Abstract

This study investigates the efficiency of higher education systems across the 27 Member States of the European Union during the period 2017–2022, addressing increasing policy interest in data-driven decision support and optimization techniques for performance evaluation in education systems. Efficiency is assessed using Stochastic Frontier Analysis, an optimization-based econometric approach, applied to multiple output dimensions relevant to learning analytics: alignment between graduates’ skills and labour market requirements, scientific productivity measured by published articles, and the number of higher education graduates. The model incorporates key input variables, including the student–teacher ratio, public expenditure per student, research and development expenditure, and the number of academic staff, while controlling for real gross domestic product per capita. To support integrated efficiency measurement and information-based decision-making, multidimensional outcomes are aggregated into composite efficiency indices using entropy-based weighting. The results reveal substantial cross-country heterogeneity in efficiency across EU higher education systems, identifying a cluster of high-performing countries that consistently optimize scientific output and graduate production. Financial resources and academic staff availability emerge as significant drivers of efficiency, while skill matching to labour market demand remains a persistent structural challenge. By combining Stochastic Frontier Analysis with entropy-based aggregation, this study provides a robust data-driven decision support framework for efficiency assessment, offering valuable insights for education policy design, resource allocation, and learning-oriented system optimization.

1. Introduction

Higher education is one of the essential pillars of economic and social development, being responsible not only for human capital formation, but also for generating knowledge and supporting innovation capacity through information-based systems of teaching and research. Within the European Union (EU), where educational convergence and the harmonization of quality standards are strategic objectives, analyzing the efficiency of higher education systems has become a priority for researchers and policymakers, particularly in the context of data-driven decision support for public policy. The relevance of this analysis is amplified by the current challenges posed by rapid technological change, evolving labour market structures, and the growing need to adapt graduates’ skills using insights derived from learning analytics.

Previous studies have proposed a range of tools for assessing educational performance, from simple indicators such as graduation rates to advanced frontier and optimization techniques, which allow for the estimation of relative efficiency and the identification of sources of technical inefficiency. Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) has emerged as a rigorous and flexible method capable of capturing the impact of resources on educational outcomes; however, the literature continues to highlight difficulties in selecting relevant variables and integrating the multiple dimensions of higher education into a single, coherent efficiency measurement framework.

In this context, this study aims to measure the efficiency of higher education systems in the 27 Member States of the EU for the period 2017–2022, adopting a multidimensional and data-driven approach that includes the alignment of skills with labour market requirements, scientific and teaching productivity reflected in published articles, and the number of graduates. The results are explained by means of the financial and human resources available, supplemented by economic indicators that reflect the overall development context. The proposed methodology combines the estimation of efficiency scores through SFA with the use of entropy-based weighting to construct composite indices, allowing for a robust and comparable assessment of performance at the European level and enhancing decision support capabilities.

Through this methodological combination, this paper makes a significant contribution to the literature by providing a rigorous mathematical and optimization-oriented framework that overcomes the limitations of one-dimensional approaches. The study highlights the role of financial resources in improving skill matching and supporting graduation outcomes, reveals the importance of academic human resources for scientific productivity, and shows how the level of economic development shapes educational efficiency in different ways. At the same time, the analysis emphasizes the existence of significant heterogeneity among Member States, confirming that some countries achieve high and consistent performance, while others face structural constraints that require adjustments to educational and funding policies.

The originality of the research lies in the integration of SFA with the entropy method, which provides a transparent, objective, and data-driven ranking of countries, as well as in its application to a complete and recent sample of the EU, enabling both inter-state comparison and the identification of emerging efficiency patterns. The paper thus proposes an analytical framework that can be replicated in other contexts and represents a valuable decision support tool for informing resource allocation, optimizing educational policies, and adapting university academic curricula to labour market dynamics.

The structure of this study is organized as follows: The first part presents the theoretical framework and a review of the literature on higher education efficiency, followed by a section dedicated to the research methodology and data description. Subsequently, the empirical results obtained by applying SFA, constructing the composite efficiency index, and performing robustness tests are presented, and finally, the main conclusions, policy implications, and directions for future research are formulated.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Efficiency of the Educational Process and Financial Resources

The efficiency of the educational process constitutes a core dimension in the evaluation of higher education systems, reflecting the ability of universities to transform financial and institutional inputs into educational outcomes, such as graduates and completion rates. A large body of literature conceptualizes higher education as a production process in which resources are converted into human capital, an approach extensively reviewed by Jain and Gulati (2025), who document the dominance of frontier-based methods, particularly DEA and SFA, in efficiency studies over the last four decades [1].

From a theoretical perspective, the allocation of financial resources plays a decisive role in shaping educational efficiency. Hierarchical and differentiated allocation models suggest that efficiency gains arise when funding is aligned with institutional capacity and student characteristics. Sallee et al. (2008) demonstrate that optimal allocation mechanisms account for heterogeneity in student ability and congestion effects, allowing education systems to exploit economies of scale while minimizing inefficiencies [2]. This framework provides a strong conceptual justification for modelling educational outcomes within an efficiency frontier context.

Empirically, recent studies have increasingly employed SFA to evaluate the efficiency of higher education institutions and systems. Bouzouita and Kooli (2024), using SFA for Tunisian higher institutes, show that financial inputs significantly affect institutional performance, while also revealing substantial inefficiency across institutions [3]. Similarly, Tran and Tran (2025), in their analysis of Australian universities, provide robust evidence that government financial assistance contributes positively to educational efficiency, although the magnitude of the effect depends on institutional and contextual factors [4].

Beyond funding levels, performance-based and optimization-oriented allocation mechanisms further enhance efficiency. Studies applying data-driven optimization techniques highlight that financial resources per student are most effective when combined with institutional accountability and measurable performance indicators [5,6]. Performance-based financial management models, such as those discussed by Ušpurienė et al. (2017), strengthen the link between funding, teaching quality, and educational outcomes, reinforcing the relevance of financial inputs in efficiency-oriented models [7].

Taken together, the literature indicates that financial resources per student constitute a fundamental determinant of the efficiency of the educational process, provided that allocation mechanisms account for institutional heterogeneity and performance incentives. These insights justify the inclusion of financial resources per student as a key explanatory variable in efficiency models of higher education. Based on these theoretical and empirical considerations, we formulate the following research hypothesis:

H1.

Financial resources allocated per student significantly influence the efficiency of the educational process, contributing to improved educational outcomes.

2.2. Scientific Productivity and Academic Human Resources

Scientific productivity represents the second major dimension of higher education performance and reflects the research function of universities. In efficiency-oriented frameworks, scientific output, most commonly measured by published articles, is primarily driven by academic human resources, rather than financial inputs alone. Comprehensive reviews of higher education efficiency research emphasize that human capital is central to knowledge production, while also highlighting the presence of non-linear effects and diminishing returns [1].

Empirical evidence from European universities confirms that expanding academic staff does not automatically result in proportional increases in scientific output. Šimčisko (2025) shows that knowledge production is subject to scale effects and coordination constraints [8], while Kenna and Berche (2012) identify a critical mass beyond which research group productivity begins to decline due to communication and management inefficiencies [9]. These findings suggest that research efficiency depends not only on staff quantity, but also on team structure and internal cohesion.

Recent methodological advances allow for a more nuanced modelling of scientific productivity. Johnes, Tsionas, and Izzeldin (2025) propose multi-stage stochastic frontier models capable of capturing complex research production processes involving multiple outputs and interdependent stages [10]. Such approaches are particularly relevant in higher education systems where teaching and research activities coexist and interact.

In addition to quantitative aspects, institutional environments and human resource management practices play an important role in shaping research efficiency. Ryazanova and Jaskiene (2022) emphasize that merit-based evaluation, academic autonomy, and interdisciplinary collaboration enhance individual research productivity [11]. Evidence from scientometric studies further shows that differences in publication output and citation impact are strongly associated with individual and institutional characteristics, rather than funding alone [12,13].

Overall, the literature supports the view that academic human resources constitute the primary input in the production of scientific output, justifying their central role in efficiency models focused on research performance. In this context, we formulate the following research hypothesis:

H2.

The size of academic human resources is a major determinant of scientific productivity, measured by published articles.

2.3. Skills Matching, Labour Market Outcomes, and Economic Development

The third dimension of higher education efficiency concerns the alignment between educational outputs and labour market requirements, commonly captured through indicators of skills matching. Unlike educational and research efficiency, this dimension reflects the interaction between higher education systems and the broader economic environment.

The literature highlights a bidirectional relationship between economic development and educational efficiency. Higher levels of economic development are associated with better educational infrastructure, stronger institutional frameworks, and more intense research activity, which support scientific productivity and innovation [14]. At the same time, advanced economies face rapid technological change and structural shifts in labour demand, increasing the risk of skills mismatch when educational systems fail to adapt curricula accordingly.

Empirical studies show that significant investment in education does not necessarily translate into improved labour market outcomes. Tudor et al. (2023) document persistent mismatches between education and labour market needs even in contexts characterized by sustained educational spending [15]. Similarly, Obadić and Viljevac (2024) demonstrate that matching efficiency varies considerably across labour market segments, with education playing a differentiated role depending on institutional and economic conditions [16].

Within the EU, these dynamics result in substantial cross-country heterogeneity. While economically advanced countries benefit from stronger research performance, they may simultaneously experience lower efficiency in terms of skills alignment, reflecting structural rigidities and delayed curricular adaptation. Consequently, economic development acts both as a driver of research capacity and as a potential constraint on the relevance of educational outcomes for labour market integration. Based on this empirical evidence, we formulate the following research hypothesis:

H3.

The level of economic development has a differentiated influence on higher education efficiency, supporting scientific productivity while constraining the alignment between educational outcomes and labour market requirements.

2.4. Structural Heterogeneity Across European Union Member States

A recurring theme in the literature is the pronounced heterogeneity in higher education efficiency across EU Member States. Comparative studies consistently identify distinct efficiency patterns shaped by differences in institutional size, funding structures, governance models, and technology adoption [17,18].

Recent evidence confirms the existence of a core group of high-performing countries alongside a group facing persistent structural constraints [19]. National regulatory frameworks and governance traditions continue to condition the efficiency potential of higher education systems, limiting the effectiveness of uniform policy interventions.

Recognizing this heterogeneity is essential for interpreting efficiency scores derived from SFA and for formulating differentiated policy recommendations at the European level. Based on these findings, we formulate the following research hypothesis:

H4.

There is significant heterogeneity among EU Member States in terms of higher education efficiency, leading to the emergence of a core group of high-performing countries and a group requiring structural policy adjustments.

By structuring the literature around educational process efficiency, scientific productivity, and skills matching, this review establishes a coherent conceptual framework linking theory, variable selection, and empirical modelling. Building on recent reviews and methodological advances in SFA, the present study integrates financial, human, and economic dimensions into a unified efficiency assessment of higher education systems in the EU.

3. Data and Methodology

To evaluate the efficiency of higher education systems in the EU, this study adopts a data-driven methodological framework based on SFA combined with the construction of composite efficiency indices using an entropy-based weighting method. This integrated approach allows for the simultaneous assessment of multiple dimensions of higher education performance while accounting for structural heterogeneity across countries. The empirical analysis covers the 27 Member States of the EU over the period 2017–2022, corresponding to the most recent years for which harmonized and comparable data are available.

The dataset is compiled exclusively from official and internationally recognized sources—Eurostat, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP), and Scimago Journal & Country Rank—to ensure data reliability, consistency, and cross-country comparability. These institutions provide harmonized indicators collected under standardized methodological frameworks, which is a prerequisite for cross-national efficiency analysis and information-based decision support. The use of nationally aggregated data further ensures temporal and spatial uniformity, enabling the estimation of stochastic efficiency frontiers within a common analytical framework across all Member States.

The methodological design follows a multidimensional production framework, in which higher education systems simultaneously generate outcomes related to teaching effectiveness, scientific productivity, and labour market relevance. Consistent with the higher education economics literature, these outcomes are modelled using output-specific production frontiers, each defined by a tailored set of input and contextual variables reflecting the underlying production process. This approach avoids imposing a single production structure on fundamentally different outputs and improves the interpretability of efficiency estimates.

3.1. Variable Selection and Conceptual Framework

Table 1 presents the variables included in the analysis, distinguishing between input variables (resources and contextual conditions) and output variables (performance outcomes). The selection of variables is guided by theoretical considerations and empirical evidence in higher education economics, with particular attention to the role each variable plays in defining the feasible production frontier.

Table 1.

Presentation of variables included in analysis of higher education efficiency.

Efficiency analysis involves the systematic introduction of input and output variables within a data-driven efficiency measurement framework. In this study, six input variables and three output variables are selected to assess the efficiency of higher education systems.

The output variables reflect different but complementary dimensions of academic education performance, namely the relationship with the labour market, scientific research outcomes, and teaching effectiveness, consistent with a multidimensional learning analytics perspective.

The first output variable included in the efficiency analysis is Skills Match, a composite index that captures the alignment between skills required by the labour market and those available among employees. This indicator is calculated based on two dimensions: skills underutilization and skills mismatch, manifested by unemployment, skill deficit, skill surplus, or discrepancies between the educational level of employees and labour market requirements. The input variables associated with this output are the student-to-faculty ratio and public expenditure on education per student, which are widely used in the empirical literature as key determinants of educational efficiency.

The second output variable considered is Published articles, which serves as an indicator of scientific efficiency. This output is modelled as a function of the number of academic staff and expenditure on research and development, reflecting the role of human and financial resources in research productivity. The variable real gross domestic product per capita is included as a control variable for this output, capturing the broader economic context that conditions research performance within a context-aware efficiency framework. Real gross domestic product per capita reflects structural differences in economic development, investment capacity, and public service provision, factors that shape educational performance without directly reflecting institutional technical efficiency. Previous research shows that ignoring macroeconomic heterogeneity can generate omitted-variable bias in efficiency estimation [20]. Including real gross domestic product per capita improves both the accuracy and interpretability of SFA estimates by controlling for structural conditions that shape the feasible efficiency frontier.

The third output variable is Graduates, through which the efficiency of teaching-related input resources is evaluated, namely public expenditure on education per student and the number of students enrolled in higher education.

This output allows for the assessment of how efficiently financial and enrolment-related resources are transformed into educational outcomes.

3.2. Output-Specific Stochastic Frontier Models

Efficiency analysis is conducted by estimating stochastic frontier models of the general form proposed by Aigner, Lovell, and Schmidt (1977) [21]. For each output variable, the following Cobb–Douglas production function is specified:

with the composite error term defined as follows:

where denotes the output of country i, is the input variable (j for country i), and are the parameters to be estimated, is a symmetric random error capturing statistical noise, and is a non-negative term representing technical inefficiency. This formulation allows observed deviations from the frontier to be decomposed into random shocks and inefficiency, improving the robustness of efficiency estimates [21].

- Skills Match Frontier

The first stochastic frontier models Skills Match as the output variable. This indicator reflects the degree to which skills supplied by the education system correspond to labour market needs, incorporating aspects such as overqualification, skill shortages, and underutilization. The production frontier for Skills Match is defined by teaching-related inputs, namely the student-to-staff ratio and public expenditure on education per student, which directly influence instructional quality, learning environments, and curriculum relevance.

In addition, real GDP per capita is included as a contextual control variable. GDP per capita captures structural economic characteristics such as technological intensity, sectoral specialization, and labour market complexity. In more economically advanced countries, rapid structural change may increase the likelihood of skills mismatch if educational systems adjust with delays. Consequently, GDP per capita may exhibit a negative marginal association with observed skills matching efficiency, reflecting labour market dynamics rather than institutional inefficiency. Including this variable ensures that the estimated frontier accounts for heterogeneous economic conditions and avoids attributing context-driven mismatch to inefficiency.

- Scientific Productivity Frontier

The second frontier models Published Articles as an indicator of scientific productivity. This output is generated through a research-specific production process that differs fundamentally from teaching-related activities. Accordingly, the frontier is defined by the number of academic staff and expenditure on research and development (R&D), which capture the core human and financial inputs into knowledge production.

Real GDP per capita is also included as a contextual variable in this model, reflecting national innovation capacity, research infrastructure, and broader economic conditions that influence scientific output. In contrast, public expenditure on education per student is excluded from this frontier, as it primarily finances teaching and student-related activities rather than research. This exclusion avoids conflating teaching-oriented and research-oriented inputs and preserves a clear separation between production functions.

- Graduates Frontier

The third frontier models Graduates as the output variable, capturing the efficiency with which higher education systems transform enrolled students into completed degrees. The production frontier is defined by the number of students enrolled in higher education, representing the scale of educational activity, and public expenditure on education per student, which reflects the financial capacity to support instruction, academic services, and completion-oriented policies.

The inclusion of public expenditure per student in both the Skills Match and Graduates models reflects its dual role as a teaching-related input affecting both the relevance of acquired skills and the likelihood of successful degree completion.

3.3. Construction of Composite Efficiency Indices

For each output-specific stochastic frontier, efficiency scores are obtained for each country and year. These scores summarize performance relative to the estimated frontier for Skills Match, Scientific Productivity, and Graduates, respectively. To integrate these dimensions into a single synthetic indicator suitable for comparative analysis, an entropy-based weighting method is applied.

The entropy measure proposed by Shannon (1948) is used to quantify the informational content of each output-specific efficiency score [22]. The entropy value for each variable j is determined based on Equation (3).

where denotes the efficiency scores of countries i for output j, and n is the number of observations.

Based on the entropy values, the weights ( associated with each output variable are calculated using Relation (4).

Finally, the composite efficiency index for each country is calculated as a weighted sum of the output-specific efficiency scores (Equation (5)).

This entropy-based aggregation assigns greater weight to dimensions that better differentiate performance across countries, ensuring an objective and transparent integration of multiple efficiency dimensions. The use of entropy weighting is well established in performance evaluation studies in education and related fields and avoids reliance on subjective weighting schemes [22,23,24].

By combining output-specific SFA with entropy-based composite indexing, the proposed framework enables a nuanced and comparable assessment of higher education efficiency across EU Member States. This approach accounts simultaneously for teaching effectiveness, scientific productivity, and labour market relevance, while controlling for structural economic heterogeneity. As emphasized by cross-country efficiency studies in education, incorporating contextual variables and multiple outputs is essential to avoid biassed efficiency estimates and to support evidence-based policy evaluation [20].

4. Empirical Results

This section presents the empirical results of the SFA applied to higher education systems in the EU. The analysis is based on data covering the period 2017–2022 for the 27 EU Member States and aims to identify efficiency patterns across three complementary dimensions: skills matching, scientific productivity, and teaching-related outcomes. The section is structured as follows: first, descriptive statistics are discussed; second, the estimated stochastic frontier models are presented and interpreted; third, the composite efficiency index is constructed and analyzed; finally, robustness checks and interpretative limitations are addressed.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The data presented in Table 2 indicate significant differences among EU Member States in terms of the main dimensions of higher education systems, reflecting the inherent heterogeneity captured by the efficiency measurement framework. The average number of students enrolled in higher education is approximately 666,556, although substantial variation is observed across countries. These differences reflect not only demographic characteristics, but also disparities in institutional capacity, academic infrastructure, and the degree of development of national education systems. Countries with larger populations and more extensive higher education infrastructures record significantly higher enrolment figures, while smaller countries or those with a lower share of young population exhibit markedly lower values. Such discrepancies are further shaped by socio-economic and structural factors, including birth rates, urbanization patterns, national education policies, and levels of public funding allocated to higher education, all of which condition the efficiency outcomes observed in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

The descriptive analysis of data.

In terms of research and development expenditure, the average level is 1.69% of GDP, suggesting a consistent focus of European countries on investment in innovation and knowledge within a data-driven efficiency framework. However, the range of variation, from a minimum of 0.46% to a maximum of 3.49%, in GDP indicates a significant polarization between advanced economies, which have well-developed research resources and infrastructure, and emerging economies, where budget priorities are more focused on other areas of public interest, with implications for efficiency outcomes.

There are also notable differences in the size of academic human resources. The average number of teaching and research staff is approximately 52,021, but the values range from a minimum of 954 to a maximum of 484,301, illustrating extremely different institutional structures and educational capacities between countries, which are captured in the efficiency measurement process. These differences are often correlated with the size of the university network, the level of public funding, the degree of internationalization, and recruitment policies in higher education.

The number of graduates also varies considerably between countries: the average is 153,472 graduates, with extremes ranging from 1725 to 885,933 people. This dispersion reflects not only differences in the size of the university population, but also the specific nature of educational academic curricula, student retention rates, and the degree of correlation between education and labour market demand, a key dimension in learning analytics-oriented assessments.

Overall, the analysis of descriptive statistics confirms the structural heterogeneity of higher education systems in the EU, influenced by economic, social, and demographic factors. This diversity justifies the application of a robust analysis method capable of capturing differences in efficiency between countries and assessing the contribution of each factor to the overall performance of education systems, in support of evidence-based policy decisions.

4.2. Estimation of Efficiency Using SFA

The analysis of higher education efficiency was performed by applying SFA using a Cobb–Douglas function, assuming a truncated normal distribution, with input minimization specification (Table 3), within a data-driven efficiency measurement framework. The estimates were made based on a cross-sectional dataset comprising 162 observations corresponding to the 27 Member States of the EU for the period 2017–2022, ensuring comparability across countries and over time. This approach made it possible to identify differences in efficiency between countries by comparing the performance of education systems to the theoretical efficiency frontier, thereby supporting an optimization-oriented and evidence-based assessment of system performance.

Table 3.

Coefficients of estimated models using the Cobb–Douglas function.

In order to estimate technical efficiency, two functional forms of the production frontier, Cobb–Douglas and Translog, were compared. The selection of the Cobb–Douglas model was supported by the Likelihood Ratio (LR) test, which evaluates the log-likelihoods of the two specifications. Although the Translog model exhibits a slightly higher log-likelihood, the calculated LR statistic did not exceed the critical value of the χ2 distribution for the corresponding degrees of freedom.

Efficiency estimation is conducted using SFA with a Cobb–Douglas functional form and a truncated normal inefficiency distribution. Three separate models are estimated, each corresponding to a distinct output dimension: Skills matching (Model 1), Published articles (Model 2), and Graduates (Model 3). This output-specific approach allows each dimension to be evaluated using a frontier that reflects its underlying production process.

- Model 1: Skills matching

Model 1 evaluates the efficiency with which higher education systems contribute to aligning skills with labour market requirements. The estimated coefficients indicate that the student–staff ratio has a negative and statistically significant effect, suggesting that higher teaching loads reduce the capacity of institutions to deliver labour-market-relevant skills. Public expenditure per student exhibits a positive and highly significant coefficient, confirming the role of financial resources in supporting teaching quality, curriculum development, and learning environments.

Real GDP per capita enters the model with a negative and statistically significant coefficient. This result should be interpreted as a contextual effect rather than evidence of institutional inefficiency. In more economically advanced countries, labour markets are typically more dynamic and technologically complex, increasing the likelihood of skills mismatch when educational systems adjust more slowly than economic structures. Consequently, higher GDP per capita may be associated with lower observed skills matching efficiency, reflecting labour market complexity rather than weaker educational performance.

The high value of the gamma parameter indicates that most of the unexplained variation is attributable to inefficiency rather than random noise. The average efficiency score suggests that, on average, EU higher education systems operate below their potential in terms of skills alignment, leaving room for improvement through better coordination between education and labour market needs.

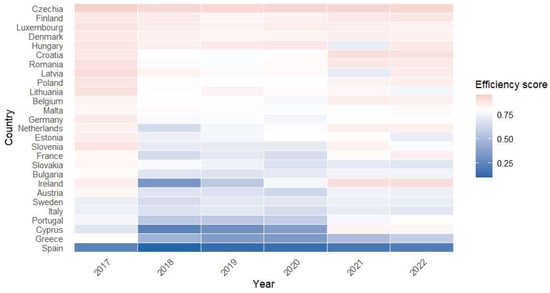

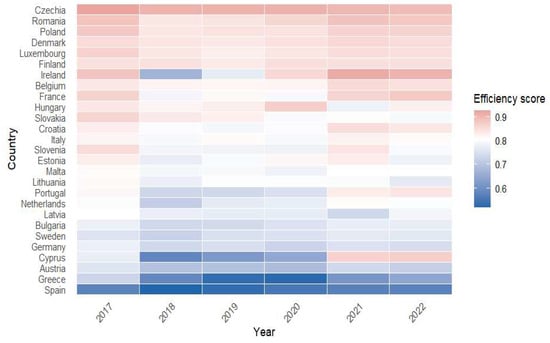

The efficiency scores for the Skills matching variable estimated after applying the SFA for each EU country are shown in Figure 1 and the estimated efficiency scores for this output are reported in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Efficiency scores for Skills matching between 2017 and 2022.

The results obtained for the Skills matching variable provide an important empirical basis for identifying countries that are located on the efficiency frontier and those that deviate significantly from it, supporting comparative assessment and decision-oriented analysis. The distribution of efficiency scores for each Member State of EU is shown in Figure 1, providing a clear picture of the relative positioning of countries in relation to the optimal performance estimated by the model.

The heatmap highlights the significant heterogeneity in technical efficiency across European countries, as well as the persistence of relative positions over time. Countries in Northern and Western Europe remain close to the efficiency frontier, while some countries in the South and East show lower levels, suggesting structural differences in resource use. Countries such as the Czech Republic, Finland, Luxembourg and Denmark consistently perform efficiently and stably, close to the frontier, while countries such as Spain, Greece and Cyprus frequently show persistent structural inefficiency during the period analyzed.

- Model 2: Scientific productivity (Published articles)

Model 2 assesses scientific productivity using the number of published articles as an output indicator. The results confirm the central role of academic human resources: the coefficient for academic staff is positive and highly significant, indicating that larger research-capable staff complements are associated with higher publication output. Expenditure on research and development also has a positive and significant effect, though of smaller magnitude, suggesting that financial support enhances research infrastructure and project capacity without automatically translating into proportional increases in output.

GDP per capita has a positive and significant coefficient, reflecting the influence of broader economic and institutional conditions, such as innovation systems, research infrastructure, and public support for science, on scientific output.

It is important to note that this model captures quantity-based scientific output rather than research quality. Indicators such as citation impact, journal quartiles, or field-weighted metrics are not included and therefore no direct inference is made regarding the qualitative dimension of research performance. This distinction is explicitly acknowledged in the interpretation of results.

The estimated efficiency scores indicate substantial heterogeneity across Member States, with a lower average efficiency compared to the other dimensions, highlighting the uneven distribution of research capacity and productivity across the EU. From the perspective of the model parameters, the high value of the gamma coefficient (0.85) confirms that the differences in efficiency between the countries analyzed are mainly generated by variations in technical performance, rather than by random factors.

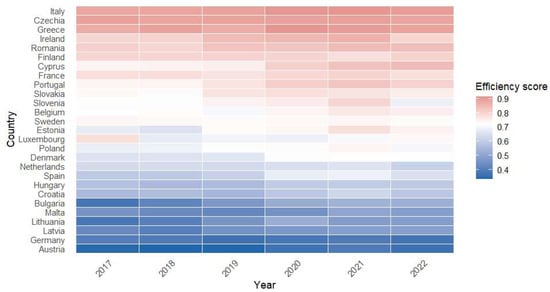

Overall, the model highlights that research efficiency depends to a large extent on the size and quality of human resources, supported by a favourable economic and institutional framework. Thus, public policy strategies aimed at strengthening human resources in research and increasing funding for R&D activities can contribute substantially to reducing performance gaps between Member States and improving efficiency outcomes. The distribution of efficiency scores for each country is shown in Figure 2, providing a comparative perspective on scientific performance within the EU. The estimated efficiency scores for the output variable Published articles, obtained by applying SFA, are reported in Appendix B.

Figure 2.

Efficiency scores for Published articles between 2017 and 2022.

Figure 2 highlights the technical efficiency scores for Published articles estimated by SFA, revealing significant and persistent differences between countries. A group of countries remains consistently close to the efficiency frontier, including Italy, the Czech Republic, Greece and Ireland, suggesting efficient and stable use of resources. At the opposite end of the spectrum, countries such as Austria, Germany, Latvia and Lithuania consistently have lower scores, indicating persistent structural inefficiencies. Countries such as Romania, Finland and France are in an intermediate efficiency zone, with little variation over time. The relative efficiency hierarchy remains largely unchanged over the period analyzed, including in years marked by exogenous shocks (2020–2021). This pattern suggests that the differences observed are mainly driven by structural and institutional factors, rather than cyclical fluctuations or random noise.

- Model 3: Graduates (teaching-related output)

Model 3 examines the efficiency of higher education systems in generating graduates, using the absolute number of graduates as the output variable. The number of enrolled students exhibits a positive and highly significant coefficient close to unity, indicating an almost proportional relationship between enrolment size and graduate output. This result is mechanically expected when modelling absolute quantities and primarily reflects system scale and capacity rather than completion efficiency at the student level.

Accordingly, Model 3 should be interpreted as capturing the ability of higher education systems to produce graduate output at scale, conditional on available resources, rather than as a measure of graduation rates or individual completion probabilities. Public expenditure per student has a positive and significant coefficient, suggesting that higher per-student funding supports teaching capacity, student services, and institutional mechanisms that facilitate degree completion. GDP per capita also shows a positive association, indicating that favourable socio-economic conditions may support educational performance through improved student support and labour-market incentives for completion.

The model parameters confirm the robustness of the estimation. The gamma coefficient (0.79) indicates that the differences in efficiency observed between European countries are explained mainly by variations in technical performance and less by random factors. The high average efficiency score observed in this model reflects the fact that most European higher education systems are relatively effective in transforming enrolment into graduate output at the aggregate level, though this does not preclude differences in completion rates or dropout patterns at the micro level.

This clarification explicitly addresses the scale-related nature of Model 3 and avoids over-interpretation of near-proportional elasticities.

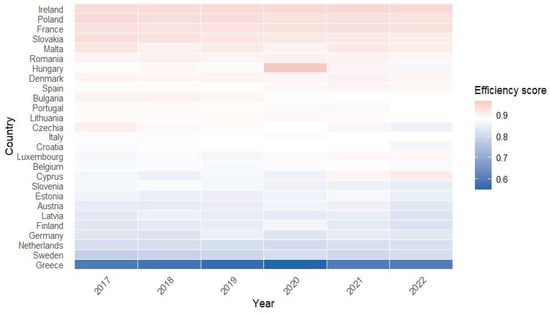

Overall, the results for Model 3 highlight the complementary role of financial resources, institutional capacity, and the economic context in stimulating educational performance. Countries that combine investment in education with effective resource management and student support policies tend to achieve a higher level of university system efficiency in comparative terms. The distribution of efficiency scores for the Graduates variable is shown in Figure 3, providing a comparative perspective on educational performance across the EU. The estimated efficiency scores for the output variable Graduates, obtained by applying SFA, are reported in Appendix C.

Figure 3.

Efficiency scores for Graduates between 2017 and 2022.

Figure 3 shows the technical efficiency scores for graduates estimated by SFA, highlighting persistent differences and low temporal dynamics. Countries such as Ireland, Poland, and France remain consistently close to the efficiency frontier, suggesting efficient and stable use of inputs. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Greece consistently records the lowest scores over the entire period, indicating persistent structural inefficiencies. An intermediate group, including Romania, Hungary, Denmark and Spain, shows average levels of efficiency, with limited variations over time.

4.3. Composite Efficiency Index Based on Entropy Weighting

To obtain an integrated measure of higher education system performance, the efficiency scores derived from the three SFA models are aggregated into a composite efficiency index using the entropy weighting method. Entropy weighting assigns weights based on the dispersion of efficiency scores across countries, thereby reflecting the informational contribution of each dimension rather than subjective importance.

The entropy value for each variable was determined based on the efficiency scores obtained through SFA, according to the standard formula in Equation (3), ensuring methodological coherence between efficiency estimation and aggregation. Applying this method led to the following entropy values:

- For Skills matching:

- For Published articles:

- For Graduates:

The entropy values for all three dimensions are close to unity, indicating relatively concentrated distributions of efficiency scores. This outcome is expected given that efficiency scores are bounded between zero and one and that cross-country differences, while meaningful, are not extreme. Small differences in entropy values nevertheless translate into differentiated weights through the entropy transformation.

The relative weights of each variable were determined according to Relation (4).

- Skills matching:

- Published articles:

- Graduates:

Published articles receive the highest weight, followed by Skills matching and Graduates. This result does not imply that scientific productivity is inherently more important, nor that it exhibits higher average efficiency. Rather, it reflects the fact that scientific efficiency displays greater cross-country variability and therefore provides more discriminatory information within the composite index. Entropy weighting is driven by dispersion, not by mean performance levels.

The composite efficiency index was calculated, according to Relation (5), as a weighted sum of the individual efficiency scores for each country. Thus, each dimension of educational performance contributes proportionally to the final efficiency score according to its informational relevance derived from the data-driven entropy method. The result provides an integrated perspective on the capacity of education systems to transform resources into efficient outcomes through a balanced combination of training quality, scientific performance, and educational outcomes evaluated relative to the efficiency frontier.

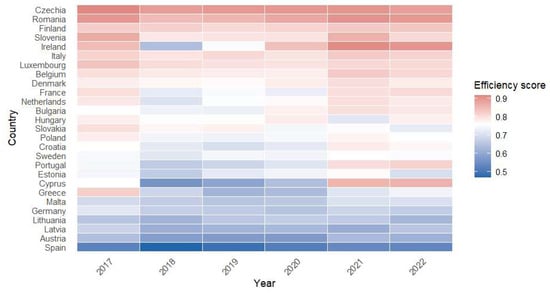

The distribution of composite index values for the period 2017–2022 is illustrated in Figure 4, which highlights the differences in performance between EU Member States in comparative terms. The complete data for the composite efficiency index values obtained for each Member State of EU for the period analyzed are presented in Appendix D.

Figure 4.

Distribution of composite efficiency index values for period 2017–2022 using entropy method.

The results of the composite efficiency index show that the Czech Republic, Romania, Finland, Slovenia, Ireland, Italy and Luxembourg are among the best-performing countries in terms of overall efficiency in higher education according to the aggregated index. In contrast, countries such as Spain, Austria, Latvia, and Lithuania are at the lower end of the ranking, with scores between 0.5 and 0.7, indicating persistent structural deficiencies in resource use. The wide dispersion of values suggests significant heterogeneity among the countries analyzed. This variability highlights the importance of formulating European policies tailored to national specificities, aimed at reducing efficiency gaps between EU Member States.

4.4. Country-Level Patterns and Interpretation

The composite efficiency index reveals a core group of countries that consistently achieve high efficiency across multiple dimensions, alongside a group of countries facing persistent structural constraints. Country-level efficiency scores by model are reported in the corresponding tables and figures, allowing direct verification of relative performance and temporal stability.

Countries positioned near the frontier in multiple models are interpreted as high-performing systems in comparative efficiency terms, while acknowledging that strengths may differ across dimensions. Importantly, no country is uniformly dominant across all outputs, underscoring the multidimensional nature of higher education efficiency.

The results of the composite efficiency index highlight significant differences between EU Member States in terms of the performance of their higher education systems as measured through the data-driven efficiency framework. Based on the values obtained for the period 2017–2022, the Czech Republic, Romania, Finland, Slovenia, Ireland, Italy and Luxembourg consistently rank among the most efficient countries, forming a core of educational and scientific performance in the European area.

According to the composite efficiency index, Czech Republic consistently ranks among the high-performing countries, particularly due to its efficiency outcomes in skills matching and graduate production. Close collaboration between higher education institutions and industry, including internships and cooperative programmes, supports effective skills matching and increases educational matching. Moreover, the strong foundational literacy and digital competencies of students allow tertiary programmes to further enhance human capital efficiently. This targeted approach is reinforced by labour-market incentives, as graduates with relevant qualifications receive notable wage premiums, signalling the economic value of their skills. These findings, measured by the composite index, suggest that Czech higher education produces graduates whose competencies translate into meaningful employment outcomes, exemplifying efficiency in the conversion of educational inputs into socially and economically relevant outputs.

Romania stands out with significant positive developments, particularly due to increases in graduate output and overall scientific publication activity, as captured by the quantity-based indicators used in this study. These results reflect volume-based developments and should not be interpreted as evidence of changes in research quality or field-specific specialization. This performance is also influenced by recent legislative changes, which have introduced more rigorous criteria for evaluating academic staff, with an emphasis on publishing articles in prestigious journals as reflected in the efficiency scores. In addition, Romanian universities have begun to develop closer partnerships with the private sector, favouring the adaptation of study programmes to labour market requirements and stimulating investment in educational and digital infrastructure supporting efficiency improvements.

At the same time, there is a heterogeneous distribution of efficiency across different regions of the EU. Countries in northern and western Europe, such as Finland, Ireland, and Luxembourg, are characterized by a mature model based on innovation, internationalization, and extensive university autonomy. In contrast, some countries in southern and eastern Europe are making rapid progress but still face structural constraints related to funding, infrastructure, or institutional management that limit efficiency improvements.

This polarization highlights the need to harmonize educational strategies at the European level by strengthening cooperation mechanisms between countries and promoting common standards for performance evaluation and evidence-based decision support. The integration of education, research, and innovation policies into a unified framework could help reduce efficiency differences and stimulate convergence between university systems.

Overall, the results confirm the existence of a core group of high-performing countries that are successfully integrating educational resources, research, and economic policy, alongside a group of countries that are still in the process of optimizing resource allocation and adapting to the new requirements of the knowledge-based economy in efficiency terms.

Interpretations related to specific countries are framed cautiously and grounded in measured efficiency outcomes rather than generalized claims. Increases in publication output are discussed strictly as quantity-based developments, without extrapolating to research quality or scientific excellence in the absence of impact-based indicators.

4.5. Robustness Analysis of the Composite Efficiency Index

To assess the stability of the results and verify the methodological consistency of the composite efficiency index, a robustness analysis was performed based on two complementary approaches. The first consists of reconstructing the composite index using the efficiency scores obtained through SFA and applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine the weights associated with each dimension of efficiency. The second aims to verify the external validity of the index by analyzing the correlation with a relevant educational indicator.

- (1)

- Construction of the composite efficiency index using PCA

In the first stage, PCA was applied to the efficiency scores estimated for the three output variables, Skills matching, Published articles, and Graduates, in order to determine the relative importance of each dimension within the composite index derived from the efficiency estimates. In the second stage, the efficiency scores were weighted according to the contribution of each component, and then the composite index was constructed for each EU Member State for the period 2017–2022 in a consistent and comparable manner. The application of PCA involves testing the hypothesis of independence between variables and identifying the optimal number of components that explain most of the total variance in the data. The selection of the principal components was based on the eigenvalues associated with the correlation matrix, presented in Table 4, ensuring methodological robustness.

Table 4.

Total Variance Explained.

The results in Table 4 show that the first principal component has an eigenvalue greater than 1 and explains 43.08% of the total variance, which justifies retaining a single component for the construction of the composite efficiency index within the robustness analysis framework.

The weights associated with each variable were determined based on the correlation coefficients (factor loadings) between the efficiency scores and the extracted principal component. Thus, the weights were calculated using a combination of eigenvalues and correlations between variables and the common factor derived from the PCA results, and the corresponding values are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Calculation of the weighting of variables.

Based on these weights, the principal component equation used to estimate the composite efficiency index was formulated:

F1 = 0.4084·Skills + 0.1620·Articles + 0.4297·Graduates

The composite efficiency index was calculated for each country and for each year analyzed, using the contribution of the main factor to the total variance and the individual values of the sub-indices within the robustness framework. The results obtained, presented in Figure 5, reflect the distribution of composite efficiency index values over the period 2017–2022, highlighting the differences in performance between EU Member States in comparative efficiency terms. The complete data for the composite efficiency index values obtained for each Member State for the period analyzed, determined by applying PCA, are presented in Appendix E.

Figure 5.

Distribution of composite efficiency index values for period 2017–2022 using PCA.

Figure 5 highlights a clear segmentation among Member States of EU, with countries such as the Czech Republic and Romania maintaining high values close to 0.9, indicating solid and stable performance over time. In contrast, countries such as Spain, Greece and Austria have consistently lower scores, around 0.6, signalling persistent structural constraints in the efficient use of resources.

To assess the consistency of the results obtained using the entropy weighting method, a correlation analysis was performed between the composite efficiency index calculated using the entropy method and the composite index obtained through PCA within the robustness assessment framework. The purpose of this step is to verify the stability of the internal structure of the index and the degree of convergence between alternative methods of aggregating efficiency scores in a data-driven manner. The Pearson correlation coefficient calculated for the period 2017–2022 confirms the existence of a strong positive correlation between the two indices (r = 0.845, p < 0.01), which demonstrates a high level of internal consistency and methodological robustness of the model used for comparative efficiency evaluation. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Pearson correlation between the indices calculating by entropy method and PCA.

The results suggest that, regardless of the method used to determine the weights (entropy or PCA), the relative order of countries and the estimated efficiency values are comparable, confirming the stability and empirical validity of the composite efficiency index within the data-driven robustness framework. Therefore, the proposed method provides a robust and credible measure of the performance of higher education systems in the EU for comparative efficiency assessment.

- (2)

- Correlation analysis with an external indicator relevant to education

For the external validation of the composite efficiency index, a correlation analysis was performed between the composite efficiency index (calculated for the period 2017–2022) and an independent educational indicator considered relevant in the literature—inequality in education used as an external validation benchmark. This analysis aims to verify whether higher levels of efficiency in higher education systems are associated with a reduction in educational disparities between states in comparative terms.

The results of the Pearson correlation coefficient, presented in Table 7, show a negative and statistically significant relationship between the two variables (r = −0.288, p < 0.01), supporting the external validity of the efficiency index.

Table 7.

The Pearson correlation coefficient between the efficiency index and inequality in education for the period 2017–2022.

This negative relationship confirms that countries characterized by high efficiency in higher education tend to have lower levels of educational inequality. In other words, an increase in the efficiency of the education system is associated with a more equitable distribution of learning opportunities and a reduction in differences in access and performance between groups as reflected in the composite efficiency framework.

Therefore, the correlation analysis reinforces the conclusion that the composite efficiency index constructed is not only methodologically robust but also relevant from a socio-educational perspective, reflecting the ability of university systems to transform available resources into equitable and high-performing outcomes in efficiency terms.

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite providing a comprehensive and comparative assessment of higher education efficiency across EU Member States, this study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the results.

First, the analysis is based on a relatively short time horizon (2017–2022), which may not fully capture long-term structural transformations in higher education systems. Although this period allows for cross-country comparability using harmonized data, extending the time span in future research would enable a more detailed examination of efficiency dynamics and structural persistence. The application of dynamic panel stochastic frontier models could further enhance the understanding of efficiency trajectories over time.

Second, the study relies exclusively on quantitative indicators derived from internationally comparable databases. While this approach ensures consistency and objectivity, it limits the inclusion of qualitative dimensions such as teaching quality, student satisfaction, curriculum relevance, institutional governance, or academic culture. Consequently, the estimated efficiency scores should be interpreted as reflecting measurable system-level performance rather than holistic educational quality. Future research could address this limitation by integrating survey-based indicators or mixed-method approaches that combine quantitative efficiency estimation with qualitative assessments.

Third, scientific productivity is measured using the number of published articles, which captures output volume but does not account for research quality, citation impact, or journal prestige. As such, the analysis does not allow for direct conclusions regarding scientific excellence. Incorporating bibliometric quality indicators, such as field-weighted citation impact or journal quartiles, would provide a more nuanced evaluation of research efficiency in future studies.

Fourth, although the data sources used (Eurostat, CEDEFOP, Scimago Journal & Country Rank) follow standardized methodologies, cross-country differences in data reporting practices and institutional structures may still introduce measurement noise. While SFA partially accounts for random variation, alternative modelling approaches, including Bayesian SFA or robustness checks based on alternative frontier specifications, could further strengthen empirical validity.

Finally, the composite efficiency index is sensitive to the weighting scheme applied. Although robustness checks using principal component analysis confirm a high degree of consistency with entropy-based weights, future research could explore additional aggregation methods or scenario-based weighting to assess the stability of country rankings under different normative assumptions.

Overall, these limitations do not undermine the validity of the findings but rather delineate the scope within which the results should be interpreted. Addressing these issues offers promising directions for future research aimed at refining efficiency measurement and deepening the empirical understanding of higher education systems in Europe.

6. Conclusions and Implications for Educational Policy

This study provides a multidimensional, data-driven assessment of higher education efficiency across the EU by integrating SFA with entropy-based and principal component weighting methods. By distinguishing between skills matching, scientific productivity, and teaching-related outcomes, the analysis highlights the heterogeneous nature of efficiency across countries and performance dimensions.

The empirical results confirm that financial and human resources play a central role in shaping higher education outcomes, but their effects are neither uniform nor automatic. Investment in education and research is associated with higher performance, yet efficiency depends critically on how resources are allocated and managed. In particular, maintaining balanced student–staff ratios and strengthening academic human capital emerge as key factors for improving system-level efficiency.

From a hypothesis-testing perspective, the findings provide differentiated support for the research hypotheses formulated in this study. Hypothesis H1, which posits a positive effect of financial resources per student on higher education efficiency, is supported by the results for both skills matching and graduate output, confirming the importance of funding in teaching-related production processes. Hypothesis H2 is strongly supported, as academic human resources emerge as the main determinant of scientific productivity across EU Member States. The evidence related to Hypothesis H3 indicates a differentiating role of economic development: higher GDP per capita supports scientific productivity while being associated with lower skills–labour market matching efficiency, reflecting increasing labour market complexity rather than institutional underperformance. Finally, Hypothesis H4 is confirmed by the pronounced heterogeneity observed across Member States, with no country dominating all efficiency dimensions simultaneously.

The analysis also reveals a nuanced role of economic development. Higher levels of GDP per capita support scientific productivity by providing favourable institutional and infrastructural conditions, while simultaneously increasing the complexity of labour markets and the risk of skills mismatch. This finding suggests that efficiency should not be interpreted solely as a function of resource abundance, but also as an outcome of adaptive capacity and institutional responsiveness.

Significant heterogeneity among Member States is evident across all dimensions. Rather than identifying universally “leading” systems, the results point to a group of countries that perform consistently well across multiple efficiency dimensions, alongside others that exhibit strengths in specific areas but face structural constraints elsewhere. Importantly, no country dominates across all outputs, underscoring the multidimensional character of higher education efficiency.

The robustness analysis confirms that the composite efficiency index is stable across alternative weighting methods and exhibits a meaningful negative association with educational inequality. This result suggests that more efficient higher education systems tend to be more inclusive, reinforcing the view that efficiency and equity are not competing objectives but can be mutually reinforcing.

From a policy perspective, the findings emphasize the need for integrated strategies that simultaneously address funding adequacy, institutional capacity, and labour market alignment. Policies aimed at improving higher education efficiency should therefore focus not only on increasing expenditure, but also on enhancing governance structures, supporting academic staff development, and strengthening university–industry linkages. At the European level, the development of harmonized performance monitoring frameworks can support evidence-based decision-making and facilitate convergence within the European Higher Education Area.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the literature by offering a rigorous and transparent framework for the comparative assessment of higher education efficiency. While the results should be interpreted within the acknowledged limitations, they provide a solid empirical basis for policy discussion and future research on performance, equity, and sustainability in European higher education systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Methodology, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Software, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Validation, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Formal analysis, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Investigation, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Resources, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Data curation, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Writing – original draft, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Writing – review & editing, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Visualization, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Supervision, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Project administration, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A.; Funding acquisition, I.-A.R., C.P., Ș.I.-O. and K.-A.A. All authors have made an equal and significant contribution to the development of this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data employed in this study are obtained from official sources and are fully described in Section 3 (Data and Methodology).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Efficiency Scores for Skills Matching

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Austria | 0.8343 | 0.6911 | 0.6746 | 0.6314 | 0.7538 | 0.7399 |

| Belgium | 0.8481 | 0.8009 | 0.8086 | 0.7791 | 0.8650 | 0.8562 |

| Bulgaria | 0.8143 | 0.6921 | 0.6863 | 0.7137 | 0.7565 | 0.7555 |

| Croatia | 0.8831 | 0.8124 | 0.7953 | 0.7938 | 0.9065 | 0.9055 |

| Cyprus | 0.6929 | 0.2387 | 0.3020 | 0.3659 | 0.8443 | 0.8344 |

| Czechia | 0.9602 | 0.9319 | 0.9363 | 0.9394 | 0.9425 | 0.9374 |

| Denmark | 0.8851 | 0.8571 | 0.8348 | 0.8403 | 0.8665 | 0.8554 |

| Estonia | 0.8627 | 0.7427 | 0.7665 | 0.8054 | 0.8131 | 0.7302 |

| Finland | 0.8826 | 0.8691 | 0.8338 | 0.8471 | 0.8806 | 0.8893 |

| France | 0.8284 | 0.6445 | 0.7133 | 0.6576 | 0.8149 | 0.8618 |

| Germany | 0.8747 | 0.7846 | 0.7910 | 0.7634 | 0.8055 | 0.8013 |

| Greece | 0.8155 | 0.4679 | 0.3596 | 0.3466 | 0.5127 | 0.5914 |

| Hungary | 0.8899 | 0.8517 | 0.8727 | 0.8807 | 0.7283 | 0.8769 |

| Ireland | 0.8630 | 0.3376 | 0.5698 | 0.7695 | 0.9120 | 0.9144 |

| Italy | 0.7374 | 0.6763 | 0.7053 | 0.6499 | 0.7231 | 0.7044 |

| Latvia | 0.9234 | 0.8429 | 0.8238 | 0.8212 | 0.7190 | 0.8688 |

| Lithuania | 0.9041 | 0.8102 | 0.8466 | 0.8173 | 0.8302 | 0.7646 |

| Luxembourg | 0.8955 | 0.8672 | 0.8474 | 0.8641 | 0.8650 | 0.8484 |

| Malta | 0.8369 | 0.8173 | 0.8150 | 0.7918 | 0.8144 | 0.8202 |

| Netherlands | 0.8495 | 0.6499 | 0.7687 | 0.7934 | 0.8600 | 0.8578 |

| Poland | 0.8893 | 0.7962 | 0.7987 | 0.7999 | 0.8484 | 0.8621 |

| Portugal | 0.7693 | 0.5664 | 0.5648 | 0.5839 | 0.7683 | 0.8138 |

| Romania | 0.9015 | 0.7882 | 0.7913 | 0.8294 | 0.8867 | 0.8779 |

| Slovakia | 0.8391 | 0.7850 | 0.7445 | 0.6782 | 0.7096 | 0.6918 |

| Slovenia | 0.8937 | 0.7253 | 0.7171 | 0.7146 | 0.8466 | 0.7916 |

| Spain | 0.2406 | 0.1016 | 0.1299 | 0.1468 | 0.1864 | 0.2090 |

| Sweden | 0.7371 | 0.6531 | 0.7086 | 0.6969 | 0.7421 | 0.7275 |

| Source: Own processing using results from SPSS version 25. | ||||||

Appendix B. Efficiency Scores for Published Articles

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Austria | 0.3422 | 0.3351 | 0.3363 | 0.3705 | 0.3904 | 0.3698 |

| Belgium | 0.7224 | 0.7288 | 0.7101 | 0.7425 | 0.7652 | 0.7542 |

| Bulgaria | 0.3782 | 0.4168 | 0.4676 | 0.5214 | 0.5377 | 0.5288 |

| Croatia | 0.5575 | 0.5650 | 0.5481 | 0.5923 | 0.6256 | 0.5869 |

| Cyprus | 0.7444 | 0.7464 | 0.7544 | 0.8120 | 0.8334 | 0.8447 |

| Czechia | 0.8936 | 0.8874 | 0.8919 | 0.8939 | 0.8969 | 0.8862 |

| Denmark | 0.6555 | 0.6569 | 0.6679 | 0.7185 | 0.7216 | 0.7248 |

| Estonia | 0.6787 | 0.6557 | 0.7332 | 0.7383 | 0.7824 | 0.7468 |

| Finland | 0.7999 | 0.7996 | 0.8038 | 0.8035 | 0.7837 | 0.8025 |

| France | 0.7825 | 0.7850 | 0.7753 | 0.7958 | 0.8028 | 0.7798 |

| Germany | 0.3983 | 0.3931 | 0.3698 | 0.3799 | 0.3908 | 0.3756 |

| Greece | 0.8727 | 0.8937 | 0.8717 | 0.9138 | 0.9015 | 0.8922 |

| Hungary | 0.5758 | 0.5578 | 0.5605 | 0.5989 | 0.5994 | 0.5955 |

| Ireland | 0.7999 | 0.8023 | 0.8472 | 0.8543 | 0.8656 | 0.7995 |

| Italy | 0.8857 | 0.8875 | 0.8920 | 0.9134 | 0.9130 | 0.9042 |

| Latvia | 0.4304 | 0.4043 | 0.4531 | 0.4681 | 0.4894 | 0.4879 |

| Lithuania | 0.3790 | 0.4037 | 0.4596 | 0.5259 | 0.4822 | 0.4844 |

| Luxembourg | 0.7796 | 0.6768 | 0.6982 | 0.6885 | 0.7091 | 0.7385 |

| Malta | 0.4582 | 0.4347 | 0.4266 | 0.4520 | 0.5030 | 0.4858 |

| Netherlands | 0.6348 | 0.6373 | 0.6355 | 0.6454 | 0.6570 | 0.6154 |

| Poland | 0.6833 | 0.6917 | 0.7192 | 0.7303 | 0.7431 | 0.7053 |

| Portugal | 0.7436 | 0.7452 | 0.7745 | 0.8117 | 0.8287 | 0.8057 |

| Romania | 0.8075 | 0.7996 | 0.8318 | 0.8292 | 0.8487 | 0.8437 |

| Slovakia | 0.7369 | 0.7148 | 0.7743 | 0.7827 | 0.7754 | 0.7584 |

| Slovenia | 0.7190 | 0.7196 | 0.7468 | 0.7587 | 0.7987 | 0.6879 |

| Spain | 0.5962 | 0.5937 | 0.6117 | 0.6806 | 0.6894 | 0.6495 |

| Sweden | 0.7408 | 0.7368 | 0.7324 | 0.7362 | 0.7400 | 0.7308 |

| Source: Own processing using results from SPSS version 25. | ||||||

Appendix C. Efficiency Scores for Graduates

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Austria | 0.8434 | 0.8407 | 0.8475 | 0.8603 | 0.8520 | 0.8348 |

| Belgium | 0.8717 | 0.8773 | 0.8709 | 0.8902 | 0.8807 | 0.8716 |

| Bulgaria | 0.9008 | 0.9022 | 0.8960 | 0.8783 | 0.8806 | 0.8853 |

| Croatia | 0.8774 | 0.8803 | 0.8826 | 0.8832 | 0.8842 | 0.8667 |

| Cyprus | 0.8639 | 0.8524 | 0.8696 | 0.8572 | 0.8990 | 0.9129 |

| Czechia | 0.9071 | 0.8925 | 0.8883 | 0.8835 | 0.8665 | 0.8570 |

| Denmark | 0.8992 | 0.8976 | 0.9003 | 0.8985 | 0.9036 | 0.8976 |

| Estonia | 0.8588 | 0.8511 | 0.8515 | 0.8572 | 0.8679 | 0.8479 |

| Finland | 0.8288 | 0.8395 | 0.8447 | 0.8635 | 0.8394 | 0.8242 |

| France | 0.9279 | 0.9265 | 0.9251 | 0.9282 | 0.9301 | 0.9278 |

| Germany | 0.8311 | 0.8241 | 0.8502 | 0.8283 | 0.8431 | 0.8365 |

| Greece | 0.5986 | 0.5862 | 0.5691 | 0.5522 | 0.6032 | 0.6044 |

| Hungary | 0.8870 | 0.8941 | 0.8889 | 0.9651 | 0.9007 | 0.8657 |

| Ireland | 0.9341 | 0.9377 | 0.9386 | 0.9409 | 0.9423 | 0.9403 |

| Italy | 0.8773 | 0.8765 | 0.8807 | 0.8883 | 0.8840 | 0.8824 |

| Latvia | 0.8374 | 0.8534 | 0.8449 | 0.8414 | 0.8459 | 0.8264 |

| Lithuania | 0.8908 | 0.8903 | 0.8900 | 0.8919 | 0.8879 | 0.8791 |

| Luxembourg | 0.8709 | 0.8725 | 0.8657 | 0.8740 | 0.8916 | 0.8930 |

| Malta | 0.9237 | 0.9042 | 0.9151 | 0.8999 | 0.9189 | 0.9120 |

| Netherlands | 0.8127 | 0.8140 | 0.8155 | 0.8052 | 0.8190 | 0.8195 |

| Poland | 0.9397 | 0.9348 | 0.9344 | 0.9283 | 0.9290 | 0.9269 |

| Portugal | 0.8883 | 0.8902 | 0.8869 | 0.8914 | 0.8913 | 0.8820 |

| Romania | 0.9003 | 0.9031 | 0.9010 | 0.9053 | 0.9021 | 0.8954 |

| Slovakia | 0.9341 | 0.9291 | 0.9212 | 0.9170 | 0.9167 | 0.9095 |

| Slovenia | 0.8644 | 0.8737 | 0.8662 | 0.8530 | 0.8522 | 0.8442 |

| Spain | 0.8882 | 0.8907 | 0.8863 | 0.8941 | 0.8990 | 0.8933 |

| Sweden | 0.7843 | 0.7922 | 0.7995 | 0.8142 | 0.8016 | 0.8146 |

| Source: Own processing using results from SPSS 25. | ||||||

Appendix D. Composite Efficiency Index Values Using Entropy Method

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Austria | 0.6448 | 0.5807 | 0.5774 | 0.5733 | 0.6365 | 0.6168 |

| Belgium | 0.8024 | 0.7876 | 0.7840 | 0.7816 | 0.8301 | 0.8130 |

| Bulgaria | 0.7593 | 0.7365 | 0.7323 | 0.7795 | 0.8013 | 0.7914 |

| Croatia | 0.7612 | 0.7216 | 0.7023 | 0.7204 | 0.7865 | 0.7712 |

| Cyprus | 0.7593 | 0.5634 | 0.5944 | 0.6445 | 0.8581 | 0.8613 |

| Czechia | 0.9181 | 0.8932 | 0.8965 | 0.8981 | 0.9028 | 0.8882 |

| Denmark | 0.7824 | 0.7704 | 0.7641 | 0.7838 | 0.8053 | 0.7834 |

| Estonia | 0.7444 | 0.6664 | 0.7212 | 0.7405 | 0.7649 | 0.7008 |

| Finland | 0.8281 | 0.8219 | 0.8100 | 0.8174 | 0.8324 | 0.8355 |

| France | 0.8039 | 0.7248 | 0.7500 | 0.7294 | 0.8023 | 0.8085 |

| Germany | 0.7163 | 0.6724 | 0.6649 | 0.6523 | 0.6830 | 0.6681 |

| Greece | 0.8235 | 0.6851 | 0.6238 | 0.6374 | 0.7133 | 0.7383 |

| Hungary | 0.7815 | 0.7564 | 0.7565 | 0.7864 | 0.7175 | 0.7804 |

| Ireland | 0.8524 | 0.6430 | 0.7532 | 0.8443 | 0.9137 | 0.9022 |

| Italy | 0.8193 | 0.7952 | 0.8111 | 0.7983 | 0.8313 | 0.8189 |

| Latvia | 0.6808 | 0.6143 | 0.6242 | 0.6335 | 0.6094 | 0.6561 |

| Lithuania | 0.6563 | 0.6229 | 0.6614 | 0.6688 | 0.6661 | 0.6280 |

| Luxembourg | 0.8384 | 0.8062 | 0.7990 | 0.7977 | 0.8127 | 0.8099 |

| Malta | 0.6939 | 0.6692 | 0.6556 | 0.6624 | 0.7074 | 0.7046 |

| Netherlands | 0.7907 | 0.7084 | 0.7551 | 0.7666 | 0.8024 | 0.7878 |

| Poland | 0.7814 | 0.7406 | 0.7364 | 0.7470 | 0.7741 | 0.7585 |

| Portugal | 0.7478 | 0.6657 | 0.6836 | 0.7114 | 0.8049 | 0.8179 |

| Romania | 0.8977 | 0.8499 | 0.8583 | 0.8782 | 0.9048 | 0.8967 |

| Slovakia | 0.8019 | 0.7708 | 0.7780 | 0.7428 | 0.7546 | 0.7241 |

| Slovenia | 0.8717 | 0.7917 | 0.7961 | 0.7970 | 0.8650 | 0.8111 |

| Spain | 0.5282 | 0.4707 | 0.4912 | 0.5188 | 0.5415 | 0.5354 |

| Sweden | 0.7486 | 0.7148 | 0.7434 | 0.7404 | 0.7618 | 0.7529 |

| Source: Own processing using results from SPSS version 25. | ||||||

Appendix E. Composite Efficiency Index Values Using PCA

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Austria | 0.7585 | 0.6977 | 0.6941 | 0.6875 | 0.7371 | 0.7207 |

| Belgium | 0.8379 | 0.8220 | 0.8194 | 0.8209 | 0.8556 | 0.8463 |

| Bulgaria | 0.7808 | 0.7378 | 0.7410 | 0.7533 | 0.7744 | 0.7746 |

| Croatia | 0.8279 | 0.8015 | 0.7928 | 0.7996 | 0.8514 | 0.8372 |

| Cyprus | 0.7747 | 0.5846 | 0.6192 | 0.6492 | 0.8660 | 0.8698 |

| Czechia | 0.9266 | 0.9078 | 0.9085 | 0.9080 | 0.9025 | 0.8946 |

| Denmark | 0.8540 | 0.8421 | 0.8359 | 0.8456 | 0.8590 | 0.8524 |

| Estonia | 0.8312 | 0.7752 | 0.7976 | 0.8168 | 0.8317 | 0.7835 |

| Finland | 0.8461 | 0.8451 | 0.8336 | 0.8471 | 0.8472 | 0.8473 |

| France | 0.8637 | 0.7884 | 0.8144 | 0.7963 | 0.8624 | 0.8769 |

| Germany | 0.7788 | 0.7382 | 0.7482 | 0.7291 | 0.7545 | 0.7475 |

| Greece | 0.7316 | 0.5877 | 0.5325 | 0.5268 | 0.6145 | 0.6457 |

| Hungary | 0.8378 | 0.8223 | 0.8290 | 0.8713 | 0.7815 | 0.8265 |

| Ireland | 0.8833 | 0.6707 | 0.7732 | 0.8569 | 0.9175 | 0.9069 |

| Italy | 0.8216 | 0.7965 | 0.8109 | 0.7950 | 0.8230 | 0.8132 |

| Latvia | 0.8066 | 0.7764 | 0.7728 | 0.7727 | 0.7363 | 0.7889 |

| Lithuania | 0.8133 | 0.7788 | 0.8026 | 0.8022 | 0.7986 | 0.7684 |

| Luxembourg | 0.8662 | 0.8387 | 0.8311 | 0.8399 | 0.8512 | 0.8498 |

| Malta | 0.8128 | 0.7927 | 0.7951 | 0.7832 | 0.8089 | 0.8055 |

| Netherlands | 0.7989 | 0.7184 | 0.7672 | 0.7745 | 0.8095 | 0.8021 |

| Poland | 0.8776 | 0.8388 | 0.8441 | 0.8438 | 0.8660 | 0.8645 |

| Portugal | 0.8163 | 0.7345 | 0.7372 | 0.7529 | 0.8309 | 0.8418 |

| Romania | 0.8857 | 0.8394 | 0.8450 | 0.8620 | 0.8872 | 0.8799 |

| Slovakia | 0.8634 | 0.8356 | 0.8253 | 0.7977 | 0.8093 | 0.7961 |

| Slovenia | 0.8528 | 0.7882 | 0.7860 | 0.7812 | 0.8412 | 0.7974 |

| Spain | 0.5764 | 0.5203 | 0.5330 | 0.5544 | 0.5741 | 0.5744 |

| Sweden | 0.7580 | 0.7264 | 0.7515 | 0.7537 | 0.7673 | 0.7655 |

| Source: Own processing using results from SPSS version 25. | ||||||

References

- Jain, I.; Gulati, R. Efficiency in Higher Education: A Review of Research From 1977 to 2022. High. Educ. Q. 2025, 79, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallee, J.M.; Resch, A.M.; Courant, P.N. On the Optimal Allocation of Students and Resources in a System of Higher Education. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2008, 8, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzouita, A.; Kooli, I. Evaluating the performance of Tunisian higher Institutes of Technological Studies (ISETs) using a stochastic frontier analysis. Eval. Program Plan. 2024, 107, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, C.T.T.D.; Tran, J.N.N.B. Government financial assistance in higher education: An empirical analysis of efficiency in Australian universities. Int. J. Educ. Econ. Dev. 2025, 16, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T. A Multiobjective Allocation Method for High-Quality Higher Education Resources Based on Cellular Genetic Algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4322078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. The Linear Programming Model of the Optimization Configuration of Education Resource Optimization for Higher Vocational Students. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 9, 20243498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ušpurienė, A.; Sakalauskas, L.; Dumskis, V. Financial Resource Allocation in Higher Education. Inform. Educ. 2017, 16, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimčisko, J. Determinanty Produkcie Znalostí Na Európskych Univerzitách. Ekon. A Spoločnosť 2025, 26, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenna, R.; Berche, B. Managing Research Quality: Critical Mass and Optimal Academic Research Group Size. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2012, 23, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]