Abstract

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) projects have been the focus of extensive research in recent years. To overcome the challenges associated with these types of projects, one emerging and relatively unexplored stream of research has examined the application of agile project management (APM) in ERP implementation contexts. Despite its growing popularity, APM adoption remains complex, risky, and not yet fully understood. This study focuses on the critical role played by the customer in such projects, as it can either foster or hinder agility. A lack of customer collaboration can often be linked to the customer’s organizational culture (OC). Thus, this study aims to investigate the specific relationship between the customer’s OC and project agility in ERP implementation projects within small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). To conceptualize OC, we adopted the Competing Values Framework (CVF), which distinguishes four cultural types: Clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market. Data were collected through an online questionnaire administered to 172 ERP end-users from Canadian SMEs who had participated in their organizations’ ERP implementation projects. The analysis was performed using SmartPLS version 4.1.0.9. The results confirm that customers characterized by a clan, adhocracy, or market culture positively influence project agility, while there was no significant effect of hierarchy culture on project agility. This study addresses several gaps in the literature and offers practical implications. The findings support the idea that vendors should better frame and justify introducing APM in ways that align with each customer’s cultural characteristics within ERP vendor–customer relationships.

1. Introduction

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems are standardized software packages designed to integrate an organization’s core business processes, encompassing functions such as finance, project management, human resources, logistics, and customer relations [1,2]. Numerous benefits have been reported in the literature regarding ERP implementation, as such systems enable firms to enhance their overall performance through improved decision-making, better customer service, and greater process efficiency [1,2]. They also facilitate seamless data integration across departments and functional areas through a single, centralized database [1,3]. Due to their high level of complexity and associated risks, ERP projects have been the subject of extensive research [4,5].

In the broader field of information technology projects, one major stream of research that particularly emerged to address the risks and challenges associated with IT projects has focused on the “agile way of working” [6,7]. Agile project management (APM) gained momentum after the publication of the Agile Manifesto, which formalized a set of principles and values considered the essence of agile methods [8,9,10]. Examples of such methods include Scrum and Extreme Programming (XP) [8,9,10]. Such methods were specifically designed to respond to dynamic environments characterized by uncertainty and change, adopting iterative and adaptive life cycles while emphasizing the human dimension of projects [11,12,13]. They differ from more traditional, plan-driven approaches, such as the waterfall model, which are based on a sequential process in which changes are minimal and the environment is largely predictable [14]. Plan-driven approaches are typically change-resistant and rely on strict adherence to predefined plans [15], contrasting with agile approaches.

A growing body of research has identified numerous benefits associated with APM. In particular, empirical studies have demonstrated that agile methods contribute to greater project success across several dimensions, including overall performance and stakeholder satisfaction, thereby confirming agility as a significant predictor of success in information systems development projects [7,16].

APM has rapidly become commonplace in the information systems development field [6,7], and the adoption and use of such approaches in the specific context of standard software package implementation projects, such as ERP projects, are no exception to this trend [17]. Consequently, scholars and practitioners have recently begun to explore and report on their application in such contexts [13,17,18,19]. However, this line of research is still in its early stages and remains largely underexplored, having recently been the subject of several calls for further investigation [13,20,21].

Despite its growing popularity, agile adoption remains risky, complex, and not yet fully understood [13]. There is still a recognized need for a deeper understanding of how APM is adopted within organizations, including the challenges faced, the factors that contribute to its success, and the contextual conditions surrounding its adoption [13]. The literature further highlights that multiple internal and external factors should be considered when determining the most appropriate project management approach, which also holds when introducing APM [15,22]. Among the various contextual factors, organizational culture (OC) has emerged as a critical determinant in choosing and adopting a project management methodology [8,23]. It is increasingly recognized as a key research topic in understanding how organizations embrace agility [8]. The literature broadly indicates that OC significantly influences employees’ collective behaviors toward their work [24]. It reflects the shared values, norms, and underlying assumptions that guide how individuals or groups of individuals think and act within an organization [22,24,25,26]. Organizational culture influences internal behavioral aspects such as decision-making processes, problem-solving strategies, innovation practices, social interactions, and control mechanisms, as well as how the organization engages with its external environment and stakeholders [24,25,26]. Therefore, OC can significantly shape how projects are managed and, consequently, how APM is adopted and implemented within organizations [24,27,28].

Although OC is widely acknowledged as an important factor, research examining its effects on agile ERP implementation remains limited [29]. Existing studies exploring the relationship between OC and agility [8,22,24,26,28,30,31,32,33] have mainly focused on custom software development projects, rather than on standard software package implementation projects (such as ERP systems). Moreover, these studies have examined the impact of development team culture on project agility rather than that of the customer organization—which, in ERP projects, serves as the client in a vendor–customer relationship. From a broader perspective, the customer’s role remains largely overlooked in the literature on agility, even though it plays a crucial part in shaping project agility [13,34]. Indeed, customers can either facilitate or hinder the adoption of agile project management (APM) [7,13,35,36]. In this regard, factors related to customers, such as organizational culture and their influence on agility, have been the subject of several explicit calls for further research [13,36,37]. These calls emphasize the need to better understand how different customer profiles may shape APM [13], as well as the “organizational, cultural, and structural challenges” associated with involving customer representatives in agile environments [37].

Thus, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has explicitly examined the link between the customer’s OC and agility in ERP projects. Specifically, using the four OC types proposed by Cameron and Quinn [38] through the Competing Values Framework, our research question is as follows: How does the customer’s organizational culture—defined by the Competing Values Framework (clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market)—influence project agility in the context of SMEs’ ERP projects? We used the CVF because it is one of the most established and empirically validated models in OC research, widely used to capture organizational dynamics relevant to project environments [24,38,39].

We position this work in line with Felipe et al. (2017) and Gupta et al. (2019) [30,31], with the objective of understanding how different cultural contexts affect project agility, rather than prescribe an ideal “customer agile culture.” Although identifying the elements of an ideal agile culture is relevant, our approach emphasizes the importance of assessing the impact of each culture type on project agility. Such a perspective supports the idea that vendors should better frame and argue for introducing APM in ways that resonate with the customer’s cultural characteristics. In this regard, we assume that each culture is characterized by idiosyncratic features that may foster or hinder agility in distinct ways. Such an approach is particularly relevant in a context where the literature clearly acknowledges that changing an organization’s culture is difficult and far from a trivial task [26,31,32].

Beyond this theoretical positioning, our study also focuses on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that implement ERP systems for several reasons. In line with Canadian federal guidelines, we define SMEs as firms with 1 to 499 employees [40]. We deliberately distinguish SMEs from large companies, as the literature has highlighted that ERP implementation findings in large enterprises cannot necessarily be generalized to SMEs, and vice versa. This distinction is mainly due to the specific characteristics of SMEs that differentiate them from large firms—such as limited resources and technical expertise [41,42]. Moreover, SMEs are characterized by more dynamic activities than large organizations, often involving frequent changes in their business processes [42] and, consequently, in their project requirements. In this regard, APM has been identified as suitable for SMEs that implement ERP systems [18].

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background and literature review, including the conceptual foundations of our study and prior research. This section provides an in-depth examination of the customer’s role in agile projects and how the customer’s involvement may be linked to OC. It also reviews prior studies addressing the link between OC and agility. Section 3 outlines the hypothesis development and the research methodology. Section 4 reports the results and discussion. Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 conclude this paper with the theoretical implications, the managerial implications, and this study’s limitations and avenues for future research, respectively.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Foundations

2.1.1. Organizational Culture

To analyze customer organizational culture (OC), we used the Competing Values Framework (CVF) developed by Cameron and Quinn (2011), which remains one of the most recognized and widely applied models within OC research [38]. This framework has been extensively used in empirical studies [24,39]. It further provides a strong theoretical foundation for investigating organizational dynamics, including those observed in project management contexts [8,39]. Moreover, the CVF relies on validated measurement instruments [39].

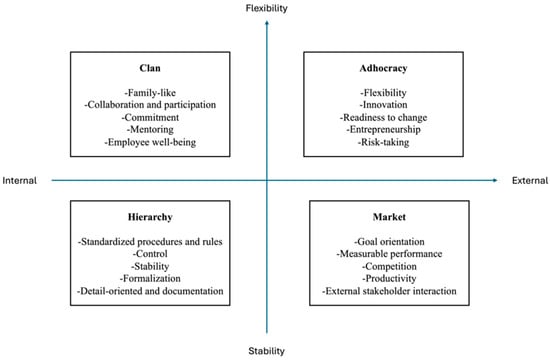

This framework defines two major dimensions of organizational values [38] that yield four cultural archetypes—namely, clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market—each involving particular and idiosyncratic characteristics [30]; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Competing Values Framework (CVF). Adapted from [38].

The first dimension distinguishes between the following [31]:

- (i)

- Stability, which emphasizes order, control, and continuity;

- (ii)

- Flexibility, emphasizing adaptability and dynamism.

The second dimension contrasts the following [31]:

- (i)

- Internally focused organizations, which rely on values such as collaboration, integration, and unity, reflecting concern for employees’ well-being;

- (ii)

- Externally focused organizations, which are oriented toward competition and differentiation, emphasizing an organization’s performance and survival and reflecting concern for the welfare of the organization itself.

The definition of each cultural archetype is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of each cultural archetype.

2.1.2. Project Agility

APM became particularly popular in 2001 following the publication of the “Agile Manifesto” [9,43], which brought together a set of principles and values defined as the essence of agile methods [44]. Most scholars agree that APM primarily aims to promote flexibility, simplicity, and the use of short, iterative cycles to deliver value progressively [45]. Compared to traditional methods, agile approaches were developed to respond to a dynamic environment characterized by uncertainty and change [12].

The literature has shown that applying these approaches universally across all project types is not advisable. Instead, organizations should adapt the chosen approach to a project’s specific context and environment [12,46]. As a result, few organizations actually manage their projects in a purely agile manner [44,47,48]. Although software professionals sometimes classify their approach as either agile or plan-driven, it should not be seen as a strict “dichotomous choice” [49]. Based on this idea, recent studies increasingly conceptualized agility in terms of varying degrees, rather than relying on a binary view of the concept [35,49,50,51]. Thus, as Lill et al. (2021) stated, “we consider project agility on a continuous scale; i.e., each project can be more or less agile” [50].

Building on this perspective, we adopt the following definition of project agility, which reflects the essence of agile project management (APM) as discussed by [7,13,15,24,35,49]. Project agility refers to a project team’s ability to quickly anticipate, adapt to, and learn from changing customer needs, market dynamics, or technological demands while continuously creating and delivering value for the customer [7,13,15,24,35,49]. In the context of ERP implementation projects, the project team typically represents the vendor side.

Thus, as highlighted by Bambauer-Sachse et al., the focus here is on managing uncertainty and acknowledging that customer requirements are likely to evolve throughout the project life cycle [24,49]. Project agility thus promotes flexible responses to change without the need for a formal change request process, regardless of the project stage. This flexibility enables the team to continuously accept and implement the emerging needs, even during the later phases of the project.

2.2. Prior Research

2.2.1. The Role of the Customer in Agile Projects

The notion of customer collaboration is rooted in one of the core values of the Agile Manifesto: “customer collaboration over contract negotiation” [9]. The importance of customer collaboration is also reinforced by two principles of the Agile Manifesto, which emphasize satisfying the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software and welcoming changing requirements to meet the customer’s needs [6,9].

In the context of agile project management (APM), customer collaboration refers to the extent to which the customer actively works with the project team to define project specifications and participates throughout the entire implementation process [13,52]. Such collaboration requires involvement in key stages, such as design, development, testing, and delivery—unlike traditional approaches, where participation generally occurs only at the beginning and end of the project [13,52,53]. In practice, this collaboration materializes through a variety of iterative activities, such as defining user stories, prioritizing product features, and providing continuous feedback and validation throughout the project life cycle, including goal setting and prototype evaluation [16,36,54]. Consequently, effective customer collaboration in agile projects comes with high expectations, as customers are required to act as supportive, knowledgeable, empowered, and actively engaged partners, demonstrating commitment to and responsibility for the project’s progress and outcomes [13,27,52].

Given this emphasis, in the APM context, the customer organization’s ability to collaborate with and support the development team is widely recognized as a key success factor, playing a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of agile approaches [27,34]. As Ciriello et al. (2022) noted, “the customer is not just a passive spectator of the agile adoption show” [13], but is rather an integral participant whose engagement directly shapes the success of agile adoption. In particular, in vendor–customer contexts, such as ERP implementation projects, Ciriello et al. (2022) highlighted that agility cannot be achieved unilaterally: both the vendor and the customer must adopt agile principles [13].

At the same time, this collaboration also represents a significant challenge in agile projects [13,35,36,52,55]. The literature examining the customer’s role in agile contexts highlights that the difficulties surrounding customer collaboration can stem from various sources, including time constraints, geographical distance, and a lack of technical or business expertise [36]. Several studies have also suggested that the customer’s underlying OC and mindset may not align with the agile way of working promoted by vendors or IT teams [13,37]. For example, Hoda et al. (2011) and Ramesh et al. (2010) noted that maintaining a mindset associated with traditional development—characterized by control, predictability, and rigid procedures—on the customer side can hinder project agility [36,53].

The literature on ERP implementation projects reinforces the importance of alignment and cultural compatibility between customers and vendors. Vendor–customer relationships have long been identified as critical success factors in ERP projects [56]. Greater compatibility between both organizations contributes to higher implementation success [57]. Cultural alignment, in particular, has been emphasized as a key determinant of effective cooperation between ERP-adopting staff and vendor teams [58]. Conversely, cultural mismatches can create misunderstandings and limit knowledge sharing.

Overall, these findings indicate that OC is a key enabler of customer collaboration and support, in turn facilitating project agility. It is therefore essential for ERP vendors to understand the customer’s OC such that APM can be introduced appropriately and successfully adopted. Focusing on the customer collaboration topic is particularly relevant since agile principles and practices typically assume a project environment in which customers are sufficiently and effectively engaged with the development team [13,36]. Yet, as highlighted by Hoda et al. (2011), this assumption does not always hold in real project settings, as the degree of customer collaboration tends to vary considerably across contexts [36]. The expectation of consistent and adequate customer involvement may thus be unrealistic and can even leave teams uncertain about how to proceed when customers fail to collaborate effectively.

2.2.2. The Link Between Organizational Culture (OC) and Agility

Several studies [8,24,26,28,30,31,32,33,59] have investigated the relationship between organizational culture (OC) and either agile or traditional project management approaches.

Except for the papers by Rizi et al. (2024) and Iivari et al. (2011)—a theoretical paper and a literature review [24,28], respectively—most of these studies used empirical data and either quantitative [8,30,31,32,33] or qualitative approaches [26,59]. Almost all of these studies focused on agile project management (APM), except the studies by [30,32]. Specifically, Iivari et al. (2007) focused on the relationship between OC and traditional approaches [32], whereas Felipe et al. (2017) explored the influence of OC at the organizational level rather than the project level [30].

The empirical findings of these studies highlight several interesting results. For example, they found a positive association between hierarchy culture and the use of traditional methods [32] and, conversely, a negative impact of this type of culture on agility [24,28,31]. In contrast, cultures that foster collaboration and encourage communication, or that proactively emphasize change, adaptability, and innovativeness, were shown to drive agility.

Although these studies provide important insights, all the empirical evidences available at the project level were collected from what we refer to as the “IT side”: either from IT departments, where software is developed internally, or from IT firms. These studies did not consider the customer perspective. Only the study by Smite et al. (2021) examined the relationship between a customer from the telecommunications industry and an outsourced vendor [59]. In that qualitative case study, the customer required that the vendor, characterized by a hierarchy culture, adopt agile practices. Yet, this sole customer–vendor study analyzed the culture of the vendor rather than that of the customer. Thus, the specific influence of the customer’s OC on agility, particularly within customer–vendor relationships, such as those found in ERP projects, remains largely unexplored.

2.2.3. Synthesis

This literature review highlighted how customer collaboration and support play a pivotal role in fostering project agility; this collaboration and support may be closely intertwined with the customer’s OC. While the relationship between OC and agile project management (APM) has been explored in prior research, no studies have examined the culture of the customer organization, particularly in the context of ERP implementation projects. Despite its recognized importance, the literature addressing this topic remains anecdotal and only superficially explored. To the best of our knowledge, no empirical studies have explicitly investigated how the customer’s OC shapes project agility. To address this gap, the present study focuses precisely on this relationship in the context of ERP projects in SMEs.

3. Hypothesis Development and Methodology

3.1. Hypothesis Development and Control Variables

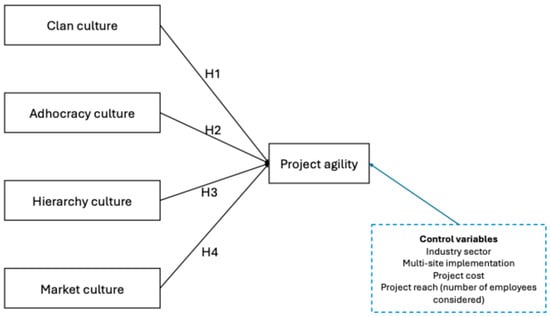

Following prior research linking organizational culture (OC) and agility [30,31], this study assumes that the four OC types in the Competing Values Framework (CVF) exhibit idiosyncratic features and particular attributes that may differentially influence project agility, the endogenous construct of this research model.

3.1.1. Clan Culture

Clan culture is characterized by a family-like environment that emphasizes collaboration, open communication, and employee commitment [8,24,30,38]. In the context of ERP implementation projects, customers from this cultural background are more likely to actively participate in and be committed to the ERP project [60]. Such customers are also more likely to cooperate and communicate effectively with the vendor and to share their knowledge freely, including evolving requirements or concerns that arise during the project. As highlighted in the literature, a high degree of communication and interaction with the customer enhances the vendor’s capability to respond promptly and adequately to changing or uncertain requirements, thereby supporting the agile way of working [6,34]. In other words, a customer organization characterized by a clan culture may strengthen responsiveness in the customer–vendor relationship. Such a relationship could create favorable conditions for the vendor to maintain continuous awareness of the customer’s evolving needs and to adjust project plans accordingly, ultimately fostering an environment conducive to agility [6].

Moreover, clan-oriented organizations typically emphasize employee well-being and work–life balance [31] which, in turn, fosters a positive and collaborative working atmosphere [30]. In this context, it can be assumed that customer organizations with a clan culture may grant their employees the flexibility to devote sufficient time and attention to the project without being overburdened by their regular duties, thereby fostering commitment and responsiveness to the vendor’s requests.

This forms the basis for the first hypothesis, which can be stated as follows:

H1:

A customer organization characterized by a clan culture positively influences project agility in ERP implementation projects.

3.1.2. Adhocracy Culture

Adhocracy culture is characterized by flexibility and adaptability [38]. It is associated with a dynamic and creative work environment that responds quickly and effectively to change [30,38]. Organizations with such a culture encourage entrepreneurial initiatives and risk-taking, empowering employees to make ad hoc decisions in response to changing circumstances [8,60]. These features closely mirror the core values of agile philosophy, demonstrating an intrinsic alignment between adhocracy culture and agility [8,30].

In the context of ERP implementation projects, although the vendor team is primarily responsible for addressing evolving customer requirements, customers from an adhocracy culture may be particularly receptive to the agile way of working. Having internalized values of flexibility and responsiveness [30,32], they are likely to appreciate, support, and even expect an iterative and adaptive approach from the vendor. This alignment in values between an adhocracy-oriented customer and an agile-oriented vendor may facilitate stronger customer engagement and collaboration, ultimately creating an environment that supports project agility.

This forms the basis for the second hypothesis, which can be stated as follows:

H2:

A customer organization characterized by an adhocracy culture positively influences project agility in ERP implementation projects.

3.1.3. Hierarchy Culture

Hierarchy culture is characterized by a formalized and structured work environment, guided by standardized procedures and rules [8,30,31,38]. Employees in organizations with such a culture are expected to follow predefined plans set by their superiors [31]. These organizations typically deliver their products or services through strictly defined, uniform, and stable processes [31]. They are also highly detail-oriented, placing strong emphasis on documentation [31], and tend to resist change and uncertainty [24,31]. In contrast to adhocracy culture, which mirrors agility principles, hierarchy culture opposes agile values such as flexibility, responsiveness to evolving requirements, collaboration, and minimal documentation. Moreover, hierarchy culture often discourages open communication and knowledge sharing [24,30], two mechanisms that are essential for effective customer–vendor collaboration in agile projects.

Based on these elements, in the context of ERP implementation projects, customer organizations characterized by a hierarchical culture may find it difficult to align with the vendor’s agile way of working, resulting in limited collaboration.

Studies focusing on customer-related challenges in agile projects have also shown that customers maintaining a traditional mindset, marked by control and rigid procedures, may struggle to support agility [36,53].

Furthermore, hierarchical organizations are more internally focused and less attentive to competitive pressures [31]. Given this internal orientation, customer organizations with such a culture are unlikely to perceive the value of project agility, even though agility could help them to better adapt to their own changing needs and market dynamics [31].

This forms the basis for the third hypothesis, which can be stated as follows:

H3:

A customer organization characterized by a hierarchical culture negatively influences project agility in ERP implementation projects.

3.1.4. Market Culture

Market culture is characterized by a strong emphasis on goal achievement, results orientation, and measurable performance [30,31,38]. Employees are encouraged to achieve clearly defined objectives within strict deadlines while continuously striving to enhance productivity [8,30]. Furthermore, organizations with a market culture are externally oriented: they closely monitor competitors and aim to outperform them by responding quickly to market trends and evolving customer expectations [31]. Alongside their competitive drive, such organizations value profitability and efficiency, seeking to minimize transaction costs [31]. In this sense, such values may resonate with several core characteristics of agility, which emphasize frequent delivery, rapid value creation, responsiveness to customer needs, and streamlined documentation [24,28]. Thus, these elements may align with the expectations of market-oriented customers who, in turn, are likely to adopt a collaborative attitude, thereby fostering stronger project agility.

Moreover, by promoting responsiveness to change, agility may be particularly appreciated by such customers, as their evolving requirements may stem from the need to adjust to shifting market conditions. The agile approach’s openness to late changes may therefore enable them to adapt more effectively to competitive and environmental pressures [30,31].

At the same time, market culture also maintains a certain degree of internal control and stability [31]. Although this focus on control may initially hinder agility, the rapid and visible outcomes generated through agile practices, such as frequent deliveries and measurable progress, may have the opposite effect. They can provide customers with a sense of control, thereby fostering greater acceptance of agility.

Finally, since organizations characterized by a market culture encourage interaction with external stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and partners [30], they may, in turn, foster effective communication and collaboration between customers and vendors in the context of ERP projects.

This forms the basis for the fourth hypothesis, which can be stated as follows:

H4:

The market culture of the customer organization positively influences project agility in ERP implementation projects.

3.1.5. Control Variables

In this study, industry sector, multi-site implementation, project cost, and project reach (i.e., the number of employees considered by the ERP system) were modeled as control variables.

3.1.6. Conceptual Model

Based on the above discussion, the proposed conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research framework.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Measurements

To measure organizational culture and project agility, we used validated scales from the existing literature (see Appendix A). Regarding the four organizational culture types (clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market), sixteen items—four per culture—were selected and adapted from previous studies [31,32,61,62]. For the project agility construct, eight items were formulated by combining and adapting existing measurement scales from the literature [35,49,51]. All items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.2.2. Data Collection and Sample

This study used data collected through the Leger Opinion (LEO) online panel. LEO is a well-established and widely recognized panel in Canada and is designed to be broadly representative of the Canadian adult population, with approximately 400,000 active members. This panel provides access to respondents working in a variety of professional contexts, including small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). For this research, we used a purposive and non-probability sampling strategy to target respondents who met our specific inclusion criteria.

This type of online panel has been successfully employed in previous information systems (IS) research [63,64,65]. We followed a procedure closely aligned with the methodologies described by Russo (2021) and Tripp et al. (2016), in which potential respondents from the panel were screened according to predefined eligibility criteria [64,65]. From this initial pool, only the participants who completed every survey item and passed multiple quality control checks were retained in the final dataset; the others were automatically excluded.

Specifically, eligible participants were ERP end-users from Canadian SMEs who had completed an ERP implementation project between one and four years before data collection. They also had to have played a key role in the project, such as key users or project managers. In addition, several attention-check questions were strategically embedded throughout the questionnaire to ensure data quality and participant engagement. Respondents who failed these checks were excluded from the analysis.

The questionnaire was first pre-tested with two professionals corresponding to the target respondent profile and two academics. This process allowed us to refine the wording of the survey items. A pilot test was then carried out with a group of 50 participants to further validate the phrasing and structure of the items.

The final data collection was conducted in March 2025, yielding 172 valid responses used for analysis. The participants represented the following sectors: Manufacturing (16.9%), information technology (15.7%), Banking (12.2%), Construction (9.3%), Healthcare (9.3%), Wholesale and Retail (7.0%), Education (6.4%), Telecommunication Services (3.5%), Public Services (3.5%), Logistics and Transportation (3.5%), Food and Beverages (1.2%), and others (11.4%). Firm size was distributed as follows: 4–9 employees (12.2%), 10–49 employees (26.7%), 50–249 employees (41.9%), and 250–499 employees (19.2%).

3.2.3. Data Analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in the SmartPLS software (version 4.1.0.9) was used for data analysis. This method was chosen for several reasons: first, PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for analyzing models with relatively small sample sizes [66]. Second, PLS-SEM is recommended when the theoretical foundations of a research topic are still emerging, which applies to this study [67]. Finally, PLS-SEM has recently attracted growing attention among researchers in the information systems field.

The analysis was carried out following the guidelines proposed by Hair et al. (2022) [67].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Validity and Reliability Assessment

The measurement model was assessed by examining indicator reliability (factor loadings), internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability—CR), and convergent validity (average variance extracted—AVE), as recommended by [67]. Items with loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 are considered for removal only when doing so improves CR, AVE, or Cronbach’s alpha. Following this guidance, all constructs were retained at this stage. The reported values exceeded the commonly accepted thresholds for Cronbach’s alpha (0.70), CR (0.70), and AVE (0.50), indicating satisfactory internal consistency and convergent validity. Furthermore, all items demonstrated acceptable indicator reliability.

To assess discriminant validity, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) was computed, following Hair et al.’s (2022) recommendations [67]. Since certain values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.90, two items (Clan3 and Market4) were removed due to relatively high cross-loadings that could threaten discriminant validity. After this elimination, the results indicated no further discriminant validity concerns. Table 2 and Table 3 present the final measurement model results, including indicator reliability, convergent validity, internal consistency, and discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, and convergent validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity (HTMT).

4.2. Common Method Bias

We employed several methods to assess the potential presence of Common Method Bias (CMB). First, we performed Harman’s single-factor test [68,69]. The unrotated principal component analysis revealed that the largest factor accounted for 44.3% of the total variance, which is below the recommended threshold of 50%. This result suggests that CMB did not represent a significant threat to our findings. In addition, we conducted a full collinearity test based on Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) following Kock et al.’s (2012) and Kock’s (2015) guidelines [70,71]. According to this approach, CMB is not a concern when all VIF values are below 3.3. In our model, the maximum VIF was 2.799, confirming that CMB was not a problem.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

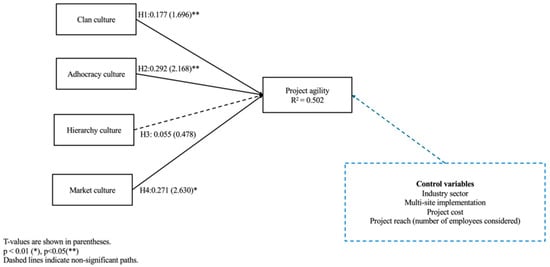

To test our hypotheses regarding the effects of the four customer-side organizational culture types on project agility, a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples was performed using SmartPLS. The results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structural model results.

We hypothesized that a customer characterized by a clan culture would positively influence project agility (H1). The results supported this first hypothesis, revealing a significant positive effect (β = 0.177, t = 1.696, p < 0.05).

We also hypothesized that a customer characterized by an adhocracy culture would positively affect project agility (H2). The results also supported this second hypothesis, indicating a significant positive effect (β = 0.292, t = 2.168, p < 0.05).

Furthermore, we proposed that a customer characterized by a hierarchy culture would negatively affect project agility (H3). This third hypothesis was not supported, as the results revealed a non-significant relationship (β = 0.055, t = 0.478, p > 0.05).

Finally, we posited that a customer characterized by a market culture would positively influence project agility (H4). The findings confirmed this fourth hypothesis, showing a significant positive relationship (β = 0.271, t = 2.630, p < 0.01).

The R2 value for project agility was 0.502, indicating a moderate level of explained variance, consistent with Hair et al.’s guidelines (2022).

The results also indicated that none of the control variables had a significant effect on project agility: industry sector (β = −0.030, t = 0.364, p = 0.358), multi-site implementation (β = −0.002, t = 0.014, p = 0.494), project cost (β = 0.039, t = 0.944, p = 0.172), and project reach (β = 0.059, t = 0.985, p = 0.162).

4.4. Discussion

In the context of agile project management (APM), the customer organization’s (OC) ability to collaborate with and support the development team is widely recognized as a key success factor, as it can either foster or hinder project agility [27,34]. At the same time, this collaboration and support often represent a significant challenge in agile projects [13,35,36,52,55]. Some authors have highlighted that customer support and collaboration may be linked to the customer’s OC [13,36,37,53].

In this context, this study aims to investigate the relationship between the customer’s OC and project agility in ERP implementation projects. The data were collected from Canadian SMEs. We specifically adopted the Competing Values Framework (CVF) proposed by Cameron and Quinn (2011) to conceptualize the four OC types of our model: clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market [38].

Our results confirmed that a customer organization characterized by a clan culture positively influences project agility. Such a culture fosters collaboration, open communication, and frequent interaction among stakeholders [8,24,30,38]. These relational mechanisms are likely to enhance mutual understanding between customers and vendors, facilitating faster feedback loops and more adaptive responses from the vendor side to changing or uncertain requirements [6,34]. Moreover, these results can be explained by the fact that organizations with this type of culture value employee well-being, which may allow their members to dedicate sufficient time and attention to the project, thus further supporting project agility. These results are consistent with previous studies. It should be noted that most prior research has examined the link between OC and agility either at the organizational level [30] or at the project level from the “IT side”—either within IT service firms or within IT departments where software is developed internally [8,31,33]. Thus, our findings suggest that similar mechanisms may operate across different contexts, where clan-oriented values, such as collaboration and internal cohesion, appear to facilitate agility.

The results also demonstrated the positive impact of a customer organization characterized by an adhocracy culture on project agility. This finding can be explained by the fact that several features of this culture closely mirror the core values of the agile philosophy, demonstrating a natural alignment between adhocracy and agility [8,30]. Indeed, this type of culture is characterized by flexibility and adaptability [38] and promotes a work environment that responds quickly and effectively to change [30,38]. Customers embedded in such a culture are likely to support—and even expect—iterative and adaptive project management approaches from the vendor, thereby fostering close collaboration and enhancing project agility. Similarly to clan culture, prior studies examining the relationship between OC and agility have also reported positive effects of adhocracy culture on agility [8,30,31]. These similarities suggest that adhocracy values foster agility at the organizational level, as well as in the context of IT projects on both the customer and IT sides.

The results further confirmed the positive impact of a customer organization characterized by a market culture on project agility. Prior studies examining the relationship between OC and agility have produced mixed results regarding the link between this culture and agility. Felipe et al. (2017) analyzed this relationship at the organizational level and found no significant link [30]. Gupta et al. (2019) and Iivari et al. (2007) found a positive association between market culture on the “IT side” and social agile practices and a negative link between this culture and traditional approaches, respectively [31,32]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the link between market culture and agility may vary depending on the context—whether examined from the customer or the IT side or at the project or organizational level. Concerning the customer side, our results suggest that customers driven by market-oriented values may actively support agile practices to ensure productivity, rapid delivery, and measurable outcomes. Indeed, the core principles of agility—such as frequent delivery, rapid value creation, responsiveness to customer needs, and streamlined documentation—may resonate with the characteristics of market-oriented organizations [31,38]. Moreover, agility, which promotes responsiveness to change and customer value creation, may be particularly appreciated by such customers, whose evolving requirements often stem from their need to adjust to shifting market conditions. In other words, a market-oriented customer may stimulate agility when agility is perceived as a means to enhance competitiveness. However, it is worth noting that market-oriented cultures also strongly emphasize stability and internal control. Agile principles, such as “welcoming changing requirements,” may initially appear to threaten such stability. Yet, our findings suggest that agility does not necessarily undermine this need for control. On the contrary, the rapid, visible, and measurable outcomes produced through iterative cycles may reinforce their sense of control. Additionally, the ability to incorporate evolving requirements can be perceived not as a source of instability but as a strategic and controlled mechanism through which the organization can rapidly respond to competitive pressures.

Finally, no evidence was found for the negative impact of a customer organization characterized by a hierarchy culture on project agility. A priori, we hypothesized that the characteristics of such a culture would oppose agile values—such as flexibility, responsiveness to evolving requirements, collaboration, and minimal documentation—and would therefore hinder agility. However, this assumption was not supported by the results. Previous studies conducted at the project level, particularly from the “IT side,” have reported a negative link between hierarchy culture and agility or, conversely, a positive association between hierarchy culture and traditional approaches [8,31,32]. Our results suggest that agility may be compatible with hierarchical customer contexts Specifically in SMEs, several mechanisms may attenuate the constraining effects typically associated with hierarchy culture, thereby rendering its impact on project agility potentially neutral rather than negative. First, prior research on SMEs highlights a set of characteristics that tend to prevail independently of organizational culture, including flatter organizational hierarchies, shorter decision-making cycles, lower levels of formalization, and less bureaucratic procedures [42,72,73,74]. As a result, these inherent characteristics of SMEs may attenuate the rigidity typically associated with hierarchy culture. Empirical evidence from qualitative case studies has examined how SME-specific characteristics influence knowledge management processes and ERP implementation activities [74]. These studies indicate that such SME characteristics can support communication and coordination among ERP project team members [42]. Moreover, short communication lines, often resulting from flatter organizational structures between managerial and operational levels, facilitate the transfer and sharing of knowledge in SMEs [74]. Thus, we argue that, even within hierarchical customer contexts, such mechanisms may soften hierarchical constraints, thereby enabling ERP vendors to adopt an agile posture. Second, SMEs may experience evolving or shifting needs, as they frequently operate in uncertain and unstable environments [42,72]. Such conditions can encourage vendor responsiveness independently of the customer’s dominant cultural profile. Third, certain agile practices can be implemented in ways that align with hierarchical preferences, preserving control and formality expectations while still enabling vendors to respond in an agile manner. Taken together, these mechanisms suggest that agility may still be feasible in hierarchical SMEs, not because the culture inherently favors agility, but because these compensating mechanisms may neutralize its restrictive aspects. In other words, the absence of significance may reflect a balance between agile and traditional ways of working, with the equilibrium shifting toward one or the other depending on the context. This would explain why the effect of hierarchy culture appears neutral.

5. Theoretical Implications

The objective of this study was to address the following question: How does the customer’s organizational culture (OC)—defined by the Competing Values Framework (clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market)—influence project agility in the context of SMEs’ ERP projects?

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to explicitly examine this relationship. It addresses several research gaps and calls for further investigation. First, the literature on adopting and using agile approaches in the specific context of standard software package implementation projects, such as ERP systems, remains at an early and largely underexplored stage [17,18,19]. This topic has been the subject of several calls for additional research [13,20,21]. Second, from a broader perspective, the role of the customer remains largely overlooked in the APM literature, despite its crucial influence in shaping project agility [13,34]. In particular, customer-related factors, such as OC, have been explicitly identified as areas requiring further research [13,36,37]. Third, although several studies have examined the relationship between OC and agility or traditional project management approaches [8,22,24,28,30,31,32,33,59], they did not consider the customer perspective. Finally, even within the ERP literature, the role of OC remains insufficiently explored [29].

6. Managerial Implications

Our study provides several practical insights for ERP vendors aiming to adopt project agility. As highlighted in the literature, customer collaboration and support in such projects are key determinants of project agility. Our results suggest that a better understanding of the customer’s OC, from the vendor’s perspective, can play a critical role in effectively introducing agility and fostering customer collaboration. Indeed, previous studies [36,53,55] have shown that customers may hold misconceptions about agility, leading them to be skeptical or distrustful of agile approaches. To overcome this skepticism, our results suggest that vendors should introduce agility according to the idiosyncratic characteristics of the customer’s OC. In other words, diagnosing and being aware of the customer’s cultural orientation can help vendors identify the most suitable way to justify and implement agility.

Based on our empirical results and the literature on OC and agile project management (APM), we developed a guidance framework presented as four culture–agility matching tables (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 present the matching tables for each culture).

Table 4.

Culture–agility matching table for clan culture *.

Table 5.

Culture–agility matching table for adhocracy culture *.

Table 6.

Culture–agility matching table for hierarchy culture *.

Table 7.

Culture–agility matching table for market culture *.

This proposition is built on the idea that few projects are fully agile [44,47,75]. Instead, teams often adopt hybrid approaches by selecting a set of practices from both agile and traditional methods. These practices may then be further tailored to the specific characteristics of the project environment [18]. The aim, therefore, is to introduce project agility in a way that resonates with each cultural orientation by providing a set of recommendations and priorities to facilitate the introduction, both in terms of practice selection and practice adaptation.

For each culture, each table includes (a) a set of recommendations for introducing agile practices depending on the cultural orientation and (b) a checklist of agile practices that tend to align with, or be more easily accepted in, each culture. The tables also include a reminder of the key characteristics of each culture, using the same keywords presented in Figure 1.

The set of recommendations is grounded in our hypotheses and empirical results. The list of 15 agile practices was derived from the literature on widely used agile practices [43,76,77,78]. Prior studies have distinguished between software- and management-related agile practices [10,24,79]. In this study, we focused specifically on management-related practices, as these directly involve or affect customer participation. In contrast, software-related practices are primarily concerned with system architecture, testing activities, or programming tasks and, therefore, do not typically require customer engagement.

Although hierarchy culture was not statistically significant in our model, we included it as we discussed how agility may still be introduced in such contexts through appropriate practice adaptation.

To use the framework, we recommend the following steps:

- Diagnose the customer’s dominant culture, for example, using tools such as the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) [38].

- Use the matching table to prioritize and tailor agile practices according to the diagnosed cultural profile.

The OCAI is a diagnostic tool composed of several culture-related dimensions, such as the dimension assessing the organization’s dominant characteristics. Each dimension includes four alternatives, each representing one of the four organizational culture types considered in this study. For every dimension, respondents distribute a total of 100 points across these four alternatives to indicate the extent to which each cultural type reflects their organizational context. The wording of this tool is aligned with the cultural characteristics captured by the items used in our measurement instrument. After completing all dimensions, the scores associated with each cultural type are aggregated (for example, for clan culture, by averaging the points assigned to all alternatives representing that cultural type). This allows the dominant culture to be identified. The instrument is typically completed by individuals who have sufficient knowledge of the organizational unit being assessed.

The recommendations provided in the matching tables should be interpreted with nuance. They are not prescriptive in the sense that they do not dictate what must be completed. Instead, they offer suggested priorities and alignments between cultural orientations and agile practices. The table serves as a guiding tool for introducing agility, informed by our empirical findings, to optimize successful agile adoption within each cultural context.

Our final managerial implication relates to the suggestion that the decision to adopt agility often stems from practitioners’ experience or personal preferences and may, in some contexts, remain poorly communicated or insufficiently formalized [18,80,81]. This lack of formalization may generate ambiguity and confusion on the customer’s side regarding the project management approach being implemented [18], increasing the risk of customer resistance. Therefore, our results may foster greater willingness among vendors to communicate more clearly with customers about the project management approach being implemented, thereby reducing the risk of confusion on the customer’s side.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides valuable theoretical and managerial contributions, it also has some limitations that open promising avenues for future research. To begin with, the methodological choices present certain limitations. The empirical data were collected through a non-probabilistic sampling method using an online panel based in Canada. While this approach enabled access to a targeted population of ERP end-users in SMEs, the resulting sample does not fully reflect the actual distribution of firm sizes and industries within the Canadian SME population. In particular, some firm size categories and industries are relatively overrepresented in the sample, while others are underrepresented. For example, medium-sized SMEs (250–499 employees) account for a higher proportion of the sample than their prevalence in the Canadian SME landscape, and manufacturing firms are also overrepresented compared to the overall Canadian SME population [40]. As a result, the generalizability of the results is limited. Future research could replicate this study using a probabilistic sampling strategy allowing a representative distribution of firm sizes and industries within Canada. Future research could also extend the analysis to other national contexts and examine larger customer organizations.

Another limitation concerns the operationalization of the project agility construct. Our measurement focuses on vendor responsiveness, in line with the prior literature, but does not explicitly capture customer participation in an agile manner (for example, the proactive feedback on iterative results or the frequency of customer-initiated requirement changes). Future research could adopt a broader perspective on project agility by incorporating these customer-side indicators. This would require developing a dedicated construct that captures customer-side agility. Doing so would certainly deepen the understanding of the culture–collaboration–agility pathway.

Furthermore, this is a cross-sectional study that examines relationships at a single point in time. A longitudinal research design could therefore be employed to assess how the OC–agility relationship evolves throughout the project life cycle.

Future research could further explore other contextual factors influencing project agility in ERP projects, such as environmental dimensions associated with the VUCA framework—volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity [82].

Finally, this study offers an original set of recommendations for ERP vendors through a guidance framework presented as four culture–agility matching tables (for each culture), which aims to support the adoption and adaptation of agile practices according to different customer cultural orientations. This guidance framework extends the current understanding of how agility can be implemented and adapted in ERP projects within SMEs, depending on the customer’s organizational culture. This contribution responds to several calls in the project management literature that emphasize the need to develop associative mappings between contextual factors and project management practices, acknowledging that the most appropriate project management approach is contingent on its context [23,46,83]. Future research could build on these findings through qualitative approaches, such as in-depth case studies of SMEs instantiating different dominant cultural profiles (e.g., family-owned firms, innovation-oriented SMEs, or highly competitive market-driven firms). Such studies would allow researchers to empirically illustrate and further refine how agile project management practices are adapted in ERP projects across different cultural contexts.

Funding

This research was funded by FRQSC—Relève professorale, grant number 312303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.69777/312303.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of l’Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM). Reference: 2024-6553. Date of approval: 11 April 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. As the participants did not provide consent for public data sharing at the time of this study, the dataset would need to be stripped of indirect identifiers before any release.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) solely to enhance the linguistic quality of this manuscript, particularly to improve the clarity and readability of individual sentences. After using this tool, the author carefully reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication. No additional information was generated by this AI tool, and at no point was AI used for any analytical input or data analysis within this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

| APM | Agile project management |

| OC | Organizational Culture |

| SMEs | Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items.

Table A1.

Items.

| Constructs | Item Code—Item |

|---|---|

| Organizational culture—adapted [31,32,61,62]. | Clan1—The company I work in is a very personal place. It is like an extended family and people seem to share a lot of themselves. Clan2—The glue that holds the company I work in together is loyalty and tradition. Commitment to the company I work in runs high. Clan3—The company I work in emphasizes human resources. High morale is important. ** Clan4—The leadership in the organization is generally considered to exemplify mentoring, facilitating or nurturing. |

| Adhocracy1—The company I work in is a very dynamic and entrepreneurial place. People are willing to stick their necks out and take risks. Adhocracy2—The glue that holds the company I work in together is commitment to innovation and development. There is an emphasis on being first with products and services. Adhocracy3—The company I work in emphasizes growth through acquiring new resources. Acquiring new products/services to meet new challenges is important. Adhocracy4—The leadership in the organization is generally considered to exemplify entrepreneurship, innovation or risk taking. | |

| Hierarchy1—The company I work in is a very formal and structured place. People pay attention to bureaucratic procedures to get things done. Hierarchy2—The glue that holds the company I work in together is formal rules and policies. Following rules and maintaining a smooth-running institution are important. Hierarchy3—The company I work in emphasizes permanence and stability. Efficient, smooth operations are important. Hierarchy4—The leadership in the organization is generally considered to exemplify coordinating, organizing, or smooth-running efficiency. | |

| Market1—The company I work in is a very production-oriented place. People are concerned with getting the job done and are not very personally involved. Market2—The glue that holds the company I work in together is an emphasis on tasks and goal accomplishment. A production and achievement orientation is commonly shared. Market3—The company I work in emphasizes competitive actions, outcomes, and achievement. Accomplishing measurable goals is important. Market4—The leadership in the organization is generally considered to exemplify a no-nonsense, aggressive, results-oriented focus. ** | |

| Project agility—adapted from [35,49,51] | PA1—Expected or unexpected changes from your company was accommodated during the project. PA2—The vendor/integrator was able to react to changes in your company’s requests and implement solutions accordingly. PA3—In case of changes in the project scope, the vendor/integrator was able to immediately analyze these changes and make a quick decision. PA4—In case of changes in the project scope, the vendor/integrator was able to immediately update the project plan and communicate the changes to all stakeholders. PA5—The integration of new requirements was possible without a formal change request (through a contract modification). PA6—New emerging requirements were welcome during the project. PA7—The vendor/integrator frequently delivered partial results of the project. PA8—The management method used produced quick results. |

**: dropped to improve discriminant validity.

References

- Hustad, E.; Stensholt, J. Customizing ERP-systems: A framework to support the decision-making process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 219, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butarbutar, Z.T.; Handayani, P.W.; Suryono, R.R.; Wibowo, W.S. Systematic literature review of critical success factors on enterprise resource planning post implementation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2264001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Daneva, M. An approach to estimation of degree of customization for ERP projects using prioritized requirements. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 117, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, E.; Gezici, B.; Aydos, M.; Tarhan, A.K.; Garousi, V. ERP failure: A systematic mapping of the literature. Data Knowl. Eng. 2022, 142, 102090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dospinescu, O.; Buraga, S. Integrated ERP systems—Determinant factors for their adoption in romanian organizations. Systems 2025, 13, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steegh, R.; De Voorde, K.V.; Paauwe, J.; Peeters, T. The agile way of working and team adaptive performance: A goal-setting perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 189, 115163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckenstock, J.-N. Shedding light on the dark side—A systematic literature review of the issues in agile software development methodology use. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 211, 111966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Organizational culture and project management methodology: Research in the financial industry. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 1270–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.; Beedle, M.; van Bennekum, A.; Cockburn, A.; Cunningham, W.; Fowler, M.; Grenning, J.; Highsmith, J.; Hunt, A.; Jeffries, R.; et al. Manifesto for Agile Software Development. 2001. Available online: http://agilemanifesto.org (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Campanelli, A.S.; Parreiras, F.S. Agile methods tailoring—A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2015, 110, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sun, X.; Liu, M. Critical success factors in agile-based digital transformation projects. Systems 2025, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Lemétayer, J. Factors associated with the software development agility of successful projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, D.R.F.; Glud, J.A.; Hansen-Schwartz, K.-H. Becoming agile together: Customer influence on agile adoption within commissioned software teams. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahimbisibwe, A.; Daellenbach, U.; Cavana, U.D. Empirical comparison of traditional plan-based and agile methodologies- Critical success factors for outsourced software development projects from vendors’ perspective. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 400–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforto, E.C.; Salum, F.; Amaral, D.C.; Luis da Silva, S.; Magnanini de Almeida, L.F. Can Agile Project Management Be Adopted by Industries Other than Software Development? Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrador, P.; Pinto, J.K. Does Agile work?—A quantitative analysis of agile project success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Hustad, E.; Sutcliffe, N.; Beckfield, M. Organic transformation of ERP documentation practices: Moving from archival records to dialogue-based, agile throwaway documents. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 74, 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoghli, S.; Cassivi, L. Agile ERP Implementation: The case of a SME. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), Heraklion, Greece, 3–5 May 2019; Volume 2, pp. 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, M.; Hustad, E.; Sutcliffe, N. Agility and system documentation in large-scale enterprise system projects: A knowledge management perspective. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneva, M.; Wieringa, R. Requirements engineering for enterprise systems: What we know and what we don’t know? In Intentional Perspectives on Information Systems Engineering; Nurcan, S., Salinesi, C., Souveyet, C., Ralyté, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Isetta, S.; Sampietro, M. Agile in ERP Projects. PM World J. 2018, 7. Available online: https://pmworldlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/pmwj74-Sep2018-Isetta-Sampietro-agile-in-erp-projects-featured-paper.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Tolfo, C.; Wazlawick, R.S.; Gomes Ferreira, M.G.; Forcellini, F.A. Agile methods and organizational culture: Reflections about cultural levels. J. Softw. Maint. Evol. Res. Pract. 2011, 23, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchten, P. Contextualizing agile software development. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2013, 24, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizi, M.S.; Andargoli, A.E.; Malik, M.; Shahzad, A. How does organisational culture affect agile projects? A competing values framework perspective. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2024, 55, 1077–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerur, S.; Mahapatra, R.; Mangalaraj, G. Challenges of Migrating to Agile Methodologies—Organizations must carefully assess their readiness before treading the path of agility. Commun. ACM 2005, 48, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolfo, C.; Wazlawick, R.S. The influence of organizational culture on the adoption of extreme programming. J. Syst. Softw. 2008, 81, 1955–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.C.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, U. Identifying some important success factors in adopting agile software development practices. J. Syst. Softw. 2009, 82, 1869–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivari, J.; Iivari, N. The relationship between organizational culture and the deployment of agile methods. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2011, 53, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B.; Byström, M. The role of organizational culture in ERP implementation—The case of replacing an old ERP in a retail organization. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 239, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, C.M.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Impact of organizational culture values on organizational agility. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; George, J.F.; Xiaa, W. Relationships between IT department culture and agile software development practices: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivari, J.; Huisman, M. The relationship between organizational culture and the deployment of systems development methodologies. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strode, D.; Huff, S.L.; Tretiakov, A. The impact of organizational culture on agile method use. In Proceedings of the 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’42), Big Island, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tessem, B. The customer effect in agile system development projects. A process tracing case study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 121, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, A.; Zaveri, J.; David, D.; Stephen Davis, J.S. The impact of project team characteristics and client collaboration on project agility and project success: An empirical study. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 758–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoda, R.; Noble, J.; Marshall, S. The impact of inadequate customer collaboration on self-organizing Agile teams. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2011, 52, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalagh, M.; Svesengen, V.; Farshchian, B.A. Investigating user-side representatives in large-scale agile software development. In Proceedings of the 26th Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming (XP 2025), LNBIP 545, Brugg-Windisch, Switzerland, 2–5 June 2025; Peter, S., Kropp, M., Aguiar, A., Anslow, C., Lunesu, M.I., Pinna, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Feng, Y.; Liu, L. The mediating effect of organizational culture and knowledge sharing on transformational leadership and Enterprise Resource Planning systems success: An empirical study in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2400–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISED. Key Small Business Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/sme-research-statistics/sites/default/files/documents/ksbs-2024-v1-en.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Poba-Nzaou, P.; Raymond, L. Custom Development as an Alternative for ERP Adoption by SMEs: An Interpretive Case Study. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2013, 30, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, O.; Munkvold, B.E.; Olsen, D.H. ERP system implementation in SMEs: Exploring the influences of the SME context. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2012, 8, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, J.F.; Armstrong, D.J. Agile methodologies: Organizational adoption motives, tailoring, and performance. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2018, 58, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, A.S.; Camilo, R.D.; Parreiras, F.S. The impact of tailoring criteria on agile practices adoption: A survey with novice agile practitioners in Brazil. J. Syst. Softw. 2018, 137, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanha, A.; Argoud, A.R.T.T.; Camargo, J.B., Jr.; Antoniolli, P.D. Agile project management with Scrum: A case study of a Brazilian pharmaceutical company IT project. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2017, 10, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; O’Connor, V. The situational factors that affect the software development process: Towards a comprehensive reference framework. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2012, 54, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qumer, A.; Henderson-Sellers, B. A framework to support the evaluation, adoption and improvement of agile methods in practice. J. Syst. Softw. 2008, 81, 1899–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, G.; Kuhrmann, M.; Münch, J.; Diebold, P. Is Water-Scrum-Fall Reality? On the Use of Agile and Traditional Development Practices. In Product-Focused Software Process Improvement, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference, PROFES 2015, Bolzano, Italy, 2–4 December 2015; LNCS 9459; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bambauer-Sachse, S.; Helbling, T. Customer satisfaction with business services: Is agile better? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Lill, P.A.; Wald, A. The agility-control-nexus: A levers of control approach on the consequences of agility in innovation projects. Technovation 2021, 107, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, A.; Mohammad, S.; Wald, A. Agility as a matter of degree: An empirical study of determinants of agility in projects. Die Unternehm—Swiss J. Bus. Res. 2020, 72, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estellés, E.; Pardo, J.; Sánchez, F.; Falco, A. A modified agile methodology for an ERP academic project development. In New Achievements in Technology, Education and Development; Soomro, S., Ed.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, B.; Cao, L.; Baskerville, R. Agile requirements engineering practices and challenges: An empirical study. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 20, 449–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruping, L.M.; Matook, S. The multiplex nature of the customer representative role in agile information systems development. MIS Q. 2020, 44, 1411–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrutsky, S.; Erturk, E. The agile transition in software development companies: The most common barriers and how to overcome them. Bus. Manag. Res. 2017, 6, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, T.M.; Nelson, K. The impact of critical success factors across the stages of enterprise resource planning implementations. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 6 January 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ramayah, T.; Roy, M.H.; Arokiasamy, S.; Zbib, I.J.; Ahmed, Z. Critical success factors for successful implementation of enterprise resource planning systems in manufacturing organisations. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2007, 2, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezdar, S.; Ainin, S. The influence of organizational factors on successful ERP implementation. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smite, D.; Brede Moe, N.; Gonzalez-Huerta, J. Overcoming cultural barriers to being agile in distributed teams. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 138, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Wei, K.K. Organizational culture and leadership in ERP implementation. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 45, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; McFadden, K.L.; Lee, M.K.; Gowen, C.R. U.S. hospital culture profiles for better performance in patient safety, patient satisfaction, Six Sigma, and lean implementation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 234, 108047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, H.-J.; Thomas Mattson, T.; Kim, D.J. The “Right” recipes for security culture: A competing values model perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2021, 34, 1490–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, D. Agile values or plan-driven aspects: Which factor contributes more toward the success of data warehousing, business intelligence, and analytics project development? J. Syst. Softw. 2018, 146, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D. The agile success model: A mixed methods study of a large-scale agile transformation. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2021, 37, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, J.F.; Riemenschneider, C.; Thatcher, J.B. Job satisfaction in agile development teams: Agile development as work redesign. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q. Issues in Specifying Requirements for Adaptive Software Systems; Växjö University: Växjö, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, O.; Munkvold, B.E. Identifying reasons for ERP system customization in SMEs: A multiple case study. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2012, 25, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbussa, A.; Bikfalvi, A.; Marquès, P. Strategic agility-driven business model renewal: The case of an SME. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supyuenyong, V.; Islam, N.; Kulkarni, U. Influence of SME characteristics on knowledge management processes: The case study of enterprise resource planning service providers. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2009, 22, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, S.; Rausch, A.; Andelfinger, U. Towards the systematic development of hybrid software development processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software and System Process (ICSSP 2018), Gothenburg, Sweden, 26–27 May 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 157–161. [Google Scholar]