Abstract

In today’s volatile business environment, securing a sustainable competitive advantage hinges on retaining and effectively managing talent. While talent turnover is inevitable, strategic internal human resource (HR) transfers offer a solution to prevent talent outflow and supplement skill gaps. However, previous models for identifying internal substitutes often focus solely on individual work capabilities, neglecting the critical role of group interactions and collaborative structure. Drawing on social network theory, transactive memory systems, and person–group fit, this study proposes a graph-based analytical approach that models the organization as a complex system. Our methodology provides a holistic framework that integrates both (1) individual capabilities and (2) group-level characteristics (e.g., work-relationship networks and cluster-level similarity) to identify the most suitable substitutes. At the macroscopic level, we use an inductive graph neural network (GraphSAGE) to learn node embeddings from a work relationship network constructed from process event logs and to quantify group-level similarity. At the microscopic level, we compute dynamic collaboration intensity, frequency, and task similarity between employees over time. To validate the approach, we develop four simulation scenarios using an enriched incident management process event log and implement them in a SimPy-based simulator, benchmarking against an existing method that considers only individual factors. Across all scenarios, the proposed dual-factor model significantly outperforms the baseline in terms of efficiency, accuracy, and suitability. This research provides a practical, validated algorithm that supports evidence-based workforce management and more effective internal talent allocation.

1. Introduction

The technological environment is rapidly changing due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and, as a result, the business environment is also in the midst of change [1,2,3]. As a result, companies are experiencing difficulties in achieving sustainable growth and securing competitive advantage. Banmairuroy, Kritjaroen, and Homsombat (2022) argued that in this environment, securing and retaining excellent talents is more important than anything else in order to secure a sustainable competitive advantage [4].

However, the departure of talent is an inevitable phenomenon due to various reasons (e.g., compensation, industrial transition, demographic change), and organizations need to predict and prepare for this [5,6,7,8]. Human resource analytics can enhance organizational performance by providing data-driven insights for talent retention and predictive planning during crises [9,10]. The prevention of operational disruption caused by turnover can be addressed from a business process perspective, for instance, through process simulation that incorporates multitasking and resource-availability constraints [11,12]. Business Process (BP) innovation is an essential element for strengthening corporate competitiveness and sustainable growth by maximizing organizational efficiency and providing a foundation for agile response to changing market demands [11,13]. In particular, the role of human resources is paramount in BP innovation, and effective human resource management and talent development are pivotal drivers of innovation and long-term competitiveness [4,10,13].

Many companies currently struggle to secure excellent talent in a labor market shaped by digitalization, population ageing, and the future of work [3,8]. While global companies adopt ‘open innovation’ strategies to utilize external ideas and talent [2,14,15,16], there are practical limitations to recruiting external talent, including fierce competition, rising costs, and time constraints [14,15]. Therefore, internal transfers offer a strategic alternative to supplement manpower and prevent the outflow of tacit knowledge [14,15]. Internal human resource development and circulation can redistribute knowledge, strengthen technical capabilities, and contribute to organizational-culture innovation [4,10,13].

However, previous models for identifying internal substitutes often focus solely on individual work capabilities (human capital), neglecting the critical role of social structures (social capital). According to social network theory, organizational performance is deeply embedded in the web of interpersonal ties; an employee is not just a unit of labor but a node in a complex network of information flow and trust [17]. Furthermore, the loss of an employee disrupts the group’s transactive memory system (TMS)—the shared awareness of “who knows what” within a team [18]. A substitute selected purely on technical skills may fail if they cannot integrate into the group’s existing cognitive and collaborative structure or replicate the absent employee’s structural position in the network, such as their structural equivalence with other actors [19].

This study addresses this gap by proposing a novel graph-based analytical approach that models the organization as a complex system. Our methodology provides a holistic framework integrating both (1) individual capabilities (Microscopic) and (2) group-level dynamics (Macroscopic) to identify the most suitable substitutes. We draw on person–group (P–G) fit theory to operationalize the compatibility between the substitute and the target team, emphasizing both supplementary and complementary fit [20]. Unlike static analysis methods, we employ an inductive graph neural network (GraphSAGE) to capture the evolving nature of collaborative structures and to learn embeddings that generalize to previously unseen nodes and teams [21]. We posit that this dual-factor model demonstrates greater validity than models considering only individual factors.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Methods to Select Substitute Human Resources

Absenteeism significantly impacts an organization’s performance and profitability; this is traditionally seen as a human resource management issue [22,23]. Managing absenteeism is crucial for strategic HRM, with organizations implementing measures to ensure success. Absenteeism refers to an employee’s unplanned absence from regular work due to various reasons such as illness or emergencies [22]. HRM defines absenteeism as the percentage of absent days and must respond appropriately to maintain operations, including having potential substitute employees [24]. Early identification of employees who are likely to leave or to be frequently absent is also important for succession planning and workforce reallocation [6,7].

However, firms often rely on subjective evaluations and formal hierarchies to find substitutes, overlooking informal organizational structures like employee networks. These networks represent actual work relationships, often not aligned with formal structures [17,25]. While some studies [12,25,26] suggest identifying substitutes through similar tasks or work relationships, they often overlook the evolving nature of employee relationships, especially in the context of remote work triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic [1,10,23]. These changes should be considered when selecting substitute employees [22]. Explainable AI-powered models for predicting employee attrition can further aid in proactive substitute selection by providing interpretable insights [9,10,24,27].

2.2. Theoretical Framework

To rigorously ground our proposed model, we integrate three core organizational theories: Social network theory, Transactive memory systems, and Person–Group fit.

2.2.1. Social Network Theory: Cohesion and Structural Equivalence

Social network theory posits that an actor’s position in a network determines their access to resources and ability to perform [17]. In the context of substitution, two network properties are critical: cohesion and structural equivalence. Cohesion refers to the strength of direct relationships (strong ties), which fosters trust and tacit knowledge sharing. Structural equivalence, conversely, refers to actors who occupy similar positions in the network structure, even if they do not know each other directly (e.g., two managers who interact with the same set of developers) [19]. An effective substitute must ideally possess high structural equivalence to the absent employee to seamlessly step into their role without disrupting the network’s flow of information and influence. Our graph-based approach utilizes GNN embeddings to capture this structural equivalence mathematically; inductive architectures such as GraphSAGE learn node representations from local neighborhoods and can generalize them to new nodes and evolving organizational graphs [21].

2.2.2. Transactive Memory Systems

Groups develop a transactive memory system (TMS), a shared division of cognitive labor where members know who possesses specific expertise and how to access it [18]. When a member leaves, the TMS is disrupted, potentially causing performance failures and coordination breakdowns. Selecting a substitute who is socially or structurally close to the existing group helps preserve the TMS, as the newcomer is likely to share the same “language,” protocols, and meta-knowledge as the group. Our macroscopic analysis (clustering) aims to identify substitutes within the same or similar network clusters to minimize this cognitive disruption and maintain the integrity of the team’s shared memory.

2.2.3. Person–Group Fit

Person–Group (P–G) fit is defined as the interpersonal compatibility between individuals and their work groups. High P–G fit is strongly associated with job satisfaction, team cohesion, and performance, as demonstrated by meta-analytic evidence on multiple forms of person–environment fit [20]. Modern fit theory distinguishes between supplementary fit (similarity in characteristics, such as values or work styles) and complementary fit (filling a gap in the group’s capabilities). Our model operationalizes supplementary fit by calculating the cosine similarity between the substitute’s behavioral or interaction vector and the group’s average vector. This ensures that the selected substitute not only has the technical skills (Person–Job Fit) but also aligns with the collaborative dynamics of the team (P–G fit), thereby supporting both performance and retention.

2.3. Factors to Select Substitute Human Resources

In order to solve the manpower shortage caused by the outflow of manpower, the movement of internal manpower is critical [3,4,8,10]. However, if workers who do not have sufficient capabilities or network embeddedness are selected as replacements, the organization will become less efficient and may suffer additional knowledge loss. Therefore, deriving factors for selecting qualified internal manpower is a very important task. According to previous research (e.g., Lim et al., 2022), individual members’ work characteristics (e.g., workload, task portfolio) and cooperation patterns are important factors for substitute selection [11,12,25,26].

However, prior studies have the limitation of not sufficiently considering the characteristics of the group or department to which the replacement workforce belongs. The culture, strategy, and collaborative routines within each group or department will also be different, and these contextual factors influence the success of internal mobility and substitution [3,4,13,20]. Therefore, a model must be developed that takes into account not only the characteristics of individual members but also the characteristics of the group or department to which they belong, including their network position, TMS, and P–G fit.

Proposition:

The validity of a model that considers both individual capabilities (Microscopic) and group dynamics (Macroscopic) will be higher than that of a model that considers only individual work characteristic factors.

3. Graph-Based Analytic Approach to Identifying Substitute Human Resources

Effectively identifying and selecting suitable substitute personnel necessitates a comprehensive and multifaceted approach. In this study, we adopt a design-science and simulation-based research design: we first build a dual-level graph-based model for substitute selection and then evaluate its performance through controlled simulation experiments using real event-log data. The approach is primarily explanatory and predictive, as it aims to explain why certain internal candidates perform better as substitutes (given their position in the work relationship network) and to predict the impact of different substitution choices on process performance.

This process needs to consider two essential perspectives: the personal and interpersonal dynamics among individual employees, as well as the relationships within the various groups or teams to which these employees belong. By considering both the individual connections and the group-level interactions, organizations can make more informed and strategic decisions when it comes to staffing and succession planning. This holistic approach helps ensure that the selection of substitute personnel not only meets the technical and functional requirements of the role, but also aligns with the existing social and collaborative structures within the organization.

Therefore, it is essential to conduct both a microscopic analysis of individual relationships and interactions and a macroscopic analysis of the overall collaborative structure within the organization. Microscopic analysis focuses on the detailed interactions between individual employees, while macroscopic analysis examines the relationships between the groups to which these individuals belong, providing a broader perspective on the organizational structure. This comprehensive approach ensures that substitutes are not only compatible on an individual level but also fit well within the larger organizational context, thereby enhancing collaboration and overall performance.

3.1. Work Relationship Network

To perform the two types of analyses required to find substitute personnel, it is crucial to establish a work relationship network that focuses on the work-related connections among employees. The work relationship network is a social network that depicts the collaborative relationships among employees within an organization. This network is constructed using attributes derived from event logs recorded by information systems. These event logs document and track all activities within a business process.

In this study, we assume that event logs contain attributes such as case IDs, activity names, resource names, and timestamps. Let A represent the set of activities (tasks), R the set of resource (employees), and T the set of timestamps indicating when resource starts executing an activity. Consequently, represents the set of all possible events, which are combinations of activity, resource, and timestamp. The set of possible event sequences, or traces that describe a case, is denoted as . B(C) represents the set of all bags (multi-sets) over C. An event log captures these sequences.

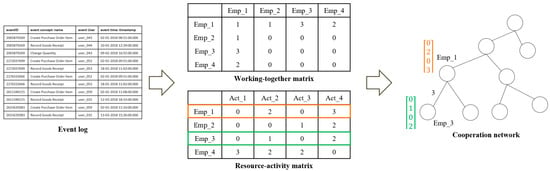

The proposed approach in this research derives two matrices from the event logs: a working-together matrix and a resource-activity matrix. The working-together matrix records the frequency with which two employees execute activities within the same case. Notably, it excludes situations where the same employee executes activities multiple times within the same case, as an employee cannot substitute itself. The second is a resource-activity matrix, which records the number of times each employee executes specific activities.

The work relationship network G is an undirected graph that is represented as a 2-tuple G = (V, E), where denotes a node that represents employees, and = ( indicates an edge connecting and if they work together within the same case; has a node attribute , which is a vector corresponding to row of the resource-activity matrix. has its weight corresponding to the value of row i and column j of the working-together matrix. Figure 1 shows an example of building a cooperation network by using the two matrices.

Figure 1.

Method to build a work relationship network.

3.2. Macroscopic Analysis Considering Inter-Group Relationships

To understand the relationships between the groups to which personnel belong, it is necessary to cluster personnel with similar attributes and network roles. This allows us to identify employees who are structurally equivalent—occupying similar positions in the organizational workflow.

To achieve this, we employ a graph neural network (GNN) approach. Specifically, we selected the GraphSAGE (Graph Sample and Aggregate) framework. The choice of GraphSAGE over other embedding methods like Node2Vec or DeepWalk is critical for two reasons:

- Inductive learning vs. transductive learning: Traditional methods like Node2Vec are transductive, meaning they learn embeddings for a specific, fixed graph. If a new employee joins or the network structure changes (a common occurrence in dynamic business environments), the entire model must be retrained. In contrast, GraphSAGE is inductive. It learns aggregator functions that can generate embeddings for unseen nodes by sampling and aggregating features from a node’s local neighborhood. This makes our model scalable and applicable to dynamic, evolving organizational networks.

- Feature integration: Unlike pure topology-based methods, GraphSAGE naturally integrates node features (e.g., the resource-activity matrix) with network structure. This ensures that the resulting embeddings capture both what an employee does (Individual Capability) and who they interact with (Group Dynamics).

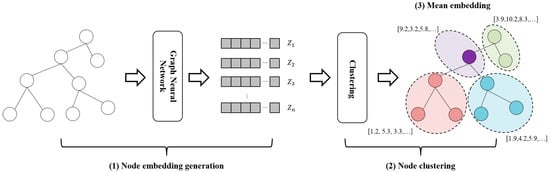

Figure 2 illustrates the method. First, GraphSAGE generates embeddings for each employee node. Second, we apply a hierarchical clustering algorithm to these embeddings to group nodes into clusters based on their structural and attribute similarity. Finally, we calculate the mean embedding vector for each cluster to represent the collective characteristics of that group.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic analysis method. The different colors represent distinct clusters formed by applying a hierarchical clustering algorithm to the node embeddings, grouping nodes based on their structural and attribute similarity.

By calculating the cosine similarity between these cluster mean vectors (Equation (1)), we can quantitatively evaluate the person–group (P—) Fit. A high similarity score indicates that the substitute comes from a group with similar collaborative norms and structural roles as the absent employee, thereby minimizing disruption to the team’s transactive memory system. The cosine similarity ( between groups A and B, represented by their mean vectors and , is calculated as follows:

3.3. Microscopic Analysis Considering Individual Relationships

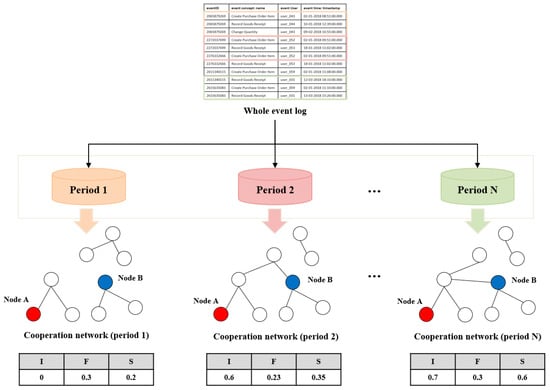

Unlike macroscopic analysis, the detailed relationships and collaborations between individual personnel are constantly evolving over time. To identify these dynamic characteristics, it is essential to construct work relationship networks for specific periods and analyze them accordingly, including changes over time.

Figure 3 below illustrates the process of calculating the similarity between individual personnel through period-based network analysis. First, we decompose the event logs covering the entire period into specific time intervals and construct a work relationship network for each period. Then, within each network, we calculate the collaboration intensity, collaboration frequency, and task similarity between the absent personnel and their potential substitutes.

Figure 3.

Microscopic analysis method.

Collaboration intensity measures the strength of the relationship between the substitute personnel node and the absent personnel node. Instead of simply indicating whether the two personnel have collaborated (1 for yes, 0 for no), it uses the inverse of the shortest path length between the two nodes to reflect the intensity more accurately. A shorter path results in a higher value, indicating closer collaboration. The underlying rationale is that shorter paths in a network signify more direct or frequent interactions. Therefore, collaboration intensity is defined as follows:

Collaboration frequency evaluates how often the absent personnel and substitute personnel have collaborated. The frequency of interactions is crucial as it indicates how well the personnel understand each other’s work methods and procedures. Higher interaction frequency suggests that the personnel have established a better working relationship, making the substitute personnel more suitable for the role. This metric is based on the assumption that repeated interactions foster better teamwork and understanding.

Task similarity assesses how similar the work characteristics of the personnel are. It is calculated based on the work frequency vectors represented by the node attributes. These vectors reflect the specific tasks performed by each personnel and the frequency with which they perform them. Higher task similarity indicates that the substitute personnel can more effectively take over the tasks of the absent personnel. This is because personnel who frequently perform similar tasks are likely to have developed comparable skills and knowledge.

Finally, we calculate an overall similarity score between the absent personnel and the substitute personnel by applying a weighted average to the three metrics obtained for each period. This weighted average reflects the importance of each period, evaluating how collaboration experience during specific periods influences the overall similarity. In this study, we place more importance on recent periods to prioritize personnel with experiences similar to the current work environment. The formula below represents the similarity between personnel by incorporating the three metrics and period-specific weights:

3.4. Substitution Score

In the process of selecting substitute personnel, it is crucial to consider various factors comprehensively to identify the most suitable candidates. By combining macroscopic analysis with microscopic similarity assessments, we can conduct a thorough evaluation of potential substitutes, comparing their strengths and weaknesses to make the final selection. This approach ensures enhanced collaboration efficiency within the organization and guarantees continuity in operations.

Through this comprehensive approach, we can evaluate the suitability of each candidate as a substitute from an organizational perspective, selecting the optimal candidate who meets the organization’s needs and goals. Therefore, the steps of comprehensive evaluation and final selection are critical in the substitute personnel selection process, contributing to improved collaboration efficiency and performance within the organization.

During the selection process, the final substitution score is calculated using the average vectors of clusters obtained from the macroscopic analysis and the personnel similarity scores derived from the microscopic analysis. For instance, if the absent personnel belong to Cluster A and the substitute personnel belong to Cluster B, we calculate the similarity between the average vectors of A and B. This similarity is then multiplied by the personnel similarity score obtained from the microscopic analysis to determine the final substitution score. The formula for calculating the substitution score is as follows:

represents the similarity between the average vectors of Cluster A ( and Cluster B (, and represents the similarity score between the absent personnel () and the substitute personnel () based on their collaboration intensity, frequency, and task similarity. This combined score provides a holistic view of how well the substitute personnel can fit into the role of the absent personnel, considering both their individual relationships and their group dynamics within the organization. This method ensures that the selected substitute personnel not only have similar work characteristics but also fit well within the existing wok relationship network, enhancing overall organizational efficiency and performance.

4. Validation

An enriched event log for the incident management process was extracted from a ServiceNow™ platform instance utilized by an IT company. ServiceNow™ provides an audit system that captures data related to all events managed by the system, including incident-specific data. This platform includes five basic process activities related to incident process management. The basic processes consist of (1) incident identification and classification, (2) initial support, (3) investigation and diagnosis, (4) resolution and reestablishment, and (5) closing. Each stage is performed by responsible resources. An example from the enriched event log is shown in Table 1, referring to a single incident (INC001). The event log includes a case identifier and an incident status variable, along with 34 descriptive attributes, totaling 36 attributes. It includes one audit attribute (sys_updated_at) and four descriptive attributes (number, incident_state, category, location, category, subcategory, and u_symptom). Table 2 shows the 8 attributes used in this study, along with their descriptions and roles in the research.

Table 1.

Example of incident management process event log.

Table 2.

Description of attributes of the event log.

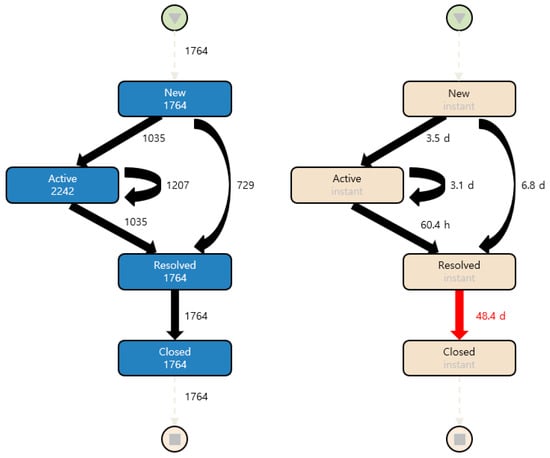

These audit records were used to construct the main structure of the event log records for mining purposes. The data spans 12 months (from March 2016 to February 2017), covering 24,918 traces and 141,712 events. Pre-processing was used to filter out the noise and organize audit records in an orderly sequence compatible with an event log format. First, incidents that do not start with “New” and do not end with “Closed” are removed. Next, a new variable, “incident_type”, was created to analyze the combinations of incident attributes. Using this variable, cases that performed incidents below a certain threshold were removed, as well as cases that do not perform the same incident within each case. After this pre-processing, the final remaining cases are 1764 and the events are 7534. Figure 4 shows the process model and mean duration derived using Disco, one of the process mining tools, from the pre-processed event log.

Figure 4.

Process model of incident management process. The symbol with an inverted triangle at the top represents the start of the process, while the symbol with a square at the bottom indicates the end. The lowercase letters “d” and “h” denote days and hours, respectively.

4.1. Macroscopic Analysis

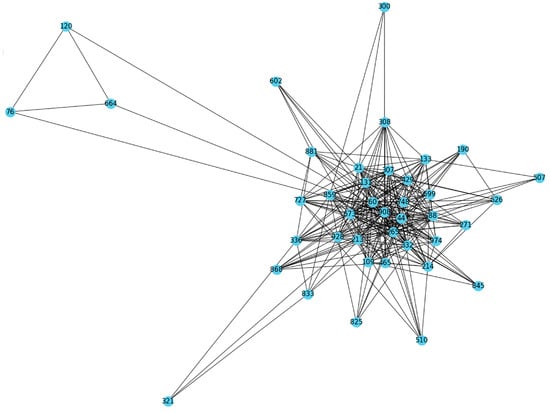

Based on the pre-processed data, a work relationship network was created to represent the interactions between resources for each case in the incident process. Each node in the network represents an employee, and the edges between nodes represent the collaboration between two employees within the same case. Additionally, each node’s attribute is represented by a vector of the incident types, denoted as an “incident_type” variable, performed by the employee. Figure 5 shows an example of a work relationship network drawn by randomly extracting 40 nodes among 165 resources.

Figure 5.

Example of work relationship network.

To generate embeddings for the nodes in the work relationship network, we selected GraphSAGE, GCN (Graph Convolutional Network), GAT (Graph Attention Network), and GIN (Graph Isomorphism Network) models. The GraphSAGE model aggregates the features of neighboring nodes to learn the node embeddings. The GCN model learns the node features using a convolution approach on the graph structure. The GAT model uses an attention mechanism to consider the importance of neighboring nodes during training. The GIN model aggregates the features of neighboring nodes while considering the graph’s isomorphism. Hyperparameter tuning was conducted for each model, and Table 3 shows the GraphSAGE model with the highest accuracy and its hyperparameter values.

Table 3.

The hyperparameters of the best model.

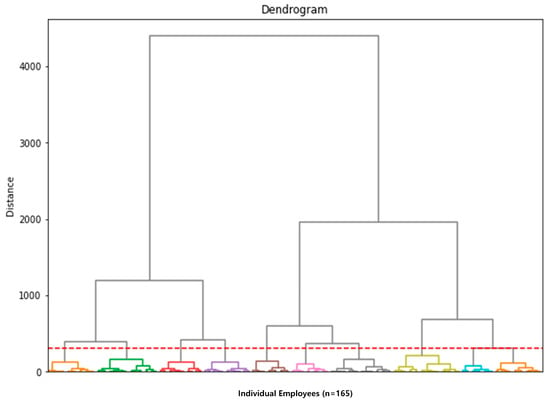

For this validation, we defined the GraphSAGE model using the optimal hyperparameters and used it to generate node embeddings. Then we applied a hierarchical clustering algorithm to the generated node embeddings, dividing them into a total of 10 groups, and derived the average vector for each group. Figure 6 shows the dendrogram for the 10 groups. Finally, we calculated the similarity between the groups using the average vectors of the clusters.

Figure 6.

Employee dendrogram for the incident management process. The red dashed line represents the clustering cut-off threshold, which divides the 165 employees into 10 distinct groups, distinguished by different colors. Individual node labels on the x-axis are omitted for visual clarity.

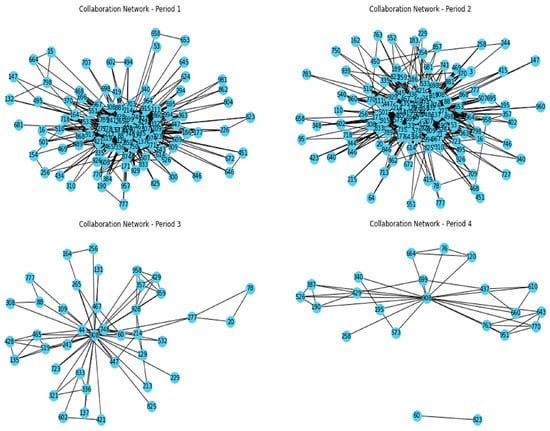

4.2. Microscopic Analysis

After completing the macroscopic analysis, we conducted a microscopic analysis. Since the entire period of the event log is one year, we divided it into four intervals of three months each. The data is split into four separate datasets, each corresponding to one of the time periods. For each period, a work relationship network is created, which is shown in Figure 7. In these networks, each node represents a resource and the edges between nodes represent collaboration between resources within the same case. Additionally, each node is assigned a vector that captures the types of incidents the resource has performed, enriching the network with task-specific information.

Figure 7.

Work relationship networks for each period.

For each period-specific network, three key metrics are calculated between pairs of nodes: collaboration intensity, collaboration frequency, and task similarity. The metrics calculated for each period are then combined using specified weights. These weights reflect the importance of each period in the overall analysis. For instance, more recent periods might be given higher weights to reflect the current state of collaboration. In this analysis, weights of 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, and 0.1 were assigned to the most recent period to the oldest period, respectively. By applying these weights, the analysis can emphasize recent collaboration trends and adjust for any changes over time. This weighted approach ensures that the most current data has a greater influence on the overall similarity scores, providing a more accurate reflection of the current state of collaboration.

For every pair of employees, a combined similarity score is calculated by weighting and summing the collaboration intensity, frequency, and task similarity across all periods. This score reflects the overall similarity and potential substitutability between two resources. Finally, the similarity between the groups and a combined similarity score between every pair of resources are multiplied to calculate the substitution score. This score is then used to identify substitute personnel for the absent employees.

4.3. Experimental Setting

To validate the methodology proposed in this study, we adopt a simulation based comparative design. Our proposed dual-factor model is benchmarked against ProST-re [12], a simulation-based analytics method that identifies substitute personnel using only individual level work characteristics such as task frequencies and workload. ProST-re does not incorporate work relationship networks or group level similarity and therefore represents an appropriate baseline for evaluating the added value of the macroscopic (group) component of our model. Within this comparative framework, we define four evaluation scenarios, each designed to examine a different aspect of substitute selection performance.

The first scenario compares the total processing time obtained when the best substitute recommended by our proposed methodology is used for a specific absent employee with the total processing time obtained when the best substitute according to the existing method is used for the same employee. By contrasting these two cases, we can directly assess whether the proposed methodology yields more efficient substitution decisions than the baseline.

The second scenario focuses on cases where the two methods provide highly divergent rankings. Specifically, we compare the total processing time of the substitute who receives the lowest score in the existing method but the highest score in our methodology with that of the substitute who receives the highest score in the existing method. This scenario highlights situations in which a candidate overlooked by the existing method is regarded as highly suitable by the new methodology, thereby revealing qualitative differences between the ranking logics.

The third scenario evaluates the robustness of the rankings produced by our approach beyond the top ranked candidate. Here, we compare the total processing time achieved when using the second-best substitute suggested by our methodology with that of the top ranked substitute from the existing method. This allows us to examine whether our model consistently recommends effective personnel across different ranks, rather than only at the very top of the list.

Finally, the fourth scenario extends the comparison to a multi absence context. We compare the total processing time when multiple absent employees are replaced by the highest ranked substitutes from each method. By examining how each method performs when several employees are absent simultaneously, this scenario provides a comprehensive evaluation of the practicality and robustness of the proposed methodology across more complex and realistic situations.

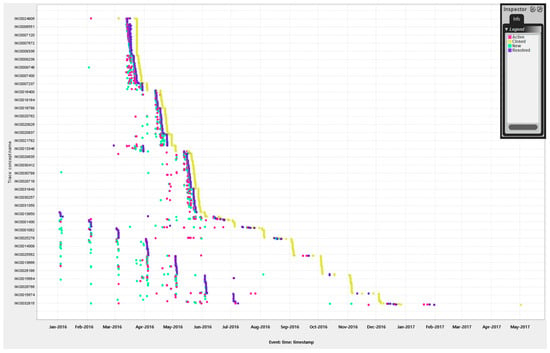

To implement these scenarios, we built a simulation model using the SimPy package provided by Python (version 3.13). This simulator is designed to model the incident management process within an organization by simulating the arrival and handling of incidents over time. To construct the simulation model, we first analyzed the incident process in detail. By plotting a dotted chart of the incident process, we observed that it could be broadly divided into two groups (i.e., long and short), as shown in Figure 8. In this study, we distinguished these two groups based on whether the total processing time exceeded 30 days. For each group, we identified the employees involved in executing the processes and calculated the average duration required for these resources to complete their respective tasks. This data was then used to construct the simulation model, ensuring that the simulation accurately reflects real-world conditions and provides reliable insights for comparing the methodologies.

Figure 8.

Dotted chart for the incident management process.

The simulator is initialized with various data inputs, including definitions of process variants for long and short groups, arrival times for incidents, employee pools for different process categories (long or short), and the median durations for activities. The simulator first identifies which process variant for each incident based on its category (long or short) and incident type) and then randomly selects a specific variant for the given incident. The simulation begins by scheduling incident arrivals based on pre-defined arrival times. Each incident arrival triggers the initiation of the incident handling process, where the simulator processes the incident according to the selected variant. For each activity in the variant, the simulator determines the appropriate employee to handle the activity. It looks up resources that match the current activity and incident type, and if a matching resource is found, it randomly selects one to perform the task. If no matching resource is found, a default duration is used.

The results of the simulation are stored for further analysis, providing insights into the performance and dynamics of the incident management process. The simulator records the start and end times of each activity for every incident, maintaining a detailed log of the simulated incident management process. This log includes the case ID, activity type, incident type, category (long or short), process variant used, and the start and end times for each activity.

While the simulator incorporates detailed routing logic and resource assignments extracted from the event log, several simplifying assumptions are made. We assume that arrival patterns and process variants remain stable over the observation period, that employees’ service times are stationary (captured by average or median durations), and that there are no learning or fatigue effects. As a result, the simulation should be interpreted as an explanatory “what if” tool for comparing substitute selection strategies rather than as an exact replica of all behavioral nuances in the organization.

Table 4 below presents the performance validation results of the simulation model. The simulation model’s total time was compared against the real event log data for both long and short groups. The difference between the simulation and real event log was minimal, with a difference of just 1 h 45 min and 5 s for the long group, and 28 min and 46 s for the short group. These small discrepancies indicate that the simulation model accurately replicates real-world conditions, thereby validating its appropriateness and reliability for further analyses and experiments.

Table 4.

Performance validation results of the simulation model.

4.4. Results

In this section, we present the results of our four scenarios, comparing the total time taken for substitute personnel identified by our proposed methodology and those identified by the existing methods. For the purpose of this illustration, we randomly selected absent employees to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed methodology. To ensure consistency and reliability, we performed the simulation 100 times for each scenario and each methodology, and calculated the average total time.

For the first scenario, we compared the total time taken for a specific absent employee, where the highest score substitute personnel were identified by both our proposed methodology and the existing methodology. In this case, the absent employee was Employee 429. The substitute identified by our proposed methodology was Employee 190, who took a total of 162 days, 3 h, 45 min, and 30 s for the long group and 10 days, 7 h, and 45 min for the short group. In contrast, the substitute identified by the existing methodology was Employee 387, who took 163 days, 19 h, 8 min, and 57 s for the long group and 10 days, 14 h, 2 min, and 19 s for the short group. The difference of 1 day, 15 h, 23 min, and 27 s in the long group and 7 h, 1 min, and 34 s in the short group demonstrates the efficiency of our approach.

In the second scenario, we compared the total time taken for a specific absent employee, where the substitute personnel identified by our proposed methodology received the highest score, and the substitute identified by the existing methodology received the lowest score in the existing method. The absent employee was Employee 195. The substitute identified by our methodology was Employee 573, who completed the tasks in 161 days, 21 h, 24 min, and 28 s for the long group and 10 days, 6 h, and 34 min for the short group. The lowest scored substitute by the existing methodology was Employee 908, taking 162 days, 16 h, 0 min, and 1 s for the long group and 10 days, 8 h, and 48 min for the short group. The difference in performance highlights the significant advantage of our methodology.

For the third scenario, we compared the total time taken for the second-best substitutes identified by our proposed methodology against the top substitute identified by the existing methodology. The absent employee was Employee 951. The second-best substitute identified by our methodology was Employee 643, who took 162 days, 11 h, 1 min, and 22 s for the long group and 10 days, 12 h, and 33 min for the short group. The top substitute identified by the existing method, Employee763, took 163 days, 0 h, 21 min, and 21 s for the long group and 10 days, 15 h, 18 min, and 39 s for the short group. The results indicate that even the second-best substitute identified by our methodology performs better.

In the fourth scenario, we compared the total time taken for substitutes identified by both methodologies for multiple absent employees. The absent employees were Employee 908 and Employee 437. The top substitutes identified by our proposed methodology were Employee 664 and Employee 610, who took a combined total of 163 days, 1 h, 44 min, and 4 s for the long group and 10 days, 15 h, 19 min, and 49 s for the short group. In contrast, the top substitutes identified by the existing methodology were Employee 429 and Employee 600, who took 163 days, 16 h, 12 min, and 8 s for the long group and 10 days, 19 h, 40 min, and 2 s for the short group. The large difference in performance demonstrates that for multiple absent employees, our methodology’s substitutes completed the tasks faster, indicating the robustness and practical applicability of our approach in handling complex scenarios.

Overall, the results from these scenarios demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed methodology in identifying more efficient substitute personnel, resulting in significant time savings compared to existing methods.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary and Discussion

This research presented a comprehensive approach to identifying and selecting substitute personnel by simultaneously considering individual capabilities and group dynamics within an organization. Previous studies on internal substitute selection and task reallocation have largely emphasized individual work characteristics—such as workload, task frequency, or role similarity—while treating group context and collaborative structure as secondary or ignoring them altogether [12,25,26]. By contrast, our approach explicitly integrates a macroscopic perspective, based on clusters in the work relationship network, with a microscopic perspective that captures dyadic collaboration patterns. In doing so, the study responds to the theoretical argument that human capital and social capital jointly shape performance and that internal mobility decisions should reflect both.

Across four simulation scenarios, the proposed dual-factor model consistently outperformed the existing method based solely on individual factors. In Scenario 1, when comparing the best ranked substitutes from each method for the same absent employee (Employee 429), our approach produced shorter total processing times in both long and short incident groups (Table 5). Scenario 2 further highlighted cases where a candidate highly rated by our method but poorly ranked by the baseline (Employee 573 vs. Employee 908) led to substantial time reductions (Table 6). Scenario 3 showed that even the second-best substitute identified by our model outperformed the top candidate suggested by the existing method (Table 7), indicating that the ranking produced by the dual-factor model is robust beyond the very top position. Finally, Scenario 4 demonstrated that for multiple simultaneous absences, our method continued to achieve lower total processing times than the baseline (Table 8). Taken together, these results suggest that incorporating group level similarity and network position systematically improves substitution decisions, rather than merely offering marginal or case specific gains.

Table 5.

Validation result of scenario 1.

Table 6.

Validation result of scenario 2.

Table 7.

Validation result of scenario 3.

Table 8.

Validation result of scenario 4.

These empirical patterns are consistent with the theoretical foundations of the model. Social network theory and the concept of structural equivalence argue that actors occupying similar positions in a network can more easily substitute for one another in the flow of information and coordination. When our macroscopic component selects candidates from clusters that are structurally close to the absent employee, it effectively operationalizes this principle. Likewise, the microscopic component favors candidates with strong collaboration intensity, frequency, and task similarity, which aligns with the logic of transactive memory systems and person–group fit: substitutes who share a history of collaboration and similar task portfolios are more likely to understand the team’s “who knows what” structure and to integrate smoothly into existing routines. The superior performance of the dual-factor model therefore provides behavioral support for these theoretical expectations.

The results also extend prior work on process mining based HR analytics and internal mobility. Compared with ProST re [12], which focuses on simulation-based evaluation of candidates using individual task data, the proposed approach adds a network centric layer that captures how employees are embedded in the broader collaboration structure. Studies such as Lee et al. [26] and Chiorrini et al. [25] showed that event logs and process mining can be used to handle personnel unavailability, but they did not incorporate graph neural networks or cluster level similarity measures. Our work contributes methodologically by demonstrating how inductive graph neural networks (GraphSAGE) can be combined with dynamic similarity metrics to generate substitution scores that are both theoretically grounded and empirically effective.

In summary, the findings indicate that treating the organization as a complex network of relationships—rather than as a collection of isolated individuals—yields more accurate and robust substitute selection decisions. The dual-factor model confirms the central proposition of this study: models that integrate individual capabilities (microscopic) with group dynamics (macroscopic) exhibit higher validity than models that consider only individual work characteristics. This has important implications for organizations seeking to design HR analytics tools that support resilient, network aware workforce planning.

5.2. Limitation and Future Research

This study incorporates both group and individual task characteristics, including workload, job roles and collaboration patterns. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the validation relies on data from a single incident management process within one organization and focuses on total processing time as the primary performance indicator. Future research should test the model on multiple processes and organizations and incorporate additional outcome measures such as cost, service quality, or employee well-being. Second, it is imperative to consider a more comprehensive set of variables in future studies. For instance, factors such as employee skill sets, cultural differences, language proficiency, and adaptability to diverse working environments should be examined to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics involved in workforce management.

Third, future research should explore the impact of integrating foreign workers as substitutes for domestic personnel. This would involve identifying and analyzing various factors associated with employing foreign personnel, such as legal regulations, cultural integration, and language barriers, and assessing how these factors influence the effectiveness of foreign workers as substitute personnel. Expanding the scope of research to include these diverse variables will enhance our understanding of the dynamics involved in substitute personnel selection and improve the robustness of the proposed methodology.

Such a comprehensive approach will enable organizations to optimize their workforce management strategies not only within their domestic operations but also in an increasingly globalized work environment. This is particularly important as organizations grapple with the challenges and opportunities presented by a diverse and geographically dispersed workforce. By considering a broader range of factors, future studies will provide organizations with more effective tools and strategies for managing their human resources in a way that maximizes productivity, collaboration, and adaptability in the face of evolving business demands.

5.3. Theoretical, Methodological, and Practical Implications

This study offers several theoretical implications. By explicitly combining social network theory, transactive memory systems, and person–group fit into a single substitute-selection framework, it illustrates how individual capabilities and group-level network structures jointly shape performance. The empirical results support the idea that structural equivalence and P–G fit are not only useful descriptive concepts but can also be operationalized in algorithmic decision-support systems for internal mobility.

Methodologically, the research demonstrates how graph-based machine learning can be integrated with process-mining data and discrete-event simulation in HR analytics. The use of an inductive graph neural network (GraphSAGE) enables the model to handle evolving organizational structures and new employees without retraining on the entire graph, while the dynamic microscopic similarity metrics capture temporal changes in collaboration patterns. This design can serve as a template for future studies that wish to use event logs and work-relationship networks to support other HR decisions, such as team formation, succession planning, or workload balancing.

From a practical standpoint, the proposed approach provides HR managers and process owners with a systematic tool for identifying internal substitutes that preserve both task performance and collaborative fit. The substitution score can be embedded into decision-support dashboards to highlight robust candidate pools under different absence scenarios and to perform “what if” analyses before reorganizing teams. In contexts characterized by remote or hybrid work and frequent organizational change, such tools can help organizations maintain continuity, reduce the risk associated with unplanned absences, and design more resilient human resource pipelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and C.S.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; formal analysis, J.L. and C.S.; data curation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; supervision, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed in this study, “Incident management process enriched event log,” is publicly available in the UCI Machine Learning Repository and can be accessed at: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/498/incident+management+process+enriched+event+log (accessed on 10 September 2025), as cited in reference [28].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vargo, D.; Zhu, L.; Benwell, B.; Yan, Z. Digital technology use during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, D.T.; Rauch, E. SME 4.0: The role of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the digital transformation. In Industry 4.0 for SMEs: Challenges, Opportunities and Requirements; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, B.I.; Nekhwevha, F.H. The future of work and uncertain labour alternatives as we live through the industrial age of possible singularity: Evidence from South Africa. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banmairuroy, W.; Kritjaroen, T.; Homsombat, W. The effect of knowledge-oriented leadership and human resource development on sustainable competitive advantage through organizational innovation’s component factors: Evidence from Thailand’s new S-curve industries. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2022, 27, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburumman, O.; Salleh, A.; Omar, K.; Abadi, M. The impact of human resource management practices and career satisfaction on employee’s turnover intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.; Roy, W. Succession planning: Securing the future. J. Nurs. Adm. 2004, 34, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, D.; Kumar, P. Succession planning: Developing leaders for tomorrow to ensure organisational success. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Prskawetz, A.; Fent, T. Workforce ageing and the substitution of labour: The role of supply and demand of labour in Austria. Metroeconomica 2007, 58, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, S.A.; Yang, S.; Chen, C. The Effect of Human Resource Analytics on Organizational Performance: Insights from Ethiopia. Systems 2025, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Morán, P.C.; Díez, F.; Solabarrieta, J.; Fernández-Rico, J.M.; Igoa-Iraola, E. Talent Management Digitalization and Company Size as a Catalyst. Systems 2024, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Torres, B.; Camargo, M.; Dumas, M.; García-Bañuelos, L.; Mahdy, I.; Yerokhin, M. Discovering business process simulation models in the presence of multitasking and availability constraints. Data Knowl. Eng. 2021, 134, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Choi, I.; Sung, S. ProST-re: Simulation-Based Analytics for Finding Appropriate Substitutes and Task Reallocation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 125477–125488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jotabá, M.N.; Fernandes, C.I.; Gunkel, M.; Kraus, S. Innovation and human resource management: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalah, S.; Aravindan, K.L.; Raman, M.; Paraman, P. SME Engagement with Open Innovation: Commitments and Challenges towards Collaborative Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krmela, A.; Šimberová, I.; Babiča, V. Dynamics of business models in industry-wide collaborative networks for circularity. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Mohan, A.V.; Zhao, X. Collectivism, Individualism and Open Innovation: Introduction to the Special Issue on ‘Technology, Open Innovation, Markets and Complexity’. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2017, 22, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Halgin, D.S. On network theory. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1168–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M. Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In Theories of Group Behavior; Mullen, B., Goethals, G.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lorrain, F.; White, H.C. Structural equivalence of individuals in social networks. J. Math. Sociol. 1971, 1, 49–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017); Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1024–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, M.A.; Rockoff, J.E. Worker absence and productivity: Evidence from teaching. J. Labor Econ. 2012, 30, 749–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, P.C.; McElroy, J.C.; Laczniak, K.S.; Fenton, J.B. Using absenteeism and performance to predict employee turnover: Early detection through company records. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorrini, A.; Diamantini, C.; Potena, D.; Storti, E. How to Cope with Personnel Unavailability? Process Mining May Help! In Proceedings of the SEBD, Villasimius, Italy, 21–24 June 2020; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Choi, I. Dynamic human resource selection for business process exceptions. Knowl. Process Manag. 2019, 26, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydili, İ.T.; Tasci, B. Predicting Employee Attrition: XAI-Powered Models for Managerial Decision-Making. Systems 2025, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C. Incident Management Process Enriched Event Log; UCI Machine Learning Repository: Irvine, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.