Simple Summary

Gymnodiptychus integrigymnatus, a member of the subfamily Schizothoracinae, is found exclusively in the streams of the Gaoligongshan Mountains. This study aimed to elucidate the phylogenetic relationships and mitogenomic characteristics of G. integrigymnatus. The results indicated that the mitochondrial genome of G. integrigymnatus was similar to those of other fish species in terms of gene order, nucleotide composition, codon usage bias, and tRNA gene structure. Furthermore, the phylogenetic tree constructed from the 13 mitochondrial protein-coding genes revealed the Schizothoracinae subfamily as non-monophyletic. Additionally, G. integrigymnatus was resolved outside the clade containing its congeners in the genus Gymnodiptychus.

Abstract

Gymnodiptychus integrigymnatus is a small endemic fish species found in southwest China. This study aimed to investigate the phylogenetic relationships and mitogenomic characteristics of G. integrigymnatus. The complete mitochondrial genome of one individual of G. integrigymnatus was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten sequencing platform and comprehensively characterized. The mitochondrial genome was 16,714 bp in length, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and a typical control region. The genome composition showed a positive A + T skew (0.029) and a negative G + C skew (−0.198). All tRNAs were predicted to form typical cloverleaf secondary structures, except for tRNA-Ser (GCT), which lacked the DHU stem. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on 13 PCGs revealed that the subfamily Schizothoracinae was not a monophyletic group. Two major clades were identified within this subfamily: one comprising primitive taxa (Percocypris, Aspiorhynchus, and Schizothorax) and the other consisting of specialized and highly specialized groups. Gymnodiptychus integrigymnatus was distinct from both its congeners and the specialized clade and was instead recovered within a highly specialized group of the Schizothoracinae subfamily. This study offers novel perspectives on the taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships within the Schizothoracinae subfamily, with a specific focus on G. integrigymnatus, thereby enhancing the understanding of the systematics and phylogeny of the Schizothoracinae subfamily.

1. Introduction

The subfamily Schizothoracinae is a special group within the family Cyprinidae that has adapted to the cold-water environments of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau and its surrounding areas [1,2]. Its unique features, such as scale degeneration and specialized large scales (pelvic scales) located on both sides of the anus and the pelvic fins, make it an ideal model for studying fish adaptation, evolution, and biogeography on the plateau. Cao et al. classified the subfamily Schizothoracinae into three grades: primitive, specialized, and highly specialized Schizothoracine fishes [3]. This classification is based on characteristics such as modifications in scales, pharyngeal teeth, and barbels. This division is closely associated with the adaptive radiation prompted by the sequential uplift of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau [4,5,6].

The genus Gymnodiptychus was categorized as specialized, along with Diptychus and Ptychobarbus. A morphology-based cladistic analysis by Chen and Chen supported the monophyly of the specialized schizothoracines and the genus Gymnodiptychus, thus placing G. integrigymnatus within a monophyletic Gymnodiptychus [7]. In contrast, a subsequent molecular phylogeny based on the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene by He et al. revealed a different scenario, suggesting that the specialized schizothoracines were not monophyletic and G. integrigymnatus was not grouped with its nominal congeners but was closely related to the highly specialized Schizothoracine fishes [8]. These results indicate that the morphological interpretations may be influenced by adaptive convergence, whereas single-gene datasets often lack the signal required to firmly establish deep nodes in the phylogeny.

Gymnodiptychus integrigymnatus is a specialized Schizothoracine fish endemic in China, with its distribution limited to the streams of the Gaoligongshan Mountains [9]. It is unique in that it has no scales all over its body, retaining only the anal and lateral axillary scales at the base of the pelvic fins. The dorsal side of G. integrigymnatus is yellowish brown with scattered black spots, whereas the abdomen is white [2]. The population of this species experiences a continuous decline owing to the vulnerability of its habitat and the adverse effects of anthropogenic activities. It has been listed as a vulnerable species (VU) in the IUCN Red List [10] and presently recognized as a key protected species within the Gaoligongshan Mountain National Nature Reserve. Current research endeavors predominantly concentrate on morphological classification and distribution assessments, whereas investigations at the molecular level, particularly genomic analyses, are comparatively limited.

The mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) is a powerful molecular marker for phylogenetic studies, particularly valued for its maternal inheritance, relatively rapid evolutionary rate, and conserved gene content across animals [11,12]. Therefore, it has been extensively used as a molecular marker for species identification, population genetics, and phylogenetic reconstruction [13,14]. In fishes, the typical mitogenome is a circular molecule of 15–18 kb, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, alongside a control region [15,16]. Compared with single genes, the complete mitogenome offers more comprehensive and dependable phylogenetic signals, rendering it a valuable resource for resolving phylogenetic controversies [17,18]. Thus, it serves as a valuable tool to re-evaluate the conflicting phylogenetic hypotheses surrounding G. integrigymnatus. Previous studies largely focused on sequence variation in PCGs; however, recent advancements in DNA sequencing technologies and assembly strategies have made it possible to characterize the mitogenomes of numerous fish species [19,20,21,22]. A deeper analysis of structural features, such as tRNA secondary structure stability and codon usage bias, can provide valuable insights into evolutionary adaptation [23,24,25,26,27]. Investigating these subtle molecular features, particularly in the extremely high-altitude habitats inhabited by Schizothoracinae fishes may provide key insights into potential adaptive evolutionary mechanisms.

This study aimed to analyze the complete mitochondrial genome of G. integrigymnatus to fill the gap in the genetic information of this species and address the following key scientific questions: (1) What are the structural features, codon usage patterns, and tRNA secondary structures of the mitochondrial genome of G. integrigymnatus? (2) Using complete mitogenome sequences, what are the phylogenetic relationships of G. integrigymnatus with other species within the genus Gymnodiptychus and the major groups within the subfamily Schizothoracinae? (3) Does the mitogenome phylogeny support the morphological classification of G. integrigymnatus, or does it indicate a case of morphological convergence? The findings may provide a genetic foundation for further investigations into the taxonomy, population genetics, adaptive evolution, and conservation management of G. integrigymnatus, as well as the phylogenetic relationships of species within Schizothoracinae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection, DNA Extraction, and Sequencing

One individual of G. integrigymnatus was collected in August 2024 from Tengchong County, Yunnan Province, China (25°25′24″ N, 98°39′8″ E). The specimen was preserved in anhydrous ethanol and deposited in the School of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University (GZNUSLS202408797). The experiments involving G. integrigymnatus in this study were performed in compliance with the national standards for laboratory animal care and treatment. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the muscle using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). Its integrity, purity, and concentration were evaluated using an Agilent 5400 fragment analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed on total genomic DNA without prior mitochondrial enrichment. The DNA sample was tested and then fragmented using a Covaris focused-ultrasonicator. Subsequently, a DNA library was prepared through terminal repair, A-tail addition, sequencing adaptor addition, purification, and PCR amplification. The concentration of the library was measured with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Singapore). The inserted fragments of the library were analyzed using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequencing was conducted on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten sequencing platform at the DNA Stories Bioinformatics Center in Chengdu, Sichuan, China. The mitochondrial genome sequences were subsequently bioinformatically sorted and assembled, as described in the following section.

2.2. Sequence Analyses

Quality control and filtering of the raw dataset were performed as follows. Raw sequencing reads in the BCL format were converted into FASTQ files using Bcl2Fastq v.2.20.0. The quality of the raw reads was assessed with FastQC v. 0.11.4 [28]. Adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and undetermined bases were then filtered using SOAPfilter v.2.2 software with the following criteria: (1) removal of reads containing adapter sequences; (2) discarding paired-end reads if >3% of bases in either read were undetermined (N); and (3) removal of paired-end reads if >50% of bases in either read had a quality score below 3. This process yielded high-quality, clean data for subsequent assembly. The mitogenome clean data were assembled using GetOrganelle v. 1.7.7.0 [29] with default parameters. Subsequently, the assembled mitogenome sequence was annotated using the MitoAnnotator tool on the MitoFish homepage [30]. tRNA genes were further identified and their secondary structures predicted using MITOS v 2.1.9 on the Galaxy platform [31]. The secondary structures of tRNAs were drawn using MITOS. The base composition, codon usage, and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) for each PCG were calculated using PhyloSuite v1.2.3 [32]. The sequences were further analyzed by determining A + T skew and G + C skew using standard formulas: the A + T skew was defined as (A% − T%)/(A% + T%), whereas the G + C skew was defined as (G% − C%)/(G% + C%) [33].

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

The mitochondrial genomes from 75 species within the subfamily of Schizothoracinae, along with 8 outgroup taxa, comprising 124 samples, were retrieved from the NCBI database to investigate the phylogenetic relationships between G. integrigymnatus and the subfamily Schizothoracinae (Table S1). These sequences were subsequently integrated with the newly assembled complete mitochondrial genome of G. integrigymnatus obtained in this study to conduct phylogenetic analyses. The shared 13 concatenated PCGs were extracted and recombined to construct a matrix using PhyloSuite [32]. MAFFT v7.0 [34] was used to align the nucleotide sequences of the concatenated supergene comprising 13 PCGs with default parameters. The optimal partition strategy and the best-fit evolution model of each partition were estimated using PartitionFinder v2.1.1 [35] under the corrected Akaike information criterion and a greedy search scheme. The best-fit scheme defined 10 partitions (P1–P10). The GTR + I + G model was assigned to eight partitions: P1 (ATPase 6), P3 (COXI, COXIII), P4 (COXII), P5 (Cyt b), P6 (ND1, ND3, ND4), P7 (ND2), P9 (ND5), and P10 (ND6). The remaining partitions were P2 (ATPase 8; HKY + I + G) and P8 (ND4L; GTR + G). Bayesian inference (BI) analysis was implemented using MrBayes v3.2.6 [36] under the unlinked branch lengths of each partition scheme. Each dataset was analyzed with two independent runs of four Markov chain Monte Carlo chains (one cold chain and three heated chains), which were run for two million generations and samples were saved for every 100 generations. Convergence was confirmed using an average potential scale reduction factor of 1.004 and an average estimated sample size of 266.06, after discarding the first 25% of samples as burn-in. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was performed using IQ-tree v.1.6.8 [37] with 10,000 bootstrap replicates using the ultrafast bootstrapping algorithm and a maximum of 1000 iterations. All analytical tools were integrated in PhyloSuite with default parameters. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using FigTree v1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/, accessed on 26 November 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Mitogenome Organization and Nucleotide Composition

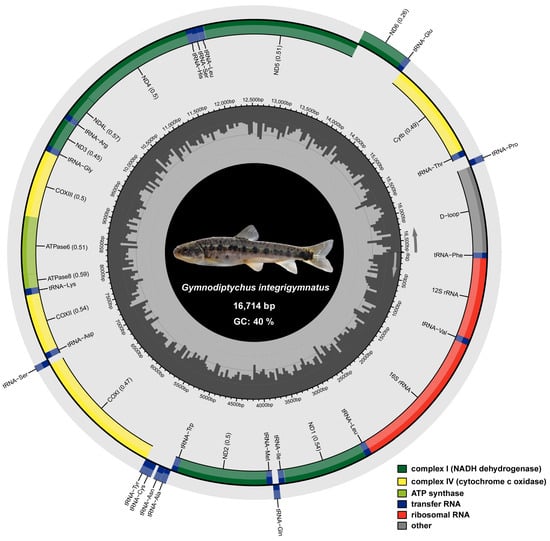

The total length of G. integrigymnatus mitogenome sequence was 16,714 bp. The complete mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus was annotated and submitted to GenBank. It comprised 13 typical PCGs, 22 tRNA genes, 2 rRNA genes, and 1 control region (Figure 1 and Table 1). Most PCGs were located on the heavy strand (H-strand), with only the ND6 gene on the light strand (L-strand). Among the 22 tRNA genes, 14 were on the H-strand [tRNA-Phe, tRNA-Val, tRNA-Leu (UUR), tRNA-Ile, tRNA-Met, tRNA-Trp, tRNA-Asp, tRNA-Lys, tRNA-Gly, tRNA-Arg, tRNA-His, tRNA-Ser (AGY), tRNA-Leu (CUN), and tRNA-Thr]. The remaining eight tRNA genes were on the L-strand [tRNA-Gln, tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Asn, tRNA-Cys, tRNA-Tyr, tRNA-Ser (UCN), tRNA-Glu, and tRNA-Pro] (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Mitogenome circle map of G. integrigymnatus. Genes encoded on the heavy and light strands are depicted inside and outside the circular mitochondrial genome map, respectively. Protein-coding genes associated with NADH dehydrogenase are highlighted in green, whereas those encoding cytochrome c oxidases are highlighted in yellow. Genes for ATP synthase are highlighted in light green. Transfer RNA genes are marked in blue, and ribosomal RNA genes are marked in red. The control region, corresponding to the D-loop, is colored gray.

Table 1.

Mitogenome organization of G. integrigymnatus.

A total of 127 intergenic nucleotides were distributed across 15 intergenic spacer regions in the mitogenomes of G. integrigymnatus, with lengths varying from 1 to 65 bp. The largest spacer was observed between the tRNA-Thr and tRNA-Pro. Moreover, 6 overlapping regions were identified, collectively encompassing 22 bp and ranging in length from 1 to 7 bp. The most extensive overlap was observed between the ATPase 8 and ATPase 6 genes, as well as between the ND4L and ND4 genes. The remaining gene pairs were closely arranged with no intervals or overlaps.

The overall nucleotide composition of the mitogenome sequence was 30.9% A, 29.1% T, 23.9% C, and 16.0% G; it had an A + T-rich feature (60.0%). The A + T contents of PCGs, rRNAs, tRNAs, and the D-loop region all exceeded 50%. The D-loop region, recognized as an A + T-rich segment, exhibited the highest A + T content at 67.5%. Furthermore, the A + T content at the first (50.7%), second (59.8%), and third (72.2%) codon positions of the PCGs exhibited statistically significant differences. The G. integrigymnatus mitogenome was slightly A-skewed and moderately C-skewed, with a positive A + T skew of 0.029 and a negative G + C skew of −0.198 (Table 2). The A + T skew of the mitogenome, tRNAs, rRNAs, and three PCGs (ATPase 8, COXII, and ND2) were all positive, whereas the control region, 10 PCGs, and concatenated PCGs were negative. The A + T skew was negative for the second codon positions of PCGs but positive for the first and third codon positions. Regarding G + C skew of the mitogenome, positive values were observed only for tRNAs, first codon positions of PCGs, and ND6. In contrast, negative G + C skew values were found for rRNAs, concatenated PCGs, second and third codon positions of PCGs, 12 individual PCGs, and the control region (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nucleotide composition, A + T skew, and G + C skew of G. integrigymnatus mitogenome.

3.2. Protein-Coding Genes

The mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus included 13 PCGs, ranging from 165 to 1821 bp in length (Table 1). The A + T content of its PCGs was 60.9%. All the PCGs started with the typical ATG initiation codons, except for COXI, which started with GTG. In contrast, the stop codon usage varied across genes: ND1, ATPase 8, and ND3 employed the complete stop codon TAG; COXI, ND4L, ND5, and ND6 used TAA as the complete stop codon; ATPase 6 and COXIII had the incomplete stop codon TA; and the remaining genes (ND2, COXII, ND4, and Cyt b) terminated with the incomplete stop codon T (Table 1).

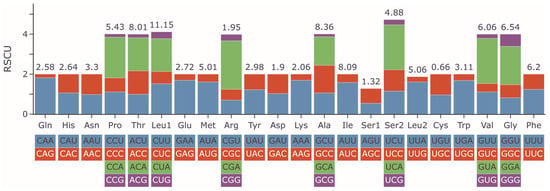

RSCU values were calculated to measure the codon usage bias (Figure 2 and Table S2). The 13 PCGs encoded 3793 amino acids (except for 7 stop codons). The three most utilized codons in G. integrigymnatus mitogenome were AUU, CUA, and UUA. Synonymous codons included 29 preferred codons, each exhibiting an RSCU value greater than 1; the maximum observed value was CGA-Arg (2.43), whereas the minimum was GCG-Ala (0.14). Four codons including GUA, UCA, CCA, and CGA demonstrated RSCU values exceeding 2; all of these codons terminated with A. The most frequently encoded amino acid in proteins was arginine (Arg), followed by valine (Val), serine (Ser), and proline (Pro) (Figure 2 and Table S2).

Figure 2.

RSCU of the mitogenome for G. integrigymnatus. The frequency of each amino acid (top number, %) is presented above the stacked columns.

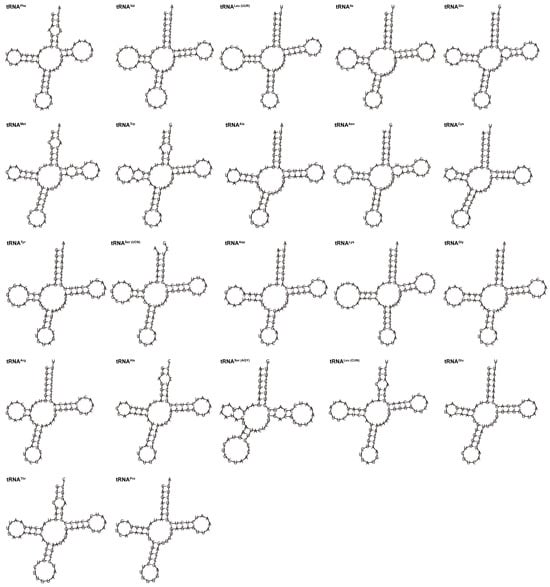

3.3. Transfer RNAs, Ribosomal RNAs, and Control Region

G. integrigymnatus mitogenome had 22 tRNA genes, ranging from 66 to 77 bp in length. These tRNAs exhibited an AT bias (57.3%), similar to the overall mitogenomic composition. The A + T and G + C skew values were 0.039 and 0.042, respectively (Table 2). Except for tRNA-Ser (AGY) exhibiting an incomplete dihydrouridine arm (DHU arm), all the tRNAs were folded into typical cloverleaf secondary structures, which comprised four distinct domains (the amino acid arm, the DHU arm, the anticodon arm, and the TΨC stem) (Figure 3). Furthermore, the findings revealed the presence of canonical G-C and A-U base pairs across all tRNA molecules. However, the sequences also had certain instances of non-canonical or mismatched base pairs. For example, 15 of 22 tRNA genes, including tRNA-Phe, tRNA-Val, tRNA-Leu, tRNA-Gln, tRNA-Met, tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Asn, tRNA-Tyr, tRNA-Ser, tRNA-Asp, tRNA-Lys, tRNA-Gly, tRNA-Arg, tRNA-His, and tRNA-Glu, had 29 G-U mismatches in their secondary structures, which formed a weak bond. Five tRNAs, including tRNA-Trp, tRNA-Ser, tRNA-His, tRNA-Leu, and tRNA-Thr, had A-C mismatches in their amino acid acceptor arm. Two A-G mismatches were identified within the amino acid acceptor arm and the dihydrouridine arm of tRNA-Phe and tRNA-Arg, respectively. A single U-C mismatch of tRNA-Met and one U-U mismatch of tRNA-Asn were found in their TΨC stem. Also, a single A-A mismatch was detected within the dihydrouridine arm of the tRNA-Trp molecule.

Figure 3.

Predicted secondary structures of 22 tRNAs in the mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus.

The mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus also contained two rRNAs. 12S rRNA was 953 bp long and positioned between tRNA-Phe and tRNA-Val, whereas 16S rRNA was 1677 bp long and located between tRNA-Val and tRNA-Leu (UUR). The nucleotide composition of the two ribosomal RNAs was determined to be 21.4% T, 23.0% C, 34.1% A, and 21.4% G. The combined A + T content was 55.5%, which was marginally greater than the combined G and C content. The control region in G. integrigymnatus was 1010 bp long, with an A + T content of 67.5%; it was situated between tRNA-Pro and tRNA-Phe.

3.4. Phylogenetic Relationships

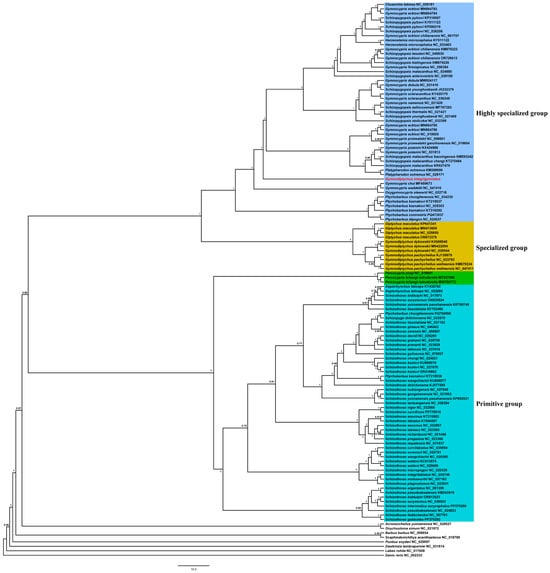

The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the 13 PCGs from 76 species within the subfamily Schizothoracinae, along with eight outgroup species, to determine the phylogenetic position of G. integrigymnatus (Table S1). In this study, 2 different methods, ML and BI, were used to construct trees for the 13 concatenated datasets of PCGs, yielding consistent phylogenetic results (Figure 4 and Figure S1). Our analysis of mitogenomes revealed two distinct clades within Schizothoracinae. One clade included Percocypris, Aspiorhynchus, and Schizothorax from the primitive group, whereas the other encompassed all members of the specialized and highly specialized groups. The phylogenetic results indicated that G. integrigymnatus did not cluster with other species belonging to the genus Gymnodiptychus, but instead grouped with the highly specialized group (Figure 4 and Figure S1).

Figure 4.

BI phylogenetic tree based on 13 PCGs of 76 Schizothoracinae species and 8 outgroup species. Numbers at nodes represent the posterior probability for BI analysis. The red color words denoted species with novel mitogenomes sequenced in this study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mitochondrial Genome Characteristics of G. integrigymnatus

This study sequenced, annotated, and characterized the complete mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus. The results indicated that the mitogenome was a closed double-stranded circular structure, 16,714 bp in length. The length of the mitogenome fell within the range previously reported for the subfamily Schizothoracinae (Table S1). The mitogenome was composed of 37 genes (13 PCGs, 22 tRNAs, and 2 rRNAs) and 1 control region. The genome size, structural organization, and gene composition of the mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus were highly conserved compared with those of most previously characterized Cypriniformes and cyprinid species, consistent with the general evolutionary stability of vertebrate mitochondrial genomes [38,39,40,41,42].

The analysis of codon usage for PCGs revealed some notable characteristics. Specifically, GTG served as a start codon for COXI, whereas ATG was the standard start codon for the other genes. Termination codons were of three main types: TAA, TAG, and the incomplete codon T/TA. The occurrence of incomplete termination codons is common in fish mitochondrial genes [13,43,44]. For these incomplete stop codons, the missing nucleotides may be produced through post-transcriptional polyadenylation [45,46]. Phenomena such as AT bias and incomplete stop codons are frequently observed in the mitochondrial genomes of fishes and may be associated with replication and transcription mechanisms, as well as evolutionary selective pressures [47,48].

4.2. tRNA Secondary Structure, Codon Usage Preference, and Functional Adaptation

All 21 tRNAs in the mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus exhibited a typical cloverleaf secondary structure. However, tRNA-Ser (AGY) was notable for lacking a DHU arm, which is generally present in fish mitogenomes [13,40,43,44]. This phenomenon is regularly observed and may be modified by post-transcriptional editing mechanisms [49]. The secondary structure of tRNAs is fundamentally important for their stability and functional roles. Alterations or deletions of vital elements within the tRNA secondary structure may significantly impact amino acid recognition, consequently disrupting protein synthesis [50]. The tRNA-Ser (AGY) in a majority of vertebrates lacks a DHU arm. Furthermore, the functional consequences resulting from the absence of the DHU arm are mitigated through compensatory interactions [49,51]. Notably, compared with closely related species, specific tRNAs in G. integrigymnatus, such as tRNA-Arg and tRNA-Ile, demonstrated a relatively elevated G + C content within their amino acid acceptor arm and TΨC stem. G + C base pairs formed three hydrogen bonds, whereas AT base pairs formed only two hydrogen bonds. This difference means that an increased G + C proportion was generally associated with enhanced thermal stability in these regions, as demonstrated in prokaryotes [52]. This subtle structural modification may constitute a molecular adaptation to low-temperature conditions, considering the cold, high-altitude aquatic environment inhabited by G. integrigymnatus. This is consistent with the overarching principle that molecular structures, such as elements of the tRNA apparatus, experience adaptive evolutionary changes to preserve their functionality under thermal stress. This is supported by research on tRNA-modifying enzymes in eukaryotes adapted to cold environments [53,54]. Such an adaptation likely contributes to the preservation of tRNA structural integrity and functionality under cold stress, thereby facilitating the proper progression of mitochondrial translation. This observation offers novel insights into the organelle-level mechanisms underlying environmental adaptation in plateau fish species.

Codon usage analysis across 13 PCGs in G. integrigymnatus revealed a strong preference for A- or T-ending codons, such as UUA (Leu), AUU (Ile), and GUA (Val). In contrast, C- or G-ending codons, such as GCG (Ala), GUG (Val), and GGC (Gly), were underrepresented. This A + T bias is consistent with both the overall high A + T content of the mitochondrial genome, suggesting the influence of mutational pressure, and the abundance of tRNAs recognizing these preferred codons, reflecting natural selection for translational efficiency [55]. This pattern, where codon usage co-evolves with the tRNA pool to optimize translation, is a recognized adaptive strategy in mitochondria. Previous studies showed that tRNA genes corresponding to highly used codons were strategically positioned for efficient expression and translational selection dominated codon usage bias in mitochondrial genomes [56,57]. Thus, the observed codon usage pattern likely arose from the interplay of mutation pressure driving A + T enrichment and selection favoring codons matched by abundant tRNAs. Such optimization is particularly crucial in mitochondria, where energy production demands highly efficient translation to minimize metabolic costs and maintain proteostasis [58]. Consistent with this, our analysis of tRNA genes indicated that the tRNA repertoire in G. integrigymnatus was adequate to recognize the frequently employed A + T-ending codons. Consequently, the observed codon usage pattern likely resulted from the interplay between mutational pressure, which promoted genome-wide A + T enrichment, and natural selection, which preferentially fixed codons matching highly abundant tRNAs to optimize translation. This may have important adaptive significance in mitochondria, where the energy demand is extremely high. The analysis of RSCU for the PCGs of G. integrigymnatus in the present study revealed that the codons GUA, UCA, CCA, and CGA were the most frequently utilized, corresponding to the amino acids Arg, Val, Ser, and Pro, respectively. Previous studies indicated that the codon usage patterns associated with functional gene expression and protein sequence encoding might be influenced by natural selection across species [40,55].

Further, the mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus comprises one noncoding region, known as the D-loop, similar to that in other species within the Schizothoracinae subfamily (Table S1). The D-loop has a faster evolutionary rate and is frequently utilized as a marker to assess and compare population genetic diversity, genetic structure, and phylogenetic relationships within Schizothoracinae [59,60].

4.3. Reevaluation of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Subfamily Schizothoracinae

The phylogenetic relationships of the Schizothoracinae subfamily have long been a key area of research in the study of fishes on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. Previous studies have focused on the phylogenetic relationship of the Schizothoracinae subfamily using single or multiple genes, and mitochondrial genome sequences [4,61,62]. However, the lack of the unique species, G. integrigymnatus, has limited our comprehensive understanding of the phylogenetic relationship of the Schizothoracinae subfamily. The results of phylogenetic studies have indicated that the Schizothoracinae subfamily is not a monophyletic group. This result aligns with previous findings [61,63]. G. integrigymnatus does not belong to the genus Gymnodiptychus. This implies that the traditional classification of Schizothoracine fishes based on shared morphological traits such as “pelvic scales” may not actually reflect descent from a common recent ancestor. The observed non-monophyly within this group is most plausibly attributed to convergent evolution in morphological traits. Distinct lineages within the Cyprinidae family have independently developed analogous features, such as pelvic scales and exposed body regions, in response to the selective pressures of the fast-flowing, cold aquatic environments characteristic of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. These features, previously regarded as synapomorphies defining the Schizothoracine subfamily, are, in fact, homoplastic traits that have arisen multiple times independently. Two hypotheses may explain this pattern: (1) Taxonomic revision hypothesis: The morphological classification of G. integrigymnatus within the genus Gymnodiptychus may be based solely on certain ancestral traits or characteristics resulting from parallel evolution. Genetically, it exhibits a closer association with the genus Gymnocypris or its related taxa. Consequently, forthcoming taxonomic revisions may require a comprehensive reassessment of the systematic placement of G. integrigymnatus. (2) Ancient hybridization and introgression hypothesis: The formation of G. integrigymnatus might have involved historical hybridization events. Its nuclear genome might have originated primarily from the ancestor of the genus Gymnodiptychus, whereas the mitochondrial genome (maternally inherited) was derived from a lineage similar to the ancestor of the genus Gymnocypris. This led to a conflict between the mitochondrial genome–based phylogenetic tree and the morphology-based classification system, which was likely more influenced by nuclear genes. In summary, it suggests that the classification of G. integrigymnatus requires further in-depth investigation. This study provides a valuable mitochondrial genome resource promoting research on the taxonomy and molecular phylogeny of the Schizothoracinae subfamily.

4.4. Importance of Safeguarding and Prospective Developments

This study presents the first comprehensive mitochondrial genome reference sequence for G. integrigymnatus. This genomic may be instrumental in future investigations of population genetic diversity and in the application of DNA barcoding techniques aimed at addressing illegal trade [64,65]. Furthermore, elucidating the phylogenetic placement of this species holds immense importance for advancing the understanding of adaptive radiation processes and the mechanisms underlying biodiversity formation within the Schizothoracinae subfamily. Considering the endangered status of G. integrigymnatus, the genetic information generated in this study provides a valuable scientific foundation for the conservation and sustainable management of its germplasm resources [66].

Considering the intricate evolutionary history of fishes belonging to the Schizothoracinae subfamily, the dramatic environmental changes on the plateau have imposed similar natural selection pressures on various fish lineages, resulting in widespread morphological convergence. This phenomenon, which has been shown to mislead taxonomy in Schizothoracine fishes, limits the reliability of inferring phylogenetic relationships based solely on morphological traits [67]. Therefore, future investigations should prioritize the integration of nuclear gene data by applying of transcriptome sequencing or reduced representation genome sequencing methodologies to acquire a comprehensive set of nuclear gene markers. This approach can facilitate the construction of species trees and enable the validation of findings derived from maternally inherited mitochondrial genomes in the present study. Moreover, expanding taxonomic sampling by intensifying the collection and genomic sequencing of the Schizothoracinae subfamily and closely related taxa within the Cyprinidae family is essential for accurately resolving divergence times and elucidating the evolutionary trajectories of each lineage. Future studies should focus on elucidating the genetic underpinnings of key morphological traits by examining the genes responsible for key features, such as scale development, and their evolutionary histories. This may allow for the testing of hypotheses regarding convergent evolution from a developmental biology standpoint.

5. Conclusions

This study was novel in successfully sequencing and reporting the complete mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus. We characterized the structure of the mitogenome and found that it shared common features with other fishes belonging to the Schizothoracinae subfamily, including gene order and nucleotide composition, and focused on the codon usage bias and tRNA structure. We clarified the phylogenetic status of G. integrigymnatus by constructing phylogenetic trees using ML and BI methods based on the 13 PCGs. The phylogenetic analysis indicated that the Schizothoracinae subfamily was not a monophyletic group. G. integrigymnatus does not belong to the genus Gymnodiptychus but belongs to a highly specialized group within the Schizothoracinae subfamily. Future studies should integrate nuclear genomic data to distinguish between homology and convergent similarity. This study provides valuable genetic resources for understanding the phylogeny and biogeography of the Schizothoracinae subfamily, lying a foundation for the conservation genetics of G. integrigymnatus.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology14121760/s1. Figure S1. ML phylogenetic tree based on 13 PCGs of 76 Schizothoracinae species and 8 outgroup species. Numbers at nodes represent the bootstrap values for ML analysis. Table S1. List of species used in phylogenetic analyses based on mitogenomes. Table S2. Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of protein-coding genes in the mitogenome of G. integrigymnatus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.L. (Yanping Li) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Methodology: Y.L. (Yawen Luo) and R.Z. (Ruilin Zhang). Software: Y.L. (Yawen Luo), Y.L. (Yunyun Lv), Y.O. and R.Z. (Ruilin Zhang). Validation: Y.L. (Yunyun Lv) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Formal analysis: Y.L. (Yanping Li), Y.L. (Yawen Luo) and R.Z. (Ruilin Zhang). Investigation: Y.L. (Yunyun Lv) and Y.O. Resources: Y.L. (Yunyun Lv) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Data curation: Y.L. (Yawen Luo), Y.L. (Yunyun Lv) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Writing—original draft preparation: Y.L. (Yanping Li) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Writing—review and editing: Y.L. (Yanping Li), Y.L. (Yunyun Lv) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Visualization: Y.L. (Yanping Li), Y.L. (Yawen Luo) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Supervision: Y.L. (Yanping Li) and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). Project administration: Y.O. and R.Z. (Ruilin Zhang). Funding acquisition: Y.L. (Yanping Li), Y.O. and R.Z. (Renyi Zhang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Open Fund Projects for the Fishes Conservation and Utilization in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Neijiang Normal University (Grant No. NJTCCJSYSYS04); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32160293); the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Support Program (Grant No. 2025ZNSFSC1077); the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Plan for College Students Grant No. X2024002); and the Major Project in Neijiang Normal University (Grant No. 2024ZDZ05).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guizhou Normal University (Approval No. 20221100004).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The mitogenome sequence of G. integrigymnatus has been submitted to GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under the accession no. PX503671.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, D.; Chen, Y. Biogeography and molecular phylogeny of the genus Schizothorax (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) in China inferred from cytochrome b sequences. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, C. The Fishes of the Qinghai—Xizang Plateau; Sichuan Publishing House of Science & Technology: Chengdu, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, S. Origin and Evolution of Schizothoracine Fishes in Relation to the Upheaval of the Xizang Plateau; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1981; pp. 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, D.; Chao, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, T.; Wei, F.; Zhao, X. Convergent, parallel and correlated evolution of trophic morphologies in the subfamily schizothoracinae from the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34070. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, C.; Fei, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, K. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of Tibetan Schizothoracinae fish Gymnocypris przewalskii reveals how it adapts to a high altitude aquatic life. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Duan, Z.Y.; Peng, Z.G.; Guo, S.C.; Li, J.B.; He, S.P.; Zhao, X.Q. The youngest split in sympatric schizothoracine fish (Cyprinidae) is shaped by ecological adaptations in a Tibetan Plateau glacier lake. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 3616–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y. Phylogeny of the specialized schizothoracine fishes (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae). Zool. Stud. 2001, 40, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z. Molecular phylogeny of the specialized schizothoracine fishes (Teleostei: Cyprinidae), with their implications for the uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004, 49, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, J. Molecular and morphological analysis of endangered species Gymnodiptychus integrigymnatus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Environ. Biol. Fish. 2010, 88, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wange, Y. Red list of China’s vertebrates. Biodiv. Sci. 2016, 24, 500–551. [Google Scholar]

- Boore, J.L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, Y. Genetics and evolution of mitochondrial DNA in fish. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2000, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, Q.; Deng, L. The complete mitochondrial genome of Microphysogobio elongatus (Teleostei, Cyprinidae) and its phylogenetic implications. ZooKeys 2021, 1061, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, T.; Li, H.; Deng, L. The mitochondrial genome of Linichthys laticeps (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae): Characterization and phylogeny. Genes 2023, 14, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K. Fish mitochondrial genomics: Sequence, inheritance and functional variation. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 72, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Deng, L.; Lv, X.; Tang, Q. Complete mitochondrial genomes of two catfishes (Siluriformes, Bagridae) and their phylogenetic implications. Zookeys 2022, 1115, 103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernt, M.; Bleidorn, C.; Braband, A.; Dambach, J.; Donath, A.; Fritzsch, G.; Golombek, A.; Hadrys, H.; Jühling, F.; Meusemann, K.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of bilaterian mitochondrial genomes and phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.L.; Lambkin, C.L.; Barker, S.C.; Whiting, M.F. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of Diptera: Whole genome sequence data accurately resolve relationships over broad timescales with high precision. Syst. Entomol. 2007, 32, 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza, J.A.; García-De León, F. Are we there yet? Benchmarking low-coverage nanopore long-read sequencing for the assembling of mitochondrial genomes using the vulnerable silky shark Carcharhinus falciformis. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Sreeedharan, S.; George, S.; Antony, M.M. The complete mitochondrial genome of an endemic cichlid Etroplus canarensis from Western Ghats, India (Perciformes: Cichlidae) and molecular phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 3033–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Xie, N.; Ma, H.-J. Next-generation sequencing reveals the mitogenomic heteroplasmy in the topmouth culter (Culter alburnus Basilewsky, 1855). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 943–950. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, A.; López-Landavery, E.; González-Martinez, S.; Reyes-Flores, L.E.; Corona-Herrera, G.; Tapia-Morales, S.; Yzásiga-Barrera, C.G.; Fernandino, J.I.; Zelada-Mázmela, E. The complete mitochondrial genome of the fine flounder Paralichthys adspersus revealed by next-generation sequencing. Mitochondrial DNA B 2021, 6, 2785–2787. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo, M.N.; Green, J.A.; Cnop, M.; Igoillo-Esteve, M. tRNA biology in the pathogenesis of diabetes: Role of genetic and environmental factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. A comparison of synonymous codon usage bias patterns in DNA and RNA virus genomes: Quantifying the relative importance of mutational pressure and natural selection. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 406342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, A.L.; Gilchrist, M.A. Quantifying shifts in natural selection on codon usage between protein regions: A population genetics approach. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labella, A.L.; Opulente, D.A.; Steenwyk, J.L.; Hittinger, C.T.; Rokas, A. Variation and selection on codon usage bias across an entire subphylum. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashad, S.; Marahleh, A. Metabolism meets translation: Dietary and metabolic influences on tRNA modifications and codon biased translation. WIRES RNA 2025, 16, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data; Babraham Institute: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Yu, W.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; DePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.; Li, D. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Sato, Y.; Sado, T.; Miya, M.; Iwasaki, W. MitoFish, MitoAnnotator, and MiFish Pipeline: Updates in 10 years. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023, 40, msad035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Externbrink, F.; Florentz, C.; Fritzsch, G.; Pütz, J.; Middendorf, M.; Stadler, P.F. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, N.T.; Kocher, T.D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 41, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Duan, G.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, A. Unraveling the mitochondrial blueprint: Genome characterization and phylogenetic insights of the endemic fish Onychostoma virgulatum (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Genes 2025, 16, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Xiang, H.; Jiang, W. Molecular identification of Acrossocheilus jishouensis (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) and its complete mitochondrial genome. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 1396–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, F.; Xu, J.; Zeng, Y. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Schizothorax kozlovi (Cypriniformes, Cyprinidae, Schizothorax) and insights into the phylogenetic relationships of Schizothorax. Animals 2024, 14, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Ma, W.; Chen, X.; Nie, G.; Zhou, C. Four new complete mitochondrial genomes of Gobioninae fishes (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) and their phylogenetic implications. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Tan, C.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Z.; Su, C.; Li, F.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hao, X.; Zou, W.; et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Luciocyprinus langsoni (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae): Characterization, phylogeny, and genetic diversity analysis. Genes 2024, 15, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Xie, J.; Kong, C.; Li, L. The complete mitochondrial genome of a rare cavefish (Sinocyclocheilus cyphotergous) and comparative genomic analyses in Sinocyclocheilus. Pak. J. Zool. 2024, 56, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, T.; Yu, F. The new mitochondrial genome of Hemiculterella wui (Cypriniformes, Xenocyprididae): Sequence, structure, and phylogenetic analyses. Genes 2023, 14, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; De Bruijn, M.H.L.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, D.; Montoya, J.; Attardi, G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature 1981, 290, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, S.; Kumazawa, Y.; Araki, T.; Himeno, H.; Miura, K.-i.; Watanabe, K. Strand-specific nucleotide composition bias in echinoderm and vertebrate mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1991, 32, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Cao, R.; Dong, Y.; Gao, X.; Cen, J.; Lu, S. The first complete mitochondrial genome of the flathead Cociella crocodilus (Scorpaeniformes: Platycephalidae) and the phylogenetic relationships within Scorpaeniformes based on whole mitogenomes. Genes 2019, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrov, D.V.; Brown, W.M.; Boore, J.L. A novel type of RNA editing occurs in the mitochondrial tRNAs of the centipede Lithobius forficatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13738–13742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, J.; Bauzà-Ribot, M.M.; Jaume, D.; Juan, C. Next-generation sequencing, phylogenetic signal and comparative mitogenomic analyses in Metacrangonyctidae (Amphipoda: Crustacea). BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Xie, Q.; Bu, W.; Hillis, D.M. A mitochondrial genome of Rhyparochromidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) and a comparative analysis of related mitochondrial genomes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, E.; Lan, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Niu, D. A positive correlation between GC content and growth temperature in prokaryotes. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, F.G.M.; Erber, L.; Sammler, J.; Jühling, F.; Betat, H.; Mörl, M. Cold adaptation of tRNA nucleotidyltransferases: A tradeoff in activity, stability and fidelity. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C.; Lünse, C.E.; Mörl, M. tRNA modifications: Impact on structure and thermal adaptation. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slimen, H.; Awadi, A.; Tolesa, Z.G.; Knauer, F.; Alves, P.C.; Makni, M.; Suchentrunk, F. Positive selection on the mitochondrial ATP synthase 6 and the NADH dehydrogenase 2 genes across 22 hare species (genus Lepus). J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2018, 56, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, T.P.; Sato, Y.; Masuyama, N.; Miya, M.; Nishida, M. Transfer RNA gene arrangement and codon usage in vertebrate mitochondrial genomes: A new insight into gene order conservation. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; He, J.; Jia, X.; Qi, Q.; Liang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Ping, Y.; Liu, S.; Sun, J. Analysis of codon usage bias of mitochondrial genome in Bombyx mori and its relation to evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhm, T.; Kaimal, J.M.; Dawitz, H.; Peselj, C.; Masser, A.E.; Hanzén, S.; Ambrožič, M.; Smialowska, A.; Björck, M.L.; Brzezinski, P.; et al. Mitochondrial translation efficiency controls cytoplasmic protein homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1309–1322.e1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Li, W.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of Qinghai-Tibetan plateau schizothoracine fish (Gymnocypris dobula) based on mtDNA D-loop sequences. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2016, 69, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; He, D.; Jia, Y.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y. Phylogeographic studies of schizothoracine fishes on the central Qinghai-Tibet Plateau reveal the highest known glacial microrefugia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, M.; Zou, M.; Guan, X.; Xu, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; He, S.; Guo, B. Recent and recurrent autopolyploidization fueled diversification of snow carp on the Tibetan Plateau. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, C.; Kong, X. Molecular phylogeny of the subfamily Schizothoracinae (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2016, 64, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Sado, T.; Hirt, M.V.; Pasco-Viel, E.; Arunachalam, M.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Freyhof, J.; Saitoh, K.; Simons, A.M.; et al. Phylogeny and polyploidy: Resolving the classification of cyprinine fishes (Teleostei: Cypriniformes). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 85, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, A. Application of Mitochondrial DNA Technologies in Wildlife Investigation—Species Identification. Forensic Sci. Rev. 2006, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinoff, D. Utility of Mitochondrial DNA Barcodes in Species Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, A.; Griffin, P.; Dillon, S.; Catullo, R.; Rane, R.; Byrne, M.; Jordan, R.; Oakeshott, J.; Weeks, A.; Joseph, L.; et al. A framework for incorporating evolutionary genomics into biodiversity conservation and management. Clim. Change Res. 2015, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, C.; Wanghe, K.; Feng, C.; Tong, C.; Tian, F.; Zhao, K. Convergent evolution misled taxonomy in schizothoracine fishes (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 134, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).