Abstract

Systems engineering practices in the maritime industry and the Navy consider operational availability as a system attribute determined by system components and a maintenance concept. A better understanding of the risk attitudes of system operators and maintainers may be useful in understanding potential impacts the system operators and maintainers have on operational availability. This article contributes to the literature a method that synthesizes the concepts of system reliability, and operator and maintainer risk attitudes to provide insight into the effect that risk attitudes of systems operators and maintainers have on system operational availability. The method consists of four steps providing the engineer with a risk-attitude-adjusted insight into the system’s potential operational availability. Systems engineers may use the method to iterate a system’s design or maintenance concept to improve expected operational availability. If it is deemed necessary to redesign a system, systems engineers will likely choose new system components and/or alter their configuration; however, redesign is not limited to physical alteration of the system. Several other options may be more practical depending the system’s stage in the life cycle to address low risk-adjusted operational availability such as changes to maintenance programs and system supportability rather than on component and system reliability. A simple representative example implementation is provided to demonstrate the method and discussion of the potential implications for Navy ship availability are discussed. Potential future work is also discussed.

1. Introduction

The Navy is a unique and complex organization with high tempo and extensive operational commitments. To perform well in such a dynamic environment and continue to meet the demand of prompt and sustained combat, operational availability is of paramount importance. Systems engineering practices within the Navy generally consider operational availability to be a system attribute determined by the quality and arrangement of the components within the system as well as the system’s maintenance concept. In the existing approach to operational availability, no explicit consideration is given to the characteristics of the personnel interacting with the system as it assumes any individual responsible for operating or maintaining the system will follow all guidance set forth in the maintenance concept [1,2]. Continued reliable performance of the system is contingent on the system being properly operated and maintained in accordance with said guidance. In the Navy, this responsibility falls to the officers and enlisted personnel to promote and enforce procedural compliance as a means to ensure the system achieves designed availability levels. While this is a valid and long-standing approach, it does not account for the potential of the SOM to be in non-compliance with the maintenance concept.

While the operational availability of Navy systems is generally adequate at present, there is a desire to improve further. This paper proposes a method to further improve operational availability of systems by augmenting the system engineering processes to consider risk attitudes of the individuals who interact with the system and analyzing individuals’ risk attitudes to predict their impact on operational availability. ISO 73: 2009 [3] defines a risk attitude as an “organization’s approach to assess and eventually pursue, retain, take or turn away from risk.” Rather than organizational attitudes, this paper focuses on individual risk attitudes. Thus, for the purposes of this paper, a risk attitude is an individual’s conscience or unconscious approach to assess and eventually pursue, retain, take or turn away from a perceived risk. Taking individual risk attitudes into account allows systems designers and maintenance planners to identify potential areas where improvements to the system and maintenance processes can be made that will help to match risk attitudes of people who interact with the systems.

A better understanding of how risk attitudes of SOM impact a system may be useful in modifying how a system is designed and/or operated to address potential impacts to operational availability from individuals’ risk attitudes that are not what systems engineers would otherwise have anticipated. The method presented in this paper is intended to be implemented early in the systems engineering process during overall conceptual system design and architecture to aid in maintenance concept development. The method is targeted toward new systems; however, the method may be applicable to existing systems scheduled to go through periods of major overhaul or upgrade.

Specific Contributions

This article contributes a method to the literature that can help systems engineers during the design phase of a system design effort identify potential SOM risk attitude issues related to not meeting operational availability requirements. The method can be used to help inform decision-makers on modifying components of a system or the maintenance concept of a system to incorporate the risk attitudes of SOMs.

2. Background and Related Research

This section presents background information necessary to understand the context of the research presented in this article, a review of existing literature that directly relates to the contribution of this article to the literature, and the framework in which this research exists.

2.1. System Availability

Systems engineers generally use three high-level availability statistics to quantify whether a system will be available for use when called upon. Inherent availability is determined by the design of the system; it takes into account only the hardware characteristics and assumes ideal support [4,5]. Achieved availability assumes an ideal support environment as inherent availability did but extends the calculation to include scheduled preventive maintenance [6]. Operational availability () includes all factors previously considered by achieved and inherent availability, but also includes logistics and administrative delays associated with the system [4,5] as shown in Equation (1).

In many instances in the Navy and other similar organizations, operational availability is used in part because it provides the most representative picture of system availability [5,7,8,9]. For this reason, we use operational availability in the development and demonstration of the methodology below. In most applications, system uptime and downtime are further disaggregated into three categories including—(1) system operational time which is a function of system reliability, (2) maintenance actions, and (3) supportability issues [5,6]. Subsequent subsections discuss the individual components of operational availability and potential methods for improvement.

2.2. System Reliability

Reliability is often defined as the likelihood that a system will work when expected [5]. A system with low reliability has a low probability of being in working condition when called upon and usually will have lower operational availability due to greater system downtime. Within a system, an individual component’s reliability is a function of the time period of interest and the MTBF. The exponential reliability function is shown in Equation (2), where t represents the time period of interest and M represents the MTBF of the component is commonly used to model component reliability [6].

However, not all components and equipment are well-modeled by the exponential reliability function. While many other reliability functions are available; in the context of this research [10], we focus on the exponential function. The inverse of MTBF is the failure rate ().

Two common approaches to improve availability include—(1) implement changes to components (such as replacing low reliability components with higher reliability components [11,12,13] or adding redundancy [14,15]) that improve system reliability and thus system uptime, and (2) change the maintenance concept of the system to reduce system downtime (often via preventative maintenance [16,17] which improves MTBF) [1,18].

Methods that focus on changing maintenance practices to improve system reliability generally use preventive maintenance to increase the effective MTBF of the system [16,17]. When using preventive maintenance to increase system reliability, system downtime is determined by both component failure (MTBM) and scheduled preventive maintenance (MTBM) [4,6]. Overall MTBM can then be calculated with Equation (3) [7,8].

System downtime is then measured by the mean active maintenance time, , determined by both corrective and preventive maintenance times. Additional reliability information and background is available in References [4,19]. Further discussion of maintainability is provided in the next subsection.

2.3. Maintenance Strategies

Maintainability is a system design characteristic that captures how easy it is to maintain a system, how accurately the maintenance can be done, the safety of performing the maintenance actions, and the cost of performing maintenance [6]. Systems designed to be maintainable capitalize on the system’s maintainability characteristics to improve reliability which leads to better operational availability for the overall system. While the reliability of a system is largely determined by the system’s design, it can be positively or negatively impacted by the frequency and quality of maintenance performed on the components [17]. To ensure a system remains reliable throughout its operational life, one must ensure that the system is properly maintained. Swanson [17] presents three strategies commonly used in the approach to maintenance. Reactive maintenance is conducted in response to a failure in the equipment. In this method, MTBM is equivalent to MTBM. Proactive maintenance incorporates predictive and preventive maintenance practices to extend the MTBF of system components. In general, MTTR describes how long it takes to repair a system. Swanson’s “aggressive strategy” to situations where reactive and proactive maintenance are not enough to achieve sufficient system availability is to improve system function and design at the penalty of increased cost, requirements for resources, training, and integration.

Waeyenbergh and Pintelon suggest expanded maintenance strategies beyond Swanson’s strategies be introduced such as the “integrated business concept,” and note that as maintenance strategies become more integrated, there has been “a shift from failure-based to use-based maintenance and increasingly towards condition-based maintenance” with increased emphasis on the production facilities in terms of reliability, availability, and safety [1]. Others have suggested optimizing system availability such as through genetic algorithms and similar to balance preventative and corrective maintenance actions [14,20]. While these approaches are useful for optimization of maintenance, they generally rest on the assumption of ideal logistics support which is at odds with the formulation of operational availability. For this reason, it is important to consider the supportability characteristics of the system which is discussed further in the next subsection.

2.4. Supportability

Supportability is a system aspect primarily concerned with the logistics and support mechanisms by which a system is acquired, installed, and subsequently maintained [6]. With regard to operational availability, the most significant supportability aspects focus on system maintenance and support, and the ILS system that provides the materiel [21]. ILS contains four objectives, including—(1) make considerations for system support integral to the design; (2) develop coherent, design-focused support requirements to achieve readiness objectives; (3) obtain adequate support; (4) provide support at minimum cost throughout the system’s operational phase. ILS is effected by administrative down time ADT and logistics delay time LDT [7,8]. ADT is the amount of time the system is inoperable for administrative reasons such as organizational constraints, administrative approval processes, personnel assignment priorities, and so forth. LDT is the amount of time the system is inoperable due to lack of parts, facility space, test equipment, and so on. System downtime—otherwise known as MDT—is, thus, defined by Equation (4).

Reducing LDT, as part of a supportability push in the Navy, is an ongoing effort [22,23]. The broader impact of supportability on has been recognized for some time [24]. However, while the role of SOM is represented in many of the components of , the impact of SOM risk attitudes has not been explicitly considered.

2.5. Risk Attitudes of SOMs

In the context of the present discussion, the risk attitudes of SOMs are important to understand in relation to their work on systems. We ascribe to the opinion of much of the literature, that risk attitude can be mapped on a utility function as a personality trait [25]. Humans are integral to the operation and maintenance of almost all systems in the Navy’s inventory. Many consider Naval vessels to be SOS where hardware and software systems, and humans are integrated together into a larger SOS [5,6] which integrates into the larger concept of mission engineering where Naval assets are brought together to accomplish specific missions and objectives [26]. With such a significant effort placed on reliability as a factor in maximizing operational availability [5], substantial effort must be made and great care taken to understand how to best design the systems to accommodate (and in some instances withstand) interactions with SOMs as part of HSI [27]. Two benefits of addressing the human element from a HSI perspective are significant reductions in waste and substantial system productivity and performance increases [27]. HSI helps to maintain high operational availability for a system by addressing the usability characteristics of the system for the SOMs. While good hardware and software design can improve system usability, a variety of factors must also be explicitly taken into account including anthropometric characteristics, sensory factors, physiological factors, cultural, and psychological factors [6,27,28].

Psychological factors within the context of usability and HSI relate to personal attitudes, risk tolerance, and motivation [5,28,29]. Psychological factors are of specific interest to this research as they relate to the likelihood that a SOM will perform his or her duties as expected. The field of HRA in part examines psychological factors that can reduce the reliability of humans to complete tasks [29,30]. For instance, maintenance errors can sometimes be attributed to psychological factors, which Dhillon attributes to six factors including: “recognition failures, memory failures, skill-based slips, knowledge-based errors, rule-based slips, and violation errors” [29]. This does not imply that a system cannot be designed without expressly addressing these factors, but rather available information on the psychological disposition of the SOMs should be incorporated to improve the system design process [6]. Methods already exist to understand the psychology [31] and risk attitudes of engineers designing systems [25], and incorporate those attitudes into design decision-making processes [32]. However, we are unaware of any existing methods or processes that explicitly consider the risk attitudes of SOMs in the context of operational availability of systems in general and especially in the context of Naval systems.

In order to understand the risk attitudes of SOMs, a repeatable method of testing is needed. Many methods exist in the literature to choose from although none is specifically tailored to SOMs. For instance, the DOSPERT psychometric risk survey tests people for risk tolerance and risk aversion across personal domains of risk [33]. An extension to DOSPERT was made for engineers in their professional capacities [25]. Other methods such as choice lotteries are also available [34]. Recent research indicates that a general risk aversion-risk seeking inclination may be present in individuals that applies across domains [35]. Risk attitude data from psychometric survey techniques has been found to be aspirational in nature while choice lotteries are generally predictive [32,36]. In this research, we take the perspective of aspirational risk attitude measures (i.e., psychometric risk surveys) in line with existing research on applying risk attitudes to engineering analyses and trade-off studies [32,37].

Risk attitudes encompass how individuals respond to situations where there are potential rewards and costs to specific choices. For instance, time pressure, insufficient time to perform a task completely and at high quality, difficulty of activity, and other factors all are intrinsically evaluated by an individual using the individual’s risk attitudes. An individual’s risk attitude can be thought of as modifying an expected value representation of a set of decision choices so that a choice that otherwise would not have been as attractive to take becomes the most attractive choice among the set [33,36].

High reliability organizations, typical of most military or other organizations in which individual decisions can have catastrophic outcomes, attempt to train and exercise in order to modify personal behaviors independent of their individual risk attitudes [38]. However, in spite of this, our combined professional experience indicates that no training is perfect and years of bad habits can make correcting risk attitudes difficult. While the investigation is ongoing, it is thought that the most likely cause of the recent fires aboard the USS Bon Homme Richard (a Landing Helicopter Deck (LHD) class ship), while it was in port undergoing a maintenance retrofit, was human error while conducting maintenance [39]. The crew and civilian maintenance teams were undoubtedly all well trained and aware of proper procedures as is almost universally required in the U.S. Navy. Yet, a fire, which ultimately damaged 11 of 14 decks causing hundred of millions of dollars in damage [40] (or a replacement cost of $4 billion [41]), started in the lower vehicle hold where oily rags were being stored during maintenance. Making matters worse, the halon fire suppression system had been disengaged. It is clear that the U.S. Navy believes this was human error, because if it was systemic or technical error, the other seven Wasp-Class LHD class ships would be called to port (unless operations do not permit, at which point the discussion becomes about enterprise risk attitudes). Incidents like the fire aboard the Bon Homme Richard serve as a feedback mechanism for improving training and processes, as well as holding negligent personnel liable and highlighting the importance of accounting for individual risk attitudes in maintenance activities.

Sabotage by maintenance personnel also serve to illustrate how individual attitudes have a large impact on operations. In 2013, a shipyard worker set fire to rags aboard the nuclear submarine, USS Miami, because he wanted to go home early [42]. While still undetermined, but possibly sabotage by maintenance personnel, the destruction of S.S. Normandie (aka: USS Lafayette) in New York Harbor in 1942 during a retrofit from luxury ocean-liner to troop transport also serves to illustrate how risk attitudes of individual maintenance personnel can have extremely large impacts upon the overall system [43,44]. The risk of simply missing a scheduled preventative maintenance, or declaring something operational when it is not, is different than large ship-damaging or destroying fires. But, because the risk is likely perceived to be lower, oversights in preventative maintenance are probably much more common.

Our combined personal experiences in the U.S. military and civilian industry support the notion that smaller maintenance tasks may be skipped or falsified as being complete, having observed maintenance and readiness records that may have been falsified for a host of different reasons. Two of the four authors have also served as maintenance officers in the U.S. military, and one is a war veteran. In our observations, both leaders and maintenance personnel weigh risk based on their individual perception of cost versus reward. In situations where there is a very demanding schedule and many competing requirements, the perception of cost versus reward often appears to skew further. For example, the Marine Corps may require weapons preventative maintenance weekly, but the reality is that weapons often are not cleaned until leadership makes it a priority over the litany of other operational and training requirements simultaneously levied. Such a priority is currently being implemented by the U.S. Navy following the USS Bon Homme Richard fire [45]. The risk of not cleaning weapons weekly is probably negligible in peace time, although if enough time passes rust and pitting can damage a weapon beyond repair. However, in a war zone, where training requirements cease and operations are the focus, cleaning weapons takes on a much more urgent tone. The point is, from an idealized perspective, training and exercises should sufficiently modify behaviors independent of individual risk attitudes, but people still frequently take risks based on the immediate context and their own risk attitudes. Training, exercises, individual and collective risk attitudes, processes, competing requirements, and a whole host of other variables ultimately impact maintenance behaviors. This article specifically focuses on individual risk attitudes as a variable and takes the perspective that while training and exercises may help to change individual risk attitudes to a degree, often times said individual risk attitudes do not significantly change.

2.6. Utility Theory

Utility theory can be used to help make decisions based on risk attitude information as has been demonstrated in the literature using engineering risk attitudes from a psychometric test [32] where the utility function was adjusted based on risk attitude. In the case of [32], the value was specified in monetary units as is often the case with the broader field of utility theory research [46]. The relationship between value and its utility can often be defined mathematically which results in a utility function. This can be expanded to adopt a risk attitude as the utility function [47]. The exponential utility function in particular has been demonstrated in the literature as being useful for risk attitude-driven decision-making [32]. We adopt the exponential utility function for the purposes of this research.

While the method for a MTBF that can be described by an exponential function is demonstrated in this article, many functions that represent MTBF for a variety of types of equipment and circumstances are available in the literature. Keeney and Raffia [48] provide quadratic and logarithmic utility function formulations. Additional guidance on formulation of utility functions is given in the literature [49,50]. While many different distributions of MTBF are found in the literature, we have specifically focused on the exponential function in this work to demonstrate the proposed method. Appropriate utility functions for other MTBF distributions can be inserted in place of the exponential function formulation found herein.

A utility function is often used to compare the relationship between multiple sets of choice outcomes and, based on the nature of the relationships being investigated, the utility of the value of each potential choice may increase or decrease. This relationship is generally assumed to be monotonically increasing (Equation (6)) [47] although in some instances, the relationship and thus the utility function may be decreasing (Equation (7)) instead. In the case of understanding operational availability, some parameters such as reliability are monotonically increasing in nature while others such as MTTR and the time spent conducting maintenance actions are inversely related to operational availability and thus are decreasing.

In Equations (6) and (7) above, represents risk tolerance [47]. The high and low values form the upper and lower bounds of the value in question. The depth of the function’s curve when graphically plotted is dependent on the value of . A larger value of results in a less pronounced curve, while a smaller value results in a curve that is more pronounced [47].

2.7. Contextualizing this Research within the Systems Engineering Process

In order to contextualize the research presented in this article, it is important to understand the systems engineering process and how this research fits within the process. The systems engineering “vee” model is an often used model of the systems engineering process although not exclusively [6]. Impacts to operational availability can be traced to nearly every location on the entire “vee” model. The area of specific interest to this research is in the integration and verification steps during the system operation phase where SOM action or inaction based in part on SOMs risk attitudes can directly impact operational availability through system downtime. However, the issue of SOMs risk attitude impact on operational availability can be traced to the decomposition and definition phase of the “vee” model. Thus this implies an iterative approach where feedback from currently operating systems and understanding SOM risk attitudes can be used to design new systems to better meet SOM risk attitudes and in turn improve operational availability.

The usefulness of employing a systems engineering approach to risk-informed systems engineering and design is that it helps system owners to better understand the relationship between risk attitudes in SOMs of systems and their effects on system operational availability. In understanding how system operation and maintenance is likely to be conducted, engineers can apply lessons learned to both equipment overhauls and ground-up system development. Successful implementation of risk attitude-informed adjustments during the design phase through aspirational system designs as described above and as implemented in this research below may provide improved system performance through matching system design to realistic operational and maintenance requirements.

3. Methodology

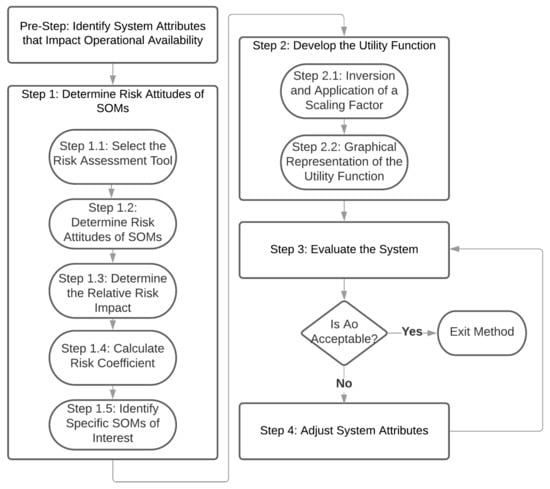

The methodology presented below synthesizes concepts of reliability, risk attitudes, and utility theory to quantify otherwise qualitative characteristics of SOMs as they relate to operational availability. The process consists of a preparatory step and four main steps providing the engineer with a risk-attitude-adjusted insight into the system’s utility as determined by a system value parameter, which in this case is system or component reliability. The method has a provision for systems engineers to use the output of the first three steps to inform any necessary iterations to the system design process. As systems engineering is an iterative and recursive process, it may be necessary to perform steps three and four until reaching a satisfactory outcome. Figure 1 graphically shows the steps of the method.

Figure 1.

Process diagram of the proposed methodology.

3.1. Pre-Step: Identify System Attributes that Impact Operational Availability

Prior to starting the method, narrowing the field of potential system attributes that impact operational availability is recommended. While the interested practitioner could consider all potential attributes throughout the proposed method, we advocate for only examining one attribute at a time to more clearly understand the interplay between SOM risk attitudes, the attribute being considered, and its impact on operational availability. Potential attributes include reliability, maintainability, and supportability. This article focuses on reliability because our past operational experiences strongly anecdotally indicate that reliability is a significant contributor to operational availability and is also tied to risk attitudes of SOMs; however, the other above identified attributes may also be useful for practitioners to pursue in some cases.

After choosing which attribute to examine, requisite information needs to be collected about the system. For instance, in the case of reliability, an understanding of component reliability and the Reliability Block Diagram (RBD) of the system of interest is needed. Further information on RBDs and basic reliability concepts is available in [6,19].

3.2. Step 1: Determine Risk Attitudes of SOMs

After completing the pre-step, the first step of the method is to understand the risk attitudes of the SOMs involved with the operation and maintenance of the system. In order to achieve this, five sub-steps must occur including (1) select the risk assessment tool, (2) determine SOM risk attitudes, (3) determine relative risk impact, (4) calculate risk coefficient, and (5) identify SOMs of interest.

3.2.1. Step 1.1: Select the Risk Assessment Tool

In the case where aspirational risk attitudes are useful for system design, an aspirational risk attitude test is prescribed such as the DOSPERT psychometric risk survey. Predictive risk attitudes can be elicited from choice lotteries and other related survey instruments [25,32,33]. There may be cases where the practitioner wishes to use predictive risk attitudes in which case we recommend choice lotteries. But, as discussed earlier, we propose that aspirational system design is more appropriate than predictive system design from the perspective of SOM risk attitudes. This is in line with the literature such as Reference [32] where the authors developed aspirational space mission designs to meet the expectations of key stakeholders.

While some evidence exists that custom tailored psychometric risk surveys are most appropriate to understand specific domains of risk attitudes, such as within a person’s private life or professional life, developing a psychometric risk survey specifically tailored for SOMs within the context of Naval vessels is beyond the scope of this research [25,33]. Some recent research indicates that understanding general risk aversion and tolerance may apply across many domains [35]. For these reasons, we recommend that practitioners use DOSPERT or a related psychometric risk survey [25,33] to gain a high-level understanding of SOM risk attitudes. If further refinement of analysis conducted from the method presented in this article is desired, a tailored psychometric risk survey may be justified. Further information on developing psychometric risk surveys is available in the literature [51,52,53,54,55]. While the DOSPERT test was developed from a personal, private life risk attitude perspective, these domains are generally well-aligned with potential broad domains of risk attitudes of SOMs at their jobs. This research is echoed in the investigations of decentralized decision-making in structural health monitoring systems as well as military operational risk taking [56,57].

3.2.2. Step 1.2: Determine Risk Attitudes of SOMs

To determine each SOM’s individual risk attitudes a representative pool of SOMs are given a psychometric risk survey asking for their perception of various scenarios involving risk-based decisions. The results of the surveys are then analyzed to identify risk attitudes. The risk attitude information is then translated into a set of coefficients indicating his or her risk tolerance or aversion in each domain. Depending upon which psychometric risk survey is used, a variety of risk domains are produced. In the case of DOSPERT, five domains including ethics, finance, health/safety, recreation, and social are used. While some literature indicates that risk domains can be collapsed into one risk aversion-risk tolerance scale [35], we suggest waiting to average between the risk domains until a later sub-step in the proposed method.

For purposes of calculations performed in this method, the range of possible risk attitudes is set between −1 for complete risk aversion to 1 for complete risk tolerance. Others using psychometric risk surveys to help make system design decisions have used a −3 to 3 scale in their work [25]; however, the scales can be renormalized around any cardinal number set. A value of 0 indicates completely risk-neutral decision-making. Table 1 provides an example of an individual SOM’s personal risk attitude composition across the five risk domains from DOSPERT. In this instance, the SOM is risk averse in two domains, risk tolerant in two domains, and risk neutral in a single domain.

Table 1.

Example Personal Risk Attitude Composition of a SOM Using the DOSPERT Psychometric Risk Survey.

We propose that risk aversion as it pertains to reliability is equivalent to being risk neutral. This is based on our own observations of SOMs working on various Naval systems where almost any SOM exhibiting either risk neutral or risk averse risk attitudes exhibits the same levels of procedural compliance—namely, full compliance. However, practitioners must choose for themselves if they believe the proposal to change any risk averse scores to being risk neutral is valid.

3.2.3. Step 1.3: Determine the Relative Risk Impact

While an individual SOM’s risk attitude in each risk domain identified by a psychometric risk survey such as the DOSPERT has an impact on the operational availability of the system, the impacts are not uniformly consistent across the set of domains for a given value. For instance, an individual’s desire for social acceptance may lead the individual to decision-making that has a significant impact on the system the individual maintains, whereas the individual’s risk attitude in the recreation domain would be inconsequential. While readily understandable using intuition and engineering judgement, there is limited research available to provide quantitative data for these relative impacts; however, the method presented in this article has the ability for systems engineers or other decision-makers to include such effects. Thus we propose implementing a relative risk attitude impact correction factor.

To implement this method, relative risk attitude impact correction factors need to be intelligently estimated by maintenance SMEs based on their collective experience and the specific context. This is no easy task, as it requires both judgement and expertise, and individual SMEs may judge risks differently (just like individual risk attitudes ultimately impact maintenance). We recommend evaluating each of the domains of risk attitude for applicability to the specific context and applying a weighting to each domain based on the relative importance of the domain to the context. For instance, a SME may judge that the impact of the social risk domain to a maintenance action to be very low. Thus where a relative impact correction factor of 1 represents no correction from the DOSPERT risk domain scores, a relative risk attitude impact correction factor of 0.25 indicates a significant discounting of that particular risk domain from being applicable to the specific context the SME is evaluating. Conversely, a score of 1.5 on the health/safety risk domain indicates that the domain is believed to be very important by the SME. This approach of eliciting relative risk attitude impact correction factors is similar to multi-attribute decision making [58,59].

We emphatically note that the proposed method is not intended to be a highly rigorous, hard-and-fast decision-making tool used for detailed decisions late in the design process but instead is targeted for use during the system architecture phase of design as a tool for better understanding what impact risk attitudes of SOMs have on operational availability. While the method is quantitative in nature, it is not intended to be used as the only decision-making tool or to choose between very similar options. Instead, the method presented here is meant to be used to better inform decisions made about system design and the system maintenance concept.

Table 2 provides a representative set of potential relative risk attitude impact correction factors for a generic situation with reference to maintenance on board a Naval vessel. The relative risk attitude impact correction factors shown in Table 2 were developed by U.S. Navy maintenance SMEs and may be useful to practitioners working with similar naval systems. A practitioner using this method is advised to develop relative risk attitude impact correction factors appropriate to the system under analysis.

Table 2.

DOSPERT Risk Domains with Relative Risk Attitude Impact Correction Factors (Denoted as Relative Impact in the Table) Appropriate to the System Under Analysis. Note That These Factors are Examples and That Practitioners are Advised to Identify Appropriate Factors for the System of Interest.

3.2.4. Step 1.4: Calculate Risk Coefficient

After determining both the SOM’s individual risk attitude in each of the risk domains, as well as noting the impact the domain itself has on operational availability via the relative risk attitude impact correction factor which is based on the selected system attribute—we selected reliability earlier in the description and continue using reliability here—multiplying the two values together yields a domain-specific risk-decision impact. Upon determining the values for each domain-specific risk-decision impact, summing them together provides a single value which is representative of the SOM’s overall risk attitude and expected impact on the reliability of the system with which the SOM is interacting, , as shown in Equation (8).

In Equation (8), n is the risk domain (in the case of DOSPERT, ethics, finance, health/safety, recreation, social), is the risk tolerance or aversion in domain n as derived from the risk survey, and is the relative risk attitude impact correction factor of the risk domain on reliability of the system. Reducing the set of domain values to a single number is useful for several reasons including its ability to be used as a scaling factor in a utility function such as how [32] used a similar combination of multiple risk domains in situations where direct mapping from risk domains to a specific risk-informed design decision cannot be made. In the context of operational availability of Naval vessels and when using DOSPERT or a similar psychometric risk survey that is not specifically tailored to answer Naval vessel operational availability questions, we suggest that it is appropriate to combine multiple risk domains together into one risk attitude only after considering the relative impacts of each risk domain on operational availability as described above.

3.2.5. Step 1.5: Identify Specific SOMs of Interest

The final sub-step in Step 1 is to identify the specific SOMs that are of specific interest to a system engineer working on improving the operational availability of a system. Not all SOMs contribute equally to the operation and maintenance of a system. Thus it may be appropriate to focus on one individual SOM that has the most contact with a system or it may be appropriate to look at many SOMs to determine an average . We recommend that the decision only to analyze one individual versus a group of SOMs should be based on whether many SOMs work on a specific system or if one dedicated SOMs will exclusively work on the system.

If many SOMs will work on the same system, analysis of risk attitudes across the domains of risk utilizing DOSPERT may reveal similar risk attitudes among the various factors within a group of SOMs. Alternatively, the analysis may reveal large standard deviations within the domains indicating disparate risk attitudes. Given a sufficiently low standard deviation, using the average risk attitude of the SOMs may be desirable for encapsulating SOM risk aversion or risk seeking at a high level.

While this approach works with any group of SOMs, analysis of certain subsets of personnel may prove more useful than others. For instance, an engineer may survey all personnel who do a specific kind of maintenance on a specific class of ship, or a representative subset of them. Depending on the magnitude of deviation from an average score, the population can be said to have a relatively homogeneous risk attitude connoting confidence in any subsequent risk impact determination. Conversely, large deviations suggest the average risk attitude to be of low utility as an input to the risk utility function.

In the case of Naval vessels and other similar large systems staffed by SOMs who have gone through similar indoctrination and experiences, we suggest that averaging across a representative respondent pool of SOMs that may serve aboard a vessel of interest (the system of interest) is appropriate. This is in line with how current Naval personnel and staffing actions are taken where the vast majority of systems are operated and maintained by many different individual SOMs and no one system is the sole purview of one individual SOM. Equation (9) demonstrates how to combine the of several SOMs where n is the number of SOMs being analyzed and is the value for SOM x.

3.3. Step 2: Develop the Utility Function

Next, an appropriate utility function must be selected to evaluate the system attribute of interest—in our case, reliability—in the context of operational availability. As discussed in Section 2.6, we advocate using a monotonically increasing exponential function which is shown in its generic form in Equation (6). Adapting Equation (6) to include the impact of risk attitudes from SOMs on a system per the previously described process of calculating leads to Equation (10) where is the risk coefficient which is inversely related to the risk tolerance of the SOM, the value x is the reliability of the system, and the utility is the risk-adjusted impact to the expected operational availability of the system.

3.3.1. Step 2.1: Inversion and Application of a Scaling Factor

As is evident in Equation (10), increasing the value of produces a less pronounced curve, which incorrectly associates increased risk-attitude with decreased impact on the system. Equation (11) corrects the relationship of with risk attitudes:

where indicates the depth of the utility function, represents the overall risk attitude of the SOM, and represents a scaling factor indicating the impact of risk attitudes on system reliability. While the scaling factor can be empirically derived given significant quantitative historical data, this data often does not exist or is challenging for the practitioner to access and thus we suggest instead to follow the approaches [32] and others used to identify a useful . In general, rules of thumb exist for a variety of industries such as the oil and chemical industries [60] and additional guidance is given by others [47,61]. It is important that practitioners select an appropriate for their specific industry, company, system, and other similar factors. It is beyond the scope of this article to give detailed guidance on selecting an appropriate and we refer those interested in learning more to the above references.

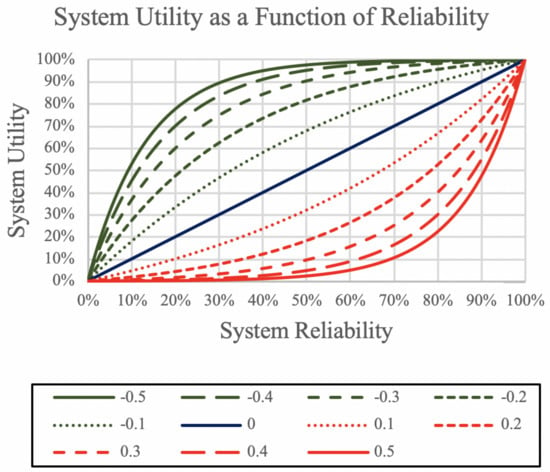

3.3.2. Step 2.2: Graphical Representation of the Utility Function

The final sub-step in Step 2 is to produce a graphical representation of the utility function developed previously. While having a graphical representation of the utility function is not strictly necessary, it can be useful to visualize the utility function for better understanding the results of the calculations performed later. Figure 2 shows a set of utility functions plotted out with system reliability providing the value input to the functions. The functions are differentiated by a variety values where risk tolerance is indicated in red (positive values) and risk aversion is shown in green (negative values). The blue line (a value of 0) indicates a perfectly risk neutral . The further away from risk neutral is, the larger the representative curve on Figure 2.

Figure 2.

System Utility as a Function of Reliability for a Variety of Monotonically Increasing Exponential Utility Functions with Varying Values. Negative (Green Line) Values Indicate Risk Aversion While Positive (Red Line) Values Indicate Risk Tolerance. Note that the Utility Functions are Exaggerated for Demonstration Purposes.

In the case of a risk neutral (indicating a perfectly risk neutral SOM) and a system with a nominal reliability of 90%, the utility of the system is also 90%. However, a risk-seeking SOM diminishes the the utility of the system according to the magnitude of the SOM’s risk attitude, as defined in Equation (8). While a risk averse SOM may seem ideal to increase operational availability, there remains a need to balance cost versus operational availability where, for instance, a risk averse SOM may perform significantly more preventative maintenance than is needed. Note that the utility functions depicted in Figure 2 are likely more extreme than what would be typically observed based on the literature [32]; however, we have displayed these likely extreme utility functions to demonstrate how changing can significantly change the utility of a specific decision set for a given value.

3.4. Step 3: Evaluate the System

Now that the utility function has been fully developed, a practitioner is able to determine the effect of a SOM or group of SOMs’ risk attitude on system utility from the perspective of reliability as it relates to operational availability. In order to use Equation (10) to evaluate the system, a practitioner needs to have previously calculated from Equation (11). Recall from Step 2 that x in Equation (10) is the reliability of the system likely calculated from a RBD and available reliability data. The result of Equation (10) is a risk attitude-adjusted utility which relates to system reliability. For instance, a system designed with an objective reliability of 95% has a risk neutral utility of 95%, but if the outcome is adjusted to account for a risk-tolerant SOM, it may be that the risk-attitude adjusted utility is 92%. While the objective utility of the system is defined as 95%, if the threshold utility for that system is 90%, a risk-attitude adjusted utility of 92% may still be sufficient and fail to trigger iteration of the design process. However, if the objective and threshold utility values are equal or the stakeholder has sufficient motivation to achieve the objective design requirements rather than threshold requirements, system redesign may be the desired course of action.

The information obtained from the risk-adjusted system utility can now be used as an informative tool during system design to help ensure that stakeholder requirements are met based on the outcome of the utility function. It may be found that the risk-adjusted system utility is still within objective and threshold values. However, it may also be found that a design iteration should occur to help correct any potential shortcomings that could impact reliability of the system. We note that system redesign need not only include physical alteration of the system. Several other options, which may be more practical depending the system’s location in the SE process, do not address the issues from a reliability perspective but instead approach the problem from a maintainability or supportability perspective. For example, efforts could be made to utilize specialized training to reduce the system’s mean time to repair. Additionally, efforts to reduce administrative or logistics delays may prove of use in boosting the system’s operational availability levels; however, if any combination of these methods proves insufficient, it may be necessary to address the problem by addressing the risk attitudes of the SOM. While we can provide (and have provided above) suggestions at where to look to fix low risk-adjusted system utility values during a redesign of a system, individual systems, the organizations the systems belong to, and the practitioners involved all play a significant role in determining the best course of action for each situation.

3.5. Step 4: Adjust System Attributes

If the practitioner decides to redesign the system, they will choose new system components and/or alter component configuration. As mentioned in the previous section, design may be an iterative process. Notionally, based on the utility function, it is possible to determine the necessary system reliability for a given utility and SOM risk attitude; but we re-emphasize that although this process attempts to quantify otherwise qualitative data, the complex and interdependent nature of the many factors contributing to a system’s operational availability limit implementation of this model in an exclusively quantitative manner. Rather, the proposed method is designed to be used as a reference tool to aid in the process of system design. After the new system has been designed, a practitioner will determine the revised system reliability and obtain a new system utility from the utility function. If the outcome is still unsatisfactory, the process with continue to iterate. This iteration process is essentially a repetition of steps 4 and 5 until attainment of a satisfactory outcome.

When the practitioner is satisfied that the system has been adjusted to meet the risk attitude of the SOMs and achieve the desired operational availability via system redesign, then the practitioner can cease using the method. However, it may be useful to periodically re-check assumptions made throughout the method and re-evaluate the system throughout the system’s life-cycle. We have anecdotally observed in our professional practice that risk attitudes of SOMs can change over time as new generations of SOMs come aboard.

4. Example Implementation

This section provides an example scenario demonstrating how the proposed method can be applied by systems engineering practitioners concerned with improving the operational availability of their systems from the perspective of risk attitudes of SOMs. The example is applied to a generic system broadly representative of a system which may be found aboard Naval vessels and shows the implementation of the proposed method outlined in Section 3. While this case study focuses on a Naval vessel system, the proposed method remains relevant to other enterprises.

A systems engineer has been assigned to a project team developing a system to support various maritime operations with operating periods of 500 h. Over these time periods, the system must maintain high levels of operational availability. To support these requirements, the systems engineer has determined the system requires a threshold reliability level of at least 90%.

4.1. Pre-Step: Identify System Attributes that Impact Operational Availability

Reliability is chosen as the system attribute to focus upon in the context of SOM risk attitude impact upon operational availability.

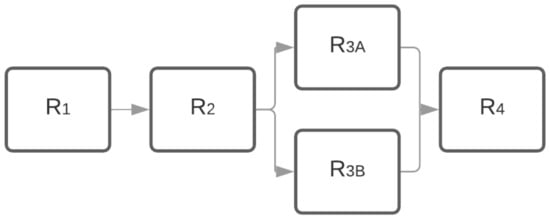

The system of interest is a four-component system with a series-parallel configuration where one component is replicated in parallel. The component reliability data for the system are representative of a system with reasonable reliability levels for maritime environments.

Table 3 shows notional parameters for the system components. The MTBF value accounts for the inclusion of a preventive maintenance plan. The reliability data are based on the operating period of 500 h.

Table 3.

Component Reliability Data For Example Maritime System Over 500 Hour Operating Period.

Component three has the highest failure rate which has previously been mitigated component being configured to have parallel redundancy. The RBD of the system is shown in Figure 3. Standard reliability calculations are performed based on this data [19].

Figure 3.

Example Component Configuration RBD of a Generic Maritime System.

Given the expected reliability of the system, one could expect that given a risk neutral SOM in full compliance with the maintenance plan, the system should achieve roughly 90% reliability, meeting the threshold requirement for reliability. However, the systems engineer using the proposed method is interested in understanding the risk-adjusted utility of the reliability of the system.

4.2. Step 1: Determine Risk Attitudes of SOMs

Step 1.1: Select the Risk Assessment Tool

Following the guidance we gave in Section 3.2.1 about selecting a specific risk assessment tool, the example uses the DOSPERT test [33] to assess SOM risk attitude. While the DOSPERT test was developed from a personal, private life risk attitude perspective, these domains are generally reasonably well-aligned with potential broad domains of risk attitudes of SOMs at their jobs.

4.3. Steps 1.2–1.5: A Summary

For this example, the outputs for sub-steps 1.1 through 1.5 have been summarized in Table 4. While the proposed method can work for an individual SOM, naval systems such as the maritime system in the example are almost universally maintained by a pool of SOMs thus it is appropriate to combine SOM risk attitudes for further analysis. On Naval systems, it is generally the case that the SOMs are distributed among the divisions, departments, or even the entire crew.

Table 4.

Risk Attitude Summary for a Group of SOMs Who Work On the Maritime System.

Table 4 shows a notional average risk attitude composition summary for the group of SOMs working with the system. As shown in Table 4, risk averse risk attitude values have been reassigned a value of zero to represent the equivalence of risk averse attitudes with risk neutral risk attitudes as discussed previously. Then a scaling factor of one is implemented for demonstration purposes and is solved for.

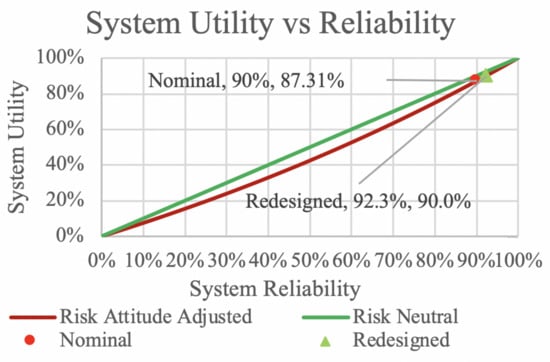

4.4. Step 2: Develop the Utility Function

The reliability of the maritime system is considered to be monotonically increasing. Equation (10) is used with the value x being the reliability of the system. Now the systems engineer has all of the components necessary to calculate the system utility based on the risk attitudes of the SOMs.

Although the SOMs are risk averse in the finance and recreation risk domains of the DOSPERT, their moderate social risk seeking coupled with significant risk seeking in ethics and health/safety result in a potentially significant effect on system reliability. The example system has a reliability of 90.2% which has a risk-attitude-adjusted utility of just over 87% as shown below in Equation (12) and Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Risk-Adjusted System Utility as a Function of Nominal System Reliability for an Example Maritime System.

Steps 2.1 and 2.2 are shown above and not called out separately in the example.

4.5. Step 3: Evaluate the System

Given the threshold reliability of 90% which maps to a risk neutral utility of 90%, this means the system and associated processes, as designed, are insufficient to achieve threshold reliability levels. For a system utility of 90%, assuming the risk attitude data remains constant, solving for x in Equation (10) indicates the redesigned system must have a reliability of at least 92.33%. To ensure the system achieves the desired utility, the engineer must find a method to improve the reliability of the system by over two percent.

4.6. Step 4: Adjust System Attributes

Having determined the required reliability value for a SOM risk attitude adjusted system, the systems engineer is presented with several options to improve the system. Modifying the system to improve reliability can be undertaken either by replacing components with higher reliability equivalents, or by adding redundancy to the design through parallel components or similar with the consequence of increased cost [19]. Redesigning the maintenance concept to improve reliability can be done by increasing preventative maintenance which effectively increases MTBF of system components at the cost of needing more manpower and consumables. Depending on the system and the original maintenance concept, there may be potential for a substantial increase in reliability. A maintenance plan resulting in a 50% greater MTBF yields the following shown in Table 5 which shows the system reliability improves by just over 3% with more intensive preventative maintenance.

Table 5.

MTBF Improvement by Maintenance Concept Modification for the Example System Over 500 Hour Operating Period.

Training is another effective way to reduce a system’s MTTR, which can provide more system uptime. Additionally, efforts may be undertaken to make improvements to administrative and logistics requirements. However, if no combination of the above approaches allows the system to reach the desired operational availability, improving the reliability may be unattainable without finding a group of less risk-seeking SOMs. From our own operational experience with maritime systems, we are aware of two options, though information surrounding the desirability and/or efficacy of either is beyond the scope of this article. The first option is to attempt to influence the psychology of the SOMs in such a way that their risk attitudes become acceptable. If changing the risk attitudes of the SOMs proves infeasible, the situation may warrant replacing the SOMs with SOMs who are less risk tolerant. This is often difficult for many reasons including the appearance of targeting specific groups whether intentional or unintentional, constraints on time to obtain replacements, or expenses associated with replacement. Finally, it simply may be that the position requires a great deal of specialized training which is difficult to acquire. In our opinion, replacing existing SOMs should only be undertaken as a last ditch effort to improve system reliability.

5. Discussion

As illustrated in the example, a systems engineer using the proposed method can gain insights into how risk attitudes of SOMs may impact operational availability of systems. We caution the interested practitioner that this method is only intended to provide guidance on potential issues with systems and SOMs not meeting operational availability targets due to risk attitudes of the SOMs. While the method provides some quantitative metrics to help inform decisions, the method is not intended to be used to make very detailed, precise, or accurate decisions on its own. Instead, we recommend this method to augment existing processes for evaluating and identifying issues with operational availability of systems.

A fundamental question this method asks is—do we design systems and then force SOM risk attitudes to align to our expectation, or can we take SOM risk attitudes into account from the beginning and design systems more appropriate to the SOMs. While the Navy and other large United States of America-based organizations often take the approach that SOMs must fit a specific risk attitude, this is not the only approach. Already, product and engineering design has been accounting for cultural differences among users. For instance, cultural changes between generations can result in new generations of SOMs not holding the same risk attitudes as their predecessors [62]. Similarly, SOMs in the United States of America may hold different risk attitudes than those in Greece or Germany [63,64]. Thus we suggest that systems should be designed to take into account SOM risk attitudes where practical.

The method and the example both focus on the impact of SOM risk attitude on system reliability; however, as mentioned previously, other contributors to the operational availability calculation (Equations (1) and (5)) may also be investigated using the proposed method’s general approach. We recommend that only one component of operational availability be investigated at a time to better differentiate effects of SOM risk attitudes on the components of operational availability.

While the method may be employed at the practitioner’s discretion throughout a system’s lifecycle, we developed the method to be used during the design phase of a system or the design phase of a system upgrade/overhaul/major maintenance cycle. However, information is needed from later in the system lifecycle—specifically the operational phase. In the event that a new system is being fielded and the proposed method is being used, we recommend using historical data from similar systems for specific data inputs such as component reliability data.

One limitation of the method is that it makes a jump between a purely risk neutral view of reliability (or other operational availability component) and the SOM risk-adjusted utility of the system from the perspective of reliability. This requires that practitioners are comfortable with comparing a risk neutral system utility with risk tolerant or risk averse system utilities. The background and related research section and the method both discussed some of the details of utility theory and why these assumptions are possible to be made. However, we must caution practitioners to remember that the risk-adjusted system utility is something fundamentally different than a reliability statistic that most systems engineers are familiar with.

The example provided in this article is limited in scope by design. While this method can work on very large, complex systems with many different groups of SOMs, we purposefully constrained the example to be small for ease of understanding. The generic maritime system is representative of many small systems aboard Naval vessels such as davit cranes, lube oil systems, fire water pumps, and other similar systems. The reliability statistics are generally representative of reliability of major components of systems aboard many military and civilian vessels. The DOSPERT data provided in the example is representative of what SOMs working on Naval systems may score. However, in all cases we have taken care to ensure that no sensitive data, statistics, or information has been included in this article.

We acknowledge that the scaling factor and the shaping factors are up to the discretion of the practitioner to determine. We have provided guidance in the method for these factors although selecting each of the scaling and shaping factors must be done on a system-by-system basis. This is in line with previous literature using similar approaches with engineered systems.

The method has been demonstrated through a small example; however, full validation and verification of the method has not been provided. The issue of verifying and validating systems engineering methods is an open question and a matter of some debate in the community. As a next step, we suggest the proposed method be used on an existing system to identify potential sources of less-than-anticipated reliability from SOM risk attitudes. This requires a large dataset that is open source and access to the SOMs in order for such an effort to be published in the open literature. While we do have access to systems data and SOMs, neither can be used for open literature and thus we have been unable to include such a validation here.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this article we presented a proposed method to take into account SOM risk attitudes to better understand how SOMs can impact operational availability. The proposed method can be used to identify potential avenues for system redesign or improvement to meet operational availability requirements by taking into account the risk attitudes of SOMs. An example of a maritime system was presented to demonstrate the method. While the method is targeted at the design phase of the system lifecycle and is only intended to provide a risk attitude-informed perspective as part of larger decision-making processes, we assert that the insights gained from the method are useful to the practitioner to help account for the risk attitudes of the SOMs who work with the system.

Future Work

Several areas of future work were identified in the course of this research. We suggest that an investigation into the applicability of the dimensions of DOSPERT as applied to naval systems and SOMs be undertaken to validate the assumption that DOSPERT is an appropriate risk attitude. While DOSPERT is meant to be field independent and many studies have validated DOSPERT’s applicability in many domains, no exhaustive study has been done demonstrating universality.

Another possible avenue of investigation is into the consistency of risk attitudes within large organizations such as the Navy and the Department of Defense. An analysis of sufficient sample size should reveal the presence, or absence, of common factors across a variety of metrics to include age, type of duty (sea or shore), duty location, gender, age, and point in the ship’s lifecycle among others. Furthermore, the investigation should include an analysis of risk attitude consistency over time. If the risk attitude of a population shifts appreciably over the life of the system, and if it changes in a consistent and predictable manner, such information should be taken into consideration during system design.

The MTBF distribution used in this article is exponential. Many other MTBF distributions are documented in the literature and many other utility functions using a variety of distributions are documented. Future work includes expanding the linkage between MTBF distributions and utility function distributions.

Several case studies using data from a variety of industries is a potential fruitful area of future work to demonstrate the applicability of the proposed method to a wider range of systems and enterprises. For instance, significant data is being captured by a variety of original equipment manufacturers in the heavy machinery sector. Similarly, commercial aerospace captures copious data from passenger aircraft. However, access to these data sources remains a challenge.

Author Contributions

Primary research and initial drafting of manuscript conducted by B.W.R. Advising of B.W.R. conducted by D.L.V.B., A.P., J.S. III. Manuscript preparation and major revisions by D.L.V.B. Manuscript review by A.P. and J.S. III. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Waeyenbergh, G.; Pintelon, L. A framework for maintenance concept development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2002, 77, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Kuswoyo, A.; Prabowo, A.R.; Suharyo, O.S. Developing strategy of maintenance, repair and overhaul of warships in support of navy operations readiness. J. ASRO 2020, 11, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Risk Management—Vocabulary; Guide; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- University, D.A. Operational Availability Handbook: Introduction to Operational Availability; Technical Report; Reliability Analysis Center: Rome, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, D.D.; Roedler, G.J.; Forsberg, K.J.; Hamelin, R.D.; Shortell, T.M. (Eds.) INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1118999400. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, B.; Fabrycky, W. Systems Engineering and Analysis; Prentice-Hall International Series in Industrial and Systems Engineering; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, G.A. Methodology for estimation of operational availability as applied to military systems. Int. Test Eval. Assoc. J. 2008, 29, 420–428. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, G.A. Methodology for Estimation of Operational Availability as Applied to Military Systems; Technical Report; U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command: Fort Leonard Wood, MO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Manov, M.; Kalinov, T. Augmentation of ship’s operational availability through innovative reconditioning technologies. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1297, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. Handbook of Reliability Engineering; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelock, L. Methods used to improve reliability in military electronics equipment. In Papers and Discussions Presented at the Dec. 8–10, 1953, Eastern Joint AIEE-IRE Computer Conference: Information Processing Systems—Reliability and Requirements; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1953; pp. 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Loman, J.; Vassiliou, P. Reliability importance of components in a complex system. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium Reliability and Maintainability, 2004-RAMS, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 26–29 January 2004; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Yang, X. A simple reliability block diagram method for safety integrity verification. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2007, 92, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coit, D.W. Cold-standby redundancy optimization for nonrepairable systems. Iie Trans. 2001, 33, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, S.V.; Dill, G. Redundancy optimization problem with warm-standby redundancy. In Proceedings of the 2010 Proceedings-Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), San Jose, CA, USA, 25–28 January 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.P.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Ye, W. Optimal condition-based maintenance decisions for systems with dependent stochastic degradation of components. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014, 121, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, L. Linking maintenance strategies to performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2001, 70, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, J.; Weismann, U.; Niggeschmidt, S. Calculation and optimisation model for costs and effects of availability relevant service elements. In Proceedings of the 13th CIRP International Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Leuven, Belgium, 31 May–2 June 2006; pp. 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Modarres, M.; Kaminskiy, M.P.; Krivtsov, V. Reliability Engineering and Risk Analysis: A Practical Guide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Monga, A.; Zuo, M.J.; Toogood, R.W. Reliability-based design of systems considering preventive maintenance and minimal repair. Int. J. Reliab. Qual. Saf. Eng. 1997, 4, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Merchant, G.S.; Crognale, S.J. Integrated Logistics Support Guide, 2nd ed.; Defense Systems Management College Press: Fort Belvior, VA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.M. A design for maintaining maritime superiority. Nav. War Coll. Rev. 2016, 69, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, O. Reducing Logistics Delays Using the Supply Chain Criticality Index: A Diagnostic Approach. Master’s Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, U.D.; Knezevic, J. Supportability-critical factor on systems’ operational availability. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1998, 15, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bossuyt, D.L.; Dong, A.; Tumer, I.Y.; Carvalho, L. On measuring engineering risk attitudes. J. Mech. Des. 2013, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bossuyt, D.L.; Beery, P.; O’Halloran, B.M.; Hernandez, A.; Paulo, E. The Naval Postgraduate School’s Department of Systems Engineering Approach to Mission Engineering Education through Capstone Projects. Systems 2019, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booher, H.R.; Minninger, J. Human systems integration in army systems acquisition. In Handbook of Human Systems Integration; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 663–698. [Google Scholar]

- Perrow, C. The organizational context of human factors engineering. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, B.S. Human Reliability, Error, and Human Factors in Engineering Maintenance: With Reference to Aviation and Power Generation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gertman, D.; Blackman, H.; Marble, J.; Byers, J.; Smith, C. The SPAR-H human reliability analysis method. US Nucl. Regul. Comm. 2005, 230, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens, C.D.; Hollands, J.G.; Banbury, S.; Parasuraman, R. Engineering Psychology and Human Performance; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bossuyt, D.; Hoyle, C.; Tumer, I.Y.; Dong, A. Risk attitudes in risk-based design: Considering risk attitude using utility theory in risk-based design. AI EDAM 2012, 26, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.R.; Weber, E.U. A domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2006, 1, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Masclet, D.; Colombier, N.; Denant-Boemont, L.; Loheac, Y. Group and individual risk preferences: A lottery-choice experiment with self-employed and salaried workers. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 70, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highhouse, S.; Nye, C.D.; Zhang, D.C.; Rada, T.B. Structure of the Dospert: Is there evidence for a general risk factor? J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2017, 30, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, J.M.; Smidts, A. Assessing the construct validity of risk attitude. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bossuyt, D.L.; Tumer, I.Y.; Wall, S.D. A case for trading risk in complex conceptual design trade studies. Res. Eng. Des. 2013, 24, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.H. Managing high reliability organizations. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1990, 32, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. Hundreds of Sailors Fight to Save U.S.S. Bonhomme Richard Before Fire Reaches Fuel Tanks. 2020. Available online: https://time.com/5866576/uss-bonhomme-richard-fire-damage/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Youssef, N.A. With USS Bonhomme Richard Fire Extinguished, Navy Turns to Inquiry of Blaze’s Spread. 2020. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/with-uss-bonhomme-richard-fire-extinguished-navy-turns-to-inquiry-of-blazes-spread-11594938399 (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Vanden Brook, T. Fire Extinguished Aboard USS Bonhomme Richard after Raging for 4 Days. 2020. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/07/16/fire-extinguished-navys-bonhomme-richard-after-four-days/5453829002/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Associated Press. Man Who Set Fire to Nuclear Submarine Gets 17 Years. 2013. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/03/15/nuclear-submarine-fire/1990663/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Maritime Training Advisory Board (US); United States Maritime Administration; Robert J. Brady Company; National Maritime Research Center (US). Marine Fire Prevention, Firefighting and Fire Safety: A Comprehensive Training and Reference Manual; DIANE Publishing: Darby, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- History.com Editors. The Normandie Catches Fire. 2009. Available online: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-normandie-catches-fire (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Larter, D.B. After the US Navy’s Bonhomme Richard Catastrophe, a Far-Reaching Crackdown on Fire Safety. 2020. Available online: https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2020/07/25/after-the-us-navys-bonhomme-richard-catastrophe-a-far-reaching-crackdown-on-fire-safety/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Fishburn, P.C. Utility Theory for Decision Making; Technical Report; Research Analysis Corp.: McLean, VA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, C.W. Notes on Attitude toward Risk Taking and the Exponential Utility Function; Technical Report; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, R.L.; Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Trade-Offs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Berhold, M.H. The use of distribution functions to represent utility functions. Manag. Sci. 1973, 19, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, D. A class of utility functions. Ann. Stat. 1976, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J.; Tellis, G.J. Removing social desirability bias with indirect questioning: Is the cure worse than the disease? ACR N. Am. Adv. 1998, 25, 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Lusk, J.L.; Norwood, F.B. Direct versus indirect questioning: an application to the well-being of farm animals. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 96, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshagen, M.; Hilbig, B.E.; Erdfelder, E.; Moritz, A. An experimental validation method for questioning techniques that assess sensitive issues. Exp. Psychol. 2014, 61, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkonen, A.; Glisic, B. Measurement of individual risk preference for decision-making in SHM. In Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring: Enabling Intelligent Life-Cycle Health Management for Industry Internet of Things (IIOT), IWSHM 2019, Stanford, CA, USA, 10–12 September 2019; pp. 1487–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Momen, N.; Taylor, M.K.; Pietrobon, R.; Gandhi, M.; Markham, A.E.; Padilla, G.A.; Miller, P.W.; Evans, K.E.; Sander, T.C. Initial validation of the military operational risk taking scale (MORTS). Mil. Psychol. 2010, 22, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanakis, S.H.; Solomon, A.; Wishart, N.; Dublish, S. Multi-attribute decision making: A simulation comparison of select methods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 107, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.z.; Xu, D.P.; Jiang, Y.C. Method of adaptive adjustment weights in multi-attribute group decision-making. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2007, 29, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, R.A. Decision analysis: Practice and promise. Manag. Sci. 1988, 34, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Namee, P.; Celona, J. Decision Analysis with Supertree; Scientific Press: South San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rolison, J.J.; Hanoch, Y.; Wood, S.; Liu, P.J. Risk-taking differences across the adult life span: A question of age and domain. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bossuyt, D.L.; Dean, J. Toward Customer Needs Cultural Risk Indicator Insights for Product Development. In Proceedings of the ASME 2015 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 2–5 August 2015. [Google Scholar]