Abstract

The global countryside constitutes a complex social–ecological system undergoing profound transformation. Understanding how such systems navigate transitions and achieve resilient, sustainable outcomes requires examining the interactions and adaptive behaviors of multiple actors. This study investigates the restructuring of rural China through a complex adaptive systems lens, focusing on the county of Lin’an in Zhejiang Province. We employ a middle-range theory and process-tracing approach to analyze the co-evolutionary pathways shaped by the interactions among three key agents: local governments, enterprises, and village communities. Our findings reveal distinct yet interdependent behavioral logics—local governments and enterprises primarily exhibit instrumental rationality, driven by political performance and profit maximization, respectively, while villages demonstrate value-rational behavior anchored in communal well-being and territorial identity. Crucially, this study identifies the emergence of a vital integrative mechanism, the “village operator” model, underpinned by the collective economy. This institutional innovation facilitates the synergistic linkage of interests and the integration of endogenous and exogenous resources, thereby mitigating conflicts and alienation. We argue that this multi-agent collaboration drives a synergistic restructuring of spatial, economic, and social subsystems. The case demonstrates that sustainable rural revitalization hinges not on the dominance of a single logic, but on the emergence of adaptive governance structures that effectively coordinate diverse actor logics. This process fosters systemic resilience, enabling the rural system to adapt to external pressures and internal changes. The Lin’an experience offers a transferable framework for understanding how coordinated multi-agent interactions can guide complex social–ecological systems toward sustainable transitions.

1. Introduction

The countryside and the city are interdependent yet distinct spatial entities, engaged in continuous reciprocal interactions [1,2,3,4], with rural areas characterized by lower population density, a primary reliance on agriculture, and distinct local customs [5], contrasting with urban hubs of dense population and advanced commodity-based civilization [6]. This distinguishing essence, termed rurality [4,7], has been diminished by the pervasive assimilation of urban traits into the countryside [8,9]. The countryside fulfills multifunctional roles—encompassing agricultural production, habitation, leisure, tourism, and ecological and cultural conservation [1,4,7,10]—which evolve with shifting urban-rural relationships, a process defined as rural transformation [4,5,7]. As frontrunners in urbanization and globalization, Western nations have experienced pronounced shifts in this transformation [1,4]. Beginning in the 1950s, agricultural protectionism for food security solidified the countryside’s primary production function [11], supported by subsidies integrating urban industrial outputs [12]. The 1970s oil crisis prompted a relocation of industry and population to rural areas [13], elevating the secondary and tertiary sectors [14] and marking the first rural transformation from a production countryside to a consumption countryside [8]. By the 1990s, counter-urbanization spurred demand for rural landscape, culture, and environment [1], driving a second transformation to a diverse countryside. Since the 21st century, globalization has deeply restructured these spaces through global flows of capital, labour, and culture [4,10,15], while digital networks blur spatial boundaries [16,17], constituting a third transformation towards a globalization countryside.

This study reconceptualises rural restructuring as the adaptive transition process within rural social–ecological systems, where internal elements and structures are reorganised under pressures like urbanisation and globalization [3,18]. This internal restructuring fundamentally drives the evolution of systemic properties and functions, with the resultant changed system state defined as rural transformation, establishing a clear causal linkage wherein restructuring is the mechanism and transformation the emergent outcome [3,18,19]. Western nations have undergone three corresponding phases of rural restructuring. The first, economically dominated phase, commenced in the 1970s following post-war agricultural industrialisation via subsidies [11,12]. The oil crisis and ensuing surpluses accelerated the shifting of manufacturing to the countryside to lower costs [20], pulling labour into non-agricultural sectors [11] as new capital and industries penetrated rural areas [8,13]. Subsequent deindustrialisation and offshoring in the 1980s prompted an economic restructuring from manufacturing to services [21,22], marking a territorial shift driven by production factors [23]. The second, socially dominated phase, beginning in the 1990s, was shaped by counter-urbanisation. Middle-class in-migrants, possessing economic and cultural capital, engaged in rural space reproduction, often marginalising incumbent groups [24] and reshaping landscapes and social structures alongside a sustainability-focused policy turn. This led to gentrification and a social restructuring that reoriented development from original residents towards newcomers, altering territorial structure based on demography and social relations [1,8,24]. The third phase, unfolding since the early 21st century, is led by globalisation. Factor flows (e.g., capital, labour) transitioned from national to global networks [15], profoundly transforming the countryside [10] and globalising its key elements [4]. New actors, including multinationals and international migrants, entered [17], fostering novel industries [16] and altering socio-environmental relations [25], ultimately transforming Western rural areas into multi-subject, multi-dimensional hybrid network spaces [15,26].

In contrast to the sequential progression observed in Western nations, rural restructuring and rural transformation in developing countries like China are characterized by parallel, compressed development [3,18]. Different rural areas experience distinct types of restructuring, often simultaneously [18,27], driven by the compounded effects of urbanization, industrialization, counter-urbanization, and globalization [19,27]. This results in spatio-temporal parallelism and compression, where phases like production, consumption, diversity, and globalization in the countryside may co-occur [28,29]. Existing scholarship extensively examines this process in rural China, focusing on three interconnected dimensions. Studies on spatial restructuring/transformation analyze changes in rural spatial form, emphasizing drivers like land policies (e.g., land consolidation), urbanization, and industrialization [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Research on economic restructuring/transformation explores shifts in agricultural modes—from labor-intensive to land-intensive production or land abandonment—due to labor outflows and economic incentives [38,39,40,41,42], alongside new rural industries like e-commerce and tourism [43,44]. Finally, studies on social restructuring/transformation investigate the profound impacts of population mobility: outflow leads to curtailed public services and attenuated community resilience [45,46,47,48], while inflow can trigger community isolation and power structure changes [36].

While the spatial, economic, and social dimensions of rural restructuring in China have been extensively studied, key gaps persist when examining this process through the lens of complex social–ecological systems. Although the rural territorial complex is recognized as an integrated regional system [18], there remains a limited understanding of the co-evolutionary dynamics through which its key constituent agents—governments, enterprises, and villages—interact to reconfigure resources and functions [49]. Specifically, current research often lacks a framework that treats these interactions as the core driver of systemic transformation. To address this, this article investigates the following research question: How do external forces (e.g., state and market) enter the rural system, how do internal actors of the system (e.g., communities) respond, what are their respective behavioral logics, and how does their interaction reconfigure the structure and functions of the system? Addressing this question is crucial for deciphering the endogenous mechanisms of rural transformation in developing countries. It elucidates how the entry of external governmental and market forces, coupled with the strategic responses of internal communities, co-produces the restructuring process. This analysis reveals the interactive dynamics through which the rural system evolves, navigating its inherent multifunctionality and engaging with the forces of globalization to forge a new developmental pathway.

2. Analytical Framework and Methodology: A Complex Adaptive Systems Perspective

2.1. Analytical Framework: Process-Tracing Approach

To decipher the non-linear and emergent processes of rural transformation, this study adopts an integrative analytical perspective that bridges the conceptual richness of middle-range theory with the dynamic, interactive lens of Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS). Middle-range theory posits that observable social phenomena are often shaped by the interplay of multiple actors operating within a specific social field, each guided by distinct behavioral logics [50]. This provides a crucial antidote to the tendency in social science research toward minimalist theoretical models, which can result in oversimplified generalizations of complex social processes and limited explanatory power [51]. For instance, extant research on rural governance often isolates singular logics: some studies focus exclusively on state-led financial projects, highlighting resource misallocation driven by political performance objectives [52]; others concentrate on the inflow of industrial capital, emphasizing profit-driven enterprises potentially exploiting rural households [53]; while still others focus on internal communal circles, underscoring the integrative role of rural collectives [54]. While valuable, such isolated perspectives exhibit a certain one-sidedness, failing to capture how these co-existing and often competing logics interact to produce systemic outcomes.

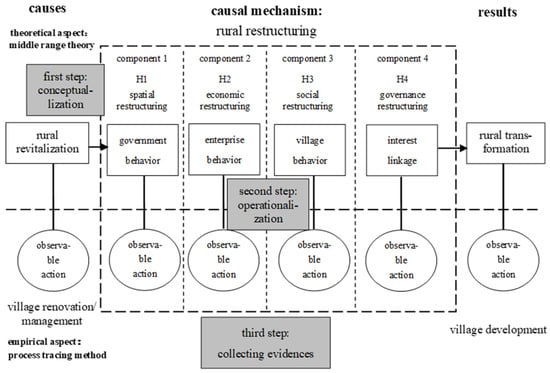

This article proposes that rural areas constitute CAS, where the adaptation and interactions of heterogeneous agents (governments, enterprises, villages) drive system-wide transition. To analyze this, we develop a multi-agent logic framework (see Figure 1) that integrates CAS principles. This framework offers a holistic perspective by treating rural restructuring not as a monolithic process, but as the co-evolutionary reconstitution of interconnected subsystems—spatial, economic, social, and governance—each primarily catalyzed by a different agent’s core logic.

Figure 1.

Analytical Framework and Methodology.

Methodologically, we employ a theory-testing process-tracing approach to rigorously examine the historical sequence and causal mechanisms within our case [55]. This method is particularly suited to answering “how” and “why” questions about the emergence of outcomes in CASs, as it allows for the detailed examination of causal chains and the role of agency within a specific context. The research process follows three steps: first, conceptualizing the hypothesized causal mechanism linking multi-agent interactions to systemic transformation; second, operationalizing this mechanism into testable, empirical manifestations; and third, gathering and analyzing historical evidence to assess the validity of the proposed theoretical pathway. This approach enables us to trace how the discrete behaviors rooted in each agent’s logic (e.g., government spatial planning, enterprise investment, village communal action) interact and become linked over time, potentially giving rise to higher-order emergent properties, such as adaptive governance structures and systemic resilience.

2.2. Case Selection and Data Collection: Theory-Testing-Oriented Fact Collection

The article conducts a typical case study and collects factual evidence to test the above theory. Lin’an is located in western Hangzhou and strategically positioned within the core circle of the Yangtze River Delta, with tight transportation links to Shanghai, Hangzhou, and other megacities. Specifically situated in the Tianmushan mountainous region of northwest Zhejiang, Lin’an enjoys an abundant supply of high-quality landscape resources. Lin’an is selected for two principal reasons: process completeness and regional typicality. First, it provides a complete, two-phase sequence of village renovation (2003–2015) and subsequent management (2016–present), ideal for process-tracing analysis. Second, it embodies the spatially parallel and temporally compressed rural restructuring characteristic of contemporary China, where urbanization, industrialization, and globalization exert simultaneous pressure. Located in the Yangtze River Delta yet rich in ecological resources, Lin’an exemplifies the complex transition from a production-oriented countryside to a multifunctional landscape of consumption and tourism, making it a representative case for studying systemic rural transformation.

Data were collected through participatory observation and semi-structured interviews to capture the multi-scalar dynamics of rural restructuring. Fieldwork, conducted between 2022 and 2024, engaged stakeholders across administrative levels. This included nine key departments (e.g., Rural Affairs Office, Bureaus of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Culture & Tourism), six townships/sub-districts (e.g., Xitianmu), and over twenty villages (e.g., Jiusi Village). In-depth interviews were held with more than twenty village cadres, over thirty rural operators (e.g., developers, homestay owners), and approximately eighty villagers. The interviews explored actors’ perceptions, decision-making logics, and experiences of change. Participatory observation of village environments and community activities provided contextual depth. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, supplemented by field notes and photographic documentation for analysis.

3. Theoretical Analysis: Co-Evolutionary Dynamics of Multi-Agent Logics in Rural Transformation

From the functional perspective of the middle-range theory, social groups are influenced by social structure and fulfill distinct social functions. However, when there is a lack of or conflict in the institutional system, individuals or groups may exhibit deviant behavior [56]. The methodology of the middle-range theory is used to test the positive and negative functions of the system. In the context of rural restructuring, governments play a role in providing public goods/services, enterprises contribute to offering private goods/services, and villages serve as providers of community goods/services. Nevertheless, these functions are susceptible to deviations due to their interaction with governance structures [56]. Such deviations are evidenced by specific societal issues related to public or private capital inflow into rural areas [57,58].

3.1. Government Logic: Instrumental Rationality for Performance

The system of government in China is characterized by bureaucracy, which shares similarities with Western countries. However, it differs in that China operates under a unitary system where higher levels of government exercise ultimate control over lower levels, including official appointments, financial allocations, and performance evaluations [59]. The behavior patterns of local governments in China are profoundly influenced by vertical relationships between superiors and subordinates and horizontal relationships among peers [57]. Lower-level executive behavior revolves around the core political tasks of higher-level concerns. To secure an appointment or promotion, officials must obtain a positive performance evaluation. Furthermore, the strength of their political performance is contingent upon securing robust financial support [57]. Since the implementation of fiscal reforms by the central government in 2004, fiscal power has become increasingly centralised through a system of special projects, with financial allocations centred on core political tasks [58]. Correspondingly, the project system, as a novel tool of governance, has gained extensive application in administrative practices [57,58]. At the same level, local governments compete fiercely in performance evaluation tournaments to win over peers. Motivated by this, local governments actively strive for and implement fiscal projects. The features of the project system can be summarized as layers of subcontracting: central and provincial level contracting, county-level packaging, and township and village level capturing. From the perspective of intergovernmental relations at the same level, local governments engage in intense competition during political performance evaluation. The competitive mode is referred to as a promotion tournament [57]. The fierce competition between governments at the same level is manifested through a “pressure system”. Higher-level governments often add core political tasks to shift pressure to lower levels in order to outperform other peer governments and successfully achieve their core political goals.

In 2005, the central government made a decision to terminate the long-term development strategy of “agriculture feeds industry and countryside supports cities” and instead proposed a new adverse strategy of “industry feeds agriculture and cities support countryside” [2]. Subsequently, the central government has implemented significant policies such as new rural construction, beautiful rural construction, poverty alleviation, rural revitalization, and common prosperity. Consequently, both the central and provincial governments have consistently directed financial resources and projects into rural areas [52]. It implies that projects from superior governments are implemented in rural areas. Given that these are fundamental political objectives of the central and provincial government, local governments attach great importance to “rural projects” in order to compete with their peers during political performance evaluations [58]. They meticulously complete declaration forms and actively strive for superior support. Once substantial project funds enter villages, they exercise positive social impacts: (1) Rural infrastructure will be enhanced thanks to support for initiatives like rural roads, water conservancy for farmland irrigation, as well as general water conservation; (2) Living environment in rural areas will improve due to initiatives such as new rural construction; (3) Postal services along with banking facilities will become more accessible resulting in an improvement in logistics conditions. The aforementioned projects have made significant contributions to the rural spatial restructuring, enhancement of living environments and facilities in villages, as well as the promotion of rural industrial revitalization. However, it is regrettable that these projects primarily focus on political performance evaluation, which may lead to neglecting industrial management needs after project investment. In summary, the following hypotheses are derived:

H1.

Government-led projects in rural areas have an impact on rural revitalization.

H1.1.

Government-led projects in rural areas provide physical foundations for rural revitalization.

H1.2.

Government-led projects in rural areas are inclined not to align with the actual needs for rural revitalization.

3.2. Enterprise Logic: Market Rationality for Profits

Enterprises are the creators of social wealth [60]. Entrepreneurs identify market opportunities, assume market risks, establish industrial or commercial enterprises, integrate production factors, form production functions and market products, meet market demand, and achieve substantial profits [61]. Entrepreneurship encompasses the identification of market opportunities, assumption of market risks, innovation in production methods, development of marketable products, and design of business models [60,61]. The driving force behind advancing social productivity lies in the successive changes in production modes led by entrepreneurs, which consistently foster innovation in scientific research, technology development, product design, and business models [62]. Since 2005, with the central government increasingly directing financial resources into rural areas—particularly after strict regulations were imposed on the urban real estate sector—the surplus industrial and commercial capital in cities has gradually shifted to explore new market opportunities in rural areas [28]. The mainstream of this capital flow has progressively transitioned from agriculture to non-agriculture sectors, notably through utilizing rural land for integrating three rural industries. Currently, the primary domain for capital inflow into rural areas involves leveraging rural land to facilitate mixed-industry management encompassing agriculture, culture, and tourism [43].

When urban enterprises engage in industrial management in rural areas, they establish an interest linkage between the village and the outside markets. Market activities of enterprises outside the village mainly adopt modern contract modes, while production activities within the village primarily rely on traditional identity modes [52]. To accurately identify market demand from urban residents in rural areas, targeted development of market products is necessary for enterprises to operate outside the village. It is achieved through exhibitions, trade fairs, TikTok and other online and offline marketing strategies that attract customer flow [44]. Common rural consumption products include real estate for elderly care, parent–child activities, research and learning activities, business meetings, weekend vacations, cultural travel activities, as well as featured sports events. In the internet era, combining online and offline marketing strategies is key to enterprise survival and growth by attracting network popularity flow with characteristic rural products supported by sales networks [44]. Within the village, rural land and housing can be rented to facilitate the employment of surplus labor from rural areas, as well as attract capital, management, technology, and other production factors to create rural products and services that cater to the needs of urban residents [43]. The utilization of rural land and housing is contingent upon the level of value-added business activities. Common business types include various aspects of the tourism industry: accommodations for tourists, catering services tailored to their needs, diverse leisure experiences, as well as initiatives promoting rural culture and fostering innovation. Therefore, directing the industrial and commercial capital into the countryside results in rural economic restructuring.

The heterogeneous business activities of industrial and commercial enterprises, both within and outside the village, attract urban residents to consume in rural areas [28,43]. While the village operator is responsible for planning and constructing the overall business environment, it is primarily the village investors who design and create individual consumption environments. These commercial activities generate opportunities for local villagers to increase their income. However, due to their strong market position, it is possible that urban industrial and commercial capital pursues monopoly profits while unintentionally or intentionally excluding local villagers from participating in these business processes [53]. Consequently, the economic benefits that could have been captured by rural management are instead appropriated by industrial and commercial capital, leaving local villagers as passive observers of rural revitalization. In summary, the following hypotheses are derived:

H2.

The influx of industrial and commercial capital into rural areas has a significant impact on rural revitalization.

H2.1.

The influx of industrial and commercial capital into rural areas is conducive to increasing the income of local households.

H2.2.

The influx of industrial and commercial capital into rural areas tends to exclude or marginalize rural households.

3.3. Village Logic: Value Rationality and Communal Adaptation

Villages of China are characterized by their traditional and isolated nature, functioning as acquaintance societies. Social communication within these villages is primarily based on blood relations, geographical proximity, and occupational cooperation [63]. The density of social interaction and level of mutual assistance among internal members depend on the closeness of their social relationships. The closer the social relationship is, the deeper their responsiveness to requests for help from villagers [54]. Given the high risk and low value associated with agricultural production, villagers rely on an internal mechanism of social assistance to cope with unpredictable family risks [64]. In times of difficulty, they can seek timely support from their community. Village society operates based on public order and traditional customs rather than laws or policies from the government. Thus, when faced with social disputes, villagers often turn to village authorities for mediation instead of resorting to external legal proceedings [63]. Villages tend to exclude outsiders, resulting in relatively high transaction costs for property transactions between the village and external entities due to a lack of social trust. However, with the assistance of village authorities, these transaction costs can be effectively reduced, particularly when large-scale property transactions occur [54]. It is crucial that property transactions within and outside the village prioritize the development interests of the community; otherwise, internal boycotts may hinder external businesses from operating within the village. In terms of managing village industries, public order and traditional customs significantly diminish the effectiveness of urban property law and contract law [65]. To enhance anticipation and security in property transactions, collaboration with village authorities facilitates enterprises outside the village in renting necessary rural land and houses for their operations while also mediating any disputes that may arise during the process [54]. Concurrently, the village community has further fortified social interactions and enhanced the existing governance structure in the process of addressing transactions and disputes involving investors within the village. In other words, redirecting capital from government and enterprise into rural areas results in rural social restructuring. Nevertheless, if foreign enterprises fail to adequately contribute to the development interests of the village, internal cohesion will pose challenges for their industrial operations. In summary, the following hypotheses are derived:

H3.

The social order within a village has a significant impact on the operations of external enterprises.

H3.1.

Successful collaboration between villages and enterprises results in reduced operating costs for external enterprises.

H3.2.

Failure of village-enterprise cooperation significantly escalates operating costs for external enterprises.

3.4. Interest Linkage: Mitigating Conflict and Enabling Coordination

It is imperative for the government, market, and village to collaborate effectively to revitalize idle rural assets through integrated governance [49]. However, when the government assumes a dominant role while enterprises and farmers remain passive bystanders, the rural governance systems become dysfunctional and governance failures become inevitable [52]. In the process of China’s transition from a planned economy to a market economy, the government strategically fosters both the market and social community by gradually relinquishing its control over them. Consequently, China has successfully undergone a transformation from an imbalanced governance structure characterized by “strong government, weak market, and weak society” to a more balanced governance structure featuring “strong government, strong market, and strong society” [57]. The reutilization of idle rural resources necessitates the presence of an effective government, which entails a delineation of powers to constrain administrative actions and a list of responsibilities to compel active provision of public goods for rural areas [65]. The efficient functioning of markets is crucial for activating idle rural resources, with enterprises playing a pivotal role in acquiring production factors at minimal transaction costs and conveniently offering differentiated products or services to urban residents [28,66]. To prevent environmental degradation or exploitation of rural interests, it is imperative to establish a negative list that restricts enterprise activities [65]. An organic society is essential for revitalizing rural idle resources, with villages serving as familiar communities governed by public order and traditional customs [54]. Only by developing a robust collective economy can village authorities be empowered, enabling enterprises to access production factors such as rural land and houses from villages at reduced transaction costs [65]. A balanced interest linkage mechanism is necessary for the cooperative management of idle rural resources, with a focus on controlling the deviant behavior of governments and enterprises [65,67]. Industrial management can bring tangible benefits to both rural households and the countryside, while government and business work closely with villages [54]. The rural collective economy serves as a key interface for integration among government, enterprises, and villages [54]. Therefore, fostering a strong rural collective economy contributes to establishing a more equitable interest linkage mechanism. In other words, the infusion of capital from both the government and enterprises into rural areas leads to a restructuring of rural governance. As a result, a cooperation network is formed among the government, enterprises, and villages. The diverse modes of cooperation among these three entities give rise to different forms of network governance. In summary, the following hypotheses are derived:

H4.

The interest linkage has an impact on the industrial management of idle resources in rural areas.

H4.1.

A close and comprehensive interest linkage promotes the industrial management of idle resources in villages.

H4.2.

A loose and isolated interest linkage hinders the industrial management of idle resources in villages.

4. Case Analysis: Process-Tracing the Transformation from Resource Revitalization to Adaptive Governance in Lin’an

The case study of Lin’an is consciously integrated with the macro context of Zhejiang’s Green Rural Revival Program (GRRP). It is noted that the case study employs a macro-to-micro approach. At first, the article delineates the overall context of Zhejiang’s GRRP. Subsequently, it outlines Lin’an’s execution in both village renovation and management phases. During the case analysis of Lin’an, an overview is provided about its general situation first; then, a description of the development of typical villages follows. The Jiusi village serves as an outstanding example for village renovation, whereas the LongMenMiJing (LMMJ) project exemplifies village management.

4.1. Case Context: The Green Rural Revival Program as an Exogenous Trigger

Zhejiang’s GRRP can be categorized into two stages: (1) village renovation (2003–2016). It was initiated by the government of Zhejiang province in 2003 with the objective of transforming the unsanitary and unfavorable living conditions in rural areas through village renovation, ultimately aiming to establish a comprehensive well-off society. In 2010, the government of Zhejiang province continued the program and upgraded it to the beautiful countryside movement. Governments took charge of planning, designing, constructing, and evaluating village renovation projects while enterprises and villages played cooperative roles. (2) village management (since 2016). It was commenced in 2016 when the government of Zhejiang province decided to further deepen the beautiful countryside movement by enhancing renovation standards and expanding its spatial scope. In 2017, a rural initiative was launched for 10,000 scenic spots to build 1000 Class-3A scenic spot villages and 10,000 Class-A scenic spot villages. The initiative aimed at exploring a market-oriented approach for government investment in rural public assets while converting natural beauty resources into economically prosperous assets. In 2021, GRRP was elevated into a common prosperity initiative as it had successfully established a novel model for village management where collaborative governance among governments, enterprises, and villagers is fostered. In conclusion, sustaining village renovation in rural areas solely through financial projects poses challenges. The success of village renovation and the construction of a beautiful countryside relies on external assistance and lacks the capacity for independent and endogenous development. Implementing village management based on multi-actor interest linkages demonstrates inherent vitality, while public and private capitals jointly facilitate independent and endogenous development, thereby transforming valuable resources into a prosperous economy.

4.2. Phase 1: Village Renovation (2003–2015)—Spatial Reordering and Physical Foundation

(1) Government actions. The period from 2003 to 2015 witnessed a significant government-led environmental improvement, marking the stage of village renovation. In this context, Lin’an initiated and executed village renovation and beautiful countryside construction movement. The objective of the movement was to achieve a “green home, rich and beautiful mountain village” through classified transformation. Villages were deliberately divided into boutique villages, feature villages, and renovation villages based on the principle of classified disposal. The objective for boutique villages was to embody highlights, characteristic villages to accentuate distinctive features, and renovation villages to showcase transformations. At this stage, governments provided financial project funds as subsidies for environmental improvement and beautification in order to transform the rural landscape. From the perspective of government behavior characteristics, the project was incorporated into the rural areas under the political performance evaluation mechanism. Office of Agricultural and Rural Affairs of Lin’an CPC (OARA) primarily led projects of village renovation and beautiful countryside construction, which were managed as construction projects in collaboration with various governmental departments and townships. OARA took charge of project planning, design, implementation, quality inspection, and performance evaluation. Local governments were responsible for administrative decision-making and implementation procedure while enterprises handled technical affairs such as planning, design, and project execution. The successful bidder was determined through legal procedures at the public resources trade center of governments. GRRP served as a core political task where OARA actively coordinated substantial project funds to be invested in rural areas while towns, villages, and enterprises cooperated in its implementation, resulting in a transformation from dirty and poor living environments to green-rich beautiful villages. Owing to exceptional performance from 2004 to 2015, Lin’an was consecutively awarded as an advanced organization in GRRP evaluation within Zhejiang province for more than ten years. In the case of the JiuSi Village, OARA implemented comprehensive projects of village renovation in collaboration with the XiTianMu Township, the JiuSi Village Committee, and the construction enterprise, aiming to enhance infrastructure and improve living conditions. To achieve the objective, three initiatives had been implemented, namely the “demolition campaign”, the “wall revolution”, and the “green action”. The “demolition campaign” aimed to demolish dilapidated houses, old houses, and attached houses in accordance with the principle of mandatory demolition for environmental remediation. The “wall revolution” focused on renovating old walls and vegetable gardens along the main road to create a visually appealing landscape on both sides of the road. The “green action” involved renovating individual households’ courtyards to comprehensively enhance the quality of the village environment.

(2) Enterprise actions. Enterprises that ventured into rural areas primarily collaborated with the government in planning and engineering of village renovation. However, some enterprises also integrated GRRP to utilize idle rural resources, as exemplified by the LianZhong corporation and its pioneering “LianZhong” mode. The innovative approach effectively tapped into Shanghai’s substantial demand for rural holiday consumption while capitalizing on Lin’an’s abundant rural resources and favorable environment. The approach of the “LianZhong” mode in the case of JiuSi Village is described as follows: In supply side, LianZhong acted as the initiator and entered into business contracts with rural households. The rural households provided land while LianZhong provided funds. Subsequently, the rural households applied for housing demolition and construction permits, and LianZhong organized activities of design and reconstruction. Upon completion of the rural house reconstruction, LianZhong freely offered new housing units to the rural household. It is noted that these housing units were typically located on the first floor and have a similar size to his original building. In return for this provision, LianZhong obtained a share in utilizing these houses. Generally situated from second to fourth floors, these houses were subject to a 30-year contract period after which they will be returned to the rural households without any cost incurred. Additionally, LianZhong paid a monthly labor fee (usually about 500 RMB) to the rural household for his property service. In consumption side, LianZhong signed lease agreements with urban residents by selling them use rights for these houses as an intermediary entity in Shanghai and other megacities, so that citizens residing in rural areas specifically catering towards elderly individuals. LianZhong played an important role in connecting urban and rural areas as an intermediary. Under the premise of safeguarding the interests of rural households, the LianZhong mode effectively facilitated mutual benefits among local households, foreign enterprises and citizens. Rural households accrued property and labor advantages, urban enterprises attained business benefits, while urban citizens enjoyed an affordable rural lifestyle. The renowned “LianZhong” mode had garnered extensive media coverage both in the Yangtze River Delta and nationwide. Subsequently, numerous imitators emerged in the TianMu mountain area of Lin’an. Initially, local governments tacitly endorsed the LianZhong mode; however, some imitators later violated land use regulations by constructing houses that encroached upon farmers’ interests. Consequently, local governments gradually intensified control measures to curtail the proliferation of the mode.

(3) Village actions. The primary role of the villages lied in collaborating with the government to facilitate village renovation and enhanced the aesthetic appeal of villages. However, they did not actively contribute towards utilizing idle resources. In instances where farmers’ interests were infringed upon by enterprises, it stimulated a collective response from the entire village society, leading to exclusionary behaviors against foreign enterprises and rendering industrial management for them challenging. From the standpoint of rural households, when they lacked market operation capabilities, they had the option to engage in partnerships with external enterprises to augment their income. In the case of the JiuSi Village, Wang Miaohua (the secretary of the village committee of CPC) and three other rural households sought collaboration with LianZhong while establishing the LianZhong mode. Apart from gaining complimentary access to newly constructed rural houses within the same area, these rural households provided property services for external enterprises and received a monthly remuneration of 500 RMB as labor fees—resulting in an annual increase of 6000 RMB. Additionally, rural households generated supplementary income by selling local specialties such as chicken and dried bamboo shoots to urban residents in the village, thereby increasing their annual earnings by nearly 20,000 RMB. When rural households possessed market operation capabilities, they would select suitable industries for business ventures. For instance, Wang Miaohua’s two sons had acquired expertise in the catering industry while working in the city. They identified new business opportunities through collaboration with LianZhong and utilized their newly constructed rural houses to operate their enterprise in their hometown, resulting in an annual income increase of almost 100,000 RMB. The statistics provided by the JiuSi village indicate that LianZhong had signed contracts with 23 households, while 7 households had chosen to seek company assistance in Shanghai for reconstruction purposes; the remaining houses remained unchanged, within ZhuTuoLing (a natural village of the JiuSi village), which consists of 40 households.

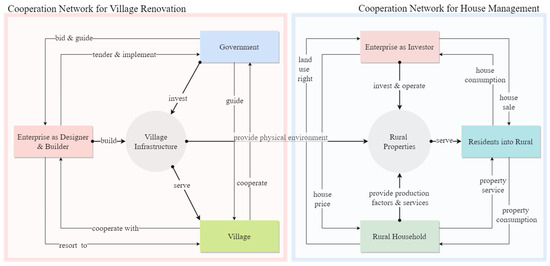

(4) Interest linkages. The interests of governments, enterprises, and villages were loosely interconnected, lacking a comprehensive cooperative network. Firstly, the government established an interest linkage with enterprises and villages in project investment and construction, while enterprises and villages collaborated with the government in these endeavors. Although the government’s financial projects contributed to creating a favorable habitat environment, their operational logic primarily revolves around political performance evaluation under administrative management. The selection and implementation of projects often neglected considerations for future industrial management requirements, resulting in a surplus of idle government investment assets. Secondly, the enterprises directly formed the interest linkage of individual rural housing management with the rural households without involving villages as intermediaries. Enterprises engaged in direct benefit exchanges with the individual rural households while assuming responsibility for mediating business disputes that arise between citizens, rural households, and themselves. Villages played a passive role by cooperating with government and business activities. While enterprises proactively took advantage of public assets invested by the government, they also tended to violate management regulations at times, which infringed upon farmers’ interests and led to social conflicts during their operations. In the case of JiuSi Village, OARA, the XiTianMu Township, the JiuSi Village Committee and the bid-winning enterprise jointly conducted the village renovation project; LianZhong and villagers of ZhuTuoLing jointly carried out the revitalization of rural housing (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interest Linkages of Village Renovation in Lin’an (2003–2015).

4.3. Phase 2: Village Management and Operator Model (2016–Present)—Institutional Innovation and Economic Integration

(1) Government actions. Lin’an initiated a rural management policy in 2016, which encompassed two primary aspects: hardware (infrastructure development) and software (institutional establishment). As for hardware, OARA continued to take the lead in investing in creating picturesque villages. As for software, it consisted of two components: village management promoted, respectively, by the tourism department and agriculture department. The tourism department promoted open village operations to external entities through attracting and employing village operators from society as a whole, thereby achieving a tight integration between villages and markets while identifying viable approaches to strengthen communities and improve livelihoods. Village operators leveraged their resources by transforming them into products and services that catered to urban needs through operational planning, business model introduction, investment promotion, and marketing efforts. The tourism department oversaw village operators in terms of recruitment as well as performance evaluation. In terms of recruitment, village operators were primarily expected to possess the capacity for strategic cultural creation, resource acquisition and management, operational proficiency, and marketing expertise while embodying a deep understanding of rural contexts and demonstrating an artisanal spirit. In terms of evaluation, a comprehensive method had been devised encompassing 42 items across 7 dimensions with a total score of 200 points. These 7 dimensions included positioning and planning, institutional frameworks and mechanisms, product development, distinctiveness and integration strategies, effective management practices and training initiatives, successful marketing approaches leading to performance outcomes, as well as service provision quality assurance. According to the evaluation results (120, 140, 160, 180 points), the government provided financial incentives of 100,000, 300,000, 500,000 and 700,000 RMB, respectively, to eligible operators. Non-compliant operators were required to exit the market. The internal reform of village management, promoted by the agriculture department, encompassed the following key measures: firstly, implementing the reform of property rights system for rural collective economic organizations; secondly, establishing cooperative economic companies; thirdly, enhancing the governance structure of rural collective economy; fourthly, strengthening the management of village assets; and finally, creating favorable conditions for villages to undertake government projects in rural areas and engage in external cooperative operations. In the case of the LMMJ project, the multiple departments coordinated their actions to create conditions for village management. OARA was responsible for implementing projects such as the DaYu line of village road and the renovation of three villages of ShiMen, LongShang, and DaShan. The tourism department attracted local village operator Min Lou to design the LMMJ project for industrial operation. The agriculture department promoted reforms in the rural collective property rights system in the three villages.

(2) Enterprise actions. A village operator was responsible for holistic management of a village, while an individual investor focused on the individual operation of a rural house. Once a village operator entered a village, he or she undertook holistic management based on its unique features, creating a conducive business environment and flourishing rural industries: (1) Conducting resource surveys: Village operators began by thoroughly understanding the background and characteristics of each village through survey lists, thereby clarifying the industrial theme and market positioning. (2) Assembling a competent team: Village operators actively sought talents in planning, construction, copywriting, marketing, finance, and general management. (3) Developing thematic plans: Creativity played a pivotal role as operators meticulously plan distinctive industrial themes that served as the lifeblood of an attractive economy. The aim was to achieve unity within each village while preserving their individuality. For instance, the LMMJ project emphasized boutique homestays while the YunShang-BaiNiu project focused on folk experiences. (4) Attracting investments through business activities: Village operation followed an asset-light mode where operators concentrated on overall planning and management. By accurately attracting various individual investors according to local resource characteristics and investing in small yet exquisite ventures within villages (such as homestays, pick-your-own gardens, wood art workshops), Lin’an had successfully established additional attractions like wine workshops, art galleries, village bars, straw shoe halls, and rice cake workshops. (5) Marketing: Village operators employed market-oriented, Internet-style integrated marketing strategies both online and offline to precisely target potential customers for village products. This included devising various agricultural tourism activities, integrating new media publicity, and managing WeChat public accounts dedicated to rural products. (6) Social cooperation: With external support, village operators strengthen collaborations with network marketing organizations, TikTok teams, university training institutions, and enterprise associations. Additionally, individual investors specifically lease housing units from rural households for individual commercial operations while cooperating with village operators to establish a conducive business environment.

In the case of the LMMJ project, the village operator leveraged the natural resources of the three villages, including rural land, houses, forests, and streams, to design and develop scenic spots such as ancient villages, rock walls, stone henges, pine forests, terraces, and camping sites along the road of the Dayu line. These developments have led to the initiation of various tourism activities, such as traditional village tourism, rock climbing, geological heritage appreciation, mountain stream viewing, pine forest appreciation, terrace agriculture observation and experience, and stargazing. The scenic area as a whole had successfully established a total of six upscale homestays, forest cabins, and inns, offering 600 beds through its own investment or investment promotion. Additionally, it had developed six facilities, including the Folk Culture Hall, Nostalgia Memory Hall, and Rock Climbing Museum, as well as a Folk Snacks Experience Hall, Local Specialty Supermarket, Craft Beer Bar, Terrace Train, Conference Center, Music Barbecue, and other tourism-supporting amenities. Collectively, these attractions had constituted an integrated rural industrial cluster. The project had attracted over 150 million RMB in industrial and commercial capital, encouraged more than 40 young people to return to their hometowns and start businesses, created over 200 new job opportunities, and increased the village’s collective income by 4.27 million RMB and the villagers’ per capita income by 2400 RMB.

(3) Village actions. A village established an enriching village company (EVC) in accordance with the principles of property rights reform for rural collective economic organizations, to enhance the verification of collective assets, improve the governance structure of collective organizations, and strengthen the operational capacity of the collective economy. Management of an EVC was divided into external and internal aspects. As for the external aspect, an EVC collaborated with a village operator to conduct village operations by investigating and consolidating various idle resources in the village, particularly unused land and houses. A joint venture was constantly established with the village operator, utilizing social capital from within the community to consolidate idle land and houses in the village. This facilitated resource integration with the village operator in a comprehensive manner, avoiding fragmented transactions between the operator and the villagers, thereby reducing transaction costs. In cases where conflicts arose between foreign operators and local households over interests, an EVC acted as an intermediary to mediate these contradictions. It internally assumed the responsibility of executing government-funded village renovation projects. By leveraging the EVC as an entity, the project activated and utilized local labor resources to effectively implement the government’s village renovation initiatives, thereby enhancing both collective and individual income. Since villagers directly benefited from these renovation projects, government supervision costs can be significantly reduced through entrusting a local project to an EVC. The symbiotic relationship between internal and external interests of the EVC facilitated efficient village management operations. Consequently, the robust economic performance of the EVC established a solid foundation for achieving communal prosperity. In the case of the LMMJ project, the collective efforts of the three villages led to an integrated EVC. The EVC aggregated and warehoused unused rural land and properties within the scenic area, streamlining operations and generating over 1 million RMB in property rental revenue.

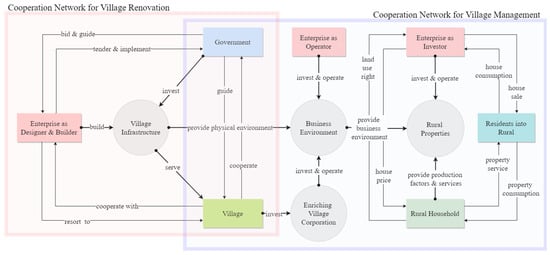

(4) Interest linkages. The formation of a densely interconnected network of interests in the rural village is a result of the intricate collaboration between the government-initiated cooperation networks of rural renovation and the operator-driven cooperation networks of rural management (see Figure 3). Firstly, the agriculture department drove the establishment and operation of EVCs to create business opportunities for idle laborers in villages through government projects, while also allowing villagers to benefit from governmental initiatives. Additionally, EVCs facilitated further development of village industries by extensively acquiring idle rural land and houses within villages. Secondly, the tourism department attracted village operators and promoted the establishment of joint ventures between village operators and villages to facilitate cooperation in rural industries. Village operators and villages must meet the necessary criteria for conducting village operations. Secondly, the tourism department attracted village operators and promoted the establishment of joint ventures between village operators and villages to facilitate cooperative operations in rural industries. Village operators and villages met specific criteria for engaging in village operations. Once both parties expressed their willingness to cooperate, they proceeded with the interest linkage under government supervision: (1) signing a joint venture agreement; (2) registering and operating the joint venture within the village; (3) allowing both parties to negotiate an exit strategy if necessary; (4) evaluating and compensating operators by the government after completion of events. The village operator assumed responsibility for managing the holistic business environment of the village while acting as a representative connecting all available resources with the EVC. In a word, the village management had established a comprehensive interest linkage mechanism in which enterprises contributed funds, villages provided resources, villagers contributed labor, and governments offered policies. In the case of the LMMJ project, the township of GaoHong, the village operator, and the EVC form a closely knit interest linkage, with village operator and EVC shares being distributed at a ratio of 90% to 10%.

Figure 3.

Interest Linkages of Village Management in Lin’an (since 2016).

4.4. Case Analysis: Tracing the Emergence of Linkages and Systemic Outcomes

In the initial phase (2003–2015), government-led village renovation established a foundational spatial and environmental framework. The subsequent phase (since 2016) has been defined by strategic village management, aimed at activating industrial revitalization through partnerships between urban enterprises and rural collectives. This deliberate shift catalyzed a profound transition in Lin’an, driving its evolution from a primarily production-oriented space toward a multifunctional countryside characterized by functional diversification. The dominance of traditional agriculture has receded, making way for recreational agriculture, premium residential development, tourism, and leisure—all reflecting a broadened spectrum of rural functions. Concurrently, Lin’an has been progressively integrated into extra-regional networks, transforming into a globalizing countryside. This transformation is propelled by the influx of capital, entrepreneurial talent, and consumption patterns from globalized urban centers like Shanghai and Hangzhou. These external flows have fundamentally reshaped the local spatial order, economic base, and social fabric, embedding the village within wider circuits of mobility and investment.

This co-evolution of multifunctionality and globalization is substantiated by tangible outcomes (see Table 1). From 2016 to 2022, twenty market-based operation teams were introduced into twenty villages. Their activities generated cumulative tourism revenue of approximately 490 million RMB, boosting collective village income by 89.3 million RMB and increasing villagers’ direct income by 21.69 million RMB (averaging 12,000 RMB per capita). By leveraging these operators for further investment promotion, Lin’an attracted 98 commercial projects with a total investment value of 340 million RMB. Furthermore, 3500 acres of idle residential land and 177 farmhouses were repurposed. These initiatives created around 1200 local jobs and successfully attracted over 800 young people to return to their hometowns for entrepreneurship, demonstrating the regenerative impact of this new developmental paradigm.

Table 1.

Results of Empirical Test.

The test of the causal mechanism is outlined below (see Table 1). (1) Government logic drives spatial restructuring. Government projects in the countryside have significantly improved the living environment and provided favorable external conditions for reutilizing idle rural resources. However, while the government excels at engineering construction for village renovation, it struggles with market operations for village management. This verifies H1.1. Performance-oriented projects in rural areas tend to become idle assets that do not meet the actual needs of the countryside. This verifies H1.2. In summary, government interventions in the countryside lead to rural spatial restructuring. Thus, H1 is supported.

(2) Enterprise logic drives economic restructuring. In the stage of village renovation, less capital flows into the countryside; in the stage of village management, capital is directed towards rural areas. This indicates that the integrated hardware and software construction policies implemented during the village management stage are effective. Village operators contribute to improving the overall business environment of villages, while industrial and commercial investments into rural areas contribute to increasing the economic income of rural households. This finding supports H2.1. However, a small number of enterprises infringe upon the interests of rural households. This observation confirms H2.2. In summary, capital inflow into the countryside results in rural economic restructuring. Therefore, H2 is validated.

(3) Village logic drives social restructuring. In the village renovation stage, the absence of an EVC serving as an intermediary forces urban enterprises to deal with scattered rural households, resulting in high transaction costs. When disputes arise, urban enterprises are prone to social exclusion, operational difficulties, and market withdrawal. This confirms H3.1. In the village management stage, an EVC collaborates with urban enterprises and acts as an intermediary to coordinate management conflicts, effectively reducing institutional costs for the enterprises. This verifies H3.2. In summary, village responses to capital from governments and enterprises lead to rural social restructuring. Consequently, H3 is supported.

(4) Interest linkage drives governance restructuring. In the village renovation stage, governments establish interest linkages with both villages and enterprises involved in project construction. Enterprises also form interest linkages with villagers during industrial operation. However, these two cooperative networks remain isolated from each other, hindering the effective resolution of potential disputes. This verifies H4.1. In the village management stage, the government-backed EVCs and village operators assume both internal and external management responsibilities, serving as crucial pivots that link the renovation and management collaboration networks. Despite potential conflicts among governments, enterprises, and villages, comprehensive and close cooperative networks help control these conflicts for sustainable village development. This finding supports H4.2. In summary, the interest linkages formed during village renovation and management result in rural governance restructuring. Thus, H4 is validated.

In sum, this study contributes to the literature on rural restructuring/transformation in China [3,18,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] by moving beyond the prevalent focus on static outcomes within distinct spatial, economic, and social dimensions. It explicates the dynamic co-evolutionary process between external interventions (e.g., state and market actors) and internal community responses. Specifically, the research identifies the critical role of the “village operator” as a pivotal institutional innovation. This entity functions as a key intermediary that effectively links external resources with endogenous assets, aligns divergent interests between outside investors and local villagers, and significantly reduces transaction costs. By doing so, it weaves the separate external intervention network and the internal response network into a cohesive, collaborative whole. Thus, the analysis provides a process-oriented framework that reveals how systemic transformation is co-produced through the mediation and integration of multi-scalar actor networks, advancing the mechanistic understanding of rural change in developing contexts.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications: Pathways to Resilient and Sustainable Rural Systems

This study concludes that the sustainable revitalization of rural systems, particularly within the spatially parallel and temporally compressed context of China, is fundamentally driven by the co-evolutionary interaction of multiple-agent logics within a Complex Adaptive System. The Lin’an case demonstrates that, in navigating the multiplex transition towards a multifunctional and globally influenced countryside, instrumental rationalities of government and enterprise can be synergized with the value rationality of villages through adaptive intermediary mechanisms. The “village operator” model, rooted in the collective economy, exemplifies an institutional innovation that reconfigured spatial, economic, and social subsystems by aligning diverse interests. This transition from a state-led project to collaborative co-production is central to enhancing systemic resilience and achieving sustainable rural revitalization.

The theoretical implications extend the findings to the broader phenomenon of rural transformation in developing countries. The analytical triad of multi-agent logics, adaptive intermediaries, and synergistic subsystem restructuring provides a transferable framework for understanding how rural systems can manage the concurrent pressures of multifunctional development (e.g., production, consumption, conservation) and global integration. It underscores that successful adaptation does not stem from homogenizing forces but from institutional arrangements that productively channel the interplay of global linkages, state steering, market forces, and embedded community agency.

The primary policy implication is to prioritize governance frameworks that institutionalize sustained multi-agent collaboration beyond initial infrastructure investment. For developing countries undergoing similar multiplex transitions, policies must formally integrate long-term management mechanisms with physical renovation plans. This involves incentivizing enterprises and local collectives as core operational partners and legally embedding mediators (e.g., village operators) to reduce transaction costs and align interests among state, market, and community actors. Such a shift—from singular government projects to platforms for ongoing co-production—is essential for transforming latent resources into enduring socio-ecological vitality, offering a replicable pathway for sustainable rural revitalization in an era of globalized change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X.; methodology, Z.X.; software, Z.X.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Z.X.; investigation, Z.X., Y.Z. and G.L.; resources, Z.X.; data curation, G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X., Y.Z. and G.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.X.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Z.X.; project administration, Z.X.; funding acquisition, Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC No. 42171254) and the Social Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. 22NDJC070YB, 22NDJC068YB).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions. Zhongguo Xu sincerely thanks Jianmei Luo, Ruikun Xu, Ruihao Xu and other family members for their firm support of his work over the years. This article is dedicated to Zhongguo Xu’s mother, Jinglian Dong, and his deceased father, Muxian Xu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cloke, P.; Marsden, T.; Mooney, P. Handbook of Rural Studies; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Progress of research on urban-rural transformation and rural development in China in the past decade and future prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y. Rural restructuring in China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Whatmore, S.; Munton, R. Uneven development and the restructuring process in British agriculture: A preliminary exploration. J. Rural Stud. 1987, 3, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J.; Lowe, P.; Ward, N. The Differentiated Countryside; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, H. Locality and rurality: The restructuring of rural social relations. Reg. Stud. 1986, 20, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. Trial by space for a ‘radical rural’: Introducing alternative localities, representations and lives. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggart, K.; Paniagua, A. What rural restructuring? J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbery, B.; Bowler, I. From agriculture a productivism to post-productivism. In The Geography of Rural Change; Ilbery, B., Ed.; Longman: London, UK, 1998; pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. The Living Land: Agriculture, Food and Community Regeneration in Rural Europe; Earth Scan: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, O.J. Rural restructuring and agriculture-rural economy linkages: A New Zealand study. J. Rural Stud. 1995, 11, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. Rural Futures: The Consumption Countryside and its Regulation. Sociol. Rural 1999, 39, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Precarious rural cosmopolitanism: Negotiating globalization, migration and diversity in Irish small towns. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Refugees, race and the limits of rural cosmopolitanism: Perspectives from Ireland and Wales. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, L. Multifunctional rural development in China: Pattern, process and mechanism. Habitat. Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Land Use Transitions and Rural Restructuring in China; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Keeble, D.; Peter, L.; Thompson, O. The urban- rural manufacturing shift in the European Community. Urban Stud. 1983, 20, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, M.; Lundholm, E. Restructuring of rural Sweden: Employment transition and out-migration of three cohorts born 1945–1980. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. Rural restructuring in the American West: Land use, family and class discourses. J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggart, K.; Paniagua, A. The restructuring of rural Spain? J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Goodwin, M.; Milbourne, P.; Thomas, C. Deprivation, poverty and marginalization in rural lifestyles in England and Wales. J. Rural Stud. 1995, 11, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Reid, C.; Collins, J. Rural cosmopolitism in Australia. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.; Nelson, P. The global rural: Gentrification and linked migration in the rural USA. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 35, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Woods, M.; Fois, F. Rural decline or restructuring? Implications for sustainability transitions in rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, L.; Long, H.; Woods, M.; Fois, F. Rural vitalization promoted by industrial transformation under globalization: The case of Tengtou village in China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Tan, K.C. Reform and the process of economic restructuring in rural China: A case study of Yuhang, Zhejiang. J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.; Xue, L.; Wang, M. Spatial restructuring through poverty alleviation resettlement in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Deng, C.; Wan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Fei, Z.; Li, H. Rural settlement restructuring based on analysis of the peasant household symbiotic system at village level: A Case Study of Fengsi Village in Chongqing, China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, Q.; Long, H. Spatial distribution characteristics and optimized reconstruction analysis of China’s rural settlements during the process of rapid urbanization. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Xie, H. Rural spatial restructuring in ecologically fragile mountainous areas of southern China: A case study of Changgang Town, Jiangxi Province. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, J.; Lei, Y. Villages at the urban fringe–the social dynamics of Xiaozhou. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Shi, K.; Niu, C. A comparison of the means and ends of rural construction land consolidation: Case studies of villagers’ attitudes and behaviours in Changchun City, Jilin province, China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yep, R.; Forrest, R. Elevating the peasants into high-rise apartments: The land bill system in Chongqing as a solution for land conflicts in China? J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Wu, F.; Deng, X. Understanding rural restructuring in China: The impact of changes in labor and capital productivity on domestic agricultural production and trade. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Wang, D.; Zheng, L. The impact of migration on agricultural restructuring: Evidence from Jiangxi Province in China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Liao, T.F. Labor out-migration and agricultural change in rural China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Han, Z.; Deng, X. Changes in productivity, efficiency and technology of China’s crop production under rural restructuring. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Zhai, L. Land abandonment under rural restructuring in China explained from a cost-benefit perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Gallent, N. Second homes, amenity-led change and consumption-driven rural restructuring: The case of Xingfu village, China. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Xie, X.; Lv, Z. Taobao practices, everyday life and emerging hybrid rurality in contemporary China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Fang, F.; Song, M. The influences of aging population and economic growth on Chinese rural poverty. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, D.; Xue, P. Factors influencing the efficiency of rural public goods investments in mountainous areas of China: Based on micro panel data from three periods. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Deng, Y.; Tang, Z.; Cao, R.; Chen, Z.; Jia, K. Adaptive capacity of mountainous rural communities under restructuring to geological disasters: The case of Yunnan Province. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ye, J. From a virtuous cycle of rural-urban education to urban-oriented rural basic education in China: An explanation of the failure of China’s rural school mapping adjustment policy. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gao, J.; Chen, J. Behavioral logics of local actors enrolled in the restructuring of rural China: A case study of Haoqiao Village in northern Jiangsu. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. Social Theory and Social Structure; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ai, Y. Institutional change under multiple logics: An analytical framework. Chin. Soc. Sci. 2010, 4, 132–150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, C.; Zhou, F. Capital into the countryside and village reconstruction. Chin. Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 100–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q. Capital into the countryside and restructuring of rural governance. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 18, 120–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. On “Promising Collectives” and “Managing villages”: The role of village governance and its practical mechanism under rural revitalization. Agric. Econ. Probl. 2019, 2, 24–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Beach, D.; Pedersen, R. Process-Tracing Methods: Foundation and Guidelines; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T. Rural geography trend report: The social and political bases of rural restructuring. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. Local Government in Transition: Official Incentives and Governance; Truth and Wisdom Press: Shanghai, China; Life Reading New knowledge Press: Shanghai, China; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Tan, M. Central and Local Governmental Relations in Contemporary China; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. The Institutional Logic of Governance in China: An Organizational Approach; Life Reading New Knowledge Press: Shanghai, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, F. Risk, Uncertainty, Profit; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. The Entrepreneur of the Firm: Contract Theory; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fei, H. From the Soil, the Foundation of Chinese Society; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P. The Peasant Economy and Social Change in North China; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Li, G.; Zhuo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Institutional logic of list management for idle rural residential land redevelopment. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 46–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Tu, S.; Ge, D.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.