Abstract

Digitization and innovation supported by various innovation systems have become key factors in the sustainable development of companies, countries (including UE countries), and the economy as a whole. The primary objective of this study is to explore the interconnections between the perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization as a comprehensive innovation system supporting digitalization in EU countries. The study is grounded in the innovation systems theory, specifically employing the Quintuple Helix Model as a comprehensive framework, and addresses the challenge of digital divide across the EU. The research was conducted using K-means cluster analysis to identify homogeneous groups of countries within the EU. Subsequently, correlation analysis was applied to identify statistically significant relationships between the individual variables examined within the Quintuple Helix model and digitization within EU countries. Based on the results, we identified four distinct clusters of EU countries characterized by different degrees of digitization, governance, and intellectual Capital. It was found that countries with the highest level of digitization are also characterized by the highest levels of governance and intellectual Capital. Correlation analysis confirmed a strong interconnection between the examined perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and their relationship with digitization.

1. Introduction

In recent years, digital transformation has attracted growing attention in literature [1]. Its complexity necessitates interdisciplinary approaches, as the “human” dimension remains fundamental [2]. Previous studies have conceptualized technology either as a driver of “radical change” [3] or as an enabler of a new “organizational shift” [1,3], with significant implications for knowledge management, society, and individuals [4,5].

The societal embeddedness of technology has further been discussed in relation to communication and social interaction [6,7,8,9], as well as within the domains of philosophy and ethics [10] and politics and international relations [11].

Digitalization, often rooted in the concept of Industry 4.0, has radically transformed the global economy. Industry 4.0, defined as a “new type of industrialization” [12], was initiated through the integration of the Internet of Things and services into manufacturing environments, enabling the development of new products and services. Digitalization thus represents an advanced stage of societal, economic, and democratic development, directly linked to the dimensions of the Quadruple and Quintuple Helix models [6,13,14,15,16].

To fully exploit the potential of Industry 4.0 and 5.0, it is essential to integrate them with helix models. The concept of Democracy 5.0 relies on the technological foundation provided by Industry 4.0.

Despite the growing body of research on digital transformation and innovation systems, limited attention has been paid to the empirical examination of relationship between the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization across EU countries. Existing studies have primarily addressed theoretical aspects of the helix frameworks or focused on regional and sectoral applications. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by offering a comparative, data-driven analysis of how the Quintuple Helix perspectives relate to digitalization in EU countries.

The novelty of this research lies in the integration of governance and intellectual Capital dimensions within the Quintuple Helix framework to explain cross-country differences in digitalization levels. By combining these perspectives, the study provides new insights into how innovation systems can support sustainable digital transformation in the European context.

The main objective of this study is to identify clusters of EU countries according to their profiles based on the perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and their levels of digitalization, as well as to explore the interconnections between these dimensions.

Given the strategic importance of digitalization for the European Union’s competitiveness and sustainability, it is essential to understand how innovation systems such as the Quintuple Helix can support this process. Therefore, this paper examines the relationship between digitalization and the Quintuple Helix model across EU countries.

2. Literature Review

The set of theories encompassing the Triple, Quadruple, and Quintuple Innovation Helix—metaphorically referred to as the “Helix Trilogy”—provides insights into how knowledge and innovation can co-evolve within the context of a knowledge-based economy, knowledge society, and knowledge democracy [13,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. This trilogy of models highlights that innovation processes are inherently systemic, involving multiple actors and feedback loops that integrate economic, social, political, and ecological dimensions.

The conceptual understanding of innovation systems is grounded in a historical overview of various models of knowledge and innovation production. Traditionally, academic research—especially at research universities—focuses on basic research without particular concern for practical application or innovation. This approach is known as “Mode 1” knowledge production [17,18] and aligns with the linear model of innovation. In this linear mode, basic research is conducted in the university context and only subsequently diffused into the economy and society, where it is transformed into applications and innovations aimed at generating revenue and profit. It follows a sequential cause-and-effect relationship.

Later, “Mode 2” knowledge production emerged, emphasizing knowledge creation aimed at problem-solving and supporting non-linear models of innovation. Mode 2 follows principles such as “knowledge production in the context of application,” transdisciplinarity, “social responsibility and reflexivity,” and “quality control” [19,20].

Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff [21] introduced the Triple Helix model, which focuses on the relationships and interactions among three key institutional spheres: the academic community (universities/higher education institutions), industry (business), and government.

Through their interconnections and mutual shaping, these three helices create national innovation systems with dynamic knowledge flows. Although the Triple Helix emphasizes the importance of higher education for innovation, its primary focus is on the economy, or more precisely, the knowledge economy. The status of the political system (democratic or non-democratic) plays a minimal role in this model [22].

As an extension, “Mode 3” knowledge production [23] represents a type of institution or system that seeks to connect and integrate various modes of knowledge production and application, thereby fully supporting diversity and heterogeneity. Mode 3 universities are designed to foster “basic research in the context of application” [24] and align with the promotion of a “creative knowledge environment” [25]. The competitiveness of a knowledge system is determined by its adaptive capacity and its ability to combine and integrate diverse forms of knowledge and innovation through co-evolution, co-specialization, and cooperation [23].

The Quadruple and Quintuple Helix models of innovation systems, co-founded by Elias G. Carayannis and David F. J. Campbell [13,16,23], represent original work conceived from the outset as models with four or five helices. These models were inspired by broader intellectual narratives and provide a substantially wider context for innovation than the Triple Helix [21].

The Quadruple Helix model organically and proactively integrates the Triple Helix while adding a fourth helix: civil society/the public influenced by media and culture (“media- and culture-based public”), the arts (art-based research and innovation), democracy, and knowledge democracy.

The Quadruple Helix is broader because it additionally emphasizes the importance of society (knowledge society) and democracy (Knowledge Democracy) for knowledge production and innovation.

Knowledge Democracy is a concept and metaphor that highlights the parallel processes between political pluralism in advanced democracies and the heterogeneity of knowledge and innovation in advanced economies and societies [13]. The Quadruple Helix innovation model integrates the dimension of democracy with the aim of fostering knowledge and innovation [14,24].

To understand and operate the innovation system of the Quadruple and Quintuple Helix, it is essential to recognize that they are founded on democracy and ecology. This leads to two key implications: first, the development of knowledge and innovation requires co-evolution with democracy or knowledge democracy; second, ecology, ecological sensitivity, and environmental protection are essential for human survival and should also be regarded as drivers for further knowledge production and innovation development.

At the same time, this implies that for a system to truly function as a Quadruple or Quintuple Helix innovation system, government and the political system must be democratic in nature, not merely in form. Within these models, “climate democracy” for innovation and “knowledge democracy” are also integrated.

The Quintuple Helix is the most comprehensive model, integrating the Quadruple Helix while adding a fifth helix: the perspective of the “natural environment of society” [13,16]. The five-element helix explicitly refers to the need for “socio-ecological transformation” [26], which represents a key challenge. The model is designed to be ecologically sensitive and to link knowledge production and its application with considerations of “social ecology” (the interaction between society and nature) [27].

The Quintuple Helix considers environmental and ecological challenges as potential drivers of new knowledge and innovation [13] in the form of new types of transformation and digitalization. This model supports the creation of a mutually beneficial relationship among ecology, knowledge, and innovation—through transformation and digitalization—thus generating synergies among the economy, society, and democracy [13].

In recent years, the Quintuple Helix framework has increasingly been applied to the study of digital transformation, yet the literature remains fragmented. While a strong conceptual foundation has been established by key scholars, many studies [6,13,14,21] discuss digitalization as a systemic process that links knowledge production with democratic governance and environmental awareness. Nevertheless, a notable gap persists in the empirical examination of how these complex theoretical relationships manifest across countries or regions—particularly within the European Union context. Addressing this gap is crucial not only for advancing theory but also for understanding the practical implications of digital transformation in complex socio-technical systems. This rationale underpins the empirical approach adopted in the present paper.

While the Helix models (Triple, Quadruple and Quintuple) provide a structural framework for understanding the interactions between different actors, the ultimate goal of these systems is to increase the innovation capacity of the economy [28]. Innovation capacity represents the ability of a country, region or organization to generate, assimilate, adapt and commercialize new technologies and knowledge [29]. In the EU context, innovation capacity is a key factor for achieving the goals of the Lisbon Strategy and the 2030 Agenda. In the era of digital transformation, innovation capacity is increasingly becoming digital innovation capacity, and is associated with the readiness of society to use information and communication technologies—Digitization. These digital technologies act as a catalyst for innovation capacity. Therefore, strengthening innovation capacity in the EU is inextricably linked to the successful development of all five pillars of the Quintuple Helix model [30,31].

In light of this need to empirically investigate the interplay between helices and digitalization, a key challenge for contemporary society is planning potential pathways into the future. In the current hyperconnected scenario, humans and technologies, as well as human and artificial intelligence, are interconnected in such a complex way that they generate multiple possible futures, approaching the limits of imagination. It is precisely the boundary of digital and technological change that obliges social actors and socio-economic institutions to capture the dynamics of ongoing transformations and to foster the capacity to envision a desirable future that progresses intelligently toward sustainability, as exemplified by initiatives such as Next Generation EU [32]. Smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth is a central goal of numerous EU initiatives, strategies, and programs [33].

According to research by Kaivo-Oja and Stenvall [34], there is a concrete need to strengthen digitalization in the European context for open science, the Industry 4.0 strategy, and Industry 4.0 curricula across Europe. This concept highlights a symbiotic policy of a digitalized innovation ecosystem and a framework for economic growth policy for the European Union. In this context, numerous studies have been conducted focusing on this topic from various perspectives, such as the Helix Trilogy: The Triple, Quadruple, and Quintuple Innovation Helices from a Theory, Policy, and Practice Set of Perspectives [6]; Ecosystem Practices for Regional Digitalization: Lessons from Three European Provinces [35]; Digital Transformation of the Quadruple Helix: Technological Management Interrelations for Sustainable Innovation [36]; among others, which, however, do not specifically examine the relationship between digitalization and the individual perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model within EU countries.

Although the Quintuple Helix model is recognized as a comprehensive framework for innovation systems, most existing empirical studies either focus on partial sub-models or use a qualitative approach [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. A critical synthesis of the literature shows that there is a lack of consistent and direct empirical mapping that links the complete structure of the five pillars of the Quintuple Helix Model to a measurable and comprehensive indicator of digital maturity.

The current research provides intuitive links, but does not provide a structured comparison to identify which pillars of the innovation system are most strongly associated with digital success in different EU contexts. This opens a research gap: There is a lack of empirical verification of the patterns of association between all five pillars of the Quintuple Helix Model and Digitalization in EU countries. Building on these insights, the present study focuses on analyzing the Quintuple Helix model and its relationship to digitalization, with the aim of fostering social, economic, and environmental benefits. Its objective is to examine the interconnections among the perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model as a comprehensive innovation system that supports digitalization in EU countries.

The research question derived from the aim of the study is: “What are the clusters of European Union countries based on their profiles within the perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and the level of Digitalization, and what is their relationship?” This is grounded in a hypothetical model that builds on theory, in which it is assumed that all perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model are interrelated and collectively support Digitalization.

The associations that typically arise between the Governance and Intellectual Capital pillars and digital maturity are not only intuitive, but are underpinned by two key, interconnected theoretical mechanisms embedded within the innovation capacity. The quality of Governance (often associated with Democracy 5.0), which includes Digital Public Services, creates the necessary regulatory and institutional preconditions and trust needed for widespread digital adoption across society. At the same time, the Intellectual Capital pillar (representing Academia and the broader knowledge base, closely cooperating with Industry 4.0 and 5.0) [6,13,14,15,16] generates human Capital and digital skills that transform available digital opportunities into economic and social value. Therefore, the associations point to a logical connection: Governance creates the conditions, and Intellectual Capital provides the tools for successful Digitalization.

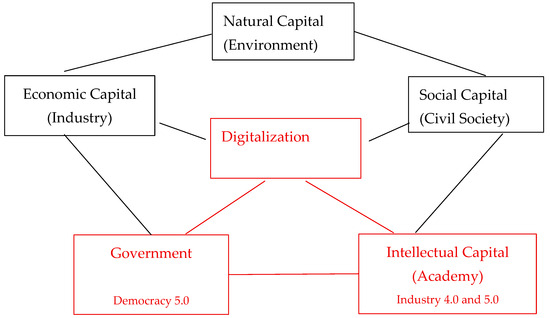

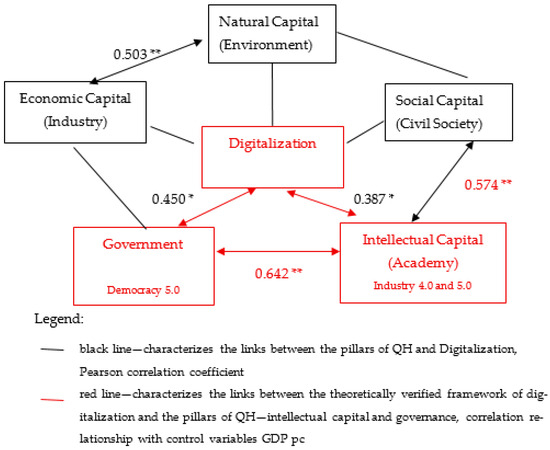

However, in the context of Quintuple Helix theories, digitalization is primarily connected with Industry 4.0 and 5.0, which are rooted in knowledge, innovation, and democracy. Drawing on theories of Digitalization, this hypothetical model is further narrowed to the relationship between Digitalization and the Intellectual Capital and Governance perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model (see Figure 1). The corresponding research question is: “What are the clusters of European Union countries based on their combined profiles of Intellectual Capital, Governance, and the level of Digitalization Capital?”

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model of the Quintuple Helix perspectives and their interconnection with Digitalization.

The theoretical foundation of this study is the Innovation Systems Theory, which examines how different actors (universities, industry, government) interact to foster innovation. The paper specifically adopts the Quintuple Helix Model an advanced variant of Innovation Systems Theory that explicitly incorporates the dimensions of the Natural Environment (ecology) and Civil Society alongside the traditional Government, Academia, and Industry [6,13,14,15,16]. Within this framework, Digitalization acts as a crucial cross-cutting catalyst, enabling enhanced interactions, data-driven decision-making, and transparency across all five pillars of the helix. The analysis of different levels of digitalization across EU countries is fundamentally linked to the Digital Divide Theory. The Digital Divide Theory focuses on the disparities in access, usage, and skills related to information and communication technologies between different groups or regions. The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) serves as the primary empirical tool in our study to quantify and monitor these disparities at the national level. By comparing the DESI performance of EU countries, we are essentially mapping the contours of the digital divide within the European context, identifying clustered groups with similar digital maturity levels [37].

3. Materials and Methods

Based on the stated research question: “What are the clusters of European Union countries based on their profiles within the Quintuple Helix model perspective and the level of digitalization (DESI)?”, the following research methodology was established.

The research object is represented by the individual EU member states—27 countries. The research subject is to identify the structure of the perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and the level of digitalization (DESI) on the mutual differentiation of EU countries.

To achieve the study’s objectives and verify the research question, a quantitative approach was chosen, combining K-means cluster analysis and correlation analysis. These methods made it possible to identify similarities and differences between EU countries and subsequently examine the actual interrelations among the analyzed variables.

The analysis was conducted using the Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index (GSCI) 2024 [38], whose indicators represent the Quintuple Helix model for individual EU countries: Natural Capital—environmental subsystem; Social Capital—social subsystem; Intellectual Capital—educational subsystem; Economic Capital—economic subsystem; and Governance—political subsystem. To assess the level of digitalization, the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2024 [39] was used, see Table 1. The study focuses on the current structural differences and the positioning of EU countries regarding the issue analyzed, based on the 2024 index data.

Table 1.

Indicators.

The application of cluster analysis is a standard and validated methodological approach for grouping countries based on their digital performance indicators. Several studies [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] have successfully used clustering techniques on DESI dimensions to categorize EU Member States, reveal internal disparities, and benchmark digital maturity across the Union. he DESI is structured around five principal dimensions (Human Capital, Connectivity, Integration of Digital Technology, Digital Public Services, and Use of Internet Services). Our selection of variables from Table 1 aligns with the components consistently used in scholarly analysis of the DESI framework.

To ensure a critical perspective and normalize the data before applying statistical analyses, standardization (Z-score) of the indices was performed.

Subsequently, to identify homogeneous groups of EU countries that exhibit similar characteristics in terms of the structure of the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization, K-means cluster analysis was applied. It is one of the most widely used and fundamental clustering methods in statistics and data science. It partitions a dataset into a pre-specified number of homogeneous groups (clusters). The choice of the optimal number of clusters for K-means cluster analysis was based on the synthesis of several methods, with the aim of finding a model that is both robust and interpretably rich. The primary method used was the Elbow Method (WCSS) based on the method of squares and the visual estimation of WCSS. Another method was Silhouette analysis using the silhouette coefficient. To verify the stability of the structure, a consistency analysis was performed between K-Means and GMM using the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and hierarchical clustering (Ward’s method). Subsequently, the PCA Biplot method was used to validate the obtained results for visual verification of the spatial stability of the clusters. The resulting determination of the number of clusters is based on the synthesis of the results and the determination of the optimal number of clusters for performing the K-means cluster analysis. The primary aim of the K-means method is to identify clusters within the data that are internally similar but differ significantly from those in other clusters [43]. To confirm that the variables significantly differentiated the final clusters (i.e., to verify the presence of mean differences between clusters), an ANOVA analysis was performed, where significance was demonstrated if p < 0.05.

To verify statistically significant interrelationships between the analyzed variables, correlation analysis was employed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Correlation analysis is a fundamental statistical method used to quantify the relationship (association) or dependence between two or more variables. The key indicator is Pearson’s correlation coefficient, ranging from ⟨−1; +1⟩. A value close to ±1 indicates a strong relationship, whereas a value close to 0 suggests a weak or no relationship. A positive correlation (+) means that as the value of one variable increases, the value of the other also increases (direct relationship). Conversely, a negative correlation (−) indicates that as one variable increases, the other decreases (inverse relationship) [44]. Pearson correlation was primarily used to assess the linear relationships between variables. To eliminate the potential confounding effect of economic wealth, which could lead to spurious correlations (as recommended by the reviewers), a control variable GDP per capita (GDPpc) was included in the analysis, measuring the relationship between the two variables that were statistically adjusted for the effect of GDPpc. Due to the multiple tests performed at once, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (controlling the False Discovery Rate, FDR) was applied to the p-values with a level of 0.05.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20. IBM SPSS Statistics 20 is the world’s leading statistical software used to solve business and research problems by means of ad hoc analysis, hypothesis testing, and predictive analytics. Organizations use IBM SPSS Statistics to understand data, analyze trends, forecast and plan to validate assumptions and drive accurate conclusions [45]. Statistical procedures not supported by IBM SPSS Statistic 20 were performed using MS Excel 365 and Colab. Statistically significant relationships identified through correlation analysis were subsequently incorporated into the hypothetical model.

4. Results

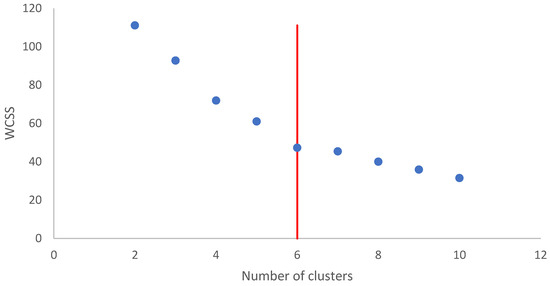

To analyze and map the structure of the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization across EU countries, we employed the K-means cluster analysis method. To perform this analysis, we first determined the optimal number of clusters using the WCSS Elbow Method and Silhouette Analysis, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2.

Determining the optimal number of clusters.

Figure 2.

Graph—method via elbow.

Using the WCSS (Figure 2) method, we identified the number of clusters to be 6 or 7 by visually estimating the largest reduction in benefit (elbow). However, this visual method can lead to over clustering [38] and was therefore further validated with the Silhouette Coefficient. The Average Silhouette Coefficient measures the compactness and separation of clusters, where higher is better. The analysis showed that the 2-cluster model achieved the highest value of the average silhouette coefficient (0.2524), while the originally proposed number of clusters of 6, only achieved an average silhouette coefficient value of 0.1988, see Table 2.

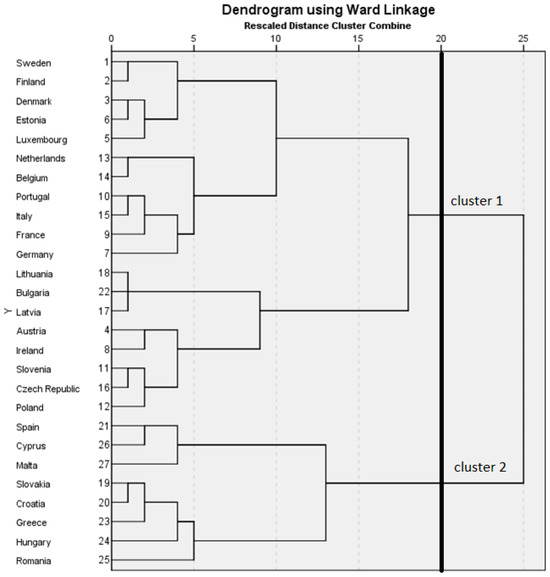

To visually verify the number of clusters identified by the Silhouette Coefficient, hierarchical clustering was performed using Ward’s method. The resulting Dendogram (Figure 3—indicating the largest jump in heterogeneity when going from 2 to 1 cluster) visually confirmed the existence of two main and stable clusters.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram.

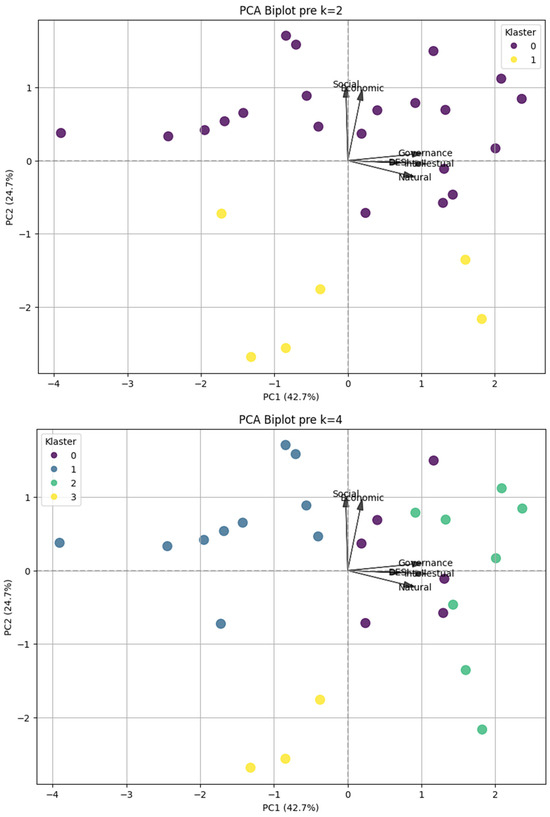

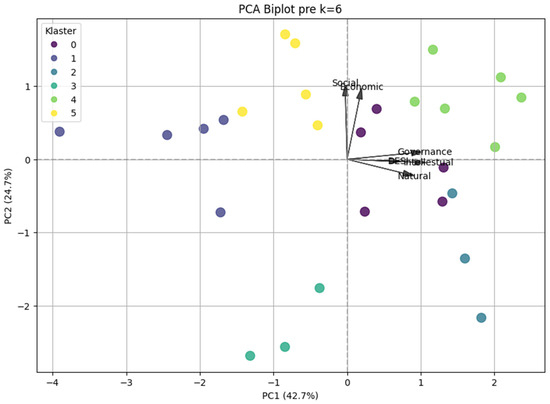

To associote the robustness and stability of the number of clusters, the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) was calculated, according to which the best number of clusters appears to be 4, where it reaches the highest value and for all other clusters. To increase the cluster dimensioning, PCA Biplot analysis was therefore performed for the number of clusters 2, 4 and 6, which represent the most potential numbers of clusters for K-means cluster analysis, see Figure 4.

Figure 4.

PCA Biplot.

The PCA Biplot for 2 clusters showed the clearest binary separation along PC1. This model divided the subjects into two groups, a high-performance cluster (positive PC1) and a low-performance cluster (negative PC1). It visually confirmed why the number of clusters 2 is the most compact, but at the same time too simple to interpret. The PCA Biplot for 6 clusters shows overlapping and mixing of points in the central space, which confirms the low Silhouette score. The PCA Biplot for 4 clusters confirms the robust hierarchy, and divides the 2 stable clusters (core groups) into four clearly distinct subgroups.

The choice of the optimal number of clusters was a critical step, in which a synthesis of several presented methodological procedures was used to maximize the compactness, stability and robustness of the model. Based on their calculations and interpretation of individual methods, the 4-cluster model appears to be an optimal compromise, providing a stable and robust four-level performance hierarchy that is stable across different clustering algorithms (ARI—extremely strong = 1, PCA Biplot is very good. Ward also supports 4-cluster visualization).

K-means cluster analysis was conducted for 4 clusters (see Table 3). This analysis enabled the identification of country groupings that exhibit similar characteristics within the examined context, while at the same time differing from one another across clusters.

Table 3.

ANOVA analysis—K-means.

The F tests should be used only for descriptive purposes because the clusters have been chosen to maximize the differences among cases in different clusters. The observed significance levels are not corrected for this and thus cannot be interpreted as tests of the hypothesis that the cluster means are equal.

Based on the K-means analysis, we identified clusters of EU countries according to the structure of individual perspectives of the Quintuple helix model and digitalization, see Table 4. All perspectives of the model, as well as digitalization, had a significant association (statistically significant) with the grouping of these clusters.

Table 4.

K-means clustering of EU countries by Quintuple Helix and DESI.

Intellectual Capital, Economic, Governance and Digitalization had an absolute association (p < 0.01 on cluster formation. Social and Natural Capital also had a significant impact (p < 0.05).

Cluster 1 can be characterized as a cluster with countries with the highest average value of Digitalization, Governance, Intellectual and Social Capital, the so-called “Nordic governance–knowledge leaders”. These countries demonstrate highly integrated innovation systems, where strong digital literacy (Intellectual Capital) and effective e-government (Governance) create a synergistic digital co-evolution. Their position is maintained thanks to sustained investments in Human Capital and Digital Infrastructure. Cluster 2, the so-called “Southern adaptive innovators”, can be characterized as a cluster with the lowest level of Digitalization, Governance, Intellectual and Social Capital. The other parameters represent average values. This group is primarily focused on market adoption and commercial use of digital technologies. Their challenge lies in achieving a balance between rapid economic growth and sustainable integration of digital public services. Cluster 3 is a group of countries with the lowest value of Natural and Economic Capital, the so-called “Southern adaptive innovators” too. The other parameters represent average values. Cluster 4 can be characterized as countries with above-average values of the examined indicators, the so-called “Eastern catching-up economies”. This group is primarily focused on market adoption and commercial exploitation of digital technologies. Their challenge lies in achieving a balance between rapid economic growth and sustainable integration of digital public services. Based on the findings, it can be observed that countries within clusters are grouped in such a way that those with a higher degree of Digitization are also characterized by a higher degree of Governance, intellectual Capital, and social Capital.

To confirm or refute the interrelationships between the individual perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization, a correlation analysis was carried out. To associate the linear relationships between the variables, we performed Pearson correlation analysis. To control for the effect of economic wealth of the country on these relationships, a partial correlation analysis was additionally performed with the control variable GDP per capita. To minimize the type I error (false discovery rate) in multiple testing, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied, for False Discovery Rate = 0.05, see Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlations analysis.

Based on the correlation analysis, it can be concluded that the individual perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model are statistically significantly interrelated. Natural Capital correlates with economic Capital (Pearson coefficient 0.459 *). Controlling for the effect of economic wealth on the relationship (Economic Capital and Natural Capital) with the control variable GDP per capita showed a much larger relationship than the original binary correlation analysis (0.503 **). Social Capital correlates with Intellectual Capital (0.676 **) and Governance (0.526 **). When controlling for the influence of economic wealth (using GDP per capita), we examined the correlations between Social Capital and both Intellectual Capital and Governance. The resulting adjusted relationship between Social Capital and Intellectual Capital was 0.574 **.

Intellectual Capital, as already mentioned, correlates with Social Capital (0.676 **), but also with Governance (0.759 **) and Digitalization (0.387 *). To enhance rigor and to account for the impact of overall economic development, we conducted a partial correlation analysis, controlling for the impact of Gross Domestic Product. The results, presented in Table 5, confirm the robustness of the key findings. While some correlations weakened (suggesting that they were partially mediated by GDP per capita), the association between Governance and overall Digitalization remained statistically significant, similar to the case of Intellectual Capital. This result is key because it suggests that strong digital readiness of Governance and Knowledge Base is not simply a by-product of a country’s wealth (GDP per capita), but reflects independent investments in institutional quality and human Capital. These pillars are thus in fact stronger and more autonomous predictors of digital success in the EU. Controlling for the correlation of economic wealth on the relationship (Intellectual Capital vs. Social Capital, Governance and Digitalization) with the control variable GDP per capita showed a relationship between Intellectual Capital and Social Capital (0.574 **) and Governance (0.642 **). Following this adjustment, no relationship between Intellectual Capital and digitalization was found. Governance, in addition to its correlation with Social and Intellectual Capital, also correlates with Digitalization (0.450 *).

When the effect of GDP per capita was accounted for, no significant relationship between Governance and Digitalization was observed. By incorporating the identified relationships among the investigated parameters—based on both the Pearson correlation coefficients and the partial correlations controlling for economic wealth of EU countries—into the hypothetical model, the statistical significance of the individual relationships can be clearly observed (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hypothetical Model –Results. *—Correlation is significant at the p < 0.05 level (2-tailed). **—Correlation is significant at the p < 0.01 level (2-tailed).

To ensure methodological rigor and minimize the risk of type I error when testing multiple correlation hypotheses, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (false discovery rate control, FDR) was applied with a level of 0.05. The aim was to associate which relationships would remain statistically significant even after this strict correction. The results of the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure are presented in Table 5. The results of the tested relationships did not reach statistical significance after applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction. This result should be interpreted in the context of the limited sample size (27 countries), which significantly reduces the statistical power of the analysis. This low number of observations has direct consequences for the stability and generalizability of the clusters. With such a ratio of variables and observations, the result of the K-means analysis may be more sensitive. Therefore, the identified clusters are primarily a descriptive typology within the EU27, and their generalizability to other regions or time periods is limited. However, given the research goal of mapping the structure of the Quintuple Helix Model pillars and Digitalization in European Union Countries, we consider the performed analyses to be significant at the first stage of testing. The results show an exceptionally strong association between the Governance and Intellectual Capital pillars with the overall DESI score. This association can be theoretically supported by the concepts of absorptive capacity and institutional environment. The Governance pillar creates the basic institutional prerequisites for the effective adoption and diffusion of digital technologies. Countries that have robust and trustworthy digital public services make it easier for businesses and citizens to integrate digital solutions. The Intellectual Capital pillar is, in turn, a key sourcing mechanism of our theory. It provides the necessary Human Capital and skills that are essential for the use of technologies and their conversion into economic value (association between Intellectual Capital and Digitalization).

5. Discussion

The analysis reveals that digitalization is positively associated with both Governance (r = 0.450) and Intellectual Capital (r = 0.387). These findings underscore that Digital Transformation is not merely a technological development but a fundamental organizational shift [1,3] with direct implications for knowledge management and societal progress [4,5]. Accordingly, the success of digitalization in EU countries depends critically on the quality of Governance and the strength of Intellectual Capital, which collectively form the foundation for a knowledge-based economy and the concept of Democracy 5.0, toward which Industry 4.0/5.0 is advancing [6,14]. Although it should be mentioned that by including the control variable GDP per capita, this relationship does not appear significant. Countries in Cluster 1, including Sweden and Finland, exemplify this synergy, where high levels of digitalization, governance, and intellectual Capital create a dynamic, knowledge-intensive environment [25].

The Quintuple Helix model is based on the premise that further advancement and the development of knowledge and innovation require co-evolution with knowledge democracy [13]. Our findings confirm that well-governed and democratic systems (Governance) provide optimal conditions for the growth of intellectual Capital [24], as evidenced by the exceptionally strong, statistically significant positive relationship between Intellectual Capital and Governance (r = 0.642, with control variable GDP per capita). These results align with the theoretical framework of the Quintuple Helix model, which emphasizes governance and Intellectual Capital [15,25,37,46,47,48].

Hauseberg et al. [2] highlight the importance of the “human dimension” in digital transformation, a notion supported by our results, which show that Social Capital is significantly correlated with Intellectual Capital (r = 0.574, with control variable GDP per capita) and governance (r = 0.526). These findings are consistent with the shift from “Cluster 1” up to “Cluster 4” knowledge production in an applied context of transdisciplinarity, social responsibility, and reflexivity [17,18,19,20]. Strong Social Capital, representing the civil society perspective within the Quadruple Helix model, serves as a democratic foundation and a prerequisite for the functioning of complex innovation systems, reflecting the theory of knowledge democracy [14].

The Quintuple Helix model extends the original Helix frameworks by adding a new perspective of Natural Capital, representing the fifth helix, with the aim of achieving ecological transformation [13,16]. Based on the results of this study, it can be concluded that this fifth helix of the Quintuple Helix model does not exhibit a statistically significant relationship with Digitalization, Governance, or Intellectual Capital. It demonstrates a statistically significant association only with Economic Capital (r = 0.503, with control variable GDP per capita). This finding supports the theory that environmental challenges are regarded as potential drivers of innovation [13]. A methodological nuance is necessary when interpreting the findings regarding Natural Capital. The original bivariate correlations showed only weak, non-significant associations between Natural Capital and key factors such as Digitalization and Governance. This finding that ecological stocks do not have a direct association with digital readiness or governance quality is consistent with the assumption of decoupling in advanced EU economies. However, partial correlation analysis controlling for GDPpc revealed that this relationship increased. This increase is crucial because it indicates that GDPpc acted as a suppressor variable, masking a stronger, true positive association between Natural and Economic Capital in the bivariate relationship.

Interpreting the Natural Capital pillar requires addressing the observed decoupling from Digital Readiness (DESI). The weak initial bivariate correlation suggests that in mature EU economies, digital progress does not automatically translate into significant improvements in ecological stock measures. We argue that this linkage is not direct, but primarily mediated by Eco-Innovation proxies: Digitalization functions as a technological platform, but tangible ecological gains are realized only through active investment in and adoption of specific green technologies. Furthermore, our partial correlation analysis highlights that GDP per capita acts as a suppressor variable, masking a stronger underlying relationship between Ecological Capital pillar and other Capital pillars. This confirms that economic wealth is a necessary prerequisite for financing the required Eco-Innovations and supportive governance frameworks that effectively convert digital potential into real ecological outcomes.

A correlational association between Economic Capital and Natural Capital can characterize the successful implementation of ecological strategies in countries, or a compromise between economic growth and ecological goals. In the most economically developed countries (cluster 1), this strong association probably indicates the successful implementation of green strategies. These states can afford to invest in costly green innovations, digital monitoring systems and strict environmental regulation that enable higher economic performance while reducing environmental impact. On the contrary, in other countries it may indicate a compromise within the ecological goals in the area of environmental sustainability. Overall, however, this positive relationship may indicate the successful implementation of ecological practices in EU countries. Therefore, digitization should be used as a catalyst for mitigating this compromise across the entire Union. Policies should aim to facilitate the transfer of knowledge and technology (Intellectual Capital) so that digital tools help transform economic models towards sustainable growth, thus strengthening synergies between the pillars of Economic and Natural Capital in line with the goals of the Quintuple Helix model.

Our findings reinforce the theoretical framework, which posits that the full potential of digital transformation and innovation (Industry 4.0 and 5.0) depends on the co-evolution and integration of diverse forms of knowledge and innovation [24]. The disparity between Cluster 1 and Cluster 4 (highest vs. lowest levels of digitalization and governance) confirms the hypothesized model, in which development is constrained in countries with weak Intellectual Capital and Governance. For lagging countries, investing in the quality of Public Administration and Human Capital is therefore crucial, as these factors have proven to be structurally decisive for successful digital transformation. The overall findings suggest that the structure of the Quintuple Helix model and Digitalization in the EU can be understood as a system of mutually reinforcing factors.

6. Conclusions

The research question of this study is: “What are the clusters of European Union countries based on their profiles within the perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model (Intellectual Capital, Governance) and the level of digitalization, and how do these factors relate to one another?” Based on the conducted analysis, we identified three homogeneous clusters of EU countries with similar profiles in terms of the individual perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization levels. These factors are key to differentiating EU member states and represent statistically significant interconnections and structure.

The data analysis clearly confirmed that the individual perspectives of the Quintuple Helix model and digitalization are closely interrelated and play a crucial role in differentiating EU countries. The findings indicate that countries leading in Intellectual Capital and Governance also excel in Digital Transformation. Conversely, countries with low levels of digital transformation exhibit deficiencies in Governance as well as in Social and Intellectual Capital.

Governance and intellectual potential were found to be the most strongly interconnected factors within the Quintuple Helix model in relation to Digital Transformation. However, Social Capital also emerged as a critical foundation for the development of both of these pillars.

The limitations of this study primarily relate to its focus on static measurements, which map the current structure of the relationships among the variables examined in EU countries but do not capture their dynamics. While providing an essential snapshot of the current situation, this methodological constraint necessitates future work. Therefore, future research will build upon these findings and focus on dynamic testing of the relationships among the examined variables, aiming to deepen the understanding of this complex topic.

Our findings clearly demonstrate that the correlation between digitalization and the quality of governance is largely spurious, as it is primarily driven by the economic wealth of the country (GDPpc). Therefore, it is appropriate to implement targeted strengthening between Governance and Intellectual Capital, which has been shown to be robust and independent of GDPpc, within EU countries, for example, by investing in digital education within public administration. The high level of connection between Natural Capital and Economic Capital, and at the same time the low level of connection with other variables (including digitalization), suggests that business sectors and R&D institutions should start actively implementing projects focused on eco-innovation for a successful Green Digital Transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.; methodology, E.L.; software, E.L.; validation, E.L., M.O. and Z.Š.; formal analysis, M.O.; investigation, E.L.; resources, E.L.; data curation, E.L. and M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L. and M.O.; writing—review and editing, E.L., M.O. and Z.Š.; visualization, E.L.; supervision, E.L.; project administration, E.L.; funding acquisition, E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak grant number VEGA 1/0513/25 and KEGA 016TU Z-4/2025.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak and processed within grants VEGA 1/0513/25 and KEGA 016TU Z-4/2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morakanyane, R.; Grace, A.; O’Reilly, P. Conceptualizing digital transformation in business organizations: A systematic review of literature. In Proceedings of the 30th Bled eConference, Bled, Slovenia, 18–21 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hausberg, J.P.; Liere-Netheler, K.; Packmohr, S.; Pakura, S.; Vogelsang, K. Research streams on digital transformation from a holistic business perspective: A systematic literature review and citation network analysis. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 89, 931–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braganza, A.; Brooks, L.; Nepelski, D.; Ali, M.; Moro, R. Resource management in big data initiatives: Processes and dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V.; Frattini, V. The role of digital technologies in open innovation processes: An exploratory multiple case study analysis. R&D Manag. 2018, 50, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.; Grigoroudis, E. Helix trilogy: The triple, quadruple, and quintuple innovation helices from a theory, policy, and practice set of perspectives. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 2272–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. Publicising food: Big data, precision agriculture, and co-experimental techniques of addition. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gano, G. Starting with universe: Buckminster Fuller’s design science now. Futures 2015, 70, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, A.K.; Flyverbom, M.; Hilbert, M.; Ruppert, E. Big data: Issues for an international political sociology of data practices. Int. Political Sociol. 2016, 10, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, R.W. Big data, urban governance, and the ontological politics of hyperindividualism. Big Data Soc. 2017, 4, 205395171668253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, D. Seeing like a satellite: Remote sensing and the ontological politics of environmental security. Secur. Dialogue 2017, 48, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagermann, H.; Helbig, J.; Hellinger, A.; Wahlster, W. Recommendations for Implementing the Strategic Initiative INDUSTRIE 4.0: Securing the Future of German Manufacturing Industry; Final Report of the Industrie 4.0 Working Group; Forschungsunion: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D.F.J. The quintuple helix innovation model: Global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Dezi, L.; Gregori, G.; Calo, E. Smart environments and techno-centric and human-centric innovations for industry and society 5.0: A Quadruple helix innovation system view towards smart, sustainable, and inclusive solutions. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 12, 926–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carayannis, E.; Kostis, P.; Dinçer, H.; Yüksel, S. Quality function deployment-oriented strategic outlook to sustainable energy policies based on quintuple innovation helix. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 6761–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Grigoroudis, E.; Campbell, D.F.; Meissner, D.; Stamati, D. The ecosystem as helix: An exploratory theory-building study of regional co-opetitive entrepreneurial ecosystems as Quadruple/Quintuple Helix Innovation Models. R&D Manag. 2018, 48, 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, M.; Limoges, C.; Nowotny, H.; Schwartzman, S.; Scott, P.; Trow, M. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies; Sage: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny, H.; Scott, P.; Gibbons, M. Re-Thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Hens, L.; Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P. Trans-disciplinarity and growth. Nature and characteristics of trans-disciplinary training programs on the human-environment interphase. J. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, H.; Scott, P.; Gibbons, M. Mode 2 revisited: The new production of knowledge. Minerva 2003, 41, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “Mode 2” to a triple helix of university-industry-government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. Democracy of climate and climate for democracy: The evolution of quadruple and quintuple helix innovation systems. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 12, 2050–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.F.J.; Carayannis, E.G. Epistemic governance in higher education. In Quality Enhancement of Universities for Development; SpringerBriefs in Business: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. “Mode 3” and “quadruple helix”: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 46, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemlin, S.; Allwood, C.M.; Martin, B.R. Creative Knowledge Environments: The Influences on Creativity in Research and Innovation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The World in 2025: Rising Asia and Socio-Ecological Transition; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/research/social-sciences/pdf/the-world-in-2025-report_en.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Haberl, H. (Eds.) Socioecological Transitions and Global Change: Trajectories of Social Metabolism and Land Use; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Archibugi, D.; Coco, A. A new indicator of technological capabilities for developed and developing countries (ArCo). World Dev. 2004, 32, 629–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J.; Srholec, M.; Knell, M. The competitiveness of nations: Why some countries prosper while others fall behind. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1595–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism; Penguin: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F. Mode 3 knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation systems: Twenty-first-century democracy, innovation, and entrepreneurship for development. In Mode 3 Knowledge Production in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems: 21st-Century Democracy, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship for Development; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, E. A quintuple helix model for foresight: Analyzing the developments of digital technologies in order to outline possible future scenarios. Front. Sociol. 2023, 7, 1102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Rakhmatullin, R. The quadruple/quintuple innovation helixes and smart specialisation strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth in Europe and beyond. J. Knowl. Econ. 2014, 5, 212–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivo-oja, J.R.L.; Stenvall, J. A critical reassessment: The European Cloud University Platform and new challenges of the quartet helix collaboration in the European university system. Eur. Integr. Stud. 2022, 16, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boly, V.; Morel, L.; Marche, B.; Monticolo, D.; Camargo, M.; Hörlesberger, M. Ecosystem practices for regional digitalization: Lessons from three European provinces. In European Perspectives on Innovation Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Loredo, J.L.; Palma-Ruiz, J.M.; Saiz-Álvarez, J.M. Digital transformation of the quadruple helix: Technological management interrelations for sustainable innovation. In Entrepreneurship as Practice: Time for More Managerial Relevance; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, G.; Diglio, A.; Piccolo, C.; Pipicelli, E. A reduced Composite Indicator for Digital Divide measurement at the regional level: An application to the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 190, 122461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index (GSCI) 2024. SOLABILITY. 2024. Available online: https://solability.com/the-global-sustainable-competitiveness-index/downloads (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Digital Economy and Society Index. 2024. Available online: https://digital-decade-desi.digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/datasets/desi/metadata (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Sevgi, H. Analysis of the digital economy and society index (DESI) through a cluster analysis. Trak. Üniv. Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2021, 23, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M. How do commodity futures respond to Ukraine–Russia, Taiwan Strait and Hamas–Israel crises?—An analysis using event study approach. Stud. Econ. Financ. 2025, 42, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bánhidi, Z.; Dobos, I.; Nemeslaki, A. What the overall Digital Economy and Society Index reveals: A statistical analysis of the DESI EU28 dimensions. Reg. Stat. 2020, 10, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussabayev, R.; Mussabayev, R. Comparative analysis of optimization strategies for K-means clustering in big data contexts: A review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09819. [Google Scholar]

- Selvamuthu, D.; Das, D. Analysis of correlation and regression. In Introduction to Probability, Statistical Methods, Design of Experiments and Statistical Quality Control; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 359–393. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. 2025. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-20 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Minaei-Bidgoli, B.; Parvin, H.; Alinejad-Rokny, H.; Alizadeh, H.; Punch, W.F. Effects of resampling method and adaptation on clustering ensemble efficacy. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2014, 41, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štofkova, J.; Štofko, S.; Loučanova, E. Possibilities of using e-learning system of education at universities. In INTED2017 Proceedings, Proceedings of the 11th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 6–8 March 2017; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2017; pp. 6965–6972. [Google Scholar]

- Loučanová, E.; Olšiaková, M.; Štofková, J. Ecological innovation: Sustainable development in Slovakia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).