Abstract

This paper presents a self-contained startup charging circuit designed for energy-harvesting batteryless IoT devices. The proposed circuit consists of a current-biasing block, a current mirror, a reference voltage generator, and a comparator circuit. The current-biasing circuit drives the current mirror, which supplies the charging current to the energy storage element. Simultaneously, the reference voltage generator—also biased by the current source—produces a stable DC reference voltage. When the energy storage device (e.g., a supercapacitor) lacks sufficient charge, the comparator enables the charging path by activating the current-biasing and mirror circuits. Once adequate energy is stored, the comparator disables these circuits to prevent overcharging. This self-contained solution is intended to autonomously initialize and manage the cold-start charging process in energy-harvesting systems without relying on external controllers. This paper highlights the circuit architecture and validated performance, demonstrating a charging current of up to 27 mA, a reference voltage of 700 mV, and an operating range from 0.9 V to 1.8 V across a temperature range of −40 °C to 85 °C.

1. Introduction

In batteryless Internet of Things (IoT) devices, energy-harvesting systems rely heavily on supercapacitors as energy storage elements due to their high power density, rapid charging capability, and long cycle life [1,2,3,4]. However, efficiently charging supercapacitors, especially under cold-start conditions when the device has no pre-existing energy, remains a significant design challenge. To address this, several previous works have proposed low-power and cold-start charging circuits for various types of energy harvesters [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Energy harvesting itself is essential for batteryless IoT devices, where ambient sources such as RF, thermal, and mechanical vibrations are converted into usable electrical energy [11,12,13].

The charging circuit must operate reliably with low input power, avoid the need for external controllers, and ensure seamless startup across varying environmental conditions. Moreover, the charging circuit plays a critical role in the entire system’s operation; it determines how quickly and efficiently the IoT node can become active, respond to sensed data, and maintain energy autonomy [14,15,16,17]. Any inefficiency or dependence on external control can compromise system performance, especially in intermittent or unpredictable energy environments. Therefore, developing a robust and efficient charging circuit that is self-starting and self-contained is essential to enabling practical and scalable deployment of batteryless IoT solutions.

In most existing designs, the charging circuit requires an external current source and reference voltage to operate effectively [18]. This paper presents a self-contained charging circuit with internal means for generating both the bias current and reference voltage. This design eliminates the need for external control elements, enabling autonomous startup and improving energy efficiency for batteryless IoT applications.

This paper [19,20,21,22,23] discloses a device with an external nano-watt bandgap voltage reference circuit with a six-stage PTAT voltage generator, where the stages, each equipped with a differential pair and current mirror, are cascaded in such a way that produces sufficient positive temperature coefficients. The disclosure also provides a separate nano-ampere current reference circuit that serves as the current source for the charging circuit. Crucially, such use of an external current source and a voltage reference circuit results in a complex circuit design that requires a substantial physical area when manufactured.

The works presented in [24,25] describe a startup circuit that (i) forces an arbitrary bias-generating circuit into a steady-current state during startup by conducting charging current from an external current source and (ii) disconnects the external source afterward using switching means. When such an approach is adapted to charging circuits for energy storage devices, it inherits key design limitations, most notably, the dependence on an external current source.

In contrast, the circuit proposed in this work is self-contained, integrating all essential functions—biasing, voltage reference generation, and switching control—into a single autonomous block. This design simplifies system integration and enables reliable cold-start operation in batteryless IoT systems. The objective of this paper is to address and overcome the limitations of previous approaches by eliminating the need for external control elements.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the design and architecture of the proposed self-contained charging circuit. Section 3 discusses the simulation results, including corner and Monte Carlo analyses, validating the circuit’s performance under various operating conditions. Section 4 details the post-simulation evaluation and actual chip measurement results. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper by summarizing the key contributions and highlighting the advantages of the proposed design for energy-harvesting applications.

2. Proposed Charging Circuit

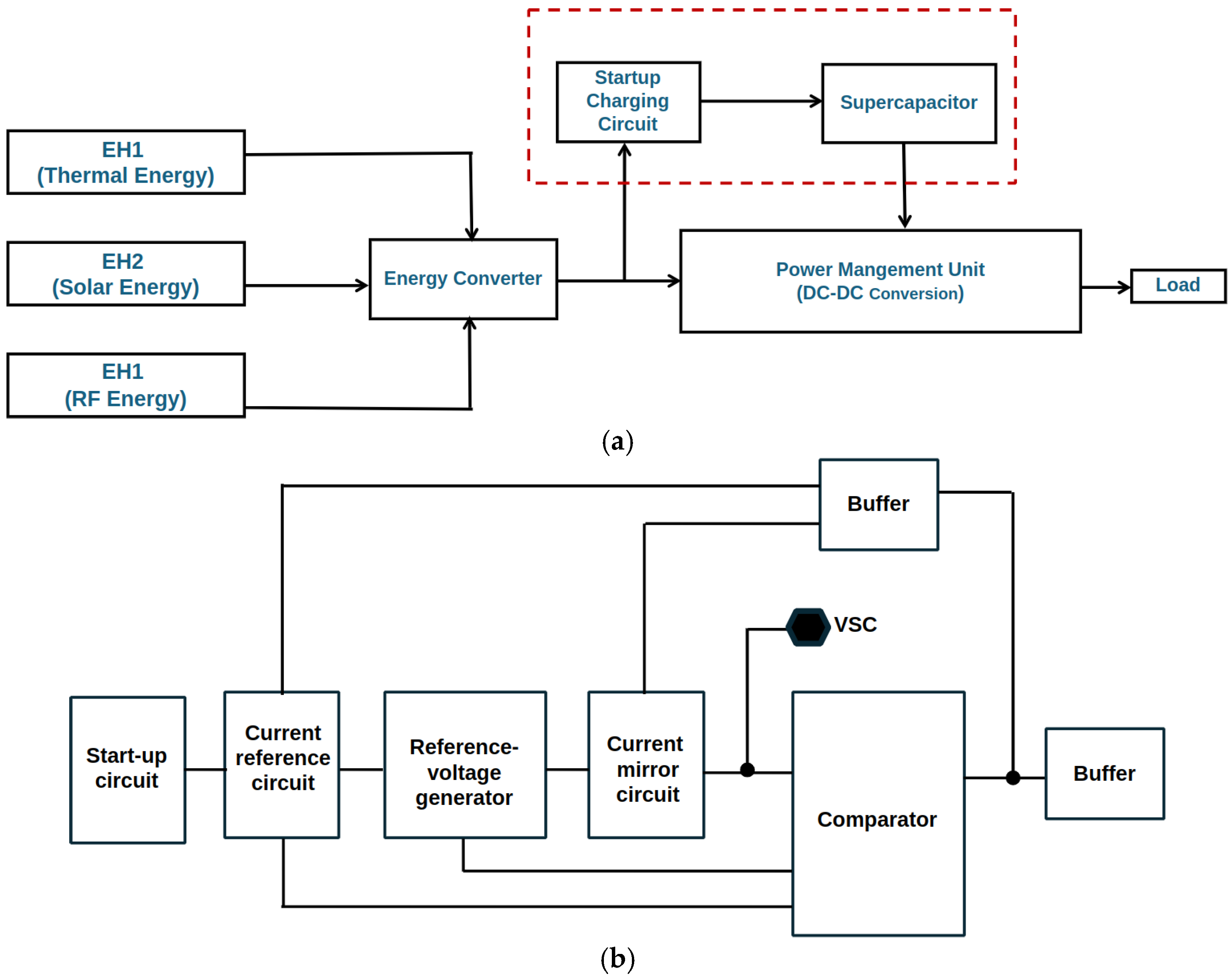

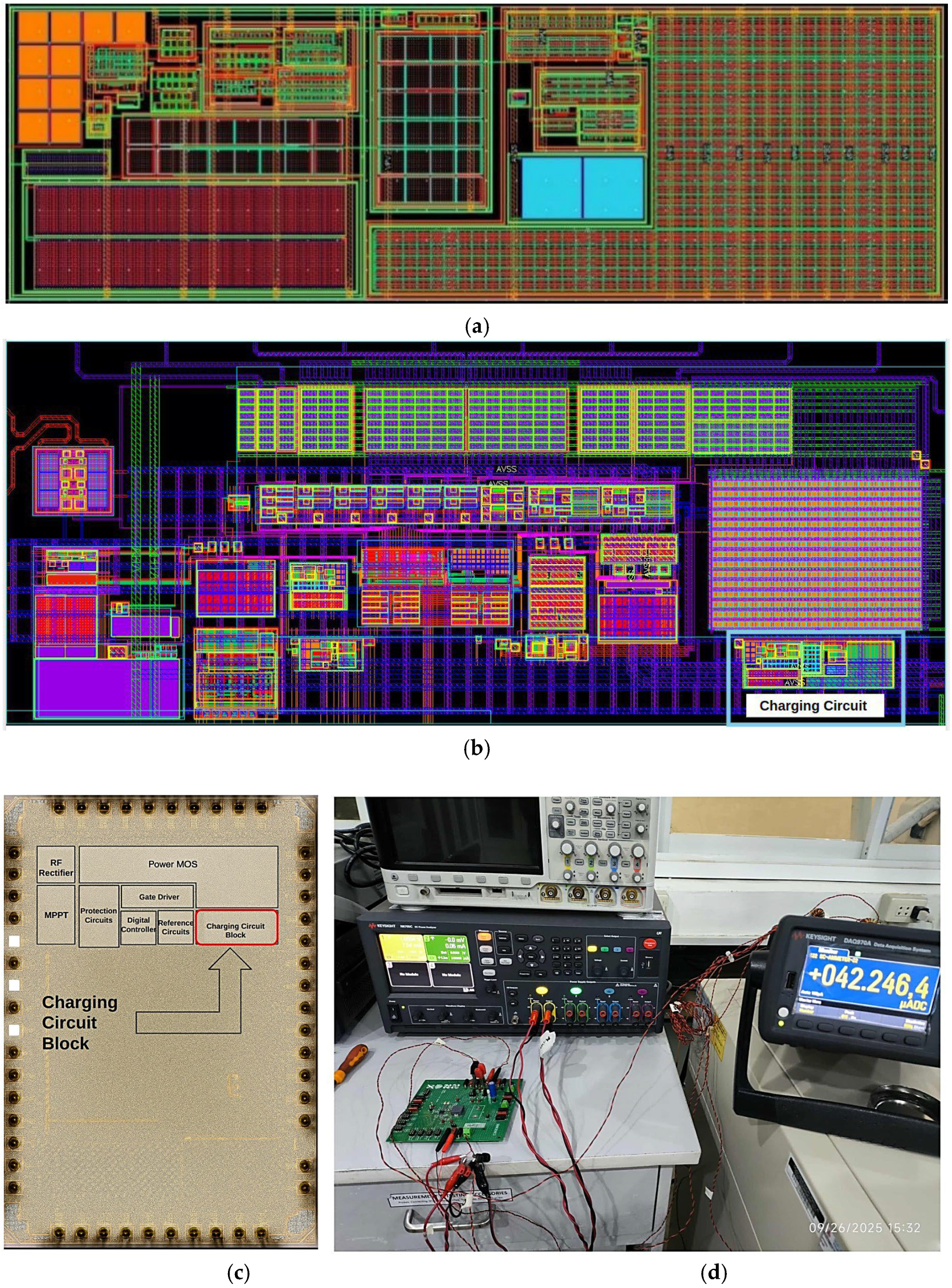

Figure 1 illustrates the role and architecture of the proposed self-contained charging circuit within an energy-harvesting system. Figure 1a shows a system-level diagram where multiple energy sources (thermal, solar, and RF) are funneled through an energy converter to power a load. The proposed startup charging circuit is used to charge a supercapacitor, providing a reliable energy buffer for cold-start conditions [5].

Figure 1.

(a) System-level diagram of an energy-harvesting application incorporating the proposed startup charging circuit to charge a supercapacitor [5]. (b) Block diagram of the proposed self-contained charging circuit, showing its main functional components, including the startup circuit, internal biasing, reference generation, current mirror, comparator, and output buffer.

Figure 1b presents the internal block diagram of the proposed charging circuit. Unlike conventional designs, this implementation integrates all critical functions—a startup circuit, current biasing, reference voltage generation, a current mirror, a comparator, and an output buffer—into a single autonomous module. This self-contained architecture enables reliable cold-start operation without the need for external biasing or reference inputs, thereby enhancing integration and suitability for batteryless IoT applications.

Previous startup charging circuits, such as those presented in [19], typically rely on external components, such as a high-voltage pump (Vpump), a fixed reference voltage (Vref), and external bias sources to enable operation. These dependencies pose critical limitations in energy-harvesting applications, particularly during cold-start conditions where no external energy sources are guaranteed at startup.

In contrast, the circuit proposed in this work is fully self-contained, integrating internal current biasing, voltage reference generation, and comparator control into a single autonomous block. This architecture eliminates the need for any external startup assistance, thereby enabling reliable cold-start operation and simplifying system integration in batteryless IoT devices. The self-contained design directly addresses the key challenges of energy-autonomous systems by ensuring that all essential charging functions are internally generated and managed.

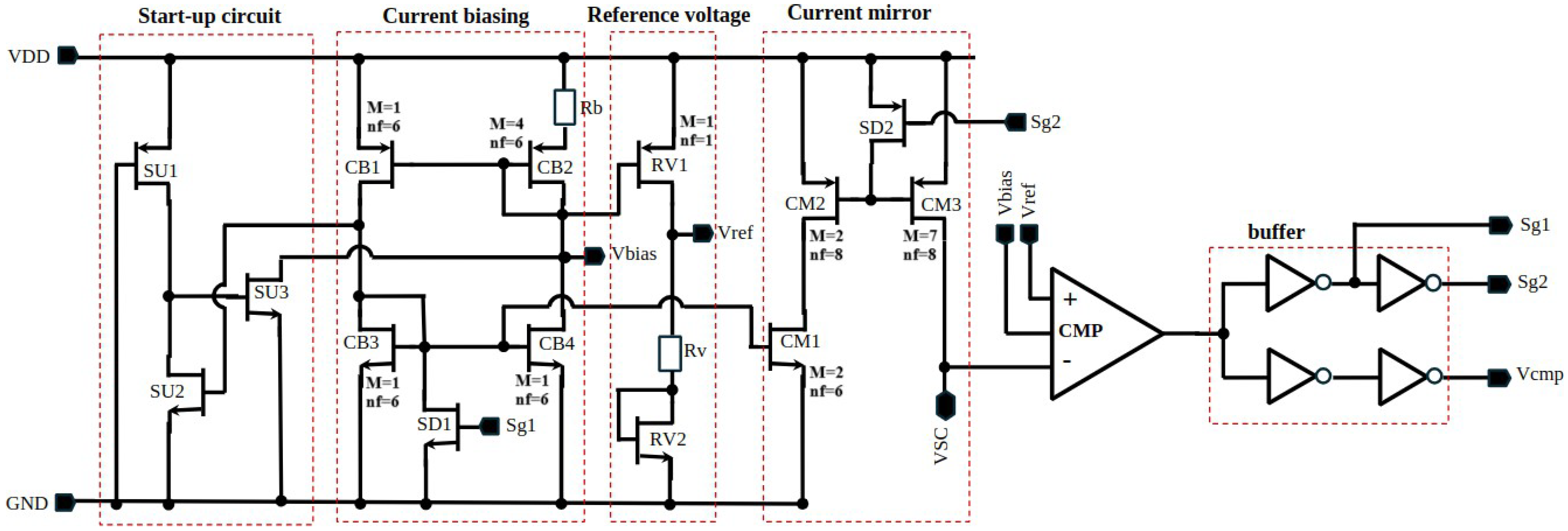

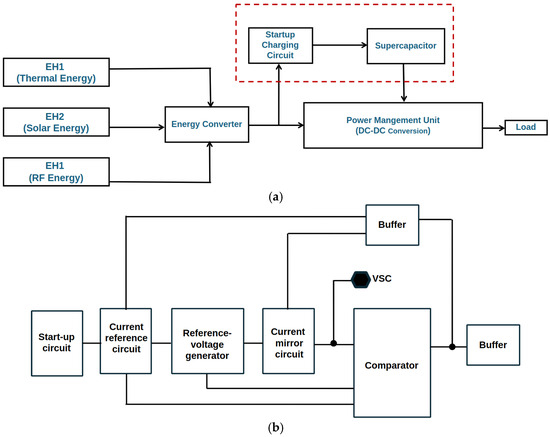

Figure 2 shows the simplified schematic of the proposed charging circuit. The start-up circuit transistors are labeled as SU1, SU2, and SU3, which provide the initial bias to the current-biasing circuit through the gate of SU2 and the drain of SU3. The current-biasing circuit generates the current reference for the entire block. The fixed DC reference voltage generated at the reference voltage is fed to the comparator circuit.

Figure 2.

The proposed self-contained charging circuit for energy-harvesting batteryless IoT devices.

Resistor Rv and transistor RV2 are configured to serve as PTAT and CTAT generators, respectively, such that the voltage Vref is temperature-insensitive. Rv and RV2 are scaled in size and parameters so that their linear temperature coefficients are equal in magnitude and opposite in sign. Such a configuration of the reference voltage generator enables the charging circuit of this paper to forego other components (such as a six-stage PTAT voltage generator, as in the prior work) and, consequently, minimize the layout area.

The current mirror circuit receives current from the current-biasing circuit through CM1, mirrors to CM3, and generates a charging current at the VSC terminal. Under normal operation, the current-biasing circuit generates a constant current, which translates to a bias voltage at Vbias. Transistor CM1 then mirrors the drain current at CB3 through Vbias. Similarly, the drain current at CM1 is mirrored to CM2 and CM3.

When charging the energy storage device, the drain voltage at CM3 or the voltage VSC of the energy storage device ramps up from zero (i.e., at zero charge) to the reference voltage Vref (i.e., at sufficiently high or full charge). When the energy storage is fully charged so that its voltage VSC surpasses the reference voltage Vref, the comparator circuit outputs a signal that activates the shutdown transistors (SD1 and SD2) and pulls the gates of CM3 and CM2, disabling the entire charging circuit in a standby state. The charging circuit is now uncoupled from the energy storage device and will stop the charging current. The charging circuit remains disabled until the voltage VSC of the energy storage device is less than the reference voltage Vref.

In this paper, the reference voltage achieves a value of 700 mV with minimal swing under varying process parameters, supply voltages, and operating temperatures. It is designed to operate at a supply voltage ranging from 900 mV to 1.9 V and an operating temperature ranging from −40 °C to 85 °C. The charging current reaches 27 mA, considering the worst-case slow–slow corner simulation. The proposed charging circuit is implemented using the 22 nm fully depleted silicon-on-insulator (FDSOI) technology and is integrated into a working energy storage harvesting system.

The SOI process was selected for its excellent performance not only in analog circuits but also in RF circuits, enabling future fully integrated system-on-chip (SoC) solutions [26,27,28,29,30,31].

3. Simulation Results and Discussion

Circuit simulation was performed to verify the performance of the design while considering the target specification shown in Table 1. As part of the requirements, the design should operate in the AVDD minimum voltage of 0.9 V and up to the maximum supply voltage of 1.8 V. The charging current across the supercapacitor (SC) is expected to be from 1 mA to 50 mA, including worst-case conditions. The supercapacitor voltage (VSC) full charge should be from 700 mV to 900 mV.

Table 1.

Target specification of proposed charging circuit.

3.1. Corner Simulation Evaluation

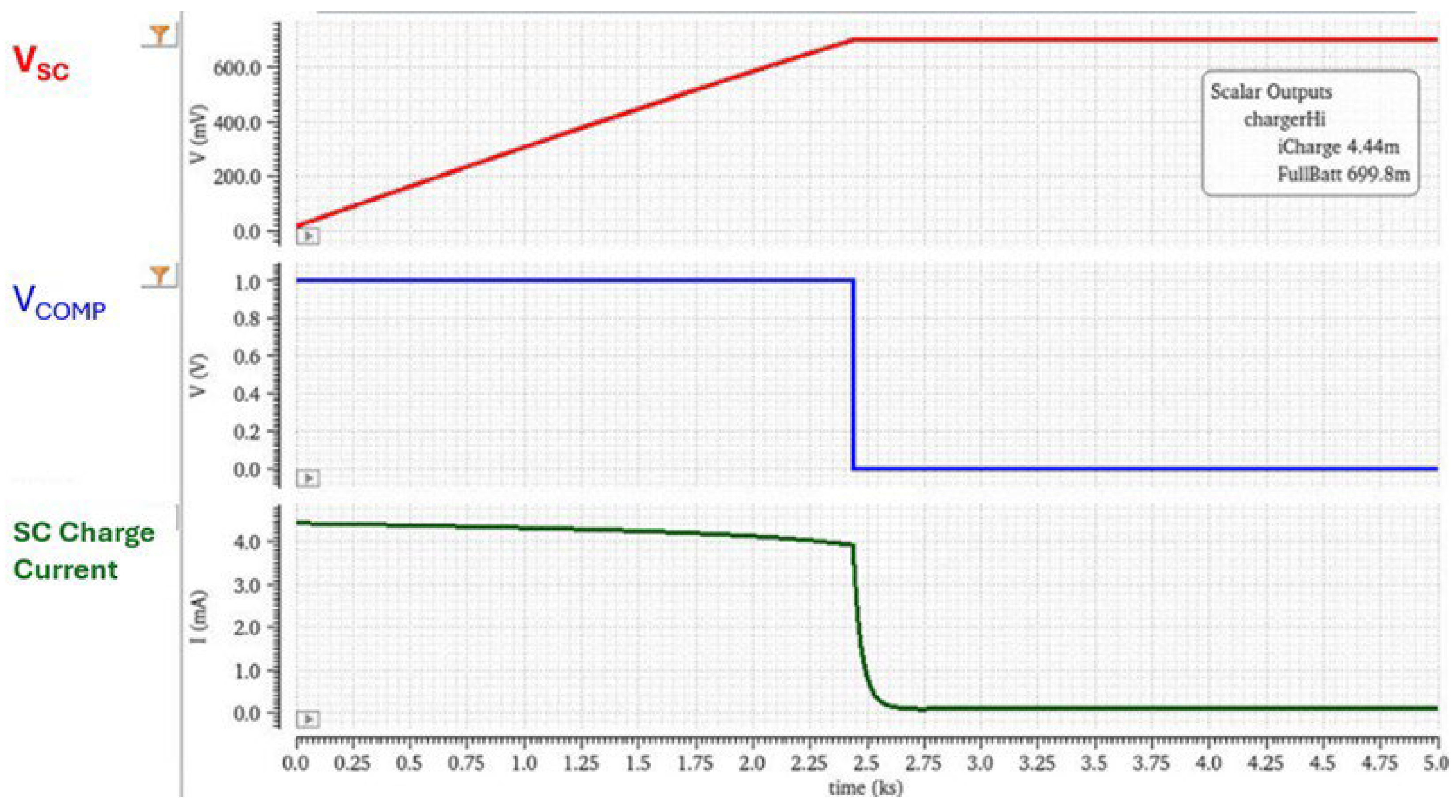

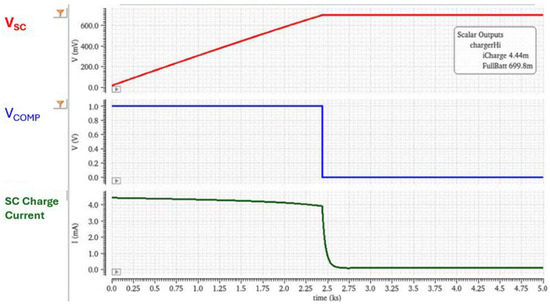

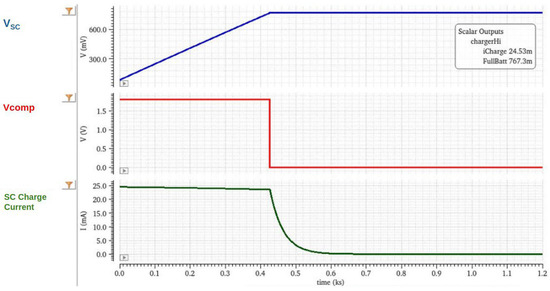

Using a block simulation setup, the behavior of the charging circuit was tested. In a typical simulation, the transient analysis ran from 0s to 5000 s at 25 °C for a nominal model. Figure 3 shows the typical simulation waveform plot of VSC, VCOMP, and the charging current, showing that they meet the target specifications.

Figure 3.

Typical simulation results for VDD = 1.0 V.

As shown in Figure 3, the full battery voltage was measured at the stable state of the VSC pin, which was also connected to the supercapacitor, after the ramp-up or the charging time. The VCOMP signal was “high” at the beginning of the ramp and toggled to “low” after it detected the battery full in the VSC pin, where the VSC voltage surpassed the Vref voltage at the comparator.

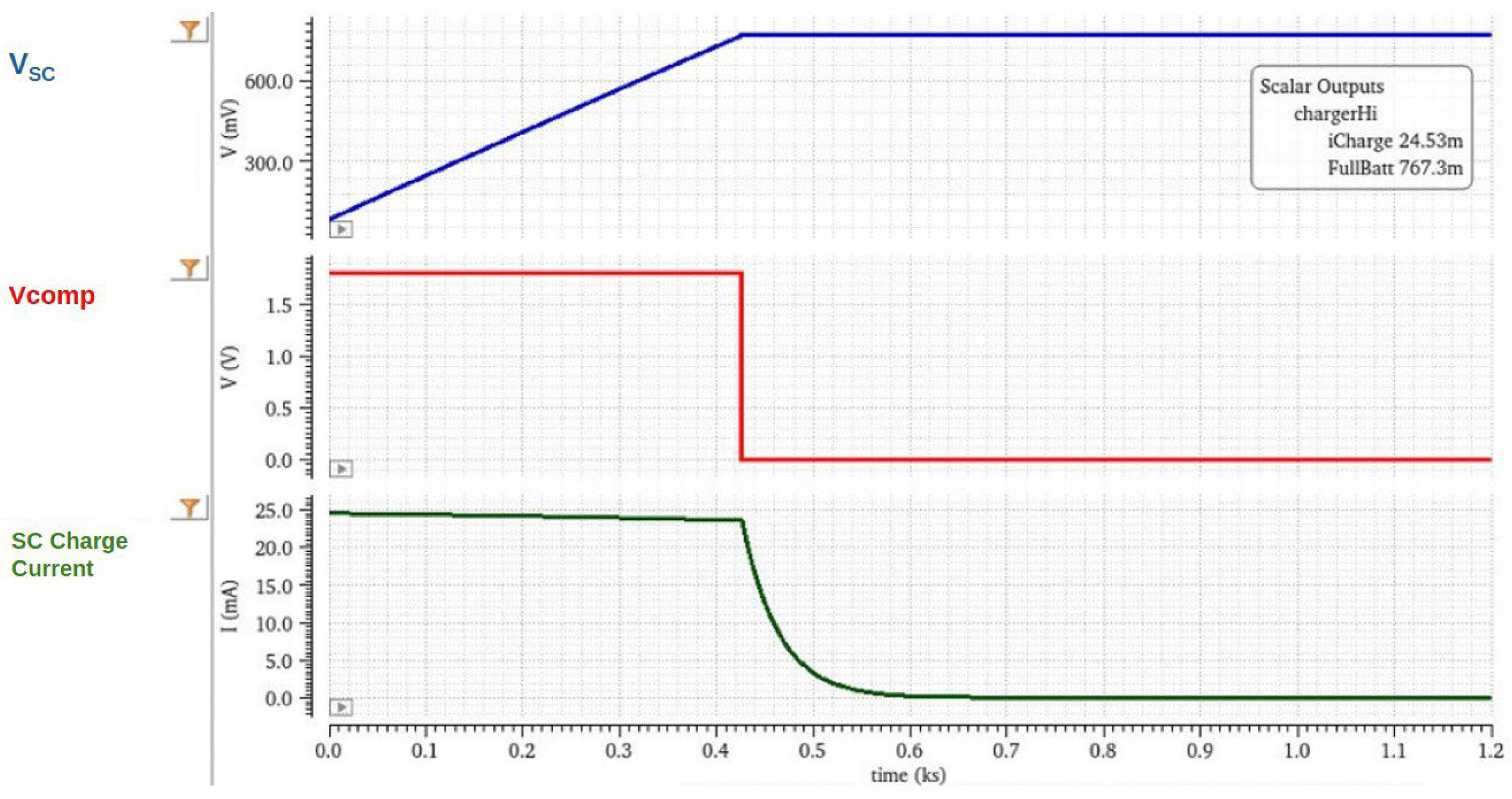

The block was also tested for the maximum VDD of 1.8 V and typical conditions for temperature and process parameters. Figure 4 shows the resulting graph for these conditions.

Figure 4.

Typical simulation results for VDD = 1.8 V.

Further verification through corner simulation was performed to confirm the functionality of the proposed charger block. Table 2 presents the tabular data summarizing the results of the corner simulation.

Table 2.

Corner simulation results.

Corner simulations were tested using three temperature variations (−40 °C, 25 °C, and 85 °C), different model variations (slow, typical, and fast), and two levels of VDD (1.0 V and 1.8 V). All results were passed and within the target specifications. No abnormal response was observed.

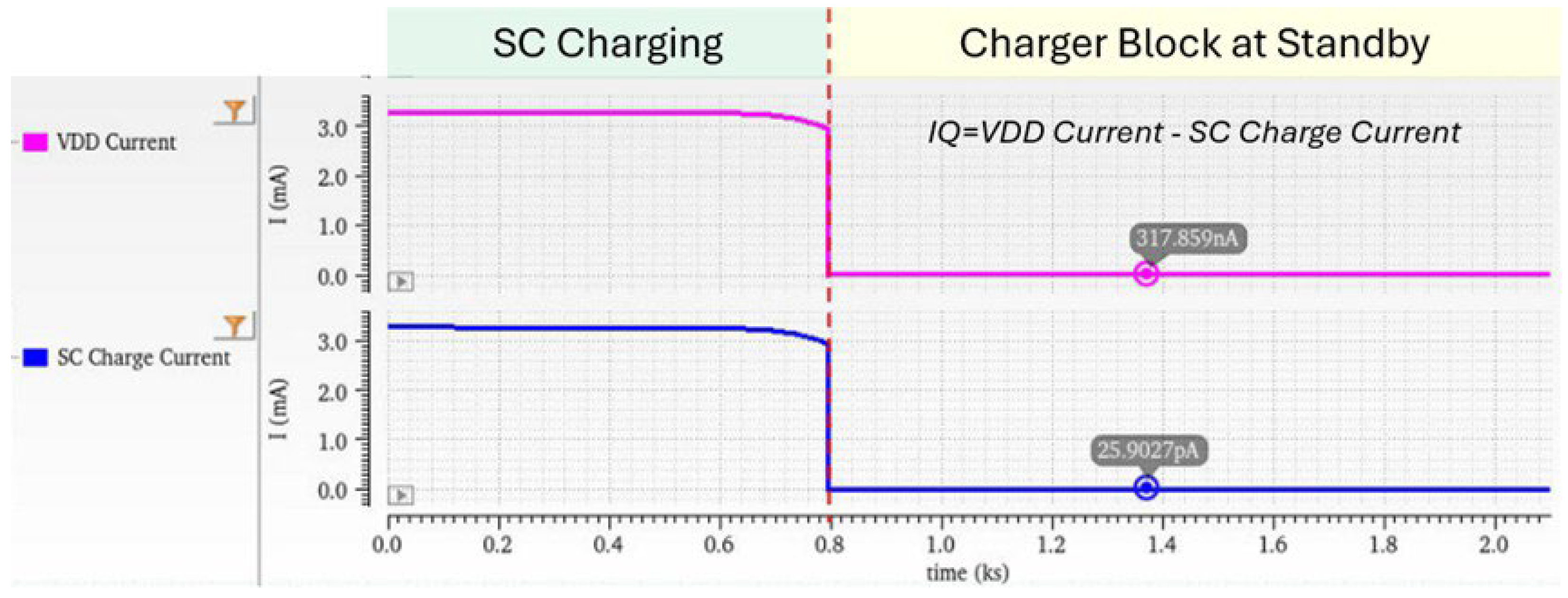

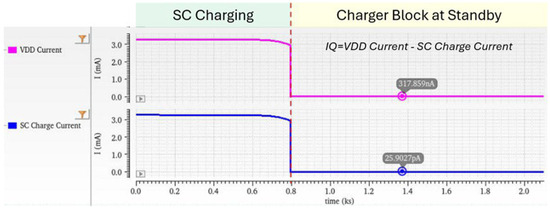

The proposed charger block is intended for ultra-low-power energy-harvesting IoT nodes powered by photovoltaic (PV), thermoelectric (TEG), and RF sources, where the available input power typically ranges from sub-µW to a few tens of µW. In such systems, minimizing standby leakage is essential to ensure efficient energy accumulation and reliable cold-start behavior. The measurement results show that the shutdown quiescent current of the proposed design is 317.8 nA at VDD = 1.0 V and 25 °C. Figure 5 presents the typical simulation waveform used to evaluate the shutdown current, where the quiescent current is calculated using the equation

measured during the shutdown mode. This performance lies within the acceptable range (<500 nA) for PV/TEG/RF energy-harvesting applications and is close to the preferred target (∼300 nA) for high-efficiency autonomous sensor nodes. The low leakage achieved ensures that the charger block does not significantly degrade the harvested energy during sleep periods, thereby supporting long-term autonomous operation of ultra-low-power IoT systems.

IQ = VDD Current – SC Charge Current

Figure 5.

Typical simulation results of IQ in standby mode at VDD = 1.0 V.

3.2. Monte Carlo Simulation Results

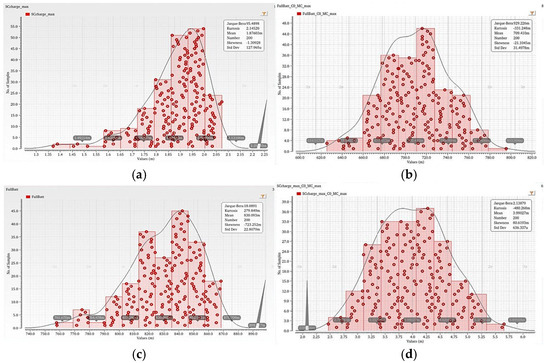

To validate the robustness of the proposed charging circuit design, a Monte Carlo simulation was executed. The simulation was performed under the minimum and maximum conditions of temperature (−40 °C and 85 °C), two VDD values (1.0 V and 1.8 V), sampling of 200 runs, and using the mismatch variation option. Table 3 summarizes the Monte Carlo simulation results separated by the VDD value. All results are within the target specifications.

Table 3.

Statistical summary of Monte Carlo simulation results under different VDD conditions.

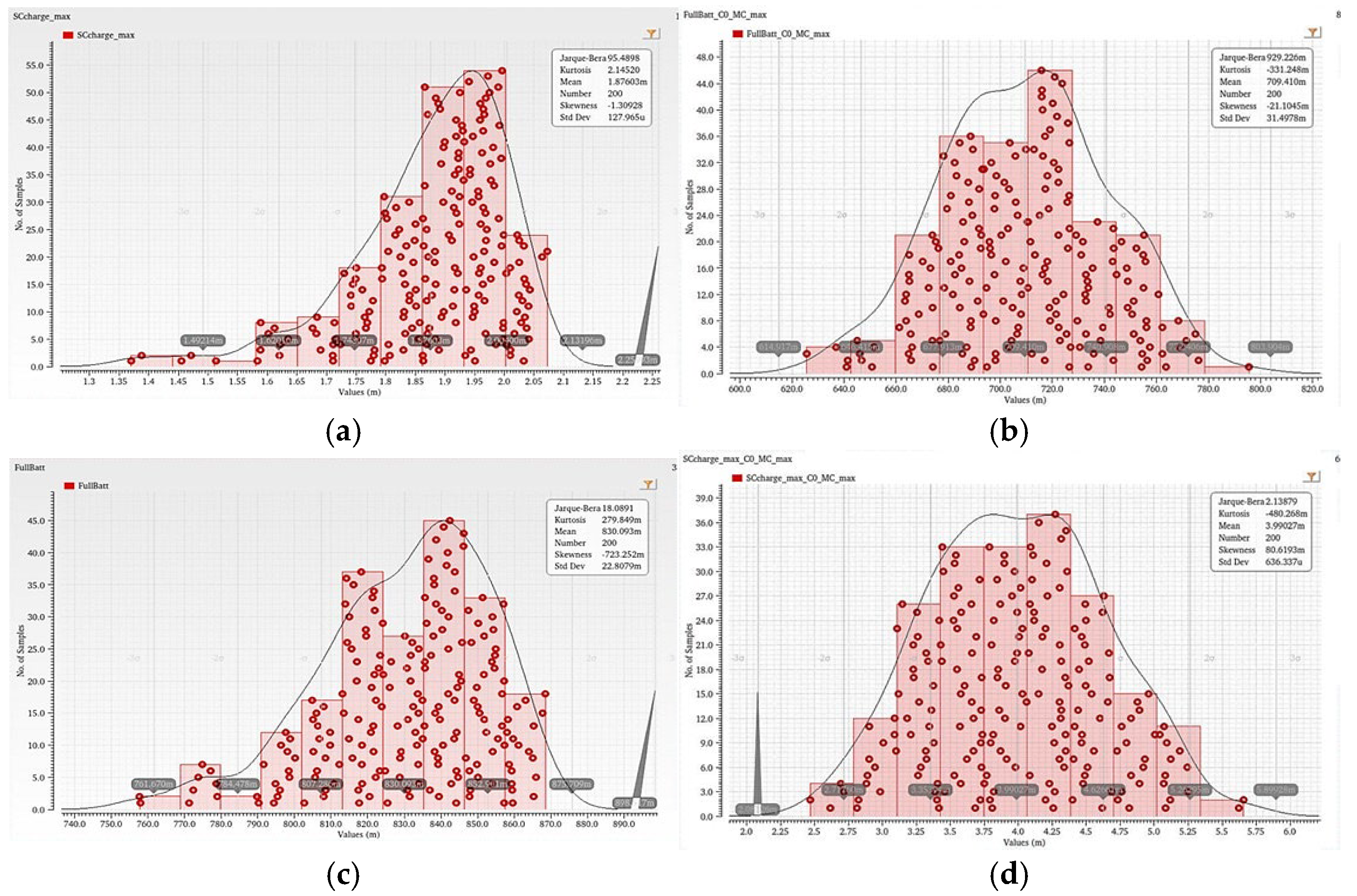

Figure 6 further illustrates the histogram distributions of the SC charge current and SC voltage under both minimum and maximum conditions, confirming the consistency of the circuit’s performance across variations.

Figure 6.

Monte Carlo histogram for (a) minimum condition at VDD = 1.0V, (b) maximum condition at VDD = 1.0 V, (c) minimum condition at VDD = 1.8 V, and (d) maximum condition at VDD = 1.8 V.

4. Evaluation Results and Post-Simulation

4.1. Performance Comparison

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed self-contained charging circuit against the state-of-the-art energy-harvesting solutions. Unlike traditional designs that rely heavily on charge pumps or complex multi-stage rectification, this work demonstrates a self-contained charging topology capable of delivering a significantly higher output current of 25 mA, with a modest output voltage of 0.7–0.8 V, making it well-suited for low-voltage supercapacitor charging in batteryless IoT systems. Prior works, such as those in [15,19,20], exhibit lower current outputs ranging from 10 µA to 395 µA, primarily due to limitations imposed by their charge pump-based or rectifier-based architectures. Moreover, while earlier studies used older CMOS technologies (down to 0.18 µm), this work achieved its performance with a 22 nm FDSOI process, emphasizing its scalability and integration potential. The results validate the effectiveness of a fully self-contained circuit in delivering high current without relying on auxiliary power stages or external control logic.

Table 4.

Comparison of the proposed circuit with published works.

Furthermore, the 22 nm FDSOI process enhances circuit performance through reduced leakage, tighter threshold control, and improved device matching, enabling reliable cold-start operation and high charging currents in a compact layout. In contrast, implementing the design in older CMOS nodes (0.18 µm or 65 nm) would incur higher leakage and standby power, reducing efficiency during low-energy periods typical of batteryless IoT systems and requiring additional design overhead to meet comparable leakage targets.

4.2. Post-Simulation Results

The functionality of the charging circuit was evaluated under different temperature variations, VDD, and using five samples. Since the proposed design was a stand-alone block, the setup was simplified and tested by activating the charging circuit only by supplying VDD.

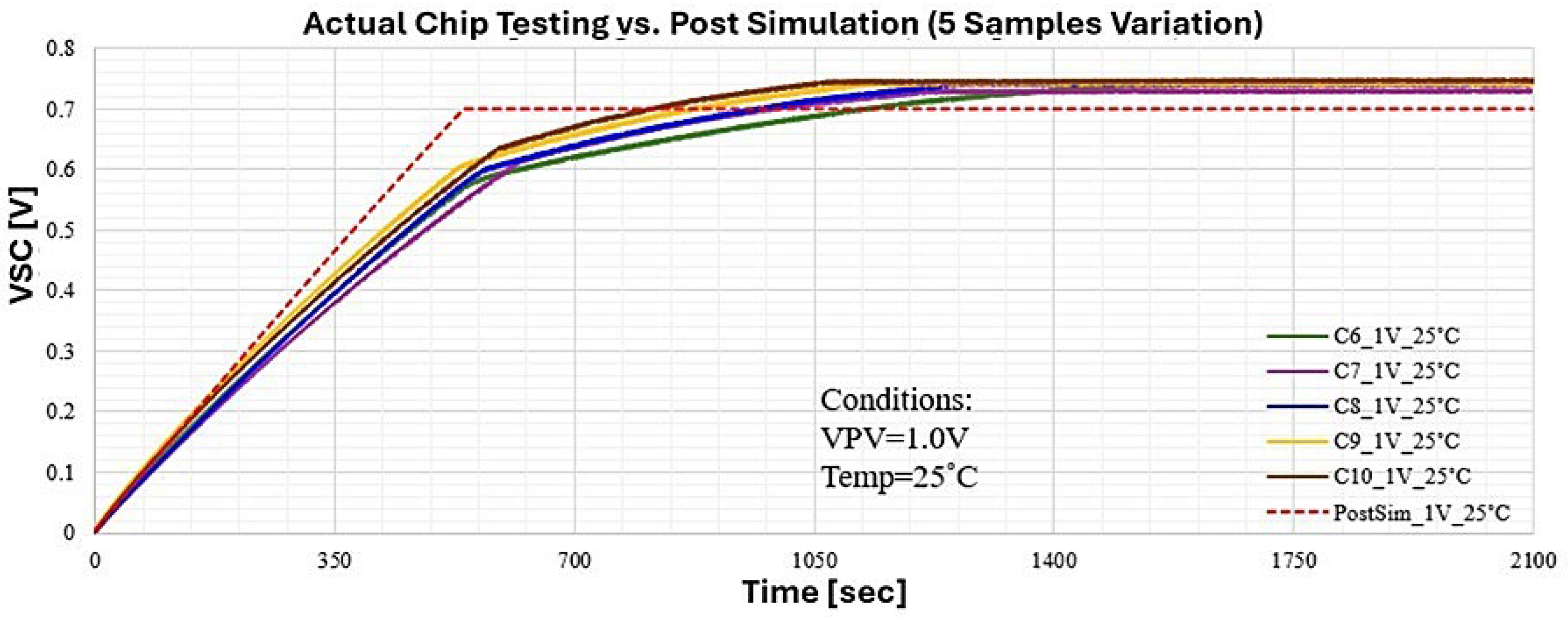

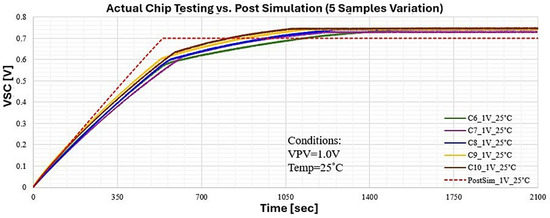

Figure 7 shows the evaluation results of the actual chip testing of chips 6 to 10, labeled as C6 to C10 in the graph, and the post-simulation at 25 °C. As shown in the figure, there is no significant difference observed comparing the post-simulation and the measurement of the five samples tested.

Figure 7.

Supercapacitor voltage (VSC) measurement. Actual chip testing of 5 samples compared with post-simulation at 25 °C.

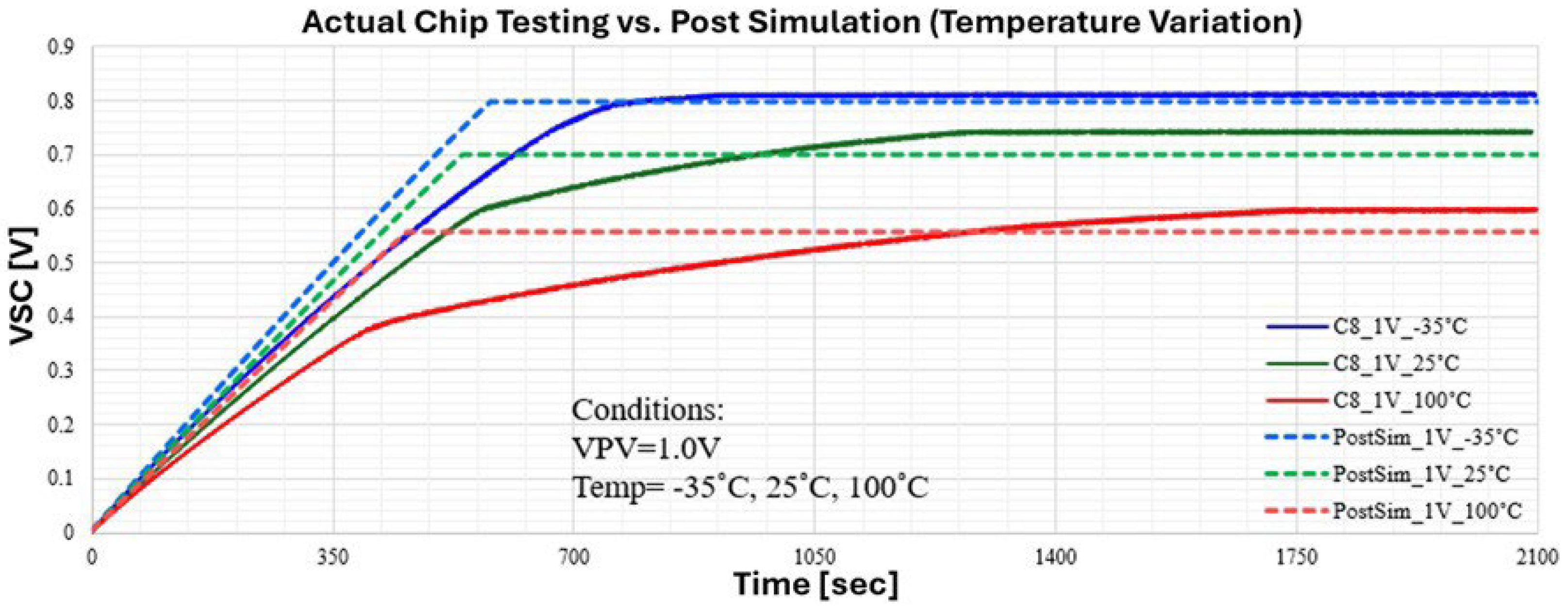

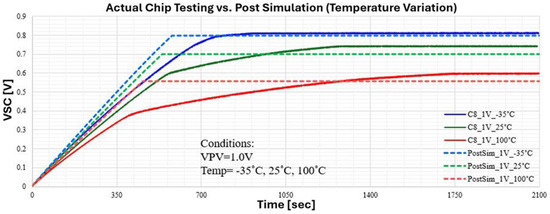

Figure 8 shows the comparison between the actual chip testing and the post-simulation results across −35 °C, 25 °C, and 100 °C. As observed, the simulated output slightly overestimated the measured VSC, but the temperature trend was consistent, confirming reliable behavior under varying thermal conditions [5,6,7,8,9].

Figure 8.

Supercapacitor voltage (VSC) measurement. Actual chip testing of chip 8 compared with post-simulation at three temperatures.

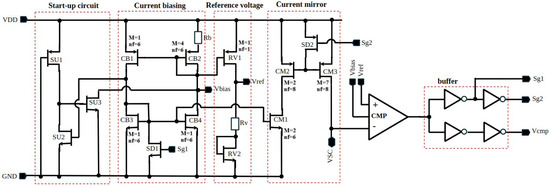

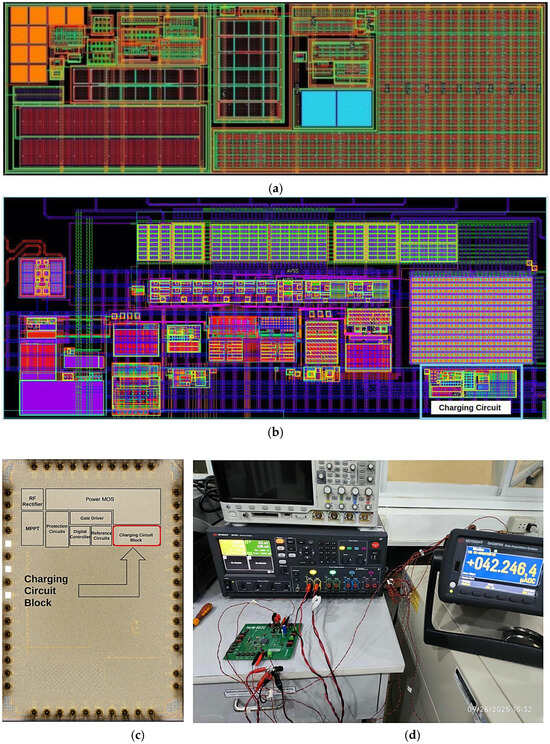

4.3. Chip Layout and Implementation

Figure 9a shows the layout of the charging core, designed and implemented in the 22 nm FDSOI technology. It highlights the transistor-level design of key components such as power switches, capacitors, and control circuitry, all optimized for efficient energy transfer. Figure 9b presents the full-chip layout, with the entire energy-harvesting system, including the charging circuit, occupying a total area of 1000 µm × 400 µm. The design is intended for packaging in a QFN40 (5 mm × 5 mm) package. This layout illustrates the system-level integration of the proposed charging circuit, including its connections to power management, energy storage, and control blocks, with routing carefully optimized to minimize parasitic losses. Figure 9c shows the chip die micrograph, illustrating the fabricated silicon layout of the charging circuit with visible pad placements and key functional blocks. Finally, Figure 9d shows the testing set-up with a DC power analyzer and a thermal chamber for performance validation and measurement.

Figure 9.

Chip layout and implementation: (a) charging core layout, (b) full-chip layout of the energy-harvesting system with integrated charging circuit, (c) chip die micrograph, and (d) testing set-up with DC power analyzer and thermal chamber.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a self-contained charging circuit designed for energy-harvesting systems. The proposed design eliminates the need for external current and voltage references by integrating a current-biasing circuit and a temperature-insensitive reference voltage generator. A simplified yet effective control mechanism using a comparator circuit enables autonomous switching between active charging and standby states, optimizing energy usage.

Simulation results, including typical, corner, and Monte Carlo analyses, confirm the circuit’s robustness across a wide range of process, voltage, and temperature variations. The charging current meets the target specifications, and the reference voltage remains stable across operating conditions. Furthermore, the post-layout and actual chip testing show strong agreement with the simulation results, validating the design’s functionality and reliability in a fabricated silicon implementation.

Overall, the proposed charging circuit demonstrates high efficiency, compactness, and suitability for integration into low-power energy-harvesting applications, such as systems utilizing supercapacitors for energy storage [32,33,34,35,36].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L., K.K.A., J.A.H. and C.G.A.; methodology, M.L., K.K.A. and R.M.C.; validation, M.L., K.K.A., J.A.H. and C.G.A.; formal analysis, M.L. and R.M.C.; investigation, M.L. and R.M.C.; resources, C.G.A.; data curation, M.L. and R.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. and R.M.C.; writing—review and editing, C.G.A., M.L. and R.M.C.; supervision, C.G.A., X.Z. and Y.S.; project administration, C.G.A.; funding acquisition, C.G.A. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology, the Science Education Institute (DOST-SEI), through the Center for Integrated Circuits Design (CICD-Microlab) at Mindanao State University, the Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT), under the DOST-PCIEERD-funded Center for Integrated Circuits and Devices Research (CIDR) program, titled “Energy Harvesting for Battery-less IoT Device Operation.” Additional support was provided by XINYX DESIGN.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported and funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) of the Philippines, with the DOST-Philippine Council for Industry, Energy and Emerging Technology Research and Development (DOST-PCIEERD) serving as the monitoring Agency, and collaborated with Xinyx Design and Consultancy Services, Inc.

Conflicts of Interest

Michelle Libang, Robert M. Comaling, and Charade G. Avondo were employed by the Xinyx Design and Consultancy Services, Inc. The remaining authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Manabat, F.R.; Dayondon, J.H.P.; Fernandez, J.C.R.; Adrivan, K.K.; Hora, J.A. A design of high efficiency non-time division multiplexing battery-less and self-powered multi-input single-inductor single-output using 22 nm FDSOI technology. In Proceedings of the 2023 22nd International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT), Sydney, Australia, 16–18 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Q.; Zhang, Y. Predictive power management for internet of battery-less things. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, F.; Lukas, C.J.; Breiholz, J.; Roy, A.; Patel, H.N.; Liu, N.; Chen, X.; Kosari, A.; Li, S.; Akella, D.; et al. A battery-less 507 nW SoC with integrated platform power manager and SiP interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on VLSI Circuits, Kyoto, Japan, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. C338–C339. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, C.J.; Yahya, F.B.; Breiholz, J.; Roy, A.; Chen, X.; Patel, H.N.; Liu, N.; Kosari, A.; Li, S.; Kamakshi, D.A.; et al. A 1.02 W battery-less, continuous sensing and post-processing SiP for wearable applications. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2019, 13, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Cai, M.; Jiang, Y. Key role of cold-start circuits in low-power energy harvesting systems: A research review. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2024, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Anand, T.; Johnston, M.L. Integrated cold-start of a boost converter at 57mV using cross-coupled complementary charge pumps and ultra-low-voltage ring oscillator. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2019, 54, 2867–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeppert, J.; Manoli, Y. Fully integrated startup at 70mV of boost converters for thermoelectric energy harvesting. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2016, 51, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, G.; Lian, Y. A batteryless single-inductor boost converter with 190 mV self-startup voltage for thermal energy harvesting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2019, 66, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadass, Y.K.; Chandrakasan, A.P. A battery-less thermoelectric energy harvesting interface circuit with 35 mV startup voltage. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2011, 46, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zeng, Y. A 7.5 mV input and 88%-efficiency single-inductor boost converter with self-startup and MPPT for thermoelectric energy harvesting. Micromachines 2023, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudevalayam, S.; Kulkarni, P. Energy harvesting sensor nodes: Survey and implications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2011, 13, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinuela, M.; Mitcheson, P.D.; Lucyszyn, S. Ambient RF energy harvesting in urban and semi-urban environments. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 2013, 61, 2715–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Han, P.; Mei, N. A review of converter circuits for ambient micro energy harvesting. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Amaratunga, G.A.; Seshia, A.A. A cold-startup SSHI rectifier for piezoelectric energy harvesters with increased open-circuit voltage. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 34, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Ishida, K.; Zhang, X.; Okuma, Y.; Ryu, Y.; Takamiya, M.; Sakurai, T. 0.18-V input charge pump with forward body biasing in startup circuit using 65 nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 19–22 September 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ballo, A.; Grasso, A.D.; Palumbo, G. A review of charge pump topologies for the power management of IoT nodes. Electronics 2019, 8, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kwon, I. A capacitive DC-DC boost converter with gate bias boosting and dynamic body biasing for an RF energy harvesting system. Sensors 2023, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comaling, R.M.; Zhu, X.; Hora, J.A. A 95.71% power efficiency DC-DC PFM boost converter with recursive voltage supply technique for low-power energy harvesting application. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th International Symposium on Microwave, Antenna, Propagation and EMC Technologies for Wireless Communications (MAPE), Guangzhou, China, 27–30 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Yen, S.-Z.; Chen, J.-H.; Hong, H.-C.; Cheng, K.-H. Low-voltage indoor energy harvesting using photovoltaic cell. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Design and Diagnostics of Electronic Circuits & Systems (DDECS), Kosice, Slovakia, 20–22 April 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Mocorro, C.O.; Pinaso, J.; Cheng, K.-H. Indoor energy harvesting using photovoltaic cell for battery recharging. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Design and Diagnostics of Electronic Circuits Systems (DDECS), Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic, 8–10 April 2013; pp. 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Osaki, Y.; Hirose, T.; Kuroki, N.; Numa, M. 1.2-V supply, 100-nW, 1.09-V bandgap and 0.7-V supply, 52.5-nW, 0.55-V subbandgap reference circuits for nanowatt CMOS LSIs. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2013, 48, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrivan, K.K.C.; Hora, J.A. A nano-watt, subthreshold self-biased CMOS voltage reference without resistors and BJT. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2022 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Hong Kong, China, 1–4 November 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Comaling, R.M.; Diangco, M.M.C.; Hora, J.A. 22 nm FDSOI forward body biasing in designing ultra-low power, high PSRR voltage reference for IoT power management applications. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2023 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 31 October–3 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ruetz, E.J. Bias Start-Up Circuit. European Patent EP0515065A1, 25 November 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Y.-S.; Wang, S.-C.; Yang, F.-C.; Chen, J.-J. New compact CMOS Li-ion battery charger using charge-pump technique for portable applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2007, 54, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Dutkiewicz, E.; Shum, K.M.; Xue, Q. An on-chip bandpass filter using a broadside-coupled meander line resonator with a defected-ground structure. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2017, 38, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nericua, R.; Wang, K.; Zhu, H.; Gómez-Garcia, R.; Zhu, X. Low-loss and compact millimeter-wave silicon-based filters: Overview, new developments in Silicon-on-Insulator technology, and future trends. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst. 2024, 14, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Ge, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, X. A 40-GHz Load Modulated Balanced Power Amplifier Using Unequal Power Splitter and Phase Compensation Network in 45-nm SOI CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Papers 2023, 70, 3178–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, F.; Zhu, X. A second-order bandpass filter with 1.6-dB insertion loss and 47-dB upper-stopband suppression in 45-nm SOI CMOS technology. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2024, 45, 1710–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Sun, D.; Sun, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, X. A 39 GHz Doherty-like power amplifier with 22 dBm output power and 21% power-added efficiency at 6 dB power back-off. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2024, 14, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorospe, J.M.; Nericua, R.; Chen, K.-H.; Zhu, X. Stability-Enhanced Low-Dropout Regulator with High PSRR in 40-nm CMOS for System-on-Chip Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2026, 41, 3296–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, M.E.; Blaabjerg, F.; Sangwongwanich, A. A comprehensive review on supercapacitor applications and developments. Energies 2022, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vullers, R.J.M.; van Schaijk, R.; Doms, I.; Van Hoof, C.; Mertens, R. Micropower energy harvesting. Solid-State Electron. 2009, 53, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, G.K.; Hofmann, H.F.; Bhatt, A.C.; Lesieutre, G.A. Adaptive piezoelectric energy harvesting circuit for wireless remote power supply. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2002, 17, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, M.; Romani, A.; Filippi, M.; Fiegna, C.; Masotti, D.; Tartagni, M. A nano-current power management IC for multiple heterogeneous energy harvesting sources. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 5665–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeby, S.; White, N. Energy Harvesting for Autonomous Systems; Artech House: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).