Abstract

With the growing emphasis on sustainable development, organizations and government agencies are increasingly incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into their strategic agendas. However, previous research has primarily examined ESG performance, stakeholder engagement, and financial outcomes in isolation, overlooking the systemic role of employee perceptions and psychological responses. To address this shortcoming, this study integrated social identity theory and social exchange theory to explain how ESG practices influence green innovation behavior through organizational pride. Furthermore, drawing on organizational climate theory, we explored the moderating role of innovation climate in this relationship. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze data from 346 employees across diverse Chinese companies, enabling us to capture the overall structure of the relationship rather than isolated causal relationships. Our results show that all three dimensions of ESG practices significantly enhance organizational pride, which in turn stimulates green innovation, highlighting the indirect, systemic relationship between ESG and innovation outcomes. Organizational climate is an important contextual variable influencing both individual behavior and organizational performance. When organizations have a favorable innovation climate, employees are more likely to translate their pride into concrete innovative behaviors. While the direct impact of ESG (S) and ESG (G) on green innovation has not been confirmed, the mediating role of organizational pride and the moderating role of innovation climate highlight the dynamic interplay between psychological and organizational subsystems. This study conceptualizes ESG practices, organizational pride, and innovation climate as interconnected subsystems within a broader organizational system, providing a systems-based perspective for sustainability research. It advances theoretical understanding of how sustainability initiatives spread through psychological and organizational mechanisms and offers practical insights for policymakers and decision makers seeking to promote long-term green innovation.

1. Introduction

To address global climate change and social injustice, companies are reshaping their employees’ social mission and environmental awareness through internal social innovation (CSE). They are also integrating social goals into their products and work systems through leadership values and organizational culture, thereby earning the trust of employees and the public [1]. The establishment of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in 2006 marked a pivotal moment in institutionalizing the ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) framework, which has since become fundamental to securing long-term investment and promoting sustainable business practices [2]. ESG practices are pivotal in achieving long-term corporate value and sustainability as they mitigate adverse environmental and social impacts while maximizing positive contributions to stakeholders [3].

Employees—the cornerstone of any enterprise—play a decisive role in driving innovation, which is vital for organizational success and sustainability [4]. In the new economy, human capital has emerged as a strategic resource for firms seeking sustainable competitive advantage. As core members of organizations, employees are not only the creators of corporate culture but also key stakeholders who contribute significantly to daily operations [5]. Song’s research found that corporate ESG performance can improve the efficiency of human capital investment, enhance product competitiveness, and promote corporate reputation, thereby further strengthening the positive impact on human capital investment efficiency [6].

According to emotional appraisal theory, such pride develops through continuous cognitive assessments of organizational actions and initiatives, shaping employees’ overall attitudes and behaviors [7]. Organizational pride—a psychological state arising from positive evaluations of one’s organization—is closely tied to employees’ perceptions of its reputation and social contributions. ESG practices significantly enhance employees’ organizational pride, which in turn fosters innovation [4]. In both corporate practice and academic research, the notion of “green” has attracted increasing attention, not only in exploring ESG practices but also in understanding how organizational pride encourages employees’ innovative engagement [8]. Under increasing internal and external pressure, companies are integrating green practices into their organizational processes and promoting green innovations covering material recycling, energy efficiency, environmentally friendly design, and ecological management to improve productivity and profitability, and to mitigate resource depletion and environmental pollution during technological transformation, thereby achieving sustainable competitiveness [9]. Theories of emotional events and person–environment fit suggest that, beyond individual creativity and intrinsic motivation, innovation development is also influenced by the organizational climate [10].

While prior ESG literature has primarily concentrated on financial performance, disclosure, and ratings, this study advances the discourse by adopting a people-centric perspective that emphasizes employees as core agents shaping organizational sustainability outcomes. Specifically, this study integrated social identity theory [11] and social exchange theory [12] to explain how ESG practices influence green innovation behavior through organizational pride. Furthermore, drawing on organizational climate theory [13], it explores the moderating role of innovation climate in this relationship. Employees derive self-identity and a sense of emotional belonging from their organization’s reputation and values. When an organization practices positive social responsibility (such as ESG practices), employees feel a sense of pride (organizational pride) and further exhibit more positive behaviors (such as green innovation). Positive organizational behaviors (such as fulfilling ESG responsibilities) foster a sense of support and trust in employees, leading them to reciprocate with positive behaviors (such as green innovation). Furthermore, organizational innovation climate, as a contextual resource, can enhance the effective utilization of these intangible assets. ESG practices can stimulate psychological resources (organizational pride), which, according to the resource-based view (RBV) [14], can be translated into green innovation.

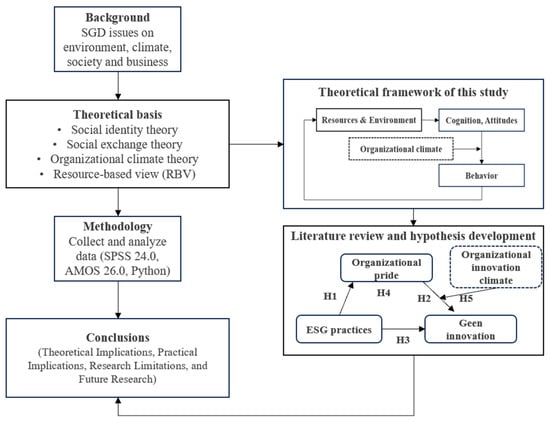

Based on the preceding literature review and theoretical discussion, the overall research framework of this study is summarized as shown in Figure 1. This study aims to address the theoretical limitations of previous research, which has focused on people-centered perspectives. Based on a structural model of resources, environment, cognition, attitudes, and behavior, it explores how the interaction between organizations, employees, and the environment can jointly promote sustainable development. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of deeply integrating ESG practices into corporate management, arguing that this internalization process can enhance employee pride in environmental protection, resource conservation, and sustainable development, thereby stimulating green innovation behaviors. This study has important theoretical and practical implications.

Figure 1.

Research framework and conceptual model of the study.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypothesis Formulation

2.1. ESG Practices and Organization Pride

ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) serves as a framework for assessing a company’s sustainable development capabilities and long-term risk resilience. Through transparent management of environmental impacts, social responsibility, and governance practices, it guides companies from simply pursuing profit maximization to focusing on long-term survival and sustainability, thereby profoundly influencing corporate strategies and the integration of internal and external resources [15]. With increasing awareness among consumers and employees regarding their rights and environmental threats, businesses are increasingly adopting ESG management principles to balance profit generation with social responsibility [16]. Research on the relationship between ESG disclosures and corporate financial performance shows that although ESG disclosures have a positive impact on financial results, they tend to be more pronounced when companies have been established for more extended periods, have media attention, or possess other advantages compared to industry peers, attracting ESG focused investors [17]. In the study by Liang et al. (2025), the study used 1500 A-share listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen from 2012 to 2022 as samples, used the number of green technology innovations (GINUM) and the quality of green technology innovations (GICIT) as measures of corporate green innovation capabilities, and explored the dynamic relationship between ESG performance and green innovation by constructing a DiD model and a benchmark regression model [18].

In an in-depth study conducted by Lee and Yoo. (2023) [2], a survey of employees of large listed companies in South Korea was carried out for an in-depth analysis of various factors and data to explore the relationship between ESG management and employees’ willingness to leave. The study also examined organizational pride, which was significantly influenced by ESG management.

In addition, corporate participation in social responsibility activities not only provides employees with situational resources by creating a positive and responsible organizational image, but also enhances their sense of self-worth and identity, thereby stimulating, developing, and maintaining their employees’ organizational pride in social interactions in the workplace [8]. Additionally, in the study by Youn and Kim (2022) on the intersection of corporate social responsibility, organizational pride, and word meaning, their research demonstrated that corporate social responsibility initiatives positively influence organizational pride, affirming that social responsibility significantly enhances organizational pride [19]. The social identity theory posits that individuals seek positive social recognition and validation from their group memberships, enhancing pride. That is to say, social identity can be defined as the process by which an individual derives positive meaning, emotions, and values from being a part of a particular social group [20]. In line with this framework, the relationship between organizations and employees is mutually beneficial. Existing literature suggests that companies, to maintain their internal and external viability, can use strategies like sustainable development initiatives to increase employee organizational pride. Therefore, based on social identity theory, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1:

ESG practices have a positive impact on organizational pride. 1a: Environmental practices have a positive impact on organizational pride. 1b: Social practices have a positive impact on organizational pride. 1c: Governance practices have a positive impact on organizational pride.

2.2. Organization Pride and Green Innovation

Green innovation refers to activities aimed at improving existing products, processes, and organizational management systems to achieve a dual win of economic and environmental benefits, with the overarching goal of sustainable development. Specifically, green innovation enables the sustainable growth of businesses and their products by improving production technologies, products, and service management, integrating environmental protection practices with economic growth. The ultimate aim is to align both ecological sustainability and economic growth in a way that fosters the long-term, cyclical development of enterprises [21]. Companies seeking a sustainable competitive advantage in the global market must innovate technologically and managerially. Sustainable process innovation, on the other hand, focuses on minimizing negative environmental impacts by integrating sustainable production processes [22].

According to self-determination theory, pride influences individual behavior and control, motivating individuals to engage in meaningful actions and improve their work performance [23]. Repeated research has shown that there is a close connection between positive emotions and innovative behavior [24]. In their studies on organizational pride, innovation behavior, and organizational commitment, scholars such as Jing and Kang. (2022) found that organizational pride plays a significant role in influencing innovative behavior [4]. Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2:

Organizational pride has a positive impact on green innovation.

2.3. ESG Practices and Green Innovation

In recent years, a growing body of research has examined the relationship between ESG engagement, environmental strategies, and green innovation across different contexts. Several meta-analyses and international empirical studies have demonstrated a generally positive but context-dependent relationship between ESG practices and innovation outcomes. Friede et al. (2015), in their meta-analysis of more than 2000 empirical studies, reported that approximately 90% found a non-negative association between ESG and firm performance, with innovation often serving as a mediating factor [25]. Bansal and Song (2017) emphasized that sustainability-oriented strategies enhance firms’ long-term learning and adaptive capabilities across industries [26], while Wagner (2010) and Halme et al. (2009) concluded that proactive environmental strategies can effectively stimulate process and product innovation [27,28].

Building upon this global evidence, regional studies have provided complementary insights, particularly from emerging markets such as China. For instance, Javeed et al. (2022) explored how corporate environmental strategies and management practices influence green innovation, confirming the positive impact of proactive sustainability efforts on innovation performance [29]. Similarly, Lin et al. (2022) examined board diversity and its relationship with green economic outcomes, finding that gender-diverse boards significantly promoted green innovation, and analyses of more than 200 Chinese manufacturing firms and A-share listed companies further demonstrated that both the quality and quantity of green innovation increased in organizations with gender-diverse sustainability committees [30].

Extending this perspective, Liu, Zhang and Cho (2023) investigated corporate environmental disclosure and green innovation in China’s heavily polluted industries, revealing that transparent disclosure practices complement internal innovation mechanisms and strengthen firms’ green innovation capacity [31]. Collectively, these findings are consistent with stakeholder theory, which posits that organizations must account for the interests of customers, employees, suppliers, financial institutions, and broader social groups to ensure long-term sustainability and legitimacy [32]. Moreover, the characteristics and values of top management—reflected in their cognitive orientations, leadership styles, and commitment to ESG goals—play a pivotal role in shaping these innovation outcomes [33,34].

Taken together, both international and regional studies converge on the conclusion that ESG engagement fosters innovation, though the strength and pathways of this relationship vary across institutional and cultural contexts. This convergence underscores the importance of integrating global theoretical insights with local empirical realities to fully understand how ESG practices translate into sustainable and innovation-driven organizational performance.

Given these theoretical foundations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3:

ESG practices have a positive impact on green innovation. 3a: Environmental practices have a positive impact on green innovation. 3b: Social practices have a positive impact on green innovation. 3c: Governance practices have a positive impact on green innovation.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Organizational Pride

While pride is primarily an emotional manifestation of personal psychology, organizational pride is also an emotional bond between employees and organizations since it is influenced by both the internal feelings of employees and the environment of the workplace [35]. Research by Dong and Zhong (2021) explored the variables of responsible leadership, innovative behavior, and organizational pride, revealing a significant influence of organizational pride on innovation outcomes [36]. Huh and Lee (2023) [37] researched ESG awareness, organizational identity, innovative behavior, and organizational citizenship behaviors through a quantitative analysis. Including surveys of employees from South Korean companies with 50 or more employees, they explored the relationship between ESG activity awareness and organizational identity. Their findings revealed a significant impact between these two variables, indicating that ESG awareness has a notable effect on organizational identity. According to research by Malokani et al. (2024), corporate pride also significantly improves employees’ environmental behaviors as an intermediary element [38]. Furthermore, as scholars said in previous discussions that studies on corporate social responsibility practices demonstrate that positive corporate social responsibility perceptions can significantly enhance employee innovation capabilities [39]. The theory of perceived external prestige (PEP) further supports this, suggesting that employees ‘perceptions of how outsiders view their organization’s status and reputation can influence their sense of pride and, consequently, their behavior. Over time, building a strong reputation is crucial for organizational success [40]. Building on the concept of PEP, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4:

Organizational pride mediates the relationship between ESG practices and green innovation. H4a: The positive effect of environmental practices on green innovation is mediated by organizational pride. H4b: The positive effect of social practices on green innovation is mediated by organizational pride. H4c: The positive effect of governance practices on green innovation is mediated by organizational pride.

2.5. The Regulatory Role of Organizational Innovation Climate

Organizational innovation climate, a product of cognitive conditions, enables employees to recognize the critical importance of innovation for the development and progress of an organization. To ensure long-term sustainability, businesses must foster intrinsic creativity among employees, clarify innovative thinking, and promote innovative behaviors [10]. Other scholars have characterized the innovation climate as the direction in which organizational innovation practices are oriented. As a key driver of employees’ creative thinking, the innovation climate fosters an environment conducive to creativity. By offering support and encouragement for innovative behaviors, organizations can create a work context that enhances the overall innovation climate [41]. Tian and Wang (2023) conducted an in-depth study on sustainable leadership, knowledge sharing, organizational innovation climate, and frugal innovation, their research, which included surveys of employees in China’s manufacturing and service sectors, concluded that a higher level of organizational innovation climate amplifies the impact of knowledge sharing on frugal innovation [42]. Similarly, Xiao et al. (2020) explored the relationship between employees’ organizational fit, green organizational climate, and other factors, their findings demonstrating that green organizational climate moderates the relationship between perceived internal status and voluntary green behavior, indicating an indirect effect on these variables [43]. Further studies by You et al. (2022) examined the relationships between organizational innovation climate, employee innovative behavior, and their research on employees from Chinese emission control enterprises and 13 companies in Guangdong Province revealed that organizational innovation climate positively influenced employees’ innovative behaviors [44].

Building upon these findings, the present study further explains why the innovation climate strengthens the relationship between organizational pride and green innovation. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory, we argue that an innovation-supportive climate serves as a contextual amplifier that transforms employees’ emotional attachment into action-oriented innovation [23]. When employees experience strong organizational pride, they are intrinsically motivated to contribute to their organization’s goals. However, the extent to which this pride translates into innovative behavior depends on the surrounding work environment. A strong innovation climate provides psychological safety, autonomy, and resource support—conditions that enable employees to take risks, experiment with new ideas, and express creativity aligned with sustainability objectives.

In such environments, employees who are proud of their organization are more likely to channel that pride into green innovation behaviors, as they feel encouraged and supported to act on their intrinsic motivation. Conversely, in a weak innovation climate characterized by rigid hierarchies or low tolerance for risk, the motivational effect of organizational pride may remain suppressed. Thus, an innovation climate plays a facilitative and catalytic role in converting emotional energy (organizational pride) into creative energy (green innovation), enhancing the overall ESG-driven innovation process.:

Hypothesis 5:

Organizational innovation climate moderates the relationship between organizational pride and green innovation.

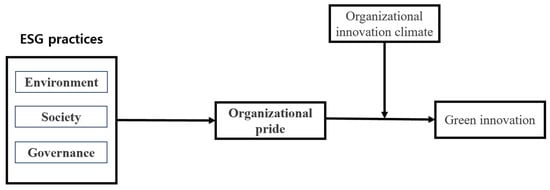

Based on the above theoretical background and hypotheses, we propose the research model illustrated in Figure 2. This model conceptualizes ESG practices—comprising environmental, social, and governance dimensions—as key organizational drivers that enhance employees’ organizational pride. Drawing from social identity theory, we posit that such pride serves as an intrinsic motivational mechanism, translating ESG efforts into green innovation behaviors. Furthermore, guided by contingency theory and the innovation climate literature, we hypothesize that the organizational innovation climate moderates the relationship between organizational pride and green innovation, such that a supportive climate strengthens this positive linkage.

Figure 2.

Research model.

3. Methods

We adopted a systems-oriented approach to analyze the complex interrelationships among the variables in our study. Specifically, we used SPSS 26.0 to conduct demographic and correlation analyses to gain a preliminary understanding of the systematic connections between the variables. We then used AMOS 24.0 to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement scales and evaluate the overall model fit, as well as the direct and indirect paths within our research framework. By adopting this systems perspective, our analysis transcends isolated effects and captures the integrated structure and dynamics of ESG practices, organizational pride, and innovation climate. Multiple regression analyses were used to validate the moderating impact of innovation climate, providing the methodological rigor consistent with a systems approach.

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The purpose of this study was to objectively assess the effectiveness of ESG practices across various Chinese industries, including services, education, and construction. The inclusion of these industries was intentional to reflect the heterogeneous ESG maturity across sectors. This broader sampling design enables a more comprehensive examination of how ESG practices diffuse across industries with differing environmental intensities and how employees’ psychological and behavioral responses—such as organizational pride and innovation engagement—manifest in these contexts.

To comprehensively examine the effects of ESG practices on employee behavior, we employed both online and offline survey methods for data collection. The study involved 408 participants from across China, representing a range of industries, with data collected between 4 June and 8 July 2024. Prior to survey administration, all participants received a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives and the significance of their contributions, both orally and in writing, ensuring transparency and informed consent in line with ethical research standards. After screening for completeness and validity, 346 usable responses were obtained, yielding an effective response rate of 84.8%.

The participants represented a diverse demographic profile: 51.2% were female, 85.2% were aged 50 or younger, and 81.8% possessed at least a college-level education. Detailed demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Although a portion of respondents held education levels below university, their inclusion was intentional to assess perceptual variance—that is, how ESG understanding and engagement differ across demographic and educational groups. To ensure comprehension, respondents were provided with brief contextual information on ESG concepts before answering the questionnaire. Moreover, approximately 71.4% of participants were employed in private enterprises, allowing the study to reflect differences in ownership structures and managerial practices. Overall, the sample represents a relatively young, well-educated, and diverse workforce, suitable for analyzing how ESG practices, organizational pride, and innovation climate interact across various industrial and institutional contexts.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of participants.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

ESG Practices: ESG practices refer to the management and attention to social responsibility, internal and external environments, and corporate governance aimed at fostering transparent mechanisms for achieving sustainable and harmonious development between the enterprise and the environment, as well as enhancing long-term resilience. This study utilized a 14-item scale based on Rabiei, Arashi, and Farrokhi (2019) [45], Cavallo (2020) [46], and Barbosa, et al. (2023) [47], measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items included: “I believe that the company I work for has implemented corporate environmental education policies” and “I believe that the company I work for has implemented measures to promote gender diversity (equal opportunities for men and women)”.

Green Innovation: Green innovation refers to the improvements or developments of new product designs, processes, technologies, and organizational management practices aimed at ensuring sustainable and harmonious development with the environment. For example, activities such as recycling, reducing emissions, and minimizing resource usage per unit of product output. This concept was measured using an 8-item scale developed by Chen et al. (2006) [48] and Zhang et al. (2020) [49], with responses captured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Sample items included: “The company I work for selects materials with the least environmental impact for product development or design” and “The company I work for effectively reduces harmful substances or waste emissions during manufacturing”.

Organizational Pride: Organizational pride refers to the positive emotions that arise when employees perceive the company’s performance as exceeding expectations or meeting higher societal standards. It displays the favorable opinions and sentiments that workers have about their company. Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), this study assessed organizational pride using a 5-item scale created by Lee and Cho (2013) [50], Cable and DeRue (2002) [51], Oo, Jung, and Park. (2018) [52], Zafar and Suseno (2024) [39]. For example, “I feel proud to introduce the company I work for to others” as well “I feel proud to be a member of the company I work for”.

Organizational Innovation Climate: Organizational innovation climate refers to the perception of members regarding the organization’s orientation towards innovation [42]. This study employed a 4-item scale developed by Oke, Prajogo and Jayaram (2013) [53] and Tian et al. (2023) [42], measured using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Sample items included: “The company I work for recognizes and rewards employees for their creativity and innovative ideas” and “In the company I work for, employees work in cross-functional teams, where open and free communication is encouraged. Employees are recognized and rewarded for their creativity and innovative ideas”. The specific measurement items for each construct are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variable Measurement.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Reliability and Validity Assessment

To examine the potential for standard method bias (CMB) in self-report and single-source data, we conducted a Harman single-factor test using the unrotated exploratory factor analysis tool in SPSS 26. Sample adequacy was confirmed (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin = 0.940), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 5389.126, degrees of freedom = 465, p < 0.001), indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. The first unrotated factor explained 31.996% of the total variance, which was below the critical threshold of 50%. Therefore, standard method bias was not a significant concern in this study.

We performed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement model, focusing on the perceived structures of ESG environmental, ESG social, ESG governance, Organizational pride, Organizational innovation climate, and green innovation. As shown in Table 3, the model demonstrated a strong fit with the data, with the following fit indices: CMIN/DF = 1.167, p < 0.01, RMR = 0.046, GFI = 0.928, CFI = 0.988, NFI = 0.922, TLI = 0.986, IFI = 0.988, RFI = 0.912, and RMSEA = 0.022. All factor loadings were significant at p < 0.001, indicating robust relationships between the items and their respective constructs. The composite reliabilities for all constructs exceeded the threshold of 0.70, indicating strong internal consistency across the scales: ESG environmental = 0.847, ESG social = 0.836, ESG governance = 0.764, Organizational pride = 0.854, Green innovation = 0.877, and Organizational innovation Climate = 0.840. Additionally, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs met the benchmark of 0.50, with values as follows: ESG environmental = 0.525, ESG social = 0.561, ESG governance = 0.495, Organizational pride = 0.541, Green innovation = 0.505, and organizational innovation climate = 0.568, ensuring adequate convergent validity. To verify discriminant validity, the Fornell and Larcker (1981) [54] criterion was applied, which requires the square root of each construct’s AVE to be greater than the correlations between the constructs. This further confirmed the model’s discriminant validity. These findings validate the reliability and validity of the measurement model, providing a solid foundation for its application in subsequent hypothesis testing.

Table 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations between key variables in the study: ESG environmental, ESG social, ESG governance, green innovation, Organizational pride, and Organizational innovation climate. The results revealed significant correlations between independent and dependent variables, strengthening the theoretical relationships. Specifically, ESG environmental showed substantial positive correlations with green innovation (r = 0.310, p < 0.01), Organizational pride (r = 0.308, p < 0.01), and Organizational innovation climate (r = 0.339, p < 0.01), indicating a strong connection between environmental practices and organizational outcomes. Similarly, ESG social was significantly correlated with green innovation (r = 0.228, p < 0.01), Organizational pride (r = 0.362, p < 0.01), and Organizational innovation climate (r = 0.400, p < 0.01), suggesting a significant relationship between social practices and organizational results. Furthermore, Green innovation was significantly correlated with Organizational pride (r = 0.344, p < 0.01) and Organizational innovation climate (r = 0.333, p < 0.01), emphasizing the role of green innovation in enhancing organizational pride and fostering an innovation-friendly atmosphere. Finally, organizational pride showed a significant correlation with organizational innovation climate (r = 0.367, p < 0.01), highlighting the reciprocal relationship between pride and the innovation climate within the organization. Although the correlations between ESG environmental, ESG social, and ESG governance exceeded 0.8, multicollinearity diagnostics indicated no issues with multicollinearity. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values (all less than 10) and tolerance values (all greater than 0.1 but less than 1.0) further confirmed this robustness, providing a solid foundation for the study’s conclusions.

Table 4.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

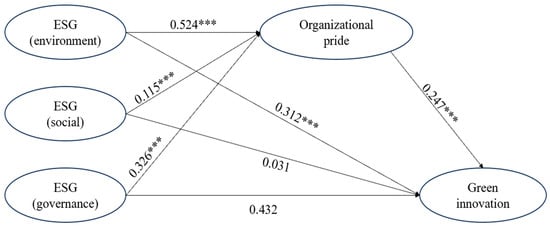

Based on the results shown in Table 5 and Figure 3, the results showed a good overall model fit (CMIN/DF = 2.005, GFI = 0.912, CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.930, IFI = 0.942, RMSEA = 0.054). Environmental responsibility (ESG-E), social responsibility (ESG-S), and corporate governance (ESG-G) all had a significant positive impact on organizational pride (OP) (β = 0.524, p < 0.001; β = 0.155, p < 0.001; β = 0.326, p < 0.001), respectively), supporting Hypotheses H1a, H1b, and H1c. Furthermore, organizational pride significantly promoted green innovation (GI) (β = 0.247, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H2. In terms of direct effects, environmental responsibility (ESG-E) exhibited a significant positive impact on green innovation (β = 0.312, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H3a. However, social responsibility (ESG-S) and corporate governance (ESG-G) both showed insignificant impacts on green innovation (β = 0.031, p > 0.1; β = 0.042, p > 0.1), respectively. Therefore, Hypotheses H3b and H3c were not supported. Social responsibility (ESG-S) focuses more on responsibilities to external groups such as communities, employees, and supply chains, often implemented through projects such as philanthropy, education, and inclusive development, and may not directly translate into a company’s green innovation investment. This could be a result of the frequent outward orientation and symbolic nature of social initiatives, which prioritize stakeholder connections and image-building over internal innovation processes. Employees may regard social activities as ancillary to their core tasks, limiting the extent to which such programs encourage creativity or environmental innovation. Corporate governance (ESG-G), on the other hand, emphasizes norms such as board structure, information transparency, and stakeholder protection. However, rather than operating at the behavioral level, these processes usually operate at the strategic or structural level. Through mechanisms like resource allocation, leadership accountability, and strategic investment decisions, governance frequently has an indirect effect on innovation.

Table 5.

Analysis results of Hypothesis 1 to Hypothesis 3.

Figure 3.

Direct Effects (Path Analysis Results). *** p < 0.001.

Based on the results shown in Table 6, the mediating role of organizational pride in the relationship between ESG environmental, ESG social, ESG governance, and green innovation was analyzed as follows:

Table 6.

The mediates Effects of Organizational Pride.

For H4a (Environmental → Organizational Pride → Green Innovation), both the direct effect (β = 0.039, p < 0.05) and the indirect effect (β = 0.075, p < 0.05) were statistically significant. This indicates that organizational pride plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between environmental factors and green innovation.

For H4b (Social → Organizational Pride → Green Innovation), the direct effect (β = 0.042) was not significant, but the indirect effect (β = 0.051, p < 0.05) was significant. This finding suggests a full mediation effect, where organizational pride fully explains the impact of social factors on green innovation.

For H4c (Governance → Organizational Pride → Green Innovation), the direct effect (β = 0.167) was not significant, while the indirect effect (β = 0.069, p < 0.05) was significant. This also indicates a full mediation effect, showing that organizational pride fully mediates the impact of governance factors on green innovation. To verify the mediating role of organizational pride and ensure the robustness of our results, we conducted a study using the bootstrap resampling method built into AMOS 24, with 5000 bootstrap samples and a bias-corrected percentile method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) [55]. The indirect effect was considered significant when the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. The results indicate that organizational pride significantly mediated the relationship between ESG practices and green innovation. Specifically, the indirect effect was significant in the ESG(E) → OP → GI (β = 0.075, 95% CI [0.053, 0.145]), ESG(S) → OP → GI (β = 0.051, 95% CI [0.019, 0.072]), and ESG(G) → OP → GI (β = 0.069, 95% CI [0.078, 0.261]) paths. Since all confidence intervals excluded zero, the mediation effect was confirmed, supporting the robustness of the findings.

In summary, the research results suggest that organizational pride plays a full mediating role in the relationship between social and governance factors and green innovation, while it serves as a partial mediator between environmental factors and green innovation. This underscores the crucial role of organizational pride in transforming the impacts of ESG dimensions into enhanced green innovation.

The moderating effect occurs when the relationship between the independent variable (X) and the dependent variable (Y) changes depending on the level of the moderator variable (Z). In this case, organizational pride (X) serves as the independent variable, green innovation (Y) as the dependent variable, and organizational innovation climate (Z) as the moderator variable. The analysis included organizational pride, organizational innovation climate, and their interaction term (X * Z) in the regression model.

Table 7 shows the results of the adjustment effect of the organizational innovation climate. In Model 1, which only included organizational pride, the direct influence on green innovation (β = 0.348, t = 6.698, p < 0.001) was noticeable, explaining 11.9% of the variance in green innovation (R2 = 0.119). This result indicates that organizational pride directly and positively affects green innovation.

Table 7.

The moderating effect of the organizational innovation climate.

In Model 2, organizational innovation climate was added as the moderator. Both organizational pride (β = 0.255, t = 4.665, p < 0.001) and organizational innovation climate (β = 0.239, t = 4.470, p < 0.001) showed significant main effects on green innovation, with the total explained variance increasing to 16.7% (R2 = 0.167). This indicates that both organizational pride and organizational innovation climate positively affect green innovation.

Model 3 included the interaction term between organizational pride and organizational innovation climate to test the moderating impact. The interaction term (β = 0.198, t = 3.981, p < 0.001) was statistically significant, suggesting that the organizational innovation climate moderates the relationship between organizational pride and green innovation. Including the interaction term improves the model’s explanatory power by 3.8%, bringing the total explained variance to 20.5% (R2 = 0.205).

Organizational pride and organizational innovation climate were mean-centered before creating the interaction term to mitigate potential multicollinearity issues. This method adjusts the variables by subtracting their respective means, helping to reduce multicollinearity. The significant interaction effect indicates that the impact of organizational pride on green innovation varies depending on the level of organizational innovation climate, confirming the moderating effect and supporting Hypothesis 5.

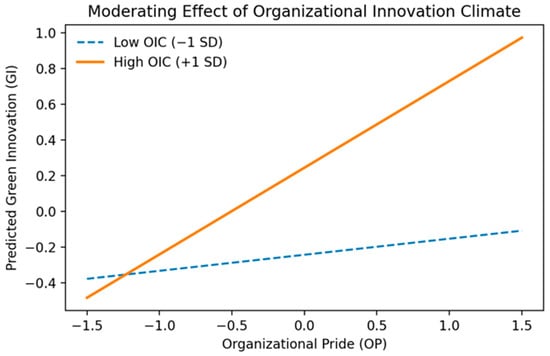

The interaction term between organizational pride and organizational innovation climate was significant (β = 0.198, p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 4, organizational pride had a stronger positive impact on green innovation under a high level of organizational innovation climate, confirming the moderating effect hypothesis.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of the organizational innovation climate.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several critical theoretical contributions by empirically validating the structural relationships proposed in the five key hypotheses. First, in line with Hypothesis 1, we confirm that ESG practices significantly impact organizational pride. This finding aligns with previous studies [40] and adds nuance by showing that environmental, social, and governance practices jointly and positively enhance employees’ sense of pride. By examining ESG as a multidimensional construct, this study enriches our understanding of how each component can generate distinct psychological outcomes at the employee level.

Conceptually, this research extends the theoretical understanding of the organizational pride mechanism beyond the traditional CSR framework. Prior research (e.g., Schaefer et al., 2024) has established that CSR engagement enhances employees’ organizational pride, which in turn fosters prosocial or organizational citizenship behaviors [7]. However, the present study broadens this perspective by embedding organizational pride within the multi-dimensional ESG framework, which encompasses not only social responsibility, but also the environmental and governance domains. This multidimensionality enables a richer exploration of how different ESG dimensions trigger pride and shape employee behaviors differently. The results reveal that employees’ emotional responses to governance integrity and environmental responsibility are distinct yet complementary drivers of green innovation, underscoring the importance of viewing ESG as an integrated structure rather than as a simple extension of CSR’s social dimension.

Second, consistent with Hypothesis 2, organizational pride positively influences green innovation. Prior research has typically examined pride in the contexts of general innovation or organizational commitment. By focusing specifically on sustainability-driven innovation, this study demonstrates that pride is not merely a positive emotion, but a key motivational resource that drives employees to engage in environmentally responsible and innovative behaviors. Contextually, this study situates the pride mechanism within the green innovation domain, a critical but relatively underexplored setting. Unlike prior CSR studies that emphasize reputation enhancement or employee loyalty, our findings reveal that ESG-driven pride motivates employees to actively participate in innovation-oriented sustainable practices, particularly when supported by a strong innovation climate. This contextualization bridges the psychological mechanism of pride with the practical pursuit of environmental innovation, providing a novel perspective for understanding the human and motivational foundations of ESG-driven innovation.

Third, the findings regarding Hypothesis 3 reveal a more differentiated pattern than initially expected. Environmental practices (H3a) directly and significantly foster green innovation, but social (H3b) and governance practices (H3c) do not exhibit significant direct effects. Instead, their influence emerges indirectly through organizational pride. This nuanced result highlights the heterogeneous contributions of different ESG dimensions to sustainable development outcomes, thus advancing ESG research. For example, Subramanian, Jain and Bhattacharyya (2024) found that the E dimension of ESG had a significant direct effect, while the S and G dimensions, influenced by institutional isomorphism pressures, were more likely to exert long-term effects through indirect channels (organizational culture and internal structure) [56]. Liang et al. (2025) empirically demonstrated that they significantly promoted green technology innovation, while the effects of the S and G dimensions were significant only in industries with high levels of environmental regulation or complex governance [18]. This suggests that not all ESG dimensions operate through the same pathway: environmental practices can have immediate effects. In contrast, social and governance practices require employees’ psychological identification and pride as mediators to translate into innovation. Fourth, through Hypothesis 4, the mediating role of organizational pride between ESG practices and green innovation was empirically confirmed. By situating pride as the bridge between corporate practices and innovation, this research extends identity-based motivation theory into the ESG context. It shows that employee pride is a powerful socio-emotional channel, vital for social and governance practices whose impacts are indirect. Finally, Hypothesis 5 was supported, demonstrating that the organizational innovation climate significantly moderates the relationship between organizational pride and green innovation. A supportive innovation climate amplifies the translation of pride into green innovation, illustrating the interactive role of both psychological mechanisms (employee pride) and contextual mechanisms (innovation-supportive environment).

Taken together, these findings underscore the originality and significance of this study within the growing literature on ESG, employee behavior, and organizational innovation. While prior research has examined how ESG or CSR initiatives influence employee attitudes and innovative behaviors [7,31], the present study advances this discussion by adopting a systems-based and employee-centered perspective that integrates multiple analytical levels into a unified framework. Unlike much of the existing literature that focuses primarily on external stakeholders, disclosures, or financial outcomes, this research emphasizes the internal mechanisms through which ESG practices foster green innovation by shaping organizational culture, employee psychology, and innovation climate.

First, this study offers a theoretical integration by linking ESG’s three core dimensions—environmental, social, and governance—with both psychological (organizational pride) and contextual (innovation climate) mechanisms. This holistic framework captures the interdependent and dynamic nature of ESG systems rather than treating each dimension or behavioral response in isolation. Specifically, organizational pride functions as a mediating mechanism, while innovation climate serves as a moderating factor, together forming a system dynamics perspective that connects micro-level emotions with macro-level sustainability practices.

Second, this research extends the existing ESG and CSR literature by situating the analysis within the Chinese context, where ESG implementation is still evolving under unique institutional and cultural conditions. While prior studies have largely focused on Western firms with mature ESG structures, this study provides empirical insights from Chinese enterprises, demonstrating how differentiated ESG dimensions exert systemic impacts on innovation in an emerging market environment.

Third, this study contributes methodologically by operationalizing ESG from an employee perception perspective, capturing how individual-level cognition and emotion aggregate into collective innovation behaviors. This bottom-up lens complements existing top-down evaluations of ESG performance and offers a more nuanced understanding of the human mechanisms underlying sustainability-oriented innovation.

In sum, the novelty of this study lies not in proposing an entirely new topic, but in developing an integrated, context-sensitive, and employee-centered analytical model that connects ESG’s multidimensional structure to individual motivation and organizational innovation within a unified systems framework. By bridging micro-level psychological processes with macro-level sustainability outcomes, this research provides a comprehensive and dynamic understanding of how organizations can translate ESG engagement into emergent and enduring innovation performance.

5.2. Practical Implications

This research also offers practical insights for policymakers and business leaders committed to sustainability. First, companies need to shift ESG from an “external disclosure activity” to a “management system embedded in daily operations and workflows”. This emphasizes that ESG should be integrated into the business cycle and employees’ daily functions, rather than simply serving as an external compliance indicator, to achieve true sustainable transformation. When employees perceive that their organization integrates ESG into daily work systems (such as compensation, work goals, and ethical decision-making), their sense of well-being and work meaning significantly increases. Therefore, companies should institutionalize ESG behavioral standards in system design, incentives, and performance management, making sustainable value a part of the “daily work experience”. Research on how to internalize ESG into governance systems, monitoring mechanisms, and daily operational practices using a systems management approach will need to be conducted. In countries with high governance quality, the public has greater trust in companies with ESG transparency. Therefore, increasing the awareness and social penetration of ESG practices is a crucial management practice for companies, both internally and externally. Second, the strong connection between organizational pride and green innovation highlights the need for psychologically grounded and systemically designed leadership strategies that align individual identity with the organization’s sustainability goals. Recognition programs, ESG-focused communications, and identity-based integration can reinforce these dynamics. Third, the differentiated impact of each ESG dimension highlights the systemic complexity of ESG: environmental initiatives may lead to immediate innovation benefits, while social and governance initiatives can foster long-term pride and commitment. Therefore, managers should design ESG strategies that target specific dimensions rather than viewing ESG as a monolithic concept. Finally, the moderating role of innovation climate suggests that organizations are dynamic systems; a transparent, flexible, and supportive climate can ensure that ESG-driven pride translates into emerging innovation outcomes. By adopting this systems view, ESG can become a strategic driver of sustainable competitive advantage.

5.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, reliance on self-reported survey data may introduce bias and limit measurement scope. Second, the findings are based on a sample of Chinese employees in a specific industry, primarily young, educated private sector employees, which limits the study’s generalizability across different cultural and institutional contexts. Third, the lack of objective ESG performance indicators limits the scope of analysis to employee perceptions. Furthermore, the study’s cross-sectional design limits its ability to draw clear causal inferences. Nevertheless, the results provide a useful foundation for understanding the underlying mechanisms of the relationship between ESG practices and innovation outcomes. Future research could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to further establish causal relationships. Furthermore, research should address these issues by expanding to different cultural and industry contexts and integrating objective ESG and innovation performance data. Combining employee perceptions with external ESG assessments will provide a deeper understanding of how ESG practices influence firm innovation in different institutional contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and X.Z.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, H.K.; investigation, X.Z.; resources, H.K.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z., Y.L. and H.K.; writing—review and editing, H.K.; visualization, Y.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duquesnois, F.; Karar, R. Prise de décisions des copreneurs et création de valeur en cse en contexte de crise pandémique: Le cas de biontech fondée par un couple de scientifiques-entrepreneurs. Vie Sci. de L’entreprise 2025, 225, 115–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Yoo, T.Y. The Relationship between ESG Management Perception and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Effect of Organizational Pride and The Moderating Effect of ESG Management Cynicism. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 62, 109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.L.; Yang, K.Z. The Spillover Effect of ESG Performance on Green Innovation—Evidence from Listed Companies in China A-Shares. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B.F.; Kang, M. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Employee’s Strengths-based Leadership on Employee Innovative Behavior. Manag. Mod. 2022, 42, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Tu, S. An empirical study on corporate ESG behavior and employee satisfaction: A moderating mediation model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Corporate ESG performance and human capital investment efficiency. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.D.; Cunningham, P.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R. Employees’ positive perceptions of corporate social responsibility create beneficial outcomes for firms and their employees: Organizational pride as a mediator. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2575–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, A.; Qureshi, M.I.; Iftikhar, M.; Obaid, A. The impact of GHRM practices on employee workplace outcomes and organizational pride: A conservation of resource theory perspective. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2024, 46, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, B.; Shad, M.K.; Lai, F.W.; Waqas, A. Empirical analysis of ESG-driven green innovation: The moderating role of innovation orientation. Manag. Sustain. Arab Rev. 2024, 3, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. A Study on the Influence of Organizational Innovation Climate on Employee’s Innovation Performance. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Mental Health, Education and Human Development (MHEHD 2022), Dalian, China, 27–29 May 2022; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The climate for service: An application of the climate construct. Organ. Clim. Cult. 1990, 1, 383–412. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, F. Transformational leadership, organizational innovation, and ESG performance: Evidence from SMEs in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.; Oh, J.; Kim, Y. The effects of ESG activities on job satisfaction, organizational trust, and turnover intention. Internet Electron. Trade Res. 2022, 22, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.F.; Xie, G.X. ESG disclosure and financial performance: Moderating role of ESG investors. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Cao, Z.; Tang, S.; Hu, C.; Zhang, M. Evaluating the Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance on Green Technology Innovation: Based on Chinese A-Share Listed Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.H. Corporate social responsibility and hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of organizational pride and meaningfulness of work. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Qasim, N.; Farooq, O.; Rice, J. Empowering leadership and employees’ work engagement: A social identity theory perspective. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Luo, Y.; Hu, S.; Yang, Q. Executives’ ESG cognition and enterprise green innovation: Evidence based on executives’ personal microblogs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1053105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, T.; Songjiang, W.; Jamil, K.; Naseem, S.; Mohsin, M. Measuring green innovation through total quality management and corporate social responsibility within SMEs: Green theory under the lens. TQM J. 2023, 35, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory applied to work motivation and organizational behavior. SAGE Handb. Ind. Work Organ. Psychol. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 2, 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha, P.; Nivedhitha, K.S.; Raghuvanshi, J. The perceived CSR-innovative behavior conundrum: Towards unlocking the socio-emotional black box. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 161, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.-C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from CSR. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. The role of corporate sustainability performance for economic performance: A firm-level analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Halme, M.; Laurila, J. Philanthropy, integration or innovation? Exploring the three strategies for sustainable corporate responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.A.; Zhou, N.; Cai, X.; Latief, R. How does corporate management affect green innovation via business environmental strategies? Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1059842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Lin, S.; Zhong, Q. Board gender diversity and corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Cho, C.H. Corporate environmental information disclosure and green innovation: The moderating effect of CEO visibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 3020–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. A review ESG performance as a measure of stakeholder’s theory. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2023, 27 (Suppl. S3), 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shaer, H.; Zaman, M.; Albitar, K. CEO gender, critical mass of board gender diversity and ESG performance: UK evidence. J. Account. Lit. 2024, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.; Bensalem, N. Are gender-diverse boards eco-innovative? The mediating role of corporate social responsibility strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijepcevic, M.; Popovic Ševic, N.; Krstic, J.; Rajic, T.; Rankovic, M. Exploring the Nexus of Perceived Organizational CSR Engagement, Job Satisfaction, Organizational Pride, and Involvement in CSR Activities: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhong, L. Responsible leadership fuels innovative behavior: The mediating roles of socially responsible human resource management and organizational pride. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 787833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, B.J.; Lee, H.Y. Impact of ESG activities on employee behavior: Through organizational trust and organizational identification. Korean Manag. Rev. 2023, 52, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malokani, D.K.A.K.; Mumtaz, S.N.; Junejo, D.; Shaikh, D.H.; Hassan, N.; Darazi, M.A.; Malokani, M. The Green HRM Impact on Employees’ Environmental Commitment: Mediating Effect of Organizational Pride. Metall. Mater. Eng. 2024, 30, 470–480. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, H.; Suseno, Y. Examining the effects of green human resource management practices, green psychological climate, and organizational pride on employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Organ. Environ. 2024, 37, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M. Unlocking the Power of ESG: How Employee’s ESG Perception Shapes Job Satisfaction through the Enchanting Prism of Perceived External Prestige. Bus. Educ. Rev. 2023, 38, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Noopur; Dhar, R.L. The role of high performance human resource practices as an antecedent to organizational innovation: An empirical investigation. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 43, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wang, A. Sustainable leadership, knowledge sharing, and frugal innovation: The moderating role of organizational innovation climate. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231200946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Mao, J.Y.; Huang, S.; Qing, T. Employee-organization fit and voluntary green behavior: A cross-level model examining the role of perceived insider status and green organizational climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M. The effect of organizational innovation climate on employee innovative behavior: The role of psychological ownership and task interdependence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 856407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, M.R.; Arashi, M.; Farrokhi, M. Fuzzy ridge regression with fuzzy input and output. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 12189–12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, B. Functional relations and Spearman correlation between consistency indices. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2020, 71, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.D.S.; Crispim, M.C.; da Silva, L.B.; da Silva, J.M.N.; Barbosa, A.M.; Morioka, S.N. How can organizations measure the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria? Validation of an instrument using item response theory to capture workers’ perception. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 3607–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, G.; Feng, T.; Yuan, C.; Jiang, W. Green innovation to respond to environmental regulation: How external knowledge adoption and green absorptive capacity matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.G.; Cho, Y.H. The effects of pride and respect on the relationship between abusive supervision of supervisors and follower’s organizational citizenship behaviors and turnover intention. Korean J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 37, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, E.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, I.J. Psychological factors linking perceived CSR to OCB: The role of organizational pride, collectivism, and person–organization fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; Prajogo, D.I.; Jayaram, J. Strengthening the innovation chain: The role of internal innovation climate and strategic relationships with supply chain partners. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, B.; Jain, N.K.; Bhattacharyya, S.S. Exploring the direct impact of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors on organizational innovation output and institutional isomorphism: A study in the context of multinational life sciences organizations. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).