Abstract

This research analyzes the relationships among environmental factors, organizational structure, strategic orientation, and organizational performance within the Romanian medical system, addressing a theoretical gap in this context. A quantitative approach was applied, analyzing data from 502 employees in the Romanian medical sector. The study used a dual framework, integrating gestalt theory and mediation to examine the environment–structure–strategy–performance relationship. Two-stage cluster analysis, one-way analysis of variance, and partial least squares structural equation modeling tested direct and mediated effects among the variables. From a gestalt perspective, five distinct clusters demonstrated the interplay between environment, structure, and strategy. Romanian healthcare organizations align their structural elements and strategic decisions coherently and distinctly, considering contextual constraints, with implications for several performance dimensions, including patient satisfaction, financial stability, innovation, and internal process improvement. From a mediation perspective, both direct and mediated relationships indicate that organizational structure and strategic orientation positively affect organizational performance and suppress the negative contextual effects. This study contributes theoretically by extending contingency and gestalt theories to the Romanian healthcare context, showing that contextual fit, rather than structural uniformity, determines performance variation. Practically, the findings guide healthcare managers and policymakers in attenuating contextual shocks and improving organizational performance through strategic alignment and flexible structural design.

1. Introduction

Healthcare is a vital sector focused on individuals’ well-being and quality of life. This importance has led to intense competition among healthcare organizations, both nationally and globally, to deliver high-quality services efficiently, even during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2].

Recent literature highlights the increasing importance of systematic strategic planning. Meyers and Kottapalli [3] state that controlled strategic forecasting improves hospitals’ capacity to adapt to uncertainty and enhances organizational performance. Additionally, Ng and Luk [4] and Li et al. [5] stress the need to analyze environmental factors in healthcare systems, noting the government’s influence on health services and patient perceptions. Related research [6] shows that executive-level structures significantly affect hospital performance, supporting the strategic importance of organizational design. Singh and Charan [7] argue that healthcare organizations require an efficient structure to strengthen internal relationships and processes, enabling employees to meet patient expectations. Alsharari [8] adds that organizational structures must evolve continuously to achieve performance targets, often influenced by strategic orientation. Similarly, Steinmann [9] shows that redesigning hospital structures based on value-based principles improves coordination and overall performance, emphasizing the interdependence between structure and strategy. Engelseth et al. [10] highlight that a well-integrated approach, driven by health service performance, demonstrates the interdependence among stakeholders, including clients, providers, and the state. Therefore, any disruption to this system can hinder its ability to meet patient needs effectively.

A review of the literature [1,5,7,8,10] indicates that research has mainly addressed processes, with limited attention to the relationships among organizational structure, performance, and strategic orientation in the external environment context. Although existing studies analyze individual elements, such as strategic orientation or performance measurement, they frequently neglect how organizational structure aligns with strategy to influence performance in dynamic healthcare settings. Recent studies [3,11] highlight this limitation and call for integrative analyses linking strategic orientation, organizational configuration, and performance outcomes. This issue is especially relevant in Romania, where healthcare institutions experience inefficiencies and inconsistent strategic implementation [12]. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies [13] reports that the sector remains underdeveloped and performs below the European Union average in scientific research and healthcare unit performance. National studies [14,15,16] mainly address patient satisfaction and treatment but often do not examine how government policies, changing patient behaviors, and organizational alignment affect healthcare service delivery and strategy formulation. A database search using key terms such as “Romanian healthcare,” “organizational performance,” “environment,” “strategic orientation,” and “organizational structure” found no relevant results, indicating a gap in the specialized literature. This suggests that research on Romanian healthcare organizations’ performance, strategic orientation, and structural alignment is in its early stages and requires further study.

Given these gaps, this study investigates the Romanian healthcare system, offering empirical insights to inform decision-makers and improve government support. The following research question arises from this context.

- RQ1.

- What are the circumstances surrounding the structure–strategy relationship and its consequences?

- RQ2.

- What are the implications of this alignment for organizational performance in Romanian healthcare?

Given the evolving dynamics of Romanian organizations, these studies clarify previously unaddressed elements in Romanian literature, reinforcing the motivation for this research. The findings offer deeper insight into the mechanisms linking strategy, structure, environment, and organizational performance. This knowledge can improve the effectiveness of managerial decisions at various stages of Romania’s strategic management process.

Researchers have examined these relationships using primary data that accurately reflects social realities, applying various conceptual frameworks and statistical and econometric methods. This process generally involves two main steps: identifying relevant methodological analysis frameworks in the literature and selecting and applying the most appropriate frameworks based on the research objectives and previous findings.

This study adopts a methodology based on established paradigms. First, analytical techniques and methodological frameworks are identified and reviewed. Next, the most suitable statistical and econometric methods are selected to test the research hypotheses and achieve the study’s objectives.

2. Theoretical Background

The contingency theory, introduced by Burns and Stalker [17], evaluates organizational structures based on the premise that alignment between an organization and its environment results in superior performance. This concept, referred to as “organizational fit,” describes the degree of alignment between internal and external environments. Further, Scott [18] (p. 89) states that contingency theory assesses “the best way to organize, which depends on the nature of the environment in which the organization operates.” Subsequent developments [19] emphasized that effective organizations must maintain congruence between structural configurations and environmental contingencies to sustain performance. Various authors [20,21,22,23] examined how technology affects efficiency and how external environments influence differentiation and integration within organizations. Recent research confirms that no single structure ensures perfect adaptation; instead, organizations must continuously realign internal processes and strategic choices to match contextual conditions [24,25].

In addition, various researchers [26,27,28] have examined contingency theory across different organizational contexts, emphasizing internal factors rather than environmental influences as primary drivers of performance. Research [29] has largely neglected contingency theory in service industries, focusing instead on production, despite the stronger interaction between internal and external environments in service delivery.

From a healthcare services perspective, gaps remain in understanding the relationship between organizational fit and external environmental demands. In recent decades, healthcare services have changed significantly, making the sector a key component of the global economy. This change has resulted from rising patient expectations and increased competition among healthcare organizations [1]. As a result, external pressures have required healthcare organizations to adjust their structures and strategic visions. Islam [30] identifies these external influences as primary drivers prompting organizations to respond quickly to patient needs. However, internal readiness is equally important in determining how organizations adapt to environmental challenges [31]. Pfaff and Klein [32] argue that, although external pressures are critical for organizational change, internal factors also drive adaptation rather than simply prompting reactions to external demands. Organizations that adjust to changes in the external environment—including legislative, cultural, and social shifts, as well as gradual learning processes [33]—achieve greater performance. Continuous adaptation is therefore essential for meeting stakeholder needs in evolving environments [34,35].

Van Offenbeek, Sorge, and Knip [36] found that contingency theory indicates organizations should restructure when increased environmental complexity and interdependent tasks require greater flexibility. Specifically, organizations should integrate work functions, decentralize authority to improve local decision-making, and reduce bureaucratic constraints [37]. However, increased demands for cost reduction and accountability may lead organizations to adopt more mechanistic structures. In these situations, organizations encounter “competing contingencies,” which negatively affect organizational design [38]. Recent findings from the community hospital setting [24] confirm this paradox, showing that balancing structural flexibility with control mechanisms helps maintain alignment under changing policy and resource conditions. Strategic choices should align with structural adjustments resulting from environmental pressures. Without a clear strategic vision, structural changes can be inconsistent, leading to suboptimal outcomes [39]. To improve strategic adaptability, organizations require effective decision-making processes and support mechanisms that enhance their ability to identify opportunities [40]. The ability to reconfigure structures quickly in response to uncertainty demonstrates a dynamic capability that increases organizational resilience and performance [41].

While scholars debate the extent of competition among public health organizations, recent analyses show that this competition involves not only the allocation of government funding but also the mobilization of technological, human, and informational resources within complex health markets [42,43].

Research [44,45] has examined factors affecting health organizations’ performance, identifying variables in this process, such as technological, human, and financial resources, market conditions, strategic orientation, and the structure of the national health system. Organizations seeking optimal performance and competitive advantage use well-planned, deliberate, yet adaptive strategies that reflect institutional and technological developments in the health sector [46,47].

The literature identifies two main perspectives on the structure–strategy relationship: “structure follows strategy” [48] and “strategy is determined by structure.” Recent management research supports a dialectical perspective, recognizing that strategy and structure co-evolve through reciprocal influence, constraints, and feedback mechanisms [34,49,50,51]. This theoretical convergence provides a basis for examining how alignment or deliberate misalignment between structure and strategy affects organizational performance in public health systems [52]. Based on these insights, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1.

Congruence (internal consistency) exists among the forces operating in the health services market, organizational design, and strategic choices of health organizations.

Hypothesis 2.

Congruence (internal consistency) has implications for performance.

The alignment between the environment and organizational structure, as well as their alignment with strategy, serves as a mediating mechanism that influences the relationship between an antecedent (environment, structure, or strategy) and the resulting variable (performance) [53]. Specifically, how healthcare organizations interpret external environmental forces—such as competitive threats, substitute availability, market uncertainty, and supplier bargaining power—determines both the configuration of structures (integration, centralization, formalization, and complexity) and the shaping of strategic orientations (differentiation versus cost efficiency). These dimensions collectively affect organizational performance across outcomes such as patient satisfaction, financial stability, innovation capacity, and internal process improvement [51,53].

Effective organizational design shapes interactions between external and internal elements. Contingency theory states that complex, dynamic environments require flexible, decentralized structures, whereas stable environments favor formalized, standardized configurations [54]. Therefore, strategy serves as an adaptive mechanism that aligns organizational resources and internal capacities with external pressures and opportunities [55].

To achieve superior outcomes, Mitchell and Shortell [56] argue that organizations must adapt structures and strategies in response to internal and external pressures. Masood et al. [57] highlights that both tangible and intangible resources are essential for delivering unique or differentiated services. However, Harsch and Festing [58] emphasize that resource management depends on an organization’s strategic orientation and design. Strategic choices significantly affect operational processes, partnerships, service delivery, and other healthcare aspects [56].

Additionally, organizational performance should be examined through the interactions among structure, strategy, and environment, rather than in isolation. Recent research [59,60] indicates that organizations aligning their design with strategic orientation are better able to navigate external challenges. This alignment enhances operational efficiency, innovation, and adaptability, supporting sustainable competitive advantage and improving patient satisfaction.

To examine the relationships among environment, structure, strategy, and performance in healthcare organizations from a mediation perspective, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

The perceived influence of forces in the healthcare market, together with organizational design and strategic orientation, affects healthcare organizations’ performance.

Hypothesis 4.

Strategic orientation and organizational design mediate the effect of perceived forces in the healthcare market on performance.

Building on this framework, this study further examines the relationships among environment, organizational structure, strategic orientation, and performance to clarify their effects on medical unit performance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Framework

The environment–structure–strategy–performance relationship has been examined using various theoretical frameworks. Researchers have employed different analytical approaches and statistical methods to provide empirical support for these theories.

Furthermore, Venkatraman [53] classified various interpretations of “fit,” connecting theoretical concepts to statistical methods according to the specificity of relationships among concepts and whether an evaluation criterion is present. This classification resulted in six approaches: moderation, mediation, matching/pairing, gestalt, deviation from the ideal profile, and covariates. Additionally, Bergeron and Raymond [61] introduced a third criterion, noting that analytical frameworks may include multiple variables.

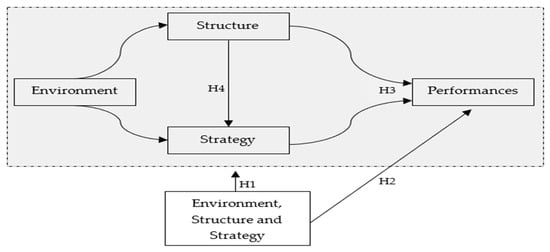

This study analyzes the environment–structure–strategy–performance relationship using gestalt theory and mediation. This combined approach addresses the complexity of these relationships and allows performance evaluation based on their effects. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model that guides this investigation and proposed hypotheses:

Figure 1.

The conceptual model. Source: The author’s conception.

3.2. Research Scales

A questionnaire was developed [62] based on the conceptual model, incorporating four scales—environment, structure, strategy, and performance (see Table A1). Owing to the complexity of these concepts, subscales were included to enable multidimensional analysis and account for potential interconnections. Most items were adapted from existing scales and tailored to the healthcare sector. Management and health professionals validated the scales, and exploratory factor analysis refined the final items and scale structure.

- (1)

- Environment (ME): This scale assesses key characteristics of the medical field. Based on Porter [63], it includes forces shaping this sector, such as the threat of substitute services, new competitors, supplier bargaining power, competition intensity, and market uncertainty [64,65,66].

- (2)

- Structure (SO): This scale evaluates organizational structure characteristics, including external integration [67], complexity [68,69,70], formalization, and centralization [71].

- (3)

- Strategy (OS): This scale categorizes strategic orientation according to Porter’s [64] generic strategies of cost leadership and differentiation [62,72,73].

- (4)

- Performance (PERF_BSC): This scale measures performance using a multidimensional approach, applying the balanced scorecard (BSC) framework [74] adapted to healthcare. Dimensions include patient satisfaction, internal processes, innovation, learning for continuous improvement, and financial performance [75,76,77,78].

- (5)

- Demographic questions: This section gathers respondents’ and organizational characteristics.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

A self-administered, structured online questionnaire (Table A1) was used for data collection. The survey used snowball sampling to efficiently reach healthcare personnel in multiple regions. Participants were informed of the purpose of the research and the anonymity of their responses, and they provided consent to participate. Appropriate review board ethical approval was obtained. During a two-month period, 520 responses were collected from healthcare professionals working in hospitals, pharmacies, medical centers, and private practices across Romania. The questionnaire captured respondents’ perceptions of their organizations, not institutional data, and included a control item to identify whether participants were employed in a single healthcare organization or multiple institutions. After data screening, 18 responses that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 502 participants from Romania. At completion, 46.81% of respondents worked in large medical facilities (hospitals), with a mean age of 20.13 years. Participants represented various professions, primarily doctors (38.05%), followed by pharmacists, nurses, pharmacy assistants, nursing staff, and non-medical personnel. Most participants held executive roles. Survey data were entered into databases compatible with SPSS Statistics (versions 26.0 and 27.0) [79,80] and SmartPLS 3.3.3 [81] for analysis. Data processing included two-stage cluster analysis and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the environment–structure–strategy–performance relationship from a gestalt theory perspective (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was also applied to assess mediation (Hypotheses 3 and 4). PLS-SEM was selected because it accommodates complex structural relationships, including mediation between first- and second-order latent constructs, and provides a comprehensive representation of research concepts [82].

4. Results

4.1. Environment-Structure–-Strategy–Performance Relationship According to the “Gestalt Theory” Perspective

4.1.1. Methodological Considerations

The analysis investigated linear bilateral relationships among various dimensions [61] and evaluated internal coherence between selected attributes using gestalt theory [53]. These attributes facilitated the identification of homogeneous profiles within clusters. Miller [83] observed that, for a given set of attributes, only a limited number of profiles exhibit significant differences in variable scores and their relationships. Venkatraman [53] identified two main challenges in applying gestalt theory to matching: descriptive validity, which requires that selected clustering attributes are theoretically interpretable, and predictive validity, which concerns how attribute matches affect performance. To examine relationships among environment, structure, and strategy in healthcare organizations, as well as their performance implications from a gestalt perspective, we conducted three successive stages:

- Selection of attributes: Identified attributes and variables form the basis for cluster formation.

- Cluster analysis: Observations were grouped into homogeneous clusters to maximize distinctiveness, thereby validating Hypothesis 1. The log-likelihood distance method, which assumes variable independence and normal distribution, was used. A two-step cluster analysis was selected because it automatically determines the number of clusters, manages large data sets, and accommodates both continuous variables (standardized automatically) and categorical variables [84].

- Analysis of implications: Evaluated the fit between attributes (gestalts) using one-way ANOVA to determine significant differences in mean evaluation scores across clusters, validating Hypothesis 2.

4.1.2. Implications of the Environment, Structure, and Strategy Fit for the Performance of Health Organizations

1. Selection of attributes

This model examines the relationships among environment, structure, strategy, organizational design, and strategic choices, assessing their effects on healthcare organizations’ performance. Clusters are formed using the average scores of these variables, revealing performance patterns. The analysis evaluates how congruence among variables influences healthcare performance by comparing average scores across BSC dimensions [74]: patient perspectives, economic and financial performance, innovation and continuous development, and internal process performance. Clusters are described by facility type, size, and age, although these attributes are not used as grouping variables.

2. Cluster analysis

A two-step algorithm classified 502 observations into five clusters using 11 continuous variables representing perceptions of the external environment, strategic choices, and organizational design. The solution demonstrated satisfactory intercluster separation and intracluster cohesion, as indicated by an average global silhouette index (S_k = 0.3) and a critical ratio of 1.49. Alternative solutions were also examined. Table A2 presents cluster profiles, and Table A3 reports attribute averages relevant to defining gestalts and the effects on internal coherence.

Cluster 1 (186 observations, 37.05%) consists mainly of individual medical practices and pharmacies. These organizations have fewer employees and lower seniority and are less likely to be affiliated with a firm cluster. They perceive moderate threats from substitutes, competitors, and competition intensity but are less affected by supplier bargaining power or market uncertainty. Their strategic structure is slightly complex, centralized, and formalized, with minimal emphasis on cost reduction or differentiation. Their range of strategic activities is narrow.

Cluster 2 (189 observations, 37.6%) consists mainly of medical centers and hospitals with larger workforces and cluster affiliations. Organizations in this cluster perceive moderate threats from substitutes, competitors, suppliers, and market uncertainty. Their organizational structure demonstrates medium levels of integration, centralization, complexity, and formalization. They prioritize competitive advantages through service diversification and cost leadership across a moderate range of activities.

Cluster 3 consists mainly of hospitals, which accounts for the higher average number of employees and older organizational age compared to Clusters 1 and 2. This cluster includes 127 observations (25.299%). Organizations in Cluster 3 are most affected by the external environment and have strategic priorities similar to those in Cluster 2. They aim to achieve a competitive advantage by diversifying medical services and pursuing cost leadership within a moderate range of strategic activities.

The previous analysis indicates that organizations in the three clusters have developed their structural elements and strategic decisions coherently and distinctly, considering contextual constraints. Each cluster makes managerial decisions and seeks optimal levels of the attributes defining the three gestalts [85].

To test Hypothesis 1, an ANOVA compared the means of 11 grouping variables across clusters. Table A3 shows statistically significant differences, demonstrating that the clusters are distinct in the analyzed attributes and supporting Hypothesis 1.

3. Implications for performance

For Hypothesis 2, an ANOVA compared the mean scores of four performance dimensions across clusters. Table A3 presents statistically significant differences, supporting Hypothesis 2. These findings indicate that congruence (internal consistency) between market forces, organizational structure, and strategic choices affects healthcare organizations’ performance.

Analysis of the three clusters using the multidimensional BSC perspective shows the following (see Table A3):

- Patient performance: Cluster 1 demonstrated low performance, while Clusters 2 and 3 were average to high; the Games–Hovell post hoc test indicated significant differences among all clusters.

- Economic and financial performance: Performance was average across clusters, but the Games–Hovell test found significant differences only between Cluster 1 and the combined Clusters 2 and 3.

- Continuous innovation and development: Cluster 1 performed low, while Clusters 2 and 3 were average, with no significant difference between them. Clusters 2 and 3 emphasized training, research, and professional development, supporting participation in seminars and conferences. Despite environmental differences, organizations with similar strategic choices had comparable innovation scores.

- Internal processes performance: Cluster 1 performed low, while Clusters 2 and 3 were average. The Games–Hovell test showed significant differences among all clusters, with Cluster 1 lowest and Cluster 2 highest. Internal process efficiency was evident in the presence of top specialists, advanced medical equipment, and high-performance IT systems.

4.2. Relationships Among Environment–Structure–Strategy–Performance from a Mediation Perspective

4.2.1. PLS-SEM Specification and Evaluation

The study examines four second-order reflexive–reflexive constructs—ME, SO, OS, and PERF_BSC—using the repeated indicator method [86,87]. Each second-order construct comprises several first-order constructs.

Table A1 presents the validity and reliability of the measurement model. The reliability of relationships between first-order constructs and indicators, as well as between second- and first-order constructs, was assessed using loadings. All indicator loadings exceeded the 0.7 threshold [88]. Coefficients between first- and second-order constructs ranged from 0.5 to 0.7 and were retained because of their theoretical significance [88,89]. Cronbach’s alpha (α) ranged from 0.712 to 0.956, and composite reliability (ρ_C) ranged from 0.839 to 0.962, both exceeding the 0.7 threshold [88]. Most average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.5, except for the second-order SO and ME constructs, which were below the recommended threshold. AVE assesses convergent validity [90] and is more conservative than composite reliability. However, ME (ρ_C = 0.86) and SO (ρ_C = 0.90) showed adequate convergent validity based on composite reliability [90,91]. Therefore, ME and SO were retained as hierarchical constructs because of their importance. For the other constructs, AVE values ranged from 0.515 to 0.798, surpassing the thresholds established by Hair et al. [88] and Sarstedt et al. [92]. Discriminant validity was evaluated using the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio [93]. As indicated in Table A4, all HTMT values were below 0.85, confirming the distinctiveness of the measurement model.

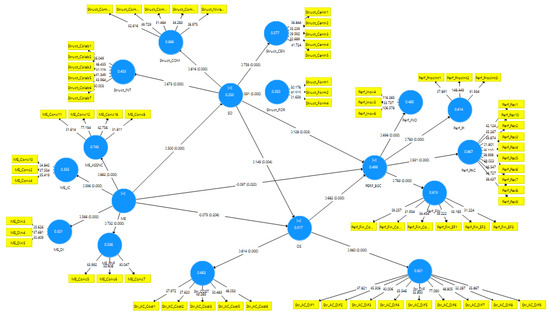

The structural model (Figure 2) presents R2 and path coefficients for direct effects. The statistical significance of indirect effects is assessed using bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples.

Figure 2.

Structural model. Source: Authors’ analysis with SmartPls 3.3.3 [81].

Following [94], the R2 coefficients show that SO had weak explanatory power (R2 = 0.250), while performance-related constructs demonstrated medium explanatory power (R2 = 0.499). OS exhibited very weak explanatory power (R2 = 0.017). These results indicate that much of the variability in performance is due to factors outside the model, suggesting that additional, unexamined determinants may affect health organization performance.

4.2.2. Analysis of Performance Determinants

To test Hypotheses 3 and 4, we examined the direct and indirect effects of environment, organizational structure, and strategic choices on performance. We used bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples to assess statistical significance and bias-corrected confidence intervals. Table 1 summarizes the findings.

Table 1.

Determinants of the performance of health organizations.

The direct positive effects of SO→PERF_BSC and OS→PERF_BSC were statistically significant (β = 0.128; p < 0.01; β = 0.682; p < 0.001). These results provide partial support for Hypothesis 3, indicating that the organizational design and strategic orientation of healthcare organizations affect their performance. In contrast, the direct effect of ME on PERF_BSC was negative, small in magnitude, and statistically significant (β = −0.097; p < 0.05).

Regarding the mediating effects, empirical results partially support Hypothesis 4 because the total indirect effect of ME on PERF_BSC, mediated by OS and SO, is not statistically significant. However, SO and OS have a suppressive effect, reducing the negative direct effect of ME on performance, which leads to an overall nonsignificant total effect. Additionally, the paths ME→SO→PERF_BSC and ME→SO→OS→PERF_BSC demonstrate positive specific indirect effects (β = 0.064, 95% BCI [0.024, 0.108]; β = 0.682, 95% BCI [0.015, 0.089]).

5. Discussion

Gestalt theory proposes that health organizations should develop adaptive models integrating organizational design and strategic vision. However, these models affect performance, especially when they do not address the complex relationships among environmental attributes, structure, and strategy.

Recognizing that the identified configurations affect performance differently, three main patterns can be distinguished. First, organizations facing moderate market pressures (Cluster 2) reported the most favorable outcomes in patient satisfaction, financial performance, and internal processes. Their structures showed balanced integration, centralization, complexity, and formalization, and their competitive advantage relied on combining service diversification with cost efficiency. Second, organizations experiencing strong external pressures (Cluster 3), such as competition from substitutes, new market entrants, and supplier influence, achieve the highest levels of innovation and continuous development. These organizations exhibit high integration, complexity, and centralization; moderate formalization; and strategic orientations comparable to those in Cluster 2. In contrast, organizations in medium to moderately dynamic market environments (Cluster 1) report the lowest performance across all dimensions. Their structures are relatively centralized and formalized, with limited complexity and minimal focus on cost optimization or differentiation in their strategic actions.

Pertusa-Ortega et al. [95] examined organizational structure, environment, and knowledge performance, reporting findings consistent with this study. They found that formalized structures clarify tasks, activities, and relationships, thereby increasing efficiency. Additionally, Nielsen [96] reported that organizational complexity and low centralization improve performance by encouraging interaction, communication, and knowledge absorption. Low centralization distributes responsibilities, which promotes autonomy and innovation. Recent studies continue to emphasize the importance of structural balance. Altamimi et al. [97] found that maintaining equilibrium between centralization and decentralization improves adaptability and performance in dynamic market conditions. Krenyacz and Revesz [98] reported that excessive centralization in healthcare systems reduces managerial autonomy and decision-making flexibility, limiting organizational responsiveness. Similarly, Shishkin et al. [99] demonstrated that moderate centralization, combined with structural coordination mechanisms, enhances alignment between strategy and organizational design, supporting more efficient governance models. These findings align with evidence from Bernstein, Shore, and Jang [100] in general management and Kim [101] in supply chains, both indicating that optimal balance, rather than extremes, supports better performance.

From the mediation perspective, results are analyzed for each performance driver, as follows:

The organizational structure (SO) has a direct positive effect on healthcare performance, as well as a positive, statistically significant indirect effect. Strategic orientation (OS) mediates the relationship between organizational structure and healthcare performance. Hyde and Shortell [102] argued that the relationship between structure and performance depends on management style, resource configuration, and decision-making quality, a point reinforced by Gora [103], who emphasized the influence of managerial motivation and resource distribution on healthcare outcomes. Berberoglu [104] showed that standardized internal procedures can improve operational efficiency; however, excessive rigidity may restrict innovation and timely decision-making. Rohman et al. [105] found that structured organizational systems with quality assurance mechanisms contribute to higher healthcare performance, especially in child protection centers. Rafi’i et al. [106] further reported that healthcare organizations with cohesive cultures and structured coordination achieve greater provider satisfaction and service effectiveness. Similarly, Wongsin et al. [51] showed that aligning strategic planning with organizational structure consistently predicts improved institutional performance in public healthcare systems.

External Environment (ME): As previously discussed, the extent to which healthcare organizations perceive external environmental influences directly affects their performance. Beyond these direct effects, complex indirect effects involving SO and OS serve as suppressive forces, reducing ME’s negative effect on performance. Academic literature consistently emphasizes that healthcare performance depends on how organizations interpret and adapt to external market conditions, such as policy pressures, workforce mobility, and competitive intensity. Recent evidence by Beauvais [43] shows that higher market dynamism and structural responsiveness in hospital environments significantly affect staffing patterns and operational performance, demonstrating how external forces lead to internal structural adaptation. Walshe [107] also noted that adherence to standardized indicators, such as quality metrics, internal procedures, and employee specialization, is essential for maintaining consistent performance across medical systems. Our findings are consistent with those of Bloom et al. [108], who found that in highly competitive environments, such as the supplier market, competition leads to positive organizational outcomes and encourages the pursuit of innovative ideas that improve performance. Moreover, different approaches [109,110] have found that an organizational culture responsive to employees positively affects knowledge-sharing, organizational innovation, and competitive advantage, thereby improving firm performance.

6. Conclusions

This study offers a new perspective on the interdependent relationships among structure, strategy, and performance in Romanian healthcare organizations, taking external environmental factors into account. It presents empirical evidence that supports several theoretical approaches in the literature. The research also addresses a primary question and a sub-question, with findings indicating:

- What are the circumstances surrounding the structure–strategy relationship and its consequences?

Healthcare organizations in Romania encounter challenges from competition, regulatory changes, and patient expectations. Three gestalts demonstrate different levels of adaptability to external pressures. Contextual factors, including organizational size, employee tenure, and external pressures (market competition, institutional regulations, and technological change), influence the interaction between structure and strategy. Larger, older organizations generally have more formalized and centralized structures, whereas smaller, younger organizations are more flexible and adaptive. These factors determine the degree of structural and strategic alignment achievable. The study shows that organizations with strong internal coherence among structure, strategy, and environmental requirements achieve better performance, while those lacking alignment experience inefficiencies.

- What are the implications of this alignment for organizational performance in Romanian healthcare?

The effect of structure–strategy alignment is evident across several performance dimensions. Organizations experiencing moderate external pressures tend to achieve higher patient satisfaction, financial stability, and improved internal processes. In contrast, those facing intense competition and regulatory constraints demonstrate greater innovation and adaptability. Organizations with poor alignment between structure and strategy perform poorly across all key indicators. SEM analysis confirmed that organizational design and strategic orientation positively affected performance, although their capacity to fully mediate external pressures was limited. These findings indicate that effective internal strategies can reduce challenges but cannot fully address systemic issues without government support and policy interventions.

6.1. Study Implications

First, regarding contributions to knowledge, this research produced significant findings at two distinct levels.

6.1.1. Theoretical Implications

This study develops a conceptual model that illustrates the interdependencies influencing healthcare performance and operationalizes these through the BSC framework developed by Kaplan and Norton [74]. By integrating contingency and gestalt theories, the research identifies conditions under which structural and strategic alignment maximizes performance outcomes. The model extends contingency theory [17] to contexts characterized by institutional volatility, resource dependence, and partial decentralization, which are typical of post-transition healthcare systems. It shows that contextual fit, rather than structural uniformity, determines performance variation, thereby refining the explanatory capacity of contingency theory.

In the Romanian context, this study expands the limited empirical research on the interaction among structural design, strategy, and performance in public healthcare institutions, where bureaucratic rigidity and resource dependency remain persistent challenges [46,62]. This localized evidence contributes to the regional literature by clarifying how internal coherence mechanisms function under administrative constraints specific to post-transition healthcare environments.

6.1.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer practical insights for healthcare management in Romania. Hospital leaders can improve performance by adopting flexible organizational structures that delegate operational authority closer to the point of care. Decentralizing decision-making and integrating multidisciplinary teams may reduce administrative bottlenecks and enable faster adaptation to changing regulations and patient expectations. Strengthening strategic planning and linking institutional goals to measurable outcomes through structured performance indicators can improve efficiency, transparency, and accountability.

At the system level, these results highlight the need to balance managerial autonomy with coherent governance. Romania’s healthcare sector would benefit from a policy framework that upholds national performance standards while allowing hospitals greater flexibility to allocate resources, innovate, and address local needs. Implementing phased, performance-based financing mechanisms could promote institutional accountability and ongoing improvement. The study’s findings may also inform the development of managerial training programs to enhance strategic thinking and adaptive leadership within healthcare organizations. Sustainable progress depends on stable, consistent policy implementation and empowering hospital managers to align internal capabilities with changing market and patient demands.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has limitations that indicate areas for further research. First, the data collection process faced challenges because some potential respondents were reluctant to participate in the survey. Second, the study’s focus on Romania, while relevant for understanding local healthcare dynamics, may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare systems. Third, respondent perceptions may be subjective, which could affect the interpretation of the relationship between organizational structure, strategy, and performance. Finally, the use of a snowball sampling approach and reliance on self-reported data may have led to overrepresentation of certain professional networks and perceptual bias in respondents’ assessments; these factors should be considered in future research.

Future research should compare private and public healthcare organizations to assess differences in governance, finance, and performance. Additionally, analyzing longitudinal data could reveal how strategic and structural alignment changes in response to environmental shifts. Expanding the study to other Eastern European or developing healthcare systems would improve the external validity of the findings. Future studies could also include a qualitative research phase to examine alternative conceptualizations of strategy and provide contextual insights into the formation and implementation of strategic orientations within healthcare organizations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.Ș. and I.P.; methodology, S.C.Ș.; software, S.C.Ș.; validation, S.C.Ș., I.P. and A.B.; formal analysis, S.C.Ș. and A.B.; investigation, S.C.Ș.; resources, I.P.; data curation, S.C.Ș.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., S.C.Ș. and I.P.; visualization, S.C.Ș.; supervision, I.P.; project administration, S.C.Ș. and I.P.; funding acquisition, S.C.Ș. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a result of research conducted within the postdoctoral advanced research program and the doctoral research program of the Bucharest University of Economic Studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Reliability and convergent validity of the measurement model.

Table A1.

Reliability and convergent validity of the measurement model.

| References | Constructs/Items | Variables | Loadings | a | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threat of substitute medical services and new competitors (ME_ASC) | 0.842 | 0.844 | 0.895 | 0.681 | |||

| [64,65,66] | The number of potential customers/patients is extremely high (1)/The number of potential customers/patients is extremely small (5) | ME_Conc8 | 0.760 | ||||

| A very large volume of investment is required for the establishment of a similar health unit (1)/The establishment of a similar health unit requires a minimum volume of investment (5) | ME_Conc11 | 0.847 | |||||

| Setting up a similar health unit requires an arduous and lengthy process (1)/The procedure involved in setting up a similar health unit is simple and fast (5) | ME_Conc12 | 0.877 | |||||

| Our former patients always come back to us when they need it (1)/Our former patients easily find and frequently turn to other similar healthcare providers (5) | ME_Conc16 | 0.811 | |||||

| Market dynamism/degree of uncertainty (ME_DI) | 0.744 | 0.745 | 0.855 | 0.663 | |||

| [64,65,66] | There is a well-defined and stable set of legal regulations that affect my organization’s activity (1)/Legislative changes that affect my organization’s activity are very common (5) | ME_Din3 | 0.750 | ||||

| In our medical field, the same competitors have been evolving for a long time (1)/In our medical field, new competitors are always appearing (5) | ME_Din4 | 0.825 | |||||

| In our geographical area, the same competitors have been evolving for a long time (1)/In our geographical area there are always new competitors (5) | ME_Din5 | 0.864 | |||||

| Intensity of competition (ME_IC) | 0.712 | 0.713 | 0.839 | 0.636 | |||

| [64,65,66] | In our geographical area, the supply of similar medical services/medicines is much lower than the demand (1)/The supply of similar medical services/medicines is much higher than the demand (5) | ME_Conc2 | 0.825 | ||||

| In our medical field, the supply of similar medical services/medicines is much lower than the demand (1)/The supply of similar medical services/medicines is much higher than the demand (5) | ME_Conc4 | 0.821 | |||||

| Our patients/clients may have great difficulty finding other providers of medical services/medicines similar to ours (1)/Our patients/clients could very easily find other providers of medical services/medicines similar to ours (5) | ME_Conc10 | 0.744 | |||||

| Bargaining power of suppliers (ME_PNF) | 0.751 | 0.752 | 0.858 | 0.668 | |||

| [64,65,66] | There is a very large number of potential suppliers of medical equipment, sanitary materials, etc. (1)/There is a very small number of potential suppliers of medical equipment, sanitary materials, etc. (5) | ME_Conc5 | 0.830 | ||||

| The supply of medical equipment, sanitary supplies, etc. is much higher than the demand (1)/The supply of medical equipment, sanitary supplies, etc. is much lower than the demand (5) | ME_Conc6 | 0.798 | |||||

| In case of need, we could find new suppliers very easily (1)/In case of need, we could find new suppliers with great difficulty (5) | ME_Conc7 | 0.824 | |||||

| External environment (ME)—second-order construct | 0.832 | 0.845 | 0.865 | 0.339 | |||

| ME_ASC | 0.862 | ||||||

| ME_DI | 0.566 | ||||||

| ME_IC | 0.596 | ||||||

| ME_PNF | 0.732 | ||||||

| Centralization (STC_CEN) | 0.856 | 0.859 | 0.897 | 0.635 | |||

| [71] | In my current activity, I have complete freedom to make the decisions and take the actions that I consider to be the most appropriate (1)/In my current activity, I must always act as my superiors have decided (5) | Struct_Centr1 | 0.826 | ||||

| When faced with unforeseen situations, I have complete freedom to make the decisions and take the actions that I consider to be the most appropriate (1)/When faced with unforeseen situations, I must always act as my superiors have decided (5) | Struct_Centr2 | 0.825 | |||||

| Employees with executive functions have full freedom to make decisions and take the actions they deem most appropriate (1)/Employees with executive functions must always act as decided by their superiors (5) | Struct_Centr3 | 0.759 | |||||

| Lower-level managers have full freedom to make decisions and take the actions they deem most appropriate (1)/Lower-level managers must always act as their superiors have decided (5) | Struct_Centr4 | 0.771 | |||||

| Mid-level managers have full freedom to make decisions and take the actions they deem most appropriate (1)/Mid-level managers must always act as decided by their superiors (5) | Struct_Centr5 | 0.801 | |||||

| Integration (STC_INT) So far, activities have been carried out in collaboration and cooperative relations with institutions and other entities positioned in the same geographical area, with the purpose and objectives set by common agreement | 0.866 | 0.870 | 0.900 | 0.601 | |||

| [67] | Central and local government bodies | Struct_Colab1 | 0.699 | ||||

| Non-governmental organizations | Struct_Colab2 | 0.817 | |||||

| Other medical institutions | Struct_Colab3 | 0.745 | |||||

| Universities | Struct_Colab5 | 0.808 | |||||

| Research and development institutes | Struct_Colab6 | 0.808 | |||||

| Others | Struct_Colab7 | 0.767 | |||||

| Complexity (STC_COM) | 0.840 | 0.841 | 0.887 | 0.610 | |||

| [68,69,70] | The organization has a very small number of employees (1–2) (1)/The organization has a very large number of employees (over 500) (5) | Struct_Compl1 | 0.760 | ||||

| The medical activity is carried out in a single department/laboratory/medical office (1)/The medical activity is carried out in more than 30 medical departments/laboratories/offices (5) | Struct_Compl2 | 0.828 | |||||

| Medical activity is carried out in a single office/work point (1)/The medical activity is carried out in more than 10 offices/work points (5) | Struct_Compl3 | 0.791 | |||||

| Medical activity is carried out in a single locality (1)/The medical activity is carried out in more than 10 localities (5) | Struct_Compl4 | 0.784 | |||||

| The organizational structure of the organization has 2 hierarchical levels (1)/The organizational structure of the organization has 8–10 hierarchical levels or more (5) | Struct_NivIerarh | 0.740 | |||||

| Formalization (STC_FOR) | 0.734 | 0.733 | 0.850 | 0.656 | |||

| [71] | The professional competence and experience of employees are considered sufficient to carry out administrative activities (1)/There are written procedures for most administrative activities carried out in the organization (5) | Struct_Form1 | 0.856 | ||||

| Professional competence and experience of employees are considered sufficient to carry out medical activities (1)/There are written procedures for most medical activities carried out in the organization (5) | Struct_Form2 | 0.843 | |||||

| Relationships between employees are generally informal (1)/Relationships between employees are formal, deriving from the hierarchical position they occupy (5) | Struct_Form4 | 0.723 | |||||

| Organizational Structure (SO)—second-order construct | 0.882 | 0.886 | 0.900 | 0.324 | |||

| STC_CEN | 0.659 | ||||||

| STC_INT | 0.673 | ||||||

| STC_COM | 0.816 | ||||||

| STC_FOR | 0.591 | ||||||

| Cost Leadership (STT_COST) To what extent are the following strategic priorities for your organization? | 0.895 | 0.895 | 0.922 | 0.704 | |||

| [62,64,72,73] | Reducing the cost of medical services/medicines below that of competitors | Str_AC_Cost1 | 0.874 | ||||

| Lowering healthcare costs through resource efficiency | Str_AC_Cost2 | 0.843 | |||||

| Elimination of all sources of costs that are not necessary | Str_AC_Cost3 | 0.811 | |||||

| Attracting as many customers/patients as possible by charging lower prices than competitors | Str_AC_Cost5 | 0.833 | |||||

| Decrease in the price of medical services/medicines provided below that of competitors | Str_AC_Cost6 | 0.832 | |||||

| Differentiation (STT_DIF) To what extent are the following strategic priorities for your organization? | 0.955 | 0.956 | 0.962 | 0.738 | |||

| [62,64,72,73] | Creating and maintaining a favorable image of the institution | Str_AC_Dif1 | 0.846 | ||||

| Paying close attention to creating and maintaining a good reputation for the institution | Str_AC_Dif2 | 0.838 | |||||

| Attracting and retaining top national/global specialists | Str_AC_Dif3 | 0.816 | |||||

| Endowment with high-performance medical equipment | Str_AC_Dif4 | 0.875 | |||||

| Existence of top technical equipment at national/world level | Str_AC_Dif5 | 0.856 | |||||

| Provision of medical services/medicines of higher quality than those of competitors | Str_AC_Dif6 | 0.890 | |||||

| Paying special attention to patient comfort (hotel conditions, environment, etc.) | Str_AC_Dif7 | 0.856 | |||||

| Ensuring easy access for patients regarding location, necessary formalities, etc. | Str_AC_Dif8 | 0.863 | |||||

| Professionalism and competence of the human resources | Str_AC_Dif9 | 0.887 | |||||

| Strategic Orientation (OS)—second-order construct | 0.948 | 0.950 | 0.955 | 0.603 | |||

| STT_COST | 0.815 | ||||||

| STT_DIF | 0.959 | ||||||

| Economic-financial perspective (PER_FIN) | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.929 | 0.687 | |||

| [74,75,76,77,78] | How do you assess the level of competitiveness of your organization? Compared to the objectives set | Perf_Fin_Comp1 | 0.834 | ||||

| Compared to that of the main competitors | Perf_Fin_Comp2 | 0.843 | |||||

| Compared to five years ago | Perf_Fin_Comp3 | 0.830 | |||||

| How do you assess the economic and financial performance of your organization? Compared to those of the main competitors | Perf_Fin_EF1 | 0.835 | |||||

| Compared to five years ago | Perf_Fin_EF2 | 0.802 | |||||

| Compared to the objectives set | Perf_Fin_EF3 | 0.828 | |||||

| Continuous Innovation and Development Perspective (PER_INO) | 0.858 | 0.887 | 0.913 | 0.778 | |||

| [74,75,76,77,78] | Within the organization, refresher courses and training are frequently organized | Perf_Inov4 | 0.921 | ||||

| Importance is attached to research activity | Perf_Inov5 | 0.808 | |||||

| Employees are supported to participate in specialized seminars and conferences | Perf_Inov6 | 0.913 | |||||

| Customer/Patient Perspective (PER_PAC) | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.962 | 0.717 | |||

| [74,75,76,77,78] | The medical services provided are affordable in terms of location, price, and waiting time | Perf_Pac1 | 0.806 | ||||

| Patients’ satisfaction with healthcare services is overall higher than in similar organizations | Perf_Pac10 | 0.864 | |||||

| Patients positively appreciate the quality of medical services in terms of interpersonal relationships | Perf_Pac2 | 0.858 | |||||

| The organization ensures continuity in providing medical care | Perf_Pac3 | 0.713 | |||||

| The medical services provided are appreciated as efficient by patients and medical staff | Perf_Pac4 | 0.882 | |||||

| The medical services provided are appreciated as effective by patients and medical staff | Perf_Pac5 | 0.882 | |||||

| There is complete safety in the process of providing medical care | Perf_Pac6 | 0.838 | |||||

| The medical services provided contribute substantially to improving the health of patients | Perf_Pac7 | 0.859 | |||||

| The medical services provided contribute substantially to increasing the quality of life of patients | Perf_Pac8 | 0.882 | |||||

| Patients’ satisfaction with medical services is on an overall upward trend | Perf_Pac9 | 0.872 | |||||

| Internal Process Perspective (PER_PI) | 0.873 | 0.878 | 0.922 | 0.798 | |||

| [74,75,76,77,78] | The organization has top specialists at the national/world level | Perf_ProcInt1 | 0.863 | ||||

| The organization has state-of-the-art medical equipment and technical equipment | Perf_ProcInt2 | 0.932 | |||||

| The organization has a high-performance information system | Perf_ProcInt3 | 0.885 | |||||

| Performance–Balanced Scorecard (PERF_BSC)—second-order construct | 0.954 | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.515 | |||

| PER_FIN | 0.894 | ||||||

| PER_INO | 0.697 | ||||||

| PER_PAC | 0.931 | ||||||

| PER_PI | 0.893 | ||||||

Source: Authors’ analysis with SmartPls 3.3.3 [81].

Table A2.

Cluster profiles.

Table A2.

Cluster profiles.

| Characteristics | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Differences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/M | %/SD | N/M | %/SD | N/M | %/SD | ||

| Size of clusters | 186 | 37.052% | 189 | 37.649% | 127 | 25.299% | |

| The type of sanitary facility | |||||||

| Hospital | 30.108% | 50.265% | 66.142% | ***

*** | |||

| Pharmacy | 11.290% | 11.640% | 12.598% | ||||

| Private medical practice | 32.258% | 6.878% | 10.236% | ||||

| Medical center | 26.344% | 31.217% | 11.024% | ||||

| Age of the organization | 16.462 | 16.825 | 18.513 | 18.902 | 27.890 | 27.191 | *** |

| Number of employees | 188.280 | 649.740 | 386.947 | 722.763 | 532.465 | 572.954 | *** |

Note: *** p < 0.001; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; W = Welch test for equal means. Source: Authors’ analysis with IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 [80].

Table A3.

Patterns of external environment and the organizational structure attributes.

Table A3.

Patterns of external environment and the organizational structure attributes.

| Variables | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Test for Equality of Means | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Clustering variables | |||||||

| The threat of substitute medical services and new competitors | 2.574 | 0.731 | 2.151 | 0.584 | 3.996 | 0.515 | 460.325 **a |

| Intensity of competition | 3.257 | 0.845 | 3.399 | 0.653 | 4.014 | 0.502 | 67.070 ***a |

| Bargaining power of suppliers | 2.950 | 0.849 | 2.878 | 0.803 | 4.005 | 0.557 | 140.506 ***a |

| Market dynamism/degree of uncertainty | 2.997 | 0.797 | 3.492 | 0.750 | 4.049 | 0.555 | 96.150 ***a |

| Integration | 2.369 | 0.730 | 2.881 | 0.860 | 3.552 | 0.856 | 79.876 ***b |

| Complexity | 2.267 | 0.864 | 2.955 | 0.793 | 3.853 | 0.655 | 172.725 ***a |

| Centralization | 2.744 | 0.918 | 3.222 | 0.902 | 4.096 | 0.623 | 128.928 ***a |

| Formalization | 2.907 | 0.855 | 3.741 | 0.750 | 3.969 | 0.656 | 83.957 ***a |

| Differentiation | 3.430 | 1.053 | 4.598 | 0.546 | 4.101 | 0.705 | 96.513 ***a |

| Cost leadership | 3.105 | 0.995 | 3.909 | 0.931 | 4.013 | 0.714 | 50.065 ***a |

| The range of strategic activities | 2.840 | 0.989 | 4.087 | 0.761 | 4.159 | 0.605 | 122.456 ***a |

| Implications assessment variables | |||||||

| Patients’ perspective | 3.558 | 0.957 | 4.279 | 0.719 | 3.930 | 0.757 | 34.610 ***a |

| Economic and financial performance | 3.176 | 0.794 | 3.862 | 0.675 | 3.764 | 0.801 | 43.894 ***b |

| Continuous innovation and development | 2.986 | 1.005 | 3.557 | 0.964 | 3.701 | 0.915 | 25.609 ***b |

| Internal processes perspective | 2.882 | 0.969 | 3.963 | 0.889 | 3.617 | 0.820 | 63.317 ***b |

Note: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; a: F test for equality of means; b: Welch test for equality of means (W). Source: Authors’ analysis with IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 [80].

Table A4.

Discriminant Validity of Measurement Model (HTMT).

Table A4.

Discriminant Validity of Measurement Model (HTMT).

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | ||||

| OS | 0.211 | |||

| PERF_BSC | 0.207 | 0.728 | ||

| SO | 0.563 | 0.236 | 0.272 |

Source: Authors’ analysis with SmartPls 3.3.3 [81].

References

- Dönmez, N.F.K.; Atalan, A.; Dönmez, C.Ç. Desirability Optimization Models to Create the Global Healthcare Competitiveness Index. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 7065–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureșan, G.M.; Mare, C.; Lazăr, D.T.; Lazăr, S.P. Can Health Insurance Improve the Happiness of the Romanian People? Amf. Econ. 2023, 25, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, R.C.; Kottapalli, P. Strategic Planning and Aggressiveness in Healthcare: Navigating Uncertainty for Organizational Success. Healthc. Strategy Rev. 2025, 1, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.H.; Luk, B.H. Patient Satisfaction: Concept Analysis in the Healthcare Context. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Cui, L. The Impact of Digital Technologies on Economic and Environmental Performance in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuchowski, M.L.; Henzler, D.; Alscher, M.D.; Nagel, E. The Impact of C-Level Positions on Hospital Performance: A Scoping Review of Top Management Team Outcomes. Health Policy 2025, 157, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Charan, P.; Chattopadhyay, M. Relational Capabilities and Performance: Examining the Moderation-Mediation Effect of Organisation Structures and Dynamic Capability. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2023, 21, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharari, N.M. The Interplay of Strategic Management Accounting, Business Strategy and Organizational Change: As Influenced by a Configurational Theory. J. Account. Organ. Change 2024, 20, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, G.; Daniels, K.; Mieris, F.; Delnoij, D.; van de Bovenkamp, H.; van der Nat, P. Redesigning Value-Based Hospital Structures: A Qualitative Study on Value-Based Health Care in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelseth, P.; White, B.E.; Mundal, I.; Eines, T.F.; Kritchanchai, D. Systems Modelling to Support the Complex Nature of Healthcare Services. Health Technol. 2021, 11, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, D.; Panle, R.A.; Wapmuk, S.E.; Auwal, I.M.; Okpara, A.J. Strategic Orientation and Employee Performance: The Role of Organizational Support. A Study of Primary Health Care Centres in Jos North LGA of Plateau State, Nigeria. Iris J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2024, 2, 45–59. Available online: https://irispublishers.com/ijebm/pdf/IJEBM.MS.ID.000539.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Breazu, A.; Olariu, A.A.; Popa, Ș.C.; Popa, C.F. The Level of Resources and Quality of the Health System in the Romanian Country. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell 2023, 17, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Romania: Country Health Profile 2023. Available online: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/country-health-profiles (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Cosma, S.A.; Bota, M.; Fleșeriu, C.; Morgovan, C.; Văleanu, M.; Cosma, D. Measuring Patients’ Perception and Satisfaction with the Romanian Healthcare System. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, I.; Barna, F.; Gurgus, D.; Tomescu, L.C.; Apostol, A.; Petre, I.; Bordianu, A. Analysis of the Healthcare System in Romania: A Brief Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlădescu, C.; Scîntee, S.G.; Olsavszky, V.; Hernandez-Quevedo, C.; Sagan, A. Romania: Health System Review; Health Systems in Transition; World Health Organization on Behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G.A. The Management of Innovation; Tavistock: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Organizations: Rational, Natural, and Open Systems; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vik, E.; Hansson, L. Contingency and Paradoxes in Management Practices—Development Plan as a Case. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2024, 38, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J. Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, D.S.; Hickson, D.J.; Hinings, C.R.; Turner, C. Dimensions of Organization Structure. Adm. Sci. Q. 1968, 13, 65–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jeilani, A.; Hussein, A. Impact of Digital Health Technologies Adoption on Healthcare Workers’ Performance and Workload: Perspective with DOI and TOE Models. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, F.; Bobini, M.; Meregaglia, M.; Fattore, G. Scaling Up Integrated Care: Can Community Hospitals Be an Answer? A Multiple-Case Study from the Emilia-Romagna Region in Italy. Health Policy 2024, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kok, K.; van der Scheer, W.; Ketelaars, C.; Leistikow, I. Organizational Attributes That Contribute to the Learning and Improvement Capabilities of Healthcare Organizations: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, S.C. Contingency Theory: Science or Technology? J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2003, 1, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleska-Spasova, E. Determinants and Measures of Export Performance—Comprehensive Literature Review. J. Contemp. Econ. Bus. Issues 2014, 1, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, S.M.; Strange, R.; Lashitew, A. The Export Performance of Emerging Economy Firms: The Influence of Firm Capabilities and Institutional Environments. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.; van Dun, D.H.; de Almeida, A.G. Leadership Behaviors during Lean Healthcare Implementation: A Review and Longitudinal Study. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N. Managing Organizational Change in Responding to Global Crises. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell 2023, 42, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Elten, H.J.; van der Kolk, B. Performance Management, Metric Quality, and Trust: Survey Evidence from Healthcare Organizations. Br. Account. Rev. 2024, 101511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, H.; Klein, J. Organisationsentwicklung im Gesundheitswesen. Med. Klin. 2002, 97, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayamga, M.; Annosi, M.C.; Kassahun, A.; Dolfsma, W.; Tekinerdogan, B. Adaptive Organizational Responses to Varied Types of Failures: Empirical Insights from Technology Providers in Ghana. Technovation 2024, 129, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, A.L.; Ţarcă, N.N.; Sasu, D.V.; Bodog, S.A.; Roşca, R.D.; Tarcza, T.M. Exploring Marketing Insights for Healthcare: Trends and Perspectives Based on Literature Investigation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, C.F.; Popa, Ș.C.; Gora, A.A. Analysis of Romanian IT Industry: Strategic Diagnostics Using Michael Porter’s Model. Bus. Excell Manag. 2019, 9, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Offenbeek, M.; Sorge, A.; Knip, M. Enacting Fit in Work Organization and Occupational Structure Design: The Case of Intermediary Occupations in a Dutch Hospital. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 1083–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abimbola, S.; Baatiema, L.; Bigdeli, M. The Impacts of Decentralization on Health System Equity, Efficiency and Resilience: A Realist Synthesis of the Evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezerins, M.E.; Ludwig, T.D. A Behavioral Analysis of Incivility in the Virtual Workplace. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2022, 42, 150–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, N.; Rosa, A.; Adinolfi, P. The Liaison between Performance, Strategic Knowledge Management, and Lean Six Sigma: Insights from Healthcare Organizations. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2023, 22, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Boesso, G.; Favotto, F.; Menini, A. Strategic Orientation, Innovation Patterns and Performances of SMEs and Large Companies. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, R.; Ferreira, J.J.; Simões, J. Understanding Healthcare Sector Organizations from a Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 588–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunger, A.C.; Choi, M.S.; MacDowell, H.; Gregoire, T. Competition among Mental Health Organizations: Environmental Drivers and Strategic Responses. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 48, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvais, B.; Pradhan, R.; Ramamonjiarivelo, Z.; Mileski, M.; Shanmugam, R. When Agency Fails: An Analysis of the Association Between Hospital Agency Staffing and Quality Outcomes. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2024, 17, 1361–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.E.; Al-Henzab, J.; Tarhini, A.; Obeidat, B.Y. The Associations among Market Orientation, Technology Orientation, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organizational Performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3117–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotea, C.C.; Ploscaru, A.N.; Bocean, C.G.; Vărzaru, A.A.; Mangra, M.G.; Mangra, G.I. The Link Between HRM Practices and Performance in Healthcare: The Mediating Role of the Organizational Change Process. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vătămănescu, E.M.; Alexandru, V.A.; Mitan, A.; Dabija, D.C. From the Deliberate Managerial Strategy Towards International Business Performance: A Psychic Distance vs. Global Mindset Approach. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Assaf, K.; Alzahmi, W.; Alshaikh, R.; Bahroun, Z.; Ahmed, V. The Relative Importance of Key Factors for Integrating Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems and Performance Management Practices in the UAE Healthcare Sector. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, A.D., Jr. Strategy and Structure: The History of the American Industrial Enterprise; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Schiavone, F.; Pluzhnikova, A.; Invernizzi, A.C. Digital Transformation in Healthcare: Analyzing the Current State of Research. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Dudley-Brown, S.; Terhaar, M.F. Translation of Evidence into Nursing and Healthcare; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wongsin, U.; Pannoi, T.; Prutipinyo, C.; Maruf, M.A.; Pongpattrachai, D.; Quansri, O.; Sattayasomboon, Y. Strategic Planning and Organizational Performance in Public Health Sector: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, C.; Flessa, S. Strategic Management in Healthcare: A Call for Long-Term and Systems-Thinking in an Uncertain System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N. The Concept of Fit in Strategy Research: Toward Verbal and Statistical Correspondence. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.; Soetanto, D.; Jack, S. A Contingency Theory Perspective of Environmental Management: Empirical Evidence from Entrepreneurial Firms. J. Gen. Manag. 2021, 47, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T.A. Different Response Paths to Organizational Resilience. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 61, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.M.; Shortell, S.M. The Governance and Management of Effective Community Health Partnerships: A Typology for Research, Policy, and Practice. Milbank Q. 2000, 78, 241–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, O.; Aktan, B.; Turen, S.; Javaria, K.; Abou ElSeoud, M.S. Which Resources Matter the Most to Firm Performance? An experimental study on Malaysian listed firms. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2017, 15, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsch, K.; Festing, M. Dynamic Talent Management Capabilities and Organizational Agility—A Qualitative Exploration. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassani, A.A.; Aldakhil, A.M. Tackling Organizational Innovativeness Through Strategic Orientation: Strategic Alignment and Moderating Role of Strategic Flexibility. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, I.; Brorström, S.; Gluch, P. Introducing Strategic Measures in Public Facilities Management Organizations: External and Internal Institutional Work. Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.; Raymond, L.; Rivard, S. Fit in Strategic Information Technology Management Research: An Empirical Comparison of Perspectives. Omega 2001, 29, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, S.C.; Popa, I.; Tărăban, I. Strategic Orientation of Romanian Healthcare Organizations according to Porter’s Generic Strategies Model. Systems 2023, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; First Free Press Edition: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Alrawashdeh, R. The Competitiveness of Jordan Phosphate Mines Company (JPMC) Using Porter Five Forces Analysis. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2012, 5, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fung, H.P. Using Porter Five Forces and Technology Acceptance Model to Predict Cloud Computing Adoption Among IT Outsourcing Service Providers. Internet Technol. Appl. Res. 2014, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, A.A.; Popa, I.; Ștefan, S.C.; Morărescu, C. The Potential for Cluster Implementation in the Romanian Healthcare System. In Proceedings of the International Management Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 31 October–1 November 2019; Popa, I., Dobrin, C., Ciocoiu, N.C., Eds.; Bucharest University of Economics Studies: Bucharest, Romania, 2019; pp. 436–447. [Google Scholar]

- Inkson, J.H.K.; Pugh, D.S.; Hickson, D.J. Organization Context and Structure: An Abbreviated Replication. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Droge, C. Psychological and Traditional Determinants of Structure. Adm. Sci. Q. 1986, 31, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Strategy Making and Structure: Analysis and Implications for Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1987, 30, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalay, F. The Impact of Organizational Structure on Management Innovation: An Empirical Research in Turkey. Pressacademia 2016, 5, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.E. Environments as Moderators of the Relationship Between Strategy and Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, S.C.; Popa, Ș.C. Exploring the Features of Health Organizations’ Competitive Strategies. In Proceedings of the 33rd IBIMA Conference—Education Excellence and Innovation Management Through Vision 2020, Granada, Spain, 10–11 April 2019; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): Granada, Spain, 2019; pp. 2942–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mavlutova, I.; Babauska, S. The Competitiveness and Balanced Scorecard of Health Care Companies. Int. J. Synerg. Res. 2013, 2, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mavlutova, L.; Balauska, S. Latvian Health Care Company Competitiveness Determining Indicators and Their Improvement Possibilities. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, H.; Kavosi, Z.; Shojaei, P.; Kharazmi, E. Key Performance Indicators in Hospital Based on Balanced Scorecard Model. J. Health Manag. Inform. 2016, 4, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ștefan, S.C.; Popa, I.; Dobrin, C. Towards a Model of Sustainable Competitiveness of Health Organizations. Sustainability 2016, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/spss-statistics-220-available-download (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/spss-statistics-220-available-download (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS, v 3.3.3; SmartPLS GmbH: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2015. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. Toward a New Contingency Approach: The Search for Organizational Gestalts. J. Manag. Stud. 1981, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. TwoStep Cluster Analysis. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/26.0.0?topic=features-twostep-cluster-analysis (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Fabi, B.; Raymond, L.; Lacoursière, R. Strategic Alignment of HRM Practices in Manufacturing SMEs: A Gestalts Perspective. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2009, 16, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS Path Modeling for Assessing Hierarchical Construct Models: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]