Abstract

Given that the European Union is facing complex fiscal challenges arising from recent crises, understanding the impact of fiscal rules, institutional governance, and economic performance is critical. This paper examines the effects of fiscal rules and sustainable development trajectories in the context of effective governance of EU member states, analysing how these rules affect fiscal resilience, which is understood as the government’s ability to maintain discipline, absorb shocks, and sustain growth without undermining macroeconomic stability. This study focuses in particular on 2012 to 2023: a period marked by post-crisis adjustments and institutional consolidation. To carry out the proposed empirical analysis, we apply a panel vector autoregressive (VAR) model to capture the dynamic interdependence between fiscal policy indicators, governance quality, and economic performance, offering a temporal and comparative perspective across countries with varying levels of compliance with fiscal rules. Our results indicate that strong fiscal rules are embedded in robust institutional frameworks that enhance fiscal resilience, stabilise public finances, and foster long-term, sustainable economic growth. This study also demonstrates that effective governance is essential for translating fiscal discipline into improved economic outcomes, providing insights for policymakers and researchers on sustainable development strategies. These findings contribute to the literature by highlighting how institutional quality and fiscal rules interact dynamically, particularly during periods of economic restructuring and regulatory adaptation.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of intensifying fiscal pressures within the European Union, generated by recent economic crises, the analysis of the relationship between fiscal rules and the economic performance of member states is becoming increasingly relevant. This is mainly due to the growing importance of budgetary discipline and institutional reforms, which are essential for ensuring sustainable development and maintaining the stabilisation function of fiscal policy [1]. National governments that choose to implement unsustainable fiscal policies often face difficulties in debt repayment. Over the long term, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth has been higher in countries with constitutional fiscal rules than in those without such regulations [2].

The motivation for this research stems from the sustained scientific interest in understanding the interaction between fiscal rules and macroeconomic variables: a topic of central importance in both the literature and the practice of economic policymaking. This research aims to explore existing dynamics and address persistent knowledge gaps regarding the causal and temporal relationships between fiscal governance and governance indicators.

The study covers 26 EU member states over 2012 and 2023: a period characterised by post-crisis recovery and new fiscal challenges. The countries included were chosen to demonstrate comparability, as well as their long-term commitment to fiscal ceiling regulation through the European Union structure. In conducting the research, we used the vector autoregressive (VAR) model to investigate the dynamic relationship between fiscal rules and the sustainability of economic development, modelling the interaction between these variables. In addition, the model considers institutional indicators, namely the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGIs), which have also been used in previous research [3], including Control of Corruption, Rule of Law, Quality of Regulations, and Government Effectiveness, to investigate the role of governance quality in determining the effectiveness of fiscal regulations.

In this context, we conceptualise fiscal resilience as the government’s capacity to maintain fiscal discipline, absorb and recover from economic shocks, and continue supporting sustainable growth without endangering macroeconomic stability. This definition aligns with the theoretical foundations of institutional economics and fiscal governance theory, emphasising the crucial role of robust institutions and well-designed fiscal frameworks in maintaining long-term fiscal and economic stability.

The contributions and novelty of this study lie in its empirical approach to the relationship between fiscal rules and economic performance within the European Union over an extended period (2012–2023) in a context marked by economic transitions and institutional consolidation. The innovative element involves the use of a VAR model to capture the interdependent dynamics between fiscal policy indicators, public governance, and economic performance, providing a temporal and structural perspective specific to a comparative analysis framework among European Union member states with varying levels of compliance with fiscal rules. By focusing on these countries in the post-crisis period, this study provides an updated and relevant perspective on structural adjustments in the literature, which has not sufficiently addressed the evolving interactions between institutional frameworks and fiscal discipline, particularly during periods of economic restructuring and regulatory adaptation.

While this study primarily examines fiscal rules and governance quality through institutional dimensions such as control of corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness, the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also depends on the broader fiscal policy framework. While fiscal regulations fundamentally shape the structure and distribution of public expenditures, their function is not isolated; instead, it is mediated by contextual factors. Therefore, fiscal components that shape fiscal resilience and inclusive growth include public investment in social and environmental programmes, fiscal transfers, and social security expenditures. Understanding these connections provides a more comprehensive view of how fiscal regulations support sustainable and equitable development within the European Union, as well as budgetary discipline.

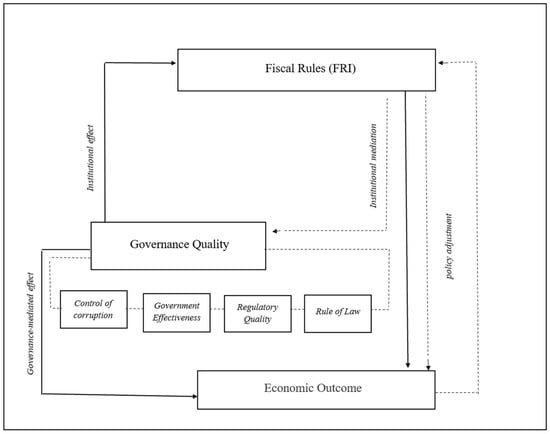

The theoretical foundation for this paper is derived from institutional economics and fiscal governance theory, which emphasise the importance of strong institutions with effective institutional governance as essential mechanisms for achieving fiscal sustainability and economic resilience. Thus, the use of the VAR model enables the data to reveal how these variables interact dynamically, rather than directly assuming whether these regulations influence the quality of governance. Building on this theoretical foundation, Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of the study. The empirical model operationalises the link between institutional economics and fiscal governance theory by capturing how governance quality mediates the relationship between fiscal rules and economic outcomes. In the VAR panel data framework, fiscal rules and institutional indicators interact dynamically, reflecting the theoretical premise that institutional strength enhances the credibility, enforcement, and long-term effectiveness of fiscal frameworks.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework linking fiscal rules, governance quality, and sustainable economic growth.

The expected results aim to demonstrate that strong fiscal rules, when embedded in solid institutional environments, improve long-term growth trajectories. The research also proposes hypotheses regarding the impact of fiscal rules on economic growth, providing valuable insights for both policymakers and researchers interested in the sustainable development of states. The fundamental premise is that stable fiscal outcomes and long-term GDP growth are positively influenced by well-designed fiscal frameworks supported by high-quality institutions.

The following sections of the article are organised as follows: after the Introduction, Section 2 describes the literature review; Section 3 contains the methodology and the data; Section 4 comments on the results; Section 5 is dedicated to discussions; and Section 6, which presents the conclusions, limitations of the research, and policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Our study examines the current state of knowledge regarding the relationship between fiscal rules and economic performance in the European Union, highlighting gaps in the understanding of the causal mechanisms through which these rules affect economic growth and fiscal stability.

The main EU-level fiscal rules include the structural balance rule, expenditure benchmark, 3% overall deficit rule, and debt reduction benchmark [4,5]. Member States have adopted similar rules at the national level, although they may employ different models and specifications. While some regulations are entirely identical to those at the European Union level, others differ significantly or only in a few aspects. According to the research mentioned above, national regulations also cover multiple levels of administration and various budget items [4].

Examining the historical development of EU tax rules, the literature reveals a substantial increase in their number, from 16 in 1990 to 67 in 2008 [6]. This adoption reflects a broader effort to strengthen fiscal governance and achieve greater fiscal stability within the European Union. Fiscal stability is achieved through the fiscal responsibility of EU Member States, which is reflected in the balance between national fiscal autonomy and adherence to standard fiscal governance, as well as through flexibility in responding to economic shocks [2]. Studies in the field also show that the growing trend towards the adoption of fiscal rules highlights an increasing emphasis on fiscal discipline, which highlights the importance of the relationship between the number of fiscal rules and their effectiveness [2,7,8]. However, a high number of rules can reduce compliance and increase institutional complexity [7]. Accordingly, a balanced set of tax regulations can be adopted.

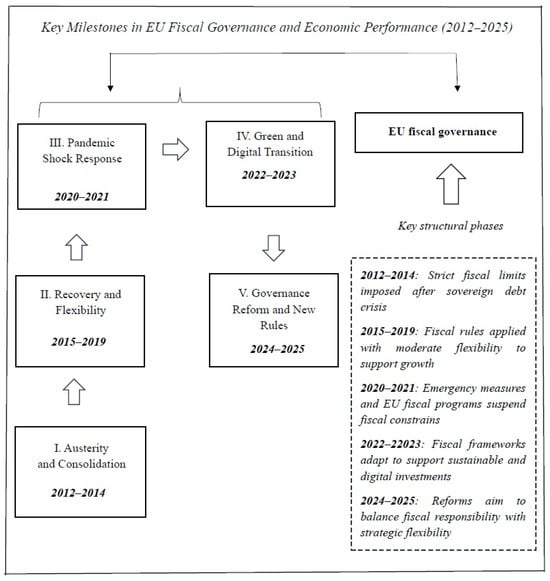

The significant structural developments and interdependencies between the economic, institutional, public governance, and social levels during the period 2012–2023 are summarised in Figure 2. This chronological representation highlights the transition from the post-crisis phase, marked by austerity and fiscal consolidation policies, to a phase of recovery and institutional adaptation, culminating in the transition to sustainability and digitalization in the post-pandemic context. From an economic perspective, the period analysed reflects the application of the European Fiscal Compact and, subsequently, the temporary suspension of fiscal rules [9]. At the institutional and public governance level, the figure illustrates the process of reforming the European fiscal framework and integrating green and digital objectives into budgetary policies [9]. On the social front, the evolution captures the transformation of public perception of taxation, from an instrument of correction to an instrument of sustainability and equity. Overall, the figure highlights the dynamic and interconnected nature of the transformations in the European Union, providing a visual basis for analysing the relationship between taxation, economic growth, and societal resilience.

Figure 2.

Evolution of Fiscal Policy and Governance Dimensions in the European Union.

To maintain the sustainability of public finances and prevent macroeconomic imbalances, fiscal regulations are a crucial component of the European Union’s economic governance. Previous research offers new critical insights into the relationship between the quantity of fiscal regulations and the level of compliance in EU Member States [10]. Based on the literature in the field, they present a nonlinear relationship in their analysis, demonstrating that while a small number of fiscal rules can improve compliance, an excessive number can have the opposite effect. However, after a certain point, the relationship becomes negative, suggesting that multiplying the number of tax rules could make it more difficult to comply with the law due to complexity, ambiguity, and enforcement challenges.

The literature [11] highlights that the impact of fiscal rules is mediated by institutional quality, which is identifiable through four dimensions of governance: control of corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness. A low level of control of corruption restricts extra-budgetary operations and opportunities, thus compromising de facto compliance and the credibility of sanctions. In contrast, a high level of regulatory quality enhances the design and transparency of rule parameters, thereby reducing costs and improving monitoring by tax institutions. A robust rule of law also helps reduce misconduct, which reflects government effectiveness, facilitating timely and qualitative adjustments that favour spending with economic growth objectives [12]. However, research emphasised the need for a balance between public debt accumulation and macroeconomic stability maintained through the quality of institutions, which should foster responsible debt management to ensure that investments financed by debt contribute to sustainable development [13]. Accordingly, although public debt might carry a negative influence on economic growth, over the long term, the interaction between public debt and institutional quality yields a positive effect.

The relationship between public debt levels and fiscal policy was emphasised for transitioning economies, with a focus on boosting public revenues, limiting corruption, and optimising expenditures for public debt control. While weak governance leads to higher accumulation of public debt, improving institutional quality might also lead to increasing debt levels to ensure government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and rule of law, but, over the long term, an improvement of institutional systems along with fiscal discipline represents the key to sustainable debt management [14].

In addition to the institutional dimensions that condition fiscal performance, the recent literature emphasises that the effectiveness of fiscal frameworks in supporting sustainable development depends mainly on the composition and direction of public expenditures. According to [15], the economic and social impact of public investment depends on its effectiveness, which requires governments to allocate limited fiscal resources to projects that genuinely address development needs and improve social welfare. Their empirical findings show that well-targeted public investments foster sustainable economic growth, aligning fiscal policy with several SDGs, such as reducing inequality, improving quality of life, and ensuring environmental sustainability. Similarly, ref. [16] provides evidence that strict compliance with Budget Balance Rules may generate unintended effects on the composition of public spending. While such compliance strengthens fiscal discipline, it can reduce government consumption and social expenditures, potentially increasing income inequality and poverty. This trade-off highlights the need for flexible and socially inclusive fiscal frameworks that strike a balance between compliance objectives and growth and welfare goals. Moreover, ref. [17] highlights the importance of integrating social spending and productive public investment into fiscal rule design, through instruments such as expenditure benchmarks, escape clauses, or “golden rules,” ensuring that fiscal sustainability supports rather than constrains long-term social welfare.

Expanding budget transparency has proven essential for robust fiscal governance; the interaction between fiscal rules and transparency is pivotal for sustained debt reduction and fiscal credibility [18]. Do fiscal rules need budget transparency to be effective? Fiscal rules can significantly enhance fiscal discipline and policy outcomes, but their effectiveness is contingent upon budget transparency. Research has proven that fiscal rules only begin to exert a meaningful disciplinary effect on government budgets, balancing based on a minimum threshold of transparency. This is because transparency helps sustain a country’s actual fiscal position, acting as a trigger for fiscal adjustments and focusing on its long-lasting impacts on public indebtedness. On the contrary, in countries with low transparency, the rules have less impact, and governments hide fiscal imbalances or engage in creative accounting. Therefore, transparency acts as a critical enabler, transforming fiscal rules into actionable constraints that promote sustainable fiscal behaviours.

Given the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, many OECD member countries have temporarily suspended tax rules to respond to urgent spending needs, highlighting the limitations of rigid regulations during such shocks [5]. The same study shows that this experience has led to renewed calls for reforming tax rule systems to better align with post-crisis fiscal realities and emerging challenges such as climate change, demographic shifts, and regional disparities. Other researchers emphasise that fiscal regulations are being closely scrutinised as states are forced to manage the legacy effects of public debt left behind by recent economic crises due to increased fiscal pressure and risks [7]. Moreover, they find that fiscal regulations are associated with improved fiscal performance when influenced by improved budget balances, lower debt, and lower volatility in public spending. Strengthening fiscal administration and establishing a regulatory framework are critical for sustainable growth and debt management [19].

Therefore, the coordination between monetary and fiscal policy is necessary to ensure economic stability. Rather than relying exclusively on expansionary policies, sustainable recovery requires a balanced mix of discretionary fiscal measures and complementary monetary interventions. Such coordination enhances the effectiveness of fiscal rules, ensuring that stabilisation efforts do not undermine long-term fiscal discipline or macroeconomic resilience. Flexible fiscal policies can amplify the effects of monetary policy, improving outcomes in price stability and employment, which is extremely important during downturns. Accordingly, although political and economic determinants are the main drivers of budget deficits, fiscal expansions and adjustments also influence the growth of public debt [20]. Overall, political and institutional factors significantly influence both the occurrence and duration of fiscal adjustments, which enhances the corroboration of institutional factors in fiscal regulations dynamics.

Sustainable recovery necessitates a balanced mix of complementary monetary interventions and discretionary fiscal actions rather than solely depending on expansionary fiscal measures. By ensuring that short-term stabilisation efforts do not compromise long-term fiscal discipline and macroeconomic resilience, such coordination improves the efficacy of fiscal rules. However, fiscal policy proves greater potential for economic stabilisation during crises; reforming EU fiscal rules related to debt ceilings and deficit limits is essential to empower member states during economic shocks [19].

Political will and economic conditions also play a role, with better compliance applied during periods of economic stability and when governments face electoral incentives to maintain fiscal discipline. Because countries are more likely to adhere to fiscal rules when they have strong institutions, credible enforcement mechanisms, and clear, well-designed rules, these characteristics are often related to the quality of the public institutional environment, which is also linked to an optimal design and framework of fiscal rules. Overall, fiscal rule compliance depends heavily on institutional strength, political commitment, and rule design [21].

The literature also focuses on the role of financial development and quality growth on sustainable development. Financial development enhances environmental sustainability by facilitating green investments and sustainable projects. Quality growth strategies, as observed through social welfare and resource efficiency, complement financial systems, shifting from quantitative economic expansion to a more comprehensive perspective of growth that encompasses social and environmental dimensions [22,23]. Welfare outcomes vary across countries, requiring context-specific fiscal models and harmonised policy efforts. Although fiscal discipline and tailored taxation may be vital for maintaining economic growth, they can only be balanced by a productive use of debt in infrastructure, education, and core services, which can sustain welfare improvements. Public policies that combine financial innovation with high-quality growth can contribute to reducing regional disparities and accelerate progress towards the transition to sustainable economies. However, narrowing regional gaps and enhancing social welfare also depend on effective allocation of public service expenditures within fiscal budgets, particularly in education, healthcare, infrastructure, and targeted government subsidies, which complement the effects of financial innovation. Moreover, achieving balanced, inclusive, and long-term sustainable development requires the integration of financial reforms with both environmental objectives and socially oriented fiscal spending.

The existing literature on the subject primarily focuses on descriptive or conceptual analyses that highlight the relationships between regulations, fiscal discipline, and debt sustainability. However, few studies use robust empirical methods to establish causal relationships between fiscal quality regulations and economic growth. This lack of methodology justifies the use of contemporary approaches, such as panel VAR models and Granger causality tests, which allow the detection of dynamic interdependencies and the direction of relationships between variables. The asymmetrical study contributes specifically through this type of analysis, providing more robust empirical evidence than that found in previous research.

Based on the various current contributions in the field of research, we can see there are still specific gaps in the specialised literature analysed. Adapting tax regulatory frameworks to address various contemporary issues, such as climate change, energy transition, and growing regional inequalities, is becoming a challenge for the future, highlighting the need for research aimed at exploring how tax rules can be designed to respond effectively to new socio-economic conditions. Furthermore, the literature should pay more attention to how rules can be calibrated and adapted to the institutional context and the need to respond to structural shocks. This is a matter that our study directly addresses through its policy recommendations.

3. Materials and Methods

This study analysed how fiscal rules affect economic growth in 26 European Union (EU) member states using a VAR panel data model. Guided by the theoretical framework, the VAR panel data model captures the dynamic feedback between fiscal rules, governance quality, and economic performance, consistent with the institutional perspective that strong governance enhances fiscal credibility and policy effectiveness.

The general equation of a Vector Autoregressive model of order p (VAR(p)) can be represented as follows:

where

is a k × 1 vector of observed endogenous variables at time t. In the context of your analysis, this would include the fiscal rules index (FRI) and GDP per capita (GDPpc). The fact that all variables are considered endogenous is an advantage of the VAR model [24].

is k × 1 vector of constants (the intercept term).

are k × k matrices of coefficients, for i = 1, …, p. These matrices capture the linear relationships between variables at different lags.

represents the vector of endogenous variables lagged by i periods.

p is the order of the VAR model, i.e., the number of lags included in the equation.

is a k × 1 vector of error terms (shocks or innovations), which are usually considered white noise, with zero mean and a constant covariance matrix.

In essence, each variable in the system is modelled as a linear function of its own past values and the past values of all other variables in the system. This formulation allows for the exploration of dynamic interdependencies between variables, such as how changes in the FRI can influence GDP per capita and vice versa, over time [25].

The analysis is structured to assess the long-term relationship between the fiscal rules and economic performance, controlling for key variables of effective public governance, over the period 2012–2023. The period was determined based on the availability of annual data for the indicators under analysis. The model used in the study is structured as follows:

where GDPpc represents gross domestic product per capita, represents the fiscal rules indicator, a composite index that measures the strictness of fiscal rules and represents the vector of control variables: Corruption Control, Rule of Law, Regulatory Quality, and Government Effectiveness.

VAR models are suited for describing the dynamic pattern of economic and financial time series, providing more accurate forecasts compared to univariate models (e.g., autoregressive models) and a flexible configuration in which forecasts can be conditioned on the future trajectory of the included variables [26]. In addition to forecasting, VAR models are also applied in policy analysis because they capture the causal response of the variables in the system to random shocks, which can be summarised using impulse response functions and variance decompositions. These characteristics of VAR make this framework particularly suitable for analysing how the interaction between fiscal rules and economic performance generates endogeneity effects as well as dynamic feedback effects.

In this study, the relationship between variables is examined using the panel VAR method. This approach allows us to determine the impact of fiscal rules on economic performance within the framework of effective governance. We also chose this model because it captures country-specific effects and dynamic adjustment processes, which are essential in assessing the long-term impact of policies. Similar approaches to the VAR model were adopted to present the relationship between economic growth and research and development expenditure, analysing the BRICS countries between 2000 and 2018 [27]. The data analysis was performed using EViews 12 Student Version Lite software, with diagnostic tests carried out to ensure that the autoregressive structure was valid.

The empirical analysis includes a series of diagnostic and robustness checks presented in tables: selection of the optimal lag length, model stability check through the inverse roots of the AR characteristic polynomial, statistical description of the data, VAR panel impulse response functions, and residual diagnostics such as LM tests for serial correlation, all supporting the validity of the autoregressive specification and the reliability of the estimated results. Using these methods, it is expected that sound and well-designed fiscal rules, embedded in sound institutional contexts, will promote more stable fiscal outcomes and enhance long-term economic growth.

In creating the database for our study, we utilised a comprehensive set of indicators to support the analysis of the impact of governance quality on the relationship between fiscal rules and economic performance in EU member states during 2012–2023. The choice of this time frame is motivated by a variety of factors. Firstly, the governance WGI and FRI indicators only became fully reportable and comparable for all EU countries after 2012, a period marked by post-financial crisis and sovereign debt reforms, when fiscal frameworks were strengthened by the Six-Pack and the Fiscal Compact, which justifies the choice of this starting point for studying fiscal rules. Secondly, this period includes recent major shocks, such as the COVID-19 crisis (2020–2021) and the war between Russia and Ukraine (since 2022), testing the flexibility and credibility of fiscal governance over a decade of observations that provides a sufficient horizon to capture the medium- and long-term effects of fiscal rules on economic growth and institutional quality. For a proper conceptualisation, we created a panel dataset with various indicators for the 26 EU countries (Table 1), excluding Malta from the analysis due to a lack of complete information.

Table 1.

Description of indicators and data sources.

The rationale behind the selection of these indicators is based on three fundamental dimensions that define the relationship between fiscal discipline, macroeconomic stability, and the quality of governance. Within the fiscal regulations dimension, the FRI was selected as a composite indicator that measures the strength and quality of fiscal rules in EU Member States.

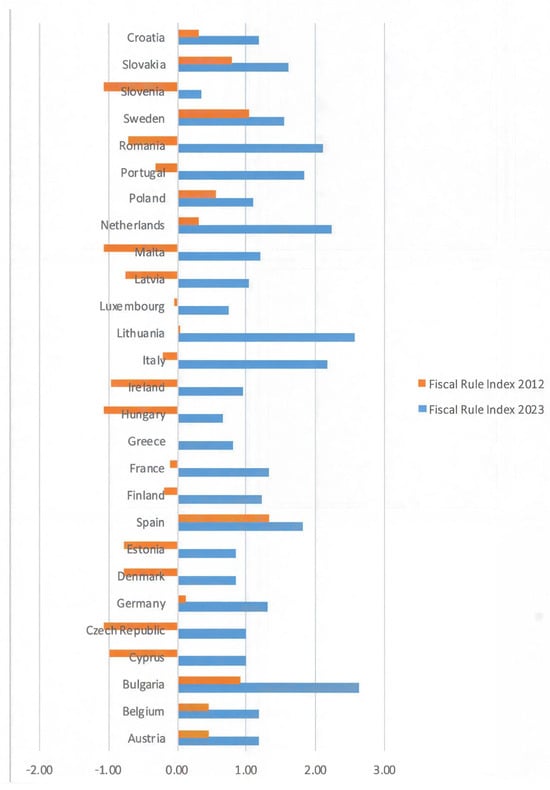

An analysis of FRI values (Figure 3) for the 26 EU countries over the period 2012–2023 proves a general upward trend, suggesting a strengthening of fiscal governance frameworks during the period under review.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the fiscal rules index in EU member states (2012 vs. 2023).

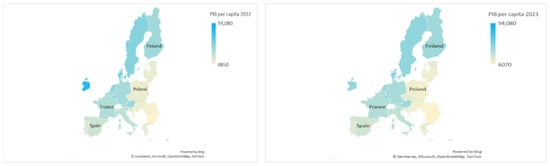

The choice of the EU region is justified by its unique institutional framework, economic and institutional diversity, and relevance to public policy. From these perspectives, the EU is a secure area where fiscal rules are supranational, enforced through the Stability and Growth Pact, but also through national transpositions, a combination of common rules and national adaptations that creates functional variation for comparative analysis. However, Member States differ substantially in terms of their level of development in terms of governance quality and degree of fiscal compliance, and this heterogeneity allows for robust testing of the relationship between fiscal rules, governance, and economic performance. The macroeconomic dimension is represented by the GDPpc indicator, which reflects the economic performance of EU member states. In the context of this research, it is used as a measure of the effectiveness of public sector policies in promoting economic development. An analysis of GDP per capita (Figure 4) for the period 2012–2023 highlights significant differences between EU member states, with high-income economies such as Luxembourg, Ireland, and Denmark standing out clearly from the rest.

Figure 4.

Evolution of GDP per capita in EU member states (2012 vs. 2023).

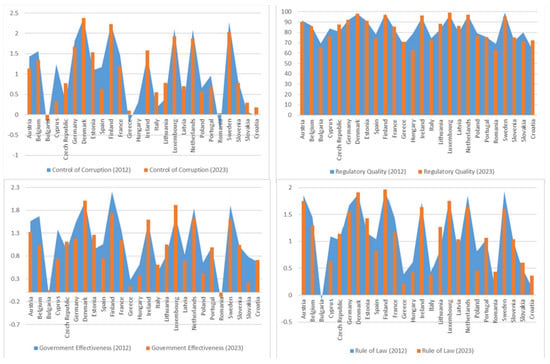

Governance indicators (Figure 5) were chosen to capture the institutional environment in which tax rules operate. These indicators provide information on the quality of public administration, the strength of institutional frameworks, and the enforcement mechanisms that can support or undermine the effectiveness of fiscal regulations. A comparative analysis of these indicators for the period 2012–2023 shows a general trend of improvement, reflecting the gradual strengthening of governance in EU member states.

Figure 5.

Evolution of governance indicators in EU member states (2012 vs. 2023).

The descriptive statistical analysis of the indicators presented above is visually represented in Table 2. FRI has an average of approximately 1, reflecting moderate fiscal governance, while GDP per capita shows high variability, indicating economic disparities. The institutional indicators, although close to 1, deviate from normality (Jarque–Bera, p < 0.05), revealing heterogeneity in governance. From an economic point of view, EU member states show different levels of economic development, as evidenced by variations in GDP per capita. These differences are also reflected in the FRI values (Kurtosis > 3 for FRI and GDPpc), as some countries have adopted rigorous rule-based frameworks. In contrast, others maintain weaker fiscal discipline, even though the EU has encouraged fiscal harmonisation across all member countries over time. On average, EU countries indicate a moderate commitment to fiscal discipline.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

These findings underscore the importance of considering not only the presence of fiscal rules but also the broader governance environment in which they are embedded. In the absence of high-quality institutions, fiscal rules may be less effective in promoting long-term macroeconomic stability.

4. Results

The analytical approach of the study was to highlight how the quality of public governance conditions the effectiveness of fiscal regulations and causally influences economic performance in 26 European Union member states between 2012 and 2023. Within this analytical framework, we undertake a comprehensive correlation analysis as a preliminary step. The objective is to evaluate the linear relationships between the key variables before progressing to the Vector Autoregressive model. This initial exploration assists in identifying the strength and direction of associations, offering valuable insights into potential interdependencies and influencing subsequent modelling choices [28,29]. Furthermore, prior to the VAR model estimation, we conducted several preliminary tests presented in the appendix, including a Heterogeneity analysis based on the classification of EU countries (Table A1), a Cointegration test (Table A2), and a Cross-Section Dependence Test (Table A3) and a Slope Heterogeneity Test (Table A4). The correlation matrix reveals several important patterns (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis.

The correlation results clearly illustrate a robust positive relationship between GDP per capita and all the governance indicators we examined: Control of Corruption, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, and Rule of Law. Specifically, the correlation coefficients consistently fall within the range of approximately 0.69 to 0.76. This observation strongly suggests that regions exhibiting higher standards of public governance quality are consistently linked with superior economic performance, as evidenced by their GDP per capita.

In contrast, the Fiscal Rule Index presents a different picture, displaying notably weak and predominantly negative correlations with both GDP per capita and the various governance indicators. This initial finding implies that, when viewed strictly through a linear bivariate lens, the fiscal rule index may not bear a significant direct association with either a country’s economic performance or its quality of governance.

While our governance indicator descriptions are straightforward, a crucial aspect demanding our attention in this analytical framework is the potential presence of multicollinearity. Our initial correlation analysis revealed that the various Worldwide Governance Indicators—encompassing Control of Corruption, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, and Rule of Law exhibit a substantial degree of inter-correlation. This pronounced statistical interdependence among these proxies for governance quality could significantly complicate the precise estimation and clear interpretation of their individual impacts within our Vector Autoregressive model [16,30,31].

The implications of high multicollinearity are noteworthy: it can lead to inflated standard errors of coefficient estimates, making it quite challenging to pinpoint the unique contribution of each governance dimension. Moreover, it could potentially undermine the robustness and interpretability of impulse response functions, a key tool for understanding dynamic interactions in VAR models [32,33]. Prior to estimating the VAR model, unit root tests were conducted to ensure the stationarity of the variables, as detailed in Table A5 from appendix.

To capture the dynamic relationships between the selected variables, we estimated a VAR model at the beginning of empirical research, the results of which can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Estimation of the autoregressive vector.

Table 4 presents an overview of the dynamic relationships between the model variables. The table structure presents two distinct equations: one structure that tracks the FRI and a second one that tracks the GDP per capita. Therefore, for each possible influence, we focused on the estimated coefficient, the associated standard error, and a t-statistic, the indicator of confidence in the statistical significance of each element. At the same time, we demonstrated that the FRI is strongly influenced by its own value in the previous period, and the CR variable has a positive and significant effect on the dynamics of the FRI. On the other hand, GDP per capita proves considerable persistence, its variability being explained predominantly by its internal dynamics, with significant influence from its own lags. What is interesting, but not surprising, is that the interactions between FRI and this second variable, or the influences of other external factors (CC, EG, SD), appear to be quite limited or lacking in robust statistical significance in both directions. Overall, with an R-squared of approximately 77.8% for the FRI equation and 99.4% for the second GDP per capita variable, the F-statistics confirm that both equations are statistically significant.

To ensure the validity and robustness of the model, the optimal number of lags was determined using the Lag Order Selection Criteria test (Table 5) before interpreting the model results. Also, when determining the appropriate lag length, either the frequency of the data can be used, such as using a lag for annual data, or lag length criteria such as Akaike (AIC), Schwarz (SC), and Hannan–Quinn (HQ) can be used, which also demonstrate the use of a lag.

Table 5.

Criteria for selecting the number of lags.

The selection of a single lag within the Vector Autoregressive model, even in the presence of statistical indications such as the LR test that would suggest more lags, is based on economic considerations. When looking at Table 4, we can see that while criteria like Akaike, Schwarz, Hannan–Quinn, and the Final Prediction Error consistently suggest a lag order of 1, the Likelihood Ratio test points towards a lag order of 4. In situations where statistical indicators diverge like this, the ultimate choice for lag length really needs to blend both rigorous statistical analysis and sound economic intuition [34]. For our study, opting for a single lag is strongly supported by economic considerations, especially given the fiscal and economic dynamics at play within the European Union member states. We generally observe that the transmission effects of changes in fiscal rules on economic performance tend to manifest within a relatively short timeframe [35]. Furthermore, empirical evidence suggests that the impact of fiscal discipline on economic growth and debt sustainability is reflected quite quickly in macroeconomic indicators. Think about it: fiscal policy shocks, such as those related to government spending, can rapidly affect markets [36,37,38]. This approach not only aligns with the parsimony favoured by several information criteria but also ensures our model effectively captures crucial short-term dynamics without introducing unnecessary complexity or the risk of overfitting, which is a common concern in VAR modelling [34,39].

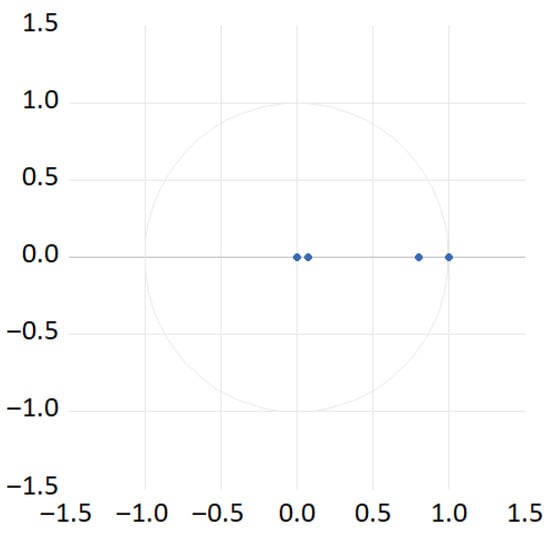

In the context of the specific fiscal and economic dynamics of the European Union member states, the transmission effects of changes in fiscal rules on economic performance manifest within a relatively short timeframe. Given the previous results and studies [2], they prove that the impact of fiscal discipline on growth and debt sustainability is reflected fairly quickly in macroeconomic indicators. Therefore, economic justification becomes a determining factor in selecting the model’s structure. An essential aspect of the estimated VAR model’s robustness is its stability. Stability ensures the validity and interpretability of impulse response functions, as well as the forecasts generated by the model. This stability is confirmed by checking each inverse root of the model’s characteristic AR polynomial, as they are located within the unit circle and have a modulus less than one. From a mathematical perspective, this property guarantees that any shocks applied to the system will dissipate over time, preventing forecasts from becoming divergent or explosive and ensuring that the model converges to a long-term equilibrium state.

The previously estimated VAR model is stable because each inverse root of the AR polynomial characteristic of the model, presented in Figure 6, lies inside the unit circle and has a modulus less than one.

Figure 6.

Inverse Roots of AR Characteristic Polynomial.

In analysing and forecasting data series, the values must not be correlated. Using the LM autocorrelation test for indicator residuals, we identified the absence of autocorrelation between values for the chosen lag (Table 6). Thus, the stability shown means that the panel VAR model used in this study is stationary, ensuring the reliability of subsequent dynamic analyses.

Table 6.

LM Test for Serial Correlation from Lags 1 to h.

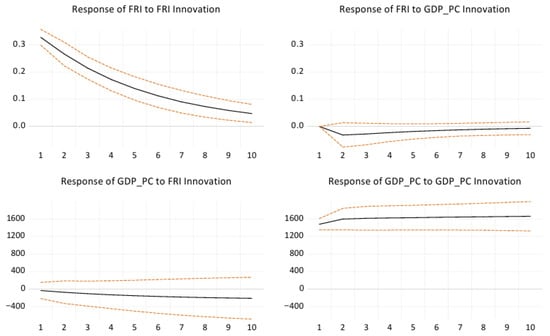

To examine the dynamic impact of shocks within the system, we used impulse response functions, which provide information on the short and medium-term dynamics between variables, highlighting the effects of the variables themselves and the influences of cross-variables.

In Figure 7, we specifically examined the impact of unexpected changes in the FRI on GDPpc, observing a negative effect, which shows that ambiguous fiscal policies have a negative short and medium-term impact on GDP per capita. This observed negative effect signifies that an unexpected deterioration in the quality or clarity of fiscal rules (the economic meaning of the shock) leads to a decline in economic output [40,41]. The impact is not merely statistical but reflects real economic consequences, such as increased uncertainty for economic agents, diminished government credibility, and potentially inefficient resource allocation [42]. The “short and medium-term impact” indicates the persistence of this effect, meaning that the initial shock propagates through the economy, affecting investment, consumption, and potentially labour markets for several periods before dissipating [43]. This distinct direction of the relationship—where a negative shock to the FRI leads to a negative response in GDP per capita—underscores the importance of robust and credible fiscal frameworks for macroeconomic stability and sustainable economic growth [44,45].

Figure 7.

Impulse response functions of the VAR panel. where: the solid lines in black reflect the estimated impulse response to a one-standard-deviation shock; the dashed lines in orange indicate the 95% Monte Carlo confidence bands.

However, while the short-term response indicates potential vulnerability, the variance decomposition (Table 7) indicates that FRI explains a small but growing share of the long-term variation in GDP per capita.

Table 7.

Variance Decomposition of the VAR model.

Table 7 was segmented into two sections, thus analysing the impact of shocks on both the FRI and GDP per capita. The variance decomposition analysis, performed over a relative forecast horizon of 12 periods, revealed distinct dynamics, but also a limited interdependence between the FRI and GDP per capita. In the case of the FRI, the standard error of the forecast showed a constant increase, from 0.328986 in the first period to 0.560147 in the last period, thus reflecting long-term uncertainty. The contribution of the FRI’s own shocks to the forecast error variance was dominant, representing 100% in the first period and remaining over 98.9% even at the maximum horizon of 12 periods, suggesting that its own internal dynamics almost entirely determine variations in this index. In contrast, the contribution of GDP per capita to the forecast error variance of the FRI was negligible, increasing from 0% to approximately 1.05% over the 12 periods. Similarly, regarding GDP per capita, the standard error of the forecast increased from 1479.261 to 5668.407 over the same horizon, indicating increasing predictive uncertainty. The contribution of the FRI to the forecast error variance of GDP per capita was also minimal, rising from approximately 0.05% to 1.04% over the 12 periods. Variations in GDP per capita were predominantly explained by its own dynamics, with a contribution of own shocks of 99.95% in the first period and over 98.9% over the entire forecast horizon. These results suggest the autonomy of each variable, with a marginal reciprocal influence within the analysed model.

From the analysis of the forecast error variance decomposition for both variables, it appears that both the FRI and GDP per capita are predominantly self-explanatory; that is, their variations are primarily determined by their own internal shocks or innovations within the VAR model. This relative autonomy is highlighted by a reduced interdependence between the two variables, the contribution of shocks from one variable to the forecast error variance of the other being minimal, remaining under 1.1% even over an extended forecast horizon. Thus, the direct and immediate influence of FRI shocks on GDP per capita and vice versa is marginal. Although a marginal increase in the contribution of the “external” variable is observed in the long run, this incremental influence remains insignificant compared to the dominant impact of own shocks.

This implies that, although the immediate effects may be negative, fiscal regulations play a role in influencing GDP per capita dynamics over time, suggesting that achieving a balance in the relationship between fiscal policy and economic performance is complex.

5. Discussion

The hypothesis of this study, which posits that sound and well-designed fiscal regulations, enshrined in favourable institutional contexts, positively influence more stable fiscal outcomes and long-term gross domestic product growth, is supported by the VAR model results. This underscores a critical economic message: fiscal discipline, while necessary, yields only weak or transitory effects without robust institutional credibility and effective governance mechanisms [46].

Following the analysis of the coefficients, a complexity was observed between the relationship between fiscal regulations and the strength of governance on economic performance, in that past values of endogenous variables (FRI, GDPpc) and exogenous variables (CC, EG, CR, SD) influence the current values of FRI and GDPpc In the short term, stricter fiscal regulations have a negative influence on economic performance (negative coefficient of −111.9702). This phenomenon can be explained by the correlation with the study conducted by [10], who highlighted that the relationship becomes negative due to the multiplication of numerical fiscal rules, which leads to ambiguity and challenges related to the application of these regulations. In the long term, with a positive coefficient of 3.66209 (statistically significant, p < 0.05), a positive relationship is confirmed, suggesting that the implementation of stricter tax regulations will generate positive economic effects in the future, but only under conditions of effective state governance. The impulse-response analysis, which clearly delineates a short-term negative yet a long-term positive relationship between fiscal rules and GDP per capita, illuminates a significant underlying adjustment mechanism. The initial adverse effect can be attributed to transient consolidation efforts, where the imposition of more stringent fiscal regulations necessitates immediate budgetary adjustments that may, for a brief period, temper overall economic activity. Nevertheless, this phase is subsequently followed by growth propelled by enhanced stability. This enduring positive trajectory emerges as a credible, long-term commitment to fiscal soundness that steadily cultivates heightened investor confidence, effectively diminishes risk premiums, and establishes a more predictable economic landscape, all of which are fundamentally conducive to sustained economic expansion. The relationship between the FRI and GDP per capita is investigated using VAR analysis over a period of 12 years in the EU27 countries.

According to the variance decomposition results for both variables, 100% of the variation in the FRI variable is explained by its own innovations in the first period, but after the second lag, over 98.9% of the variation is self-explained. At the twelfth lag, approximately 98.9% of the variation is self-explained, while approximately 1.05% is explained by the GDP per capita variable. Similarly, 99.95% of the variation in GDP per capita is presented by its own innovations (self-explained) in the first period, and up to the twelfth lag, over 98.9% of the variation is self-explained. Furthermore, according to the impulse-response analysis results, specific information about the nature of shocks and their detailed effects was not provided. It determines growth at the beginning of the period, as well as shocks (not specified) in the initial stages. However, the effect of these shocks diminishes towards the tenth period.

On the other hand, according to the VAR model analysis, the interactions between the two variables were limited and, in most cases, statistically insignificant, suggesting that a strong bidirectional causal relationship between the FRI and GDP per capita is not robustly supported by the estimation results. Based on the VAR analysis results, we can state the following findings: (i) in EU27 countries, an increase in the CR variable (according to the positive and significant coefficient of 0.013504 with a t-statistic of 2.67580 from Table 3) leads to a rise in the FRI. Other direct and significant causal relationships between FRI and GDP per capita, or vice versa, were not evidenced in the VAR model estimations. (ii) Both variables are predominantly influenced by their own past values, rather than significantly influencing each other within this model. Therefore, based on the presented estimates, we cannot affirm the existence of a strong and statistically significant bidirectional causal relationship between the FRI and GDP per capita. Our findings are supported by numerous studies that utilise similar methodologies, such as Granger causality tests and vector autoregression models, to explore macroeconomic interdependencies [2,47,48,49].

In addition, the prominence of government effectiveness and regulatory quality reinforces the role of governance in ensuring compliance with and enforcement of tax regulations. Countries with high institutional quality, such as Denmark and Finland, consistently achieve better economic outcomes because they combine strict tax regulations with practical elements of governance. In comparison, Romania ranks at the bottom in terms of government efficiency, with adverse effects that favour the absence of credible tax rules, but primarily economic vulnerability. These findings are consistent with the research conducted by [1], which emphasises that institutional quality is not only a complement to fiscal regulations but also a determinant of economic performance. The policy implications derived from these findings resonate with particular significance within the dynamic landscape of ongoing EU fiscal reform debates, notably those encompassing the 2023–2025 Council proposals aimed at bolstering the Stability and Growth Pact and cultivating a more robust fiscal framework [50,51,52]. Our research distinctly emphasises the imperative for a reform agenda that extends beyond the mere quantitative dimensions of fiscal rules. Instead, it advocates for prioritising the qualitative institutional environment crucial for their effective implementation and, critically, their sustained credibility. Therefore, the strategic focus should pivot towards crafting fiscal regulations that achieve a judicious balance: sufficiently flexible to adeptly respond to diverse economic cycles, yet concurrently robust enough to cultivate enduring stability and foster long-term growth. This balanced approach is poised to reinforce the fundamental objectives currently central to these pivotal European discussions [53,54]. The limitations of this study are devoted to considering future studies that include, in the VAR model analysis, a diversification of variables by analysing the impact of fiscal rules on the public deficit and public debt, as suggested by the need to investigate the influence of related macroeconomic phenomena.

6. Conclusions

Using the panel VAR approach methodology for the period 2012–2023, we analysed the relationship between the quality of fiscal regulation and economic performance within the European Union, emphasising the role of institutional power and the need for fiscal stability. Thus, the results highlight the close link between the quality of fiscal regulations and economic performance. A positive coefficient of the FRI shows that countries with coherent, predictable, and well-regulated fiscal policies tend to experience higher economic growth rates. This is also observable when governments provide fiscal stability and clear rules; the economic environment becomes more predictable, stimulating investment and confidence among economic agents.

The results of the VAR model estimation confirm this complex relationship between fiscal rules, institutional efficiency, and economic growth. In the context of good governance, demonstrated by indicators such as the rule of law, control of corruption, or government effectiveness, fiscal regulations have supported macroeconomic stability and long-term growth, as seen in countries such as Denmark or Finland. On the other hand, in nations with inadequate institutional capacity, such as Romania, the quantity and strictness of fiscal regulations have had a negative short-term impact, leading to vulnerability in economic performance by reducing gross domestic product per capita. In the long term, however, general regulations at the European Union level have forced states to align with fiscal responsibility standards and paved the way for stronger economic development, provided that structural changes are implemented and governance is improved.

Based on the results of the research study, several policy guidelines and recommendations can be developed, such as the following: (i) EU countries have a significant need to improve and strengthen coherent, predictable, and transparent tax regulations in order to improve economic performance. (ii) A key objective of fiscal and economic reforms should be to strengthen governance, in particular by increasing government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and respect for the rule of law. An essential contribution of this study lies in empirically demonstrating that fiscal rules alone are not sufficient for sustainable growth without the institutional “anchor” of good governance. This finding enriches the fiscal governance literature. The conclusions of this study can serve as a resource for policymakers seeking to improve fiscal governance and economic resilience within the European Union.

Future studies may address the present gaps in this research by focusing on nonlinear relationships, which were neglected in this study, and by examining the effects of fiscal rules on public deficit and debt as new endogenous variables in the VAR model. Future sub-objectives could also include comparing the economic performance of Member States that strictly comply with fiscal rules with those that do not, highlighting the differences thus generated. Addressing these gaps could lead to a deeper understanding of how fiscal rules interact with institutional frameworks and macroeconomic outcomes in different economic environments. In addition, further research could explore the role of exogenous shocks (such as energy crises or pandemics) in mediating the relationship between governance quality, fiscal discipline, and growth, as well as apply alternative dynamic models (e.g., GMM or PVAR) to test robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.-R.L.; methodology, C.C., D.-A.Ș. and A.F.C.; software, C.C. and D.-A.Ș.; validation, O.-R.L., C.C. and A.F.C.; formal analysis, C.C. and D.-A.Ș.; investigation, O.-R.L., S.V. and P.M.Ș.; resources, D.-A.Ș.; data curation, C.C. and A.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-A.Ș., C.C., O.-R.L., A.F.C., S.V. and P.M.Ș.; writing—review and editing, O.-R.L., D.-A.Ș., C.C., A.F.C., S.V. and P.M.Ș.; supervision, O.-R.L.; funding acquisition, O.-R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalization, the project with the title “Economics and Policy Options for Climate Change Risk and Global Environmental Governance” (CF 193/28.11.2022, Funding Contract no. 760078/23.05.2023), within Romania’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)—Pillar III, Component C9, Investment I8 (PNRR/2022/C9/MCID/I8)—Development of a program to attract highly specialized human resources from abroad in research, development and innovation activities.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository. [dataset] European Commission. 2025. Fiscal Rules Index database. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/db_indicators/fiscal_governance/documents/fiscal_rules_database_en.xls [accessed 20 August 2025]. [dataset] Eurostat. 2025. GDP per capita. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat [accessed 20 August 2025]. [dataset] World Bank. 2025. Worldwide Governance Indicators: Control of Corruption (CC.EST). The World Bank Group. https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/worldwide-governance-indicators/series/CC.EST [accessed 20 August 2025]. [dataset] World Bank. 2025. Worldwide Governance Indicators: Government Effectiveness (GE.EST). The World Bank Group. https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/worldwide-governance-indicators/series/GE.EST [accessed 20 August 2025]. [dataset] World Bank. 2025. Worldwide Governance Indicators: Regulatory Quality (RQ.PER.RNK.LOWER). The World Bank Group. https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/worldwide-governance-indicators/series/RQ.PER.RNK.LOWER [accessed 20 August 2025]. [dataset] World Bank. 2025. Worldwide Governance Indicators: Rule of Law (RL.EST). The World Bank Group. https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/worldwide-governance-indicators/series/RL.EST [accessed 20 August 2025].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CC | Control of Corruption |

| FRI | Fiscal Rules Index |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GE | Government Effectiveness Estimate |

| WGI | Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| RQ | Regulatory Quality: Percentile Rank |

| RL | Rule of Law Estimate |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| VAR | Vector autoregressive |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Heterogeneity analysis results based on the classification of EU countries.

Table A1.

Heterogeneity analysis results based on the classification of EU countries.

| Region | n_countries | mean_FRI | mean_GDPpc | mean_GE | mean_RL | mean_CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 8 | 0.663219 | 31667.08 | 1.048768 | 1.111717 | 0.930439 |

| E | 6 | 1.237044 | 12213.89 | 0.579577 | 0.611169 | 0.362784 |

| N–W | 7 | 1.0222 | 45193.1 | 1.625487 | 1.68346 | 1.833959 |

| S | 5 | 1.235277 | 22238.5 | 0.75991 | 0.680403 | 0.494582 |

1. C (Central): Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary. 2. E (Eastern): Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania. 3. N–W (North–West): Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Netherlands, Sweden. S (South): Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain.

Table A2.

Cointegration test.

Table A2.

Cointegration test.

| Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test | ||||

| Hypothesised No. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Trace Statistic | 0.05 Critical Value | Prob. |

| None * | 0.111328 | 28.19571 | 15.49471 | 0.0004 |

| At most 1 | 0.002465 | 0.577485 | 3.841466 | 0.4473 |

| Trace test indicates 1 cointegrating equation(s) at the 0.05 level. Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test | ||||

| Hypothesised No. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Max-Eigen Statistic | 0.05 Critical Value | Prob. |

| None * | 0.111328 | 27.61823 | 14.26460 | 0.0002 |

| At most 1 | 0.002465 | 0.577485 | 3.841466 | 0.4473 |

| Max-eigenvalue test indicates 1 cointegrating equation(s) at the 0.05 level. Normalised Cointegrating Coefficients (1 Cointegrating Equation) | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | ||

| GDP_PER_C | 1.000000 | |||

| FISCAL_RULE_INDEX | 130,566.3 | (24,801.9) | ||

| Adjustment Coefficients (alpha) | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | ||

| D(GDP_PER_CAPITA) | −0.001156 | (0.00118) | ||

| D(FISCAL_RULE_INDEX) | −9.67 × 10−7 | (1.9 × 10−7) | ||

where *: indicates statistical significance at 5% confidence level, indicating that the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected.

Table A3.

Cross-Section Dependence Test.

Table A3.

Cross-Section Dependence Test.

| Null hypothesis: No cross-section dependence (correlation) in residuals | ||

| Cross-sections included: 26 | ||

| Note: non-zero cross-section means detected in data. Cross-section means were removed during computation of correlations | ||

| Test Statistic | Value | Prob. |

| Breusch-Pagan LM | 1206.982 | 0.0000 |

| Pesaran scaled LM | 34.59419 | 0.0000 |

| Pesaran CD | 11.98577 | 0.0000 |

Table A4.

Slope Heterogeneity Test.

Table A4.

Slope Heterogeneity Test.

| dep_var | Delta | p_Value | df | Tbar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d_lgdp | −8.8317609 | 0 | 26 | 10 |

| d_fri | −8.8317609 | 0 | 26 | 10 |

| d_ge | −8.8317609 | 0 | 26 | 10 |

| d_cc | −8.8317609 | 0 | 26 | 10 |

| d_rq | −8.8317609 | 0 | 26 | 10 |

| d_rl | −8.8317609 | 0 | 26 | 10 |

Table A5.

Unit root test.

Table A5.

Unit root test.

| Im, Pesaran and Shin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Level | |||

| statistic | p-value | ||

| GDP_per c | 3.13379 | 0.9991 | Unstable |

| FRI | −2580.17 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| CC | −0.64304 | 0.2601 | Unstable |

| GE | −0.09360 | 0.4627 | Unstable |

| RQ | −0.75721 | 0.2245 | Unstable |

| RL | −0.71878 | 0.2361 | Unstable |

| In first difference | |||

| t-statistic | p-value | ||

| GDP_per c | −6.46582 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| FRI | −958.454 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| CC | −4.30589 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| GE | −3.42567 | 0.0003 | Stable |

| RQ | −5.94378 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| RL | −7.08060 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| LLC | |||

| Level | |||

| t-statistic | p-value | ||

| GDP_per c | −1.68621 | 0.0459 | Stable |

| FRI | −10878.3 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| CC | −3.59355 | 0.0002 | Stable |

| GE | −2.62077 | 0.0044 | Stable |

| RQ | −2.66499 | 0.0038 | Stable |

| RL | −4.42671 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| In first difference | |||

| t-statistic | p-value | ||

| GDP_per c | −10.9879 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| FRI | −7481.20 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| CC | −6.90904 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| GE | −4.97298 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| RQ | −6.53707 | 0.0000 | Stable |

| RL | −14.9850 | 0.0000 | Stable |

References

- Fatás, A.; Gootjes, B.; Mawejje, J. Dynamic effects of fiscal rules: Do initial conditions matter? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2025, 158, 104621. [Google Scholar]

- Potrafke, N. The economic consequences of fiscal rules. J. Int. Money Financ. 2025, 153, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, B.; Dima, S.M.; Lobont, O.R. New empirical evidence of the linkages between governance and economic output in the European Union. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2013, 16, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manescu, C.B.; Bova, E.; Hoogeland, M.; Mohl, P. Do national fiscal rules support numerical compliance with EU fiscal rules? Eur. Econ. Econ. Pap. 2023, 615, 40. [Google Scholar]

- De Biase, P.; Dougherty, S. The past and future of subnational fiscal rules: An analysis of fiscal rules over time. In OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism No. 36; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Fiscal rules, independent institutions and medium-term budgetary frameworks. In European Economy Occasional Papers No. 91; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brändle, T.; Elsener, M. Do fiscal rules matter? A survey of recent evidence. Financ. Innov. 2024, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, B.; Lobonț, O.; Nicolescu, C. The fiscal revenues and public expenditures: Is their evolution sustainable? The Romanian case. Ann. Univ. Apulensis Ser. Oeconomica 2009, 11, 416–425. [Google Scholar]

- Schelkle, W.; Natili, M.; Miró, J. The Role of Reforms and Investments in the EU Fiscal Governance Framework; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Căpraru, B.; Pappas, A.; Sprincean, N. Fiscal rules in the European Union: Less is more. J. Common Mark. Stud. 2025, 63, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, T.; Kinda, T.; Muthoora, P.; Weber, A. Expenditure rules: Effective tools for sound fiscal policy? In IMF Working Paper WP/15/29; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Badinger, H.; Reuter, W.H. The case for fiscal rules. Econ. Model. 2017, 60, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Song, D.; Ramzan, M. Institutional Quality, Public Debt, and Sustainable Economic Growth: Evidence from a Global Panel. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.N.; Luong, T.T.H. Fiscal Policy, Institutional Quality, and Public Debt: Evidence from Transition Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocolișanu, A.; Dobrotă, G.; Dobrotă, D. The Effects of Public Investment on Sustainable Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from Emerging Countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntotsis, K.; Karagrigoriou, A.; Artemiou, A. Interdependency Pattern Recognition in Econometrics: A Penalized Regularization Antidote. Economies 2021, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baret, K. Fiscal rules’ compliance and Social Welfare. In Working Papers of BETA 2021-38; Bureau d’Economie Théorique et Appliquée, UDS: Strasbourg, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gootjes, B.; de Haan, J. Do fiscal rules need budget transparency to be effective? Eur. J. Political Econ. 2022, 75, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedajev, A.; Pantović, D.; Milošević, I.; Vesić, T.; Jovanović, A.; Radulescu, M.; Stefan, M.C. Evaluating the Outcomes of Monetary and Fiscal Policies in the EU in Times of Crisis: A PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesenow, F.M.; de Wit, J.; de Haan, J. The political and institutional determinants of fiscal adjustments and expansions: Evidence for a large set of countries. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2020, 64, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Suárez, C. Determinants of compliance with fiscal rules. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2023, 75, 102124. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, F.; Ünlü, U.; Kuloğlu, A.; Çıtak, Ö. Modeling and Analysis of the Impact of Quality Growth and Financial Development on Environmental Sustainability: Evidence from EU Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragos, S.L.; Mara, E.R.; Mare, C.; Munteanu, S. Non-linear Effects of Fiscal Policy in European Welfare States. Econ. Anal. Pol. 2025, 88, 557–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.; BELAL, A.A.; Mami, A.M.; Latif, M.T.; Rusli, M. A Year-Long Investigation of the PM2.5 Dynamics in Klang Valley-Malaysia Using Variance Decomposition and Impulse Response Function Analyses. Res. Square 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaël, B.M.; Siaka, S. The Toxicity of Environmental Pollutants. In IntechOpen eBooks; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivot, E.; Wang, J. Rolling Analysis of Time Series. In Modeling Financial Time Series with S-Plus; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, Y.; Dundar, N.; Ozyilmaz, A. The relationship between R&D expenditures and economic growth in BRICS-T countries. Ongun J. Econ. Bus. 2022, 4, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, C. Macro-economic impacts of energy saving policies in Denmark. Energy Econ. 2020, 90, 104860. [Google Scholar]

- Sajid, M.J.; Khan, S.A.R.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Z. The long-term dynamic relationship between communicable disease spread, economic prosperity, greenhouse gas emissions, and government health expenditures: Preparing for COVID-19-like pandemics. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 32, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorich, M.; Strohmaier, S.; Dunkler, D.; Heinze, G. Regression with highly correlated predictors: Variable omission is not the solution. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolka, L.; Ngo, V.M.; Pavelková, D.; Le, B.T.; Dehning, B. Short- and medium-term car registration forecasting based on selected macro and socio-economic indicators in European countries. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 80, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Vector autoregressions. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winker, P.; Maringer, D. Optimal lag structure selection in VEC-models. Contrib. Econ. Anal. 2004, 269, 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrotă, G.; Vodă, A.D.; Dumitrașcu, D.D. The effects of fiscal policy shocks on the business environment. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 1084–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.; Sousa, R.M. The macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 4439–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, P.; Varga, J. Quantifying spillovers of coordinated investment stimulus in the EU. Macroecon. Dyn. 2023, 27, 1843–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Sterdyniak, H. Towards a better governance in the EU? Rev. De Lofce 2014, 132, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.; Kilian, L. A practitioner’s guide to lag order selection for VAR impulse response analysis. Stud. Nonlinear Dyn. Econom. 2007, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesen, T.F.; Beaumont, P.M. A joint impulse response function for vector autoregressive models. Empir. Econ. 2024, 66, 1553–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajedi, R.; Steinbach, A. Fiscal rules and structural reforms. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2019, 58, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrián, L.; Hirs-Garzón, J.; Urrea, I.L.; Valencia, O. Fiscal rules and economic cycles: Quality (always) matters. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2024, 85, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Linnemann, L. Tax and spending shocks in the open economy: Are the deficits twins? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2019, 120, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoba, B.P.; Kaseeram, I. Fiscal policy, sovereign debt and economic growth in SADC economies: A panel vector autoregression analysis. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2107149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Roldán, C.; Filho, F.F.; da Silva Bichara, J. Fiscal rules in economic crisis: The trade-off between consolidation and recovery, from a European perspective. Economics 2021, 15, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaskoven, L.; Wiese, R. How fiscal rules matter for successful fiscal consolidations: New evidence. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2022, 68, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampe, J.; Paparoditis, E.; Trenkler, C. Structural inference in sparse high-dimensional vector autoregressions. J. Econom. 2023, 234, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebowale, A.Y.; Algarhi, A.S. Macroeconomic determinants of economic growth in Africa. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2020, 34, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, A. Did the non-adoption of the gold standard benefit or harm Spanish economy? A counterfactual analysis between 1870–1913. Investig. Hist. Econ. 2019, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O.; Leandro, A.; Zettelmeyer, J. Redesigning EU fiscal rules: From rules to standards. Econ. Policy 2021, 36, 195–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroutunian, S.K.; Bańkowski, K.; Bischl, S.; Bouabdallah, O.; Hauptmeier, S.; Leiner-Killinger, N.; O’Connell, M.; Arruga Oleaga, I.; Abraham, L.; Trzcinska, A. The path to the reformed EU fiscal framework: A monetary policy perspective. In ECB Occasional Paper; European Central Bank: Frankfurt, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schnellenbach, J. On the reform of fiscal rules in the European Union: What has been achieved, and how did we get here? Econ. Voice 2025, 22, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespy, A.; Massart, T.; Schmidt, V. How the impossible became possible: Evolving frames and narratives on responsibility and responsiveness from the Eurocrisis to NextGenerationEU. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 31, 950–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, F.N.; Jonung, L. GDP, not the bond yield, should remain the anchor of the EU fiscal framework. Eur. View 2022, 21, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).