Abstract

This study examines Brazil’s rural credit policy from four perspectives: productive sustainability, credit financing, regulatory impact, and strategic policies. It is an exploratory study based on qualitative analysis through in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 14 rural credit managers from a Brazilian financial institution. The findings suggest that environmental policy had a particularly significant impact on small- and medium-sized producers, with consequences for their income and regional development. The study also demonstrates that deforestation is not a widespread practice among Brazilian rural producers. This study contributes to the literature by helping to understand the restriction of rural credit in areas with deforestation occurrences. The limitations of the study include those of being conducted solely with managers from a single financial institution. This study can help the federal government identify areas for improvement and policy adjustments, as well as financial institutions and managers to proactively act within their competencies and strategic goals in the execution of regulatory measures.

1. Introduction

The global population has grown significantly since the mid-20th century. In 1960, the estimated world population was 2.5 billion people, reaching 8 billion by 2023. Projections indicate this figure will reach 9.7 billion by 2050 [1]. This demographic growth increases the demand for food and puts pressure on the agricultural sector to adopt new technologies that can expand the food supply.

In the context of climate change, it is crucial to implement sustainable production practices that aim to curb deforestation and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In the agricultural sector, sustainable development (SD) requires both increased productivity and the adoption of innovative technologies. This agri-productive model has shaped the commercial orientation of agri-exporting countries [2].

Productivity gains in agribusiness are crucial for the economic growth of developing countries, whose economies are often reliant on primary sectors such as agriculture, mining, and natural resource extraction. Promoting agribusiness can contribute not only to social equity but also to environmental preservation.

According to Vieira Filho and Silveira [3], productive investment seeks to increase yields while reducing production costs. Higher output per unit of land leads to lower deforestation rates and reduced GHG emissions. The FAO report [2] emphasises that inadequate land use for food production can exacerbate environmental problems such as biodiversity loss, increased deforestation, and soil and water contamination, incurring high social and environmental costs.

Thus, deforestation to open new lands for agricultural use has become a global concern. This is especially true in the case of Brazil, given that it is a major agricultural powerhouse [4] and has the largest tropical forest in the world, with unparalleled biodiversity [5]. It probably is “the most important country in terms of potential impacts of tropical deforestation and degradation on global climate” [6] (p. 1). This highlights the need to promote sustainability in the sector to guarantee production while preserving natural resources. However, it is worth noting that agricultural output in Brazil has expanded while maintaining two-thirds of the national territory covered by forests, with approximately 80% of the Amazon rainforest preserved. Brazil is therefore a prominent example of sustainable production, warranting more in-depth study.

According to Nabuurs [7], the global spread of more sustainable agricultural production depends on effective domestic policies and a favourable international environment. Transitioning to a sustainable agricultural model requires not only a combination of sound public policies but also access to technology, capacity-building for stakeholders, investment opportunities, and available funding to support this transformation.

The Paris Agreement emphasised the importance of climate financing [8]. Public policy effectiveness and implementation, however, are subject to criticism. A key approach involves internalising environmental externalities—imposing the environmental costs of production on those responsible [9].

Nonetheless, as Heyes [10] points out, such policies may have adverse effects, limiting markets and investment. Interventionism may hinder free market dynamics, create entry barriers for new agents, and lead to market concentration and rising prices. This can distort social welfare and exacerbate the problem. In this context, regulatory frameworks may constrain economic growth.

Agribusiness not only provides food but also drives broader economic development. The sector encompasses agricultural production as well as the entire supply chain, including inputs, industrial processing, services, and trade.

In 2023, Brazilian agribusiness accounted for approximately one-quarter of the national gross domestic product (GDP), one-third of employment (29 million workers), and half of the country’s exports [11]. On the global market, Brazil is a leading exporter of coffee beans, soybeans, sugar, ethanol, beef, chicken, cotton, and concentrated orange juice [12].

Brazil has continuously advanced its low-carbon agricultural policies. In 2010, the Low Carbon Agriculture Plan (ABC Plan) was launched to reduce GHG emissions, offering subsidised credit to support the recovery of degraded pastures, integrated crop-livestock-forest systems (ICLF), no-till farming, forest plantations, biological nitrogen fixation, and animal waste treatment [13]. In 2012, the Forest Code was enacted to protect forested areas by restricting land use, including private property, to ensure the sustainable economic use of natural resources and preserve biodiversity. In 2021, the ABC Plan was expanded to incorporate new technologies and renamed the ABC+ Plan.

In 2023, the ABC+ Plan was restructured and relaunched as Renovagro. Notably, access to rural credit—both subsidised and market-rate—was restricted for properties with indications of deforestation. To recognise and encourage sustainable projects, a 0.5 percentage point reduction in interest rates was introduced for financing verified sustainable initiatives, as assessed through the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR). This nationwide public electronic system centralises environmental information on rural properties.

The purpose of this study is to examine the extent to which this sustainability-related credit policy contributes to the sustainability of Brazilian agribusiness, based on the perceptions of those who implement such a policy on the ground—financial institutions’ rural credit managers. To our knowledge, this is the first study to conduct such an analysis. Another aim of this study is to examine how adequately the implementation of such a policy has been achieved. This will be performed based on the ideas put forward by Mazzucato [14] regarding public policy.

According to Mazzucato [14], governments play a crucial role in catalysing and coordinating public and private investment around common goals, which is essential for transitioning to a green economy. However, while environmental policies regulating agribusiness activities may promote a balance between economic development and environmental preservation, their effectiveness may also be compromised by governance failures. According to Mazzucato [14], symbiotic partnerships between the government and companies that genuinely serve the public interest are essential for generating public value. Based on this researcher’s ideas, we will discuss the implementation of the sustainability-related credit policy based on four pillars:

- Existence of combined efforts by the public and private sectors to transform technological, environmental, social and economic paradigms.

- Creation of an orientation towards the objective of sustainable agribusiness to coordinate public and private initiatives and build new networks.

- Creation of a mission-oriented framework with continuous and dynamic monitoring and evaluations throughout the innovation and investment process.

- Implementation of training actions to support entrepreneurs in adapting their projects and sustainability actions, with analysis of the influences on companies that have adopted sustainability practices.

Regarding sustainability in agribusiness, existing literature has focused mainly on isolated perspectives of consumers [15], farmers [16], and agricultural industries [17]. There is a lack of research examining the views of credit-granting organisations. This study examines these views, thus contributing to the literature and addressing this gap.

Khan et al. [18] classified the main constraints to the success of agricultural finance in developing countries into demand-side, supply side, and infrastructural constraints. The first type includes risk aversion, the small scale of the farms, farmers’ low repayment ability and lack of collateral. Supply side constraints include high costs of obtaining finance, stringent eligibility criteria, sluggish, time-consuming, and complicated application procedures, as well as a lack of competition in the banking sector. Among the infrastructure-related constraints mentioned by these researchers are the long distance to financing sources, a shortage of insurance facilities, and difficulties in accessing communication and technology-related infrastructure.

Brazil, through its productive technical efficiency and intense research, has implemented several sustainable production practices and techniques. However, the adoption and dissemination of these practices face challenges, such as the requirement for greater qualifications of producers, managers, technicians, and employees, in addition to the need for greater financial investments in the activity, as pointed out by Balbino et al. [19] and Gasparini et al. [20]. Using panel data analysis, based on a sample of 10,000 clients from all Brazilian states, Oliveira and Maranhão [21] found that access to rural credit for small producers is statistically significant in terms of family income for Brazilian producers.

This study aims to analyse the effects of Brazilian environmental policy on rural credit allocation from the perspective of financial institutions. Through a qualitative investigation based on interviews with credit-granting managers working in various regions of Brazil, the study aims to gain a deeper understanding of how this regulation influences credit practices in Brazil and assess the environmental effectiveness of the policy, as well as the strategies adopted for its practical implementation at the national level.

There is a lack of information in the literature and in the market itself on how institutions practice the financialization of agriculture [22]. This requires an understanding of intermediaries who facilitate investment by providing local information on governance, taxes, procedures, regulations and environmental and investment laws. Furthermore, they provide “structural coherence” when various problems and challenges arise [22,23,24]. Hence, the relevance of having access to the perceptions of those who are responsible for agricultural credit granting on the ground.

The remainder of the paper unfolds as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review and the theoretical framework employed in this study. The research design is described in Section 3. Thereafter, a section on the results and their discussion follows. Finally, in Section 4, some concluding remarks and reflections on the implications, limitations, and avenues for further research are offered.

2. Research Design

2.1. Analysis Method

This study is exploratory, based on qualitative analysis through in-depth, semi-structured interviews. According to Eisenhardt [25], the qualitative approach involving multiple case studies allows for the inclusion of representative perspectives and provides a comprehensive analysis of perceptions across different cases. The use of open-ended interviews is appropriate for answering the “how” and “why” questions typically posed in case studies [25,26,27].

Patton [27] identified seven types of contributions to knowledge generation associated with qualitative inquiry: (i) clarifying understanding; (ii) studying how processes unfold; (iii) capturing stories and understanding perspectives and lived experiences; (iv) elucidating how systems function and influence people’s lives; (v) understanding the context behind how and why events occur; (vi) anticipating consequences; and (vii) comparing cases to identify patterns and critical themes in each situation.

The qualitative investigation aligns well with the research’s objectives. It is employed to describe the reality of rural credit allocation under environmental regulation and to gain a deeper understanding of how this regulation influences credit practices in Brazil based on the interviewees’ perspectives.

Fourteen rural credit managers from Caixa Econômica Federal, a major public financial institution of Brazil, were interviewed. To select these interviewees, we first used a purposive sampling approach. All the managers from each of the five regions mentioned below were identified. Then, professionals with less than 2 years of experience in rural credit were excluded to avoid limited perceptions, simplistic heuristics, and inferences derived from isolated cases. The interviewees were selected through a random sampling method to ensure the impartiality and heterogeneity of the group, while also prioritising representation from the five regions of Brazil. The final two interviewees were also chosen at random, but within a specific region to provide a more balanced regional representation across Brazil.

To ensure the confidentiality of the data, banking secrecy, as well as the identity and regional location of the interviewees, were preserved. Caixa Econômica Federal—referred to hereafter as CAIXA—is a 100% publicly owned financial institution that has operated in the Brazilian market for 163 years. It is the primary executor of federal public policies in the financial sector and holds a consolidated position in the national financial system. The bank offers comprehensive financial services to its clients and maintains a widespread presence across all Brazilian municipalities through a diversified and decentralised service network.

CAIXA was selected as the financial institution for this study due to its early adoption of regulatory changes in rural credit practices. These changes were implemented during the second half of 2023—before the official enforcement date of 1 January 2024.

This research has been conducted solely by the authors, and no official authorities were involved.

2.2. Data Collection and Interview Protocol

A total of 14 rural credit managers (bank professionals) were interviewed and are hereafter referred to as E1 through E14. These managers are responsible for servicing a portfolio of clients with whom they maintain close relationships, following the “know your customer” approach. Their mission is to effectively utilise allocated resources while adhering to the legal framework governing credit operations and aligning with the strategic directives of the institution they represent. They provide direct service to clients in the field and are equipped to guide them through the complexities of financial operations and the specifics of each credit program.

Data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews using a deductive–inductive approach [28], following an interview guide (available upon request from the authors). To ensure the alignment of the questions with the study’s objectives, the questionnaire was pre-tested by a panel of rural credit specialists. This panel evaluated the clarity, internal consistency, and relevance of the questions to the target audience. Based on the experts’ feedback, improvements were incorporated, and the final version of the questionnaire was validated.

Both the preliminary meeting with the expert panel and the interviews were scheduled by the financial institution itself, with the support of the department responsible for managing the nationwide network of agribusiness-specialised banking units.

Due to the varying local and regional contexts and the potential differentiated impact of regulation, it was crucial to map the perspectives, opportunities, and challenges faced in each area. Each manager operates within a defined geographical radius, determined not by administrative boundaries but by the distance from their operational base to the client’s farm. This means there may be overlaps in the service areas between managers, particularly with long-standing clients who own large properties.

The interviews were scheduled by the institution and conducted via video call. They were recorded with prior authorisation from each participant, in compliance with the Portuguese and Brazilian General Data Protection Laws. Interviewees signed a digital informed consent form authorising the recording and use of their video, image, voice, and data for research purposes.

Before beginning each interview, participants were asked to authorise the recording and provided with a consent form, which they returned digitally signed. The interview guide was shared on screen and used to orient the participant in the initial approach to the topic, explain the methodology, present the research objectives, and define the analytical scope.

Each interview was structured around four main themes: the sustainability of Brazilian agriculture, the role of finance in driving sustainability, the impact of regulation on credit allocation, and strategies for implementing policy in practice.

Regarding agricultural sustainability, the goal was to assess each manager’s understanding of the concept and their perception of Brazilian agriculture. The interviews also sought to determine whether there was any negative sentiment toward agricultural production and to identify key associations with the sustainability agenda.

In the financial domain, the research examined funding for sustainable agricultural production. Interviewees were asked to reflect on how financial mechanisms can influence sustainability efforts in the sector. Perceptions of different stakeholders—clients, the financial institution, and the government—were compared. The role of managers in selecting sustainable proposals for credit allocation was also explored.

Regarding regulation, the impact of policy interventions in rural credit allocation was examined, as well as how these changes affected both the managers’ routines and their clients. The study investigated:

- -

- the impact of regulation on credit access for clients;

- -

- whether regular rural credit clients engaged in deforestation;

- -

- whether there were differences in credit allocation between sustainable and non-sustainable clients;

- -

- cases of unexpected credit restrictions due to deforestation flags;

- -

- challenges clients faced when incorporating sustainability into their projects;

- -

- whether clients recognised for sustainable practices benefited from the 0.5% interest rate reduction; and

- -

- whether this incentive motivated other clients to adopt sustainable practices.

Furthermore, the study examined the relationship between rural credit and economic growth, aiming to understand how rural credit contributes to local, regional, and national development. It also assessed which client profiles—small, medium, or large producers—depend most on rural credit.

Lastly, the study aimed to identify the most widely adopted sustainable practices, including integrated production systems, promotion of renewable energy, recovery of degraded areas, reduction in deforestation, compliance with environmental legislation, and the dissemination of environmental awareness.

In relation to implementation strategy, the adoption of sustainable agricultural policy was analysed through the lens proposed by Mazzucato [14] in her discussion of the implementation strategies for public policies for the transition to a green economy, which was presented in the previous section.

Having completed 12 interviews, a point of relative saturation was reached, indicating that no new information emerged with each additional interview [29]. Nevertheless, two further interviews were conducted to ensure better regional representation and to confirm data saturation, which was subsequently affirmed.

Upon completion, the interviews were transcribed and categorised by region. Memos, field notes, and conceptual mind maps were then developed to support the analysis of each thematic dimension.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

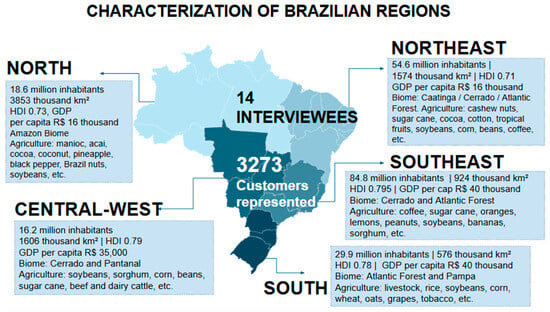

The interviews conducted with 14 rural credit managers enabled coverage of the 5 Brazilian regions (Figure 1). These managers deal with 3273 clients across the national territory. The interviews allowed for the inclusion of perspectives from all regions. This is an essential aspect since they were also asked about their clients’ practices. Notwithstanding, one must emphasise that the results presented and discussed in this section reflect the interviewees’ views and not the perspectives or experiences of these clients.

Figure 1.

Characterisation of Interviewees Across Brazilian Territory. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Among the interviewees, 64% were male, with an average of 8.4 years of professional experience in rural credit allocation. Their areas of operation covered all five regions of Brazil and five out of the six national biomes. The only biome not represented in the study was the Pantanal, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Each of the country’s regions was represented in the sample, with the following distribution: 14.3% of the managers operating in the South and Northeast regions, 21.4% in the North and Central-West regions, and 28.6% in the Southeast.

Following the characterisation, data analysis was conducted separately for each aspect under investigation. The consistency of the information provided—from the North to the South of the country—revealed a high degree of similarity in responses.

3.2. Main Findings

3.2.1. Sustainability of Brazilian Agribusiness

After characterising the interviewees, we sought to map their perception of the sustainability of Brazilian agriculture, the sentiments involved, and the motivations for their responses.

Feelings about a particular company, business, sector, or country have a significant impact on sales, investment decisions, and the financial market, and are widely studied in behavioural economics and economic psychology [30]. In a climate change scenario, the need to transition to a green economy and the perception of businesses with a lower environmental impact can attract or repel investment. It should be noted that, in this respect, Brazilian agriculture has been the target of criticism regarding its productive sustainability, often related to forest deforestation.

With this in mind, we sought to conduct an analysis of feelings and perceptions regarding the sustainability of Brazilian agribusiness from the perspective of rural credit concession managers. These managers are directly involved in agribusiness and provide direct services to producers and dealers in agricultural machinery, inputs, products, and services.

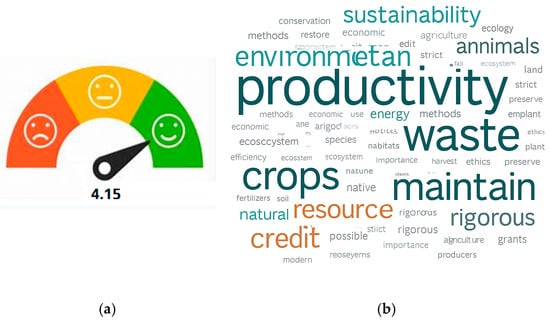

When asked about their critical perception of the phrase “Brazilian agriculture is sustainable”, graded from 1—“Strongly Disagree” to 5—“Strongly Agree”, the average response was 4.15 points. In general, it appears that financial agents who visit farms and serve clients, including farmers and agricultural dealers, have a positive perception of the sustainability level of Brazilian agriculture (see Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the perception of the sustainability of Brazilian agribusiness. Source: prepared by the authors. (a) Thermometer, (b) World Cloud.

Sentiment analysis on agribusiness sustainability was also cnducted. A word cloud was created to reflect the interviewees’ involvement in the topic and represent the intensity or frequency of the most frequently mentioned terms (Figure 2b).

The word cloud analysis suggests that, from the perspective of the interviewees, Brazilian agriculture is directly associated with the terms “productivity”, “natural resources”, “credit”, “preservation”, “environment”, “sustainability”, and other concepts that are directly and positively linked to sustainable development. In addition, there were several links between Brazilian agriculture and social, environmental and financial sustainability approaches, such as: “reducing pollution”, “maintaining the productive quality of the land”, “not silting up rivers”, “avoiding soil contamination”, “maintaining the planet’s living conditions”, “improving people’s quality of life”, “financially viable”, “natural fertilization”, “consortium farming”, “using renewable energy”, “technological advances”, “protecting forests” etc.

Of all the terms mentioned, increasing productivity to reduce environmental impacts was the one most often mentioned. Interviewee 1 (E1) stated that “you can’t have sustainability with hunger,” emphasising the importance of addressing a social need, which is a key component of the sustainability tripod. The strictness of Brazilian legislation was also mentioned by more than 50% of the interviewees, with E11 reporting that “there are so many things that Brazilian producers have to observe to produce, that it’s not possible not to be sustainable”.

Regarding the agricultural certification of farms, several interviewees reported dissatisfaction with the effectiveness and limitations of the CAR (Table 1), which could be an effective tool for assuming this role. According to E4, “farms need to be certified to defend local agricultural production abroad and block bad producers”. Of the 14 interviewees, 10 expressed a positive view on the need for an effective, nationally applicable certification for farms, including: “It would be great to give access to the differentiated rate”; “International certifications mainly reach large producers. Medium-sized producers generally don’t do it. And these certifications are not related to the granting of financial loans”; “It allows the product to be valued and production to be more profitable”; “It’s important to recognize producers who have already adopted sustainable practices, because what we have in Brazil is focused on investment (implementation), in other words, those who are already sustainable don’t have recognition or an incentive to continue adopting the practices, which sometimes result in higher costs”. The smallest percentage said they were neutral (22%) or negative to the proposal (7%), with concerns related to the increase in bureaucracy and cost, as shown in the table below.

Table 1.

Perception of the need for Brazilian certification for agricultural production. Source: own elaboration.

The widespread dissatisfaction with the CAR is related to what the interviewees perceive as a lack of analysis of the registry by the public entity responsible for it. They perceive this as preventing customers who have proven sustainable practices from benefiting from the 0.05% interest rate reduction.

The following areas for improvement in the process were identified:

- -

- Ensure predictable access to rural credit for producers;

- -

- Streamline credit approval by replacing environmental documentation requirements;

- -

- Enable interest rate reduction incentives;

- -

- Certify the sustainability and quality of agricultural production;

- -

- Advocate for agricultural production in international markets;

- -

- Promote the value of production and ensure its profitability;

- -

- Guide and encourage sustainable initiatives;

- -

- Restrict access for non-compliant or environmentally harmful producers.

3.2.2. Sustainable Financing in Agribusiness

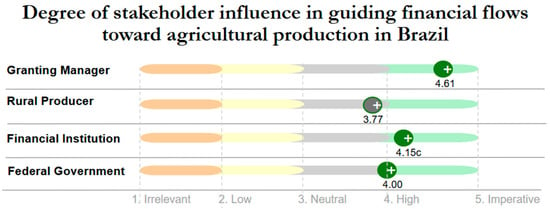

Regarding sustainable financing in agribusiness, the interviewees were asked about their perception of the role of finance as an inducer of sustainability in Brazilian agribusiness and the relevance of this issue to them, their clients, financial institutions, and the government. The general perception is that designing finance towards sustainable agricultural production is highly relevant, except in the case of rural producers (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Level of importance of the direction of finance for sustainable agricultural production in Brazil: producer, credit manager, financial institution and government. Source: own elaboration.

Following the mapping of perceptions regarding the relevance of directing resources toward the sustainability of the agricultural sector, efforts were made to investigate how such resource allocation is operationalised in credit-granting practices.

Given the absence of an official Brazilian certification system to attest whether agricultural properties adopt sustainable practices, an inquiry was conducted into the role of credit managers as agents in promoting sustainability through resource allocation. Several key responses were recorded, including: “This is already being done through the availability of investment resources for specific programs that foster agricultural sustainability. As managers, we ensure the most appropriate interest rate classification for each project, whether through Renovagro, Pronamp, Pronaf, etc.”; “Yes, through the Know Your Customer policy, we classify projects to access the best possible rates.”; “I ensure compliance with the legislation. Clients are selected during the pre-service phase.”; “Yes, but we are constrained by resource availability. Subsidised funds are primarily allocated for investment purposes. Those who invested in the past and now seek funding for sustainable operational expenses (working capital) have not received incentives or recognition in the form of reduced interest rates, as the CAR has not been analysed.”; “A broader effort is needed, encompassing certification systems, differentiated interest rates, capacity building, and support networks to ensure a more structured approach”; “The policy should promote, recognise, and incentivise sustainable practices rather than penalise them”; “Sustainability is already embedded in the client’s production processes, as their goal is to preserve the land to ensure greater yield returns”.

These excerpts reveal that the interviewees view public policies as channelling resources toward sustainable practices through designated credit lines. However, no innovative actions by credit managers were observed beyond appropriately matching client projects with the most suitable credit line, based on resource availability and the lowest applicable interest rates. In a context characterised by limited financial resources and a high demand for rural credit, the prioritisation of sustainable projects by credit managers is possible. Nevertheless, there is the perception of a tendency to allocate larger funding amounts to clients with higher-value projects, thereby optimising operational efficiency and accelerating goal attainment.

The interviewees also expressed apparent dissatisfaction with the lack of recognition or incentives for producers who have already implemented sustainable practices. The 0.5% rate reduction was not granted, and available sustainable financing lines were primarily directed toward new investments. Producers who had previously invested in sustainable initiatives were neither financially rewarded nor acknowledged through interest rate reductions.

Regarding financial aspects, all respondents (100%) expressed a positive view of the possibility of achieving economic growth in tandem with environmental preservation. Furthermore, they unanimously identified finance as a key driver directly associated with such growth.

3.2.3. Regulatory Influences on Rural Credit

The new regulations that changed how environmental concerns are considered in the granting of rural credit for the 2023/2024 crop year combined both command-and-control instruments and market-based mechanisms. The command-and-control approach was implemented through the prohibition of credit granting for agricultural operations in areas flagged for deforestation. As a market-based mechanism, a 0.5% reduction in rural credit interest rates was announced for producers holding a CAR with the status “analysed” and who adopt sustainable practices.

Concerning changes in rural credit-granting practices, all interviewees (100%) reported perceiving changes. However, two of them noted that while the intention to promote sustainability had advanced, the actual credit-granting process had not changed in practice. The remaining twelve participants presented narratives highlighting that the recent changes were more restrictive—limiting access to credit—than they were promotive of sustainability.

Interviewee E6 reported that the financial institution undertook internal organisational measures to comply with the new regulations, including an online alignment meeting with all credit managers. E9 stated unequivocally: “Clients with deforestation alerts are no longer served”. E11 described the observed changes and expressed frustration: “There is now a system validation for deforestation, and proposals are blocked because of it. Several system errors have been identified. The absence of CAR analysis was disappointing to clients. In my region, no client has a CAR in ‘analysed’ status, even though many practice sustainability. Similarly, E7 noted practical challenges and risks to producers: “There were many changes. Producers faced difficulties in adapting to the new resolution, which prevented some from accessing rural credit. Environmental compliance processes were required. We experienced delays in system updates. Some producers have the necessary licenses, but interdepartmental communication failures resulted in legal deforestation being flagged as illegal. This delays credit approval. If a client proves compliance, I can proceed with the proposal, but if the system takes too long to reflect this, the client may miss the planting window and be forced to seek financing from more expensive sources”.

According to E10, financial institutions have effectively taken on an environmental oversight role: “Environmental concern has increased. It’s evident—there’s a trickle-down effect: from government to banks, and from banks to producers, requiring compliance. It’s as though oversight mechanisms have expanded—now, beyond IBAMA, banks also play this role. The credit process remains the same, but producers are now required to make adjustments”.

Regarding deforestation alerts issued via the MAPBIOMAS satellite system, E4 pointed out that “the satellite does not differentiate between brush and forest; sometimes, lack of land clearing is flagged as deforestation. For example, if an area is not cleared for three years, trees can grow to 3–4 m in height. In this livestock context, tree growth in Brazil should not be interpreted as a shift in economic activity. Now, producers are required to obtain environmental permits even for pasture cleaning”.

E13 shared several illustrative cases: “I own three land registrations, each with different restrictions. Two are embargoed due to a lack of irrigation use permits. The agency responsible hasn’t analysed the submitted projects and maintains the embargo. Another case involves the creation of the Parque Nacional do Descobrimento, which took 3% of my property, previously used for cattle ranching. Twelve years later, the park still exists, but the formal expropriation process remains unfinished. Due to new legislation, I can no longer access credit for the remaining 97% of my property, which is still eligible for economic use, because the entire property is flagged due to 3% deforestation. I feel penalised three times: through land expropriation, lack of compensation, and now, loss of credit access—forcing me to seek costlier financing alternatives”.

Similarly, E14 noted that the CAR system now flags overlaps between productive and protected areas, such as Areas of Permanent Preservation (APPs), Legal Reserves (LRs), or deforested zones. This affects even compliant producers whose declared property boundaries overlap with those of noncompliant neighbours who are not themselves seeking credit, but whose environmental irregularities negatively impact others. E14 concluded: “Despite this regulatory progress, incentives for producers who engage in sustainable practices remain scarce. There is an observable effort to link sustainability with credit access, but currently, we, as a financial institution, have not yet succeeded in adequately rewarding sustainable clients”.

A combined analysis of the interviews reveals the perception of consistent challenges nationwide stemming from the implementation of new rural credit regulations for the 2023/2024 crop year, with the following issues emerging as particularly significant:

- (i)

- Increased concern and monitoring of deforestation indicators by both producers and credit managers;

- (ii)

- Credit restrictions due to overlapping areas in the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR);

- (iii)

- Inability to segregate the financed area, a practice that had been permitted until July 2023;

- (iv)

- Lack of CAR analysis by the government, which prevents the granting of the 0.5% interest rate reduction benefit on rural credit;

- (v)

- Delays in the environmental control system’s updates hinder credit approval for areas where environmental agencies authorised vegetation suppression;

- (vi)

- Deforestation alerts that surprised clients, including pasture clearing, vegetation suppression for renewable energy generation, and in areas expropriated or cleared for public utility works such as parks, roads, or squares;

- (vii)

- Increased bureaucracy and costs for producers to prove the legality of their actions.

Concerning clients who adopt sustainable practices, 100% of interviewees reported having such clients in their portfolios, engaged in various activities such as renewable energy generation, use of biodigesters in livestock farming, integrated forest-livestock systems, use of bioinputs, biological pesticides, biological fertilization, and the cultivation of sustainable forestry such as cocoa, açaí, eucalyptus, and intercropped farming of coconut and passion fruit. However, it was noted that only a few of these practices were eligible for subsidised credit rates. Among the 3273 clients included in the analysis, only one was granted the 0.5% interest rate reduction due to a CAR classified as “analysed”.

In addition to the issues related to deforestation alerts and lack of CAR analysis, other challenges were identified, including resource scarcity, the absence of a Regional Zoning by Productivity Level (ZarcPRO) for certain crops in specific regions, and difficulties faced by smallholders in presenting required documentation.

ZarcPRO is a technical zoning tool validated through research, which estimates the productivity potential of a given crop under specific weather and climate conditions. It is a requirement for credit approval for certain crops, production systems, and regions [31].

Another issue examined is that of the distribution of resources according to client classification (small, medium, or large producers) and the perceived importance of credit availability for each profile in promoting regional and national development.

Concerning the promotion of regional development, 64% of interviewees stated that it is essential for resources to reach all three client types (small, medium, and large producers, in that order). They consider that smallholders should be prioritised, as they need credit to produce and sustain their family income. Medium producers were also seen as crucial for supplying local and regional markets and for driving technology adoption, training, and job creation for other families. However, regarding national development, perceptions shifted. About 43% of interviewees believed that it is essential for resources to reach medium producers, 36% valued all three profiles equally, and 21% favoured large producers.

E10 argued that subsidised credit should be directed to small and medium producers, reasoning that large producers have their own capital and do not rely on government support. Interviewee E1 suggested that subsidised credit should benefit all three groups due to their distinct contributions to development: “Smallholders depend on Pronaf subsidised credit for family subsistence. Medium and large producers are less dependent, but they are the ones who generate jobs, promote technology transfer, and develop the entire supply chain, including industry, commercialisation, and training”. E9 agreed, stating that “Credit should reach all. Smallholders supply food to their families and communities (vegetables, dairy, meat, etc.). Medium producers add value and generate jobs, initiating agribusiness value chains with larger food distribution volumes. Large producers generate significant employment, tax revenue, and government income that support education, healthcare, and social services. Thus, all should be supported”.

There was no strong indication that subsidised credit should prioritise large producers, since these are typically large estates whose production costs far exceed the limited public credit lines. Such producers often reach their maximum individual credit limits through family members and also have access to working capital from private sources.

Regarding the availability of credit, E2 pointed out: “There is a shortage of funds for large producers because the resources run out quickly. There is also a lack of investment credit for small and medium producers. For operating costs, the available amounts have generally met the needs of small and medium producers”. However, E3 added that “only smallholders are left out due to complex documentation requirements”.

The interviewees seem to perceive a clear asymmetry in regulatory compliance capacity. While, according to them, medium producers typically possess the educational background necessary to understand and fulfil regulatory requirements, large producers benefit from dedicated administrative teams that manage documentation processes. In contrast, smallholders frequently lack both institutional support and awareness, often failing to recognise themselves as eligible beneficiaries of available credit programs. This is consistent with Khan et al.’s [18] remarks regarding the lack of appropriate financial literacy by most small-scale farmers in developing countries.

Regulatory asymmetries may be mitigated through the proportional application of norms relative to the scale of the producer, thereby promoting equity in both regulatory compliance and access to associated benefits.

E4 also emphasised the difficulties faced by smallholders, particularly regarding collateral. Small producers are not allowed to mortgage their family residence, which is considered protected property. Without collateral, they are often denied credit. Although credit guarantees were not a specific focus of this research, this point is retained as it reflects an element of credit policy that restricts access for smallholders and represents an area for potential improvement. This is in line with Khan et al. [18], who identified a lack of collateral as an important demand-side constraint to the success of agricultural finance.

Subsidised credit lines, for both medium and large producers, are generally capped at BRL 3 million per individual. However, there is a significant distinction between the maximum amount available and the effective availability of funds. As explained by E4, “larger volumes are made available to large producers, but these are quickly exhausted. While BRL 3 million represents a small portion of a large producer’s operational needs, for a medium producer, this amount is quite substantial. Furthermore, medium and small producers do not always seek financing from financial institutions to fund their production”.

Interviewees also advocated for a more regionally tailored allocation of credit resources as a way to reduce social and developmental inequalities across different regions. In this regard, E14 made a significant contribution, suggesting that “credit for smallholders requires closer monitoring and should be tied to the adoption of sustainable practices that make their work profitable. Small producers have less access to information and technical innovations—they still spray pesticides without PPE, without analysis, and harm aquifers, etc. It is not enough to offer credit and increase their workload without providing a profitable alternative that improves their quality of life and that of future generations”.

E9 reported that credit lines for large producers are depleted first, partly because financial institutions and credit managers prioritise higher-value contracts. The administrative effort required to approve BRL 3 million is the same as for BRL 150,000—the same checks, documentation, and requirements apply. Thus, focusing on higher credit values is more efficient, not only to meet institutional profit and operational targets, but also to accelerate the circulation of government-incentivised funds through the regional agribusiness supply chain. E9 further emphasised that increasing credit requirements is not the path to improvement. Instead, the credit process should be simplified for small and medium producers, ensuring equal access to funding opportunities.

Environmental regulation seem to have introduced several challenges in the pursuit of sustainable development in Brazilian agribusiness. An analysis of interviewees’ perceptions revealed that the smaller a producer’s Annual Gross Revenue, the greater the challenges faced in adopting sustainability. Smallholders encounter social, informational, legal, bureaucratic, and cost-related barriers. As E2 observed, “while smallholders need a great deal of support just to gather the documents required for credit, medium producers are hesitant to invest without a guarantee of benefits”. E6 pointed out that environmental oversight is a state-level responsibility, which results in inconsistencies in the timing and quality of environmental assessments.

Across the interviews, bureaucratic and economic difficulties emerged as the most frequent obstacles to the adoption of sustainable practices by Brazilian rural producers.

The environmental policy, by limiting credit access in cases of deforestation and by granting subsidised rates (interest reduction) to those who have already internalised the environmental costs of production, has exposed operational weaknesses—such as the federal government’s limited capacity to analyse the CAR and the lack of synchronisation among environmental protection systems. These gaps compromise the ability to quickly verify the legality of vegetation suppression, creating uncertainty among producers regarding their access to funding to maintain production. On the other hand, this policy represents both a national and international commitment by the Brazilian government to promoting agribusiness with environmental responsibility, engaging all actors in the effort to preserve natural resources.

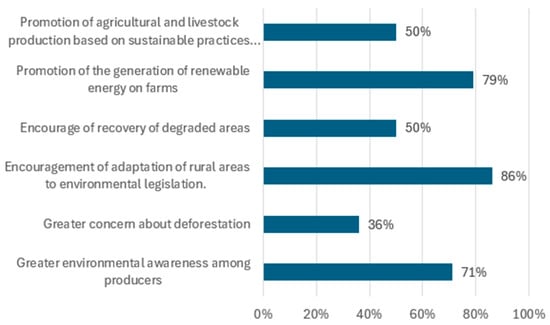

The environmental benefits derived from the regulation—serving as indicators of its effectiveness—were also examined. According to the interviewees, the most significant contributions of the regulation include the promotion of environmental compliance in rural areas, especially in terms of CAR registration with geospatial coordinates (86%), incentivising clean energy generation (79%), and increasing environmental awareness among producers (71%), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Perception of the contribution of environmental policy to Brazilian agribusiness. Source: Own elaboration.

Concerning these benefits, it is noteworthy that deforestation control received the lowest score among perceived contributions. Many respondents highlighted the strictness of the Forest Code and the difficulties associated with its enforcement. They pointed out that if environmental fines were effectively imposed on non-compliant producers, such regulation alone could already be sufficient to mitigate deforestation in productive areas.

E1 added that producers who rely on rural credit are already environmentally conscious, as they depend on nature for the success of their crops and therefore do not engage in deforestation on their properties. As such, degraded areas are scarce, since “a degraded area yields low financial returns, which is undesirable to producers. Many cattle ranching properties are now taking advantage of the RenovAgro incentive (for recovering degraded areas) to transition from livestock to agricultural production in these areas”.

Regarding the recovery of degraded areas, E14 reported that no such areas exist on the properties under their management, stating: “We were only able to implement one project of BRL 1 million (which is a low amount for agricultural production) for pasture recovery, and that was after two years of searching”. E2 added that the recovery of degraded land is usually initiated by the producers themselves, motivated by the need to prevent erosion and leaching, which negatively affect soil productivity. According to the interviewee, existing environmental legislation would already be sufficient to stop deforestation.

Reinforcing the argument concerning deforestation, E4 stated that “professional agriculture does not engage in deforestation; this has long been a concern”. Similarly, E8 declared: “I do not know any rural producer who deforests. IBAMA’s oversight is extensive. There is already environmental awareness. Those who do not have INCRA authorisation—those are the ones who deforest, cut down trees, and set fires”.

In terms of compliance with environmental regulations, there has been a clear incentive to register in the CAR system. Many producers appear to be motivated by the desire to secure the interest rate reductions outlined in the 2023/24 Agricultural Plan guidelines. E14 reported that the requirement for georeferencing of rural areas—a condition for CAR registration—served as a major driver of compliance with environmental legislation.

Despite these efforts, many criticisms emerged concerning the lack of positive incentives and tangible benefits of the environmental policy in promoting sustainability within the agricultural sector. Credit restrictions and the disproportionate efforts required to overcome administrative hurdles were seen as obstacles, particularly for small and medium producers. This seems to be in line with Khan et al.’s [18] analysis of the main constraints to agricultural finance success, which include stern eligibility criteria, and sluggish, time-consuming, complicated application procedures.

The lack of regulatory balance in terms of the consideration of the size of the producer or production scale made it more difficult for small and medium producers to access credit, at least according to the interviewees. They view the immediate application of the policy, without a transition period or trial phase, as having increased the risks associated with credit access, leading to uncertainty and insecurity among producers regarding their investments and long-term projects. These factors suggest the potential for increased operational costs, restricted entry for new market players, and even rising food prices, which could hinder economic growth in the sector.

One notable positive outcome of the policy seems to have been the joint mobilisation of actors across the agribusiness sector around the goal of sustainability. Currently, the requirement for documented evidence of forest preservation on agricultural properties, along with CAR registration and legal compliance, has gained strategic importance for protecting production activities against international trade barriers and has contributed to the sector’s credibility, both domestically and abroad. These mechanisms are likely to foster not only confidence in the sustainability of national agribusiness but also greater public and market acceptance.

As a result, the study found that although the environmental policy impacting rural credit in the 2023/24 agricultural season seems to have imposed strict and timely restrictions and increased operational costs, it does not appear to have prevented credit from reaching producers.

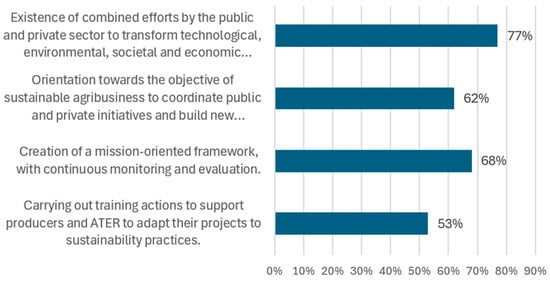

3.2.4. Policy Implementation

In this subsection, we aim to identify the implementation techniques employed in the strategic deployment of environmental policy for sustainable agribusiness and to highlight potential areas for improvement to achieve better outcomes.

Environmental preservation cannot be achieved through isolated efforts. Instead, it requires a collective movement involving all stakeholders. Companies that invest in ESG practices increase their market value, thereby creating a more favourable business environment. For the transition to a green economy, this model of sustainable capitalism must extend to inter-institutional and cross-sectoral relationships [14].

Numerous implementation strategies and theories exist, many of which share significant similarities. This study focused on the four stages of implementation as outlined in the theoretical framework proposed by Mazzucato [14], with the results presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Perception of the implementation of the four steps of an environmental policy in light of the stakeholder capitalism theory. Source: Own elaboration.

The interviewees are part of a Brazilian public financial institution, which is the largest executor of public policies in the Brazilian government. These professionals have responsibilities that go far beyond financial transactions; they play a role in coordinating with regional public authorities, private institutions, trade unions, and the business community. These agents are aware of the financial and political value of each stakeholder, including workers, citizens, trade unions, community groups, state institutions, private institutions, and NGOs, for the success of implementing an environmental public policy with both individual and national reach, in urban and rural areas.

Regarding capacity-building actions, E7 acknowledged their existence but mentioned that they were not structured in a way that would provide visibility and attract the interest of the local community. However, E7 stated that “financial institutions have carried out capacity-building directly with clients to maintain the pace of credit disbursement.” E14 reported the organisation of “field days” and “agribusiness fairs” as educational actions in the program. Such events, promoted by state institutions and local governments, bring stakeholders together and facilitate the alignment of knowledge, promoting the pursuit of a common objective.

Regarding the creation of a mission-oriented framework, E1 reported the existence of several control and monitoring panels, both for the agribusiness manager and the regional representative. E12 added that financial institutions have their national controls, and the Central Bank of Brazil provides a national dashboard that consolidates resources and the allocation of funds by program, subprogram, region, state, gender, etc.

In relation to an orientation toward sustainable agribusiness goals, E2 stated that “there is much orientation but little practice”. The guidance for sustainable agribusiness objectives is evident in the dissemination of the Plano Safra. It gathered public, private, and state institutions, as well as associations, with online broadcasting and availability for re-viewing at any time.

Regarding combined efforts from the public and private sectors, E2 reported difficulties. E7 revealed a similar perception: “I observe initiatives, but both public and private institutions need to try harder. The lack of analysis of the CAR by the public entity, which left thousands of producers disappointed, is one example”. E10 pointed out that private institutions have more concerns, take more actions, and implement sustainable initiatives more promptly than public ones. E11 observed that efforts are more individual than combined. E14 shared that in their region, there is a strong integration between agribusiness actors and synchronisation of combined efforts.

Another suggestion for improving the implementation of environmental policy could be derived from analysing the 2023 Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform in Europe, which recognises agriculture as a contributor to environmental and climate goals, provides targeted support to smaller farms, and offers flexibility for Member States to adapt measures to local realities. The issue of smaller farms is a significant concern in developing countries. As argued by Khan et al. [18] (p. 18), in these countries, the majority of the small-scale farmers lack the appropriate financial literacy. Hence, targeted support would be an essential issue to incorporate into the policy. Given the heterogeneity of Brazilian regions, the flexibility to adapt policies to local realities would be an interesting feature to consider.

Findings reveal that, in general, the implementation of environmental policy is perceived as being aligned with the strategy of stakeholder economic theory; however, there is still much room for improvement, both in individual and combined efforts from stakeholders.

4. Conclusions

This study examines the effects of Brazilian environmental policy on agricultural financing from the perspective of credit-granting managers. There is an overall perception of a high level of sustainability in Brazilian agricultural production, as evidenced by various indices and metrics, as well as the strictness of environmental legislation in protecting forests and native areas in Brazil. However, the manner in which the credit policy was implemented raised several concerns and areas for improvement, as detailed below.

The research focused on four aspects: agricultural production sustainability, sustainable financing, direct influences of regulation, and implementation of the policy. Regarding agricultural production sustainability, the general perception is that sustainability efforts in Brazilian agriculture are relatively well established. Regarding sustainable financing, the interviewees consider it possible to reconcile economic growth with environmental preservation and identify rural credit finance as a key driver for sustainable development. Notwithstanding, they also noted difficulties in directing resources toward sustainable production and determining the values invested in these areas. With reference to the influences of regulation on credit, according to the interviewees, the definition of a subsidy through an interest rate reduction for production with sustainable practices motivated numerous producers to complete the rural environmental registry for their properties. However, the interviewees also noted that the government’s response, with its inertia and operational incapacity to analyse the registered CARs, revealed a lack of public sector engagement with sustainability in practice. The interviewees’ perspectives are that producers who anticipated and invested in implementing sustainability practices did not receive the expected 0.05% interest rate reduction, nor did they receive recognition, appreciation, or financial compensation for their efforts. Finally, based on the perceptions of the interviewees, the policy has been reasonably well implemented. Based on their perceptions, joint efforts from the public, private, and other stakeholders in favour of the sustainable development of agribusiness exist. However, there are various areas for improvement in the process. There is a need to align communication among stakeholders, clarify and define sustainability actions, and provide transparency and consistency in stakeholder communication to mobilise and raise awareness in each group regarding the importance of their actions and the co-benefits for the project’s success.

This study contributes to the literature by providing an analysis of the public policy implemented in Brazil during the 2023/2024 crop year through the eyes of credit-granting agents. The federal government can use it to identify areas for improvement and policy adjustments. It can also be used by financial institutions and managers to proactively act within their competencies and strategic objectives when executing regulatory measures. It can be utilised to reduce asymmetries in the application of regulation, supporting Brazilian producers and fostering new strategies for policy implementation to promote local, regional, and national development while preserving natural resources. For example, we believe the policy could be adjusted to provide targeted support to small-scale farmers and to provide some regional flexibility. The role of an intermediary actor in policy implementation could be explicitly acknowledged. For example, in the case of agricultural credit policies in developing countries, the knowledge of actors such as credit-granting managers should be mobilised to address issues such as the lack of financial literacy among small-scale farmers.

From a theoretical perspective, we consider that this study may offer some insights into Mazzucato’s [14] approach to policy design and implementation, specifically by drawing attention to the importance of the actors who, in many cases, ultimately implement the policy on the ground. These professionals have responsibilities that go far beyond financial transactions; they play a role in coordinating with regional public authorities, private institutions, trade unions, and the business community. These agents are aware of the financial and political value of each stakeholder for the success of implementing an environmental public policy with both individual and national reach, in urban and rural areas.

One of the limitations of the study is that the findings cannot be generalised. We interviewed a small set of professionals, which precludes such generalisation. Additionally, due to banking secrecy and to preserve the professional integrity of the interviewees, ensuring their confidence in expressing their experiences openly and freely, the information was not segregated regionally. A cross-analysis of information could identify both the professionals and the clients from the regions studied. Another limitation was that the research was conducted solely with managers from a single financial institution, Caixa Econômica Federal. This limitation reflects a narrow reality based on the company’s strategy. A suggestion for future research would be to expand the investigation to include other managers (bankers) from financial institutions operating in rural credit.

This research did not address the impacts of regulation on rural insurance, which is an interesting topic for further research, as it is an essential issue for maintaining producer income, ensuring security for the production sector, and sustaining productive investment in the face of potential risks from crop failures due to climate change. Future research could also explore the perceptions of other stakeholders, such as farmers themselves and the ultimate consumers of agricultural products, regarding the adequacy of policy implementation. With a view to providing more robust findings, additional research based on surveys by questionnaires should be conducted. This would enable surveying a large sample of professionals. Additional research could also be undertaken to explore the impact of sustainability-related credit-granting policies on bankruptcy in the agricultural sector and the importance of models for predicting bankruptcy in relation to sustainability [32]. Another issue that warrants further research is the role of digital innovation in implementing this type of policy and its potential to foster the required collaboration between different stakeholders [33].

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.A., J.E.R.V.F. and M.C.B.; methodology, A.A.; investigation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, J.E.R.V.F. and M.C.B.; supervision, J.E.R.V.F. and M.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be shared due to ethical and legal restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Arone Alves is consultant at Caixa Econômica Federal, in the Vice Presidency of Sustainability and Citizenship. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Caixa Econômica Federal or its members. This paper is the result of research conducted at the School of Economics and Management of the University of Porto.

References

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. How Has World Population Growth Changed over Time? Our World In Data. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth-over-time?trk=public_post_comment-text (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2022. Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Economies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Filho, J.E.R.; da Silveira, J.M.F.J. Technological change in agriculture: A critical review of the literature and the role of learning economies. J. Rural. Econ. Sociol. 2012, 50, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D. ‘Export or die’: The rise of Brazil as an agribusiness powerhouse. In Rural Transformations and Agro-Food Systems; Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 653–672. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, R.C.; Arnell, A.; Simonson, W.; Soterroni, A.C.; Mosnier, A.; Ramos, F.; de Carvalho, A.X.Y.; Camara, G.; Pirker, J.; Obersteiner, M.; et al. Implementing Brazil’s Forest Code: A vital contribution to securing forests and conserving biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2021, 30, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, B.F.; Yanai, A.M.; de Alencastro Graça, P.M.L.; Escada, M.I.S.; de Almeida, C.M.; Fearnside, P.M. Amazon deforestation: A dangerous future indicated by patterns and trajectories in a hotspot of forest destruction in Brazil. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabuurs, G.-J.; Mrabet, R.; Abu Hatab, A.; Bustamante, M.; Clark, H.; Havlík, P.; House, J.; Mbow, C.; Ninan, K.N.; Popp, A.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU). In Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Climate Change 2022; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Acordo de Paris Convenção-Quadro das Nações Unidas sobre Alterações Climáticas (UNFCCC), Paris, França, 2015. 12 dez 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Chaves, C.; Pinto, L.C.; Valente, M. Economia Ambiental; Conceitos e Desenvolvimentos: Almedina, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Heyes, A. Is environmental regulation bad for competition? A survey. J. Regul. Econ. 2009, 36, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPEA/USP. GDP of Brazilian Agribusiness. Brazil: Center for Statistics and Applied Research. 2023. Available online: https://www.cepea.esalq.usp.br/br/pib-do-agronegocio-brasileiro.aspx (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Vieira Filho, J.E.R.; Gasques, J.G. Brazilian Agriculture: Evolution, Resilience and Opportunities; Institute of Research in Applied Economics: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023; Volume 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishlow, A.; Vieira Filho, J.E.R. Agriculture and Industry in Brazil: Innovation and Competitiveness; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. Collective value creation: A new approach to stakeholder value. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2022, 38, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salnikova, E.; Grunert, K.G. The role of consumption orientation in consumer food preferences in emerging markets. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.D.; Huu, L.H.; Hoang, L.P.; Pham, T.D.; Nguyen, A.H. Sustainability of rice-based livelihoods in the upper floodplains of Vietnamese Mekong Delta: Prospects and challenges. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin-Chaudhry, A.; Young, S.; Afshari, L. Sustainability motivations and challenges in the Australian agribusiness. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Nouman, M.; Negrut, L.; Abban, J.; Cismas, L.M.; Siddiqi, M.F. Constraints to agricultural finance in underdeveloped and developing countries: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2024, 22, 2329388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbino, L.C.; Cordeiro, L.A.M.; Martínez, G.B. Contribuições dos Sistemas de Integração Lavoura-Pecuária-Floresta (iLPF) para uma Agricultura de Baixa Emissão de Carbono. 2011. Available online: http://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/handle/doc/921371 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Gasparini, L.V.L.; Costa, T.S.; Hungaro, O.A.D.L.; Sznitowski, A.M.; Vieira Filho, J.E.R. Sistemas Integrados de Produção Agropecuária e Inovação em Gestão: Estudos de Casos no Mato Grosso [Texto para Discussão]; Instituto de Pesquisa em Economia Aplicada: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; Volume 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.H.C.d.; Maranhão, A.N. A Importância do Crédito Rural Familiar na Renda e no Consumo Durante a Pandemia COVID-19—Uma análise Contrafactural com Microdados 5° Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Economia; Administração e Sociologia Rural do Nordeste (SOBER-NE): Serra Talhada, Brasil, 2023; Available online: https://www.even3.com.br/anais/15-sober-nordeste-375197/727933-a-importancia-do-credito-rural-familiar-na-renda-e-no-consumo-durante-pandemia-covid19---uma-analise-contrafactua (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Ouma, S. Opening the black boxes of finance-gone-farming: A global analysis of assetization. In The Financialization of Agri-Food Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ouma, S. This can (’t) be an asset class: The world of money management, “society”, and the contested morality of farmland investments. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 52, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarim, E. Storytelling and structural incoherence in financial markets. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 2012, 24, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DePoy, E.; Gitlin, L.N. Introduction to Research E-book: Understanding and Applying Multiple Strategies; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, M.; Parker, N. ‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2012, 13, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devitt, A.; Ahmad, K. Sentiment polarity identification in financial news: A cohesion-based approach. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics, Prague, Czech Republic, 23–30 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MCR. Rural Credit Manual (MCR). Brazil. 2024. Available online: https://www3.bcb.gov.br/mcr/completo (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Srebro, B.; Mavrenski, B.; Bogojević Arsić, V.; Knežević, S.; Milašinović, M.; Travica, J. Bankruptcy risk prediction in ensuring the sustainable operation of agriculture companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, M. Catalyst for Sustainable Development and Digital Transformation: The Round Table on Green Economy. 2025. Available online: https://casopisrevizor.rs/index.php/revizor/article/view/226/213 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).