Abstract

In a dynamic modern business environment, project management has been receiving significant attention as a way to improve organizational practices and keep pace with market needs in various industries. Consequently, a growing focus was placed on competent individuals who will successfully manage projects no matter their primary area of specialization, and it became necessary to determine the correct knowledge, skills and abilities, as well as to formalize them in a way to be used for evaluating the potential candidates, choosing the right ones for the job and helping them to grow over time. As project management competencies have been broadly discussed in the literature, the aim of this paper was to examine the key research interests of the authors in the field in the last two decades to identify the main research directions and areas for filling in the research gaps. A systematic literature review was conducted on 487 academic papers published and indexed in the WoS database between 2004 and 2024. The results of the keyword co-occurrence analysis highlighted four prominent research directions—the evolving role of project manager and project management competence development, integrating knowledge management strategies for project success, leadership and emotional intelligence as pillars of advanced project management and innovative approaches to project management in the construction sector. Development of specific competencies and their formalization, cross-sector analyses, and ways to upskill the individuals working in single- or multi-project domains are recognized as future research directions.

1. Introduction

Globalization and economic unpredictability have significantly altered the dynamics of production chains, therefore requiring different organizational arrangements from companies and leading them towards projectization and recognition of the value of conducting business within temporary forms of work based on projects to achieve better adaptability and ensure competitive advantage in the market [1]. Projects are enhancing performance in the short term and creating value in the long term through faster acceptance of new technologies, more frequent organizational transformations and development of new products [2]. Consequently, this increases the demand for highly competent individuals who can take into account the combination of social, cultural and organizational project environments during implementation [3] and have a good understanding of technological solutions, features, products, services and capabilities that are aimed to be produced by the project [2]. They should possess a mixture of general and domain-specific knowledge, technical and interpersonal skills and abilities to understand the connection of the project with the general strategy of the organization, keep the focus on the benefits and impacts that should be achieved (even during the early stages), maintain project performance, and achieve project success while dealing with the challenges that might be encountered in this way of working [2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], as mistakes can cause serious damage [11]. Furthermore, the competence of the professionals in the dynamic environment are also not static [12], and to maintain a competitive advantage, it is essential for the organization to understand the changing competence requirements and ensure resilience by rapid adaptations and recovery from disruptions [13].

The concept of competence does not have one generally accepted definition [14]. According to different authors, competence includes knowledge [15,16,17,18], abilities [19], skills [15,16,17,18,19], attitudes influencing the work performed measured against standards and potentially improved through learning and training [15,16,17] and personal characteristics [18]. In their Iceberg model, Spencer & Spencer [20] divide basic characteristics of behavior and performance into five parts: (a) motives (direct behavior towards a goal or action), (b) traits (physical and mental characteristics of a person), (c) attitudes, values and self-confidence, (d) knowledge necessary for understanding a certain topic and (e) skills needed to perform a particular task. According to them, competencies can be categorized into two groups—visible (knowledge and skills) and invisible (motives, traits and attitudes)—while skills can be further categorized into two groups: hard (cognitive in nature and task-oriented) [21] and soft (individual behavior and successful interpersonal interaction, including emotional intelligence) [22]. According to Crawford [23], the competence of an individual is determined by a combination of three main parts—input (knowledge and skills that an individual brings to a project), personal (essential attributes of an individual to complete a specific job) and output competencies (evident performance which can be presented in the workplace). In addition, in Crawford’s integrated competency model [24] competencies are classified into (a) those that depend on characteristics (attribute-based), such as knowledge (basic knowledge and understanding of tasks), skills (the ability to perform tasks based on qualifications and experience), behavior and key personality characteristics (motives/characteristics/self-concept for the individual to be able to do the job), and (b) those that depend on performance (performance-based)—the ability to perform tasks within the required profession up to the expected level defined by the workplace. According to Struková and Bašková [17], competencies can also be transferable (applicable in various professions) and nontransferable or profession-specific. While many conceptualizations exist, the most common division in the literature is the KSA model, which includes [25,26,27] (a) knowledge as a theoretical and/or practical understanding of data or information acquired through education or practice; (b) skills as the use of data or information with mental, verbal or manual skill; and (c) ability as the capacity to achieve a given goal based on mental and physical qualities to perform given activities.

However, despite the shift of the focus on people from being marginal [28] to extensively studied and acknowledged, research performed in relation to project management qualification, and certification programs among scholars and practitioners to identify key competencies required and track the trends of their change, it is evident that a comprehensive approach is still missing [29,30,31]. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to contribute to the field through a systematic literature review of available articles published and indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) database on the topic of project management competencies in the last two decades, to investigate key research interests of the authors and identify the main research themes as well as areas which could fill in the gaps that are recognized in the literature. For this purpose, the authors defined two main research questions:

RQ1.

What are the current directions in research on project management competencies?

RQ2.

What are the potential future directions in the research of project management competencies?

The rest of the paper is organized in three chapters—the description of the research methodology and collected data; a summary of the findings within clusters; and a discussion, with concluding remarks, including limitations of the research and suggestions for future research directions in the field at the end.

2. Research Methodology and Collected Data

In this paper, a systematic literature review was conducted as prescribed in the guidelines proposed by Callahan [32] and Torraco [33], while the sample for the bibliometric and content analysis was selected in accordance with the PRISMA principles [34] recommended for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-Analyses (see Supplementary Materials). The initial search performed on 30 December 2024 covered articles published between 2004 and 2024 and indexed in WoS, recognized as one of the most impactful repositories of academic research, with rigorous indexing standards and high-quality coverage [35]. As the research relied on a single database, which may limit the comprehensiveness of the results due to variations in coverage boundaries, the authors tried to mitigate the risk by checking the key influential articles across other relevant sources, confirming that their absence did not affect the thematic structure identified. Additionally, to ensure an integrative approach and capture all relevant publications in the defined time period, the following search string was applied to scan titles, abstracts and keywords: TS = “project management” AND “competenc*”. The asterisk (*) was used to broaden the search results by finding variations of a word, as well as singular/plural forms (e.g., competency, competence, competencies, competences, competence elements, etc.).

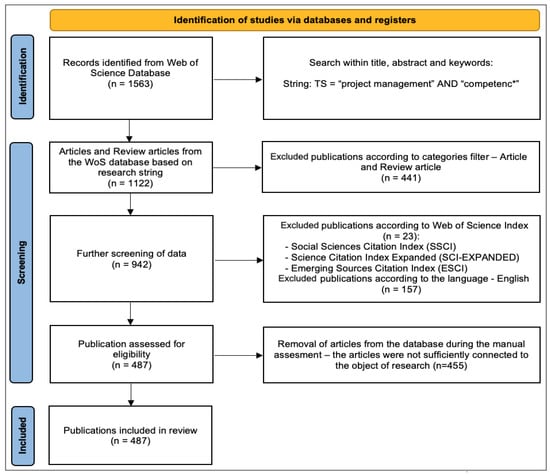

The initial search resulted in 1563 articles retrieved in accordance with the defined search parameters, after which the sample was filtered in several steps using inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Figure 1). In the first step, the search was restricted to the publications according to categories—articles and review articles—as central in research impact, resulting in 1122 articles. In the second step, the search was restricted according to Web of Science Index—SSCI, SCI-EXPANDED and ESCI—and language (English), ensuring a certain standard of scholarly rigor, and reliable and consistent foundation for analysis. This step resulted in 942 articles. The third step involved a detailed manual assessment by the authors. During this step, the authors eliminated articles after checking the titles, abstracts, and keywords and, in cases of doubt, reading bodies of the articles, followed by discussion and reaching a consensus on the alignment of the articles with the research topic to ensure the attention was on project management and project management competence. At the end of this step, 455 papers were removed and were not considered in the remaining stages of the analysis as they were not sufficiently connected to the object of research.

Figure 1.

Steps conducted during the selection process based on PRISMA principles.

The bibliometric and content analysis was performed on the remaining 487 articles using VOS viewer (ver. 1.6.20), a software solution intended for constructing and visualizing bibliographic networks. The tool mapped the author’s keywords by representing the frequency of their occurrence (circle size) and the relationship between them (links). The threshold for inclusion into the analysis was set at a minimum of three occurrences per keyword and their connections [36,37], with the goal of identifying the actual and potential future relationships between the topics by focusing on the written content of the publications [37].

Additionally, since the software does not differentiate between singular and plural forms or variations in spelling of the same keyword, the words were manually standardized using a Thesaurus within the VOS viewer. Finally, keywords unrelated to the research parameters were removed from further analysis—research process-related keywords (e.g., assessment, content analysis, factor analysis, grounded theory), geographic indicators irrelevant to this research (e.g., Lithuania, Malaysia, South Africa), or overly generic terms lacking thematic specificity (e.g., profile, roles).

Based on the results obtained with VOSviewer (ver. 1.6.20), the authors color-coded the articles to analyze them within the appropriate cluster. In some cases, articles belonged to more than one cluster based on the keywords used.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Information About the Articles

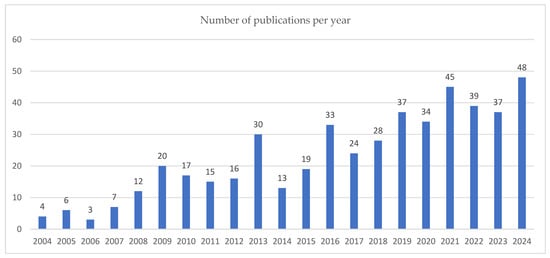

The analyzed articles were published in the period 2004–2024 with the first notable growth in 2009, and there has been a fluctuating but overall increasing trend in publications since 2009 to the highest number in 2024. The distribution of published articles by year shows that 10.68% of articles were published between 2004 and 2009, 18.69% between 2010 and 2014, and 28.95% between 2015 and 2019, while the majority, 41.68%, were published between 2020 and 2024 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Published articles by year (2004–2024).

A quarter of the observed articles (25.87%) were published in the following five journals (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Journals according to the frequency of publication.

3.2. Bibliometric and Content Analysis and Discussion

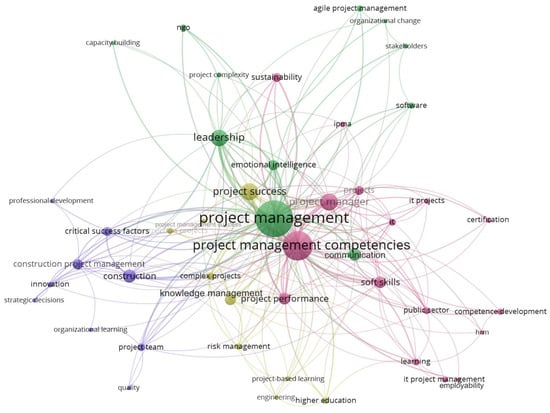

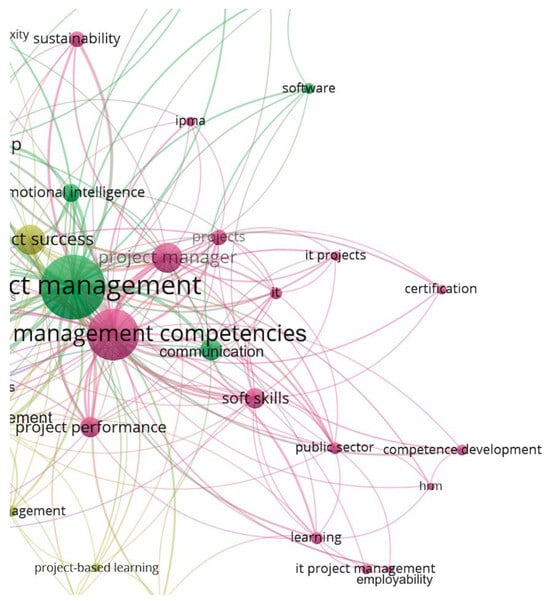

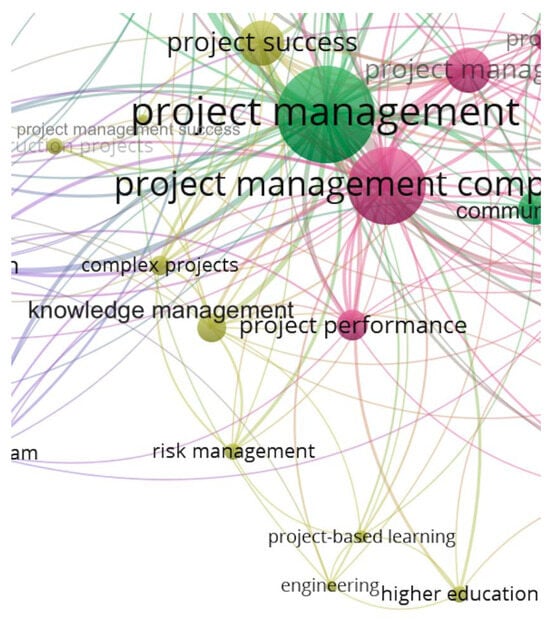

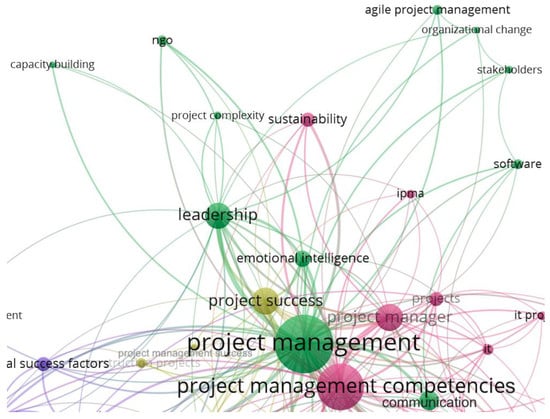

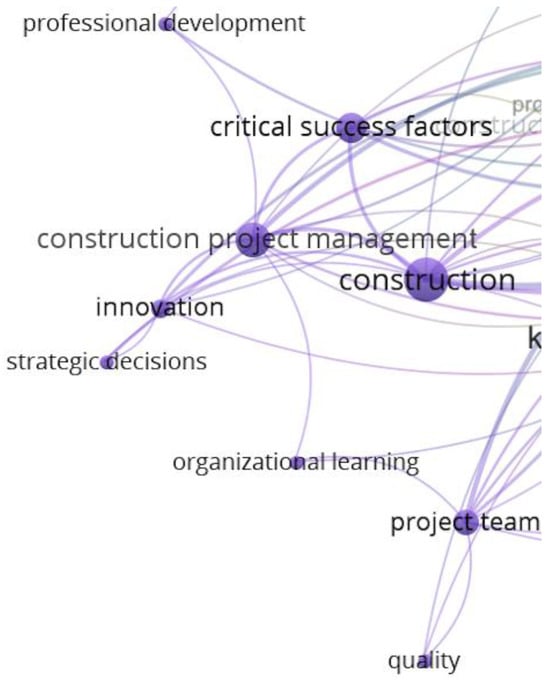

The bibliometric analysis identified four distinct clusters of author keywords representing research areas emerging from the observation of project management and competence (see Figure 3). Keywords with a high degree of correlation appeared within the same cluster as they were connected to the same research topic [38]. The cluster names were assigned by the authors, based on the frequency of the occurrence of the keywords, and the cluster colors were adjusted using Paul Tol’s muted palette to ensure they could be perceived by individuals with color blindness, as recommended by Katsnelson (Table 2) [39].

Figure 3.

Network visualization of author keyword co-occurrence.

Table 2.

Keywords within each cluster.

Rose cluster: The evolving role of project manager and project management competence development included 16 keywords: project management competencies, project manager, soft skills, project performance, projects, sustainability, learning, public sector, competence development, certification, IT projects, IPMA, IT project management, IT, HRM and employability.

Olive cluster: Integrating knowledge management strategies for project success included nine keywords: project success, knowledge management, complex projects, higher education, risk management, construction projects, project-based learning, project management success, and engineering.

Green cluster: Leadership and emotional intelligence as pillars of advanced project management included 11 keywords: project management, leadership, emotional intelligence, communication, NGO, software, agile project management, stakeholders, project complexity, capacity building, and organizational change.

Indigo cluster: Innovative approaches to project management in the construction sector included nine keywords: construction, construction project management, critical success factors, innovation, project team, professional development, quality, organizational learning and strategic decisions.

A detailed overview of the clusters is given in the following chapters (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7) with the most relevant articles referenced.

3.2.1. Rose (The Evolving Role of Project Manager and Project Management Competence Development)

Constant change, including the adoption of innovative technological tools and interdisciplinary impact of business processes, resulted in project management approaches becoming increasingly attractive for many organizations [40]. Concepts, standards and competence in the field significantly matured over time; however, issues connected to leadership, weak connection and alignment with organizational goals, shortening project deadlines, and shifts in priorities still pose a significant risk of costly project failure [41]. Projects are often used for development of new products or services that provide a chance for the organization to expand its revenue base, achieve competitive advantage and ensure expected performance, and also to improve the existing products, services, resources or potential of the organization, but also to implement the regulatory requirements [42,43]. The increasing popularity of the project management profession is associated with the more complex requests and growing pressure on individuals in leading project roles as they are no longer responsible only for the execution of a specific task but their job includes managerial aspects aligned with organization’s strategic needs [44]. Project managers should therefore build competencies which are going to add both economic and social value to the organization and stakeholders [45]. It becomes essential to understand the characteristics composing the ideal project manager profile, mapping their specific competencies and investing in their development and improvement to ensure a wide understanding of the various areas to be coordinated in a way to achieve satisfactory project results [46,47,48]. Therefore, companies must ensure there are required project management competencies on corporate and individual levels used in daily project business [46,49], and both industry and academia shift their focus on identifying the sources of project success, such as human traits and the knowledge, skills and abilities to be applied in the dynamic context of projects, for the project professional to lead their activities to anticipated results based on defined and accepted standards [41,48]. Entities such as the World Economic Forum (WEF), International Project Management Association (IPMA), Association for Project Management (APM), Project Management Institute (PMI) and Agile Business Consortium (ABC) invest in research to understand the competencies of professionals and present a set of crucial ones, but, in general, these kind of institutional frameworks cover functional and cognitive competencies to a larger extent than socially [48]. They aim to assist the establishment of development plans for project management, tailored education programs and training, and guidelines for project managers, while at the same time setting the standards for certification of project managers and suggesting the competencies with the highest probability to impact their performance [45]. Based on research over the past couple of decades, more than 170 project management competencies were categorized according to different criteria and project types, that is, the nature or attribute by which a project is differentiated, such as strategic importance, the area of application, and execution [50]. Existing literature is in alignment with the notion that behavioral and interpersonal skills (e.g., leadership, motivation, decision making, group dynamics) are more critical than technical and discipline-specific skills both within traditional and agile industries [40,41,43,45,46,47,50,51,52]. Such a trend may be in response to the fact that project management is an advancing profession in the context of rapid environmental changes and forceful stakeholder interactions, and as project complexity and/or novelty increases, so does the need for cross-functional project teams requiring a higher level of human skills [47,48,50]. However, authors in this cluster also notice that existing studies perceive project management competencies as rather static constructs and do not take into account their dynamic changes during advancements on the career path [40], while the rapid technological advancements and conducting the work within temporary project organizations, together with forecasts of future trends in the field, emphasize the relevance of development and continuous improvement of the knowledge, behaviors, skills, traits and abilities of individuals in project roles necessary for effective project management [6,45].

To professionalize the project management discipline, voluntary certification via professional associations and certification bodies appears to be a logical step forward as its main purpose is providing individuals with the right knowledge and skills to deliver projects successfully, create value and increase customer satisfaction [53,54,55,56]. The results of the research conducted by Rastovski et al. [6] among certified professionals further strengthen the opinion that if project management competencies receive formal recognition (such as certification), this can contribute to individuals’ professionalism, increase the chances of improved performance and sustainable project delivery and ensure the operations of the organization in alignment with the conditions on the market to achieve competitive advantage. Additionally, voluntary professional certification might present strong evidence of an applicant’s competencies and likely future performance, not only because it indicates proficiency in project management, but also because of the process behind obtaining it, such as joining professional project management association/s and increasing overall project management knowledge that might influence self-confidence and professionalism [44,50]. For that reason, certification systems together with educational and training institutions need to keep up with the newest trends coming from the market, as well as complex technological advancements and value systems of the organizations, with standards revised and updated accordingly [6,7,46]. Still, the impact of certification on project performance needs further examination as an insufficient number of scientific studies examined the realized benefits of certification in terms of improved performance of project managers, recognition of certification in the organizations, connection with career path and progress, and compliance of practices at the state level [6,53].

Social developments in recent years caused a sequence of transformations in various human aspects, as well as traditional project management functions [57,58]. According to the findings by Toljaga-Nikolić et al. [59], the application of project management methodologies is relevant to introduce sustainability dimensions in project management processes (in both private and public sectors) because when managed by a certain methodology, processes remain consistent with the social elements. The application of sustainable project management should contribute to operational and project excellence, business agility, value creation, and long-term presence in the market. de la Cruz López et al. [60] mention sustainability as the main aspect of project management and summarize proposals coming from a group of authors regarding the relevant components a project management methodology should have in order to properly manage sustainability in projects—including principles, processes and competences. According to Albarracín-Rodríguez et al. [57], for project managers making environmental impact, competencies of crucial importance include organizing people, influencing changes in their behavior and generating action guidelines that can be replicated by others. Project managers should be able to make the communities aware of environmental problems, establish themselves as examples to be followed and strengthen the development of continuous opportunities for meaningful and equal participation. However, regardless of the recognized need for incorporating elements of sustainability in project management, as well as developing understanding and competence in this area, research dealing with the topic is very limited and insufficiently specific.

Figure 4.

Network visualization of Rose cluster.

3.2.2. Olive (Integrating Knowledge Management Strategies for Project Success)

As the growth and survival of contemporary organizations in an increasingly turbulent, complex, and competitive environment characterized by uncertainty requires the inclusion of project management as a strategic approach in business to compress product lifecycles, promote creativity and innovation, improve the use of technological advancements, and strengthen the competition on the market, the number of individuals holding project management roles is also expected to experience rapid growth [61,62,63]. Research predicts an approximate increase of 23% in the terms of demand for project managers, positioning project management as the 26th fastest-growing profession among the 106 professions analyzed [64]. However, recent reports also show inequality between the increased need for project managers and the availability of qualified professionals that can ensure successful completion of projects and companies’ competitiveness [61]. Authors in this cluster agree on the multifaceted nature of project success and project critical success factors that evolved to encompass a range of criteria with no standardized or industry-accepted definition of project success or a unified list of critical success factors [65,66,67]. Traditionally, project success was viewed as a level to which project goals and expectations were met; however, in more recent research it became evident that the terms should be viewed from different perspectives and related to a variety of elements [65].

The success criteria can be categorized into two broad categories: success of the project (effectiveness, organizational impacts and perception of stakeholder satisfaction) and success of project management (efficiency, technical aspects related to the Iron Triangle) [62,68]. The three main dimensions of project success—time, cost, and quality—are still considered fundamental in measuring success, but contemporary perspectives are aligned in that the performance of a project goes beyond these, including but not limited to achieving strategic objectives and technical performance standards, customer satisfaction with project results, business success and stakeholder benefits [65]. Project failure is usually a result of human factors and their insufficient skills and knowledge in relevant areas or a lack of expertise in using modern tools. To achieve success, it is therefore necessary to not only enhance processes and products and focus on the individuals involved but also develop their project management competencies at various levels, including the individual, team, organizational and societal domains [40,66]. Individuals should have sufficient disciplinary technical (e.g., procedures, processes, techniques, tools and technologies for performing specific tasks in a particular industry), hard project management (e.g., management of time, cost and quality) and soft human, social and cognitive skills and attitudes (e.g., communication among various stakeholders, teamwork, leadership, conflict management, critical thinking, creativity, and personality characteristics that can contribute to the ability of an individual to manage projects and work effectively as a team member to build a cooperative effort within the project team) [40,65,68,69,70,71,72]. In project management, the demand for soft skills is emphasized more than in any other business context because of relationships that have to be developed more quickly and frequent interpersonal interactions across organizational and professional cultures in a project environment [61,62,67,73]. Still, in many cases, project management has been considered an accidental profession, meaning the role was being entrusted upon individuals who worked in a specialized role in another discipline (e.g., engineering and software development) and matured their competencies over time through experience working on projects and/or informal training [74]. To gain an adequate level of competence for project management roles and, consequently, to increase project success rates, individuals should have the opportunity to undergo appropriate education, while corporations are responsible for thorough investigation of expected project complexity to determine the necessary competencies, as well as to invest in knowledge management to direct and manage the company’s human capital and intangible assets [75]. Project management is a practice-based profession in which the application of project management principles in practice is more important than knowing the theoretical aspects [42], so innovative educational approaches with the focus on the right content (what should be taught) and pedagogy (how it should be taught) are required to develop the individuals in a proper way for the role and provide a career pathway of choice [31,74,76]. Project management education programs need to equip individuals with up-to-date knowledge and focus on developing reflective project practitioners who are pragmatic in the application of theory to practice, are creative, can think critically and conceptualize projects, experiment, adapt to changing context and make the right-decisions, solve problems and continuously learn from experiences to find solutions to challenging work problems [69,77,78,79]. However, the question is to what extent do the study programs meet the needs of the companies for quality individuals to manage projects [76,78]? Higher education is undergoing major changes moving from passive pedagogies (e.g., ex cathedra lectures), while extensive digitalization leads to changes in student relationships with teachers as they are not considered to be the only source of knowledge anymore [77]. Educational institutions should consider introduction of case studies, guest lecturing by industry practitioners, site visits, serious games (onsite and online formats), simulations, learning-by-doing, internships and gamification in project management education to help students become more comfortable with work situations and practices, capture their attention, provide them with a dynamic platform where they can apply theoretical concepts to practical situations and create safe and controlled, risk-free project environments that reproduce reality and facilitate knowledge and skill transfer and acquisition, content understanding, and motivation [61,64,69,76,77,79,80]. Previous research also shows that project management education and training programs still lack sufficient practical segment and fail to adequately prepare individuals for high-level projects or equip them to navigate the complexities of the contemporary work environment; in a multitude of cases, instead of creating reflective and creative practitioners, they produce technicians who can follow procedures but lack transferable competencies, as well as the ability to learn and adapt [62,64,81]. In addition, generation Z, with characteristics different from previous generations, needs new project management education approaches and methods [78,82,83,84]. Thus, it becomes an imperative to align the needs of project-oriented organizations with the right approaches to develop competent, work-ready project management professionals and invest efforts in their continuous professional development to decrease turnover and loss of organizational knowledge and ultimately ensure higher rates of project success within the company, develop national economic prosperity, and contribute to the wider global economy [65,70,77,85]. However, although previous research has recognized the need for competence development, with a special emphasis on behavioral competencies, insufficient research focuses on the importance that educational institutions have in this process; competence development for project management in the rapidly changing environment in which project managers find themselves today; matching the needs of the market and educational programs; educational methods for acquiring competencies that will ensure successful project management in the context of emerging technologies; artificial intelligence and the inclusion of sustainability; managing multiple projects simultaneously; the development of knowledge, skills, and abilities of different generations; and knowledge management and sharing.

Figure 5.

Network visualization of Olive cluster.

3.2.3. Green (Leadership and Emotional Intelligence as Pillars of Advanced Project Management)

Despite the widespread concept of project management in modern business, many companies are still at the relatively low level of project management maturity, which makes it hard for them to reach competitive advantage [86,87,88]. Furthermore, the volatile environment in which projects are executed requires individuals to excel in their roles and adequately face opportunities and challenges they are constantly exposed to (e.g., reductions in productivity, delays, disputes and interruptions of planned tasks), while managing various projects for their organization and dealing with stakeholders, with limited resources and complex regulatory requirements to drive project success [89,90,91]. Authors in this cluster agree that the focus should be on the development of soft skills, with two major behavioral factors in mind—leadership and emotional intelligence [47,91,92,93]. The concept of leadership has advanced from personal traits to a process-oriented approach and can be defined as a practice an individual uses to influence a group of people to achieve a collective goal [94]. Project leaders should therefore be able not only to use specific techniques, actions, behaviors and styles to establish and maintain vision and strategy, recognize core competencies, and ensure clarity of goals and procedures, but also to clearly communicate and develop team resilience and innovative approaches to influence, inspire, and motivate them to achieve project objectives, improve their performance and reach project success [89,90]. Findings of the previous research indicate that appropriate leadership might depend on various factors, such as the overall project, complexity and structure of the task, knowledge and maturity of team members, and gender stereotypes [95]. In addition, they point out the difference between leadership styles (more suitable for factors that are relationship-oriented) and leadership competencies (more suitable for factors that are task-oriented) [96]. Some of the most mentioned leadership styles include transformational (leader inspires and motivates team to achieve exceptional performance and outcomes), transactional (leader focuses on the exchange with the team and motivates them through rewards and punishments which are based on performance during the course of the project), servant-style (leader focuses on supporting and serving the team, prioritizes their needs and development and fosters a positive work environment), humble (leaders show respect for the team in a truthful manner, appreciate the capabilities of team members, and are open to new ideas and suggestions), and situational (leader aligns the leading style with the situation and team development/competence) [87,89,97,98]. The project manager should integrate the knowledge and skills of team members within a short timeframe to deliver expected project results [91]. The six main schools of leadership observe leadership as a combination of personal characteristics and areas of competency and include trait (successful leaders are born with common traits, e.g., physical appearance, capabilities and personalities), behavior (particular leadership aspects can be developed, e.g., styles that are adopted by leaders for the leadership task), contingency (matching personal characteristics of a leader to the leadership situation resulting in different leadership types), visionary and charismatic (transactional and transformational leadership styles focused on organizational change), emotional intelligence (distinction between personal and social competencies, focused on self-management and interaction management, from reading own emotions to those of the team, and acting wisely in relations with others), and competency (integrated aspects of previously mentioned leadership theories which are then grouped under intellectual (IQ), managerial (MQ) and emotional (EQ) competencies in a specific combination of knowledge, skills and personal characteristics) [99,100,101,102]. Projects that have high levels of complexity in the domain of interaction should have project managers with the highest levels of managerial and emotional competencies, because in this context they can develop to their full potential and influence project results to the largest extent through the leadership style they use [99].

Emotional maturity is recognized as one of the main leadership responsibilities. It can be defined as the ability of people to work together in a project [95]. Organizational, social and psychological researchers focused over the past few decades on the role of a leader which influences team dynamics and performance. They are related to managerial effectiveness, which should then enhance project performance as it enables coordination and cooperation between team members, develops empathy and trust, and facilitates knowledge sharing, problem solving and adequate stakeholder management, which consequently contribute to job satisfaction [91,103]. Leaders with high emotional intelligence scores are expected to have more proactive behavior in recognizing emotional reactions from employees and integrate emotional consideration in their leading behaviors, which will bring to more open communication and provide a significant and positive contribution to project team cohesion and effectiveness, enhance project performance, and lead to lower levels of stress and minimization of team turnover [91]. Three popular theories of emotional intelligence were developed by Mayer, Roberts and Barsade (including perception, assimilation, understanding and managing emotions), Goleman (including self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and social skills) and Baron (including interpersonal and intrapersonal skills, adaptability, stress management and general moods) [104]. In addition, previous research found seven emotional dimensions to leadership competence, namely self-awareness (ability to recognize and control own feelings), emotional resilience (ability to maintain consistent performance in a multitude of situations), intuitiveness (ability to make clear decisions by using both emotional and rational perceptions), interpersonal sensitivity (awareness of and taking into account the needs and perceptions of others), influence (ability to persuade others to consider a different perspective, while perceiving their position, listening to their needs and providing a rationale to change), motivation (energy and will to achieve results and to make an impact) and conscientiousness (commitment to a course of action) [91,104]. However, although previous research extensively researched the field of emotional intelligence, to date no unified explanation of emotional intelligence has been accepted, which makes it complex to define a relevant set of competencies, behaviors and traits [103]. In addition, the focus is mostly put on the role of project manager, while other relevant stakeholders in the management of projects and their position, motivation, or competence development in this area are still insufficiently researched.

Figure 6.

Network visualization of Green cluster.

3.2.4. Indigo (Innovative Approaches to Project Management in the Construction Sector)

The construction sector is a highly competitive project-oriented sector that is considered to be one of the most impactful in the world by bringing massive changes in infrastructure, sustaining development and promoting long-term economic growth and stability [105,106,107,108]. However, this sector is also criticized for its dynamic nature, insufficiency, lack of an industry-level strategic vision, creation of waste, supply chain fragmentation, high sensitivity to market conditions, low-entry barriers and competitive tendering mechanisms with small profit margins [109,110]. As innovation and technology transfer emerged as essential strategies and activities for dealing with consequences of economic fluctuations, and despite its stable and conventional structure, the construction sector was also impacted by them mostly due to governmental regulations, technical requirements, project-based performance and benchmarks [97,111,112]. Innovation and technology transfers in the construction sector are visible in terms of development of innovative materials, contracting, new construction technologies and ways of working to increase the flexibility of construction companies to respond in a better way to changes in the environment and to the needs of society [111].

The authors within this cluster are focused on different types of innovation as a competitive factor (e.g., information technologies, construction methods and equipment, end products), opportunities for innovation in different project phases (e.g., to influence project parameters such as cost and time), the impact stakeholders have on innovation, and the effect of the use of innovation on stakeholders and organization (vertical—information, products and services are shared among stakeholders during the project; horizontal—emerging from stakeholders utilizing information, product and services in a project) [106,111]. Additional research is directed towards continuous improvement of innovative capability, including lean (construction without losses), offsite (in which components such as steel and concrete framing, panel and box systems are produced in a factory and assembled into structures with minimal site work systems), and green and smart building construction (designed for optimum energy efficiency while giving the preference to natural, reclaimed or recycled materials, ensuring a healthier, more comfortable and productive indoor environment in which the usage of resources is maximized), which should involve fewer unskilled workers and increase system and process productivity, while shortening production time and decreasing costs, ensuring better quality, creating less waste and protecting the environment, and enabling better use of building materials, proving that if construction companies use certain internal capabilities, they can boost innovation and technology transfer to improve their performance [111,113,114]. Previous research agrees on the definition of organizational capabilities as a combination of competencies, activities and resources to achieve desired outcomes and includes (a) marketing capabilities determined by the level of sophistication, demand, and competence of the client, where cooperation and long-term partnerships, attention to user needs and deep understanding and continuous support to the clients can present important prerequisites for developing more unique products; (b) financial capabilities for managing sources of financing to increase reserves and allocate them adequately to sustain innovation; and (c) managerial capabilities including knowledge, skills, abilities, talents and willingness to lead, improve organization structure and implement innovative culture to support, encourage, evaluate and reward generation of new ideas, problem solving and proactive behaviors of team members [111,115]. Due to the project’s temporary nature, occurring changes require timely and informed decisions. Therefore, project managers also have to possess the necessary competencies and experience to understand the change and its type, implications on project, team morale and stakeholder relationships to analyze, manage and control it [116]. To make timely and well-informed decisions, project managers can seek support in progressive information and communication technologies that facilitate information collection and processing, as well as objectives, performance, resource and process management [58,117]. One of the most widely accepted digital technologies in the field of construction is Building Information Modeling (BIM), which streamlines construction efforts through collaborative planning and well-defined goals at the early stages of a project, providing an accurate representation of building parts in an integrated data environment [118]. It offers visualization, 3D modeling, optimization design, simulation of solutions, and sustainability analysis, facilitates the knowledge transfer between project teams, enhances the collaboration between stakeholders and efficiency in information sharing during the entire project lifecycle, and optimizes project outcomes [115]. Still, to gain the full advantage from BIM and such technologies in generating successful project outcomes, individuals included in projects need to demonstrate the set of relevant competencies related to technologies (inc. software, hardware and network), processes (inc. human resources, products and services, infrastructure and leadership) and policies (inc. contractual, regulatory and preparatory) [119]. Although the field of project management in the construction industry is very well covered by previous research, most of the research has focused on traditional project management, with little dedicated to new technologies and sustainability issues. There is also very limited research in other areas, focusing on contemporary management approaches, specific competence development needs in different sectors, and similarities and differences between them.

Figure 7.

Network visualization of Indigo cluster.

4. Conclusions

The conducted bibliometric and content analysis on 487 academic articles published in journals over the last 20 years resulted in a broad overview of research performed on the topic of project management competencies. The findings presented in four main clusters offer valuable insights into the existing body of research for both academia and practice. Additionally, given that professional bodies for project management actively shape the outlook of the profession by combining practice and current scientific and professional research in the field, the results could be interesting for them to identify key trends, validate emerging practices, and inform development of standards, certification systems and professional guidance. The increasing importance of competent individuals in project management, as well as their formal recognition and development in accordance with the needs of a changing environment, has been recognized as crucial for them to demonstrate professionalism, lead project teams, and ensure successful delivery of projects and value creation for stakeholders, which will in turn result in the adaptability of their organizations, changing market needs, and the achievement of competitive advantages and sustainability within the industries in which they operate. Although individuals are expected to have a satisfactory level of disciplinary technical and hard project management skills and attitudes, given the speed of development of relationships and the frequency of interpersonal interactions in the project environment, significant emphasis is placed on the development and continuous progress of behavioral competencies, especially leadership and emotional intelligence, regardless of the industry—traditional or agile. It is the responsibility of organizations to invest in knowledge management in order to adequately manage their human capital, and of educational systems to provide educational approaches that are focused on the right content and pedagogy for the transfer of knowledge and skills that will adequately prepare individuals for the challenges that the project work brings, ensure they successfully cope with opportunities and threats, and use innovative approaches to influence, inspire, and motivate teams to achieve project objectives, improve resilience, performance, and reach project success. Recently, in order to be able to make timely and well-informed decisions and deal with constant changes by understanding their type and implications for the project team and the project as a whole, information and communication technologies, as well as artificial intelligence, are coming to the fore as supports in data collection and processing, and project managers are more than ever expected to demonstrate a set of relevant competencies that will ensure they can apply relevant state-of-the-art technologies in their work. However, it needs to be taken into account that the present research had several limitations present in the selection of articles used in the bibliometric and content analysis (reliance on one database), data preparation (analysis of the keywords chosen by the authors of the articles and their low level of standardization which required unification in VOSviewer Thesaurus, which might have resulted in loss of insights into specific research topics or omittance of articles of great importance) and finally the high generality of the defined areas and conclusions due to the amount of the data in the analysis.

Based on the insights gathered and the recognized research limitations, future research should consider cross-referencing the findings from different available repositories not only to broaden the understanding of the current research trends in the field, but also to take into account areas that might not be recognized in this article, enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the findings. The research shows that future trends should bring more focus to areas such as (a) project management certification and its connection to project performance, successful project delivery, and benefits on individual and organizational levels, as well as broader national and international impacts; (b) specific skills which could further strengthen the position of the project manager as a leader in the organization, but also with additional relevance placed on other roles in management of projects, in order to create team cohesion and cooperation, increase motivation, and foster knowledge management to achieve of the best results at the level of individuals involved; (c) a variety of sectors and sector-specific capabilities (expansion from the construction area that has been present in the majority of existing literature), to gain more knowledge regarding the similarities and differences among them, as well as their specific needs and prerequisites for successful project management; (d) competencies necessary in multi-project contexts and for program and portfolio management; and, finally, (e) educational and training content and pedagogy to reduce the gap between organizational needs and available programs to equip project professionals with the relevant competencies, especially in the light of their dynamic nature, sustainability, emerging technologies, artificial intelligence, and the traits of the new generation of individuals entering the workforce.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13110972/s1: The sample for the bibliometric and content analysis was selected in accordance with the principles recommended for Systematic Literature Reviews—PRISMA [34].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.R. and R.D.V.; data selection and preparation: T.R., M.V. and R.D.V.; drafting the paper: T.R. and R.D.V.; review and editing: M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Berssaneti, F.T.; Carvalho, M.M. Identification of variables that impact project success in Brazilian companies. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Rodriguez, A. The Project Economy Has Arrived. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/11/the-project-economy-has-arrived (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Verenych, O.; Bushuyev, S. Interaction researching mental spaces of movable context, stakeholders, and project manager. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2018, 10, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, H.G. Decision-support modelling tool for contractor-to-project assignment and project management. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. 2025, 17, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvetti, D.; Ferreira, M.L.R. Innovative approaches to productivity monitoring: Integrating work sampling and electronic performance monitoring. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. 2025, 17, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastovski, T.; Vlahov Golomejic, R.D.; Vukomanovic, M. The role of competency-based certification in ensuring sustainable project delivery. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2023, 15, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahov Golomejić, R.D.; Rastovski, T.; Butković, D. Razvoj komunikacijskih i timskih elemenata kompetencija za upravljanje projektima u virtualnom okruženju. Sociol. Prost. Časopis Istraživanje Prost. Sociokulturnog Razvoj 2021, 59, 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Ekrot, B.; Kock, A.; Gemünden, H.G. Retaining project management competence—Antecedents and consequences. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredin, K.; Söderlund, J. Project managers and career models: An exploratory comparative study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Z. Human Factors in Project Management: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques for Inspiring Teamwork and Motivation; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gharouni Jafari, K.; Noorzai, E. Selecting the most appropriate project manager to improve the performance of the occupational groups in road construction projects in warm regions. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, S.; Vrijhoef, R.; Kessels, J. Tackling project management competence research. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Qiang, M. Understanding the changes in construction project managers’ competences through resume data mining. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2022, 28, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebler, M. Getting the Best Out of Your Competencies; Grantham Book Services: Brighton, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lucia, A.D.; Lepsinger, R. Art & Science of Competency Models; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zwell, M. Creating a Culture of Competence; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Struková, Z.; Bašková, R. Innovation of education for the development of key competencies of university graduates. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2017, 9, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsmore, P.; Cabanis-Brewin, J. AMA Handbook of Project Management; Amacom Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Competencies in the 21st century. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.M. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance; John Willey & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ashbaugh, J.L. The hard case for soft skills and retention. Healthc. Exec. 2003, 18, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Hadikusumo, B.H.; Ogunlana, S. Emotional intelligence and leadership styles in construction project management. J. Manag. Eng. 2007, 23, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L. Senior management perceptions of project management competence. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L. Global body of project management knowledge and standards. In The Wiley Guide to Project Organization & Project Management Competencies; John Willey & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 206–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lizunkov, V.G.; Minin, M.; Malushko, E.; Medvedev, V. Developing economic and managerial competencies of bachelors in mechanical engineering. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences, Research Paradigms Transformation in Social Sciences (RPTSS 2015), Les Ulis, France, 15–17 December 2016; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2016; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, K.; Ho, M.; Khan, S. Recruiting project managers: A comparative analysis of competencies and recruitment signals from job advertisements. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.C.; Lin, J.S.; Lee, H.C. Analysis on literature review of competency. Int. Rev. Bus. Econ. 2012, 2, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Belout, A.; Gauvreau, C. Factors influencing project success: The impact of human resource management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2004, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aime, F.; Meyer, C.J.; Humphrey, S.E. Legitimacy of team rewards: Analyzing legitimacy as a condition for the effectiveness of team incentive designs. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Individual Competence Baseline—Vol. 4.0; International Project Management Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nijhuis, S.A.; Endedijk, M.D.; Kessels, W.F.M.; Vrijhoef, R. Process competences to incorporate in higher education curricula. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2024, 5, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J.L. Constructing a Manuscript: Distinguishing Integrative Literature Reviews and Conceptual and Theory Articles. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2010, 9, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Murlow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Prisma 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Manual for VOSviewer 1.6.20; Universiteit Leiden and Centre for Science and Technology Studies: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, D.; Xie, Y.; Li, J. Mapping the research trends by co-word analysis based on keywords from funded project. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 91, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsnelson, A. Colour me better: Fixing figures for colour blindness. Nature 2021, 598, 224–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Fu, M.; Liu, R.; Xu, X.; Zhou, S.; Liu, B. How do project management competencies change within the project management career model in large Chinese construction companies? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.H.; Starkweather, J.A. PM critical competency index: IT execs prefer soft skills. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N.; Mitra, S. Recruiting a project manager: A hiring manager’s perspective. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. 2015, 6, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva de Araújo, C.C.; Pedron, C.D. IT project manager competencies and IT project success: A qualitative study. Organ. Proj. Manag. 2015, 2, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sołtysik, M.; Zakrzewska, M.; Sagan, A.; Jarosz, S. Assessment of project manager’s competence in the context of individual competence baseline. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingason, H.T.; Jónasson, H.I. Contemporary knowledge and skill requirements in project management. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, R.L.; Carneiro, T.C.J.; de Oliveira, M.P.V. Unveiling the core competencies of the successful project manager through the application of multiobjective. Rev. Gestão Tecnol. 2020, 20, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahov, R.D.; Klindžić, M.; Radujković, M. Information modeling of behavioral project management competencies. Inf. Technol. Learn. Tools 2019, 69, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipulu, M.; Neoh, J.G.; Ojiako, U.; Williams, T. A multidimensional analysis of project manager competences. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2013, 60, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, S.; Ribeiro, M. The new role of project management–how to gain competitive advantages with the appropriate project management assessment. Gr. Organ. 2009, 40, 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Rosamilha, N.; Silva, L.; Penha, R. Competence of project management professionals according to type of project: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2023, 11, 54–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J.; Hwang, B.G. Critical Project Management knowledge and skills for managing projects with smart technologies. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 05022013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzoka, F.M.; Keavey, K.; Miller, J.; Khemka, N.; Connolly, R. Critical IT project management competencies: Aligning instructional outcomes with industry expectations. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashah, A.D.; Thomas, J.; Blomquist, T. Exploring the value of project management certification in selection and recruiting. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N.; Marnewick, C. Investing in project management certification: Do organisations get their money’s worth? Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 19, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Bautista, R.; Diego-Mas, J.A.; Leon-Medina, D. Measuring the project management complexity: The case of information technology projects. Complexity 2018, 2018, 6058480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Riis, E. Value creation by building an intraorganizational common frame of reference concerning project management. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín-Rodríguez, A.V.; Amorocho, A.J.; Rincón-Guio, C. Environmental leader competencies for successful project management: A bibliometric and systematic review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2023, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Oladimeji, O.; Guedes, A.L.; Chinelli, C.K.; Haddad, A.N.; Soares, C.A. The Project Manager’s Core Competencies in Smart Building Project Management. Buildings 2023, 13, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toljaga-Nikolić, D.; Todorović, M.; Dobrota, M.; Obradović, T.; Obradović, V. Project management and sustainability: Playing trick or treat with the planet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz López, M.P.; Cartelle Barros, J.J.; del Caño Gochi, A.; Lara Coira, M. New approach for managing sustainability in projects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Scott-Young, C.; Holdsworth, S. Developing the resilient project professional: Examining the student experience. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros Sánchez, L.I.; Ortiz Marcos, I.; Rodríguez Rivero, R.; Juan Ruiz, J. Project management training: An integrative approach for strengthening the soft skills of engineering students. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 33, 1912–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Suikki, R.; Tromstedt, R.; Haapasalo, H. Project management competence development framework in turbulent business environment. Technovation 2006, 26, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, T.; Sezgili, K. Exploring the current practices and future directions in project management education and training. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241236053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.; Qureshi, B.; Shaukat, M. Project Manager’s Competencies as Catalysts for Project Success: The Mediating Role of Functional Manager Involvement and Stakeholder Engagement. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2024, 13, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, H.J.; Öörni, A. Successful projects or success in project management—Are projects dependent on a methodology? Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2023, 11, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudienė, N.; Banaitis, A.; Banaitienė, N. Evaluation of critical success factors for construction projects—An empirical study in Lithuania. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2013, 17, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, T.L.; Oliveira, B.S.; Carneiro, T.C.J.; de Moura, R.L.; dos Santos Lima, S. Project manager competencies associated with the projects’ success in the public sector. Rev. Gestão Proj. 2023, 14, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Hamid, A.; Alvi, A.; Omer, U. Blended learning models, curricula, and gamification in project management education. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 60341–60361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasy, T.; Anantatmula, V.S. From every direction—How personality traits and dimensions of project managers can conceptually affect project success. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, J.R.; Piki, A. Facilitating project management education through groups as systems. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.C.; Chen, H.H.G.; Jiang, J.J.; Klein, G. Task completion competency and project management performance: The influence of control and user contribution. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosková, M.; Jelínková, E. Identifying opportunities to innovate project management education in the digital age. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2023, 28, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, J.; Scott-Young, C.M. Priming the project talent pipeline: Examining work readiness in undergraduate project management degree programs. Proj. Manag. J. 2020, 51, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubuor, S.A.; Akwetey-Siaw, B.; Dartey-Baah, K. Examining the Relationship Between Project Complexity and Project Success: The Moderating Role of Project Management Competencies in Ghana’s Construction Sector. J. Afr. Bus. 2024, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Barnabe, F.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Improving project management skills by integrating a boardgame into educational paths. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, D.; Bonnier, K.E.; Hellström, M. How might serious games trigger a transformation in project management education? Lessons learned from 10 Years of experimentations. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2022, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukvić, I.B.; Buljubašić, I.; Ivić, M. Project management education in Croatia: A focus on the it sector needs. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2020, 25, 255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.K.; Israel, D.; Bhalla, B. Does previous work experience matter in students’ learning in higher project management education? Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 424–450. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, M.M.; Jaccard, D.; Bonnier, K.E. A systematic review on the use of serious games in project management education. Int. J. Serious Games 2023, 10, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefley, W.E.; Bottion, M. Skills of junior project management professionals and project success achieved by them. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2021, 9, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Silva, C.S.; Figueiredo, C.; Vitória, A.; Nogueira, T. Project management in engineering education: Providing generation Z with transferable skills. IEEE Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Aprendiz. 2021, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Marcos, A.; Alba-Elías, F.; Ordieres-Meré, J. An analytical method for measuring competence in project management. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 1324–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, S.; Nahod, M.M. Project manager’s role analysis as a project management concept. Teh. Vjesn. 2011, 18, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rwelamila, P.D.; Ssegawa, J.K. The African project failure syndrome: The conundrum of project management knowledge base—The case of SADC. J. Afr. Bus. 2014, 15, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Lee, S.M.; Clinciu, D.L. Competitive advantages of organizational project management maturity: A quantitative descriptive study in Australia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, M.Z.; Su, Q.; Abbas Naqvi, N.; Batool, R.; Aslam, M.U. Transformational leadership and project success: The moderating effect of top management support. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231195685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katunina, I.V. Organizational project management in Omsk region companies: Current state and development constraints. Экoнoмика Региoна 2018, 14, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, J.; Dolla, T. Investigating the leadership and visionary capabilities to make projects resilient: Processes, challenges, and recommendations. Proj. Manag. J. 2023, 54, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, M.; Khan, J.; Saeed, I.; Zada, S.; Jun, Z.Y. Linking public leadership with project management effectiveness: Mediating role of goal clarity and moderating role of top management support. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Barcaui, A.; Bahli, B.; Figueiredo, R. Do the project manager’s soft skills matter? Impacts of the project manager’s emotional intelligence, trustworthiness, and job satisfaction on project success. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, J.; Bond-Barnard, T.; Chugh, R. Soft skills and learning methods for 21st-century project management: A review. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2024, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbebe, S.; Jowah, L.E. Project leadership competencies influencing success in Information Communication Technology projects. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 26, 1846. [Google Scholar]

- Teichert, M.A.; Pospisil, R.; Brugger, D.P.; Lödige, M. Project Management of the Future: Working on Projects in the Current Field of Tension of Change. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2024, 13, 222–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.P.; Jerónimo, H.M.; Vieira, P.R. Leadership competencies revisited: A causal configuration analysis of success in the requirements phase of information systems projects. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; bin Mohamad, N.A. Differentiating between leadership competencies and styles: A critical review in project management perspective. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. 2016, 7, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rehan, A.; Thorpe, D.; Heravi, A. Leadership practices and communication framework for project success–The construction sector. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2024, 16, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Li, Z.; Durrani, D.K.; Shah, A.M.; Khuram, W. Goal clarity as a link between humble leadership and project success: The interactive effects of organizational culture. Balt. J. Manag. 2021, 16, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Geraldi, J.; Turner, J.R. Relationships between leadership and success in different types of project complexities. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2011, 59, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Turner, R. Leadership competency profiles of successful project managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Müller, R.; Dulewicz, V. Comparing the leadership styles of functional and project managers. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2009, 2, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, L.; Dulewicz, V. Do project managers’ leadership competencies contribute to project success? Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hao, S. Construction project manager’s emotional intelligence and team effectiveness: The mediating role of team cohesion and the moderating effect of time. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 845791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, W. Improving performance of construction projects: A project manager’s emotional intelligence approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2013, 20, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.K.; Jintian, Y.; Sukamani, D.; Kusi, M. Influence of Agile Leadership on Project Success; A Moderated Mediation Study on Construction Firms in Nepal. Eng. Lett. 2022, 30, 854–867. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, J.; Madrid-Guijarro, A.; Duréndez, A. Competitive capabilities for the innovation and performance of Spanish construction companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, M.S.; Mustafa, U. Management competencies, complexities and performance in engineering infrastructure projects of Pakistan. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 1321–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, Z.; Arditi, D.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Impact of corporate strengths/weaknesses on project management competencies. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozorhon, B.; Akgemik, O.F.; Caglayan, S. Influence of project manager’s competencies on project management success. Građevinar 2022, 74, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tezel, A.; Koskela, L.; Aziz, Z. Current condition and future directions for lean construction in highways projects: A small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdöğen, G.; IŞIK, Z. Effect of internal capabilities on success of construction company innovation and technology transfer. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2016, 23, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Isik, Z.; Arditi, D.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Impact of resources and strategies on construction company performance. J. Manag. Eng. 2010, 26, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laili, I.; Abdul-Aziz, A.; Suresh, S.; Renukappa, S.; Enshassi, A. A project management competency framework for industrialised building system (IBS) construction. Int. J. Technol. 2019, 10, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.G.; Ng, W.J. Project management knowledge and skills for green construction: Overcoming challenges. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S. Conceptualization and measurement of owner BIM capabilities: From a project owner organization perspective. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 3963–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonwinkel, S.; Fourie, C.J. A risk and cost management analysis for changes during the construction phase of a project. J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2016, 58, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mesároš, P.; Behúnová, A.; Mandičák, T.; Behún, M.; Krajníková, K. Impact of enterprise information systems on selected key performance indicators in construction project management: An empirical study. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.E.; Nahod, M.M. Stakeholder competency in evaluating the environmental impacts of infrastructure projects using BIM. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.A.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.; Owolabi, H.; Akanbi, L.; Gbadamosi, A. BIM competencies for delivering waste-efficient building projects in a circular economy. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).