Digital Inclusive Finance, Household Livelihood, and Common Prosperity Among Chinese Farmers: A Configuration Analysis Based on Sustainable Livelihood Framework and Farmer Surveys in Zhejiang Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Relationship Between Family Livelihood and Common Prosperity of Farmers

2.2. The Relationship Between Digital Inclusive Finance and the Common Prosperity of Farmers

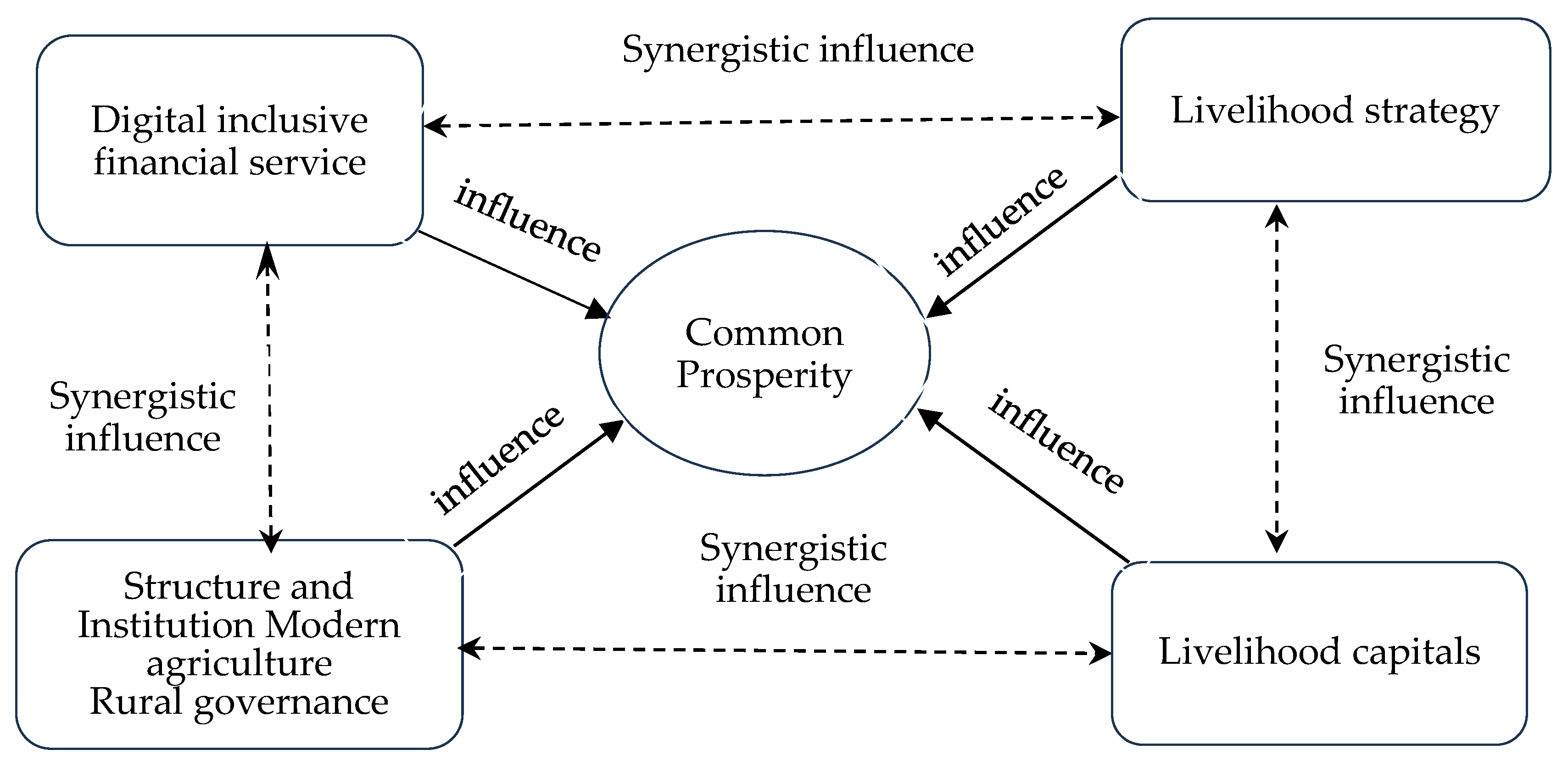

2.3. A Configuration Analysis Framework Based on a Sustainable Livelihood Framework

- Achieving common prosperity for all is a long-term goal proposed by the Chinese government. The official definition of common prosperity encompasses a living state of prosperity, spiritual confidence, and self-improvement; a livable and business-friendly environment; social harmony; and universal public services, all attainable through hard work and mutual assistance1. Yu and Ren argue that common prosperity is about compensating for and correcting the inequalities caused by institutional factors [33], ensuring that everyone has the opportunity and ability to equally participate in high-quality economic and social development, and to share the benefits.

- For farmers, common prosperity encompasses two levels: sharing and prosperity. The sharing level emphasizes fairness and reflects the breadth of common prosperity’s coverage. In contrast, the prosperity level focuses on efficiency, which includes material and spiritual common prosperity. Therefore, common prosperity is seen as a positive and multidimensional livelihood outcome.

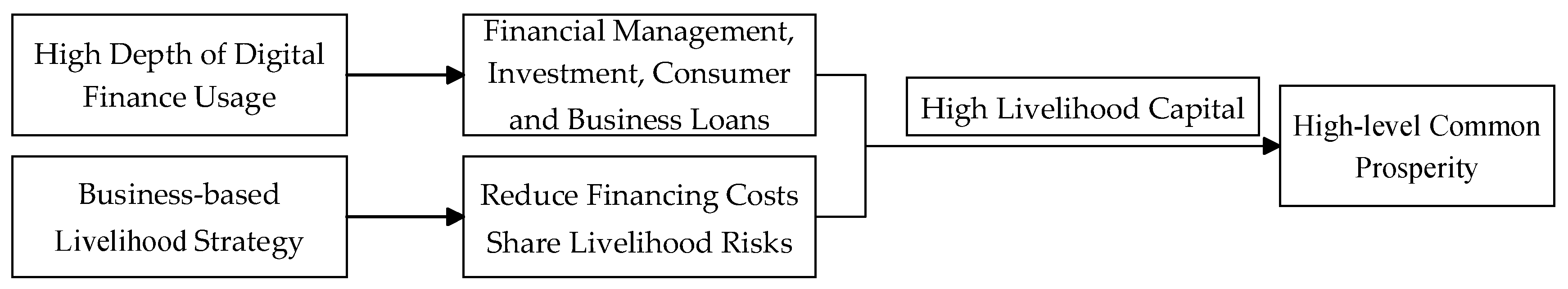

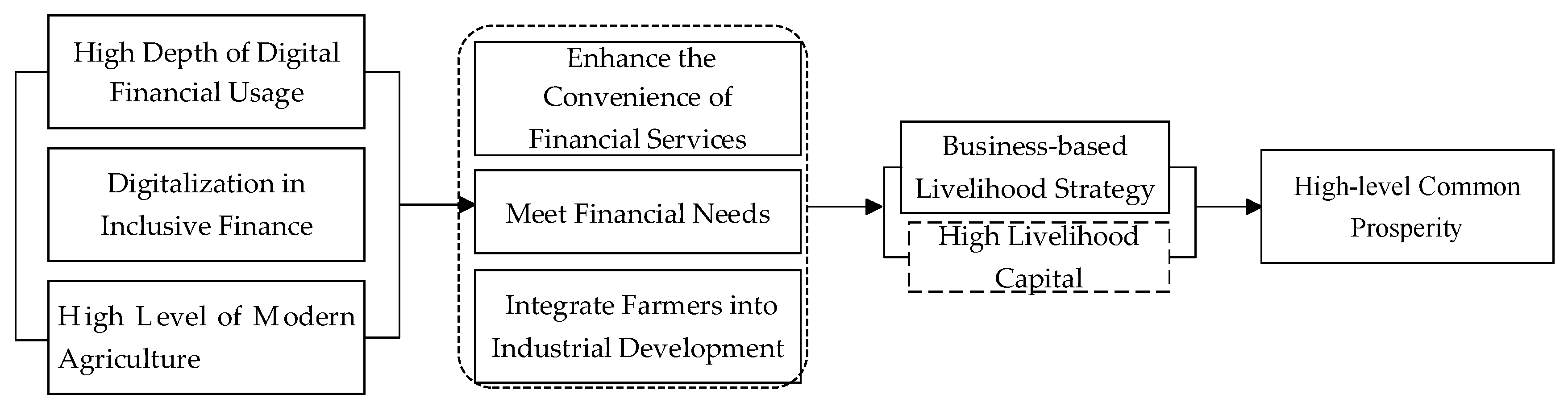

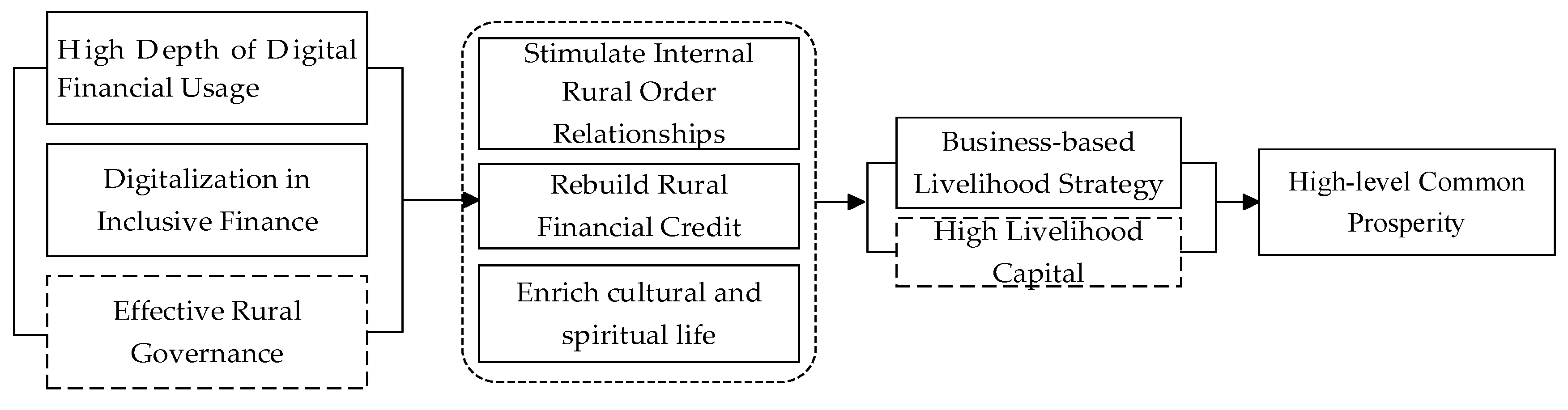

- Public service conditions are an important factor restricting the livelihood development of farmers [31], and digital inclusive finance is an important rural public service infrastructure, which plays an important supporting role in rural revitalization and common prosperity of rural farmers. This article employs the “Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index” (PKU-DFIIC) data developed by the Peking University Digital Finance Research Center. This dataset includes county-level digital inclusive finance indexes, along with the following three sub-dimensions: coverage breadth, usage depth, and degree of digitalization. The coverage breadth refers to the number of electronic accounts, including Internet payment accounts and the number of bank cards linked to them [34]. The usage depth reflects the quantity and activity of digital financial services, encompassing payments, monetary funds, credit, insurance, investment, and credit services, represented by a total of 21 indicators. The degree of digitization indicates the convenience, low cost, and trustworthiness of digital financial services, measured by the proportion of mobile payments, QR code payments, and Huabei payments, totaling 10 indicators. Digital inclusive financial services can influence the common prosperity of farmers by enhancing their financial literacy and increasing their property income. For farmers engaged in business-based livelihood strategies, the development of digital inclusive finance can alleviate their financing constraints. In addition, digital inclusive financial services can be integrated with structures, institutions, and livelihood strategies to influence the common prosperity of farmers.

- As an external factor in the SLF, structures and institutions refer to policy and institutional factors that can impact farmers’ livelihoods, including government investments and community governance. In the process of demonstrating Zhejiang Province’s high-quality creation of a rural revitalization project and promoting the demonstration areas for common prosperity, the development of modern agriculture and innovative rural governance are important focal points [35]. Therefore, this study incorporates county-level indicators of modern agricultural development and county-level rural governance to examine the combined effect of structural and institutional factors in promoting farmers’ common prosperity through digital inclusive finance.

- The characteristics of modern agriculture are reflected in its digital, technological, mechanized, green, and intensive development [36,37]. Evaluation indicators typically include digital modernization [38], production modernization, business modernization, and industrial modernization [39], among others. Building on this foundation, this article examines modern agriculture from the perspectives of production, supply, and sales. The rapid advancement of modern agriculture can encourage farmers to engage in production, supply chains, and other related activities, enabling them to earn labor remuneration or income from agricultural product sales, thus increasing their household income. Simultaneously, the development of modern agriculture may also collaborate with digital financial services and rural governance to foster common prosperity for farmers.

- Rural governance refers to the management of social and economic issues in rural areas, including public safety, healthcare, social security, cultural education, and conflicts of interest. This is achieved through methods such as autonomy, rule of law, and moral governance, with the aim of promoting fairness, vitality, harmony, and order in rural society [40]. From a policy perspective2, it emphasizes a governance system that blends autonomy, rule of law, and moral governance under the leadership of Party organizations, outlining the goals and tasks necessary to enhance rural public services, public management, and the guarantee of public safety. The level of rural governance encompasses governance methods, processes, and effectiveness.

- This article utilizes the digital rural governance index to reflect modern governance approaches, while the urban–rural income gap serves as an indicator of governance effectiveness. Effective rural governance can facilitate farmers’ participation in social governance, enhance their access to social security—in areas such as education, healthcare, and elderly care—and improve the ecological environment of rural regions, thereby increasing their sense of well-being and happiness. In addition, rural governance may synergize with the development of digital finance and modern agriculture. It is important to note that rural governance and household livelihood strategies can lead to different livelihood outcomes.

- As a core element of the SLF, livelihood capital refers to the assets and resources that households possess, including physical capital, human capital, social capital, and financial capital. On one hand, the advancement of external digital inclusive financial services, along with the enhancement of rural governance and the rapid development of modern agriculture, can assist farmers in improving their livelihood capital. On the other hand, livelihood capital itself can also independently promote common prosperity among farmers. Advantages in livelihood capital contribute to common prosperity. Furthermore, livelihood capital may also combine with three external conditions to exert its influence. Even without an advantage in livelihood capital, high levels of digital inclusive financial services, favorable structural and institutional conditions, or a synergistic configuration of these factors can also help households to achieve positive common prosperity results.

- Livelihood strategies are different combinations of livelihood activities adopted to achieve specific livelihood goals [41]. The main livelihood strategies of Chinese farmers include agricultural livelihood, part-time livelihood [42], non-agricultural livelihood [43], and migrant livelihood [44]. Choosing different livelihood strategies is not only influenced by the accumulation of livelihood capital, but also constrained by external factors such as structure, system, and digital inclusive services. Meanwhile, different livelihood strategies can directly lead to different levels of common prosperity. The combination of different livelihood strategies with external factors such as structure, system, and digital inclusive services will also produce different results of common prosperity.

3. Research Methods, Data, and Calibration

3.1. Qualitative Comparative Analysis Method

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Variable Setting

3.3.1. Result Variables

3.3.2. Conditional Variables

- ①

- County-level development of inclusive digital finance.

- ②

- Modern agricultural level in county areas.

- ③

- County-level rural governance.

- ④

- Household livelihood capital.

- ⑤

- Household livelihood strategies.

3.4. Calibration

4. Empirical Result Analysis

4.1. Univariate Necessity Analysis

4.2. Conditional Configuration Analysis

4.2.1. Analysis of the Configuration Path for Generating High-Level Common Prosperity Results

4.2.2. Analysis of Configuration Paths for Generating Non-High Common Prosperity Results

4.3. Robustness Test

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The CPC Central Committee and the State Council jointly issued the guideline on supporting Zhejiang in pursuing high-quality development and building itself into a demonstration zone for common prosperity. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-06/10/content_5616833.htm (accessed on 10 June 2021). |

| 2 | The General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council, China’s Cabinet, have jointly issued a Guiding Opinions on Strengthening and Improving Rural Governance, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-06/23Content_5402625.htm (accessed on 23 June 2019). |

References

- Yang, F. How does digital inclusive finance affect the common prosperity of urban and rural areas? J. Northwest Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 60, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z. Population aging, social security expenditure, and the income gap between urban and rural areas: Analysis from the perspective of common prosperity. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2023, 42, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Hua, X. Research on the path of educational digital transformation to promote educational equity between urban and rural areas. J. Natl. Acad. Educ. Adm. 2023, 25, 37–46+95. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. The realistic challenges and realization paths of rural residents and rural areas sharing common prosperity from the perspective of the urban-rural gap. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2023, 11, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- CGAP. Digital Financial Inclusion: Implications for Customers, Regulators, Supervisors, and Standard-Setting Bodies. Available online: https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/digital-financial-inclusion (accessed on 1 February 2015).

- Li, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, X.; You, J. Transitioning to low-carbon agriculture: The non-linear role of digital inclusive finance in China’s agricultural carbon emissions. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zeng, L. Analysis of the impact and mechanism of digital finance development on regional new quality productive forces. Financ. Econ. 2024, 8, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Cai, T. Digital financial inclusion, industrial structure upgrading, and common prosperity. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2024, 45, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, X.; Li, J. Can digital inclusive finance promote common prosperity? An empirical study based on micro household data. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 48, 4–17+123. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrakis, Y.; Collins, L. Crowdfunding: A New Innovative Model of Providing Funding to Projects and Businesses. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2395226 (accessed on 14 February 2014).

- Zhang, X.; Shi, B.; Zhen, J. A study on the mechanism of digital inclusive finance for common prosperity in high-quality development. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 38, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, M. On the impact of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity—Empirical research based on spatial measurement. Theory Pract. Finance Econ. 2024, 45, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, Y. Digital financial inclusion, non-farm employment, and common prosperity. Wuhan Finance 2023, 43, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. Digital inclusive finance, high-quality development of agriculture and rural areas, and common prosperity of farmers. China Bus. Market 2023, 37, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Shi, W. A study on the impact and mechanism of digital financial inclusion on common prosperity. Econ. Surv. 2023, 40, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Li, B. Effect and mechanism of digital financial inclusion in promoting common prosperity based on prefecture-level city panel data. J. North. Minzu. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 35, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Luo, M. The impact of digital technology on farmers’ common prosperity: “divide” or “bridge”? J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 43, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Yao, R. Possibility and limit of farmers’ cooperatives empowering smallholders to increase their income: Insights from getting rid of poverty to becoming rich. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 23, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, H. An exploration of the path of smallholders towards common prosperity under the perspective of big food: Based on the advantageous perspective. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Farmers’ Digital Literacy Property Income and Common Prosperity. J. Minzu. Univ. China (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, T.; Huo, Z.; Wan, P. A study of the promotion mechanism of digital inclusive finance for the common prosperity of Chinese rural households. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1301632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z. The impacts of digital inclusive finance on rural household income from the perspective of common prosperity: Evidence from the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River Basin. Res. Agric. Mod. 2022, 43, 971–983. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H. Digital financial inclusion, factor structure mismatch and common prosperity. J. Technol. Econ. Manag. 2023, 5, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X. Research on the impact of digital financial inclusion on common prosperity—Empirical evidence from prefecture-level cities. Rev. Inv Stud. 2023, 42, 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, W. Micro evidence of digital inclusive finance in promoting common prosperity—Study from the perspective of subitem income at the community level. J. Wuhan Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 76, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Yu, G.; Wang, D. Can. digital inclusive finance promote common prosperity? Financ. Forum 2023, 28, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Deng, W. How does digital inclusive finance affect households’ access to formal credit? Evidence from CHFS. Mod. Econ. Sci. 2020, 42, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, N. Digital inclusive finance, digital divide, and common prosperity—A perspective of new structural economics. J. Shanghai Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 39, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J. Digital inclusive finance, circulation of innovative elements, and common prosperity. J. Technol. Econ. Manag. 2023, 8, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R.; Li, C. The realization of common prosperity: An investigation based on the “three-wheel drive” of market, government, and society. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 43, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. Research on changes of livelihood capabilities of rural households encountered by land acquisition: Based on improvement of sustainable livelihood approach. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Wu, J. Research on the farmers’ livelihood effect of rural tourism development in old revolutionary areas under the goal of common prosperity. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ren, J. Common prosperity: Theoretical connotation and policy agenda. CASS J. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 13–25+159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Dong, J.; Jiang, S. Digital financial development and inefficient investment: A study based on the dual perspectives of resource and governance effects. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Action Plan for Creating a High-Quality Rural Revitalization Demonstration Province and Promoting the Construction of Demonstration Areas for Common Prosperity (2021–2025). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2021/202109/202112/t20211207_6384015.htm?eqid=c2947e3500487a5e000000036457aa0e (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Mao, K.; Kong, X. The general status and the trend in future of agriculture modernization in China. Reform. 2012, 10, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Hu, L. The achievements and interpretations of the high-quality agricultural development in China since the 18th national congress of the communist party of China. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2023, 1, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, R.; She, S. Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Chinese-style Agriculture Modernization and the Mechanism of Action. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, F. Study on the influence of new quality agricultural productive processes on agricultural modernization development. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, B. Research on China rural governance evaluation and its influence mechanism. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2024, 3, 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Ding, S.; Chen, Y. Study on dynamics of rural household livelihood strategy and its influencing factors: Based on CFPS micro data. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2020, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Ding, S. An analysis of optimal livelihood strategy selection of farmers in mountainous areas: Based on a survey of farmers in southwest Yunnan. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2014, 33, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Hu, J.; An, K. Analysis of the choice of livelihood strategies of peasant households who rent out the farmland and the influencing factors: Based on CFPS data. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 49–58+111. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Jia, L. Configurational perspective and qualitative comparative analysis: The new way of management research. J. Manag. World 2017, 33, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, P. The formation, characteristics, and practicalities of urban community governance: A qualitative comparative study based on 56 cases. Gov. Stud. 2022, 38, 93–104+127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, J. What kind of ecosystem for doing business will contribute to city-level high entrepreneurial activity? A research based on institutional configurations. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yuan, Y. Research on the configuration path of manufacturing intelligence driven by business environment and ecology. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2024, 4, 746–756. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Competition of bank and common prosperity of rural households: Based on the perspectives of absolute income and relative income. J. Econ. Res. 2023, 58, 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y.; Wei, X. How does the marketization of innovation factors promote common prosperity? From the perspective of urban-rural income gap. Sci. Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Lin, W. Cash transfer policies and promoting common prosperity for low-income rural households. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 23, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.; Wu, H.; Peng, Y. Research on the impact of rural mobility on the common prosperity of farmers. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Pln. 2023, 44, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Measurement of common prosperity of Chinese rural households using graded response models: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z. Study and implication of China’s balanced development: Comprehensive analysis based on Tsinghua China balanced development index. J. Manag. World 2019, 35, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Li, D.; Luo, B. The promotion of smallholders’ involvement in modern agricultural development empowered by digital technology: Research based on microdata of Chinese smallholders. J. Jinan (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 45, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, D. Mechanism analysis and empirical test of the influence of modern agricultural management system on farmers’ income. J. Lanzhou Acad. 2023, 44, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, R.; Tan, Y. Innovative production and marketing systems of agricultural products: Promoting the organic connection between small farmers and modern agricultural development. Issues Agric. Econ. 2024, 2, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Fang, Q. Effective rural governance driving common prosperity: Value implication, internal logic and practical approach. J. Chongqing Univ. Tech. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 36, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Walelign, S.Z.; Pouliot, M.; Larsen, H.O. Combining household income and asset data to identify livelihood strategies and their dynamics. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Zhang, M. Multidimensional deprivation and subgroup heterogeneity of rural households in China: Empirical evidence from latent variable estimation methods. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 975–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.J.; Johnson, M.D. Towards a configural theory of job demands and resources. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 66, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Du, H. Study on the configuration path of the improvement of farmers’ manure resource utilization behavior. Arid. Land. Resour. Environ. 2024, 38, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Research on the mechanism of digital inclusive finance promoting rural revitalization and development. Mod. Econ. Res. 2022, 6, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Peng, Y.; Meng, Q. Digital inclusive finance, entrepreneurial activity and common wealth—An empirical study based on inter-provincial panel data in China. Soft Sci. 2023, 37, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Stimulate Endogenous Order: The path optimization of digital inclusive finance embedded in rural governance. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2021, 41, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in Management and organization research: Position, tactics, and directions. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 9, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 1974, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, F. Research on influencing factors and configuration path of high-quality construction of digital countryside—Based on clear-set qualitative comparative analysis of the 37 Cases. World Agric. 2024, 46, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Yu, W. Can insurance allocation promote common prosperity—Empirical analysis based on 1609 survey data of farmers. J. Financ. Dev. Res. 2022, 41, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Measurement Index | Value Range | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affluence | Household per capita income (y1) | 1~5 | 3.490 (1.220) |

| Urban–rural income gap (y2) | 1~5 | 3.000 (1.419) | |

| Income satisfaction (y3) | 1~5 | 3.452 (0.812) | |

| Sharing | Satisfaction degree of compulsory education (y4) | 1~5 | 3.657 (0.914) |

| Evaluation of urban–rural education gap (y5) | 1~5 | 3.274 (1.016) | |

| Evaluation of self-health (y6) | 1~5 | 3.874 (0.723) | |

| Satisfaction with reimbursement of medical insurance (y7) | 1~5 | 3.704 (0.820) | |

| Satisfaction with basic endowment insurance (y8) | 1~5 | 3.737 (0. 819) | |

| Sustainability | Satisfaction with village waste treatment (y9) | 1~5 | 3.814 (0.830) |

| Satisfaction with village security (y10) | 1~5 | 4.009 (0.690) | |

| Satisfaction with sanitary toilet construction (y11) | 1~5 | 3.762 (0.798) | |

| Satisfaction with cultural and entertainment facilities (y12) | 1~5 | 3.659 (0.861) | |

| Satisfaction with medical convenience (y13) | 1~5 | 3.837 (0.812) | |

| Satisfaction with village committee and affairs (y14) | 1~5 | 3.773 (0.831) |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Common Prosperity (Y) | Using the graded item response model for estimation, normalization is applied |

| Conditional variable 1 (Digital inclusive fi nance) | Digital inclusive finance level (X1) | Normalization of the digital inclusive finance indexes |

| Coverage breadth (X2) | Normalization of the index of coverage breadth | |

| Depth of use (X3) | Normalization of the index of use depth | |

| Digitalization (X4) | Normalization of index of digitization | |

| Conditional variable 2 (Modern agricultural level) Conditional variable 3 (Rural governance level) | Digital production (X5) | Peking University Digital Rural Index, calculated using the entropy method and normalized |

| Digital supply chain (X6) | ||

| Digital Marketing (X7) | ||

| Digitalization of rural governance (X8) | Peking University Digital Rural Index | |

| Income gap between urban and rural areas (X9) | County statistical data, calculated using the entropy method and normalized | |

| Conditional variable 4 (Livelihood capital) | Total household income (X10) | Entropy method, normalization processing |

| Housing area (X11) | ||

| Closely connected families (X12) | ||

| Family members including civil servants, employees of public institutions, teachers, and doctors (X13) | ||

| Conditional variable 5 (Livelihood strategy) | Agricultural livelihood strategy (X14) | The proportion of agricultural income to total income is greater than or equal to 50%, with a value of 1, otherwise, it is 0 |

| Livelihood strategy for migrant workers (X15) | If the proportion of migrant income to total income is greater than or equal to 50%, the value is 1, otherwise it is 0 | |

| Business-based livelihood strategy (X16) | The proportion of business revenue to total revenue is greater than or equal to 50%, with a value of 1, otherwise, it is 0 |

| Variable Name | Calibration Anchors | Descriptive Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Non-Membership | Crossover Point | Full Membership | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Common prosperity | 0.444 | 0.604 | 0.764 | 0.604 | 0.160 | 0 | 1 |

| Digital inclusive finance | 0.005 | 0.253 | 0.501 | 0.253 | 0.248 | 0 | 1 |

| Coverage breadth | 0.015 | 0.323 | 0.631 | 0.323 | 0.308 | 0 | 1 |

| Depth of use | 0.022 | 0.257 | 0.492 | 0.257 | 0.235 | 0 | 1 |

| Digitalization | 0.494 | 0.740 | 0.986 | 0.740 | 0.246 | 0 | 1 |

| Modern agriculture | 0.179 | 0.473 | 0.767 | 0.473 | 0.294 | 0 | 1 |

| Rural governance | 0.322 | 0.566 | 0.810 | 0.566 | 0.244 | 0 | 1 |

| Livelihood capital | 0.024 | 0.236 | 0.448 | 0.236 | 0.212 | 0 | 1 |

| Antecedent Variable | Common Prosperity | ~Common Prosperity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| Digital inclusive finance | 0.529 | 0.637 | 0.428 | 0.636 |

| ~Digital inclusive finance | 0.698 | 0.497 | 0.756 | 0.665 |

| Coverage breadth | 0.514 | 0.653 | 0.394 | 0.617 |

| ~Coverage breadth | 0.699 | 0.483 | 0.779 | 0.664 |

| Depth of use | 0.768 | 0.581 | 0.727 | 0.679 |

| ~Depth of use | 0.575 | 0.631 | 0.551 | 0.746 |

| Digitalization | 0.258 | 0.611 | 0.173 | 0.506 |

| ~Digitalization | 0.791 | 0.437 | 0.867 | 0.590 |

| Modern agriculture | 0.338 | 0.402 | 0.426 | 0.626 |

| ~Modern agriculture | 0.686 | 0.492 | 0.594 | 0.525 |

| Rural governance | 0.505 | 0.402 | 0.635 | 0.623 |

| ~Rural governance | 0.525 | 0.538 | 0.390 | 0.493 |

| Livelihood capital | 0.932 | 0.485 | 0.866 | 0.557 |

| ~Livelihood capital | 0.149 | 0.473 | 0.200 | 0.783 |

| Agricultural livelihood strategy | 0.039 | 0.643 | 0.033 | 0.671 |

| ~Agricultural livelihood strategy | 0.980 | 0.451 | 0.983 | 0.557 |

| Migrant workers | 0.700 | 0.468 | 0.639 | 0.527 |

| ~Migrant workers | 0.293 | 0.396 | 0.355 | 0.593 |

| Business-based livelihood strategy | 0.180 | 0.420 | 0.211 | 0.608 |

| ~Business-based livelihood strategy | 0.832 | 0.461 | 0.798 | 0.546 |

| Condition | H1 | H2 | H3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital inclusive finance |  |  |  |

| Coverage breadth |  |  |  |

| Depth of use |  |  |  |

| Digitalization |  |  |  |

| Modern agriculture |  |  | |

| Rural governance |  |  |  |

| Livelihood capital |  |  |  |

| Business-based livelihood strategy |  |  |  |

| Agricultural livelihood strategy |  |  |  |

| Consistency | 0.820 | 0.858 | 0.893 |

| Original Coverage | 0.059 | 0.025 | 0.026 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.024 | 0.010 | 0.016 |

| Solution Consistency | 0.812 | ||

| Solution Coverage | 0.288 | ||

or

or  indicates the existence of conditions,

indicates the existence of conditions,  or

or  indicates the absence of conditions;

indicates the absence of conditions;  or

or  indicates the core conditions,

indicates the core conditions,  or

or  indicates the auxiliary conditions, and blank spaces indicate “do not care”.

indicates the auxiliary conditions, and blank spaces indicate “do not care”.| Condition | NH1 | NH2 | NH3 | NH4 | NH5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH3 a | NH3 b | |||||

| Digital inclusive finance |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Coverage breadth |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Depth of use |  |  |  | |||

| Digitalization |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Modern agriculture |  |  |  |  | ||

| Rural governance |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Livelihood capital |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Business-based livelihood strategy |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Agricultural livelihood |  |  |  |  | ||

| Consistency | 0.772 | 0.808 | 0.786 | 0.914 | 0.866 | 0.923 |

| Original Coverage | 0.323 | 0.142 | 0.363 | 0.082 | 0.053 | 0.084 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.029 | 0.088 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0 | 0 |

| Solution Consistency | 0.792 | |||||

| Solution Coverage | 0.569 | |||||

or

or  indicates the existence of conditions,

indicates the existence of conditions,  or

or  indicates the absence of conditions;

indicates the absence of conditions;  or

or  indicates the core conditions,

indicates the core conditions,  or

or  indicates the auxiliary conditions, and blank spaces indicate “do not care”.

indicates the auxiliary conditions, and blank spaces indicate “do not care”.| Condition | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital inclusive finance |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Coverage breadth |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Depth of use |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Digitalization |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Modern agriculture |  |  |  |  | ||

| Rural governance |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Livelihood capital |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Business-based livelihood strategy |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Agricultural livelihood strategy |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Compared configurations | H2 | H3 | H4 | H2 | H3 | H4 |

or

or  indicates the existence of conditions,

indicates the existence of conditions,  or

or  indicates the absence of conditions;

indicates the absence of conditions;  or

or  indicates the core conditions,

indicates the core conditions,  or

or  indicates the auxiliary conditions, and blank spaces indicate “do not care”.

indicates the auxiliary conditions, and blank spaces indicate “do not care”.| Matching | Pseudo—R2 | Mean Bias(%) | B Value | R Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched | 0.076 | 17.8 | 67.7 * | 0.42 * |

| Matched | 0.012 | 9.1 | 25.6 * | 0.61 |

| Matching Method | Treatment Group | Reference Group | ATT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest-neighbor matching (n = 1) | 0.621 | 0.552 | 0.069 *** (0.021) |

| Kernel matching (bwidth = 0.05) | 0.621 | 0.560 | 0.062 *** (0.018) |

| Radius matching Caliper (0.05) | 0.621 | 0.558 | 0.064 *** (0.018) |

| Mean value | 0.621 | 0.557 | 0.065 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Huo, Z.; Yu, H. Digital Inclusive Finance, Household Livelihood, and Common Prosperity Among Chinese Farmers: A Configuration Analysis Based on Sustainable Livelihood Framework and Farmer Surveys in Zhejiang Province. Systems 2025, 13, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050345

Zhang M, Huo Z, Yu H. Digital Inclusive Finance, Household Livelihood, and Common Prosperity Among Chinese Farmers: A Configuration Analysis Based on Sustainable Livelihood Framework and Farmer Surveys in Zhejiang Province. Systems. 2025; 13(5):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050345

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mei, Zenghui Huo, and Huijie Yu. 2025. "Digital Inclusive Finance, Household Livelihood, and Common Prosperity Among Chinese Farmers: A Configuration Analysis Based on Sustainable Livelihood Framework and Farmer Surveys in Zhejiang Province" Systems 13, no. 5: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050345

APA StyleZhang, M., Huo, Z., & Yu, H. (2025). Digital Inclusive Finance, Household Livelihood, and Common Prosperity Among Chinese Farmers: A Configuration Analysis Based on Sustainable Livelihood Framework and Farmer Surveys in Zhejiang Province. Systems, 13(5), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050345