Abstract

Brazil is the world’s largest coffee producer, resulting in the production of 1 kg of husk and 0.5 kg of parchment for every 1 kg of coffee beans. Given the large amount of biomass and the constant need for energy production, this study raises the possibility of using waste for pellet production. Samples of coffee husks and parchment were characterized by moisture content (dry basis), proximate analysis (volatile matter, ash and fixed carbon), calorific value, elemental analysis, and thermogravimetry, and the pellets were characterized by moisture content (dry basis), bulk density, energy density, mechanical durability, percentage of fines, and hardness. The results were compared with the ISO 17225-6. The parchment had a higher carbon, 49.5%, C/N 45.1%, and lignin 26.2% and lower ashes 2.8% and extractives 14.2%, resulting in higher calorific value, while coffee husks obtained 46.5%, 26.3%, 24.6%, 5.5%, and 34.3%, respectively. Pellets produced with parchment had a higher density 622 kg/m3 and lower moisture content 10.5%, resulting in higher energy density. The parchment pellets met all the parameters of the ISO 17225-6, while the coffee husk pellets did not meet the parameters for moisture, which is less than 15%, and bulk density, greather than 600 kg/m3. Both types of biomass showed potential for pellet production, with further studies needed on coffee husks.

1. Introduction

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock [1], the coffee harvest in 2024 covered 1.9 million hectares, producing 54 million processed bags. This represents a 1.4% increase in production, but a slight decrease of 0.5% compared to 2023. Paradoxically, while production grows, per capita consumption shows a downward trend. Data from the Brazilian Coffee Industry Association [2] reveal a 2.22% decline in consumption between November 2023 and October 2024, with figures dropping to 6.26 kg/inhabitant/year for green coffee and 5.01 kg/inhabitant/year for roasted coffee. Despite this decrease, Brazil remains the world leader in per capita coffee consumption, with domestic demand accounting for 40.4% of total production.

Brazil’s 2025 coffee harvest (projected at 51.8 million bags from 2.25 million hectares) presents a significant waste management challenge. Processing is expected to convert 50–60% of green coffee beans into approximately 6 million tons of residual biomass annually [3,4].

The anatomically mature coffee cherry consists of several distinct structural layers: the exocarp (outer skin), mesocarp (pulp), mucilage (a gelatinous layer rich in sugars), endocarp (commonly referred to as parchment), silver skin (a thin tegument), and the coffee bean itself. During post-harvest processing, particularly in dry and semi-wet methods, a significant amount of biomass is generated as byproducts. Mass balance analysis indicates that for every kilogram of green coffee beans produced, approximately 1 kg of husk (comprising the exocarp, mesocarp, and mucilage) and 0.5 kg of parchment (including the endocarp and silver skin) are generated. These residues, often underutilized, represent a promising source of lignocellulosic biomass for energy generation and value-added applications such as pellet production, contributing to circular bioeconomy strategies in coffee-producing regions [5,6].

As Brazil’s dominant coffee-producing state, Minas Gerais generates the largest volume of processing residues nationally. Coffee plantations cover a large part of the agricultural land, highlighting both the scale of residue production and the critical need for sustainable valorization approaches. This substantial biomass availability presents significant opportunities for circular economy implementation in Brazil’s coffee sector [7].

The scientific community has developed multiple sustainable pathways for agricultural waste valorization. Shu et al. [8] demonstrated that anaerobic digestion of oil extraction residues from Jatropha curcas and Pongamia pinnata offers dual benefits: mitigating agricultural pollution while generating renewable biogas. Alternatively, lignocellulosic biomass can be converted into second-generation (2G) ethanol, producing biofuel and enabling the extraction of high-value bioactive compounds simultaneously [4,9]. For solid fuel applications, biomass densification yields pellets with superior combustion characteristics for industrial boilers and furnaces [10,11], representing a third distinct valorization pathway.

The transformation of biomass into pellets enables decentralized and efficient energy management, particularly in rural and agro-industrial contexts. Pellet production is relatively simple, requiring minimal infrastructure and no chemical pretreatment, which facilitates local implementation and reduces operational complexity. According to Lima Filho [12] and He et al. [13], pellets offer several advantages over traditional firewood, including improved combustion efficiency, reduced labor requirements, lower transportation and storage costs, and more consistent thermal performance. Brazil has an estimated pellet production potential exceeding 765,000 tons per year, driven by increasing demand in both domestic and international markets.

Furthermore, studies such as those by He et al. [13], Mack et al. [14] and Kamperidou [15] emphasize that the quality of the raw biomass and the physical properties of the resulting pellets—such as density, durability, calorific value, and ash content—play a critical role in combustion performance and environmental impact. Therefore, careful selection and characterization of the feedstock are essential, along with monitoring post-production parameters like particle size distribution, moisture content, and structural integrity. These factors directly influence the energy yield, mechanical resistance, and suitability of pellets for various thermal applications, reinforcing the importance of quality control throughout the production chain.

This study aimed to assess the quality of two residual biomasses derived from coffee production in the Triângulo Mineiro region, husk and parchment, for their suitability in energy generation and their potential for pellet manufacturing, given that there are no studies focused on the use of these residues as energy biomasses in the region and considering the variety of coffee produced, since the variety alters its chemical and physical composition. By optimizing production parameters for small-scale feasibility, we aim to provide coffee growers and processors with a sustainable waste valorization strategy that addresses two critical challenges simultaneously: the cyclical biomass surplus from coffee’s biennial production pattern and the current environmental burden of uncontrolled residue disposal. Successful implementation could establish a circular economy model, converting agricultural waste into renewable energy while generating supplemental income for coffee-producing communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material

The coffee residue was obtained from Coffea arabica plantations in Monte Carmelo, Minas Gerais state, Brazil (18°44′5″ S, 47°29′47″ W). The waste material was separated into two components: coffee husk, which is removed during the initial processing stage after harvesting, and parchment, which is eliminated after bean drying (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Coffee husk (A) and parchment (B). Source: Personal archive.

2.2. Biomass Characterization

The coffee husk and parchment residues were first sun-dried to reduce initial moisture content. Once dried, the materials were mechanically ground and sieved through a 200-mesh (75 μm) sieve to achieve uniform particle size distribution. The fraction retained on the sieve was reserved for moisture content determination, while the finer pass-through fraction was used for subsequent physicochemical characterization. Moisture content (dry basis) was determined by oven-drying representative samples at 105 ± 2 °C in a forced-air oven until constant mass was achieved (defined as less than 0.1% weight variation between successive measurements). The moisture (dry basis) content was then calculated using Equation (1) and for the calculation of moisture (wet basis) Equation (2) was used.

The proximate analysis was carried out using the methodology described in the Brazilian Standard (NBR) 8112 of the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT) of 1986 [16], which determined the values for ash content, volatile material, and fixed carbon. Higher calorific value (HCV) was measured using the methodology adapted from NBR 8633 of the ABNT [17]. The use of national evaluation methodologies is due to the need to comply with local laboratory standards; however, the regulations are inspired by and translated from international standards in order to avoid errors during the translation of specific terms.

The lower calorific value (dry basis) (LCVdry) and the lower calorific value (as received) (LCVar) were calculated based on Equations (3) and (4) taken from Hafford et al. [18]:

Elemental analysis (CHNS) was carried out using CHNS-O Flash EA 1112 Series (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milan, Italy) equipment, using 2.5 g of coffee husks and parchment that had passed the 200-mesh sieve. Thermogravimetric analysis was carried out using Shimadzu DTG-60H equipment (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) in an oxidizing atmosphere, with a flow rate of 50 cm3 min−1, in a temperature range of 25 to 600 °C, with a sweep of 10 °C min−1.

The combustion (S) and ignition (Dig) indices were calculated according to Equations (5) and (6), adapted from Moon et al. [19], presented below with the data found through thermogravimetric analysis.

where ()max represents the maximum combustion rate (% min−1), ()med denotes the average mass loss rate over the temperature range from ignition to complete burnout of its carbon residue (% min−1), Ti is the ignition temperature (°C), Tf is the burnout temperature (°C), tc is the time corresponding to the maximum combustion rate (min) and ti is the ignition time.

2.3. Pellet Production

The pellets were produced using two coffee byproducts: coffee husks and parchment. This selection was based on their differing availability and utilization potential within coffee production systems. While coffee husks face competing uses, particularly as ground cover, parchment remains an underutilized residue with no established alternative applications.

The pellets were produced by densifying the material using an Eng-Maq® 0200v (ENG-MAQ Industrial Equipment Ltda, Boa Esperança do Sul, São Paulo, Brazil) (Figure 2) pelletizer capable of producing 110 kg per hour and a 6 mm diameter horizontal flat die. For the study, 10 kg of pellets were produced in each treatment, and the pelletizer worked at a temperature of 80 to 95 °C and a compaction pressure of 300 kgf per cm2. After leaving the machine, they were taken to an air-conditioned chamber at 25 °C and 50% relative moisture to cool and stabilize the mass.

Figure 2.

Eng-Maq® 0200v. Source: Personal archive.

2.4. Pellet Characterization

The dimensions of the pellets, diameter (mm), and length (mm) were measured according to DIN EN 16127 [20]. The apparent density was calculated from the ratio between the mass after acclimatization and the volume displaced after immersion in mercury, and the energy density was calculated from the ratio between the higher calorific value and the apparent density.

The equilibrium moisture content (dry basis) was found after drying in an oven at 103 °C for 24 h and reweighing and was calculated using Equation (7). The moisture content (wet basis) was determined using Equation (8).

Mechanical durability and the percentage of fines were determined with particles smaller than 3.15 mm, following DIN EN 15210-1 [21] using Holmen® Ligno-Tester (TEKPRO, North Walsham, UK) equipment. Hardness was determined using a diametrical compression test using a manual Amandus Kahl durometer (Kahl, Reinbek, Germany) with a scale of up to 100 kgf, where a force was applied until fracture.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The coffee husk and parchment characterization tests were subjected to Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level, while the pellet characterization was subjected to Student’s t-test with a 95% confidence level.

3. Results

3.1. Biomass

Table 1 presents a detailed comparative analysis of the physicochemical parameters of coffee husk and parchment. Significant differences were observed in most of the evaluated parameters (Table 1), which can be attributed to these biomasses’ distinct functional roles and structural positions [4].

Table 1.

Average values of physicochemical parameters of coffee husks and parchment.

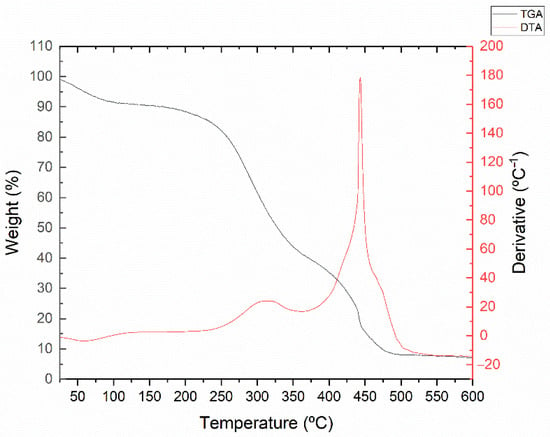

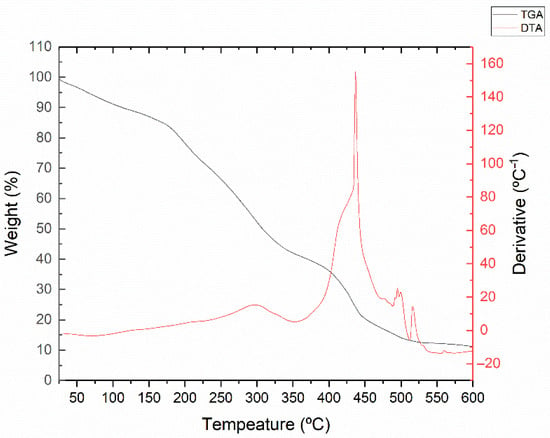

The results of the thermogravimetric analysis with derivative thermogravimetry (TGA/DTG) show different results for the biomasses, shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. These differences align with the data found in the chemical analysis since, even though they are components of the coffee fruit, their morphological and functional differences lead to differences in composition and, consequently, in thermal degradation.

Figure 3.

TGA/DTA curves of parchment. Heating rate 10 °C min−1, in an oxidizing atmosphere with a flow rate of 50 cm3 min−1.

Figure 4.

TGA/DTA curves of coffee husk. Heating rate 10 °C min−1, in an oxidizing atmosphere with a flow rate of 50 cm3 min−1.

Observing Figure 3 and Figure 4, it is possible to see that the DTA in Figure 4 shows peaks in the region between 450 and 550 °C, which demonstrates that the lignin present in the coffee husk is more reactive than the lignin present in the parchment, leading to a slower mass loss at higher temperatures, as can be observed in the TGA curves in the same region.

Table 2 was assembled using the data found in the TGA/DTA curves for parchment and coffee husks to compare and understand the data better.

Table 2.

Thermogravimetric data found from the TGA and DTA curves for parchment and coffee husks.

The combustibility (S) and ignition (Dig) indices for the coffee husk and parchment samples are shown in Table 3, where they are compared with three other biomass residues that have already been investigated in the literature for their potential application in energy generation.

Table 3.

Combustibility parameters for parchment and coffee husk samples.

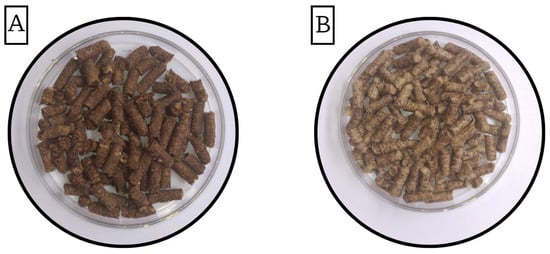

3.2. Pellets

In Figure 5, it is possible to observe that the pellets already present a visual difference based on the biomass that was used. It was possible to observe a significant difference for most of the parameters investigated for the pellets (Table 4). This difference can be explained by the difference in the chemical and physical constitution of the materials.

Figure 5.

Pellets made of coffee husk (A) and parchment (B). Source: Personal archive.

Table 4.

Average values of the pellet parameters produced with coffee husks and parchment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Biomass

The bulk density of coffee husk was higher (215.4 kg/m3) than parchment (104.2 kg/m3). Bulk density directly influences transportation, storage efficiency, and pellet production processes, as lower-density materials require greater volume handling for equivalent mass inputs during pelletization.

Chemical analysis revealed that parchment exhibited the highest carbon content, constituting 49.6% of its composition, compared to 46.5% for coffee husk. These values vary from literature reports: Díaz-Jiménez and Moya [24] reported 41% carbon content for coffee husk, while Otoni et al. [25] obtained 45.9%. Similarly, Wondemagegnehu et al. [26] documented 43.5% carbon content for parchment, compared to 46.3% reported by Campos et al. [27]. These discrepancies may arise from genetic variations among cultivars, differing climatic conditions, and distinct crop management practices.

Oxygen content analysis revealed that coffee husk contained the highest percentage (45.3%), closely aligning with the 44.9% reported by Díaz-Jiménez and Moya [24]. This value was substantially higher than the 35.5% observed by Otoni et al. [25] for similar material. In contrast, parchment showed significantly lower oxygen content (42.45%) compared to literature values: 50.12% reported by Wondemagegnehu et al. [26] and 46.2% documented by Campos et al. [27].

The hydrogen content showed no statistically significant difference between samples, with 6.7% and 6.33% values. These results exceed the 5.3% reported by Wondemagegnehu et al. [26] and align closely with values from Campos et al. [27] (6.4%), Díaz-Jiménez and Moya [24] (6.3%), and the Reis and Reis [7] (6.3%). However, they differ from the higher value of 7.93% reported by Otoni et al. [25].

Both carbon and hydrogen content significantly influence biomass calorific value, as these elements contribute to energy production during combustion. A lower C/H ratio is particularly advantageous for combustion efficiency, while elevated oxygen content typically reduces calorific value [28].

Nitrogen content analysis revealed that coffee husk contained the highest value (1.77%), closely matching the 1.9% reported by both Díaz-Jiménez and Moya [24] and Otoni et al. [25]. In contrast, parchment showed significantly lower nitrogen content (1.1%), though still substantially higher than values reported by Wondemagegnehu et al. [26] (0.5%) and Campos et al. [27] (0.4%).

Regarding sulfur content, coffee husk exhibited the highest concentration (0.181%), consistent with the 0.18% found by Otoni et al. [25]. Parchment contained 0.149% sulfur, with both values being lower than those reported by Díaz-Jiménez and Moya [24] (0.32%) and Wondemagegnehu et al. [26] (0.2%).

These elements present significant environmental and operational concerns, as sulfur and nitrogen contents directly contribute to forming sulfur oxides (SOx) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) during combustion. These emissions pose toxicity risks and form acidic compounds upon cooling that accelerate the corrosion of combustion equipment [28].

Coffee husk had a fixed carbon content of 23.3%, a value higher than that found by Poyilil, Palatel, and Chandrasekharan [29], of 14% and Setter et al., [20], of 19.36%, while parchment had a fixed carbon content of 20.7%, which shows that both materials have potential for energy purposes. Fixed carbon is the part of the biomass that remains after removing the volatile material, moisture, and ash. It is an important indicator of energy potential since it is linked to the lignin content and has a positive influence on calorific value, in addition to the fact that higher values result in slower and consequently more efficient combustion [29,30].

Parchment had the highest values for total lignin, 26.2%; holocellulose, 59.7%; and volatile material, 76.7%, while coffee husks had the highest values for extractives, 34.4%, fixed carbon, 23.3%, and ash, 5.5%. Arango-Agudelo et al. [31] found different values for parchment, with 7.87% soluble lignin, 17.66% Klason lignin, 22.7% cellulose, 4.2% hemicellulose, 7.95% ash, and 7.87% extractives in water. Reis et al. [32] show values for parchment lignocellulosic material of 7% extractives, 53% lignin, and 22% cellulose. For coffee husks, the ash content differs from that found by Otoni et al. [25], of 7.8%, as well as from the values found by Díaz-Jiménez and Moya [24] for cellulose of 34%, total lignin of 78.2% and fixed carbon of 2.4%. A high volatile material content indicates that it will be easier to ignite the material, Setter et al. [33], and given that the materials showed values above 70%, it can be predicted that the pellets produced will be highly reactive fuels.

The coffee husk has a first mass loss of around 12%, which includes the removal of water and part of the volatile materials since it was not possible to find the Tmax H2O (°C), which is not the case with parchment, where the first mass loss was close to 8.03%, with the Tmax H2O (°C) pronounced at 120.77 °C, a mass which is close to the moisture found in the biomass characterization. Both materials contain two well-defined events in the degradation process, the first comprising the degradation of the cellulosic and hemicellulosic portions of the lignocellulosic material, and the second event, where the lignin fraction, which has a heterogeneous and more complex chain in a three-dimensional arrangement, degrades at higher temperatures [34]. However, looking at the percentage of final residue and the ash content of the chemical analysis, it can be seen that even reaching 600 °C, all the material could not be consumed, showing that it would be necessary to carry out the analysis at higher temperatures for total consumption of the material.

The S parameter, also called the comprehensive combustion index because it considers all combustion phases, including ignition and burnout, indicates that higher S values, when comparing different biofuels, are related to better combustion performance of this biofuel through simple ignition and effective burnout [22]. It can, therefore, be inferred that the S values of parchment and coffee husks are very close and higher than those of biomass and coal, indicating the potential use of these two sources.

Meanwhile, the ignition rates (Dig) obtained for coffee husk and parchment were also very close to each other and, although lower than sugar cane, were higher than the coal and cereal straw samples investigated by Wnorowska et al. [23]. As Dig is commonly related to the stability of biofuel combustion, where high values indicate that a material has a more stable combustion characteristic, it can be said that both coffee residues investigated are more stable than some types of coal, for example.

4.2. Pellets

Regarding the lower calorific valuear (LCVar), it was possible to see that the pellets produced from parchment have a higher average, with 16.17 MJ/Kg, while the coffee husk has 13.41 MJ/Kg. According to the Reis and Reis [7], the lower calorific valuear of coffee biomass (coffee husk + parchment) is 14.90 MJ/Kg, which can be explained by the fact that the values for both parts are shown together, and when they are observed separately, they are just above and below what is reported. The biomass that is expected to be transformed into solid biofuel must have high LCVar values, as this will have a tangible impact on the heat generation of this material, since the energy needed to remove the moisture and water formed in the combustion process has already been removed.

The length, diameter, and durability of both pellets produced with coffee husks and parchment had statistically equal averages, with the only difference being in the fines content, where parchment had the lowest value. Mack et al. [14] state in their research that the size of the pellet has a major influence on its burning behavior, from the flow of mass to the production of gases during burning, as well as the importance of the material having a low fines content since these can lead to the extinction of burning if they are in large volumes. Durability is an important factor when it comes to transporting pellets since it is from this that it is possible to see whether the material will be resistant to external forces that could lead to it breaking and subsequently increasing the fines content. In order to better visualize the results obtained with the pellets, Table 5 shows how the results compare to ISO 17225-6 (ISO, 2021) [35], which was used as a basis, given the lack of national regulations.

Table 5.

Classification of pellets according to quality standard ISO 17225-6 [35].

Based on what has been demonstrated, it is possible to observe that pellets produced with parchment can be marketed at the highest quality level of ISO 17225-6 [35], while those produced from coffee straw are not suitable for marketing, since they do not meet the minimum value of 600 kg/m3 bulk density and the moisture content was greater than 15%, factors that can be corrected by changes in the pelletization process, but resulting in marketing in category B due to the nitrogen content being greater than 1.5%.

5. Conclusions

The direct pelletization of coffee processing residues, husk, and parchment proved technically viable for producing standardized solid biofuels without energy-intensive pretreatments. While both materials yielded quality pellets, practical differences emerged during processing: coffee husk required substantially longer drying periods than parchment to reach the critical moisture after the compaction. The pellets produced from parchment conformed to ISO 17225-6 at the highest qualification, demonstrating that they are an alternative to traditional firewood and a decentralized economic opportunity for coffee farms. And in the case of coffee husk pellets, even if they do not achieve the necessary properties, it is possible that changes in the pelletization and drying process will achieve the necessary levels. Future work should optimize drying protocols for husk residues and evaluate the technical and economic feasibility of farm-level pellet production systems to facilitate widespread adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.J.V.Z., A.G.C. and O.P.L.; Methodology: S.G.W., A.G.C., M.V.F. and O.P.L.; Formal analysis: S.G.W., M.V.F. and S.d.O.A.; Writing—original draft: S.G.W., O.P.L., A.d.C.O.C. and S.d.O.A.; Writing—review and editing: S.G.W., A.G.C., O.P.L., A.d.C.O.C. and S.d.O.A.; Supervision: A.G.C. and A.d.C.O.C.; Investigation: M.V.F. and S.d.O.A.; Validation: M.V.F.; Resources: A.d.C.O.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by “Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais—FAPEMIG”, funding numbers APQ-04100-23; APQ-05311-24; and APQ-05431-24.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

There was no support, financial or material, from entities other than those already mentioned.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA). Coffee Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/cafe/boletim-da-safra-de-cafe (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Brazilian Coffee Industry Association (ABIC). Coffee Industry Indicators. 2024. Available online: https://www.abic.com.br/estatisticas/indicadores-da-industria/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- CONAB—National Supply Company. Monitoring the Brazilian Coffee Crop; National Supply Company: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, I.G.C.B.; Antonio, A.d.S.; Carvalho, E.M.d.; Santos, G.R.C.d.; Pereira, H.M.G.; Veiga Júnior, V.F.d. Method optimization for the extraction of chlorogenic acids from coffee parchment: An ecofriendly alternative. Food Chem. 2024, 458, 139842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulart, P.d.F.P.; Alves, J.D.; Castro, E.M.d.; Fries, D.D.; Magalhães, M.M.; Melo, H.C.d. Histological and morphological aspects of different grain coffee qualities. Ciência Rural 2007, 37, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gómez, J.A.; Florez-Prado, L.M.; Leguizamón-Vargas, Y.C. Valorization of coffee byproducts in the industry, a vision towards circular economy. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.J.d.; Reis, L.S.d. Biomass Atlas of in Minas Gerais; Rona Gráfica e Editora: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, H.; Zhang, P.; Chang, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S. Agricultural Waste. Water Environ. 2015, 87, 1256–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, A.V.; Gerolamo, L.E.; Dinamarco, T.M.; Tapia-Blácido, D.R. Optimization of biomass saccharification processes with experimental design tools for 2G ethanol production: A review. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2023, 17, 1789–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Ali, B.; Mao, X.; Hussain, S.; Fu, J.; Ao, W.; Zhou, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, G.; et al. Pyrolysis of pellets prepared from pure and blended biomass feedstocks: Characterization and analysis of pellets quality. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 161, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabichi, I.; Yaacoubi, F.E.; Ennaciri, K.; Sekkouri, C.; Bacaoui, A.; Yaacoubi, A. Transforming olive-processed waste and almond shells into high-quality Biofuels: A comprehensive development and evaluation approach. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 8671–8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Filho, R.R.d. Nota Técnica: Conjuntura e Expectativas: Pellets de Madeira e Madeira Para Lenha. Confederação da Agricultura e Pecuária do Brasil (CNA), nº 30. 2022. Available online: https://www.cnabrasil.org.br/publicacoes/conjuntura-e-expectativas-pellets-de-madeira-e-madeira-para-lenha (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- He, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Wu, K. Effects of different biomass feedstocks on the pelleting process and pellet qualities. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 69, 103912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, R.; Schön, C.; Kuptz, D.; Hartmann, H.; Brunner, T.; Obernberger, I.; Behr, H.M. Influence of pellet length, content of fnes, and moisture content on emission behavior of wood pellets in a residential pellet stove and pellet boiler. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 14, 26827–26844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperidou, V. Quality Analysis of Commercially Available Wood Pellets and Correlations between Pellets Characteristics. Energies 2022, 15, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBR 8112; Charcoal: Immediate Analysis. Brazilian Association of Technical Standards: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1986.

- NBR 8633; Charcoal: Determination of Calorific Value. Brazilian Association of Technical Standards: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1983.

- Hafford, L.M.; Ward, B.J.; Weimer, A.W.; Linden, K. Fecal sludge as a fuel: Characterization, cofire limits, and evaluation of quality improvement measures. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 2437–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.; Sung, Y.; Ahn, S.; Kim, T.; Choi, G.; Kim, D. Effect of blending ratio on combustion performance in blends of biomass and coals of different ranks. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2013, 47, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16127; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Length and Diameter of Pellets. Deutsches Institut für Normung: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- EN 15210-1; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Mechanical of Pellets and Briquettes. Deutsches Institut für Normung: Berlin, Germany, 2010.

- Aniza, R.; Chen, W.-H.; Kwon, E.E.; Bach, Q.-V.; Hoang, A.T. Lignocellulosic biofuel properties and reactivity analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) toward zero carbon scheme: A critical review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnorowska, J.; Ciukaj, S.; Kalisz, S. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Solid Biofuels with Additive under Air Atmosphere. Energies 2021, 14, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Jiménez, E.; Moya, R. The Efects of Jatropha curcas and Ricinus communis Seeds Addition on Cofee Pulp Waste Pellets as Fuel. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3071–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, J.P.; Matoso, S.C.G.; Pérez, X.L.O.; Silva, V.B.d. Potential for agronomic and environmental use of biochars derived from different organic waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondemagegnehu, E.B.; Gupta, N.K.; Habtu, E. Coffee parchment as potential biofuel for cement industries of Ethiopia. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 44, 5004–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.A.F.; Perez, J.P.H.; Block, I.; Sagu, S.T.; Celis, P.S.; Taubert, A.; Rawel, H.M. Preparation of Activated Carbons from Spent Coffee Grounds and Coffee Parchment and Assessment of Their Adsorbent Efficiency. Processes 2021, 9, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.B.; Zanuncio, A.J.V.; Carvalho, A.G.; Carneiro, A.d.C.O.; Castro, V.R.d.; Carvalho, A.M.M.L.; Assunção, R.M.N.d.; Araujo, S.d.O. Sustainable Solid Biofuel Production: Transforming Sewage Sludge and Pinus sp. Sawdust into Resources for the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyilil, S.; Palatel, A.; Chandrasekharan, M. Physico-chemical characterization study of coffee husk for feasibility assessment in fluidized bed gasification process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 51021–51053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, C.; Ataíde, C.H.; Mendes, R.F.; Oliveira, T.J.P.d. Influence of particle size on the physico-mechanical and energy properties of briquettes produced with coffee husks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8215–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Agudelo, E.; Rendón-Muñóz, Y.; Cadena-Chamorro, E.; Santa, J.F.; Buitrago-Sierra, R. Evaluation of Colombian Coffee Waste to Produce Antioxidant Extracts. BioResources 2023, 18, 5703–7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.S.; Tienne, L.G.P.; Souza, D.d.H.S.; Marques, M.d.F.V.; Monteiro, S.N. Characterization of coffee parchment and innovative steam explosion treatment to obtain microfibrillated celulose as potential composite reinforcement. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 9412–9421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, C.; Borges, C.R.; Mendes, R.F.; Oliveira, T.J.P. Energy quality of pellets produced from coffee residue: Characterization of the products obtained via slow pyrolysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 154, 112731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraj, P.; Arun, P.; Muraleedharan, C. Thermochemical conversion of coffee husk: A study on thermo-kinetic analysis, volatile composition, and ash behavior. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 20723–20740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17225-6; Solid Biofuels—Fuel Specifications and Classes—Part 6: Graded Non-Woody Pellets. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).