Abstract

This study examines the role of Digital Twin technologies in advancing Environmental, Social, and Governance performance within multinational corporations. Grounded in socio-technical systems theory and stakeholder theory, the research investigates how digital twins facilitate the integration of organizational capabilities with external accountability mechanisms. A multi-method research design is employed, comprising in-depth case studies, capital market event analysis, and machine learning-assisted regression to capture both qualitative and empirical insights. Case evidence from Siemens, Unilever, Tesla, and BP reveals that DT adoption is associated with measurable ESG gains, including reduced emissions, improved safety, enhanced supplier compliance, and accelerated reporting cycles. Event study findings show statistically significant abnormal returns following ESG-oriented DT announcements, while regression analysis confirms a positive association between DT adoption and ESG performance. Governance structures are explored as potential moderators of this relationship. The findings underscore DTs as strategic enablers of ESG value creation, beyond their technical utility. By enhancing transparency, auditability, and stakeholder trust, DTs contribute to both internal transformation and external legitimacy. This research advances the discourse on ESG digitalization and offers actionable implications for corporate leaders and policymakers seeking to foster sustainable, technology-driven governance in complex global value chains. However, because the quantitative component relies on cross-sectional data, the relationships identified should be interpreted as associations rather than definitive causal effects.

1. Introduction

Environmental, Social, and Governance (hereinafter ESG) frameworks have evolved from voluntary compliance mechanisms to strategic imperatives for multinational corporations (MNCs), driven by accelerating climate change, geopolitical instability, and rising stakeholder expectations [1,2]. In this context, regulatory advances, particularly the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), have redefined the contours of corporate responsibility [3,4] mandating comprehensive, auditable disclosures of ESG metrics across more than 50,000 firms in the European Union alone [5,6]. This shift presents both an opportunity and a challenge. While ESG strategies are increasingly embedded in corporate agendas, many organizations continue to face fundamental obstacles in operationalizing ESG goals, including fragmented data infrastructures, reactive compliance cultures, and a lack of dynamic tools for monitoring and decision support [7,8], the gap between ESG ambition and ESG execution remains a persistent issue in both research and practice. At the same time, the rapid diffusion of technologies such as artificial intelligence, IoT, and blockchain has prompted calls for digital innovation to improve ESG performance [9,10,11,12]. However, academic research has largely siloed ESG and digitalization into parallel conversations. ESG studies have primarily focused on frameworks, regulatory compliance, and financial materiality, while digital twins (DTs, hereinafter) research has been concentrated in engineering domains, targeting manufacturing efficiency, smart infrastructure, or supply chain automation [13,14,15,16]. What remains underexplored is the strategic intersection between DT technologies and ESG management, particularly in how DTs can act as real-time, data-driven enablers of sustainability reporting, decision-making, and governance transformation.

This study explores how DT technologies enhance ESG performance in multinational corporations by integrating socio-technical systems and stakeholder theories. It investigates (1) the impact of DTs across ESG dimensions, (2) how organizational factors such as ESG maturity and governance influence this impact, and (3) how capital markets react to DT-ESG announcements. Using a multi-method approach, namely, case studies, event study analysis, and machine learning regression, the study tests three hypotheses relating DT adoption to ESG outcomes and investor perception. The research offers both conceptual insights and practical implications for ESG-aligned digital transformation.

The application of DT technology is rapidly evolving across various sectors, yet its integration as an enabler for ESG frameworks remains comparatively underexplored. DTs function as digital replicas of physical entities, processes, or systems, utilizing real-time data to improve operational efficiency. In the context of environmental sustainability, DTs can significantly contribute to minimizing resource consumption and optimizing energy use. For instance, DT technology integrated with predictive maintenance can enhance the performance of renewable energy systems, such as photovoltaic panels, by facilitating early fault detection, thus improving reliability and lifespan. The effective monitoring of volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions in additive manufacturing further demonstrates the utility of DTs in real-time environmental management, showcasing the technology’s potential in minimizing environmental impact while adhering to sustainability standards. Moreover, the synergistic effect of DTs and Building Information Modeling (BIM) is noteworthy in the construction sector, where it significantly supports lifecycle management of buildings aimed at achieving net-zero carbon emissions [16]. By fostering better decision-making and facilitating stakeholder communication, DTs enhance building sustainability, providing a framework that aligns with broader ESG principles. The integration of DT in urban infrastructure, particularly in managing the Water-Energy-Food-Environment (WEFE) nexus, illustrates a holistic approach to resource governance that supports social sustainability [17].

In industrial contexts, the application of DTs in conjunction with advanced data analytics is emerging as a strategy to enhance operational efficiencies within the production lifecycle. DTs can use real-time data to optimize manufacturing processes and support sustainability initiatives by reducing waste and improving energy efficiency, aligning directly with ESG goals [18,19]. Failure to harness these technologies represents a missed opportunity for industries striving to comply with increasing sustainability regulations and investor demands for responsible governance practices [20].

Despite these advancements, the widespread adoption of DT technologies specifically applied for ESG integration remains limited. Industries must adopt these innovative tools systematically to overcome existing barriers to implementation, including technological maturity and stakeholder engagement complexities [21,22]. Additionally, fostering knowledge-sharing initiatives and developing best practices for DT applications related to ESG frameworks will be crucial for driving broader acceptance and integration [23,24,25]. In conclusion, while the potential of DTs as enablers of ESG objectives is recognized, their implementation is still in its early stages across various sectors. A concerted effort towards understanding and deploying these technologies could profoundly influence sustainable practices, ultimately benefiting environmental quality, social equity, and corporate governance.

To understand the role of DT technologies in enhancing ESG performance to create value, this study draws on two interrelated theoretical lenses: socio-technical systems theory and stakeholder theory. These frameworks provide a conceptual foundation for explaining how digital innovations create global value, reshape organizational structures, decision-making processes, and accountability mechanisms in response to both technological capabilities and external stakeholder demand. To synthesize socio-technical systems theory and stakeholder theory, this study conceptualizes Digital Twins as mediating infrastructures that connect internal organizational capabilities (data integration, operational control, ESG governance) with external accountability requirements (regulators, investors, consumers, NGOs). DTs improve ESG outcomes by enabling real-time monitoring, automated disclosure, and enhanced auditability. A visual representation of this conceptual positioning is later presented in Section 4; however, its logic is introduced here to anchor the theoretical argument.

1.1. Socio-Technical Systems Theory

As described by Lyytinen and Newman [26] and reviews in recent literature [27,28,29,30], socio-technical systems (STS) theory posits that organizations are composed of two interdependent subsystems: the technical system, encompassing tools, technologies, and workflows, and the social system, comprising people, culture, roles, and governance. The central argument is that optimal organizational performance can only be achieved through the joint optimization of both subsystems. Technological change, therefore, cannot be treated as a purely operational issue, but must be considered in relation to the social structures and professional competencies that it disrupts and reconfigures [31,32,33].

In the context of ESG reporting, STS theory is especially pertinent. The implementation of technologies such as DTs involves more than system automation; it introduces new decision paradigms, accountability structures, and organizational routines. For instance, DTs allow for real-time ESG data flows, predictive scenario modeling, and automated compliance checks. However, their effective deployment also necessitates the retraining of personnel, creation of new professional roles (such as ESG data analysts, digital compliance officers), and restructuring of interdepartmental collaboration across sustainability, finance, and IT functions.

This dual transformation, technological and organizational, lies at the core of this study’s argument: that DTs are not merely tools for efficiency but architects of ESG-driven transformation, reshaping how firms perceive, measure, and act upon sustainability metrics.

1.2. Stakeholder Theory and ESG Legitimacy

While STS explains the internal dynamics of change, stakeholder theory [34,35,36,37] situates ESG transformation within the external environment. ESG strategies are fundamentally driven by the need to align organizational behavior with the expectations of diverse stakeholders, including regulators, investors, customers, employees, and communities [38,39,40,41]. In this view, ESG reporting serves not only a compliance function but also a legitimization function, enabling firms to justify their social and environmental impact and secure long-term stakeholder trust. Recent studies [42,43] emphasize that stakeholder expectations have evolved from passive information demands to active scrutiny of corporate sustainability performance. Technologies that enhance transparency, verifiability, and accountability are increasingly valued—not only as operational tools but as mechanisms of stakeholder reassurance and reputational capital [44,45,46].

DTs, with their ability to produce traceable, audit-ready ESG data and simulate future sustainability outcomes, align directly with these stakeholder imperatives. They enable firms to move from retrospective disclosure to predictive, scenario-based sustainability planning, which enhances both regulatory compliance and strategic legitimacy [20,25,47].

The study presents a theoretical model positioning DT technologies as mediators between organizational capabilities and stakeholder accountability in ESG performance. From a socio-technical angle, DTs enhance real-time data integration and process transformation; from a stakeholder view, they boost transparency and trust. As boundary-spanning technologies, DTs drive both internal change and external legitimacy. The model also identifies key mediators (like data quality and organizational readiness) and moderators (such as industry context and ESG maturity) that influence DT effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a multi-method research design to examine the strategic contribution of DT technologies to ESG performance in MNCs. The methodological framework integrates three complementary components, namely (1) qualitative case study analysis, (2) event-based capital market evaluation, and (3) quantitative panel regression modeling, thereby ensuring both conceptual richness and empirical robustness. The research design is grounded in the triangulation of secondary data sources, including ESG disclosures, technology implementation reports, financial market data, and third-party sustainability ratings.

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Case Study Analysis

To investigate the role of DT technologies in enhancing ESG performance by creating global value, this study employed a comparative multiple-case study design. The approach is rooted in the principles of qualitative inquiry and theory building through case research [10,11,48,49,50] with an emphasis on extracting nuanced, context-specific insights. This study used in-depth case studies of four MNCs, namely, Siemens, Unilever, Tesla, and BP, to explore how digital twins support ESG objectives. Data were triangulated from ESG reports (2019–2023), whitepapers, technical roadmaps, press releases, and ESG ratings (MSCI, Sustainalytics). In addition to the MSCI World Index, sector-specific benchmark indices were used to better capture systematic variations in returns within individual industries. Expected returns were therefore estimated against the following indices: MSCI World Industrials (manufacturing), MSCI World Energy (oil and gas), MSCI World Consumer Staples (fast-moving consumer goods), and MSCI World Automobiles (electric vehicle and automotive manufacturing). Daily prices for all indices were retrieved from Yahoo Finance. Using sector-aligned benchmarks improves model precision by controlling for heterogeneous risk–return dynamics across industries. Using cross-case synthesis, the analysis identified both common and sector-specific patterns across environmental, social, and governance dimensions. Each firm was analyzed individually, followed by comparative analysis. This design ensured both depth and analytical rigor, revealing digital twins as strategic tools for real-time ESG monitoring, simulation, and compliance.

2.1.2. Event Study Analysis

To empirically assess investor perceptions of DT technology as a strategic enabler of ESG performance, author employed an event study methodology [51,52,53,54]. This method evaluates the abnormal return (AR) in the stock price of a firm surrounding a specific event, in this case, announcements related to DT adoption aimed at enhancing ESG reporting, risk management, or sustainability performance.

Event identification and selection criteria

Event study methodology was employed by utilizing the market model to calculate expected returns. The estimation window included the 120 trading days preceding each event. Cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) were computed over a symmetric ±5-day window to capture immediate and slightly delayed market reactions, while reducing noise from broader macroeconomic movements. Thus, a systematic search of press releases, ESG reports, and financial news databases (Factiva, Bloomberg Terminal) using keywords such as “DT,” “ESG reporting,” “real-time sustainability monitoring,” and “sustainability simulation.” To ensure relevance and significance, selected events met three criteria:

- (1)

- Public announcement of DT adoption was explicitly to ESG objectives such as emissions monitoring, compliance with CSRD, or ethical supply chain management.

- (2)

- The firm is publicly listed and has sufficient stock market data available.

- (3)

- No confounding events, such as earnings releases or mergers, occurred within a 10-day window of the announcement. A relevant example for this includes Siemens’ announcement of its “Sustainability DT” module in 2022 and General Electric’s 2021 launch of a DT framework for decarbonization in heavy industry.

2.1.3. Estimation and Event Windows

The market model was used to estimate normal return, applying the following formula:

where is the return on stock on day , is the market return and is the error term.

Abnormal returns were calculated as:

where is the abnormal return for firm on day , is the actual return, and is the market return proxied by the MSCI World Index. The coefficients and were estimated using OLS over the estimation window.

2.1.4. Sample and Data Source

The study included a set of 30 ESG-active MNCs from sectors such as manufacturing, energy, consumer goods, and transportation. Daily stock return data were sourced Yahoo Finance. Market indices used for benchmarking were sector-specific to control for systemic fluctuations.

2.1.5. Quantitative Modeling Variables

To empirically investigate the impact of DT adoption on corporate ESG performance, the author developed a panel dataset purpose-built for quantitative analysis. This dataset comprises publicly listed MNCs that are among the top ESG performers in their respective sectors, allowing for structured comparison across industries and technological maturity levels. The construction of the dataset relied on sources and methodological rigor for using CSRHub (Est.) and Sustainalytics Risk Ratings which provided comprehensive estimates of ESG-related exposure and performance at the firm level. To harmonize ESG measurement across sectors and providers, a proxy ESG score was constructed by triangulating data from Yahoo Finance, CSRHub (est.), and Sustainalytics risk scores, facilitating the calculation of firm size and economic scope. Annual and sustainability reports, as well as patent filings and technology roadmaps, were examined to verify DT adoption. Only firms with clear, disclosed use of DTs in sustainability-related domains (such as emissions tracking, supply chain simulation, carbon scenario modeling) were marked as adopters. Only companies with documented, operational deployment of DTs in ESG-linked domains were coded as adopters. Corporate governance documentation was reviewed to determine the presence of a dedicated ESG committee at board level, a proxy for internal ESG institutionalization. ISIC Rev. 4 codes were used to classify industry sectors, enabling the implementation of industry-level fixed effects in the econometric model. Thus, each observation in the dataset includes the variables depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

The presentation of the variables.

To ensure sectoral representativeness and analytical clarity, the dataset includes the top 10 ESG-ranked firms within each of the 11 GICS-aligned sectors, as defined by MSCI ESG benchmarks. This cross-sectoral design enables the identification of patterns that transcend industry idiosyncrasies, particularly in relation to ESG innovation and digital capability.

To generalize the findings, a machine learning-supported panel regression analysis was employed. A dataset was constructed from ESG scores and firm-level indicators for a sample of publicly listed firms (n = 110), segmented into two groups as follows: (1) DT adopters: organizations that have publicly disclosed the use of DT technologies for ESG-related activities such as predictive carbon modeling, real-time environmental monitoring, or digital sustainability reporting; (2) non-adopters, the firms that do not exhibit documented implementation of DTs in sustainability contexts, serving as a counterfactual benchmark. This segmentation allows for hypothesis testing regarding the differential ESG outcomes of DT integration.

Two regression models were sequentially estimated. Model 1 examined the direct effects of DT adoption, firm size, and ESG committee presence on normalized ESG performance scores, with industry fixed effects applied via ISIC codes. To deepen this analysis, Model 2 introduced an interaction term between DT adoption and ESG committee presence (DT Adopter × ESG Committee), allowing assessment of whether governance structures condition the impact of digital technologies. Together, these models enable both a baseline and a conditional interpretation of how DT capabilities influence sustainability outcomes in multinational firms.

Variable operationalization

The regression models employed are structured to evaluate the influence of DT adoption on ESG performance, while accounting for firm-level controls and structural differences across industries.

Dependent variable:

The ESG score is normalized to a 0–1 scale to standardize the dependent variable for regression.

Independent variable:

This binary variable captures whether a firm has publicly documented and operationalized DT technologies in domains such as carbon modeling, supply chain simulation, or sustainability monitoring.

Control variables:

Company size, as log-transformed to correct for scale distortion and allow elasticity-based interpretation:

ESG committee, a binary indicator reflecting the presence (1) or absence (0) of a board-level ESG oversight structure.

Industry fixed effects were included to control for sectoral heterogeneity using categorical dummy variables derived from ISIC Rev. 4 codes. Each firm was matched to a four-digit ISIC code representing its primary economic activity. This allows the model to account for time-invariant industry-specific characteristics that may systematically influence ESG practices or digital adoption.

To capture the conditional effect of internal ESG governance on the relationship between DT adoption and ESG performance, a second model introduced an interaction term between DT adoption and ESG committee presence:

This formulation allows for testing whether the presence of a board-level ESG oversight body amplifies the sustainability impact of DT implementation. The interaction term takes the value 1 only when both conditions are met, capturing potential synergistic effects between digital infrastructure and governance capacity. Model 3 was originally designed to test ESG maturity as a moderator of the DT–ESG relationship. However, the ESG Maturity Index contains the ESG score, which is also the dependent variable. Including ESGMI in the regression would therefore induce structural multicollinearity and artificially inflate model fit (pre-tests yielded R2 ≈ 1.00 and unstable coefficients). For this reason, Model 3 was excluded from inferential testing to protect validity. ESGMI is used only for exploratory comparison between firms with high versus low ESG maturity because, in its current form, it cannot serve as an econometric moderator without overlapping with the dependent construct.

ESG maturity index as moderator

To capture organizational ESG readiness, the researcher constructed an ESG Maturity Index (ESGMI) that combines ESG performance, governance structure, and resource capacity:

which is,

Each component serves a distinct conceptual role: ESG score reflects sustainability performance; ESG committee represents internal governance and strategic alignment; firm size reflects implementation capacity and resource mobilization potential. Because ESGMI includes the ESG score—which is also the dependent variable—using it in the regression models would create structural multicollinearity and overfitting. Therefore, ESGMI was not included in the regression models. Instead, ESGMI is used only for exploratory comparison between firms with high versus low ESG maturity. This approach ensures methodological robustness while preserving the theoretical relevance of ESG maturity. Accordingly, the inferential analysis focuses on two regression models: (i) a baseline model testing the direct association between DT adoption and ESG performance, and (ii) an interaction model assessing whether the presence of a board-level ESG committee conditions this association. The descriptive comparison based on ESGMI is revisited in the Section 3 to contextualize differences in technological and governance readiness across firms.

2.2. Methodological Rigor

The study ensured methodological rigor through multiple validation strategies. Construct validity was secured via standardized measures and data triangulation, while internal validity was strengthened through robust case analysis and controlled regressions. External validity was supported by a diverse, global sample of ESG-leading firms. Reliability was maintained with transparent coding and consistent data processing. These measures collectively enhance the study’s credibility and support its findings on DTs’ role in ESG value creation.

2.3. Validity and Reliability

This study ensured rigor through a multi-method design supported by multiple layers of validity and reliability. Two regression models tested both direct and moderated effects of DT adoption on ESG performance. Construct validity was achieved via standardized indicators (ESG scores, ISIC codes) and triangulated sources. Internal validity was ensured through cross-case synthesis, temporal scoping (2019–2023), robustness checks (±3/5/7 days), and control variables (firm size, ESG committee, industry effects). An interaction term (DT × ESG Committee) captured the conditional effect of internal governance. ESGMI was used only descriptively due to multicollinearity with the dependent variable. External validity was enhanced by including ESG-leading MNCs across 11 sectors. Reliability was upheld through transparent coding, Python-based analysis, and consistent data transformations.

To conclude the methodological section, the following hypotheses were tested in the empirical stage of the research:

H1:

Digital Twin (DT) adoption is positively associated with corporate ESG performance in multinational corporations.

H2:

The presence of a board-level ESG committee amplifies the association between DT adoption and ESG performance.

H3:

Firms with higher ESG maturity exhibit stronger ESG performance effects from DT adoption compared with firms at lower levels of maturity.

Although H1 and H2 were tested through the panel regression models, H3 could not be estimated because the ESG Maturity Index contains the ESG score (the dependent variable). For this reason, H3 was assessed descriptively rather than inferentially.

3. Results

The results are organized around the research questions, following the multi-method design outlined in the methodology. The triangulated evidence from qualitative case studies, event-based capital market analysis, and quantitative regression modeling provides a cohesive understanding of how DT technologies contribute to ESG performance in multinational corporations.

3.1. Case Study Analysis Results

In order to systematically assess the contributions of DT adoption to corporate ESG outcomes, the analysis proceeds by examining improvements along each dimension, starting with environmental performance.

3.1.1. Environmental Performance

The case study analysis reveals that all four MNCs demonstrated quantifiable environmental improvements directly linked to the adoption of DT technologies. Siemens achieved a 25% reduction in energy consumption and a 20% decrease in CO2 emissions at its Amberg Smart Factory. These gains were realized through the integration of AI-enhanced DT simulations enabling real-time process optimization, and are documented in the company’s 2023 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive compliant disclosure. Unilever reported comparable progress, with a 25% decrease in food waste and a 30% reduction in plastic usage. These outcomes were driven by circular economy initiatives underpinned by DT-enabled simulations of supply flows and packaging optimization. Tesla deployed DT models to enhance sustainability in its Gigafactories, improving battery recycling efficiency by 10% and increasing energy efficiency in electric vehicle (EV) production by 12%. Finally, BP adopted AI-driven DT platforms for methane leak detection on offshore rigs, achieving a 15% reduction in methane emissions through predictive analytics and early-warning systems. Collectively, these examples highlight the capacity of DT technologies to generate substantial environmental performance improvements across diverse industrial contexts, supporting their strategic relevance in operationalizing ESG goals.

3.1.2. Social and Human Capital Impact

DT technologies have also contributed significantly to improvements in labor conditions and ethical practices within supply chains. Siemens deployed hazard detection DT systems within its manufacturing units, resulting in a 30% reduction in workplace injuries and a 50% increase in emergency response speed, demonstrating the value of real-time monitoring in enhancing occupational health and safety. Unilever adopted blockchain-integrated DT solutions to automate labor audits, leading to an 18% decrease in unethical supplier practices, as verified through Sedex assessments and internal ESG compliance reviews. Tesla focused on ergonomic simulations using DTs to mitigate repetitive strain injuries in its assembly lines, achieving a 16% reduction over a two-year period. Similarly, BP used DT-enabled simulation platforms to enhance emergency preparedness and crew scheduling on offshore installations, resulting in a 22% improvement in response efficiency based on internal audit metrics. These cases illustrate how DTs not only support operational optimization but also act as catalysts for strengthening human capital resilience and ethical supply chain governance.

3.1.3. Governance and ESG Reporting Improvements

DT technologies have also played a pivotal role in enhancing ESG governance and automating sustainability disclosures. Siemens succeeded in shortening its ESG reporting cycle from eight weeks to just three by deploying a CSRD-aligned dashboard built on its proprietary MindSphere DT infrastructure, illustrating the efficiency gains possible through real-time data integration. Unilever utilized DT-powered scenario simulations to validate compliance with both the EU taxonomy and U.S. SEC guidelines, thereby strengthening the traceability of its disclosures across multiple regulatory regimes in 2023. Tesla institutionalized ESG oversight through the implementation of a digital “ESG control tower” at board level, contributing to a 12.5-point increase in its Sustainalytics disclosure quality score over the period 2021–2023. BP also leveraged DT-based greenhouse gas simulation models within its compliance systems, which facilitated three successive external ESG audits without major findings—highlighting the transparency and auditability benefits of DT deployment. Together, these cases emphasize the capacity of DTs to reinforce governance structures, support multi-framework alignment, and institutionalize ESG accountability in large multinational corporations. For a better visualization of comparisons between MNCs, Table 2 shows synthesized data.

Table 2.

Cross-Company comparison of environmental, social, and governance improvements attributed to digital twin adoption.

The author finds that DTs enable substantial improvements across all ESG dimensions. Specifically, they function as integrative infrastructures that automate compliance, enable simulation-driven foresight, and enhance traceability and safety. The evidence validates the conceptual proposition that DTs are not merely technical enablers, but strategic instruments for ESG transformation, adaptable across sectors when institutional maturity and data capabilities are present.

3.1.4. Event Study

The author examined how financial markets respond when companies publicly link DT technologies to ESG commitments. The results reveal that investors consistently reacted positively, although with different magnitudes, to announcements explicitly connecting digital innovation with sustainability goals. Across the cases, market reactions were most favorable when DT announcements were clearly and explicitly linked to ESG objectives (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) following public announcements of digital twin adoption for ESG objectives.

In the case of Siemens, the substantial abnormal return reflects investor confidence in the company’s ESG technology strategy, particularly its alignment with the European Union’s CSRD. The announcement emphasized real-time emissions modeling and digital audit readiness, the capabilities increasingly valued by institutional investors.

Unilever’s announcement also generated a statistically significant gain, reinforcing its position as an ESG leader. The deployment of NVIDIA-powered DTs to simulate product emissions demonstrated a credible commitment to scope-based accountability and net-zero planning across its global value chains.

BP experienced a more cautious yet positive response. While the integration of methane-monitoring DTs was welcomed, investor sentiment was tempered by the sector’s reputational legacy. The result suggests that even in traditionally high-emission industries, digital ESG tools can signal credible intent, provided transparency is strong.

By contrast, Tesla’s announcement drew a relatively muted market response. The lack of statistical significance suggests that investors did not interpret the DT implementation as a strong ESG signal, likely due to insufficient framing of the sustainability impact. For Tesla, the cumulative abnormal return of +0.42% was not statistically significant. Examination of the announcement text indicated that the deployment of digital twin technology was communicated primarily as part of a wider update on production automation and AI-driven manufacturing efficiency, with only a brief reference to energy modeling and sustainability implications. Because ESG benefits were not clearly emphasized, investors may not have interpreted the announcement as an ESG-oriented digital transformation initiative. This lack of explicit ESG framing provides a plausible explanation for the muted market reaction.

These findings support the idea that DTs are not only technical infrastructures, but also strategic signaling mechanisms. Investors appear to reward companies that use DTs to enhance transparency, simulate compliance, and align operations with emerging sustainability expectations. The author concludes that DT technologies, when embedded in a coherent ESG narrative, can contribute directly to capital market legitimacy, potentially lowering risk premiums and enhancing long-term firm valuation.

3.2. Quantitative Regression Analysis

The quantitative analysis aimed to evaluate the relationship between DT adoption and ESG performance, using a machine learning-supported panel regression model built from a structured dataset of 110 MNCs. These firms, selected from the top ESG performers across 11 GICS-aligned sectors, were categorized into DT adopters and non-adopters based on validated disclosures related to DT deployment in ESG-relevant contexts.

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics and Variable Distribution

The descriptive analysis revealed balanced representation across sectors, with DT adoption observed in approximately 38% of the sample. Mean ESG scores (normalized to 0–1) were generally higher among adopters than non-adopters, suggesting a potential link between technological sophistication and sustainability outcomes. The average ESG score among DT adopters was 0.79, compared to 0.72 for non-adopters. Firms with board-level ESG committees consistently outperformed those without, reinforcing governance structures as key facilitators of ESG effectiveness. As expected, firm size (log of assets) was positively correlated with ESG performance, indicating the enabling role of organizational capacity.

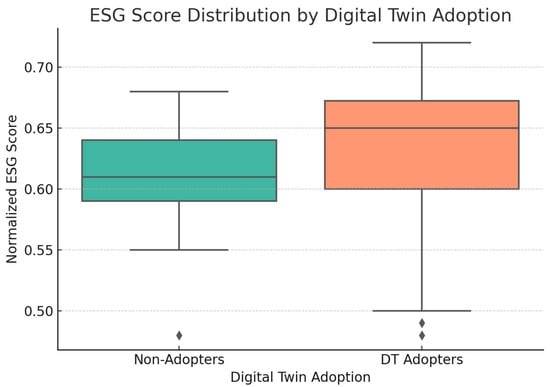

3.2.2. Model 1—Baseline Regression

The first regression model assessed the direct relationship between DT adoption and ESG performance, controlling for firm size, ESG governance, and industry effects. The findings confirm that DT adoption is associated with stronger ESG performance, even after accounting for firm size and governance structures (DT Adopter: –statistically significant positive effect; Company size (log assets): ; ESG Committee: (marginally significant; although the p-value does not meet the conventional 0.05 threshold, it is close enough to suggest a meaningful trend, especially in fields like management, strategy, or sustainability research, where complex constructs (like governance) are often noisy but theoretically important). Firm size (Log Assets) exhibits a statistically significant negative association with ESG performance (β = −0.0119, p = 0.013). Because this finding diverges from mainstream ESG literature expectations, detailed theoretical interpretation is deferred to the Section 4. These results encapsulate three important aspects: (i) DT adopters exhibit a higher median ESG score and a tighter interquartile range, (ii) DT adoption is positively associated with ESG performance, and (iii) Figure 1 highlights a few outliers, especially among non-adopters, reinforcing the variability and potential lack of structural ESG alignment in that group. Although larger firms typically possess greater resource capacity for ESG initiatives, the negative coefficient for firm size suggests that scale alone does not translate into higher ESG performance. Large multinationals may face higher structural complexity, dispersed supply chains, and fragmented governance arrangements, which can reduce consistency across sustainability metrics. This result indicates that organizational complexity may outweigh resource advantages when ESG integration is not strongly coordinated.

Figure 1.

Boxplot of distribution on normalized ESG scores between firms that adopted DT technology and those that did not.

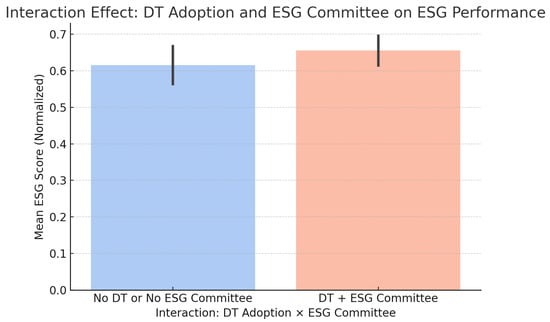

3.2.3. Model 2—Governance Interaction

To test whether internal governance mechanisms amplify the effect of DT adoption, Model 2 included an interaction term and findings show (i) interaction (DT × ESG Committee): β4 = 0.028, p = 0.202 (not statistically significant), (ii) the main effect of DT adoption becomes nonsignificant when the interaction is added (p = 0.33) and (iii) firm size remains negatively significant (p = 0.027). Although firms that combine DT adoption with a board-level ESG Committee show higher mean ESG scores, the interaction effect is not statistically significant. Therefore, the governance-based synergy should be interpreted as a descriptive pattern rather than a statistically validated moderation. This potential synergy is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows that firms combining DT adoption with the presence of a board-level ESG committee achieve higher mean ESG performance than those lacking one or both components.

Figure 2.

Bar chart–Interaction effect between DT adoption and the presence of an ESG Committee on ESG performance.

Firms that simultaneously adopted DT technologies and maintained a board-level ESG committee achieved the highest average ESG performance, as shown in the comparative bar chart. This group outperformed those lacking one or both attributes, reinforcing the theoretical proposition that governance structures may enhance the effectiveness of digital transformation efforts in ESG domains. Although the statistical interaction term in Model 2 was not significant at conventional thresholds, the observed difference in mean ESG scores suggests a potential synergistic relationship. The presence of formal ESG oversight may provide the strategic alignment and accountability mechanisms necessary to fully employ the capabilities of DT technologies in pursuit of sustainability outcomes.

3.2.4. Model 3—ESG Maturity Index

ESGMI was not used in the final regression models due to multicollinearity caused by the inclusion of the dependent variable (ESG score) within the index. In preliminary exploratory tests, adding ESGMI and its interaction with DT adoption produced overfitting (R2 ≈ 1.00) and unstable coefficients, confirming the structural dependency. The researcher, therefore, discarded this model and does not interpret its coefficients. Instead, the author used ESGMI descriptively, comparing firms with high and low ESG maturity based on a median split (Table 4).

Table 4.

High ESGMI vs. low ESGMI.

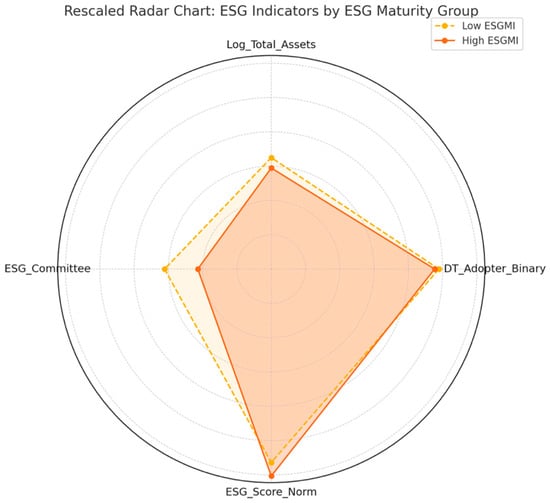

A significantly higher proportion of DT adoption was found among firms with high ESGMI (56% vs. 40%). DT adoption was 16 percentage points higher among firms with high ESG Maturity Index values, supporting the idea that organizations with greater ESG maturity are more inclined to adopt advanced technologies such as DTs. This difference appears to be driven by the higher prevalence of ESG committees and larger firm size among the high-ESGMI group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Radar chart–high vs. low ESGMI. Re-scaled for better visualization. Source: author’s elaboration based on case data.

The radar chart compares firms by ESG Maturity Index across four indicators (DT adoption, firm size, ESG committee presence, ESG performance), normalized to a 0–1 scale. High-ESGMI firms outperform in governance and DT adoption—key enablers of readiness—while firm size adds further capacity for scaling ESG technologies. Similar ESG scores across groups are expected, as ESG performance feeds into the index. The chart’s shape highlights that ESG maturity is not about isolated scores but integrated organizational alignment. These findings support the index’s value in distinguishing firms prepared to leverage DTs for ESG outcomes.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

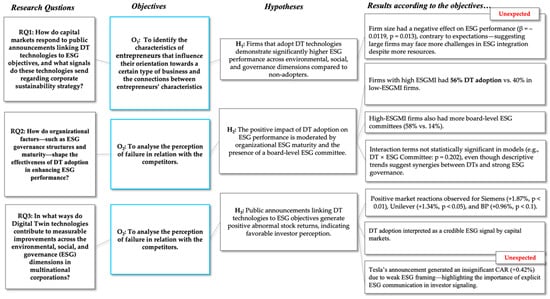

This study set out to examine how DT technologies contribute to ESG value creation in MNCs. For a better understanding of the logical structure of the study, the author has created Figure 4 to present the flow of the process deployed to confirm or reject H1, H2, and H3.

Figure 4.

Alignment between research questions, objectives, hypotheses, and empirical findings.

The study successfully met its objectives using a multi-method approach. Case studies showed that DT adoption is associated with ESG improvements, and this association is consistent with the quantitative results, which support the link between DT adoption and higher ESG scores. While the governance interaction was not statistically significant, descriptive patterns suggest that both ESG governance and ESG maturity may enhance DT impact. Although the results show a positive association between DT adoption and ESG performance, the cross-sectional research design does not allow for determination of whether DTs improve ESG performance or whether firms with strong ESG practices are better positioned to adopt DTs earlier. Event study analysis found positive investor reactions to DT-ESG announcements, especially for Siemens and Unilever, though not for Tesla, likely due to weak ESG framing. A surprising negative link between firm size and ESG score suggests larger firms may face integration challenges. A key empirical insight of this study is the negative relationship between firm size and ESG performance. While large firms possess superior resource capacity for ESG initiatives, they also face greater integration challenges, operational dispersion, and regulatory heterogeneity across geographies. This suggests that scale introduces institutional complexity that may offset resource advantages unless strong coordinating ESG governance is in place. In other words, firm size improves ESG outcomes only when governance structures are sufficiently integrated to manage cross-unit consistency and accountability. Overall, the study highlights that DTs can enhance ESG performance, but their effectiveness depends on governance, maturity, and strategic communication. The interaction term in Model 2 was not statistically significant, indicating that the moderating role of ESG governance is not supported by inferential evidence and should be interpreted only as a descriptive tendency rather than a tested causal mechanism.

Also, the negative association between firm size and ESG performance suggests that resources alone do not guarantee sustainability excellence. Large multinationals typically operate across multiple jurisdictions, supply chains, and regulatory environments, introducing complexity that may outweigh the advantages of resource abundance. ESG progress in such firms requires coordination across diverse business units, extensive compliance infrastructures, and cultural alignment—a process that often advances more slowly than in smaller, more agile organizations. This finding indicates that firm size enhances ESG performance only when governance and organizational integration mechanisms are sufficiently strong to manage institutional complexity.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

While ESG maturity remains theoretically relevant as a potential enhancer of DT effectiveness, the current dataset did not allow a statistically valid moderation test because ESGMI included the dependent variable. For this reason, the moderation hypothesis remains theoretically plausible but empirically untested. This study advances ESG and digital innovation literature by framing DT as boundary-spanning technologies that drive both internal transformation and external legitimacy. From a socio-technical systems view, DT adoption reshapes decision-making and governance through real-time data integration and cross-functional collaboration. From a stakeholder perspective, DTs can enhance transparency and trust, as confirmed by positive investor reactions to ESG-linked announcements. Overall, the findings position DTs as strategic enablers of ESG, not just technical tools, challenging traditional compliance-driven views and broadening the scope of digital innovation research.

4.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

For managers and sustainability leaders, the study provides practical guidance on using DT beyond compliance. DTs enable real-time ESG management through simulation, automation, and predictive monitoring. Effective implementation requires cross-functional integration of ESG into IT and operations, as well as digitally skilled teams. Success also depends on organizational readiness-firms with mature ESG governance benefit more. Additionally, positive investor reactions to DT-ESG initiatives highlight their value as tools for enhancing both reputation and financial performance. For large multinationals, successful deployment of DT technologies for ESG requires strong internal coordination; without robust governance integration, the scale and complexity of operations may limit the sustainability benefits that DTs can generate.

4.3. Policy and Regulatory Implications

From a policy standpoint, the study underscores the importance of DTs as digital infrastructure for effective ESG regulation. As standards like the CSRD raise disclosure requirements, many firms struggle with outdated systems. DTs can streamline compliance by automating data integration and producing audit-ready outputs. Policymakers should consider mandating or incentivizing DT adoption, especially in high-impact sectors. Additionally, public–private efforts to develop open, interoperable ESG data systems are essential to ensure reporting drives real change rather than becoming a mere formality. More actionable policy pathways can be identified based on the sector-specific challenges observed in this study. First, governments can incentivize DT adoption through mechanisms such as tax credits for DT-enabled ESG reporting, subsidies for digital infrastructure upgrades, and preferential access to green financing for organizations deploying DTs in emissions-intensive domains. Second, development of open ESG data systems requires clear technical standards to ensure interoperability and auditability. Relevant examples include standardized application programming interfaces for emissions reporting, alignment with CSRD and ISSB disclosure taxonomies, and mandatory timestamping and traceability protocols for real-time ESG data exchange. Third, early policy support would be most impactful in high-emission and safety-critical sectors, including energy, heavy manufacturing, logistics, and construction, where DTs can rapidly reduce environmental and social risks. These recommendations aim to provide practical guidance for policymakers seeking to scale digital sustainability infrastructures while maintaining market competitiveness and regulatory integrity. These measures illustrate that policy support for DTs should go beyond general encouragement and extend to targeted economic incentives, infrastructure standards, and sector-specific deployment priorities. The policy suggestions presented here derive directly from observable successful corporate practice. For instance, Siemens’ CSRD-aligned Digital Twin dashboard shows how real-time ESG reporting infrastructures can reduce reporting cycles by over 60% while increasing audit reliability, demonstrating the value of regulatory-ready digital systems. Similarly, BP’s methane-detection Digital Twin deployment illustrates how targeted DT incentives in high-emission sectors can translate into measurable environmental impact. These examples underscore the need for policy frameworks that reward not only disclosure but also technology-enabled traceability and verification.

4.4. Limitations

While the study has methodological limits, such as reliance on proxy data and potential confounders in event analysis; it remains a rigorous early exploration of how DTs intersect with ESG strategies in MNCs. Case firms were chosen for depth, not breadth, capturing leaders shaping future norms. Despite attribution challenges, consistent positive market reactions strengthen the findings’ credibility. The regression model, though constrained by current disclosure practices, was built with methodological care. Overall, the study captures a pivotal transition (2018–2023) in ESG digitalization, offering a solid theoretical base and setting the stage for future research. Also, the moderating role of ESG maturity could not be statistically validated because available maturity proxies contain ESG performance indicators, creating multicollinearity. Future research should employ non-overlapping maturity indicators such as years of ESG reporting, clarity of sustainability strategy, third-party ESG assurance, or dedicated sustainability budgeting. Finally, while the results show a positive association between DT adoption and ESG performance, the cross-sectional dataset does not permit strong causal inference. It remains plausible that firms with higher ESG performance, stronger governance structures, and greater resource capacity are more likely to invest in advanced technologies such as digital twins. Therefore, reverse causality cannot be ruled out. Establishing the direction of causation requires longitudinal or quasi-experimental designs, such as difference-in-differences analysis around the timing of DT deployment or instrumental variable strategies based on regulatory technology shocks. Future research applying these methods can clarify whether DTs improve ESG outcomes or whether leading ESG performers adopt DTs earlier.

4.5. Future Research

Future research should explore the long-term impact of DTs on ESG performance through longitudinal studies. Comparative analyses across industries and regulatory contexts can reveal sector-specific dynamics. Micro-level studies are needed to understand how DTs reshape roles, training, and organizational culture. A systems-level view could unpack how different tech stacks influence ESG outcomes. Ethical and political questions—like data control and algorithmic governance—warrant critical inquiry. Finally, policy-focused research should assess how regulation and public support can foster DT adoption, especially for SMEs and firms in the Global South, ensuring inclusive and responsible digital ESG transitions. As ESG disclosure standards evolve, future datasets may allow a clean test of whether ESG maturity amplifies the impact of digital twin adoption on sustainability performance. Future work using longitudinal datasets may allow a clearer test of whether ESG governance strengthens the impact of DT adoption.

Funding

The APC was funded by Transilvania University of Brasov.

Data Availability Statement

Available data on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prodanova, N.; Tarasova, O. ESG Subsystems and Strategies to Enhance Their Operational Efficiency. Cad. Educ. Tecnol. Soc. 2024, 17, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S. Design an ESG Rating System: A Case Study of the Chinese Dairy Industry. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 72, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Макаренкo, І.; Makarenko, S. Multi-Level Benchmark System for Sustainability Reporting: EU Experience for Ukraine. Ac-count. Financ. Control. 2023, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasari, T.; Traversi, M. The Impact of the CSRD and the ESRS on Non-Financial Disclosure. Symphonya Emerg. Issues Manag. 2024, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A.; Saleh, A.; Eliwa, Y. Does Mandating ESG Reporting Reduce ESG Decoupling? Evidence From the European Union’s Directive 2014/95. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 33, 1305–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, D.; Choi, H.; Han, S.H. Corporate Bond Market Reaction to the Mandatory ESG Disclosure Act: Is Sustainium Sustainable? Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 53, 596–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosures in Europe. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2015, 6, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, R.E.; Tierney, P. Fintech Data Infrastructure for ESG Disclosure Compliance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Aboud, A.; Saleh, A. ESG Practices and the Cost of Debt: Evidence From EU Countries. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2021, 79, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C. Assessing the Effects of Urban Digital Infrastructure on Corporate En-vironmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Performance: Evidence From the Broadband China Policy. Systems 2023, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Goh, M.; Cao, Y. Can Digital Economy Development Facilitate Corporate ESG Performance? Sustainability 2024, 16, 3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, R.; Narula, R.; Rao, P.; Kumar, S.; Paltrinieri, A. ESG Investing & Firm Performance: Retrospections of Past & Reflections of Future. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 32, 1096–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S.; Chouaibi, J.; Rossi, M. ESG and Corporate Financial Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation: UK Common Law Versus Germany Civil Law. Euromed J. Bus. 2021, 17, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Li, S. Analyzing the Relationship Between Digital Transformation Strategy and ESG Performance in Large Manufacturing Enterprises: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaimani, S. From Compliance to Capability: On the Role of Data and Technology in Environment, Social, and Governance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Ding, L.; Wang, C. Development of a Framework to Support Whole-Life-Cycle Net-Zero-Carbon Buildings Through Integration of Building Information Modelling and Digital Twins. Buildings 2022, 12, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, A.; Alshboul, O.; Arar, M. Enhancing Urban Sustainability and Resilience: Employing Digital Twin Technologies for Integrated WEFE Nexus Management to Achieve SDGs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galera-Zarco, C. Unleashing the Potential of Digital Twin in Offering Green Services. IET Conf. Proc. 2022, 2022, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trienens, M.; Rasor, R.; Kharatyan, A.; Dumitrescu, R.; Anacker, H. Digital Twins to Increase Sustainability Throughout the System Life Cycle: A Systematic Literature Review. Proc. Des. Soc. 2024, 4, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solman, H.; Kirkegaard, J.K.; Smits, M.; Van Vliet, B.; Bush, S. Digital Twinning as an Act of Governance in the Wind Energy Sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 127, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, M.N.K.; Zhang, P. Digital Twins: From Personalised Medicine to Precision Public Health. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barn, B. The Sociotechnical Digital Twin: On the Gap Between Social and Technical Feasibility. In Proceedings of the 24th Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15–17 June 2022; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, L.C.; Cecconi, F.R.; Maltese, S.; Rinaldi, S.; Ciribini, A.L.C.; Flammini, A. Leveraging Digital Twin for Sustainability Assessment of an Educational Building. Sustainability 2021, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Digital Twin: Application and Prospect. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2023, 12, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Court, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Thirunavukarasu, A.; Zhao, Y. A Review of Digital Twin Technologies for Enhanced Sustainability in the Construction Industry. Buildings 2024, 14, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytinen, K.; Newman, M. Explaining Information Systems Change: A Punctuated Socio-Technical Change Model. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2008, 17, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, G.; Sommerville, I. Socio-Technical Systems: From Design Methods to Systems Engineering. Interact. Comput. 2022, 23, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.; Naik, S. Industry 4.0 Integration with Socio-Technical Systems Theory: A Systematic Review and Proposed Theo-retical Model. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, É.; Soliman, M.; Gerstlberger, W.; Frank, A.G. Sociotechnical Factors and Industry 4.0: An Integrative Perspective for the Adoption of Smart Manufacturing Technologies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 33, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, T.; Ayton, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Lam, M. Using Socio-Technical Systems Theory to Study the Health Information Management Workforce in Australian Acute Hospitals. Res. Sq. 2023, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.; Brown, A.; Ferdig, R. Developing International Leadership in Educational Technology. In E-Training Practices for Professional Organizations; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J. Ordering Theories: Typologies and Conceptual Frameworks for Sociotechnical Change. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2017, 47, 703–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhovnych, O.; Bakhmat, N.; Kochubei, O.; Duchenko, A.; Ivashkevych, Y. Digital Competence of Specialists in Socio-Economic, Physics, and Mathematics Specialties, Company Managers in Professional Activities. Rev. Amazon. Investig. 2024, 13, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.A.D.R.; Carvalho, G.M.D.; Boaventura, J.M.G.; Souza Filho, J.M.D. Determinants of Corporate Social Performance Disclosure: A Literature Review. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Trojanowski, G.; Sealy, R. Narrative Reporting: State of the Art and Future Challenges. Account. Eur. 2021, 19, 7–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.E.; Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Younis, N.S. Born Not Made: The Impact of Six Entrepreneurial Personality Dimensions on Entrepreneurial Intention: Evidence from Healthcare Higher Education Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, H.O.; Etim, W.; Ogbonda, E. Stakeholders, Stakeholder Theory and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2024, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamandi, I.-E.; Constantin, L.-G.; Munteanu, S.M.; Cernat-Gruici, B. Mapping the ESG Behavior of European Companies. A Holistic Kohonen Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.B.; Panza, G.B.; Berhorst, N.L.; Toaldo, A.M.M.; Segatto, A.P. Exploring the Relationship Among ESG, Innovation, and Economic and Financial Performance: Evidence From the Energy Sector. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023, 18, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Exploring the Multi-Dimensional Effects of ESG on Corporate Valuation: Insights Into Investor Expectations, Risk Mitigation, and Long-Term Value Creation. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 103, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Karia, N. How ESG Performance Promotes Organizational Resilience: The Role of Ambidextrous Innovation Capability and Digitalization. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2025, 8, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J.W. Stakeholder Governance: Solving the Collective Action Problems in Joint Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2022, 47, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z.; Homayoun, S.; Rezaee, N.J.; Poursoleyman, E. Business Sustainability Reporting and Assurance and Sustainable Development Goals. Manag. Audit. J. 2023, 38, 973–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranford, R. Conceptual Application of Digital Twins to Meet ESG Targets in the Mining Industry. Front. Ind. Eng. 2023, 1, 1223989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. The Influence of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Technology on ESG Reporting Quality. Int. J. Glob. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, T.T.T.; Hanh, P.T.S. The Direct Effect of ESG Reporting on Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Global Firms During the Early Years of the Green and Digital Twin Transition. Vnu Univ. Econ. Bus. 2024, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, C.R.; DeLong, S.M.; Holt, E.G.; Hua, E.Y.; Tolk, A. Combining Green Metrics and Digital Twins for Sustainability Planning and Governance of Smart Buildings and Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhu, B.; Sun, Y. Digitalization Transformation and ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 33, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Y. A Study on the Impact of Digital Transformation on Corporate ESG Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. Digitalization, Spillover and Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence From China. J. Environ. Dev. 2024, 33, 286–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Mao, C.; Gao, Y. Executive Compensation Stickiness and ESG Performance: The Role of Digital Transformation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1166080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kräussl, R.; Oladiran, T.; Stefanova, D. A Review on ESG Investing: Investors’ Expectations, Beliefs and Perceptions. J. Econ. Surv. 2023, 38, 476–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, J. Digital Transformation, Financing Constraints, and Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 3189–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Y. The Proof Is in the Pudding: How Does Environmental, Social, and Governance Assurance Shape Non-Professional Investors’ Investment Preferences? Evidence From China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).