1. Introduction

Computer architecture is continually advancing with the primary goal of enhancing processor performance, efficiency, and reliability. Within this landscape, branch prediction has emerged as a vital microarchitectural technique for achieving high instruction-level parallelism (ILP) and throughput in contemporary processors. Accurate branch prediction enables speculative instruction fetching and execution without waiting for the resolution of branch outcomes, effectively minimizing stalls and the need for pipeline flushes. Conversely, frequent mispredictions can severely impact performance by instigating instruction rollbacks and elevating latency. Despite advancements in classical prediction schemes such as GAg, GAp, PAg, PAp, Gshare, and Gselect, these methods frequently grapple with the trade-off between prediction accuracy and storage overhead. While larger predictor tables tend to enhance accuracy, they also significantly increase memory requirements, posing challenges particularly in embedded systems and environments where energy constraints are paramount. This ongoing tension between achieving high accuracy and maintaining a low memory footprint represents a critical challenge in the realm of branch predictor design. The motivation behind this work is to tackle this challenge by developing a branch predictor that combines high accuracy with memory efficiency. We introduce the LXOR branch predictor, a novel lightweight design that utilizes XOR-based history encoding to mitigate aliasing effects while ensuring compact table sizes. Our evaluation of the proposed predictor against traditional methods on RISC-V processors, utilising standard benchmarking suites, demonstrates a superior balance of prediction accuracy, instructions per cycle (IPC), and reduced memory footprint.

Branch prediction [

1] is a fundamental mechanism in high-performance microprocessors, particularly in architectures featuring deep pipelines and wide instruction windows. Upon encountering a branch instruction, the processor anticipates the outcome to determine the execution path. When predictions are accurate, execution proceeds without disruption; however, a misprediction necessitates pipeline flushing, leading to stalls that significantly impair throughput. Amdahl’s Law [

2] emphasises that overall system performance is limited by its slowest component. Even if other instructions are executed rapidly, the delays introduced by mispredicted branches create bottlenecks in the pipeline. This scenario highlights the importance of precise branch prediction algorithms in mitigating stalls and enhancing overall processor performance efficiency.

As illustrated in

Figure 1 [

3,

4], a processor’s operation can be broadly categorized into five distinct stages.

During the fetch stage, it retrieves instructions from memory while updating the program counter (PC), which includes calculating branch targets when necessary. In the decode stage, the instruction is analyzed, operands are fetched, and control signals for execution are generated. The Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) carries out arithmetic, logical, and branching operations. This is followed by memory access for load/store operations, and the final stage involves writing results back to the appropriate registers.

Pipelining [

3,

4] is a technique used in processor design that segments the instruction execution process into a series of sequential stages, as shown in

Figure 2. Each stage is dedicated to handling a specific portion of the instruction set simultaneously, with one instruction being concurrently assigned to each stage. This method operates under the premise that all stages require a uniform amount of time to complete their tasks. As each time interval elapses, the instructions advance to the next stage in the pipeline. The arrangement of these sequential stages constitutes the pipeline, and processors that implement this architecture are classified as pipelined processors. This design enhances throughput by allowing multiple instructions to be in different stages of execution concurrently.

A hazard [

3,

4] in a processor is a situation where the normal instruction execution flow is disrupted, leading to delays or incorrect results. Hazards commonly occur in pipelined processors, where multiple instructions are processed simultaneously at different stages of execution.

There are three primary categories of hazards to consider:

(a) Structural Hazards: The hazard arises when two or more instructions require the same hardware resources simultaneously, resulting in stalls in the pipeline.

(b) Data Hazards: A data hazard arises when an instruction depends on the outcome of a prior instruction that has not yet finished executing. This dependency can lead to potential stalls or delays in the pipeline, as the subsequent instruction must wait for the necessary data to be available before it can proceed.

(c) Control Hazards [

5,

6] (Branch Hazards): The hazard arises from the inclusion of branch instructions within the program flow. A control hazard occurs when the processor is uncertain about which instruction to fetch next due to a branch. (e.g., if-else statements, loops, jumps, etc.)

Approximately 15% to 25% of all instructions within a program are estimated to be branch instructions [

7,

8]. Branch instructions can be categorized into three primary types: jump, call, and return, with each type further classified as either conditional or unconditional. These instructions inherently disrupt the linear flow of program execution; rather than simply incrementing the PC to proceed to the next instruction, the counter is redirected to point to a specific memory address. This deviation can introduce control hazards, leading to potential delays as the pipeline fills with instructions that may ultimately need to be discarded due to mispredictions [

1,

9,

10,

11,

12]. To mitigate the performance impacts of branch instructions, modern processor architectures frequently employ Branch Prediction (BP) techniques. BP aims to enhance instruction throughput by reducing the penalties typically associated with pipeline stalls. It entails forecasting the outcome of a branch, whether it will be taken or not, prior to its actual execution. Preemptively, the processor initiates the execution of instructions along the predicted path. When the prediction aligns with the actual outcome, it results in a branch hit, thereby optimising the utilisation of the instruction pipeline and improving overall execution efficiency. However, if the prediction is incorrect (known as a branch miss), the instructions executed from the wrong path must be discarded, and the correct instructions from the right path must be fetched into the pipeline. This incorrect prediction can lead to branch overhead, which ultimately slows down processing.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive examination of the relevant literature on both static and dynamic branch prediction methodologies.

Section 3 elaborates on the design of the proposed LXOR (Local eXclusive-OR) branch predictor, emphasising its innovative indexing scheme, which aims to reduce aliasing and improve prediction accuracy while ensuring minimal hardware overhead.

Section 4 outlines the evaluation methodology and experimental framework, presenting performance results that benchmark LXOR against established predictors, including GAg, GAp, PAg, PAp, Gshare, and Gselect, utilizing workloads from Coremark and SPEC CPU2017.

Section 5 delivers an extensive discussion and comparative analysis of LXOR’s performance across various scenarios. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing key findings, implications, and insights.

4. Results

RISC-V refers to the fifth version of Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) architecture [

25]. This instruction set architecture (ISA) is free and open, designed for simplicity, efficiency, and adaptability. Its open-source characteristics permit anyone to create, alter, and produce processors using this architecture without incurring licensing fees. RISC-V supports various standard versions, including 32-bit and 64-bit options, and offers extensions for functionalities such as floating-point operations, cryptography, and more. These extensions facilitate customization to meet the specific requirements of diverse applications and industries. A key benefit of RISC-V is its modular design, which allows implementations to include only essential components. This modularity grants flexibility and scalability, making it ideal for a broad spectrum of devices, from compact embedded systems like IoT devices to extensive servers and supercomputers.

A generic block diagram showing the 64-bit 5-stage RISC-V processor, which we have used in the experimental setup using the MARSS RISC-V emulator tool, is shown in

Figure 14.

The RISC-V processor configuration, as shown in

Figure 14, used for our experimental setup, is as follows

64-bit in-order core with a 5-stage pipeline, 1 GHz clock.

32-entry instruction and data TLBs.

32-entry 2-way branch target buffer with a simple bimodal predictor, with a 256-entry history table.

4-entry return address stack.

Single-stage integer ALU with one cycle delay.

2-stage pipelined integer multiplier with one-cycle delay per stage.

Single-stage integer divider with an eight-cycle delay.

All the instructions in FPU ALU with a latency of 2 cycles.

3-stage pipelined floating-point fused multiply-add unit with one-cycle delay per stage.

32 KB 8-way L1-instruction and L1-data caches with one cycle latency and LRU eviction.

2 MB 16-way L2-shared cache with 12-cycle latency and LRU eviction.

64-byte cache line size with write-back and write-allocate caches.

1024 MB DRAM with a base DRAM model with 75 cycles for main memory access.

In this work, all simulations were conducted on a 64-bit in-order RISC-V core with a 5-stage pipeline. We deliberately selected an in-order configuration to provide a clean and controlled environment for evaluating branch predictors, ensuring that the results accurately reflect the predictor’s behaviour without interference from out-of-order execution or other microarchitectural optimisations. While modern high-performance RISC-V implementations are typically out-of-order and superscalar, extending our study to such configurations is planned as future work.

The entire simulation was executed using the Micro-Architectural and System Simulator (MARSS-RISCV) [

26]. MARSS is a sophisticated cycle-accurate simulator engineered for in-depth modeling of computer processor internals and complete systems. This tool empowers researchers and developers to dissect the instruction processing capabilities of a processor at an exceedingly granular level, simulating each execution clock cycle. MARSS consists of two core components: a functional simulator, often QEMU, which can execute actual programs and operating systems, and a timing model that provides precise simulations of the processor’s hardware behavior. This synergy allows for thorough analyses of critical aspects such as instruction fetching, decoding, execution, memory access, and the write-back stages. Furthermore, MARSS supports full-system simulation, effectively replicating the entire computing environment, including the processor, memory hierarchy, and operating systems. The MARSS-RISC V variant is specifically designed for simulating RISC-V processor architectures, enabling exploration of diverse RISC-V core designs, memory configurations, instruction sets, and pipeline architectures within a virtualized framework before physical hardware implementation. The tool significantly enhances the ability to investigate complex architectural features like out-of-order execution, branch prediction, and cache behavior. It also accommodates multi-core simulations and supports comprehensive system testing, establishing itself as an essential asset for processor development in academia and industry. The open-source and highly configurable nature of MARSS-RISCV encourages collaborative efforts to innovate and optimize RISC-V-based systems across various applications, including embedded systems, servers, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices

Benchmarks are standardized assessments used to quantify and compare the performance characteristics of hardware, software, or entire systems. They play a critical role in evaluating the efficiency and capability of components, including CPUs, memory subsystems, storage solutions, and applications, across a range of operational conditions. Notable benchmarks utilized to gauge processor performance include CoreMark, the Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC) suite, and Whetstone, each designed to provide insights into distinct aspects of processing capabilities.

CoreMark [

27] is a well-established benchmark developed by the Embedded Microprocessor Benchmark Consortium (EEMBC) that provides a straightforward yet powerful tool for assessing processor core performance. It is particularly valuable for evaluating CPUs and microcontrollers (MCUs) within embedded systems. CoreMark incorporates a suite of key algorithms designed to measure various aspects of computational performance, including list processing for sorting and searching, matrix manipulation for critical operations, state machine logic to validate input streams, and cyclic redundancy checking (CRC) for data integrity. The benchmark’s design allows for compatibility across a broad spectrum of architectures, from 8-bit microcontrollers to 64-bit microprocessors, making it versatile for diverse embedded applications.

The SPEC CPU

® 2017 benchmark [

28,

29,

30] package represents the latest iteration of SPEC’s standardized suites for assessing compute-intensive performance metrics. This benchmark suite is engineered to rigorously evaluate a system’s processor capabilities, memory subsystem performance, and compiler efficacy. SPEC has meticulously crafted these suites to facilitate comparative analysis across a diverse array of hardware platforms, employing workloads that reflect real-world application demands. The benchmarks are available in source code form, requiring compiler commands as well as supplementary commands executed via a shell or command prompt. Additionally, the benchmark suite includes an optional metric for energy consumption assessment. The SPEC CPU

® 2017 benchmark package comprises 43 benchmarks, which are systematically categorized into four distinct suites:—The SPECspeed

® 2017 Integer and SPECspeed

® 2017 Floating Point Suites focus on measuring the execution time for individual tasks, providing insight into the latency performance of the system—The SPECrate

® 2017 Integer and SPECrate

® 2017 Floating Point Suites evaluate throughput, quantifying the number of tasks completed per unit of time, thus delivering a holistic view of the system’s performance under varying workload conditions.

This study selects eight benchmarks from the SPEC suite, specifically 500.perlbench_r, 505.mcf_r, 520.omnetpp_r, 523.xalancbmk_r, 605.mcf_s, 620.omnetpp_s, 623.xalancbmk_s, and 641.leela_s, which exhibit a higher number of branches per thousand retired instructions (PKI) [

30]. Specifically 500.perlbench_r has 202.8 branches (PKI) which means about 20.3% of all executed instructions in 500.perlbench_r are branch instructions, 505.mcf_r has 226.6 branches (PKI), 520.omnetpp_r has 220.4 branches (PKI), 523.xalancbmk_r has 238.5 branches (PKI), 605.mcf_s has 242.0 branches (PKI), 620.omnetpp_s has 220.4 branches (PKI), 623.xalancbmk_s has 238.6 branches (PKI), and 641.leela_s has 154.6 branches (PKI) [

30]. The rationale for this selection is that branch predictors are designed to anticipate the outcomes of branch instructions; consequently, benchmarks with a greater number of branches activate the predictor more frequently, thereby enhancing its influence on overall performance. This setup allows for an evaluation of the predictor’s accuracy, robustness, and efficiency under load. Furthermore, many real-world applications, such as artificial intelligence, compilers, and control systems, involve substantial branching. The use of high-PKI benchmarks ensures that the predictor is adequately prepared for these practical workloads.

Instruction per cycle (IPC): Instructions per cycle (IPC) serves as a crucial performance metric that quantifies the number of instructions a processor can execute within a single clock cycle. A higher IPC indicates improved performance and is influenced by a variety of factors, including pipeline efficiency, cache performance, and instruction-level parallelism. An ideal value of IPC is 1, which signifies that the processor, on average, completes one instruction per clock cycle, effectively utilizing its instruction pipeline. This scenario indicates minimal stalling, with instructions progressing smoothly and experiencing infrequent delays. Such performance is generally regarded as a robust baseline, particularly for scalar processors, which are designed to execute, at most, one instruction per cycle.

Accuracy (ACC): In branch prediction, accuracy is defined as the frequency with which a processor successfully anticipates the outcome of a branch instruction. It is quantified as the ratio of correct predictions to the total number of branch instructions, expressed as a percentage. Enhanced accuracy results in a reduction in instruction flushes, contributing to improved overall performance.

Misprediction (MIS): A misprediction occurs when the branch predictor of a processor inaccurately forecasts the outcome of a branch instruction. Due to this incorrect prediction, the central processing unit (CPU) speculatively fetches and begins executing instructions along the wrong path. Upon detecting the misprediction, these speculative instructions are subsequently discarded (flushed), and the appropriate path is executed instead. Although the erroneous instructions are not formally committed, the time expended on their execution results in a performance penalty. In the five-stage in-order pipeline used for evaluation, each branch misprediction incurs a fixed penalty of 3 cycles due to pipeline flushing and refetching from the correct target.

Instructions Flushed (IF): This term refers to the quantity of instructions removed from the processing pipeline before they are completed, typically due to events such as branch mispredictions or exceptions. The flushing of instructions leads to a wastage of processing time and diminishes overall performance, as the central processing unit (CPU) is required to discard these instructions and subsequently re-fetch the correct ones.

Memory footprint: The memory footprint of a branch predictor is a critical factor, as it has direct implications for the area occupied by the processor, power consumption, and overall operational efficiency. Predictors that are smaller in size require less silicon space, which simplifies design complexity and reduces manufacturing costs. Furthermore, these compact predictors facilitate faster access times, thereby enhancing instruction throughput. In power-sensitive environments, such as embedded and mobile processors, the reduction in memory usage contributes to lower energy consumption and diminished heat generation. Moreover, streamlined predictors are more amenable to scaling across multiple cores, making them particularly well-suited for contemporary multicore architectures. Consequently, optimizing the memory footprint of branch predictors is essential for achieving superior performance while adhering to system constraints.

Simulation Model: The branch prediction technique was integrated into the MARSS-RISCV simulator framework through modifications to both the predictor’s source code and its configuration settings. The implementation process involved the following steps:

Modification of Predictor Source Files: The adaptive predictor module was enhanced to integrate the new branch prediction algorithm. This involved updating the source file ‘adaptive_predictor.c‘ and its associated header file ‘adaptive_predictor.h‘ (see

Supplementary Materials [adaptive_predictor.c, adaptive_predictor.h, LXOR.c and LXOR.h]) to accommodate the additional functionality required for the novel prediction scheme.

Configuration of the Simulation Environment: MARSS-RISCV utilises a configuration script to define both architectural and microarchitectural parameters for the simulated RISC-V processor, with a particular focus on the branch prediction unit (BPU). Recent updates to this script have enabled the integration of a new branch predictor. By modifying the parameters in the ‘config64.cfg‘ file (see

Supplementary Materials [config64.cfg]), various branch prediction strategies can be instantiated within the simulator. The options include GAg, GAp, PAg, PAp, GSHARE, GSELECT, and the newly proposed LXOR, as detailed in

Table 2.

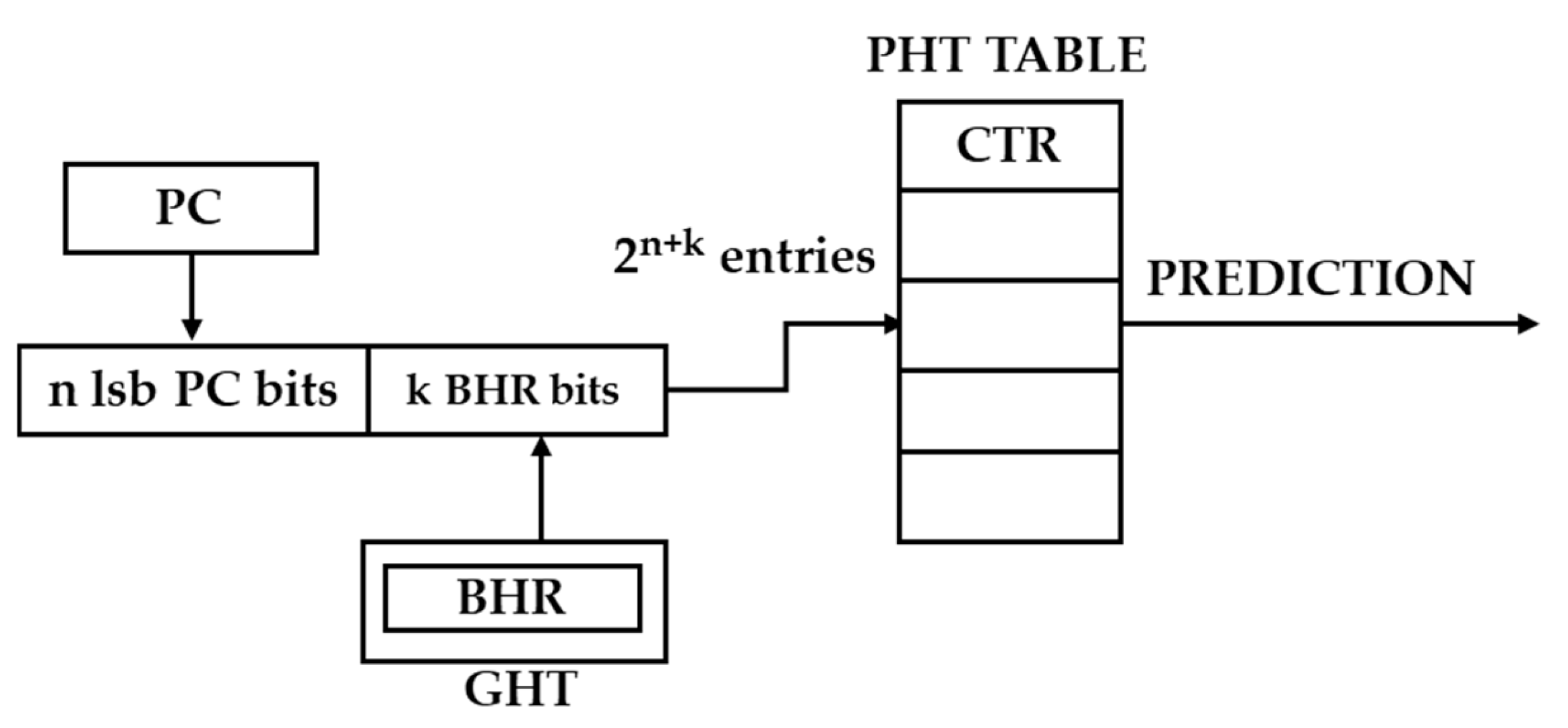

Parameter Configuration for the Proposed Predictor: To activate the novel LXOR predictor, the following parameters were defined within the configuration script:—Branch Predictor Unit (BPU) Type: Adaptive, Pattern History Table (PHT) Size: 1 entry, Global History Table (GHT) Size: Adjustable, ranging from 8 to 2048 entries, History Bits: 1 bit.

Rebuilding the Simulator: Following the updates to the predictor code and the configuration script, the simulator was recompiled using the Makefile included in the MARSS-RISCV framework. This ensured that all changes were correctly compiled and linked, maintaining integrity in the build process.

Benchmark Execution: To assess the efficacy of the proposed technique, a comprehensive suite of benchmarks was conducted on the modified simulator. The workloads utilized included SPEC CPU2017 (64-bit) and CoreMark (64-bit). The execution of these benchmarks yielded essential performance metrics for analysis, encompassing instructions per cycle (IPC), prediction accuracy, and misprediction rate.

4.1. Calculated Memory Footprints of All Predictors

To quantify the storage cost of each predictor, the calculated memory footprints are presented in

Table 3. The table reports the memory requirements for the Global History Table (GHT), Pattern History Table (PHT), and any additional structures (e.g., the Next History Table in LXOR), followed by the total storage size in bytes.

As shown in

Table 3, predictors such as GAg, Gshare, and Gselect incur relatively small footprints of about 2 KB, reflecting their simple organization. In contrast, GAp and PAp demand substantially higher storage, with PAp reaching nearly 82 KB, owing to their reliance on multiple large PHTs indexed per branch address. The proposed LXOR predictor demonstrates a balanced design, requiring only 2096 bytes—just slightly higher than GAg and Gshare—while integrating its Next History Table within the PHT. This indicates that LXOR maintains a compact memory footprint while offering enhanced prediction accuracy compared to conventional designs.

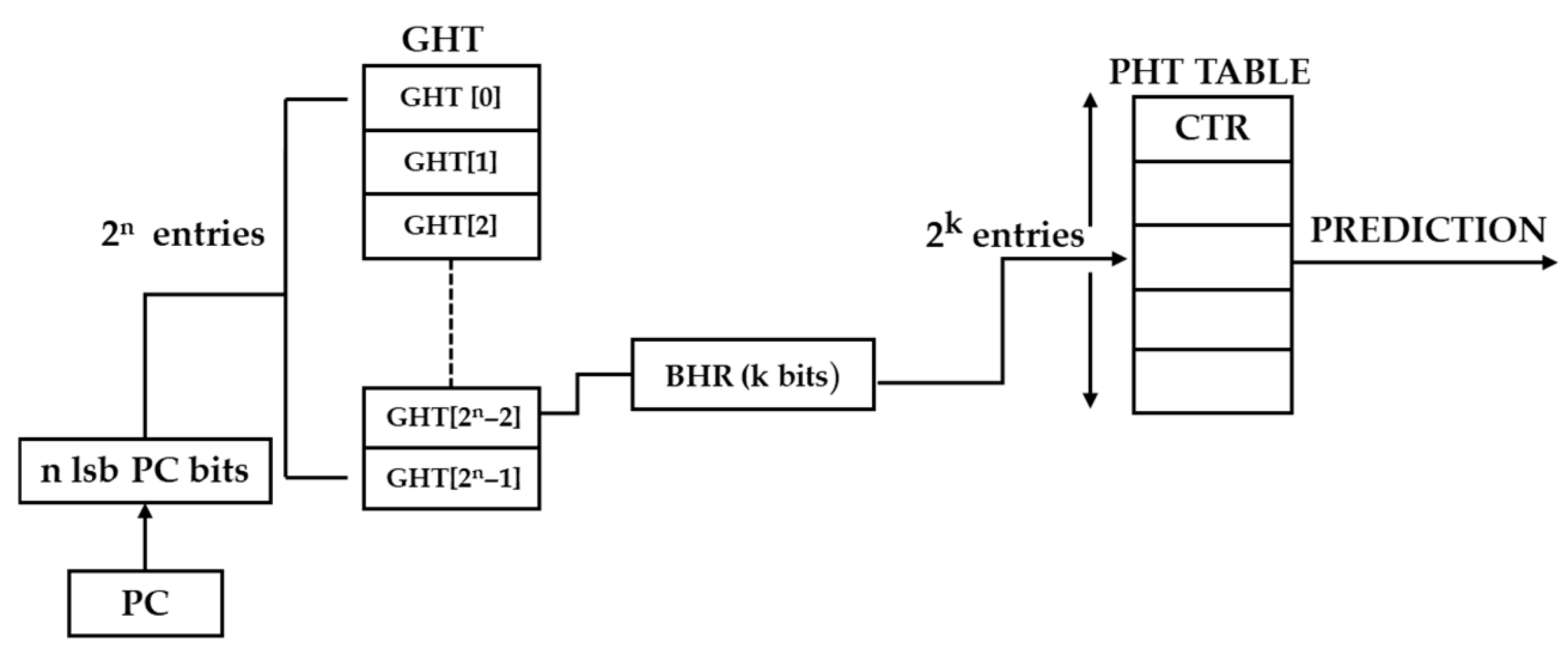

4.2. Performance of GAg Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 4 summarizes the performance metrics for the GAg branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the sizes of the Global History Table (GHT) and the Pattern History Table (PHT) were both set to 1. At the same time, the number of history bits was systematically varied from 1 to 9 to analyze its effect on prediction accuracy as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

4.3. Performance of GSHARE Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 5 summarizes the performance metrics for the GSHARE branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the sizes of the Global History Table (GHT) and the Pattern History Table (PHT) were both set to 1, aliasing function set to XOR. At the same time, the number of history bits was systematically varied from 1 to 9 to analyze its effect on prediction accuracy as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

4.4. Performance of GSELECT Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 6 summarizes the performance metrics for the GSHARE branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the sizes of the Global History Table (GHT) and the Pattern History Table (PHT) were both set to 1, the aliasing function set to AND, while the number of history bits was systematically varied from 1 to 9 to analyze its effect on prediction accuracy as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

4.5. Performance of GAp Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 7 summarizes the performance metrics for the GAp branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the size of the Global History Table (GHT) is set to 1, the number of History bits is set to 1, and the Pattern History Table (PHT) is varied from 8 to 2048 to analyse its effect on prediction accuracy, as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

4.6. Performance of PAg Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 8 summarizes the performance metrics for the PAg branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the size of the Global History Table (GHT) is varied from 8 to 2048, the Number of History bits is set to 1, and the Pattern History Table (PHT) is set to 1, to analyse its effect on prediction accuracy, as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

4.7. Performance of PAp Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 9 summarizes the performance metrics for the PAp branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the size of the Global History Table (GHT) is set to 2048, the number of History bits is set to 1, and the Pattern History Table (PHT) is varied from 8 to 2048 to analyse its effect on prediction accuracy, as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

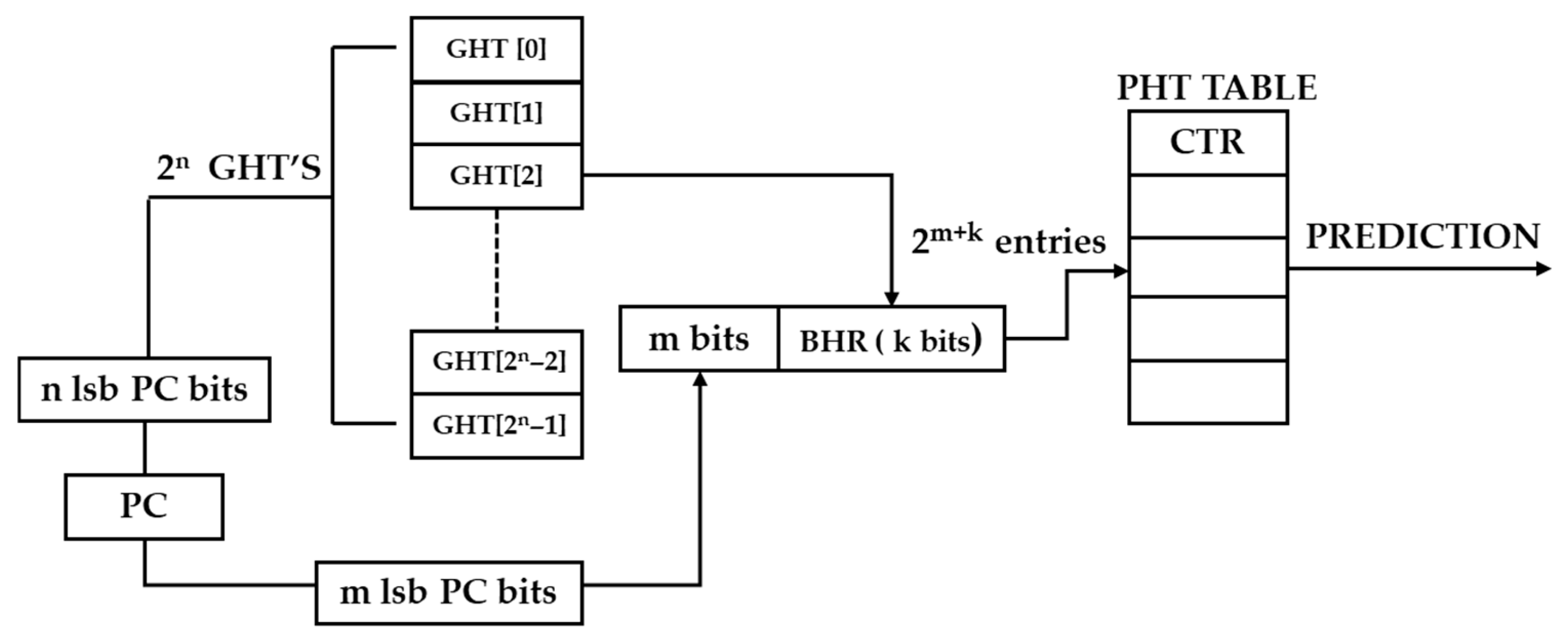

4.8. Performance of LXOR Branch Predictor Using SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark Benchmarks

Table 10 summarizes the performance metrics for the LXOR branch predictor evaluated using the SPEC CPU2017 and Coremark benchmarks on a 64-bit RISC-V architecture. In this experimental setup, the size of the Global History Table (GHT) is varied from 8 to 2048, the Number of History bits is set to 1, and the Pattern History Table (PHT) is set to 1, to analyse its effect on prediction accuracy, as described in

Table 2. The simulator was run for each configuration, and the results reflecting the optimal performance for each benchmark are presented in the table.

5. Discussion

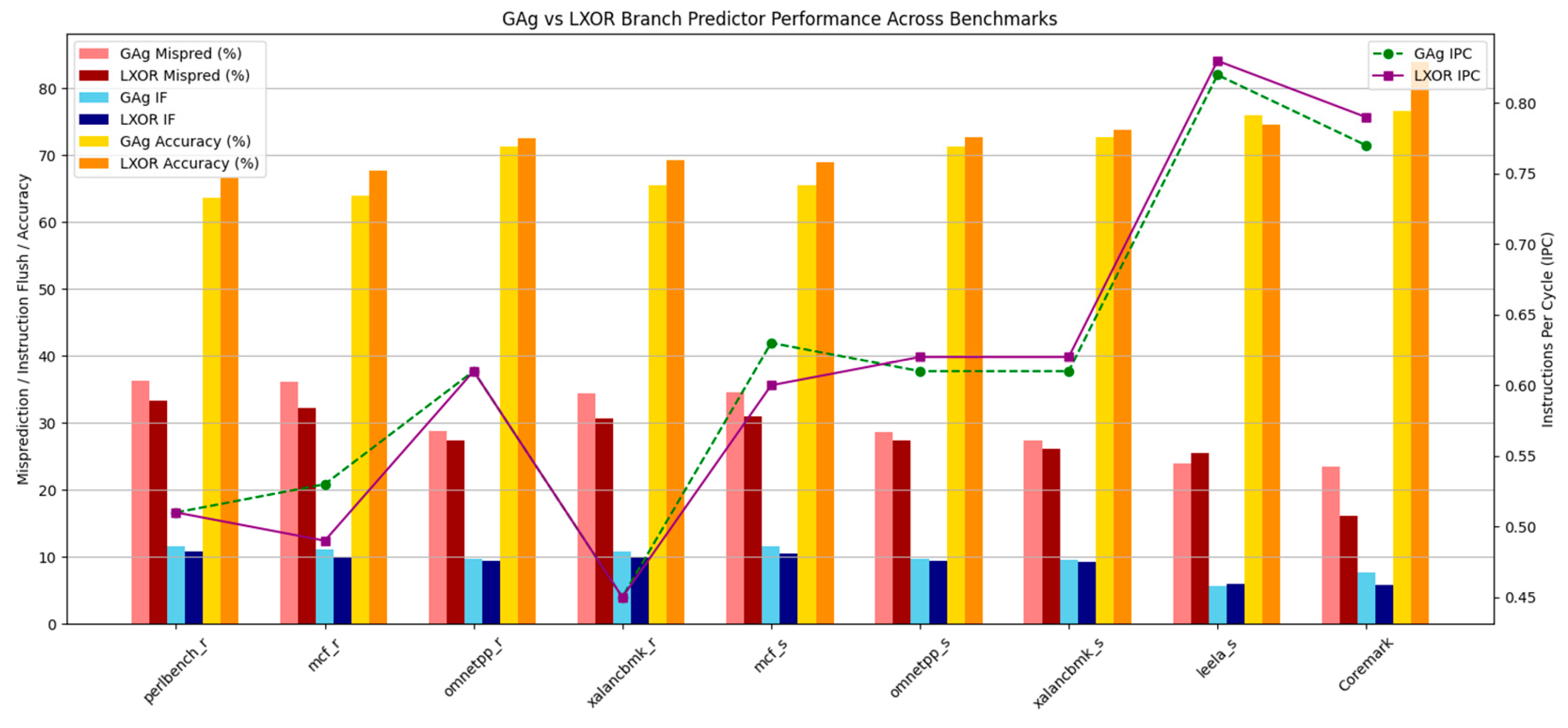

5.1. Performance Analysis of LXOR Branch Predictor Against GAg Branch Predictor

Branch prediction plays a crucial role in achieving optimal performance in modern superscalar processors, particularly in deeply pipelined architectures, where inaccuracies can lead to significant pipeline stalls and inefficient use of instruction fetch cycles. This study aims to evaluate and compare the performance of the conventional GAg (Global Adaptive with Global History) branch predictor against a newly proposed LXOR branch predictor within a 64-bit RISC-V architecture as shown in

Figure 15.

The evaluation methodology uses a combination of synthetic benchmarks and real-world applications. Performance metrics include Instructions Per Cycle (IPC), prediction accuracy, misprediction rate, instructions flushed (IF), and memory footprint. The benchmarks consist of Coremark (64-bit) and key integer and floating-point workloads from the SPEC CPU2017 suite (namely perlbench_r, mcf_r, omnetpp_r, xalancbmk_r, mcf_s, omnetpp_s, xalancbmk_s, and leela_s).

The graph in

Figure 15 was constructed using the data presented in

Table 4 and

Table 10. Throughout the examined benchmarks, the LXOR predictor consistently exhibited a lower frequency of instruction flushes when compared to the GAg predictor. For instance, in the perlbench_r benchmark, the GAg predictor recorded 11.67% instruction flushes, whereas the LXOR predictor achieved a reduction to 10.83%. Similarly, in the mcf_r, omnetpp_r, xalancbmk_r, mcf_s, and omnetpp_s benchmarks, flush counts declined from 11.21% (GAg) to 10.11% (LXOR), 9.80% to 9.50%, 10.85% to 9.87%, 11.56% to 10.50%, and 9.81% to 9.49%, respectively. Notably, the Coremark results further underscore the practical efficiency of the LXOR predictor in embedded scenarios, where the flush count diminished from 7.66% (GAg) to 5.83% (LXOR). This decrease not only indicates fewer wasted cycles but also reflects a more stable execution pipeline. Such a reduction in instruction flushes has a direct impact on the processor’s ability to sustain high instruction throughput and is attributed to an improvement in prediction accuracy.

Prediction accuracy serves as a critical performance metric for assessing the effectiveness of branch predictors. It is directly linked to the frequency of pipeline flushes and indirectly correlates with IPC. The LXOR predictor consistently surpasses the GAg predictor in terms of prediction accuracy across nearly all benchmarks. For example:—In the perlbench_r benchmark, the LXOR predictor achieved an accuracy of 66.62%, compared to 63.64% for the GAg predictor. In the mcf_r benchmark, the LXOR demonstrated an improvement from 63.92% to 67.74%. In the xalancbmk_s, mcf_s, and omnetpp_s benchmarks, accuracy improved from 72.67% (GAg) to 73.83% (LXOR), from 65.46% to 69%, and from 71.34% to 72.65%, respectively. In the Coremark benchmark, which is indicative of performance in real-time embedded systems, the LXOR achieved a significantly higher accuracy of 83.92%, compared to 76.57% for the GAg predictor. This enhancement in prediction accuracy underscores the architectural advantages of the LXOR predictor, particularly its utilization of local history through the XOR transformation of Branch History Register (BHR) bits. By employing XOR gates to transform branch history and indexing the PHT more effectively, the LXOR predictor minimizes aliasing and enhances prediction granularity.

The misprediction rate is inversely related to prediction accuracy and significantly impacts performance-critical workloads characterized by high control flow divergence. The LXOR predictor consistently demonstrates a lower misprediction rate across various benchmarks. In the xalancbmk_r benchmark, the LXOR predictor exhibits a misprediction rate of 30.68%, in contrast to GAg’s rate of 34.43%. For the omnetpp_s, xalancbmk_s, and mcf_s benchmarks, the LXOR misprediction rates decrease to 27.35%, 26.17%, and 31%, respectively, compared to GAg’s rates of 28.66%, 27.33%, and 34.54%. In the Coremark benchmark, LXOR achieves a substantial reduction in mispredictions from 23.43% to 16.08%, resulting in an absolute improvement of 7.35%. These improvements directly contribute to fewer pipeline stalls and enable the processor to maintain higher throughput levels. The effectiveness of the LXOR predictor in minimizing mispredictions is primarily attributed to its utilization of fine-grained local histories paired with adaptive XOR indexing.

Instructions Per Cycle (IPC) serves as a macro-level performance indicator, encapsulating the overall efficiency of instruction execution. This metric is directly influenced by the accuracy of branch prediction and the frequency of instruction flushes. Across various benchmarks:—In the xalancbmk_s benchmark, the LXOR configuration achieves an IPC of 0.62, surpassing the GAg configuration’s IPC of 0.61—a modest yet significant improvement. In the omnetpp_s benchmark, LXOR similarly records an IPC of 0.62, slightly exceeding GAg’s IPC of 0.61. The most pronounced enhancement is observed in the Coremark benchmark, where the IPC improved from 0.77 with GAg to 0.79 with LXOR. This illustrates superior instruction utilization and improved pipeline flow. While the IPC enhancements may be modest in certain instances, they are consistent with observed improvements in prediction accuracy and reductions in instruction flushes. Furthermore, the stability and consistency of LXOR across a diverse range of workloads underscore its scalability and suitability for both general-purpose and embedded processors.

The memory footprint represents a critical consideration in the design of hardware predictors, particularly within embedded and low-power systems. Although the LXOR method employs a larger GHT of 2048 bytes, compared to only 16 bytes utilized by GAg, it effectively minimizes the size of the PHT through a more efficient indexing technique. Consequently, the overall memory footprint remains comparable: 2096 bytes for LXOR in contrast to 2080 bytes for GAg, reflecting a marginal increase of merely 0.76%. This trade-off is particularly advantageous, given the substantial improvements in prediction accuracy and IPC. Moreover, the additional hardware requirements for implementing XOR logic are negligible in contemporary silicon designs and are well justified by the resulting improvements in execution throughput and prediction reliability. Furthermore, LXOR successfully circumvents the significant memory overhead associated with more intricate predictors, such as GAp or PAp, which tend to exhibit poor scalability when employed with extensive predictor tables.

Hence, the proposed LXOR branch predictor demonstrates a marked improvement over the traditional GAg predictor when evaluated against several critical benchmarks and performance metrics. With only a minimal increase in hardware cost, it achieves significantly higher accuracy, reduced misprediction rates, and enhanced IPC across both synthetic (Coremark) and real-world (SPEC CPU2017) workloads. The LXOR design capitalizes on the advantages of utilizing local history patterns combined with XOR-based indexing to minimize aliasing and refine the modeling of branch behavior. These advancements position LXOR as an attractive option for future RISC-V processors, particularly those aimed at optimizing performance per watt in mobile, Internet of Things (IoT), and edge computing environments.

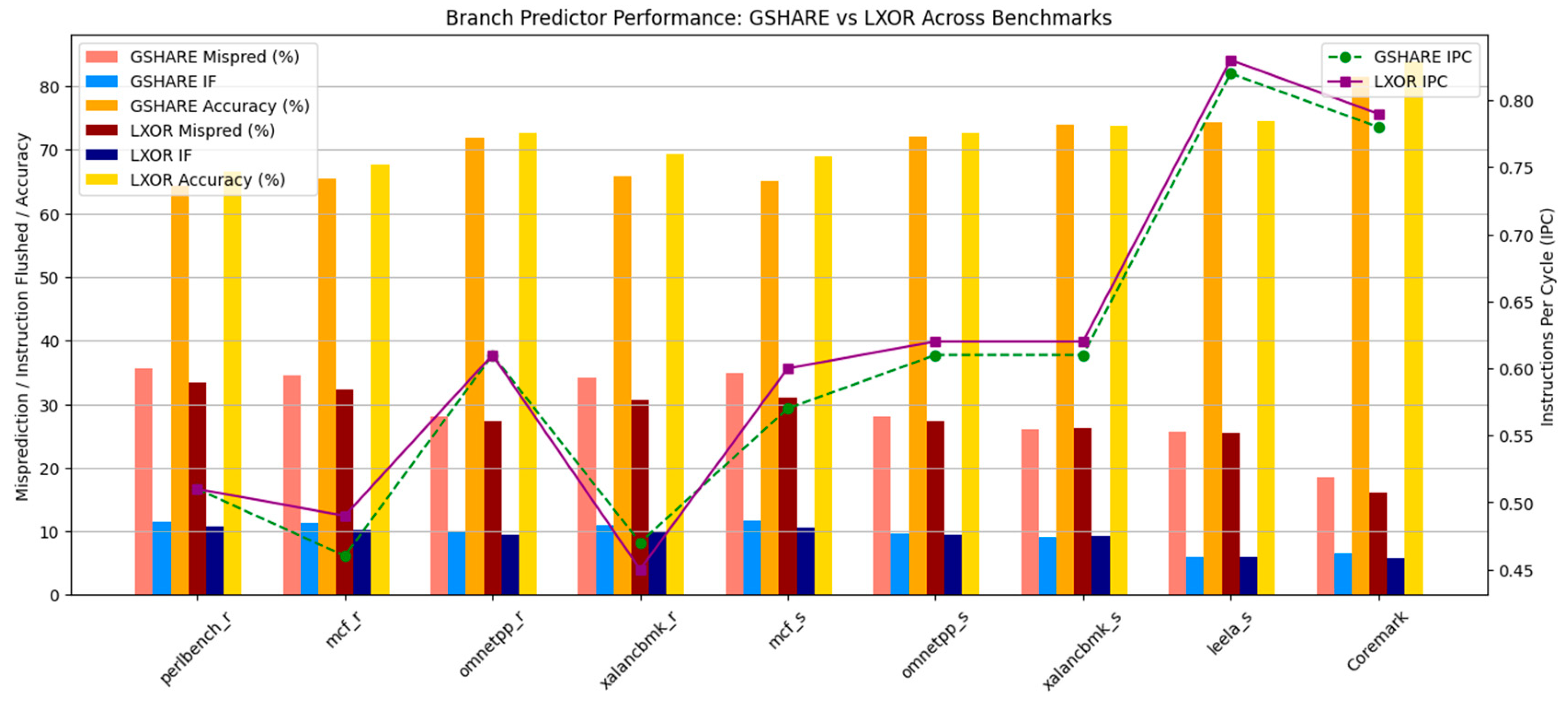

5.2. Performance Analysis of LXOR Branch Predictor Against GSHARE Branch Predictor

The LXOR predictor consistently demonstrates marginally superior IPC across nearly all benchmarks when compared to the GSHARE predictor, as shown in

Figure 16.

The graph in

Figure 16 was constructed using the data presented in

Table 5 and

Table 10. In the Coremark benchmark, LXOR attains an IPC of 0.79, slightly surpassing Gshare’s IPC of 0.78. The distinction in performance becomes increasingly evident across several SPEC benchmarks. In the mcf_s benchmark, for example, the IPC rises from 0.57 with GSHARE to 0.60 with LXOR. Similarly, in leela_s, LXOR achieves an IPC of 0.83, in contrast to Gshare’s 0.82. Notably, both omnetpp_s and xalancbmk_s benchmarks reveal an IPC of 0.62 for LXOR, while GSHARE maintains an IPC of 0.61. These improvements, while modest in numerical value, indicate enhanced pipeline utilization and a reduction in stalling, attributed to the more effective branch resolution offered by the LXOR scheme.

The proposed LXOR predictor exhibits consistently superior prediction accuracy across all tested benchmarks. In the Coremark benchmark, LXOR achieves an impressive accuracy of 83.92%, while GSHARE achieves only 81.48%, representing a significant improvement of over 3%. Similarly, in the xalancbmk_r benchmark, the accuracy improves from 65.76% with Gshare to 69.32% with LXOR, and in perlbench_r, the accuracy increases from 64.30% to 66.62%. The most significant enhancements are observed in the mcf_r and mcf_s benchmarks, where LXOR’s accuracy rises to 67.74% and 69.00%, respectively, compared to Gshare’s 65.44% and 65.09%. These improvements underscore LXOR’s capability in capturing local branch behavior through its innovative combination of local history tracking and XOR-based pattern generalization.

Comparatively, the LXOR approach demonstrates a reduction in mispredictions when juxtaposed with GSHARE. In the case of Coremark, the misprediction rate under LXOR is recorded at 16.08%, in contrast to 18.52% with GSHARE. Similarly, in the omnetpp_r benchmark, LXOR reduces mispredictions to 27.4%, compared to Gshare’s rate of 28.14%. Notable improvements are also evident in the xalancbmk_s and leela_s benchmarks, where LXOR achieves a misprediction rate of 26.17% and 25.47%, respectively, relative to Gshare’s figures of 26.00% and 25.62%. Although these enhancements may appear incremental in certain benchmarks, they are of significant importance for high-performance systems, as even marginal reductions in mispredictions can dramatically influence overall execution time and power consumption.

The LXOR predictor exhibits reduced instruction flush counts across the majority of benchmarks, thereby contributing to enhanced IPC and diminished performance penalties. For example, in the Coremark benchmark, the instruction flush count is observed to decline from 6.59% (using GSHARE) to 5.83% (using LXOR). Similarly, in the mcf_r benchmark, the count decreases from 11.25% to 10.11%. Additional reductions are noted in xalancbmk_r, where the count falls from 10.99% to 9.87%, and in mcf_s, where it reduces from 11.66% to 10.50%. These reductions are consistent with the increased accuracy of LXOR and underscore its effectiveness in minimizing both the frequency and impact of control hazards within the pipeline.

A critical consideration in embedded systems is the memory overhead associated with the predictor. Both the GSHARE and LXOR predictors are engineered with efficiency as a primary objective. The GSHARE predictor utilizes a total memory of 2080 bytes, which consists of a 16-byte GHT and a 2064-byte PHT. Conversely, the LXOR predictor employs a slightly higher memory capacity of 2096 bytes. This predictor incorporates a 2048-byte GHT and a 48-byte PHT, which includes the integrated Next History Table (NHT). Despite the marginal increase in memory usage of approximately 0.76%, the significant improvements in prediction accuracy, IPC, and the reduction in flushes substantiate this trade-off, particularly in workloads that are sensitive to performance. Hence, the LXOR predictor demonstrates superior performance compared to GSHARE across all critical metrics, including IPC, accuracy, misprediction rate, and instruction flush count, while maintaining a nearly identical memory footprint. The primary advantage of the LXOR predictor is its adaptive utilization of local history combined with effective generalization through XOR-based indexing. This approach enables it to manage diverse and irregular branch patterns more efficiently than GSHARE, which depends solely on global history. The enhancements are particularly evident in complex benchmarks such as xalancbmk_r and mcf_r, which are characterized by their significant control-flow dependencies. Moreover, the commendable performance of LXOR in Coremark—a benchmark representative of embedded workloads highlights its practical relevance for Internet of Things (IoT) devices, edge computing systems, and real-time embedded controllers.

5.3. Performance Analysis of LXOR Branch Predictor Against GSELECT Branch Predictor

A comparative analysis of two predictors, namely the LXOR and GSELECT, reveals that the LXOR Predictor consistently demonstrates superior performance across all benchmarks analysed, as shown in

Figure 17.

The graph in

Figure 17 was constructed using the data presented in

Table 6 and

Table 10. In the Coremark benchmark, the LXOR model resulted in the flushing of only 5.83% instructions, in contrast to GSELECT, which flushed 7.54% instructions, yielding a significant reduction of 22.7%. In the SPEC CPU2017 workloads, specifically omnetpp_s and xalancbmk_s, LXOR achieved 9.49% and 9.25% flushed instructions, respectively. In comparison, GSELECT recorded 11.05% and 10.23% flushed instructions, thus reflecting a consistent reduction in the range of 10% to 15%. The most notable improvement was observed in the mcf_r, omnetpp_r, xalancbmk_r, and mcf_s benchmarks, where LXOR reduced the number of instructions flushed to 10.11%, 9.5%, 9.87%, and 10.5%, respectively, as compared to GSELECT’s 11.29%, 11.04%, 10.9%, and 11.3%. Although these differences appear marginal, they indicate a stable performance across the various benchmarks. This reduction in flushed instructions suggests fewer pipeline stalls and an enhancement in processor throughput, which is particularly advantageous for workloads characterized by frequent branching patterns.

The LXOR approach shows better prediction accuracy compared to GSELECT across all tested benchmarks: In the Coremark benchmark, LXOR achieved an impressive accuracy of 83.92%, well above GSELECT’s 76.92%. For SPEC workloads like xalancbmk_s and omnetpp_s, LXOR recorded accuracies of 73.83% and 72.65%, respectively, exceeding GSELECT’s 70.47% and 67.76%. Additionally, in challenging integer benchmarks such as mcf_r and perlbench_r, LXOR demonstrated improved prediction consistency, with accuracies of 67.74% and 66.62%, compared to GSELECT’s 64.05% and 63.41%. This steady increase in prediction accuracy reduces pipeline disruptions and is linked to better IPC. The utilization of the LXOR predictor, which incorporates local history and XOR-complement indexing, demonstrates a significant advantage in minimizing mispredictions. In the Coremark benchmark, LXOR achieved a misprediction rate of merely 16.08%, markedly lower than GSELECT, which recorded a misprediction rate of 23.08%. Within the SPEC benchmarks, LXOR consistently maintained a lower misprediction rate across various tests. For example, in the omnetpp_s and xalancbmk_s benchmarks, LXOR displayed misprediction rates of 27.35% and 26.17%, respectively, in contrast to GSELECT’s rates of 32.24% and 29.53%. Furthermore, in integer-intensive workloads, such as mcf_r, LXOR produced a misprediction rate of 32.26%, demonstrating an improvement over GSELECT’s rate of 35.95%. A reduced misprediction rate directly correlates with fewer pipeline flushes and enhanced instruction-level parallelism, thereby contributing to improved overall CPU performance.

The LXOR predictor demonstrates consistent improvements in IPC as follows: LXOR achieves an IPC of 0.79 in the Coremark benchmark, surpassing GSELECT’s performance of 0.77. In the benchmarks omnetpp_s, xalancbmk_s, and leela_s, LXOR attains IPC values of 0.62, 0.62, and 0.83, respectively, all of which exceed the corresponding GSELECT values of 0.6, 0.6, and 0.81. Notably, in a compute-intensive benchmark such as omnetpp_r, LXOR produces an IPC of 0.61, outperforming GSELECT, which registers an IPC of 0.6.

The GSELECT and LXOR predictors exhibit nearly comparable memory requirements, with LXOR demonstrating a marginally higher efficiency. Specifically, GSELECT allocates a total of 2080 bytes, comprising 16 bytes for the Global History Table (GHT) and 2064 bytes for the PHT. In contrast, LXOR employs a larger GHT of 2048 bytes but only requires 48 bytes for the PHT, culminating in a total footprint of 2096 bytes. Moreover, LXOR incorporates a compact Next History Table (NHT) directly within the PHT, thereby eliminating the necessity for extensive auxiliary structures. The minimal difference in memory consumption, approximately 0.76%, is compensated by LXOR’s considerable enhancements in prediction accuracy and IPC. Consequently, LXOR achieves a superior performance-to-memory ratio, which is particularly advantageous in environments where memory resources are constrained.

The proposed LXOR branch predictor presents a viable alternative to conventional global-history-based predictors, such as GSELECT. Its effectiveness is demonstrated through consistent enhancements in IPC, prediction accuracy, and pipeline efficiency across both embedded and general-purpose benchmark suites. Considering its minimal memory overhead alongside high performance, LXOR is particularly well-suited for implementation in contemporary RISC-V processors. This is especially relevant for systems aimed at performance-sensitive and power-constrained applications, including mobile system-on-chips (SoCs), embedded control systems, and real-time applications.

5.4. Performance Analysis of LXOR Branch Predictor Against GAp Branch Predictor

The benchmark suite analysis reveals that both GAp and LXOR exhibit competitive IPC values; however, LXOR demonstrates a slight advantage over GAp in memory-intensive or control-intensive workloads, such as mcf_s, xalancbmk_s, and omnetpp_s, as shown in

Figure 18.

The graph in

Figure 18 was constructed using the data presented in

Table 7 and

Table 10. For example, in the mcf_s workload, LXOR achieves an IPC of 0.60, compared to GAp’s 0.56, indicating enhanced throughput for LXOR in memory-intensive scenarios. Similarly, in the xalancbmk_s assessment, LXOR records an IPC of 0.62, surpassing GAp’s IPC of 0.61. It is important to note that in the Coremark benchmark, LXOR registers a minor decrease with an IPC of 0.79, while GAp attains 0.80. This reduction is minimal and falls within acceptable margins, thereby affirming LXOR’s competitiveness even in simpler workload contexts.

LXOR consistently demonstrates improved or comparable accuracy when evaluated against GAp. In the Coremark benchmark, GAp exhibits a marginally higher accuracy of 86.63% compared to LXOR’s 83.92%. However, in more intricate SPEC workloads, LXOR either matches or slightly surpasses GAp. For instance in the xalancbmk_r workload, LXOR achieves 69.32%, surpassing GAp’s 69.01%. In perlbench_r, LXOR records 66.62% while GAp tallies 66.01%. For mcf_r, LXOR registers 67.74%, compared to GAp’s 67.49%. In mcf_s, LXOR reaches 69%, whereas GAp records 66.52%. Lastly, in leela_s, GAp attains 76.91%, while LXOR achieves a comparable 74.53%. The emphasis on local history within LXOR facilitates a more nuanced modeling of branch behavior, particularly advantageous in multi-path execution environments.

In the mcf_s benchmark, LXOR exhibits a lower misprediction rate of 31%, compared to GAp’s 33.48%. Comparable improvements are noted in the xalancbmk_s benchmark, where LXOR achieves a misprediction rate of 26.17% in contrast to GAp’s 26.12%, and in the omnetpp_s benchmark, with LXOR at 27.35% versus GAp at 27.4%. There is a marginal increase in mispredictions for LXOR in the Coremark benchmark, registering at 16.08% as opposed to GAp’s 13.37%. In summary, LXOR demonstrates reduced volatility in misprediction rates across diverse workloads, indicating a greater degree of generalizability.

In three major benchmarks (perlbench_r, xalancbmk_r, and mcf_s), the LXOR algorithm demonstrates a superior capability in producing fewer flushed instructions compared to the GAp algorithm. This observation serves as a compelling indication of LXOR’s enhanced branch prediction capabilities within complex, data-intensive codebases. In particular, benchmarks such as mcf_r, omnetpp_r, xalancbmk_s, and omnetpp_s, the disparity between GAp and LXOR is minimal, typically ranging from 0.05 to 0.15 instructions flushed. This difference lies within the margins of statistical noise, suggesting that LXOR exhibits nearly equivalent efficiency in those contexts. Notably, despite its reduced memory footprint, LXOR achieves instruction flush performance that is comparable to or superior to that of GAp. In branch-heavy workloads, including mcf_s and xalancbmk_r, which closely emulate real-world software behavior, LXOR effectively diminishes the frequency of instruction flushes. This reduction leads to improved pipeline utilization and a decrease in operational stalls.

The GAp predictor features a substantial PHT of 49,152 bytes and a GHT of 16 bytes, resulting in an overall memory footprint of 49,168 bytes. In contrast, the LXOR predictor employs a smaller Global History Table of 2048 bytes and a compact PHT of 48 bytes, alongside a nested history structure within the PHT, thereby culminating in a total footprint of merely 2096 bytes. The LXOR predictor achieves an impressive approximate 96% reduction in memory footprint, making it particularly advantageous for deployment in areas with constraints on area and power. This characteristic positions the LXOR predictor as an optimal solution for environments such as the Internet of Things (IoT), edge computing, and mobile platforms. Importantly, the compact design of the LXOR predictor does not compromise its accuracy or IPC, establishing it as an efficient alternative to traditional predictors such as GAp.

The proposed LXOR branch predictor demonstrates a considerable advantage over the traditional GAp predictor across various evaluation metrics. Although both predictors exhibit comparable performance in straightforward benchmarks, LXOR consistently surpasses GAp in complex SPEC workloads concerning IPC, misprediction rate, and overall prediction accuracy. Notably, LXOR achieves these enhancements while maintaining a significantly smaller memory footprint, utilizing approximately 2 KB compared to GAp’s 49 KB. This characteristic makes LXOR particularly suitable for low-power and resource-constrained systems. Furthermore, LXOR minimizes instruction flushes in several critical benchmarks, which reflects improved control-flow prediction and reduced pipeline disruptions. In summary, LXOR presents a balanced, memory-efficient, and performance-effective solution for next-generation RISC-V processors.

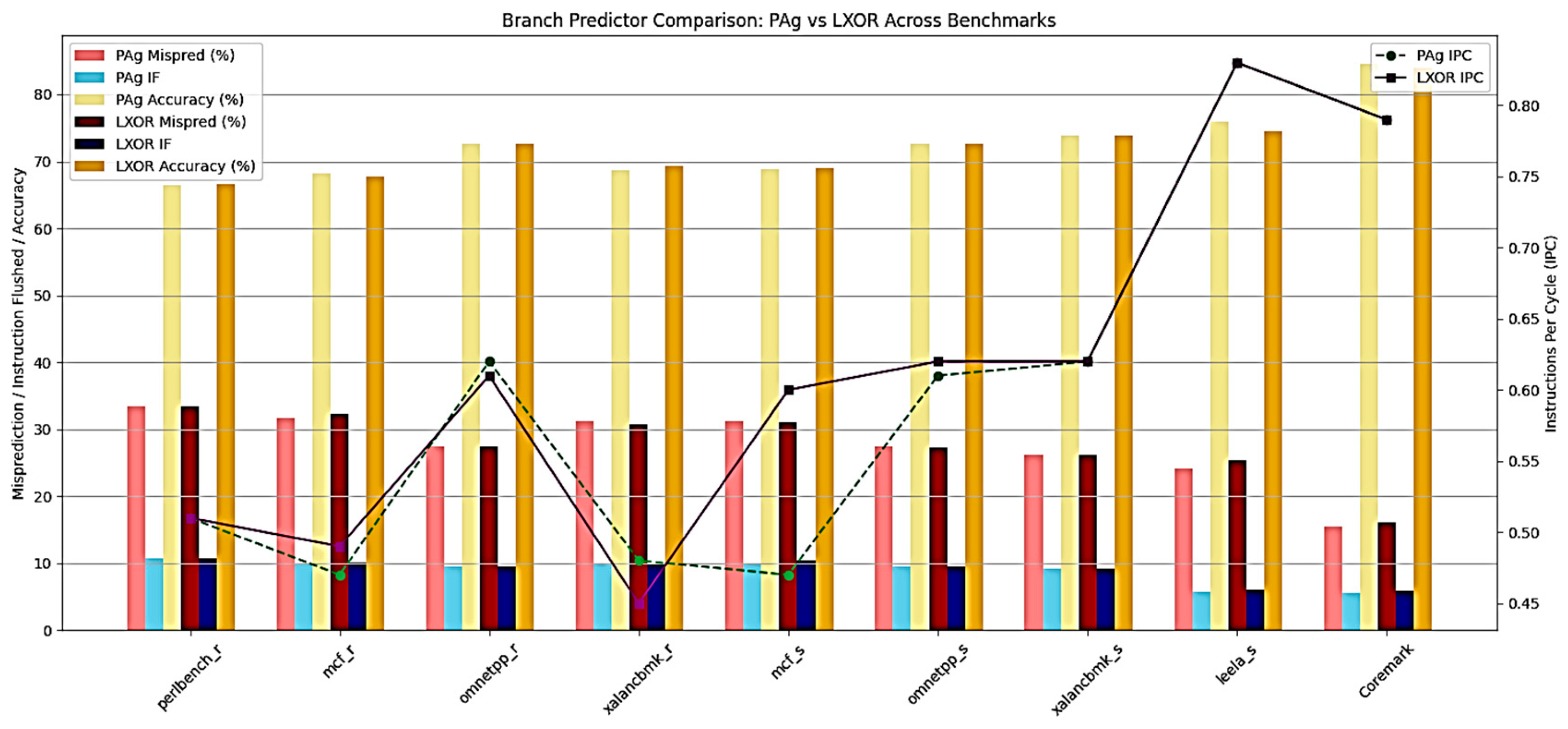

5.5. Performance Analysis of LXOR Branch Predictor Against PAg Branch Predictor

In this evaluation, both predictors demonstrate nearly identical IPC values across the majority of benchmarks, with the LXOR predictor exhibiting a slight advantage over the PAg predictor in several cases. The graph in

Figure 19 was constructed using the data presented in

Table 8 and

Table 10. For instance, in the mcf_s benchmark, LXOR achieves an IPC of 0.60, which is significantly higher than PAg’s IPC of 0.47, thus indicating enhanced pipeline efficiency as shown in

Figure 19.

Likewise, LXOR matches the performance of PAg in the leela_s, perlbench_r, xalancbmk_s and Coremark benchmarks, achieving IPC values of 0.83, 0.51, 0.62 and 0.79, respectively. Conversely, in the xalancbmk_r benchmark, the PAg predictor demonstrates slightly superior performance, with an IPC of 0.48 compared to LXOR’s 0.45. Nevertheless, these discrepancies are statistically insignificant and are contextually outweighed by the overall efficiency of LXOR in various other performance metrics.

Across all benchmarks, LXOR consistently demonstrates prediction accuracies that are comparable to or slightly superior to those of PAg. For example, LXOR achieves a peak accuracy of 83.92% on Coremark, which is marginally lower than PAg’s 84.53%, reflecting a difference of merely 0.61% and indicating comparable efficacy between the predictors. In the context of SPEC workloads, LXOR marginally outperforms PAg in xalancbmk_s (73.83% versus 73.79%), xalancbmk_r (69.32% versus 68.72%), omnetpp_s (72.65% versus 72.59%), perlbench_r (66.62% versus 66.51%), and omnetpp_r (72.6% versus 72.58%), thereby illustrating consistent performance across varying workload behaviors. Notably, in mcf_r, PAg exhibits a slight advantage with an accuracy of 68.25%, surpassing LXOR’s 67.74%. However, this advantage is offset by LXOR’s superior IPC and a reduced rate of instruction flushes. When evaluating mispredictions, which represent the inverse of accuracy, LXOR generally records fewer mispredictions or performs on par with PAg. For instance, in perlbench_r, omnetpp_r, xalancbmk_r, mcf_s, and omnetpp_s, LXOR has exhibited a lower misprediction rate. In the case of leela_s, LXOR presents a misprediction rate of 25.47%, which is slightly higher than PAg’s 24.08%. Nonetheless, both predictors yield the same IPC of 0.83.

As detailed in the memory footprint table, LXOR utilizes only 2096 bytes, whereas the PAg predictor requires 1048 bytes. Although PAg seemingly consumes less memory, this discrepancy can be attributed to its simpler architecture and restricted flexibility. The justification for LXOR’s memory usage lies in the incorporation of additional hardware logic, specifically the XOR-based transformation and localized history tracking. This design facilitates higher IPC and improved accuracy without necessitating extensive predictor tables as required by GAp or PAp. Moreover, LXOR’s memory requirements are significantly lower than those of GAp (49,168 bytes) and PAp (81,920 bytes), further underscoring its exceptional scalability.

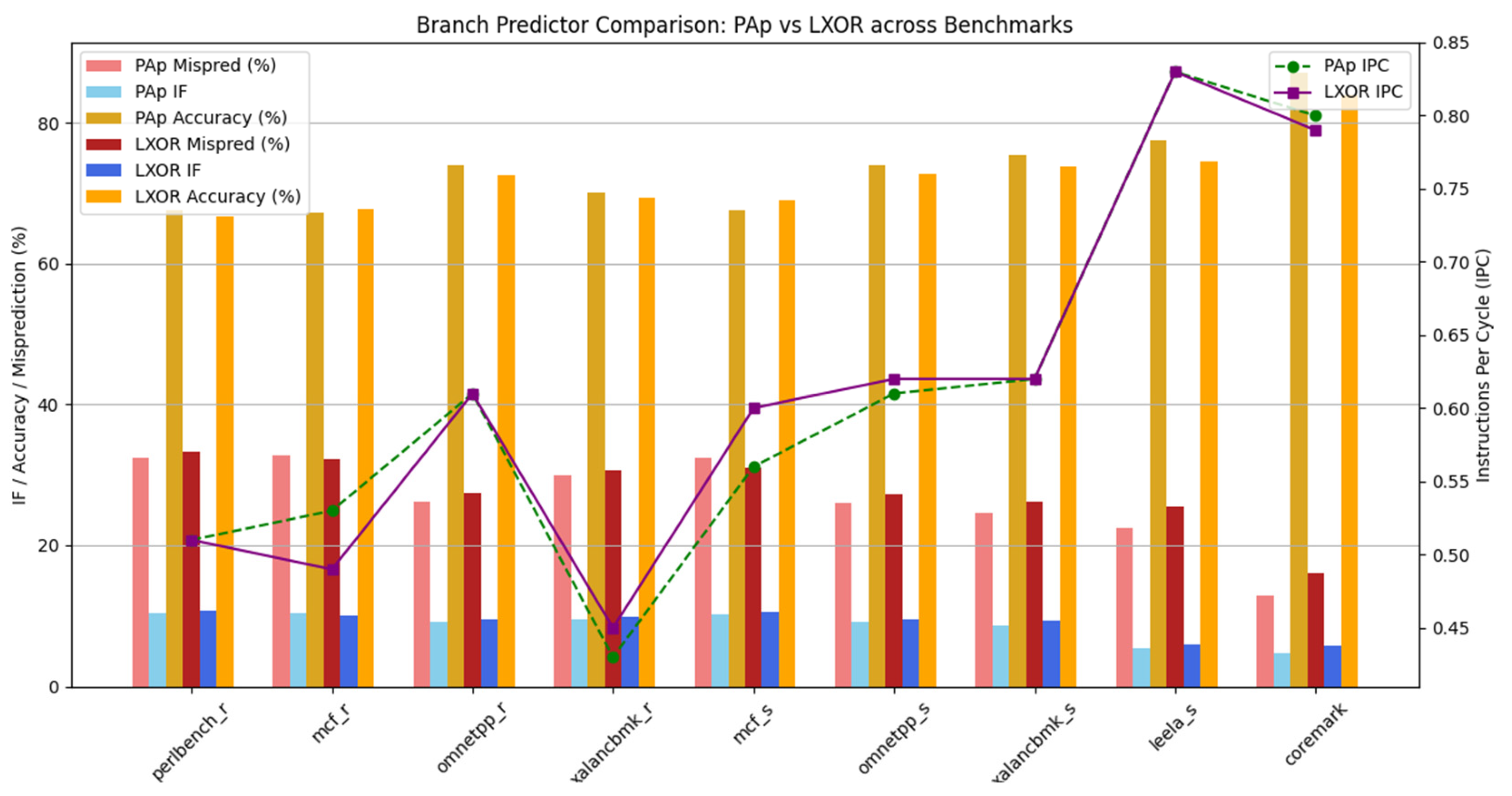

5.6. Performance Analysis of LXOR Branch Predictor Against PAp Branch Predictor

The prediction accuracy of the PAp predictor is generally superior across most benchmarks, achieving a peak accuracy of 87.03% on the Coremark benchmark, with a corresponding misprediction rate of 12.97%. In contrast, the proposed LXOR predictor yields a slightly lower accuracy of 83.92% on Coremark, resulting in a misprediction rate of 16.08% as shown in

Figure 20.

Nevertheless, the LXOR predictor demonstrates competitive performance in several SPEC benchmarks; for instance, in mcf_r and omnetpp_s, its accuracy either closely aligns with or slightly surpasses that of the PAp predictor. Although LXOR presents marginally elevated misprediction rates overall, the differences are within acceptable thresholds, particularly when considering its significantly reduced hardware footprint.

Regarding instruction flushes resulting from branch mispredictions, the PAp generally exhibits slightly superior performance, particularly in benchmarks such as CoreMark and Leela_s, where it experiences flush rates of 4.78% and 5.34% instructions, respectively. In contrast, the LXOR predictor incurs flush rates of 5.83% and 6.01% instructions for the benchmarks as mentioned above. Despite this marginal increase in flush rates, the LXOR predictor maintains a comparable flush rate across the majority of SPEC CPU2017 workloads, with variations typically confined to within a few instructions. This observation suggests that, while the PAp predictor demonstrates a slight advantage in reducing control hazards, the LXOR predictor presents a favorable trade-off when accounting for its significantly lower hardware cost.

The performance of the predictors demonstrates benchmark-dependent behavior in terms of IPC:—In the case of leela_s, both predictors yield an identical IPC of 0.83. For the CoreMark benchmark, PAp achieves a marginally superior IPC of 0.80 compared to LXOR’s 0.79, which corresponds with its enhanced accuracy and reduced flush count. Regarding the omnetpp_r benchmark, both predictors exhibit the same IPC value of 0.61. Notably, in the xalancbmk_r, mcf_s, and omnetpp_s benchmarks, LXOR achieves a slightly higher IPC of 0.45, 0.6 and 0.62 in contrast to PAp’s IPC of 0.43, 0.56, and 0.61.

The primary advantage of the proposed LXOR predictor is its remarkably low memory footprint, utilizing only 2096 bytes, in stark contrast to the 81,920 bytes required by the PAp predictor. Although the PAp predictor offers slightly improved prediction accuracy and minimizes instruction flushes in certain benchmarks, these enhancements are marginal and are accompanied by over 96% increased memory consumption. Despite its compact design, the LXOR predictor achieves comparable IPC and accuracy, with only a minor increase in misprediction rates. For example, LXOR sustains an IPC of 0.79 on the CoreMark benchmark, compared to 0.80 for the PAp predictor, while demonstrating similar accuracy levels in complex SPEC workloads such as mcf_r and omnetpp_s. This equilibrium of efficiency and performance positions LXOR as an ideal solution for resource-constrained environments, including embedded and low-power RISC-V systems, where it is essential to minimize silicon area and energy consumption without significantly compromising execution performance.

The findings reveal that, although the PAp predictor achieves slightly higher prediction accuracy and IPC in certain benchmarks, these advantages are accompanied by a significantly larger memory footprint, exceeding 81 KB, which may prove impractical for memory-constrained systems. Conversely, the LXOR predictor demonstrates comparable IPC and prediction accuracy across a variety of complex workloads, while maintaining a substantially smaller hardware footprint of only 2 KB. This represents a 98% reduction in memory usage compared to the PAp predictor. Additionally, the LXOR predictor exhibits strong performance in benchmarks characterized by high control flow complexity, such as omnetpp and xalancbmk, and matches or surpasses the PAp predictor in IPC in select instances, despite a marginally higher misprediction rate. Its design, which utilizes XOR-based indexing of local history, facilitates effective tracking of branch behavior with minimal aliasing and reduced lookup complexity. The LXOR branch predictor presents a compelling trade-off between prediction performance and hardware efficiency. Its lightweight architecture renders it particularly advantageous for embedded systems, real-time applications, and RISC-V-based processors, where area, power, and cost are critical design considerations

To synthesise the discourse on various branch prediction techniques,

Table 11 presents a comparative analysis of several established predictors, focusing on their storage overhead and qualitative performance metrics. This overview elucidates the balance between simplicity, memory efficiency, and prediction precision, offering a framework for assessing the proposed LXOR predictor in relation to traditional architectures.

The analysis presented in

Table 11 indicates that traditional predictors excel in areas such as simplicity, correlation effectiveness, or mitigation of aliasing issues; however, they tend to be plagued by heightened storage demands and constrained scalability. Conversely, the proposed LXOR predictor strikes an advantageous equilibrium, providing competitive accuracy while maintaining moderate storage utilization. This positions the LXOR predictor as a viable and memory-efficient alternative for both embedded systems and general-purpose RISC-V processors.

6. Conclusions

The LXOR branch predictor offers a robust, balanced trade-off between compactness and accuracy, an alternative to conventional dynamic branch prediction methodologies, including GAg, GAp, PAg, PAp, Gshare, and Gselect. Comprehensive simulations conducted on the MARSS-RISCV platform, utilising two distinct benchmark suites—Coremark (64-bit) and SPEC CPU2017, indicate that the LXOR predictor consistently exhibits competitive or superior performance across several critical architectural metrics. These include Instructions Per Cycle, prediction accuracy, misprediction rate, and instruction flush percentage, all while preserving a remarkably compact memory footprint.

Unlike traditional predictors that rely significantly on large Pattern History Tables (PHTs) or extensive tracking of global and local histories, the LXOR mechanism introduces a novel XOR-based indexing method combined with complemented local history. This innovative approach facilitates efficient prediction while minimizing hardware overhead. The LXOR predictor achieves an impressive prediction accuracy of up to 83.92%, maintains a low instruction flush rate of 5.83%, and supports an IPC rate between 0.79 and 0.83. Notably, it accomplishes these results with an approximate memory requirement of only 2 KB, which is a fraction of the memory utilized by more complex predictors such as PAp and GAp, which may exceed 49 KB.

In various SPEC workloads, LXOR has shown performance that either matches or surpasses that of traditional predictors, especially in environments with heavy control flow and mixed instructions. Notably, in benchmarks such as omnetpp_r, leela_s, and xalancbmk_s, LXOR achieved equal or higher IPC while also resulting in fewer instruction flushes. This highlights its robustness amid significant branch variability. Even when some predictors, like PAp, achieved slightly higher raw accuracy, LXOR demonstrated a considerably better performance-to-memory ratio. This makes LXOR a practical option for real-world processor design.

The LXOR predictor, characterized by its minimal hardware complexity and reliable predictive stability, is exceptionally well-suited for embedded systems, low-power Internet of Things (IoT) devices, real-time applications, and resource-constrained RISC-V cores. In these contexts, maximizing performance relative to power and memory utilization is of paramount importance. Additionally, the scalable and predictable nature of the LXOR predictor positions it as a strong candidate for edge computing nodes, mission-critical systems, and next-generation general-purpose processors, particularly within the rapidly expanding RISC-V ecosystem. The LXOR predictor offers a compelling equilibrium between performance, simplicity, and scalability, thereby rendering it an ideal solution for contemporary processor architectures that seek to optimize branch prediction under stringent energy, area, and timing constraints.