Abstract

Digital inclusive financial services are an important external force driving the common prosperity of Chinese farmers, while the sustainable development of household livelihoods is an internal guarantee for their common prosperity. The synergistic interaction between internal and external factors is an inherent requirement for promoting the common prosperity of farmers. Based on survey data from 467 households in Zhejiang Province, China, this study incorporates a qualitative comparative analysis method into a sustainable livelihood framework, establishing five antecedent variables and conducting necessity and sufficiency analysis. It has been found that single-factor conditions are not necessary for the common prosperity of farmers. However, the combination of digital inclusive financial services, household livelihood strategies, modern agricultural development, and rural governance conditions can generate multiple equivalent pathways to promote the common prosperity of farmers. These pathways include the synergistic path between digital inclusive finance and the business-based livelihood strategy, the synergistic path of digital inclusive finance, modern agricultural development, and business-based livelihood strategies, and the synergistic path of digital inclusive finance and rural governance for business-based livelihood strategies. In addition, digital inclusive financial services are identified as the core condition influencing common prosperity among farmers, while livelihood capital serves as a supporting condition for promoting their common prosperity. Rural governance and modern agricultural conditions have a substitutive effect on the impact of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity.

1. Introduction

In advancing the process of Chinese-style modernization, achieving common prosperity for rural areas and farmers is of paramount importance to the common prosperity of all people. However, rural residents still face significant disparities compared to urban residents in terms of income inequality, social security, and equal opportunities. According to the data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the income gap between urban andrural residents has been decreasing, with the income ratio dropping from 2.74 in 2000 to 2.45 in 2022. The average income growth gap between urban and rural residents has been reversed from 2.4% in 2010 to −0.1% in 2022. Nevertheless, the absolute income gap for urban residents continues to widen, increasing from CNY 3974 in 2000 to CNY 29,150 in 2022. Furthermore, China’s Gini coefficient was 0.47 in 2022, significantly higher than that of developed economies in Europe and America [1]. In terms of social security disparities, despite the gradual integration through years of reform, the fragmented and differentiated social security system is moving towards unity; however, there is still a bias towards urban areas in social security expenditure [2]. The uneven development of information technology in basic education in China has highlighted the digital divide, leading to unequal distribution of public education resources between urban and rural areas, the inadequate development of high-quality teaching staff, and the increase in educational inequality [3]. In addition, there is a significant disparity in healthcare and elderly care benefits between urban and rural residents, and there are still some unfair differences in opportunities between urban and rural families, such as obstacles in upward intergenerational mobility in terms of career and education for children in rural families [4].

Digital inclusive finance is an important lever to balance fairness and efficiency in the process of achieving common prosperity. The research conducted by the Consultative Group on Poverty Alleviation of the World Bank [5] and the Rural Development Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences indicates that digital inclusive finance refers to digital access to and utilization of various financial services by populations who are excluded from or underserved by the formal financial sector. These services include credit loans, payments, investments, insurance, monetary funds, and credit services. Digital inclusive finance represents a fusion form of technological innovation and financial innovation. It empowers traditional financial services through information and digital technology, resulting in a new financial model characterized by a broader range of participants and greater coverage across various sectors [6]. This is achieved through technologies such as mobile payments, artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, blockchain, and others [7]. A good example here is the Ant Group, a well-known Internet company. The company provides digital inclusive financial services to small and micro enterprises, self-employed households, farmers, and individuals. Among these services are digital payment options such as face-swiping payments and QR code payments offered to consumers through Alipay. In addition, Alipay provides credit purchasing and loan services through products like Huabei and Borrowing. Furthermore, it offers financial products such as Yu’ebao money market funds, bond funds, and insurance services. Based on this information, Peking University has developed the digital inclusive finance index, which is widely used by researchers.

Digital inclusive finance influences farmers’ livelihood activities through two primary channels: the expansion of financial services and the advancement of technological capabilities. On the one hand, by extending horizontally, the accessibility and popularization of financial services and products, digital inclusive finance will enhance the accessibility and immediacy of financial resources for vulnerable groups [8], increase financing opportunities and livelihood capabilities for rural households, and reduce financing costs. On the other hand, through the use of information technologies such as artificial intelligence and cloud computing, digital inclusive finance can alleviate the problem of financial resource mismatch, promote social equity [9], and strengthen social insurance and education equity [10].

Existing research based on regression analysis methods has yielded substantial findings regarding the linear impact mechanism of digital inclusive finance in promoting common prosperity among farmers. Studies have explored direct effects [11,12], mediating the effects of factors such as non-agricultural employment, industrial structure upgrading, and high-quality agricultural development on digital inclusive finance [13,14], as well as the moderating effect of infrastructure on digital inclusive finance [15]. However, these studies rely mainly on net effect explanations using multiple regression methods, often employing interaction terms to examine the contingent relationships of digital inclusive finance. This approach may lead to incomplete equivalence between causal variables and outcome variables. In addition, it may fail to reflect the asymmetric relationships among the causal variables and overlook combined or substitution effects of digital inclusive finance with household livelihoods and macro factors.

The sustainable livelihood framework provides methods and ideas for analyzing the livelihood outcomes of farmers’ common prosperity. Under this framework, common prosperity among farmers is the result of interactions between livelihood assets, livelihood strategies, external public services (such as digital inclusive finance), structures, and institutions. This study introduces a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) method into the sustainable livelihood framework from a configurational perspective to explore the causal complexity between digital inclusive finance, farmers’ livelihoods, and common prosperity. This research focuses on the following three questions: What are the core conditions and configurational patterns that promote common prosperity among farmers? How do the configurational patterns of achieving common prosperity differ from those of non-common prosperity outcomes? What kind of substitution, adaptation, and complementary relationships exist between different configurations?

This article contributes to the extant literature in two ways. On one hand, this study examines the complex driving mechanisms of rural households’ common prosperity by integrating five categories of antecedent conditions, namely digital inclusive financial services, modern agricultural development, rural governance, livelihood capital, and livelihood strategies from the perspective of internal and external interactions. On the other hand, it expands the application scope of sustainable livelihood frameworks, and it further analyzes how the combination between digital inclusive finance and rural households’ livelihood can achieve a “joint effect” in promoting rural households’ common prosperity. The research findings provide a systematic and comprehensive explanation of the complex relationships among the antecedent conditions of rural households’ common prosperity and offer differentiated equivalent solutions for achieving rural households’ common prosperity.

The remaining sections of this article are organized as follows: The second section is a literature review and theoretical framework. The third section discusses research methods, data, and calibration, while the fourth section presents empirical results analysis. Last but not least, the fifth section presents the discussion and conclusions.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Relationship Between Family Livelihood and Common Prosperity of Farmers

Several studies suggest that abundant livelihood capital serves as a fundamental foundation for rural households to achieve common prosperity. This capital encompasses various dimensions, including material assets such as housing and vehicles [16]; human capital, reflected in education and health levels; natural capital, like arable land [17]; social capital, including trust, social participation [18], and social network advantages [19]; and financial capital, such as household net income. These forms of capital have been shown to significantly contribute to the common prosperity of rural households. Additionally, rural households with high levels of digital literacy are more likely to increase property income in the short term and optimize income distribution in the long term [20]. Finally, adopting business-based livelihood strategies acts as a key mediating mechanism through which digital inclusive finance promotes common prosperity among rural households [21].

2.2. The Relationship Between Digital Inclusive Finance and the Common Prosperity of Farmers

Digital inclusive finance plays a significant role in directly promoting the common prosperity of rural households. Compared to the characteristics of information technology, the impact of financial inclusiveness on advancing common prosperity is more substantial. Overall, the development of digital inclusive finance has a stronger effect on increasing the income of low-income farmers [22] and contributes to narrowing income disparities among residents. From a multidimensional perspective, the breadth of coverage, depth of usage, and level of digitization of digital inclusive finance all exert significant positive effects on the achievement of common prosperity [23].

Digital inclusive finance optimizes household livelihood strategies to achieve common prosperity for farmers. Related studies have shown that digital inclusive finance can enhance the farmers’ livelihood strategies. Apart from increasing non-agricultural employment opportunities and entrepreneurial activity [24], it strengthens the “bundling effect” between non-agricultural entrepreneurship and employment [25] and facilitates the upgrading of household consumption, thereby contributing to the realization of common prosperity. Furthermore, digital inclusive finance promotes rural residents’ participation in financial markets [26], improves credit accessibility [27] and creditworthiness, alleviates the financial constraints faced by farmers, and supports progress towards common prosperity.

Macro factors play a mediating role in promoting common prosperity among farmers through digital inclusive finance. Related studies suggest that the high-quality transformation of industries serves as a key mediating factor through which digital inclusive finance promotes common prosperity among farmers. This includes upgrading industrial structures, revitalizing rural industries, promoting high-quality agricultural and rural development, and enhancing overall economic vitality [28]. In addition, regional resource endowments and infrastructure also play intermediary roles. For example, digital inclusive finance can facilitate the efficient flow of innovative factors [29] and mitigate structural mismatches. However, the effect of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity may be constrained by macro-level conditions such as the quality of regional transportation and information infrastructure.

2.3. A Configuration Analysis Framework Based on a Sustainable Livelihood Framework

Existing research has provided rich explanations for how digital inclusive finance promotes the common prosperity of rural households. However, the current research approaches using traditional linear and one-way causal measurement methods are unable to explain the “complex causality of multiple factors”. This is because common prosperity is a dynamic concept that integrates processes and results in a progressive manner [30]. For rural households, common prosperity is both a livelihood outcome and a dynamic process of combining their own livelihood capital conditions with external institutional conditions, structural conditions, and service conditions; adjusting livelihood strategies; and achieving the goal of common prosperity. Therefore, attention should be paid to which configurations of internal and external condition variables will lead to the production of common prosperity outcomes for rural households, as well as which configurations of conditions will lead to the emergence of non-common prosperity outcomes.

In the field of rural livelihood research, a widely accepted analytical method is the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) developed by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) in 2000. It is a standardized and systematic approach used to examine and analyze the complex factors contributing to rural poverty, as well as to reveal the interactive relationships among the factors influencing rural livelihood outcomes.

The framework comprises the following five components: Vulnerability Context, Livelihood Assets, Structures & Processes, Livelihood Strategies, and Livelihood Outcomes. Specifically, the Vulnerability Context relates to the external environment and includes Trends, Shocks, and Seasonality. Livelihood capital refers to the various resources owned by households, which encompass natural capital, material capital, human capital, financial capital, and social capital. Structures are the organizations—both private and public—that formulate policies or provide services. Processes refer to the policies, legislation, institutions, and culture that shape livelihoods. Livelihood Strategies highlight the range and combination of activities and choices that individuals undertake to achieve their livelihood goals. Finally, Livelihood Outcomes are the achievements or outputs of Livelihood Strategies, which may include increased income, enhanced well-being, and other benefits.

The sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) describes how farmers optimize their livelihood strategies and achieve positive outcomes through livelihood capital and external public services, all within the context of risk, vulnerability, and changing structures and processes. It is important to note that the framework does not operate in a linear manner, rather, it emphasizes the multiple interactions among the various factors that influence livelihoods. In addition, the qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) method focuses on analyzing the complex causal relationships through configurational thinking from a holistic perspective. Therefore, the integration of SLF and QCA is a feasible approach.

Based on the current situation of China’s rural system and development, Ding et al. (2016) proposed that public service conditions are distinct from structures and processes when studying the livelihood issues of displaced farmers [31]. In their research on the impact of tourism development on farmers’ livelihoods, Zhang et al. emphasized that government investment functions as both a structure and a process [32]. Building on their findings, we argue that digital inclusive finance, as a financial service established by the private sector, is beneficial for improving the livelihood development of vulnerable groups. It serves as an external financial service condition that influences the livelihood outcomes of farmers. Government-led rural governance and modern agricultural development also act as structures and processes, highlighting the distinction between these two concepts.

Overall, the development of digital inclusive finance, rural governance, and modern agriculture positively impacts the reduction in external livelihood vulnerabilities. However, it is important to acknowledge that digital finance may also present external risks, such as potential property losses due to fraud and loopholes in its implementation.

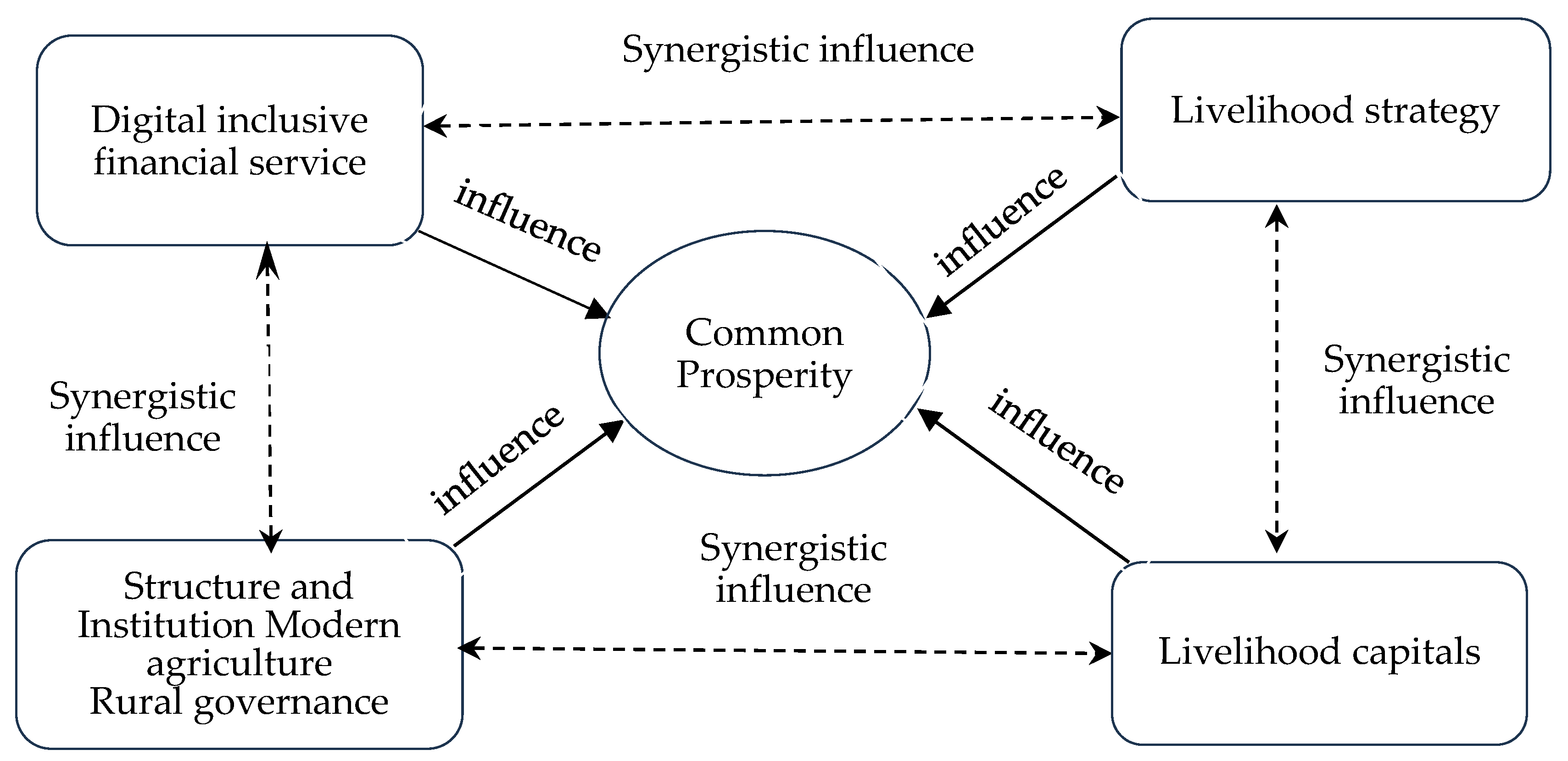

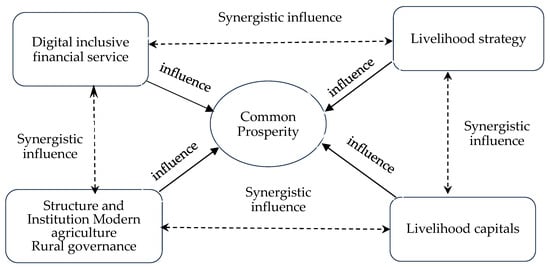

Therefore, this article draws on the sustainable livelihoods framework and introduces the QCA method to construct a theoretical analytical framework, which is shown in Figure 1. This framework helps to explore the synergistic effects of household livelihood capital and strategies, external digital inclusive financial services factors, and modern agriculture, as well as rural governance factors, on rural households’ common prosperity, revealing the configuration paths among different influencing factors.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model for achieving common prosperity among farmers based on a sustainable analysis framework.

- Achieving common prosperity for all is a long-term goal proposed by the Chinese government. The official definition of common prosperity encompasses a living state of prosperity, spiritual confidence, and self-improvement; a livable and business-friendly environment; social harmony; and universal public services, all attainable through hard work and mutual assistance1. Yu and Ren argue that common prosperity is about compensating for and correcting the inequalities caused by institutional factors [33], ensuring that everyone has the opportunity and ability to equally participate in high-quality economic and social development, and to share the benefits.

- For farmers, common prosperity encompasses two levels: sharing and prosperity. The sharing level emphasizes fairness and reflects the breadth of common prosperity’s coverage. In contrast, the prosperity level focuses on efficiency, which includes material and spiritual common prosperity. Therefore, common prosperity is seen as a positive and multidimensional livelihood outcome.

- Public service conditions are an important factor restricting the livelihood development of farmers [31], and digital inclusive finance is an important rural public service infrastructure, which plays an important supporting role in rural revitalization and common prosperity of rural farmers. This article employs the “Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index” (PKU-DFIIC) data developed by the Peking University Digital Finance Research Center. This dataset includes county-level digital inclusive finance indexes, along with the following three sub-dimensions: coverage breadth, usage depth, and degree of digitalization. The coverage breadth refers to the number of electronic accounts, including Internet payment accounts and the number of bank cards linked to them [34]. The usage depth reflects the quantity and activity of digital financial services, encompassing payments, monetary funds, credit, insurance, investment, and credit services, represented by a total of 21 indicators. The degree of digitization indicates the convenience, low cost, and trustworthiness of digital financial services, measured by the proportion of mobile payments, QR code payments, and Huabei payments, totaling 10 indicators. Digital inclusive financial services can influence the common prosperity of farmers by enhancing their financial literacy and increasing their property income. For farmers engaged in business-based livelihood strategies, the development of digital inclusive finance can alleviate their financing constraints. In addition, digital inclusive financial services can be integrated with structures, institutions, and livelihood strategies to influence the common prosperity of farmers.

- As an external factor in the SLF, structures and institutions refer to policy and institutional factors that can impact farmers’ livelihoods, including government investments and community governance. In the process of demonstrating Zhejiang Province’s high-quality creation of a rural revitalization project and promoting the demonstration areas for common prosperity, the development of modern agriculture and innovative rural governance are important focal points [35]. Therefore, this study incorporates county-level indicators of modern agricultural development and county-level rural governance to examine the combined effect of structural and institutional factors in promoting farmers’ common prosperity through digital inclusive finance.

- The characteristics of modern agriculture are reflected in its digital, technological, mechanized, green, and intensive development [36,37]. Evaluation indicators typically include digital modernization [38], production modernization, business modernization, and industrial modernization [39], among others. Building on this foundation, this article examines modern agriculture from the perspectives of production, supply, and sales. The rapid advancement of modern agriculture can encourage farmers to engage in production, supply chains, and other related activities, enabling them to earn labor remuneration or income from agricultural product sales, thus increasing their household income. Simultaneously, the development of modern agriculture may also collaborate with digital financial services and rural governance to foster common prosperity for farmers.

- Rural governance refers to the management of social and economic issues in rural areas, including public safety, healthcare, social security, cultural education, and conflicts of interest. This is achieved through methods such as autonomy, rule of law, and moral governance, with the aim of promoting fairness, vitality, harmony, and order in rural society [40]. From a policy perspective2, it emphasizes a governance system that blends autonomy, rule of law, and moral governance under the leadership of Party organizations, outlining the goals and tasks necessary to enhance rural public services, public management, and the guarantee of public safety. The level of rural governance encompasses governance methods, processes, and effectiveness.

- This article utilizes the digital rural governance index to reflect modern governance approaches, while the urban–rural income gap serves as an indicator of governance effectiveness. Effective rural governance can facilitate farmers’ participation in social governance, enhance their access to social security—in areas such as education, healthcare, and elderly care—and improve the ecological environment of rural regions, thereby increasing their sense of well-being and happiness. In addition, rural governance may synergize with the development of digital finance and modern agriculture. It is important to note that rural governance and household livelihood strategies can lead to different livelihood outcomes.

- As a core element of the SLF, livelihood capital refers to the assets and resources that households possess, including physical capital, human capital, social capital, and financial capital. On one hand, the advancement of external digital inclusive financial services, along with the enhancement of rural governance and the rapid development of modern agriculture, can assist farmers in improving their livelihood capital. On the other hand, livelihood capital itself can also independently promote common prosperity among farmers. Advantages in livelihood capital contribute to common prosperity. Furthermore, livelihood capital may also combine with three external conditions to exert its influence. Even without an advantage in livelihood capital, high levels of digital inclusive financial services, favorable structural and institutional conditions, or a synergistic configuration of these factors can also help households to achieve positive common prosperity results.

- Livelihood strategies are different combinations of livelihood activities adopted to achieve specific livelihood goals [41]. The main livelihood strategies of Chinese farmers include agricultural livelihood, part-time livelihood [42], non-agricultural livelihood [43], and migrant livelihood [44]. Choosing different livelihood strategies is not only influenced by the accumulation of livelihood capital, but also constrained by external factors such as structure, system, and digital inclusive services. Meanwhile, different livelihood strategies can directly lead to different levels of common prosperity. The combination of different livelihood strategies with external factors such as structure, system, and digital inclusive services will also produce different results of common prosperity.

3. Research Methods, Data, and Calibration

3.1. Qualitative Comparative Analysis Method

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is a method based on Boolean algebra and set theory for analyzing configurations. By examining the sufficient and necessary subset relationships between antecedents and outcomes, it seeks to explore the mechanisms of complex social issues induced by multiple concurrent causes [45,46]. The strength of QCA lies in describing causal relationships through set relationships, thus avoiding the endogeneity issues found in in traditional correlation analysis. Moreover, as it does not rely on random sampling, the sampling bias under the assumptions of traditional random sampling is reduced [47].

In comparison to traditional quantitative and case analysis, this study employs QCA for three reasons. Firstly, the QCA methodology can analyze the diverse and complex relationships of preconditions for rural households to achieve common prosperity. The existing research mainly focuses on the direct impact of digital inclusive finance on rural households’ common prosperity or the interactive effects between digital inclusive finance and rural livelihoods (borrowing, digital literacy, etc.), such as moderating and mediating effects. However, these studies fail to discuss the interdependent and synergistic complex causal relationships. In contrast, the QCA methodology starts from a holistic perspective, revealing the synergistic causal relationships among different combinations of household livelihoods, digital inclusive financial services, structural and institutional factors, and the outcomes of rural households’ common prosperity. Secondly, the QCA methodology is equipotent, capable of uncovering different combinations of preconditions that can form multiple “equifinal” causal chains [48] and disclosing various implementation paths and core condition combinations for rural households’ common prosperity. Thirdly, the QCA methodology exhibits causal asymmetry. In real scenarios, the combinations of conditions that lead to rural households’ common prosperity are not the reverse conditions that cause rural households to be non-commonly prosperous, whereas traditional regression methods and correlation analysis follow symmetric relationships. Therefore, by employing the QCA methodology, this study can explore the causal asymmetrical relationships among household livelihoods, digital inclusive financial services, structural and institutional factors, and rural households’ common prosperity.

3.2. Data Source

This study used rural survey data generated in Zhejiang Province from July to August 2021. The survey adopted stratified sampling method for cities in Zhejiang province, including Hangzhou, Ningbo, Jiaxing, Shaoxing, Zhoushan, Quzhou, Jinhua, Taizhou, and Wenzhou. To align with macro data, 467 completed questionnaires were obtained. In addition, data on digital inclusive finance were sourced from the 2020 Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index, while data on the level of modern agriculture and rural digital governance indicators were sourced from 2020 Peking University Rural Digital Data. The urban–rural income gap indicator uses data from the 2020 Statistical Yearbook of each county.

3.3. Variable Setting

3.3.1. Result Variables

Existing research on rural household common prosperity measurement includes single and multidimensional approaches. Some studies suggest that measures such as the relative income gap and urban–rural income disparity reflect the level of rural household common prosperity [49,50,51]. Others propose multidimensional indicators and measurement methods for rural household common prosperity, such as the five dimensions of income, health, education, security, and employment put forward by Liu & Luo [17]; and the five dimensions of economy, medical health, education, mental state, and living standards proposed by Tan et al. [52], all applying an equal-weight scoring method to measure rural household common prosperity.

This study utilizes three categories of indicators proposed by Zhang and Wang [53], including prosperity, sharing, and sustainability, to assess rural household common prosperity. The sharing indicator assesses the equitable development opportunities and achievements among families, while the affluence indicator measures the material common prosperity of these families. Sustainability evaluates the accessibility of the community living environment and public services. Furthermore, to avoid the drawbacks of equal-weight methods simplifying the importance of different dimensional indicators, this study treats rural household common prosperity as a latent variable, estimating its value using graded response models. This advantage lies in its ability to reflect the differences in indicator weights. Finally, the estimated values are normalized, with the rural household common prosperity result variable ranging from 0 to 1, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement indicators for common prosperity of rural households.

3.3.2. Conditional Variables

- ①

- County-level development of inclusive digital finance.

To examine the overall level of digital inclusive finance development and its potential different effects on rural households’ common prosperity, the total index, the index of digital financial coverage breadth, the index of digital financial usage depth, and the index of inclusive financial digitization level from the 2020 Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index were used (see Table 2). To match the other conditional variables, the four indices were normalized [54].

Table 2.

Variable setting and assignment.

- ②

- Modern agricultural level in county areas.

The main pathways through which farmers integrate into modern agricultural development to achieve income growth and common prosperity include modern information technology [55], specialized production [56], supply chain integration and supply chain learning, and digital marketing platforms [57], among others. This study uses indices from 2020 Peking University Digital Rural Data, including digital production, digital supply chain, and digital marketing. They are used to evaluate the role of production, supply chain, marketing, and other aspects of modern agriculture in promoting common prosperity for farmers. In addition, through applying the entropy method to fit indices for the three indicators and normalizing them, the comprehensive index value ranges from 0 to 1.

- ③

- County-level rural governance.

The level of rural governance reflects the modern means and positive effects of rural governance. On the one hand, the modern means of rural governance adopt the digitalization index of rural governance from 2020 Peking University Digital Rural Data. This index includes metrics such as the number of real-name users of Alipay, the number of government service users, and the proportion of villages and towns that have established WeChat public service platforms. On the other hand, the core goal of rural governance driving common prosperity is to narrow the income gap between urban and rural residents [58]. This article employs resident income data from county-level statistical yearbooks to assess the urban–rural income gap. This study uses the entropy method to fit the indices of the two indicators and normalize them, with the value of the composite index ranging from 0 to 1.

- ④

- Household livelihood capital.

According to research by Ding et al. [31], livelihood capital mainly includes material capital, financial capital, and social capital, using indicators such as household housing area, total household income, the number of closely connected families in the village, and family members including civil servants, employees of institutions, teachers, and doctors. After fitting the indicators with the entropy method and normalizing them, the value of the composite index ranges from 0 to 1.

- ⑤

- Household livelihood strategies.

Livelihood strategies classify different combinations of livelihood strategies of farmers. Referring to Walelign’s classification method [59], whether income from different sources accounting for 50% or more is considered the standard [21,60], and households’ livelihood strategies are categorized into a wage labor livelihood strategy, a subsistence livelihood pattern, and a business-based livelihood strategy. Different livelihood strategy variables are assigned values of 0 and 1, belonging to a clear set of data.

3.4. Calibration

Prior to the analysis of necessity and sufficiency, it is necessary to calibrate the sample data by transforming variable values into set membership degrees. This study utilizes direct calibration to convert the sample data into fuzzy set membership scores. For the weighted data, three calibration anchor points are established based on the research methods of Ong and Johnson [61], Zhou Jian, and Du Hongmei, as follows: one standard deviation above the mean; one standard deviation below the mean; and the mean, representing complete membership, complete non-membership, and the crossover point, respectively, as detailed in Table 3. In addition, a +0.001 adjustment is applied to data with a membership degree of 0.500 [62].

Table 3.

Variable calibration anchors and descriptive statistics.

4. Empirical Result Analysis

4.1. Univariate Necessity Analysis

The purpose of a necessity analysis is to examine whether a single variable can constitute a necessary condition for the outcome. If a precondition always exists when a certain result occurs, then that condition is a necessary condition for that result. Typically, a condition is considered necessary when its consistency is greater than 0.9 and its coverage is greater than 0.5. As shown in Table 4, none of the conditional variables are indispensable conditions for both rural common prosperity and non-common prosperity. This indicates that individual variable conditions alone cannot explain the logic behind the formation of rural common prosperity; moreover, the relationship between the outcome of rural common prosperity and its antecedent conditions is a complex and concurrent causal relationship. Therefore, promoting rural common prosperity requires a comprehensive consideration of the farmers’ own conditions (livelihood capital and livelihood strategies) as well as the synergistic interactions among regional conditions, such as inclusive digital financial development, modern agricultural development, and rural governance.

Table 4.

Necessity analysis results of conditional variables.

4.2. Conditional Configuration Analysis

Configurational analysis aims to reveal different configurations or pathways of multiple antecedents needed to produce a particular outcome. Consistency is a key indicator of configurational sufficiency. Based on the existing research, the original consistency threshold is set at 0.8, the PR consistency threshold is set at 0.7, and the case frequency threshold is set at 4. In counterfactual analysis, it is assumed that the presence or absence of individual antecedents can contribute to the level of farmers’ common prosperity. The results in Table 5 primarily identify the core conditions and marginal conditions for farmers’ common prosperity through using the intermediate solution as the main reference and the simple solution as the secondary reference. According to a study by Du and Jia [45], conditions that appear simultaneously in the intermediate and simple solutions are defined as core conditions for common prosperity, while conditions appearing only in the intermediate solution are defined as marginal conditions for common prosperity. Core conditions play a dominant role in farmers’ common prosperity, while marginal conditions have a supportive role.

Table 5.

The configuration results of common prosperity.

In this study, there are three livelihood strategies, including farming strategy, labor migration strategy, and business-based strategy. The livelihood strategy for migrant workers is used as reference. The results indicate four configuration paths that promote the common prosperity of households, with consistency levels exceeding 0.8 each, specifically 0.819, 0.820, 0.858, and 0.893, suggesting that these four configurations constitute sufficient conditions for the common prosperity of households. The consistency level of the model solution is 0.812, indicating that the four configurations collectively constitute sufficient conditions for the common prosperity of households. In addition, the overall coverage is 0.288, indicating that the four configurations collectively explain a considerable degree of the variability in the common prosperity of households.

4.2.1. Analysis of the Configuration Path for Generating High-Level Common Prosperity Results

Household livelihood capital is a constant supporting condition for the common prosperity of farmers, rather than a core condition. Configurations H1~H3 indicate that a high level of livelihood capital serves as a marginal condition for farmers to achieve common prosperity. Even if a family possesses abundant livelihood capital, it does not necessarily lead to common prosperity. However, livelihood capital can explain certain situations.

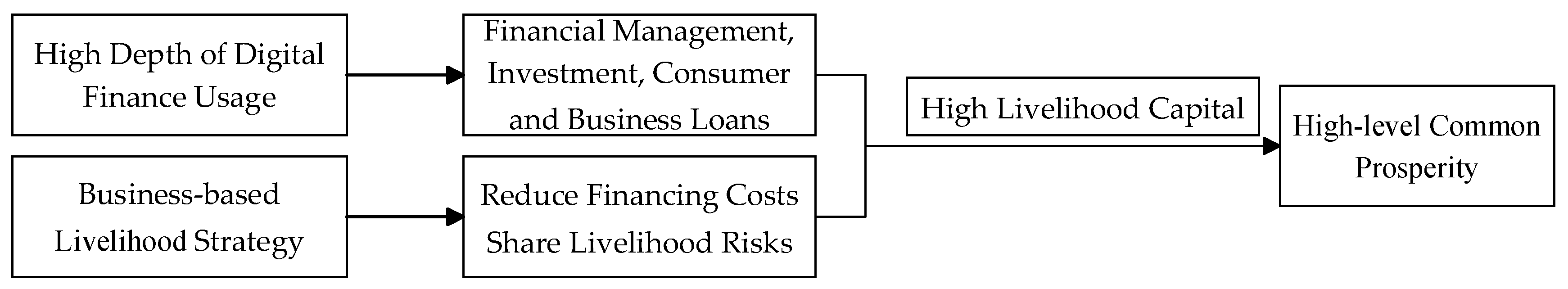

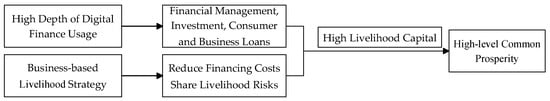

The configuration of H1 (Figure 2) indicates that non-high digital inclusive finance, non-high digital financial coverage, non-high rural governance level, high depth of digital finance usage, and the livelihood strategy are core conditions, with high livelihood capital, the non-agricultural livelihood strategy, and the level of digital inclusiveness in finance as marginal conditions, leading to common prosperity among rural households. This configuration suggests that, even if the overall level of digital inclusive finance development in a region is not high and rural governance is limited, if there is a high level of synergy between the depth of digital inclusive finance usage in the region and the livelihood capital of rural households, they can achieve a high level of common prosperity. The possible reason for this is that families with abundant livelihood capital engage in the business-based livelihood strategy by extensively using digital inclusive finance for financial services such as financial management, investment, consumer loans, and business loans, through which they can reduce financing costs [63], increase property income, and promote material common prosperity. The government should encourage farmers to purchase commercial medical insurance and commercial pension insurance to share livelihood risks and enhance their livelihood capabilities.

Figure 2.

Synergistic path between digital inclusive finance and business-based livelihood strategy.

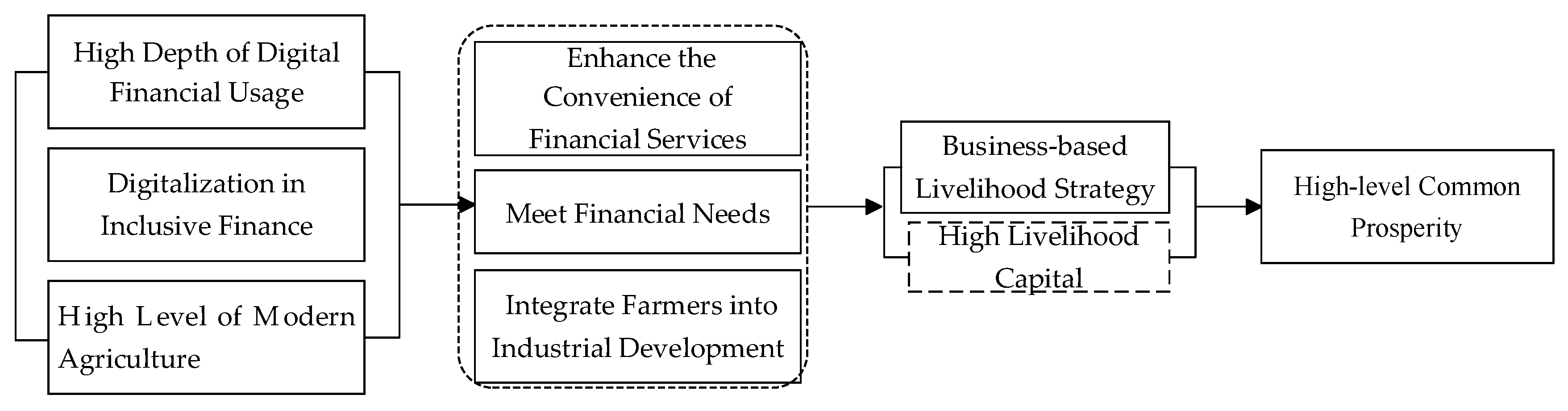

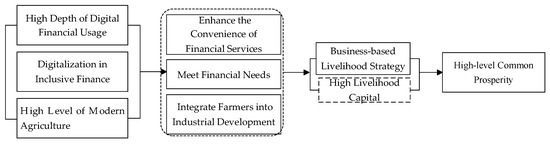

There is a synergistic path of digital inclusive finance, modern agricultural development, and advantageous livelihood strategies. Configuration H2 (Figure 3) indicates that core conditions include a high depth of digital financial usage, a level of digitalization in inclusive finance, the business-based livelihood strategy, a high level of modern agriculture, and non-high rural governance level, while marginal conditions include high livelihood capital, high digital inclusive finance, extensive coverage of digital finance, and the non-agricultural livelihood mode. Both lead to the collective prosperity of farmers. This configuration suggests that, even with limited rural governance levels, the combination of high-level regional digital inclusive finance and high-level regional modern agricultural development conditions helps to promote high-level common prosperity for farmers who have accumulated abundant livelihood capital and are primarily engaged in entrepreneurship. A possible reason for this is that the high depth and digitalization level of regional digital inclusive finance can actively enhance the convenience of financial services, provide opportunities for low-income groups to access financial services, reduce financing costs, effectively meet families’ financial needs, and promote entrepreneurial opportunities for farming households [64]. Simultaneously, high-level modern agricultural development contributes to integrating business-based farmers into industrial development. The synergy between regional financial elements and modern agricultural development strengthens farmers’ livelihood capital, optimizes livelihood strategies, and effectively drives farmers towards common prosperity.

Figure 3.

Synergistic path of digital inclusive finance, modern agricultural development, and business-based livelihood strategies.

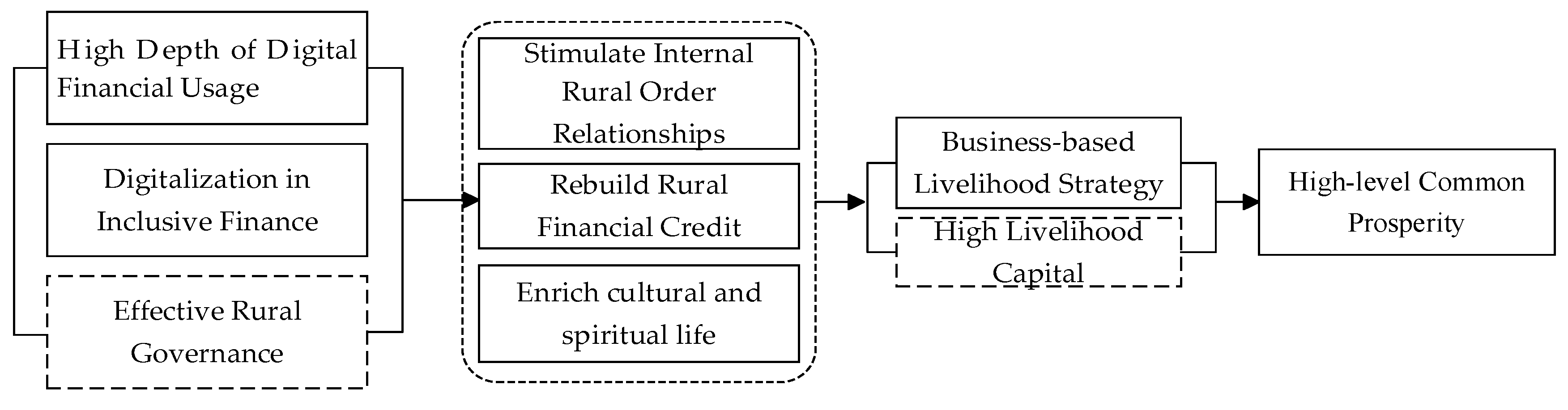

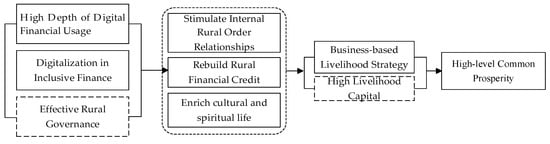

There is a synergistic path of digital inclusive finance and rural governance for advantageous livelihood strategies. The configuration in H4 (Figure 4) indicates that high levels of digital financial usage, the degree of inclusiveness in digital finance, livelihood strategies in entrepreneurship, and the level of non-modern agricultural practices are core conditions, while high-level livelihood capital, inclusive digital finance, extensive digital financial coverage, effective rural governance, and non-agricultural livelihood strategies are marginal conditions that lead to common prosperity among farmers. This configuration suggests that, even with limited levels of modern agricultural development, the combination of high-level regional digital inclusive finance and effective rural governance can promote high levels of common prosperity among farmers who have accumulated abundant livelihood capital and engage primarily in entrepreneurship or wage labor. Possible reasons for this include the contribution of digital inclusive finance towards improving rural social autonomous units, incentive and constraint mechanisms, and multi-governance subject participation, which stimulate internal rural order relationships, rebuild rural financial credit systems, support the modernization and transformation of rural governance [65], and enhance the common prosperity in aspects such as farmers’ spiritual culture and social security.

Figure 4.

Synergistic path of digital inclusive finance and rural governance for business-based livelihood strategies.

4.2.2. Analysis of Configuration Paths for Generating Non-High Common Prosperity Results

This study further analyzes the configuration paths of non-common prosperity, which aligns with the consistency threshold and frequency threshold of common prosperity. Table 6 shows that there are six conditions for non-common prosperity configuration. The results indicate that low-level regional inclusive financial development is a common core condition leading to non-common prosperity among households. Even with high-level regional modern agricultural development, good rural governance, rich livelihood capital of households, and business livelihood strategies, it is difficult for households to achieve common prosperity without the support of regional inclusive financial services. In addition, the lack of high levels of modern agricultural development, rural governance, and other structural and institutional conditions are also core conditions leading to non-common prosperity. In addition to that, household factors, such as livelihood strategies of farming and working, are only marginal conditions leading to non-common prosperity in certain situations.

Table 6.

Configurations of non-high common prosperity.

4.3. Robustness Test

Drawing on the discussion of robustness testing in QCA by Zhang and Du (2019), this study conducts a robustness test on the antecedent configurations of rural common prosperity by adjusting the consistency threshold and case frequency [66]. Table 7 presents the results when the original consistency level is 0.75 and the case number threshold is 2. Initially, with a consistency threshold of 0.75, configurations R1–R3 are largely consistent with H1–H3, with an overall consistency of 0.796 and a coverage of 0.378. Subsequently, with a case number threshold of 2, configurations R4–R6 are identical to H1–H3, yielding an overall consistency of 0.812 and a coverage of 0.300. The robustness test gives us the robustness results.

Table 7.

Robustness test.

To enhance the objectivity of causal inference, this study employs Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to simulate a quasi-natural experiment by matching samples and addressing endogeneity concerns. Due to the absence of direct variables indicating whether farmers participate in digital finance, this study constructs an interaction term—home Internet access × county-level digital inclusive finance index—as a proxy treatment variable to indirectly capture the farmers’ practical ability to engage with digital finance. Households are categorized into two groups based on Internet access: “access” and “non-access”. Similarly, counties are divided into “high” and “low” digital finance levels using the median index value. Farmers located in counties with high digital finance development and home Internet access constitute the treatment group, while the remaining three combinations (lacking access or regional infrastructure) form the control group.

On this basis, PSM is applied to control for a set of household-level covariates. To assess post-matching balance, this study conducts t-tests on covariate means and examines Standardized Mean Differences (SMDs). The results indicate no significant differences in covariate means between the matched treatment and control groups (p > 0.10), and all SMDs are below the 20% threshold. This suggests improved comparability and provides a sound basis for estimating the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT). Furthermore, this study evaluates matching quality using Rubin’s (2001) criteria, including Rubin’s B and Rubin’s R statistics [67]. The results in Table 8 indicate that Rubin’s B value is 25.6—close to the suggested threshold—while Rubin’s R is 0.61, well within the recommended range [0.5, 2.0]. These results indicate acceptable matching quality and support the validity of the interaction-based proxy as a measure of digital finance participation capacity.

Table 8.

Balance test results for matching variables.

Table 9 presents the estimated Average Treatment Effects on the Treated (ATT) under three different matching methods, all of which are statistically significant at the 1% level. These results provide robust evidence of a causal relationship between the farmers’ capacity to participate in digital inclusive finance and their level of common prosperity. Specifically, farmers residing in counties with a high level of digital financial development and who also have household Internet access exhibit a common prosperity level that is 0.065 units higher, on average, than that of the reference group.

Table 9.

Treatment effects under different matching methods.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

In the pursuit of rural prosperity, individual factors such as digital inclusive financial services, livelihood capital, livelihood strategies, modern agriculture, and rural governance, as well as macro factors, cannot independently promote the prosperity of households. Therefore, in the process of rural households seeking common prosperity, government departments should focus on the interactive relationship and coordinated development between regional factors and household factors [68]. This research conclusion differs from previous studies’ net effect results, as follows: the positive impact of better interpersonal relationships on enhancing the level of rural household prosperity [52], the significant promotion of rural household prosperity through the breadth and depth of digital inclusive financial coverage [23], and the significant improvement in rural household prosperity and the sharing of development outcomes through high-quality agricultural development [14].

Through further comparison of the configurations of the results of common prosperity and non-common prosperity, it has been found that the interdependence among various conditions and their synergistic effects lead to converging outcomes. Contrasting the results of H3 and H4 reveals a substitution relationship between modern agriculture and rural governance conditions. In areas where rural governance is underdeveloped, synergistic effects of high-level modern agriculture and inclusive digital finance can drive high-quality development of the agriculture industry, enabling households with abundant livelihood capital to start businesses, engage in commerce, seek non-agricultural employment opportunities, and achieve common prosperity. This research conclusion differs from traditional findings related to interaction effects and moderating effects, such as with the partial mediating role of agricultural total factor productivity and the level of transportation infrastructure in the enhancing effect of inclusive digital finance on common prosperity and the weakening effect of education level on the negative impact of inclusive digital finance on wage income inequality.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the survey data from Zhejiang farmers and Peking University, this article employs the QCA method to analyze the synergistic effects of internal and external factors such as digital inclusive finance, household livelihood capital, and strategies on the common prosperity of farmers, revealing the core conditions and complex pathways influencing farmers’ common prosperity. The results of the necessity analysis indicate that individual household livelihood factors, digital inclusive financial service conditions, and structural and institutional conditions are not necessary conditions for farmers’ common prosperity. The sufficiency analysis results show that there are three differentiated pathways leading to farmers’ common prosperity, namely the path of digital inclusive finance in combination with the farmers’ business-based livelihood strategy, the synergistic path of digital inclusive finance and modern agricultural development in combination with the farmers’ advantageous livelihood strategy, and the synergistic path of digital inclusive finance and rural governance in combination with farmers’ advantageous livelihood strategy. Furthermore, the low level of regional digital inclusive finance development is a common core condition leading to farmers’ non-common prosperity. When leveraging the combined effects of digital inclusive finance, there is a substitutive relationship between modern agriculture and rural governance conditions.

This article proposes the following policy recommendations. Firstly, promoting the coordinated development strategy of digital inclusive finance and farmers’ livelihood strategy through differentiation. For farmers with business livelihood strategies, it is recommended that the financial sector optimize the payment services, credit services, insurance services, and credit services provided to farmers. For traditional agricultural farmers, it is suggested that government departments strengthen the integration of modern agricultural production informatization and digital financial services. At the same time, this study emphasizes the need to enhance farmers’ digital literacy and skills, enabling them to effectively utilize digital inclusive financial services. This will facilitate their integration into the high-quality development of rural agriculture and governance, ultimately contributing to both economic prosperity and cultural enrichment.

Secondly, the digital financial ecosystem should be integrated with modern agricultural development resources to systematically support the optimization of farmers’ livelihood strategies. For counties with lower levels of digital finance development, it is recommended that government departments prioritize improvements in infrastructure, financial technology platforms, and service accessibility. Additionally, efforts should focus on enhancing public welfare programs that educate farmers on financial literacy and increasing subsidies for social security insurance, such as personal health insurance and policy-based agricultural insurance [69]. Furthermore, the government should strengthen agricultural technology services, promote the digitization and automation of production, enhance agricultural product branding and market connectivity, encourage moderate-scale operations, and support the development of the entire agricultural value chain. In addition, continuous improvements in agricultural infrastructure are necessary to enhance farmers’ capacity to engage in modern agriculture.

Finally, it is recommended that government departments coordinate and promote the integrated development of digital governance and digital finance in rural areas, supporting the accumulation of livelihood capital for farmers. It is suggested that a “data–service–finance” integrated system be established to enhance the efficiency of grassroots governance and public service delivery. By improving the accessibility of policies, credit, and market information, farmers’ ability to access and allocate resources can be strengthened. This will foster the accumulation of livelihood capital and the transition to sustainable livelihood strategies, ultimately contributing to the goal of common prosperity for farmers.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: First, from a theoretical perspective, this study employs the sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) to develop a conceptual mechanism through which digital inclusive finance contributes to common prosperity among the rural households. It identifies three distinct configurational pathways leading to this outcome. The findings enrich the theoretical discourse on inclusive digital finance by integrating the dimension of rural household livelihoods into its analytical scope. Second, with regard to practical implications, this study demonstrates that the advancement of common prosperity among rural households is not driven by linear relationships among individual factors such as livelihood capital, livelihood strategies, regional digital financial development, and modern agriculture. Instead, these elements interact in synergistic and configurational ways. This perspective transcends the limitations of traditional regression models based on linear causality and offers policy-relevant insights for designing rural digital finance strategies that are responsive to the heterogeneity of farmers’ livelihood strategies.

This study presents some limitations. Firstly, the data used in this study are cross-sectional, which means an examination of longitudinal dynamic changes is missing. In future studies, longitudinal household panel data spanning five-year intervals could be utilized to enhance causal inference. In particular, researchers may consider employing time-series qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to explore dynamic configurations. This approach would allow for a more nuanced investigation into how the evolution of digital inclusive finance, the accumulation of household livelihood capital, and transformations in livelihood strategies jointly influence the pathways towards achieving common prosperity. Secondly, in terms of measuring conditional variables, due to data limitations, the representation of variables is not precise enough. For example, the examination scope of livelihood capital, rural governance level, and other conditional variables could be expanded. Thirdly, the digital inclusive finance index developed by Peking University has many innovations and has been widely applied. However, it also has certain limitations, such as the evaluation system not including county-level economic characteristics [69].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and Z.H.; methodology, M.Z.; software, M.Z.; validation, H.Y; formal analysis, H.Y.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, Z.H.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z. and Z.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.H. and M.Z.; visualization, M.Z.; supervision, Z.H.; funding acquisition, M.Z. and Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Project of Soft Science in Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2024C35091), the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 22YJAZH153), the Research Project of the Belt and Road Regional Standardization Research Center of China Jiliang University (Grant No. BRZK07B), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang (Grant No. 2023YW79).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The CPC Central Committee and the State Council jointly issued the guideline on supporting Zhejiang in pursuing high-quality development and building itself into a demonstration zone for common prosperity. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-06/10/content_5616833.htm (accessed on 10 June 2021). |

| 2 | The General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council, China’s Cabinet, have jointly issued a Guiding Opinions on Strengthening and Improving Rural Governance, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-06/23Content_5402625.htm (accessed on 23 June 2019). |

References

- Yang, F. How does digital inclusive finance affect the common prosperity of urban and rural areas? J. Northwest Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 60, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z. Population aging, social security expenditure, and the income gap between urban and rural areas: Analysis from the perspective of common prosperity. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2023, 42, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Hua, X. Research on the path of educational digital transformation to promote educational equity between urban and rural areas. J. Natl. Acad. Educ. Adm. 2023, 25, 37–46+95. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. The realistic challenges and realization paths of rural residents and rural areas sharing common prosperity from the perspective of the urban-rural gap. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2023, 11, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- CGAP. Digital Financial Inclusion: Implications for Customers, Regulators, Supervisors, and Standard-Setting Bodies. Available online: https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/digital-financial-inclusion (accessed on 1 February 2015).

- Li, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, X.; You, J. Transitioning to low-carbon agriculture: The non-linear role of digital inclusive finance in China’s agricultural carbon emissions. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zeng, L. Analysis of the impact and mechanism of digital finance development on regional new quality productive forces. Financ. Econ. 2024, 8, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Cai, T. Digital financial inclusion, industrial structure upgrading, and common prosperity. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2024, 45, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, X.; Li, J. Can digital inclusive finance promote common prosperity? An empirical study based on micro household data. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 48, 4–17+123. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrakis, Y.; Collins, L. Crowdfunding: A New Innovative Model of Providing Funding to Projects and Businesses. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2395226 (accessed on 14 February 2014).

- Zhang, X.; Shi, B.; Zhen, J. A study on the mechanism of digital inclusive finance for common prosperity in high-quality development. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 38, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, M. On the impact of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity—Empirical research based on spatial measurement. Theory Pract. Finance Econ. 2024, 45, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, Y. Digital financial inclusion, non-farm employment, and common prosperity. Wuhan Finance 2023, 43, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. Digital inclusive finance, high-quality development of agriculture and rural areas, and common prosperity of farmers. China Bus. Market 2023, 37, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Shi, W. A study on the impact and mechanism of digital financial inclusion on common prosperity. Econ. Surv. 2023, 40, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Li, B. Effect and mechanism of digital financial inclusion in promoting common prosperity based on prefecture-level city panel data. J. North. Minzu. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 35, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Luo, M. The impact of digital technology on farmers’ common prosperity: “divide” or “bridge”? J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 43, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Yao, R. Possibility and limit of farmers’ cooperatives empowering smallholders to increase their income: Insights from getting rid of poverty to becoming rich. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 23, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, H. An exploration of the path of smallholders towards common prosperity under the perspective of big food: Based on the advantageous perspective. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Farmers’ Digital Literacy Property Income and Common Prosperity. J. Minzu. Univ. China (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, T.; Huo, Z.; Wan, P. A study of the promotion mechanism of digital inclusive finance for the common prosperity of Chinese rural households. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1301632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z. The impacts of digital inclusive finance on rural household income from the perspective of common prosperity: Evidence from the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River Basin. Res. Agric. Mod. 2022, 43, 971–983. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H. Digital financial inclusion, factor structure mismatch and common prosperity. J. Technol. Econ. Manag. 2023, 5, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X. Research on the impact of digital financial inclusion on common prosperity—Empirical evidence from prefecture-level cities. Rev. Inv Stud. 2023, 42, 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, W. Micro evidence of digital inclusive finance in promoting common prosperity—Study from the perspective of subitem income at the community level. J. Wuhan Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 76, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Yu, G.; Wang, D. Can. digital inclusive finance promote common prosperity? Financ. Forum 2023, 28, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Deng, W. How does digital inclusive finance affect households’ access to formal credit? Evidence from CHFS. Mod. Econ. Sci. 2020, 42, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, N. Digital inclusive finance, digital divide, and common prosperity—A perspective of new structural economics. J. Shanghai Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 39, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J. Digital inclusive finance, circulation of innovative elements, and common prosperity. J. Technol. Econ. Manag. 2023, 8, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R.; Li, C. The realization of common prosperity: An investigation based on the “three-wheel drive” of market, government, and society. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 43, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. Research on changes of livelihood capabilities of rural households encountered by land acquisition: Based on improvement of sustainable livelihood approach. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Wu, J. Research on the farmers’ livelihood effect of rural tourism development in old revolutionary areas under the goal of common prosperity. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ren, J. Common prosperity: Theoretical connotation and policy agenda. CASS J. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 13–25+159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Dong, J.; Jiang, S. Digital financial development and inefficient investment: A study based on the dual perspectives of resource and governance effects. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Action Plan for Creating a High-Quality Rural Revitalization Demonstration Province and Promoting the Construction of Demonstration Areas for Common Prosperity (2021–2025). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2021/202109/202112/t20211207_6384015.htm?eqid=c2947e3500487a5e000000036457aa0e (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Mao, K.; Kong, X. The general status and the trend in future of agriculture modernization in China. Reform. 2012, 10, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Hu, L. The achievements and interpretations of the high-quality agricultural development in China since the 18th national congress of the communist party of China. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2023, 1, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, R.; She, S. Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Chinese-style Agriculture Modernization and the Mechanism of Action. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, F. Study on the influence of new quality agricultural productive processes on agricultural modernization development. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, B. Research on China rural governance evaluation and its influence mechanism. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2024, 3, 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Ding, S.; Chen, Y. Study on dynamics of rural household livelihood strategy and its influencing factors: Based on CFPS micro data. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2020, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Ding, S. An analysis of optimal livelihood strategy selection of farmers in mountainous areas: Based on a survey of farmers in southwest Yunnan. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2014, 33, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Hu, J.; An, K. Analysis of the choice of livelihood strategies of peasant households who rent out the farmland and the influencing factors: Based on CFPS data. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 49–58+111. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Jia, L. Configurational perspective and qualitative comparative analysis: The new way of management research. J. Manag. World 2017, 33, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, P. The formation, characteristics, and practicalities of urban community governance: A qualitative comparative study based on 56 cases. Gov. Stud. 2022, 38, 93–104+127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, J. What kind of ecosystem for doing business will contribute to city-level high entrepreneurial activity? A research based on institutional configurations. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yuan, Y. Research on the configuration path of manufacturing intelligence driven by business environment and ecology. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2024, 4, 746–756. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Competition of bank and common prosperity of rural households: Based on the perspectives of absolute income and relative income. J. Econ. Res. 2023, 58, 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y.; Wei, X. How does the marketization of innovation factors promote common prosperity? From the perspective of urban-rural income gap. Sci. Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Lin, W. Cash transfer policies and promoting common prosperity for low-income rural households. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 23, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.; Wu, H.; Peng, Y. Research on the impact of rural mobility on the common prosperity of farmers. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Pln. 2023, 44, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Measurement of common prosperity of Chinese rural households using graded response models: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z. Study and implication of China’s balanced development: Comprehensive analysis based on Tsinghua China balanced development index. J. Manag. World 2019, 35, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Li, D.; Luo, B. The promotion of smallholders’ involvement in modern agricultural development empowered by digital technology: Research based on microdata of Chinese smallholders. J. Jinan (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 45, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, D. Mechanism analysis and empirical test of the influence of modern agricultural management system on farmers’ income. J. Lanzhou Acad. 2023, 44, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, R.; Tan, Y. Innovative production and marketing systems of agricultural products: Promoting the organic connection between small farmers and modern agricultural development. Issues Agric. Econ. 2024, 2, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Fang, Q. Effective rural governance driving common prosperity: Value implication, internal logic and practical approach. J. Chongqing Univ. Tech. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 36, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Walelign, S.Z.; Pouliot, M.; Larsen, H.O. Combining household income and asset data to identify livelihood strategies and their dynamics. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Zhang, M. Multidimensional deprivation and subgroup heterogeneity of rural households in China: Empirical evidence from latent variable estimation methods. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 975–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.J.; Johnson, M.D. Towards a configural theory of job demands and resources. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 66, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Du, H. Study on the configuration path of the improvement of farmers’ manure resource utilization behavior. Arid. Land. Resour. Environ. 2024, 38, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Research on the mechanism of digital inclusive finance promoting rural revitalization and development. Mod. Econ. Res. 2022, 6, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Peng, Y.; Meng, Q. Digital inclusive finance, entrepreneurial activity and common wealth—An empirical study based on inter-provincial panel data in China. Soft Sci. 2023, 37, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Stimulate Endogenous Order: The path optimization of digital inclusive finance embedded in rural governance. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2021, 41, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in Management and organization research: Position, tactics, and directions. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 9, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 1974, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, F. Research on influencing factors and configuration path of high-quality construction of digital countryside—Based on clear-set qualitative comparative analysis of the 37 Cases. World Agric. 2024, 46, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Yu, W. Can insurance allocation promote common prosperity—Empirical analysis based on 1609 survey data of farmers. J. Financ. Dev. Res. 2022, 41, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).