Abstract

Physically unclonable functions (PUFs) generate keys for cryptographic applications, eliminating the need for conventional key storage mechanisms. Since PUF responses are inherently noise-sensitive, their reliability can decrease under varying conditions. Integrating channel coding can enhance response stability and consistency. This work presents an efficient scheme that integrates a delay-base d PUF with a Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) code. Specifically, a feed-forward PUF is combined with LDPC coding to reliably regenerate the cryptographic key. Our design reproduces the key with minimal error using channel coding. The scheme achieves 96% key-generation reliability, representing a notable improvement over PUF-based key generation without error-correction coding. LDPC decoding with the min-sum algorithm provides better error correction than the bit-flipping algorithm, but it is more computationally intensive. We could design the proposed scheme with minimum hardware resource utilization using Xilinx Vivado 2018.2 and Cadence Genus tools.

1. Introduction

PUFs derive their challenge–response behavior from uncontrollable manufacturing variations, including random deviations in device dimensions and gate oxide thickness. These unique variations generate distinct responses to specific challenges, making PUFs effective for device authentication and secure key generation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

Arbiter PUF can generate numerous responses based on the applied challenge, while SRAM PUF and Butterfly PUF produce only a limited set of challenge-response pairs. Arbiter PUF generates challenge-response pairs using a delay-based mechanism. In contrast, SRAM PUF and Butterfly operate based on a memory-based bistable structure [1,2,4,6].

The feed-forward physically unclonable function introduces non-linearity through feed-forward loops, making the challenge-response behavior more complex and difficult to predict. This added non-linearity significantly enhances the computational effort required for attacks, thereby improving security for cryptographic key generation in applications such as IoT. Lata et al. [6] present a comparative analysis of various PUF designs, highlighting their respective advantages as well as the challenges associated with each.

PUFs can generate unique, unclonable cryptographic keys for authentication and secure communication, making them suitable for applications in 5G networks [5,6,7]. Environmental factors can lead to inaccuracies in the PUF response, resulting in a bit error rate that affects its reliability. This bit error rate can be mitigated by implementing an error correction coding technique for the PUF response [8,9,10,11,12,13].

Key performance metrics for a PUF design include uniqueness, reliability, randomness, bit error rate, area and power efficiency, and security against attacks. Our work focuses on error correction codes in PUFs, making reliability a critical metric that measures response consistency.

Reliability in data transmission and storage is achieved through Error Correction Coding (ECC) techniques, which identify and correct errors introduced by noise and hardware imperfections. Hamming codes, Reed-Solomon codes, LDPC, and polar codes are widely used to detect and rectify errors within communication systems [8]. Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) codes can achieve error correction close to the theoretical limit with efficient decoding, making them highly effective for high-speed applications like 5G networks [14,15].

A wide range of approaches have been explored to apply the error correction coding scheme to physically unclonable functions [8,9,16]. Hiller et al. [8] provide a comparison of various combinations of PUF and channel coding techniques, analyzing bit error rates along with FPGA resource utilization, power consumption, and area as performance metrics. Jarvis et al. [9] compare BCH codes and convolutional codes as error correction methods for PUF. Maes et al. [16] implement a code-offset scheme using repetition and RM codes for SRAM PUF.

In our work, we utilize LDPC coding for reliable key production from a feed-forward arbiter PUF. The decoding process involves both bit-flipping and min-sum algorithms. The bit-flipping algorithm iteratively corrects erroneous bits based on parity check failures. While this approach is straightforward, it tends to perform poorly with high-error-rate PUF responses. Conversely, the min-sum algorithm, which serves as an approximation of belief propagation, optimizes check node updates to achieve near-Shannon-limit error correction while maintaining compact hardware utilization.

Background and related studies are discussed in Section 2. The proposed method is outlined in Section 3. Section 4 presents the results and analysis, including a comparison with related work. Finally, Section 5 addresses the challenges encountered and suggests possible future work to enhance the system.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Arbiter PUF

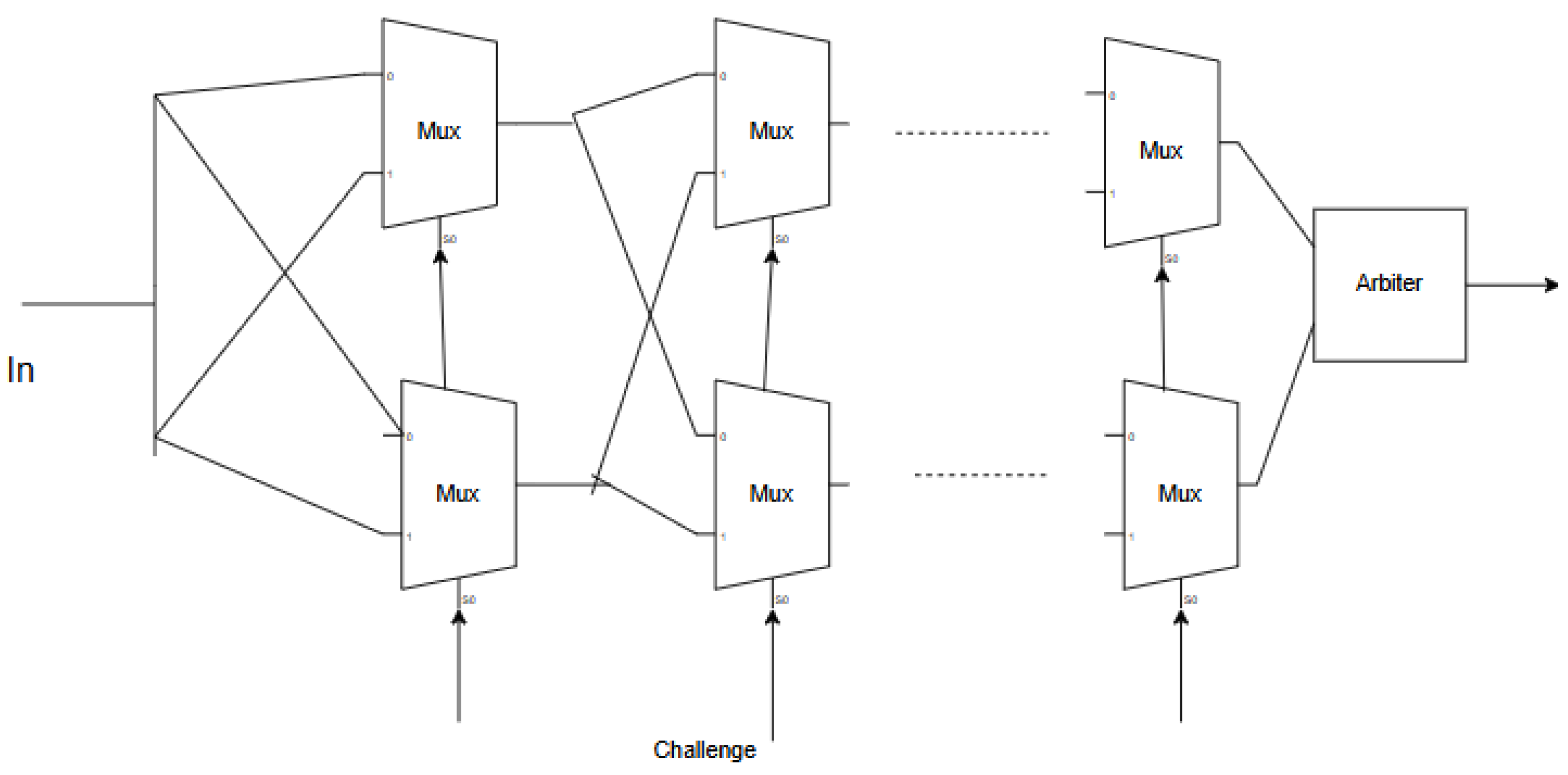

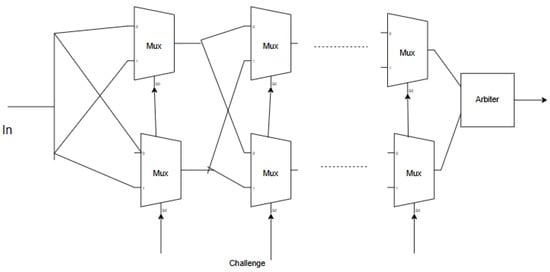

The Arbiter PUF is a type of physically unclonable function that operates based on delay variations. Arbiter PUF structure is shown in Figure 1. The Arbiter PUF consists of 2-to-1 multiplexers and a D flip-flop, which functions as an Arbiter. For an n-bit Arbiter PUF, multiplexers will be connected as illustrated in Figure 1. The challenge bits are utilized as select lines for each multiplexer. Variations in manufacturing can lead to delays in input arrival times to the D flip-flop, resulting in unpredictable outputs. This randomness in the PUF response makes it challenging for attackers to anticipate, allowing it to be effectively used as a key for cryptographic applications in IoT and embedded systems [1,5,6].

Figure 1.

Arbiter PUF.

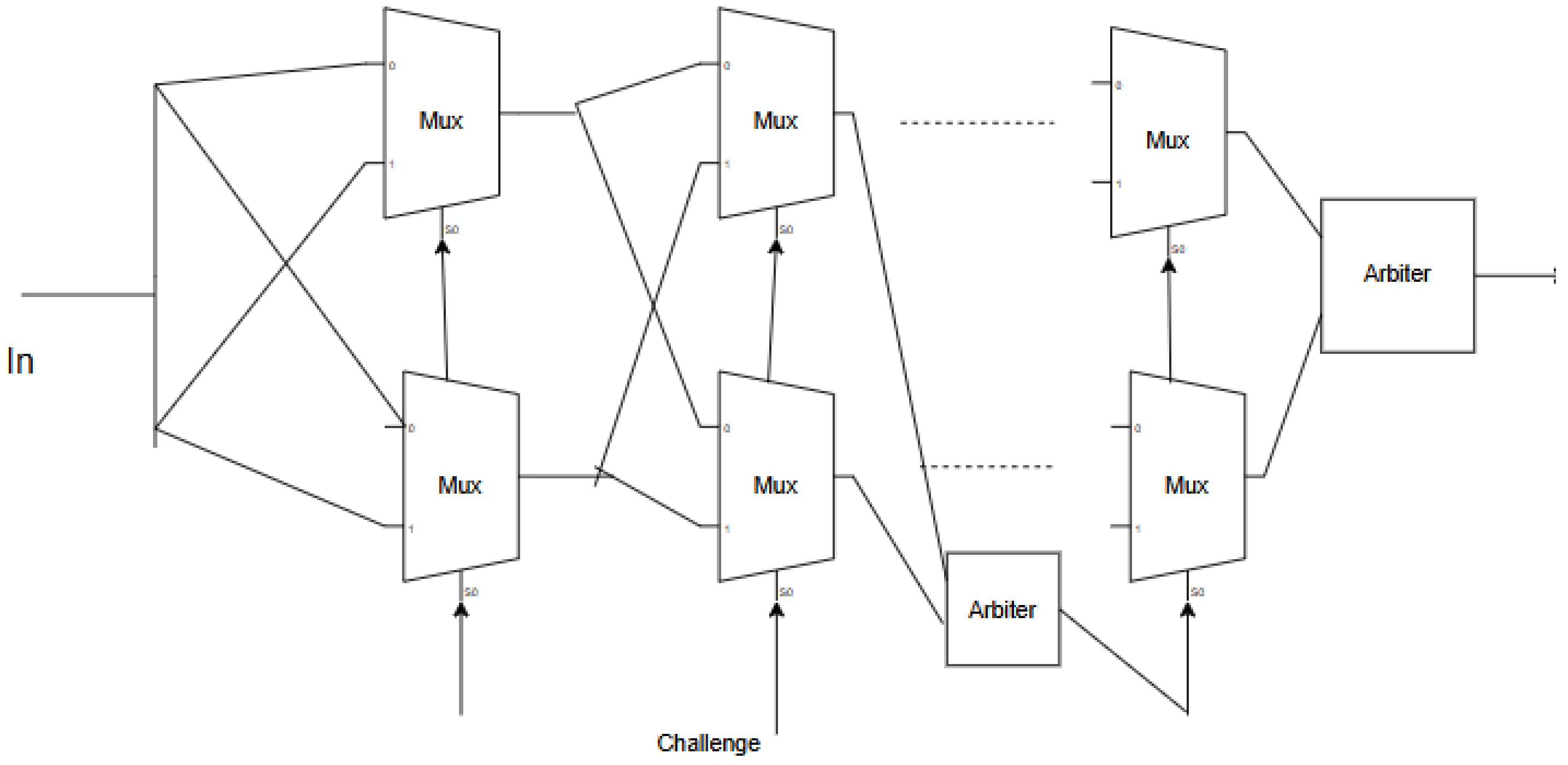

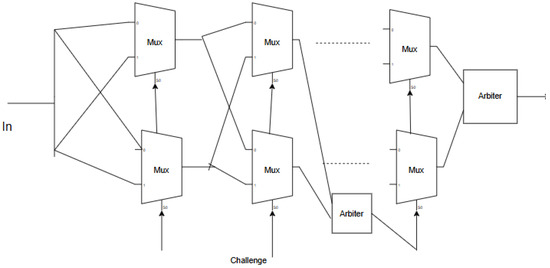

2.2. Feed-Forward Arbiter PUF

The Arbiter PUF is modified by placing an Arbiter (D flip-flop) in between the multiplexer array, as shown in Figure 2. The feed-forward physical unclonable function (PUF) consists of 64 stages. We utilize two feed-forward taps located after stages 20 and 40. The outputs from these taps will serve as select lines for subsets of multiplexers during later operations, specifically at stages 30–33 and 50–55. The arbiter uses a D flip-flop (D-FF), which outputs a logic ‘1’ when the rising edge of the input signal (D) occurs earlier than the rising edge of the clock (clk) by at least the required setup time of the flip-flop. This modification aims to increase the randomness of the PUF response. Kumar et al. [2] implemented a feed-forward PUF in FPGA and ASIC and observed the power, area, speed, and device utilization in the Spartan 3E FPGA.

Figure 2.

Feed-forward PUF.

2.3. Error Correction Codes

Error correction codes play a crucial role in communication systems by ensuring that messages are accurately reproduced at the receiver. In channel coding techniques, redundant bits are systematically added to the message, facilitating error correction. Commonly used error correction codes include convolutional codes, block codes, BCH codes, LDPC codes, Reed–Solomon (RS) codes, and polar codes. LDPC codes are recognized for their exceptional error correction abilities and their capacity to manage a high error threshold. The LDPC method employs a sparse matrix H, which contains fewer ones compared to zeros [10,17]. The input message of k bit size is multiplied by a systematic generator matrix G to produce an n-bit codeword [10,18,19,20]. In our work, we used an LDPC encoder for different codeword lengths (128, 256) and analyzed decoder efficiency for different code rates (1/2, 2/3, and 3/4).

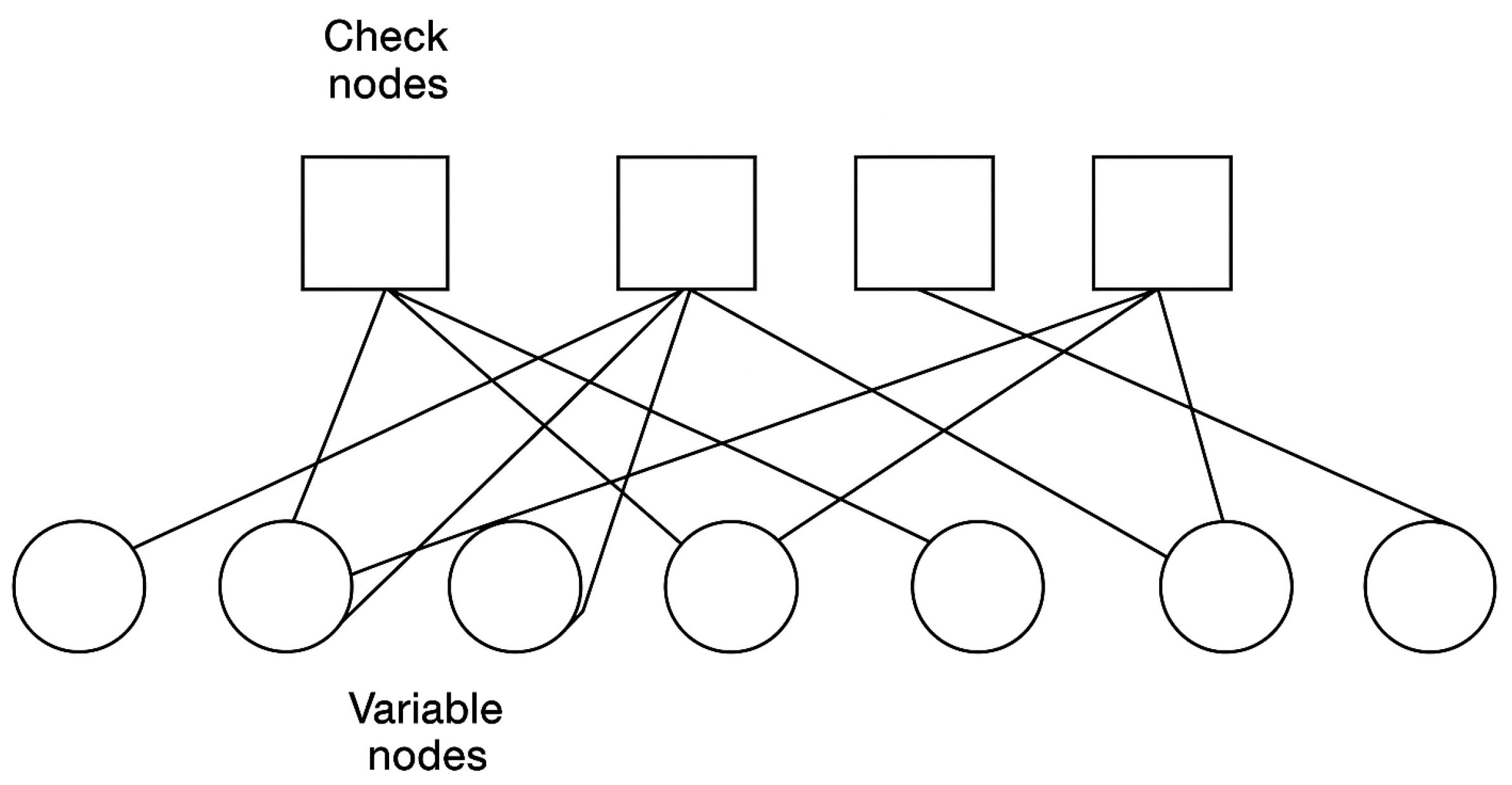

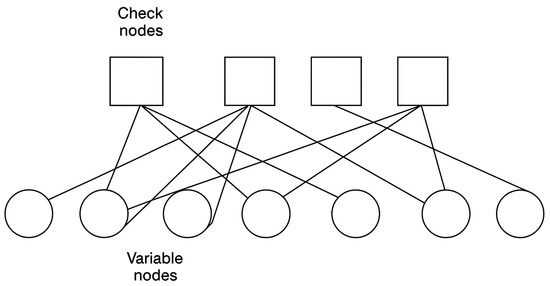

2.3.1. Tanner Graphs

Tanner graphs illustrate the parity check matrix of a Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) code. In these graphs, check nodes represent the parity check equations, while variable nodes represent the codeword bits. When a specific bit is included in a parity check equation, it is connected to the corresponding check node by an edge [10,21]. Tanner graph with codeword length 7 and message size 3 is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tanner graph.

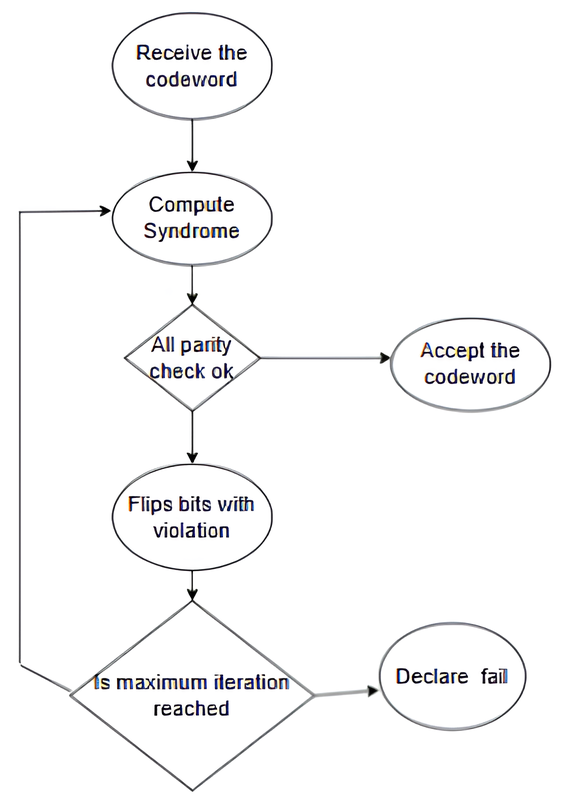

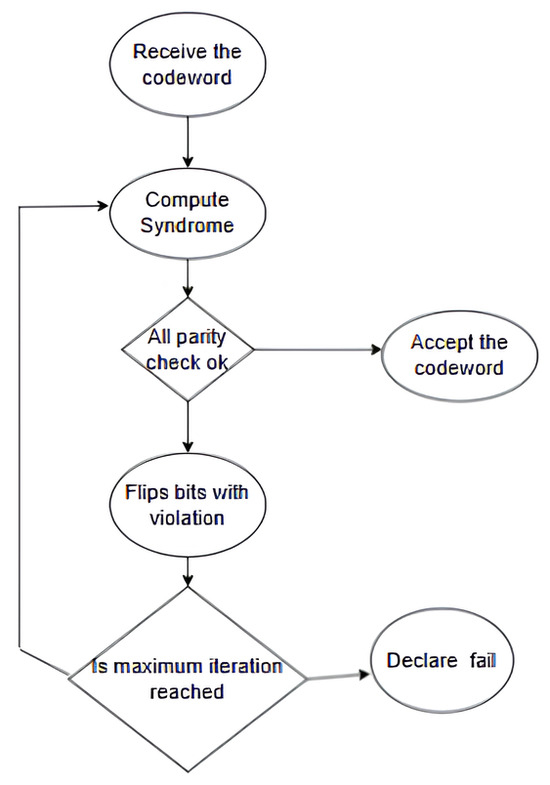

2.3.2. Bit-Flipping Algorithm

The bit-flipping algorithm is a straightforward decoding technique, especially when compared to other LDPC decoding methods. However, this algorithm struggles to correct errors when the number of erroneous bits is high. It works by flipping the bits that do not satisfy the parity check equations, and this process continues until all checks are satisfied. Figure 4 shows a flow chart for the bit-splitting algorithm.

Figure 4.

Bit flipping decoding algorithm.

2.3.3. Minimum Sum Algorithm

The minimum sum decoding algorithm is more complex compared to the bit-flipping algorithm, but it has more error correction capability. This decoding algorithm is widely used in standards like 5G and Wi-Fi. All messages are initialized with channel log Likelihood ratios. Sign and magnitude are to be computed for each connected variable node. The sum of channel log Likelihood ratios is calculated for each check node. Total LLR for each variable node is calculated. Decoding continues up to the specified maximum number of iterations [18].

2.4. Error Correction on PUF

Physically unclonable function provides an alternative method to key storage in security applications of lightweight embedded devices. Hiller et al. provide a comparison of various error correction designs for PUFs, focusing on PUF response bits and FPGA slice utilization. Ganorkar et al. [22] use Euclidean geometry Low-Density Parity Check the coding scheme over PUF for secure key generation using the bit-flipping algorithm. Kumar et al. [10] used Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) error correction code in conjunction with the Modified Anderson PUF, resulting in improved uniformity and reliability.

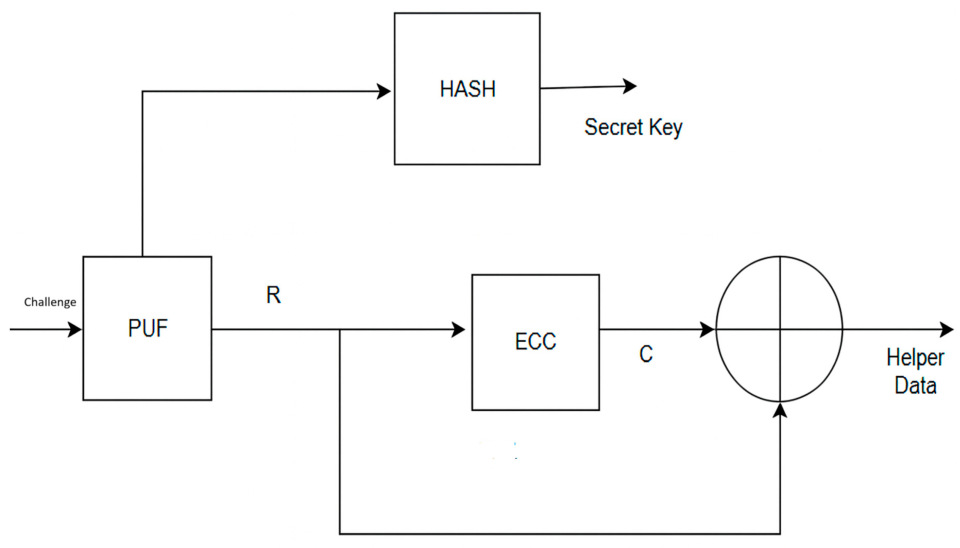

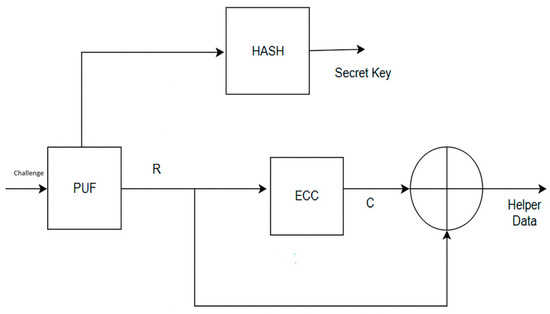

3. Key Generation and Reconstruction

The key construction using the proposed method is shown in Figure 5, and the key reconstruction method is shown in Figure 6. The feed-forward PUF produces a response R with respect to an applied challenge. The reliability of feed-forward PUF is calculated by applying the same challenge multiple times. The secret key is constructed from the PUF response using the HASH (SHA 256) function.

Figure 5.

Key generation phase.

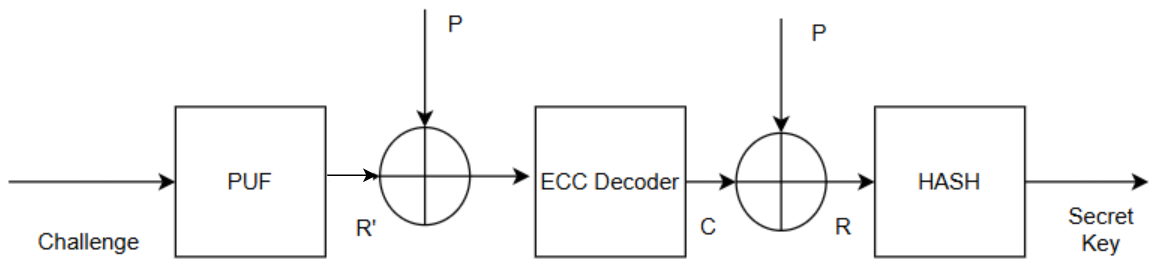

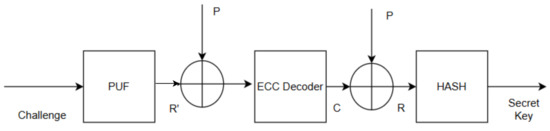

Figure 6.

Key reconstruction phase.

Helper Data Generation

The helper data is computed as where R is the response from the feed-forward PUF, and C is the codeword generated by the LDPC encoder. The XOR operation is used because the LDPC code is linear, allowing the codeword to act as a mask for the noisy response. During key reconstruction, the device measures a noisy response R′. Using the stored helper data and the reconstruction algorithm, the decoder is able to recover C through the operation = = . This scheme does not increase hardware complexity and maintains a linear relationship, which is important for both security and entropy analysis. This helper data procedure is consistent with the code-offset construction in foundational fuzzy extractor designs. Helper data reduces the uncertainty of the PUF response. If H(R) represents the entropy of the puf response and H(R/P) represents the entropy of the response after observing helper data, then minimizing information leakage requires maximizing H(R/P) so that the helper data reveals as little as possible about R.

In the key reconstruction stage, the same physical unclonable function (PUF) is used to generate a response, denoted as R′, by applying the same challenge bits. However, R′ may differ from the original response R.

To recover the original information, R′ is XORed with helper data to produce a 128-bit codeword, C′. An LDPC (Low-Density Parity-Check) decoder is then utilized to retrieve the original codeword, C, from C′. The original PUF response is generated from the codeword C and the helper data. Finally, the response R is hashed to retrieve the secret keyword.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Feed-Forward PUF Implementation Results

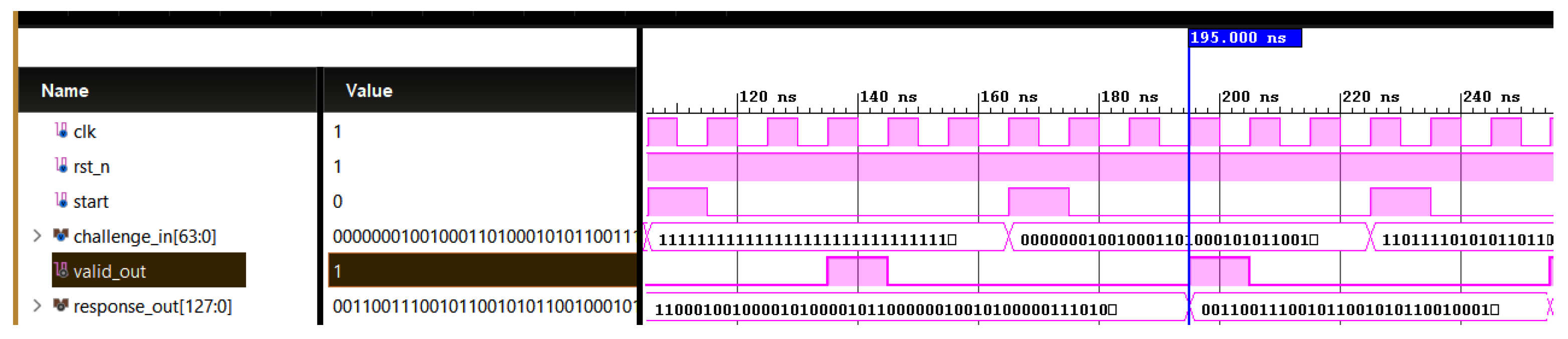

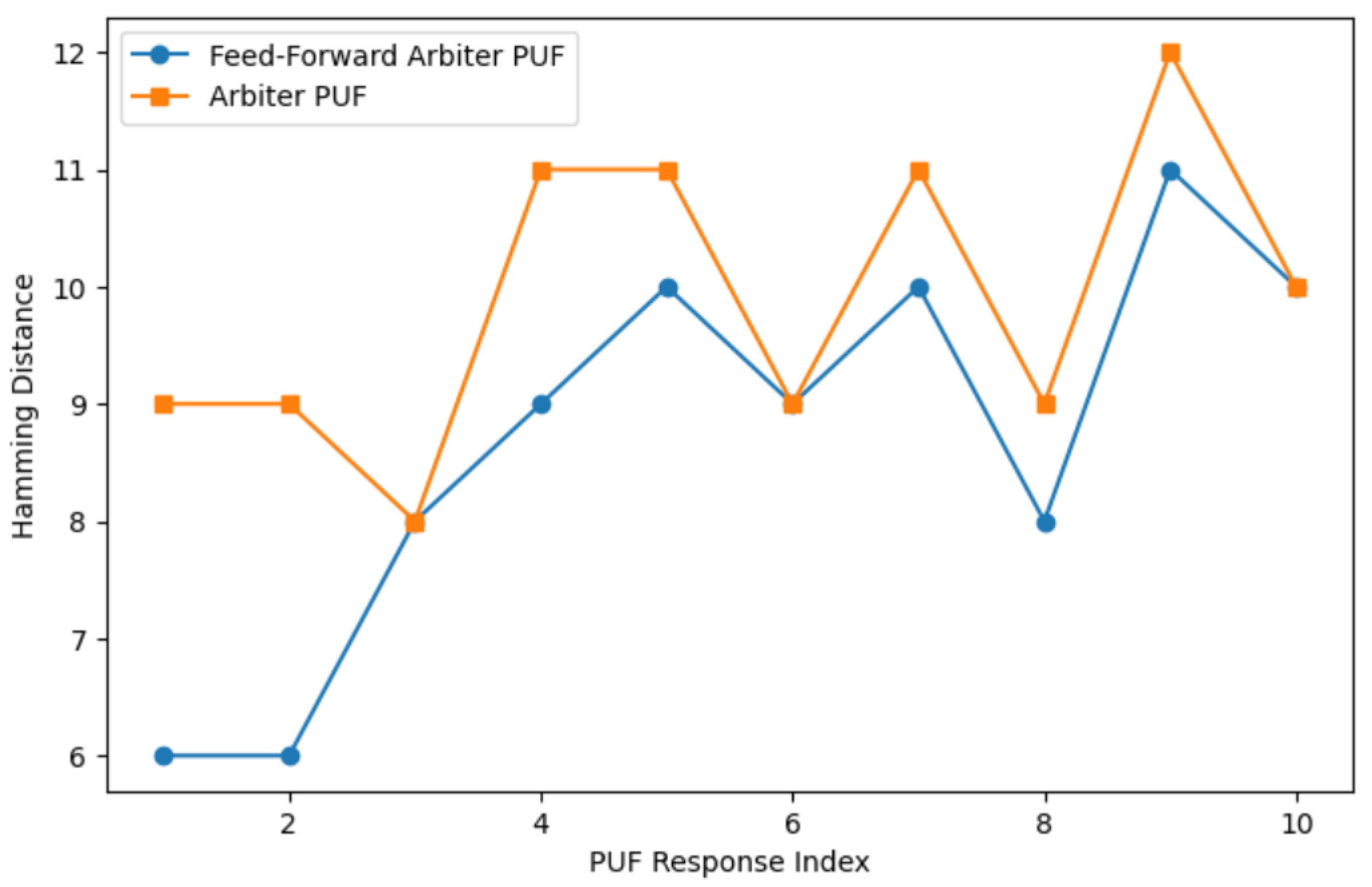

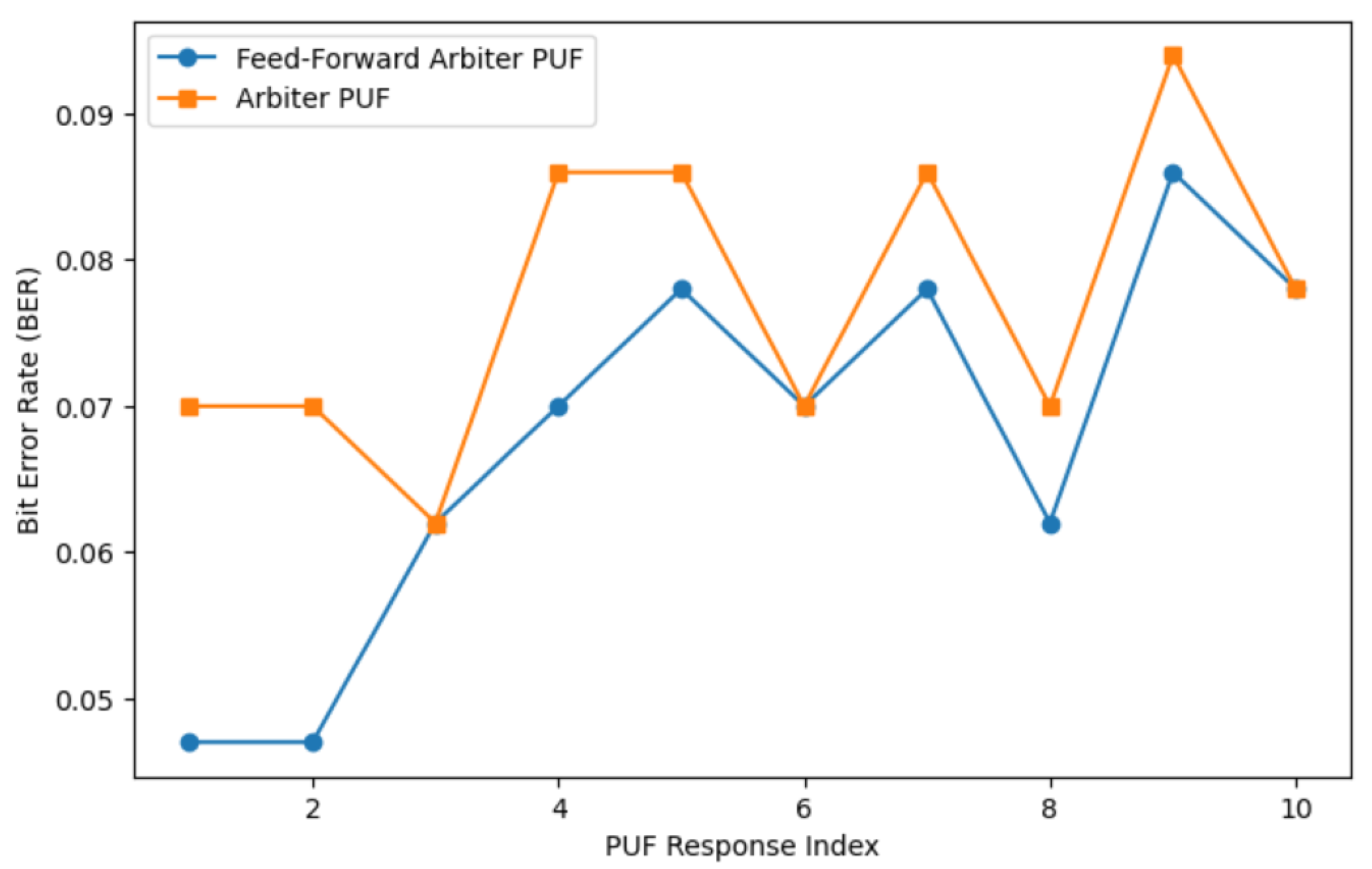

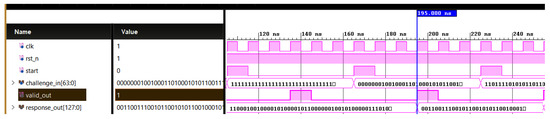

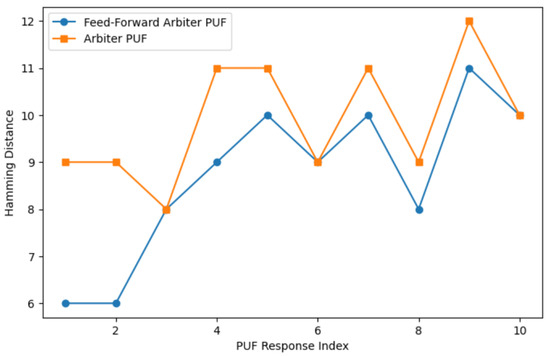

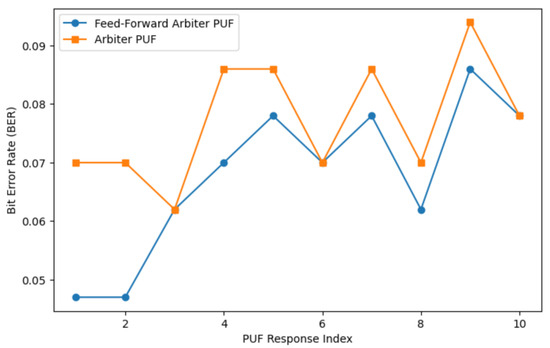

Responses of Arbiter PUF and feed-forward physically unclonable functions (PUFs) have been evaluated for various response lengths. Figure 7 shows the simulation result for a 128-bit response from a feed-forward PUF. PUF reliability is quantified as 1-intraHD, where intraHD represents the average Hamming distance between repeated measurements of the same challenge. Figure 8 and Figure 9 give a comparison of Hamming distances and bit error rate for Arbiter PUF and feed-forward Arbiter PUF across multiple response samples. Table 1 shows the average reliability and the average bits in error measured from these readings % and , respectively. The feed-forward design consistently achieves a lower BER for most response indices, demonstrating improved stability against environmental and temporal noise. Reliability must be enhanced for cryptographic key generation. The use of error correction coding techniques can improve the reliability of PUF responses.

Figure 7.

Simulation waveform for 128 bit feed-forward PUF. Challenge (64 bit): 0000000100100011010001010110011110001001101010111100110111101111, Response_out (128): 00110011100101100101011001000101010001111100111011110111110101011000110110110001001000011010001011111001101011010110100111001110.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Hamming distances for Arbiter PUF and feed-forward Arbiter PUF across multiple response samples.

Figure 9.

Bit error rate (BER) comparison between the Arbiter PUF and the feed-forward Arbiter PUF across multiple response samples.

Table 1.

Comparison of BER and reliability for various PUFs.

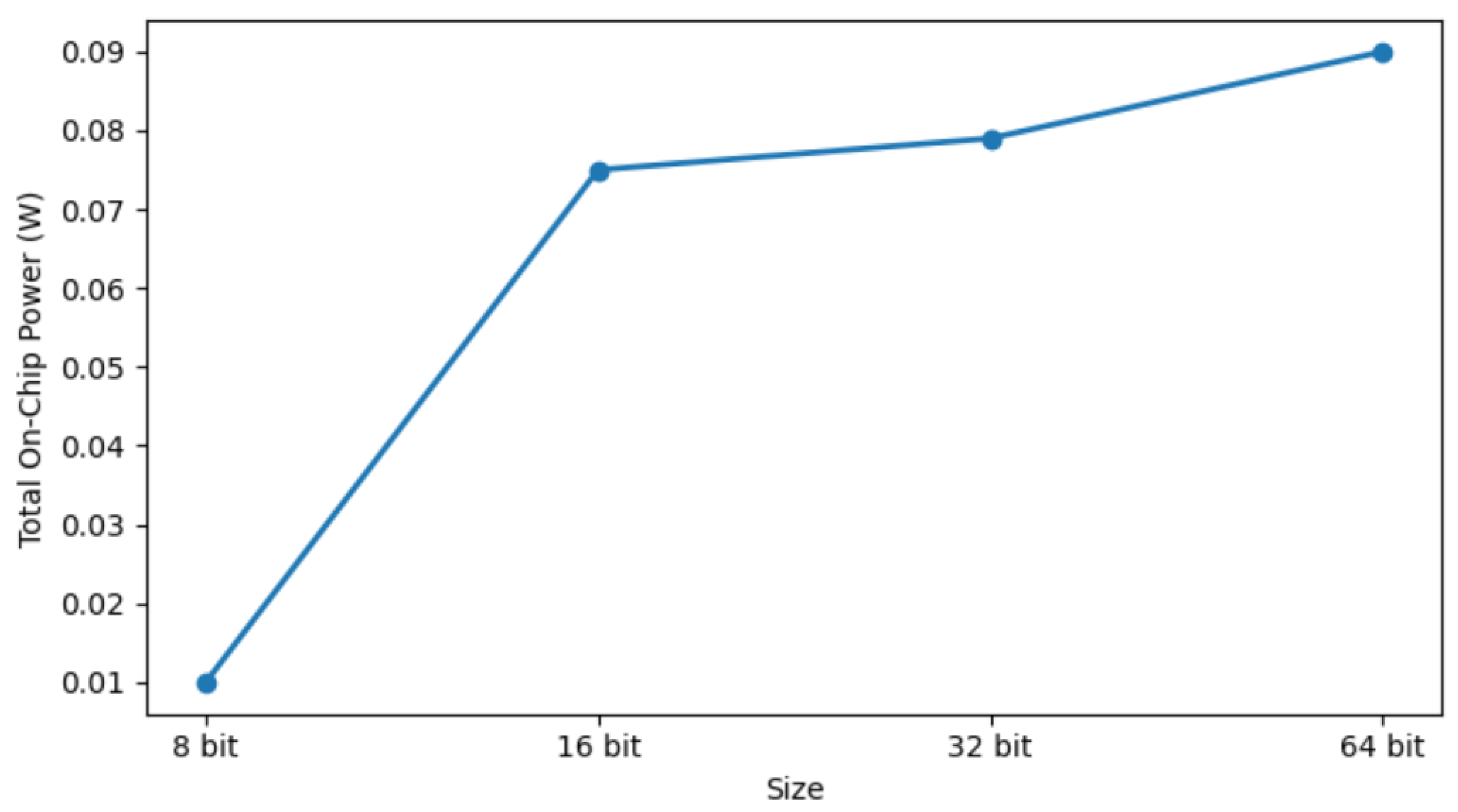

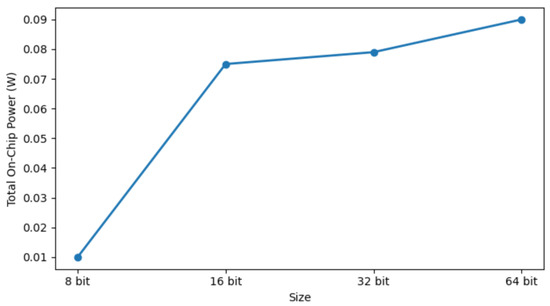

Table 2 summarizes the FPGA resource utilization for the feed-forward Arbiter PUF. As the response bit size increases, both device utilization and power consumption also rise. Figure 10 shows that total power consumption increases as the PUF response size becomes larger.

Table 2.

FPGA implementation result of feed-forward Arbiter PUF.

Figure 10.

Change in total onchip power for different PUF size.

Table 3 shows a comparison of ASIC implementation results of the proposed feed-forward PUF with earlier related work in [2]. The proposed design achieves a 40% reduction in switching power, a 38% improvement in speed, and a 43.1% decrease in area.

Table 3.

Comparison of ASIC implementation feed-forward PUF with related work. Bold values indicate superior performance.

4.2. Ldpc Implementation Results

The LDPC design was focused on a block length of n = 128 bits. Multiple code rates were generated, specifically 1/2, 2/3, and 3/4, by modifying the parity-check matrix while keeping the core encoder structure the same. After validating the functionality and synthesizing the 128-bit design, the encoder was scaled up to n = 256 bits.

Table 4 shows resource utilization, power consumption and area utilization when the LDPC encoder is implemented on Artix7 FPGA for different codeword lengths. Due to high switching activities, dynamic power increases with codeword length. Resource utilization also increases as codeword length increases.

Table 4.

FPGA implementation result of LDPC encoder for different codeword length.

Table 5 presents the FPGA implementation results of the LDPC encoder (n = 128) for three different code rates: 1/2, 2/3, and 3/4. As the code rate increases, there is a gradual rise in hardware resource utilization, particularly in the number of slice LUTs, slice registers, and I/O blocks. This increase reflects the additional logic complexity required to support higher code rates, which typically involve more complex parity generation and control structures.

Table 5.

FPGA implementation result of LDPC encoder for different code rate.

Correspondingly, the dynamic power consumption also rises from 0.052 W at a code rate of 1/2 to 0.070 W at a code rate of 3/4, indicating higher switching activity within the encoder. The total on-chip power shows a similar upward trend, although the variation remains small, demonstrating that the design remains power-efficient across all configurations.

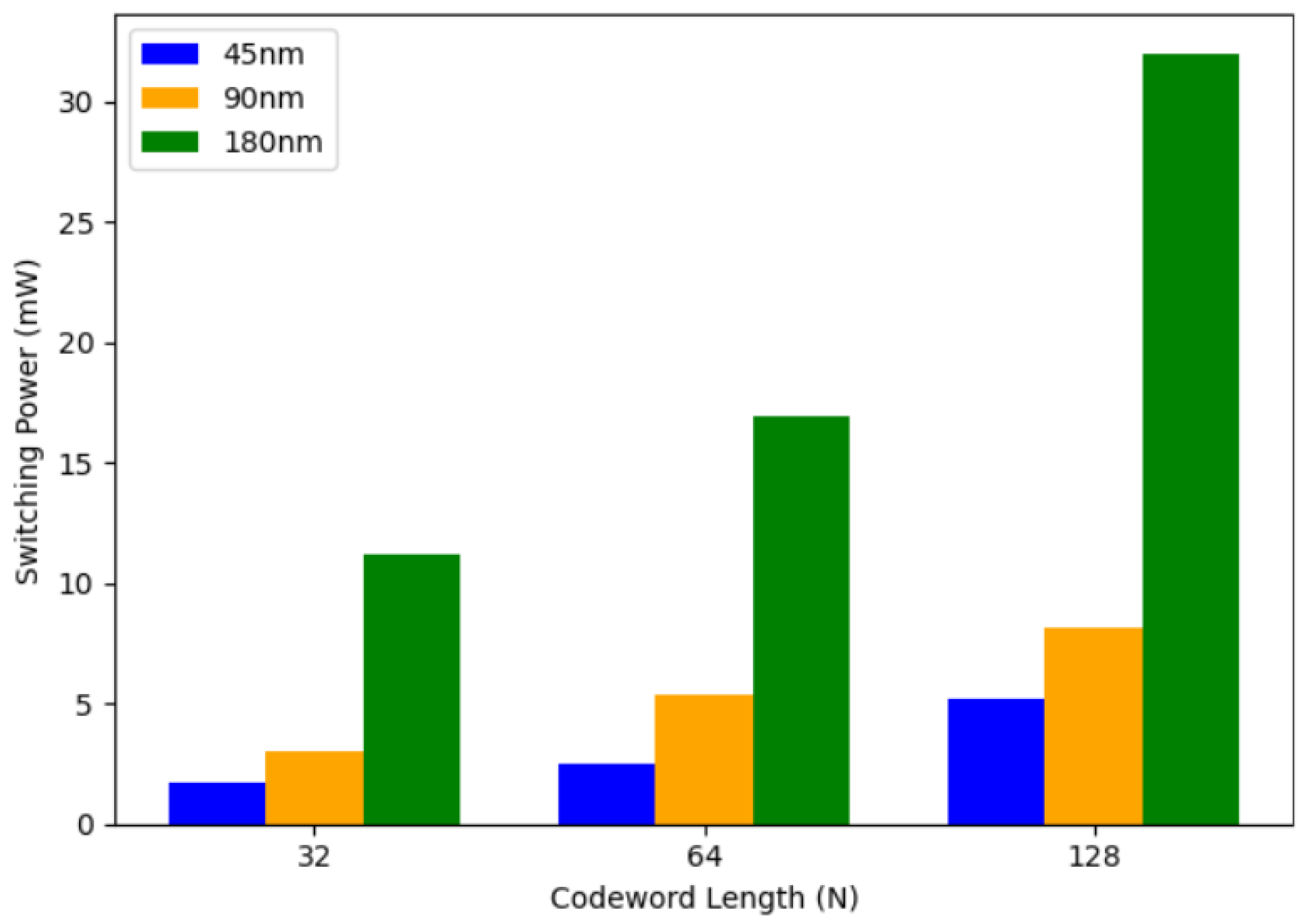

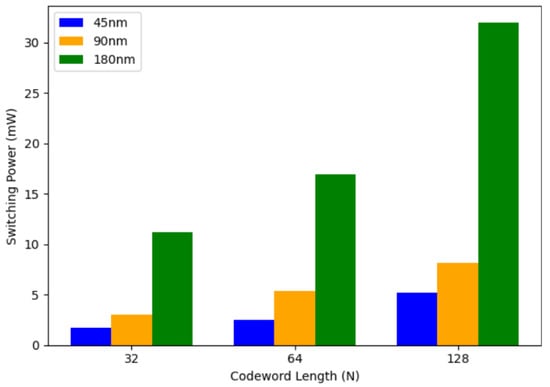

The Cadence Genus tool is used for ASIC implementation of the LDPC encoder. The observation results are summarized in Table 6. The area, speed, and dynamic power are analyzed for 45 nm, 90 nm, and 180 nm technology. Among these, the 45 nm node offers the best trade-off, providing the lowest delay and area with moderate power consumption.

Table 6.

ASIC implementation result of LDPC encoder for different codeword length.

Figure 11 shows the variation in switching power for the LDPC encoder with codeword length for different technology nodes.

Figure 11.

Variation in switching power with codeword length for LDPC encoder ASIC implementation.

4.3. Results for Proposed Scheme: Error Correction Coding on PUF

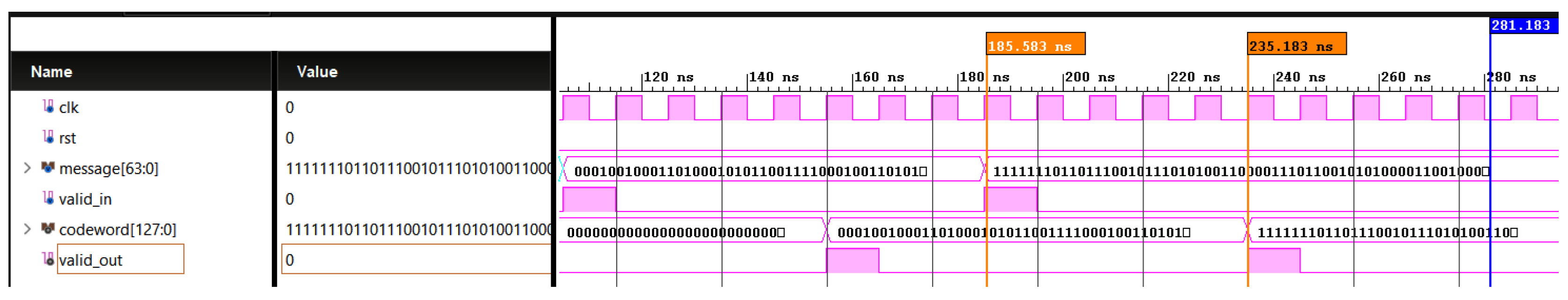

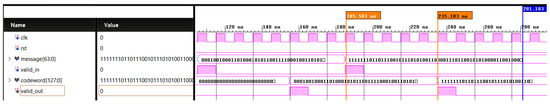

The 64-bit PUF response is encoded using LDPC to produce a 128-bit codeword, and this codeword subsequently serves as the basis for generating the 128-bit helper data. The Figure 12 shows the simulation waveform for LDPC encoding.

Figure 12.

Simulation waveform for encoding of PUF response by LDPC encoding. Message (64): 1111111011011100101110101001100001110110010101000011001000010000, Codeword (128): 11111110110111001011101010011000011101100101010000110010000100001111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111100110111101111.

In the key-reconstruction phase, decoding is performed using the bit-flipping technique and the minimum sum algorithm. In this work, the reliability evaluation was conducted on a 50 repeated response samples for each challenge. Table 7 shows a comparison of the error-correction capability of the two decoding algorithms, along with their FPGA resource utilization. While the minimum-sum decoder achieves higher reliability, the bit-flipping decoder offers advantages in resource utilization and power consumption. The switching power is compared for codeword lengths of n = 128 bits and n = 256 bits. The increase in switching power with a longer codeword length occurs because doubling the codeword length leads to higher circuit activity and greater use of combinational logic. This, in turn, results in a proportional increase in switching energy consumption. Moreover, the complexity of decoding also increases as the codeword length grows.

Table 7.

Comparison of LDPC assisted feed-forward PUF implementations using bit-flipping and minimum-sum decoding algorithm.

Table 8 presents a comparative evaluation of two hardware-accelerated LDPC decoding architectures integrated with a feed-forward PUF. Performance per watt (Gbps/W) is used as a primary evaluation metric, which is highly relevant for energy-constrained IoT endpoint devices. Our results demonstrate that the bit-flipping decoder achieves 4.2 Gbps/W, approximately 1.5 times higher than the minimum-sum decoder, which reaches 2.8 Gbps/W. This substantial improvement demonstrates that the bit-flipping approach offers superior energy efficiency, making it a more suitable choice for low-power IoT applications where reduced power consumption and compact hardware are critical. Additionally, the bit-flipping algorithm requires fewer hardware resources, resulting in better area efficiency compared to the minimum-sum implementation.

Table 8.

Comparison of performance-per-watt for LDPC assisted feed-forward PUF implementations using bit-flipping and minimum-sum decoding algorithm.

The reliability analysis in Table 9 gives the effectiveness of applying the LDPC encoding to stabilize the noisy response of the feed-forward PUF. Before applying LDPC, both decoding configurations had an average reliability of 93 % and a BER of approximately 7%. After applying LDPC coding, an improvement is observed in both cases. Table 9 also shows the effect of reliability when the code rate is changed from 1/2 to 2/3. Reliability slightly decreases when the code rate is changed from 1/2 to 2/3 because the number of parity bits is decreased. In Table 10, reliability effectiveness is analyzed for a larger codeword length of n = 256 bits. Reliability slightly increases compared to the 128-bit codeword. The reliability improves slightly for the 256-bit codeword because longer LDPC codewords allow the decoder to exploit more parity-check constraints, resulting in better error-correcting capability.

Table 9.

Reliability and BER improvement using LDPC encoding for codeword length n = 128.

Table 10.

Reliability and BER improvement using LDPC encoding for codeword length n = 256.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Arbiter PUF and feed-forward PUF are designed, and reliability is measured by checking the Hamming distance of the PUF response for the same challenge bits. Our feed-forward PUF design gives a 40% reduction in switching power, a 38% increase in speed and a 43.1% decrease in area compared to earlier related work. The proposed method can handle noisy PUF responses efficiently with the help of a powerful channel coding technique (LDPC). We could achieve a reliability of 96% by using the minimum sum algorithm for decoding and 94% using the bit-flipping algorithm. LDPC encoding is performed with different code rates to observe the variation in hardware resource utilization, power and reliability. Reliability slightly decreases when the code rate is changed from 1/2 to 2/3 because the number of parity bits is decreased. We observed that increasing the codeword length results in higher power switching because a longer codeword leads to greater circuit activity.

The complex ECC decoding method consumes large amounts of power and area and this method may not be able to handle high error rates. As future work, resource-efficient error correction coding can be designed and used to increase reliability. Future research can focus on the design of decoders with optimized FPGA/ASIC implementation for IoT devices. We will incorporate complete post-layout results in our extended future work. We can use compact machine learning models to approximate complex decoding techniques. Adaptive decoding methods enhanced by machine learning methods will improve the reliability while minimizing resource utilization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B. and S.K.N.; methodology, S.K.N. and R.A.A.S.; software, S.K.N.; validation, S.K.N., R.B. and R.A.A.S.; formal analysis, S.K.N.; investigation, R.A.A.S.; resources, S.K.N.; data curation, S.K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.N.; writing—review and editing, R.A.A.S.; visualization, S.K.N.; supervision, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Devika, K.; Bhakthavatchalu, R. FPGA implementation of programmable Hybrid PUF using Butterfly and Arbiter PUF concepts. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2312, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Bhakthavatchalu, R. FPGA based delay PUF implementation for security applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Technological Advancements in Power and Energy (TAP Energy), Kollam, India, 21–23 December 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Chaudhary, S.; Kandpal, K.; Goswami, M. Highly Reliable, Feed-Forward and Multi-Arbiter based Physical Unclonable Function for IoT security. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Smart Electronic Systems (iSES), New Delhi, India, 16–18 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hemavathy, S.; Bhaaskaran, V.K. Arbiter PUF—A review of design, composition, and security aspects. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 33979–34004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samra, S.; Sreehari, K.; Bhakthavatchalu, R. PUF based cryptographic key generation. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Ravet, India, 26–28 August 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lata, K.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. Fpga-based puf designs: A comprehensive review and comparative analysis. Cryptography 2023, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalat, M.H.; Mandal, S.; Mondal, A.; Sen, B. An efficient implementation of arbiter PUF on FPGA for IoT application. In Proceedings of the 2019 32nd IEEE International System-on-Chip Conference (SOCC), Singapore, 3–6 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, M.; Kürzinger, L.; Sigl, G. Review of error correction for PUFs and evaluation on state-of-the-art FPGAs. J. Cryptogr. Eng. 2020, 10, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, B.; Gaj, K. Selection of an error-correcting code for FPGA-based physical unclonable functions. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Field Programmable Technology (ICFPT), Melbourne, Australia, 11–13 December 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kalya, M.; Kumar, S. Low complexity LDPC error correction code for modified Anderson PUF to improve its uniformity. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 10–12 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 997–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, M.; Merli, D.; Stumpf, F.; Sigl, G. Complementary IBS: Application specific error correction for PUFs. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware-Oriented Security and Trust, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–4 June 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Puchinger, S.; Müelich, S.; Bossert, M.; Hiller, M.; Sigl, G. On error correction for physical unclonable functions. In Proceedings of the SCC 2015; 10th International ITG Conference on Systems, Communications and Coding, Hamburg, Germany, 2–5 February 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, R.; Van Herrewege, A.; Verbauwhede, I. PUFKY: A fully functional PUF-based cryptographic key generator. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, Leuven, Belgium, 9–12 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 302–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sreemohan, P.; Sebastian, N. FPGA implementation of min-sum algorithm for LDPC decoder. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICEI), Tirunelveli, India, 11–12 May 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 821–826. [Google Scholar]

- Sadek, A.M.; Hussein, A.I. Flexible FPGA implementation of Min-Sum decoding algorithm for regular LDPC codes. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Conference on Computer Engineering & Systems (ICCES), Cairo, Egypt, 20–21 December 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, R.; Tuyls, P.; Verbauwhede, I. A soft decision helper data algorithm for SRAM PUFs. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 28 June–3 July 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 2101–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahab, N.A.; Rafaiani, G.; Battaglioni, M.; Chiaraluce, F.; Baldi, M. Decentralized biometric authentication based on fuzzy commitments and blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 26–29 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasetty, V.A.; Aziz, S.M. FPGA implementation of high performance LDPC decoder using modified 2-bit min-sum algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 Second International Conference on Computer Research and Development, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–10 May 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 881–885. [Google Scholar]

- Greeshma, M.; Murugan, S. FPGA implementatıon of turbo product codes for error correctıon. In Sustainable Communication Networks and Application; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S.; Bhakthavatchalu, R.; Balasubramanian, K.; Yamuna, B.; Mishra, D.; Rajendran, S.R. Scalable FPGA Implementation of a Reliability-Based Direct Turbo Decoder for Short Block Codes. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 129588–129599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chu, C.L.; He, J.S. FPGA implementation and verification of LDPC minimum sum algorithm decoder with weight (3, 6) regular parity check matrix. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 11th International Conference on Electronic Measurement & Instruments, Harbin, China, 16–19 August 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 682–686. [Google Scholar]

- Ganorkar, A.M.; Sahula, V. Error correction using pufs for reliable key generation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Smart Electronic Systems (iSES), Warangal, India, 19–21 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 643–646. [Google Scholar]

- Kurra, A.; Nelakuditi, U.R. Design of a Reliable Current Starved Inverter Based Arbiter Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) for Hardware Cryptography. Ing. Syst. d’Inf. 2019, 24, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).