Abstract

Firms globally are transforming digitally to enhance performance through building differentiated organizational capabilities within their digital ecosystem to maximize value. Drawing from the dynamic capability theory, this study aims to investigate the sources of sustainable competitive advantage, based on data from the UAE, by examining the impact of strategic orientations on firms’ survival through integrated strategic capabilities, adaptive marketing capability, and market ambidexterity. The choice of the UAE was based on two rational reasons. First, the adoption of new technologies is excelling in the UAE’s competitive environment especially AI, cloud, and data solutions across services industries, e.g., ICT, Telecom, Aviation, etc. Second, the government drives the digital economy to enhance the country’s positioning globally. Following a quantitative approach with a sample size of 185 service firms operating in the UAE, the study identifies how strategic orientations enable service firms’ long-term survival. Moreover, it assesses the moderating role of digital transformation between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage through integrated strategic capabilities. Thus, it provides a better understanding of the dynamic capabilities of firms transforming digitally. The study revealed that strategic orientations positively enable the development of integrated strategic capabilities. The latter mediate significantly between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage. It confirms that digital transformation is strengthening the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage through the integrated strategic capabilities. The study contributes to evolving new forms of integrated strategic capabilities as sources for sustainable competitive advantage. It confirms the adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity integration and thus enriches the dynamic capability theory and ambidexterity theory body of knowledge.

1. Introduction

In an era marked by relentless dynamism and rapid technological advancements, the realm of business confronts an unprecedented level of complexity. Companies are tasked with navigating a volatile landscape, where success hinges not only on traditional strategies but also on the ability to adapt swiftly, innovate continuously, and balance their exploration and exploitation initiatives [1], resulting in higher agility and creativity and gaining competitive advantage [2]. This necessitates a profound understanding and implementation of strategic orientations, adaptive marketing capabilities, and ambidexterity within organizational frameworks, especially where digital transformation investments mandate a high level of investment and collaboration with major players that are reflected in firms’ corporate strategies.

After 54 years of union, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has proven its competitiveness in a wide range of service sectors, including telecommunication (Telcom), information technology (IT), information communication technology (ICT), banking, hospitality, healthcare, and aviation. The government of the United Arab Emirates is taking several proactive steps to establish itself as one of the world’s most prominent and highly regarded nations driving higher AI adoption. This necessitates high levels of collaboration and strategic investments to realize this strategic priority.

The UAE government’s vision and strategies have evolved over time, starting with the e-Government initiative, hosting EXPO 2020, and developing an artificial intelligence (AI) strategy with the establishment of the Ministry of AI. The government also supports entrepreneurs and digital accelerators through collaborations and the collaborative spirit that is permeating the entire country. This is consistent with the country’s objective of using digitalization to maintain a sustained competitive advantage both locally and globally.

The digital economy (DE) is associated with the portion of economic activity that comes exclusively or mostly from digital technologies and has a business strategy centered around digital goods or services [3].

Global economic development and the rise in the digital economy are both products of technological advancement. According to a number of authors, the size of the global digital economy shows a rapid growth trend that has had a significant impact on productivity [4,5], innovation [6], and operational performance [7]. Hence, within the digital economy (DE), digital transformation (DT) is seen as a crucial strategic option for businesses to enhance sustainable development [8], optimize production through resource optimization, and foster sustainable innovation [9].

The global pandemic and EXPO 2020 event marked a turning point in the history of all enterprises, as they embarked on a digital transformation based on the principles of Industry 4.0. Several industries such as telecommunication, education, and digital enterprises have been completely transformed towards higher digital solutions adoption such as online learning and digital channels. The pandemic motivated enterprises and their partners to transform digitally by modifying or enhancing their business models and relationships throughout their entire supply chain in order to maintain service delivery to customers, and seize the opportunities presented by newly created demand through various exploration and exploitation activities. This demands the strong support of organizational strategic orientations and distinctive capabilities in order to remain viable in the market and survive in such a hostile environment where change is the only constant phenomenon.

The recent literature has shown a pressing need to investigate the sources of firms’ sustainable competitive advantages in relation to the dynamic capabilities theory (DCT) which suggests that to gain a competitive advantage firms should continuously sense, seize, and transform its resources [10] which is supported by the firm’s functional organizational capabilities like adaptive marketing capabilities and reflected in its ability to be alert to the market, foresee potential opportunities, flex its strategy, and adapt proactively to the market’s future development and thus outperform their rivals and minimize gaps between the company’s response and changes in the market [11]. Moreover, market ambidexterity is the ability of firms to explore and exploit existing and new markets simultaneously [12], and digital capabilities. These are becoming hot topics in the digital era with fast changing business environments where ecosystem integration is of top priority for the survival of service firms, such as in the ICT, IT, Telcom, logistics, and airline service industries. In today’s business discourse, the importance of strategic orientations in fostering organizational performance has been widely recognized [13,14]. According to the literature, firms that adopt a clear strategic orientation aligned with market dynamics tend to exhibit heightened resilience, agility, and long-term sustainability [11,15]. These strategic orientations encompass a spectrum of approaches, ranging from market-driven strategies that emphasize customer centricity to technology-focused strategies that leverage innovation for competitive advantage. Previous researchers argued that the adaptation of marketing capability to a firm’s external business environment is dependent on culture [16,17,18,19], which can influence the relationship between the adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity capability. A recent study call for researchers to investigate the impact of such factors on fostering this relationship [20] and another new study emphasize the need to have a broader understanding of how strategic orientations and innovation culture impact performance in diverse market contexts [14], such as the UAE.

Moreover, the impact of market ambidexterity on the competitive advantage of firms remains mostly unexplored, and one study found that paradoxical tensions between exploration and exploitation within the ambidexterity strategy erode the benefits of gaining a competitive advantage [21]. Wesiss and Kanbach (2022) [22] suggest further examining the interaction or combinatory relationship between inside-out and outside-in marketing capabilities to test their effect in better sustaining and balancing contextual ambidexterity. Our study also addresses the call of Akgun and Polat (2022) [12] to examine the impact of both cultural and behavioral methods on adaptive marketing capability to assess its nature and possible performance advantage with other marketing capabilities, such as market ambidexterity when the same is reinforced by adaptive leadership [23], as used in this research case.

Dynamic capability theory (DCT) focuses on a firm’s ability to adapt and respond to changes in the external environment. A major criticism of this theory is that it does not sufficiently consider the role of technology in developing and deploying dynamic capabilities (DC), and the DC framework for firms transforming digitally needs to be tested in different firms from different industries with varying digital maturity to enhance it [24].

The adoption of AI at scale in today’s business environment globally as part of the digital transformation (DT) enables higher competencies across organizations by enhancing the core or improving products and offerings. AI maturity and readiness notions connected to enterprises’ deployment of AI have garnered attention in recent studies [25]. To ensure value creation and realization, companies undergoing digital transformation (DT) are encouraged to evaluate or enhance their own AI maturity [26,27,28]. Using the readiness notion as a benchmark enables them to determine how project teams modify, reconfigure, and transform their core processes based on the degree of technological readiness [25]. This is consistent with another theme that organizes findings based on levels or phases using concepts of preparedness and maturity, such as Neumann et al. (2024) [29] and Zhang et al. (2021) [30]. These changes in the way of working and performance measurement-associated challenges and their overall impact necessitate focus.

Moreover, digital transformation (DT) has received limited attention from researchers from a strategic change point of view, and the integration of dynamic capabilities (DCs) into the same context needs further investigation [31,32]. Subsequently, a study in digital transformation [32] called for a quantitative research-based method to measure the impact of digital transformation on organizational business variables such as their survival, growth, and performance. Hence, the authors considered this need when conducting this research.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the impact of strategic orientations on firms’ sustainability during their digital transformation journey and to assess the mediation effect of dynamic capabilities (adaptive marketing and market ambidexterity). Hence, the following three questions are posed and answered in this study.

Research Questions:

RQ1: What is the impact of strategic orientations on firms’ sustainable competitive advantage?

Sub-Questions:

RQ2: What is the mediation impact of integrated strategic capabilities on firms’ sustainable competitive advantage?RQ3: What is the moderation–mediation effect of digital transformation in the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage through integrated strategic capabilities?

This research contributes to the strategic management literature in several ways. First, our findings add to a better understanding of the integration of adaptive marketing capability (AMC) and market ambidexterity (MA) as dynamic capabilities (DCs), while transforming digitally for differentiation and positioning in the market for long-term sustainability. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to examine firms’ sustainable competitive advantage in the coexistence of adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity. This relationship is uncovered with the moderation effect assessment of digital transformation in the service industry. Third, the research contributes towards showing the impact of strategic orientations (SOs) (proactive marketing orientation (PMO), responsive marketing orientation (RMO), and innovation orientation (IO)) on firms’ differentiation for a sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). Overall, the framework will enhance the literature and the understanding of the dynamic capabilities’ routines in digitally transformed firms.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides the theoretical framework through a literature review (theoretical foundation) with hypotheses and conceptual model development, Section 3 provides the research methodology, Section 4 presents the results and discussion, Section 5 presents the conclusion, Section 6 presents practical implications and Section 7 presents the limitations of the study and future research recommendations.

2. Theoretical Framework

The ability of firms to innovate, generate value, and develop sustainable competitive advantage and differentiated performance is crucial to their long-term survival in today’s disruptive, dynamic, and aggressively competitive digital business environment [33]. As a result, it receives great attention in the field of management research and executives’ agendas [34,35]. Firms to develop and gain sustainable competitive advantage mandate firms to be distinguished with imitable strategic capabilities such as adaptive marketing capability [19,22,36,37], strategic orientations [35], market ambidexterity [6,20,37,38,39], and digital capabilities resulting from their ongoing digital transformation [24,32,40,41,42,43].

Innovations as a differentiator in the digital ecosystem are highly valued by industries aiming for sustainable competitive advantage in such a hostile environment [20,37,44,45]. To achieve incremental and radical product innovations, researchers like Ganzaroliet et al. (2016) [46] suggested carrying out both exploration and exploitation operations concurrently [20,37,39].

Prior studies have highlighted the significance of organizational characteristics that improve firms’ capacity for adaptive marketing, allowing them to more effectively carry out both exploration and exploitation activities concurrently [12,16,19,20,47], and emphasized that a firm’s leadership strategic orientations must support the growth of dynamic capacities for high adaptability that reinforce a strategic orientation culture, values, and higher order routines in order to achieve ambidexterity.

According to this viewpoint, researchers have recently focused on strategic orientations including proactiveness, responsiveness, and inventiveness [12,35,37,48]. This helps achieve a better level of ambidexterity by coordinating efforts with the firms [16]. Hence, the integration between adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity is considered in this study and in response to the calls of Akgun and Polat (2022) [12] and Ali et al. (2022) [20] which thus becomes among the first to assess the relationship between SO’s and SCA in the presence of the integrated capabilities of AMC and MA. This adds to the dynamic capability theory and innovation body of knowledge.

According to Warner and Wager (2019) [32], Teece (2018) [47], Ellstrom et al. (2021) [24], Farzaneh et al. (2022) [37], and Schnider et al. (2023) [49], digital transformation is essential to business model innovation, which facilitates partnerships and alliances between companies in the digital ecosystem. Therefore, market experimentation (co-design), strategic alliances, and attentive learning are used to develop organizational learning and competencies. As a result, the companies’ internal operational procedures, operating models, product automation (incremental innovation), and, ultimately, radical innovation, offering new, cutting-edge digital products like digital internet, omni-channels, etc., are completely reshaped.

In order to balance the exploration and exploitation of all digital opportunities and enable a positive business case for digital transformation initiatives, it is imperative to develop adaptive marketing capabilities supported by strategic orientations. This is because digital transformation requires enormous amounts of capital resources and organizational efforts (both internally and externally) [49]. The amount of research on digital transformation is growing daily, but its comprehensive understanding of integrated strategic capabilities (adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity) is lacking [49], particularly with regard to its effects on product innovation because this field is fragmented and understudied both theoretically and empirically. As a result, our study is one of the first to identify the moderating effect of digital transformation on these capabilities.

This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on strategic orientations, strategic integrated capabilities (adaptive and ambidextrous), digital transformation, and sustainable competitive advantage in the service enterprises. This study argues that strategically oriented firms can withstand, in the long run, the competitive pressure of market dynamics, which are constantly changing, due to their distinctive marketing capabilities, which converge together due to their dynamic nature, and by developing digital capabilities and transforming their strategies and business models effectively in the digital ecosystem. Therefore, strategically oriented firms that are adaptive and ambidextrous can achieve a sustainable competitive advantage as a result of these dynamic capabilities. Hence, they are differentiated by their digital capabilities embedded in their products and services, which make it difficult for competition to imitate.

2.1. Dynamic Capability Theory as a Foundation

Research on sustainable competitive advantage has followed a number of approaches and views over time. The competitive advantage is an outcome across these approaches and capabilities [36,37,50]. The dynamic capability (DC), the adaptive marketing capability theory (AMC), and market ambidexterity (MA) are all enabled by strategic orientations (SOs). Although competitive advantage focuses on how businesses are positioned within their industry, recent research highlights that advantage in dynamic contexts necessitates flexibility and ongoing innovation [51].

Due to its nature of resources renewal continual approach, this study selected the dynamic capability theory (DCT) as a conceptual foundation to offer a theoretical insight, showing the interactions between strategic orientations and converged integrated strategic capabilities, in particular, adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity, digital transformation, and sustainable competitive advantage. DCT is selected as it provides one of the strongest theoretical lenses on how companies can develop/renew their resources to overcome the fast changes in today’s hostile technological environment [10].

The dynamic capability framework implies that firms can attain competitive advantage in a volatile business environment by sensing, seizing, and transforming or reconfiguring their business models [10]. This enables firms to build strategic competencies that are necessary to respond to customer needs by providing innovative products and solutions, enhance their agility in seizing business opportunities before competition, and become able to develop the right strategies to transform in such a way that they can adapt to digital ecosystems with new business models and to the constant change taking place on a continuous basis so that they remain viable [37,47,52]. Teece’s (2018) study [47] highlighted the need for research that advances our knowledge of business model innovation, implementation, and change which could provide light on crucial aspects of dynamic capabilities. Later, Farzaneh et al.’s 2022 [37] study results suggest that intellectual capital is positively associated with innovation ambidexterity through dynamic capabilities enabling firms with capabilities to recognize environmental trends and create business models that tackle emerging risks and opportunities.

These serve as the foundation for dynamic capabilities. In their recent study, Pitelis et al. (2024) [52] emphasized that in the long run, dynamic capabilities can improve firm performance by co-creating value, exploring and seizing possibilities, and continuously rebuilding structures, procedures, and business models. They indicated a clear present opportunity for further research on the same.

Strategic marketing capabilities, including adaptive marketing capability [36] and market ambidexterity [53], are types of dynamic capabilities which play a vital role in firms’ long-term survival through their impact on innovations using a collaborative mindset, vigilant learning, and adaptive experimentations.

In an interesting recent study, Wijayanti et al. (2024) [54] concluded that there is a lack of research on integrating environmental considerations into marketing strategies for sustainable development and that more rigorous empirical studies are needed to establish causal relationships between dynamic managerial capabilities which are a form of dynamic capabilities and firm performance outcomes. They indicated a need for interdisciplinary research combining insights from marketing, strategic management, and organizational psychology for better understanding of the nature of managerial dynamic capabilities of organization.

Moreover, firms focusing on their culture is pivotal to be dynamic and innovative. Their strategic orientations are reflected in their proactiveness, responsiveness, and innovation orientations. These organizational competencies are also dynamic in nature [14]; outside-in and inside-out dynamic capabilities enable greater agility in terms of faster time to market with new innovative digital products fulfilling the evolving digital business needs and capturing higher value in the digital ecosystem [37,55].

Most importantly, firms’ ability to deploy resources for the execution of research and development (R&D) and market diffusion initiatives, as well as its strategic orientation, are key components of its marketing capabilities [56,57] which are essential for successful digital transformation. In the digital era and with the scale-up of digital technologies, it is also critical to emphasize the important role of digital transformation and its effect on improving the core business, building digital capabilities, and transforming towards new digital business models [25,47,58]. These capabilities, whether internal or external, enable higher efficiency, cost efficiency, digital product innovation, digital processes and platforms, digital experience, new revenue streams through alliances, and the establishment of new business models [24]. Digital capabilities, such as platform ecosystems, artificial intelligence, and data analytics, improve the company’s capacity to recognize opportunities, react to risks, and boost operational effectiveness [59]. Based on the above, this study considers and studies these integrated strategic capabilities relationships and their impact on firms’ sustainability, taking into account strategic orientations as a dependent factor while transforming digitally, and we hypothesize accordingly considering a quantitative approach applied in the service industry similar to others like Ali et al. (2022) [20] following the deductive approach in the manufacturing industry.

2.2. Strategic Orientations and Sustainable Competitive Advantage

In order to preserve sustainable competitive advantage, researchers recommend enhancing industry positioning with internal resource development and ongoing adaptation [59]. This is linked to the firm’s strategic orientations that a firm undertakes to achieve its objectives. Strategic orientations entail a firm’s philosophy about its orientation towards its environment [60] and is becoming very critical in today’s digital environment, enabling the handling of complexity in the digital ecosystem and maintaining competitiveness in the marketplace. The first orientation is proactiveness, which supports firms in their long-term planning, in which future trends and new technologies ensure readiness to maximize value [61,62]. The other critical organizational orientation is responsiveness, which enables quick responses to the rapidly changing needs of customers [63], digital product demand, and fostering improved customer loyalties and experience by meeting these rising expectations in real time. Innovation orientations are becoming even more crucial in product innovation, creativity, and the adoption of new technologies such as AI, cloud, data analytics, and security solutions, and this also boosts new innovative product launches, process efficiency improvements [64], the scaling-up of agile methodologies, and more. Sustainable competitive advantage, on the other hand, pertains to a firm’s long-term ability to outperform its competitors in terms of the customer value delivered [65]. In recent years, numerous studies have explored the relationship between these two concepts. For instance, Ed-Dafali et al. (2023) [35] and Morgan et al. (2009) [66] established strategic orientations such as market orientation, innovation orientation, and entrepreneurial orientation, which contribute to a firm’s sustainable competitive advantage. They argued that such orientations enable firms to better understand and respond to market needs, foster creativity and innovation, and encourage risk-taking behavior, all of which can lead to a sustainable competitive advantage. Ed-Dafali et al. (2023) [35] call for future studies to consider other factors which may predict sustainable competitive advantage in today’s technological revolution era. Moreover, a study by Hult et al. (2003) [67] also highlighted the significance of learning orientation in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. They argued that a learning-oriented firm is better positioned to adapt to environmental changes and thus maintain its competitive advantage in the long run. This is complemented by another study showing that strategic orientations have a significant impact on sustainable performance [68,69,70,71].

From a resources and competencies point of view, both Barney (1997) [72] and Teece et al. (1997) [10] reflected clearly the role of firms’ orientations as intangible distinctive competencies that are difficult to imitate by competitors [73], giving firms a competitive advantage, radical product innovation [74], and higher performance [75]. This is in alignment with the earlier proposition by Narver and Slater (1990) [13], who indicated that strategic orientations create capabilities that distinguish firms and enable long-term sustainability. Thus, we conclude from the literature that strategic orientations play a crucial role in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. They provide firms with the ability to understand and adapt to market needs, foster innovation, and promote risk-taking behavior, which are essential for outperforming competitors in the long run. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Strategic orientations are positively related to firms’ sustainable competitive advantage (SO’s → SCA).

2.3. Strategic Orientations and Integrated Strategic Capabilities

Market ambidexterity is seen as a vital capability for managing the paradox between exploration and exploitation, which are strategic capabilities that an organization can adopt. Strategic orientations are an organization’s strategic direction and decision-making approach, which can be classified into two types: exploitative and exploratory [76,77]. Responsiveness focuses on refining, extending, and leveraging existing competencies to improve efficiency and control, whereas proactiveness involves searching, variation, risk-taking, experimentation, and discovery to innovate and adapt to changes. Recent studies have noted that the relationship between strategic orientations and market ambidexterity is positive and significant [78]. Organizations that adopt both responsive and proactive strategic orientations are more likely to attain market ambidexterity especially when ambidexterity thinking culture is disseminated within the firms’ DNA [79]. This balance allows organizations to not only refine and leverage their current competencies but also to innovate and adapt to changes, thereby achieving a sustainable competitive advantage [80]. However, it is also important to note that maintaining a balance between exploitative and exploratory activities is challenging due to their conflicting demands on resources and capabilities [81]. Hence, the role of leadership is crucial in managing this tension and achieving market ambidexterity [82]. The integration of exploration and exploitation was demonstrated to be strengthened by adaptive and paradoxical leadership styles, which highlighted the critical importance of leadership who manage conflicting demands and encourage creativity and innovation inside their teams and organizations [23,83].

By combining market ambidexterity’s focus on exploring new opportunities with adaptive marketing capability’s responsiveness to market changes, firms create a dynamic advantage. They stay ahead by proactively shaping market trends rather than merely reacting to them, enhancing their overall competitiveness especially in certain conditions where technology changes constantly [84]. Hence, we propose the second hypothesis, as follows:

H2.

Strategic orientations are positively related to integrated strategic capabilities (SO’s → ISC).

2.4. Integrated Strategic Capabilities and Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Marketing is the process of developing, conveying, delivering, and exchanging offerings that are valuable to consumers, clients, partners, and society at large [85]. In order to prioritize customer satisfaction, successfully address customer demands, and cultivate strong customer relationships, all of which contribute to increased profitability and a sustained competitive advantage, firms need dynamic managerial capabilities in marketing [85,86]. These capabilities are essential to enable sensing opportunities, seizing them, and driving strategic transformation for higher organizational agility which is vital for achieving competitive advantage against rivals [87].

Previous investigations conducted by Day (2011) [16], Mu (2015) [18], Mu et al. (2018) [19], and Al Jabri and Lahrech (2025) [48] implied that a company’s capacity to adjust to its external business environment relies on its culture, potentially impacting the connection between this capability and market ambidexterity. All these authors investigated the impact of adaptive capabilities on market ambidexterity. Day’s (2011) [16] great study reflecting the needs for marketing adaptive capabilities concludes that only companies with more adaptable business models, vigilant leadership, and resilience will be able to reap the rewards of these adaptive capabilities. This was followed by Mu’s (2015) [18] research where his study concluded that as long as the company matches organizational structure variables with the need for marketing capability for exploitation and exploration in product innovation, marketing capability is crucial for the company to adjust to external changes. The study was followed by another interesting finding by Mu et al. (2018) [19] where the study concluded that the interaction between the marketing organization elements of capabilities and human capital shows that both of these elements work together to achieve superior firm performance. Finally, Al Jabri and Lahrech’s (2025) [48] study showed that the association between adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity is found to be favorably mediated by strategic orientations, which are defined by a culture of proactiveness, responsiveness, and innovation.

Ali et al. (2022) [20] encourage future researchers to explore how this aspect influences the development of this relationship. Recent studies emphasize the significance of harmonizing a firm’s strategic outlook and culture with its marketing abilities. A proactive market orientation and a culture fostering innovation and risk-taking positively impact a firm’s adaptive marketing capability, enabling swift and effective responses to market changes. Similarly, a responsive market orientation and a culture emphasizing customer focus and collaboration positively affect a firm’s market ambidexterity, allowing the simultaneous pursuit of exploratory and exploitative activities, such as developing new products while optimizing existing ones [12]. For instance, Morgan et al. (2009) [66] observed that companies with a market orientation and robust marketing capabilities surpassed those lacking such strengths. On the other hand, a recent study conducted by Ardabili et al. (2025) [88] showed that firms with high ambidexterity maturity are able to sustain their business in today’s volatile market. Correspondingly, Akgun and Polat (2022) [12] noted that firms with adaptive marketing capabilities were more adept at innovation and accomplishing strategic objectives. Collectively, the literature implies that a firm’s strategic outlook and culture significantly shape its marketing capabilities, encompassing adaptive marketing prowess and market ambidexterity. Al Jabri and Lahrech (2025) [48] illustrated this intersect in their recent study. Consequently, managers should carefully align these elements when formulating marketing strategies and fostering organizational cultures to develop ambidexterity capability. Day and Schoemaker (2016) [89] studied the significance of adaptive marketing capabilities and argued that firms operating in rapidly changing environments must develop adaptive capabilities to effectively compete and succeed. This is complemented by Ansari et al. (2008) [90], who emphasized the importance of understanding consumer behavior and preferences in adapting marketing strategies across various marketing channels to meet evolving customer needs and preferences. In addition, Rukani and Ratnasari (2024) [91] demonstrate how employees’ collaborative innovation and dynamic innovation capability affect digital transformation and bank employee performance. Many scholars argue that firms need to concurrently prioritize exploitative and explorative innovations to gain and sustain a competitive advantage in present and future markets [1,19,20,48]. Exploitative innovations involve incremental changes to products, services, and processes based on current customer needs, aiming at enhancing existing services’ efficiency with lower novelty, risk, and investment [20,45]. In contrast, exploratory innovations are revolutionary and demand extensive market research and sensing capabilities to uncover new opportunities, aiming for the significant transformation of existing processes and offerings to meet emerging customer demands [92]. MA encapsulates two crucial attributes, alignment and adaptability, both aimed at altering business processes to cater to current and future customer needs, preferences, and demands [20,93]. Thus, firms’ effectiveness and adaptability in both operational and strategic marketing efforts are achieved, enabling them to function well in both stable and quickly changing situations. Hence, we propose a third hypothesis, as follows:

H3.

Integrated strategic capabilities are positively related to achieving firms’ sustainable competitive advantage (ISC → SCA).

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Integrated Strategic Capabilities

Strategic orientations facilitate the development of strategic marketing capabilities, allowing companies to understand and meet customer needs in both new and established markets. This empowers firms to provide exceptional customer value and swiftly respond to competitors within the market, as highlighted by Khedhaouria et al. (2020) [62]. Narver and Slater (1990) [13] emphasize that a deeper comprehension of customer needs, market trends, and competitive actions places market-oriented firms in a superior position to create essential capabilities crucial for long-term competitive advantage. Market-oriented firms prioritize knowledge acquisition to fulfil current needs by leveraging established competencies and products, emphasizing exploitation within the market [64]. Such firms tend to emphasize exploitative innovations, necessitating adaptability to evolving market trends through a robust learning capability. Furthermore, strategic orientations compel firms to consistently observe the external environment, assess industry competition, and compare their offerings with those of key competitors [45]. Adaptive marketing capability encompasses utilizing technology, data analytics, and consumer insights to customize marketing strategies efficiently. Scholars in the strategic marketing realm emphasize the necessity for companies to adopt flexibility and responsiveness to stay competitive in swiftly changing markets. Moreover, active learning, adaptable experimentation, and an open approach to marketing stand as essential catalysts for cultivating adaptive marketing capabilities within firms [20]. Consequently, a continual focus on strategic orientations enhances a firm’s marketing capabilities, making them more unique, ultimately leading to a sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). Therefore, the relationship between market orientation and the success of innovative products is mediated by innovative marketing competence [94].

The existing literature supported by Ali et al. (2022) [20], Ed-Dafali et al. (2023) [35], Morgan et al. (2009) [66], Cake et al. (2020) [74], and Hassen and Singh (2020) [75], aligns strategic orientations, adaptive marketing capability, and market ambidexterity as sources of sustainable competitive advantage, a significant driver of firm performance, profitability, success in launching new products, and achieving radical innovation for longer sustainability in the marketplace. To elaborate further, Ali et al.’s (2022) [20] study confirmed that adaptive marketing capability is influential to both incremental and radical product innovations for the ultimate performance of the firm. Recently, Ed-Dafali et al.’s (2023) [35] study on the role of Industry 4.0 readiness revealed that entrepreneurial orientation has a greater effect on firms’ sustainability in the marketplace. The results of Morgan et al.’s (2009) [66] study also show that marketing capabilities and market orientation are complementary characteristics that enhance company performance. Additionally, they discover that marketing capabilities have a direct impact on both ROA and perceived firm performance, and that market orientation directly affects businesses’ return on assets (ROA). Cake et al.’s (2020) [74] study demonstrated that learning and marketing orientations are important and critical factors for achieving radical innovation launch marketing capabilities. Hassen and Singh’s (2020) [75] findings of their study showed that the performance of small- and medium-sized businesses is strongly and favorably impacted by the customer orientation and inter-functional cooperation aspects of market orientation.

Researchers have discovered that by combining knowledge and utilizing cross-functional processes to produce and deliver higher customer value, dynamic marketing skills enhance corporate sustainability. The integration of many aspects of market information results in competitive advantage, and the breadth and depth of such knowledge enhance marketing dynamic capabilities. It is achieved by the efficient use of dynamic capabilities, continuous human resource learning and development, and robust market performance, all of which demonstrate a company’s ability to outperform its primary rivals [95].

Hence, we propose the fourth hypothesis, as follows:

H4.

Integrated strategic capabilities (adaptive market capability and market ambidexterity) positively mediate the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage (SO’s → ISC → SCA).

2.6. The Moderating Role of Digital Transformation

The digital transformation journey results in the implementation of new digital technologies as transformation assets that facilitate extensive organizational change by creating matching organizational capabilities [96]. This is aligned with Davies et al. (2023) [97] demonstrating a clear relationship between digital capabilities and service capabilities when assessing the impact of digital capabilities and transformation on marketing capabilities, sericitization, and the associated performance. Additionally, another study showed that incremental innovation and radical innovation significantly correlated with technological capabilities [98].

Based on a recent study, firms are struggling and face difficulty to successfully connect exploration and exploitation, and hence ambidexterity must be controlled at several organizational levels [99]. This study highlighted that IT-driven advances like big data analytics are improving customer knowledge and enabling ambidextrous marketing techniques, and digital technology has emerged as a potent enabler in addressing these conflicts [100].

Moreover, Teece (2018) [47], Matarazzo et al. (2021) [101], and Martins (2023) [102] highlight the significance of harmonizing digital transformation with a company’s value proposition and utilizing dynamic capabilities to address the changes and possibilities introduced by digital technologies. Teece (2018) [47] emphasized the need to concentrate on more crucial tasks like digitizing an already-existing company or developing new digital business models. Later on, Matarazzo et al.’s (2021) [101] findings demonstrate how digital tools help the chosen SMEs innovate their business models by opening up new routes of distribution and ways to produce and provide value to various consumer segments. The findings also demonstrate how important sensing and learning capacities are as catalysts for digital transformation. Recently, Martins’ (2023) [102] study showed that the relationship between the three dynamic capabilities and small and medium enterprise (SME) success is further enhanced by digitalization.

Additionally, Zhu et al. (2021) [103] suggest that DT can enhance AMC by equipping companies with tools to gather, analyze, and utilize real-time customer data. Hence, a data-driven culture in businesses has been a major factor in the recent emergence of data as the primary motivator and prerequisite for information systems-driven change. Aligning with this, Matarazzo et al. (2021) [101] assert that DT empowers SMEs to generate customer value through the creation of new products and services aligned with evolving customer needs. According to experts, the majority of businesses are not yet implementing AI at advanced technological maturity levels. Large IT consulting firms have noted that most clients’ work usually ends with well-developed and realized prototypes rather than fully functional solutions. There is a “valley of death” where many projects fail to go past the prototype stage, according to one expert, who estimated that only 10% of artificial intelligence ventures make it to the development of a live functioning system [25]. In their study, they concluded that while disruptive technologies that promote wider societal change require more sophisticated levels of governance and control, artificial intelligence systems targeted at enhancing current processes can be developed internally by enterprises and establish digital capabilities. Numerous research endeavors have delved into the correlation among these three principles. For instance, Zhu et al. (2021) [103] undertook a comprehensive examination of digital transformation and concluded that firms boasting robust adaptive marketing capabilities tend to exhibit a greater likelihood of possessing market ambidexterity capabilities. Gurbaxani and Dunkle (2019) [104] investigated how digital transformation correlates with favorable business results, revealing that organizations effectively implementing digital transformation initiatives typically display more robust adaptive marketing skills and demonstrate greater market ambidexterity capabilities. Moreover, Saeedikiya et al. (2024) [58] in their recent study on digital transformation’s role in developing dynamic capabilities concluded that it yields organizations to be more adaptive and responsive to constant changes in the market, strengthening a competitive advantage where stakeholders’ engagement in business processes is becoming critical and a beneficial factor to exploit the AI applications during the process of digital transformation [25]. Additionally, data-driven cultures and IT capabilities greatly boost ambidextrous creativity [4]. This confirms that digital transformation is a strategic initiative and a key enabler of building ambidextrous capabilities in today’s turbulent hostile environment [79]. Hence, we propose our fifth hypothesis, as follows:

H5.

Digital transformation positively moderates (strengthens) the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage in the presence of both adaptive marketing capability and market ambidexterity (DT x SO’s → ISC → SCA).

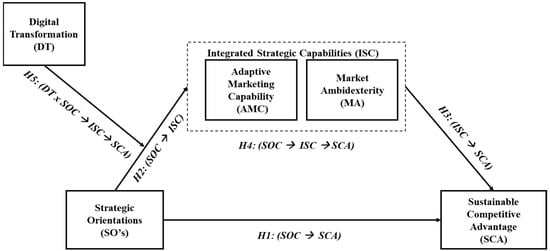

The following conceptual model (Figure 1) is developed based on the existing theories and the above hypothesis (H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5). It enhances the existing models by highlighting the mediating role of integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs) and the moderating role of digital transformation as a basis for this research.

Figure 1.

Research conceptual model.

Using dynamic capability theory (DCT) as a foundation, this study aims to examine the sources of sustainable competitive advantage using data from the United Arab Emirates, a highly digital economy focused by assessing the impact of strategic orientations on firms’ sustainability in the presence of integrated strategic capabilities and the moderation effect of digital transformation. The study contributes to enhancing the dynamic capability and innovation body of knowledge by uncovering the impact of integrated strategic capabilities during the digital transformation journey of organizations.

3. Methodology

In alignment with previous studies’ methods in the same field [12,18,19,20], the method used in this study is a quantitative deductive method carried out in the UAE service companies across the entire country. These firms are adapting new technologies and providing critical services to the UAE’s customers. The firms cover the information communication technologies (ICT), telecommunication (Telcom), information technology (IT), aviation, hotels, logistics, healthcare, and other industries. The selected firms are well established in the country and play major roles in providing advanced services. The selected sectors are major players in the digital economy and highly competitive. As they operate in the country for longer periods and are able to sustain in today’s aggressive competition, their strategic orientations’ raising need motivates this study where it aims to uncover the sources of sustainable competitive advantage. The need for innovation and new technology adoption such as AI, cloud, and data solutions is high and justify their selection for our study.

Following a convenience sampling design, a seven-Likert-scale survey was distributed online (Refer to Appendix A for the survey questions) targeting the senior management of 1200 service companies. With an almost 20% response rate, 224 responses were obtained with an unbalanced gender distribution of 184 males and 40 females. To assure higher data accuracy following Fornell and Larcker in 1981 [105] and Anderson and Gerbing in 1988 [106], 39 speeders were identified and removed for quality assurance, and hence 185 responses were retained.

The study constructs were adopted with multi-item measures which were validated from the existing literature. Based on the literature and the elaborated theoretical framework in Section 2 above, strategic orientations construct (SO’s) is the independent variable in this study. It consists of three dimensions (proactive market orientation (PMO), responsive market orientation (RMO), and innovation orientation (IO)) as defined in the literature [63] and is measured in this study using the 18 items adopted by Akgun and Polat (2022) [12], which were originally adopted from Narver et al. (2004) [107], e.g., “we constantly monitor our level of commitment and orientation to serving customer needs”. Sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) is the dependent variable; it is measured in this study using the 13 items originally adopted by Weerawardena (2003) [108], e.g., “our competitors find it difficult to keep up with our ease of learning from market changes”. The adaptive marketing capability (AMC) construct is the first mediating variable in this study. It consists of three dimensions (vigilant market learning (VML), adaptive marketing experimentation (AME), and open marketing (OM)) as defined in the literature (Day 2011) [16] and is measured in this study using 12 items adopted from Ali et al. (2022) [20] and Guo et al. (2018) [11,20], e.g., “our firm actively collects extensive marketing information through all social networks and media”. Market ambidexterity (MA) is the second mediating variable in this study. It consists of two dimensions (market exploration (MER) and market exploitation (MET)) as defined in the literature [38] and is measured in this study using 9 items adopted from Ali et al. (2022) [20] and Kim and Atuahene-Gimas (2010) [20,109], e.g., “Our firm used market information that takes us beyond current product market experiences through market experiments”. Digital transformation (DT) is the moderating variable in this study. It consists of five dimensions (digital strategy (DS), digital culture (DTC), digital process (DP), digital technologies (DTs), and digital business models (DBMs)) as defined in the literature [110] and is measured in this study using the 25 items adopted by Marx et al. (2021) [110], which were originally adopted from Valdez-de-Leon (2016) [111], e.g., “Collaboration with other ecosystem partners regarding the use of new technologies and digital transformation is well established in our organization”. The constructs’ role is listed below as a summary:

- Strategic orientations (SO’s): Independent variable;

- Sustainable competitive advantage (SCA): Dependent variable;

- Adaptive marketing capability (AMC): First mediator;

- Market ambidexterity (MA): Second mediator;

- Digital transformation: Moderator.

The study’s constructs, dimensions, and items are enclosed in Appendix A with all codes. The study started by developing an online survey using seven-point Likert scales, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7) to collect data adopting a convivence sampling method. As we assessed dynamic capabilities constructs, the survey was distributed to the senior management of 1200 service companies as a target respondent. A total of 224 responses were obtained; 39 speeders were identified which were excluded from the final analysis to assure higher data accuracy following Fornell and Larcker (1981) [105] and Anderson and Gerbing (1988) [106]. The response rate, calculated from the received surveys after a cleansing exercise, stood at 15.4% (Sample (n)= 185 out of 1200). In terms of the gender distribution among respondents, 82.14% were male (n = 183) and 18.86% were female (n = 40). To summarize, the steps are as follows:

- Step 1: Online survey developed using seven-point Likert scale;

- Step 2: Convivence sampling method was adopted as random sampling was found difficult to be performed practically;

- Step 3: Online survey distributed to respondents;

- Step 4: Responses were cleaned up from speeders for higher data accuracy;

- Step 5: Data analysis was carried out.

Study demographics and sample characteristics are described as follows. The bulk of participants (88.84%) held positions in middle management and higher, with 75% boasting a decade or more of experience within their respective firms. Moreover, the majority (96.43%) possessed at least a bachelor’s degree. The survey also showcased a diverse representation across industries: 16.96% from the ICT service sector, 35.71% from telecommunication services, 10.71% from IT services, and 36.62% from other sectors such as media, banking, hotels, aviation, and logistics. Notably, 67.86% of these companies had been operating in the UAE for over 20 years.

SPSS Version 26 was utilized to assess the measurement properties in this study due to its compatibility with a sample size of 185 and the complexity of the predictive model, as highlighted by Hair et al. (2011) [112]. Specifically, the Hayes method is a regression-based analytical approach that uses bootstrapping and was employed to examine the research model hypotheses, particularly those concerning indirect and conditional indirect effects.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted for each of the variables under investigation after successfully examining the outliers, multicollinearity, and normality checks. EFA was performed using a principal component analysis and Varimax rotation. The factor loading minimum threshold was set at 0.50. The sample size was assessed using Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO). Hence, factor analysis was carried out and proceeded with structural equation modeling analysis using Hayes as indicated above.

To ascertain the reliability of estimates, nonparametric bootstrapping, as proposed by Efron and Tibshirani (1994) [113], was used to derive standard errors. Evaluation of the models involved analyzing path coefficient t-values, obtaining 95% confidence intervals of bootstrap results for conditional effects, following Hayes (2013) [114], and assessing the explanatory strength of the models. This comprehensive approach provided a robust analysis of the research hypotheses and their effects within the examined model. Finally, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using SPSS Version 26 to statistically test whether the observed variables reliably measured their hypothesized latent constructs by assessing the model fit, factor loadings, and construct validity. The results were examined based on the acceptable thresholds as detailed in Section 4 below.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Validity and Reliability

In order to assess the validity and reliability, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed. The EFA scores and measure scores are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Items loading.

This study’s findings are presented Table 1 and Table 2, highlighting the outcomes from both Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability analyses. The Cronbach’s Alpha values ranged from 0.811 to 0.911, indicating a fairly high level of consistency. Similarly, the composite reliability statistics fell between 0.731 and 0.911, demonstrating a similarly high level of reliability. These values surpass the critical threshold of 0.70, a benchmark established by Hair et al. (2011) [112]. This is a significant milestone in research because it confirms that the measures used in this study are trustworthy and robust. It means that the tools chosen consistently and accurately capture those constructs, enhancing the reliability of the study’s findings.

Table 2.

EFA summary.

4.2. Multicollinearity Assessments

As indicated by Hair et al. (2016) [115], a VIF value below 5 is commonly regarded as acceptable, signifying that multicollinearity does not significantly impede the analysis. Table 2 provides specific VIF values corresponding to each indicator employed in this study. Notably, the table illustrates that VIF values for all indicators are below the recommended threshold. This observation implies that the indicators utilized in this study do not manifest problematic levels of multicollinearity, thereby ensuring the credibility and consistency of the statistical analysis undertaken. Table 3 indicates the VIF per item.

Table 3.

VIF statistics.

4.3. Convergent Validity

In this study, the assessment of convergent validity using average value extracted (AVE) statistics reveals that all constructs either meet or surpass the 0.50 threshold, except for SO’s, whose AVE is 0.403. Furthermore, composite reliability values above 0.70 further bolster the convergence of items within each construct. This finding suggests that convergent validity is not a concern in this study. Specific AVE values for each construct are outlined in Table 1 above, showcasing the convergence of measurements and confirming the reliability of the chosen indicators in accurately and consistently capturing the targeted constructs.

It should be noted that, as shown in Table 1 above, though the SO’s AVE value is 0.403, this is acceptable due to condition that “if AVE value is less than 0.5, but composite reliability is higher than 0.6, the convergent validity of the construct is acceptable” [105]. As illustrated in Table 1, all CR values are above 0.7; thus, the convergent validity is established accordingly.

4.4. Discriminant Validity

As per Fornell and Larcker’s framework (1981) [105], a crucial aspect in establishing discriminant validity involves comparing a construct’s square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with its correlations to other constructs. In this study, an in-depth examination was carried out by comparing the AVE square root for each construct with its correlations to other constructs, a comparison detailed in Table 2 above. The objective was to verify if each construct’s AVE square root surpassed its correlations with other constructs, a critical criterion in demonstrating discriminant validity.

The findings presented in Table 4 (Fornell and Larcker Criterion) indicate that, indeed, the AVE square root for each construct exceeded its correlations with other constructs. This discovery holds significant weight as it solidifies the demonstration of discriminant validity within the study.

Table 4.

Discernment validity—Fornell and Larcker Criterion.

Furthermore, the calculated Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT), which is 0.563 in Table 5, remained below 0.85 [116]. In summary, both assessments substantiate the discriminant validity of our measurement model.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio analysis.

To evaluate the discriminant validity, the average of cross-construct correlations (ACCC) was analyzed; a lower ACCC value indicates that each construct has stronger connections with its own indicators than with other constructs in the model. Convergent validity was evaluated using the Cor-average of within-construct loadings (AWCL), where greater AWCL values show that indicators are consistently and strongly correlated with their underlying construct. As an overall validity diagnostic, the computed ratio of ACCC to AWCL (ACCC/AWCL) was utilized; ratios significantly below unity show sufficient discriminant validity in relation to convergent validity within the study. Finally, the HTMT ratio remains below the threshold demonstrating the discriminant validity achieved.

4.5. Confirmatory Analysis

Measurement Model

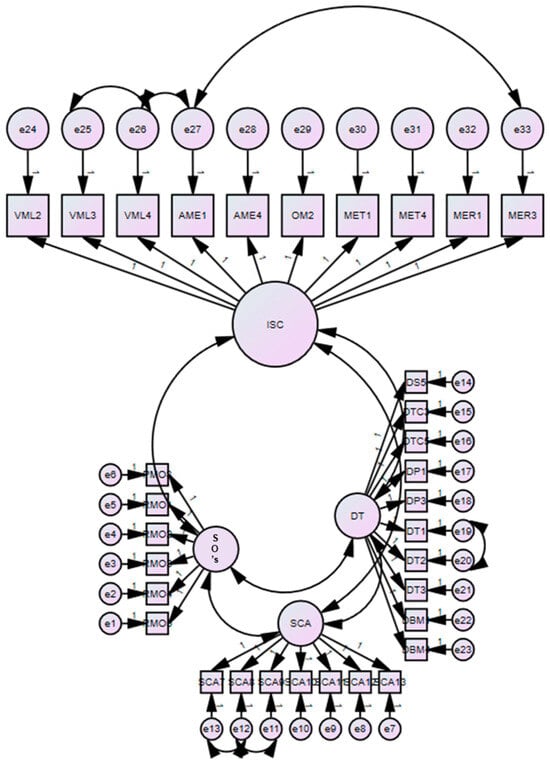

SPSS Version 26 was used to run the confirmatory factor analysis and test the measurement model (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Measurement model analysis.

The examination of the data yielded the subsequent findings following the incorporation of modification index recommendations: Chi-square (X2) to test the difference between the sample covariance matrix and model-implied covariance matrix found as X2 [512] = 694.875; the significance found as p < 0.001; the comparative fit index found as CFI = 0.929; Tucker–Lewis Index found as TLI = 0.927; standardized root mean square residual found as SRMR = 0.0689; root mean square error of approximation found as RMSEA = 0.044.

These outcomes substantiate the presence of an acceptable and robust model. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) plays a pivotal role in delineating the extent to which a measurement model accounts for covariance within a study sample [117]. The comparative fit index (CFI), a key metric assessing the measurement model, exceeds the benchmark of 0.9, denoting a commendable fit. The CFI’s proximity to 1 signifies a closer alignment with a perfect fit, aligning with the insights from Cheung and Rensvold (2002) [118]. Additionally, the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), nearing the 0.95 threshold, aligns with the criteria put forth by Hu and Bentler (1999) [119] as indicative of a favorable model fit. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) in this study stands at 0.084, within the acceptable range of 0.05 to 0.10. This adherence to the suggested threshold of 0.08 by Hu and Bentler (1999) [119] further fortifies the model’s credibility. Furthermore, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), at 0.044, falls below the recommended cutoff of 0.08. In essence, the metrics derived from the CFA underscore the robustness and adequacy of the model in explaining covariance within the study sample. The alignment of these findings with established thresholds and prior research bolsters the confidence in the reliability and validity of the measurement model employed.

We started by performing linear regression to assess H1, H2, and H3. The regression results are summarized in Table 6 and Table 7 below, which show acceptance of all the above hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3).

Table 6.

Linear regression results.

Table 7.

Regression coefficients, inferential statistics, and diagnostic measures.

As previously mentioned, we employed SPSS [114] for regression analysis to examine our hypotheses. Concerning H1, our findings displayed a positive and statistically significant correlation between strategic orientations (SOs) and sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) (refer to Table 5 and Table 6). Moreover, the combined impact of strategic orientations (SOs) and digital transformation (DT) on sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) also revealed a positive and significant association (refer to Table 6 and Table 7). This underscores that both strategic orientations (SOs) alone and their joint effect with integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs) positively influence sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) within the service industry.

Based on the above regression results, we can consider H1: Strategic orientations are positively related to achieving the sustainable competitive advantage of firms (SO’s → SCA). H1 evaluates whether SO’s has a significant impact on firms’ sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). The results concluded that SO’s has a significant effect on SCA (β = 0.414, T = 4.192, p = 0.001). Hence, H1 is not rejected.

H2: Strategic orientations are positively related to achieving integrated strategic capabilities (ISC) (SO’s → ISC). H2 evaluates whether SO’s have a significant impact on firms’ integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs). The results concluded that SO’s have a significant effect on ISC (β = 0.376, T = 7.059, p = 0.000). H2 is not rejected.

H3: Integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs) are positively related to achieving firms’ sustainable competitive advantage (ISC → SCA). H3 evaluates whether ISCs have a significant impact on firms’ sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). The results concluded that ISCs have a significant effect on SCA (β = 0.557, T = 4.622, p = 0.000). H3 is not rejected.

Subsequently, we performed structural equation modeling using the SPSS to test our hypotheses (H4 and H5). We used the SO’s construct, the combined AMC–MA construct named integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs), and the SCA construct during the analysis as high-order constructs. The model produced acceptable fit indices, as explained in the sections above in AMOS analysis.

For the mediation influences (H4), we performed structural equation modeling using the SPSS to assess the effect of ISC mediation. To assess the statistical significance of the model’s estimates, we used a single-step mediator model with a bootstrapping method. Bootstrapping is a more valid and robust method for testing the mediation effects than other commonly used techniques [120]. In this study, bias-corrected bootstrapping results were used to evaluate the significance, with all bootstrap results for the indirect effects based on a confidence level of 95% and 5000 bootstrap samples, as suggested by Hayes (2009) [120]. The model produced acceptable fit indices, as explained in the sections above.

This study assessed the mediating role of integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs) in the relationship between strategic orientations (SOs) and sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). The results revealed a significant indirect effect of the integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs) on sustainable competitive advantage (b = 0.4083, t = 3.0433), supporting H4. Furthermore, the direct effect of strategic orientations in the presence of the mediator was found to be significant (b = 0.2608, t = 2.3916). Hence, integrated strategic capabilities (ISCs) partially mediated the relationship between strategic orientations (SOs) and sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). The mediation analysis summary is illustrated in Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11.

Table 8.

Mediation analysis summary.

Table 9.

Moderated mediation (direct relationships) analysis.

Table 10.

Moderated mediation (indirect relationships) analysis.

Table 11.

Moderated mediation analysis summary.

As shown in Table 11, the conditional indirect effect shows that the indirect effect is low at low DT, increased at average DT, and further increased at higher DT. However, the indirect effect at low DT is not significant, while it is significant at average and higher DT levels. The indirect effect in the presence of the moderator (at mean level) is 0.1099, and as per the bootstrap, this is within the confidence interval at p < 0.05. In addition, it is obvious that the index of moderated mediation is significant. Thus, we can confirm that the indirect effect is moderated by the digital transformation.

The results of the moderated mediation direct relationships analysis indicate with unstandardized coefficients ranging from 0.18 to 0.40 and corresponding t-values between 2.30 and 4.50, the moderated mediation analysis results show statistically significant direct effects, indicating moderate-to-strong effect magnitudes and strong support for the suggested hypothesis.

H4: Integrated strategic capabilities positively mediate the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage (SO’s → ISC → MA). H4 evaluates whether integrated strategic capabilities mediate (explain) the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage. The results concluded that ISCs significantly mediate this relationship indirectly, as explained in the following paragraphs (β = 0.1579, LLCI = 0.0772, ULCI = 0.2463). Moreover, our analysis identified a positively significant indirect effect between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage through ISC (β = 0.1579, LLCI = 0.0772, ULCI = 0.2463) (refer to Table 7). Consequently, ISC significantly serves as a mediator in the connection between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage. Additionally, from the statistical model, we observed the positive and significant influence of digital transformation on ISC. Furthermore, the interaction effect of strategic orientations and digital transformation (SO’s x * DT) on ISC also exhibited positivity and significance (β = 0.3978, t = 12.6406). Hence, a digital transformation effectively moderates the relationship between strategic orientations and ISC. Referring to H3, our analysis revealed that the conditional indirect effect of strategic orientations on sustainable competitive advantage through ISC weakened when digital transformation was low (indirect effect = 0.1544, LLCI = 0.0737, ULCI = 0.2488). However, this conditional indirect effect remained significant when the digital transformation was high (indirect effect = 0.1005, LLCL = 0.0465, ULCL = 0.164) (refer to Table 10). This demonstrates the theoretical background illustrated earlier—the higher the digital capability is, the greater the success is. Hence, H4 is not rejected.

The moderated mediation indirect effects show a significant relationship at high levels of digital transformation and their effect on integrated strategic capabilities is higher when DT is high. The index of moderated mediation shows a significant relationship.

H5: Digital transformation positively moderates (strengthens) the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage in the presence of integrated strategic capabilities (ISC), (DT x*SO’s → ISC → SCA). Finally, H5 suggested that the indirect effect of strategic orientations (SOs) on sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) through integrated strategic capabilities (AMC–MA) will be moderated by the role of digital transformation. H5 is supported as the index of moderated mediation (index = 0.0749, 95% CI = [0.0130/0.1521]) is significant since the 95% CI does not include zero. Moreover, the moderated mediation results further show a significant indirect effect (0.1091) together with a significant direct effect (0.2608), with a t-value of 2.3916 and non-zero confidence intervals, showing partial mediation and supporting the presence of a conditional indirect relationship. Hence, H5 is not rejected.

As the new technologies are evolving and excelling so fast, enterprises globally are transforming digitally and changing to overcome the aggressive competitiveness within the ecosystem. Enterprises are accelerating to offer digital products and solutions to remain viable for a longer term while continuing their journey of building their distinctive capabilities to integrate and align critical competencies with partnerships. Integrating these capabilities not only enhances an enterprise’s responsiveness to environmental shifts but also empowers it to leverage digital prospects and shield against digital risks, offering a more complex comprehension of dynamic capabilities [58,102,110,121]. By assessing a sample of enterprises from the UAE, this study endeavored to examine the intervening role of digital transformation and integrated strategic capabilities in the relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage. From this point of view, the study revealed several key findings.

In brief, it was found that strategic orientations (proactive market orientation, responsive market orientation, and innovation orientation) enhance sustainable competitive advantage. In addition, strategic orientations increased integrated strategic capabilities which in turn improved sustainable competitive advantage. Also, digital transformation was found to moderate the mediation relationship between strategic orientations, integrated strategic capabilities, and sustainable competitive advantage. These findings are discussed below.

Applying the strategic orientations (SOs) to explain the link between digital transformation, integrated strategic capabilities, and sustainable competitive advantage improves our understanding of the dynamic capabilities’ micro-foundation routines, embracing their role in driving higher excellence levels for firms competing in an aggressive digital ecosystem and justifying the various cultural programs and strategic initiatives accordingly. This piece of work provides secondary evidence that enterprises with strategic orientations perform better in the longer term, sustain competition, and are able to develop integrated strategic capabilities (adaptive and ambidextrous) based on robust digital strategy while transforming digitally to benefit from the speeding introduction of new technologies such as AI, cloud, data analytics, and all associated strategic investments [49].

Thus, this study contributes to the empirical studies that provide the valuable impact of strategic alignment capability resulting from strategic orientations and dynamic capabilities (adaptive and ambidextrous) [12,35,36,37,48,50] and the significant effect of digital transformation on firms’ sustainability in today digital environment [9,24,47,49]. Our study also shows that enterprises with higher strategic orientations build up higher strategic aligning capabilities that are both adaptive and ambidextrous in nature while transforming digitally. The study outcomes surpass emphasizing the impact of the integrated strategic capabilities of the firm on its sustainability. With this direct connection between strategic orientations and integrated strategic capabilities, we advance the existing knowledge by uncovering the clear effect of strategic orientations on building futuristic strategic aligning capabilities [35] in a world where competition is moving away from industries to ecosystems, necessitating firms’ adaptiveness and ambidextrous capabilities to establish the alignment between enterprises and their stakeholders. The study showed also that a low level of digital transformation is associated with a non-significant relationship between strategic orientations and sustainable competitive advantage through integrated strategic capabilities. This is an interesting finding reinforcing that enterprises, to enhance their strategic capabilities in the digital era, need to attain higher digital maturity reflected in their digital strategy, digital culture, digital processes, digital technologies adoption rate, and their digital business models’ maturity. This finding supports Schnider et al.’s (2023) [49] view on higher order capabilities that highlight a complex hierarchical and contextual interplay, allowing businesses to take advantage of firm-external opportunities to modify intra-firm operational capabilities, resources, and competences [10]. Their results imply that changing business models (e.g., business model innovation) or process logics (e.g., efficiency-related innovation) is typically necessary to gain performance benefits from digital technologies [47]. The study also supports both Ed-Dafali et al. (2023) [35] and Saleh et al. (2023) [99], who have linked strategic orientations with sustainable competitive advantage, emphasizing the leadership and culture as prerequisites for higher performance when mediated by ambidexterity capability. In other words, dynamic capabilities are a crucial coping strategy for enhancing performance, reconfiguring the firm’s strategic resources towards achieving competitive advantage.

The results of the study align with the latest findings on dynamic capability, indicating that although competitive advantage focuses on how businesses are positioned within their industry, advantage in dynamic contexts necessitates flexibility and ongoing innovation [51]. As highlighted and illustrated by Al Jabri and Lahrech (2025) [48], the intersection of these integrated strategic capabilities becomes evident and is a subject for future researchers’ considerations. This study uncovered the vital role of digital transformation in firms’ sustainability in a highly dynamic competitive environment, where adaptive firms are those that are able to strategically change/transform themselves and develop unique adaptive ambidextrous integrated capabilities, recognized as having imitable resources in the marketplace. As a result, the call of Warner and Wager (2019) [32] to investigate the integration of DC while transforming digitally is investigated and clarified. This study concluded the positive effect of strategic orientations on firms’ sustainability, enabling successful digital transformations, which yield strategic integrated capabilities that differentiate firms as adaptive in nature within their technological ecosystem [12,16,19,20].

Regarding the critical roles of strategic orientations in building integrated strategic capabilities, this result could be interpreted as follows. In today’s environment and set up, firms are in a race to develop digital capabilities to offer new digital products and services to enhance their profitability and growth in a sustainable manner. This opinion is supported by this study’s business environment, where the government of the United Arab Emirates is taking several proactive steps to establish itself as one of the world’s most prominent and highly regarded nations driving higher AI adoption. The government also supports entrepreneurs, start-ups, and digital accelerators through promoting digitalization across sectors, which promotes collaboration and the collaborative spirit that is permeating the entire country [122,123]. This is consistent with the country’s objective of using digitalization to maintain a sustained competitive advantage both locally and globally.

Service firms which are transforming digitally in the UAE reveal a higher tendency for improving their digital maturity and aligning with the government’s digital initiatives and hence are developing strong strategic digital capabilities. Considering this viewpoint, this study uncovers a positive link between the integrated strategic capabilities (dynamic, adaptive, and ambidextrous) and sustainable competitive advantage, with digital transformation moderation’s influence.

The study considers dynamic capability theory as a foundation. According to the dynamic capabilities’ framework, firms can gain a competitive edge in an unpredictable business environment by identifying, seizing, and changing or rearranging their business models [10,47]. This makes it possible for businesses to develop the strategic competencies that are required to respond to customer needs by offering innovative products and solutions, improving their agility in grabbing business opportunities before competitors, and developing the appropriate strategies to transform in a way that allows them to adapt to digital ecosystems with new business models [124] and to the constant change that occurs on a continuous basis so that they remain viable [37,47,52]. As shown in Figure 1, the study emphasizes the significance and influence of transformative factors as sources for enterprises’ sustainable competitive advantage.

5. Conclusions