Abstract

Patient assistance with severe eating disorders (EDs) is covered in hospital institutions by the specialized service offered. To a lesser extent, these types of pathologies are treated from health prevention, and there are hardly any experiences of health promotion in EDs through social networks. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the messages about ED spread on TikTok, particularly those disseminated by international hospitals. For this, a systematic review of the scientific literature has been conducted, and the analytic tools Fanpagekarma and analisa.io have been used to analyse TikTok accounts of hospital entities and an intentional sample of different tiktokers with EDs or in recovery and people who show themselves as valid advisers in this matter, as well as their followers, respectively. Among the results obtained (due to volume and lack of transparency), the strategies of those who participate in TikTok to promote unhealthy eating habits are striking, as well as the amount of content presented against the spread of EDs that has the opposite effect on receivers. This study highlights the influence of TikTok on people affected by an eating disorder or are vulnerable to suffer from it and advocates for the spread of communication proposals via this social network that are supervised or led by health specialists who validate the content of the messages from a hospital environment to prevent such disorders. The definition of lines of action in communication by health institutions in this sense is shown to be necessary to prevent the appearance of EDs or to slow down their growth.

1. Introduction

1.1. Micro-Video

Nowadays, the industry of broadcasting short videos on the internet is living in its “golden age” and plays a key role in communication via social media [1]. With regard to TikTok, the increase in the use of this social media platform since its creation in 2016 has made it rank sixth in the world ranking of mobile applications in 2022 according to the Digital 2023 Report study published by WeareSocial and Meltwater [2]. In addition, the same study reflects the rise of TikTok to first place among social network applications by the average time of use per month per user throughout 2022. TikTok is the social media platform that allows users to create “micro-videos” (15″ to 60″) with music, filters and other elements that make them engage and currently maintains the fastest rate of expansion among social media [3]. Based on the report referred, which was published in 2023, the number of active TikTok users amounts to over one million monthly active users. These figures, according to the Digital 2023 Report, are lower than for Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram and WeChat but higher than the other platforms. In the XII Study of Social Media developed by IAB Spain [4], the significant increase in the introduction of TikTok in Spain is highlighted. Thus, video consumption has increased exponentially: Almost 9 out of 10 Spanish internet users are consumers of this type of product, and specifically within the prevalence of video, the referred research differentiates TikTok among the booming social media platforms.

Studies by Memon and Alavi [5] corroborate the data, placing China, India, the USA, Russia and Turkey as the countries with the highest number of TikTok users. Thus, it is not exceptional that Chinese government entities, which are aware of the potential of this social media platform, make use of micro-videos as a tool to strengthen communication and interaction with citizens [6,7].

In accordance with data from the Global Web Index Study [8], 41% of TikTok users are between 16 and 24 years old. In Arkansyah et al.’s estimate [3], the 18–24 age group is the one with the highest number of TikTok users with 37.3% of the 23 million users; the second largest group is the 25–34 age group with 33.9%, while the over-65 age group has the lowest number of users (only 1.6%).

1.2. Causes of TikTok Use and Effects on Users

Memon and Alavi [5] have shown how the use of TikTok during the pandemic has personally, academically and socially changed the lives of adolescents and young people. For Cervi [9], the fact that this social media platform has the capacity to influence social behaviour, modify habits and lifestyles and that it represents the “mirror” of Generation Z “which will soon make up more than a third of the world’s population” deserves more attention from a scientific perspective. McCashin and Murphy [10] share the same view when they rank TikTok as the fastest-growing social network among children and young people, although they claim it is still poorly studied in certain academic circles.

Among the reasons for the quick implementation and positioning of TikTok as a global communication platform, Jiani [11] points out that this social media platform “satisfies the audience’s psychological needs such as social interaction, psychological transformation and respect by precise positioning, and combines effective online and offline promotion strategies”. In the same way, Ma et al. [12] point out that the loyalty of users of this social media platform is, to a large extent, boosted by the satisfaction they receive, which in turn is encouraged by how they value feedback—likes, comments, followers, among other actions of interactions.

According to studies on external and psychological factors affecting users’ behaviour [13], in addition to the content being of interest to the audience, the social function of micro-video, together with its ease of use, are elements which play in favour of its development. TikTok adopts algorithms to personalise what is shown to different users when they browse videos according to their searches [14]. Along with the satisfaction of users’ needs and the variety of effective marketing strategies using accurate algorithms that support the booming internet industry of short videos, Xu et al. [1] point out negative aspects or threats of TikTok to users, such as a large amount of fake content and the weakness of the social media platform to monitor messages that may confuse the user. All of this adds to the effect influencers have on these types of communication channels on a large number of followers when, despite not being experts in the subject for which they postulate, they make risky and not always evidence-based recommendations without assessing the health impact that their actions may cause [15].

1.3. TikTok and Eating Disorders

In the healthcare field, communication via social media has a long history [16,17] fundamentally directed by patients and families, people with certain pathologies and healthcare professionals, among other agents in the healthcare community [18] who, in most cases, lack the scientific knowledge and rigour to support advice, recommendations and even medical diagnoses. The scientific literature describes both positive and negative aspects of health content on social media, although in general, it is common for health corporations as guarantors of the quality of care they offer to citizens to be more wary of disseminating content on social media [7].

If we look at mental illnesses, the Global Web Index 2021 study [19] warns of a clear correlation between the consumption of social media in particular and online news outlets with these pathologies, explaining the increase in prevalence to a large extent to situations of confinement and isolation of the population due to the pandemic. Social media influences the way in which social relationships are produced, as well as the configuration of personalities [20]. According to data published in 2021 by the Spanish Ministry of Health, the overall prevalence of mental health problems in Spain is 27.4% (30.2% in the case of women) with unemployed people being especially sensitive—a situation that has worsened during the pandemic.

As highlighted by the Eating Disorders Coalition (EDC) [21], eating disorders (EDs) are the second leading cause of death among mental illnesses after opium addiction. They argue that EDs can be successfully treated, but only a third of sufferers receive adequate healthcare, and at least 1 person dies every 62 min as a direct consequence of an eating disorder.

Galmiche et al. [22] draw attention to the growing prevalence of eating disorders. In their study carried out between 2000 and 2018, an overall increase of 3.5% in this type of disorder was recorded in the period between 2000 and 2006 and 7.8% between 2013 and 2018. For these researchers, the results represent a real health challenge.

The non-profit organisation Associació contra l’Anorèxia i la Bulímia (ACAB), which is driven by family members and specialists from the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, warns that during confinement, the number of consultations on EDs have tripled.

Among the different types of EDs that are defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) [23], anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder, unspecified eating disorder, non-nutritive substance intake, rumination disorder, among others, the first two are the most common according to the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (SEMFYC). Among the characteristics of AN, Buitrago et al. [24] emphasise “the refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight, fear of gaining weight and an altered perception of body shape or size”. In the case of BN, the specialists describe “repeated episodes of excessive food intake and an exaggerated preoccupation with body weight control, leading the sufferer to adopt extreme compensatory measures”.

In social networks where the ideal of beauty associated with thinness is widespread, unhealthy measures related to diet or disordered eating attitudes are promoted in order to achieve a change in body image associated with greater personal satisfaction, which is something unrealistic or unattainable [25]. The growing number of cases of inappropriate eating habits promoted by social media in an increasingly younger population in certain countries or geographical areas is a fact, as demonstrated by studies and reports on the subject endorsed or conducted by the World Health Organization and independent research [26,27]. Statistical studies reflect how EDs and TikTok have a common target audience, adolescents and young women, whose numbers doubled during the period of confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic [28]. The topic of anorexia, as the most prevalent eating disorder, is “very common” on TikTok, as corroborated by these researchers who note that “while most “pro-ana” (pro-anorexia) videos, where users exchanged advice on how to pathologically lose weight, have been censored by the application, other “anti-pro-ana” (anti-pro-anorexia) videos, officially aimed at raising awareness of the consequences of anorexia, have become increasingly popular” [29]. In one way or another, this content remains on the social media, which, according to Logrieco et al. [28], even in cases where it criticises and attacks pro-anorexia behaviours, this content pushes at-risk users to emulate behaviours that are harmful to their health, as both EDs and self-harming behaviours are present in the application, although in disguise. The authors believe that this type of content is shown to teenagers who are uncomfortable with their image and lack self-confidence, making it very easy to find messages that can be psychologically and physically harmful to the most fragile people.

Given this scenario, researchers draw attention to the need for prevention in this type of pathology, offering models based on scientific evidence, such as those of Losada and Crestani [29] and Ramírez-Cifuentes et al. [30], provided that it is carried out by specialists or qualified health administrations. In this sense, authors consider it more than necessary to develop more research in the field of social media and TikTok [31]. In addition, they believe that it is desirable to combine efforts between different specialists, researchers, doctors, advocates, and corporations to identify cases and inform and influence the conversation that takes place in social networks, such as TikTok [32].

At present, few specialised healthcare entities communicate through TikTok, and the content of their messages is not always related to health prevention or health promotion. However, most of the organisations analysed in this study stand out for their number of followers and the interaction they achieve with their followers. With greater knowledge of the manifestations and needs of tiktokers who express themselves online about EDs, proposals were outlined for improving health communication that hospital centres could adopt in order to improve the quality of life and well-being of patients and their families.

The main objectives of the research were to evaluate the effectiveness of messages from hospital institutions via TikTok in terms of health prevention measures and to propose communication actions aimed at specialised healthcare centres to prevent or reduce the risk of suffering from eating disorders in teenagers and young people.

2. Materials and Methods

Firstly, the methodological triangulation developed began with a systematic review of scientific literature related to hospital communication on aspects related to eating disorders via TikTok. Communication research on the social media platform TikTok is relatively recent considering that the history of this communication channel is about seven years old. Despite the large number of publications found, this is reduced if we limit the study to health communication via TikTok and, even more so, if we concentrate this activity on the field of hospital care and eating disorders as mental health disorders. The advances in research found in studies on EDs and their relationship with communication via social media have served, to a large extent, as a reference in the development of this article.

With the aim of presenting valid proposals that can be used by hospital institutions to offer prevention messages to the population or help patients with EDs and their families through micro-videos whose impact on society is increasing, two methodological tools have been used: Fanpagekarma and analisa.io. Data collection took place during the last quarter of 2021 for further analysis in 2022.

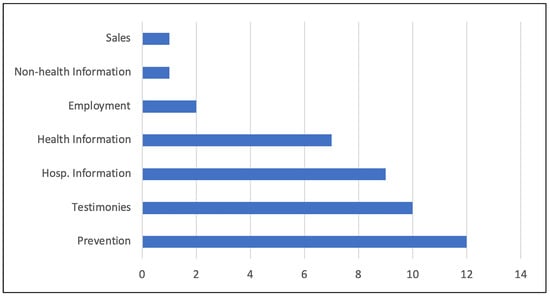

Since 2021, Fanpagekarma has offered the possibility of quantitatively analysing and comparing accounts on TikTok: rates of evolution, activity and interaction on the network, among other aspects. This tool was used to record the degree of interaction of hospital accounts with their followers, number of “likes”, as well as other information about the corporate account (country, year in which it started its activity on TikTok and number of videos broadcast) (Table 1). In addition, a qualitative content analysis of the videos was carried out in which different categories were determined into which these messages could be categorised following the classification made by Rando-Cueto et al. [18] in a previous study: information about the hospital; health information; health promotion; citizen service information; sale of products and services; recognition; social media and non-health information. An additional category was added to these: recruitment/employment of professionals since two hospitals use this social media to recruit staff [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Classification of contents of hospital TikTok accounts and dissemination on the web and social media. The data for the web pages in this table were accessed on 10 January 2022.

Figure 1.

Typology of content in TikTok hospital accounts.

The interest of this methodological action lies in gathering objective data with which to evaluate the communicative activity of hospitals on TikTok, particularly in the field of prevention and health promotion, in order to assess the effect it has on the population.

Specifically, a search was conducted on Fanpagekarma for all the TikTok accounts of hospital institutions found at international level, which were identified with the root of the term “hospital” translated into 38 languages—Albanian, German, Belarusian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Catalan, Czech, Croatian, Danish, Slovak, Croatian, Czech and Slovakian, Croatian, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Galician, Greek, Hungarian, Irish, Icelandic, Italian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Macedonian, Maltese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian and Yiddish. In this way, hospital care centre accounts have been registered from countries where any of these languages are spoken, as well as from countries where the mother tongue is not European, but which have appeared in the search process.

On the other hand, the tool analisa.io was used to evaluate the sample of profiles of a total of 40 tiktokers. For the identification and selection of the sample, a search was developed in TikTok by hashtags using those published by Logrieco et al. [28]; Sukunesan et al. [33] and Maliguetti et al. [34] in previous studies on ED communication on social media. Other terms that were identified in the scientific literature analysed were added to these terms, as well as in the Eating Attitudes Test-26, a clinical test considered by the scientific community as a validated questionnaire for the detection of EDs [35]. In total, a list of 30 terms was compiled1.

These profiles were classified into three groups: A. Patients diagnosed with ED or presenting as such; B. Patients with ED who claim to be in the process of recovery from eating disorders according to their testimony and C. People who consider themselves to have the authority to advise or “guide” patients with the aforementioned disorders. The information collected was cross-checked with the data obtained by dividing the sample into influencers or “opinion leaders” in the online environment who have “a certain credibility on a specific topic and whose presence and influence in social media makes them an ideal prescriber” [36] and non-influencers. In this way, it was determined which groups have the largest number of followers.

In turn, the accounts and comments of three followers of each of the 40 selected tiktokers were analysed in order to expand the number of profiles analysed to a total of 160. The first three followers who had reacted and/or engaged in conversation with the original emisor and whose comments were understandable and related to the initial message were collected.

Based on the design of a codebook used to examine tweets from pro-ED profiles on Twitter [37], this was adapted for the analysis of profile videos on TikTok. In addition, quantitative information was recorded for these profiles: year of start of activity, gender, place of recording, objective description of the image and qualitative information following the classification of emotions made by Maliguetti et al. [34] for the description of tiktokers appearing in the videos. The set of 120 registered followers and their comments was reached using the methodological analysis technique “Snowball Sample” [38,39].

3. Results

Eighteen accounts of private health administrations were analysed, to which three ministries of public health were added in order to include the activity of public institutions in the health sector. All of them started their activity on TikTok in 2019 and have a number of followers which, except in the case of the account of the Orden Hospitalaria San Juan de Dios in Quito, exceeds half a thousand, with the Phyathai Hospital in Thailand and Klinikum Dortmund in Germany reaching around 80,000 and Sikarin Hospital in Thailand exceeding 100,000.

Table 1 shows the TikTok accounts analysed, as well as their predominant content (ordered by prevalence), according to the classification previously referred to by the authors Rando-Cueto et al. [18] to which the term recruitment/employment has been added due to its appearance in the records analysed. In this way, the messages have been classified into the following contents: information on hospital activity (Hospital Information); information on health-related issues (Health Information); information on aspects not related to the hospital or health (Non-health Information); Testimonies; preventive measures (Prevention); Recruitment and Sale—of health products or services. Table 1 also shows other channels used by the healthcare institutions analysed (websites and social media) as a sample of their communication activity.

The number of followers does not always correspond to greater interaction from the receptors, with the Scandinavia Hospital Centre in Russia standing out in this respect. Nevertheless, the percentage of interaction is outstanding and is related to the number of followers and the number of “likes”. For the calculation of this index, only the number of “likes” given to the publicly disseminated videos was considered in relation to the number of followers of the accounts. Neither the number of comments nor the number of videos shared have been accounted for so as not to duplicate the counting of interaction actions.

Considering the year in which the TikTok activity began, as well as the number of videos disseminated (an average of 64 videos per hospital in two years), the engagement figures of the followers of the hospital accounts that interact with the health institution stand out.

The content shown in the published videos is largely related to health prevention: 12 of the 21 accounts analysed (Figure 1). The interaction achieved by these profiles based on the number of likes (no. likes/no. followers ×100) is significant compared to the feedback they receive through other communication channels.

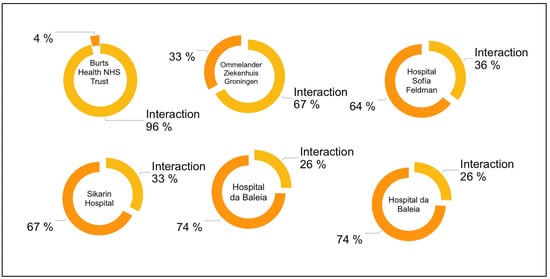

Figure 2 shows the percentage of the interaction of the five hospital TikTok accounts with the highest number of likes for videos published with healthcare content related to improving the quality of life and well-being of patients, avoiding pathologies or reducing their side effects: prevention and healthcare promotion.

Figure 2.

Interaction percentages: (no. likes/no. followers) ×100 of the five hospital accounts on TikTok highlighting content on health prevention with the highest response rate.

Testimonies are also frequent either from professionals or from patients and relatives, as well as information about the hospital itself and health information. Despite the fact that the hospitals under analysis are privately managed and administered, only one video from one of the accounts shows a product for sale. On the other hand, although only two hospitals use social media to recruit professionals, this communication action is significant due to its exceptional nature.

For Health Ministries, it should be pointed out that in the three selected accounts, prevention is the predominant content. The Spanish Ministry of Health only broadcasts one video with an image and voice-over; despite its exceptional activity, it does have an outstanding rate of interaction (33.85% of the followers of the @ministeriodesanidad account on TikTok liked—as of 30 September 2021—the video broadcast in 2020).

Regarding the analysis of the profiles selected after the search by hashtags, it should be noted that 100% of the accounts analysed, both those selected in a first filter and those of their followers, correspond to videos of young and adolescent females from 13 years of age (as identified in the network).

Although there are accounts and hashtags—such as #proana, #ana, #anorexia, #thinspiration, etc.—that the social media platform itself blocks and links to platforms that help patients and families, as well as offering guidelines to follow and “help materials” for recovery from this type of disorder, other similar terms related to eating disorders are very popular, and the algorithms used on the social media platform identify them as suitable for dissemination.

As mentioned above, in the classification, we divided the profiles found into groups according to whether or not they are people with an ED who recognise their disorder but who are not in the recovery phase (ED: 47.5%); people in recovery from a diagnosed eating disorder or who identify themselves as such (ED Recovery: 40%) and people who in this article are called “guides” and who are those who offer advice, recommendations, warnings or indications about how to act, generally taking on the role of specialists in the field (“guides”: 12.5%).

Of the 40 accounts chosen in a first analysis, more than half (27, 67.5%) correspond to influencer profiles with more than 100,000 followers (Table 2), with the profiles of @claudiap_psicologia and @victoriagarrick4 standing out with nearly 11 million and 59 million likes, respectively. Both belong to the “Guide” type (C) according to the classification despite this being the least represented group overall.

Table 2.

Accounts of the profiles analysed that are classified as influencers with more than 100,000 followers.

If we look at the emotions expressed according to the categories “happiness”, “neutral”, “fear”, “disgust”, “anger”, “contempt” and “sadness” established by Maliguetti et al. [34], according to the analysis of images, the results are not conclusive. Some 17.5% of the accounts only show videos of the abdomen without faces either dancing or posing, so these profiles would be classified in the “neutral” category or would not be classified at all. As far as the “happiness” category is concerned, 37.5% of the profiles broadcast moments of happiness. However, it is difficult to determine whether these instances—seconds in which the videos are broadcasted—last over time. Nevertheless, it is notable that in 45% of the cases analysed, negative emotions of sadness, disgust, contempt, fear or anger are expressed towards the same person shown in the publication, as the image is accompanied by text—comments or terms—in this sense. Most of the videos in which these types of feelings are shared appear poorly lit or with black and white images with texts about calories consumed or pejorative terms.

In 120 profiles of selected followers, empathy with the tiktoker is the predominant manifestation (Table 3) with messages of encouragement and positive reinforcement standing out in 21.67% of cases; of positive identification (about the achievements made in the face of an eating disorder), 14.17%; of negative identification (revealing being in the same situation of despair, depression, incomprehension, etc.), 39.17%; as well as messages of encouragement and positive identification (revealing being in the same situation of despair, depression, incomprehension, etc), 39.17%; as well as consultations for weight loss and advice for weight loss, 25%. Some of the accounts selected, two in the cases analysed, are “secret accounts”, as these are called, and create a more closed community in which messages of identification predominate.

Table 3.

Comments from followers of the accounts analysed (with the same spelling and iconography as the original messages).

Among the messages in which they share negative feelings, those in which they directly ask for help to overcome a mental disorder stand out, as well as those in which they offer advice that threatens their health, such as actions that encourage vomiting, weight loss or disguising their deteriorating physical condition in front of others.

4. Discussion

The publication of written or audiovisual testimonies does not infringe on the privacy of minors, firstly, because the messages analysed are public, and the domains of the selected tiktokers refer to profiles not individuals. The limitations of this study are related to the enormous number of messages that proliferate on social media about the cult of image and the care of physical and psychological state, which can be confused with those that contain harmful content or that could harm those who suffer from an eating disorder. Another limitation of this study is that due to the rapid spread of TikTok accounts even by health institutions, the analysis may miss information related to possible new initiatives that have occurred subsequently. In any case, we consider this type of analysis to be necessary in order to provide evidence of health communication activity via social networks at a given time and the need for further research in this area for that very reason.

Without ignoring the risk that social media platforms, in particular, TikTok, pose to people with eating disorders or those recovering from an eating disorder, adolescents and young people, followers of influencers who are shown to be experts in weight loss that they consider healthy, etc. [28,37], the intention of this article is to propose an alternative for the dissemination of messages through this channel to prevent this situation. In a society in which the worship of image takes on special relevance [25], there are authors who warn of the influence that the media can have on citizens so that they try to achieve a “normal” weight in accordance with the canons of beauty that are broadcast mainly through social networks [24,26,27]. However, these same channels, thanks to their potential to change behavioural habits [9], can be used to prevent or stop the development of harmful eating habits that have increased in recent times [22].

In this way, specialised healthcare institutions can play a fundamental role in terms of hospital communication through one of the social media platforms that has grown the most in recent years and has provoked the most interaction among one of the populations most affected by mental disorders. Planning and specialisation when developing health promotion and prevention content via TikTok could change the perception that many adolescents and young women have of their bodies and the way they take care of them, which leads to behaviour that is harmful to themselves, and at the same time, so can greater control of the accounts that incite this type of action, as well as a greater definition of the algorithms that promote their traffic on the network. Without questioning the professionalism of those who have been called “guides” in this study, it will be necessary to pay attention to those who issued judgments or advice masking unhealthy lifestyles with positive messages from idealized figures. It is considered vital that society in general and specialised care centres in particular become more aware of the existence and increasing number of people with EDs as a mental health disorder. The potential of social media platforms, such as TikTok, and their capacity to influence precisely the portion of the public most affected by or vulnerable to eating disorders is a reason for communication strategies aimed at the prevention of these disorders to be drawn up. The importance of this activity being supervised or directed by health and communication specialists who validate the quality of the content of the messages is fundamental in order to give the videos well-founded credibility.

5. Conclusions

From the results obtained, firstly, there is a notable lack of hospital accounts on TikTok, particularly in the case of Spain where none were found to the date of this study, although there are health-related profiles of healthcare professionals or those who identify themselves as such at an individual level. Despite this, most of the specialised healthcare entities that have been analysed at an international level obtain high performance in terms of the number of followers, likes, number of videos published and engagement, with health content related to prevention and health promotion being the predominant one.

On the other hand, the scientific literature has contrasted the increase in the use of the social media platform TikTok since its creation, especially among the young population. At the same time, this public group has been identified as the group most affected by the increase in mental health pathologies during the years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the research, eating disorders, one of the most prevalent mental disorders among women, adolescents and young people, have found the “micro-videos” that are disseminated on social media platforms such as TikTok to be a favourable environment for their propagation. Although social media itself blocks access to certain content related to EDs, it is easy to find and interact with profiles that either promote this type of disorder (which could lead to self-harm or encouragement to suicide) or explicitly reject it. In most cases, this set of profiles becomes influencers, promoters of behaviour. The empathy generated by tiktokers can lead to the creation of communities that feed off each other mainly through their identification and encouragement of negative feelings (rejection of their own body, depression, anger, anguish, etc.) and, to a lesser extent, through their positive reinforcement.

In addition to these groups, there are profiles in which someone who is not identified as a specialist in the field advises and “guides” possible patients diagnosed with EDs or people at risk of suffering from an ED. These types of messages are confused among the huge amount of videos on image worship and supposedly healthy lifestyles.

Finally, thanks to the characteristics of social networks as communication channels and the possibility of collecting data from the interlocutors who participate in them, health institutions can obtain valuable information from their users, which they can use to improve the healthcare provided to citizens. For all of the above reasons, we consider it essential to encourage research into health communication via social networks, such as TikTok, due to the specific characteristics described above and, in particular, on eating disorders due to their prevalence and consequences among certain social groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; methodology, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; software, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; validation, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; formal analysis, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; investigation, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; resources, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; data curation, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; visualization, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; supervision, D.R.-C., C.d.l.H.-P. and F.J.P.-R.; project administration, C.d.l.H.-P.; funding acquisition, C.d.l.H.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad de Málaga/CBUA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Hashtags used in the TikTok search: #anorexia, #thininpiration, #thinspo, #thyinspiration, #eatingdisorder, #fitinspiration, #body, #proana, #ana, #promia, #redbraceletpro, #skinny, #bonespo, #ED book review, #thighgap, #collarbones, #BED, #whatIeatinaday, #anamiax, #princesaanaymia, #tca, #aut0les1ones, #fyp, #ff, #quecomoenundia, #wannarexia, #weightlosscheck, #weightlossHacks, #edrecovery, #binge. |

References

- Xu, L.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Z. Research on the Causes of the “Tik Tok” App Becoming Popular and the Existing Problems. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2019, 7, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We Are Social. Meltwater Digital 2023 Global Overview Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.meltwater.com/en/global-digital-trends (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Arkansyah, M.; Prasetyo, D.; Amina, N.W.R. Utilization of Tik Tok Social Media as A Media for Promotion of Hidden Paradise Tourism in Indonesia. SSRN J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAB Spain. XII Estudio de Redes Sociales 2021; IAB Spain: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-de-redes-sociales-2021/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Memon, A.; Alavi, A.B. Tik-Tok Usage during COVID-19 and It’s Impacts on Personal, Academic and Social Life of Teenagers and Youngsters in Turkey. SSRN J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dong, J.; Qi, X.; Deng, J. Intention to use Governmental Micro-Video in the Pandemic of Covid-19: An Empirical Study of Governmental Tik Tok in China. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 January 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 976–979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Evans, R. How Health Communication via Tik Tok Makes a Difference: A Content Analysis of Tik Tok Accounts Run by Chinese Provincial Health Committees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Web Index. The Consumer Trends to Know: 2019. Available online: https://www.gwi.com/2019-consumer-trends (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Cervi, L. Tik Tok and generation Z. Theatre Danc. Perform. Train. 2021, 12, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCashin, D.; Murphy, C.M. Using TikTok for public and youth mental health—A systematic review and content analysis. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiani, W. Why is music social short video software popular? Taking the Douyin App as an example. New Media Res. 2017, 3, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Feng, J.; Feng, Z.; Wang, L. Research on User Loyalty of Short Video App Based on Perceived Value—Take Tik Tok as an Example. In Proceedings of the 2019 16th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management (ICSSSM), Shenzhen, China, 13–15 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Tao, X.; Wang, Y. Impact Analysis of Short Video on Users Behavior: Users Behavior Factors of Short VideoEvidence from Users Data of Tik Tok. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on E-Business and Applications, Sejong, Singapore, 24 February 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Lu, Z. Fifteen Seconds of Fame: A Qualitative Study of Douyin, A Short Video Sharing Mobile Application in China. In Social Computing and Social Media. Design, Human Behavior and Analytics; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11578, pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Marín, G.; Bellido-Pérez, E.; Trujillo Sánchez, M. Publicidad en Instagram y riesgos para la salud pública: El influencer como prescriptor de medicamentos, a propósito de un caso. Rev. Esp. Comun. Salud. 2021, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, A.B.; Schindelar, J.; Weaver, J.B. Social Media Engagement and Public Health Communication: Implications for Public Health Organizations Being Truly “Social”. Public Health Rev. 2013, 35, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Evans, R.; Chen, Y. The Effect of Online Effort and Reputation of Physicians on Patients’ Choice: 3-Wave Data Analysis of China’s Good Doctor Website. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rando Cueto, D.; Paniagua Rojano, J.; de las Heras Pedrosa, C. Influence Factors on the Success of Hospital Communication via Social Networks. Rev. Lat. de Comun. Soc. 2016, 71, 1.170–1.186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Web Index GWI. Connecting the Dots. 2021. Available online: https://www.gwi.com/connecting-the-dots (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Alex Sánchez, M.D. Anorexia and Bulimia: Impact on Network Society. Rev. Enferm. 2015, 38, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- EDC—Eating Desorders Coalition. Faces about Eating Disorders: What the Research Shows. 2019. Available online: https://eatingdisorderscoalition.org/inner_template/facts_and_info/facts-about-eating-disorders.html (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (Ed.). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-89042-577-0. [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago Ramírez, F.; Tejero Mas, M.; Pagador Trigo, Á. Trastornos de la conducta alimentaria y de la ingestión de alimentos. Actual. Med. Fam. Soc. Española Med. Fam. Comunitaria 2019, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Martinez, P.; Perea-Moreno, A.J.; Martinez-Jimenez, M.P.; Redel-Macías, M.D.; Pagliari, C.; Vaquero-Abellan, M. Social Media, Thin-Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes: An Exploratory Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elías Zambrano, R.; Jiménez-Marín, G.; Galiano-Coronil, A.; Ravina-Ripoll, R. Children, Media and Food. A New Paradigm in Food Advertising, Social Marketing and Happiness Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaña, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M.; Vàzquez, M. Food Advertising and Prevention of Childhood Obesity in Spain: Analysis of the Nutritional Value of the Products and Discursive Strategies Used in the Ads Most Viewed by Children from 2016 to 2018. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logrieco, G.; Marchili, M.R.; Roversi, M.; Villani, A. The Paradox of Tik Tok Anti-Pro-Anorexia Videos: How Social Media Can Promote Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Anorexia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, D.E.; Crestani, F. A Test Collection for Research on Depression and Language Use. In Experimental IR Meets Multilinguality, Multimodality, and Interaction; Fuhr, N., Quaresma, P., Gonçalves, T., Larsen, B., Balog, K., Macdonald, C., Cappellato, L., Ferro, N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9822, pp. 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cifuentes, D.; Mayans, M.; Freire, A. Early Risk Detection of Anorexia on Social Media. In Internet Science; Bodrunova, S.S., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11193, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruccoli, J.; De Rosa, M.; Chiasso, L.; Perrone, A.; Parmeggiani, A. The use of TikTok among children and adolescents with Eating Disorders: Experience in a third-level public Italian center during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriger, J.A.; Thompson, J.K.; Tiggemann, M. TikTok, TikTok, the time is now: Future directions in social media and body image. Body Image 2023, 44, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukunesan, S.; Huynh, M.; Sharp, G. Examining the Pro-Eating Disorders Community on Twitter Via the Hashtag #proana: Statistical Modeling Approach. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e24340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malighetti, C.; Chirico, A.; Sciara, S.; Riva, G. #Eating disorders and Instagram: What emotions do you express? Annu. Rev. Cybertherapy Telemed. 2019, 17, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Nieto, B. El influencer: Herramienta clave en el contexto digital de la publicidad engañosa. Methaodos Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2018, 6, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseniev-Koehler, A.; Lee, H.; McCormick, T.; Moreno, M.A. #Proana: Pro-Eating Disorder Socialization on Twitter. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handcock, M.S.; Gile, K.J. Comment: On the Concept of Snowball Sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.T. Snowball Sampling and Sample Selection in a Social Network. SSRN J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).