Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A drying duration of 24 hours at 60 °C significantly improved the physical and mechanical properties of mycelium-based composites made from empty fruit bunch (EFB) and kenaf fibers.

- EFB-based composites achieved the highest hardness (44.53 HA), while kenaf-based composites showed the highest water loss (67.00%) and shrinkage (50.70%). Extended drying minimized mold contamination and enhanced structural integrity, producing more durable and dimensionally stable composites.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Optimizing drying time is crucial to improve the strength and microbial resistance of mycelium-based composites. EFB and kenaf agricultural residues can be effectively utilized as sustainable raw materials to develop biodegradable and lightweight alternatives to polystyrene for eco-friendly.

Abstract

Empty fruit bunches (EFBs) and kenaf are two abundant sources of lignocellulosic resource agricultural waste with potential as substrates for mycelium-based composites (MBCs). These composites are lightweight, compostable, low-cost, and suitable for packaging applications. However, their performance is highly dependent on the type of lignocellulosic substrate and the processing conditions applied during production. Despite the promising availability of natural fibers, limited research has focused on the drying process that affects the quality of MBCs. This study investigates the effect of different drying times (12, 18, and 24 h) on the physical and mechanical properties of MBCS produced from EFB and kenaf substrates. Following a 20-day incubation period under controlled conditions, the composites were oven-dried and analyzed for mycelial colonization, density measurement, shrinkage, water loss, shore A hardness, impact resistance, and mold growth. The results demonstrated that a drying time of 24 h yielded the best overall performance. Moisture loss (67.00%) and shrinkage (50.70%) increased with longer drying times (24 h), particularly in kenaf-based composites. Extended drying minimized mold contamination and enhanced the structural integrity of the composites. Overall, EFB-based composites achieved the highest Shore A hardness (44.53 HA). These findings show that optimizing the drying time enhances the durability of MBCs, reinforcing their potential as sustainable, biodegradable alternatives to polystyrene and promoting the development of eco-friendly materials.

1. Introduction

The growing global environmental crisis driven by widespread plastic pollution and the depletion of non-renewable resources has prompted an urgent shift toward more sustainable material alternatives. Conventional packaging, such as polystyrene, are typically derived from non-renewable fossil-based resources and are major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation [1]. The global polystyrene market volume is projected to be 41.09 million tonnes by 2025 and is expected to grow approximately 62.33 million tonnes by 2034 [2]. It is estimated that between 74 and 199 million tonnes of plastic waste are currently present in the ocean [3]. Each year, plastic pollution claims the lives of 100,000 marine species, impacting ecosystems from coastal shores to the deepest parts of the ocean [4].

In response to these environmental threats, innovation in eco-friendly materials has accelerated, positioning mycelium-based composites (MBCs) as a compelling sustainable alternative [5]. Mycelium, the vegetative network of fungi, has attracted considerable interest for its natural ability to bind lignocellulosic fibers, making it a promising candidate for the development of sustainable composites. These composites are lightweight and biodegradable, utilizing abundant and renewable agricultural waste. As such, their ability to recycle waste and biodegrade efficiently enhances their role in promoting resource efficiency and waste valorization [6,7]. The mycelium packaging market is projected to be valued at USD74 million in 2023 and is anticipated to grow to 187 million by 2033 [8]. Consequently, incorporating MBCs into packaging could help reduce the reliance on polystyrene. By aligning with the principles of a circular economy, MBCs support the global transition toward environmentally responsible material solutions and reduce reliance conventional fossil-based materials [9].

Naturally, plant fibers have three major components known as cellulose, lignin and hemicellulose. Cellulose is the primary structural component of the plant cell wall, providing mechanical strength [10,11]. It is composed of long and complex polysaccharide chains consisting of β-D-glucose units linked by β-1,4 glycosidic (C-O-C) bonds [12]. Hemicellulose, a branched polysaccharide made up of sugar monomers with shorter chains and diverse conformations, coexists with cellulose and lignin in the cell wall [13]. In contrast, lignin is a complex polymer built from three phenylpropane units, interconnected by ether (α-O-4; β-O-4) and carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds [14]. The proportions and interactions of these three components largely determine the physicochemical behavior of natural fibers, making them suitable candidates for various bio-composite applications. Among the various source of lignocellulosic fiber sources, empty fruit bunch (EFB) and kenaf have received growing interest due to their abundance and favorable composition.

EFB are by-products of the palm oil industry, primarily derived from the processing of fresh fruit bunches into palm oil. EFB constitutes a biomass resource, with millions of tonnes generated annually in palm oil-producing countries like Indonesia and Malaysia [15]. Possessing a fibrous and lignocellulosic composition, EFB fibers have garnered considerable attention as cost-effective and sustainable raw materials for composite development [16]. EFB fiber structure is typically coarse, short, and irregular, containing about 20.6–33.5% cellulose, 23.7–65.0% hemicellulose, and 14.1–30.5% lignin [17]. The relatively high lignin content offers natural stiffness and water resistance, which can be advantageous in producing rigid or semi-rigid packaging materials [18]. EFB fiber is known for its high moisture retention due to its porous structure which contains pore size averaging around 0.7 μm [19,20].

Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus), in addition to EFB, has emerged as a new natural fiber source of interest. Kenaf can reach heights of up to 6 m within a typical growing season of 3 to 4 months, making it one of the fastest-growing fiber crops globally [21,22,23]. It is known to yield between 10 and 20 tonnes per hectare, depending on cultivation practices and environmental conditions [24]. It is primarily valued for its long bast fiber s from the outer bark and short core fibers from the stem. Kenaf contains 45–57% cellulose, 21.5% hemicellulose, 8–13% lignin and 3–5% pectin [25]. This composition contributes to its good recyclability, low density levels, superior mechanical strength, flexibility, and improved compatibility with binding matrices, making it suitable for producing lightweight and biodegradable packaging products [26,27]. Furthermore, kenaf exhibits lower moisture retention, which not only facilitates faster drying but also reduces the likelihood of microbial degradation, thereby contributing to an extended shelf life [28,29].

Drying time is an important parameter in the production of MBCs as it facilitates the evaporation of excess water, which is integral not only for mechanical properties but also for the mycelium’s growth and binding ability. Inadequate moisture removal creates a conducive environment for mold growth, which compromises the material’s structural integrity over time [30]. Additionally, dimensional instability is a prominent consequence of improper drying. When MBCs absorb moisture, they can swell, leading to warping and cracking as they dry unevenly. The resultant dimensional instability directly threatens the performance of these materials [31,32]. On the other hand, excessive drying is prone to undesirable shrinkage, internal stresses, and surface cracking. Importantly, over-drying affects the adhesive functionality of the mycelium, weakening the interfacial bonding within the composite and reducing mechanical strength and stability. In our previous study, MBCs were dried for 24 h at different oven temperatures (40 °C, 60 °C, and 80 °C) [33]. Among these, 60 °C exhibited the highest flexural strength (0.11 MPa), flexural modulus (4.15 GPa), and maximum impact load (635.80 N), confirming superior mechanical performance. In contrast, lower temperatures (40 °C) resulted in incomplete drying and potential regrowth, while higher temperatures (>80 °C) damaged hyphae, degraded lignocellulosic components, and caused shrinkage and warpage due to rapid water loss. Similar findings have been reported in studies highlighting that drying at moderate temperatures (50–70 °C) enhances strength and dimensional stability of MBCs while avoiding structural damage [34,35]. Inappropriate drying conditions may lead to inefficiencies in energy usage during production, stressing the importance of optimizing drying processes to strike a balance between achieving adequate moisture removal and preventing damage to the material’s structure [36]. For optimal performance, achieving the right balance of drying time and temperature is essential in which excessive drying can lead to brittleness, while insufficient drying may hinder the formation of a solid composite [37]. Recent studies have emphasized the role of drying parameters in influencing the performance of MBCs. Mandliya et al. [38] investigated vacuum drying of Pleurotus eryngii mycelium and mentioned that drying rate is affected by both drying temperature and drying duration. They also reported that prolonged drying could impede moisture migration, thereby reducing drying efficiency. Complementing this, Vašatko et al. [39] examined the use of beech sawdust in combination with two mycelium strains known as Pleurotus ostreatus and Ganoderma lucidum for building applications. The samples were dehydrated in a drying cabinet that was maintained at 40 °C until they were completely dry. Nevertheless, the precise duration of the drying process was not disclosed. Elsacker et al. [40] also created a bacterial cellulose–hemp substrate that was supplemented with 10 wt.% Trametes versicolour mycelium spawn. The mixture was incubated at 26 °C for 10 days, followed by an additional 2-day incubation to ensure uniform colonization on the surfaces in contact with the container. Although the drying method was not explicitly described, the samples were subsequently compressed using an Instron 5900R equipped with an integrated heating oven. Meanwhile, Mardijanti et al. [41] demonstrated the production of MBCs by mixing 50% cocopith with 27% wood powder and inoculating the mixture with Ganoderma lucidum spawn. Although drying at approximately 110 °C has been recommended to halt further mold growth without compromising composite stability, the optimal drying duration remains unaddressed. In agreement with above findings, Krsmanović et al. [42] concluded that species selection and optimized drying times are crucial for ensuring the functional viability of MBCs.

Despite these advancements, limited studies have focused on the effect of drying time on MBCs made from natural fibers such as EFB and kenaf, specifically tailored for biodegradable packaging applications. Furthermore, natural fiber composites were found to be more cost-effective and lightweight. Since EFB fibers and kenaf fibers possess distinct lignocellulosic structures and moisture retention capacities, their interaction with mycelium during drying is expected to differ significantly from other substrates. This study addresses that gap by investigating the effects of different drying times (12, 18 and 24 h) on the physical properties and mechanical performance of mycelium composites reinforced with EFB and kenaf. The novelty of this research lies in its focus on lignocellulosic agricultural residues as sustainable reinforcement, and its application-specific analysis of drying time effects to develop eco-friendly packaging materials that align with circular economy principles. Since polystyrene packaging contributes significantly to persistent leachate and environmental contamination, the adoption of sustainable material substitutes is anticipated to minimize these ecological challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Mycelium-Based Composites

Prior to substrate preparation, the mixture of 80 wt.% kenaf/EFB, 19 wt.% wheat bran and 1 wt.% calcium carbonate (CaCO3) were prepared. Wheat bran was added as a source of nutrition for the growth of mushrooms and CaCO3 as the mineral source. The substrate was then put in a polypropylene bag and sterilized in a steamer at 100 °C for 4 h to eliminate any competing microorganisms that might hinder mycelial development. Once the sterilized substrate cooled down to room temperature, mycelium liquid spawn was homogeneously distributed in polypropylene bags. The amount of mycelium used for inoculation was 10% of the weight of the sterilized substrate in which 10 mL of liquid spawn was incorporated into 500 g of substrate. The acrylic molds were then cleaned with ethanol and manually pressed to fill with the inoculated substrate. The molded composites were transferred for incubation for 20 days at 23 °C and 60% relative humidity using an incubator equipped with a cooling pad, exhaust fan, and water pump known as i-Mistroom. After the incubation period, the composites were dried at 60 °C for 12, 18, or 24 h using a Protech GOV-50D oven (Protech Systems Pte Ltd., Singapore).

2.2. Testing and Characterizations of Mycelium-Based Composites

Following a 20-day incubation period, a series of tests were performed to evaluate the sample’s physical and mechanical characteristics. In this research work, density analysis was conducted to assess the compactness and structural integrity of the sample using BK-DME300 S electronic densimeter, with three readings recorded and averaged for each sample.

Meanwhile, shrinkage was determined by measuring the initial volume of each sample (100 mm × 100 mm × 30 mm) and comparing it with the final volume post-drying, as shown in Equation (1). All volume measurements were repeated three times per condition.

Water loss was measured to quantify the reduction in moisture content from the sample during the drying process, following ASTM D644 [43]. The drying efficiency is important since it influences the material’s physical integrity, microbial resistance, and long-term stability. The water loss was assessed by weighing each sample before and after drying to determine moisture loss using Equation (2). This test was replicated three times for each drying duration.

Concurrently, visual inspection was employed to conduct visual observations of mycelial colonization and mold growth, which were subsequently documented using a digital camera (Model: SM-A235F/DS, Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Suwon, Republic of Korea) under standardized lighting conditions.

In terms of mechanical properties, Shore A hardness was measured using a Mitutoyo HH-300 Series durometer (Type A), with 15 readings collected per sample across designated tapping points. Hardness testing was conducted to evaluate the surface resistance and material stiffness of the MBCs after drying. Another mechanical test was performed in accordance with ASTM D5276 to evaluate impact resistance [44]. This test assessed the ability of the MBCs to withstand sudden forces and was designed to replicate real-world handling and shipping conditions. The ability of MBCs to absorb energy without cracking shows their toughness and practical usability under mechanical stress. In this testing, square samples with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm were securely clamped before subjected to a Dynatup 8250 drop-weight impact testing machine. A 3.69 kg load was dropped from a height of 0.19 m, and the maximum load capacity was recorded and analyzed. All impact tests were conducted in triplicate. Due to limited time and material availability at the time of testing, EFB-based composites were not included in the impact and mold growth evaluations, and these tests were conducted exclusively on kenaf-based composites.

3. Results

3.1. Mycelial Colonization

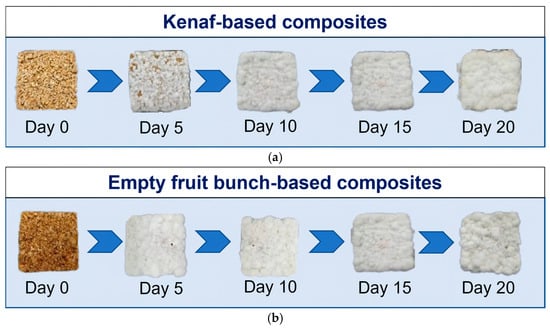

Mycelium growth was monitored over a 20-day incubation period to assess colonization behavior on two different lignocellulosic substrates, known as EFB and kenaf. Visual observations were recorded every five days to evaluate the rate and uniformity of mycelial spread across the substrate surface and throughout the matrix, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Progression of mycelium growth over 20-day incubation period for: (a) kenaf-based composites, and (b) empty fruit bunch-based composites.

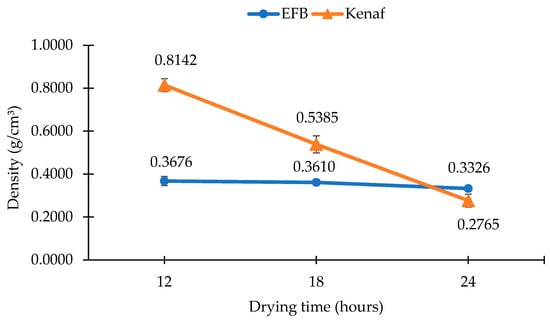

3.2. Density Measurement

Density decreased as the drying time increased for both EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites, as illustrated in Figure 2. A composite’s overall density is influenced by the density of the fiber. Kenaf-based composites had a higher density than EFB-based composites as a result of the higher fiber density of kenaf (1.62 g/cm3) in comparison to EFB (1.52 g/cm3) [45]. For kenaf-based composites, the highest density was observed at 0.8142 g/cm3 after 12 h of drying, followed by 0.5385 g/cm3 at 18 h, and 0.2765 g/cm3 at 24 h. For EFB-based composites, the corresponding densities were 0.3676 g/cm3, 0.3610 g/cm3, and 0.3326 g/cm3, respectively. This decreasing trend in density was attributed to the loss of internal moisture, which reduced the composite’s overall mass while the volume remained relatively constant. The kenaf (0.2765 g/cm3 until 0.8142 g/cm3) and EFB (0.3326 g/cm3 until 0.3676 g/cm3) composites had lower densities than solid polystyrene (1.04 g/cm3 to 1.10 g/cm3) [46], making them suitable for polystyrene replacement.

Figure 2.

Density measurement for EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites.

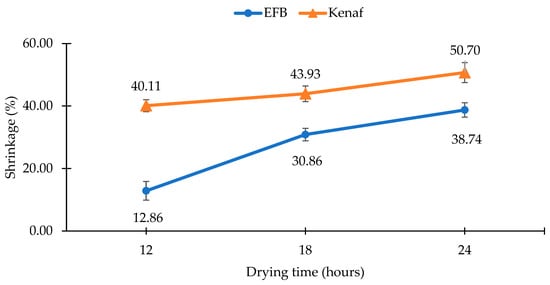

3.3. Shrinkage Measurement

As shown in Figure 3, kenaf-based composites exhibited greater shrinkage than EFB-based composites across all drying durations. The kenaf-based composites exhibited a shrinkage of 40.11% during the 12 h drying period, while the EFB-based composites exhibited a significantly lower shrinkage of 12.86%. For kenaf-based composites, the shrinkage increased to 43.93% and for EFB-based composites, it increased to 30.86% at 18 h. Both composites showed their highest shrinkage after 24 h of drying, with kenaf-based composites reaching 50.70% and EFB-based composites 38.74%.

Figure 3.

Shrinkage measurement for EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites.

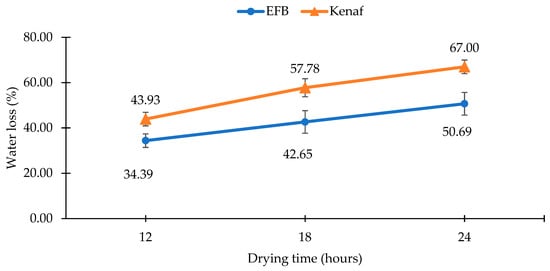

3.4. Water Loss Measurement

The results showed a consistent increase in water loss with longer drying durations for both EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites (Figure 4). Kenaf-based composites exhibited the highest water loss, with values of 43.93% at 12 h, 57.78% at 18 h, and 67.00% at 24 h. In comparison, EFB-based composites recorded water losses of 34.39%, 42.50%, and 50.69% at the corresponding drying times.

Figure 4.

Water loss measurement for EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites.

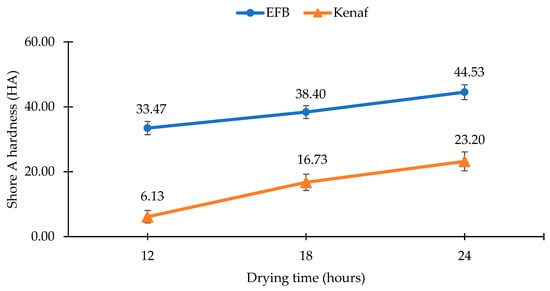

3.5. Shore A Hardness

Figure 5 shows the Shore A hardness measurement for EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites after 12, 18 and 24 h of drying times. Hardness increased with longer drying durations, with EFB-based composites consistently exhibiting higher hardness than kenaf-based composites across all time intervals. After 12 h of drying, EFB-based composites had a hardness of 33.47 HA, whereas kenaf-based composites had 6.13 HA. EFB reached 38.40 HA after 18 h of drying, while kenaf reached 16.73 HA. The highest hardness of 44.53 HA was achieved by EFB-based composites after 24 h of drying, in contrast to 23.20 HA for kenaf-based composites.

Figure 5.

Shore A hardness for EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites.

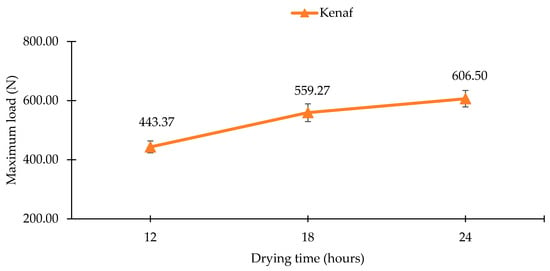

3.6. Impact Resistance

As shown in Figure 6, the maximum load for kenaf-based composites increased from 443.37 N at 12 h to 559.27 N at 18 h, and reached 606.5 N at 24 h.

Figure 6.

Maximum load for kenaf-based composites.

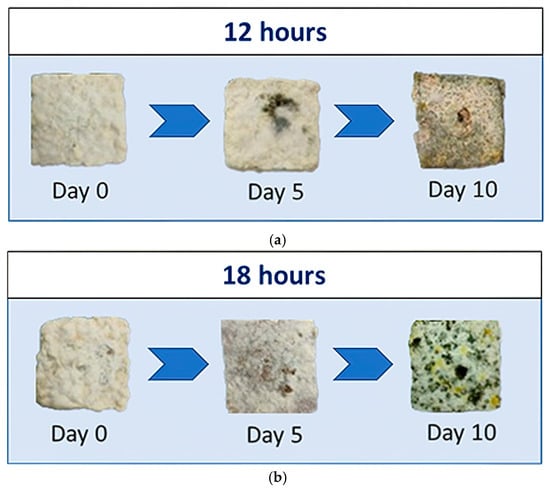

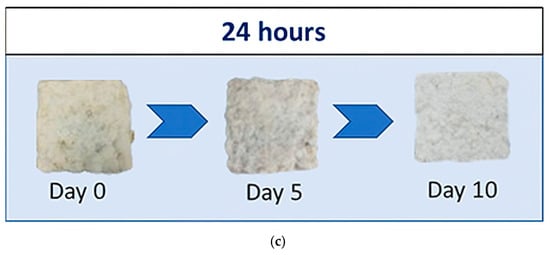

3.7. Mold Growth

Mold growth on kenaf-based composites was monitored over a 10-day period to evaluate post-drying microbial resistance at three different drying times (12, 18, and 24 h). Figure 7 depicts observations taken on days 0, 5, and 10 to assess mold risks under ambient conditions.

Figure 7.

Visual assessment of mold growth on kenaf-based composites over 10-day period following post-drying at different drying times: (a) 12 h, (b) 18 h, and (c) 24 h.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mycelial Colonization

Prior to colonization, kenaf fibers have a more compact structure and lower surface porosity than EFB fibers, which have a more open and fibrous architecture [47]. This structural difference suggests that EFB-based composites provide greater surface accessibility and internal voids that facilitate hyphal penetration of fungi, as fungi exploit pre-existing microstructures in substrates for enhanced colonization.

By Day 5, visible white mycelial threads were observed on the surface of both EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites, indicating initial colonization. Kenaf-based composites, on the other hand, colonized more slowly, most likely due to its denser fiber structure and lower moisture retention capacity. These properties may limit early hyphal penetration and microenvironmental humidity, which are required for spore germination and mycelial expansion. In contrast, the EFB-based composites demonstrated faster and more uniform colonization, likely owing to its more porous and fibrous architecture, which facilitates better aeration, and moisture distribution, supporting a faster and a more uniform colonization process [48]. The biochemical composition of EFB fiber which includes higher residual organic content and soluble sugars, further enhances nutrient availability for mold metabolism, thereby accelerating mycelial growth [49]. By Day 10, the formation of a denser and more interconnected mycelial network on EFB-based composites suggests a favourable biochemical interface between the fungal hyphae and the substrate, supporting sustained hyphal extension and cross-linking. At Day 15, the mycelium had substantially covered the entire surface area of most composites.

By Day 20, all composites had been fully colonized, allowing for the formation of a firm and white fungal network that encompassed both the substrate’s surface and interior. The observed interconnected network not only provides a structural advantage but also improves composite performance by improving stress transfer capabilities, which are critical for the integrity of mycelium-based materials [50].

After colonization, hyphal growth in kenaf-based composites became more surface-bound, with limited penetration into fiber bundles. This compact structure of kenaf limits bonding sites which may reduce its mechanical performance. In contrast, EFB-based composites showed deeper hyphal infiltration into pores and inter-fiber spaces, resulting in uniform and interconnected network. This contributes to improved stress transfer and composite strength.

4.2. Density Measurement

The density reduction of the kenaf-based composites was more pronounced than that of the EFB-based composites. The initial density of 0.8142 g/cm3 at 12 h decreased signifcantly to 0.2765 g/cm3 at 24 h, indicating substantial moisture evaporation and microstructural shrinkage. This can be attributed to the more rigid, densified and compact structure of kenaf fibers structure compared to EFB-based composites [51], which makes them prone to cracking and shrinkage upon dehydration, as well as to lower moisture retention capacity. Additionally, the inherent nature of kenaf fibers may render them more brittle after prolonged drying, further increasing void formation and leading to a significant reduction in density. In contrast, EFB-based composites demonstrated a more gradual and modest decrease in density across the same drying times. The relatively stable density values (0.3676 to 0.3326 g/cm3) suggest that the fibrous and more compressible structure of EFB, combined with its higher intrinsic water-holding capacity, allows it to retain more mass during drying. This is in line with a study performed by Ling et al. [52] who mentioned that the compressibility characteristics of EFB fibers enable them to adapt under load, absorbing and retaining mass during drying phases. Furthermore, the entangled and absorptive nature of EFB fibers may help preserve the composite’s microstructure, reducing the extent of shrinkage and porosity development compared to kenaf.

4.3. Shrinkage Measurement

Kenaf fibers, characterised by their relatively rigid and less entangled structure, are more susceptible to dimensional collapse as internal moisture evaporates. The rapid moisture loss during drying induces internal stresses that cannot be effectively redistributed within the kenaf matrix, resulting in greater volumetric contraction and structural compaction. Additionally, kenaf’s lower capacity for retaining bound water may accelerate the drying rate, further amplifying shrinkage. This explained the sharp increase in shrinkage from 40.11% at 12 h to 50.70% at 24 h, indicating progressive structural instability with prolonged dehydration. Meanwhile, the more compliant structure of EFB fibers is likely to contribute to a slower drying process, minimizing the occurrence of localized stress concentrations that lead to warping or collapse. Consequently, EFB-based composites demonstrate lower shrinkage, even for extended drying times. The values increased gradually from 12.86% (12 h) to 38.74% (24 h).

4.4. Water Loss Measurement

Kenaf fibers can hold more moisture within their cell walls and lumens due to their finer structure and compact morphology. During drying, the absorbed water is released, leading to higher shrinkage and overall mass loss. Additionally, the higher content of hydrophilic components, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, in kenaf fibers enhances water absorption. This is attributed to the hydroxyl groups (-OH) that interact with water molecules through hydrogen bonding, resulting in fiber swelling [53,54]. In contrast, EFB fibers possess a coarser, more irregular structure with lower packing density, which limits their ability to retain water. Consequently, EFB-based composites have less water loss and shrinkage during drying.

4.5. Shore A Hardness

Extended drying durations result in more effective removal of free and bound water, which leads to reduced plasticization of the mycelial matrix. As moisture content decreases, the composite structure becomes denser and less flexible [55], contributing to increased surface rigidity and hardness. This effect is more pronounced in EFB-based composites due to their inherently higher lignin content. Lignin, a complex aromatic polymer, imparts greater stiffness and rigidity of lignocellulosic fibers and enhances their interaction with fungal hyphae during colonization and bonding. The presence of lignin-rich fibers within the mycelium matrix is likely to promote stronger interfacial adhesion and a more rigid composite structure upon drying [56]. Hence, this structural stiffness likely contributes to greater surface hardness of EFB-based composite though the composite is overall lighter and less compact. Consequently, kenaf fibers contain lower lignin and higher cellulose content, resulting in a softer, more hydrophilic structure that retains flexibility even after drying. The reduced fiber stiffness, combined with higher shrinkage (as shown in earlier results), limits the development of a compact, load-bearing network, thereby yielding lower hardness. The comparatively weaker interfacial bonding between kenaf fibers and the mycelium matrix may also contribute to less efficient load transfer during indentation. In this research work, the EFB-based composites and kenaf-based composites exhibited lower hardness compared to polystyrene (95 HA) [57]. Nevertheless, additional processing techniques such as densification or surface coating, could enhance their hardness, potentially bringing it closer to that of polystyrene.

4.6. Impact Resistance

The improved performance is attributed to reduced moisture content, which increases composite stiffness and reduces energy absorption through internal dampening. This enhancement in impact resistance is primarily attributed to the reduction in moisture content, which contributes to increased stiffness and diminished energy dissipation via internal dampening mechanisms. Extended drying facilitates more effective mechanical interlocking and bonding between the mycelial matrix and the lignocellulosic kenaf fibers. The resulting composite structure is denser and more cohesive, allowing it to withstand crack propagation and resist deformation under dynamic loading conditions.

4.7. Mold Growth

At Day 0, all composites, regardless of drying duration, showed a clean and whitish appearance. By Day 5, early signs of mold growth began to appear in the 12 h and 18 h dried composites with slight discolouration and visible black spots. In contrast, the 24 h composite still maintained a clean surface, indicating better mold inhibition. On Day 10, mold colonization became more pronounced in the 12 h and 18 h dried composites. The 18 h composite showed dense dark green and black spots, indicating active mold proliferation. However, the 24 h dried composite demonstrated significantly enhanced resistance to microbial colonization over the 10-day period. This can be attributed to more thorough dehydration, which not only reduces water activity below the threshold necessary for microbial growth, but may also contribute to thermal inactivation of latent spores. The progressive mold growth observed on the 12 h and 18 h dried mycelium-based composites (MBCs), as opposed to the 24 h composites, can be attributed to insufficient moisture removal during the shorter drying durations. Residual moisture retained within the composite matrix likely created a favourable microenvironment for spore germination and hyphal development once exposed to ambient air. Furthermore, shorter drying times may not have been sufficient to inactivate or eliminate all mold spores that were introduced during fabrication or post-handling.

5. Conclusions

Among the tested conditions, the 24 h drying times at 60 °C yielded the most favorable results, producing MBCs with lower moisture content, enhanced hardness, higher impact resistance, and complete resistance to post-drying mold regrowth. Extending the drying duration beyond this point is unlikely to improve performance and negatively impact the material integrity.

The type of substrate used has a significant impact on composite behavior during drying, implying that drying protocols should be adapted to the material used. Kenaf-based composites showed greater shrinkage and water loss due to their porous structure, lower lignin content and reduced fiber interlocking, making them more susceptible to dimensional changes during drying compared to the denser and lignin-rich fiber structure of EFB-based composites. Therefore, optimizing drying times is essential for improving the mechanical strength and long-term stability of MBCs.

These findings show that agricultural residues like EFB and kenaf have the potential to be used as sustainable raw materials in bio-composites. This study contributes to the development of long-lasting, biodegradable alternatives to traditional plastics by identifying optimal drying conditions. The results provide practical insights into tailoring processing protocols to different substrates, highlighting the importance of material-specific approaches for scaling up MBC production.

6. Future Research

Further studies should investigate the integration of hybrid substrates, the influence of varying fungal strains, and the use of advanced drying techniques (e.g., vacuum or freeze-drying) to further enhance composite performance. In addition, incorporating scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and complementary imaging techniques can provide better correlation between the microstructure and the mechanical performance and stability of MBCs. Future studies should also employ advanced characterization techniques, such as Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR) or Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to distinguish between bound and free water fractions, and Micro-Computed Tomography (µCT) or Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) to analyze pore structure, thereby providing deeper insights into moisture behavior and its correlation with mechanical performance. Life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis will also be important to validate the environmental and economic feasibility of large-scale production. On an industrial scale, considerations such as energy-efficient drying systems and process automation are important for ensuring consistent quality and competitiveness of MBCs in packaging and other bio-based material applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y. and A.F.; Validation, K.M.H. and A.F.; formal analysis, H.A.A.R.; investigation, H.A.A.R.; resources, B.T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.A.R.; writing—review and editing, F.H., A.I. and A.F.; supervision, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Industrial Grant, 100-TNCPI/PRI 16/6/2 (060/2022).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the provision of materials and facilities provided by Fungitech Sdn Bhd and Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Pulau Pinang.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MBCs | Mycelium-based composites |

| EFB | Empty fruit bunch |

References

- Livne, A.; Wösten, H.A.B.; Pearlmutter, D.; Gal, E. Fungal mycelium bio-composite acts as a CO2-sink building material with low embodied energy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12099–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polystyrene Market to Reach 62.33 Million tons by 2034. 2025. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/polystyrene-market-volume-reach-62-161200926.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Plastic Pollution in the Ocean—2025 Facts and Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://www.rts.com/blog/plastic-pollution-in-the-ocean-facts-and-statistics/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Marine & Ocean Pollution Statistics & Facts 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.condorferries.co.uk/marine-ocean-pollution-statistics-facts (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Wattanavichean, N.; Phanthuwongpakdee, J.; Koedrith, P.; Laoratanakul, P.; Thaithatgoon, B.; Somrithipol, S.; Kwantong, P.; Nuankaew, S.; Pinruan, U.; Chuaseeharonnachai, C.; et al. Mycelium-based breakthroughs: Exploring commercialization, research, and next-gen possibilities. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2025, 5, 3211–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akromah, S.; Chandarana, N.; Eichhorn, S. Mycelium composites for sustainable development in developing countries: The case for Africa. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 8, 2300305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, D.; Tafesse, M.; Mondal, A.K. Mycelium-based composite: The future sustainable biomaterial. Int. J. Biomater. 2022, 2022, 8401528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycelium Packaging Market. 2025. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/mycelium-packaging-market (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Barta, D.-G.; Simion, I.; Tiuc, A.-E.; Vasile, O. Mycelium-based composites as a sustainable solution for waste management and circular economy. Materials 2024, 17, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Tang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Ding, Y. The cell wall functions in plant heavy metal response. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 299, 118326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, E. Cellulose: A comprehensive review of its properties and applications. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 11, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, H. Selectivity control of C–O bond cleavage for catalytic biomass valorization. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 9, 827680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathura, S.R.; Landázuri, A.C.; Mathura, F.; Andrade Sosa, A.G.; Orejuela-Escobar, L.M. Hemicelluloses from bioresidues and their applications in the food industry—Towards an advanced bioeconomy and a sustainable global value chain of chemicals and materials. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1183–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiukaitytė-Grojzdek, E.; Huš, M.; Grilc, M.; Likozar, B. Acid-catalysed α-O-4 aryl-ether bond cleavage in methanol/(aqueous) ethanol: Understanding depolymerisation of a lignin model compound during organosolv pretreatment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ng, W.-T.; Wu, J.-C. Isolation, characterization and application of a cellulose-degrading strain Neurospora crassa S1 from oil palm empty fruit bunch. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.-H.; Lim, Y.-T.; Kam, L.-W.; Sia, H.-T. Effects of adding silica fume and empty fruit bunch to the mix of cement brick. Indones. J. Comput. Eng. Des. 2021, 3, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiin, C.-L.; Ho, S.; Yusup, S.; Quitain, A.-T.; Chan, Y.-H.; Loy, A.-C.-M.; Gwee, Y.-L. Recovery of cellulose fibers from oil palm empty fruit bunch for pulp and paper using green delignification approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 290, 121797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.R.; Ramakrishna, G. Oil palm empty fruit bunch fiber: Surface morphology, treatment, and suitability as reinforcement in cement composites—A state of the art review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 6, 100144. [Google Scholar]

- Harahap, H.; Nasution, H.; Manurung, R.; Yustira, A.; Rashid, A.A. Physical characteristics of biodegradable pots from empty fruit bunches (EFB) and sawdust waste as planting media. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekala, M.S.; Kumaran, M.G.; Thomas, S. Oil palm fibers: Morphology, chemical composition, surface modification, and mechanical properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 66, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomple, B.M.; Jo, I.-H. Evaluation of forage productivity and nutritional value of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) at different fertilizer application amounts and different stages of maturity. J. Korean Soc. Grassl. Forage Sci. 2021, 41, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, N.; Paridah, M.T.; Jawaid, M.; Abdan, K.; Ibrahim, N.A. Potential utilization of kenaf biomass in different applications. In Agricultural Biomass Based Potential Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yirzagla, J.; Quandahor, P.; Yahaya, I.; Akanbelum, O.A.; Akologo, L.A.; Lambon, J.B.; Imoro, A.-W.M.; Santo, K.G. Growth, development and yield of kenaf as affected by planting dates and N fertilization. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayabari, D.A.G.; Ilham, Z.; Md Saad, N.; Ahmad Usuldin, S.R.; Norhisham, D.A.; Abd Rahim, M.H.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Cultivation strategies of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) as a future approach in Malaysian agriculture industry. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, C.; Arumugam, S.; Muthusamy, S. Mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of unsaturated polyester/chemically treated woven kenaf fiber/AgNPs@PVA hybrid nanobiocomposites for automotive applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 15298–15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfaleh, I.; Abbassi, F.; Habibi, M.; Ahmad, F.; Guedri, M.; Nasri, M.; Garnier, C. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: An eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adole, M.A.; Yatim, J.M.; Ramli, S.A.; Othman, A.; Mizal, N.A. Kenaf fibre and its bio-based composites: A conspectus. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 27, 297–329. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, T.S.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Shahar, F.S.; Basri, A.A.; Shah, A.U.M.; Sebaey, T.A.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Józwik, J.; Grzejda, R. Fatigue and impact properties of kenaf/glass-reinforced hybrid pultruded composites for structural applications. Materials 2024, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, S.C.; Tan, C.P.; Nyam, K.L. Microencapsulation of refined kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) seed oil by spray drying using β-cyclodextrin/gum arabic/sodium caseinate. J. Food Eng. 2018, 237, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, T.G.C. Fabrication and characterization of mycelium-based composites from Lentinus squarrosulus and Pleurotus ostreatus with improved physico-mechanical properties for versatile applications. Proc. Conf. Transdisc. Res. Eng. 2024, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, A.; Vieira, F.; Pecchia, J.; Gürsoy, B. Three-dimensional printing of living mycelium-based composites: Material compositions, workflows, and ways to mitigate contamination. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeraphantuvat, T.; Jatuwong, K.; Jinanukul, P.; Thamjaree, W.; Lumyong, S.; Aiduang, W. Improving the physical and mechanical properties of mycelium-based green composites using paper waste. Polymers 2024, 16, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrahnoor, A.; Hishamuddini, A.D.N.; Yusoff, H.; Koay, M.Y.; Maideen, N.C.; Fohimi, N.A.M.; Boey, T.Z. Influence of drying temperature in the oven on physical, morphology and mechanical properties of mycelium composite. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2025, 33, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Mautner, A.; Luenco, S.; Bismarck, A.; John, S. Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: A critical review. Mater. Des. 2020, 187, 108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Brancart, J.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Mechanical, physical and chemical characterisation of mycelium-based composites with different types of lignocellulosic substrates. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezer, E.; Uçar, E.; Gümüşkaya, E. Physical and mechanical properties of mycelium-based fiberboards. Bioresources 2024, 19, 3421–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Meher, M.K.; Poluri, K.M. Fabrication and characterization of bioblocks from agricultural waste using fungal mycelium for renewable and sustainable applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandliya, S.; Vishwakarma, S.; Mishra, H. Modeling of vacuum drying of pressed mycelium (Pleurotus eryngii) and its microstructure and physicochemical properties. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašatko, H.; Gosch, L.; Jauk, J.; Stavrić, M. Basic research of material properties of mycelium-based composites. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Damsin, B.; Wylick, A.; Peeters, E.; Laêt, L. Mechanical characteristics of bacterial cellulose-reinforced mycelium composite materials. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardijanti, D.; Megantara, E.; Bahtiar, A.; Sunardi, S. Turning the cocopith waste into myceliated biocomposite to make an insulator. Int. J. Biomater. 2021, 2021, 6630657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsmanović, N.; Mišković, J.; Novaković, A.; Karaman, M. An evaluation of the fundamental factors influencing the characteristics of mycelium-based materials: A review. J. Process. Energy Agric. 2024, 28, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D664; Standard Test Method for Moisture Content of Paper and Paperboard by Oven Drying. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1999.

- ASTM D5276-19; Standard Test Method for Drop Test of Loaded Containers by Free Fall. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Anuar, N.I.S.; Zakaria, S.; Kaco, H.; Hua, C.C.; Chunhong, W.; Abdullah, H.S. Physico-mechanical, chemical composition, thermal degradation and crystallinity of oil palm empty fruit bunch, kenaf and polypropylene fibres: A comparative study. Sains Malays. 2018, 47, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poly, P.V.C. Exploring the Physical Properties and Applications of Polystyrene. 2025. Available online: https://www.polypvc.com/news/Exploring-the-Physical-Properties-and-Applications-of-Polystyrene.html (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Isworo, Y.; Kim, G.-M.; Jeong, J.-W.; Jeon, C.H. Evaluation of torrefied EFB and kenaf combustion characteristics: Comparison study between EFB and kenaf based on microstructure analysis and thermogravimetric methods. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7094–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, M.; Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Abu Bakar, A. Mechanical performance of oil palm empty fruit bunches/jute fibres reinforced epoxy hybrid composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 7944–7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, I.; Kudori, S.N.I.; Ismail, H. Effect of partial replacement of kenaf by empty fruit bunch (EFB) on the properties of natural rubber latex foam (NRLF). BioResources 2019, 14, 9375–9391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoder, K.A.; Krümpel, J.; Müller, J.; Lemmer, A. Effects of environmental and nutritional conditions on mycelium growth of three Basidiomycota. Mycobiology 2024, 52, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, F.; Jawaid, M.; Paridah, M.T.; Naveen, J. Characterization of hybrid oil palm empty fruit bunch/woven kenaf fabric-reinforced epoxy composites. Polymers 2020, 12, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, J.H.; Lim, Y.T.; Kam, L.W.; Sia, H.T. Utilization of oil palm empty fruit bunch in cement bricks. J. Adv. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, F.; Jawaid, M.; Md Tahir, P. Mechanical performance of oil palm/kenaf fiber-reinforced epoxy-based bilayer hybrid composites. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayu, R.S.; Khalina, A.; Harmaen, A.S.; Zaman, K.; Isma, T.; Liu, Q.; Ilyas, R.A.; Lee, C.H. Characterization study of empty fruit bunch (EFB) fibers reinforcement in poly(butylene) succinate (PBS)/starch/glycerol composite sheet. Polymers 2020, 12, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrahnoor, A.; Ahmad Sazali, N.-A.; Yusoff, H.; Zhou, B.-T. Effect of beeswax and coconut oil as natural coating agents on morphological, degradation behaviour, and water barrier properties of mycelium-based composite in modified controlled environment. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 196, 108763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutetaki, M.E.; Mpalaskas, A.C. Natural fiber-reinforced mycelium composite for innovative and sustainable construction materials. Fibers 2024, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vian, W.-D.; Denton, N.-L. Hardness comparison of polymer specimens produced with different processes. ASEE IL-IN Sect. Conf. Purdue Univ. 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).