Abstract

This article investigates technological choices for Waste-to-Energy (WtE) implementations in Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) management. It identified challenges and opportunities, thereby transforming the perspective of MSW from waste into a valuable resource. The methodology included a systematic literature review, following PICO and PRISMA protocols. The analysis included 118 open-access review articles, published between 2018 and 2024, from Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect, concerning thermochemical, biochemical, and chemical technologies. Key challenges for new implementations include economic barriers, social issues, and regulatory shortcomings. Opportunities arise from education, supportive policies, and lessons learned from developed countries such as Germany and Japan. Limitations include the focus on specific databases and the potential oversight of data from other sources or unexamined data. Implications for future research should expand coverage as well as assess longer periods to enhance MSW valorization. Implications also include guidance for public managers and policymakers in formulating MSW management strategies, including policies, WtE technology selection, public education, and reducing misinformation to boost implementation and social acceptance of WtE initiatives. Effective WtE implementation improves public health and the environmental performance of regions by reducing landfills and generating economic and employment opportunities for vulnerable communities. The study’s originality lies in bridging a significant research gap on WtE implementation through a comprehensive examination of its challenges and opportunities. By integrating international experiences and lessons learned, it generates guidance for the sustainable development of MSW management systems.

1. Introduction

Enhanced welfare has led to a significant rise in the global population from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 8.1 billion in 2024 [1], resulting in large metropolitan areas that generate substantial amounts of municipal solid waste (MSW) [2]. Historically, communities have relied on landfills, which now face limited capacity and adverse environmental implications [3]. As MSW generation is expected to increase from 2.1 billion tons in 2023 to 3.8 billion tons in 2050, management costs are expected to rise from $361 billion in 2020 to $640.3 billion in 2050 [1].

The impact of MSW is not uniform among nations. In 2016, high- and middle-income countries, representing 49.6% of the global population, generated 66% of MSW, while lower-middle and low-income countries, with 51.4% of the population, contributed 34% [4]. In developing countries, limited funding leads to precarious sanitary landfill and collection service networks [5], affecting approximately 700 million people globally [1]. Additionally, MSW is the third-largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions, after fossil fuel combustion and enteric fermentation [6]. Such issues require strategic management involving collection, segregation, treatment, and sustainable disposal [2].

Waste-to-energy (WtE) initiatives can mitigate the effects of inadequate MSW management strategies [7]. This study focuses on three main types of WtE processes: (i) thermochemical (incineration, gasification, pyrolysis); (ii) biochemical (anaerobic digestion, fermentation); and (iii) chemical (esterification) [8,9,10,11,12]. More advanced variations, such as plasma gasification, are still in development for large-scale applications [13]. A selected set of high-impact studies have discussed WtE implementations in countries such as China, India, USA, Africa, Colombia, Turkey, Brazil, Germany, Pakistan, Japan, Bangladesh, Russia, and Serbia [2,7,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. A search in the Scopus database between 2022 and 2025, under the keywords “Municipal Solid Waste Management”, retrieved 865 articles. A second similar search under the keywords “Municipal Solid Waste Management” and “Waste to Energy” retrieved 297 articles. A third search, under the keywords “Municipal Solid Waste Management”, “Waste to Energy”, and “Guidelines”, retrieved five articles. Replacing “Guidelines” with “New Projects” OR “Benchmarking” retrieved two articles. The first and second searches confirm the relevance of the theme. The third suggests an underexploitation of guidelines or benchmarking practices for implementations of WtE from MSW.

This study addresses this gap by examining WtE implementations and deriving guidelines that can be useful for new implementations. In the particular case of developing countries, rapid urbanization, distinct socio-economic conditions, high organic waste fractions, and constrained infrastructure usually create specific challenges and opportunities that must be addressed prior to implementation. Based on the previous rationale, the research question is: How can MSW management be optimized through the implementation of new WtE? The originality lies in the investigation of strategies and new technologies for the efficient management of MSW, providing insights into practical applications. The purpose of the article is to present recommendations and policies to optimize MSW management through the adoption of WtE technologies. The methodology comprises a systematic literature review, which enables a comprehensive analysis of current practices and identifies opportunities for innovation and sustainable improvements.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 is a materials and methods section; Section 3 and Section 4 are dedicated to presenting and discussing the results, focusing on the main technologies for WtE implementation as well as the key challenges and opportunities in developing countries; and Section 5 is a final summarizing section that highlights limitations and recommendations for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The search included Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect databases, considering review articles published between 2018 and 2024. The methodology applied the PICO and PRISMA protocols. The PICO protocol (in our case, PICO stands for Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) is used to structure focused research questions, primarily in systematic literature reviews, helping to define the problem and identify key terms for database searching. In short, its primary use is to create focused, answerable questions that facilitate a precise search for evidence. PICO was used to identify the search string (“waste to energy” or “municipal solid waste”) in the title, abstract, or keywords, as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria (inclusion: new implementations; exclusion: absence of MSW concerns). Finally, the search derived three intermediate research questions.

- IRQ1: What are the main WtE technologies for MSW management?

- IRQ2: How can different WtE technologies contribute to MSW management?

- IRQ3: What are the challenges, opportunities, and benchmarks for adopting WtE technologies in MSW management?

Table 1 shows PICO attributes.

Table 1.

PICO attributes.

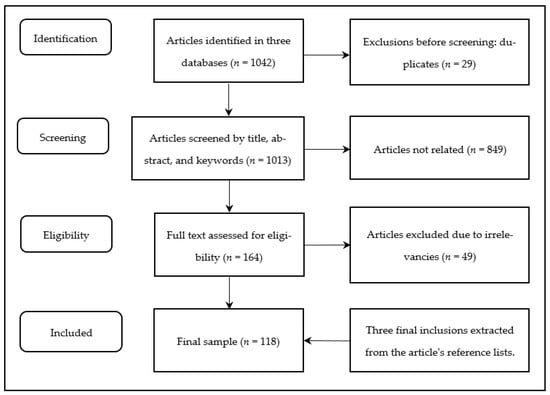

PRISMA is a guideline, consisting of a flowchart and a checklist, that aims to improve the reporting and transparency of systematic reviews, informing readers about why the review was conducted, the methods used, and the results found. Starting from the PICO definitions, PRISMA was used to identify, screen, select, and include references. No further filter related to the area of application was applied to ensure variety. A total of 1042 documents were identified, with 29 duplicates. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 164 articles were selected for full reading. From these, 49 were considered irrelevant, and three were added from reference lists, yielding 118 articles categorized into two groups according to the primary content: (a) available WtE technologies, and (b) guidelines, benchmarks, challenges, and opportunities for WtE in MSW management. Additionally, 61, 51, and 45 documents were linked to IRQ1, IRQ2, and IRQ3, respectively. Figure 1 and Table 2 show the Prisma flowchart and checklist, respectively.

Figure 1.

Prisma steps [29].

Table 2.

PRISMA checklist.

3. Systematic Review Findings: An Overview of WtE Technologies and Applications

3.1. Municipal Solid Waste Pathways

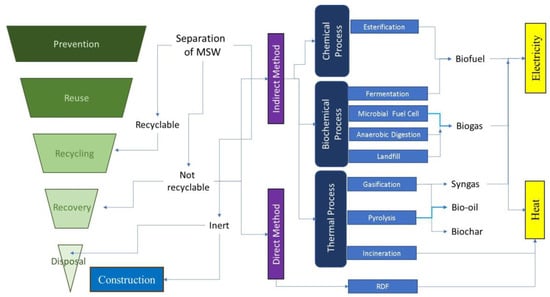

MSW can be organic and inorganic, comprising everyday items such as packaging, food waste, paper, plastics, wood, textiles, metals, and glass [30]. High-income countries generate lower fractions of organic waste than middle and low-income countries (32%, 53%, and 57%, respectively) [31]. Figure 2 illustrates the value pathways of MSW, from its sources to final destinations, emphasizing that prevention is prioritized over disposal and that MSW should be viewed as a resource rather than waste.

Figure 2.

MSW Value Pathways (own creation based on [32,33,34]).

The figure illustrates how different compositions influence management and energy recovery options, reinforcing the need for context-specific strategies. A solution in high-income countries (e.g., mass incineration for energy recovery of mixed waste) may be less efficient or even unsuitable for a developing country with higher moisture and organic fraction. While recovering energy from organic waste in developing countries can help reduce methane emissions from landfills and provide a renewable energy source, recycling of plastics and metals in developed countries reduces the need for virgin material.

3.2. Thermochemical Technologies: Incineration, Gasification, Pyrolysis

In thermochemical processes, energy is recovered from MSW through heating, with outcomes varying according to temperature and oxygen levels. The primary methods are incineration, gasification, and pyrolysis [11].

Before delving into specific processes, it is important to understand refuse-derived fuel (RDF), a solid fuel originating from non-hazardous waste and suitable for thermochemical conversion and energy recovery [19]. A key step in RDF production is sorting, a physical pre-treatment achieved through techniques such as drying, mechanical separation, and screening, which removes most biodegradable fractions and metals, as well as glass, chlorine-rich materials, and other inorganics [30]. RDF is useful to industries for heat, energy, or combined heat and power, often in cement kilns and incinerators, and can be co-combusted with coal or biomass in thermal technologies such as gasification or incineration to enhance efficiency, as well as in pyrolysis for high-quality bio-oil [35]. In Germany, RDF production involves mechanical-biological treatment plants where foreign materials and harmful substances are removed, followed by shredding, dehydration, and drying, which reduces the volume by approximately 70%. Materials are then separated into ferrous and non-ferrous metals, with a focus on recovering batteries and electronic scrap. The final mix consists of recyclable metals and electronic materials; RDF is reduced to less than 50% of its original volume with an increased calorific value; and inert mineral fractions, such as glass, ceramics, and stones, that can be repurposed for construction [36].

Incineration relies on accurate prediction of calorific value and effective combustion control for optimal performance. Modern WtE plants employ AI to improve stability, reduce response time, and enhance energy recovery by controlling air supply and feed rate [37]. AI algorithms can analyze real-time data from sensors (e.g., temperature, gas composition, and steam flow) to make instantaneous adjustments, predict potential issues, and dynamically optimize the combustion process [38]. As MSW is inherently heterogeneous, its composition can vary significantly from day to day or even from hour to hour, influencing the burning process and the average calorific value. Such variation requires an accurate prediction to maintain operational parameters and emissions within limits.

Incineration is a versatile technology, applicable to a range of fuels like coal, biomass, and MSW. One of its most compelling advantages, especially in densely populated areas with limited landfills, is its ability to reduce waste volume by approximately 90%, thereby extending the lifespan of landfills [38]. However, challenges arise when facilities are poorly fed or inadequately managed, leading to the emission of concentrated toxins with health risks, such as dioxins/furans and heavy metals, some of which may persist in the residual ash [39]. Furthermore, incineration plants often face public opposition due to air quality and health risks [40]. Such concerns highlight the importance of transparency, public education, and adherence to stringent environmental regulations, as demonstrated by countries like Germany, which have successfully integrated WtE incineration into their MSW management systems [36]. When properly developed and operated, particularly using pre-treated materials such as RDF, incineration can potentially reduce adverse health impacts, making it a viable solution within an MSW management strategy [39].

Gasification converts MSW into syngas, along with liquid and solid byproducts. Unlike incineration, which relies on full combustion, gasification utilizes limited oxygen, allowing for partial rather than complete oxidation of organic material [38]. A controlled environment promotes chemical reactions that break down the MSW into simpler gaseous components, primarily hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4). The operational temperatures for gasification vary depending on the technology. Conventional gasification temperatures range from 700 °C to 1000 °C. In contrast, plasma arc gasification utilizes extremely high temperatures (4000 to 12,000 °C) that break down waste into elemental components, resulting in cleaner syngas and vitrified solid byproducts, which are typically non-leaching and inert. Regardless of the temperature, MSW gasification systems require pre-treatment for size reduction and uniformity, ensuring consistent feeding, efficient heat transfer, and optimal conversion rates. Proper pre-treatment also involves sorting to remove non-combustible materials or to create a more homogeneous feedstock, such as RDF. Syngas can be used to generate electricity through internal combustion engines, gas turbines, or fuel cells, and in chemical synthesis to produce methanol, ethanol, hydrogen, or other chemicals. Gasification also produces byproducts, notably tar and ash [41,42]. Tar is a viscous hydrocarbon mixture that can clog downstream equipment and reduce syngas quality, requiring extensive cleaning. Ash can vary in composition and properties depending on the feedstock and gasification conditions. In plasma gasification, the ash is typically converted into a vitrified, glassy slag, which is safer for disposal and can sometimes be used as a construction material.

Gasification is often considered a more environmentally friendly alternative to traditional incineration. Some of its advantages are (i) cleaner emissions and a cleaner outcome as syngas; (ii) higher efficiency in electrical conversion; (iii) resource recovery and chemical synthesis of other fuels; and (iv) flexibility in feedstock, including a wide variety of MSW, biomass, and organic residues. Some liabilities are (i) capital costs of technology, especially plasma arc systems [23]; (ii) operational complexity and tar management challenges [43]; (iii) social acceptance issues [44]; and (iv) the need for scalable infrastructure for syngas consumption [45].

Pyrolysis is a thermochemical process involved in the thermal decomposition of organic and synthetic materials under anaerobic conditions or in the presence of an inert gas layer (e.g., nitrogen). Operating at temperatures between 300 °C and 800 °C, pyrolysis can process a wide range of feedstocks, including organic waste, biomass, plastics, and synthetic materials such as nylon [38]. Unlike gasification or incineration, pyrolysis entirely excludes oxygen, preventing combustion and breaking down long molecular chains into simpler components. In pyrolysis, pre-treated feedstocks—sorted, dried, and reduced to uniform sizes—are subjected to controlled heating, resulting in thermal decomposition and producing three primary outputs: biochar, bio-oil, and syngas. Temperature, feedstock type, and reactor configuration influence the proportion of output. Lower temperatures generally favor biochar production, while higher temperatures (closer to 800 °C) increase syngas and bio-oil yields [20].

Bio-oil is a dense mixture of complex hydrocarbons, particularly valuable due to its wide-ranging applications in biofuels and feedstock for the chemical industry [20]. Biochar is a versatile product rich in combustible hydrocarbons, applied in energy production to replace fossil coal in industrial processes, and in agriculture as a fertilizer. As a carbon sequestration tool, biochar also aligns with global climate objectives. Finally, syngas is a gaseous byproduct containing CO, H2, and methane, which can be harnessed for energy production [42].

3.3. Biochemical and Chemical Processes Technologies

Biochemical processes use microorganisms to recover energy from MSW as gas or liquid to generate electricity in anaerobic digestion (AD), landfills, fermentation, and microbial fuel cells [11].

In AD, microorganisms decompose biodegradable waste, agricultural residues, and wastewater sludge in anaerobic conditions, resulting in biogas (methane and carbon dioxide). Processes range from mesophilic (30–40 °C) to thermophilic (50–60 °C), with nutrient-rich digestate as a byproduct [46]. Whereas biogas can generate electricity and replace fossil fuels in transportation, digestate serves as a fertilizer for agriculture [42].

Landfills are controlled disposal sites for municipal solid waste (MSW) that require careful site selection, impermeable geological conditions, and the use of geomembranes to prevent leachate infiltration, as well as systems for leachate collection and treatment. During waste decomposition, methane-rich landfill gas is generated, which can be flared or recovered for energy production [47].

In fermentation, microorganisms convert organic sugars such as hexoses and pentoses into ethanol and CO2 under anaerobic conditions [48]. The process can also yield byproducts, such as light calcium carbonate, while modifications in fermentation conditions enable the production of yeast extract, a value-added compound [14].

In microbial fuel cells, organic waste is directly converted into electricity through bacterial activity at the anode. During metabolism, bacteria extract electrons from organic matter, which flow through an external circuit to the cathode, generating electricity with carbon dioxide (CO2) and water as byproducts. However, impurities such as sulfides, chlorides, and particulates in the feed gas limit performance, requiring extensive purification to preserve cell longevity. Although not yet commercially available, microbial fuel cells represent a low-emission alternative for treating organic waste. Their integration with wind and solar systems in hybrid microgrids can enhance overall reliability and efficiency [38].

Chemical treatment via esterification reactions produces biodiesel from oily MSW through an acid and alcohol reaction to form an ester [11]. The primary product is biodiesel, a liquid fuel derived from various feedstocks, including first-generation oils (edible oils), second-generation oils (non-edible oils, such as used cooking oils and animal fats), and third-generation oils from algae biomass [49]. Biodiesel production uses homogeneous, heterogeneous, and enzymatic catalysts. The reaction is consistent: oil plus alcohol yields biodiesel and glycerin [20].

3.4. Technological Choices: Synthesis

Table 3 summarizes the choices of WtE technologies in MSW processes.

Table 3.

Main WtE technological choices for MSW (based on [20]).

Regarding electricity production from MSW, developed nations, such as the USA, Japan, and Germany, exhibit high MSW generation and electricity output, reflecting efficient valorization of waste. In 2020, the USA, Japan, and Germany produced, respectively, 624,700, 144,466, and 127,816 Mtonns/day of MSW, and 2254, 1501 and 1888 MW of electricity production [50]. The conversion rates are, respectively, 277.2, 96.2, and 67.7 Mtonn/day per MW. In contrast, nations such as Brazil [8], Russia [51], and South Africa [52], despite having high MSW volumes (149,096, 100,027, and 53,425 Mtonns/day, in 2020, respectively [50], report no specific WtE electricity figures. Such scarcity potentially reflects data limitations or alternative disposal. Similarly, countries like India and Thailand exhibit comparatively low electricity output (274 and 75 MW in 2020, respectively, [50] and unsatisfactory conversion rates (400 and 526 Mtonnes per day/MW in 2020, respectively), highlighting varying levels of maturity in MSW management.

Among other factors, this divergence can be attributed to the prevalence of advanced WtE technologies and robust pre-treatment in developed nations, critical differences in MSW composition (e.g., high organic fraction that reduces calorific value in developing economies), historical investment disparities in infrastructure, and policy and regulatory frameworks that incentivize WtE. Additionally, challenges like public opposition and inadequate financial mechanisms often hinder WtE solutions in developing contexts, reducing their capacity to recover energy.

4. Driving MSW Management in New Implementations: Policies, Benchmarks, and Advances

This section discusses the challenges of implementing MSW management practices, drawing on previous findings. All cited figures refer to the first half of the 2020s, unless otherwise specified.

MSW open burning emits excessive smoke and particulate matter, resulting in the release of harmful pollutants [53], which pose serious health risks, safety concerns, unsanitary conditions, and other issues [54]. Space constraints and waste composition are also key factors in MSW management strategies [20]. Such challenges are more pronounced in developing countries, where inadequate MSW management practices and large urban and metropolitan areas prevail, including a lack of handling facilities and insufficient collection [2,7,20,55]. MSW may appear near railroad tracks, In Serbia, economic constraints riverbanks, or open spaces [53,54], contributing to (i) breeding of insects, flies, pests, and disease vectors; (ii) greenhouse gas emissions through methane generation; (iii) runoff of putrid leachates; and (iv) public complaints about odor [54].

Reports from low-income countries raise specific concerns. In 2022–2023, about 40% of collected MSW ended up in uncontrolled disposal, which includes open burning, open dumping, and dumping into waterways [56]. In India, only 21% of MSW is properly managed. Challenges include skilled labor shortages for operating WtE plants, limited political commitment, and climate change impacts on MSW quality for anaerobic digestion [57]. China predominantly relies on landfilling, with 52% of MSW being landfilled, 45% incinerated, and 3% composted in 2018, despite its vast land availability [14,19]. Similarly, the USA sends 53% of its MSW to landfills and allocates 13% for energy recovery. South Africa and India both face political and knowledge gaps that delay WtE progress, emphasizing the need for robust public policies and regulations aligned with technological advancements [20,58]. In Colombia, insufficient capital investment pushes MSW disposal toward landfills instead of other WtE technologies [59]. Similarly, South Africa prioritizes coal-fired power plants due to abundant, low-cost coal reserves projected to last 200 years, coupled with the absence of tax credits and low landfill taxes, which further deter WtE investments [52,60]. Globally, WtE implementation faces high costs for installation, operation, maintenance, and transportation infrastructure, forcing nations with limited budgets to adopt cheaper but suboptimal options [57,61,62]. In Serbia, economic constraints and weak pollution management policies lead to continued landfilling of MSW [28]. However, significant operational challenges persist, such as incineration that, although viable, generates chlorine and toxic byproducts, such as dioxins, furans, and heavy metals, which pose health risks when poorly managed. Residual ash often contains such harmful substances [39,63].

Regarding operational challenges, incinerators often face public opposition; however, when well-operated and utilizing RDF, they can reduce adverse health impacts, including carcinogenic risks [39,40]. Biomass gasification struggles with operational issues such as tar formation, which can block systems and limit application [43]. Inadequate disposal remains a major environmental challenge in many countries. Although incineration has been increasingly adopted, less stringent emission regulations, such as those in Brazil compared to the EU and the US, raise concerns about potential public health impacts [8]. Pyrolysis also faces social acceptance issues due to limited public understanding of its raw materials, costs, environmental impacts, and derived products [44]. Landfill challenges, including leachate leaks, poor gas collection systems, and pressure from organizations benefiting from landfill expansion, persist due to misinformation, weak legislation, insufficient resources, and inadequate infrastructure [2,6,7,55]. WtE adoption in public–private partnerships (PPP) is hindered by inadequate infrastructure, unlicensed MSW disposal, environmental risks, supply issues, cost overruns, and corruption [2,64]. Developing countries also struggle with outdated collection systems, ineffective legislation, a lack of inclusivity, and limited prioritization of MSW issues [1].

4.1. Suggestions and Benchmarks

Previously highlighted challenges provide lessons, identify benchmarks, and suggest solutions to new implementations of WtE technologies in MSW management. For example, Japan directs 78% of MSW to WtE plants, with the remaining 22% routed for recycling and composting, serving as a benchmark for other markets [55].

One lesson concerns pre-treatment of MSW before incineration, such as torrefaction, shredding, and size reduction, which increases the calorific value and reduces pollution [55]. In incinerators, high-temperature combustion, combined with high-efficiency end-of-pipe treatment and a real-time monitoring system, along with public consultation, is an important recommendation [40].

Another lesson involves understanding the characteristics of MSW. In Germany, approximately 103 kg of packaging is produced annually per person, with 25% comprising plastic. Implemented measures include efforts to reduce unnecessary products and packaging, replacing plastic materials, banning disposable and non-essential plastic items, integrating product responsibility into cleanup campaigns, eliminating the use of microplastics in cosmetics, promoting reusable and multi-purpose products as alternatives to single-use items, and introducing initiatives to prevent disposable packaging [36]. A necessary step is also the adoption of returnable packaging [65]. The “polluter pays principle” ensures that those who generate waste are held responsible for its recycling, treatment, and environmentally sound disposal. In Germany, industries are legally required to take responsibility for reusing and recycling the packaging materials they produce and distribute [36]. In China, policies focus on (i) waste reduction, (ii) waste separation, and (iii) waste utilization through energy recovery. In 2018, China introduced a policy emphasizing that waste producers should be held accountable for the waste they generate. By 2020, the country had banned non-degradable plastic products, including plastic bags, disposable plastics, and packaging materials [36]. This approach not only reduces the volume of waste but also minimizes the variability in MSW composition [66].

One benchmark is Germany’s MSW management system, based on advanced recycling and thermal treatment through MSW incineration. It operates one of the few systems worldwide that completely avoids landfilling of untreated MSW, with 67% of MSW recycled in 2020. In the 1970s, Germany introduced legislation to promote biomass biofuel facilities, paving the way for significant growth in biogas infrastructure. The number of biogas plants increased from just 100 in 1991 to 11,000 in 2021. This expansion was further supported by the 1991 feed-in tariff legislation (StrEG), which provided financial returns for investments made by biogas plant operators [25]. These outcomes can be largely attributed to early developments in the 1980s, when the first challenges related to the disposal of untreated MSW emerged [36]. Driven by the sharp increase in MSW volumes, limited land availability, and escalating environmental issues such as climate-damaging methane emissions and polluted leachate, the number of landfills has significantly dropped from 65,000 in 1970 to 1100 in 2015 [36]. In summary, the complexity of MSW management requires not only technical solutions but also a thorough review of legislation [8].

Developed metropolitan regions such as Berlin, Tokyo, and Singapore have taken actions such as separation and collection at the source, closed-loop MSW management, basic law for the development of circular economy, management following the MSW hierarchy, conversion into energy, fuel, and materials such as road pavement, biochar, cement, solvent, ceramics [14]. An example of this paradigmatic shift is viewing MSW as a resource, rather than waste [7].

In contrast, in developing countries, Pakistan developed landfills equipped with leachate collection, biogas recovery, and coverage [67]. Bangladesh is also adopting AD for energy generation through MSW, using most of the MSW generated [9]. India also serves as a key benchmark, due to its mass awareness programs and initiatives, such as the ban on single-use plastics and the polluter pays principle. These efforts emphasize the dissemination of improved information, free education, assertive communication, the promotion of waste-to-energy (WtE) technologies, financial incentives such as subsidies and discounts, and streamlined incentive processes to enhance municipal solid waste (MSW) management [66].

While benchmarks from Germany and Japan offer insights into effective WtE strategies, their direct transferability to developing economies requires consideration. Strict regulatory frameworks, robust public engagement, and advanced infrastructural development often represent significant barriers for immediate replication in resource-constrained environments. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on adapting these lessons—focusing on incremental policy development, tailored technological solutions, and context-specific public education—rather than direct transplantation, to ensure sustainable implementation.

4.2. Advances and Opportunities for Implementations

Building upon the identified challenges, this section outlines how strategic advances and opportunities can mitigate issues for new implementations. For instance, specific incentive policies, such as feed-in tariffs and tax exemptions, can address the high capital costs, making WtE projects economically viable where conventional financing is a barrier.

The approach adopted by China is to expand the range of circular economy (CE) activities and implement a comprehensive policy. The emphasis lies on new business models, the industrial symbiosis of cities through the application of material flow analysis, and the reduction of CO2 emissions [68]. A study in Bangladesh highlights the renewable electricity production policy based on WtE according to the country’s climate, using mixed incineration of MSW [69]. Another study highlights the case of Colombia, which created reimbursement policies, i.e., refund of taxes paid by WtE-based plants [59]. Incentive policies, such as feed-in tariffs (FIT), carbon reduction credits, and tax exemptions, can stimulate large-scale AD applications [70]. Studies in Turkey, Brazil, and Germany suggest that plasma arc gasification and advanced incineration stand out in WtE, provided there are funds to build and operate such facilities [23].

In the particular case of developing nations, they should employ approaches such as anaerobic digestion (AD) of organic waste, incineration, pyrolysis, and gasification for specific MSW types, including plastics, tires, and electronic waste, alongside inert waste landfilling [10]. An alternative path involves processing inert waste for use in civil construction [36]. Japan’s food industry processes approximately 85% of its food waste into animal feed, fertilizer, or methane [68]. These practices underscore the importance of education in cultivating responsible citizenship, enabling individuals to perceive MSW as a valuable resource [36]. For example, India’s government promotes environmental education to transform perceptions of MSW, which concurrently fosters employment opportunities [71].

Governments should educate consumers through recycling and sorting initiatives [72], supported by incentives to enhance segregation and minimize material and energy losses [71,73]. Technological advances, such as autonomous robotic systems, enable efficient MSW recycling through automated sorting [72]. Torrefaction enhances the quality of MSW solid fuel [49]. Cutting-edge plastic waste technologies, including hydrocracking, chemolysis, and methanolysis, convert waste into smaller molecules and monomers [74]. Mathematical software addresses MSW gasification challenges, boosting energy output and cutting emissions for viable systems [75]. Advancing WtE systems demands innovation and political support [38].

In India, digital infrastructure and IoT have advanced smart transportation, waste management, and telecare. IoT solutions, such as Wi-Fi, city surveillance, and solar-powered trash bins, notify authorities when they are full, thereby enhancing public engagement and policy integration [76]. Combining RDF plants with gasification provides optimal MSW solutions [77]. Dolomite aids in gasification and incineration by removing tar and enhancing hydrogen production through catalytic cracking [43]. Efficient source sorting enhances the calorific value of incinerated waste [27], a process supported by AI and IoT in modern incineration plants [78].

In South Africa, MSW disposal fees, coupled with awareness campaigns, encourage assertive treatment practices. For instance, the 2016 disposal fee in Cape Town was 395 ZAR per tonne (equivalent to £17.55), compared to the United Kingdom’s £84.40, illustrating the economic viability of landfill disposal [52]. Finally, the pay-as-you-throw system, combined with WtE technologies, presents a sustainable solution for MSW management [79]. Rising MSW generation underscores the urgency of achieving zero per capita growth [63]. This shift requires industries to address key challenges in transitioning to a circular economy, including (i) technological compatibility, (ii) system integration, (iii) cost recovery, (iv) policy consistency, and (v) safety protocols [36].

5. Conclusions

The research question this article aimed to address was: How can MSW management be optimized through the implementation of new WtE? The answer involves a comprehensive approach that combines technological advancements, policy reforms, and public engagement. Inefficient practices, such as open dumping and burning, should be regulated to limit their impact. Benchmarks highlighting successful strategies should be considered, mainly from countries such as Germany and Japan. Such benchmarks include rigorous regulatory frameworks, pre-treatment of MSW, and advanced WtE technologies like incineration and anaerobic digestion, supported by policies such as feed-in tariffs and carbon credits. In the particular case of developing countries, due to limited infrastructure and financial constraints, simply replicating is often unfeasible. Instead, incremental and customized solutions, such as community education on waste segregation, digital tools for waste management, and incentivized recycling programs, are necessary for sustainable progression. Ultimately, viewing MSW as a resource rather than waste plays an important role, with circular economy principles supporting long-term efficiency in WtE implementation.

This research analyzed documents from WoS, Scopus, and ScienceDirect over seven years. Extending the analysis to longer periods and applying findings across countries could enhance MSW valorization strategies. Policymaking in resource-intensive sectors like MSW management benefits from empirical data and models that simulate scenarios, predict outcomes, and optimize implementation. Key approaches include (i) life cycle assessment (LCA) [80], (ii) cost–benefit and techno-economic evaluations [81], (iii) system dynamics models [82], (iv) MSW volume and mix forecasting [83], and (v) optimization of routes and facility locations [84]. Key performance indicators include GHG emission reductions, landfill diversion, resource recovery, job creation, energy surplus, health improvements, and public engagement [85]. Transparency tools should include audits, certifications, and public reporting [86].

Future research should utilize data from private and governmental organizations to evaluate WtE performance and community engagement in developing nations. Longitudinal studies are necessary to evaluate the environmental, economic, and social impacts, taking into account changes in waste composition and policies. Key focuses include techno-economic evaluations, social acceptance, and policy frameworks with incentives, as well as innovative public–private partnerships. Additionally, studies on educational initiatives and community engagement strategies to promote source segregation and public acceptance are crucial for the sustained success of MSW valorization in rapidly urbanizing regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.d.L. and M.A.S.; methodology, M.S.d.L., A.G.F. and M.A.S.; investigation, M.S.d.L., A.G.F. and N.K.J.; validation, A.G.F.; data curation, A.G.F. and N.K.J.; visualization, A.G.F. and N.K.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.d.L., A.G.F. and M.A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A.S.; supervision, N.K.J.; project administration, M.A.S.; funding acquisition, M.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CNPq, grant number 303496/2022-3.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024—Beyond an age of waste: Turning rubbish into a resource. In Global Waste Management Outlook 2024—Beyond an Age of Waste: Turning Rubbish into a Resource; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malav, L.; Yadav, K.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, G.; Krishnan, S.; Rezania, S.; Kamyab, H.; Pham, Q.; Yadav, S.; et al. A review on municipal solid waste as a renewable source for waste-to-energy project in India: Current practices, challenges, and future opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarichi, L.; Jutidamrongphan, W.; Techato, K. The evolution of waste-to-energy incineration: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, G.; Facchini, F.; Ranieri, L.; Starace, G.; Vitti, M. Assessment of carbon emissions’ effects on the investments in conventional and innovative waste-to-energy treatments. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Motola, V.; Dallemand, J.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Mofor, L. Evaluation of energy potential of Municipal Solid Waste from African urban areas. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1269–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisi, Y.; Matos, F.; Carneiro, M. Development of waste-to-energy through integrated sustainable waste management: The case of ABREN WtERT Brazil towards changing status quo in Brazil. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2023, 5, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, R.; Shetty, N.; Thimmappa, B. A review of the current situation of municipal solid waste management in India and its potential for anaerobic digestion. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 69, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadario, N.; Gabriel Filho, L.; Cremasco, C.; Santos, F.; Rizk, M.; Mollo Neto, M. Waste-to-Energy Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste: Global Scenario and Prospects of Mass Burning Technology in Brazil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Ahmed, M.; Aziz, M.; Beg, M.; Hoque, M. Municipal solid waste management and waste-to-energy potential from Rajshahi City Corporation in Bangladesh. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Samadder, S. A review on technological options of waste to energy for effective management of municipal solid waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Jia, D.; Evrendilek, F.; Liu, J. Pyrolytic Valorization of Polygonum multiflorum Residues: Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Product Distribution Analyses. Processes 2025, 13, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Kabir, Z. Waste-to-energy generation technologies and the developing economies: A multi-criteria analysis for sustainability assessment. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Gasification of municipal solid waste (MSW) as a cleaner final disposal route: A mini-review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.W.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, J.; Shao, Z.; Iris, Ç.; Pan, B.; Li, X.; et al. A review of China’s municipal solid waste (MSW) and comparison with international regions: Management and technologies in treatment and resource utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, C.; Zhang, C.; Xia, B.; Chen, Q.; Skitmore, M. Effects of economic compensation on public acceptance of waste-to-energy incineration projects: An attribution theory perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1515–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Xia, B.; Liu, S.; Skitmore, M. Identification of Risk Factors Affecting PPP Waste-to-Energy Incineration Projects in China: A Multiple Case Study. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4983523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Adams, M.; Cote, R.; Geng, Y.; Li, Y. Comparative study on the pathways of industrial parks towards sustainable development between China and Canada. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Singh, D.; Shukla, S.K. Changing scenario of municipal solid waste management in Kanpur city, India. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2022, 24, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Denney, J.; Mbonimpa, E.; Slagley, J.; Bhowmik, R. A review on municipal solid waste-to-energy trends in the USA. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Chowdhury, S.; Techato, K. Waste to Energy in Developing Countries—A Rapid Review: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policies in Selected Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabalane, P.; Oboirien, B.; Sadiku, E.; Masukume, M. A Techno-economic Analysis of Anaerobic Digestion and Gasification Hybrid System: Energy Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste in South Africa. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Fandiño, J.; Eras, J. Alternatives of municipal solid wastes to energy for sustainable development. The case of Barranquilla (Colombia). Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 1809–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firtina-Ertis, I.; Ayvaz-Cavdaroglu, N.; Coban, A. An optimization-based analysis of waste-to-energy options for different income level countries. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 10794–10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiwada, D.; Golzar, F.; Mainali, B.; Devendran, A. Circularity in the Management of Municipal Solid Waste—A Systematic Review. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2021, 25, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabie, C. Converting municipal waste to energy through the biomass chain, a key technology for environmental issues in (Smart) cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liew, R.; Tamothran, A.; Foong, S.; Yek, P.; Chia, P.; Van Tran, T.; Peng, W.; Lam, S. Gasification of refuse-derived fuel from municipal solid waste for energy production: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2127–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatova, A.; Abu-Qdais, H. Using multi-criteria decision analysis to select waste to energy technology for a Megacity: The case of Moscow. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepić, Z.; Bošković, G.; Ubavin, D.; Batinić, B. Waste-to-Energy in Transition Countries: Case Study of Belgrade (Serbia). Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 4579–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Nobre, C.; Brito, P.; Gonçalves, M. Brief Overview of Refuse-Derived Fuel Production and Energetic Valorization: Applied Technology and Main Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ddiba, D.; Andersson, K.; Rosemarin, A.; Schulte-Herbrüggen, H.; Dickin, S. The circular economy potential of urban organic waste streams in low-and middle-income countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 1116–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, S.; Butturi, M.A.; Rimini, B.; Gamberini, R.; Sellitto, M.A. Estimating the circularity performance of an emerging industrial symbiosis network: The case of recycled plastic fibers in reinforced concrete. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Almeida, F. Strategies for value recovery from industrial waste: Case studies of six industries from Brazil. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Rouboa, A. Life cycle thinking of plasma gasification as a waste-to-energy tool: Review on environmental, economic and social aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfilar, R.; Bagheri, M.; Golestani, B. Technoeconomic feasibility review of hybrid waste to energy system in the campus: A case study for the University of Victoria. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Meyer, B.; Huang, Q.; Voss, R. Sustainable waste management for zero waste cities in China: Potential, challenges and opportunities. Clean Energy 2020, 4, 169–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Chen, Y.; Su, P. Artificial intelligence technique development for energy-efficient waste-to-energy: A case study of an incineration plant. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.; Binyet, E.; Nugroho, R.; Wang, W.; Srinophakun, P.; Chein, R.; Demafelis, R.; Chiarasumran, N.; Saputro, H.; Alhikami, A.; et al. Toward sustainability of Waste-to-Energy: An overview. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole-Hunter, T.; Johnston, F.; Marks, G.; Morawska, L.; Morgan, G.; Overs, M.; Porta-Cubas, A.; Cowie, C. The health impacts of waste-to-energy emissions: A systematic review of the literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senpong, C.; Wiwattanadate, D. Sustainable Energy Transition in Thailand: Drivers, Barriers and Challenges of Waste-to-Energy at Krabi Province. Appl. Environ. Res. 2022, 44, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaré, A.; González, S.; Faceli, K.; Casadei, V. Technologies and decision support systems to aid solid-waste management: A systematic review. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.C.; Schulze-Netzer, C.; Korpås, M. Current and emerging waste-to-energy technologies: A comparative study with multi-criteria decision analysis. Smart Energy 2024, 16, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjani, S. Efficient removal of tar employing dolomite catalyst in gasification: Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 836, 155721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Khatun, M.; Arefin, M.; Islam, M.; Hassan, M. Waste to energy: An experimental study of utilizing the agricultural residue, MSW, and e-waste available in Bangladesh for pyrolysis conversion. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, M.; Fei, Q.; Guo, S.; Yang, N.; Guan, X.; Hu, P. Biomass gasification as a scalable, green route to combined heat and power (CHP) and synthesis gas for materials: A review. Fuels 2024, 5, 625–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Godina, R.; Azevedo, S.; Matias, J. Current status, emerging challenges, and future prospects of industrial symbiosis in Portugal. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.; Khan, M.; Nasser, M.; Al-Saad, K.; Heng, O. Recent advances and applications of municipal solid waste bottom and fly ashes: Insights into sustainable management and conservation of resources. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Szabó, M.; Ceci, P.; Avino, P. Biomass Energy and Biofuels: Perspective, Potentials, and Challenges in the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisbona, P.; Pascual, S.; Pérez, V. Waste to energy: Trends and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 14, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundariya, N.; Mohanty, S.; Varjani, S.; Ngo, H.; Wong, J.; Taherzadeh, M.; Chang, J.S.; Ng, H.; Kim, S.; Bui, X. A review on integrated approaches for municipal solid waste for environmental and economical relevance: Monitoring tools, technologies, and strategic innovations. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 342, 125982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wünsch, C.; Tsybina, A. Municipal solid waste management in Russia: Potentials of climate change mitigation. International J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, O.; Akinlabi, S.; Jen, T.; Dunmade, I. Sustainable utilization of energy from waste: A review of potentials and challenges of Waste-to-energy in South Africa. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Shahid, S.; Nawaz, M.; Mustafa, J.; Iftekhar, S.; Ahmed, I.; Tabraiz, S.; Bontempi, E.; Assad, M.; Ghafoor, F.; et al. Waste to energy feasibility, challenges, and perspective in municipal solid waste incineration and implementation: A case study for Pakistan. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 18, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Berruti, F. Municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1433–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Alam, S.; Bin-Masud, R.; Prantika, T.; Pervez, M.; Islam, M.; Naddeo, V. A Review on Characteristics, Techniques, and Waste-to-Energy Aspects of Municipal Solid Waste Management: Bangladesh Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Paul, J.; Ramola, A.; Silva Filho, C. Unlocking the significant worldwide potential of better waste and resource management for climate mitigation: With particular focus on the Global South. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, H.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. A review on organic waste to energy systems in India. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Awwad, F.; Khan, M.; Ismail, E. Sustainable energy recovery from municipal solid wastes: An in-depth analysis of waste-to-energy technologies and their environmental implications in India. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 43, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marefat, A.; Golzary, A.; Takahashi, F.; Huisingh, D. Financial feasibility and optimization of anaerobic digestion systems for sustainable waste management: A comprehensive global analysis. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 19, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbazima, S.; Masekameni, M.; Mmereki, D. Waste-to-energy in a developing country: The state of landfill gas to energy in the Republic of South Africa. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2022, 40, 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Przybysz, A.; Piekarski, C. Location as a key factor for waste to energy plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istrate, I.; Iribarren, D.; Gálvez-Martos, J.; Dufour, J. Review of life-cycle environmental consequences of waste-to-energy solutions on the municipal solid waste management system. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wenga, T.; Frandsen, F.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. The fate of chlorine during MSW incineration: Vaporization, transformation, deposition, corrosion and remedies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 76, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, N.; El-Dash, K.; Attia, T.; Dokhan, S. Toward sustainable waste-to-energy solutions: Risk allocation and technological innovations in public-private partnerships. HBRC J. 2024, 20, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlmaier, D.; Sellitto, M. Returnable packaging for transportation of manufactured goods: A case study in reverse logistics. Production 2007, 17, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Kumari, S.; Borker, S.; Prashant, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R. Solid Waste Management in Indian Himalayan Region: Current Scenario, Resource Recovery, and Way Forward for Sustainable Development. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 609229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korai, M.; Ali, M.; Lei, C.; Mahar, R.; Yue, D. Comparison of MSW management practices in Pakistan and China. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020, 22, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelić, D.; Markić, D.; Prokić, D.; Malinović, B.; Panić, A. “Waste to energy” as a driver towards a sustainable and circular energy future for the Balkan countries. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, C.; Kumar, A.; Rani, P. Municipal solid waste management: A review of waste to energy (WtE) approaches. BioResources 2021, 16, 4275–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Abuzar, M.; Amin, F.; Liu, G.; Chen, C. PEST (political, environmental, social-technical) analysis of the development of the waste-to-energy anaerobic digestion industry in China as a representative for developing countries. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujara, Y.; Pathak, P.; Sharma, A.; Govani, J. Review on Indian Municipal Solid Waste Management practices for reduction of environmental impacts to achieve sustainable development goals. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.; Farghali, M.; Rooney, D.; Yap, P. Recycling municipal, agricultural and industrial waste into energy, fertilizers, food and construction materials, and economic feasibility: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 765–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shovon, S.; Akash, F.; Rahman, W.; Rahman, M.; Chakraborty, P.; Hossain, H.; Monir, M.U. Strategies of managing solid waste and energy recovery for a developing country—A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e08530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.; Masuk, N.; Safayet, R.; Nguyen, H.; Mourshed, M. Plastic Waste: Challenges and Opportunities to Mitigate Pollution and Effective Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanthakett, A.; Arif, M.; Khan, M.; Oo, A. Performance assessment of gasification reactors for sustainable management of municipal solid waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 291, 112661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, M.; Singh, S. Tackling municipal solid waste crisis in India: Insights into cutting-edge technologies and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Soren, N. An overview of municipal solid waste-to-energy application in Indian scenario. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Lee, J.; Son, J.; Yun, Y.; Song, Y.; Song, J. Intelligent Combustion Control in Waste-to-Energy Facilities: Enhancing Efficiency and Reducing Emissions Using AI and IoT. Energies 2024, 17, 4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvestani, M.; Sisani, F.; Ebrahimzadehsarvestani, E.; Di Maria, F. Evaluating Methanol and Liquid CO2 Recovery from Waste-to-Energy Facilities: A Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 319, 118921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubi, O.; Morse, S.; Murphy, R.J. Electricity generation from municipal solid waste in Nigeria: A prospective LCA study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Mijangos, R.; De Andrés, A.; Guerrero-Garcia-Rojas, H.; Seguí-Amórtegui, L. A methodology for the technical-economic analysis of municipal solid waste systems based on social cost-benefit analysis with a valuation of externalities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 18807–18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafew, S.; Rafizul, I. Application of system dynamics model for municipal solid waste management in Khulna city of Bangladesh. Waste Manag. 2021, 129, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, F.; Kamalan, H.; Sarraf, A. Predicting solid waste generation based on the ensemble artificial intelligence models under uncertainty analysis. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, C.; Moraes, J.; Fava, L.; Furtado, J.; Machado, E.; Rodrigues, A.; Sellitto, M. Optimizing routes of municipal waste collection: An application algorithm. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2024, 35, 965–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaz, H.; Artacho-Ramírez, M.; Cloquell-Ballester, V.A.; Catalán, C. Prioritizing action plans to save resources and better achieve municipal solid waste management KPIs: An urban case study. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2023, 73, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersico, L.; Aureli, S.; Foschi, E. Exploring the role of digital platforms in promoting value co-creation: Evidence from the Italian municipal solid waste management system. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).