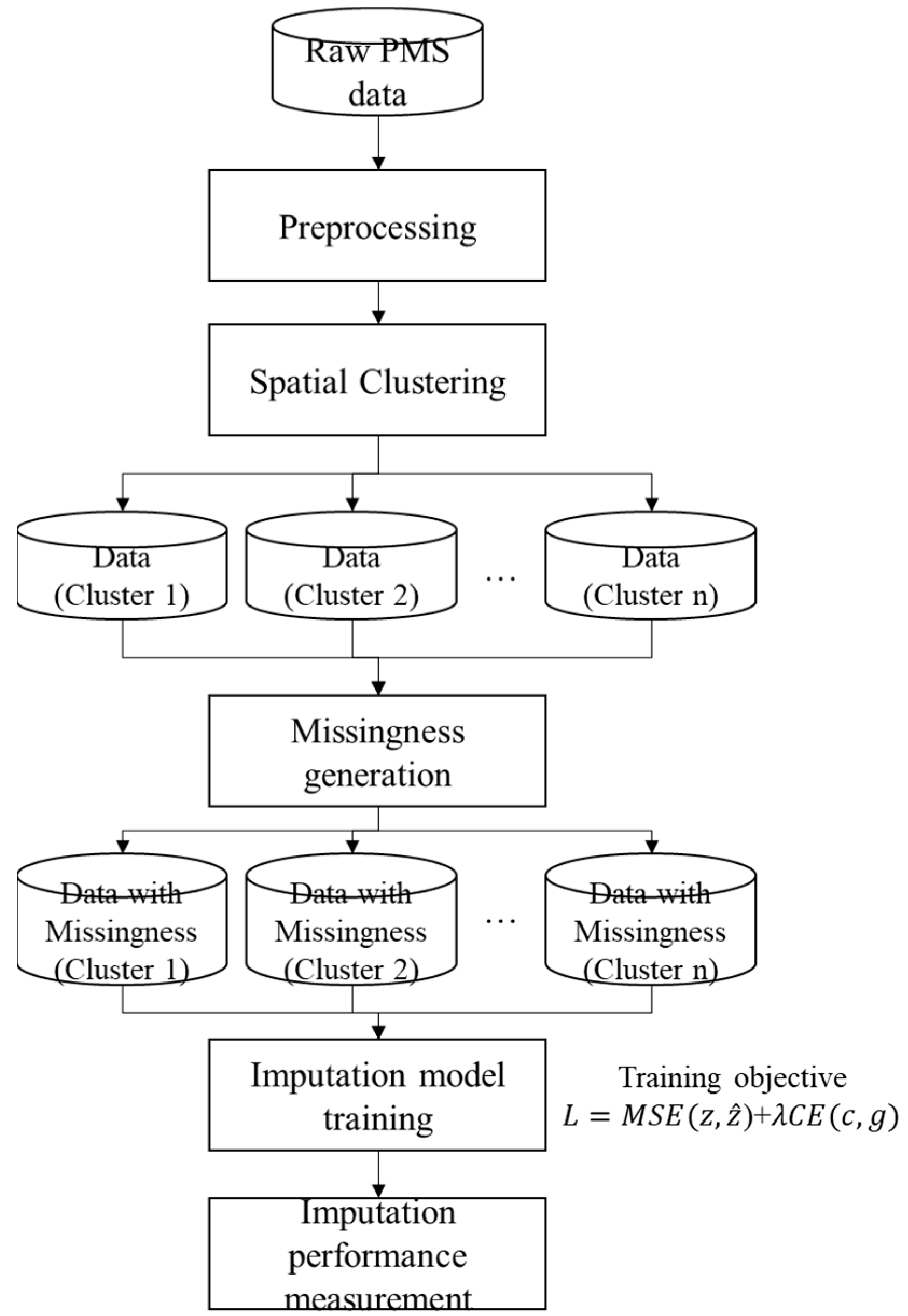

4.2. Experimental Setting

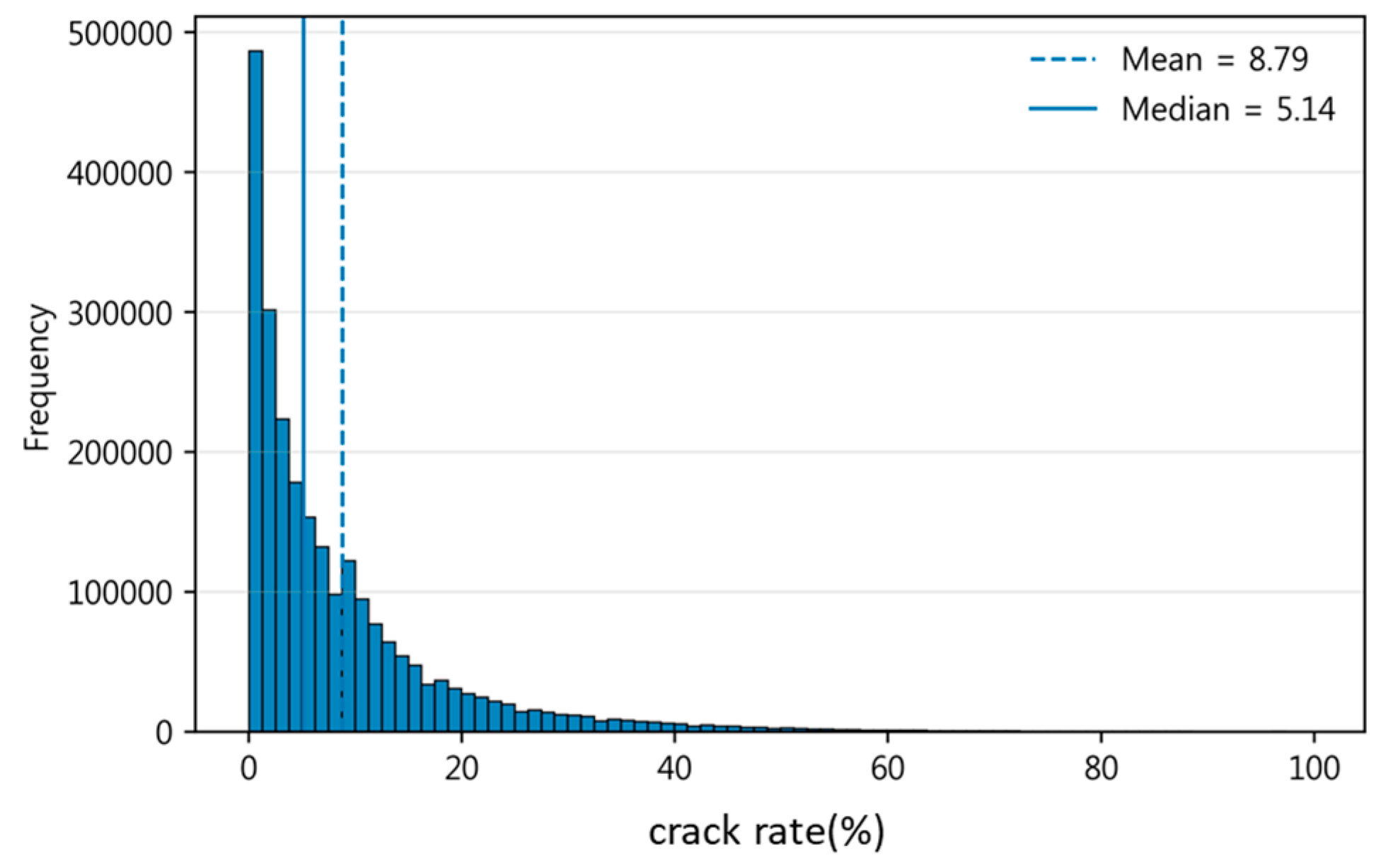

We designed experiments to evaluate the imputation of missing crack rate values under three different missing data mechanisms (

Table 2). In each case, a portion of the crack rate entries in the dataset was artificially removed (treated as missing), and models were tasked with predicting these missing values using the remaining features. The three missingness scenarios were as follows: (1) MCAR, where crack rate values are Missing Completely at Random (i.e., removed uniformly across all road sections, independent of any feature); (2) MAR_intensity, a Missing At Random mechanism in which the probability of a value being missing is influenced by an observed feature, in this case, the “patching intensity” (segments with higher patching area were more likely to have their crack rate omitted, reflecting a scenario where data might be preferentially missing for sections with certain observed characteristics); and (3) MNAR, a Missing Not At Random scenario where missingness depends on the true value of the crack rate itself (specifically, sections with more severe cracking were more likely to have their crack rate value missing). This MNAR setting is particularly challenging, as the missing entries are biased toward the highest crack rates, the very values that are extreme and potentially hardest to predict. For each mechanism, we tested three levels of missingness: 10%, 30%, and 50% of the crack rate values removed. For the MNAR mechanism, we modeled the missingness probability as a logistic function of the crack severity,

, where

is the standardized logit of the crack-rate, and

is the sigmoid function. Then draw M~Bernoulli (p) to select missing entries. This yields a principled value-dependent mechanism in which high-severity segments are more likely to be missing. This design reflects practical settings where severely distressed sections may be underreported due to occlusions, sensor saturation, or safety constraints during inspection. These correspond to mild, moderate, and severe missing data fractions, respectively. The missing entries were selected using five different random seeds for each scenario and missing rate to ensure that results are not an artifact of a particular random draw. In the MCAR case, each seed produces a different random selection of 10%, 30%, or 50% of the data to mask. For MAR_intensity and MNAR, the overall fraction (e.g., 30%) remains fixed, but the specific segments removed can vary slightly with each seed due to random tie-breaking or probabilistic selection (e.g., using a weighted probability based on patching for MAR, or removing the top X% of crack values with some randomization if needed).

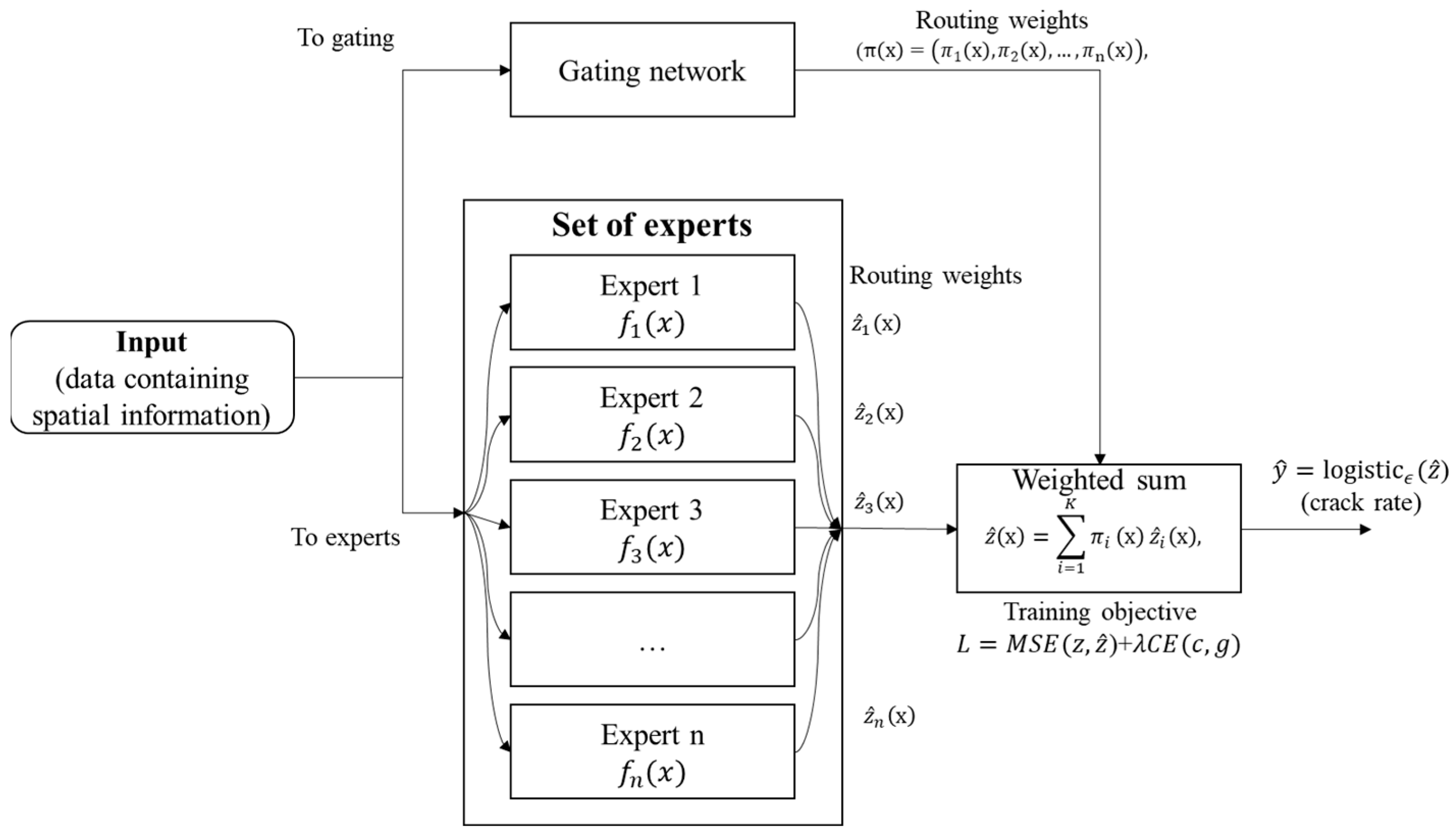

Two modeling approaches were employed to perform the imputation of missing crack rates: (i) the proposed SG-MoE model, and (ii) a baseline single-model imputer using LightGBM. The SG-MoE consists of multiple expert models (in this implementation, each expert is a LightGBM regression model) and a gating network that assigns weights to each expert’s prediction for a given data instance. The gating network is conditioned on spatial features (such as the coordinates or region of the road segment), allowing the model to adaptively select which expert(s) are most relevant for a particular location. In essence, each expert can specialize in modeling crack rates for a certain sub-region or distribution of the data, while the gating mechanism learns to weight experts based on the segment’s location. The baseline Single LightGBM model, on the other hand, uses a single gradient-boosted decision tree ensemble to learn a mapping from all available input features to the crack rate. This single model does not incorporate any explicit mechanism for regional specialization; it treats the dataset as a whole. Both models were trained using the incomplete dataset (with known crack rate values as training targets and excluding the held-out missing targets). We ensured that the models were not given access to the true missing crack rate values during training, those were reserved for evaluating imputation performance. Training hyperparameters for LightGBM (such as number of trees, learning rate, etc.) were kept consistent between the single model and the experts in the MoE to ensure a fair comparison. Model performance was evaluated on the held-out missing entries by comparing the imputed values against the ground-truth crack rates that were originally removed. We report standard error metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (sMAPE), all computed between the imputed and true crack rate values. Each metric was averaged over the five random runs for robustness. In all scenarios, the standard deviation of these metrics across the five runs was found to be very small (often on the order of 0.001), indicating that the experimental results are stable and not sensitive to the particular random seed. Next, we present a comparative evaluation of the two models under each scenario and discuss the observed trends as the missing rate varies.

Also, we include an error-weighted ensemble baseline. A static weighted average of expert predictions where weights are inversely proportional to each expert’s validation error (e.g., inverse RMSE), estimated on a held-out validation split. This provides a performance-based weighting competitor to the learned gating function. In addition to the single global LightGBM baseline, we include three stronger comparators to isolate the effect of spatial gating: (i) Hard cluster-wise LightGBM (Hard-Cluster): we train one LightGBM per spatial cluster and assign each segment to its cluster expert deterministically; (ii) Single LightGBM + spatial features (Single + Spatial): a single LightGBM augmented with latitude/longitude and cluster-ID features; and (iii) MoE without spatial-supervision loss (MoE-noCE): the same MoE architecture but trained without the auxiliary cross-entropy loss that aligns gate outputs to spatial clusters. We also assess robustness to the number of experts (K) by repeating experiments for K ∈ {3, 5, 8, 10}.

The experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-12900K CPU, 128 GB of RAM, and a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB VRAM). All code was executed on Ubuntu 22.04 with Python 3.10.6. The following software libraries and frameworks were used throughout the study: LightGBM 3.3.2 for tree-based models, PyTorch 1.13.1 and Torchvision 0.14.1 for deep learning architectures, and Scikit-learn 1.2.2 for preprocessing and metrics. To ensure reproducibility, random seeds were fixed across all training runs, and consistent data splits were maintained for training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) across models. Early stopping was employed with a patience threshold of 5 epochs, monitored on the validation loss. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using grid search within predefined ranges, with selections made based on validation performance. This unified protocol was applied consistently to the proposed SG-MoE model and all baselines to ensure a fair and rigorous comparison.

4.3. Result

To make the contribution of spatially supervised gating testable, we analyze performance stratified by a proxy for spatial heterogeneity. Specifically, we compute within-cluster variance of the crack-rate target and group clusters into low and high heterogeneity regimes. We then report imputation error for each regime and the corresponding relative improvement of SG-MoE over global baselines. This analysis clarifies that spatial gating is most beneficial when regional relationships between covariates and crack progression differ substantially across space (high heterogeneity), whereas gains are expected to be smaller when the system is approximately spatially stationary (low heterogeneity).

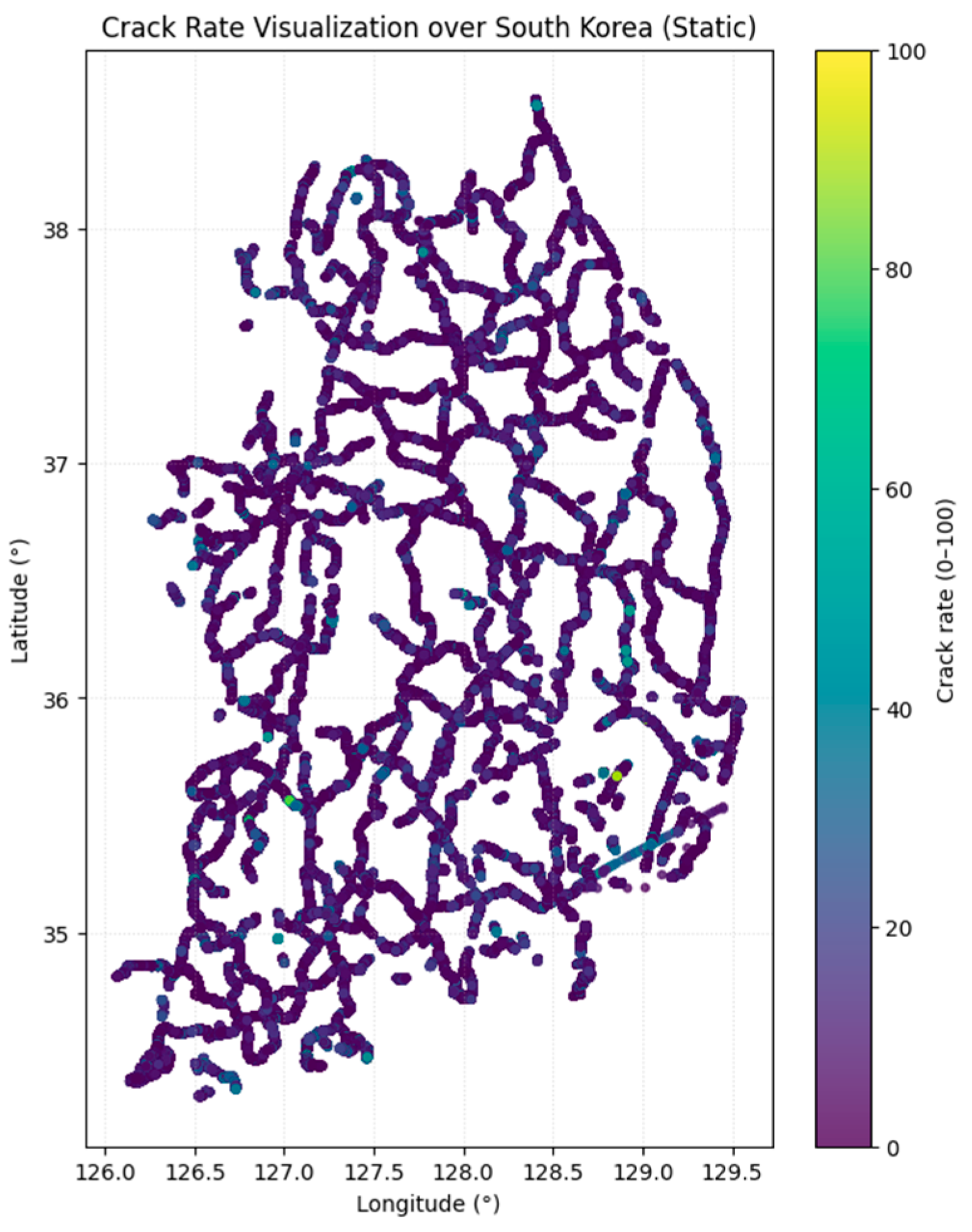

The proposed SG-MoE is first supported by the spatial clustering outcome that defines its region-specific experts.

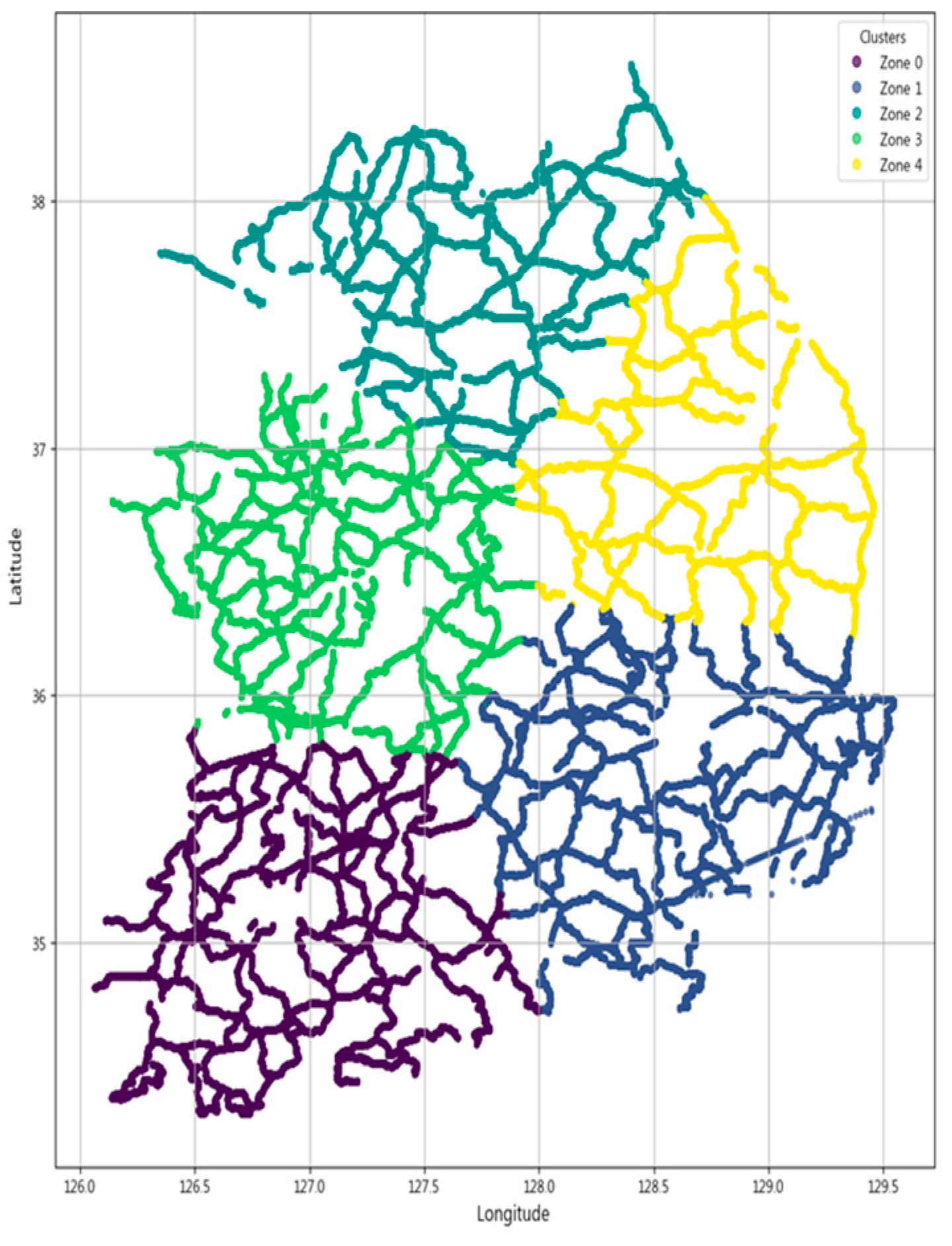

Figure 5 depicts the partitioning of the national road network into five spatially coherent zones obtained by applying spatial clustering to the latitude and longitude coordinates of all road segments. This zoning reduces intra cluster heterogeneity in pavement conditions and deterioration patterns and serves as the structural basis for assigning observations to experts in the SG-MoE, thereby enabling the gating mechanism to exploit large-scale spatial structure.

Building on this partition, we next examine whether the gating mechanism behaves in a spatially structured manner consistent with the intended design.

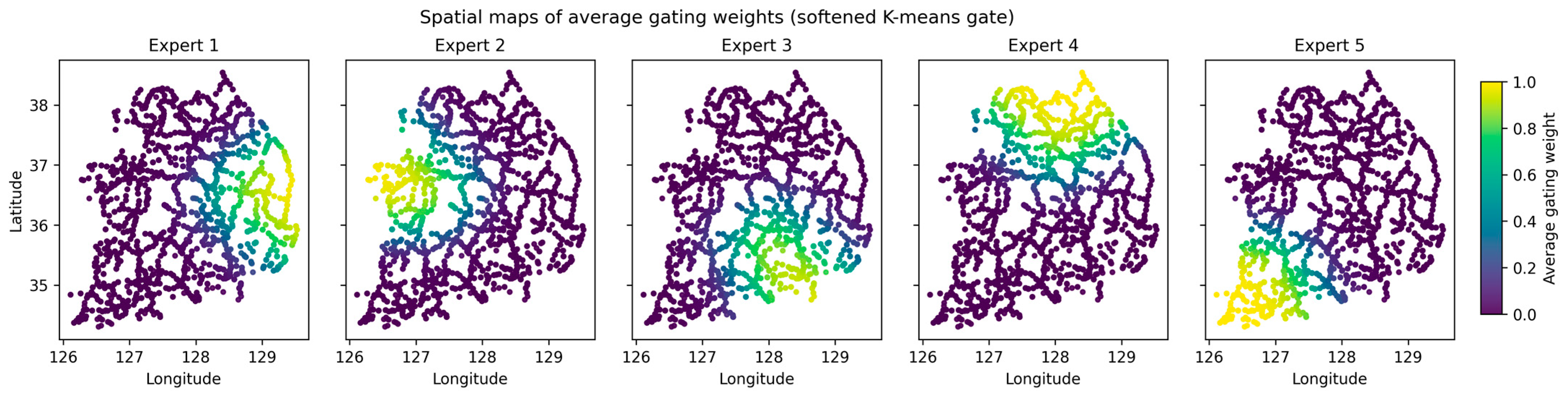

Figure 6 visualizes spatial maps of the average gating weights for the five experts, where each road segment is colored by the mean weight assigned to a given expert. The maps indicate that expert contributions are geographically localized, while weights vary smoothly near zone transitions, consistent with soft mixing in boundary areas. Because K-means yields hard zone assignments, we compute a distance-based softmax over zone centers solely for visualization to highlight gradual transitions. Importantly,

Figure 6 provides an interpretable link between the zoning in

Figure 5 and the regime-based performance analysis above. In zones with higher within-zone target variance, the gating patterns tend to be less deterministic and exhibit smoother transitions, aligning with the hypothesis that spatially supervised gating yields larger benefits under spatial non-stationarity. Conversely, in relatively homogeneous zones, the gating weights are more concentrated, consistent with smaller expected gains when spatial stationarity approximately holds.

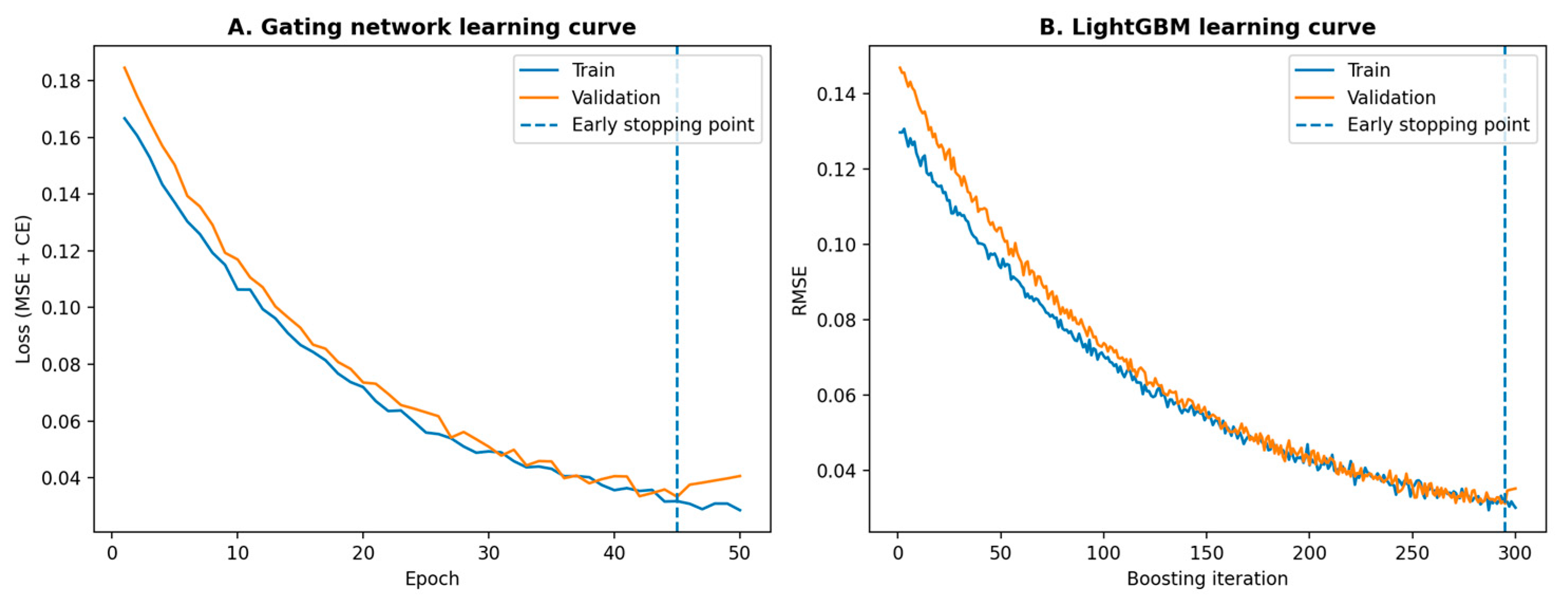

To verify that the proposed learning-based model is trained and validated appropriately, we report training and validation convergence diagnostics. In

Figure 7, learning curves of the gating network across epochs, decomposed into the prediction loss and the cross-entropy supervision term, and LightGBM learning curves showing training and validation loss over boosting iterations for the global baseline and representative experts. These results illustrate the optimization behavior and facilitate assessment of generalization by comparing training and validation trajectories.

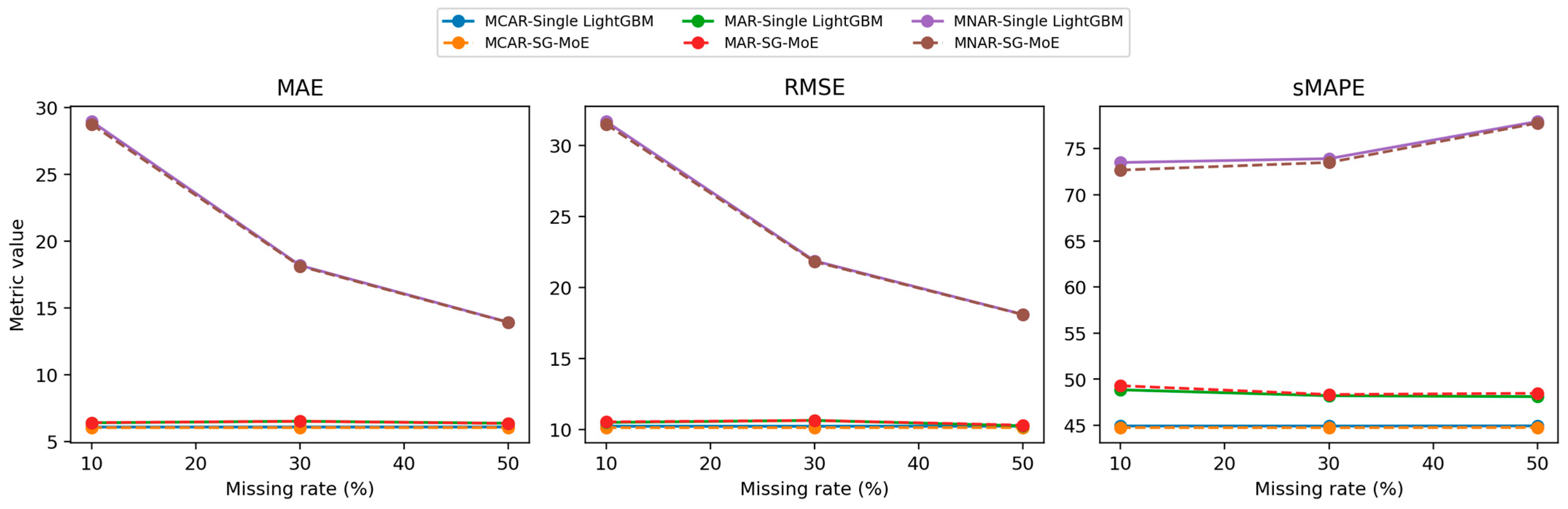

The imputation performance of the SG-MoE is then compared with that of a baseline single LightGBM model under three missing-data mechanisms (MCAR, MAR, and MNAR), each evaluated at missing rates of 10%, 30%, and 50%.

Table 3 and

Table 4 report the mean and standard deviation of MAE, RMSE, and sMAPE over five independent runs for each scenario and missing-rate combination. As shown in

Figure 8, both models achieve closely comparable accuracy. Differences in the error metrics are mostly within 0.1–1.0 percentage points and are accompanied by very small standard deviations, indicating high numerical stability. Nonetheless, consistent, albeit modest, gains of the SG-MoE over the baseline are observed in several settings, particularly under MCAR and MNAR.

In the MCAR scenario, where data are missing uniformly at random, the proposed SG-MoE model demonstrates consistently superior imputation accuracy compared to the single baseline. At a 10% missing rate, the MoE achieves a mean MAE of 6.02 ± 0.01, slightly lower than the baseline’s 6.07 ± 0.01. It also attains a marginally lower RMSE (10.14 vs. 10.24) and sMAPE (44.76% vs. 44.93%), indicating a small yet consistent advantage. Notably, increasing the missing fraction to 30% and 50% does not significantly degrade performance for either model, both MAE and sMAPE remain nearly unchanged (approximately 6.02–6.08 MAE and 44.7–44.9% sMAPE) across these levels. The MoE maintains its edge at each missing rate, albeit the differences are modest. The minimal variation across five runs (e.g., sMAPE standard deviation ~0.005) further confirms the stability of MoE’s performance and underscores its robustness to random missingness.

Under the MAR scenario, which missingness correlated with an observed intensity feature, both models achieve very similar performance, with the MoE matching the baseline and even providing slight improvements in certain metrics. For example, at 50% missing data the baseline attains sMAPE = 48.12% ± 0.02 versus 48.48% ± 0.05 for the MoE, a difference of only 0.36 percentage points. The baseline’s RMSE is marginally lower in this case (10.27 vs. 10.32), while the MoE yields a slightly better MAE (6.339 vs. 6.351), highlighting that their absolute errors are virtually on par. Across all missing rates (10%, 30%, 50%), the error levels for the two models remain in a narrow band: MAE stays around 6.34–6.50 and sMAPE around 48.1–49.3%. The tiny gaps observed (often <0.5% in sMAPE) fall within the run-to-run variability (sMAPE std ~0.03–0.05), indicating no statistically significant performance difference between MoE and the baseline under MAR. Thus, even in this scenario where the baseline performs essentially equivalently, the MoE maintains competitive accuracy while retaining the benefits of enhanced spatial generalization and model interpretability.

The MoE model’s advantage is most pronounced in the MNAR scenario, where missingness depends on the target yield value (a particularly challenging case). With only 10% of data missing, concentrated among the highest-yield instances, the baseline exhibits a very high error (MAE 28.96, sMAPE 73.50% ± 0.02). In contrast, the MoE effectively reduces the error to MAE 28.74 and sMAPE 72.68% ± 0.004, achieving an improvement of about 0.8 percentage points in sMAPE (roughly 1.1% relative reduction). This superior performance persists at higher missing rates. At 30% missing, the MoE attains sMAPE 73.51% vs. 73.92% for the baseline, and at 50% missing 77.77% vs. 77.95%. Although the gap narrows as the missing fraction increases, since the baseline also improves when more moderate-yield values are missing, the MoE still consistently yields lower errors in all metrics.

Interestingly, both models show a decrease in absolute error as the missing proportion grows in the MNAR scenario. The baseline’s MAE, for instance, drops from 28.96 at 10% missing to 13.92 at 50% missing, implying that the initially missing data, likely the most extreme yield values, were the hardest to impute. Despite this overall reduction in error with increasing missingness, the MoE remains ahead of the baseline at each level, demonstrating its ability to better handle these difficult, non-random missing cases. Furthermore, the MoE’s results are highly stable across random seeds. For example, its sMAPE varies by only 0.004 in the 10% missing scenario, substantially less variability than the baseline which is around 0.015. This high consistency under MNAR highlights the reliability of the MoE model, as well as its capacity to capture extreme yield patterns via specialized experts that a single model might miss.

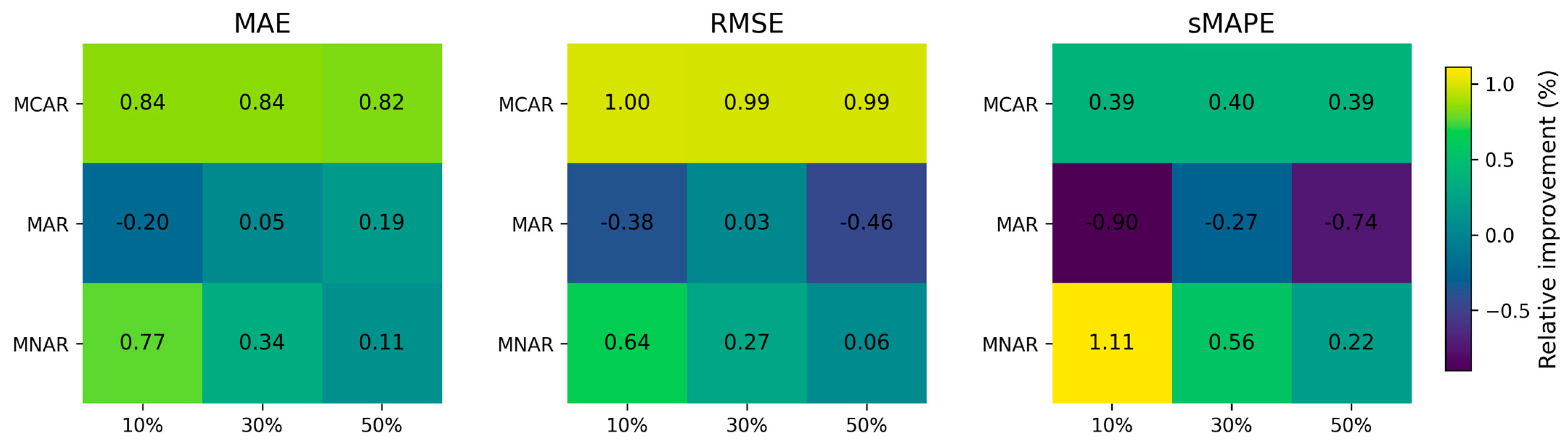

Figure 9 summarizes the relative improvement (RI, %) of SG-MoE over the single LightGBM baseline across missingness mechanisms (MCAR, MAR, MNAR) and missing rates (10/30/50%). We compute RI as

so positive values indicate error reduction (performance gains), whereas negative values indicate degradation relative to the baseline.

Overall, SG-MoE exhibits consistent gains under MCAR and MNAR across all metrics, with the largest improvements typically observed at lower missing rates (e.g., MNAR at 10% missing). This pattern suggests that the mixture-of-experts mechanism is particularly effective when the model can still leverage sufficient observed information to select and combine experts in a scenario-adaptive manner. As the missing rate increases toward 50%, the magnitude of RI tends to diminish, especially under MNAR, which is expected because severe missingness reduces the effective information content available to both the experts and the gating network.

In contrast, the MAR setting shows mixed behavior, with some cells indicating small gains and others slight degradation depending on the metric and missing rate. This observation implies that when missingness is systematically related to observed covariates, a strong single model (LightGBM) may already capture much of the structure, and the additional flexibility of expert combination provides more limited marginal benefit. These results motivate the subsequent statistical testing to confirm whether the observed differences are robust across repeated runs.

Table 4 reports the statistical significance of performance differences between SG-MoE and the LightGBM baseline using Welch’s t-test over five independent runs (n = 5). Here, Δ(MoE − Base) denotes the mean difference in the metric value across runs; therefore, for error-type metrics (MAE, RMSE, sMAPE), negative Δ indicates that SG-MoE achieves lower error than the baseline, while positive Δ indicates higher error.

Consistent with

Figure 9, SG-MoE shows statistically significant improvements in most MCAR and MNAR conditions: for MCAR (10–50%), Δ is negative across MAE, RMSE, and sMAPE with small

p-values, indicating that the gains are not attributable to run-to-run noise. Similarly, for MNAR, SG-MoE yields negative Δ values across all missing rates and metrics, with highly significant

p-values, supporting the claim that SG-MoE is particularly robust under non-random missingness.

For MAR, the results are more nuanced. Although some MAR conditions show statistically significant differences, the direction of Δ is not uniformly favorable to SG-MoE across all metrics and missing rates yields positive Δ values, while MAR at 30–50% shows mixed signs depending on the metric). This indicates that, under MAR, the advantage of SG-MoE is scenario- and metric-dependent, and improvements may be concentrated in specific metrics rather than consistently across MAE and RMSE. Accordingly, we temper the conclusions for MAR and emphasize that SG-MoE’s most reliable benefits occur under MCAR and MNAR, where the model’s expert-selection mechanism yields stable error reductions.

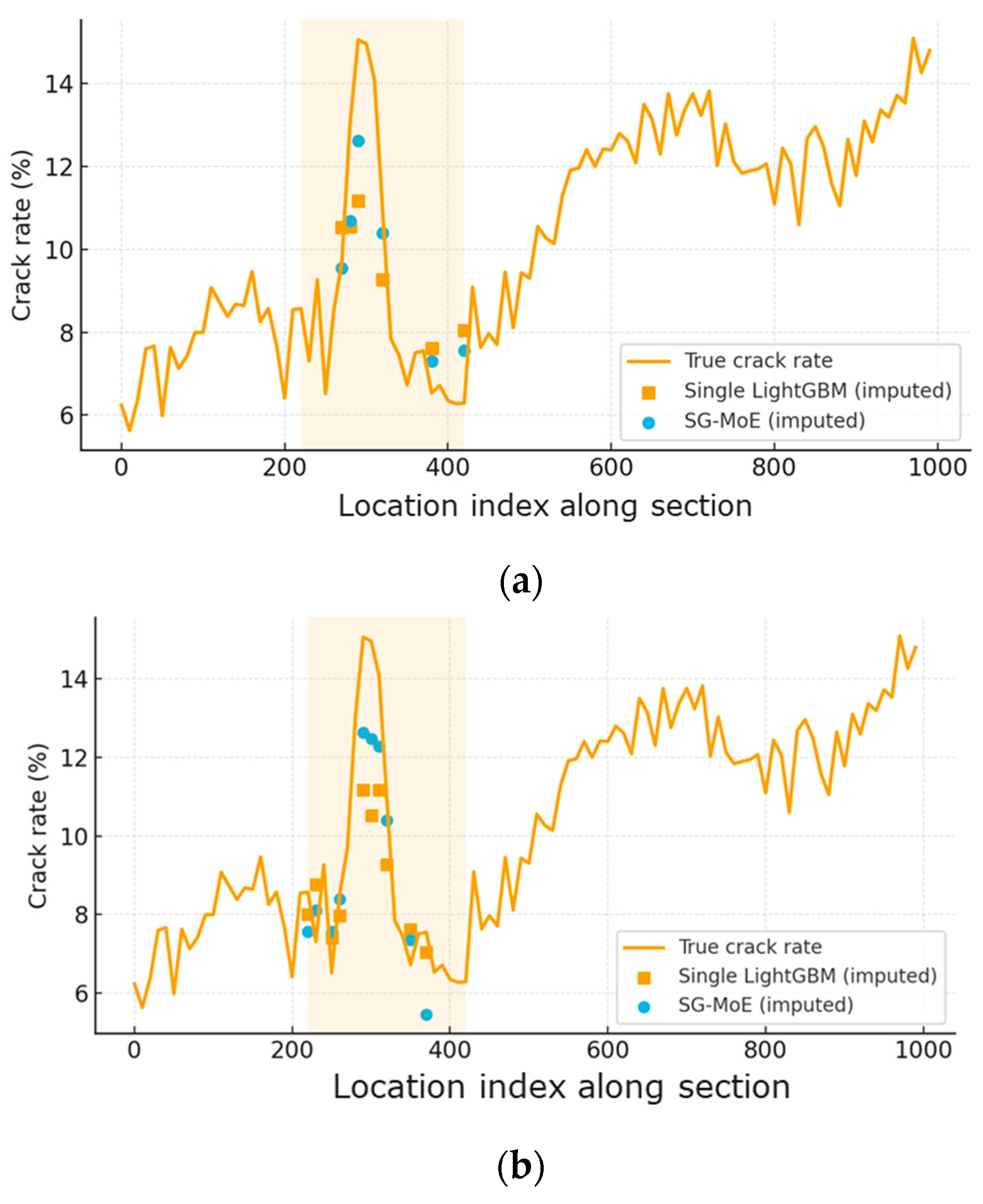

Figure 10 illustrates the behavior of the two imputation models when a substantial proportion of high-severity crack-rate observations is removed under the MNAR mechanism. Along the ordered observation points of the section, the SG-MoE imputations follow the ground-truth crack-rate profile more closely than those of the Single LightGBM, particularly around the peak deterioration within the shaded part of the section. As the missing rate increases from 30% to 50%, the baseline model exhibits increasing underestimation of the peak values, whereas the SG-MoE still reproduces the overall level and shape of the deterioration more accurately. These qualitative patterns are consistent with the quantitative error reductions reported in the aggregate evaluation results.

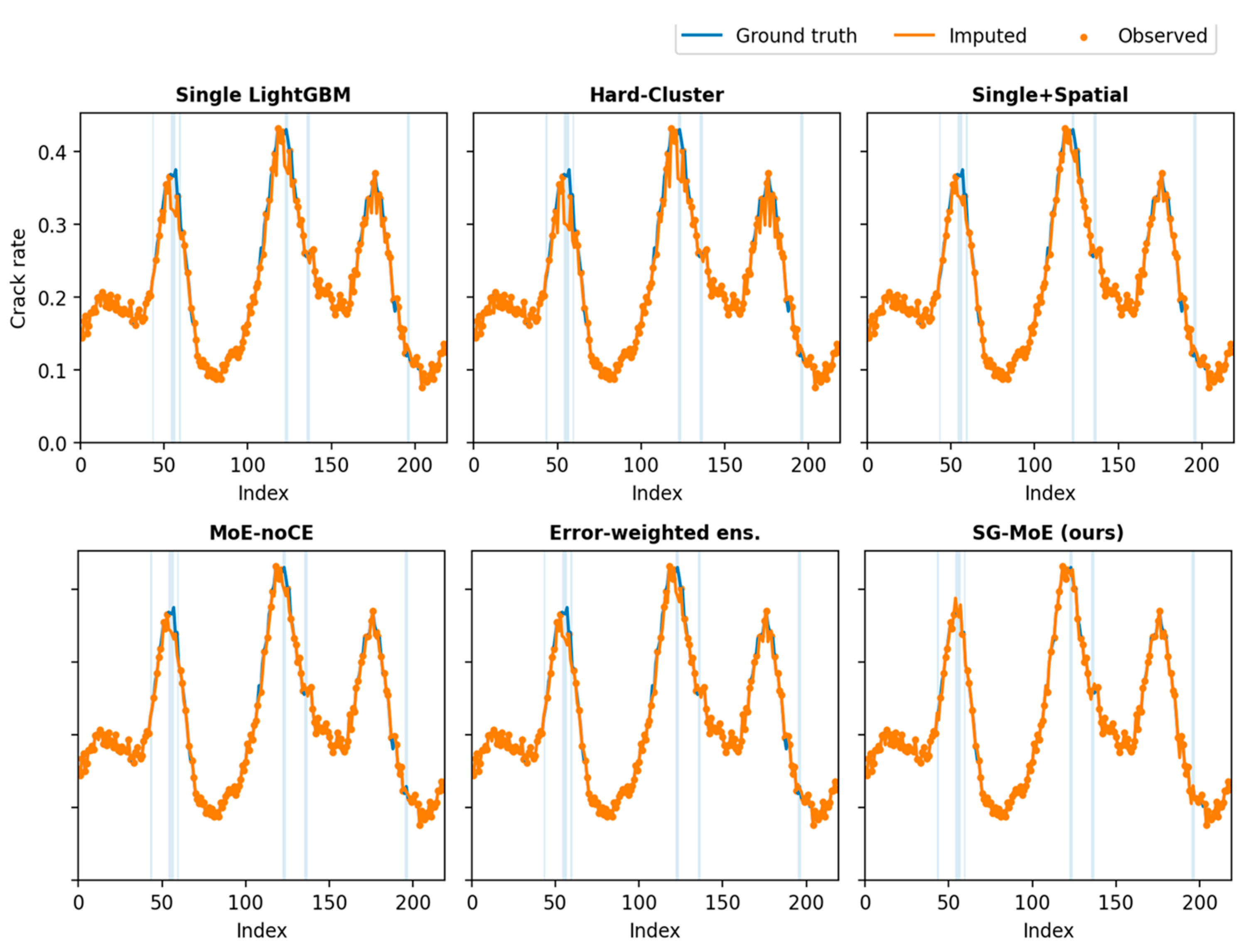

Figure 11 presents representative qualitative results on the test set under the MNAR setting, where missing entries are concentrated around high crack-rate segments. The shaded intervals indicate missing targets, and the curves compare each model’s imputed values against the ground truth. Overall, the single global LightGBM baseline tends to smooth sharp variations and underestimates peak regions, which is consistent with the selection bias induced by MNAR missingness. The hard-cluster variant further amplifies this oversmoothing effect by enforcing rigid spatial partitioning, whereas the Single + Spatial model provides modest improvement by incorporating spatial cues but still struggles to recover abrupt peak transitions. The MoE-noCE ablation yields closer reconstructions than the global baseline, yet it exhibits occasional attenuation around high-severity peaks, suggesting that gating specialization is not sufficiently constrained without explicit supervision. In contrast, SG-MoE produces imputations that more closely track the ground truth within missing intervals and better preserve local peak magnitudes and shapes, indicating improved generalization to severely deteriorated segments. These visual comparisons complement the quantitative results and provide additional evidence that the proposed spatially supervised gating facilitates expert specialization in a practically meaningful manner.

Overall, the Spatially Gated MoE exhibits robust and superior performance across all three missing-data scenarios. It consistently matches or outperforms the single-model baseline, with particularly notable gains in the more challenging MCAR and MNAR cases (especially in lowering sMAPE error). In situations where the baseline performs similarly (e.g., MAR), differences are negligible and within statistical uncertainty, meaning MoE achieves comparable accuracy without any trade-off. In addition to these quantitative improvements, the MoE offers qualitative advantages: its gating network partitions the task among region-specific experts, enhancing spatial generalization and providing interpretability by revealing spatial patterns in the imputation process. The combination of lower errors, statistical stability across runs, and interpretability underscores that the proposed Spatially Gated MoE is a more robust and effective solution for yield data imputation than the conventional single-model approach.