Abstract

The green transformation of agricultural systems is crucial for environmental protection and food security, yet smallholder-dominated systems face immense structural barriers. This study investigates whether agricultural socialized services (ASSs)—an emerging institutional innovation—can serve as a catalyst for this transition. Using household survey data from the China Land Economy Survey (CLES), this study examines the direct impact and mediating pathways of ASSs on farmers’ adoption of green production behaviors. We also reveal the heterogeneity effects of household operating scale. The results show the following: (1) Agricultural socialized services positively impact farmers’ adoption of green production behaviors, which can contribute to advancing sustainable agricultural development. (2) ASSs do not simply increase the quantity of machines. Instead, they facilitate a shift from costly asset ownership to efficient mechanization-as-a-service. (3) Furthermore, a heterogeneity analysis reveals that the positive impacts of ASSs are heterogenous at different levels. ASSs more significantly influence farmers’ adoption of green practices for small-scale farms (operating at a size less than 4.8 mu). It provides robust empirical evidence that ASSs can effectively “decouple” green modernization from large-scale farmers to overcome structural barriers. These findings help to provide policy implications for promoting ASSs and sustainable agriculture production.

1. Introduction

The long-term challenges faced by the agricultural system, such as the excessive use of chemicals and overdevelopment of farmland, have led to severe farmland degradation and environmental pollution, posing a significant threat to planetary boundaries, the harmony of human–land relations, global food security, and ecological sustainability [1]. Therefore, catalyzing a system-wide transformation towards a green and sustainable mode has become a global consensus and an urgent need [2]. Sustainable Development Goal 2.4 (SDG-2.4) issued by the United Nations points out that by 2030, a sustainable food production system should be established to increase productivity and yield, maintain ecosystems, and gradually improve land and soil quality.

At the heart of this systemic challenge lies the behavior of its core stakeholders: farmers. In China, as elsewhere, the aggregate decisions made at the farm level influence the macro-level performance of the entire agricultural production system. However, the current adoption rate of green agricultural practices (such as green prevention and control technologies) at the farmer level in China has yet to be improved [3]. As the main body of the agricultural production system, the greening of farmers’ production behaviors is directly related to the effectiveness of the broader organizational transition of agriculture towards sustainability [4].

The green production behavior of farmers is a complex decision-making system, composed of multiple, interconnected subsystems. Existing research indicates that these influencing factors include farmers’ subjective perceptions (such as environmental concerns and awareness of green production) [5,6], individual characteristics (such as age and educational attainment) [7], risk perception [8], capital endowment [9], scale of farmland production [2], and technological advancements related to agricultural productivity, especially the role of agricultural mechanization in enhancing the green total factor productivity of agriculture [10,11]. While these studies have mapped the components, they often analyze them in isolation. A holistic, systems thinking perspective on how these elements interact, create feedback loops, and respond to external interventions is still profoundly lacking.

Against this background, agricultural socialized services (ASSs), as a market-oriented service system, provide a new opportunity to optimize the agricultural production system and guide farmers to adopt green production methods [12]. We conceptualize ASSs not just as services, but as a form of organizational innovation and a sustainable business model that facilitates a wider sectoral transition. This service system, by integrating resources and providing professional services, can influence farmers’ decisions and practices in all links of agricultural production [13]. In order to improve the quality and efficiency of agricultural production, the Chinese government has promoted the development of ASSs. Existing studies have preliminarily confirmed the positive impact of specific socialized services (such as mechanical outsourcing services) on farmers’ adoption of green production technologies [4]. Meanwhile, some studies have also showed that agricultural socialized services would have promoting effects on specific green production behaviors, such as reducing the use of chemical fertilizer [14] and the adoption of organic fertilizers [8].

However, the above studies often suffer from a reductionist view, hindering a full understanding of the systematic impact of ASSs on farmers’ green production behaviors. First of all, agricultural production itself is a complex system that runs through multiple links including pre-production, production, and post-production. Previous studies have mostly focused on a single service type [4] or a specific production link [8,14], failing to capture the emergent properties and synergistic effects of ASSs as a holistic intervention. Secondly, the analysis of the internal mechanism by which ASSs as a sustainable strategy drives farmers’ green production behaviors by influencing other elements in the agricultural production system, such as the level of agricultural mechanization, is still insufficient. This cognitive limitation on the systemic role and mechanism of ASSs hinders our effective design and promotion of ASSs to comprehensively promote the organizational transition towards a green economy in agriculture.

To fill the research gap, this study aims to construct an analytical framework that conceptualizes the ASS–mechanization–adoption nexus as an interconnected system, providing a real-world case study of organizational transition for sustainability. Based on the filed survey data of 1839 farmers from the China Land Economic Survey (CLES) in 2020–2022, this study systematically examined the heterogeneity of the impact of ASSs on the green production behavior of farmers. In the first, the probit model and logit model are used to test the direct effect of ASSs on green production behavior. Next, in order to eliminate self-selection bias, this study uses the PSM model, including an ATT test and balance test, to examine the robustness of the results. Moreover, the generalized structural equation model (GSEM) is used to inspect the structural relationships and mediating pathways within the system, with a focus on the role of mechanization. Finally, the heterogeneity of different farmers in the main effect is also tested.

2. Theoretical Hypothesis

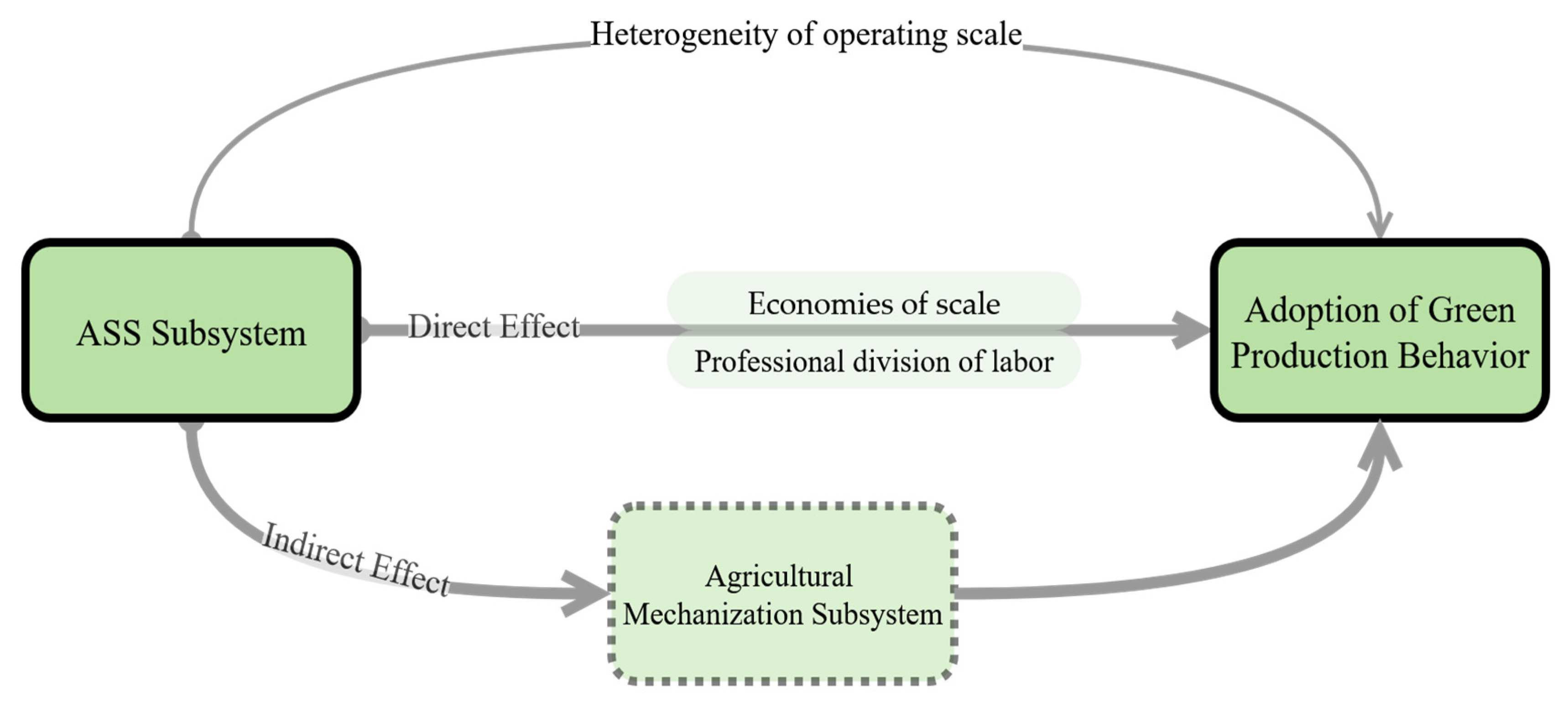

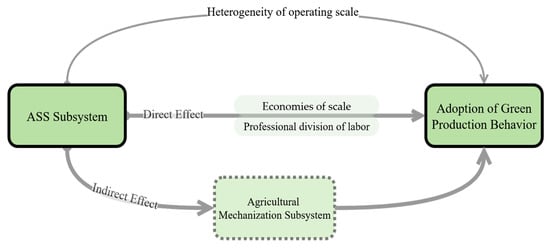

The transition to an agricultural green production model is essentially a process of systematic reconfiguration, which transforms the farm production system from a state of high resource consumption and environmental externality to one that is efficient, resilient, and in harmony with the ecology [5]. However, this transformation is often hindered by the inherent structural obstacles of the traditional small-scale farmers’ agricultural production system. The ASSs not only provide inputs, but also act as catalysts and organizational forces, reconfiguring the entire production system. In this section, we construct a conceptual model to depict the system path adopted by ASSs to guide green production behaviors, with a particular focus on the mediating role of the agricultural mechanization subsystem (Figure 1). The agricultural socialized service subsystem can provide specialized outsourced services for specific production stages, thereby enhancing the specialization level of agricultural production and amplifying economies of scale. This directly drives the green transition of farmers’ production methods. Agriculture’s mechanization subsystem plays a critical mediating role in this process. The ASSs provide outsourced services for agricultural machinery, while the utilization of such machinery for precision operations, including targeted pesticide application, conservation tillage, and no-till farming, indirectly fosters the adoption of green production practices. This transition reflects a shift among farmers from acquiring high-cost asset ownership toward purchasing the economically accessible mechanization-as-a-service model.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework.

2.1. The ASS Subsystem as a Catalyst for Green Production Behavior

Different from traditional agricultural production, agricultural green production (AGP) behaviors are influenced by a variety of factors, including economic efficiency, environmental protection, and social development [5]. Generally, any production subject that adopts multiple environmental-friendly production behaviors can be recognized as engaging in agricultural green production. The purpose is to increase crop yield, minimize resource inputs, reduce carbon emissions, and prevent degradation [15,16]. Specific green production behaviors include farmland quality protection, fertilizer and pesticide reduction, waste recycling, etc. Naturally, it meets SDG-2.4 requirements for sustainable production.

Among these various factors, ASSs promote farmers’ involvement in the agricultural green revolution [17]. On the one hand, ASSs enable farmers to maintain agricultural production by outsourcing services rather than transferring land use rights, thereby safeguarding tenure security [18]. Farmers with optimistic expectations for future returns are more likely to operate farmland [19] and invest in green production technologies. Furthermore, ASSs, functioning as a specialized form of scaled service, can effectively lower production costs through economies of scale [20]. Therefore, agricultural scaling should be pursued simultaneously with the scaling of agricultural service operations [21]. In the traditional mode of agriculture production, farmers may be unable to afford the high costs associated with new technologies. However, economies of scale lower the costs of outsourced services, thereby enhancing farmers’ accessibility to green technologies and other machinery. Similarly, ASSs can enhance farming efficiency by the professional division of labor. The approach effectively tackles the challenges posed by the small, scattered, and fragmented nature of farmland plots [18]. ASSs focus on machine farming, machine sowing, machine harvesting, and plant protection, realizing labor substitution while integrating specialized technical expertise into agricultural production [22], thus catalyzing the sustainable transition of agriculture systems.

By systematically dismantling these barriers, the ASS subsystem reduces the perceived risk for farmers, thereby creating a more favorable state for the entire farm system to transition towards green production. This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1.

The integration of agricultural socialized services (ASSs) contributes to the adoption of green production behaviors by farmers.

2.2. The Mechanization Pathway: Coupling ASSs and Green Behavior Subsystems

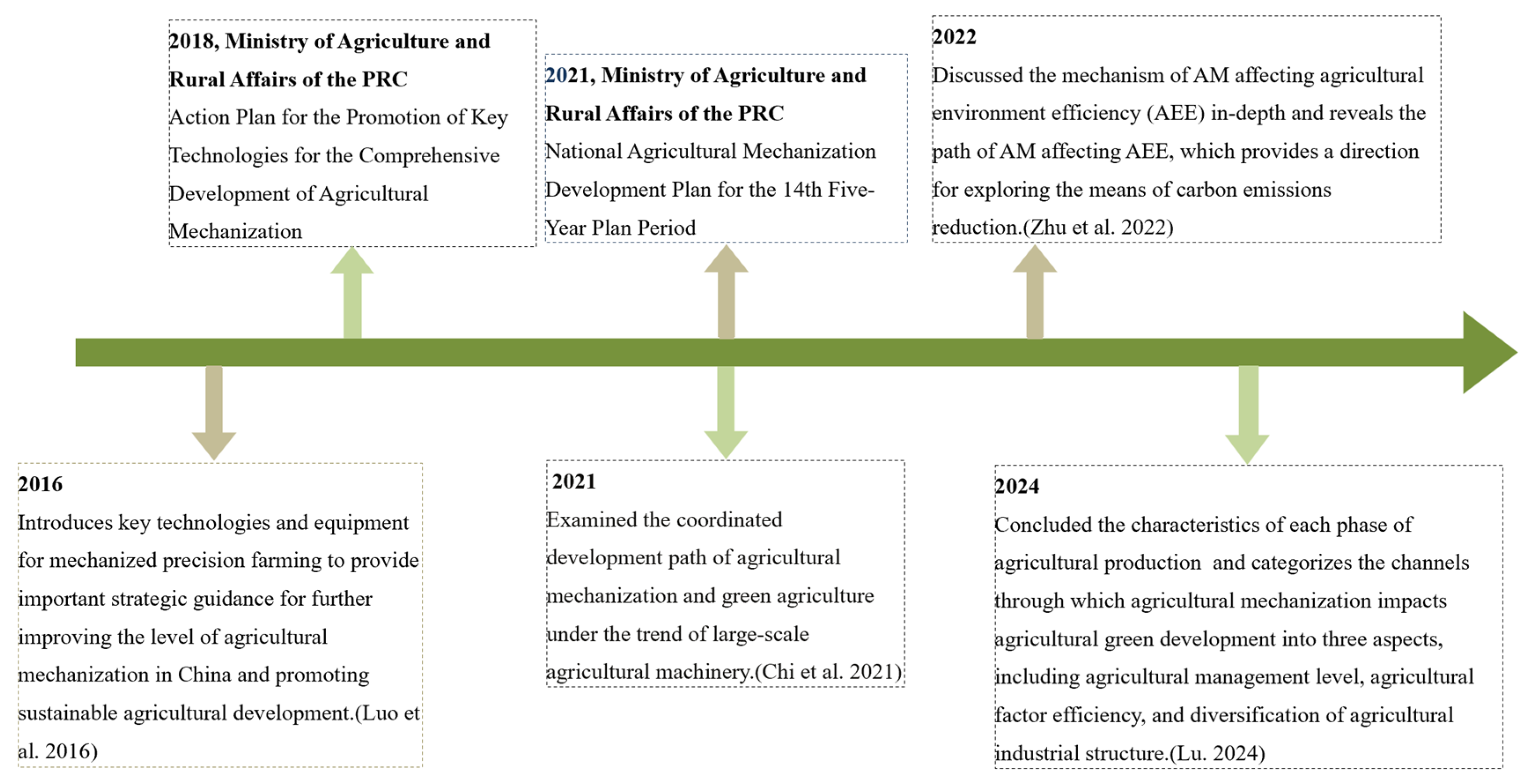

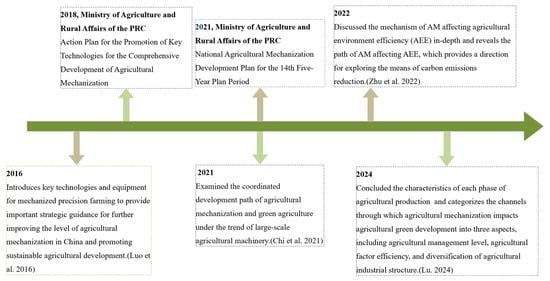

Agricultural mechanization is not merely an advanced production tool, but a crucial social technological subsystem. The level of agricultural mechanization plays an important role in ensuring resource efficiency and national food security [22]. With the increasing adoption of agricultural machinery, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA) has begun steering a green transition in this sector through top–down guidance. Academic research on agricultural mechanization continues to deepen—evolving from studying specific technical improvements to mitigate environmental harm [23], to analyzing how mechanization influences agricultural environment efficiency [24,25], and further exploring pathways through which agricultural mechanization drives sustainable green development in agriculture [11]. Agricultural mechanization has become increasingly important in the green transformation of agriculture, which can also exert an influence on farmers’ production practices (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Progression of sustainable agricultural machinery in China [11,23,24,25].

On one hand, ASSs act as a driver for the upgrading of the mechanization subsystem. The adoption level of agricultural socialized services shows an improvement in service levels from 2008 to 2019. Among individual services, agricultural mechanization and financial insurance services exhibited the most significant enhancement in adoption rates [20]. As the continuous improvement of agricultural socialized service markets, purchasing outsourced machinery services and improving agricultural mechanization levels can reduce investment risks in agricultural production [26]. Therefore, the introduction of ASSs is expected to significantly accelerate the improvement of the mechanization level.

On the other hand, a higher level of mechanization is a direct factor in achieving green production practices. Farmers’ adoption of mechanized irrigation, fertilization, and pesticide application technologies enables precise control over water, fertilizer, and agrochemical inputs while maintaining operational effectiveness [27]. This approach enhances the utilization rate of production materials, minimizes resource wastage, effectively mitigates ecological pollution, and prevents environmental degradation from chemical overdosing, thereby fostering sustainable agricultural production. Furthermore, the implementation of agricultural machinery for land preparation, planting, and harvesting operations demonstrates significant labor substitution effects, enhancing both the quality and resilience of agricultural production [11]. This causal pathway thereby significantly elevates the propensity of farm households to adopt green production behaviors.

Therefore, agricultural mechanization plays a crucial mediating role in the system. The systematic intervention of ASSs will enhance the operation of the mechanization subsystem, thereby facilitating the behaviors expected in the green production model. This leads to our second hypothesis:

H2.

The level of agricultural mechanization functions as a key mediating pathway through which the ASS subsystem influences the adoption of green production behaviors.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

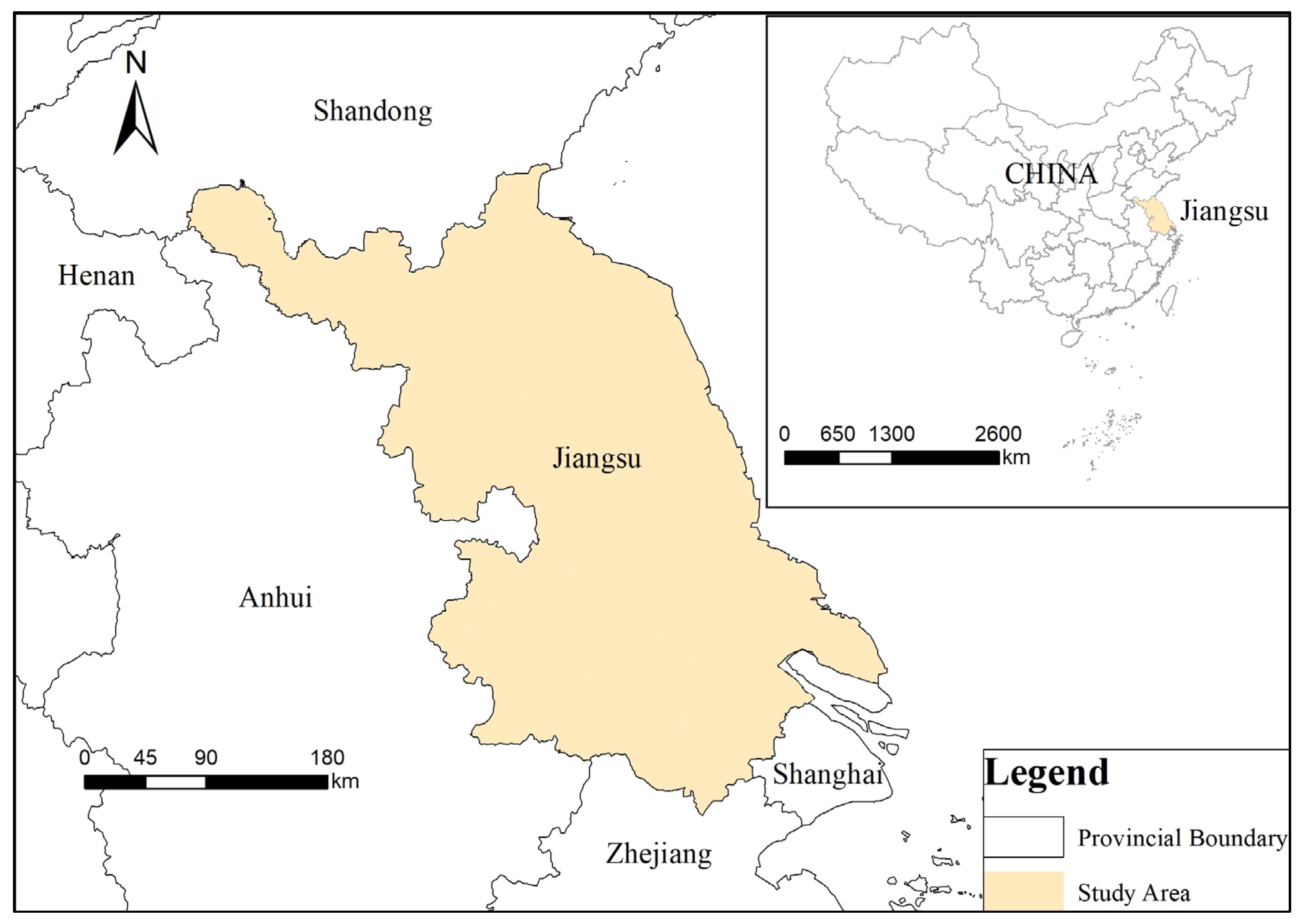

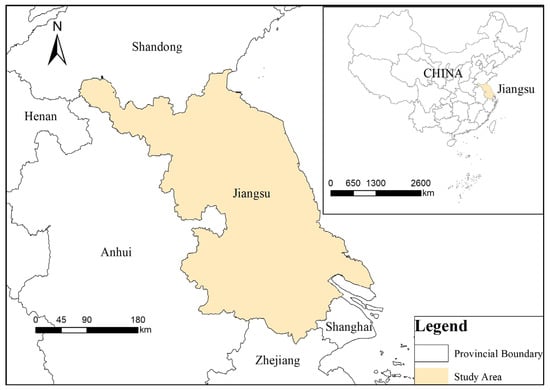

This study uses the data of China Land Economic Survey (CLES). It was conducted by the Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Nanjing Agricultural University in Jiangsu Province in 2020–2022. It includes questionnaires covering green development, factor markets, agricultural production, finance, and insurance and has variables that are relevant to this study, including agricultural socialized services, agricultural green production, agricultural mechanization, family characteristics, individual characteristics, and village characteristics. To improve the representativeness of the samples, the survey adopts the probability proportionate to size sampling (PPS) method. The survey covered 26 districts (two districts/counties per city), 52 townships (two townships per district/county), and 2600 households (one village per township with 50 randomly selected rural households per village), ensuring geographic representativeness across Jiangsu Province. Jiangsu Province, situated along China’s eastern coastal plain, boasts fertile flatlands, abundant rainfall, and optimal agricultural conditions, making it Southern China’s largest rice-producing region. Therefore, it is well represented as the study area (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Study area.

It is worth emphasizing that although CLES is a nationwide survey project, the most recent publicly available data only covers samples from Jiangsu Province. Although this choice is limited by data availability, from a research perspective, choosing Jiangsu Province as the research object holds significant practical importance. Jiangsu Province is a pioneer in agricultural modernization in China, with its rates of agricultural socialization services and their maturity ranking among the top in the country. Therefore, Jiangsu Province can be regarded as a key case study, and studying the impact of a developed service system can provide forward-looking insights for the future development paths of other regions.

In this study, the sample data from the three years of 2020, 2021, and 2022 is integrated into mixed cross-section data. After data processing, samples with missing key information were removed, and 1839 valid samples were finally retained.

3.2. Variables

The CLES database contains the data needed for this study and is representative, and the basis of data selection is explained in the light of the practical significance of each variable. This study mainly includes the main variables of agricultural socialized services, green production behavior of farmers, agricultural mechanization, etc. Most variables are used with their original scale. However, to address issues of skewness and to facilitate a semi-elasticity interpretation, variables with a wide range and non-normal distribution, namely Household Assets, Agricultural Machinery Purchase Subsidies, and Credit Availability, were transformed using the natural logarithm. This transformation is noted in all relevant tables. Each variable is described in the following paragraphs.

Dependent variables. The dependent variable in this study is the green production behavior of farmers, which is measured by the environmental protection behavior of farmers in the production process. The four behaviors of “whether to apply organic fertilizers and formulated fertilizers; whether to use high-efficiency, low-toxicity and low-residue pesticides; whether to recycle agricultural films; and whether to recycle pesticide packaging are selected to specifically characterize the green production behaviors of farmers. Because these behaviors belong to production chains, which cover the most important parts in the process of agricultural production, they also have the greatest impact on the environment. If a farmer adopts one or more green production practices, it is coded as “1”; otherwise, it is coded as “0”.

Independent variables. The independent variable of this study is agricultural socialized services, which is characterized by whether farmers purchase socialized services or not. We measure this based on farmer engagement across six production stages of “ploughing, seedling raising, planting, pesticide spraying, harvesting, and straw returning to the field”. A primary objective of this study is to capture the impact of deep and systematic adoption of ASSs, as relevant theories and policy orientations all emphasize the synergistic effect of covering the services in the entire value chain. Additionally, descriptive statistics show that the service penetration rate of the sample in this study is extremely high (86.1% of the farmers have purchased at least one service). To effectively distinguish between farmers who have a strong commitment to the adoption of services and those with only superficial participation, we followed the approach of Sun et al. [28] and defined the core explanatory variable as a binary dummy variable: if farmers have purchased outsourced services in three or more stages, the value for whether farmers have purchased socialized agricultural services is assigned as “1”; otherwise, it is assigned as “0”. The above measurement is used to better reflect the impact of ASSs across the entire industrial chain on farmers’ production behavior.

Mediating variables. Mediating variable is agricultural mechanization. This study measures a household’s agricultural mechanization level by the quantity of productive assets held, including tractors, seeders, and harvesters. The variable adopts non-negative integer values (≥0), where zero indicates no adoption of productive assets.

Control variables. Due to limited availability of data, referring to previous studies [29,30], this study controls for family characteristics, individual characteristics, and village characteristics. Firstly, in terms of family characteristics, this study chooses five variables: whether or not the head of household is a party member, household assets, the number of elderly people in the household, land tenure security, and household credit availability. Secondly, in terms of individual characteristics, this study chooses five variables: gender of the head of household, age of the head of household, education level of the head of household, health status of the head of household, and whether or not the head of household receives agricultural technology training. Time preference refers to the intertemporal choice preferences in farmers’ decision-making processes. This factor is also controlled for in the empirical model. Thirdly, the study takes village characteristics into consideration, as the different subsidies a village receives from the government and the different administrative locations of a village may affect the farmers’ agriculture production behaviors. In addition to the control variables at the individual, family, and village levels mentioned above, in order to reduce time trend interference, the “year” variable is also included as a control variable.

Definition and descriptive statistics for each variable are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and descriptive analysis.

3.3. Models

3.3.1. Probit Model and Logit Model

Considering that the explained variables in this study are whether the farmers adopt green production behaviors, with values of 0 and 1, which are binary variables, the binary probit and binary logit models are used to estimate the impact of digital literacy on farmers’ green production. The models are set as follows: Formula (1) is probit model and Formulas (2) and (3) are logit models:

In Formula (1), is the explained variable of whether the farmer has adopted green production practices, is the key explanatory variable of whether the farmer has purchased agricultural socialized services, and is a series of control variables, including individual characteristics, family characteristics, and village characteristics. is the standard normal distribution function, and are the coefficients to be estimated. To obtain the odds ratio, Formula (2) is logit transformed to Formula (3). According to Formula (3), if changes one unit, the odds ratio changes to , while other variables remain constant.

In Formula (2), represents farmers willing to adopt the green production practice and represents those who are not willing. presents the probability of farmers willing to adopt the green production practice, and is a series of factors affecting farmers’ willingness. Furthermore, this study reports the marginal effect of each explanatory variable regarding the impact of farmers’ green production behaviors.

3.3.2. Propensity Score Matching Model

Potential endogeneity may exist within the model. Firstly, the purchase of ASSs by farmers constitutes a “self-selection” behavior. This behavior is influenced by variables such as head of household and family characteristics rather than occurring randomly. This potentially leads to sample selection bias and the consequent endogeneity problem, resulting in biased estimation outcomes in the regression model. To address the problem, this study uses propensity score matching (PSM) to correct for potential sample selection bias. The propensity score matching model firstly divides the sample into treatment and control groups to test the factors influencing farmers’ decision to purchase agricultural socialized services, then estimates the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) after matching, thereby ensuring the robustness of the empirical findings. According to Becker et al. [31], the average effect of treatment on the treated (ATT) can be calculated as follows:

In Formula (4), presents the green production behaviors of farmers who purchased ASSs, and presents the green production behaviors of farmers who had not purchased ASSs.

3.3.3. Generalized Structural Equation Model

Next, this study uses generalized structural equation model (GSEM) to test the robustness of the mediation effect results, providing a robust method that does not rely on the assumption of normal distribution to test the significance of the mediation effect. This study establishes the following test model with reference to the mediation effect test of Zhonglin Wen and Baojuan Ye [32]:

In Formulas (5)–(7), represents the green production behavior of farmers ; represents the agricultural socialized services; represents the mediating variable of farmers’ level of mechanization in the agricultural production process; represents control variables; represent the coefficients of control variables; and are random disturbance terms. Formula (5) represents the effect of agricultural socialized services on farmers’ green production behaviors. Formula (6) represents the effect of agricultural socialized services on the mediating variable, and the coefficient is the effect of agricultural socialized services on the mediating variable. When the coefficient of the independent variable is significantly positive, it means that agricultural socialized services improve the mechanized operation of farmers. Formula (7) represents the joint effect of independent variables and mediating variables on farmers’ green production behaviors. The coefficient is the direct effect of agricultural socialized services on farmers’ green production behaviors.

The meaning of the coefficient is the mediating effect, and the test process is as follows: the first step is to test the total effect of socialized agricultural services on farmers’ green production; the second step is to prove that the effect of agricultural socialized services on the mediating variable is significant; and the third step is to judge whether the mediating effect exists or not. If in model (7) is significant, it proves that agricultural socialized services will indirectly affect farmers’ green production behavior through the mediating variable.

4. Results

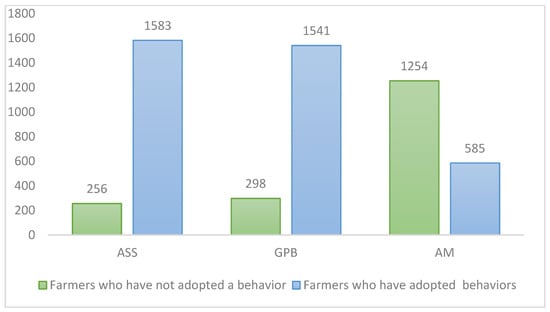

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

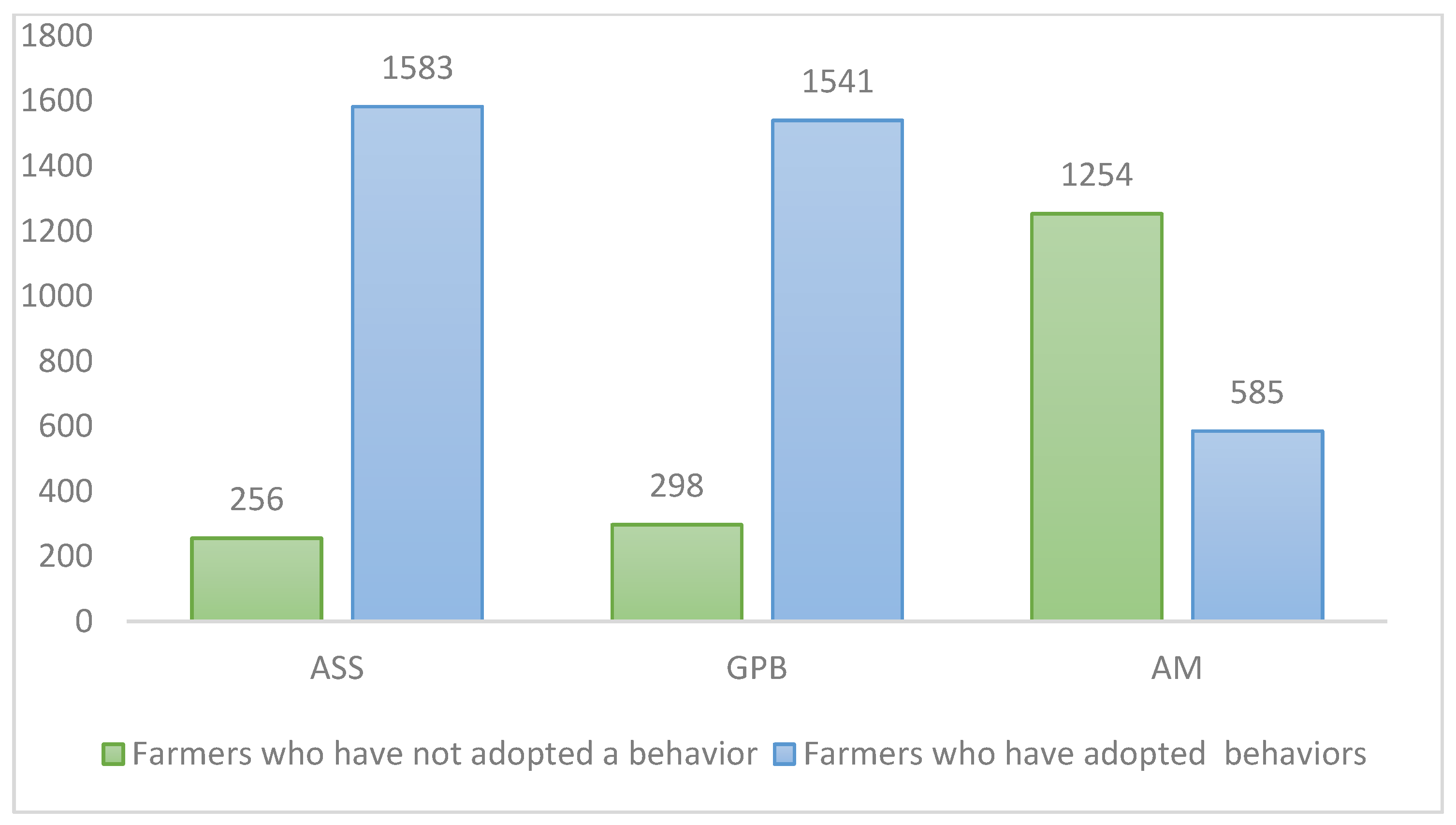

As shown earlier in Table 1, the average age of the head of the household (61.45 years) suggests a demographic of aging farmers. The average village-level farm machinery subsidy is 1311.91 RMB, and the likelihood of technical training participation is 36.38%. These distributions reveal opportunities to enhance mechanization efficiency and specialization in the sample areas. Figure 4 details several of the key features of 1839 sample farm households in the database. The fact that 1583 households purchased at least one agricultural socialized services (ASSs) indicates high ASS penetration in the surveyed regions. The proportion of farmers adopting green production practices reached 83.8%, confirming the strong representativeness of the sample. The presence of 585 households owning more than one agricultural machine reflects extensive mechanization. This study aims to conduct comparative analyses of these interlinked factors, identifying actionable pathways for advancing the agricultural green transition and modernization.

Figure 4.

Statistical characteristics for main variables.

4.2. Baseline Regression

As shown in Table 2, Column (1) and (3) present the results of the probit model and logit model. The coefficients of the impact of agricultural socialized services on farmers’ green production behavior in the two models are both positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that agricultural socialized services have a positive impact on farmers’ green behavior, and farmers purchasing more ASSs exhibit stronger adoption tendencies. Column (2) presents the marginal effect estimates in the probit model, indicating that the probability of implementing green production behaviors increases by 6.7% for farmers who adopt agricultural socialized services compared to farmers who do not adopt agricultural socialized services. The result of the marginal effect test in the logit model is consistent with the results obtained from the probit model.

Table 2.

Results of baseline regression.

The other controls show statistically significant but heterogeneous effects on farmers’ green production behavior. In terms of family characteristics, the coefficient of the number of elderly household members is significant at the 5% level. The number of elderly family members and the age of the head of the household have a negative effect on the green production behavior of farmers, which may be explained by the fact that the lower awareness of green production among elderly family members will negatively influence factor input decisions. And if the head of the household is a party member, the farm household is more inclined to purchase agricultural socialized services. Because party members may face environmental performance assessments, as well as receive priority policy support, they are more likely to adopt green production practices. Statistical data shows that the more subsidies a village receives for purchasing agricultural machinery, the more likely farmers are to engage in green agricultural production. Improving the level of agricultural mechanization in the entire village indirectly promotes green agricultural production. Time preference has a positive effect on the green production behavior of farmers, perhaps because the more value farmers place on future returns, the more environmentally friendly they will be in their agricultural production in order to conserve land fertility and reduce environmental pollution. The survey year variable is significant at the 1% level, reflecting that green production behavior is driven by time trends. After controlling for the time variable, the results are more reliable.

Next, to ensure the stability of our findings, the measurement method for the independent variable has been changed. In the six production stages of “ploughing, seedling raising, planting, pesticide spraying, harvesting, and straw returning to the field”, any purchase of an ASS in the six stages is assigned a value of “1”, while no purchase is assigned a value of “0”. The purchase status for all stages is added up, and the values range from “0” to “6”. The results can be seen in Table 3. Agricultural socialized services positively affect farmers’ green production behavior, and the statistical value is significant at the 1% level. It is consistent with the basic probit regression results, which to some extent reflect the robustness of the results and confirm the role of agricultural socialized services in promoting the green production behavior of farmers.

Table 3.

The results of alternative measure tests.

4.3. Robustness Analysis with PSM

Considering the self-selection bias, the study further constructs a counterfactual analysis framework to test the robustness on the regression results. Specifically, the K-nearest neighbor matching, kernel matching, caliper matching, and radius caliper matching methods are implemented to establish treatment and control groups. Subsequently, logit regressions and balance tests are performed.

The test results (Table 4) for all four matching methods are statistically significant and consistent at the 1% significance level. According to K-nearest neighbor matching, the ATT estimate is 0.071, indicating that if a farmer had not purchased ASSs, the adoption rate of green production practices was 0.929. By purchasing ASSs, however, this adoption rate increased to 1. This demonstrates that ASSs exert a significantly positive influence on farmers’ adoption of green production behaviors. The net treatment effect estimated based on the four matching methods shows very little variation between the different estimation methods, and the direction and magnitude of the effect are essentially the same, thus providing strong evidence for the matching results.

Table 4.

Estimating the ATT using different matching methods.

Table 4.

Estimating the ATT using different matching methods.

| Matching Methods | Treated | Controlled | ATT | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-nearest neighbor matching (1:4) | 1 | 0.929 | 0.071 *** | 0.021 | 3.42 |

| Kernel matching | 1 | 0.938 | 0.062 *** | 0.019 | 3.26 |

| Caliper matching | 1 | 0.928 | 0.072 *** | 0.026 | 2.77 |

| Radius caliper matching | 1 | 0.941 | 0.059 *** | 0.020 | 3.01 |

Note: *** p < 0.01 As shown in Table 5, the biases for covariates fell below 10%, while p-values from paired-sample t-tests exceeded 0.1, revealing that the covariates of the two matched groups are well balanced in contrast to the unmatched samples, thus satisfying the balance criteria.

Table 5.

Balancing test of matched samples.

Table 5.

Balancing test of matched samples.

| Mean | t-Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | U/M | Treated | Control | Bias (%) | Reduce Bias (%) | t | p > t |

| HE | Unmatched | 1.204 | 1.213 | −1.0 | −0.21 | 0.836 | |

| Matched | 1.204 | 1.194 | 1.3 | −36.0 | 0.30 | 0.762 | |

| HPM | Unmatched | 0.240 | 0.261 | −4.7 | −1.01 | 0.313 | |

| Matched | 0.241 | 0.239 | 3.9 | 17.5 | 0.93 | 0.355 | |

| HA | Unmatched | 9.126 | 8.987 | 4.6 | 0.99 | 0.321 | |

| Matched | 9.127 | 9.156 | 0.6 | 87.4 | 0.14 | 0.889 | |

| HHG | Unmatched | 0.692 | 0.739 | −10.5 | −2.21 | 0.027 | |

| Matched | 0.692 | 0.705 | −0.7 | 93.0 | −0.16 | 0.869 | |

| HHA | Unmatched | 61.433 | 61.482 | −0.5 | −0.10 | 0.918 | |

| Matched | 61.426 | 61.165 | 2.4 | −386.6 | 0.55 | 0.584 | |

| HEL | Unmatched | 6.434 | 6.775 | −8.7 | −1.85 | 0.065 | |

| Matched | 6.441 | 6.549 | −1.4 | 84.1 | −0.32 | 0.746 | |

| HHS | Unmatched | 3.857 | 4.050 | −18.6 | −3.94 | 0.000 | |

| Matched | 3.859 | 3.850 | 2.6 | 86.2 | −0.56 | 0.574 | |

| ATT | Unmatched | 0.352 | 0.380 | −6.0 | −1.27 | 0.203 | |

| Matched | 0.351 | 0.356 | 0.2 | 95.9 | 0.06 | 0.955 | |

| TP | Unmatched | 1.665 | 1.670 | −0.6 | −0.13 | 0.899 | |

| Matched | 1.666 | 1.670 | 0.2 | −254.7 | −0.49 | 0.622 | |

| AMPS | Unmatched | 1.193 | 1.367 | −8.9 | −1.88 | 0.060 | |

| Matched | 1.194 | 1.224 | 0.7 | 92.2 | 0.17 | 0.869 | |

| DCC | Unmatched | 17.193 | 20.061 | −19.6 | −4.16 | 0.000 | |

| Matched | 17.204 | 17.990 | −4.4 | 77.7 | −1.07 | 0.284 | |

| LTS | Unmatched | 0.922 | 0.920 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 0.908 | |

| Matched | 0.922 | 0.919 | −2.5 | −367.4 | −0.60 | 0.550 | |

| CA | Unmatched | 2.252 | 2.373 | −0.5 | −0.10 | 0.919 | |

| Matched | 2.254 | 2.346 | −1.0 | −106.0 | −0.23 | 0.819 | |

| Year | Unmatched | 2020.6 | 2020.8 | −35.9 | −7.65 | 0.000 | |

| Matched | 2020.6 | 2020.6 | 0.9 | 97.5 | 0.21 | 0.833 | |

4.4. Mediation Effect Analysis

To delve deeper into the causal mechanism, a generalized structural equation model (GSEM) is used for testing the AM mediating effects of ASSs on green production (Table 6). The results reveal interesting causal pathways, including the following:

Table 6.

Results of mediation effect analysis.

(1) Path 1 (ASSs → AM): The coefficient of ASSs on AM is negative and statistically significant (−0.755, p < 0.01). This indicates that farmers who purchase socialized services tend to reduce their personal machinery holdings. This is logical because auxiliary services provide another service-based access route for mechanization, thereby reducing the demand for high-capital investment in fixed assets;

(2) Path 2 (AM → GPB): The coefficient of AM on green production is positive (0.009, p < 0.05), indicating that machinery ownership itself is correlated with greener practices;

(3) Path 3 (ASSs → GPB): The direct effect of ASSs on GPB remains positive and highly significant (0.287, p < 0.01).

Therefore, the overall moderating effect (the product of path 1 and path 2) is negative. This is a typical example of “inconsistent moderation”. This means that ASSs promote green production, although they reduce farmers’ reliance on their own machinery. Agricultural machinery and equipment represent a significant fixed cost investment for farmers. Purchasing socialized services essentially converts fixed equipment costs into variable service costs that are paid on demand. For farmers with limited scale, when the market price of socialized services is lower than the average annual cost of purchasing their own equipment, purchasing services is more economical. After purchasing services, farmers proactively sell low-usage, high-maintenance-cost, large agricultural machinery but retain small, practical equipment for daily light-duty operations. As regional agricultural machinery cooperatives and specialized service companies become more widespread, service prices decrease due to competition, and service quality standards improve, further reducing the necessity of purchasing equipment outright. The total effect of ASSs is composed of a strong, positive direct effect and a weaker, negative indirect effect. This indicates that the main contribution of ASSs is not merely more machines, but rather they provide higher-quality, technologically advanced and precise mechanical services, redirecting the development path of green mechanization from “ownership” to “access to services”.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

The previous study selected a probit regression model for discrete variables to measure the impact effect of agricultural socialized services on the green production behaviors of farmers and concluded that agricultural socialized services can increase farmers’ adoption of green production behavior, thus significantly promoting green production in agriculture. However, previous results only reflect the average effect of the whole sample. The group heterogeneity of the impact of agricultural socialized services on farmers’ green production behavior needs further analysis. Next, this study groups the sampled farmers in terms of operating scales. There are significant differences between small-scale farmers and large-scale operators in terms of production capacity, production objectives, and business needs. And small-scale farmers’ requirements for agricultural socialized services are easily neglected due to small land size, low demand for services, and high transaction costs for obtaining services. This study defines farmers whose operating scales are less than or equal to 4.8 mu as small-scale farmers and more than 4.8 mu as large-scale farmers, based on the median of the operation scale. This reflects the local distribution of resources, making the conclusions more regionally adaptive. The sample includes 925 small-scale farmers and 914 large-scale farmers. Table 7 reports the differences in the impact of ASSs on farmers’ green production across different operation scales. Using three matching methods, we obtained the green production possibilities for the treated and controlled groups of small-scale and large-scale farmers, as well as the ATT values derived from their differences. As can be seen, the results obtained using each matching method are very similar. The ATT values for small-scale farmers all passed the significance test at the 1% level. However, the ATT values for large-scale farmers did not pass the significance test.

Table 7.

The effect of ASSs on promoting green production among farmers at different scales.

The results indicate that the agricultural socialized services promote an increase in green production behavior, which is consistent with the results of the previous section, and once again verifies the stability of the main effect. However, the effect of agricultural socialized services on the green production behavior of the large-scale farmers is unsignificant, indicating that small-scale farmers are more inclined to purchase ASSs for the green transition.

Small-scale farmers often operate under constrained agricultural conditions, with limited non-farm employment opportunities due to age or health barriers. However, the adoption of agricultural socialized services introducing green production factors into agricultural production can compensate for the resource constraints and capacity limitations of small-scale farmers. In contrast, large-scale farmers have stronger resource endowments and high rates for the use of green production factors, and the driving effect of agricultural socialized services is relatively insignificant.

5. Discussion

Our empirical research indicates that agricultural socialized services (ASSs) are not merely auxiliary inputs, but rather a powerful force that can guide farmers towards green production. To more sustainably promote farmland conservation, it becomes increasingly necessary to implement economic incentives for farmers adopting green production behaviors.

5.1. ASSs as a Systemic Enabler

The results of this study show that agricultural socialized services significantly enhance green production practices among farm households, while effectively steering them toward adopting environmentally friendly production methods.

In agricultural socialized services research, there may be systematic differences between farmers who purchase services and those who do not, leading to biased direct regression results. Previous studies [33,34] have used logit, probit, and CMP models to examine the impact of ASSs on farmers’ production behavior, but they have been unable to address the issue of sample selection bias. This study adopts the PSM approach to construct a “counterfactual control group”, which matches each treatment group farmer with a non-purchasing farmer with similar background characteristics based on propensity scores to simulate a randomized trial. The PSM not only eliminates bias from observable confounding factors through counter-factual matching, but also directly provides the average treatment effect (ATT) to quantify the policy effect. Therefore, this study obtains more reliable causal effects. The results are consistent with previous studies using different approaches [12,18].

Agricultural socialized services provide specialized services for agricultural production, acting as carriers of human capital and knowledge transfer, helping farmers access information and new cultivation techniques. They are playing an increasingly significant role in modern agricultural production. In terms of green production transformation, ASSs enhance the expected returns on agricultural inputs, leading farm households to adopt green production practices. Owing to their large-scale operations, ASS organizations wield greater bargaining power in input markets. Thus, when farmers participate in ASSs, they gain access to more affordable green production factors, effectively reducing operational costs. Concurrently, consumer preference for green agricultural products elevates market prices. The convergence of low production costs and high market returns increases farmers’ propensity to purchase ASSs and transition toward sustainable production methods. Moreover, ASSs introduce green production inputs to farmers. They enable access to important inputs that are often unavailable in conventional markets, such as formula fertilizer via soil testing, organic fertilizers, and precision irrigation equipment; thus, ASSs could significantly ease adoption barriers. Additionally, through the integration of specialized expertise and advanced technologies, ASS organizations embed green agricultural principles into production processes. Farmers are more aware of green production and more inclined to adopt green production practices.

This paper adopts a different measurement approach for ASSs compared to previous studies [18,34]. The penetration rate of agricultural socialized services in the sample area is relatively high. This study assigns a value of “1” to farmers who purchase agricultural socialized services in three or more production stages, indicating that these farmers are deeply engaged in the agricultural socialized service system. This highlights the synergistic role of agricultural socialized services across multiple production stages. Agricultural socialized service organizations, supported by policy, are better positioned to expand into new markets. Under the guidance of economies of scale, they provide farmers with multi-stage, large-scale agricultural production services. Within a well-developed ASS framework, farmers deeply engaged in the system are more likely to adopt environmentally friendly production methods, thereby promoting the region’s agricultural green transition. However, this may limit the applicability of the study’s conclusions to regions with a high level of agricultural modernization.

5.2. The Decoupling Role of Mechanization Services

A further mediation analysis substantiates that ASSs have an impact through mechanization advancement. Although some scholars hold that agricultural machinery is deficient in energy conservation and emission reduction and that agricultural mechanization will hurt the environment [35], our study along with studies by other scholars [15] found that mechanization advancement can promote a green production transition for farmers to reduce environmental pollution.

The fixed costs in holding agricultural machinery are high, and it is difficult to convert machinery to be suitable for other uses or lease it to recover costs. This asset specificity is the key barrier to smallholder farmers’ adoption of green production technologies. At this time, agricultural socialized service organizations that provide machinery leasing, through the sharing of assets and fixed costs, can reduce the risk of agricultural machinery use, consequently elevating the level of agricultural mechanization. Agricultural mechanization changes the previous crude agricultural production methods of high input and low output. The new method is always characterized with a higher energy efficiency and operational efficiency and thus can reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, benefitting the environment. In this case, socialized machinery services can increase the green production capacity of households and drive smallholder farmers onto a green development path [4]. Chinese governors support the development of agricultural socialized services (ASSs) to consolidate large-scale mechanized operations, thereby enhancing agricultural production efficiency. By integrating advanced technologies to implement standardized production protocols, ASSs can simultaneously elevate crop quality and yields. Evidence confirms that ASSs have emerged as a potent institutional mechanism for promoting sustainable development in agriculture.

5.3. ASSs Disproportionately Empower Smallholder Farmers

The empirical evidence also reveals significant heterogeneity. This may be because resource endowments vary greatly among farmers. Compared with large-scale farmers, it is relatively easier for small-scale farmers to adopt green production behaviors through the purchase of ASSs. This finding is different from previous studies [36], in which scholars concluded that in Xinjiang Province, larger-scale farmers have more resources and a greater capacity to adopt new technologies and services [37]. However, in this study, the conclusion is the opposite. The reasons are listed as follows. Small-scale farmers have limited access to information and do not have sufficient knowledge of or concerns about new technologies. ASS organizations, with their professional talents and information networks, can effectively bridge the knowledge gap by providing professional guidance and technical training and reducing the learning costs and application concerns of small farmers. The decentralized operation of small farmers leads to low efficiency, and the high cost of single-family operations makes it difficult for them to obtain large-scale agricultural equipment. ASS organizations integrate dispersed demand and scaled-up batch operation, which can significantly reduce the cost of services for a single mu and the threshold of using professional equipment, so that small farmers can also enjoy advanced and efficient green production services, especially in regions where the agricultural socialized service market is relatively mature.

Agricultural socialized services can implement centralized purchasing, uniform packaging, and brand endorsement for decentralized small farmers, as well as provide green certification consulting and order matching services, which can significantly reduce the green input costs of small farmers. This greatly reduces the high transaction costs for small farmers to connect to green agricultural markets. Farmers with a large operating scale usually have greater capital and management ability, wider information channels, and professional machinery. Some of them have already achieved a high degree of mechanization, standardization, and integrated operations. Therefore, their dependence on basic and general socialized services is relatively low, and they are more likely to selectively purchase some high-precision or special services according to their own needs. Their green transition is more about endogenous decision making and internal capacity building, and ASSs are less of a driver for their green transition.

The contributions of this study are threefold: Firstly, this study analyzes the direct impact of ASSs in the whole production chain on agricultural green production, which can further clarify the influencing factors of households’ green production, and examines the effectiveness of the construction of a whole-process ASS market system. Secondly, by examining the mediating role of agricultural mechanization, our understanding of the internal mechanism by which ASSs drive farmers’ green production behaviors has been deepened. Additionally, through a heterogeneity analysis, this study provides recommendations for guiding differentiated transformation guidance strategies for farmers with varying resource endowments. The observed heterogeneity indicates that the impact of ASSs on green practices varies depending on the level of agricultural development in different regions.

6. Conclusions

Based on data from the China Land Economy Survey (CLES), this study employs a methodological framework to investigate how agricultural socialized services drive farmers’ adoption of green production practices and the mediation role of agricultural mechanization among them. The results reveal that ASSs significantly stimulate farmers’ green production adoption, which is consistent with other findings [18,33], especially in regions such as Jiangsu Province with higher levels of agricultural modernization. The mediation analysis results show that agricultural mechanization serves as a critical mediating channel for the agricultural transition, indicating that ASSs provide higher-quality, technologically advanced, and precise mechanical services to drive green transformation in agriculture. Furthermore, agricultural socialized services demonstrate more substantial promotion effects on green production adoption among small-scale farmers compared to large-scale farmers.

Building upon the empirical findings, this study yields following policy implications. On one hand, governors should prioritize institutional support (targeted subsidies, tax incentives, and project prioritization) to bolster agricultural socialized service organizations. Empirical studies have substantiated the catalytic role of these services in promoting farmers’ adoption of green production practices. By integrating technical guidance, production input supply, and market linkage services, the socialized service system effectively replaces fragmented on-farm investments, thereby enhancing production efficiency and product quality. On the other hand, governors should intensify the promotion of ASSs by establishing demonstration plots and peer-learning networks to mitigate farmers’ risk perceptions. Moreover, tailored technical solutions may be developed to address scale-specific constraints faced by smallholder farmers, thereby overcoming size-related barriers to ASSs.

Finally, we must acknowledge the limitations regarding the external validity of our findings. This study is geographically focused on Jiangsu Province. Given China’s vast territory and significant regional differences, focusing solely on Jiangsu Province in the eastern plains region, where the penetration rate of agricultural socialized services is high, the conclusions apply only to regions with a high level of agricultural modernization. This study cannot comprehensively explore the heterogeneous effects of ASSs on farmers’ green production behavior under different levels of agricultural development. In the relatively underdeveloped central and western regions, mountainous areas, or major grain-producing areas, the effects of ASSs may vary significantly. Therefore, the findings of this study should be understood as insights from a leading region, rather than representing the national average level. Chinese farmers’ production decisions are mainly based on the plot as a decision unit, and their green production behavior may be inconsistent across plots [38], but our study lacks the relevant data to study farmers’ plot-based decision-making behavior. Therefore, we will carry out further research with the data on different types of agricultural production areas to comprehensively analyze the green production promotion effects of agricultural socialized services across the country. Moreover, future studies can also be carried out at the plot level to validate our interpretation of these results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S. and X.W.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.; Funding acquisition, X.W., Y.Z., G.L. and Z.X.; Methodology, X.S. and X.W.; Project administration, G.L. and Z.X.; Software, X.S. and X.W.; Supervision, G.L. and Z.X.; Validation, X.W. and Y.Z.; Writing—original draft, X.S.; Writing—review and editing, X.W. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22NDJC068YB), the Ningbo City Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Base Project (Grant No. JD6-279), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LQ22G030001), the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation Project (Grant No. 2023J097), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC No 42171254).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, F.; Ren, J.; Wimmer, S.; Yin, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, C. Incentive Mechanism for Promoting Farmers to Plant Green Manure in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, G. Effect of Farmland Scale on Agricultural Green Production Technology Adoption: Evidence from Rice Farmers in Jiangsu Province, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 147, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Chen, C.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, K. Peer Effects, Attention Allocation and Farmers’ Adoption of Cleaner Production Technology: Taking Green Control Techniques as an Example. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Zhou, W.; Song, J.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Impact of Outsourced Machinery Services on Farmers’ Green Production Behavior: Evidence from Chinese Rice Farmers. J. Environ. Manage 2023, 327, 116843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, G.; Zhao, X. An Evaluation of China’s Agricultural Green Production: 1978–2017. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Yao, X. Toward Cleaner Production: What Drives Farmers to Adopt Eco-Friendly Agricultural Production? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrennikov, D.; Thorne, F.; Kallas, Z.; McCarthy, S.N. Factors Influencing Adoption of Sustainable Farming Practices in Europe: A Systemic Review of Empirical Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z. Effects of Risk Perception and Agricultural Socialized Services on Farmers’ Organic Fertilizer Application Behavior: Evidence from Shandong Province, China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1056678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, T.; Khan, S.U. How Does Capital Endowment Impact Farmers’ Green Production Behavior? Perspectives on Ecological Cognition and Environmental Regulation. Land 2023, 12, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Feng, C.; Qin, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Measuring China’s Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity and Its Drivers during 1998–2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F. How Does Improving Agricultural Mechanization Affect the Green Development of Agriculture? Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 472, 143298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, M.; Tan, Y.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Y. Can Agricultural Productive Services Promote Agricultural Environmental Efficiency in China? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Han, H.; Song, Y. Research on the Impact of Agricultural Socialization Services on the Ecological Efficiency of Agricultural Land Use. Land 2024, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, T. Can Agricultural Socialized Services Promote the Reduction in Chemical Fertilizer? Analysis Based on the Moderating Effect of Farm Size. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, W. The Role of Agricultural Green Production Technologies in Improving Low-Carbon Efficiency in China: Necessary but Not Effective. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qiao, Y.; Yao, R. What Promote Farmers to Adopt Green Agricultural Fertilizers? Evidence from 8 Provinces in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epule, E.T.; Bryant, C.R.; Akkari, C.; Daouda, O. Can Organic Fertilizers Set the Pace for a Greener Arable Agricultural Revolution in Africa? Analysis, Synthesis and Way Forward. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, M.; Li, Y.; Chi, L.; Zhan, S. The Effects of Agricultural Socialized Services on Sustainable Agricultural Practice Adoption among Smallholder Farmers in China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Tan, Z.; Tang, Z. Sowing Uncertainty: Assessing the Impact of Economic Policy Uncertainty on Agricultural Land Conversion in China. Systems 2025, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Rizwan, M.; Abbas, A.A. Exploring the Role of Agricultural Services in Production Efficiency in Chinese Agriculture: A Case of the Socialized Agricultural Service System. Land 2022, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltering, L.; Fehlenberg, K.; Gerard, B.; Ubels, J.; Cooley, L. Scaling – from “Reaching Many” to Sustainable Systems Change at Scale: A Critical Shift in Mindset. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, W. The Impact of Socialized Agricultural Machinery Services on Land Productivity: Evidence from China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liao, J.; Hu, L.; Zang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Improving agricultural mechanization level to promote agricultural sustainable development. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Han, X. The Influence Paths of Agricultural Mechanization on Green Agricultural Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Piao, H. Does Agricultural Mechanization Improve Agricultural Environment Efficiency? Evidence from China’s Planting Industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 53673–53690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Punekar, R.M. A Sustainability-Oriented Design Approach for Agricultural Machinery and Its Associated Service Ecosystem Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Yuan, R.; Luo, M. Impact and Spatial Effect of Socialized Services on Agricultural Eco-Efficiency in China: Evidence from Jiangxi Province. Sustainability 2024, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Y. Can Land Trusteeship Improve Farmers’ Green Production? China Rural Econ. 2019, 10, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Zhou, L.; Ying, R.; Pan, D. Time Preferences and Green Agricultural Technology Adoption: Field Evidence from Rice Farmers in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgendi, B.G.; Mao, S.; Qiao, F. Does Agricultural Training and Demonstration Matter in Technology Adoption? The Empirical Evidence from Small Rice Farmers in Tanzania. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.O.; Ichino, A. Estimation of Average Treatment Effects Based on Propensity Scores. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2002, 2, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Cai, B.; Meseretchanie, A.; Geremew, B.; Huang, Y. Agricultural Socialized Services to Stimulate the Green Production Behavior of Smallholder Farmers: The Case of Fertilization of Rice Production in South China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1169753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Gao, Q.; Qiu, Y. Assessing the Ability of Agricultural Socialized Services to Promote the Protection of Cultivated Land among Farmers. Land 2022, 11, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Hu, X.; Chunga, J.; Lin, Z.; Fei, R. Does the Popularization of Agricultural Mechanization Improve Energy-Environment Performance in China’s Agricultural Sector? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Zhou, J.; Zou, W. Effects of land trusteeship on fertilizer input reduction: Mechanism and empirical test. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Deng, H.; Kong, R.; Wang, R.; Yu, G. Impact of agricultural productive services on the green transformation of cotton growers’ production. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2025, 39, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Luo, B.; Hu, X. Determinants of Farmers’ Fertilizers and Pesticides Use Behavior in China: An Explanation Based on Label Effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 123054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).