Simple Summary

Male infertility represents an important public health problem worldwide. There are many factors behind male infertility, including endocrine dysfunctions. Hormones play a crucial role in the male reproductive system. In particular, testosterone, which seems to be the principal hormone implicated in testicular function, specifically regulates spermatogenesis. This study aimed to determine the relationship between testosterone and DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and semen parameters. This was a prospective study that included 214 men aged 25–45 undergoing infertility evaluation. Participants were classified into two groups according to serum testosterone levels: low testosterone and normal testosterone. The results of the present study indicate that low testosterone levels are associated with increased DNA damage. Furthermore, reduced testosterone levels are linked to global alteration of the sperm quality, particularly affecting concentration, motility, morphology, and vitality of spermatozoa.

Abstract

(1) Background: Testosterone plays a key role in spermatogenesis and in maintaining semen quality and sperm DNA integrity. Consequently, reduced testosterone levels may disrupt these processes and contribute to male infertility. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of low testosterone levels on semen parameters, sperm DNA fragmentation, and chromatin condensation; (2) Methods: This was a prospective study that included 214 men aged 25–45 years undergoing infertility evaluation. Participants were classified into two groups according to serum testosterone levels: low testosterone and normal testosterone. Total testosterone was determined using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. Semen analysis was carried out according to the WHO 2021 guidelines. The DNA fragmentation index was assessed using the TUNEL assay. The sperm decondensation index was evaluated by aniline blue staining; (3) Results: Men with low serum total testosterone levels (<2.64 ng/mL) exhibited significantly impaired semen parameters compared with those with normal testosterone levels. Serum total testosterone was positively correlated with sperm concentration (rs = 0.43, p < 0.001), total motility (rs = 0.20, p = 0.005), normal morphology (rs = 0.25, p < 0.001), and sperm vitality (rs = 0.173, p = 0.014). In contrast, testosterone levels were negatively correlated with the DNA fragmentation index (rs = −0.221, p = 0.0017) and the chromatin decondensation index (rs = −0.19, p = 0.0086). A higher proportion of pathological DFI (>15%) was observed in the low testosterone group. (4) Conclusions: These findings support the essential role of testosterone in sustaining spermatogenesis, semen quality, and sperm DNA integrity and highlight the crucial importance of testosterone assessment in the diagnosis and pathophysiological understanding of male infertility.

1. Introduction

Infertility is defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) as the inability to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse [1]. It affects approximately 10–15% of couples, or about 50–80% million people worldwide [2], and the male factors are responsible for about 50% of cases [3]. Thus, it constitutes a significant public health problem [4,5]. There are many factors behind male infertility, including endocrine dysfunctions [5]. Hormones play a crucial role in the development and function of genital organs, the process of spermatogenesis, and the male reproductive system [6]. In particular, testosterone, which seems to be the principal hormone implicated in testicular function, specifically regulates spermatogenesis [7]. Testosterone is produced by Leydig cells after Luteinizing Hormone (LH) stimulation, which occurs in response to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) [6]. In men, the absence or decline of testosterone can affect spermatogenesis, leading to infertility. And low testosterone is implicated in 15% of male infertility [7,8].

In recent years, attention has shifted toward molecular markers of sperm quality, particularly sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) [9], which is commonly assessed with the DNA fragmentation index (DFI). SDF represents single-stranded or double-stranded breaks in the genome of spermatozoa. These breaks can affect male reproductive potential. Several studies confirmed that elevated DFI has been associated with a range of negative reproductive outcomes, including reduced chances of both natural conception and success with assisted reproductive technologies, and is also associated with increased risk of recurrent pregnancy loss [9,10].

Sperm chromatin condensation (SCC) is another crucial determinant of sperm quality. And can be detected indirectly using the aniline blue staining. During spermiogenesis, the histones are replaced with protamines, and the immature chromatin conserves excess histones [11]. Protamines compact nuclear DNA into highly condensed chromatin. This compaction plays a crucial role in protecting the paternal genome during the transit of sperm through the male and female reproductive tracts, as well as during their interaction with the oocyte. Defects in chromatin condensation can lead to nuclear alterations, including SDF or DNA denaturation, which are frequently associated with male infertility [12].

Given the essential role of testosterone and the importance of genomic integrity for male fertility, evaluating the association between testosterone and sperm parameters, DNA fragmentation, and chromatin condensation may help clarify the relationships between testosterone and sperm dysfunction in infertile men.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This was a prospective study, conducted in the reproductive biology laboratory LABOMAC in Casablanca, Morocco. The data was collected from August 2024 to August 2025. The study population included 214 men aged 25–45 years referred to LABOMAC for infertility evaluation. All participants belonged to couples who had been trying to conceive for more than one year without success. Female partners had been clinically evaluated, and no female factor infertility was identified. The men included had no history of chronic disease (such as diabetes, hypertension, or chronic urinary tract infection), varicocele, or inflammation. And the men who had not received hormone therapy (including athletes using testosterone injections), chemo, and radiotherapy. Participants were recruited consecutively during the study period, and all men who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate. The population was divided into two groups according to serum total testosterone levels, using a cutoff value of 2.64 ng/mL, in accordance with the recently published recommendations of the Endocrine Society [13]. Group 0 included men with levels greater than or equal to 2.64 ng/mL, and group 1 included levels less than 2.64 ng/mL. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ibn Rochd University Hospital Center in Casablanca.

2.2. Semen Analysis

Semen samples were collected from participants by masturbation after a period of abstinence of 2–5 days and then liquefied at 37 °C for 30 min in an incubator. Semen analysis was carried out according to the WHO 2021 guidelines [14]. The evaluation included semen volume, sperm concentration, motility, vitality, and morphology.

2.3. DNA Fragmentation Index

DFI was determined using the Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) assay. The principle of this technique was the incorporation of labeled nucleotides into the free ends of 3′DNA fragments in the presence of the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase [15]. Semen samples were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then centrifuged for 10 min. The supernatants were eliminated, and the pellets were smeared onto slides, air-dried, and fixed by immersion in 37 °C formaldehyde prepared in PBS for 30 min. The samples were then rinsed and added to a few drops of permeabilization solution containing Triton X-100, citrate, and distilled water. Then, the samples were incubated at an ambient temperature for 1 min and left to dry. In the dark, the TUNEL reaction mixtures containing fluorescein for in situ cell death detection (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) were applied to the smears. The slides were then covered with a coverslip and then incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. After incubation, the slides were rinsed, and finally, a few drops of glycerol were added. The evaluation was performed under a fluorescence microscope using ×100 objectives under immersion. The DFI was obtained in percentage from the calculated ratio of fluorescent spermatozoa (considered DNA fragmented) to a total of 100 spermatozoa observed per slide. DFI greater than 15% was considered pathological.

2.4. Sperm Decondensation Index

The Sperm Decondensation Index (SDI) was measured using aniline blue staining. The aniline blue binds to lysine residues, which are abundant in histones, thereby staining them [11].

The previously slides sperm smears were stained in aniline blue for 15 min at ambient temperature and then left to dry. The evaluation was performed under a light microscope using ×100 objectives under immersion. The SDI index was obtained in percentage from the calculation of spermatozoa stained dark blue (considered as spermatozoa with immature chromatin) to a total of 100 spermatozoa observed. An SDI index greater than 30% was considered pathological.

2.5. Determinations of Serum Sex Hormones

Testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and LH were analyzed from blood samples provided in the early morning, and then centrifuged to obtain serum. The assay was performed by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) on a Roche Cobas analyzer. The testosterone was measured using the Elecsys Testosterone II kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Sandhofer Strasse 116, D-68305 Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The reference values used for FSH and LH in men were, respectively, from 1.5 to 12.4 UI/L and from 1.7 to 8.6 UI/L.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using R 4.5.2 software. The normality was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, depending on their distribution. The correlation between variables was assessed using the Pearson or Spearman test, depending on their distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristic of the Study Population

The study included 214 men, among whom 135 had normal total testosterone levels (≥2.64 ng/mL), and 79 had low levels (<2.64 ng/mL). Table 1 presents the clinical and hormonal characteristics of the participants, including age, FSH and LH concentrations, and total testosterone according to the groups. The mean age of men in the normal testosterone group (group 0) was 39 ± 4.7 years, whereas the group with low testosterone (group 1) was 41 ± 4. This difference was statistically significant with p = 0.0015. The levels of FSH and LH were also significantly higher in the low testosterone group (9.38 ± 7.3 UI/L and 7.18 ± 4.18 UI/L, respectively), than in those with normal testosterone (5.75 ± 4.5 UI/L and 4.34 ± 3.69 UI/L; p < 0.001 for both). Total testosterone was significantly lower in group 1 than in group 0 (2 ± 0.5 ng/mL vs. 4.66 ± 1.8 ng/mL; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of the study population between the low total testosterone group and the normal total testosterone group.

3.2. Semen Parameters According to Testosterone Levels

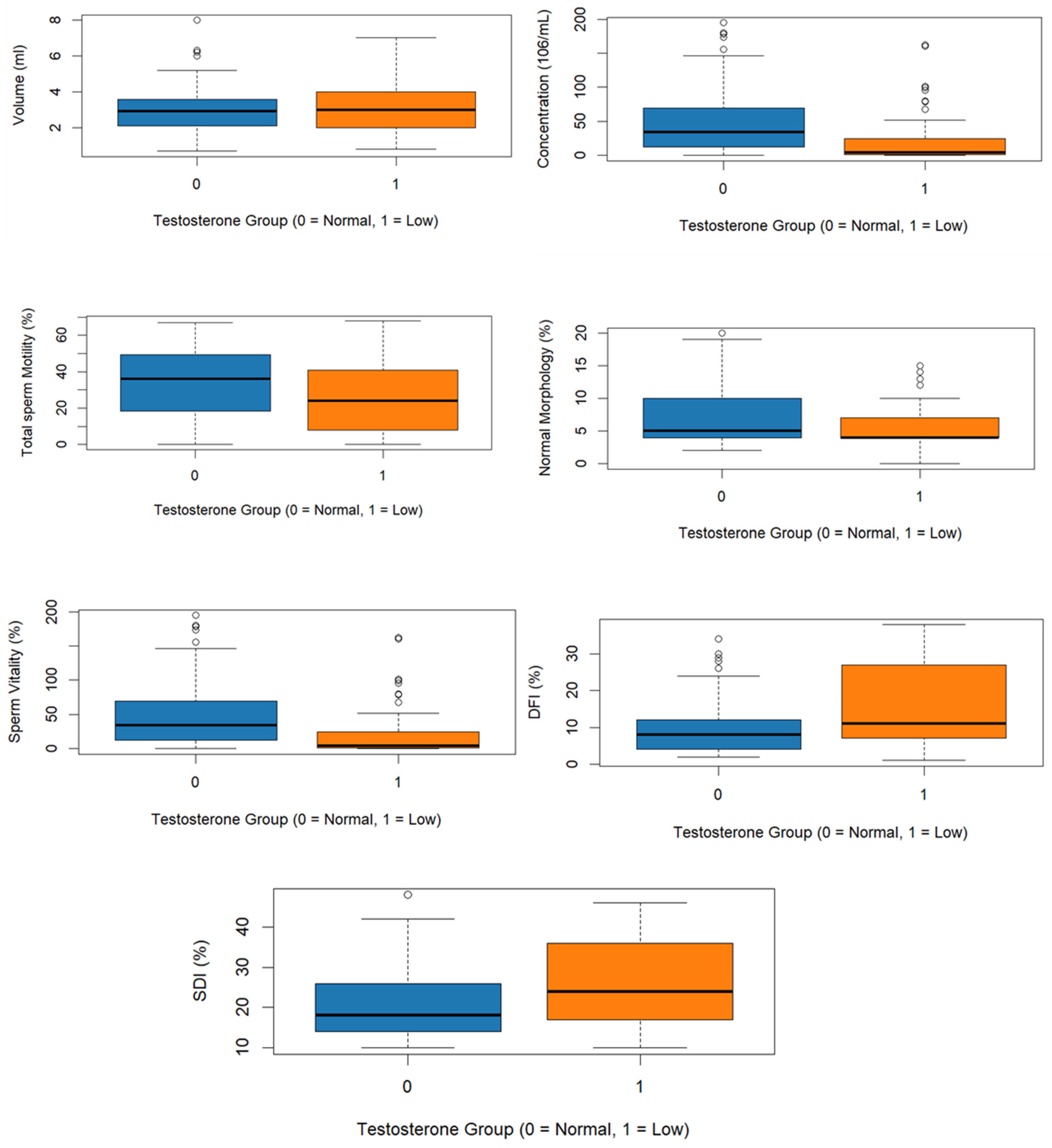

Semen parameters of the two groups are presented in Table 2. The mean semen volume showed no significative difference between the two groups (3.03 ± 1.22 mL vs. 3.10 ± 1.22 mL; p = 0.515); however, sperm concentration was significantly lower in the group of low total testosterone compared to the normal total testosterone group (19.6 ± 33.3 × 106/mL vs. 45.8 ± 43.2 × 106/mL; p < 0.001). Total motility was also reduced in the low testosterone group (26.2 ± 19.9% vs. 33.7 ± 19.3%; p = 0.011). Likewise, normal morphology of spermatozoa (5.78 ± 3.60% vs. 7.69 ± 4.63%; p = 0.003) and vitality (60.2 ± 21.2% vs. 66.4 ± 17.8%; p = 0.024) were significantly lower in men with low total testosterone (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of semen parameters between the low total testosterone group and the normal total testosterone group.

Figure 1.

Boxplots of semen parameter, DFI, and SDI according to testosterone levels.

3.3. DFI and SDI According to Testosterone Levels

The DFI and SDI indices of the two groups are presented in Table 3. DFI and SDI were significantly higher in the low testosterone group (15.93 ± 10.82% and 25.8 ± 10.62%, respectively), than in those with normal testosterone (9.99 ± 7.75% and 20.6 ± 8.52%; p < 0.001, p = 0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of DFI and SDI between the low total testosterone group and the normal total testosterone group.

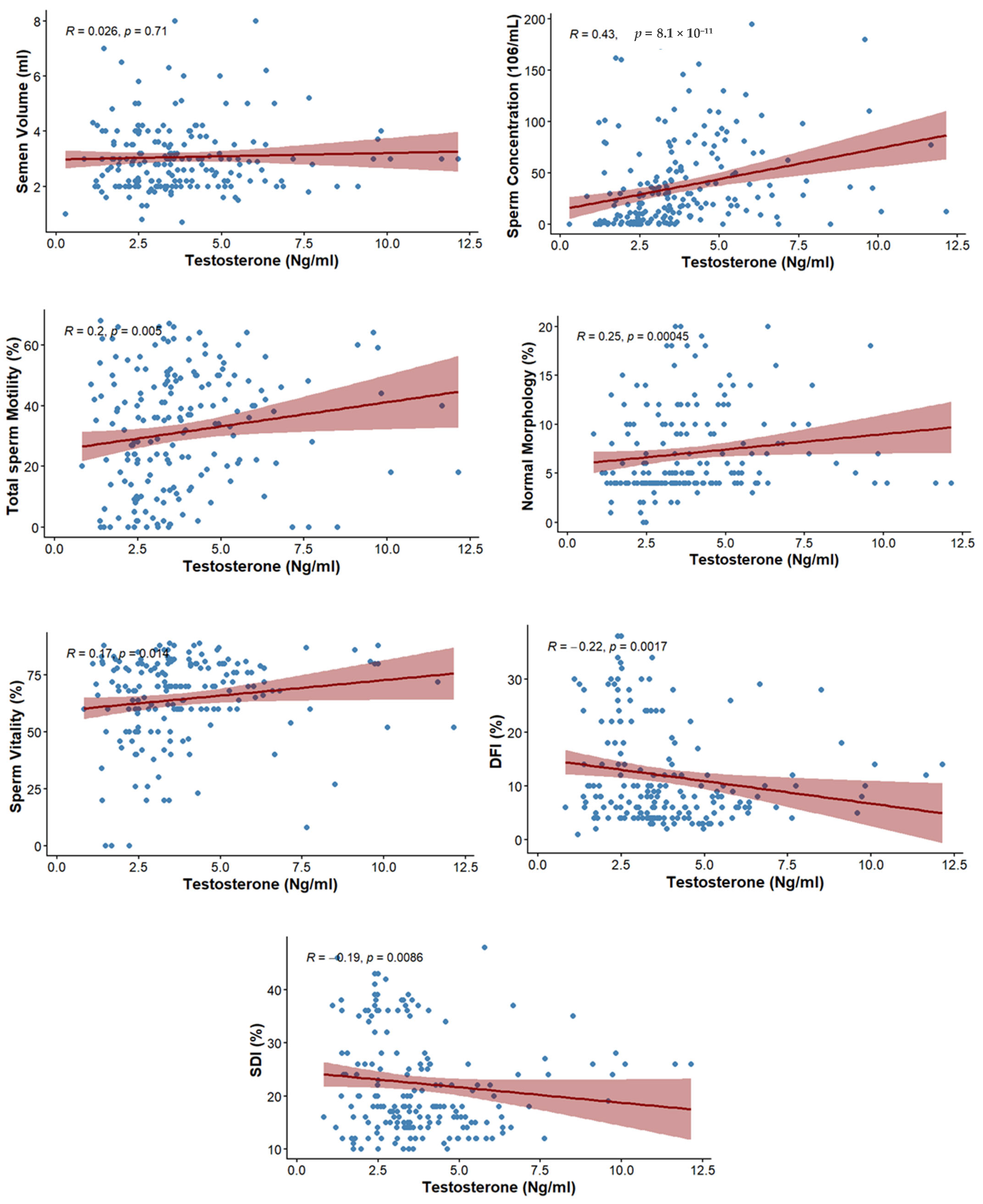

3.4. Correlation Between Testosterone and Semen Parameters

The correlation between testosterone level and semen parameters is presented in Table 4. No significant association was observed with ejaculate volume (rs = 0.026; p = 0.710). However, sperm concentration showed a moderate positive correlation with testosterone (rs = 0.43; p ≤ 0.001). Total motility (rs = 0.2; p = 0.005), normal morphology (rs = 0.25; p ≤ 0.001), and vitality of spermatozoa (rs = 0.173; p = 0.014) also showed positive correlations with testosterone (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) between testosterone and semen parameters.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots depicting the correlations between testosterone levels and sperm parameters, including DFI, SDI, and conventional semen parameters.

3.5. Correlation Between Testosterone and DFI, SDI

The correlation between testosterone level and markers of sperm integrity is presented in Table 5. The level of testosterone was negatively correlated with DFI (rs = −0.221; p = 0.0017) as well as SDI (rs = −0.19; p = 0.0086) (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Spearman’s range correlation coefficient between testosterone, DFI, and SDI.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the association between testosterone and sperm DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and conventional semen parameters. A total of 214 men undergoing infertility evaluation were included. The results of the present study indicate that low testosterone levels are associated with increased DNA damage. Furthermore, reduced testosterone levels are linked to global alteration of sperm quality.

Different international guidelines propose variable thresholds for low total testosterone, and no universal cutoff exists due to variations in clinical objectives, populations, and biological factors. The Endocrine Society recommends a cutoff of 2.64 ng/mL (264 ng/dL), harmonized according to CDC standards for young healthy men, which is particularly relevant for evaluating fertility and semen parameters [13]. The European Association of Urology (EAU) suggests a threshold of 12 nmol/L (~3.5 ng/mL) based on meta-analyses showing that testosterone replacement therapy is generally ineffective above this level, with positive effects more pronounced below 12 nmol/L, especially in men with severe hypogonadism (<8 nmol/L) [16]. The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends 3.0 ng/mL (~10.4 nmol/L), based on clinical symptoms and biochemical evaluation, primarily in older or symptomatic men [17]. We chose the Endocrine Society threshold for this study because it is the most appropriate for assessing the impact of testosterone on semen quality in a prospective study of men evaluated for infertility, and our laboratory assays are certified for this cutoff.

This study confirms the role of testosterone in spermatogenesis through a positive correlation between testosterone and sperm concentration, motility, morphology, and vitality. However, no significant association was found between testosterone and semen volume. Consistent with our findings, Keskin et al. reported no association between testosterone and sperm volume, a significant positive association with motility and progressive motility, and a weakly significant association with sperm morphology [18]. Similarly, Trussell et al. demonstrated that low testosterone levels were associated with abnormal sperm morphology [19]. Rehman et al. also reported that low levels of testosterone were observed in participants with impaired semen parameters compared to normospermic men [20]. In contrast, Guardo et al. reported that low total testosterone was not associated with subnormal sperm parameters in infertile couples [7]. However, the retrospective design of their study, the inclusion of only participants with total sperm counts greater than 5 million, and the use of the 2010 guidelines for semen analysis may partly explain the differences compared to our prospective study. Likewise, Zhao et al. observed an inverse association between total testosterone and sperm motility, and no significant association with sperm concentration and morphology [21].

To our knowledge, few studies have specifically investigated the association between serum testosterone levels and the SDI assessed using aniline blue staining. In this context, the present study found a significant negative correlation between testosterone levels and SDI. These findings are supported by experimental studies, which have shown that supplementation with low doses of testosterone in the sperm culture medium has positive effects on chromatin quality [22]. In addition, we observed a significant negative correlation between testosterone and DFI. These associations suggest that low testosterone levels could be related to an increase in sperm damage. These findings are consistent with a recent study reporting an inverse association between serum testosterone and DFI following FSH administration in men with idiopathic infertility [23]. Our results also partially agree with a study of fertile men, which demonstrated a negative association between free testosterone, estradiol, and DFI [24]. In contrast, Appasamy et al. reported that testosterone was not associated with sperm DNA damage [25].

The heterogeneity observed among some previous studies may be explained by several factors, including differences in study design, population characteristics, and other confounding factors. The prospective design of our study represents a key strength, as semen analyses were performed in the same laboratory in accordance with 2021 WHO guidelines, and the natural diurnal variation in serum testosterone was minimized by collecting blood samples early in the morning. Combined with the evaluation of both conventional semen parameters and advanced markers of sperm integrity, as well as sperm vitality, which has been rarely studied, these methodological approaches may explain the more consistent association observed between testosterone levels and sperm quality in our population. Our results, therefore, add to the evidence and help further clarify this relationship in a North African population that is still poorly documented.

Testosterone acts on Sertoli cells, promoting their proliferation and maturation, which are essential for germ cell development. This process enables the production of mature, intact spermatozoa capable of fertilization. Studies have shown that the absence of androgen signaling results in the arrest of Sertoli cell maturation [26], highlighting the central role of testosterone in maintaining functional spermatogenesis and overall sperm quality. The effect of testosterone is not limited to regulating the intrinsic genomic activity of Sertoli cells but also influences germ cells through paracrine signaling. Testosterone participates in the self-renewal and differentiation of germ cells. Classical and non-classical testosterone signaling, mediated by androgen receptors (AR) in Sertoli cells, is necessary for normal meiosis [26], which allows the production of functional spermatozoa with normal morphology and motility. Moreover, in SCARKO mice, in which the classical signaling pathway is blocked, meiosis arrest occurs at the prophase I [26].

In our study, we observed a negative correlation between serum testosterone levels and sperm DNA fragmentation as well as chromatin decondensation. These findings can be explained by known biological mechanisms. In the absence of AR signaling, germ cells initiate prophase I of meiosis normally and undergo double-strand break formation. However, anomalies arise during the repair of these double-strand breaks and during chromosome synapsis [27,28], leading to chromatin instability. Furthermore, androgen deprivation has been associated with decreased expression of genes encoding protective proteins against oxidative stress, such as Aldh2, Prdx6, and Gstm5, which increases oxidative stress in germ cells [29]. This oxidative stress, in turn, induces DNA fragmentation, compromising the integrity of genetic information and potentially impairing male fertility [30].

A decrease in androgen levels has been associated with increased expression of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase in spermatocytes, which promotes the déubiquitination of the pro-apoptotic p53. Activation of p53 subsequently triggers apoptosis of germ cells, leading to a reduction in sperm production [31]. In addition, testosterone strengthens the adhesion of spermatids to Sertoli cells. When this adhesion is disrupted, spermatids detach prematurely, fail to complete their maturation, and are subsequently phagocytosed by Sertoli cells [26,32,33]. These actions of testosterone indicate the positive association observed in our study between testosterone levels and sperm concentration. Moreover, testosterone indirectly stimulates the production of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase 4 in spermatids. This protein helps regulate intracellular calcium, which is essential for sperm motility at the time of their release [34].

This study has some limitations. The absence of some key parameters, such as SHBG and free testosterone, would have allowed for a more comprehensive endocrine interpretation. Furthermore, Semen parameters vary within the same individual over time, and a single semen sample may not reliably reflect a man’s long-term values.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study reports a significant positive correlation between serum total testosterone levels and conventional semen parameters, including sperm concentration, motility, morphology, and vitality, as well as a significant negative correlation with DNA fragmentation and chromatin decondensation. These results indicate that lower testosterone levels were associated with alterations in semen quality. These findings support the essential role of testosterone in sustaining spermatogenesis, semen quality, and sperm DNA integrity and highlight the crucial importance of testosterone assessment in the diagnosis and pathophysiological understanding of male infertility. Further investigations could evaluate whether correcting testosterone levels in men below the identified threshold could have an impact on sperm DNA integrity, semen parameters, and reproductive outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., K.B. and R.A.; methodology, A.S.; software, S.H. and A.S.; validation, A.S., K.B. and R.A.; formal analysis, S.H. and A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, N.L.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and R.A.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Ibn Rochd University Hospital Center in Casablanca (protocol code: N0 8bis/2024; approval date: 12 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the organizers of the 10th International SMMR Congress for providing the opportunity to present this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| SDF | Sperm DNA Fragmentation |

| DFI | DNA Fragmentation Index |

| SCC | Sperm Chromatin Condensation |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-Nick End Labeling. |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| SDI | Sperm Decondensation Index |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating hormone |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay |

| TT | Total Testosterone |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Median with interquartile range |

| rs | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient |

| AR | Androgen receptors |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| AUA | American Urological Association |

References

- World Health Organization. Infertility. WHO Fact Sheets. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Babakhanzadeh, E.; Nazari, M.; Ghasemifar, S.; Khodadadian, A. Some of the Factors Involved in Male Infertility: A Prospective Review. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Baskaran, S.; Parekh, N.; Cho, C.-L.; Henkel, R.; Vij, S.; Arafa, M.; Selvam, M.K.P.; Shah, R. Male infertility. Lancet 2021, 397, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhussein, O.G.; Ahmed, M.A.; Suliman, S.O.; Yahya, L.I.; Adam, I. Epidemiology of infertility and characteristics of infertile couples requesting assisted reproduction in a low-resource setting in Africa, Sudan. Fertil. Res. Pract. 2019, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Sharma, S.S.; Majumdar, S.S. Etiology of Male Infertility: An Update. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 942–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lin, W.; Wang, Z.; Huang, R.; Xia, H.; Li, Z.; Deng, J.; Ye, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y. Hormone Regulation in Testicular Development and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Guardo, F.; Vloeberghs, V.; Bardhi, E.; Blockeel, C.; Verheyen, G.; Tournaye, H.; Drakopoulos, P. Low Testosterone and Semen Parameters in Male Partners of Infertile Couples Undergoing IVF with a Total Sperm Count Greater than 5 Million. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczewska, D.; Słowikowska-Hilczer, J.; Walczak-Jędrzejowska, R. The Fate of Leydig Cells in Men with Spermatogenic Failure. Life 2022, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinaro, J.A.; Schlegel, P.N. Sperm DNA Damage and Its Relevance in Fertility Treatment: A Review of Recent Literature and Current Practice Guidelines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Farkouh, A.; Parekh, N.; Zini, A.; Arafa, M.; Kandil, H.; Tadros, N.; Busetto, G.M.; Ambar, R.; Parekattil, S.; et al. Sperm DNA Fragmentation: A Critical Assessment of Clinical Practice Guidelines. World J. Men’s Health 2022, 40, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Kang, M.J.; Kim, S.A.; Oh, S.K.; Kim, H.; Ku, S.-Y.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, S.Y.; Choi, Y.M. The utility of sperm DNA damage assay using toluidine blue and aniline blue staining in routine semen analysis. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2013, 40, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, A.; Chakroun, N.; Ben Zarrouk, S.; Sellami, H.; Kebaili, S.; Rebai, T.; Keskes, L. Assessment of chromatin maturity in human spermatozoa: Useful aniline blue assay for routine diagnosis of male infertility. Adv. Urol. 2013, 2013, 578631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasin, S.; Brito, J.P.; Cunningham, G.R.; Hayes, F.J.; Hodis, H.N.; Matsumoto, A.M.; Snyder, P.J.; Swerdloff, R.S.; Wu, F.C.; Yialamas, M.A. Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 1715–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, 6th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli, Y.; Sherman, Y.; Ben-Sasson, S.A. Identification of Programmed Cell Death in Situ via Specific Labeling of Nuclear DNA Fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 1992, 119, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Urology (EAU). EAU Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health; EAU: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2025; Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/sexual-and-reproductive-health (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Mulhall, J.P.; Trost, L.W.; Brannigan, R.E.; Kurtz, E.G.; Redmon, J.B.; Chiles, K.A.; Lightner, D.J.; Miner, M.M.; Murad, M.H.; Nelson, C.J.; et al. Évaluation et prise en charge du déficit en testostérone: Recommandations de l’AUA. J. Urol. 2018, 200, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, M.Z.; Budak, S.; Zeyrek, T.; Çelik, O.; Mertoglu, O.; Yoldas, M.; Ilbey, Y.Ö. The relationship between serum hormone levels (follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, total testosterone) and semen parameters. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2015, 87, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trussell, J.C.; Coward, R.M.; Santoro, N.; Stetter, C.; Kunselman, A.; Diamond, M.P.; Hansen, K.R.; Krawetz, S.A.; Legro, R.S.; Heisenleder, D.; et al. Association Between Testosterone, Semen Parameters and Live Birth in Men with Unexplained Infertility in an Intrauterine Insemination Population. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, R.; Lalani, S.; Baig, M.; Nizami, I.; Rana, Z.; Gazzaz, Z.J. Association Between Vitamin D, Reproductive Hormones and Sperm Parameters in Infertile Male Subjects. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jing, J.; Shao, Y.; Zeng, R.; Wang, C.; Yao, B.; Hang, D. Circulating Sex Hormone Levels in Relation to Male Sperm Quality. BMC Urol. 2020, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, M.; Montazeri, F.; Poodineh, J.; Vatanparast, M.; Koshkaki, E.R.; Esmailabad, S.G.; Mohseni, F.; Talebi, A.R. Therapeutic Potential of Testosterone on Sperm Parameters and Chromatin Status in Fresh and Thawed Normo- and Asthenozoospermic Samples. Rev. Int. Andrología 2023, 21, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lispi, M.; Drakopoulos, P.; Spaggiari, G.; Caprio, F.; Colacurci, N.; Simoni, M.; Santi, D. Testosterone Serum Levels Are Related to Sperm DNA Fragmentation Index Reduction after FSH Administration in Males with Idiopathic Infertility. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richthoff, J.; Spano, M.; Giwercman, Y.L.; Frohm, B.; Jepson, K.; Malm, J.; Elzanaty, S.; Stridsberg, M.; Giwercman, A. The impact of testicular and accessory sex gland function on sperm chromatin integrity as assessed by the sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA). Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 3162–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appasamy, M.; Muttukrishna, S.; Pizzey, A.R.; Ozturk, O.; Groome, N.P.; Serhal, P.; Jauniaux, E. Relationship between male reproductive hormones, sperm DNA damage and markers of oxidative stress in infertility. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2007, 14, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-M.; Li, Z.-F.; Yang, W.-X. What Does Androgen Receptor Signaling Pathway in Sertoli Cells During Normal Spermatogenesis Tell Us? Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 838858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.H. Androgen Actions in the Testis and the Regulation of Spermatogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1288, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-R.; Hao, X.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.-L.; Wang, Z.-P.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Wang, X.-X.; Liu, Y.-X. Androgen receptor in Sertoli cells regulates DNA double-strand break repair and chromosomal synapsis of spermatocytes partially through intercellular EGF-EGFR signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 18722–18735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, P.G.; Sluka, P.; Foo, C.F.H.; Stephens, A.N.; Smith, A.I.; McLachlan, R.I.; O’Donnell, L. Proteomic changes in rat spermatogenesis in response to in vivo androgen manipulation; impact on meiotic cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, H. Mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced sperm dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1520835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, M.L.; Almeida, T.B.; de Santi, F.; Rodrigues, B.M.; Cerri, P.S.; Beltrame, F.L.; Sasso-Cerri, E. Fluoxetine-induced androgenic failure impairs the seminiferous tubules integrity and increases ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1): Possible androgenic control of UCHL1 in germ cell death? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdcraft, R.W.; Braun, R.E. Androgen receptor function is required in Sertoli cells for the terminal differentiation of haploid spermatids. Development 2004, 131, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, A.; O’Donnell, L. Characterization of normal spermiation and spermiation failure induced by hormone suppression in adult rats. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 68, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olli, K.E.; Li, K.; Galileo, D.S.; Martin-DeLeon, P.A. Plasma membrane calcium ATPase 4 (PMCA4) co-ordinates calcium and nitric oxide signaling in regulating murine sperm functional activity. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.