Abstract

Uncertainties and changes significantly shape the path of the design process, requiring situation-specific strategies and methods. Literature and practice highlight the implementation of agility as a means for companies to achieve competitive advantages in a dynamic development environment through more robust costumer integration and improved responsiveness. From a design science perspective, a key challenge remains the development of a theoretical model that explains how agility can be operationalized to realize benefits such as enhanced adaptability. Drawing on a literature review and six empirical studies on agile development of mechatronic systems in the German-speaking context, we propose a novel conceptualization of agility. Using systems thinking, we conceptualize agility as a construct and establish its relationship to agility as an attribute. Thus, the article provides a new methodological perspective on agility by explicitly linking its structural elements to established outcome perspectives from multiple domains. This work advances the methodological understanding of agility and identifies future research directions for the development of mechatronic systems, aiming to enrich the theory for its utilization.

1. Introduction

The field of design science is multidisciplinary engaging with approaches from neighboring disciplines and facilitating the creation of artefacts such as explanatory models, patterns, and structures for researchers and practitioners [1]. Thus, the primary objective of design science research is to achieve utility by developing artefacts that offer practical value for researchers and practitioners [2]. Hence, Hevner et al. [2] argue that an artefact can prove beneficial while the underlying theory remains concealed. However, this can lead to challenges in adaptation or use in the design process, since the design artefact lacks theoretical foundation. Therefore, a robust theory and understanding serve, for example, as a basis for process optimization (intended utility) in product design and development [1,3]. The efficient transformation of ideas into functional and high-quality products requires high-level technical know-how and creativity from development organizations and teams. It relies on their ability to design development process effectively and efficiently [4]. In order to adapt processes to specific situations, as argued above, a profound understanding and knowledge of the underlying mechanisms are necessary. As described by Albers et al. [5] this knowledge is of significant importance in achieving value creation for manufacturing companies. The changing environment calls into question design paradigms that have proven highly efficient in the past [6,7,8]. As a response, the agile approach has recently been postulated as a beneficial paradigm. While originally rooted in software development, agile approaches are adopted in the development of mechatronic systems for managing uncertain and changing conditions. Researchers and practitioners are increasingly exploring this new paradigm and its implementation into manufacturing companies [9,10,11,12,13], as the context and situation-specific use of existing agile approaches and methods are not straightforward. The following sections will delve into the background, the challenges within product design and development of mechatronic systems, and the purpose and aim of this paper.

1.1. Background

Agile approaches and methods are advocated as a potential solution for dealing with uncertain and volatile environments [14], and they are increasingly being applied in product development [8,15,16]. Although evidence exists that agile development is not exclusively a creation of software development [17,18], agile software development has contributed significantly to its prominence. Agile development builds on a foundational point of reference: the Manifesto for Agile Software Development. The manifest is a notable artefact that originated from a specific need. The founders of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development addressed a “better way” of developing software by showing an inherent weighting between different values [19]:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools;

- Working software over comprehensive documentation;

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation;

- Responding to change over following a plan.

In this regard, Dingsøyr et al. [20] emphasize that agile methods distance themselves from rationalized and plan-based approaches by placing capable professionals at the forefront. Nonetheless, essential processes, including planning, do not become obsolete as a result. Thus, Beck et al. [19] explicitly point out that they do not deny the values of the right side, but they value them less in uncertain environments. Therefore, the manifesto emphasizes value-adding activities in those uncertain environments. For instance, Meier and Kock [10] note that plan-driven approaches struggle handling unstable requirements, making maneuverability in executing plans essential. This is especially true in product design and development, where satisfying customer requirements is the priority [21]. Sticking rigidly to outdated plans or requirements is thus counterproductive.

Agile approaches and methods promote an incremental and iterative way of working, which proves advantageous in uncertain environments [22]. Thus, customer needs can be more effectively addressed by delivering increments frequently and as early as possible. This is partly because customer requirements can be continuously validated. Requirement changes are always welcome, even if they arise late in the design process. In this way, agile processes enable development organizations to use change as a competitive advantage [19].

The industry has adopted agile approaches and methods in both software and mechatronic system development as a means to realize the associated benefits [5,14,23]. Practitioners and consultants primarily applied and adapted agile methods and principles based on their specific experiences. However, not all companies have been equally successful in applying agile methods since mechatronic systems have some characteristics that clearly distinguish them from software. Therefore, a physical product must be interpreted differently and lead to adaptations in method application [9,11].

1.2. Challenges in Agile Product Design and Development

Manufacturing companies face challenges in adapting effectively and efficiently agile approaches and methods [24,25,26,27]. Those challenge stems from two main causes.

First, in contrast to mechatronic systems, software does not require materialization, so certain basic ideas, such as the increment, have to be reinterpreted [28,29]. These specific challenges can be attributed to what is referred to as the Constraints of Physicality [28]. For example, declaring working prototypes as the only measure of progress for product development projects seems unrealistic, which makes it necessary to validate progress in the project with other metrics in a more differentiated manner [30,31]. As researchers explain, the use of prototypes should also be considered strategically, as a more significant time investment does not necessarily correlate with greater success [32]. As a result, other artefacts are needed for validation. Another example is that manufacturing companies must frequently integrate suppliers, both in terms of processes and contractual arrangements [33], which can introduce additional obstacles in developing increments or integrating agile elements.

Second, designing and developing complex mechatronic systems requires a substantially broader knowledge base (e.g., software engineering, electrical engineering and mechanical engineering), often necessitating several development teams that must be effectively managed [12]. Those specific challenges can be attributed to the phenomenon known as the Constraints of Scale [7] and contradict the agile paradigm [34]. For instance, due to parallel working, product development teams increasingly need to gather information necessary for decision-making or serve other development teams’ information needs [35]. This need manifests itself in direct and indirect dependencies of the teams [36]. Such dependencies impede the application of agile methods and create challenges for implementing agility in product development [9,11,23,37,38]. Accordingly, scale-related constraints must be taken into account when applying agile methods in order to obtain the propagated benefits [39,40].

These and other challenges (cf. [13,24,41,42]) hinder the successful adoption and application of agile approaches and methods in product design and development of mechatronic systems. Therefore, the beneficial utilization of agile methods for the development of those products remains unclear, and the specific circumstances that favor its most effective application remain undetermined [43].

Despite conducting multi-year surveys in agile product development, the authors find that recurring issues arise, posing challenges to the industry. This unsatisfactory situation prompted us to examine whether a theoretical or explanatory model could account the numerous published findings, while acknowledging that our empirical studies offer only a partial perspective on the underlying phenomena within the field of agile product design and development. Nonetheless, design science, along with other scholarly platforms, does not provide us with an explanatory model for achieving context and situation-specific agility, despite numerous contributions across various disciplines that address agility from different perspectives (e.g., [10,44,45,46,47,48,49]).

At present, systematizing results or providing a theoretically grounded explanation for attaining situation-specific agile behavior in the context of product design and development remains challenging and difficult. These findings underscore a research gap that requires further exploration from the authors’ perspective.

1.3. Purpose and Aim

This article aims to theoretically establish the context and situation-specific integration of agility in developing mechatronic systems and to advocate for further exploration within the context of agile product development. We argue that agile approaches have been shaped by practical experience, with specific constraints considered, particularly in achieving the associated attributes of agility. Accordingly, there is a pressing need for robust theoretical and explanatory models, especially in multidisciplinary settings, aimed at leveraging the optimal utilization and potential of agile methods for product design and development. As argued by Hevner et al. [2], the quality of concepts and constructs at a designer’s disposal directly influences their ability to articulate and define both problems and solutions. Thus, this article seeks to contribute to the knowledge base of design science by providing a solid theoretical foundation as a starting point for the context and situation-specific attainment of agility. The overarching objective is to refine theoretical mechanisms related to agile behavior to achieve a better understanding, serving as a foundation for purposeful application within the context of product design. The knowledge gained should help to derive recommendations for action for the concrete practical application and adaptation of the methods to specific product development contexts. In reference to this, the authors maintain the position that the means-end relationships within the context of product design and development remain under-theorized, as we are convinced that agile behavior exhibits nonlinear characteristics. Consequently, the aims of this article are as follows:

- (I)

- Classification of agility within the context of product design and development;

- (II)

- Contribute to theory by providing a systemic perspective on the construct of agility, enabling effective and efficient agile system behavior within the context of product design and development;

- (III)

- Foster additional systems-theoretical investigation of the agility construct.

The specified aims lead to the following research question:

- How can agility be conceptualized from a systems-theoretical perspective to support its context- and situation-specific application in product design and development?

The article is structured as follows to achieve these objectives: Section 2 deals with the applied methods. Section 3 deals with the fundamentals of product design and development. Section 4 is meant to clarify and interpret the term ‘agility’ in the context of product design and development. Based on that, a system-theoretical perspective of the construct of agility is derived, linking it explicitly to agility as an attribute. Section 5 discusses those results and places them into context. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the contributions and outlines further paths of investigation.

2. Research Approach, Materials and Methods

In order to address the research question, an in-depth understanding of agility’s mechanisms within product development is essential. The basis for the knowledge processing is provided by Ulrich’s [50] approach to application-oriented research. While researchers can identify generic relationships in principle, they must consider specific real-world conditions in their utilization, such as design constraints (e.g., constraints of physicality) or other contextual factors (e.g., organizational constraints). To describe the underlying causal mechanisms, researchers initially need to approach the agile development in mechatronic systems from a socio-technical systems perspective. Accordingly, researchers must approach the application of theories on agile design dynamics as a complexity problem, due to the high variability and dynamism in the behavior of system elements and their interconnections [50]. Thus, to account for this perspective, we interpreted both agility and the agile development of mechatronic systems from a system perspective. This systemic perspective is accompanied by the interpretation of a system as a dualism of structure and behavior [51]. In this sense, we interpret agility from two different perspectives: agility as an attribute (behavioral statement) and agility as a construct (structural statement). These considerations form the foundation of our research and are further grounded in empirical findings derived from our own data collection and analysis.

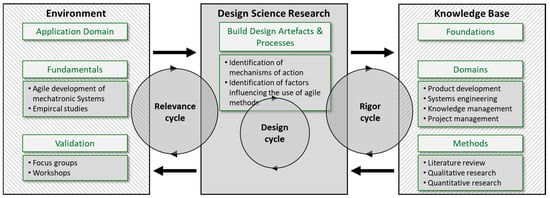

Thus, this article summarizes research conducted over several years on agile development of mechatronic systems in a coherent solution approach. The research methodology was based on Hevner’s Design Research Cycle frameworks [2,52], which is visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research approach adapted from the Design Science Research Cycles framework Hevner et al. [2] and Hevner [52].

The starting point for our research was the fact that agile methods for product development were initially adopted from practical experience. When adopted without reflection or sufficient knowledge foundation, these approaches do not necessarily yield successful outcomes, particularly when the contextual conditions of application differ substantially. Therefore, data were collected and analyzed through a longitudinal study in order to explore, structure, and describe the relevance and the problems of industry (cf. Relevance Cycle in Figure 1).

The data collection was based on a questionnaire that included both closed questions (i.e., allowing standardized quantitative analysis) and open questions (i.e., enabling the capture of qualitative perspectives).

For instance, demographic data included questions about company size, industry (e.g., mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, automotive), role in the company (e.g., agile coach, project manager, developer), and experience with agile methods. In addition to specific questions about benefits and expectations, the study also examined participants’ understanding of agility and their use of agile methodologies, methods, practices and frameworks. Furthermore, questions were generated each year to test hypotheses that arose from the results of the previous study and accompanying research on the development of the mechanisms of action of agile working.

Only industry representatives from German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) were surveyed, primarily to keep cultural differences to a minimum. To reach participants, we used mailing lists from the Association of German Engineers (VDI—Verein Deutscher Ingenieure e.V.), our project partner AGENSIS, and our own network of industry contacts. The data collection of the participants was anonymous.

Table 1 serves as the primary reference for the longitudinal study series to access specific results and research focuses. Furthermore, Table 1 outlines the key insights and the resulting considerations for the underlying conceptualization approach proposed in this article. However, these insights presented in Table 1 represent only a brief excerpt.

Table 1.

Key insights and considerations from the longitudinal studies for the proposed conceptualization of agility. Not all studies are published in English.

Regarding the Rigor Cycle (see Figure 1), the literature reviews were repeatedly carried out using the six-step process developed by Machi and McEvoy [53] to support hypothesis formation and advance concept development. The literature reviews initially focused on identifying challenges, potential, and applicability. For instance challenges discussed in the literature regarding the transfer of agile methods to the development of physical systems specified following Ovesen [28] and Schmidt et al. [29], which guided further research. Based on the findings, the scope of consideration was gradually expanded to include, for example, the need for scaling and methods for dealing with it [7], the impact on the structuring and coordination of information flows [54,55], and the values underlying agile product development [6]. As part of this research, a literature review was conducted, to further explore a systematic approach to conceptualize agility. Scopus and Google Scholar were used as literature databases.

This preceding research served as the basis for the conceptualization of agility and the methodological classification of agile approaches with the aim of describing mechanisms of action to support the adaptation to specific product design and development contexts. Thus, the article summarizes this knowledge and conceptualizes agility in the context of product design and product development as an attribute and construct.

3. Fundamentals of Product Design and Development

3.1. Characteristics of Product Development Processes

The added value in product development lies in the generation of data and information to transform and integrate ideas into products that are functional and of high quality for the user [56]. Thus, the development teams are responsible for generating solutions, verifying and validating their suitability for solving the problem, and describing emerging products entirely so that they can be manufactured in production. In addition to the pure generation of product-describing information, its management and coordination, are also essential for mechatronic systems’ development [57]. These two aspects, technical-physical development and technical management, should not be actively separated but must be understood as dualism that is indispensable for product design and development.

Notwithstanding, product design and development characteristically necessitate dealing with uncertain and incomplete information [56,58]. The reasons are manifold:

- Initially, the system of objectives for development represents a mental conception of the technical system to be developed, which is only successively completed and concretized in the course of development through the choice of solution principles [59].

- Working in interdisciplinary teams is necessary to provide knowledge from the different domains, but it also involves the risk of ambiguities since domain specific different terminologies are used, and model approaches from the domains can be interpreted differently [60].

- Development activities run concurrently for reasons of efficiency. Appropriate interface management is needed to provide sufficient information requirements for decision-making, not only from a formal, but also from an organizational and process perspective [61].

- The more functions a product provides, the more complicated it becomes in predicting requirements [62].

In addition, the uncertainties resulting from the design process itself, companies increasingly face challenges of operating in dynamic environments that are difficult to predict [63]. The acronym VUCA, which originates from the English-speaking region, summarizes the categories volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity [64]. The first indications of these specified categories can be found in the contributions of Warren and Burt [65]. Bennett and Lemoine [66] summarize the following explanations under VUCA:

- Volatility describes the effect of relative changeability, which is more pronounced and associated with instability and turbulence [66]. Fluctuations in influencing parameters can have a significant impact but can be described as a statistical problem for which strategies for dealing with them can indeed be derived [67,68].

- Uncertainty results from the fact that decision-making situations are difficult to predict. This phenomenon is considered a fundamental challenge in product development and ultimately characterizes these situations [69,70].

- Complexity is based on a system-theoretical perspective, according to which a system is composed of elements and relations between them and thus generates a system behavior [51]. A system is considered complex if the elements or relations between them cannot be objectively known or explained [71,72].

- Ambiguity means that no definite assertion can be made about information regarding the decision making process, which will impact the decision, even if it is based on a proper understanding of the system [66].

In summary, principle rules of action for product design and development can be derived from the need to deal with different characteristics and VUCA conditions that vary in intensity in respective environments [73]. These rules of action can be found in different process models in design and development [74]. Effective support must address both the technical-physical development processes and the management of product development projects. Agile methods address precisely this point and support effective management of design projects. In contrast to “traditional models”, agile models prescribe iterative cycles in which Increments prioritized and developed are repeatedly reintegrated for validation allowing customer needs to be reviewed more frequently [29,74]. However, a classification of agility is required to understand agile methodologies in specific contexts, as many mechanisms of action are undetermined [27].

3.2. Understanding of Procedural Models

Developers’ main interest and task is to solve technical problems. Methods and procedural models support these developers in this endeavor [3]. The research interest in design science lies in, e.g., method development, intending to support engineers in their work in the most effective and efficient way. The term method is well established in product design and development [75], and is e.g., defined as a “… planned, rule-based procedure, according to the specifications of which certain activities are to be carried out in order to achieve a certain goal…” [73] (p. 57). Therefore, methods are used in a supportive manner in the design process to carry out activities in a goal-oriented manner [76]. Within the design process, development teams usually have a large number and variety of methods at their disposal for synthesis and analysis activities, as well as for knowledge and information processing. Process models for product design and development map essential elements of a sequence of actions, which serve, for example, for planning and controlling product design and development processes [73]. Since the early 1950s, intensive work has been done on descriptive models to explain and represent design processes. Consequently, a large number of process models have emerged which reflect very different views of the product development process.

Procedural models summarize and convey design methodological findings from research and practice [77,78]. Wynn and Clarkson [78] view procedural models as a model type of process models. These models also ensure that essential steps in the process, from planning and task clarification to the conceptual design, the embodiment design, and the integration of found solutions in an overall solution, are supported [58]. Furthermore, procedural models also make a significant contribution to supporting communication between the domains and teams involved in the product development process [79]. Another classification approach distinguishes the procedural models regarding the scope into macro-level and micro-level [78,80]. In this contribution, we refrain from distinguishing between meso and macro levels, as performed in the article by Wynn and Clarkson [78].

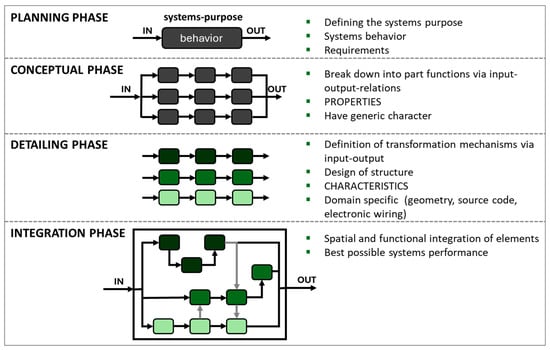

Macro-level refers to procedural models that focus on the temporal and logical relationships in design and development in a more holistic way. This approach divides the process into distinct phases, such as planning and task clarification, conceptual design, embodiment design, and detailed design, as outlined by Bender and Gericke [77]. The process is holistic, starting from the initial idea and culminating in a complete product description. Figure 2 represents an example. The concrete characteristics and details can vary based on the focus of observation. For instance, this variance can occur in different domains such as software development or design of integrated circuits. See also references [81,82] for further insights. Differences arise since these procedural models are domain specific. However, the basic logic always remains the same in conventional design. Finally, these procedural models reflect the characteristics of the design processes by offering methodological design actions for the comprehensive development and description of a product, enabling the representation of the product’s maturity level.

Figure 2.

General illustration of phase models representing logical or formal operations according to Paetzold [58].

For a specific application, a more detailed delineation is necessary for concrete applications and require industry- and company-specific adaptation and refinement in practice [83]. Engineering design points out that this process is an inherently iterative procedure [77]. Well-known procedural models, such as the V-model [84] or the spiral model [85], fundamentally follow the underlying development logic but sensitize to further aspects (verification/validation or change between synthesis and analysis) that characterize the product development process via the design of the trajectory.

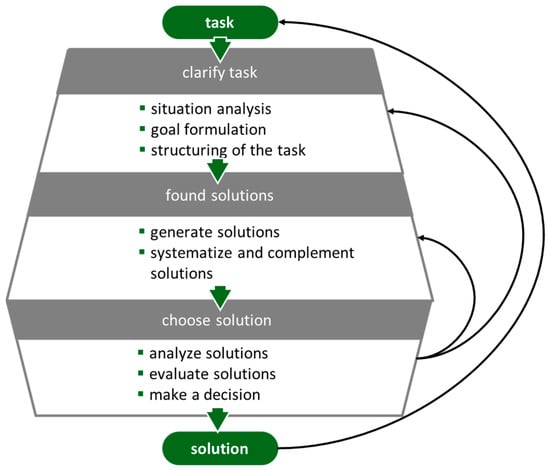

Micro-level refers to more individual process steps in a specific application context [78], such as the problem-solving cycle [4], which is illustrated in Figure 3. Psychological approaches to thinking, as outlined by Miller and Galanter [86], provide the basis for understanding how humans, including developers, tackle problem-solving. After defining the development task, the synthesis phase follows, seeking solutions and opening up a solution space. The proposed solutions need to undergo analysis and evaluation to determine their suitability for further development.

Figure 3.

The problem solving cycle according to Ehrlenspiel and Meerkamm [4].

Although the problem-solving cycle initially portrays a sequential approach, its very nomenclature elucidates its inherent nature as a cyclically recurring process. Within the problem-solving cycle, iterations can occur repeatedly because conflicting goals may arise or the solution space needs expansion to find a solution. Consequently, the constant switching between synthesis and analysis is required [4]. Seen from this perspective, the problem-solving cycle exhibits a fractal character; it not only explains the thinking process for accomplishing individual tasks but also finds application in the broader sense in every domain. For a more detailed discussion on process models and their organization, see Wynn and Clarkson [74,78]. These contributions highlight that the focus is on both supporting technical-physical development and their execution. Additionally, they contain coordinating elements for designing information flows and providing knowledge in technical management, ensuring effective and efficient product development by addressing the supporting methods and necessary knowledge base.

3.3. Project Management in Context of Design Methodologies

Design processes often vary due to a certain uniqueness in customer requirements and boundary conditions during the execution of product developments as projects. The actual scope for action and decision-making results from the context to be observed in each case [83,87], and implies individual personal experience. Moreover, design is a highly creative process that directly influences the flow of information and communication channels within a project [56]. Consequently, design projects use project management methods and procedural models, as every procedural model is an approach for managing a design project. The design project adapts and adjusts these approaches. According to the standard DIN 69901 [88] (p. 11) a project is defined as “an undertaking that is essentially characterized by the uniqueness of the conditions” in their entirety and is usually understood as a management task. In addition, other definitions exist, for example, the project as a temporary organization [89]. Specific techniques, methods, and tools primarily support the successful execution and completion of projects, which in this case especially means delivering a result in the set time frame under given resource and capacity constraints [90]. Accordingly, a project management system integrates individual methods within its entire process. These methods primarily support formal objectives like time and budget planning, while also defining roles and responsibilities. Analogous to the design processes, two types of dimensions can also be distinguished within the procedural models in project management: Macro-Level and Micro-Level.

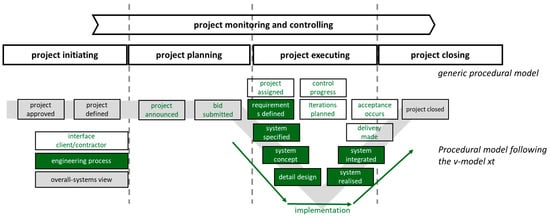

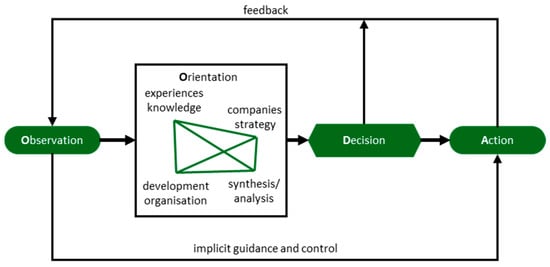

In project management, macro-level procedural models coordinate time logical relationships in project execution. A generic procedural model for project management, i.e., a breakdown into the essential activities, is shown in Figure 4. Concrete methods and tools can be assigned to this generic procedural model to support the project manager’s work. Furthermore, the micro-level utilizes management cycles, which depict four steps, as shown in Figure 5. In decision-making, the first step is to observe the situation (Observe) to obtain information and draw conclusions about possible interrelationships. Based on the perceived situation, orientation (Orient) takes place in preparation for the actual decision (Decide), which leads to concrete actions (Act). As a result, it is necessary to examine what consequences this action had. The cycle thus starts again with an observation phase.

Figure 4.

General procedural model for project management adapted from Webster Jr. et al. [91] and a specific elaboration adapted from Rausch and Broy [92].

Figure 5.

An adapted illustration of the OODA-Loop as a representation of a management process at the micro-level according to Stelzmann [93] and Boyd [94].

The challenge in project management arises from the fact that a reference object is required, in our case, the technical system to be developed, to which the planning can be related to [95]. However, the development of technical systems follows a logic (planning and task clarification, conceptual design, embodiment design, detail design), that must align with these approaches [96]. Consequently, procedural models emerged that can reflect the design and development logic and, on the other hand, meet particular project management requirements. Similarly to the procedural models of the design methodology, specific characteristics can be found depending on the application context, such as the v-model xt, which is used for projects in the public sector [92], the stage-gate model according to Cooper [97,98] or the models from systems engineering [91,99]. What all these procedural models have in common is that they are based on incremental working methods, i.e., decomposed into executable design tasks. In addition, verification points are defined (milestones, stage gates), which fundamentally support iterative work. These phase delimitations help in planning and controlling the results of the work. Furthermore, Lindemann [100] considers phase orientation as a means of quality assurance. The underlying assumption is that well-documented processes reflect best practices in design and development and ensure certain completeness in processing. This completeness is often interpreted as an aspect guaranteeing high-quality process results, i.e., the product. Completeness also includes a certain degree of documentation to present interim results and make them transparent, serving as proof of quality for the customer. Subsequent errors should thus be avoided at an early stage [101].

A comparison of design methodology and project management procedural models reveals the described and corresponding logical similarities, as again, any approach to managing a project inherently constitutes an approach to organizing product development efforts. In summary, no procedural model per se provides a holistic representation of the design process and the associated views that can provide comprehensive action support for product design and development. As a result, procedural models are usually rather generic and require adaptation to the specific design and development context [83]. Braun and Lindemann [102] further argue that an adaptation to the specific requirements of the design process is necessary (cf. tailoring), as the methods and procedural models should not be considered rigid entities. As a result, procedural models always map specific views of development. This view supports specific goals, but other aspects that influence the process are usually neglected.

3.4. Significance for Agile Product Design and Development

Agile approaches challenge traditional approaches, as these are assumed to be too rigid under certain contextual conditions (e.g., VUCA). Those traditional approaches are therefore also perceived as rigid and “heavyweight” [103]. In contrast, agile methodologies diverge from the perceived rigid project management sequence logic without questioning fundamental design and development logic. This deviation leads to the dissolution of constraints couplings. In this respect, agile product development teams perform project management tasks. In today’s context, product development departments typically operate as multi-team organizations, where agile methods are often designed for individual teams [34]. The possible scaling of agile teams requires additional coordinative roles (e.g., coordination mechanism [7]), which results in a complex network of mechanisms of action that can only be addressed by breaking down the mechanisms of action of agility first.

Thus, the systematic approach to product design and development merges with project management and must be seen as dualism. This dualism is fluid in industrial application and theoretical in the article. Different perspectives on the same object of consideration, specifically the design of a product, often lead to conflicting priorities in processing the actual tasks related to it. Agile project management methodologies and frameworks, e.g., Scrum, do not consider the specific conditions and constraints of product design and development. For instance, the Scrum Guide defines the rules for a single Scrum team but offers no guidance on scaling or addressing non-functional requirements, although those encompass the criteria for quality assurance and the necessary market knowledge [104].

Therefore, selected agile approaches are specifically and extensively adapted in industrial practice based on experiential knowledge (e.g., from consulting) [11].

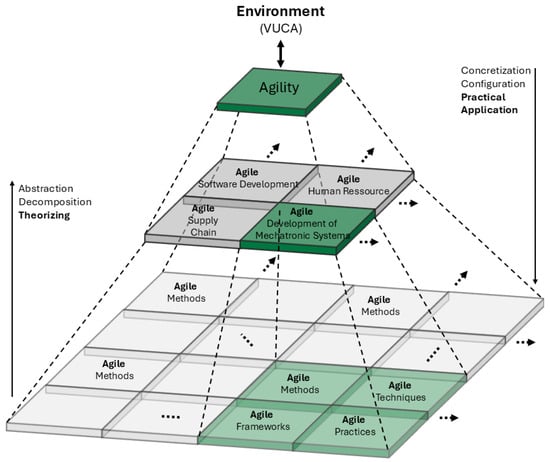

To facilitate this adaptation process, practitioners need to understand the theoretical construct of agility (e.g., structural elements and their functional mechanisms). By providing such an understanding, practitioners can both adapt and fundamentally configure agile methods to suit specific needs. Figure 6 depicts the underlying concept.

Figure 6.

Illustration of two approaches in order to adapt agile approaches and methods: First, direct transfer between domains; second, the theorization of agile elements and mechanisms to enhance an informed understanding or configuration of context- and situation-specific approaches. Arrows indicate additional domains or aspects for consideration.

For instance, the adoption of agile methods from software development to hardware development does not necessarily guarantee the desired outcome, as the inherent mechanisms may not fully unfold the intended effect in a different context. Therefore, the underlying cause-and-effect mechanisms must be to avoid failures regarding the adoption and adaptation of agile methods.

4. Results: Clarifying the Concept of Agility—Interpretation and Classification in Product Design and Development

In the context of a development organization, agility can be interpreted as an attribute whose achievement can be strategically justified. In order to achieve agility from a systems-theoretical perspective, according to Haberfellner et al. [105] it is necessary to examine the structural elements. Depending on, e.g., various VUCA conditions, agile behavior may be suitable in specific situations.

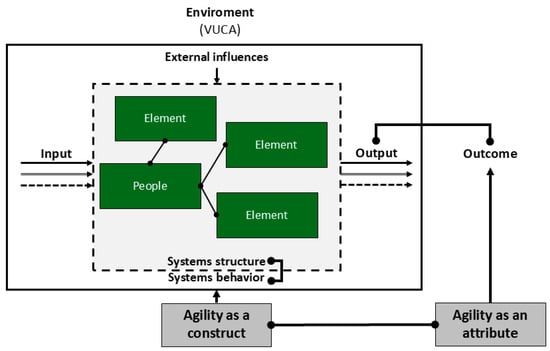

However, agility may not necessarily be required depending on the nature of change, as other approaches may prove equally effective. Under the premise that internal and external disruptive factors attain certain manifestation (e.g., a particular level of intensity) within a VUCA environment, we argue that agile behavior is suitable. Thus, as Figure 7 illustrates, we could perceive agility as an attribute and also view it as a construct. The investigation of these two different perspectives is the aim of the subsequent sections.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the idea of agility in context simplified by using systems thinking according to Haberfellner et al. [105]. Each element represents a function mostly corresponding to its intended purpose [105]. Inputs and outputs can be characterized by different parameters [77]. Agility as an attribute is linked to agility as a construct by using the Output-Outcome-Value-Impact model from Zwikael and Huemann [106].

4.1. Agility as an Attribute

Agility appears to be an essential attribute to remain capable of acting under volatile and changing conditions [107]. Conversely, equating the statement that a company is agile involves acknowledging that the company is aware of these dynamic and unstable conditions and bases its business activities on them. In this respect, we address agility as an attribute from different perspectives of knowledge domains in this section. Tseng and Lin [108] (p. 3694) describe agility as the “Business Paradigma of the 21st Century”. Additionally, the literature defines agility from various perspectives. Hence, it seems important to first analyze the term agility to concretize it in the context of product design and development in order to derive utilization. From the word’s meaning, the noun agility is used to describe a certain ability to move, which is currently equated with responsiveness in the context of design and development. In this context, people often perceive agility and flexibility as synonymous and interchangeable terms, even though differences in various aspects exist [47,109,110,111,112]. Several investigations have undertaken this, though a uniform consensus has yet to emerge [45,113,114]. Ozkan and Gok [47] argue that the more definitions focus on certain aspects, the more likely organizations will deviate from that definition. Still, concerning the capabilities in the entrepreneurial context, agility in product design and development can be propagated as a situation-oriented, i.e., dynamic, approach. A dynamic approach contrasts with a plan-driven approach [62]. In a plan-driven approach, ideally, there should be no deviation from the planned course of action. However, there is usually a need to deal with change, and the reasons are manifold [78,115]. Therefore, Wynn and Eckert [115] distinguish between different perspectives of iterations and point out that agile design projects use deliberate iteration structures within the incremental development of products. Drawing upon the assumption that iteration and incremental development cannot be the only differentiator, a more profound comprehension of agility is required. Various sources were gathered to gain a better understanding of the meaning of agility and to identify distinctions. This reflection is evident in the multitude of published definitions of agility compiled in a multidisciplinary literature review, which may hold relevance in the context of product design and development. Table 2 summarizes these research results chronologically while acknowledging that it does not claim completeness.

Table 2.

Definitions of agility from different perspectives and disciplines addressing outcomes.

The first definition, referred to as corporate agility, is reflected in the work of Brown and Agnew [116]. The authors state that agility involves more than just flexibility and criticize that managers usually place significantly more emphasis on optimization than effectiveness. In the context of business management, further definitions and interpretations related to business agility [145], enterprise agility [131,146] as well as organizational agility [10,112,138,141] can be found. In the context of organizational development, discussions involve the idea that agility can be both a capability and the result or outcome of an organization’s behavior [10]. Agarwal et al. [144] further describes that agility is fundamentally necessary to manage the constant change within cross-sectional industry and makes a connection to Industry 4.0. Various definitions exist to describe agile manufacturing as a strategy for coping with the competitive market despite changes in requirements [117,121,147,148]. In context of agile supply chains agility is portrayed as a crucial element for sustainable competitive advantage [122,143,149]. In the field of Systems Engineering, Haberfellner and de Weck [127] make a distinction by asserting, on the one hand, that a product can inherently possess agility, as opposed to the process of developing that product. In both software development and product development, efforts have been made to define agility, to sharpen understanding [14,44,47,48,137,140,150].

Despite the various underlying perspectives, an analysis of these definitions and concepts reveals shared aspects that will serve as the foundation for building theory. One of the essential statements is that agile methods support embracing change instead of avoiding it [150]. Virtually all the definitions listed in Table 2 address the changing environment that requires a response without specifying the types of changes involved. Furthermore, most authors also emphasize the element of rapid responsiveness.

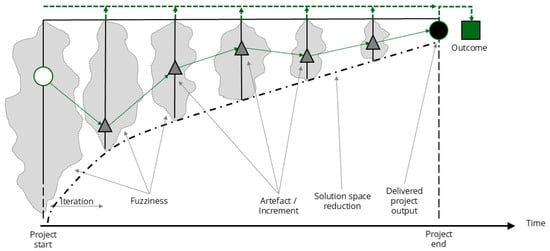

Unpredictable and unanticipated changes further characterize the changing environments [117,118,119,128,133,137]. Various authors emphasize different aspects that deserve particular consideration, such as value creation [138], market opportunities [123], technical changes [130], customer needs [133], assessing the validity of a project plan [140], changing requirements [44,142] and performance [112]. Other authors, such as Kidd [117], Conboy [45] as well as Attar and Abdul-Kareem [141] further contribute nuanced characteristics, such as the proactivity of responsiveness, whereas Böhmer et al. [137] highlights the possibility of not only seeing change as a challenge but also taking advantage of the opportunities it presents. From the authors’ perspective, agility consists of the ability to react to unexpected changes but also the active ability to concrete and adjust the objectives for the product benefit with the customer continuously (preferably at the highest possible speed) as visualized in Figure 8. In this context, the primary emphasis should be on addressing the unstable and less firmly established requirements in the evolving environment. Nonetheless, it is also essential to take into account various external and internal factors. These aspects include especially the assumption of a certain agility in the face of incomplete and unspecified requirements of the product, whose fulfillment is the objective of development in order to satisfy needs. Suppose flexibility is understood as an attribute that allows systems to adapt within predefined parameters [112,151], or to respond to change within a specific range through a robustness optimization process [152]. In that case, agility surpasses this ability by permitting adaptations beyond these boundaries. Similarly to Conboy [45], we further argue that agility considers ongoing and unpredictable change.

Figure 8.

Relationship between solution space and project progress of an agile project within product design and development.

Figure 8 illustrates the possible solution space over time from the project’s start to end. In the presentation, we operate under the assumption that fuzziness exceeds the usual parameters to be considered.

The solution space is characterized by a degree of openness since insufficient information is naturally available in the early phases of planning and design, or because this information is only obtained through specification during product design. The space size mentioned is determined not only by different usable technologies and solution principles, uncertainties about their availability or usefulness, but also by how precisely the customer’s needs can be formulated or about which solution knowledge can be brought into the requirement formulation. In this context, one could initiate a discourse regarding whether the customer’s needs align with their desired imaginative result. We argue that this variability within the requirements specifications is an aspect that should allow for changes beyond a predefined extent, especially when designing innovative products. As the project progresses, the target image becomes more precise, restricting the solution space and thus also reducing the decision diversity. As a result, a discrepancy between the artefact realized within the technical space of possibilities and the problem space perceived by users can be continuously minimized, resulting in a continuous improvement in meeting stakeholder and customer needs.

In a nutshell, we derive implications from the various approaches to define agility according to Table 2 within the context of product design and development. Without intentionally proposing a condensed definition, the following recommendations for action can be used to implement agile product development while representing core concepts of agility:

- Incremental development reduces complexity by breaking down a larger system into manageable features. The breakdown into experienceable features ensures a focus in development organizations and enables regular, early delivery and frequent validation directly by the customer.

- Breaking down design tasks into smaller steps generates a higher frequency of intermediate results, aligning with the inherently iterative procedure preferred in product development. The increased frequency of verification provides objective proof for the developed technical artefacts to meet the design task requirements. Necessary adjustments must be made in accordance with the requirements specified.

- Responsiveness as a functional focus to increase benefits with appropriate measures under a competitive and reasonable speed by assessing opportunities and risks in turbulent environments (not necessarily) and due unstable requirements that exceed predefined parameters.

- High-frequency customer integration reduces misunderstandings and misinterpretations of needs. Furthermore, the objectives of the design task are repeatedly checked against actions to fulfill the needs. They are adapted, concretized, and explored if necessary to align with the needs to create value. Integrating stakeholders increases transparency in the design process and the relevance of the product for the customer. Additionally, the customer actively participates in learning processes and assesses solution options presented within their context. The involvement helps them to formulate their problems better and articulate their needs.

- Empowered collaboration not only simplifies coordination and supports communication for finding solutions but also helps to provide a broad knowledge base necessary for accomplishing tasks. Therefore, teams should have cross-functional capabilities and be self-organized to promote transparency, decision-making, and the team’s learning capacity.

4.2. Agility as a Construct

The considerations on agility as an attribute describe an observable behavioral pattern of a development organization in order to act adequately in volatile and dynamic environments. In terms of systems thinking, such behavior must be anchored in the structures of the development organization. The word ’construct’ refers to something that has been assembled or built. Derived from Latin, ’construct’ roughly means ’with structure’. In this article, we emphasize that systems theory for socio-technical systems strives to explain and analyze non-linear behavior. The system is subsequently more than the sum of its elements and thus cannot be explained by reductionist thinking [153]. Therefore, some scholarly publications have already explored the construct of agility, articulating both the existence of this issue (cf. [10,44,45,49,143,154,155,156]), and asserting that the concept of agility remains inadequately theorized [111]. Consequently, the explicit structure remains unclear and lacks explicitness. As a result, naming elements is not sufficient to describe their order and relationships to each other related to the construct. An underlying factor contributing to this phenomenon is the absence of precise construct delineation and differentiation from closely related constructs [157]. The different authors refer to the multidimensionality of agility and emphasize the importance of researching how agility can be achieved as a theoretical concept. Thus, Conboy [45] describes that components can only contribute to agility if they consider aspects such as learning from change and reaction to change. Furthermore, the author refers to the fact that these elements must be continuously available. Lee and Xia [49], Batra et al. [155], Meier and Kock [10] examine individual aspects of the construct by means of qualitative and quantitative investigations. Batra et al. [155] as well as Meier and Kock [10] point out several dimensions, but they are rather generic and not adequately related to structural aspects within the dimension to enhance the capability. Furthermore, they do not answer the question of how companies can be concretely supported methodically to achieve agility. Connections between different dimensions are not precisely elaborated or explained. We argue that with the help of a conceptual view from a Systems Thinking perspective, relationships of individual elements could become more visible and explicit. Furthermore, we contend that based on this premise, a more theoretical perspective could offer enhanced methodical support, as adjustments should also be more comprehensible. Drawing upon the fundamental concepts proposed by Haberfellner et al. [105] system behavior refers to observable or measurable activities, where it may not be immediately evident why the system behaves as it does (black box). To elucidate such behavior, it is essential to analyze the underlying mechanisms within the system (both grey box and white box). In this context, the system’s structure holds intrinsic significance, as its constituent elements and relationships form a construct, thereby revealing an inherent order [105].

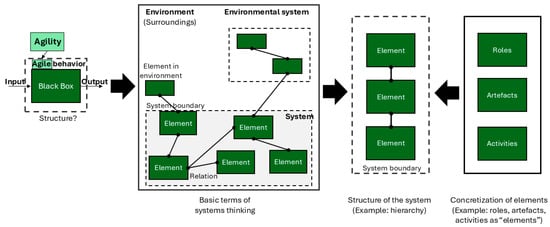

To enhance the understanding of the agility construct, we present fundamental concepts of system thinking as shown in Figure 9. Consequently, we have performed a modeling process in a simplified way. The mentioned process involves creating a structure by modeling elements and relations in a particular order. Figure 9 presents a visual representation depicting the initial problem and the discrete sequential steps comprising the system’s theoretical approach. Additionally, a hierarchical structure is modeled, supplementing the basic terms. In a subsequent step, it is possible, for instance, to incorporate additional elements (e.g., roles, artefacts, and activities) or delineate specific relationships, as depicted in the right-hand portion of Figure 9. Thus, we argue that agility currently represents a black box (or at least a grey box), and researching this black box is necessary to attain a better theoretical understanding of achieving situation-specific agility. The dimensions of agility mentioned by different authors can also be modeled, for example, as various boxes within the structure.

Figure 9.

Initial problem and basic terms of systems thinking adapted from Haberfellner et al. [105]. Simplified example of a systems structure and concretization of elements to unpack the black box of the construct of agility. The specified elements presented are not comprehensive.

However, we assume that systemic investigation needs further exploration and possible dimensions already postulated need to be specified.

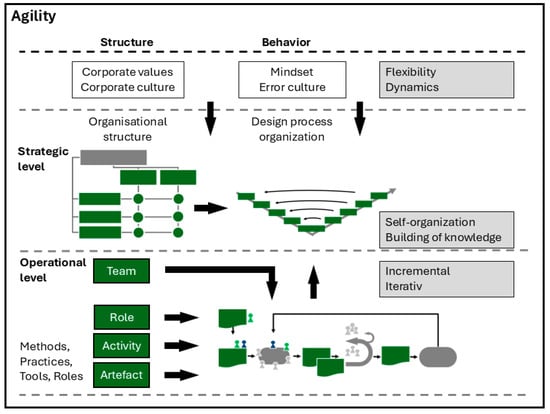

Figure 10 shows an exemplary construct that considers agility from the specific perspective of product development. The starting point comprises various elements such as artefacts, roles, and activities, which vary in nature. These elements are further contextually combined into subsystems and processed for, i.e., the incremental and iterative work in product development. Thus, the context is decisive and must be considered when agile behavior is to be realized to an appropriate degree and in a purposeful manner. Furthermore, the human actors (e.g., engineers, designer and managers alike) represent a critical factor whose behavior cannot be reliably predicted and thus remains challenging. Accordingly, elements that influence their behavior in a goal-oriented and purposeful manner are equally important.

Figure 10.

Classification scheme for illustrating the causal relationships of agility in product development, inspired by Atzberger et al. [113], Haberfellner et al. [105] and Lindemann [73]. The black arrows illustrate the dependencies and relationships between individual elements and show the process of holistic aggregation.

The procedures and methods used at the operational level must be integrated and aligned with design methodologies at the strategic level [73]. Therefore, it seems essential to integrate agile approaches into the structural and process organization of the company to realize the effects of agility (self-organization, learning within the organization). The implementation of agile ways of thinking also requires the consideration and design of overarching values and principles, which then manifest themselves in effects such as mindset and error culture [10]. The cultural aspects associated with this consistently address the values and principles of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development. However, cultural aspects also influence human behavior, as they provide inherent guidelines for people as decision-makers to improve project performance [145].

The skills and competencies required for the actual technical physical development, i.e., the expertise needed to solve technical problems, are assumed to be a given. In order to implement agility in manufacturing companies in general and in the design process in particular, it is necessary to derive concrete procedures, methods, and practices from the values and principles outlined in the previous chapters. These guidelines will guide and support product development teams in agile work at the operational level. These agile methods must be reconciled with the basis derived from the attribute perspective of agility. Scrum offers an event called Sprint Review that allows feedback from customers after the sprint [158]. Conversely, this means presenting a mechanism that allows for the adjustment or correction of the situation. This perception of change seems essential for initiating a response and should therefore play a crucial role at a specific point within the construct of agility. This is illustrated in Figure 10. As mentioned earlier, supporting product development teams at the operational level requires overarching strategies as long-term guidance that prepares and guides the achievement of fundamental goals [73].

As depicted in Figure 10, this classification structurally aggregates individual elements, promoting agility in a context- and situation-specific manner. Figure 10 further exemplifies that agile product development extends beyond the implementation of Scrum, indicating a dissociation between agile practices and a necessary alignment with Scrum. Additionally, the systems theory approach can be used to argue why Scrum and, e.g., agile (product development) cannot be synonyms because they aggregate differently, which leads to the conclusion that Agile and Scrum are not the same object. This extension is necessary because Scrum and its application do not inherently result in agility. Scrum addresses cultural aspects to a limited extent but inherently assumes the internalization of the values and principles of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Here, it is important to emphasize that Scrum is just one of the viable examples. In addition to Scrum, other agile frameworks and methodologies exist. For further consideration, Scrum is used as an elementary constituting and operationalizing methodology, which includes various individual methods, such as Product Backlog Refinement, Sprint Planning, and Daily Scrum, i.e., for planning and executing activities, coupled to form a consistent procedural model.

Scrum was chosen because the emergence and development of agile methods, especially in the early days, was driven pragmatically, out of concrete application, and not necessarily oriented to design methodological considerations. Scrum is based on empiricism and thus describes the experiential knowledge of the founders behind it. Sutherland [17] emphasizes that the way one operates, particularly in the field of software development, was inadequate. The displeasure primarily addresses a need for more understanding of overloaded planning, especially when the ability to forecast is insufficient, resulting in a massive waste of resources in development. From this perspective, Scrum has evolved as a framework, but its essential elements reflect the values derived from research and development in dynamic environments. From the authors’ point of view, these elements need to be made more concrete and more precisely related to one another. Applying Scrum, based on the structural components, including other constituting elements not specified within Scrum, will lead to the desired agility as an attribute. Therefore, applying the system structure under the influence of actors and other aspects generates a system behavior intended to achieve the desired agility to achieve specific objectives. However, as indicated, a system structure does not automatically guarantee the desired agility. On the contrary, we contend that a system structure may be sufficient to facilitate agility but is not necessarily so if other dimensions are neglected. From the authors’ perspective, this relates to inherent non-explicit aspects requiring further exploration.

Consequently, several agile methods and practices have evolved in the past, designed to align with the values and principles of the Manifesto of Agile Software Development. Agile methods are characterized primarily by high frequency iterative, incremental, and evolutionary approaches and require the team to develop increments within defined time intervals that validate customer requirements. By allowing the customer to experience these, the development team receives resilient feedback for the subsequent iterations [158]. The most popular agile methods are Scrum and eXtreme Programming (cf. [9,11,159,160]. Condensed and summarized descriptions of agile methods can be found in Abbas et al. [161], Abrahamsson et al. [162] and Dingsøyr et al. [20].

5. Discussion

As outlined in the results, various approaches exist for conceptualizing agility. The first subsection aims to position the conceptual approach presented in this article. The second subsection addresses the implications for product design and development.

5.1. Positioning of the Proposed Conceptualization of Agility for Product Design and Development

Existing perspectives on agility, as presented in the literature (see Table 2), provide a sufficient understanding of what agility aims to achieve. Thus, the purpose of being agile is reflected in the definitions proposed by various authors. The intended outcome of agility is well understood and established across disciplines (cf. Table 2). Therefore, we did not aim to propose a new definition in this article. We have merely highlighted and synthesized the commonalities to establish a foundation for the construct. The construct of agility, as well as its explicit linkage to established outcome perspectives, is still insufficiently understood and represents the novelty of this article. To highlight the novelty of our contribution, we focus on prior work that includes relevant aspects of our conceptualization of agility.

Table 3 represents a comparative overview, outlining both the foundational contributions identified within the agility literature and the novel contribution introduced through our conceptualization. Our approach focuses on configurability and the operationalization of elements for practical utilization while acknowledging the pluralistic perspectives of other authors.

Table 3.

Comparative overview of the concept’s novel contribution in relation to selected prior work on agility.

5.2. Implications of Agility in Product Design and Development Considering Design Methodologies

A design methodology maps the design process “… that specifies in more or less detail the activities to be carried out, the relationship and sequencing of the activities, the methods to be used for particular activities, the information artefacts to be produced by the activities and used as inputs to other activities, as well as (tacitly or explicitly) the paradigm for thinking about the design problem and the priorities given to particular decisions or aspects of the design or ways of thinking about the design” [163] (p. 11), from the idea to the complete product description. Thus, it provides a framework for action support. The methodology aligns inherently with the project management approach tailored for a specific design project. The concept of agility and its postulated representation in context of product design inherently challenge established project management procedural models by emphasizing the necessity of feedback loops, occasionally at a required pace (e.g., sprints) to create value more effectively. This questioning coincides with an analysis of the environment and stakeholders within the respective design projects.

Existing conventional approaches address changes by implementing iterations (e.g., re-design). These iterations fundamentally enhance the adaptability (e.g., increased flexibility) of conventional procedural models. However, these procedural models still adhere to the predetermined structuring of individual phases, requiring the early establishment of an overarching plan. For instance, target descriptions form the starting point for product development, establishing fixed requirements that must be precisely and efficiently implemented throughout the product development process [164]. For this purpose, a plan is defined in advance as a basis for action. The resulting plan within product design projects relies on the asserted completeness and accuracy of requirements and specifications. An inherent characteristic is that they are considered invariant in quantity and time throughout the product design project. The aim is to minimize potential deviations from defined objectives and the intended execution. Verification points in the form of milestones (cf. stage gate) define phase sections at which the achievement of objectives or the fulfillment of requirements is checked. From a theoretical point of view, flexible processes allow changes within predefined parameters [112]. This process differs from processes that respond to completely unconsidered and unknown parameters. In this context, changes are often determined as different variations in iterations, with different effects [115]. This way of thinking assumes the predictability of needs and accepted solutions, which are not inherently given due to the characteristics and peculiarities of the product development process. However, there are also many product design projects in which these assumptions are absolutely legitimate. Agility in the context of product design and development resolves a forced linkage by implementing holistic scanning frequencies that follow a logical sequence of content. In contrast to the described corrective iterations [115], this results in progressive iteration [115], as individual features are continuously validated with the help of the customer. From the perspective of a particular type of adaptability, agility represents a specific manifestation that differs from flexibility, for example. Thus, adaptability relates to specific objectives, and there are various possibilities for adjustment.

Regarding agility, this leads to breaking the advocated rigid sequential logic of existing conventional procedural models. As a result, project management tasks need to be reinterpreted, and roles redefined. What becomes evident is that the responsibilities of design teams extend beyond solely technical function development. In the realm of product design and development, it is imperative to transcend the narrow confines of solely creating solutions for designated development tasks. Doing so facilitates the symbiotic evolution of both problem and solution domains throughout the developmental trajectory. It also acknowledges the distinct constraints intrinsic to discrete physical products in industrial practice [165]. This enables the readjustment of objectives to become a central component of the development task, which reduces the effort required for risk assessments and forecasts and allows the focus to be placed on solving the problem. This problem-solving is based on an equal understanding of both management and the actual execution of tasks within the design team. Consequently, we can view agile product development as an appropriate strategy. Understanding the situation involves evaluating the degree of maturity or the solution space, which undergoes repeated validation through consultations with customers and stakeholders. Agility as a specific structure within design methodology enables the ability to concrete and adjust target ideas for the product benefits with the customers continuously and at high speed. Takeuchi and Nonaka [18] already pointed out the importance of speed and adaptability concerning the commercial development of innovative products. Agile product development methods now provide the basis for implementing agility to change the process responsively and bring about adjustment. So-called moving targets, i.e., changing development goals and requirements, are no longer perceived as a threat but as an opportunity to adapt actions to changing boundary conditions instead of working off preconceived plans. This perspective adjustment is accompanied by the aim that the solution space is deliberately kept open in the early phases of development (see Figure 8), especially concerning the evaluation of development boundary conditions. However, this does not preclude the development from being based on a clear description of objectives that reflect customer needs and requirements.

The premise of the target description, however, should acknowledge that the customer may not necessarily be aware of all existing or future technologies or be unable to articulate their needs precisely. This premise redefines the customer within the design project, eliminating the necessity of setting requirements throughout the entire duration. Above all, it is also a matter of not controlling and reacting to risks based on uncertain assumptions. Instead, the goal is to optimize forecast reliability by permanently reviewing and scrutinizing framework conditions to make situation-adapted decisions that increase the product’s maturity and limit the solution space. However, this dissolution necessitates a reevaluation of roles, activities, and events within the agile paradigm, leading to confusion [28]. This reevaluation stems from transferring project management tasks to the development teams. Theoretically, these confusions can be resolved by reconsidering agility from a new perspective, viewing it as a system aiming to achieve goals under certain conditions effectively. The influential network of incremental and iterative work, teamwork, and the strong integration of customers and stakeholders can justify the essential benefit of agile methods and agility for dealing with the challenges above. In addition to the permanent validation of the goals and the possibility of repeatedly reviewing, refining, and adapting the product development process, giving responsibility to the team members is advantageous [22]. This direct involvement of team members in decision-making processes increases their commitment to the product design and development task but also creates new ways of formal and informal communication [7]. The developer as a human being is thus once again increasingly perceived and promoted as part of the data and information flows within the design process. This perception increases the transparency of decisions in product design. The developers perceive the accompanying self-organization as supportive and appreciative [166]. Nevertheless, further examination is needed regarding agility concerning product design and development so that it can be theoretically grounded and implemented appropriately in terms of utilization.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

This article explored a dualistic perspective on agility within the context of developing mechatronic systems. We have shown that utilizing agility can be theorized and conceptualized through a systemic approach. We complement research on agility (cf. Table 3 or [10,44,45,48,143]) and provide an initial methodologically consistent framework within product design and development to achieve agility. Considering agility as an attribute should be contingent upon the specific circumstances within the development of mechatronic systems. Therefore, agile design methodologies effectively complement and extend conventional design methodologies by offering solutions for changing development situations. However, implementing agile elements for dealing with, e.g., unexpected changes is not a new concept [13,154]. From our point of view, the central aspect is support based on an attribute perspective of agility and not on similar attributes, e.g., flexibility. We assume that the product development processes of manufacturing companies have already implemented agile elements where these are required. Hybrid approaches appear important and more relevant in the future [11,43]. The context-specific integration of agility into the procedural models of product development allows a synergetic linking of the two essential tasks of product development: technical-physical development and technical management of the development situation considered. Thus, it supports effective product design and development but also shows ways to deal with uncertainties and incomplete information outside predefined parameters. The terms flexibility and agility used synonymously in practice must be differentiated. By highlighting two perspectives, namely the attribute and the construct, agility can be conceptualized and contribute to the enrichment of design science.

Further theoretical research is required to realize the advantages in the context of developing mechatronic systems. Many companies are experimenting and working with context-specific adaptations and using them purposefully [9,11]. The design science should provide robust theoretical models that elucidate the practical application and support designers, as indicated by Gericke et al. [3] and Hevner et al. [2]. Developing a comprehensive descriptive, explanatory model enables the explication of relationships and facilitates the generation of minimum prescriptive models for utilization. Understanding the means-end relationships and cause-and-effect relationships supports development organizations in implementing an appropriate degree of agility for their specific situations. However, these mechanisms of action within the procedural models and the methods used still need to be sufficiently understood to explain these effects and thus make them usable for method development and adaptation. A preliminary starting point lies in the relationship between the attribute and the construct of agility, as shown in this contribution. The research and examination of these interdependencies (e.g., structural elements, configuration of the elements, and the actual resulting behavior) requires intensive collaboration between disciplines such as organizational sciences, social sciences, organizational psychology, and product development. Collaboration is required to explain the phenomena holistically and make them usable for method development, e.g., in supporting cross-team coordination to a minimal extent [7,167,168,169], as procedural interactions integrate the collective series of dependent tasks [170].

As a result for a future research program, we suggest holistically investigating various agile elements and their mechanisms of action from different perspectives. Enhancing this comprehension will support us in obtaining a better understanding of the construct of agility, leading to improvements in its application. As noted by Gericke et al. [3], a profound understanding is crucial to adapt it to the practitioners’ needs. Furthermore, aspects of education concerning the engineers of the new generation are also worthy of investigation. We invite scholars, researchers, and practitioners alike to join us in investigating these perspectives on agility or to discuss related constructs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P.-B., M.M. and S.W.; methodology, K.P.-B., M.M. and S.W.; formal analysis, K.P.-B. and M.M.; investigation, K.P.-B. and M.M.; resources, K.P.-B. and S.W.; data curation, K.P.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.P.-B. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, K.P.-B., M.M. and S.W.; visualization, K.P.-B. and M.M.; supervision, K.P.-B. and S.W.; project administration, K.P.-B. and S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for this article are not readily available because the data are processed exclusively for the annual studies. The purpose of the annual studies was to provide a current overview of agile development of physical products in the German-speaking countries, focusing on motivations, potentials, applications, transitions and challenges. The processed data presented in this study are included in the respective publications and will be made available on request. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere appreciation to all anonymous participants who contributed to the surveys across the studies. Furthermore, we want to express our gratitude to those who have consistently worked on the longitudinal study series. Finally, we are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Stefan Weiss was employed by AGENSIS Munich. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Papalambros, P.Y. Design Science: Why, What and How. Des. Sci. 2015, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.R.; March, S.T.; Park, J.; Ram, S. Design Science in Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, K.; Eckert, C.; Campean, F.; Clarkson, P.J.; Flening, E.; Isaksson, O.; Kipouros, T.; Kokkolaras, M.; Köhler, C.; Panarotto, M.; et al. Supporting designers: Moving from method menagerie to method ecosystem. Des. Sci. 2020, 6, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlenspiel, K.; Meerkamm, H. Integrierte Produktentwicklung—Denkabläufe, Methodeneinsatz, Zusammenarbeit; Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: München, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, A.; Behrendt, M.; Klingler, S.; Reiß, N.; Bursac, N. Agile product engineering through continuous validation in PGE—Product Generation Engineering. Des. Sci. 2017, 3, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzberger, A. Agility in Mechatronics Unveiled—A Value Model for Describing the Interdependencies of Agile Development in Mechatronics; Universität der Bundeswehr München: Neubiberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schrof, J.I. A Coordination Perspective of Agility in Automotive Product Development; Universität der Bundeswehr München: Neubiberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.S. Towards a Method for Agile Development in Mechatronics; Universität der Bundeswehr München: Neubiberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]