1. Introduction

Compared to manned vessels, USVs offer distinct advantages in performing missions that are highly dangerous, repetitive, or conducted in harsh environments [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Through complete or intermittent autonomous control by onboard computers, USVs achieve a high degree of automation. This autonomy enables them to undertake complex maritime tasks effectively while significantly reducing personnel operational risks.

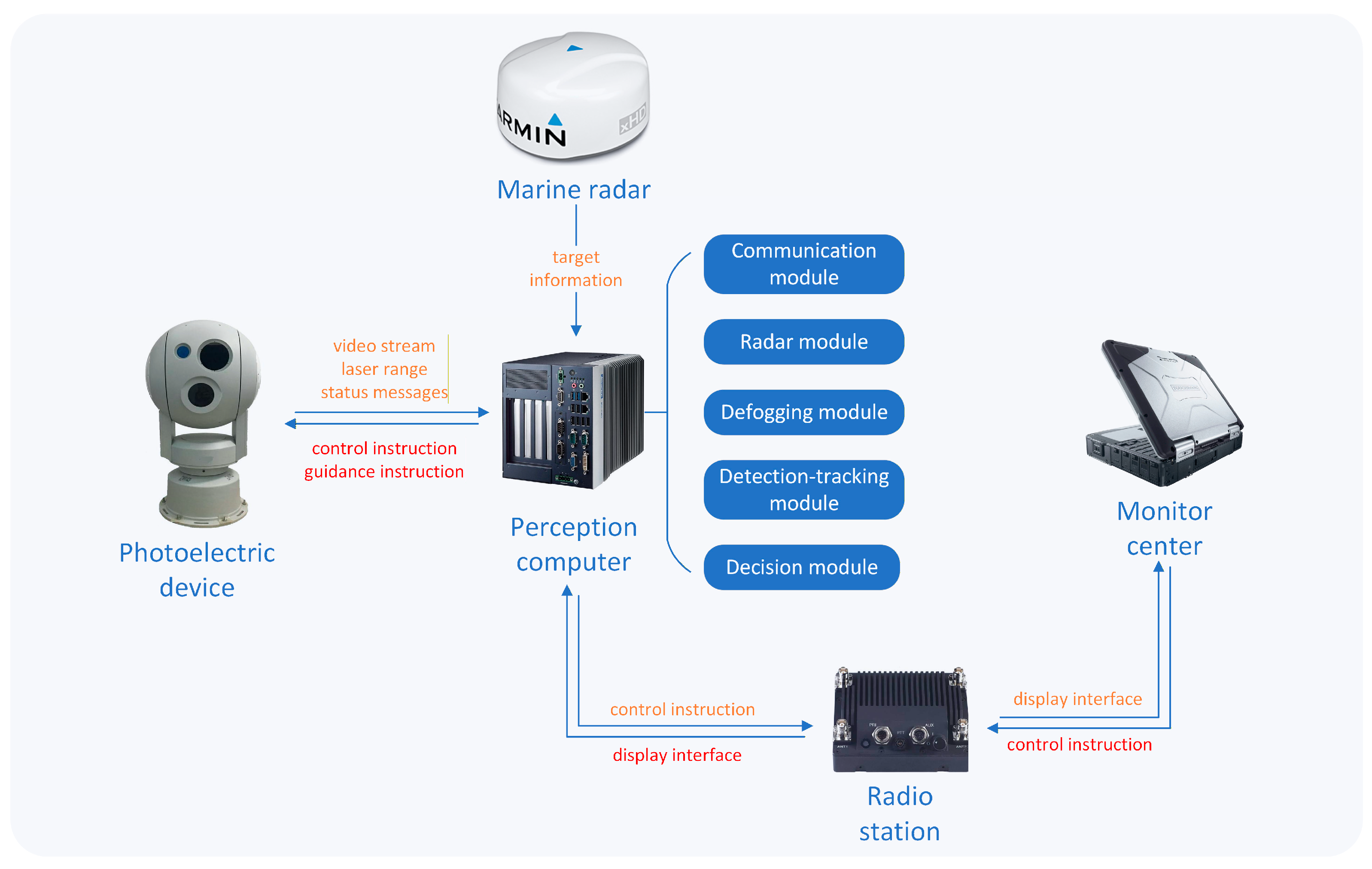

The intelligent systems of USVs include the environmental perception system, the control system, the path planning system, the communication system, and the human–computer interaction system. The environmental perception system [

5,

6], as the core of USV intelligence, is dedicated to acquiring information about surrounding maritime targets. The control system [

7,

8] is responsible for governing the USV’s steering gear and propulsion system, ensuring that the vessel follows the intended trajectory. The path planning system [

9,

10] is tasked with determining the optimal path for the USV based on the current mission requirements. The communication system [

11] facilitates data exchange between the USV and shore-based equipment. Through the communication system, the human–computer interaction system enables the issuance of commands and remote control of the USV.

USVs play significant roles in both military and civilian domains. Militarily, they are extensively deployed for anti-submarine warfare, coastal defense, mine detection, and counter-piracy missions [

12]. Their ability to sustain prolonged patrol and surveillance operations, unimpeded by human fatigue or emotional factors, makes them a vital asset for enhancing maritime security and combat capabilities. Military USVs are equipped with advanced sensors and communication systems, enabling efficient intelligence gathering, threat detection, and strike missions, thereby providing substantial support to naval operations. In civilian applications, USVs are primarily used for hydrological monitoring, maritime search and rescue, and seabed exploration. For hydrological monitoring, USVs carry various sensors to conduct real-time observation of marine environmental parameters—such as water quality, temperature, and salinity—delivering essential data for oceanographic research and resource management. In maritime search and rescue operations, their rapid response and long-range search capabilities allow for quick deployment in emergencies, improving mission efficiency and success rates for life-saving missions. Furthermore, USVs contribute significantly to seabed exploration [

13] by using advanced sonar and imaging technologies for topographic mapping, resource prospecting, and marine biological studies, thereby supporting scientific discovery and oceanographic resource development. As shown in

Figure 1, the ‘Tianxing-1′ USV is performing an area search mission [

14].

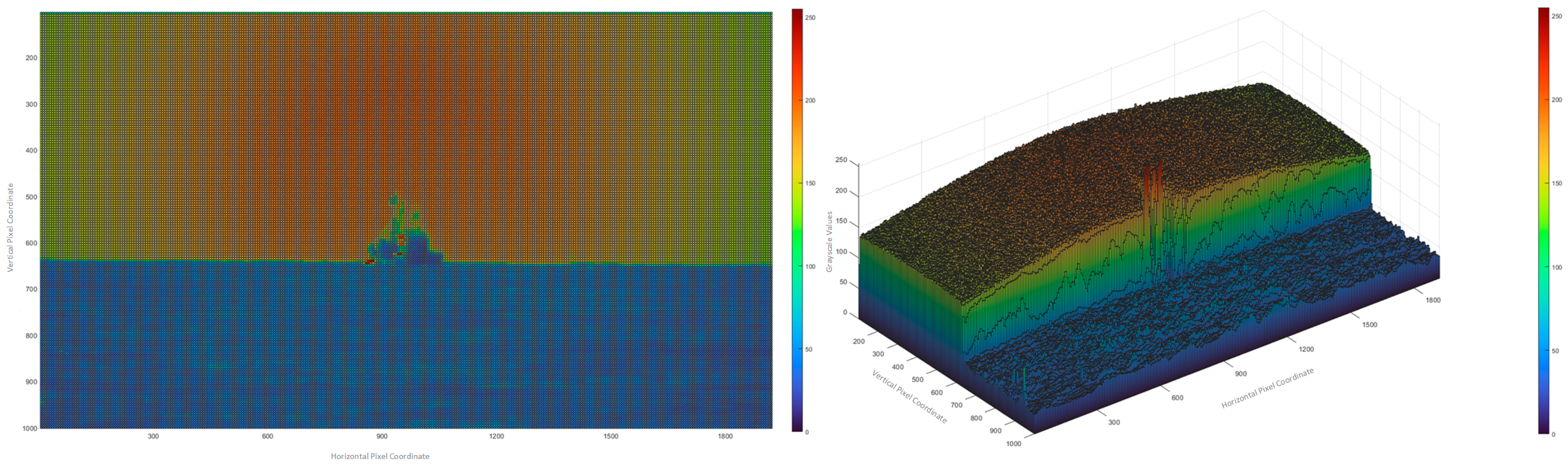

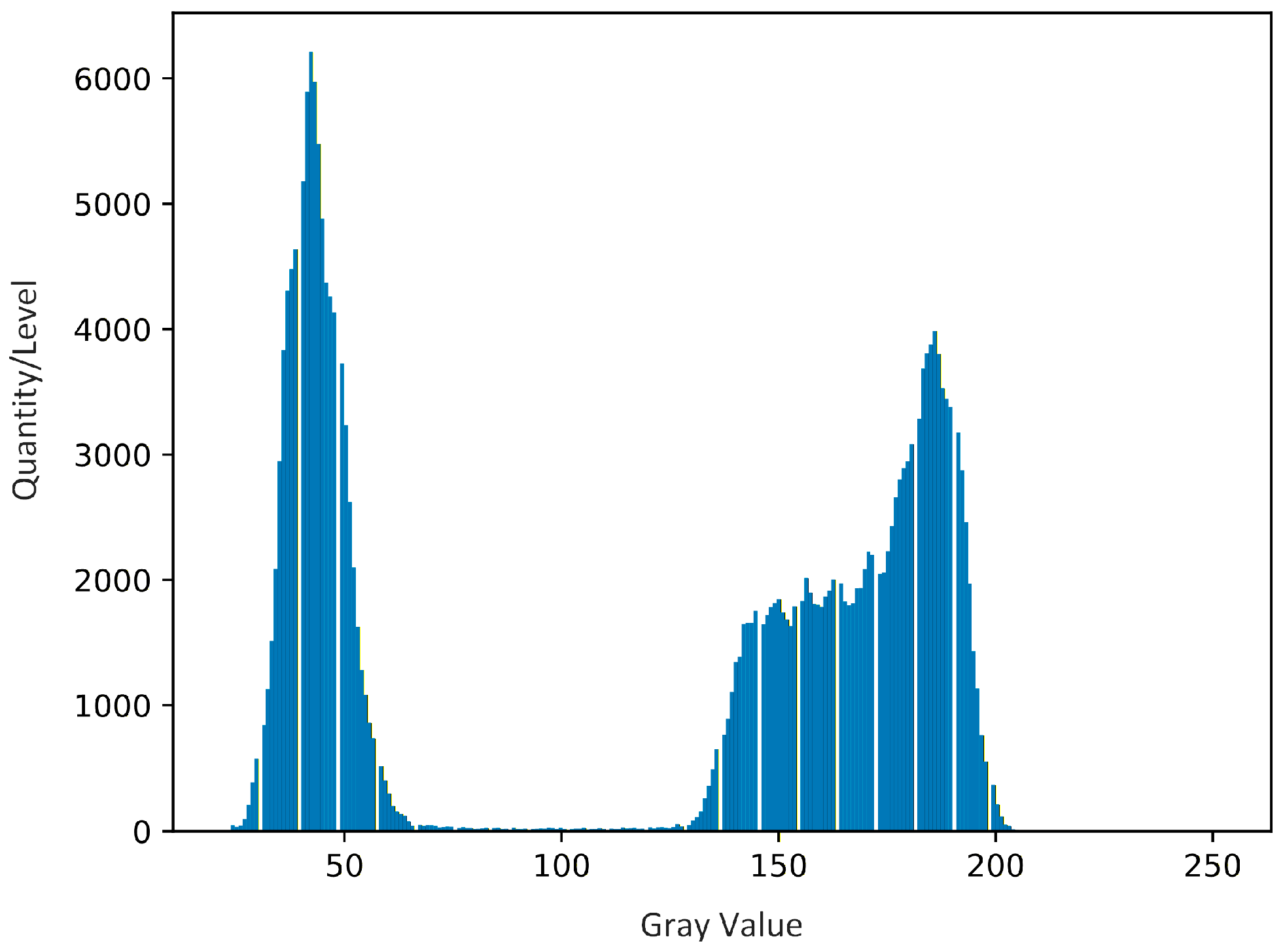

In sea–sky background images, the boundary between the sky and the sea surface is called the sea–sky line. As a crucial feature in such images, the sea–sky line helps distinguish the sky from the sea and facilitates target detection [

15,

16]. During USV missions, effective sea–sky images acquired by electro-optical devices generally comprise three main components: the sky, the sea–sky line, and the sea surface. Unlike terrestrial scenarios, where targets may appear anywhere in the image, requiring a full-image search, targets in valid sea–sky images are predominantly located near the sea–sky line. This characteristic allows for rapid positioning of marine targets by leveraging the sea–sky line’s location. Consequently, confining the detection area to the vicinity of the sea–sky line substantially reduces the ROI, mitigating interference from sea clutter and noise, lowering computational load, and improving both the efficiency and accuracy of target extraction.

Sea–sky line detection methods primarily include algorithms based on linear fitting [

17,

18], image segmentation [

19], gradient saliency [

20], transform domains [

21], and information entropy [

22]. Under simple sea–sky backgrounds, linear fitting-based algorithms demonstrate satisfactory performance. However, in complex backgrounds, selected candidate points are easily disturbed. Image segmentation-based methods struggle to determine optimal thresholds and exhibit limited adaptive noise resistance.

Gradient-saliency-based detection algorithms are prone to erroneous outcomes because various disturbances exhibit edge features similar to those of the sea–sky line. Although transform-domain methods can address sea–sky line detection in complex backgrounds, they significantly increase computational complexity, thereby failing to meet the real-time requirements of USV applications and limiting their practicality [

21]. In descending order of computational complexity, common transform-domain techniques include the Laplace transform, wavelet transform, shearlet transform, and Hough transform. While information-entropy-based algorithms exhibit strong environmental adaptability, they also entail substantial computational overhead.

4. Sea–Sky Line Detection Algorithm Based on Radar–Electro-Optical System

This algorithm is designed based on the operational mechanism of radar–electro-optical systems, offering the advantages of high precision and efficiency. In sea–sky background images, the sea–sky line represents the boundary between the sky and the sea surface. Significant brightness differences exist between the sky and sea regions in grayscale images, resulting in substantial image gradients around the sea–sky line. Building upon this gradient characteristic, the first step involves performing edge detection [

32,

33,

34,

35] on the sea–sky background image to extract edge information. Due to the strong image gradient in the sea–sky line region, its edge information can be effectively preserved.

The Canny edge detector [

36,

37] is a multi-stage edge detection algorithm that defines three fundamental criteria for edge detection: the signal-to-noise ratio criterion, the localization accuracy criterion, and the single-edge response criterion. The detailed definitions of these three criteria are as follows.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Criterion: The edge detection algorithm must accurately identify as many edges as possible in the image while minimizing false detections and missed detections. To achieve optimal edge detection performance, the algorithm needs to minimize both the false alarm rate and the missed detection rate. Let the impulse response of the filter be

, and the edge to be detected be

. Assuming the edge point is located at

, the response of the filter at this point can be expressed by the following formula:

Assuming the impulse response is defined on the interval

and the noise is denoted as

, the square root of the noise response can be expressed as:

Let

denote the mean square of the noise amplitude per unit length. The following formula can express the output signal-to-noise ratio of edge detection:

Localization Accuracy Criterion: The detected edge points should be as close as possible to the actual edge positions, or the deviation of the detected edges from the true edges of the object caused by noise should be minimized. It is expressed explicitly as follows:

and represent the first derivatives of and , respectively. The closer the detected edge is to the true edge position, the higher the value of .

Single-Edge Response Criterion: The edge points detected by the operator should have a one-to-one correspondence with the actual edge points in the image. The detected edges should be only one pixel wide, which can eliminate the occurrence of false edges and facilitate subsequent edge feature extraction and image analysis.

In the specific process of using the Canny algorithm for edge detection on the grayscale image

of a sea–sky background, a Gaussian filter is first convolved with the input image to reduce the influence of noise on the image gradient. Since the image gradient near noisy pixels is often large and can be easily mistaken for edge information, Gaussian filtering is applied to suppress noise. Here,

represents the standard deviation. The specific procedure is as follows:

Through the calculations above, the smoothed image

can be obtained. Subsequently, the Sobel operator is used to compute the first-order derivatives in the horizontal and vertical directions, i.e., the image gradients

and

. The gradient magnitude and direction of the image can be expressed as follows:

After obtaining the gradient magnitude and direction of the image, non-maximum suppression is performed. This process involves traversing each pixel in the gradient image and calculating the gradient magnitudes of the two adjacent pixels along the gradient direction. If the gradient of the current pixel is greater than or equal to the gradient values of the neighboring pixels, the current pixel is confirmed as an edge point; otherwise, it is considered a non-edge point. In this way, the image edges are refined to a width of one pixel, resulting in the image .

Although the image after non-maximum suppression still contains noise, the Canny algorithm further processes it using the double threshold detection method. This involves setting an upper threshold

, and a lower threshold

. Based on these two thresholds, pixels in the image are classified as follows: if a pixel’s value is greater than the upper threshold

, it is identified as a strong edge point; if it is less than the lower threshold

, it is considered a non-edge point; values between the two thresholds are regarded as weak edge points. Weak edge pixels caused by genuine edges will connect to strong edge pixels, while responses caused by noise will not. To track edge connectivity, each weak edge pixel and its eight neighboring pixels are examined. If any of these pixels is a strong edge pixel, the weak edge pixel is retained as a genuine edge.

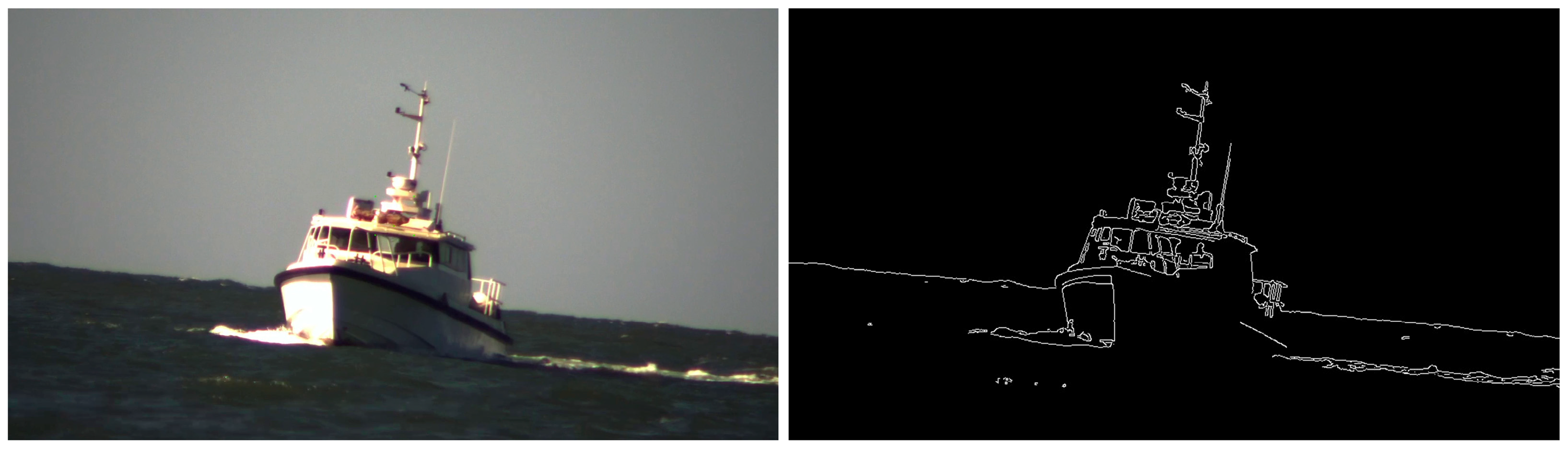

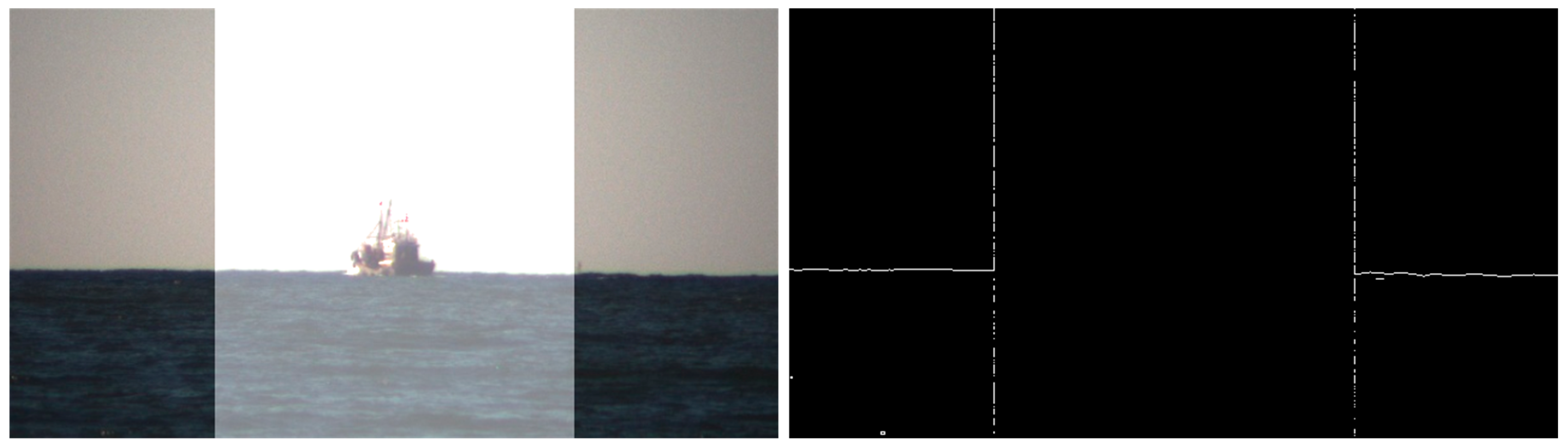

Figure 10 shows the edge detection results obtained using the Canny edge detection algorithm.

After obtaining the edge information of the sea–sky background image, the results of edge detection need to be analyzed and processed. Since the edge of the sea–sky line appears as a horizontal segment in the image, it can be inferred that segments containing more edge pixels than a predefined threshold in the edge image are likely candidate lines for the sea–sky line. However, selecting these candidate lines requires significant computational effort in the current coordinate system. To address this, the Hough transform method can be employed to extract candidate sea–sky lines more efficiently.

The Hough transform is a key technique in digital image processing for line detection. It converts the image coordinate space into a parameter space by leveraging the duality between points and lines. Specifically, a line in the original image, defined by its Equation, corresponds to a point in the parameter space. This transformation converts the problem of detecting lines in the original image into identifying peak values in the parameter space, thereby shifting the focus from global feature detection to local feature analysis.

The core principle of the Hough transform lies in the duality of points and lines: a point in the original coordinate system corresponds to a line in the parameter space, and vice versa. In the original coordinate system, all points lying on the same line share identical slope and intercept values, meaning they map to the same point in the parameter space. Thus, after projecting each point from the original space to the parameter space, the presence of clustered points in the parameter space indicates the existence of a corresponding line in the original image.

In the plane rectangular coordinate system, the Equation of a line passing through the point

can be expressed as follows:

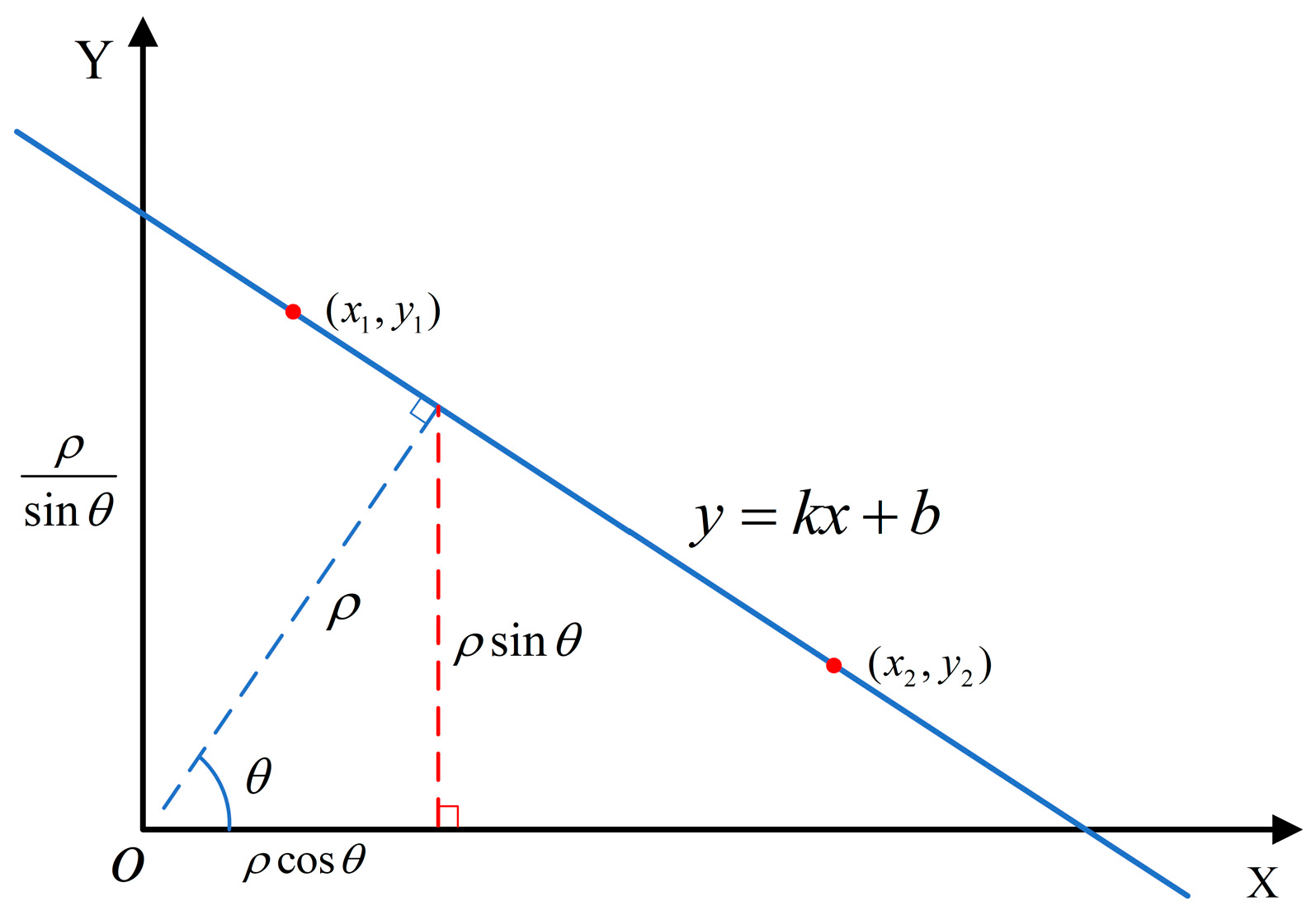

As shown in

Figure 11,

represents the slope of the straight line, and

denotes the intercept of the line. There are infinitely many lines passing through the point

, each corresponding to different values of

and

. Here,

represents the distance from the line to the origin

, and

denotes the angle between the polar radius and the polar axi. The following relationship holds:

Therefore, if we regard

and

as constants, and treat

and

as variables, the following expression can be obtained:

Two points exist at positions (

x1,

y1) and (

x2,

y2) within the image plane. The lines passing through point (

x1,

y1) and point (

x2,

y2) can be represented as follows:

As shown in

Figure 12, the line passing through point

and the line passing through point

can be represented in polar coordinates as follows. Here, the horizontal coordinate is the polar angle, and the vertical coordinate is the polar radius, with a clockwise direction being negative and a counterclockwise direction being positive.

In polar coordinates, two curves intersect at a single point. This intersection point represents the line in rectangular coordinates that passes through both points and . Conversely, in rectangular coordinates, any two points on a line correspond to two curves in polar coordinates that share a single intersection point. Furthermore, distinct points on a single line in the Cartesian coordinate system correspond to curves intersecting at a single point in the polar coordinate system. Leveraging this property, the Hough transform can be used to determine the Equation of the line connecting these points. Therefore, edge information is first extracted from visible light images using the Canny edge detection algorithm. Then the position of the sea–sky line in the edge image is determined via the method above.

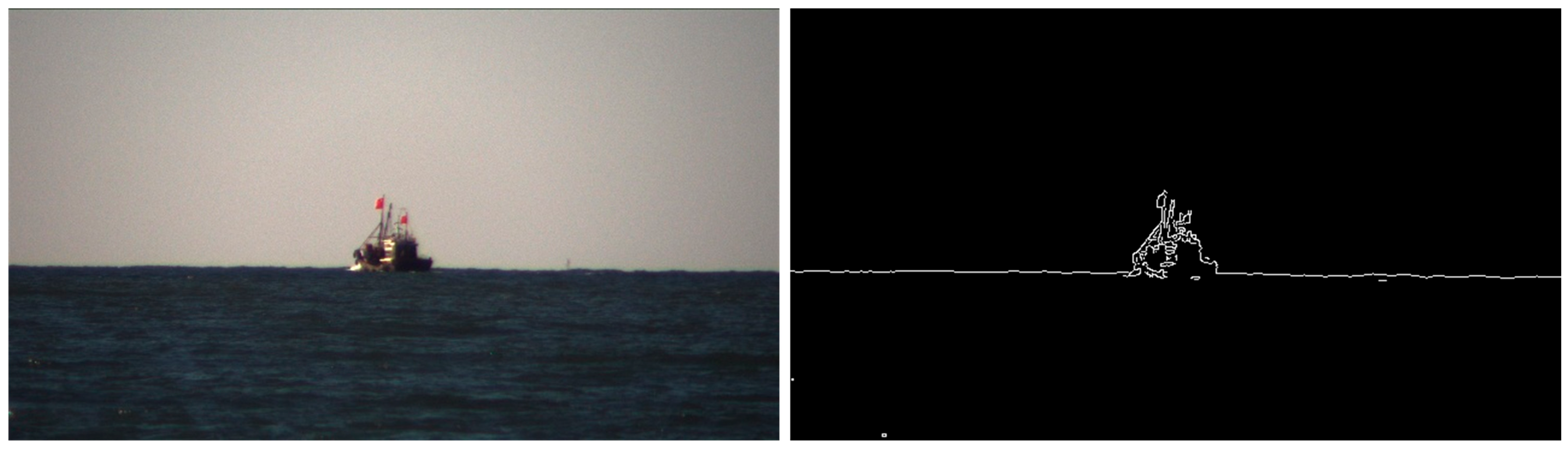

Figure 13 illustrates the edge detection results for a sea surface image, demonstrating the edge detection outcomes obtained using the Canny edge detection algorithm when a USV tracks a ship as its target.

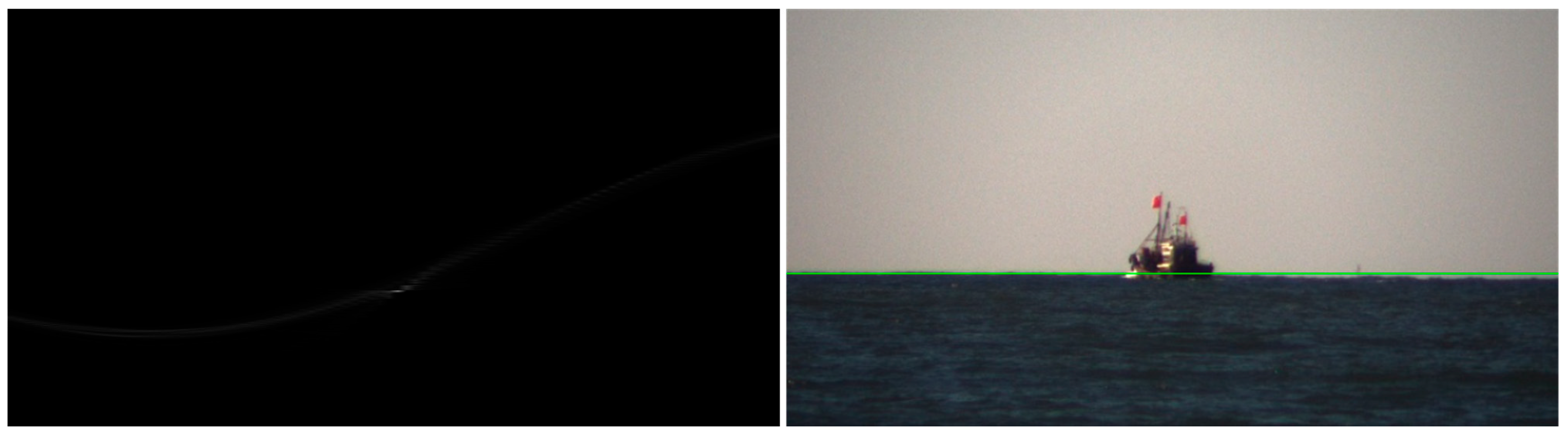

Analysis of the edge detection results reveals that edge information primarily consists of sea–sky boundary edges, target edges, and edges caused by sea clutter. Applying the Hough transform to the edge information in the image yields corresponding curves in polar coordinates. Each pixel in the edge-detected image corresponds to a curve in the polar coordinate system. In this system, the more curves a point traverses, the higher its brightness. Conversely, fewer traversed curves result in lower brightness. Thus, the brightness of a point in the polar coordinate system reflects the number of edge information points on the corresponding line in the Cartesian coordinate system. Analysis of the edge detection image reveals that the horizon line’s edge information traverses the entire image, making it the longest horizontal segment. Consequently, the brightest point in the polar coordinate system corresponds to the horizon line in the sea surface image.

Figure 14 shows the schematic diagram in polar coordinates and the horizon detection results, where the green line represents the horizon detected by the Hough transform-based horizon detection algorithm.

However, beyond the edge information of the sea–sky line, other edge details, such as target contours, also exist. These details interfere with the final sea–sky line detection, resulting in false positives and a reduction in accuracy. Among these, target edge information exerts the most significant influence. Given the guidance principle of radar-optoelectronic systems, sea surface targets typically reside in the central region of the image. Therefore, this paper proposes a sea–sky line detection algorithm tailored for radar-optoelectronic systems. This algorithm first processes the region near the target to reduce the gradient differences between pixels. Edge detection is then performed on the processed image. By diminishing gradient differences near the target, the algorithm effectively filters out target edge information, thereby enhancing the accuracy of sea–sky line detection.

Figure 15 illustrates the processing results for the target region and the corresponding edge detection results obtained using the proposed algorithm.

After processing the area near the target, significant gradient differences emerge at the boundaries, resulting in two perpendicular edge signals in the edge detection image. During task execution, the sea–sky line in visible light images is not perpendicular to the horizon. Therefore, during sea–sky line selection, these perpendicular edge signals can be filtered out by imposing angular constraints.

Figure 16 illustrates the edge detection information in polar coordinates obtained using the radar-optoelectronic system-based sea–sky line detection algorithm, along with the final result. The red line represents the sea–sky line obtained through the improved algorithm. Due to the suppression of target edge information, the number of curves in the figure is significantly reduced compared to

Figure 14. This improved algorithm not only enhances the robustness and accuracy of sea–sky line detection but also improves computational efficiency, ensuring the real-time requirements of the perception system. The algorithm is not merely applied at the image level but is a perception method specifically designed for electro-optical radar systems. This method can operate without relying on image integrity, functioning even when images are occluded or blurred.

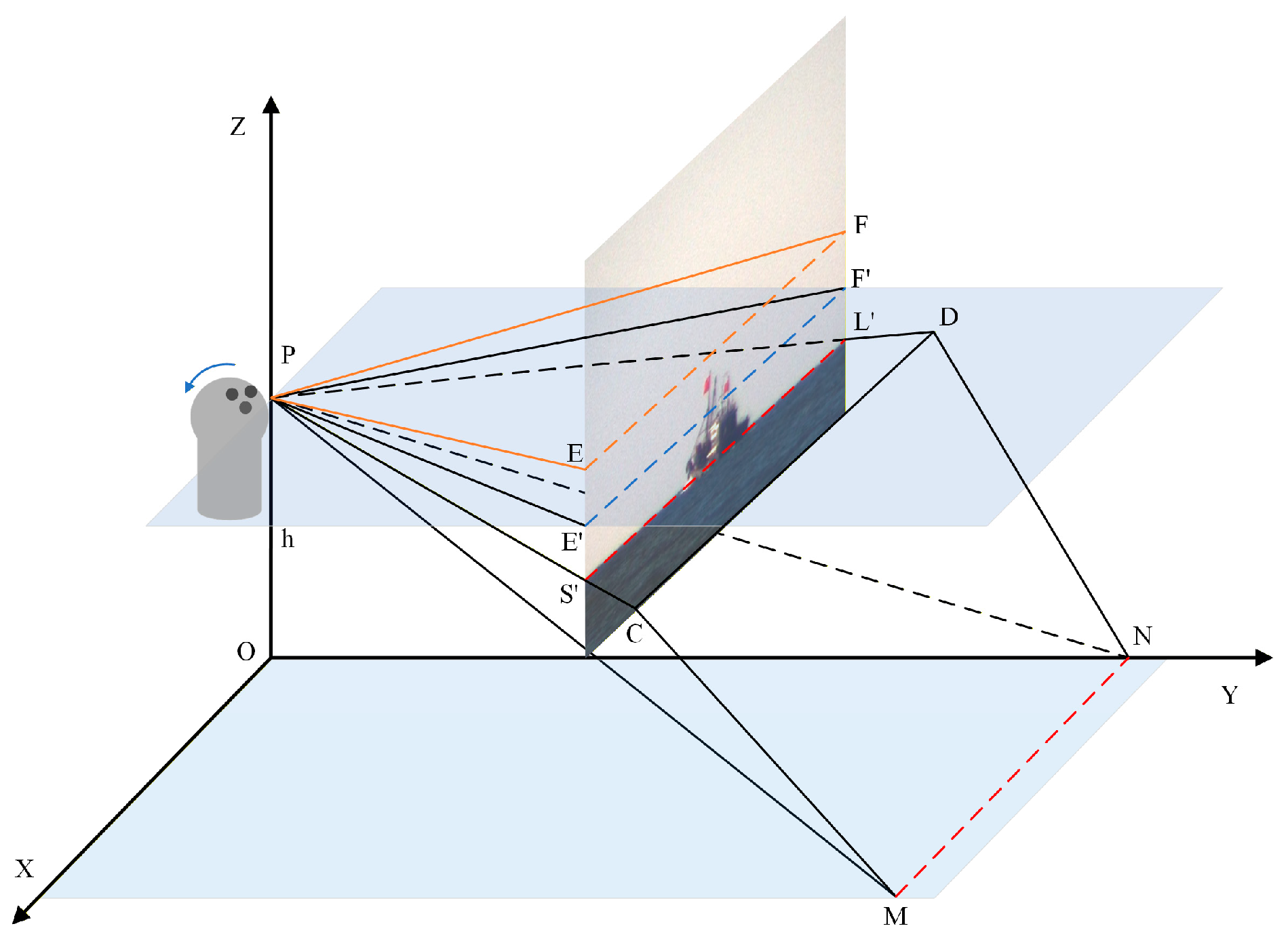

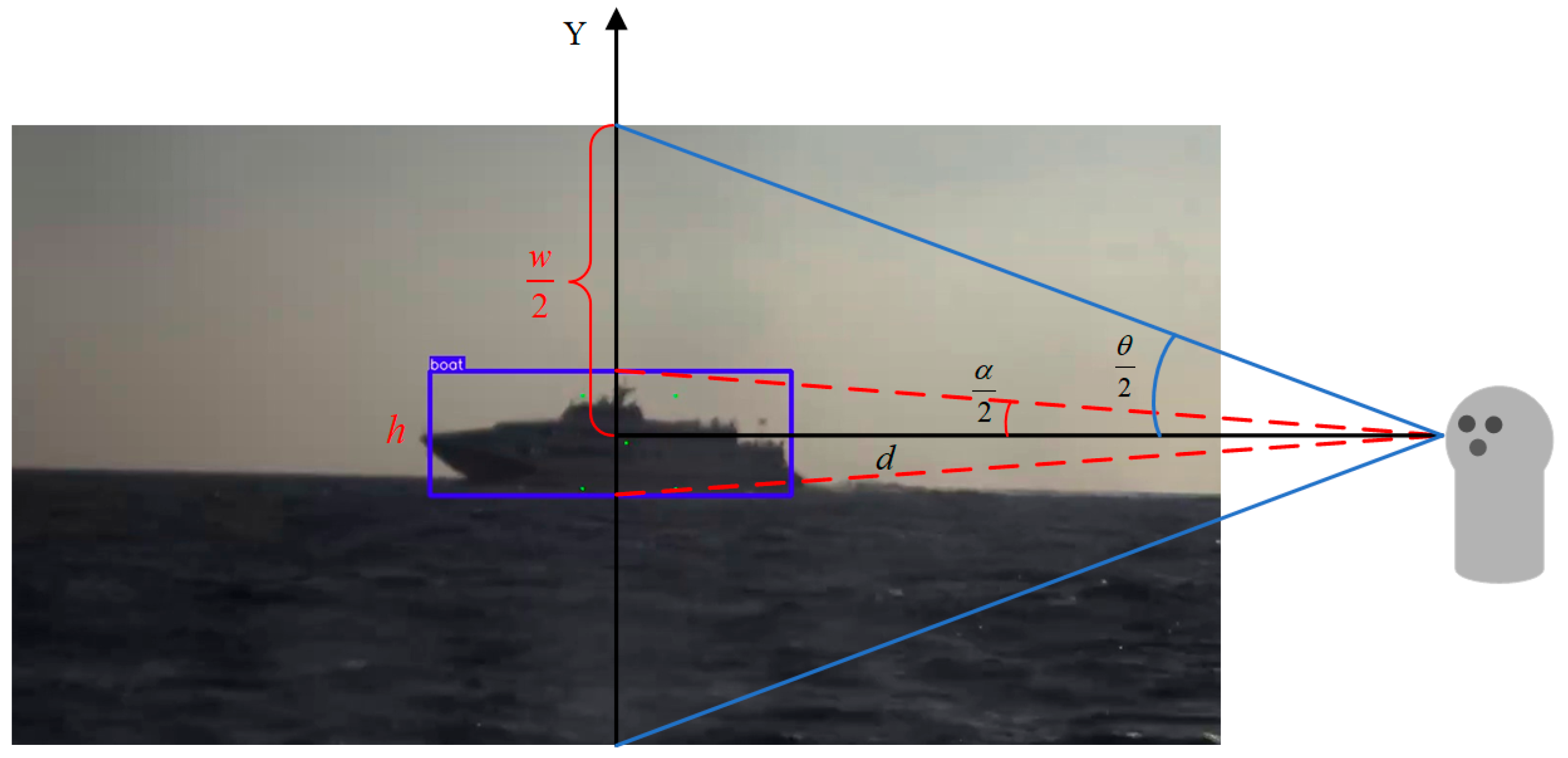

As shown in

Figure 17, the horizontal field of view of the visible light sensor is

, and the field of view occupied by the target is

. The actual image width of the plane where the target is located in the visible light image is

, and the pixel width of the visible light image is

. The resolution of the photoelectric visible light sensor is 1920 × 1080, and the field of view is 1.97 to 40 degrees. The resolution of the infrared sensor is 640 × 512, and the field of view is 2 and 10 degrees.

Additionally, the actual height of the target in the visible light image is

, while the distance

is obtained via marine radar. The target’s pixel width is

. The width of the sea–sky line suppression region in the visible light image is

, and the pixel width of this region is

. The target occupies a field of view size of

, with a sea–sky line suppression coefficient of

. The calculation process for the pixel width

of the sea–sky line suppression region is as follows.

This paper compares and analyzes the detection accuracy of the radar-optoelectronic system’s sea–sky line detection algorithm with that of the Hough transform-based sea–sky line detection algorithm in various maritime test results. The specific calculation method for sea–sky line detection accuracy is as follows.

Here,

represents the number of pixels in the horizontal direction of the image,

denotes the sea–sky line detection accuracy coefficient,

indicates the accurate vertical coordinate of the sea–sky line in the image, and

represents the vertical coordinate of the fitted sea–sky line in the image. The sea–sky line detection accuracy ranges from

. A higher

value indicates greater detection accuracy, while a lower

value signifies greater detection deviation. The sea-line detection is only used for the first frame image. Once the position of the sea-line in the first frame image is determined, the position of the sea-line in subsequent image sequences is solved using the sea-line Equation. As shown in

Table 1, sea trials are conducted in three distinct sea areas, with each set of test results analyzed accordingly. The algorithm achieves satisfactory performance across all test scenarios. However, its effectiveness is inherently constrained by its dependency on the first-frame image characteristics provided by the radar–electro-optical system.

Comparative testing revealed that, due to extensive filtering of target edge information, the radar-optical system-based sea–sky line detection algorithm achieved higher detection accuracy while reducing computational load compared to the Hough transform-based approach. In the first test group, the improvement rate in sea–sky line detection accuracy is 20.66%; in the second test group, it is 11.65%; and in the third test group, it is 19.46%. Combining the results from all three test groups, the overall improvement in sea–sky line detection accuracy reached 17.3%. The algorithm achieves satisfactory performance across all test scenarios. However, its effectiveness is inherently constrained by its dependency on the first-frame image characteristics based on the radar–electro-optical system.

5. Target Detection Algorithm Based on the Sea–Sky Line

The sea–sky line-based target detection algorithm is a method that performs target detection by leveraging the position of the sea–sky line. Compared to conventional target detection algorithms, this approach removes interfering information from non-target regions, effectively improving both the accuracy and computational efficiency of target detection. The sea–sky line detection algorithm based on the radar–electro-optical system can accurately determine the position of the sea–sky line within visible light images. In USVs, the electro-optical equipment and the inertial navigation system adopt an integrated design, thereby reducing errors caused by hull deformation during navigation. Based on the principle of how six-degree-of-freedom motion alters the position of the sea–sky line in the image, the current sea–sky line position can be rapidly acquired. According to the guidance mechanism of the radar–electro-optical system, the designated target in the visible light image is located within the sea–sky line region. Consequently, the sea–sky line-based target detection algorithm can swiftly locate sea surface targets by referencing the sea–sky line’s position. By narrowing down the target’s ROI, it reduces interference from sea clutter and noise in the background, thus decreasing the computational load during target extraction and enhancing the efficiency and precision of sea surface target extraction.

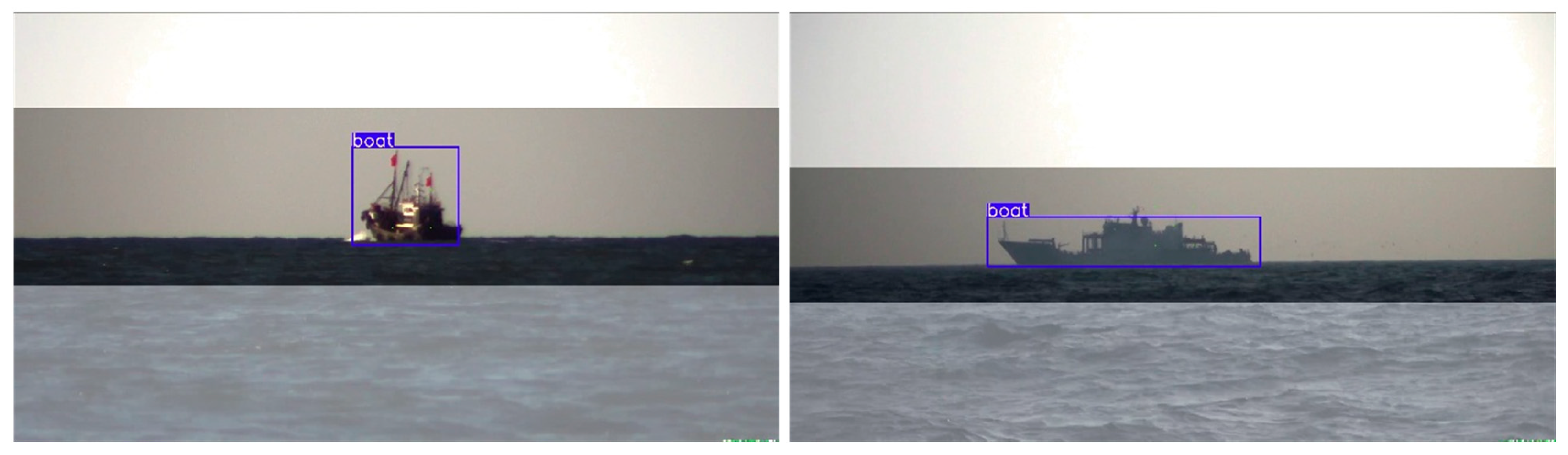

Figure 18 displays an optical image acquired by a USV during an actual mission execution, clearly showing the positional relationship between the sea–sky line and the designated target within the optical image.

A comparative analysis of optical images reveals that, owing to the perception mechanism where the marine radar cues the electro-optical equipment on the USV, the guide target within the acquired optical images is typically located in the vicinity of the sea–sky line. To investigate the relationship between the size of the sea–sky line region and the target size, the following research is conducted.

Figure 19 illustrates a schematic diagram of the USV’s vertical field of view.

The field of view of the electro-optical visible light sensor is defined as

, and the angular subtense occupied by the target within the field of view is

. The actual image height of the target in the visible light image plane is

, while the pixel height of the entire visible light image is

. Furthermore, the actual physical height of the target is denoted as

, and the distance to the target,

, is acquired via marine radar. The pixel height

of the target can then be calculated through the following formula.

The product of the calculated target pixel height

and the sea–sky line region coefficient

determines the range of the sea–sky line-based target detection region. Sea conditions and navigation state influence the sea–sky line region coefficient

. Under harsh sea conditions and significant navigation turbulence, the value of

is larger; conversely, under calm sea conditions and stable navigation, the value of

is smaller. The introduction of

aims to strike a balance between algorithmic robustness and computational efficiency. The detection region width

can be expressed as follows:

As shown in

Figure 20, the flowchart illustrates the target detection algorithm based on the sea–sky line. The system first performs preliminary target designation via the marine radar, which then drives the electro-optical device to point toward the designated direction. After the process is initialized, sea–sky line detection and position calculation are executed on the first image frame. Subsequently, the system checks two key conditions in parallel: whether the update count has reached its limit, and whether the detection error exceeds a preset threshold. If either condition is met, the process returns to the initialization step and restarts the iteration. This mechanism embodies the algorithm’s adaptive reset capability, designed to prevent error accumulation or ineffective continuous operation. If neither condition is met, the process proceeds to the determination of the precise target area and finally executes target detection based on the sea–sky line. Based on the inherent advantages of the proposed method, it can support real-time processing even under conditions of limited hardware resources.

The primary targets for the USV’s sea trials are buoys and vessels. This study involved gathering data under various weather conditions, maritime states, and time periods, resulting in the creation of a dataset. Throughout testing, multiple data collection campaigns took place, and data screening is carried out based on the efficiency of the collection and the specific circumstances of the test environment.

Figure 21 shows the detection results of the buoy-guided target situation for USVs.

Figure 22 shows the detection results of the ship-guided target situation for USVs.

During the navigation of a USV, minimizing the area of non-target regions in visible light images not only improves the efficiency of image processing but also reduces the false detection rate in target identification. However, under conditions of high navigation speed and harsh maritime environments, an excessively small sea–sky line region coefficient

may cause the designated target to move outside the field of view, resulting in the inability to acquire the target’s center coordinates accurately. As shown in

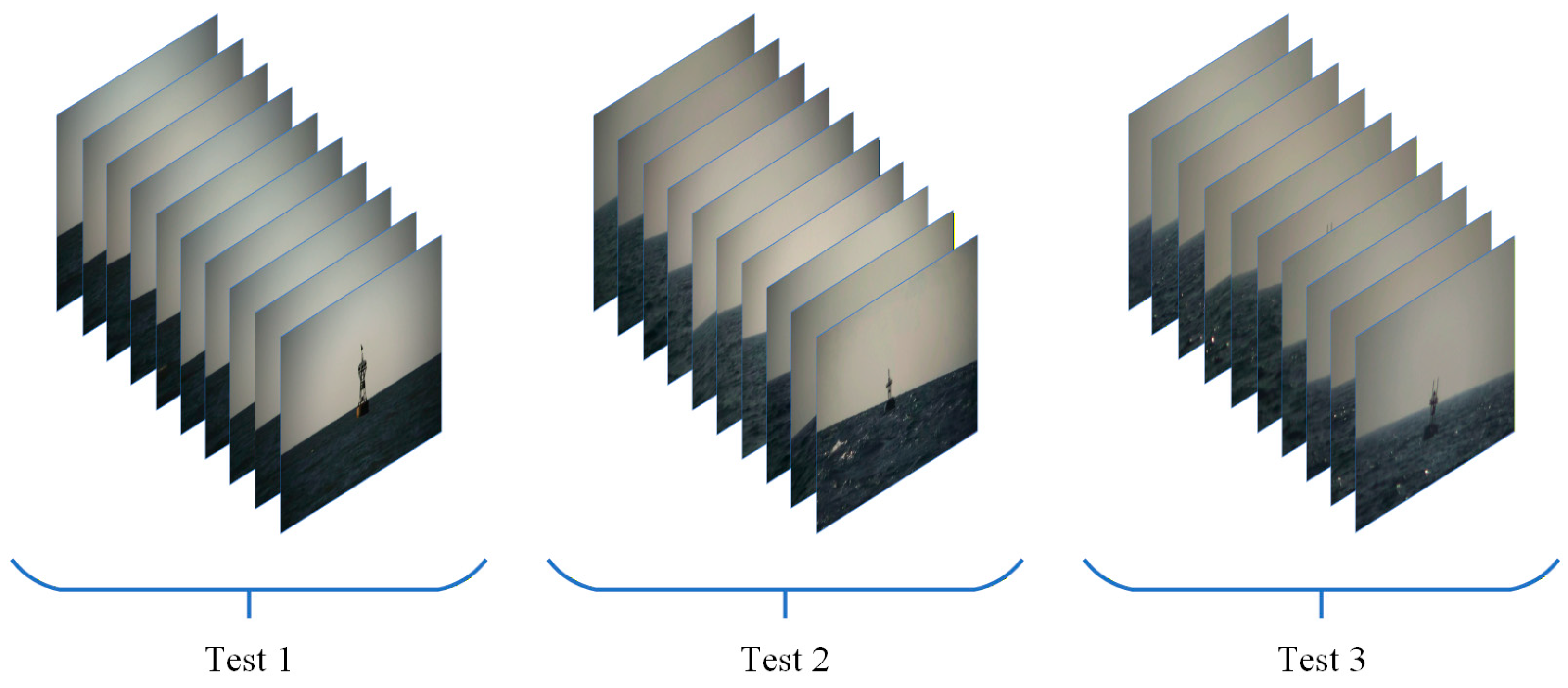

Figure 23, to investigate the relationship between the magnitude of the sea–sky line region coefficient and the target information integrity rate within the field of view, the following three sets of sea trials are conducted in this study.

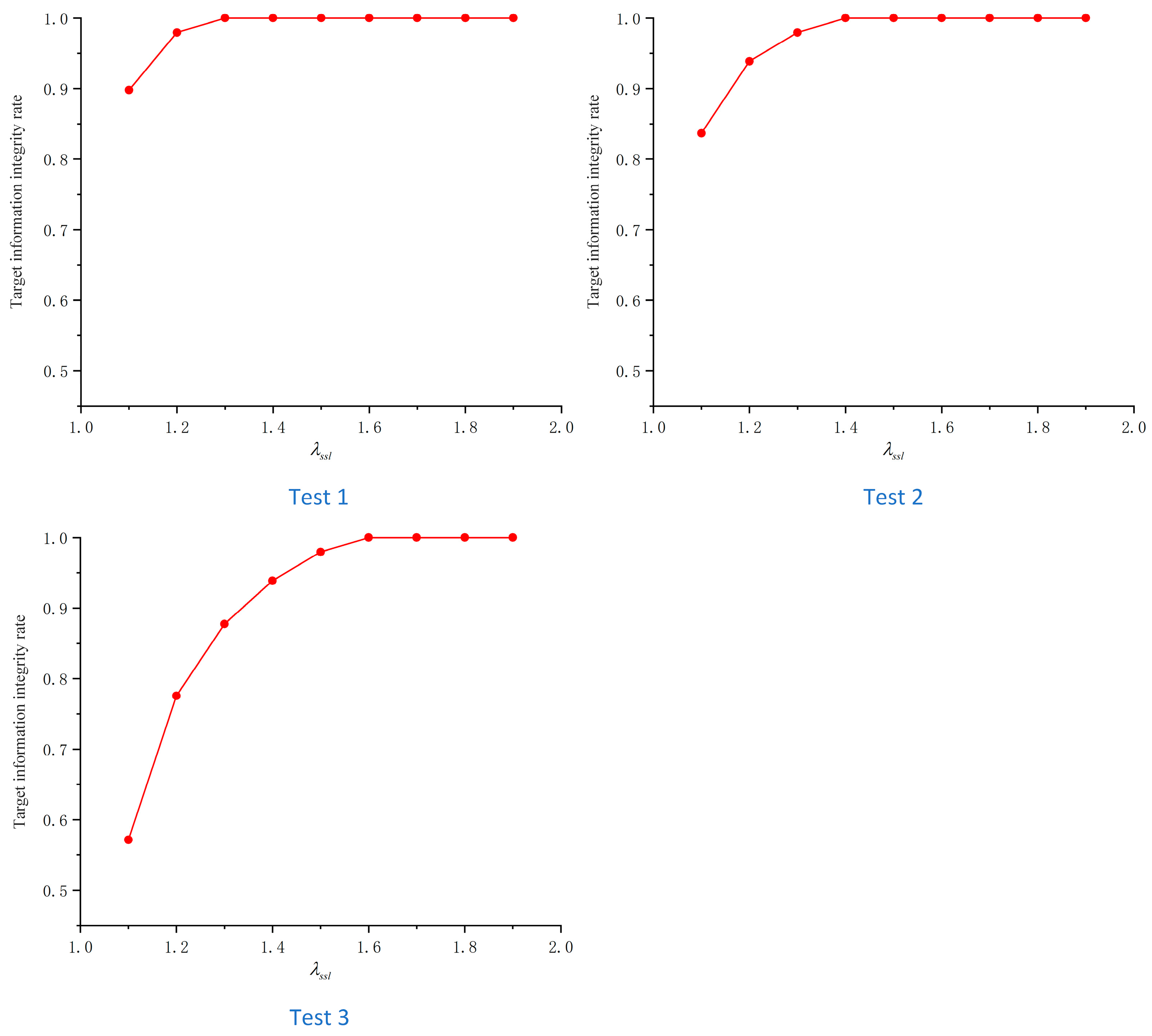

As shown in

Figure 24, the results of the target information integrity rate corresponding to different sea–sky line region coefficients from three sets of sea trials are presented. During the sea trials, the sea–sky line region coefficient

ranged from 1.1 to 1.9, with the aim of investigating the critical value of the sea–sky line region coefficient that achieves a 100% target information integrity rate under different maritime operational environments. Analysis of the test results revealed that the critical value of the sea–sky line region coefficient is smaller under favorable sea conditions and larger under harsh sea conditions. As the sea–sky line region coefficient

increases, the coverage of the sea–sky line region expands, consequently leading to a rising trend in the target information integrity rate.

In the first set of tests, when the sea–sky line region coefficient

is set to 1.3, the target information integrity rate reached 100%. In the second set of tests, when

is 1.4, the target information integrity rate also achieved 100%. In the third set of tests, with

at 1.6, the target information integrity rate remained at 100%. Under the premise of ensuring the target information integrity rate, the effective information ratio of the target should be improved. During these three sets of tests, this study investigated the relationship between the sea–sky line region coefficient

and the effective information ratio of the target. The larger the ratio of effective target information to global information in the image, the higher the detection efficiency and the lower the false detection rate; conversely, the smaller this ratio, the lower the detection efficiency and the higher the false detection rate.

Figure 25 presents the effective information ratio results of the target for the three sets of tests.

Analysis of the test results indicates that, within the value range of the sea–sky line region coefficient , the target information effectiveness ratio of the proposed algorithm demonstrates significant improvement. However, as the sea–sky line region coefficient increases, the target information effectiveness ratio gradually decreases. The first set of tests yielded a maximum target information effectiveness ratio of 8.28%, corresponding to an increase of 4.74%. The second set produced a maximum ratio of 7.56%, an increase of 5.51%. The third set achieved a maximum ratio of 10.57%, reflecting an increase of 6.77%. Enhancing the target information effectiveness ratio requires maintaining the target information integrity rate. Under this condition, the first set of tests achieved a maximum effectiveness ratio of 7%, representing an increase of 3.47%. The second set reached 5.94%, an increase of 3.89%. The third set attained 7.27%, an increase of 3.48%. Overall, the comprehensive results from the three test sets indicate an average improvement of 3.61% in the target information effectiveness ratio.