Simple Summary

The Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, is the most extensively cultivated shrimp species worldwide, accounting for over 75% of global production. However, intensive farming practices have frequently led to outbreaks of bacterial diseases, predominantly caused by various pathogenic Vibrio species, resulting in substantial economic losses. Current breeding efforts have largely focused on developing shrimp resistance to individual Vibrio species. Given the high diversity of Vibrio species, resistance to a single Vibrio species is insufficient to address the complex environments of aquaculture. Therefore, breeding shrimp with pan-vibrios resistance (PVR) has emerged as a crucial strategy for achieving sustainable shrimp aquaculture. This study aims to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with PVR traits and pinpoint candidate functional genes using a genome-wide association study (GWAS), with subsequent validation. The results of the study are of great significance for promoting healthy aquaculture development and the sustainable development of marine fishery resources.

Abstract

Vibriosis, caused by diverse Vibrio species, is among the most devastating bacterial diseases in shrimp aquaculture. Consequently, breeding shrimp for pan-vibrios resistance (PVR) presents a crucial strategy for sustainable shrimp farming. In this work, we performed a GWAS in Litopenaeus vannamei to identify genetic loci underlying resistance to pan-vibrios and validate the identified SNPs. A total of 300 shrimp from nine different regions were subjected to a comprehensive challenge. Selective genotyping of 300 resistant and susceptible individuals was conducted using a specific length amplified fragment sequencing (SLAF-seq) approach. A total of 18,184,608 high-quality SNPs were detected across the whole genome of L. vannamei. Screening identified 283 SNPs located within genes, 26 of which were associated with the PVR trait. These SNPs were subsequently validated in verification group of 80 shrimps, leading to the identification of two genotypes (GG at SNP20 and AA at SNP21) and one genotype combination (GG/AA at SNP20 and SNP21) that were significantly associated with the PVR trait. Notably, these linked SNPs were identified in the intron of LvHEATR1 gene. The highest LvHEATR1 expression was observed in immune-related tissues including hemocytes, the gills, and the hepatopancreas. Furthermore, qPCR results showed that LvHEATR1 expression was significantly higher in the vibrios-resistant (RES) group than in the vibrios-susceptible (SUS) group. This study proposed the PVR concept and provided valuable molecular markers for the genetic improvement of vibrios-resistance in L. vannamei.

1. Introduction

Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, is the most widely farmed shrimp species globally, accounting for over 75% of total production [1]. However, with the widespread farming of the shrimp, vibriosis caused by various pathogenic Vibrio species frequently break out, resulting in severe production and economic losses [2,3,4]. Current strategies to control vibriosis primarily rely on antibiotics [2,3], immunostimulants [4,5], and genetic breeding approaches [6,7,8]. Among these, genetic breeding is regarded as the most promising strategy, as it can fundamentally enhance shrimp resistance to Vibrio proliferation through genetic improvement [8].

In recent years, high-throughput sequencing technologies have significantly advanced the genetic breeding of aquatic animals. Molecular-marker-assisted selection (MAS), which mainly depends on mining molecular markers from high-throughput sequencing and data analysis, has been widely applied in several aquatic animals, such as Crassostrea Gigas, Cyprinus carpio, Larimichthys Crocea, and L. vannamei [9,10,11,12]. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) plays an important role in mapping complex traits and in the identification of genetic variants at the genome-wide scale [13]. GWAS has been used to identify important loci for MAS, aiming to enable genetic selection of multiple traits in animals [14]. In genetic breeding of shrimp, for instance, some single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with WSSV resistance [15], growth traits, and sex determination [16] have been identified in Penaeus monodon through GWAS. Medrano-Mendoza et al. [17] first analyzed the correlation between the WSSV resistance trait and SNPs in L. vannamei using GWAS. Liu et al. [10] identified seven genes related to ammonia nitrogen tolerance in L. vannamei using GWAS. Whankaew et al. [18] identified four SNPs and 17 InDels in three varieties of L. vannamei related to the tolerance to Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND). However, to date, no further screening and validation of candidate SNPs identified by the GWAS for the vibrios-resistance in shrimp has been conducted. In addition, nearly all SNPs associated with vibrios-resistance in shrimp were identified to target the genetic improvement of AHPND tolerance, wherein only specific virulent strains of Vibrio species (such as V. parahaemolyticus) were adopted [7,8,19]. Vibrio is a genus of ubiquitous bacteria found in a wide variety of aquatic and marine habitats, and at least 140 species have been recorded in this genus https://www.bacterio.net/genus/vibrio (accessed on 10 January 2026), among which more than 16 Vibrio species have been reported as opportunistic pathogens in shrimp [20]. Due to the prevalence of pathogenic Vibrio species in diverse marine environments, genetic breeding of shrimp with the pan-vibrios resistance (PVR) trait (i.e., resistance to wide range of Vibrio pathogens) has more practical significance for successful shrimp farming.

In the present study, a GWAS of the PVR trait was performed in 300 shrimp from different sources. SNPs associated with PVR were identified, providing insights into L. vannamei resistance to pan-vibrios. Genotypes of these candidate SNPs were differentiated in a validation group and their association with the PVR trait was analyzed. Finally, a genotype combination in LvHEATR1 that was strongly associated with the PVR trait was identified. This study proposes the concept of the PVR trait and provides valuable molecular markers for genetic selection in L. vannamei, facilitating the breeding for improved vibrios-resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Shrimp Sample Collection

In this study, 510 shrimps were divided into two populations: the experimental population and the verification population. The experimental population consisted of 300 shrimps (weight 11 ± 4 g), which were collected from 9 regions in China (Sanya, Qionghai, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningde, Zhanjiang, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Guangzhou). The verification population consisted of 240 shrimps collected from 4 farms in Maoming, China. The two populations were separately raised in two identical ponds in Maoming, China, with the ponds filled with 10 tons of natural seawater (25 parts per thousand, pH 8.1), and the seawater temperature was maintained at 27 °C ± 2 °C, under a 12 h dark–12 h light photoperiod. The shrimps were fed twice a day, in the morning and afternoon, with commercial feed (HengXing, Zhanjiang, China). The load of vibrios in the water was confirmed by a TCBS test to be 103 CFU/L, and this setup ensured sufficient contact between the shrimps and the widely existing bacteria. One week after the cultivation, samples of the shrimps were collected for experiments. The surface of the shrimp was rinsed with deionized water and wiped with 75% alcohol to prevent bacterial infection. Then, the carapace was removed, and the liver and pancreas surface was lifted using sterilized forceps to collect the internal tissues of the shrimps. A total of 0.1 g of these tissues was placed in an EP tube for TCBS testing, while the remaining parts were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent DNA extraction.

2.2. Evaluation of the PVR Trait by the Load of Vibrios in Hepatopancreas

To classify the PVR levels in shrimp, the load of vibrios in the hepatopancreas was quantified using Thiosulfate Citrate Bile Salts Sucrose (TCBS) agar, and the resistance levels were categorized based on the load of vibrios. A total of 0.1 g of hepatopancreas tissue was placed into the EP tube and homogenized with 1 mL of sterile seawater. The hepatopancreas homogenate was then subjected to a 10-fold serial dilution. A total of 100 μL of hepatopancreas homogenate from the 1×, 10×, and 100× dilutions were spread evenly onto TCBS plates. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, after which the colony-forming units (CFUs) were enumerated. Shrimp individuals were classified into five grades (G1, G2, G3, G4, and G5) according to the load of vibrios to reflect their PVR trait, among which the severity of Vibrio proliferation progressively escalates from grade 1 to grade 5 (G1 to G5). Finally, for the validation group, a total of 80 resistant individuals (G1) and susceptible individuals (G4 and G5) were selected from the 240 shrimp based on their hepatopancreas the load of vibrios levels.

2.3. DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

The genomic DNA of each shrimp sample was extracted using the Marine Animals Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). All 300 shrimp from nine regions in the experimental population were used for GWAS detection. SLAF-seq sequencing was conducted, strictly according to the methods described in reference [21]. The sequencing platform adopted was Illunima Hiseq 2500 (Illunima, San Diego, CA, USA), and the average sequencing depth was 11.04×.

2.4. Genotyping and Quality Control

Filtered reads were mapped to the reference genome of L. vannamei (ASM 378908) using BWA software v0.7.19 [22]. GATK v4.2 [23] and SAMtools v1.19.2 [24] were used to develop the SNP tag intersection as the final reliable SNP tag dataset. Subsequently, SnpEff software v5.0 [25] was used to analyze the mutation sites and gene information in the reference genome. The “check marker” function in the GenABEL package was used for quality control of genotyping SNPs in an R environment [26]. The SNPs were identified as having a minor allele frequencies (MAF) > 0.05, Max-missing < 0.2, or Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium < 1 × 10−6. In addition, SNPs located within genes were focused on. Then, genome-wide significance was assessed by the Bonferroni method, in which the conventional p value was divided by the number of tests performed (SNPs tested).

2.5. Variant Calling Analysis and GWAS

Combined with EMMAX [27], the following mixed linear model was used for correlation analysis:

where y represents phenotypic data, W is the population structure variable, x is the genotype data, α and β are the effect values corresponding to W and x, and e is the residual. According to the p-value of the SNP, with −log10 (p) ≥ 2 as the significance standard, the corresponding Q–Q quantile map and Manhattan map were drawn by using the R qqman package v0.1.9 (https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.qqman).

2.6. Function Analysis of Genes Containing Discrepant SNPs and Genotyping of Discrepant SNPs in the Validation Group

Genes containing discrepant SNPs identified by the GWAS were screened based on SNP locations using the genomic information of L. vannamei (ASM 378908v1; the genome used is not the latest reference genome), and gene functions were annotated using the NCBI-NR database. The tag sequence information for the selected genes was obtained from the L. vannamei genome. Primer premier 6.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Norcross, GA, USA) was used to design primers for PCR, targeting DNA fragments near the candidate SNP. Two forward primers were designed for each site, and fluorescent sequence tags FAM (GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCT) and HEX (GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATT) were added. All primers used in this study were designed by Primer premier 6.0 software and are listed in Table S1. Genotyping was performed using competitive allele specific PCR (KASP) with a commercial STO Rox kit (Gudebio, Guangzhou, China).

2.7. Correlation Analysis Between Genotypes and the Performance of the PVR Trait in the Validation Group

The load of vibrios of 240 shrimp from the Maoming farm was detected using TCBS plates. Among them, a total of 80 shrimp with the load of vibrios belonging to G1 were classified as the vibrios-resistant (RES) group, while G4 and G5 were classified as the vibrios-susceptible (SUS) group. These shrimps will be used to validate the candidate SNPs. The association between SNPs and trait was identified by SPSS 27 software https://www.ibm.com/cn-zh/products/spss (accessed on 15 August 2025). Among them, SNP loci with p < 0.05 were considered to be significantly associated with the trait of PVR and the association between the genotypes of these SNPs and the load of vibrios was examined. SNPs significantly associated with the PVR trait were further used to explore potential interactions among them using linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis and Haploview software v4.2 [28]. Based on the LD analysis, the correlation between the genotype combination and the PVR trait performance was also analyzed, leading to the identification of combined SNP markers.

2.8. Protein Structure Prediction of a Target Gene Related to the PVR Trait and Expression Levels of the Gene

The SWISS-MODEL website https://swissmodel.expasy.org/ (accessed on 26 August 2025) was used to predict the 3D structure of the protein coded by a target gene related to the PVR trait. Total RNA was extracted using an RNA Easy Fast Tissue/Cell Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) and was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a Prime Script™II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The expression levels of the gene in the brain, eye stalk, hemocytes, gill, hepatopancreas, heart, muscle, intestine and stomach were detected by qRT-PCR using a RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) and the β-actin gene was used as the reference gene (Table S1). qRT-PCR was performed using Thermal Cycler Dice®Real Time System III (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 56 °C for 30 s, reading of templates at 95 °C for 15 s, and a final melting curve from 60 to 95 °C. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were used for qRT-PCR, and gene expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method [29].

2.9. Prediction of Splicing Sites

NetGene2 v2.42 https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/ (accessed on 28 July 2025) was used to predict SNP loci in intronic sequences and splicing sites (confidence ≥ 0.80).

3. Results

3.1. Grading the PVR Trait of the Shrimp Individuals

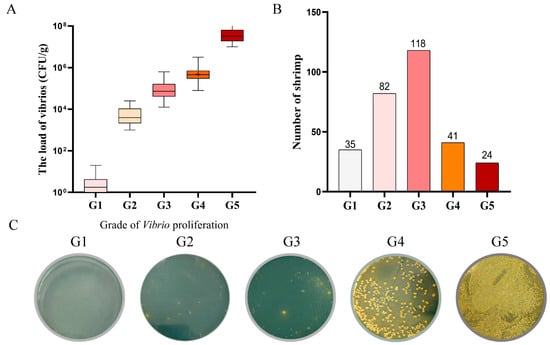

According to the load of vibrios in the hepatopancreas, the PVR trait of the shrimp was quantified to five grades, G1 to G5 (Figure 1A). Among 300 shrimp, only 25 individuals in G1 (8.3%) exhibited significant PVR traits, while 32 individuals in G5 (10.7%) exhibited extensive proliferation in hepatopancreas, weakly indicating the PVR trait performance (Figure 1B). The typical bacterial colonies of different proliferation grades on the TCBS plates are shown in Figure 1C.

Figure 1.

The load of vibrios corresponding to different proliferation grades. (A) The load of vibrios corresponding to different proliferation grades in the test group. (B) Number of individuals in each proliferation grade. (C) Representative bacterial colonies on TCBS plates for each proliferation grade.

3.2. GWAS and Gene Functional Annotation of the Candidate SNPs

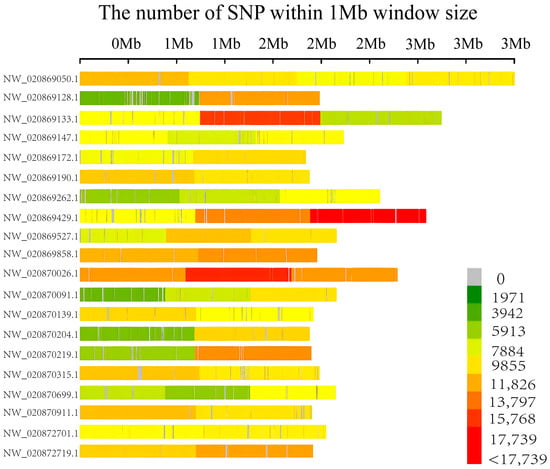

According to the comparison analysis, 18,184,608 SNP loci were identified, 78.78% were located in intergenic regions, whereas only 5.95% were located within genes. Moreover, these SNPs were unevenly distributed across the genome, with the highest densities on scaffolds, NW_020869133.1, NW_020869429.1, and NW_020870026.1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of SNPs across the chromosomes on the 20 longest scaffolds in L. vannamei. The color bar indicates the number of SNPs within 0.1 Mb window, with the index shown on the right.

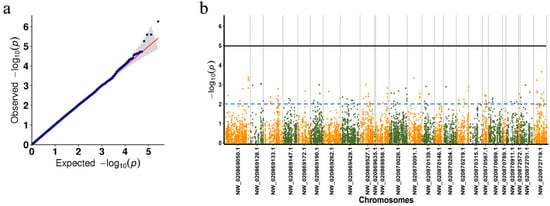

The Q–Q plot indicated that the test statistics were well controlled after effective correction for family structure, indicating the phenotypic data fit the selected model well (Figure 3a). The Manhattan plot showed the GWAS results, with a total of 1939 SNPs above the dotted significance threshold (−log10 (p) ≥ 2, Figure 3b). After focusing on SNPs inside genes (distance < 1), a total of 283 SNPs potentially related to the PVR trait were identified. These genes encompassed a variety of gene functions, including immune regulation, metabolism, cell cycle, and signal transduction (Table S2). We selected 10 immune-related genes, including a total of 26 SNPs for validation (Table 1). These genes included Toll pathway signal transducers, immune recognition receptors, caspases, protease inhibitors, and chitinases.

Figure 3.

GWAS for the shrimp PVR trait. (a) Q–Q plot and (b) Manhattan plot. The dashed blue line and solid black line indicate −log10(p) = 2 and −log10(p) = 5, respectively. Since the genome of L. vannamei is not assembled at the chromosomal level, in this study, only SNP distributions on the 20 longest scaffolds are visualized.

Table 1.

Statistics of the SNPs associated with the PVR trait.

3.3. Genotyping of the SNPs and Validation of the Candidate SNPs and Genotypes in the Validation Group

The load of vibrios within the 240 shrimp collected from Maoming was determined using TCBS agar plates. Based on the results, RES (G1, n = 26) and SUS (G4 and G5, n = 54) individuals were selected to form a validation group for genotyping 26 candidate immune-related SNPs. The genotypes of these SNPs were statistically analyzed to identify those exhibiting significant differences between the RES and SUS groups. A total of five SNPs (SNP1, SNP6, SNP20, SNP21, SNP22) showed significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05). Although the genotype profiles of SNP1 and SNP6 showed a significant difference between the two groups, no valuable genotypes were found to be associated with the PVR trait. The GG genotype of SNP20, the AA genotype of SNP21, and the TT genotype of SNP22 were more frequent in the RES group (Table 2). However, the AA genotype of SNP1 (64.0% in the SUS group) and the AA genotype of SNP6 (85.7% in the SUS group) showed a significant correlation with pan-vibrios susceptible (PVS) traits. Consequently, SNP1 and SNP6 cannot be regarded as reliable molecular markers for the PVR trait and were more likely associated with the PVS trait.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of SNPs associated with the PVR trait in the verification group.

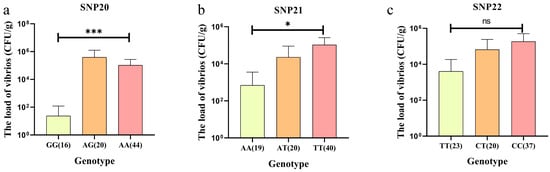

As a result, these three SNPs were selected as candidate loci for subsequent validation. Statistical analysis of the correlations between the genotype of the three SNPs and the load of vibrios showed that only the genotype of SNP20 and SNP21 had significant differences in the load of vibrios. The GG genotype of SNP20 (<102 CFU/g) and AA genotype of SNP21 (<103 CFU/g) had the lowest load of vibrios and were significantly different from other genotypes (p < 0.05, Figure 4a,b), indicating that the GG genotype of SNP20 and the AA genotype of SNP21 are significantly associated with the PVR trait. Although no statistically significant association was observed between SNP22 genotypes and the load of vibrios, individuals carrying the TT genotype of SNP22 exhibited lower the load of vibrios compared to other genotypes (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

The correlation between genotypes of the three SNPs and the load of vibrios in the validation group. (a) the association between SNP20 genotype and the load of vibrios. (b) the association between SNP21 genotype and the load of vibrios. (c) association between SNP22 genotype and the load of vibrios. Data were analyzed using ANOVA, where * indicates p < 0.05 and *** indicates p < 0.001. “ns” indicates no significant difference between groups. The numbers in parentheses after the genotypes represent the number of individuals with that genotype.

3.4. Haplotypes of the SNPs and Correlation Analysis Between the Haplotypes and PVR Trait

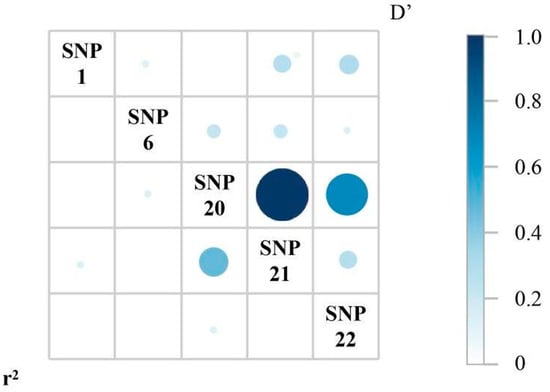

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis was performed on the five SNPs. The results showed strong linkage disequilibrium between SNP20 and SNP21 (Figure 5), and significant differences in the GA and AT haplotypes of SNP20 and SNP21 between the RES and SUS groups. Specifically, the GA haplotype was more prevalent in the RES group (72.7%), whereas the AT haplotype was more common in the SUS group (86.6%, Table 3).

Figure 5.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis of the five SNPs. Pairwise LD is shown as a matrix. The circle in the lower left matrix represents the r2 value, and the circle in the upper right matrix indicates the D’ value (as shown by the color scale on the right).

Table 3.

The load of vibrios associated with different combination genotypes in the validation group (n = 80).

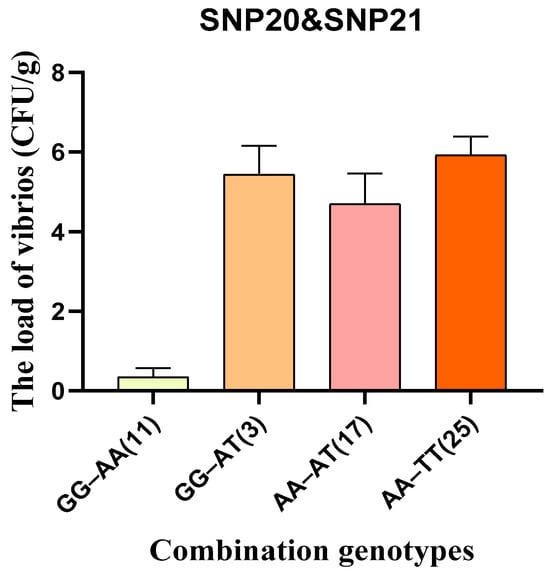

Statistical analysis of the load of vibrios showed that individuals with the GA haplotype had a significantly lower the load of vibrios than those with the AT haplotype. In addition, to enhance the development of molecular markers, GA haplotypes and AT haplotypes were further classified into four genotype combinations, GG/AA, GG/AT, AA/TT and AA/AT (Figure 6). Among these, individuals with the GG/AA genotype combination (derived from the GA haplotype) exhibited the lowest the load of vibrios, while those with the AA/TT combination (derived from the AT haplotype) showed the highest. Using homozygous genotypes may help reduce trait segregation during breeding.

Figure 6.

The correlation between combination genotypes of SNP20 and SNP21 and the load of vibrios in the validation group. The numbers in brackets indicate the number of individuals with the combined genotype.

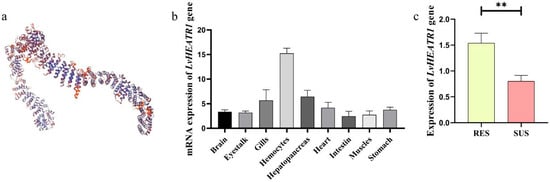

3.5. Structure Prediction and Tissue Distribution of the Gene Harboring the Three SNPs

The three SNPs (SNP20, SNP21, SNP22) were located in intronic region of LvHEATR1, which encodes for a collagen triple helix repeat containing protein 1. The 3D protein structure prediction showed that it contains many repeated alpha helices, accounting for about 70.64% of the gene (Figure 7a), which may be closely related to its function. The expression level of LvHEATR1 was relatively high in hemocytes, the hepatopancreas, and the gills (Figure 7b), and expression was highest in hemocytes (approximately fivefold higher than in muscle). Moreover, LvHEATR1 expression was significantly higher in the RES group than in the SUS group, suggesting a potential association between LvHEATR1 and the PVR trait in L. vannamei (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Analysis of the LvHEATR1 gene function. (a) the 3D structure of protein encoded by the gene LvHEATR1 (b) the expression distribution of LvHEATR1. (c) mRNA expression of LvHEATR1 gene in the RES and the SUS group. “**” indicates that this gene shows a significant difference between the RES group and the SUS group (p < 0.01).

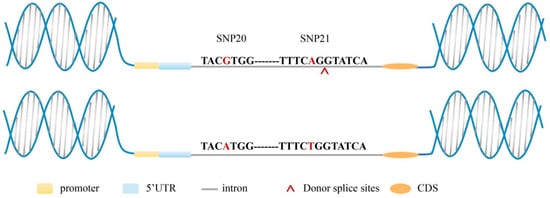

3.6. Variations in SNPs Changed the Position of Predicted Splice Sites

A total of six splice sites were identified, comprising four splicing donor sites and two splicing acceptor sites. Notably, the GG/AA genotype combination of SNP20 and SNP21 contained one additional recognizable donor splice site compared to the AA/TT genotype combination (Table 4), which is predicted to generate a novel transcript and consequently affect protein structure and function. This splicing donor site is located behind SNP21 and close to SNP21 (Figure 8).

Table 4.

Prediction of splicing sites in the intron region of the LvHEATR1 gene.

Figure 8.

Prediction of the altered splicing site in the genotype combination. The bases with red color are SNP20 and SNP21. The gene sequence above represents the GG/AA combined genotype, and the gene sequence below represents the AA/TT combined genotype. Donor splicing sites that were identified in the region between SNP20 and SNP21 of GG/AA.

4. Discussion

Vibrio, as a common aquatic bacteria, have caused serious harm and great economic losses in shrimp culture [30,31]. There is a high diversity and ubiquity of Vibrio species in estuarine and marine environments [32,33], and Vibrio is classified as opportunistic and conditionally pathogenic bacteria; for instance, an increase in temperature can damage the metabolic pathways and adaptability of Vibrio harveyi, where the expression of virulence genes is upregulated [34]. Therefore, shrimps with a higher colonization rate are more likely to be infected by vibrios and suffer from related diseases. Given these conditions, the concept of PVR was proposed; these shrimps can resist a wide range of Vibrio, including both pathogenic and non-pathogenic Vibrio, in the aquaculture environment. The objective is to identify and select shrimp capable of resisting a broad spectrum of vibrios proliferation, thereby reducing the risk of vibrios diseases in shrimp aquaculture. Likewise, it is likely that breeding materials of shrimp screened through the infection challenge by single or multiple Vibrio species may not be capable of adapting to the complicated farming environments full of various vibrios [35,36]. Based on this consideration, we were inclined to obtain ideal breeding materials for shrimp from actual farming environments instead of the infection challenge by specific Vibrio species.

In this study, the shrimp were continuously exposed to a diverse range of vibrios conditions throughout their growth period, which indicates that they have taken up the challenge of mixed strains of vibrios. By farming the shrimp in seawater containing Vibrio, it is ensured that all individuals are adequately exposed to the Vibrio, including pathogenic and non-pathogenic Vibrio, thereby avoiding false-resistant shrimp. The hepatopancreas of shrimp is not only a digestive organ but also an immune organ of shrimp that is frequently invaded by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Diversified vibrios can easily be found in the farmed shrimp, L. vannamei. In long practices of farming and pathological examinations, we found that the load of vibrios in the hepatopancreas can reflect the healthy state and resistance ability of the shrimp, and similar findings have also been reported by other researchers [36,37]. For another parasite pathogen, Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP), EHP load in the hepatopancreas of L. vannamei also reflects the resistance ability of the shrimp [38,39,40]. In this study, we used TCBS plating to calculate the load of vibrios in hepatopancreas of shrimps. It is well known that some other bacteria such as Photobacterium and Pseudoalteromonas species can also grow on the TCBS plates [41,42]. However, TCBS plating are still used as the conventional method to calculate the number of vibrios in laboratory and farming practices [43,44,45] as this method is very convenient and vibrios can form dominant colonies within overnight culture (less than 24 h). In addition, viable-but-non-culturable (VBNC) state is another issue that may affect the calculation of vibrios. VBNC state is a self-protection mechanism of some bacteria such as vibrios [46,47]. Under natural conditions, bacteria enter VBNC due to a decrease in temperature or a lack of nutritional environment [48,49]. However, during shrimp farming and TCBS cultivation, we ensured that vibrios had suitable temperatures and sufficient nutrients and all the hepatopancreas samples were treated under the same conditions. Therefore, even though some vibrios may have entered a VBNC state, it does not affect the final evaluation of the PVR trait measured by the load of vibrios. Based on these reasons, in this study, the load of vibrios in the hepatopancreas of L. vannamei can be determined by TCBS plating, thereby quantifying the PVR trait, and the subsequent screening of the final resistance SNP markers can be linked to the performance of the PVR trait.

The shrimp individuals with strong PVR traits were approximately 10% in the test group and the validation group, which indicates that only a few individuals in a shrimp group have strong resistance to Vibrio proliferation, likely conferred by the genetic variations in these individuals. This explains the relatively small number of G1 individuals in the shrimp population used in the experiment, and this result is consistent with natural principles.

GWAS is a powerful tool for association analysis between genotypes and phenotypes without breeding information. It plays a significant role in the screening of resistance to vibrios in aquatic animals. Currently, 18 SNP loci associated with resistance to vibrios in oysters have been identified [50], and seven SNPs linked to resistance against Vibrio harveyi in yellow croaker have also been reported [51,52]. Additionally, four SNPs related to vibrios-resistance have been identified in shrimp. However, at present, this resistance screening is restricted to specific pathogenic Vibrio species and has not been further validated for SNPs. In this study, whole genomes of 300 shrimp containing five different PVR levels (G1 to G5) were sequenced for GWAS. Through GWAS, 26 SNPs were first screened out, and these SNPs were annotated to the genes related to Toll pathway signal transducers, immune recognition receptors, caspases, protease inhibitors, and chitinases. After KASP genotyping, three SNPs (SNP20, SNP21, SNP22) were further screened out to be likely associated with the PVR trait and two SNPs (SNP1, SNP6) were associated with PVS traits and do not have breeding value. Validation of the association between genotype and the load of vibrios confirmed that the GG genotype of SNP20 and the AA genotype of SNP21 are significantly associated with the PVR trait, thereby providing support for molecular marker breeding.

In addition, LD analysis is an important method to examine SNP–SNP interaction, which has been shown to play an important role in the selection of species for complex traits [40,41,42]. Furthermore, both SNPs located in the intron region of the LvHEATR1 gene also supported the LD of the two SNPs, which propelled the potential genotype combination that is closely associated with the PVR trait. The application of combined molecular markers narrows the screening range and increases the accuracy of breeding materials [28], which also theoretically matches the rule that most economic traits are controlled by a set of loci in a genome [53,54]. LvHEATR1 is one kind of HEAT repeat protein, which includes a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) protein, owning a common function of mediating protein–protein interactions [55]. mTOR plays an important role in various cellular activities, such as immunity, and it is activated by the formation of polymers in mammalian cells through its N-terminal HEAT repeat region [56]. In addition, a HEAT repeat protein, ILITYHIA (ILA) in Arabidopsis, involved in the plant immune process, and the mutation of ILA, leads to increased sensitivity to pathogens and systemic drug resistance defects in plants [57]. In addition, the mTOR proteins of crustaceans, such as Gecarcinus lateralis and Carcinus maenas, also contain the HEAT repeat structure [58]. The genes involved in the mTOR pathway of L. vannamei are strongly associated with the bacterial resistance phenotype exhibited by these crabs [59,60]. The expression distribution of LvHEATR1 in the shrimp showed that the mRNA was highly expressed in immune-related tissues such as hemocytes, the gill, and the hepatopancreas, which are also frequently attacked by vibrios. The RES group exhibited significantly higher expression levels of the LvHEATR1 gene compared to the SUS group, suggesting a potential association between this gene and the PVR trait in shrimp. Therefore, it can be speculated that LvHEATR1 may play a crucial role in the immune process of L. vannamei, although the specific function of HEAT repeat proteins in shrimp has not been elucidated.

Generally, introns can’t be transcribed into mRNA, and they are often considered as junk DNA regions [61]. However, recent studies have shown that introns are closely related to gene expression and cytoskeleton construction and exert some influence on life activities [62,63]. InDels within introns in different cattle groups are extremely enriched in immune-related pathways [64]. Changes in body weight due to the SNPs in an intron of the RuvBL2 gene have also been found in shrimp [65]. SNPs in introns can also lead to the occurrence of different spliceosomes sourced from the same gene [62,66,67]. In this study, the SNP loci result in alterations to the splicing donor site. Compared to the GG/AA combined genotype, the AA/TT genotype lacks a donor splice site. Based on this established correlation between the combination genotype and splice site alteration, we hypothesize that the loss of this splice site may lead to the production of a novel, nonsensical transcript during RNA processing. As a result, this novel transcript fails to produce a functional protein, ultimately contributing to the stronger PVR trait observed in GG/AA individuals compared to individuals with AA combination genotype. It is also possible that the donor splice site is important for shielding unspliced transcripts from degradation [68]. Consequently, its absence may lead to nonsense-mediated decay, thereby reducing LvHEATR1 gene expression levels in the SUS group compared to the RES group. However, the precise splicing pattern and sequence of this putative novel transcript remain unclear. The existence of this transcript and its functional impact require further experimental validation.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the correlation between SNPs and the PVR trait of L. vannamei was analyzed. A total of 26 SNPs potentially associated with the PVR trait were initially identified using GWAS. Association analysis between genotype and the load of vibrios revealed a significant link between the PVR trait and the GG genotype of SNP20 and AA genotype of SNP21. The genotype combination of GG/AA of the SNP20 and SNP21 was significantly associated with the strongest performance of the PVR trait, and these SNPs were found to be located in the intron region of a gene, LvHEATR1. This study provides valuable molecular markers for the genetic selection of the PVR trait in shrimp, L. vannamei.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology15030208/s1, Table S1: Primers used in this study (DOCX) and Table S2: Candidate SNPs located within genes related to the traits of PVR (XLSX).

Author Contributions

S.W.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, and writing—original draft; C.C.: funding acquisition; methodology, and software; J.Y.: visualization and writing—review and editing; Y.L. (Ying Lv): project administration and supervision; X.Z.: project administration and visualization; B.M.: methodology; Y.L. (Yang Liu): data curation and validation; Y.Q.: visualization; H.H.: visualization and methodology; P.L.: investigation, writing—review and editing, resources, and supervision; L.Y.: project administration, funding acquisition, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation project, grant number 2023GXNSFBA026356, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2023YFD2401701, the Seed Industry Revitalization Project of Provincial Rural Revitalization Strategy Special Funds, grant number 2022-SPY-00-001, the Research on breeding technology of candidate species for Guangdong modern marine ranching, grant number 2024-MRB-00-001, and the Innovation Team Project of Guangdong Universities, grant number 2022KCXTD017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All shrimp experiments in the present study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Research and Ethics Committees of the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology (SCSIO-2024-012), Chinese Academy of Sciences, approved on 24 April 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GWAS | genome-wide association study |

| SNP | single nucleotide polymorphism |

| PVR | pan-vibrios resistance |

| PVS | pan-vibrios susceptible |

| LD | linkage disequilibrium |

| G1 to G5 | grade 1 to grade 5 |

References

- Pedrazzani, A.S.; Cozer, N.; Quintiliano, M.H.; Ostrensky, A. Insights into Decapod Sentience: Applying the General Welfare Index (GWI) for Whiteleg Shrimp (Penaeus vannamei—Boone, 1931) Reared in Aquaculture Grow-out Ponds. Fishes 2024, 9, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalin, N.; Srinivasan, P. Molecular characterization of antibiotic resistant Vibrio harveyi isolated from shrimp aquaculture environment in the south east coast of India. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 97, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Xiong, J. Responses of Sediment Resistome, Virulence Factors and Potential Pathogens to Decades of Antibiotics Pollution in a Shrimp Aquafarm. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Sim, S.S.; Chiew, S.L.; Yeh, S.-T.; Liou, C.-H.; Chen, J.-C. Dietary Administration of a Gracilaria tenuistipitata Extract Produces Protective Immunity of White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei in Response to Ammonia Stress. Aquaculture 2012, 370–371, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Tan, H.-C.; Cheng, W. Effects of Dietary Administration of Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) Extracts on the Immune Responses and Disease Resistance of Giant Freshwater Prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Liu, B. Identification of a Serum Amyloid A Gene and the Association of SNPs with Vibrio-Resistance and Growth Traits in the Clam Meretrix Meretrix. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 43, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongchum, P.; Chimtong, S.; Prapaiwong, N. Association between Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of nLvALF1 and PEN2-1 Genes and Resistance to Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 7, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.-S.; Chen, X.-L.; Wang, A.-J.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Peng, M.; Yang, C.-L.; Zeng, D.-G.; Zhao, Y.-Z.; Wang, H.-L. Identification, Functional Analysis of Chitin-Binding Proteins and the Association of Its Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Vibrio parahaemolyticus Resistance in Penaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 154, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, P.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z. Whole-Genome Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Marker Discovery and Association Analysis with the Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Content in Larimichthys crocea. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Liu, J. Genome-Wide Association Study Identified Genes Associated with Ammonia Nitrogen Tolerance in Litopenaeus vannamei. Front. Genet. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, Q. Whole-Genome Resequencing Identifies Candidate Genes and SNPs in Genomic Regions Associated with Shell Color Selection in the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture 2024, 586, 740768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Kuang, Y.; Lv, W.; Cao, D.; Sun, Z.; Sun, X. Genome-Wide Association Study for Muscle Fat Content and Abdominal Fat Traits in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0169127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M.; Brown, M.A.; McCarthy, M.I.; Yang, J. Five Years of GWAS Discovery. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Guo, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Zou, Q. An Overview of SNP Interactions in Genome-Wide Association Studies. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2015, 14, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.A.; Gopikrishna, G.; Baranski, M.; Katneni, V.K.; Shekhar, M.S.; Shanmugakarthik, J.; Jothivel, S.; Gopal, C.; Ravichandran, P.; Gitterle, T.; et al. QTL for White Spot Syndrome Virus Resistance and the Sex-Determining Locus in the Indian Black Tiger Shrimp (Penaeus monodon). BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.-H.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, F.-L.; Huang, J.-H.; Liu, B.-S.; Jiang, S.-G.; Zhang, D.-C. A High-Density Genetic Linkage Map and QTL Mapping for Sex in Black Tiger Shrimp (Penaeus monodon). Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrano-Mendoza, T.; García, B.F.; Caballero-Zamora, A.; Yáñez, J.M.; Campos-Montes, G.R. Genetic Diversity, Population Structure, Linkage Disequilibrium and GWAS for Resistance to WSSV in Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Using a 50K SNP Chip. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whankaew, S.; Suksri, P.; Sinprasertporn, A.; Thawonsuwan, J.; Sathapondecha, P. Development of DNA Markers for Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease Tolerance in Litopenaeus vannamei through a Genome-Wide Association Study. Biology 2024, 13, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, X.; Aweya, J.J.; Wang, F.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, Y. SNPs in the Toll1 Receptor of Litopenaeus vannamei Are Associated with Immune Response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 72, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeputte, M.; Kashem, M.A.; Bossier, P.; Vanrompay, D. Vibrio Pathogens and Their Toxins in Aquaculture: A Comprehensive Review. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1858–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Hong, W.; Jiang, C.; Guan, N.; Ma, C.; Zeng, H.; et al. SLAF-Seq: An Efficient Method of Large-Scale de Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping Using High-Throughput Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Long-Read Alignment with Burrows–Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce Framework for Analyzing next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P. Variant Annotation and Functional Prediction: SnpEff. In Variant Calling: Methods and Protocols; Ng, C., Piscuoglio, S., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulchenko, Y.S.; Ripke, S.; Isaacs, A.; van Duijn, C.M. GenABEL: An R Library for Genome-Wide Association Analysis. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1294–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.M.; Sul, J.H.; Service, S.K.; Zaitlen, N.A.; Kong, S.; Freimer, N.B.; Sabatti, C.; Eskin, E. Variance Component Model to Account for Sample Structure in Genome-Wide Association Studies. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, J.C.; Fry, B.; Maller, J.; Daly, M.J. Haploview: Analysis and Visualization of LD and Haplotype Maps. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Alfaro, A.; Arroyo, B.B.; Leon, J.A.R.; Sonnenholzner, S. Metabolic Responses of Penaeid Shrimp to Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease Caused by Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Change of Antibiotic Resistance in Vibrio spp. during Shrimp Culture in Shanghai. Aquaculture 2024, 580, e740303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-T.; Chen, I.-T.; Yang, Y.-T.; Ko, T.-P.; Huang, Y.-T.; Huang, J.-Y.; Huang, M.-F.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, S.-S.; et al. The Opportunistic Marine Pathogen Vibrio parahaemolyticus Becomes Virulent by Acquiring a Plasmid That Expresses a Deadly Toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10798–10803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Olive, J.D.; Alam, M.; Ali, A. Vibrio spp. Infections. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2018, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers, M.-A.; Basuyaux, O.; Le Goïc, N.; Huchette, S.; Nicolas, J.-L.; Koken, M.; Paillard, C. Influence of Temperature and Spawning Effort on Haliotis tuberculata Mortalities Caused by Vibrio harveyi: An Example of Emerging Vibriosis Linked to Global Warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega-Orozco, L.; Acedo-Félix, E.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Jiménez-Flores, R.; Cano, R. Pathogenic and Non Pathogenic Vibrio Species in Aquaculture Shrimp Ponds. Rev. Latinoam. Microbiol. 2007, 49, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Li, F. Hepatopancreas Color as a Phenotype to Indicate the Infection Process of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.H.; Hsu, S.F.; Chen, C.K.; Ting, Y.Y.; Chao, W.L. Relationships between Disease Outbreak in Cultured Tiger Shrimp (Penaeus monodon) and the Composition of Vibrio Communities in Pond Water and Shrimp Hepatopancreas during Cultivation. Aquaculture 2001, 192, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madesh, S.; Sudhakaran, G.; Sreekutty, A.R.; Kesavan, D.; Almutairi, B.O.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Dhanaraj, M.; Seetharaman, S.; Arockiaraj, J. Exploring Neem Aqueous Extracts as an Eco-Friendly Strategy to Enhance Shrimp Health and Combat EHP in Aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 3357–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Xu, W.; Du, Y.; Chen, J. Transcriptomic Analysis Provides Insights into the Mechanisms Underlying the Resistance of Penaeus vannamei to Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 154, 109902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wen, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Li, H.; Chen, G.; Zhu, J.; Luo, P. Correlation between Variations in Promoter Region of LvITGβ Gene and Anti-Infection Trait of Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, against a Microsporidium, Ecytonucleospora hepatopenaei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 161, 110302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Mandal, M. VIBRIO|Vibrio cholerae. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusayni, A.A.; Al-Khikani, F.H.O. Growth of Different Bacteria on Thiosulfate Citrate Bile Salts Sucrose Agar. J. Mar. Med. Soc. 2024, 26, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pinto, A.; Terio, V.; Novello, L.; Tantillo, G. Comparison between Thiosulphate-Citrate-Bile Salt Sucrose (TCBS) Agar and CHROMagar Vibrio for Isolating Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Food Control 2011, 22, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, H. Distribution of Vibrio Species Isolated from Aquatic Environments with TCBS Agar. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2000, 4, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, K.-Y.; Letchumanan, V.; Law, J.W.-F.; Pusparajah, P.; Goh, B.-H.; Mutalib, N.-S.A.; He, Y.-W.; Lee, L.-H. Incidence of Antibiotic Resistance in Vibrio spp. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2590–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagley, S. The Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) State in Vibrio Species: Why Studying the VBNC State Now Is More Exciting than Ever. In Vibrio spp. Infections; Almagro-Moreno, S., Pukatzki, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyanan, S.; Chaiyanan, S.; Huq, A.; Maugel, T.; Colwell, R.R. Viability of the Nonculturable Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 24, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casasola-Rodríguez, B.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Pilar, R.-C.; Losano, L.; Ignacio, M.-R.; Orta de Velásquez, M.T. Detection of VBNC Vibrio cholerae by RT-Real Time PCR Based on Differential Gene Expression Analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowska, J.; Oliver, J.D. Resistance to Environmental Stresses by Vibrio vulnificus in the Viable but Nonculturable State. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 84, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhai, S.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, S. Genome-Wide Association Study toward Efficient Selection Breeding of Resistance to Vibrio alginolyticus in Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Li, W.; Xie, Y.; Wu, B.; Sun, Y.; Tian, Q.; Wang, Z.; Han, F. A molecular insight into the resistance of yellow drum to Vibrio harveyi by genome-wide association analysis. Aquaculture 2021, 543, 736998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Han, F. Integrative GWAS and eQTL Analysis Identifies Genes Associated with Resistance to Vibrio harveyi Infection in Yellow Drum (Nibea albiflora). Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1435469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shah, T.; Hao, Z.; Taba, S.; Zhang, S.; Gao, S.; Liu, J.; Cao, M.; Wang, J.; Prakash, A.B.; et al. Comparative SNP and Haplotype Analysis Reveals a Higher Genetic Diversity and Rapider LD Decay in Tropical than Temperate Germplasm in Maize. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, N.; Collins, A.; Morton, N.E. Effects of Single SNPs, Haplotypes, and Whole-genome LD Maps on Accuracy of Association Mapping. Genet. Epidemiol. 2007, 15, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, J.; Schneider, U.; Howald, I.; Schmidt, A.; Hall, M.N. HEAT Repeats Mediate Plasma Membrane Localization of Tor2p in Yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 37011–37020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahara, T.; Hara, K.; Yonezawa, K.; Sorimachi, H.; Maeda, T. Nutrient-Dependent Multimerization of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin through the N-Terminal HEAT Repeat Region. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 28605–28614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghan, J.; Li, X. The HEAT Repeat Protein ILITYHIA Is Required for Plant Immunity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuhagr, A.M.; MacLea, K.S.; Chang, E.S.; Mykles, D.L. Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling genes in decapod crustaceans: Cloning and tissue expression of mTOR, akt, rheb, and p70 S6 kinase in the green crab, Carcinus maenas, and blackback land crab, Gecarcinus lateralis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2014, 168, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Sun, G.; Wang, B.; Jiang, K.; Shao, J.; Qi, C.; Zhao, W.; Han, S.; Liu, M.; et al. Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Inhibition with Rapamycin Induces Autophagy and Correlative Regulation in White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Front. Immunol. 2018, 24, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, M.; Li, F. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Gill Reveals Genes Belonging to mTORC1 Signaling Pathway Associated with the Resistance Trait of Shrimp to VPAHPND. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1150628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.; Poon, A.F.Y. Phylogenetic Measures of Indel Rate Variation among the HIV-1 Group M Subtypes. Virus Evol. 2019, 5, vez022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.G.; Smith, C.W.J. Intron Retention as a Component of Regulated Gene Expression Programs. Hum. Genet. 2017, 136, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naro, C.; Sette, C. Timely-Regulated Intron Retention as Device to Fine-Tune Protein Expression. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Qu, K.; Chen, N.; Hanif, Q.; Jia, Y.; Huang, Y.; Dang, R.; Zhang, J.; Lan, X.; Chen, H.; et al. Genome-Wide SNPs and InDels Characteristics of Three Chinese Cattle Breeds. Animals 2019, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasertlux, S.; Khamnamtong, B.; Chumtong, P.; Klinbunga, S.; Menasveta, P. Expression Levels of RuvBL2 during Ovarian Development and Association between Its Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) and Growth of the Giant Tiger Shrimp Penaeus monodon. Aquaculture 2010, 308, S83–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.-S.; Choi, S.S. Introns: The Functional Benefits of Introns in Genomes. Genom. Inform. 2015, 13, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiholzer, R.A.; Mehta, S.; Kazantseva, M.; Drummond, C.J.; McKinney, C.; Young, K.; Slater, D.; Morten, B.C.; Avery-Kiejda, K.A.; Lasham, A.; et al. Intronic TP53 Polymorphisms Are Associated with Increased Δ133TP53 Transcript, Immune Infiltration and Cancer Risk. Cancers 2020, 12, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lützelberger, M.; Reinert, L.S.; Das, A.T.; Berkhout, B.; Kjems, J. A Novel Splice Donor Site in the Gag-Pol Gene Is Required for HIV-1 RNA Stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 18644–18651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.