Abstract

In today’s rapidly evolving economy, organizations increasingly rely on digital knowledge management (DKM) to fuel innovation and improve performance. However, limited research has explored the sequential mechanisms through which DKM practices generate value. This study addresses this gap by proposing and empirically testing a serial mediation model where innovation serves as the central conduit linking three DKM components—(i) Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST), (ii) Digital Knowledge-Sharing (DKNSH), and (iii) Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies (KNUTDTs)—to Perceived Organizational Performance (PERPOP). Drawing on the Knowledge-Based View (KBV), Resource-Based View (RBV), and Organizational Learning Theory (OLT), a multi-firm online organizational survey was conducted using data collected from 245 respondents across 127 service organizations in Kuwait. Validated instruments were used, and analysis involved Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis, followed by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to test the complete digital knowledge lifecycle, beginning from archival storage to innovation and organizational performance. Results reveal that DKM practices do not directly impact performance; instead, their effects are fully mediated by innovation. Four distinct mediation pathways were confirmed, underscoring the importance of integrating digital storage, sharing, and utilization into a unified, innovation-driven process. This research advances the conceptualization of DKM as a dynamic process and highlights innovation as the pivotal mechanism for translating digital knowledge into performance outcomes.

1. Introduction

In the digital economy, knowledge management is becoming increasingly important for corporate performance [1]. With increased competition and technological change, companies need to be able to apply and disseminate digital knowledge to continue innovating and performing better [2]. This shift is particularly evident in service-based economies, where intangible material such as knowledge, skills, and cooperation account for much of the value, as previous studies have shown [3,4]. So, in this context, digital KM methods—storing, sharing, and using knowledge through digital platforms—allow a structured approach for organizations to transform their internal capabilities into innovation results.

Although past research demonstrates the relations among knowledge management (KM), innovation, and performance, it has rarely focused on the step-by-step interaction of KM components in generating strategic value [5,6,7,8]. Most studies focus on individual KM elements and neglect the connectedness of digital knowledge flows that drive innovation and, in turn, increase the performance of the organization. With new tools such as enterprise platforms, customer analytics, and systems based on AI, recent work calls for a rethink about KM models in digital work settings [9,10]. We have to look at KM as a chain of interrelated stages that allow performance, and not as a series of disjointed practices.

Building on this rationale, this research paper highlights its originality through the digital lens of knowledge management by revealing that digital systems transform standard KM procedures into a sequence of interrelated actions that, when combined, enhance performance. Unlike previous studies involving KM–innovation–performance, the current study investigates the direct impact of Digital Knowledge Storage, digital knowledge-sharing, and knowledge utilization using digital technologies as three sequential mediating variables, with innovation as the intervening variable linking these practices to an augmentation in organizational performance. Moreover, this study’s originality also rests on combining the Resource-Based View, Knowledge-Based View, and Organizational Learning Theory. This combination of diverse theories adds to the existing knowledge management literature by showing how organizational learning processes (OLTs) sustain the competitive capabilities resulting from the conversion of digital knowledge resources (RBVs) into competitive capabilities through knowledge processes (KBVs). To carry out this enhancement, this study constructs and evaluates a serial mediation model having an empirically grounded configuration where innovation serves as a bridge between specific digital knowledge management practices (DKNST, DKNSH, KNUTDT) and workplace outcomes (PERPOPs).

Drawing on theoretical foundations from the Knowledge-Based View [3], Recent studies on digital innovation [9,10], Organizational Learning Theory [11,12], and the model illustrates how digital KM practices evolve across the knowledge lifecycle to generate performance outcomes. A field study was conducted to test the proposed model by using the data collected from organizations in Kuwait’s service industry. The study utilized validated measures and data from 245 respondents who were selected among 127 different companies. The analytical methods were Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in order to thoroughly determine the relationships theorized among the latent constructs.

The paper is divided into five major parts. Section 1 entails the introduction consisting of the background, relevance, and aims of the research. Section 2 will be the theoretical background and literature review where the conceptual underpinning will be put in place, and gaps in the existing research will be identified. Section 3 explains the research design and methodology, which involves the data collection procedures, measurement instruments, and the methods of analysis. Section 4 is related to data analysis and results of the EFA, CFA, and SEM are shown. Lastly, Section 5 provides a discussion of the results, including theoretical and practical implications, limitations of the study, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

In a global digital economy, businesses are encouraged to use internal sources of knowledge to innovate and improve performance. This is more pronounced in knowledge-intensive industries, where knowledge management systems related to automated systems also operate as KM systems themselves. This study focuses on digital KM practices to analyze PERPOP (Perceived Organizational Performance) and considers the following three primary theories: RBV (Resource-Based View), Knowledge-Based View (KBV), and Organization Learning Theory (OLT). This captures the essence of knowledge as valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources [13,14]. However, the Resource-Based View has been critiqued for its focus on the possession of resources over use of resources.

To fill this gap, the Knowledge-Based View (KBV) was coined to conceptualize the firm as a dynamic system whose purpose is to integrate and use knowledge [3,15]. rom this angle, knowledge becomes the competitive edge of the firm when it is absorbed and actively employed in the firm’s operations. In relation to this study, KBV delineates knowledge resources as dormant until activated by strategic innovation. Such reasoning is espoused in more recent robust literature which, in its assertion, proved that innovation-driven performance is improved by structured KM practices under the KBV approach [16]. Prior knowledge management-focused studies have shown improved organizational outcomes that stem from innovation-linked pathways available due to these practices [17]. More recent studies highlight this set of outcomes by demonstrating that the KM system improve a firm’s innovation capability and overall performance [9,18].

The SECI model expands the knowledge-based perspective by mapping the following four distinct processes: socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization, which together drive continuous knowledge generation [4]. Each step demonstrates how internal practices and informal working methods at the firm intertwine with documented processes and procedures as the firm sharpens its competencies.

Digital Knowledge Storage, Digital Knowledge-Sharing, and Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies tools, in online environments, apply SECI processes through controlling the movement, transformation, and use of tacit and explicit organizational knowledge. According to newer research, these electronic tools are not simply informational depositories; rather, they improve the flow of knowledge and the corresponding creative problem-solving and innovation capacities of an organization, in accordance with the SECI model [9,10].

Organizational Learning Theory is based on the idea that a cycle of knowledge acquisition, retention, distribution, reinterpretation, and transfer can be attained through five interdependent constituent parts [4,11,12]. In this regard, it posits that authentic progress occurs through ongoing cycles of systematic experimentation, refinement via constructive feedback, and acknowledgment of new insights.

Within this learning theory, organizational transformations posit that in order to achieve real change, the organization must go through shifting cycles of repetitive modifications and rigorous observations until the goal is achieved. When organizational leaders routinely incorporate these learning cycles, the outcome is persistent and structural innovation in the knowledge capital of the firm, which is systematically translated into organizational output.

In this respect, firms with strong dynamic learning abilities are better positioned to convert the inputs of knowledge management into useful outputs [7,19], since there is evidence suggesting that innovation serves as the intermediary between knowledge processes and performance [18]. Building on this framework, the research incorporates aspects from the Resource-Based View (RBV), Knowledge-Based View (KBV), and Organizational Learning Theory (OLT). RBV underscores valuable digital assets, KBV describes the transformation of those assets into capabilities via knowledge-intensive processes, and OLT illustrates how those capabilities are learned, adapted, and refined through processes of learning and adaptation.

The synthesis of these theories extends the research to digital knowledge management systems, which operates as integrated, complex systems where resources and processes, learning and process together drive system innovation and system performance. Innovation: therefore, becomes the key mediator that captures the use of digital KM practices—storage, sharing, and utilization—and reshapes them to system PERPOP. We posit that digital KM systems should facilitate the capturing, sharing, and utilization of knowledge in a manner that nurtures innovation. The mediation logic has been confirmed empirically, demonstrating that performance enhancement occurs only when KM supports an innovation system [20].

This study adds to the body of knowledge by showing the ways in which the assumptions of RBV, KBV, and OLT can be blended and unified into a cohesive explanatory model. The theory conceptually examines four sequential mediation pathways, DKNST → DKNSH → KNUTDT → INNOV → PERPOP. These pathways transform digital knowledge flows into performance within the knowledge economy, describing in detail the processes of contemporary organizations in a performance-driven economy.

2.2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Digital Knowledge Management and Innovation Performance

With the emergence of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, knowledge management (KM) has become a crucial business operation in organizations seeking to develop continuous innovative and competitive advantages [21] DKNST, DKNSH, and KNUTDT belong to the digital KM practices that help companies meet their knowledge-capturing, dissemination, and application objectives in a systematized way. KBV claims that knowledge can only be turned into the most important competitive advantage of the firm when it is fully used and deployed [3,15]. This idea is complemented by the concept of the Organizational Learning Theory, that assumes learning to be the process of acquiring, spreading, and preserving knowledge [11]. Moreover, the SECI model, is the basis of knowledge dynamism owing to socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization [4]. In digital contexts, these dimensions are actualized by KM practices that include DKNST, DKNSH, and KNUTDT.

Earlier research pointed out that DKNST supplemented the long-term reuse of knowledge and proved this with digitally transformed organizations [10,22]. The strategic worth of these repositories has been the subject of discussion [17] and empirical evidence further corroborates this connection [16]. Other work has shown the contribution of ERP and analytics to knowledge preservation and sharing [23]. By contrast, other studies have described how such infrastructure supports the shift toward knowledge-driven innovation, replacing earlier models [9]. This comparative trend illustrates that earlier KM attempts to catalog and store what is now considered knowledge as static assets were performed under the RBV lens, while digital KM regards these resources as fluid, reconfigurable capabilities that evolve through learning under the KBV-OLT linkage. Thus, the fusion of these theories not only contains digital KM much more richly than is commonly performed but also extends available thinking models by clarifying the means through which knowledge resources are mobilized, shared, and transmuted to innovation potential across levels of the organization. All of these are a testament to the belief that practicing digital KM in knowledge-intensive firms is a rationale way to enhance innovation outcomes.

The value of information arises only when it is synchronized with an innovation system [20]. Integrated KM with innovation mechanisms have been shown to significantly improve firm performance [7]. Other researchers argued from the opposite side that technological infrastructure and an innovation-driven culture enhance the impact of KM [19,23]. The impact of KM on organizational performance is emphasized particularly when the applied KM is productive in the development of new products or services [18]. Decision-making knowledge repositories designed to support organizational decision-making have been shown to enhance the innovation climate [24]. Further research concluded that higher KM maturity in an organization leads to better performance results, especially when innovation is used as a conduit for implementing KM efforts [25].

Thes findings affirm the new theoretical advancement of the integrated RBV–KBV–OLT framework argued in this study: digital KM does not just stock knowledge resources, but through organizational learning processes, it dynamically transforms them into innovation-driven performance outcomes. Organizational information systems do not confine knowledge to static repositories but stimulate and impel multilevel organizational innovation through learning and application. This means that innovation is the mediating pivot through which digital KM connects to organizational performance.

2.2.2. Digital Knowledge Storage and Innovation as a Pathway to Performance

Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST) is the process of mentally categorizing and storing forms of knowledge, tacit or explicit, which in turn fosters a remembered, reusable organizational economy [17,26]. Recent studies highlight how the use of Digital Knowledge Storage systems integrated with artificial intelligence and data analysis tools can improve innovation and overall performance in knowledge-intensive companies [9,10]. From the Knowledge-Based View (KBV), knowledge is still an underutilized resource and potential value that must be mobilized to be useful [3,15]. This view is supported by Organizational Learning Theory, which explains that innovations can result when stored knowledge is retrieved and recombined [11,12]. The SECI model describes knowledge as evolving through socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization of increasingly complex systems and cycles of systems [4]. DKNST augments these cycles by supplying the requisite knowledge inputs that must be retained for every cycle of the framework. This means that the innovation process is tied to the firm’s capacity to recontextualize and efficiently use knowledge stored in the firm’s digital systems.

Firms with strong storage capability are said to have better problem-solving skills and more diverse innovation outcomes [5]. Prior studies have shown that the presence of codified knowledge enhances team ideation and innovation collaboration across units [27,28]. Digital knowledge repositories have been emphasized as innovation enablers accessible to frontline staff [29]. Benefits of Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST) are evident in firms that engage in active learning and maintain a strong absorptive capacity [7]. The effect of knowledge retrieval on performance is positive only when it aligns with certain innovation objectives [30]. Within a more limited context, stored knowledge only enhances performance when it is relevant to the practice of innovation [17]. This is also supported by the finding that digital archives ought to be placed at the center of the innovation system if the latent know-how is to be made useful [9]. It has also been noted that the impact of DKNST on performance is only observable when the DKNST efforts are channeled towards innovation [18]. This shows that knowledge storage is no longer regarded as a technical depository of knowledge, but rather as a strategic capability to reconfigure knowledge for innovation and improved performance.

The comparative evidence also shows that the performance gains only happen when the storage is used for innovation-focused purposes. In other words, performance gains only occur when DKNST is used in tandem with innovation-oriented utilization processes. Knowledge repositories contribute to the innovation of decision-making only within the context of a wider learning system [24].

Thus, on its own, DKNST does not create value; without an innovation framework it does not improve organizational performance. Thus, DKNST is a foundational value enabler, whereas innovation is the catalytic mechanism that transforms stored knowledge into usable performance.

Hypothesis 1.

Digital Knowledge Storage positively influences innovation, which in turn positively influences Perceived Organizational Performance.

2.2.3. Digital Utilization as a Mediator Between Knowledge Storage and Innovation

Digital Knowledge Storage DKNST can only be useful when it is used in planning and adjusting decisions. As it has been pointed out in the KBV, knowledge can only generate value through activation within dynamic environments [3,15]. Here, the mediating role is played by KNUTDT (Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies). It has therefore been postulated that knowledge management processes lead to better performance in an organization through efficient leverage of knowledge [31,32]. Rather than relying on early conceptualizations [33,34], recent studies demonstrate that digital systems, including ERP and CRM, facilitate real-time decision support, thereby enhancing innovation capacity in knowledge-intensive contexts [9,10]. It has also been demonstrated that digital knowledge systems enhance innovation speed by providing decision-makers with the correct information precisely when they need it [35].

Moreover, many past studies confirmed that the step that transforms data into innovation outputs is not storage but rather utilization [7,36]. This observation was previously made [17], and it was further supported by empirical relations between AI-enabled utilization and innovation performance [9]. The importance of utilization in the effectiveness of KM has also been noted by past studies [19]. It is further explained that organizational settings with sophisticated digital means of use are more adaptive in terms of innovation and perform better in environmentally volatile circumstances [30,37].

Taken together, these results suggest that innovation does not result from KM inputs as a mere by-product, but as a result of an interactive cycle that utilizes creative application to unlock knowledge in its stored form. These results bolster the KBV argument against the assumption that DKNST and PERPOP are directly related, instead hypothesizing a linear relationship between KNUTDT and INNOV. These results support the KBV-led position that DKNST has a less-than-definitive influence on PERPOP that occurs indirectly and in sequence through KNUTDT and INNOV. The KBV-led argument is further strengthened by this sequential reasoning suggesting that DKNST does contribute to PERPOP, but only through its transformation by KNUTDT and INNOV.

At its core, KNUTDT is the connection between the knowledge maintained in a database and its application for the purposes of innovation. It outlines a KM ecosystem in the digital age which emphasizes agility, feedback, and learning. Innovative outcomes are the result of the use of KM, with innovation as its outcome. Unlike the usual archive-based KM systems, digital systems enable agility, learning, and real-time change; thus, the actual process of utilization is the driving force of innovation outcomes.

Hypothesis 2.

Digital Knowledge Storage positively influences Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies, which in turn positively influences innovation, leading to improved Perceived Organizational Performance.

2.2.4. Digital Knowledge-Sharing as a Mediator Between Storage and Innovation

Digital Knowledge-Sharing (DKNSH) maximizes business value by enabling its rapid spread and collaborative use within and outside the organization. In the SECI model, knowledge creation arises out of the synergy between tacit and explicit knowledge, particularly during the socialization and externalization phases [4]. DKNSH fosters onboarding and information-sharing processes which facilitate cross-silo contacts, interdepartmental collaboration, and knowledge synthesis in digital collaborative environments. These processes exemplify the application of the SECI model in digital environments where DKNSH converts knowledge silos into rich learning environments which promote sustained learning and innovation.

Early contributions pointed out that knowledge integration encourages innovation by fostering innovation from different perspectives and teamwork [27,28]. It has been said that effective sharing systems rely on appropriately designed and easy-to-retrieve storage systems [22,38]. It is also pointed out that DKNST-like storage systems contribute to innovation only when coupled with active sharing systems [7]. More recently, the importance of collaborative digital spaces in expanding innovation and agility in organizations through continuous feedback and collective sense-making has been emphasized [30]. Compared to previous works, this represents a conceptual change from the traditional unidirectional information flow model to a more dialogic and iterative exchange model where sharing is a form of innovation, not simply a channel of communication.

DKNSH tools increase employee involvement during the ideation phase [23]. Knowledge transfer across organizational boundaries is important for innovation [19]. Earlier work noted that while organizational performance is supported by the storage of data, its usefulness is highly contingent upon the culture, and, in particular, the openness of dialog and communication habits that have been established [17]. In the same spirit, there have been studies that underscore the importance of peer knowledge-sharing for improving innovation performance [39].

In the same manner, previous research findings also show that the use of digitally integrated peer-sharing platforms is associated with faster and more consistent innovation in the realization of highly abstract concepts [40]. This body of evidence suggests that sharing serves the function of the social layer of the digital KM, the point of convergence between human and machine interfaces, where interaction and technology integrate to augment the capacity for the co-creation of innovation. Additional evidence suggests real-time knowledge-sharing feedback portals “support innovation outcomes in innovation-driven firms [9].

This argument has further been extended by showing that “well-designed digital collaboration ecosystems foster SECI-informed knowledge flows facilitating greater agility in organizational response to shifting market dynamics [10]. These findings add to the philosophical connection between RBV and OLT: the former focuses on the available resources in technology and infrastructure, while the latter on the priceless processes of experiential and collaborative learning resources.

Taken together, this research shows that digital knowledge-sharing systems act as vital conduits connecting dormant, passive repositories of knowledge to active, dynamic applications of knowledge. Unlike earlier manual, or print-based systems, modern digital tools offer uninterrupted, instantaneous, and group-wide knowledge dissemination and sharing through mobile devices, social media, and fully enabled cloud-based conferencing services.

Hypothesis 3.

Digital Knowledge Storage positively influences Digital Knowledge-Sharing, which in turn positively influences innovation, leading to improved Perceived Organizational Performance.

2.2.5. An Integrated Mediation Chain: From Storage to Innovation via Sharing and Utilization

The proposed mediation pathway views digital knowledge management (DKM) as a continuous flow, segmented into the following interconnected steps: Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST), Digital Knowledge-Sharing (DKNSH), and Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies (KNUTDTs). These lead in succession to innovation (INNOV), which in turn enhances Perceived Organizational Performance (PERPOP).

This structure excels beyond the linear perspective of knowledge management, treating innovation as a cumulative product derived from a series of disengaged digital activities, each of which initiates the subsequent one. Within this framework, these activities are interwoven into a self-reinforcing cycle of advanced learning processes. Digital technologies enable real-time knowledge-sharing, and application through collaborative systems, unlike traditional knowledge management models which focus on inactive recording and offline processes. This integrated model is consistent with both the Knowledge-Based View elaborated on earlier [3,15] and Organizational Learning Theory as defined and elaborated upon in the foundational studies [11,12]. These theories emphasize the importance of value creation through knowledge-sharing, internalization, and strategic use of knowledge. This study integrates RBV’s resource orientation, KBV’s process logic, and OLT’s adaptive learning emphasis to shift earlier theoretical models from possessing static resources to enabling dynamic capability activation through digital mediation.

Studies have shown that digital dissemination processes augmented with analytics tools greatly increase the power of knowledge [19,41]. It is further asserted that the power to instrumentalize knowledge is back-gated to the prior knowledge distribution [7,36]. The use of interlinked digital ecosystems fosters the application of convergence of common knowledge with the processes of innovation by strengthening feedback loops and enabling boundary-spanning inter-institutional communication [30]. This comparative understanding highlights that innovation is not a singular construct, but the systemic result of simultaneous retention, sharing, and use of knowledge within a socio-technical system, processed as an integrated system.

Further study prove that innovation performance is greatly enhanced with the incorporation of DKNST, DKNSH, and KNUTDT within an entire pipeline [42]. Similarly, other studies have shown that innovation output greatly increases when storage systems are part of the KM process [17]. Further, it has been shown that within agile organizations, participative innovation is fostered by digital tools designed for knowledge communication and application facilitation when used agilely [23]. This evidence suggests that the orchestration of DKNST, DKNSH, and KNUTDT has put to use focused orchestration that is primarily aimed at multiplying the innovation outputs instead of the addition of innovation outputs, thereby strengthening the case for serial mediation.

Moreover, the described sequence has been substantiated through empirical studies, which show that the spatial KM systems reinforced the impact of innovation multifold through the storage, sharing, and application layers of the system [9]. This assertion was also supported by research which demonstrated that the integration of technology-enabled KM system improved knowledge agility and knowledge delivery system [10]. This, in turn, strengthens the proposition that enduring creative strength is fueled by the integration of a knowledge management system, rather than a disjointed system of tools, fragmented insights, or disparate strokes of ingenuity. The integration of RBV, KBV, and OLT frameworks and the model of innovation complexity systemically connects resources, knowledge, and learning as processes of digital innovation. Collectively, wll these findings suggest that knowledge and innovation are not directly correlated as often perceived, but instead connected systemically through digital programmable pathways that process stored information to derive innovation.

Hypothesis 4.

Digital Knowledge Storage positively influences Digital Knowledge-Sharing, which positively influences Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies, leading to innovation, which ultimately enhances Perceived Organizational Performance.

2.3. Synthesis and Research Gap

The literature review corresponding to each of our constructs is instrumental in positioning our paper. To this end, we also created a analytical table summarizing the aforementioned papers for the readership (Appendix A). The proposed model has a high degree of theoretical and empirical support, integrating DKNST, DKNSH, and KNUTDT with PERPOP, with INNOV as the central mediating variable. Foundational studies have shown that processes of knowledge management (KM) has a marked effect on an organization’s innovation and strategic performance [18,27,28]. From a theoretical standpoint, it has been argued that knowledge must be systemically organized before it can be leveraged as a competitive asset [3,15]. The Organizational Learning Theory [11] and the SECI model support the notion that knowledge much be increasingly transformed, shared, and applied to generate sustained value [4]. The views expressed in these frameworks have, to a large extent, established that, unlike traditional repositories, digital knowledge flows in a kinetic manner through a networked or interlinked system of storage, sharing, and utilization to achieve performance results.

There has been an ongoing debate claiming that innovation persistent within knowledge management (KM) practice needs to be incorporated as an integral part of practice, not an afterthought [7,17]. Evidence to the contrary has recently emerged, demonstrating that innovation-focused business performance is driven by well-designed KM processes viewed through the Knowledge-Based View lens. Critically, this perspective highlights the importance of digital and other channels of KM in rapidly changing markets [16]. This has been corroborated by studies documenting digital asset clouds, sharing portals, and retrieval platforms as definable, quantifiable channels in which ideas are transformed into outcomes [9]. The degree of the integration of digital tools within the workflows of employees is still an indicator of successful innovation [29]. In the same breath, other scholars noted the importance of digital KM infrastructure in structuring learning processes as a way to organize value creation [36].

Most prior research has focused on these dimensions of the KM process in isolation rather than as a sequential, interdependent stages, where coordinated sharing and application transforms knowledge on hand into innovation. AI-enabled KM systems, combined with real-time analytics, promote knowledge agility, streamline innovation activities, and enhance organizational performance [10]. However, research continues to focus on the process of knowledge management repetition and the digital continuous cycle from knowledge retrieval to innovation and performance remains largely ignored.

The lack of integrative, process-oriented KM frameworks that connect the individual, organizational, and techno-structural components has been identified as a major shortcoming [19,41]. In this regard, this research addresses this gap by empirically testing a full-cycle, multi-stage mediation pathways anchored in RBV, KBV and OLT. It is one of the first to explain in detail how digital knowledge systems transform static data into innovation-oriented performance at the organizational level.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Model

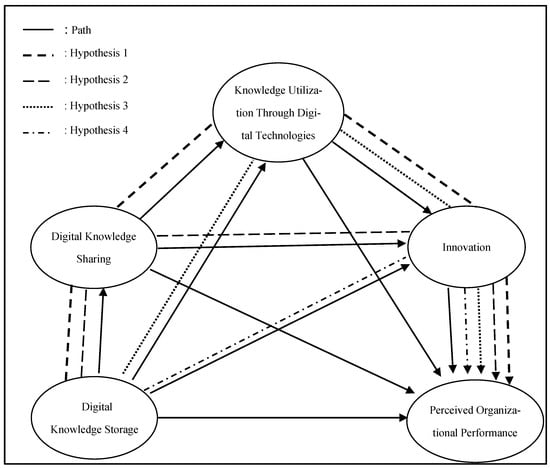

This study proposes a sequential mediation model, grounded in key knowledge and learning theories, as illustrated in Figure 1. The model encompasses four distinct yet interrelated pathways.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

DKNST → INNOV → PERPOP

DKNST → KNUTDT → INNOV → PERPOP

DKNST → DKNSH → INNOV → PERPOP

DKNST → DKNSH → KNUTDT → INNOV → PERPOP

These pathways derive from the foundational assumption that knowledge must be applied strategically to create value [3,15].It has further been noted that learning mechanisms facilitate the understanding and retention of information, thereby supporting the innovation process [11]. The SECI model posits that innovation arises from the interplay of tacit and explicit knowledge during the processes of socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization [4]. Collectively, these arguments indicate that knowledge is not simply given; instead, through innovation mechanisms, strategic mobilization drives organizational performance. Thus, the model illustrates how digital KM enhances performance through innovation. Each pathway sheds light on a different, stored knowledge-driven innovative practice and the transformation of performance outcomes.

Based on theoretical implications and empirical evidence from the literature, the authors generated the conceptual model presented below to test the hypotheses developed for this study.

3.2. Study Sample

Given that Kuwait is a high-income country with a predominantly oil-centric economy, the services sector plays a significant role in the country’s economic landscape [43]. Acknowledging this importance, service industry employees in Kuwait were determined as the research population in this study. Data were collected from employees working in the services industry in Kuwait using convenience sampling, which is often preferred for its efficiency, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness [32].

Kuwait, recognized globally as one of the wealthiest nations, has historically relied heavily on its vast oil reserves as the primary driver of its economic prosperity. However, beyond hydrocarbon production, the services industry is increasingly vital for sustainable economic development and diversification [44]. This growing importance is underscored by its substantial contribution to the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), reflecting a strategic shift towards a more diversified economic base [45].

Crucially, the Kuwait Vision 2035 program, “New Kuwait,” places significant emphasis on fostering a knowledge-based economy driven by innovation and a robust services industry. This national development plan aims to transform Kuwait into a regional financial and commercial hub, necessitating substantial growth and modernization within various service sub-sectors, including finance, tourism, logistics, and information technology [46]. Such diversification is critical for creating new employment opportunities, attracting foreign investment, and ensuring long-term economic stability in a global landscape increasingly focused on non-oil revenues. The strategic focus on the services sector is thus not merely a supplementary income source but a foundational pillar for Kuwait’s future economic resilience and global competitiveness [25]. This profound and growing significance is precisely why the services industry in Kuwait was chosen as the sample for this research.

3.3. Survey Instrument

The instrument used in this research was a self-administered questionnaire comprising thirty-five items. Of these, five focused on gathering basic demographic details. The remaining questions aimed to measure three primary constructs: knowledge management processes, innovation, and overall performance.

The research framework incorporated three digital knowledge management constructs: Digital Knowledge Storage (DKST), Digital Knowledge-Sharing (DKSH), and Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies (KUTDTs). These dimensions were originally operationalized to assess traditional knowledge storage, sharing, and utilization [17]. The measures were confirmed as reliable in later work [47] and more recently refined for a digital context [32].

Although digital technologies are commonly embedded in organizational operations, their strategic use for managing and applying knowledge varies widely across firms. In this study, Digital Knowledge Storage, Digital Knowledge-Sharing, and Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies are conceptualized as digital extensions of core knowledge management processes [6,39,47]. This approach builds on prior findings that effective knowledge utilization significantly enhances organizational performance [32,39]. In this regard, our constructs assess how digital tools enable the organization to store, disseminate, and apply knowledge, rather than measuring their routine operational use. This distinction reflects recent perspectives emphasizing that digital transformation does not eliminate the need for knowledge management; instead, it amplifies the importance of effective digital knowledge processes for sustaining organizational learning and performance [48]. These dimensions were originally operationalized to assess traditional knowledge storage, sharing, and utilization [17]. The measures were confirmed as reliable in later work [49] and more recently refined for digital context [32].

Knowledge storage was operationalized using a six-item scale [17]. Besides this study, some past studies also borrowed and/or refined those items for their research [22,38]. Respondents were asked to rate how effectively the organization utilized digital systems to store knowledge and how successfully those systems maintained the stored information as relevant and up-to-date.

For knowledge-sharing, a seven-item scale was employed [17]. Recent studies have provided information that guided the adaptation of these items [23]. The revised questions now assess how effectively digital communication works both within organizations and between them.

The original knowledge utilization scale included six distinct statements; these statements were revised to focus specifically on how digital technologies support the application of knowledge [33,34,48]. The innovation (INNOV) construct was measured following an established framework [29], while the Perceived Organizational Performance (POP) items were adapted from a validated scale [25]. All scales used a five-point Likert format, asking respondents to rate their level of agreement, where one signaled “Strongly Disagree” and five indicated “Strongly Agree”.

3.4. Data Collection

Questionnaires were sent to available and consenting employee representatives who could be reached quickly and who had been approved by their employers. Researchers gathered responses either in person or through online platforms, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms. Approximately 1000 employees from 250 private and public companies were targeted. Of the distributed questionnaires, 245 usable responses were received from 127 different companies. The return rate was thus calculated to be 24.5%, an acceptable rate for multi-firm, online organizational surveys from key informants.

The participating organizations represented various service industries, including finance, consulting, IT, healthcare, education, logistics, and hospitality. Although several respondents were from knowledge-intensive business services (KIBSs) organizations, the sample was not limited to this subgroup, allowing for a broader view of service-sector practices.

3.5. Analysis

IBM SPSS (version 27) and IBM SPSS AMOS (version 23) software were employed to analyze study data. Data screening, preparation, descriptive analysis, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and reliability analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Path Analysis were completed with IBM SPSS AMOS.

4. Results

4.1. Pilot Study

To test the adapted measurement tools and investigate any potential structural issues, a pilot study was conducted with 100 participants prior to the main study. Each construct included in the model was examined separately with an EFA. Principal component analysis with the Varimax rotation method was employed in each EFA. Table 1 shows the test results for each construct included in the research model.

Table 1.

EFA suitability results for study constructs.

A significant Bartlett’s test result means the data is suitable for factor analysis, and KMO values above 0.7 can be interpreted as middling (0.7 to 0.8) and meritorious (0.8 to 0.9), which are well above the acceptability threshold of 0.5 [50]. In this study, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test values were above 0.7, and Bartlett’s test results were significant for all constructs.

After confirming the suitability of the analysis, items and factor loadings were examined to determine whether any items needed to be removed or retained. Three items from “Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies,” two items from “Digital Knowledge Storage,” three items from “Digital Knowledge-Sharing,” two items from “Innovation,” and two items from “Perceived Organizational Performance” were dropped due to low factor loadings or collinearity issues. The final study questionnaire retained 18 of the initial 30 questions.

The internal reliability of the study’s constructs was examined through Cronbach’s alpha tests. Test values between 0.70 and 0.95 are considered acceptable [51]. In this study, the test results ranged between 0.831 and 0.892, indicating good internal reliability. Based on these findings, the study questionnaire took its final form, and the researchers proceeded to collect the primary data for the study.

4.2. Sample Characteristics

Following the collection of study data, a descriptive analysis was performed to reveal the sample’s characteristics. The study sample consisted of 245 participants who were employed in the Kuwait service industry. A summary of the characteristics is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

The respondents represent a diverse range of positions involved in knowledge-related activities within their organizations. The largest group, previously labeled as “Other (Employee),” has been redefined as “Operational KM Representatives” to reflect their actual roles. These individuals, while not holding managerial titles, are actively engaged in knowledge-related tasks such as information management, data sharing, and process improvement within operational units (e.g., IT, customer service, logistics, and analytics). Their inclusion provides a broader understanding of how knowledge management processes operate across hierarchical levels in service organizations

Considering gender, the participants’ gender ratio was almost balanced, with a slight advantage in favor of women (52.2%) compared to men (47.8%). The majority of the study participants graduated from a four-year undergraduate program (70.2%). A quarter of the total sample held a graduate degree (25.7%), while a small number had only high school education (4.5%). When asked about their work position, most participants reported working as employees (66.1%). Experts (9.8%), middle-level managers (19.6%), and directors (4.5%) formed the remainder of the participants.

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

As the second step in the study, the measurement model was tested with a CFA. No problems were diagnosed with the model, and all the study items were retained. Detailed information regarding questionnaire items from both the pilot study’s EFA and CFA are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Questionnaire items: EFA, CFA, and reliability results.

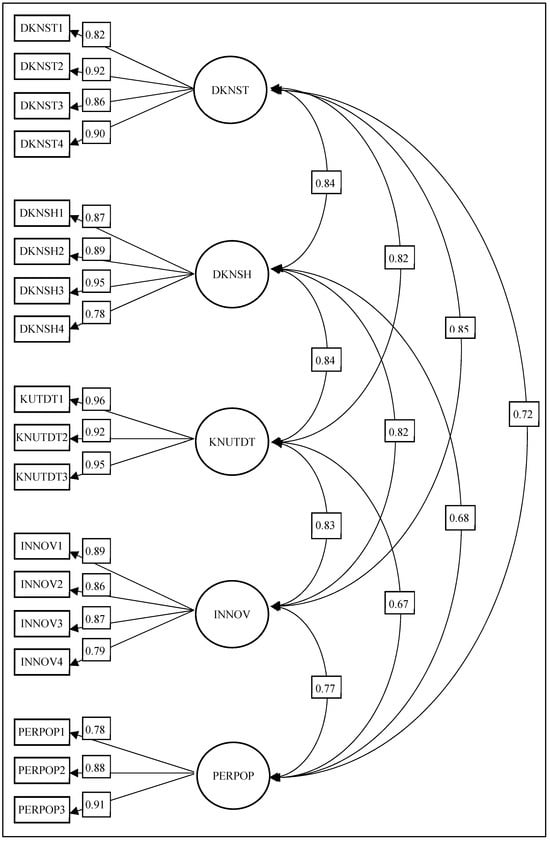

The latent and observed variables are presented in Figure 2, along with their related standardized regression weights and correlation values.

Figure 2.

Measurement model.

Results from several goodness-of-fit tests were examined to assess the fit between the measurement model and the research data. The result from χ2/d.f. was 2.354. A value of 5 or lower is interpreted as a sign of acceptable fit for this test. The other goodness-of-fit test results examined were GFI = 0.882, AGFI = 0.839, TLI = 0.956, CFI = 0.964, RMR = 0.047, and RMSEA = 0.074. These numbers indicate that the model has an acceptable fit with the data.

The next step in the analysis was to examine the reliability and validity of the constructs. Table 4 presents the outcomes of the reliability and validity assessments. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α and composite reliability computations. Cronbach’s α values varied from 0.893 to 0.960, while composite reliability values ranged from 0.895 to 0.960. A score of 7 or above is considered indicative of dependability for both assessments [52].

Table 4.

Results of validity measures.

All constructs exhibited AVE values exceeding 0.5. Moreover, all AVE values exceeded the computed values of variance shared with the other study components. The findings demonstrate a robust relationship among the variables as indicators of the same latent concept, and the constructs within the model exhibit enough differentiation, hence supporting evidence for both convergent and discriminant validity. The Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio was analyzed as an additional measure of discriminant validity. A score below 9 is indicative of satisfactory discriminant validity [53]. The HTMT ratio values for the study constructs are presented in Table 5. All values are beneath the threshold of 9, further substantiating discriminant validity.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–Monotrait ratios.

Common Method Bias (CMB) is a potential threat to social research and an important issue that requires inspection. Harman’s single-factor test is one method that is used to detect CMB’s existence. Results revealed no single factor that explains at least 50% of the variance. This finding implies that CMB does not threaten the study.

4.4. Path Analysis

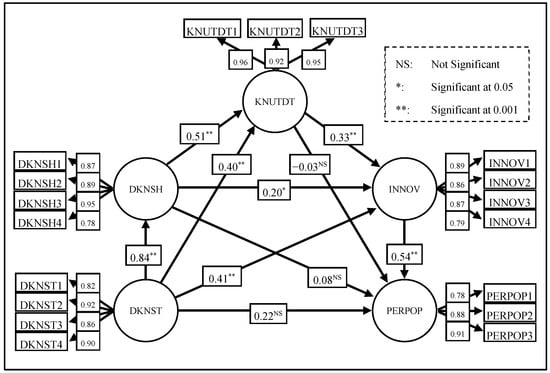

The path model and path coefficients are shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Path model.

Path model goodness-of-fit values for selected indicators emerged as χ2/d.f. = 2.354, GFI = 0.882, AGFI = 0.839, TLI = 0.956, CFI = 0.964, RMR = 0.047, and RMSEA = 0.074, implying an acceptable fit between the model and the data.

The direct relationships between constructs were all statistically significant except for DKNST and PERPOP, DKNSH and PERPOP, and KNUTDT and PERPOP. This is a clear indication that any influence of a digital knowledge management-related construct on organizational performance has to occur through innovation. It also strengthens the ground of the mediation hypotheses developed in this study, as no direct influence exists. Based on this finding, bias-corrected bootstrapping was performed to reveal the nature of mediation effects between the study constructs with 1000 samples and a 95% confidence interval. This method was chosen due to its accuracy in generating confidence intervals and statistical power [54]. The results from these analyses are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Direct relationships and mediation results.

Based on the results presented, all hypothesized relationships are supported. While direct effects of digital knowledge management components on performance are not significant, the full mediation via innovation confirms the proposed sequential pathways and validates all hypothesized indirect effects at statistically significant levels.

5. Discussion

5.1. Hypothesis Testing Results

- H1: Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST) → Innovation (INNOV) → Perceived Organizational Performance (PERPOP)

The results indicate a clear but measured indirect effect of Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST) on Perceived Organizational Performance (PERPOP) through innovation (INNOV) (β = 0.23, p < 0.001). This is in line with the KBV theory which posits that the monetary and strategic value of an asset is only realized when that asset is properly deployed and utilized [3,15]. Similarly, in Organizational Learning Theory, innovation is not possible without organizational memory being proactively converted into practices [11,12].

It has been suggested that knowledge repositories can facilitate creative problem-solving and thus improve innovation [5]. Other studies have shown that within organizations, encoded knowledge enhances the rate of innovation [27,28]. A classic example is the work of one of the early scholars in this field, who hypothesized that certain storage systems perform as innovation resources rather than general performance boosters [17]. Furthermore, it has been shown that certain digital storage infrastructures foster innovation driven from the frontline [29]. Other work has shown that DKNST is linked to absorptive capacity and organizational learning culture, as DKNST is related to inflow and outflow strategies of knowledge [7].

Recent studies have highlighted the need to focus on knowledge retrieval in the context of innovation objectives [30]. More positive results have been found when the focus is on the storage and innovation strategy alignment [42]. On the other hand, it has been observed that the storage of knowledge, without activation, results in the underutilization and stagnation of such resources [55].

In response to these findings, more recent research has proposed that innovation acceleration is delivered by storage systems enhanced by AI due to their high-precision alignment and objective-directed access to organizational goals [9]. In the same way, it has been argued that more positive outcomes may come from the so-called formally constructed and retained knowledge arising from systematic digitization and innovation focus [10]. Ultimately, it seems that knowledge management investments, particularly those focusing on organizational interdependencies, may lead to innovation and, therefore, sustained long-term organizational performance [16]. All these studies prove that DKNST is significant to performance when it leads to innovation.

- H2: DKNST → Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies (KNUTDTs) → INNOV → PERPOP

This pathway’s effect (β = 0.07, p < 0.05) indicates that even stored knowledge as an organizational asset has intangible organizational value that can be leveraged via digital technologies. Knowledge is said to provide competitive advantage only when it is actively leveraged, deployed, and framed within the context for which it was conceived [3,15]. Differentiation is the process of activating dormant knowledge concentrating computing resources through ERP, CRM, or business analytics tools [33,34].

Enhancement of a firm’s agility towards innovation through digital platforms, as ascertained by other authors, is equally available [35]. There is also empirical data asserting that innovation is fostered through the use of digitally enhanced passive repositories [7,36]. Integration of digital tools within workflows has also been noted to be fundamentally strategic rather than the tools per se [6,20].

Utilization is the primary linkage between knowledge management practices and the consequent innovative outputs [19]. The acceleration of feedback loops and digital resource enhancement to improve decision-making is a more recent innovation [30]. It has also been shown in earlier research that the activation of knowledge through digital engagement has a direct impact on innovative outcomes [56].

In support of these insights, it has been claimed that knowledge-sharing portals with real-time feedback systems significantly improve innovative results in knowledge-intensive work [9]. This argument has been extended by showing that well-designed digital collaboration ecosystems allow SECI-informed knowledge flows to be distributed faster and more flexibly, enabling agile responses to rapid shifts in market dynamics [10]. Research shows the digital knowledge-sharing infrastructures perform as essential links, connecting still archives with knowledge-in-action. These flexible archives are made possible by digital technologies that integrate horizontal and vertical streams of knowledge and actively engage users in collaborative knowledge creation practices at anywhere and at any time.

- H3: DKNST → Digital Knowledge-Sharing (DKNSH) → INNOV → PERPOP

The mediation effect (β = 0.09, p < 0.05) through DKNSH highlights knowledge-sharing as an important channel between storage and innovation. As described in the SECI model, knowledge is created through the interplay of tacit and explicit knowledge, especially through socialization and externalization processes [4]. Subsequent research has shown that sharing fosters organizational learning and improves innovation [57]. Digital sharing platforms enhance integration across silos and foster ideation [19]. In the same way, digital collaborative platforms improve the volume and velocity of sharing [23,27] and well-designed repositories improve dissemination [22,38].

Active sharing mechanisms can lead to innovation when paired with properly organized knowledge-retention systems [7]. Workspaces that offer and encourage ongoing feedback innovate both processes and products, making it more fluid and dependable [30]. The culture of the organization does underpin knowledge-sharing, though a more digitally open culture tends to enhance performance [17]. As a result, in a fully digital workplace, knowledge exchange is often viewed as foundational to innovation [58].

AI and analytics can shift routine sharing to real-time co-creation, enabling faster turnover of ideas. Some of the most recent research supports this by showing that joint uploads of data and lessons from different departments speed up collective learning and improve innovation at all levels [10]. Sharing involves more than just the absence of barriers, it includes the cultivation of inter-organizational action necessary to articulate the desired outcomes of entities [16]. Taken together, these results suggest that the DKNSH framework is an important moderating factor in the relationship between stored knowledge and performance driven by innovation, although ownership of these concepts may vary within the organizational setting.

- H4: DKNST → DKNSH → KNUTDT → INNOV → PERPOP

The observed serial mediation effect (β = 0.08, p < 0.05) illustrates how stored knowledge is shared and used before influencing innovation and organizational performance. Competitive advantage is reached only via seamless, boundary-crossing flows of knowledge [6]. Previous research has already pointed out that knowledge vaults elusive departmental and silo-based KM systems stagnate unless siloed to a higher-level unifying framework [20].

Aligned with these findings, earlier research has also shown that creative output is more likely sustained when knowledge repositories are embedded and linked to utilization systems [19,41]. Contemporary studies captured in the literature highlight that having a digitally integrated digital ecosystem of knowledge management fosters tangible outcomes when pervasive to beginner workflows in organizational routines [56,58,59].

Purposefully designed knowledge acquisition and sharing, when actively used through digital platforms embedded in cyclical systems of full-cycle KM systems, tend to generate more fragmented outputs in terms of innovative and creative outcomes [9]. Creative outputs augmented by augmented artificial intelligence leads to multiplicative gains when actions are monitored, insights surfaced, and behaviors adjusted [10]. In alignment with the previous body of research conducted, it is noted that construction of knowledge flow polygons with boundaries tend to encourage bursts of innovation and creativity, unlike their counterparts that are streamlined to fragmented isolated stages [16]. In contrast, fragmented and uncoordinated KM may limit idea generation and gradually reduce competitive advantage.

Overall, these findings suggest that an integrated cycle of digital knowledge activities enhances innovation capability and supports sustained performance, while acknowledging that further evidence is needed to generalize these effects across different organizational settings.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The study adds to the KBV and Organizational learning Theories by analyzing the interrelation and sequence of the storing, sharing, usage, and innovation of the stored knowledge, and documentation of knowledge. It reinforces the fundamentals of the KBV [3,60,61] by establishing the fact that knowledge, especially knowledge in the digital form and the knowledge which is frequently and actively managed and used, is an asset of the organization not just in its reserved form (storage) but in its activated form (utilization and sharing) and when transformed into innovation [62]. Also, it supports the Organizational Learning Theory [63], as knowledge, which is an organizational memory, in this case, DKNST, must be processed and integrated into the practice (KNUTDT, DKNSH) to result in sustainable innovation and improvement of work [64]. Therefore, this study does not change the theory, but rather refines it by focusing on the order and the processual character of digital knowledge activities.

The outcomes of this study align well with the literature on knowledge management (KM), particularly on the positive relationships between KM processes and organizational outcomes [31,32]. Systematic and structured processes such as knowledge storage, dissemination, and application within an organization are relevant to the organization’s innovativeness and innovation performance [65,66]. As a result, the study expands the literature by confirming that these mechanisms apply to digitally enabled service firms, although their relative strength and impact vary by context. The contribution to theory remains the validation of digital knowledge management as multi-phased and interdependent, dual in its increasing practice as ‘silos’ and ‘in sequence’ rather than as practiced today. The validation of serial mediation chains in the study provides a cohesive framework of these interwoven aspects of knowledge management: storing, sharing, reuse, and re-innovation in a digitally immersed environment.

The existing theory is expanded by showing that the process of digital knowledge management is multi-faceted, interdependent, and more practiced in parallel rather than as a sequence of siloed activities. The verification of serial mediation chains in this study provides an interrelated, integrative structure that illuminates compartmentalized aspects of KM in a digitally woven KM ecosystem, such as storing, sharing, utilizing, and innovating. This is a marginal contribution which is more process-integrative than a radical re-thinking.

Furthermore, there is empirical evidence supporting the importance of innovation as a mediator through which the DKM processes improve organizational performance [32,67]. This mediation, nevertheless, should be viewed as dependent on the level of digital readiness and organizational learning capacity as opposed to a one-size-fits-all approach. These findings are consistent with the literature that underscores innovation as the corner stone in optimizing returns on KM investments [68,69].

Moreover, the research mentions the importance of the “digital” components of knowledge management. This coincides with some of the more recent research outcomes [70,71]. This research extends the application of KBV and OLT orientations by contextualizing them within the digital environment, though modestly, demonstrating how digital infrastructures operationalize theoretical constructs rather than redefining them. The focus on storage, usage, and sharing of knowledge within KM from the digital perspective underscores the need for incorporating digital tools and technologies in KM models for performance improvements.

5.3. Practical Implications

The findings help the management and the heads of organizations in decision-making. In particular, innovation in DKM systems should go beyond basic storage or access capabilities and be designed specifically to support innovation pipelines. DKM systems should enable the generation of new ideas, support experimentation, and facilitate the rapid deployment of knowledge into products and services. These recommendations, however, pertain mainly to service organizations in advanced stages of digital development.

Organizations should realize that investing in digital knowledge structures, such as knowledge storage, sharing, or knowledge utilization, in silos is unlikely to bring any substantial gains in performance. Knowledge management (KM) systems should rather focus on capturing and assisting with ideation, experimentation, and refinement along with the rapid deployment of knowledge embedded in products, services, or processes. These processes are aligned towards a learning organization and are not rigid system designs.

The results are also a reminder of the necessity to integrate DKM systems across boundaries to eliminate ‘data silos’ and integrate capturing, sharing, and using knowledge. However, organizations will stop promoting learning if such integration is perceived as rigid documentation and reasoning calculated in standard procedures manuals. For the time, an understanding of such rigid record-keeping would elucidate and compel practitioners to integrate digital knowledge repositories with collaborative and response-boosting analytics.

Knowledge-friendly cultures go hand in hand with collaboration and system knowledge applications such as ERP, CRM, analytics, and AI. These behaviors can be targeted and entrenched using reinforcement learning and incentive schemes. On the other hand, the social side of knowledge management cannot be ignored. This involves fostering a culture of trust and collaboration in permitted silos, enriched with digital tools that promote knowledge-sharing. These behaviors should reflect the organization’s culture and technological stance rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Artificial Intelligence remains a crucial component in the integration of digital knowledge management. Emerging trends with Knowledge-Sharing Systems demonstrate a shift toward investing in advanced technology to boost Knowledge Delivery Systems, feedback loop systems, and real-time collaboration. Other systems that synthesize AI and Big Data Analytics may further improve the effectiveness of DKM. To build and sustain competitive advantage, modern firms must integrate the acquisition and utilization of proprietary technological and non-technological resources. For flexible, real-time utilization, organizations require knowledge management systems that are shared and leverage technologies that promote and facilitate knowledge-sharing and collaboration. Particular attention should be given to the integration of systems and the alignment of cross-functional activities so that stored knowledge is used to feed continuous workflows of the funnel and innovation pipelines. Furthermore, the effectiveness of KM investments can be enhanced through training programs that promote a culture of digital collaboration and thought experimentation.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

It should be noted that the findings primarily reflect incremental forms of innovation commonly observed in service organizations and should not be generalized to all types of innovation or KM systems. The results indicate tendencies rather than universal effects, suggesting the need for further validation in diverse organizational and technological contexts.

Despite its contributions, there are some limitations which could be addressed in future research. The most important of which is using self-reported data as the only method of measuring perceived performance. While such practice is common in organizational behavioral research, it opens the door to possible subjectivity. Such limitations can be mitigated in future research by including performance indicators that are less subjective, including indicators of financial performance, or even innovation performance.

The second limitation concerns the area of data collection with respect to geography and culture. In the case of the present research, the data were obtained from organizations in Kuwait. To increase the generalizations of the findings, future research should incorporate cross-culture sampling and perform more sophisticated analyses. This would enhance the comprehension of the proposed construct with respect to varying culture and economic conditions. Additionally, this research analyzes exclusively the service sector. It is not clear how these outcomes would apply to other sectors of the economy or other types of organizations. Future research may analyze the same variables in other sectors to test the relevance of the construct in diverse settings.

Closely connected to this is the fifth limitation, pertaining to the treatment of innovation and its complex nature. This study did not disaggregate the types of innovation for analysis. Future research may examine the impact of DKM on different varieties of innovation—radical versus incremental, or process versus product, and the extent to which the mediating structures in these cases differ.

Moreover, this research has overlooked situational matters such as the organization’s type, scale, and culture. Future efforts might investigate how such factors serve as moderators in the interplay between DKM, innovation, and performance, thereby elucidating the conditions in which DKM efforts produce the greatest value.

More importantly, if the research is largely correlational and quantitative in design, the inclusion of other qualitative methodologies, such as interviews or case studies, would serve to strengthen the research. These methodologies would elucidate the ways DKM drives innovation and performance in relation to the sociocultural and behavioral factors that encourage knowledge-sharing and application. Finally, future research might focus on the merger of emergent technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence and Big Data analytics, and digital knowledge management to explore how they synergistically enhance the use of knowledge, innovation, and organizational performance in highly digitalized settings.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes and empirically tests a model of a serial mediation model in which innovation is the primary reason for connecting three digital knowledge management (KM) practices—Digital Knowledge Storage (DKNST), Digital Knowledge-Sharing (DKNSH), and Knowledge Utilization in Digital Technologies (KNUTDTs)—to the Perception of Organizational Performance (PERPOP). The study is set in service organizations in Kuwait, which are undergoing rapid transformation and increasing dependence on the delivery of knowledge-intensive services.

The study used validated measurement instruments on a sample of 245 respondents obtained from 127 organizations and applied EFA, CFA, and SEM to examine the proposed relationships. The results of the analyses show that none of the KM frameworks directly impact performance. Rather, such impact is fully mediated by innovation– further confirming the argument that innovation is the primary channel through which digital KM practices achieve substantial strategic performance.

This research makes both theoretical and practical contributions. On a theoretical level, it contributes to understanding digital KM by defining it as cumulative and non-linear, in which value is embedded in knowledge and its subsequent transformation into innovation. On a practical level, the research offers constructive advice to managers and public policy makers, highlighting the need to integrate and align cross-boundary knowledge, systems, and digital tools as a vital source of sustainable competitive advantage in service-dominated economies. Furthermore, the research appreciates the incorporation of AI and Big Data technologies into digital KM systems as a new research frontier, because these technologies are expected to further enhance an organization’s innovation orientation and performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; Formal Analysis, E.E. (Erdem Erzurum); Validation: S.Z.; Investigation: H.Z.; Methodology, S.Z. and E.E. (Erdem Erzurum); Project Administration: H.Z.; Resources: S.Z. and E.E. (Erdem Erzurum); Supervision: H.Z. and S.Z.; Visualization: E.E. (Enes Eryarsoy) and F.N.; Writing—Original Draft: H.Z., S.Z., E.E. (Enes Eryarsoy), E.E. (Erdem Erzurum), and F.N.; Writing—Review and Editing: E.E. (Enes Eryarsoy) and F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KNUTDT | Knowledge Utilization Through Digital Technologies |

| DKNST | Digital Knowledge Storage |

| DKNSH | Digital Knowledge-Sharing |

| INNOV | Innovation |

| PERPOP | Perceived Organizational Performance |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The literature review.

Table A1.

The literature review.

| # | Article | KNUTDT | DKNST | DKNSH | INNOV | PERPOP | KEYWORDS/FOCUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ramos Cordeiro et al. (2024) [1] *** ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM barriers, SMEs, absorptive capacity, innovation, performance |

| 2 | Kusa et al. (2024) [2] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | Entrepreneurial orientation, KM mediation, firm performance |

| 3 | Grant (1996) [3] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Knowledge integration, KBV, coordination, theory foundation |

| 4 | Nonaka (1998) [4] * | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | SECI model, knowledge creation, organizational learning |

| 5 | Darroch (2005) [5] *** ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM capabilities, innovation, firm performance |

| 6 | Alavi & Leidner (2001) [6] *** ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | KM systems, knowledge storage/retrieval, collaboration |

| 7 | Donate & de Pablo (2015) [7] ** | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | Knowledge-oriented leadership, innovation outcomes |

| 8 | Truong et al. (2023) [8] *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Intellectual capital, KM success, innovation, compliance |

| 9 | Gan et al. (2023) [9] *** | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Knowledge heterogeneity, task/relationship conflict, innovation |

| 10 | Qadri et al. (2024) [10] * ** *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Learning processes, KM mediation, organizational performance |

| 11 | Huber (1991) [11] * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | Learning processes, information distribution, memory |

| 12 | Argote et al. (2003) [12] * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | Creation–Retention–Transfer framework, innovation |

| 13 | Barney (1991) [13] *** | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | VRIN resources, competitive advantage |

| 14 | Wernerfelt (1984) [14] *** | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | Resource positions, profitability |

| 15 | Spender & Grant (1996) [15] ** *** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | Knowledge integration, collective sharing |

| 16 | Ode & Ayavoo (2020) [16] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM → Innovation → Performance |

| 17 | Zaim et al. (2007) [17] ** *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | KM process and infrastructure performance |

| 18 | Andreeva & Kianto (2012) [18] ** *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM capability, competitiveness, economic performance |

| 19 | Wang & Noe (2010) [19] ** | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | Knowledge-sharing review |

| 20 | Zack et al. (2009) [20] ** *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | KM practices → organizational and financial performance |

| 21 | Tortorella et al. (2024) [21] *** ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM + I4.0 innovation performance |

| 22 | Moffett et al. (2003) [22] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | KM applications and performance |

| 23 | Tønnessen et al. (2021) [23] ** * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | Digital sharing and creative performance |

| 24 | Jasimuddin & Zhang (2009) [24] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | Knowledge transfer symbiosis |

| 25 | Dženopoljac et al. (2016) [25] *** ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Intellectual capital and financial performance |

| 26 | Davenport & Prusak (1998) [26] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Working knowledge book |

| 27 | Choi et al. (2008) [27] ** *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM strategy complementarity |

| 28 | Lin (2007) [28] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM sharing → innovation → performance |

| 29 | Tajdini & Tajeddini (2018) [29] *** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Public KM and innovativeness |

| 30 | Deng et al. (2023) [30] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | Digital sharing and job performance |

| 31 | Zaim et al. (2019) [31] ** *** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | KM process → performance (PLS-SEM) |

| 32 | Mohaghegh et al. (2024) [32] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM, utilization, sustainability |

| 33 | Backer (1991) [33] * | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Conceptual “third wave” of knowledge use |

| 34 | Paisley (1993) [34] * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ICT and knowledge use framework |

| 35 | Pavlou & El Sawy (2011) [35] *** * | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Dynamic capabilities and innovation |

| 36 | Ganzaroli et al. (2014) [36] * | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | Social entrepreneurship and exaptation |

| 37 | Sumbal et al. (2020) [37] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | Knowledge-retention framework |

| 38 | Tyndale (2002) [38] ** | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | KM software taxonomy |

| 39 | Muhammed & Zaim (2020) [39] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | Peer-sharing and leadership support |

| 40 | Khalil & Shea (2012) [40] ** | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | Sharing barriers in universities |

| 41 | Chou et al. (2014) [41] | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ERP post-implementation; social capital/motivation → sharing; usage |

| 42 | Byukusenge et al. (2016) [42] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM→Innovation→Performance mediation; SMEs Rwanda |

| 43 | El-Haddad (2021) [43] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | MSME policy, COVID-19 and oil shock; reform agenda (non-empirical) |

| 44 | Dizmen (2021) [44] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Oil price macro scenarios; fiscal/GDP elasticities |

| 45 | Sarie & Ismaiel (2021) [45] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Kuwait GDP structure (oil vs. non-oil), macro trends |

| 46 | MOFA Vision 2035 [46] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | National strategy page; diversification and competitiveness goals |

| 47 | Heisig (2009) [47] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | KM frameworks, 160-model comparison, global KM standards, harmonization |

| 48 | Del Giudice & Della Peruta (2016) [48] *** ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | IT-based KM systems, internal venturing, innovation, corporate performance |

| 49 | Zaim (2016) [49] | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | KM processes → HRM; sharing ns; Gulf oil company case |

| 50 | Dziuban & Shirkey (1974) [50] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | KMO, Bartlett; factor analysis prerequisites (methods) |

| 51 | Tavakol & Dennick (2011) [51] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Cronbach’s alpha; reliability (methods) |

| 52 | Hair (2009) [52] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Multivariate methods (EFA/CFA/SEM); textbook |

| 53 | Hair & Alamer (2022) [53] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | PLS-SEM guidelines; education methods |

| 54 | MacKinnon et al. (2004) [54] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Mediation CIs; methods |

| 55 | Mills & Smith (2011) [55] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | KM decomposition; utilization → OP |

| 56 | Salloum et al. (2019) [56] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | E-learning acceptance (TAM), UAE |

| 57 | Argote & Ingram (2000) [57] | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | Knowledge transfer; competitive advantage |

| 58 | Karim et al. (2024) [58] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | Digital KM → organizational performance (proceedings) |

| 59 | Yaqub & Alsabban (2023) [59] | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | Social media knowledge-sharing |

| 60 | Grant (2002) [60] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | KBV chapter; knowledge integration/application |

| 61 | Curado & Bontis (2006) [61] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | KBV and precursor overview (conceptual) |

| 62 | Martín-de Castro (2015) [62] | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | Openness, absorptive capacity, innovation focus |

| 63 | Schwandt & Marquardt (1999) [63] * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | Organizational Learning System Model → Learning → Performance |

| 64 | Migdadi (2020) [64] *** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM → CRM → Innovation Capabilities (empirical) |

| 65 | Suparwadi et al. (2024) [65] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | IC + KM + Innovation → OP (HEI context) |

| 66 | Wongmahesak et al. (2025) [66] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM process → Technological Innovation → OP |

| 67 | Abou-Zeid & Cheng (2004) [67] ** | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | KM and innovation effectiveness |

| 68 | Mardani et al. (2018) [68] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | KM → Innovation Performance |

| 69 | AmirDadbar et al. (2025) [69] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Innovative offshoring KM framework |

| 70 | Machado et al. (2022) [70] ** | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | KM + Digital Transformation → Performance |

| 71 | Thomas (2024) [71] * | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Socio-technical systems perspective on KM and Innovation |

* OLT. ** KBV. *** RBV.

References

- Ramos Cordeiro, E.; Lermen, F.H.; Mello, C.M.; Ferraris, A.; Valaskova, K. Knowledge Management in Small and Medium Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review, Bibliometric Analysis, and Research Agenda. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 590–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]