Effects of Bamboo Expansion on Soil Enzyme Activity and Its Stoichiometric Ratios in Karst Broad-Leaved Forests

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

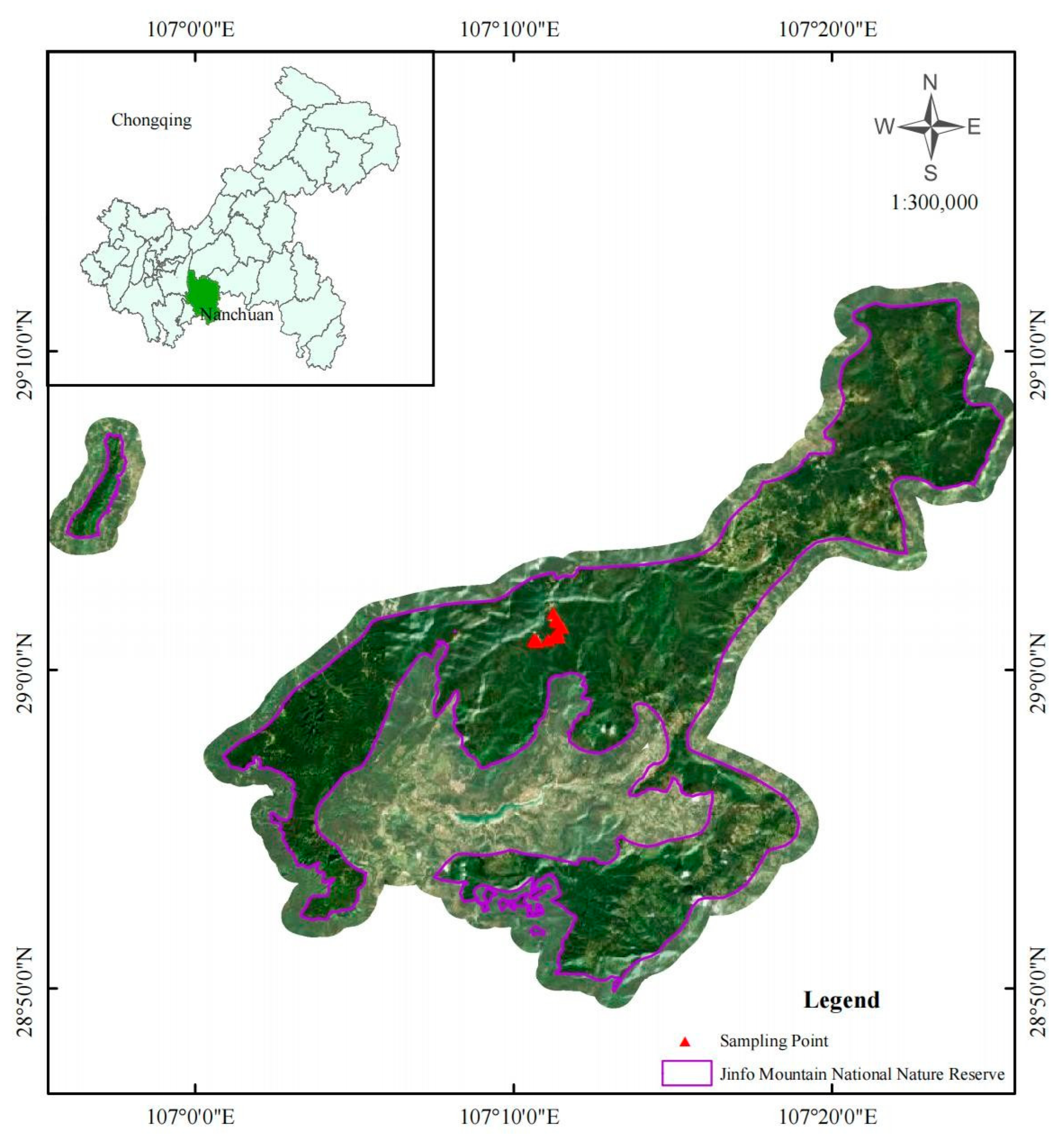

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Collections

2.4. Laboratory Analysis

2.5. Calculation of Microbial Resource Limitation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

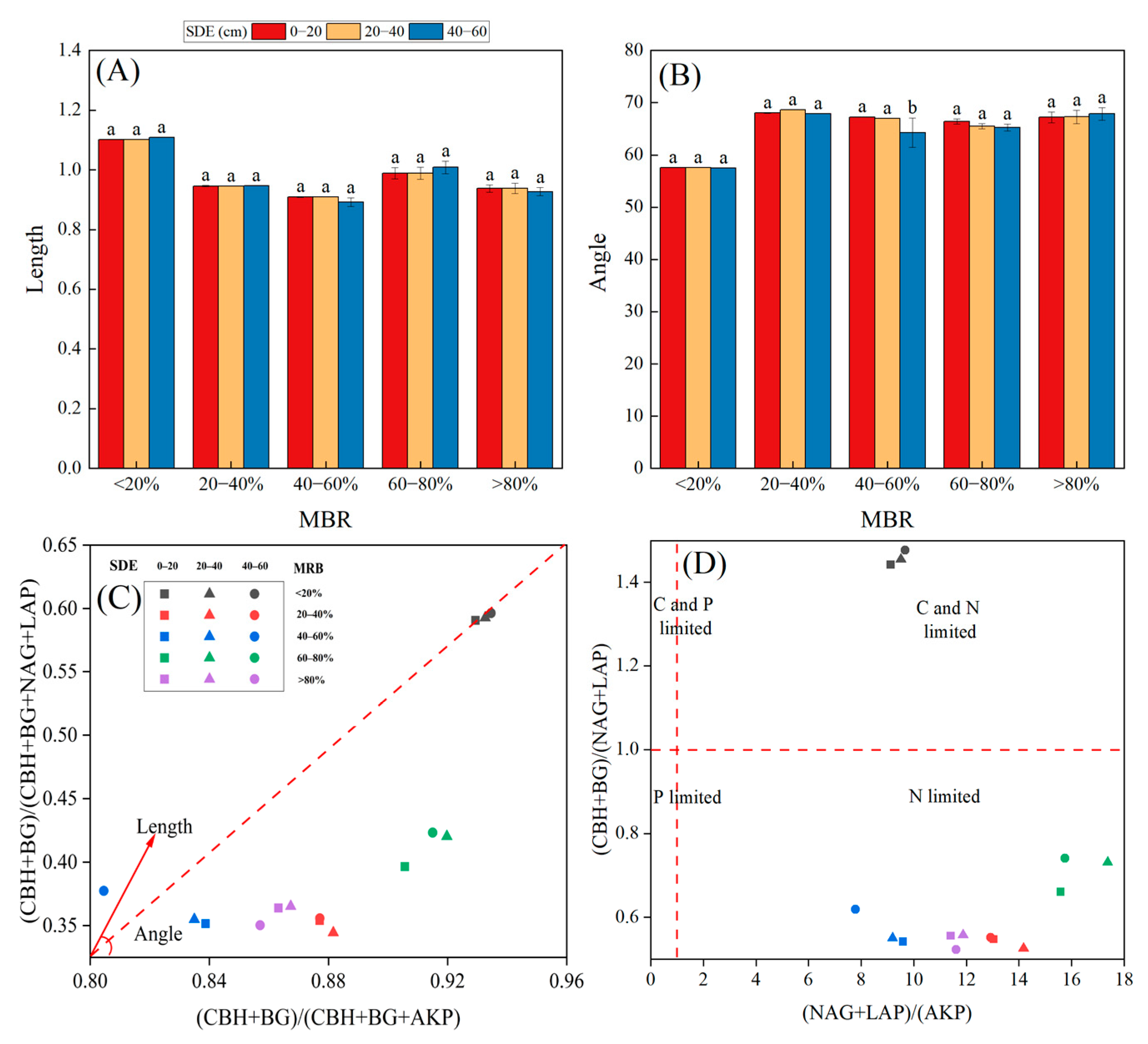

3.1. Root Morphological Characteristics

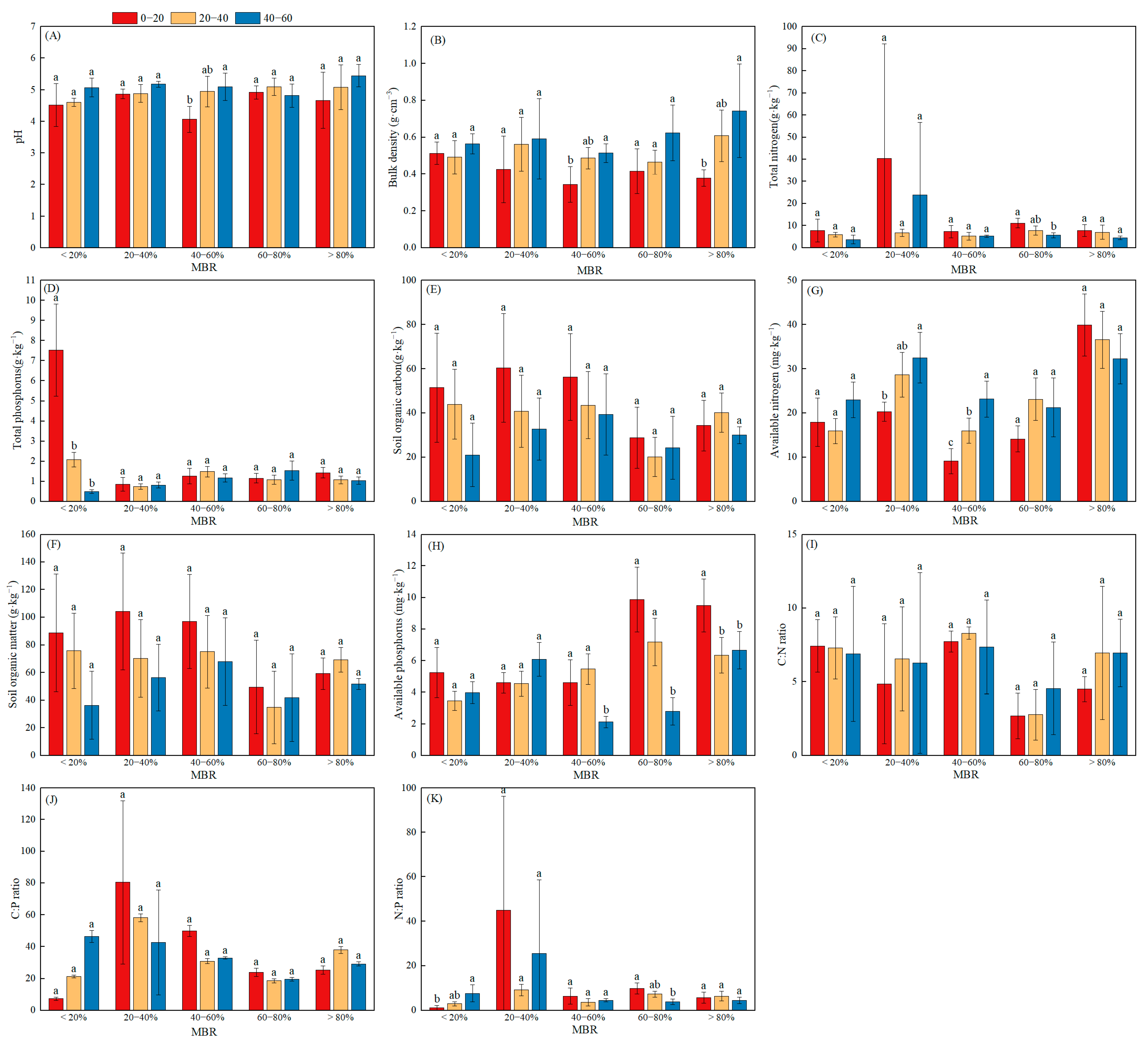

3.2. Soil Nutrient Variables and Their Stoichiometry

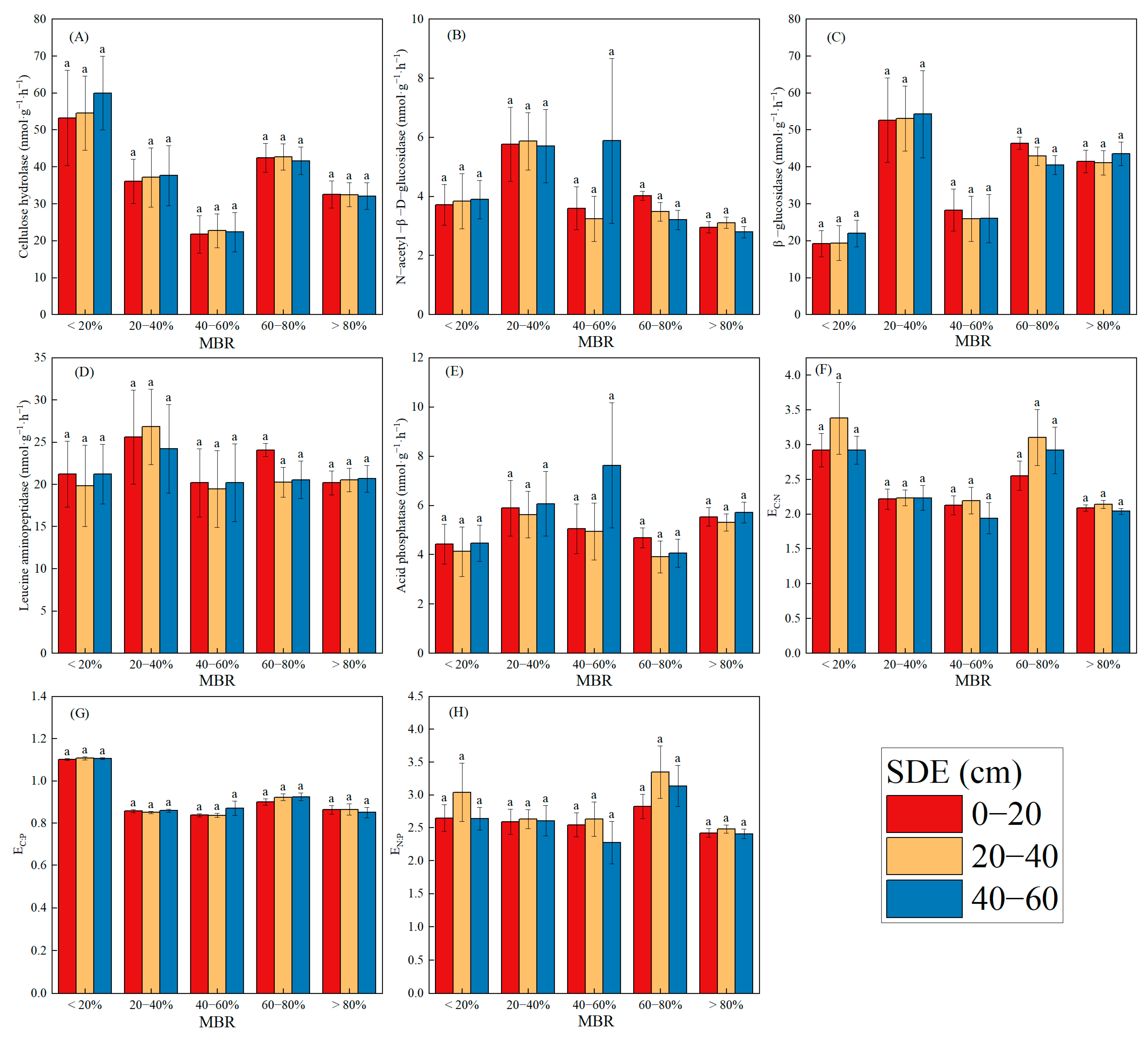

3.3. Soil Enzyme Activities and Their Stoichiometry

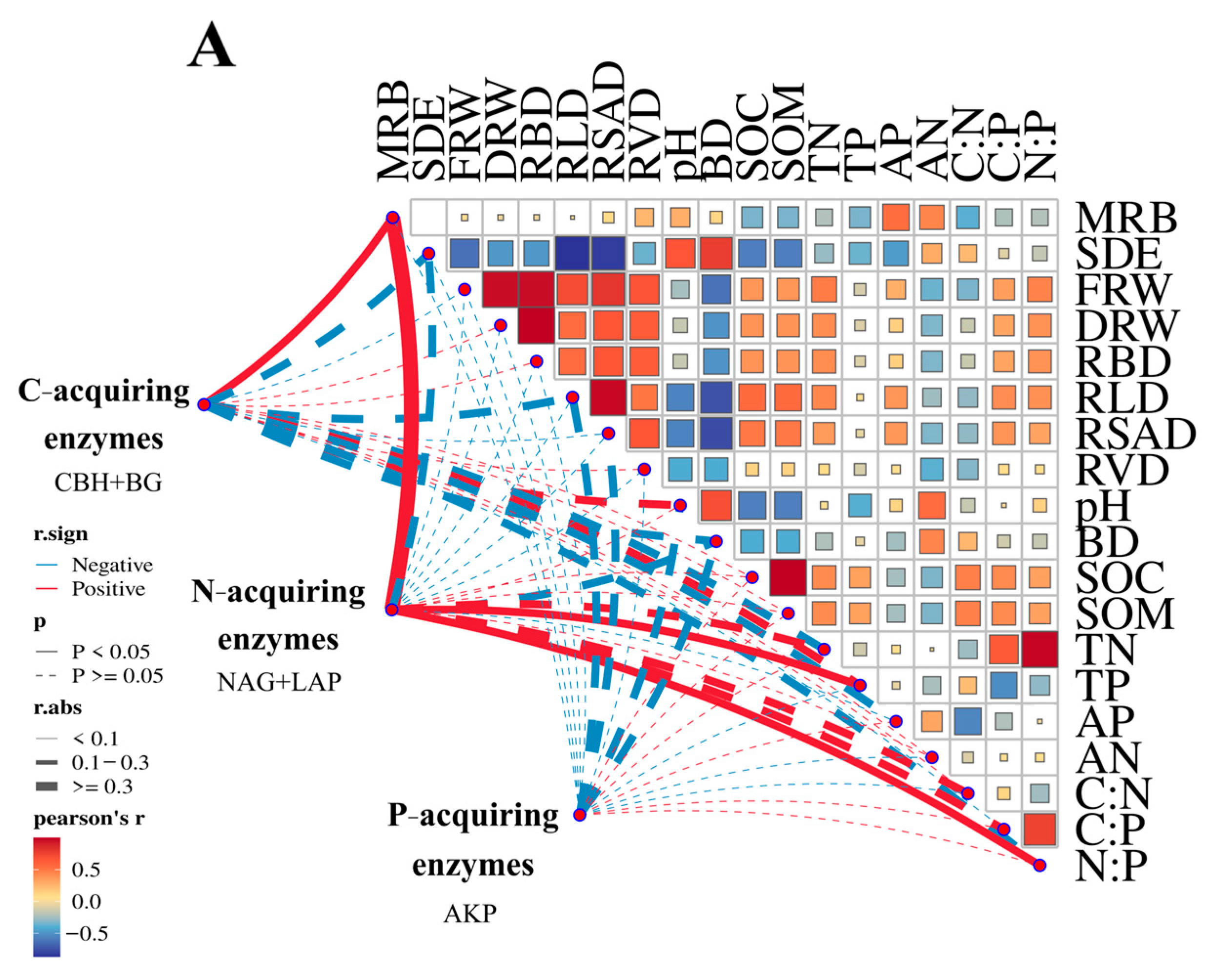

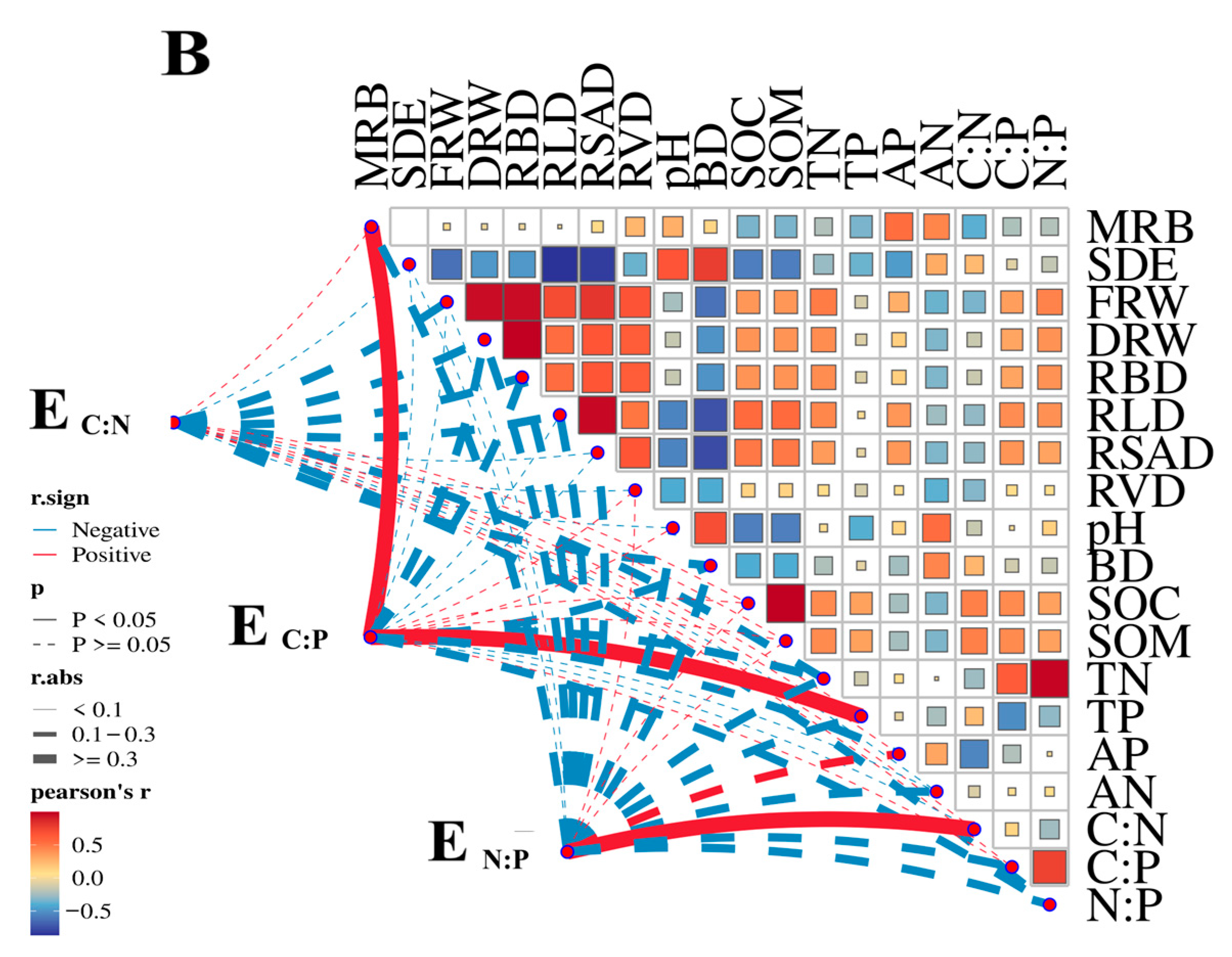

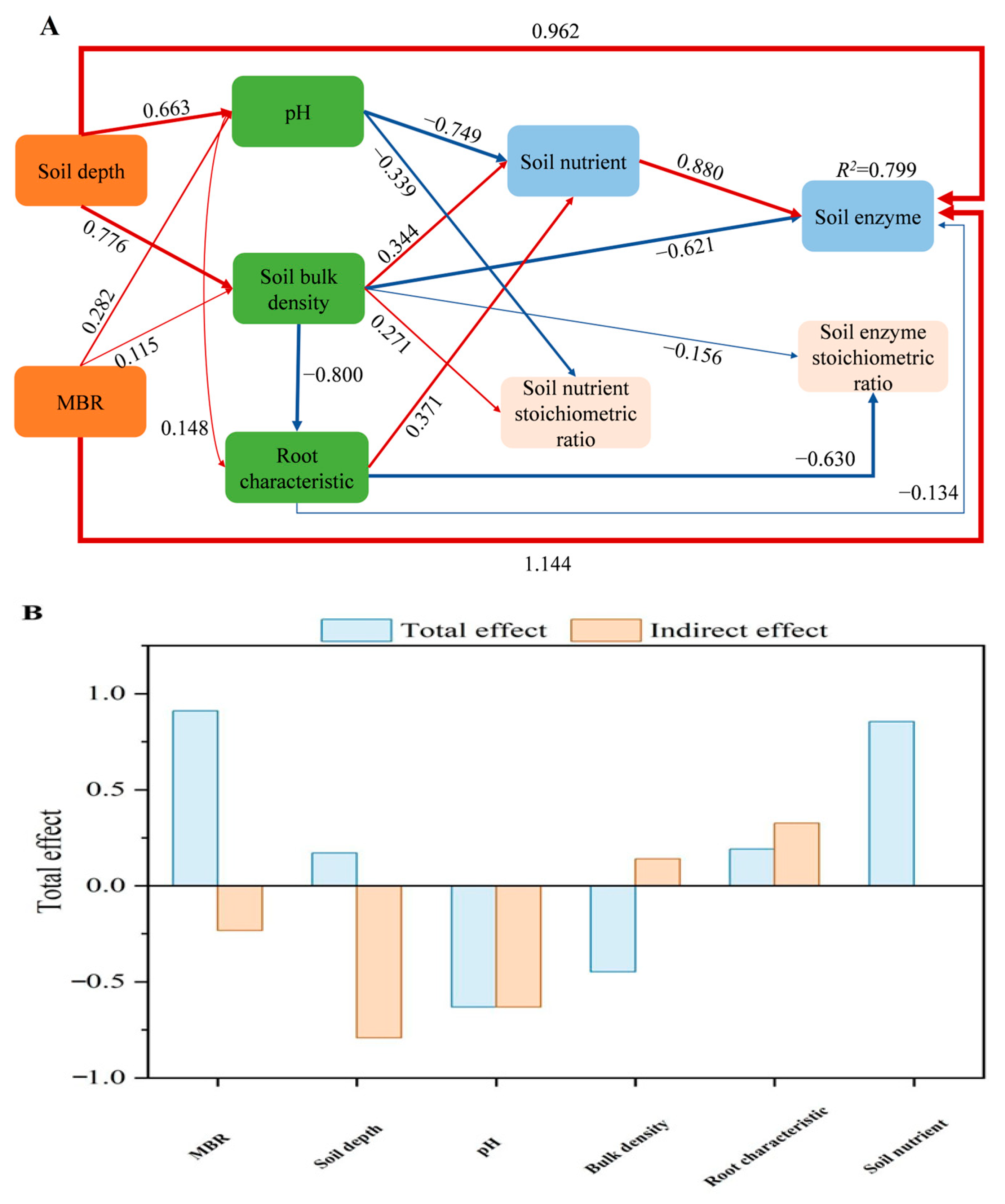

3.4. Linkage Between Soil Enzymes and Soil Nutrients

3.5. Indicators of Microbial Resource Limitation

4. Discussion

4.1. Response of Root Characteristics and Soil Nutrients to MRB

4.2. Response of Soil Enzyme Activities and Microbial Resource Limitations in the MRB

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Willis, J.L.; Sharma, A.; Shearman, T.M.; Varner, J.M.; Mckeithen, J. Longleaf and shortleaf pine seedling fire tolerance is more sensitive to shade than encroaching hardwood species. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 589, 122782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Li, Q.L.; Zhong, Z.K.; Huang, Z.Y.; Wen, X.; Bian, F.Y.; Yang, C.B. Determining changes in microbial nutrient limitations in bamboo soils under different management practices via enzyme stoichiometry. Catena 2023, 223, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.B.; Fang, Y.Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Ge, T.; Wang, Y.X.; Chang, S.X. Linking soil carbon availability, microbial community composition and enzyme activities to organic carbon mineralization of a bamboo forest soil amended with pyrogenic and fresh organic matter. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zou, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, C.J. Studies on the impact of aged microplastics on agricultural soil enzyme activity, lettuce growth, and oxidative stress. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Fan, L.; Wang, M.; Guo, J.; Bao, L.; Hui, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Qian, S.; Xu, X. Anthropogenic land-use driven changes in soil stoichiometry reduce microbial carbon use efficiency. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 392, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Ameen, A. Precipitation, elevation, and bamboo-to-tree ratio regulate soil organic carbon accumulation in mixed Moso bamboo forests. Plant Soil 2025, 514, 2923–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, I.J.; Copes-Gerbitz, K.; Parrott, L.; Rhemtulla, J.M. Dynamics in the landscape ecology of institutions: Lags, legacies, and feedbacks drive path-dependency of forest landscapes in British Columbia, Canada. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 4325–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zeng, Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, X. Functional characterization in Chimonobambusa utilis reveals the role of bHLH gene family in bamboo sheath color variation. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1514703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Mack, C.M.; Li, J. Fire severity strongly shapes soil enzyme activities in terrestrial ecosystems: Insights from a meta-analysis. Plant Soil 2025, 514, 2907–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Bao, W.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, F. Enzyme stoichiometry reveals microbial nitrogen limitation in stony soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Tuo, Y.F.; Chang, X.; Liang, J.P.; Yang, Q.L.; He, X.H. Characteristics of Forest Soil Enzyme Activities, Nutrient Restriction, and Physicochemical Properties at Different Altitudes and Their Seasonal Dynamics. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2025, 58, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Wang, W. The effect of soil depth on temperature sensitivity of extracellular enzyme activity decreased with elevation: Evidence from mountain grassland belts. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. Season-dependent effect of snow depth on soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity in a temperate forest in Northeast China. Catena 2020, 195, 104760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Min, X.; Li, Z.; Li, P. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Characteristics of Soil Enzymes in Pure and Mixed Forest Samples on the Loess Plateau of China. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2025, 188, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.J.; Tomback, D.F.; Seastedt, T.R.; Mellmann-Brown, S.J. Soil moisture regime and canopy closure structure subalpine understory development during the first three decades following fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 483, 118783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Dou, Y.; Wang, B.; Gunina, A.; Yang, Y.; An, S.; Chang, S.X. Soil stoichiometric imbalances constrain microbial-driven C and N dynamics in grassland. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonious, G.F.J. Duality of Biochar and Organic Manure Co-Composting on Soil Heavy Metals and Enzymes Activity. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, Z.; Guan, F.; Wan, Z. The influence of tree species on small scale spatial soil properties and microbial activities in a mixed bamboo and broad-leaved forest. Catena 2024, 247, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.M.; Fan, S.H.; Yan, X.R.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Guan, F.Y. Relationships between stand spatial structure characteristics and influencing factors of bamboo and broad-leaved mixed forest. J. For. Res. 2020, 25, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, Y.; Chi, G. Removal of petroleum hydrocarbons from contaminated soils: Analyses of soil enzymes and microbial community evolution during phytoremediation using Suaeda salsa. Pedosphere 2025, 35, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sang, J.; Zou, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Xu, G.; Kim, D.G.; Denton, M.D.; Carmona, C.R.; Zhao, H. Impacts of conversion of cropland to grassland on the C-N-P stoichiometric dynamics of soil, microorganisms, and enzymes across China: A synthesis. Catena 2024, 246, 108456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladi, R.; Aliverdikhani, R.; Abdi, E. Linking root xylem anatomy to tensile strength: Insights from four broadleaved tree species in the Hyrcanian forests. Plant Soil 2024, 512, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Manzoni, S.; Moorhead, D.L.; Richter, A.; Elser, J. Carbon use efficiency of microbial communities: Stoichiometry, methodology and modelling. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawarkar, A.D.; Shrimankar, D.D.; Manekar, S.C.; Kumar, M.; Garlapati, P.K.; Singh, L. Bamboo as a sustainable crop for land restoration in India: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.F.; Shi, P.J.; Hui, C.; Wang, F.S.; Liu, G.H.; Li, B.L. An optimal proportion of expansion broad-leaved forest for enhancing the effective productivity of moso bamboo. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Peng, S.L.; Shu, H.; Fu, X.; Ye, X.Y. Potential adaptive habitats for the narrowly distributed and rare bamboo species Chimonobambusa tumidissinoda J. R. Xue & T. P. Yi ex Ohrnb. under future climate change in China. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, H.; Zhang, W. Natural colonization of broad-leaved trees decreases the soil microbial abundance of Chinese fir plantation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 212, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yu, G.; Zhang, X.; He, N.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, N.; Jia, Y.; Wang, C. Soil enzyme activity and stoichiometry in forest ecosystems along the North-South Transect in eastern China (NSTEC). Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 104, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hong, Q.; Ji, N.; Wu, W.; Ma, L.J. Influences of different drying methods on the structural characteristics and prebiotic activity of polysaccharides from bamboo shoot (Chimonobambusa quadrangularis) residues. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulatoglu, A.O. Variation of nickel accumulation in some broad-leaved plants by traffic density. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, K.L.; Wang, Z.H.; Lenoir, J.; Shen, Z.H.; Chen, F.S.; Shrestha, N. Different range shifts and determinations of elevational redistributions of native and non-native plant species in Jinfo Mountain of subtropical China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Long, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, B.; Ren, P.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, X.J. Divergent assembly of soil microbial necromass from microbial and organic fertilizers in Chimonobambusa hejiangensis forest. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1291947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Q.; Sun, X. The behavior and mechanism of longitudinal liquid permeation in Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, J.; Pei, J.; Jiang, Y. Hydrochemical variations of epikarst springs in vertical climate zones: A case study in Jinfo Mountain National Nature Reserve of China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 63, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasu, P.; Opara, E.; Ellison, F.E.; Koblah, R.A.; Adjei-Mensah, B.; Anim-Jnr, A.S.; Attoh-Kotoku, V.; Kwaku, M. Valorising bamboo leaves for climate-smart livestock production: Nutritional profile, emission reduction, and farmer adoption in Ghana’s transitional zones. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2025, 11, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Wu, X.F.; Ruan, H.; Song, Y.Q.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.N.; Wang, D.L.; Wu, D.H. How does grassland degradation affect soil enzyme activity and microbial nutrient limitation in saline-alkaline meadow? Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 5863–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TS 22939:2019; Soil Quality—Measurement of Enzyme Activity Patterns in Soil Samples Using Fluorogenic Substrates in Micro-Well Plates. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Xiong, J.; Shao, X.; Li, N. Effects of land-use on soil C, N, and P stocks and stoichiometry in coastal wetlands dependent on soil depth and latitude. Catena 2024, 240, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Hu, D.Z.; Wang, Y. Influence of soil substrate availability and plant species diversity on soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity in a subalpine natural secondary forest. J. Soils Sediments 2025, 25, 1628–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tou, C.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Wanek, W.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L.; Wu, L.; Ma, Q. Plant litter decomposition is regulated by its phosphorus content in the short term and soil enzymes in the long term. Geoderma 2025, 457, 117283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S. Kinetic Parameters of Soil Enzymes and Temperature Sensitivity Under Different Mulching Practices in Apple Orchards. Agronomy 2025, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zheng, H.; Penuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Deng, D.; Cai, X.; Gao, D.; Nie, S.; He, Y. Shrub encroachment leads to accumulation of C, N, and P in grassland soils and alters C:N:P stoichiometry: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorich, E.G.; Yanni, S.F.; Qian, B.; Beare, M.H.; Curtin, D.; Tregurtha, C.; Ellert, B.H.; Janzen, H.H.J.G. Long-term retention of carbon from litter decay in diverse agricultural soils in Canada and New Zealand. Geoderma 2023, 437, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.; Urdaneta, F.; Cordoba, Y. Assessing bleached bamboo fibers as a hardwood replacement via kraft co-cooking for paperboard applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, W.J. Stimulatory effects of nutrient addition on microbial necromass C formation depend on soil stoichiometry. Geoderma 2025, 458, 117323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, F.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, Z.J. Bamboo-based agroforestry changes phytoremediation efficiency by affecting soil properties in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere in heavy metal-polluted soil (Cd/Zn/Cu). J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Y.; Wang, W.H.; Wei, G.R.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Ma, P.F. Genetic structure of a narrowly distributed species Chimonobambusa tumidissinoda in the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and its implications for conservation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 53, e03028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Li, Q.; Kou, Z.; Li, Y.J. The influence of soil depth and tree age on soil enzyme activities and stoichiometry in apple orchards. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ye, Y.; Ma, Q.; Guan, Q.; Jones, D.L. Variation in enzyme activities involved in carbon and nitrogen cycling in rhizosphere and bulk soil after organic mulching. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, B.W.T.; Van Zyl, L.J. The Environmental Light Characteristics of Forest Under Different Logging Regimes. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Fan, S.; Guan, F.; Yao, H.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of Spatial Structure and Homogeneity of Bamboo and Broad-Leaved Mixed Forest. Forests 2025, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MRB (%) | Soil Depth (cm) | Fresh Root Weight (g) | Dry Root Weight (g) | Root Biomass Density (g·m−3) | Root Length Density (mm·m−3) | Root Surface Area Density (cm2·m−3) | Root Volume Density (cm3·m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20% | 0–20 | 5.04 ± 3.48 a | 1.57 ± 0.47 a | 2 ± 0.59 a | 0.88 ± 0.75 a | 0.16 ± 0.14 a | 2.44 ± 2.13 a |

| 20–40 | 3.8 ± 5.02 a | 1.49 ± 2.13 a | 1.9 ± 2.71 a | 0.31 ± 0.24 a | 0.06 ± 0.04 a | 0.95 ± 0.51 b | |

| 40–60 | 0.86 ± 0.43 a | 0.21 ± 0.12 a | 0.26 ± 0.16 a | 0.15 ± 0.07 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.61 ± 0.26 b | |

| 20~40% | 0–20 | 26.99 ± 2.51 a | 9.03 ± 7.06 a | 11.51 ± 8.99 a | 1.89 ± 1.4 a | 0.42 ± 0.27 a | 7.4 ± 4.1 a |

| 20–40 | 9.91 ± 7.92 a | 3.13 ± 2.73 a | 3.98 ± 3.48 a | 1.26 ± 1.27 a | 0.3 ± 0.25 a | 5.87 ± 3.77 a | |

| 40–60 | 1.11 ± 0.72 a | 0.28 ± 0.23 a | 0.35 ± 0.29 a | 0.24 ± 0.28 a | 0.05 ± 0.05 a | 0.78 ± 0.72 b | |

| 40~60% | 0–20 | 11.6 ± 8.66 a | 2.95 ± 2.07 a | 3.75 ± 2.64 a | 1.62 ± 0.85 a | 0.42 ± 0.24 a | 8.76 ± 5.44 b |

| 20–40 | 22.99 ± 3.79 a | 10.15 ± 18.12 a | 12.94 ± 23.09 a | 0.71 ± 0.34 b | 0.27 ± 0.22 ab | 10.19 ± 13.35 a | |

| 40–60 | 0.89 ± 0.14 a | 0.39 ± 0.24 a | 0.5 ± 0.3 a | 0.27 ± 0.09 b | 0.06 ± 0.03 b | 1.22 ± 0.82 c | |

| 60~80% | 0–20 | 15.42 ± 3.56 a | 3.15 ± 2.61 a | 4.02 ± 3.33 a | 1.63 ± 1.22 a | 0.38 ± 0.3 a | 7.17 ± 5.98 b |

| 20–40 | 15.24 ± 12.10 a | 4.92 ± 4.04 a | 6.27 ± 5.14 a | 0.42 ± 0.14 a | 0.16 ± 0.04 a | 5.4 ± 2.76 b | |

| 40–60 | 4.66 ± 6.03 a | 1.38 ± 1.8 a | 1.75 ± 2.29 a | 0.23 ± 0.06 a | 0.1 ± 0.06 a | 12.25 ± 13.13 a | |

| >80% | 0–20 | 11.96 ± 3.96 a | 3.34 ± 1.37 a | 4.25 ± 1.74 a | 1.51 ± 0.8 a | 0.34 ± 0.18 a | 6.21 ± 3.4 a |

| 20–40 | 1.37 ± 0.61 b | 0.53 ± 0.24 b | 0.68 ± 0.31 b | 0.33 ± 0.17 b | 0.09 ± 0.04 b | 1.87 ± 0.97 b | |

| 40–60 | 0.49 ± 0.06 b | 0.11 ± 0.06 b | 0.14 ± 0.002 b | 0.12 ± 0.02 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 b | 0.5 ± 0.09 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, L.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, L.; Zeng, X.; Shen, L.; Gan, F.; Liang, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Qi, L. Effects of Bamboo Expansion on Soil Enzyme Activity and Its Stoichiometric Ratios in Karst Broad-Leaved Forests. Biology 2025, 14, 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121761

Tong L, Zeng Q, Chen L, Zeng X, Shen L, Gan F, Liang M, Chen L, Zhang X, Qi L. Effects of Bamboo Expansion on Soil Enzyme Activity and Its Stoichiometric Ratios in Karst Broad-Leaved Forests. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121761

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Long, Qingping Zeng, Lijie Chen, Xiaoying Zeng, Ling Shen, Fengling Gan, Minglan Liang, Lixia Chen, Xiaoyan Zhang, and Lianghua Qi. 2025. "Effects of Bamboo Expansion on Soil Enzyme Activity and Its Stoichiometric Ratios in Karst Broad-Leaved Forests" Biology 14, no. 12: 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121761

APA StyleTong, L., Zeng, Q., Chen, L., Zeng, X., Shen, L., Gan, F., Liang, M., Chen, L., Zhang, X., & Qi, L. (2025). Effects of Bamboo Expansion on Soil Enzyme Activity and Its Stoichiometric Ratios in Karst Broad-Leaved Forests. Biology, 14(12), 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121761