Abstract

Crypto asset markets are often described as globally integrated. However, empirical evidence suggests that they remain segmented across exchanges and jurisdictions. One notable example is the Korean premium (i.e., Kimchi premium), which refers to persistent price gaps between Korean exchanges and offshore venues. The Korean market accounts for a substantial share of global crypto trading activity. Therefore, this segmentation can affect price discovery and create opportunities for systematic trading. Motivated by the Korean premium, this study introduces the Korean Venue Share Indicator (KVSI). Based on the price discovery literature, KVSI is an interpretable venue-level indicator that uses the relative trading volume share between Korean and global exchanges. This study integrates KVSI into the state space of multiple reinforcement learning algorithms to evaluate whether venue-level information improves trading decisions. The results show that the proposed model with KVSI achieves statistically significant improvements in cumulative return (CR), Sharpe ratio (SR), and maximum drawdown (MDD) compared to the baseline model without KVSI. It also achieves higher CR and mixed effects on risk metrics (SR, MDD) relative to benchmark strategies. Additional analyses indicate that the performance gains from KVSI are market-regime-dependent. Overall, the findings have practical implications for developing cross-market systematic trading strategies by leveraging a venue-level indicator as a proxy for market segmentation.

1. Introduction

Since 2024, spot Bitcoin and Ether exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have begun trading in major markets, notably in the United States and Hong Kong. As 2025 began, weekly net inflows into global crypto asset ETFs reached record highs, and BlackRock’s iShares Bitcoin Trust approached USD 100 billion in assets under management [1,2,3,4,5]. Against this backdrop, the crypto asset market has been rapidly integrating into the regulated financial system, driven by technological and regulatory developments. Although it is often described as a global market operating 24/7, constraints on capital mobility, residency-based rules, exchange listing policies, and participant composition differ across jurisdictions. These differences make it difficult to regard it as a single integrated market. Repeated evidence of structural heterogeneity and market segmentation has been documented [6].

In environments where multiple exchanges coexist, information is neither generated nor impounded into prices simultaneously. Empirical studies show that leadership in price discovery can rotate over time. Certain venues lead at some points, and the hierarchy reverses at others [7,8,9,10]. These findings suggest that incorporating exchange and region-level order flow information into the model’s state variables, summarizing for each asset who trades where, can materially affect trading decisions and performance.

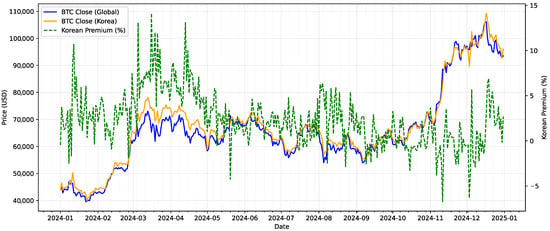

The Korean crypto asset market is a systemically important venue cluster in global spot trading. Chainalysis reports that Eastern Asia accounted for 8.9% of global on-chain value between July 2023 and June 2024, with the Korean market receiving roughly USD 130 billion over this period. In KRW-denominated trading, activity is concentrated in altcoins and stablecoins, and net transfers from domestic exchanges to global platforms co-move with the Korea Premium Index [11]. These patterns indicate venue-specific price discovery and segmented liquidity. Taken together, these features make the Korean market a natural setting in which to study venue-specific dynamics and market segmentation. Consistent with this characterization, as shown in Figure 1, prices on major Korean spot exchanges (e.g., Upbit, Bithumb) have repeatedly traded at a premium to those on major offshore venues (e.g., Binance), a phenomenon commonly termed the Korean premium (i.e., Kimchi premium). In the literature, this has been documented as a recurring violation of the Law of One Price for identical assets and is reported to exhibit a nonlinear, threshold-driven, multi-regime structure rather than a simple linear pattern [12]. Institutional and operational frictions related to cross-border capital outflows and inflows impede the immediacy and completeness of arbitrage. Differences in access pathways for resident and non-resident investors further slow arbitrage. As a result, price discrepancies can persist for periods of time [6,13]. In this context, changes in regional exchanges’ shares of trading volume can function as an observable summary measure of the relative strength of local demand and supply, and this regionality is especially pronounced for small- and mid-cap altcoins led by Korean exchanges (often referred to as Kimchi coins).

Figure 1.

Price difference between Korean and global exchanges (Korean premium), 2024.

Unlike equities and bonds, crypto assets lack well-established fundamental signals such as dividends or cash flows, which elevates the relative importance of order flow and microstructure factors. This has long motivated interest in data-driven systematic trading, and machine learning approaches, including reinforcement learning (RL), have spread rapidly in both empirical and applied work [14,15]. Nevertheless, many RL-based crypto asset trading studies incorporate price and volume, technical indicators, and sometimes on-chain variables. They do not explicitly include state variables that quantify exchange- or region-level liquidity concentration. For example, few studies use the venue share of a given cluster of regional exchanges in trading a specific asset. Moreover, in light of the time-varying leadership documented in the price discovery literature for cross-venue crypto asset markets [7,8,9,10] and the structural segmentation of the Korean market [12,13], connecting a measure that captures the strength of regional order imbalances to RL decision making is justified on both academic and practical grounds.

This study addresses this gap by defining KVSI, a venue-level indicator that uses the relative trading volume share between Korean and global exchanges. This study then systematically evaluates the incremental effect of including KVSI in the RL state space on trading performance. This motivation is grounded in prior evidence that leadership in price discovery within cross-venue spot and futures markets is decisively shaped by microstructure forces, including relative volume [9,10], and in empirical results indicating that the Korean market’s nonlinear behavior reflects regional order imbalance dynamics [12,13]. Based on this rationale, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Including KVSI in the RL state space improves trading performance relative to an otherwise identical model without KVSI.

The research design is summarized as follows. The training period is 2021–2023 and the test period is 2024, with evaluations conducted on a quarterly basis to mitigate seasonality and point-in-time dependence. The test universe is drawn from assets listed on Binance, Upbit, and Bithumb during 2021–2023. Using KVSI and trading volume observed, k-means clustering is applied, and only the middle cluster is retained to reduce biases that can arise near extreme KVSI regions (close to 0 or 1). The RL state space is built from daily OHLCV and technical indicators, and the full feature set is engineered to reduce noise in the input space and to help identify the incremental contribution of venue-level information. The proposed model augments this set with KVSI. To avoid algorithm-specific dependence, three representative algorithms widely used in RL-based systematic trading, namely PPO, A2C, and DQN, are employed, with implementations from the reproducible library Stable-Baselines3. The reward function uses the previous day’s log return to dampen feedback distortions from action synchronization, and executions are priced at the next day’s open to eliminate look-ahead bias. Performance is evaluated using CR, SR, and MDD, and results are averaged over repeated runs with multiple algorithms and independent seeds to reduce single-path dependence.

This paper makes the following main contributions: First, we directly model regional market segmentation in crypto asset trading by proposing KVSI, a simple scalar measure of cross-exchange relative liquidity that is embedded into the state space of RL-based trading agents. Second, we design a controlled experimental setup that compares agents with and without KVSI under identical architectures, preprocessing steps, trading rules, and reward definitions. This design allows the marginal effect of venue segmentation information to be isolated from algorithmic or implementation artifacts. Third, we construct a reproducible and interpretable evaluation pipeline. It is based on clearly specified preprocessing procedures, train–test splits, and multi-run backtests. This enables a transparent assessment of RL-based crypto trading systems and mitigates the risk of backtest overfitting. Finally, although KVSI is designed for the Korean premium setting, the same venue share design can be extended to construct similar region-level indicators for other major exchange clusters. Such extensions offer a general template for multi-market RL trading frameworks.

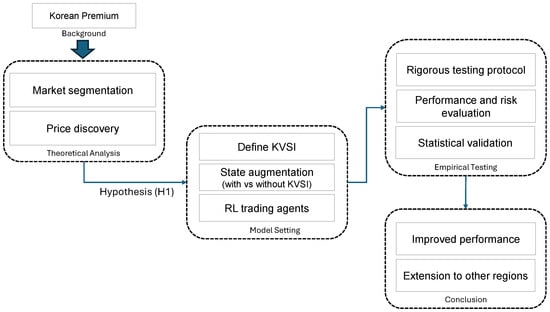

To synthesize the motivation and study design discussed above, Figure 2 summarizes the research logic of this study. It links the theoretical foundations to the hypothesis, model setting, empirical tests, and conclusion.

Figure 2.

Research logic diagram of this study.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on the Kimchi premium, price discovery, and systematic trading in the crypto asset market. Section 3 describes the research methodology, including data collection and preprocessing and asset universe clustering. Section 4 describes model training and the backtesting and evaluation procedures. Section 5 presents the experimental setup and analyzes the empirical results. Section 6 discusses the study’s contributions and limitations and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Regarding market segmentation, Makarov and Schoar, using a multi-exchange, multi-country panel, document that cross-country price discrepancies are particularly large and can persist when arbitrage is constrained by capital controls and regulatory differences [6]. In the Korean crypto asset market, the “Kimchi premium,” in which domestic prices trade above offshore levels, recurs. Recent studies identify nonlinear, threshold-dependent multi-regime dynamics and their determinants [12]. Administrative and macroeconomic evidence further indicates that cash-out channels linked to cross-border remittances contributed to the persistence of the deviation during premium episodes [13]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the assumption of instantaneous convergence to a single global price often fails in practice and that variables capturing regional liquidity concentration may provide information useful for prediction and trading.

The price discovery literature has focused on information leadership within multi-exchange settings that combine spot and derivative venues. Brandvold et al. document rotations in venue leadership and heterogeneous information contributions in the early Bitcoin spot market, underscoring the importance of exchange choice [7]. Koutmos provides a systematic decomposition of price discovery across exchanges and shows that estimates are sensitive to venue-specific microstructure noise and to sampling frequency [8]. Studies of the lead–lag relation between spots and futures likewise find that leadership varies with the sample period, metrics, and composition [9,10]. In particular, Entrop et al. attribute much of the variation in price discovery contributions to relative volume and relative trading costs [9], while Alexander and Heck show that perpetuals and futures on unregulated derivative venues can play a dominant role [10]. Taken together, leadership in price discovery is time-varying when relative liquidity and participant mix change, and this variation can be partially captured by order flow summaries such as venue share. The KVSI proposed in this study translates these insights into the state space of the RL model.

Beyond venue-level liquidity measures, a growing body of systems-oriented research emphasizes that information diffusion and collective behavior are shaped by the structure of interaction networks. Social network analysis provides a practical toolkit for characterizing network structure using summary statistics such as connectivity, centrality, and core–periphery patterns, and recent work also combines these measures with dynamic network models to study how networks evolve under external shocks [16]. Complementary causal discovery approaches, such as dynamic Bayesian networks, have also been used to uncover time-varying causal relationships among financial variables and to visualize contemporaneous and lagged dependence structures [17]. These perspectives suggest that KVSI may reflect not only cross-venue relative liquidity but also the underlying information diffusion and collective action mechanisms associated with region-specific investor communities.

As summarized in Table 1, systematic trading studies in the crypto asset market span classical technical rules and machine learning-based signals, and this body of literature has expanded rapidly. Numerous studies report that simple rules such as moving averages (MAs) and trading range breakouts (TRBs) deliver statistically significant excess returns in specific samples or market conditions [18], and broader searches evaluating nearly 15,000 rules find that some predictability remains even after data snooping corrections [19]. Related evidence based on moving-average-distance timing signals also documents economically meaningful effects across international markets [20]. At the same time, reality checks show that when transaction costs and slippage are modeled rigorously, or when multiple-testing adjustments are applied, statistical significance can weaken [21]. These mixed findings motivate a conservative, reproducible design that prioritizes risk-adjusted performance in the high-volatility, low-signal setting characteristic of crypto markets. Against this backdrop, RL for crypto trading has expanded across policy gradient, value-based, and actor–critic families. For example, Jiang and Liang demonstrate a deep RL framework for cryptocurrency portfolio management [22]. Reproducible libraries such as Stable-Baselines3 provide a common basis for comparative studies [23], and empirical applications in crypto report heterogeneous outcomes depending on the asset universe, reward design, and sampling frequency. In a related pair trading formulation, PPO, DQN, and A2C exhibit materially different behaviors once leverage, transaction costs, and action constraints are imposed, underscoring the centrality of cost modeling and policy regularization [24]. Other applications build state spaces that combine widely used technical indicators with on-chain covariates and report that attention-based aggregation improves interpretability and decision quality [25,26]. Microstructure evidence also reports informed trading in cryptocurrency markets using tick-by-tick data [27]. Even so, few studies have quantified exchange- or region-level liquidity concentration and injected it into the RL state space to then systematically test its effects on policy behavior and risk-adjusted performance. This study differentiates itself by defining an interpretable indicator, KVSI, and evaluating a with-versus-without contrast under identical algorithms and benchmarks.

Table 1.

Summary of systematic trading studies in the crypto asset market.

Methodologically, to ensure that our empirical findings from simulation-based trading are statistically credible, this study follows best practices identified in the backtesting and systematic trading literature. The design remains alert to selection bias and overfitting in repeated simulations [28]. Accordingly, look-ahead bias is mitigated by executing trades at the next day’s open [29], results are reported as averages over repeated experiments across quarters and independent seeds [30], and multiple benchmarks, including Buy-and-Hold, MA Crossover, and Random Trader, are employed to contextualize RL performance [31,32,33].

The prior literature documents time variation in both market segmentation and price discovery, as well as the promise and limits of technical and RL-based trading signals. However, few studies explicitly encode heterogeneity measures, such as regional exchange market share, into the RL state space and then systematically analyze their impact on policy structure and risk-adjusted performance. By defining KVSI, which summarizes cross-venue features of the Korean market, and by examining its effects through controlled, like-for-like contrasts under identical conditions, this study contributes at the intersection of the price discovery, market microstructure, and RL-based systematic trading literature.

3. Data and Feature Engineering

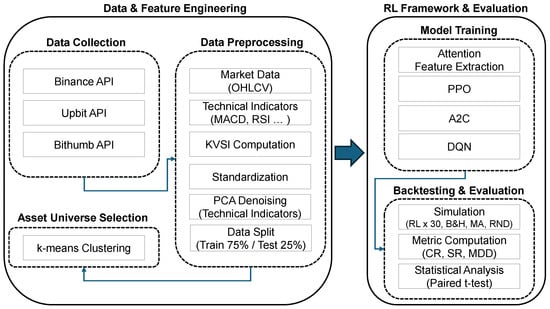

Figure 3 summarizes the end-to-end workflow of the study. This section describes data collection, KVSI computation, preprocessing, and universe selection, while Section 4 details the RL framework, training protocol, and evaluation design.

We use daily spot market data retrieved via the official public APIs of two Korean exchanges (Upbit and Bithumb) and one large global exchange (Binance). This exchange set covers the dominant liquidity pools relevant to the Korean premium, as Upbit and Bithumb jointly accounted for approximately 96% of trading volume among major Korean spot exchanges in 2024 [34], while Binance is the largest centralized exchange by spot trading volume, accounting for approximately 39% of global spot volume in 2024 [35]. By capturing the bulk of trading activity on both the Korean and global sides, this exchange set provides an experimental setting that is well suited for defining an asset universe aligned with Korean premium dynamics.

Over the collection window (2021–2024), we retrieve all assets available via these APIs (307 in total). We compute OHLCV features, a set of technical indicators, and KVSI, and assemble the dataset for the model’s state space. To reduce noise and keep the KVSI ablation comparison transparent, we standardize the technical indicator series and apply PCA-based dimensionality reduction to the technical indicator block. Finally, to limit the influence of extreme KVSI profiles, we perform clustering and retain the middle cluster of assets for the main experiments. The resulting 2021–2024 sample is then split into a 2021–2023 training set (75%) and a 2024 test set (25%) for the RL training and evaluation.

3.1. Data Collection

The raw data for this study were collected via the public REST APIs of Binance, Upbit, and Bithumb, from which we obtained daily OHLCV time series and exchange-level volume aggregates [36,37,38]. We built a Python (v3.9.7)-based pipeline that queried each exchange’s endpoints, standardized the responses to a common schema, and loaded them into a unified data lake. The implementation combined the Python HTTP libraries’ requests (v2.27.1) and aiohttp (v3.12.4) to enable asynchronous parallel collection, and included retry and session reactivation logic that respects exchange-specific rate limits and error codes. To ensure instrument concordance across venues, we mapped each exchange’s symbol convention to a common identifier (for example, Binance’s TICKERQUOTE, Upbit’s QUOTE-TICKER, and Bithumb’s TICKER were standardized to an asset-centric notation). For consistency in computing KVSI, we restricted the universe to spot instruments concurrently listed on all three exchanges and harmonized volumes by extracting the base asset-denominated volume field from each venue’s daily candle and summary endpoints.

The data generation pipeline proceeds as follows.

- Retrieve instrument metadata by exchange and construct a unified symbol mapping table.

- Collect daily OHLCV candles, prioritizing Binance first and otherwise preferring the longer available series.

- Resample to a daily calendar in UTC and perform gap handling for missing observations.

- For each asset, merge volumes from Binance, Upbit, and Bithumb to create the raw table used for KVSI computation.

This API-based collection framework ensures reproducibility and links naturally to subsequent preprocessing and feature engineering.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Raw OHLCV series for crypto assets are non-stationary and highly noisy, and they do not readily capture exchange-specific microstructure heterogeneity across venues. It is therefore necessary to engineer features that summarize predictive signals (such as momentum and volatility) and regional liquidity concentration, while reducing scale disparities and multicollinearity so as to enhance training stability and out-of-sample generalization.

The data preprocessing pipeline in this study proceeds as follows.

- Time ordering and harmonization of daily OHLCV.

- Computation of technical indicators.

- Computation of KVSI.

- Application of standardization fitted on the training window.

- PCA-based dimensionality reduction and noise attenuation applied only to the technical indicator block.

- Time order-preserving split (training on 2021–2023 and testing quarterly in 2024) and assembly of the final dataset injected into the RL model’s state space.

3.2.1. Technical Indicators

The state space in this study is constructed from a classical family of indicators representing trend, momentum, volatility, and overheating conditions. All indicators are computed from daily OHLCV and standardized using statistics estimated on the training window, which are then held fixed when applied to the test window to prevent data leakage. To reduce informational redundancy, only the technical indicator block is compressed via PCA, while the price-level variables (OHLCV) and the proposed indicator (KVSI) are retained in their original form to preserve interpretability.

First, the simple moving average (SMA) is a fundamental tool for trend estimation that smooths noise [39]. The formula is as follows.

Using short (5), medium (20), and long (60) windows in parallel allows simultaneous assessment of both the trend’s slope and the degree of alignment across multiple time scales. Rather than discrete golden/death cross flags, this study injects the continuous valued signals directly into the state space to reduce dependence on arbitrary thresholds.

The Relative Strength Index (RSI) [40] is a representative overheating indicator that measures the relative magnitude of upward and downward pressure. Its standard form with Wilder’s averaging is given by

and represent the average upward and downward movements over the most recent 14 periods, respectively, and the RSI is calculated based on the ratio of these two values.

Although the conventional 70/30 thresholds are widely used in practice, they are highly dependent on the asset and market regime. Accordingly, this study feeds the raw RSI as a continuous variable to reduce sensitivity to arbitrary cut-offs. In extreme cases where the denominator becomes zero, boundary rules are applied to ensure numerical stability.

MACD [41] captures trend momentum using the difference between short- and medium-term exponential moving averages. The exponential moving average (EMA) is defined as follows.

The MACD is calculated as the difference between the short-term and the medium-term . The MACD is defined as follows:

The signal is an exponential moving average of MACD that smooths short-term variation and is used to identify upward and downward crossovers.

Bollinger Bands [42] are standard deviation-based, volatility-adaptive envelopes that jointly capture mean reversion pressure and price stretch. The formulas for the center line and the upper and lower bands are as follows.

The center line (Middle(t)) represents the simple moving average over the most recent 20 periods (), while the standard deviation () reflects the price volatility over the same interval. The upper and lower bands (Upper(t) and Lower(t)) are defined as the mean plus or minus twice the standard deviation, respectively. A narrowing of the band (squeeze) signals a volatility trough and potential expansion, whereas a rapid widening suggests overheated or panic regimes.

The Stochastic oscillator [43] is a short-horizon overheating indicator that uses the current price’s relative position within the recent 14-day high-low range, defined as follows.

The highest and lowest prices over the most recent 14 periods are defined as and , respectively. represents the normalized position of the current price within a 0–100 range, while is calculated as the 3-period simple moving average (SMA) of .

Finally, momentum [44] is a short-term trend indicator computed as the difference between the current close and the close 10 periods earlier. The formula is as follows.

greater than zero indicates a dominant 10-period upward momentum, values below zero indicate downward momentum, and higher absolute magnitudes indicate a stronger force.

When employing the above indicator set in the experiments, the input variables adopt the baseline parameter choices used in practitioner standard sets that have been repeatedly validated across diverse market conditions, as commonly recommended in the cited references.

3.2.2. KVSI Computation

The Korean crypto asset market has historically shown a microstructure distinct from offshore exchanges due to institutional and structural factors such as restrictions on capital mobility, participant composition, and listing policies. This heterogeneity is often observed as the “Korean premium (Kimchi premium)”. In this setting, the relative trading volume of Korea-domiciled exchanges offers an observable summary of how strongly local demand and supply dominate global order flow at a given point in time. It also serves as an indicator that partially captures time-varying leadership in price discovery. To embed this insight directly into the RL state space, this study defines the KVSI as follows.

Here, , , and denote the daily trading volumes of asset i on each exchange. KVSI takes values in , so interpretation is straightforward: values closer to 1 indicate Korea-centered liquidity, whereas values closer to 0 indicate offshore-centered liquidity. Because it is defined as a relative share rather than an absolute volume, shifts in the overall market level (for example, concurrent volume surges during rallies or panics) are largely absorbed by this normalization. In a multi-listing structure for the same asset, KVSI therefore directly quantifies liquidity concentration across venues.

KVSI is attractive for three reasons. First, in terms of information efficiency and microstructure consistency, it aligns with prior evidence that contributions to price discovery are explained by relative trading volume and trading costs [9,10]. Relative volume is observable, easy to compute, and of high data quality, allowing it to proxy shifts in information leadership while avoiding measurement error issues inherent in trading cost variables such as spreads and fees. Second, for internalizing regional heterogeneity, the structural segmentation of the Korean market and the nonlinear dynamics of the premium suggest that the strength of regional order flow can affect both the speed and direction of price adjustment. KVSI summarizes this regional liquidity state as a single scalar and supplies it as input to the RL policy. Third, for policy interpretability, unlike PCA-compressed technical indicators, KVSI has a clear economic meaning, improving the interpretability of attention weights and policy responses (for example, exposure adjustments during rising KVSI regimes).

In implementation, trading volumes are taken as daily totals from the exchanges’ raw APIs or databases, and the construction includes only assets that are simultaneously listed on all three venues. In summary, KVSI translates insights from the literature on determinants of price discovery in cross-venue settings into a form tailored to the Korean market. As a regional liquidity concentration indicator, it provides a systematic channel for injecting heterogeneity information into RL-based trading decisions.

3.2.3. Feature Engineering

To promote stable learning and generalization of the RL policy, this study mitigates scale disparities and multicollinearity among input features in advance. Technical indicators for financial time series exhibit strong correlations because their calculation windows overlap, and they are measured in heterogeneous units. If used as-is, gradient-based optimization can overreact to large-magnitude features, and the covariance matrix may become ill-conditioned, resulting in unstable estimates. To address these issues, we harmonize feature scales via value normalization (standardization). We then apply principal component analysis (PCA) [45] only to the technical indicator block to remove low-variance, noise-like components.

Standardization is implemented as a z-score transformation using the mean and standard deviation estimated on the training window. For asset i, time t, and feature k, the transformation is

Here, and are fitted exclusively on the 2021–2023 training data, and during the 2024 test period only the transform is applied to prevent information leakage. Standardization aligns the center and dispersion of the input distribution, reducing gradient imbalance and accelerating convergence during training [46].

Denoising of the technical indicator block is performed via PCA. For the standardized indicator matrix , the sample covariance is computed as

with columns centered. From the eigendecomposition , the matrix is formed by the top k eigenvectors. The principal component representation of the observation at time t is then

This study sets , preserving approximately 92% of cumulative explained variance. Axes associated with small eigenvalues largely contain redundant or low-signal components and measurement noise. Removing them improves the signal-to-noise ratio and lowers the risk of overfitting through an effective reduction in parameter dimensionality. PCA also orthogonalizes correlations among indicators, mitigating ill-conditioning and stabilizing inputs to the policy and value networks. For interpretability and subsequent analysis of policy responses, OHLCV and KVSI are excluded from PCA.

In summary, value standardization removes heterogeneity in input scales to enhance optimization stability, while PCA reduces multicollinearity and noise among technical indicators to improve generalization. Both procedures are fitted solely on the training window and carried forward to the test window, thereby preserving temporal order and the causal information set of the RL environment.

3.3. Asset Universe Selection

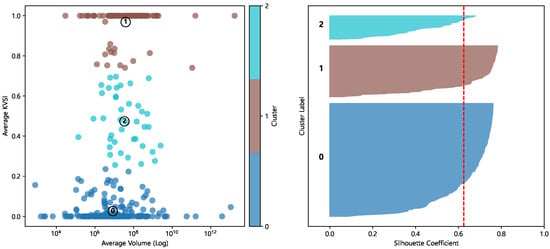

To preselect the test universe in a rule-based manner, this study applies k-means clustering [47] to a two-dimensional feature set comprising each asset’s average KVSI and the log of average daily trading volume. The clustering is fitted on statistics from the training window (2021–2023), and in the test year (2024) assets are assigned to the fixed centroids to prevent information leakage. The silhouette index [48] is used to assess the structural validity of the universe selection.

As shown in Figure 4, two of the three clusters lie in extreme regions where the mean KVSI is close to 0 or 1. We exclude the extreme KVSI clusters because they tend to reflect highly unbalanced venue dominance and venue-specific microstructure or listing frictions, and they can also increase instability by letting a small number of assets drive high variance. Accordingly, we retain only the middle-KVSI cluster for the reasons below.

Figure 4.

Clustering results (cluster 2 is retained) and the corresponding silhouette plot (red line = 0.62).

- Identification in an ablation design: The extreme clusters can exhibit KVSI values persistently close to 0 or 1, leading to limited time variation in the indicator. In this case, KVSI provides little incremental information relative to the baseline and the with-versus-without contrast becomes harder to identify cleanly.

- Control of confounders: The extreme clusters tend to rely excessively on listings and liquidity concentrated in a particular venue group, which elevates the influence of non-price factors such as trading halts, listing policies, and fee schedules. This can conflate price discovery with structural frictions and induce estimation bias. Focusing on the middle cluster mitigates confounding arising from microstructural idiosyncrasies.

- Generalization and stability: The extreme clusters often concentrate a small number of very large or very small assets, inflating variance and creating sample imbalance. Excluding these observations reduces variance in training and evaluation and increases within-cluster cohesion, improving the fairness of comparisons.

In summary, we map the structure of the KVSI-volume space using k-means clustering and, based on considerations of confounder control and generalizability, adopt only the middle-KVSI cluster as the test universe. Because this procedure is unsupervised and does not use return information (selection on covariates), this minimizes the risk of selection bias.

4. RL Framework and Evaluation Design

Using the 2021–2023 training set, we train three RL algorithms with an attention layer (PPO, A2C, and DQN) under two model specifications (with and without KVSI) so that the results do not hinge on a particular algorithm. We then evaluate each trained model on the 2024 test set and compute quarterly performance and risk metrics. Each RL algorithm and model specification is evaluated 30 times with different random seeds. The resulting quarterly outcomes for models with and without KVSI are first averaged across PPO, A2C, and DQN within each seed. We then compute 30 seed-level paired differences. Finally, we apply paired t-tests to assess whether including KVSI leads to statistically significant differences in performance.

4.1. Model Training

To avoid reliance on any single learning algorithm, this study trains three representative RL-based algorithms, PPO, A2C, and DQN, under a common architecture and preprocessing method, and later reports results by averaging across independent runs.

DQN [49] predicts an action value for each action with a neural network and selects the action with the highest value. Experiences are stored in a replay buffer and shuffled for reuse, which stabilizes training and improves sample efficiency. A2C [50] jointly trains an actor and a critic to learn both “what to do” and “how good it is.” It collects data from multiple environments in parallel and performs batched updates. Since collected data are not reused, sample efficiency can be lower depending on the setting. PPO [51] constrains the magnitude of policy updates and learns through small, incremental adjustments. This yields relatively stable training and is comparatively easy to tune. It often performs better than A2C in practice, though not universally.

RL algorithms in this study (PPO, A2C, and DQN) are implemented with the well-validated Stable-Baselines3 library. We follow the library defaults for hyperparameters, buffer management, and update pipelines, and we fix the total training budget to environment timesteps per algorithm for a transparent comparison. Table 2 summarizes the key default settings used in this study, and all remaining parameters follow the Stable-Baselines3 defaults.

Table 2.

Key Stable-Baselines3 default hyperparameters used for RL training.

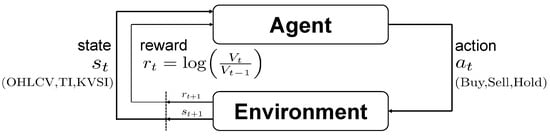

Figure 5 shows the agent–environment interaction, in which the environment provides a state , the agent selects an action , and the environment returns a reward together with the next state .

Figure 5.

Agent–environment interaction.

Algorithm 1 describes the learning procedure for all agents that share identical preprocessing. The state comprises principal components obtained from technical indicators together with KVSI and OHLCV. A lightweight attention layer is placed at the input front end. It estimates time-specific feature importance and passes a weighted representation to the policy and value networks. This improves the signal-to-noise ratio without complicating the architecture. The action space is discrete set {Buy, Sell, Hold}. The environment applies the chosen action at the next day’s open to avoid look-ahead bias. The per-step reward is the log return of the portfolio value (), which provides a dense and stable training signal, given by . On-policy algorithms (PPO, A2C) use a rollout buffer, and the off-policy algorithm (DQN) uses a replay buffer. When update conditions are met, parameters are updated according to each algorithm’s standard rules (PPO: clipped on-policy updates; A2C: synchronous actor–critic updates; DQN: replay and target network-based TD updates). All models share identical preprocessing methods, the same attention front end, equal network depth, and the same execution rule. This enables a fair comparison of learning dynamics.

| Algorithm 1 RL Training Loop |

| Input: asset set S with chosen RL algorithm attention feature extractor Let denote the portfolio value at the end of step t

|

4.2. Backtesting and Evaluation

Backtesting is conducted independently by quarter, and all algorithms and models operate under the same environment rules. A position decided at time t is executed at the next day’s open to eliminate look-ahead bias.

Transaction costs and slippage are not fully modeled in the main experiments, so the primary results are the reported gross of costs. As a robustness check, we additionally report fee-adjusted results that apply a 0.1% Binance spot trading fee.

For each algorithm and quarter, we run 30 trials with independent seeds, resulting in runs per model (PM and BM) per quarter. Asset-level metrics are first aggregated to portfolio-level outcomes by cross-sectional averaging across the 40 assets. For statistical inference, we then average the portfolio-level outcomes across the three RL algorithms within each seed, so that each quarter contributes 30 algorithm-averaged seed-level observations for PM and BM. Comparisons are carried out side by side for the proposed and baseline models under identical data, hyperparameters, and seeds to ensure an unbiased contrast.

Statistical significance is assessed by paired t-tests across seeds, after averaging performance across the three RL algorithms for each seed, comparing PM and BM for each quarter. Reproducibility is ensured by fixing quarters and seeds, applying common preprocessing, maintaining identical network depth and execution rules, and using the same reward definition.

4.2.1. Evaluation Metrics

Cumulative Return

Over a horizon of T days, the total compounded return of asset i is

This statistic captures the overall growth of a unit investment over the evaluation window. Higher values indicate better performance. For quarterly reporting, the same expression is computed using only the days within the quarter.

Sharpe Ratio [52]

Assuming a zero daily risk-free rate, let and denote the sample mean and standard deviation of daily returns . The annualized Sharpe ratio is

Since crypto assets trade 24/7 and returns are observed on all calendar days, is used as the annualization factor. For quarterly tables, and are computed from the quarter’s daily returns and the same annualization is applied. Higher Sharpe values indicate superior risk-adjusted performance.

Maximum Drawdown [53]

With the equity curve and the running peak , the maximum drawdown is

This measures the worst peak-to-trough loss over the horizon. Lower values are preferred. Quarterly MDD is computed using the same definition restricted to the quarter.

4.2.2. Benchmarks

To facilitate an objective comparison of the proposed model, we employ representative benchmarks commonly used in systematic trading research. All benchmarks adhere to the same execution rules and data splits and are evaluated with identical performance metrics.

Buy-and-Hold

All target assets are purchased at the start of the period and liquidated at the end. In this study, it serves as the market benchmark for the asset universe.

MA Crossover

To compare with a static model that relies on technical indicators, a simple moving average crossover strategy is used: when , when , and otherwise.

Random Trader

From the action set , actions are chosen with equal probability. Over the full sample, we generate 100 paths and report mean performance.

4.2.3. Statistical Analysis

For each quarter , RL algorithm , model , and metric , let denote the asset-level outcome for asset under seed .

We first form the cross-sectional mean across assets for each :

To reduce algorithm-specific idiosyncrasies and focus on the average effect of each model, we then average these means across the three RL algorithms for each model, quarter, and seed:

The paired difference between models for the same quarter and seed is then defined as

This yields paired observations per quarter (one algorithm-averaged observation per seed). The null hypothesis for each quarter is . Let

We report two-sided paired t-tests across seeds () with statistic

For the 2024 aggregate, we first average quarterly differences within each seed and then test across the resulting observations:

All tests are two-sided. We report p-values and indicate the , , and significance levels in the tables, and we provide confidence intervals (CIs) for the mean differences. Metrics are computed as cross-sectional means across the 40 assets for each algorithm and then averaged across PPO, A2C, and DQN within each seed before testing. Under this design, pairing is performed at the seed level () by comparing PM and BM under the same seed, while algorithm-specific variation is treated as a nuisance factor and absorbed into the within-seed averages.

5. Experimental Results and Discussion

5.1. Experimental Setup

The models are trained on 2021–2023 and evaluated quarterly in 2024. The test universe was classified in the two-dimensional KVSI-volume space using k-means () with a silhouette score of 0.62, and from the 307 assets for which we collected daily time series via public exchange APIs as of 31 May 2025, we selected 40 middle-KVSI assets as the test universe (see Table 3). PM includes KVSI as a state variable, whereas BM excludes it. The RL algorithms (PPO, A2C, and DQN) were trained for 500,000 steps per run. Execution occurs at the next day’s open to preclude look-ahead bias; the reward is defined as the day’s log return multiplied by the previously fixed position. For each quarter, the three RL algorithms are each run 30 times with independent seeds, yielding runs per model (PM and BM) per quarter. The evaluation metrics are CR, SR, and MDD.

Table 3.

Crypto assets (40) used in this study.

5.2. Results and Discussion

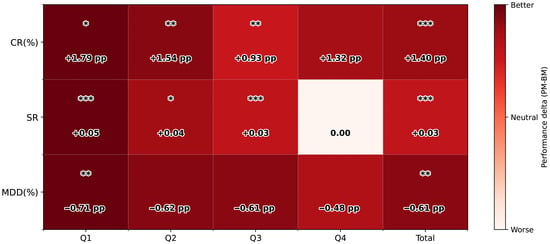

Table 4 evaluates, for each model–quarter result set, PM versus BM using paired t-tests. Aggregating the full year 2024, the pooled tests show that PM achieves a CR of 18.66%, an SR of 0.24, and an MDD of 28.10%, improving on BM’s 17.26%, 0.21, and 28.71%. Algorithm-specific performance tables for PPO, A2C, and DQN are reported in Appendix A Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3. All three metrics are statistically significant at the 5% level (CR p = 0.0046, SR p = 0.0002, MDD p = 0.0366). Figure 6 visualizes the quarterly result tables as a heatmap to aid interpretation. Color hues encode the quarter-by-quarter mean performance difference between PM and BM, and significance markers are overlaid within each cell. CR and SR show consistent positive improvements in Q1–Q3. For MDD, improvements (lower drawdowns) appear in all quarters, but only Q1 is statistically significant. Quarterly results are as follows.

Table 4.

Performance comparison: PM vs. BM.

Figure 6.

Heatmap of PM–BM differences. Deeper red indicates PM improvement. * , ** , *** .

- Q1: PM shows CR 34.23%, SR 0.73, and MDD 24.11%. Compared with BM (32.44%, 0.68, 24.82%), CR shows a marginal increase (p = 0.0959), SR improves significantly (p = 0.0040), and MDD is significantly lower (p = 0.0430).

- Q2: Both models incur losses. PM’s CR (−26.75%) is less negative than BM’s (−28.29%) (p = 0.0437). SR shows a small, marginal improvement from −0.85 to −0.81 (p = 0.0538), and the MDD difference is not statistically significant.

- Q3: PM shows CR −1.28%, SR 0.11, and MDD 23.60%. Relative to BM (−2.21%, 0.07, 24.21%), CR (p = 0.0132), and SR (p = 0.0053) improve significantly, while the MDD difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.2438).

- Q4: PM’s CR is slightly higher (68.43% vs. 67.11%), and SR and MDD are similar. All differences in Q4 are non-significant.

Table 5 reports fee-adjusted (net) performance under a 0.1% Binance spot trading fee for both BM and PM, together with the paired differences () and statistical tests. The fee adjustment lowers the absolute returns of both models, as expected, but the incremental differences remain in the same direction as in the gross results. In particular, the net values remain positive for CR and SR and indicate improved drawdown behavior for MDD, and the corresponding significance levels remain consistent with the main findings.

Table 5.

Transaction-fee-adjusted performance comparison (net-of-fee): PM vs. BM.

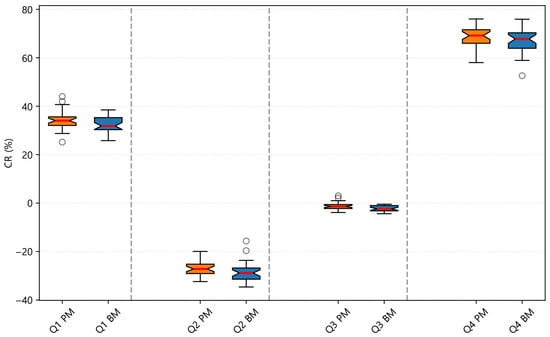

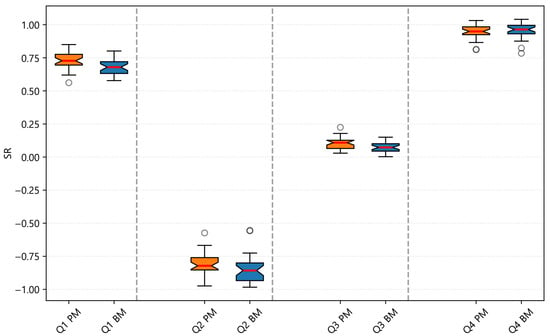

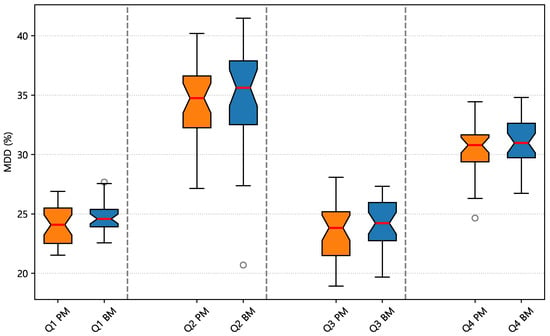

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present notch box plots for CR, SR, and MDD, comparing PM and BM. The notch around each median approximates a 95% confidence interval. When the notches do not overlap, the difference in medians is likely.

Figure 7.

Notch box plot for CR (%). White circles indicate outliers.

Figure 8.

Notch box plot for SR. White circles indicate outliers.

Figure 9.

Notch box plot for MDD (%). Lower median is better. White circles indicate outliers.

- CR (Figure 7): Across all quarters, PM’s median CR is slightly higher than BM’s. In Q2, which is a down market, PM shows smaller losses, while in Q4, a strong up quarter, PM and BM medians are similar, indicating comparable upside capture.

- SR (Figure 8): From Q1 to Q3, PM’s median SR is higher than BM’s, but overlapping notches indicate that the improvement is modest. In Q4, PM and BM display similar medians and interquartile ranges.

- MDD (Figure 9): In every quarter, PM’s median MDD is lower than BM’s, with the difference most visible in Q2. However, overlapping notches suggest that the gap is limited, and long upper whiskers in Q2 and Q4 indicate episodes of larger drawdowns for both models.

Table 6 compares the models with standard benchmarks (MA Crossover, Buy-and-Hold, Random Trader) to gauge absolute performance. Performance differences are defined as . Relative to Buy-and-Hold, PM shows , , and , indicating higher CR and SR with a lower MDD. Relative to MA Crossover, PM records and , while , and CR and SR are higher, but MDD is higher. Relative to Random Trader, PM attains , , and , indicating higher CR, comparable SR, and a lower MDD. Overall, PM delivers modest improvements in CR and generally higher or comparable SR across benchmarks, with mixed effects on MDD.

Table 6.

Performance comparison: PM vs. benchmarks.

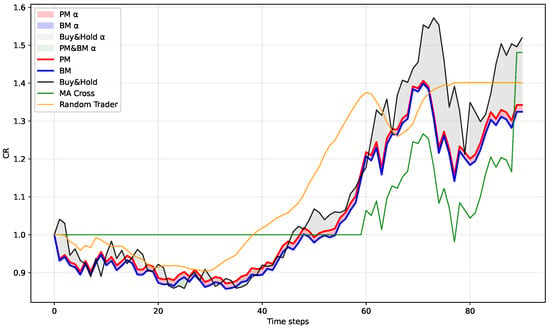

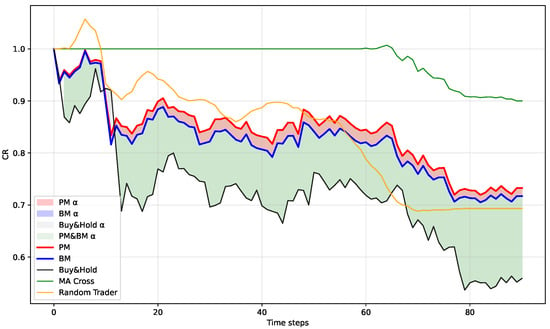

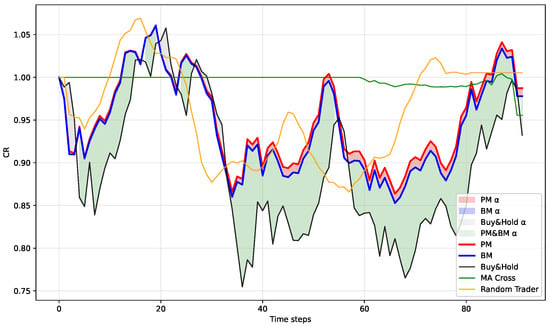

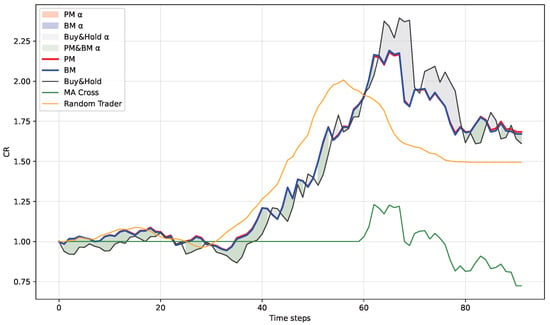

Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 show time series of quarterly CR for the benchmarks and for PM and BM. Buy-and-Hold is used as the market reference, and the shaded regions highlight periods where PM and BM generate positive or negative excess CR relative to Buy-and-Hold. Buy-and-Hold serves as the reference because it most simply represents the average market trend of the study universe (the 40 assets in the middle-KVSI cluster).

Figure 10.

Curve of CR in Q1: PM vs. BM vs. benchmarks.

Figure 11.

Curve of CR in Q2: PM vs. BM vs. benchmarks.

Figure 12.

Curve of CR in Q3: PM vs. BM vs. benchmarks.

Figure 13.

Curve of CR in Q4: PM vs. BM vs. benchmarks.

- Q1 (Figure 10): In an upward regime with intermittent corrections, PM is marginally above BM for much of the quarter, while both remain below the market benchmark (Buy-and-Hold) in CR.

- Q2 (Figure 11): In a pronounced downturn, PM generally maintains higher CR than BM for most of the quarter; both models are less negative than the market benchmark.

- Q3 (Figure 12): In a range-bound regime, PM edges above BM from mid-quarter and, for most of the period, both are at or above the market benchmark in CR.

- Q4 (Figure 13): In a strong uptrend, PM and BM track the market benchmark with no material separation, and all three exhibit high CR.

Taken together, the quarterly curves suggest that the incremental value of KVSI is concentrated in non-trending regimes. In Q2, PM reduces losses and stabilizes earlier than BM, consistent with KVSI helping the policy adjust exposure when segmentation intensifies. In Q3, PM also shows a lower maximum drawdown than BM. This indicates that, in the range-bound regime, the peak-to-trough loss is smaller when KVSI is included in the state space. A plausible interpretation is that KVSI summarizes time-varying venue-level liquidity concentration, which the learned policy can use as an additional state cue when adjusting exposure under non-trending market conditions. In Q4, PM and BM perform similarly in a strong market upswing, which is consistent with the weaker marginal role of venue-share information when returns are dominated by broad market direction rather than local order imbalance.

5.2.1. Economic Intuition Behind KVSI and Market Regime Dependence

KVSI can be interpreted as a compact proxy for venue-level liquidity concentration and the relative intensity of Korean order flow. When Korean exchanges account for a larger share of trading in a given asset, this often reflects localized demand or supply shocks and, more broadly, the concentration of attention and trading activity within a regional investor base. Under limits to arbitrage, such localized shocks can widen cross-venue price gaps and temporarily shift price discovery leadership toward the venues where trading activity is concentrated. In this setting, KVSI can carry incremental information about near-term return and risk conditions that may not be fully captured by price-based technical indicators alone. Notably, KVSI captures where trading intensity concentrates rather than the direction of trades, so its predictive content is naturally state-dependent and is learned through the joint conditioning on price, volatility, and other state variables in the RL policy.

This interpretation is consistent with the regime patterns observed in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. In downturns and higher-volatility phases, arbitrage capital tends to be more constrained and liquidity fragmentation becomes more pronounced, so venue-share shifts provide stronger incremental signals. A KVSI-aware policy can therefore adjust exposure more effectively, which is reflected in smaller losses and improved risk outcomes in the more adverse quarters. In contrast, in strong uptrends, common global factors dominate and cross-venue prices tend to co-move more tightly, reducing segmentation-driven opportunities and weakening the incremental contribution of KVSI.

5.2.2. Generalization to Other Regions and Policy Relevance

Although KVSI is motivated by the Korean premium, the underlying idea is not specific to Korea. KVSI can be viewed as a compact proxy for time-varying liquidity concentration across segmented venue groups. Therefore, similar venue-share indicators can be constructed for other regional markets where cross-venue participation is uneven and arbitrage capacity is time-varying.

Operationally, a country-specific venue share indicator can be defined by (i) selecting a set of domestic exchanges that provides high coverage of the region’s spot trading activity, (ii) choosing a global reference exchange with deep liquidity and stable data access, and (iii) restricting the asset universe to commonly listed assets to ensure cross-venue comparability. The resulting indicator can then be injected into the trading agent’s state space and evaluated using the same pipeline in Section 3 and Section 4, including the controlled with-versus-without ablation design and out-of-sample testing.

From a policy and market design perspective, the fact that a simple venue-share proxy carries incremental trading value suggests that cross-border information flow and arbitrage are not frictionless, and that regulatory and institutional constraints can sustain segmentation. If such frictions are relaxed, for example through greater cross-venue access, fewer transfer constraints, or broader availability of globally accessible exchange-traded products, persistent price gaps such as the Korean premium could compress, which would likely reduce the informativeness of KVSI over time. We do not conduct a formal event study, but several 2024 developments provide context for why venue-share dynamics may vary over time. For example, in early 2024 the approval of U.S. spot Bitcoin ETFs may have altered global participation and liquidity conditions, the April 2024 Bitcoin halving coincided with heightened uncertainty and repositioning that can amplify cross-venue heterogeneity, and the July 2024 implementation of Korea’s Virtual Asset User Protection Act may have affected domestic market conditions. These episodes are consistent with the quarter-level evidence that KVSI is more informative in volatile or declining phases, such as Q2 and Q3, than in persistent uptrends.

6. Concluding Remarks

This study introduces KVSI as an interpretable indicator of regional heterogeneity in cross-venue crypto markets and uses it as an additional state variable in RL trading models. All models share the same data, preprocessing, execution rule, and reward definition. The only difference between PM and BM is the inclusion of KVSI in the state space, which allows its incremental contribution to be isolated.

At the annual level, PM (with KVSI) achieves statistically significant improvements over BM (without KVSI) in CR, SR, and MDD, with , respectively (). The fee-adjusted robustness check that applies a 0.1% Binance spot trading fee yields qualitatively consistent results and supports the same conclusion. By quarter, CR and SR improvements are consistently positive and often statistically significant in Q1–Q3, with CR improving significantly in Q2, while differences largely wash out in the strongly trending Q4. The quarterly CR curves against Buy-and-Hold suggest a clear dependence on market regime. Alpha tends to widen in range-bound and declining regimes, remain modest in gentle advances with intermittent corrections, and narrow in pronounced uptrends. This regime dependence supports interpreting KVSI as a proxy for venue-level liquidity concentration that becomes most informative when segmentation frictions and limits to arbitrage are binding. More broadly, the same venue-share construction can be applied to other regional exchange clusters, providing a practical template for cross-market systematic trading and a policy-relevant lens on how market integration can compress segmentation-driven opportunities.

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, it directly models market segmentation: by quantifying cross-exchange relative liquidity with a single scalar indicator (KVSI) and integrating it into the RL state space, the models link regional market differences to trading decisions in a transparent way. Second, it identifies a clear effect of information expansion: a parallel comparison under identical networks, preprocessing, execution rules, and reward definitions, differing only in the information set (presence of KVSI), allows statistical analysis of the impact of expanding the state space rather than artifacts of algorithms or implementation. Third, it emphasizes reproducibility and interpretability: independent quarterly evaluation with three RL algorithms and 30 independent seeds, paired t-tests with 95% confidence intervals based on seed-level observations, and additional distributional and curve-based evidence together increase confidence in the results and keep the design transparent.

This study has several limitations. Since the trading policies are learned by RL algorithms, it does not fully characterize how KVSI shapes policy decisions across states beyond preliminary inspection of attention weights and selected trajectories. In addition, while we include an explicit fee-adjusted robustness check based on a 0.1% Binance spot trading fee, other trading frictions such as bid–ask spreads, market impact, and slippage are not modeled. Therefore, the backtest results should be interpreted as benchmark evidence on the incremental informational contribution of KVSI under a controlled execution setting. Finally, the out-of-sample evidence is based on a single test year (2024). Although this window was chosen to cover diverse market regimes, future work should validate the KVSI effect over additional test periods to assess generalizability.

Future research could extend this framework in several ways. One direction is to move beyond the Korean premium by defining and validating country-specific venue share indicators based on regional exchange shares—for example, a China Venue Share Indicator (CVSI)—and by exploring multi-indicator state spaces that capture multi-regional heterogeneity under more realistic trading frictions. Another direction is to analyze how the policy uses KVSI by comparing behavior and outcomes across regimes and by testing sensitivity with frozen-policy rollouts and simple randomization checks. This direction can be complemented by explainable AI methods to better characterize how the learned policies use KVSI across different market states. In addition, future work could also examine the information diffusion and collective action mechanisms that may underlie KVSI using social network analysis of crypto asset-related social media. Such analysis can quantify connectivity, centrality, and information isolation between the Korean community and global participants, which may help clarify how venue-level segmentation affects price discovery and systematic trading performance.

In conclusion, a small and transparent intervention that adds one interpretable indicator (KVSI) to the state space can improve RL trading performance and risk metrics in this setting. The study’s design and procedures provide a basis for extending venue-level indicators to other regional markets and for drawing more general conclusions about the role of cross-venue liquidity segmentation in systematic crypto asset trading.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H. and Y.K.; methodology; validation; data curation; writing—original draft preparation, D.H.; writing—review and editing, D.H. and Y.K.; supervision, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this paper can be obtained from Binance API, Upbit API, and Bithumb API.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PM | Proposed Model |

| BM | Baseline Model |

| KVSI | Korean Venue Share Indicator |

| TI | Technical Indicator |

| OHLCV | Open, High, Low, Close, and Volume |

| CR | Cumulative Return |

| SR | Sharpe Ratio |

| MDD | Maximum Drawdown |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| A2C | Advantage Actor–Critic |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Algorithm-specific performance: PPO (PM vs. BM).

Table A1.

Algorithm-specific performance: PPO (PM vs. BM).

| Quarter | Metric | PM (Mean ± sd) | BM (Mean ± sd) | (PM − BM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | CR (%) | 37.99 ± 7.63 | 33.30 ± 5.70 | +4.69 pp |

| SR | 0.81 ± 0.11 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | +0.13 | |

| MDD (%) | 23.59 ± 3.16 | 25.58 ± 1.62 | −1.99 pp | |

| Q2 | CR (%) | −27.21 ± 6.33 | −30.59 ± 6.37 | +3.38 pp |

| SR | −0.82 ± 0.13 | −0.92 ± 0.14 | +0.11 | |

| MDD (%) | 35.42 ± 6.42 | 37.26 ± 6.44 | −1.84 pp | |

| Q3 | CR (%) | −0.55 ± 3.27 | −1.53 ± 3.13 | +0.98 pp |

| SR | 0.15 ± 0.09 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | +0.04 | |

| MDD (%) | 26.60 ± 2.83 | 26.58 ± 2.77 | +0.02 pp | |

| Q4 | CR (%) | 74.46 ± 8.31 | 72.03 ± 6.71 | +2.43 pp |

| SR | 1.02 ± 0.07 | 1.04 ± 0.07 | −0.02 | |

| MDD (%) | 29.90 ± 3.35 | 31.41 ± 3.26 | −1.51 pp | |

| Total (2024) | CR (%) | 21.17 ± 3.63 | 18.30 ± 2.53 | +2.87 pp |

| SR | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | +0.07 | |

| MDD (%) | 28.88 ± 2.18 | 30.21 ± 1.94 | −1.33 pp |

Values are rounded. uses unrounded means.

Table A2.

Algorithm-specific performance: A2C (PM vs. BM).

Table A2.

Algorithm-specific performance: A2C (PM vs. BM).

| Quarter | Metric | PM (Mean ± sd) | BM (Mean ± sd) | (PM − BM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | CR (%) | 41.90 ± 4.30 | 42.15 ± 3.78 | −0.25 pp |

| SR | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0.00 | |

| MDD (%) | 26.02 ± 1.12 | 26.50 ± 1.06 | −0.48 pp | |

| Q2 | CR (%) | −34.76 ± 3.90 | −36.92 ± 2.45 | +2.16 pp |

| SR | −0.93 ± 0.11 | −1.00 ± 0.06 | +0.07 | |

| MDD (%) | 42.63 ± 2.66 | 44.01 ± 2.36 | −1.38 pp | |

| Q3 | CR (%) | −4.76 ± 1.52 | −5.75 ± 1.16 | +0.99 pp |

| SR | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.00 ± 0.03 | +0.03 | |

| MDD (%) | 29.67 ± 1.23 | 30.05 ± 0.74 | −0.38 pp | |

| Q4 | CR (%) | 72.02 ± 4.83 | 73.67 ± 5.17 | −1.65 pp |

| SR | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.04 | −0.01 | |

| MDD (%) | 34.50 ± 1.97 | 34.86 ± 1.60 | −0.36 pp | |

| Total (2024) | CR (%) | 18.60 ± 2.27 | 18.29 ± 1.76 | +0.31 pp |

| SR | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | +0.02 | |

| MDD (%) | 33.20 ± 0.88 | 33.85 ± 0.80 | −0.65 pp |

Values are rounded. uses unrounded means.

Table A3.

Algorithm-specific performance: DQN (PM vs. BM).

Table A3.

Algorithm-specific performance: DQN (PM vs. BM).

| Quarter | Metric | PM (Mean ± sd) | BM (Mean ± sd) | (PM − BM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | CR (%) | 22.80 ± 7.33 | 21.86 ± 8.33 | +0.94 pp |

| SR | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 0.52 ± 0.16 | +0.04 | |

| MDD (%) | 22.72 ± 3.93 | 22.40 ± 3.30 | +0.32 pp | |

| Q2 | CR (%) | −18.27 ± 7.31 | −17.34 ± 8.95 | −0.93 pp |

| SR | −0.69 ± 0.23 | −0.63 ± 0.27 | −0.06 | |

| MDD (%) | 24.57 ± 7.97 | 23.19 ± 10.00 | +1.38 pp | |

| Q3 | CR (%) | 1.48 ± 1.92 | 0.66 ± 1.95 | +0.82 pp |

| SR | 0.14 ± 0.09 | 0.11 ± 0.07 | +0.03 | |

| MDD (%) | 14.53 ± 5.74 | 16.00 ± 6.21 | −1.47 pp | |

| Q4 | CR (%) | 58.81 ± 10.00 | 55.63 ± 11.59 | +3.18 pp |

| SR | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 0.81 ± 0.14 | +0.02 | |

| MDD (%) | 27.08 ± 5.67 | 26.65 ± 5.15 | +0.43 pp | |

| Total (2024) | CR (%) | 16.20 ± 2.99 | 15.20 ± 3.66 | +1.00 pp |

| SR | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | +0.01 | |

| MDD (%) | 22.22 ± 2.66 | 22.06 ± 3.28 | +0.16 pp |

Values are rounded. uses unrounded means.

References

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Statement on the Approval of Spot Bitcoin Exchange-Traded Products. 10 January 2024. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/speeches-statements/gensler-statement-spot-bitcoin-011023 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing. HKEX Welcomes Asia’s First Spot Virtual Asset ETFs. 30 April 2024. Available online: https://www.hkex.com.hk/News/News-Release/2024/240430news (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Order Granting Accelerated Approval of Proposed Rule Changes to List and Trade Shares of Ether-Based Exchange-Traded Products. 23 May 2024. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/sro/nysearca/2024/34-100224.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Reuters. Global Crypto ETFs Attract Record 5.95 Billion as Bitcoin Scales New Highs. Reuters. 7 October 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/global-crypto-etfs-attract-record-595-billion-bitcoin-scales-new-highs-2025-10-07/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Yahoo Finance. BlackRock’s IBIT Is Nearing $100B in AUM. Everyone Else Might Be Chasing ‘Crumbs’. 13 October 2025. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/blackrock-ibit-nearing-100b-aum-101000792.html (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Makarov, I.; Schoar, A. Trading and arbitrage in cryptocurrency markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandvold, M.; Molnár, P.; Vagstad, K.; Valstad, O.C.A. Price discovery on Bitcoin exchanges. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2015, 36, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutmos, D. Nothing but noise? Price discovery across cryptocurrency exchanges. J. Financ. Mark. 2021, 54, 100584. [Google Scholar]

- Entrop, O.; Frijns, B.; Seruset, M. The determinants of price discovery on bitcoin markets. J. Futur. Mark. 2020, 40, 816–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Heck, D.F. Price discovery in Bitcoin: The impact of unregulated markets. J. Financ. Stab. 2020, 50, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chainalysis. The 2024 Geography of Crypto Report; Chainalysis: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.chainalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/the-2024-geography-of-crypto-report-release.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Seo, M.H.; Koo, B.; Yang, Y.F. Nonlinear dynamics of Kimchi premium. Econ. Model. 2024, 135, 106726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Oh, T. The Kimchi premium and bitcoin-cashing outlets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Gonçalves, T.C. Cryptocurrency Market Microstructure: A Systematic Literature Review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 332, 1035–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Ventre, C.; Basios, M.; Kanthan, L.; Martinez-Rego, D.; Wu, F.; Li, L. Cryptocurrency trading: A comprehensive survey. Financ. Innov. 2022, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Failler, P.; Wang, Z. The Dynamic Evolution of Agricultural Trade Network Structures and Its Influencing Factors: Evidence from Global Soybean Trade. Systems 2025, 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Oh, M.-S. Discovering causal relationships among financial variables associated with firm value using a dynamic Bayesian network. Data Sci. Financ. Econ. 2025, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, D.F.; Bouri, E.; Ramezanifar, E.; Roubaud, D. The profitability of technical trading rules in the Bitcoin market. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 34, 101263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.; Urquhart, A. Technical trading and cryptocurrencies. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 297, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudy, M.; Kaplanski, G.; Mugerman, Y. Market timing with moving average distance: International evidence. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2024, 97, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, D.-G. A reality check on trading rule performance in the cryptocurrency market: Machine Learning vs. technical analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 39, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Liang, J. Cryptocurrency portfolio management with deep reinforcement learning. In 2017 Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 905–913. [Google Scholar]

- Raffin, A.; Hill, A.; Gleave, A.; Kanervisto, A.; Ernestus, M.; Dormann, N. Stable Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Malik, A. Reinforcement Learning Pair Trading: A Dynamic Scaling Approach. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Bitcoin Trend Prediction with Attention-Based Deep Learning Models and Technical Indicators. Systems 2024, 12, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Temporal Fusion Transformer-Based Trading Strategy for Multi-Crypto Assets Using On-Chain and Technical Indicators. Systems 2025, 13, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natashekara, K.; Sampath, A. Informed trading and cryptocurrencies: New evidence using tick-by-tick data. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 104909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.H.; Borwein, J.M.; López de Prado, M.; Zhu, Q.J. Pseudo-Mathematics and Financial Charlatanism: The Effects of Backtest Overfitting on Out-of-Sample Performance. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2014, 61, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, R.; Harvey, C.R.; Markowitz, H. A Backtesting Protocol in the Era of Machine Learning. J. Financ. Data Sci. 2019, 1, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P.; Islam, R.; Bachman, P.; Pineau, J.; Precup, D.; Meger, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning that Matters. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-18); McIlraith, S.A., Weinberger, K.Q., Eds.; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 32, pp. 3207–3214. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Gong, X.; Si, Y.-W. Transaction-aware inverse reinforcement learning for trading in stock markets. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 28186–28206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koker, T.E.; Koutmos, D. Cryptocurrency trading using machine learning. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondo, A.E.; Pluchino, A.; Rapisarda, A.; Helbing, D. Are random trading strategies more successful than technical ones? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M. State of the Korean Crypto Market. Presto Research. 2024. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/m1hizt3hapq0/5iuKmeyAhiY0wuFqhb1Y0m/6ce52cae007fa23c47788242e590cb06/State_of_the_Korean_Crypto_Market.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Lee, S.P. Crypto Trading Volumes Reached $18.83T in 2024, Still Below 2021’s $25.21T Peak. CoinGecko Research. 2025. Available online: https://www.coingecko.com/research/publications/largest-centralized-crypto-exchanges (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Binance. Binance Spot API Documentation. Available online: https://developers.binance.com/docs/binance-spot-api-docs/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Upbit. Upbit Open API Reference. Available online: https://docs.upbit.com/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Bithumb. Bithumb Public API Documentation. Available online: https://apidocs.bithumb.com/ (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Brock, W.; Lakonishok, J.; LeBaron, B. Simple Technical Trading Rules and the Stochastic Properties of Stock Returns. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 1731–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, J.W., Jr. New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems; Trend Research: Greensboro, NC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, G. Technical Analysis: Power Tools for Active Investors; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger, J. Bollinger on Bollinger Bands; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, G.C. Lane’s Stochastics. Tech. Anal. Stock. Commod. 1984, 2, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pring, M.J. Technical Analysis Explained: The Successful Investor’s Guide to Spotting Investment Trends and Turning Points, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, J. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 1: Statistics; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Badia, A.P.; Mirza, M.; Graves, A.; Lillicrap, T.P.; Harley, T.; Silver, D.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Asynchronous Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2016); Balcan, M.F., Weinberger, K.Q., Eds.; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 48, pp. 1928–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W.F. The Sharpe Ratio. J. Portf. Manag. 1994, 21, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R.; Mahmoud, O. Drawdown: From Practice to Theory and Back Again. Math. Financ. Econ. 2017, 11, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.