and resource management, knowing that the underlying economic relationships have remained stable historically.

Moreover, the absence of structural breaks in the variance of residuals, as indicated by the CUSUM-SQ test, suggests that the economic system under study has not undergone sudden fundamental changes that would undermine the estimated relationships. This enhances confidence in the predictive power of the model, allowing for more accurate economic forecasting and planning.

The results of the CUSUM and CUSUM-SQ tests, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, confirm the stability and robustness of the estimated ARDL model. The CUSUM test validates that the model’s coefficients remain consistent over time, while the CUSUM-SQ test further reinforces this stability by confirming the absence of structural breaks in variance. These findings indicate that the estimated relationships between economic growth, capital formation, labor participation, and natural resource rents are not only statistically significant but also economically meaningful and policy-relevant. Given these results, the estimated ARDL model can be confidently used for economic analysis and policy formulation, as it exhibits strong structural integrity and predictive reliability. Moving forward, policymakers can leverage these stable relationships to craft sustainable growth strategies that align with Tunisia’s long-term economic objectives.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The study estimates both the short- and long-run effects of the disaggregated natural resource rents-oil, forests, natural gas, and minerals-on Tunisia’s economic growth using the ARDL framework and a newly constructed Resource Diversification Index. Results indicate clear heterogeneity across resource categories, with oil and forest rents having statistically significant contributions to the long run, whereas natural gas and mineral rents do not report significant long-run effects. The positive and significant effect of the RDI points to resource diversification as stabilizing the country in terms of reduced exposure to sector-specific shocks.

These findings also indicate that the growth trajectory of Tunisia depends not only on the magnitude of resource rents but also on their composition and the institutional environment supporting them. The high contributions of oil and forest rents suggest sector-specific production structures that keep generating stable value added. On the other hand, the lack of statistical significance for natural gas and mineral rents reflects the structural inefficiencies, coupled with low value addition and institutional bottlenecks, which hamper their full contribution. The negative long-run effect of labor is in line with evidence on persistent skill mismatches, rigid labor markets, and weak vocational training systems in Tunisia. A significant negative error-correction coefficient confirms rapid adjustment toward long-run equilibrium and hence reinforces the relevance of resource diversification as a mechanism of building resilience against external shocks.

The poor performance of natural gas and mineral sectors should, therefore, be seen not as long-run contributors but as a lack of measurable growth impact. Resource-based growth in Tunisia depends mainly on oil and forest resources, supported by institutional quality and diversification/modernization strategies.

5.1. Policy Recommendations with Operational Measures

The empirical results from this study provide clear guidance for the design of targeted policy interventions. The recommendations below are explicitly derived from the estimated long-run and short-run coefficients of the ARDL model, ensuring that each policy action corresponds to a statistically validated relationship.

5.1.1. Capital Formation: Increase Investment in Productive Sectors

Empirical finding:

Capital has a positive and highly significant long-run effect on GDP coefficient = 0.1464, p < 1%.

Policy implication:

In addition, Tunisia could increase investments in high productivity spillover sectors by

- Increasing public investment in transport, logistics, and renewable energy infrastructure.

- This will involve facilitating private sector financing through credit guarantees, investment incentives, and tax relief for capital-intensive industries.

- Expanding partnerships with foreign investors in refining, energy, and mineral processing.

These measures directly enhance the growth-inducing role of capital, as emphasized in the model.

5.1.2. Labor Force: Correct Structural Labor Market Imbalances

Empirical finding:

Labor has a significant negative impact on growth (coefficient = −0.1161).

The result shows skill mismatches, low productivity, and rigid dynamics in the labor market.

Policy implication:

In this aspect, Tunisia needs to

- Sector-based skills renewal programs aligned with resource-related industries: gas, mining, and renewable energy.

- Reform vocational training centers into providing practical technical skills demanded by industries.

- Incentivize labor mobility to resource-based industrial cluster regions.

- Encourage firms in the adoption of productivity-enhancing technologies through subsidies and training grants.

These actions address the structural constraints behind the negative coefficient directly.

5.1.3. Oil and Forest Rents: Improved Sustainable Revenue Management

Empirical finding:

Positive and significant long-run effects on growth from oil rents and forest rents are strong.

Policy implication:

Policies should seek to stabilize and sustain these contributions through

- Improving the efficiency of oil extraction and refining activities.

- Enhancing port and pipeline infrastructure to reduce bottlenecks in exports.

- Support sustainable forest management plans in order to conserve long-run forest rent flows.

- Developing non-wood forest products and industries: medicinal plants, ecotourism, woodworking crafts.

These recommendations directly leverage the empirically established sectors that drive long-run growth.

5.1.4. Natural Gas and Mineral Rents: No Statistically Significant Impact

Empirical finding:

Natural Gas Rents and Mineral Rents: Estimates from the long-run ARDL model were insignificant.

Policy implication:

As these sectors’ coefficients are not significant, under the prevailing circumstances, they cannot be considered reliable growth drivers. Future policies should focus on structural bottleneck diagnoses rather than assuming direct growth effects.

5.1.5. Resource Diversification: RDI, Expand Multi-Resource Development

Empirical finding:

The RDI is positive and significantly influences economic stability and long-run growth.

Policy implication:

Diversification needs to be accelerated through:

- Integrating oil, gas, and mineral processing multi-resource industrial zones.

- Investment in renewable natural resource sectors: solar, wind, biomass.

- Export diversification promotion aimed at reducing dependence on volatile commodity markets.

These actions reinforce the stabilizing role detected through the RDI.

5.1.6. Economic Stability: Let Fast Adjustment Speed Go to Work

Empirical finding:

The ECT coefficient (−1.106) is large, negative, and highly significant. This means that Tunisia quickly returns to its long-run equilibrium.

Policy implication:

Such responsiveness enables Tunisia to

- Implement counter-cyclical fiscal policies to smooth out resource revenue shocks. Strengthen sovereign funds to stabilize income during price volatility.

- Promote predictable regulatory frameworks to keep investor confidence high.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions (Specified and Expanded)

The study has a number of limitations that provide avenues for future research:

Small Sample Size 1990–2023:

The limited number of observations may reduce the precision of long-run estimates. Future research could use higher frequency data, such as quarterly or monthly data, if available, to improve statistical robustness.

Excluding nonlinear and threshold effects:

The model does not capture potentially important nonlinearities such as thresholds beyond which resource dependence becomes harmful. Future studies may use threshold ARDL, smooth-transition regression, or quantile ARDL to ascertain whether impact of different resource categories may vary across regimes.

Limited Institutional and Governance Variables: Although left out methodologically, factors related to institutions also presumably mould resource–growth interactions. Future research might use indications of institutional quality, governance scores, and political stability to further flesh out how institutions interact with resources. RDI as a First Step to Diversification: The constructed RDI represents a useful aggregate measure, but it is not able to capture sectoral linkages or spillovers of technology. Future work could develop multi-dimensional diversification indices including export diversification and production complexity measures.

5.3. Final Remarks

The contribution of this study to a more nuanced understanding of Tunisia’s resource–growth relationship lies in its incorporation of short-run dynamics, the construction of a comprehensive diversification index, and providing operational and resource-specific policies. The results show that diversification and sector-specific strategies focusing on sectors with measurable growth effects are crucial to long-term sustainable economic development.

In light of related recent developments in the literature, this paper complements previous evidence on renewable energy transition and globalization dynamics [33], the macro-financial spillovers of emerging digital currencies [34], and the contribution of machine-learning innovations to financial stability [35]. These contributions collectively emphasize that diversification, technological upgrading, and institutional modernization are essential drivers of sustainable economic development.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (Grant Number: IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be forwarded to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hausmann, R.; Hwang, J.; Rodrik, D. What you export matters. J. Econ. Growth 2007, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Nabeshima, K. Can Malaysia Escape the Middle-Income Trap? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 4971; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Der-Ploeg, F. Natural resources: Curse or blessing? J. Econ. Lit. 2011, 49, 366–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. The curse of natural resources. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auty, R.M. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Corden, W.M.; Neary, J.P. Booming sector and de-industrialization in a small open economy. Econ. J. 1982, 92, 825–848. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M.L. The political economy of the resource curse. World Politics 1999, 51, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlum, H.; Moene, K.; Torvik, R. Institutions and the resource curse. Econ. J. 2006, 116, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P. Resource impact: Curse or blessing? A literature survey. J. Energy Lit. 2003, 9, 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, P.; Hoeffler, A. Resource rents, governance, and conflict. J. Confl. Resolut. 2005, 49, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulte, E.H.; Damania, R.; Deacon, R.T. Resource intensity, institutions, and development. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slimane, M.; Ben Hassine, H. Economic diversification in Tunisia: Challenges and opportunities. J. N. Afr. Stud. 2016, 21, 543–562. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, D.; Maloney, W.F. Natural Resources: Neither Curse nor Destiny; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnschweiler, C.N.; Bulte, E.H. The resource curse revisited and revised: A tale of paradoxes and red herrings. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. An African Success Story: Botswana; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Economics: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Tunisia Economic Monitor: Navigating the Pandemic; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Badeeb, R.A.; Lean, H.H.; Clark, J. The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: A critical literature survey. Resour. Policy 2020, 67, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, M.; Sohag, K.; Shahbaz, M. Natural resources, human capital, and economic growth: Evidence from developing countries. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 108, 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, K.; Bhattacharya, M.; Qazi, A.Q. Natural resources, environmental sustainability, and economic growth: A global perspective. Resour. Policy 2022, 75, 102–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bakari, S. The Impact of Natural Resources, CO2 Emission, Energy Use, Domestic Investment, Innovation, Trade and Digitalization on Economic Growth: Evidence from 52 African Countries; No. 114323; University Library of Munich: München, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bakari, S. The Role of Digitalization, Natural Resources, and Trade Openness in Driving Economic Growth: Fresh Insights from East Asia-Pacific Countries; No. 121643; University Library of Munich: München, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, G.D.; Radulescu, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Bansal, P. Do natural resources impact economic growth: An investigation of P5+ 1 countries under sustainable management. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Godil, D.I.; Bibi, M.; Khan, M.K.; Sarwat, S.; Anser, M.K. Caring for the environment: How human capital, natural resources, and economic growth interact with environmental degradation in Pakistan? A dynamic ARDL approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haseeb, M.; Kot, S.; Hussain, H.I.; Kamarudin, F. The natural resources curse-economic growth hypotheses: Quantile–on–Quantile evidence from top Asian economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H.M.; Khan, I.; Latif, M.I.; Komal, B.; Chen, S. Understanding the dynamics of natural resources rents, environmental sustainability, and sustainable economic growth: New insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58746–58761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; He, Z.W. Natural resources and green economic growth: An analysis based on heterogeneous growth paths. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, S.; Murshed, M.; Umarbeyli, S.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Ahmad, M.; Tufail, M.; Wahab, S. Do natural resources abundance and human capital development promote economic growth? A study on the resource curse hypothesis in Next Eleven countries. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabash, M.I.; Mesagan, E.P.; Farooq, U. Dynamic linkage between natural resources, economic complexity, and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Africa. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Nonlinear relationship between natural resources and economic growth: The role of frontier technology. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoman, W.; Majeed, A.; Vasbieva, D.G.; Yameogo, C.E.W.; Hussain, N. Natural resources abundance, economic globalization, and carbon emissions: Advancing sustainable development agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchoucha, M.; Bakari, S. The Impacts of Domestic and Foreign Direct Investments on Economic Growth: Fresh Evidence from Tunisia; MPRA Paper No. 94816; University Library of Munich: München, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/94816/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Gafsi, N. Foreign Finance and Renewable Energy Transition in D8 Countries: The Moderating Role of Globalization. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafsi, N. The Impact of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) on Global Financial Systems in the G20 Country GVAR Approach. FinTech 2025, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafsi, N. Machine Learning Approaches to Credit Risk: Comparative Evidence from Participation and Conventional Banks in the UK. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).