Abstract

This review explores various mechanical coating techniques, with a specific emphasis on ball milling for coating metal balls. Mechanical coatings play a crucial role in enhancing material properties such as wear resistance, durability, and functionality across various industries. Among these methods, ball milling stands out for its cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and ability to produce uniform coatings. This paper comprehensively discusses the principles, mechanisms, and process parameters influencing the efficiency of ball milling, including milling time, speed, and material properties. Additionally, advancements in nanostructured coatings, in situ coating techniques, and the challenges of contamination and scalability are examined. Future directions involve automation, real-time monitoring, and AI-driven optimization for improved performance. The findings aim to provide valuable insights for researchers and industries seeking to optimize mechanical coating processes.

1. Introduction

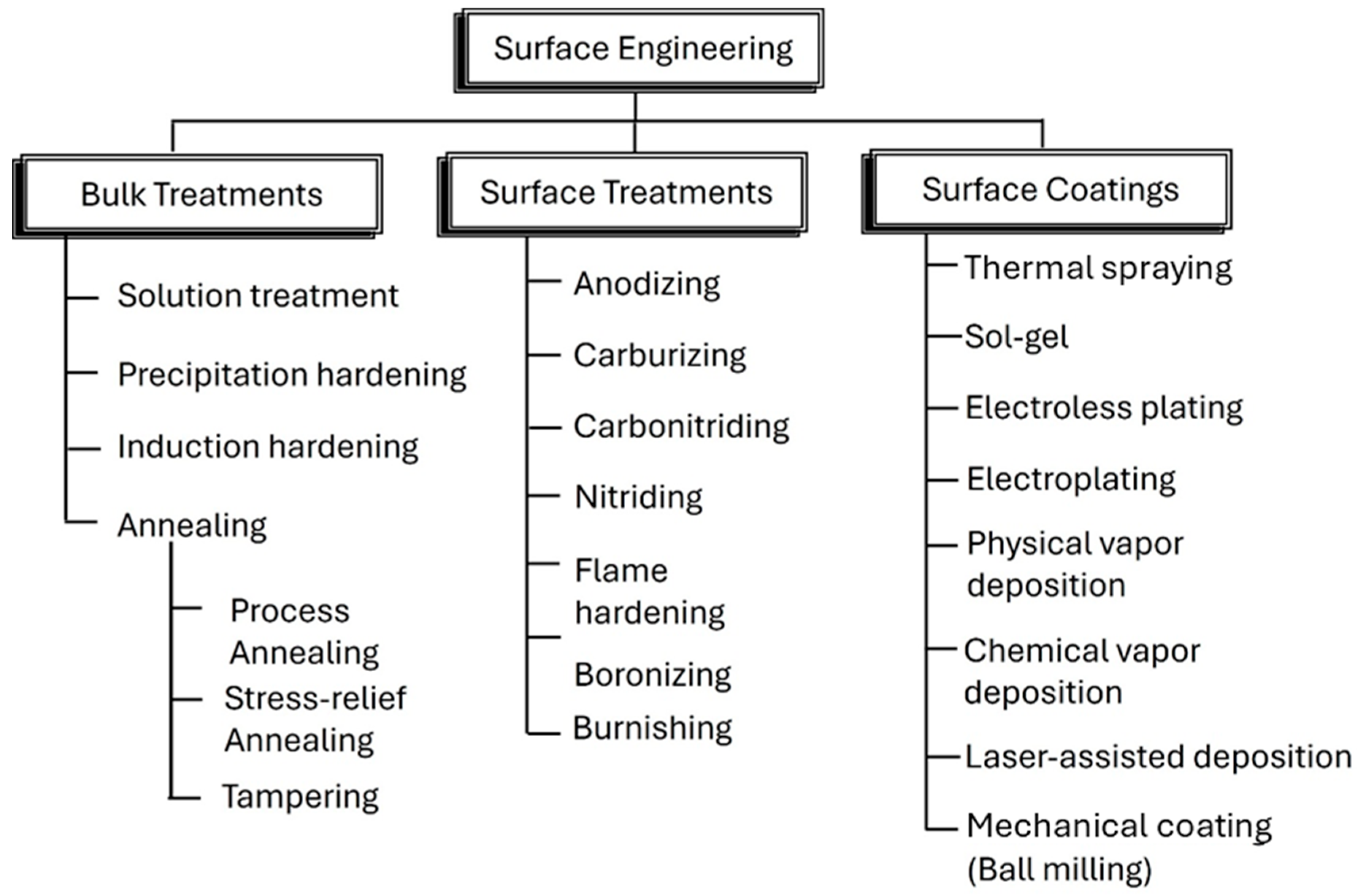

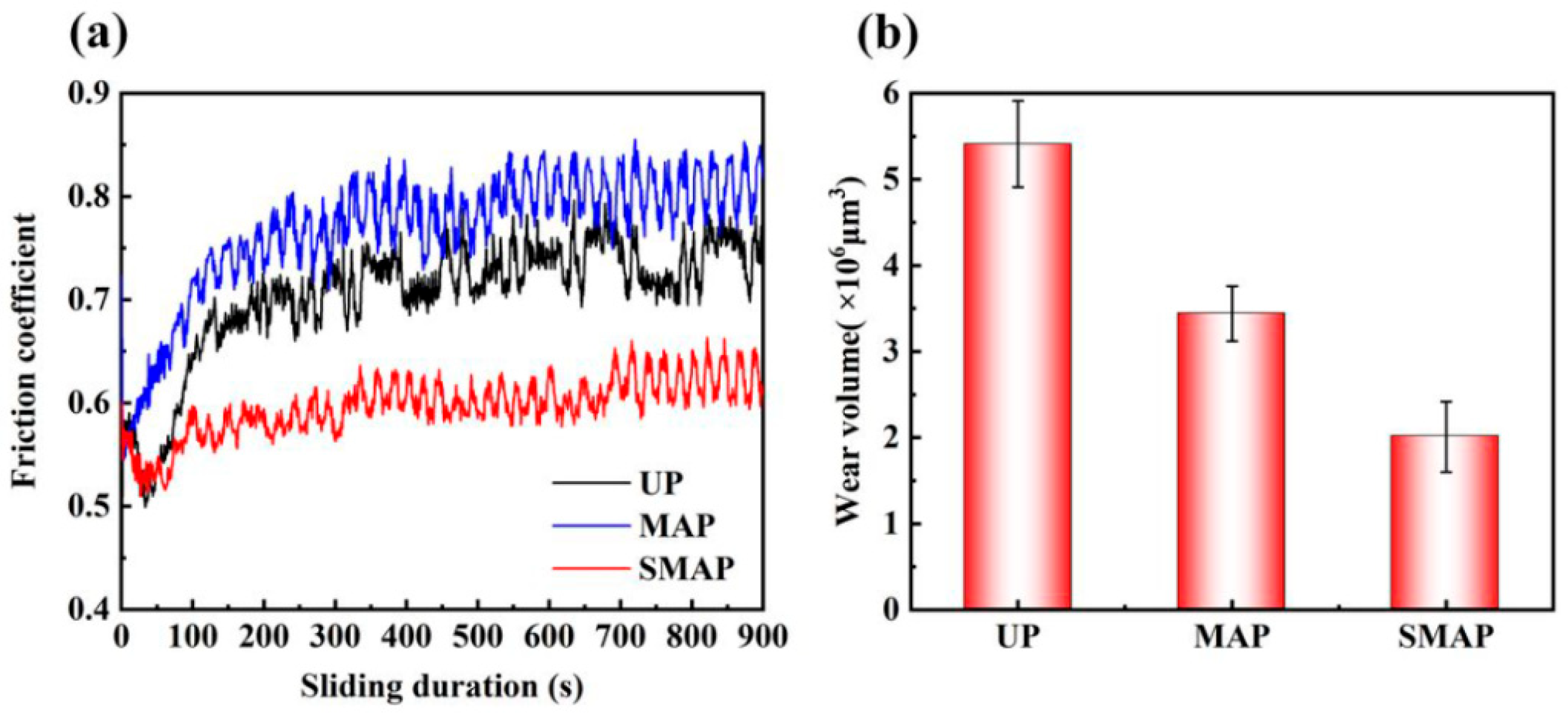

Surface engineering and coatings of powders are methods used to coat particles and enhance their surface properties. This is performed to improve the functional properties of materials, including wear resistance, corrosion resistance, and mechanical strength. The particle’s surface is significantly modified to reach these goals, which is why a huge proportion of the total cost of the production process is dedicated to the coating step. Since “simple mixing or blending” is insufficient to produce appropriate coating layer characteristics for relevant applications, many techniques have been developed to control the surface’s properties through the coating steps, including mechanical operations, with the lowest functional cost [1,2,3,4]. Traditional coating methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD), physical vapor deposition (PVD), and electroplating have limitations related to cost, complexity, and environmental concerns. Mechanical coating methods, particularly ball milling, offer a more sustainable and cost-effective alternative.

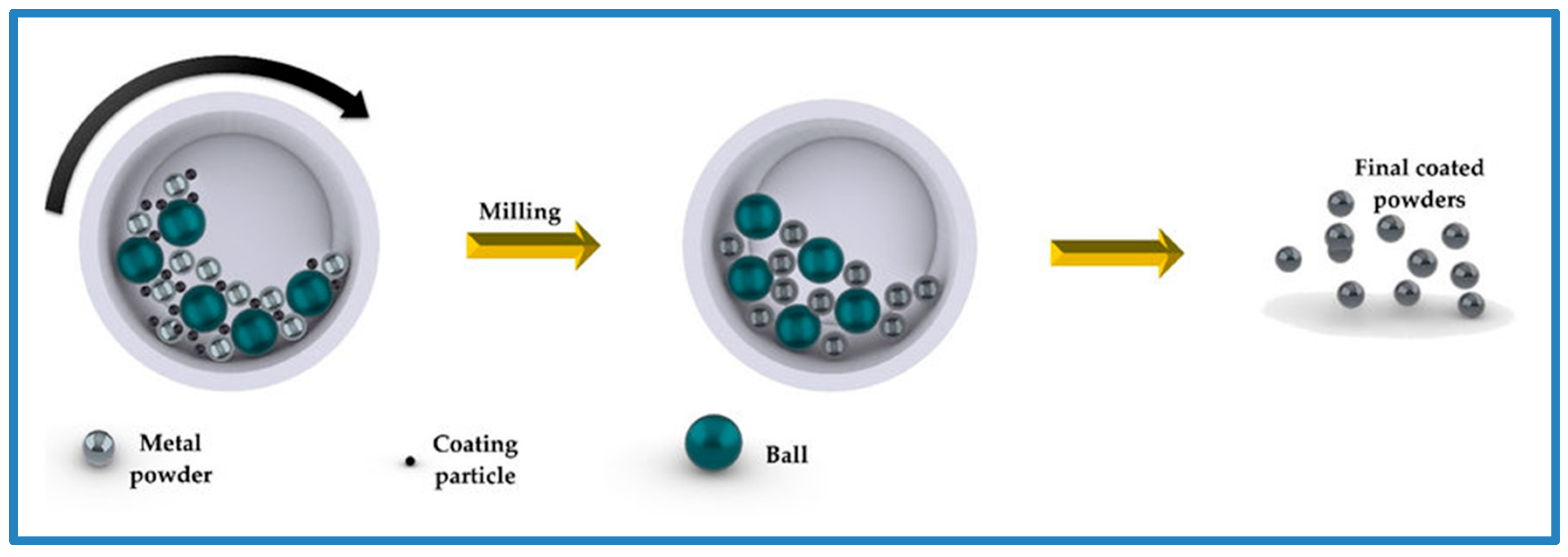

Mechanical coating is emerging as an efficient and cost-effective process for coating surfaces, especially for powder particles (Figure 1). Optimization is based on the conditions of mechanical coating, the intensity and the energy of the mechanical forces applied to the coating particles, as well as the balls used for the operation. When the coating operations are directly applied to the product’s surface, the operation is called external mechanical coating (EMC). Correspondingly, “Internal Using Mechanical Coating” is applied if the operation is performed inside the product. The mechanical coating can handle various shapes of the body, such as particulate or flat bodies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Figure 1.

List of various surface engineering treatments.

The novelty of this review lies in explicitly addressing several underexplored gaps in the literature. While prior reviews have broadly introduced mechanical coating techniques (MCTs), limited attention has been given to a comparative analysis of these techniques, especially highlighting the distinct advantages and limitations of ball milling. Furthermore, although challenges such as contamination control and scalability are well recognized, they have not been systematically analyzed within a unified framework. Another critical gap addressed here is the integration of AI-driven process optimization and real-time monitoring approaches, which remain largely absent in discussions of mechanical coating. By framing these aspects within the Energy–Structure–Property relationship, this review not only synthesizes existing knowledge but also provides a forward-looking perspective that connects process parameters to coating performance and industrial scalability.

Therefore, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanical coating method, with emphasis on ball milling, and its applications across various industrial fields.

1.1. Overview of Mechanical Coating Techniques (MCTs)

Mechanical coating can be applied using various techniques, each offering distinct advantages depending on the application. These methods include powder immersion coating, where the substrate is submerged inside the fluidized powder particles [9]. This method has several advantages, such as producing uniform coating layers, especially on complex-shaped objects, and is often a quicker and more effective substitute for conventional liquid coating techniques. In addition to the powder immersion method, other alternative MCTs are available and can be utilized to attain diverse results. These methods include fluidized bed coating (solid particles are suspended in a fluidization chamber with a controlled gas flow), centrifugal coating (uses centrifugal forces to distribute coating material evenly), air-jet coating (a high-speed air stream carries the coating particles to the substrate), and ball milling (utilizes mechanical energy from milling balls to apply coatings in a controlled manner) [3,4,7,9,10,11]. Each method has distinct benefits and can be customized to fulfill certain coating requirements.

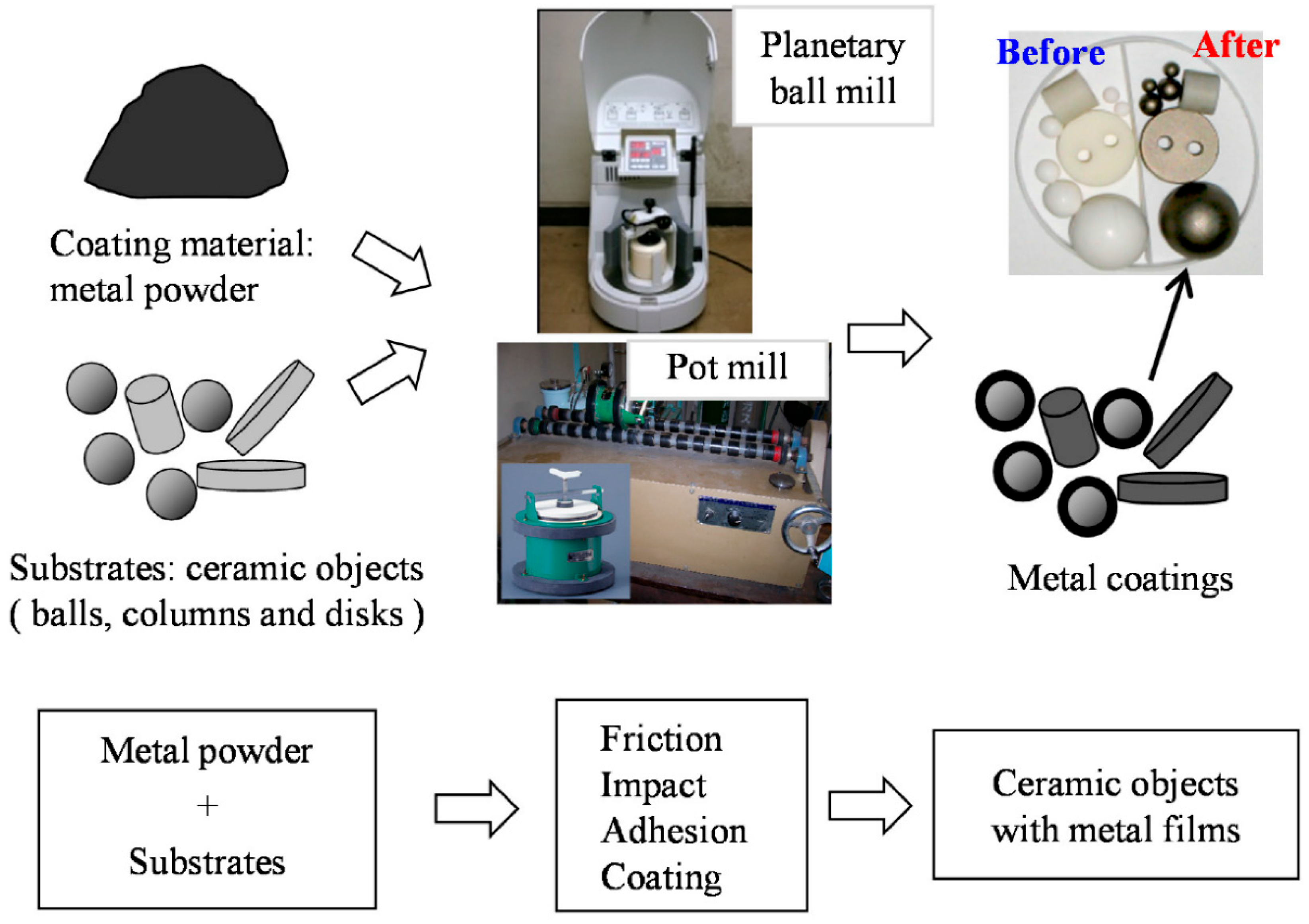

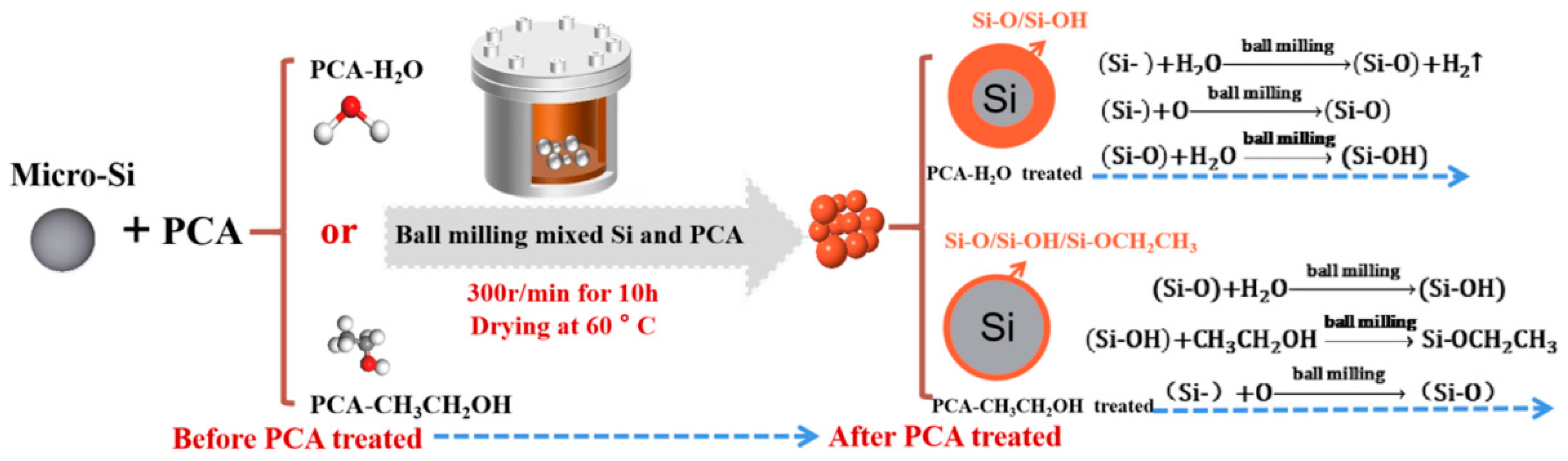

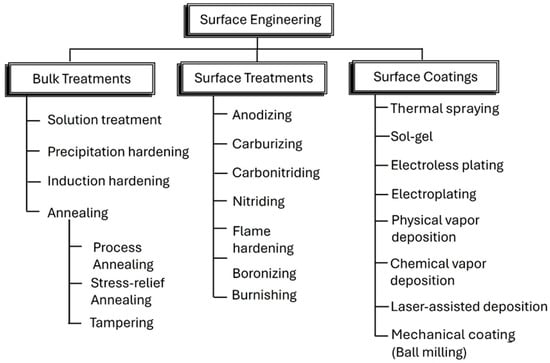

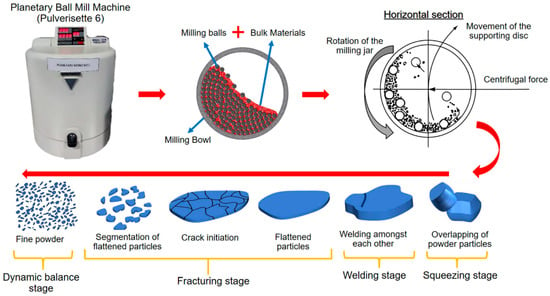

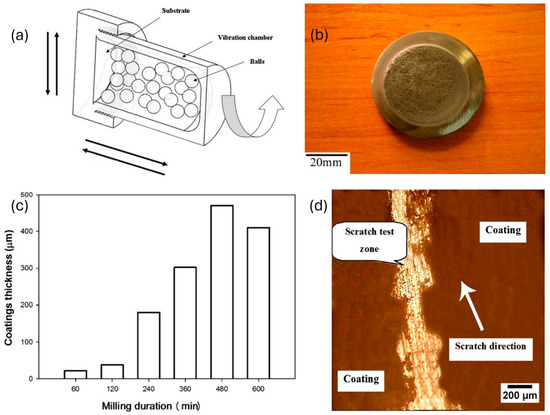

Of the different kinds of mechanical coating methods, the ball milling method (Figure 2) is the most useful and widely used in industrial applications [12]. The effectiveness of the ball milling method is highly dependent on several critical parameters, which determine the energy input, coating quality, and reproducibility. Among these, milling speed, ball-to-powder ratio (BPR), milling time, and the size and material of the milling media are the most influential [13,14,15]. For example, variations in rotational speed directly affect the collision energy and frequency, thereby influencing coating adhesion and particle refinement [16,17]. Similarly, an optimized BPR is essential to balance sufficient energy transfer while avoiding excessive cold welding or contamination [18,19]. Milling time determines the extent of particle deformation and alloying, while the selection of milling media and process control agents (PCA) significantly impacts contamination levels and surface purity [13,14,20,21,22].

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the MCTs for various substrates of different shapes using the ball milling method. Adapted with permission from ref. [12] Copyright 2015 Coatings.

The importance of process parameters in ball milling is further underscored by experimental evidence. For instance, in the synthesis of nano-sized amorphous colemanite, systematic variations in milling time were shown to directly alter both the crystal structure and thermal properties of the resulting material [22]. Prolonged milling progressively transformed crystalline colemanite into an amorphous phase, which was accompanied by a significant reduction in crystallite size and an increase in specific surface area. These structural changes not only modified the thermal stability of the product but also demonstrated how milling time can act as a critical lever to tune phase transitions and functional properties [15,20]. Such findings emphasize that what may initially appear to be a simple parameter, such as milling duration, actually governs fundamental material transformations and ultimately dictates performance in downstream applications.

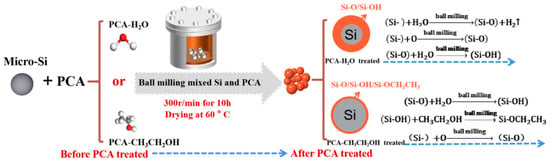

A parallel insight comes from nanosized ulexite, where the role of process control agents was investigated in detail [23]. Here, the type and concentration of PCA were found to profoundly influence particle morphology, degree of agglomeration, and contamination levels. Specifically, insufficient PCA addition led to severe cold welding and irregular particle growth, whereas excessive PCA inhibited effective energy transfer, resulting in incomplete refinement [19,22,24]. The optimal PCA balance minimized contamination while maintaining high milling efficiency, thereby demonstrating that surface chemistry and coating integrity can be directly controlled through careful additive selection [19,22,24]. These results highlight the dual role of PCAs not only as mechanical aids to reduce cold welding, but also as chemical agents that can subtly alter the interfacial characteristics of milled powders. Consequently, both milling time and PCA composition emerge as decisive parameters whose interplay determines whether mechanical coating produces uniform, stable, and application-ready surfaces.

Therefore, precise control and systematic optimization of these parameters are indispensable for achieving consistent coating performance across different applications [14,25].

This is due to its advantages, which include simple operation, low cost, uniformly coating complex surfaces, and the absence of heating cracks (unlike other coating techniques like CVD). The ball mill is the most utilized blending tool and can be categorized as an effective solution [3,7,10,26]. Ball milling for mechanical coating includes balls that directly improve both the particles’ textures and blend powders with effective shape change [3,4,7,10,26]. The ball mill contains grinding vessels and a PCA (balls/impeller), and both components affect the product of the ball mill. The working handle of the ball milling system for performing the process is mostly achieved by changing the balls. The duration of the ball milling method varies depending on the thickness and composition of the coated layers, as well as the extent of surface coverage. These factors can impact the efficiency and effectiveness of the ball milling process [9,26,27,28].

The interior of the grinding vessels and the substance being crushed usually comprise a softer layer, while the grinding balls, made from tougher materials, are frequently coated by employing a variety of MCTs. This safeguards them against wear and tear, prolonging their lifespan and ensuring optimal efficiency. Such MCTs include, but are not limited to, PVD, CVD, electroplating, and thermal spraying. Each technique presents distinct advantages and characteristics, enabling manufacturers to select the most suitable method for coating the grinding balls based on their specific requirements. With these advanced techniques at their disposal, manufacturers can enhance the performance and longevity of grinding balls, thus improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the crushing process [29,30]. The success of mechanical coating heavily relies on the wheel or container that facilitates the movement of balls/rollers. These components are crucial in ensuring uniform and effective coverage throughout the coating process. By carefully designing and optimizing these supporting components, the efficiency and effectiveness of the coating process can be significantly improved [9,27,29].

1.2. Significance of Mechanical Coating Using Ball Milling Processes

In industrial sectors, there is a tremendous demand for fabricating innovative coatings, which can be a very effective modification method to improve the functionality and performance of materials. The majority of modern industrial coatings are applied using CVD, plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD), PVD, electroplating, anodizing, sol–gel coating, etc. [11,31,32,33]. However, these methods have several deficiencies in practice. Most of these techniques use a vacuum, which may incur high costs and require a very clean environment. Furthermore, there are inherent material limitations when dealing with corrosive environments. The bonding between the coating and the substrate in these conditions tends to be significantly weaker compared to the mechanical bonding achieved through other methods [11,31,32,34,35].

Therefore, understanding the advantages of utilizing mechanical coating in the industry is essential for achieving success and maintaining a competitive edge. MCTs, such as ball milling, are some of the most effective methods for creating a stronger mechanical bond [26]. This mechanical treatment provides coating products with very high adhesion strength, due to increased energy between the interface coating and substrate as a result of defects and increasing the surface area, while decreasing the strain energy of the system and interfacial energy between the two phases [3,4,7]. Consequently, the properties depend mainly on the type and composition of the intermetallic compounds formed as a function of the material system of the coating and substrate, which can be developed through the design of the coating method. Based on the aforementioned factors, MCTs lead to significant enhancements in material properties and extend the lifespan of components by applying protective coatings, thus enhancing wear resistance. In addition to substantial improvements in mechanical properties (hardness, tensile strength, and durability), the thermal and electrical conductivity properties of materials are also improved [6,9,29,36]. Moreover, this technique is considered one of the most cost-effective and efficient methods with the ability to tailor the coating thickness, composition, and properties to meet specific industrial requirements.

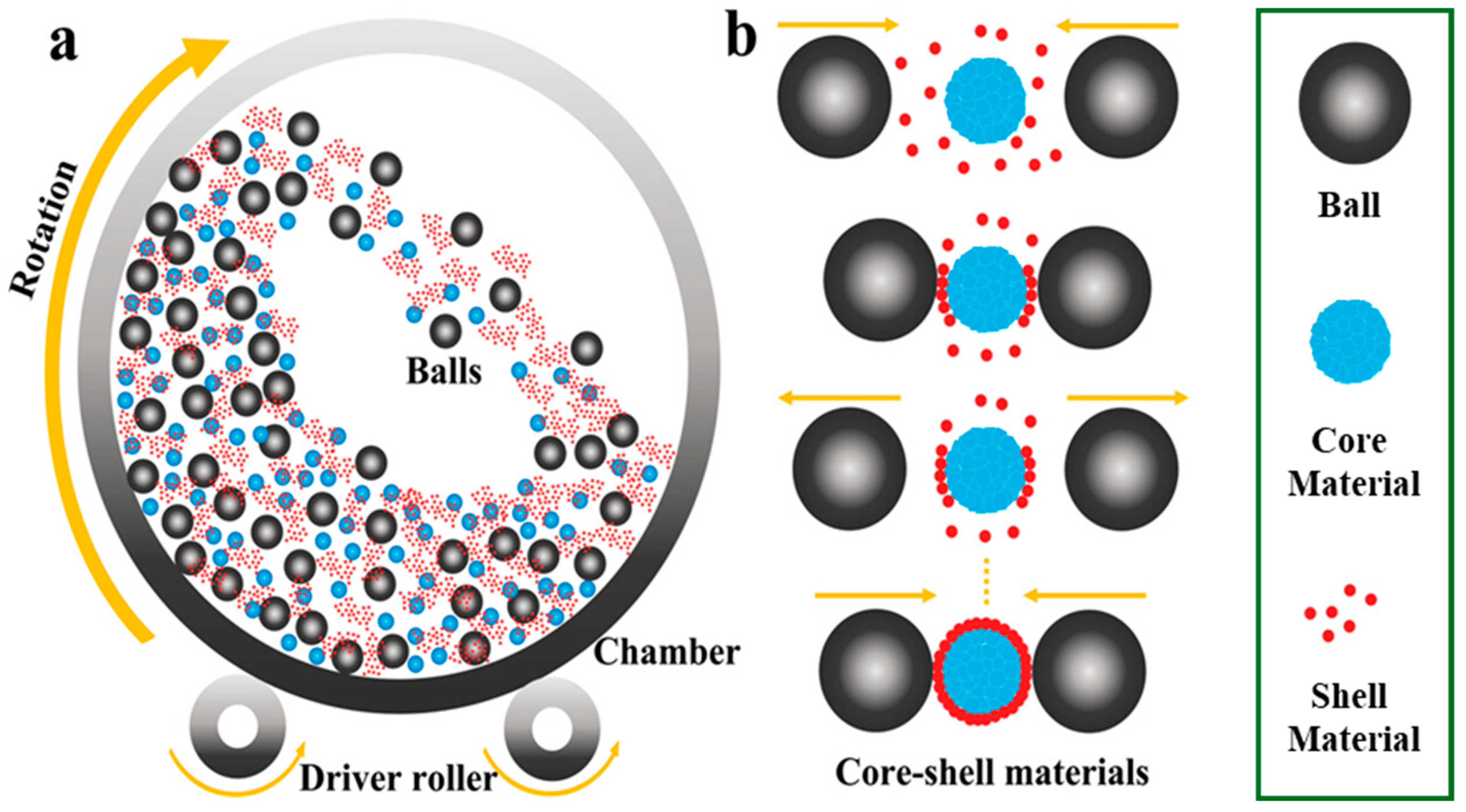

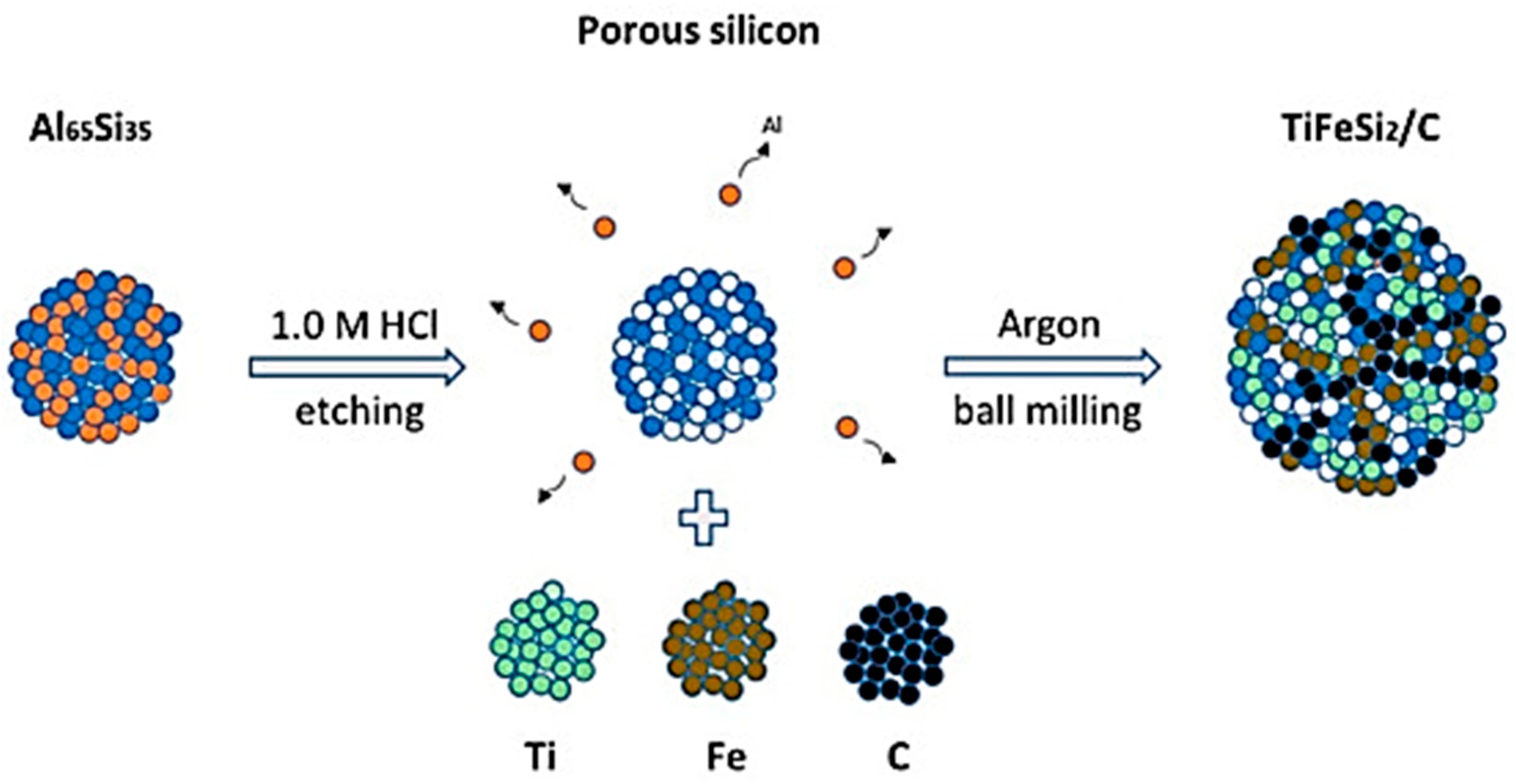

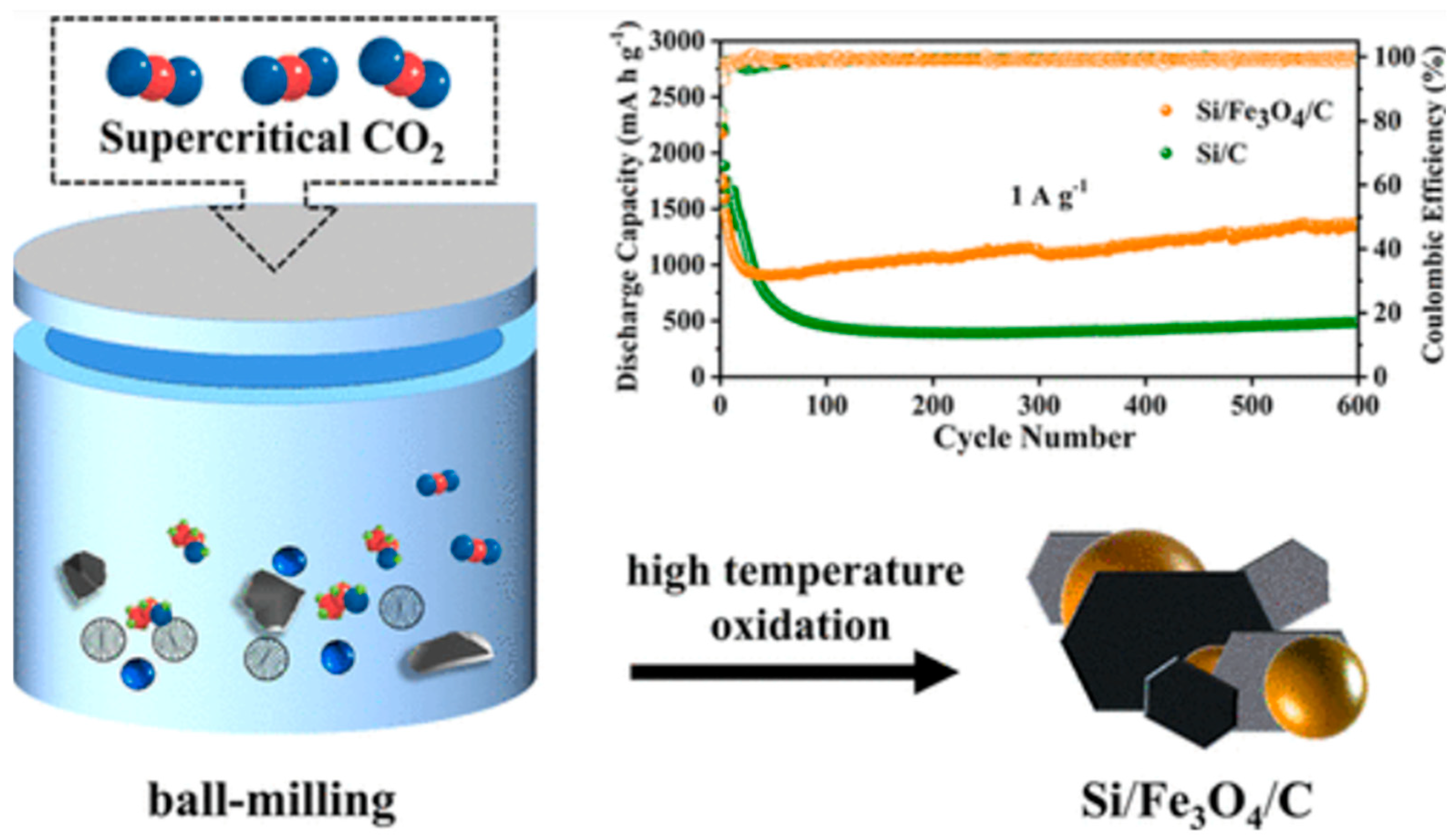

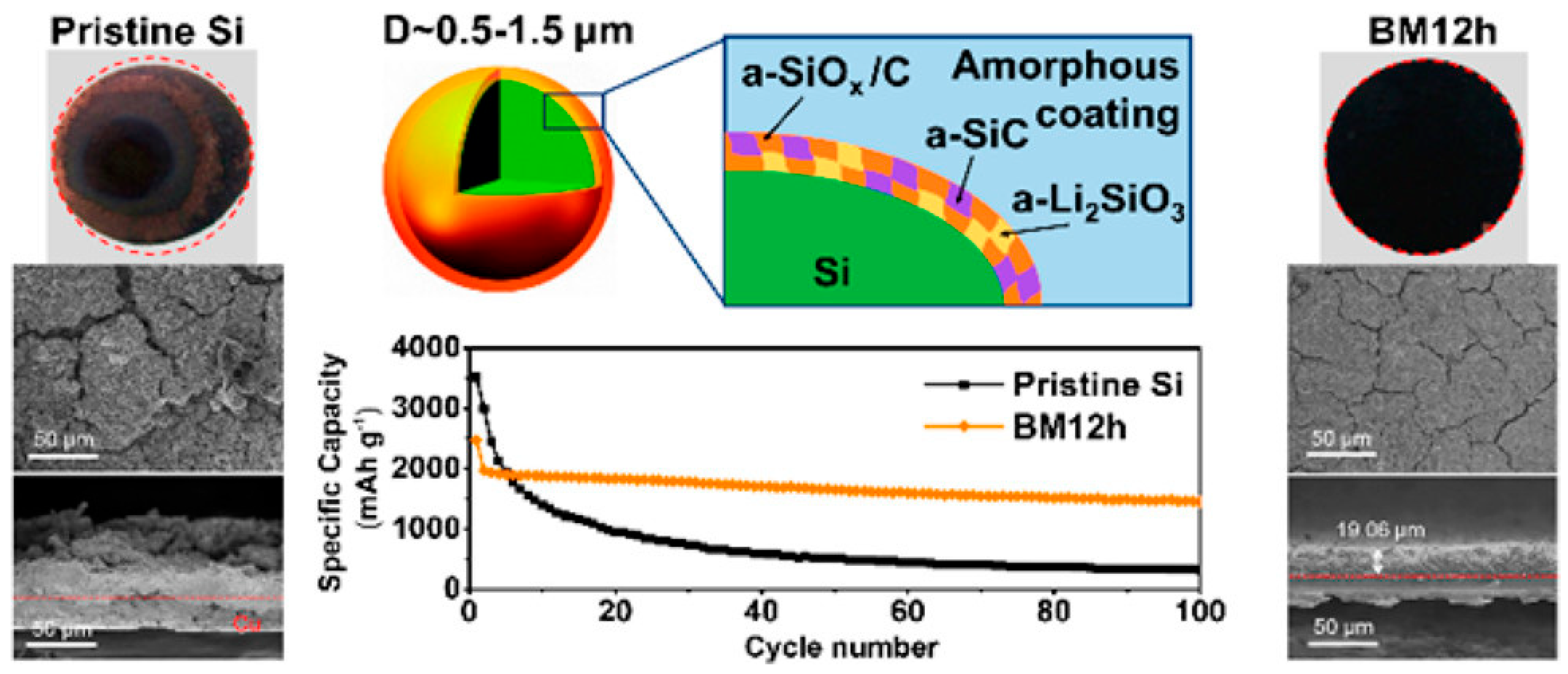

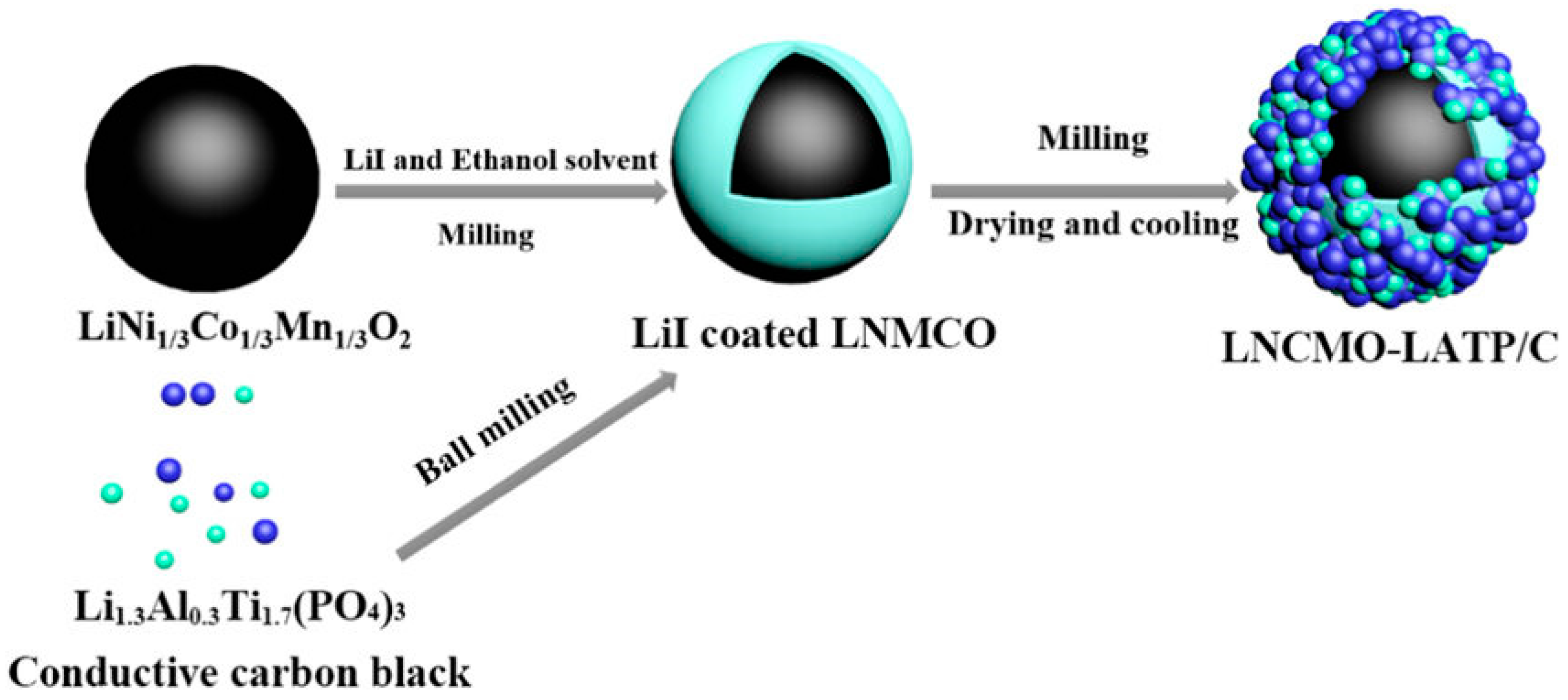

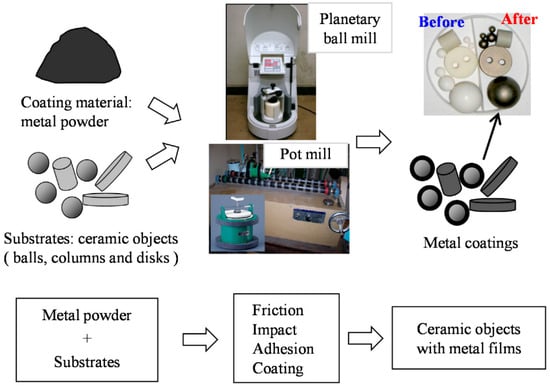

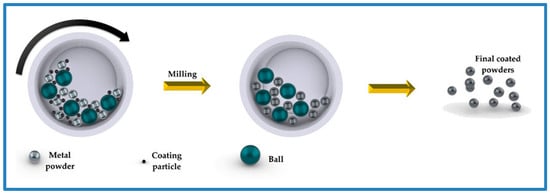

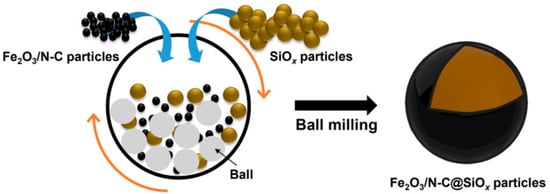

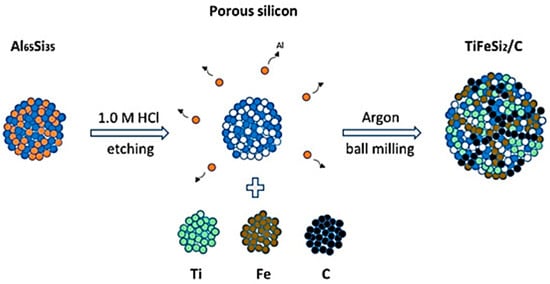

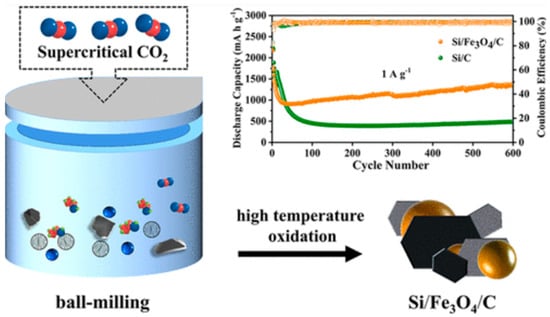

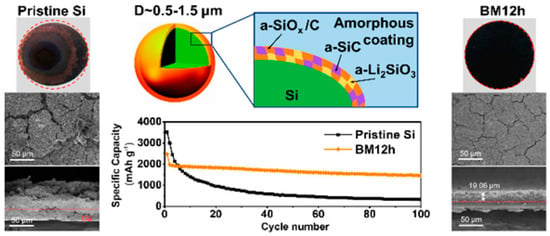

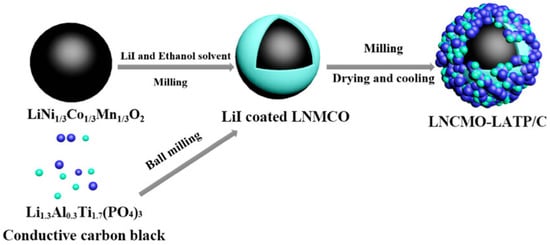

The complexity, inefficiency, and high costs often hinder the mass production of core–shell materials. However, ball-milling presents a low-cost, high-yield, and scalable solution for the efficient fabrication of core–shell structures in cathode materials and silicon (Si) anode materials, making it suitable for pilot plant manufacturing (Figure 3) [37]. The synthesis of core–shell structures in ball mill equipment is driven by the energy generated from the impacts of the balls colliding with the shell and core materials. These collisions occur between either two balls or a ball striking the wall of the chamber, which results in the shell material adhering to the core material due to the impact energy produced during the rotational movement. This continuous coating process ensures that all particles are subjected to the balls’ impact energy thousands of times, thereby facilitating the mechanical ball-milling method to create a non-destructive coating layer on the host material, which is commercially viable. Additionally, the literature indicates that high temperatures applied during the calcination process in air contribute to achieving a smooth and compact surface for the core–shell structure following the ball-milling process.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of (a) Ball milling process and (b) scalable synthesis of core–shell materials using the ball milling process. Modified from ref. [37] Copyright 2023 Small Methods.

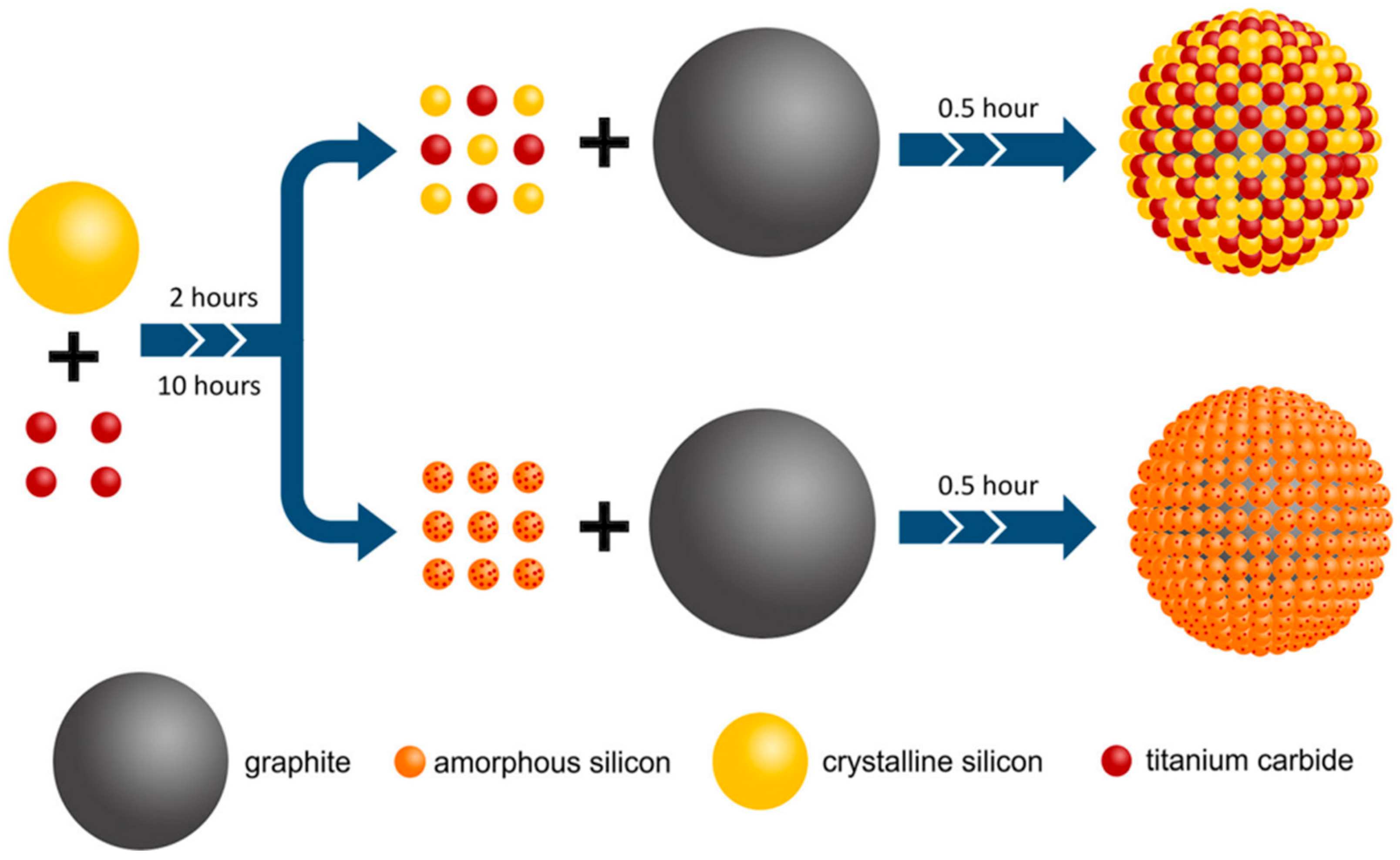

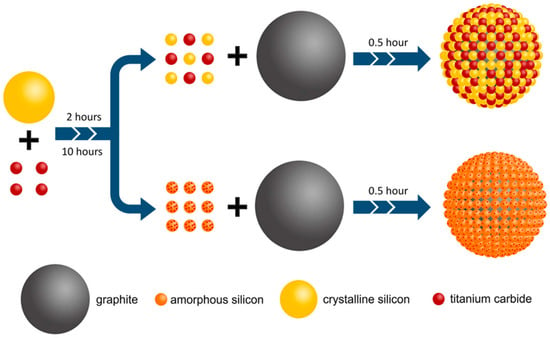

Recently, Pan et al. demonstrated that a straightforward multi-step high-energy ball-milling method provides an efficient and scalable approach to coat amorphous silicon/titanium carbide (Si/TiC) onto graphite (G), intended for use as anode materials in lithium-ion batteries (Figure 4) [38]. In this unique preparation technique, Si is entirely transformed into an amorphous phase along with TiC following an extended milling time. TiC is gradually converted into nanocrystalline grains that are distributed across the surface of the amorphous Si, forming a network of nanosized conductive channels. It is also shown how the duration of ball-milling influences the degree of amorphization of Si and the structure of the Si/TiC composite, as well as the impact of the composite’s unique structure on the electrochemical performance of the Si/TiC/G electrode.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of Si/TiC-coated G using the ball milling process. Adapted with permission from ref. [38] Copyright 2021 Journal of Electronic Materials.

This study not only demonstrates the flexibility of mechanical coating techniques for producing advanced electrode materials, but also underscores the broader perspective developed in this review. We position mechanical coating and ball milling as not merely surface-engineering tools, but as enabling technologies for functional and scalable applications such as energy storage. This framing distinguishes our review from prior work by highlighting cross-disciplinary applications, where coating science directly supports emerging technologies like lithium-ion batteries.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of MCTs with a special focus on ball milling. The emphasis on ball milling is particularly timely given recent developments in materials science and industrial processing. The rise in nanostructured core–shell and multilayered systems in biomedical, energy storage, and catalytic applications has created a strong demand for coating methods that can reliably produce fine, uniform structures [38,39]. At the same time, industries are increasingly prioritizing scalable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly processes, making mechanical coating by ball milling highly attractive compared to vapor-phase or chemical methods [25,40]. Moreover, the growing interest in data-driven optimization and sustainable manufacturing further enhances the relevance of re-examining ball milling, not only as a traditional method but as a platform adaptable to next-generation applications [41,42]. Key topics include the principles of ball milling, different types of mills, process parameters, coating mechanisms, and industrial applications. Recent advancements, challenges, and future research directions are also discussed to offer a holistic understanding of mechanical coatings.

2. Fundamentals of Ball Milling

Ball milling falls under the broader category of mechanical alloying, which refers to a process enabling the synthesis of new materials starting from elemental powders. This technique coincides with the conceptual onset of mechanical coating in one context: the coating of balls that subsequently proceed to coating (or milling) powders via either the formation of ball-powder-ball collisions or other methods such as plowing or shearing. Some studies on mechanical coating using other coating devices, which we will not further cover in this review, were present in the literature just before the inception of mechanical coating in the ball mill [3,4,7,9,26,43,44].

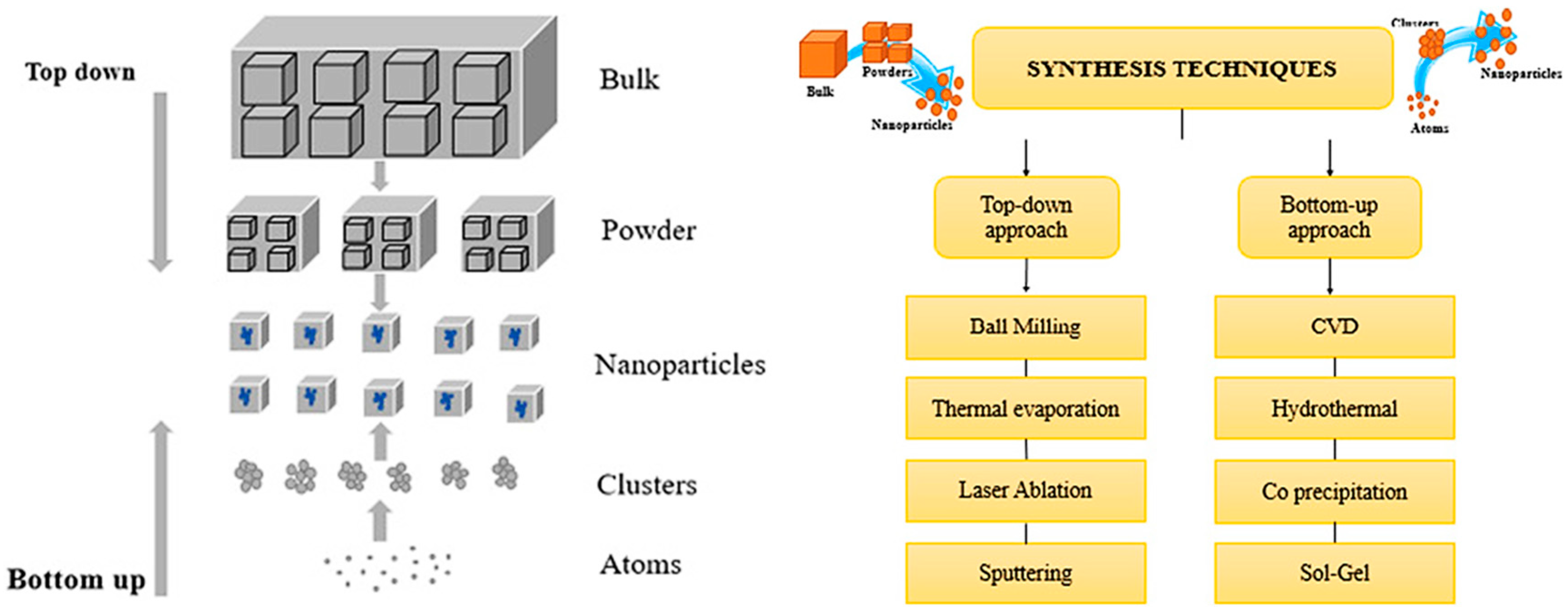

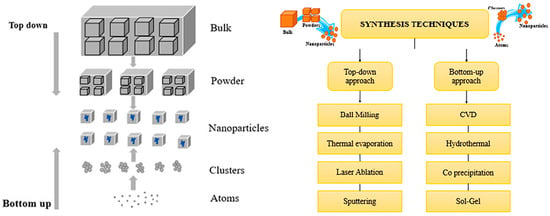

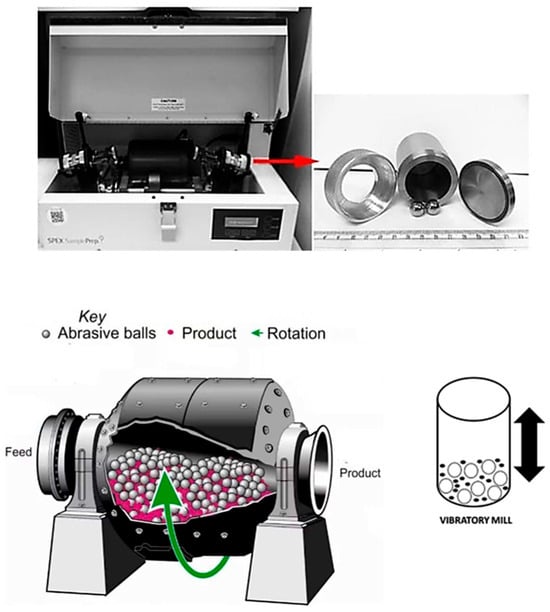

Ball milling is a top-down technique that grinds bulk materials into fine powders using a rotating chamber filled with hard grinding media, such as stainless steel or ceramic balls (Figure 5) [45]. The rotation causes collisions that reduce particle size, and by adjusting factors like speed and media size, the final characteristics of the particles can be controlled. This method is commonly used in materials science and manufacturing to create and enhance composite materials. The effectiveness of ball milling depends on the mill’s rotational speed, the size and weight of the grinding media, and the ratio and distribution of the materials being processed [3,4,7,26,46,47]. These factors will be further discussed in this review.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches. Adapted with permission from ref. [45] Copyright 2022 Advances in Colloid and Interface Science.

Moreover, different types of ball milling equipment are available to suit specific material pulverization needs. These include traditional ball mills, planetary ball mills, and vibratory mills, each designed with unique mechanisms to enhance grinding efficiency and achieve desired specific purposes [46]. This review will also explore the applications and advantages of each type, providing a comprehensive understanding of their roles in material processing. By examining these aspects, we aim to offer insights into the selection and optimization of ball milling techniques for various industrial applications.

2.1. Principles of Ball Milling

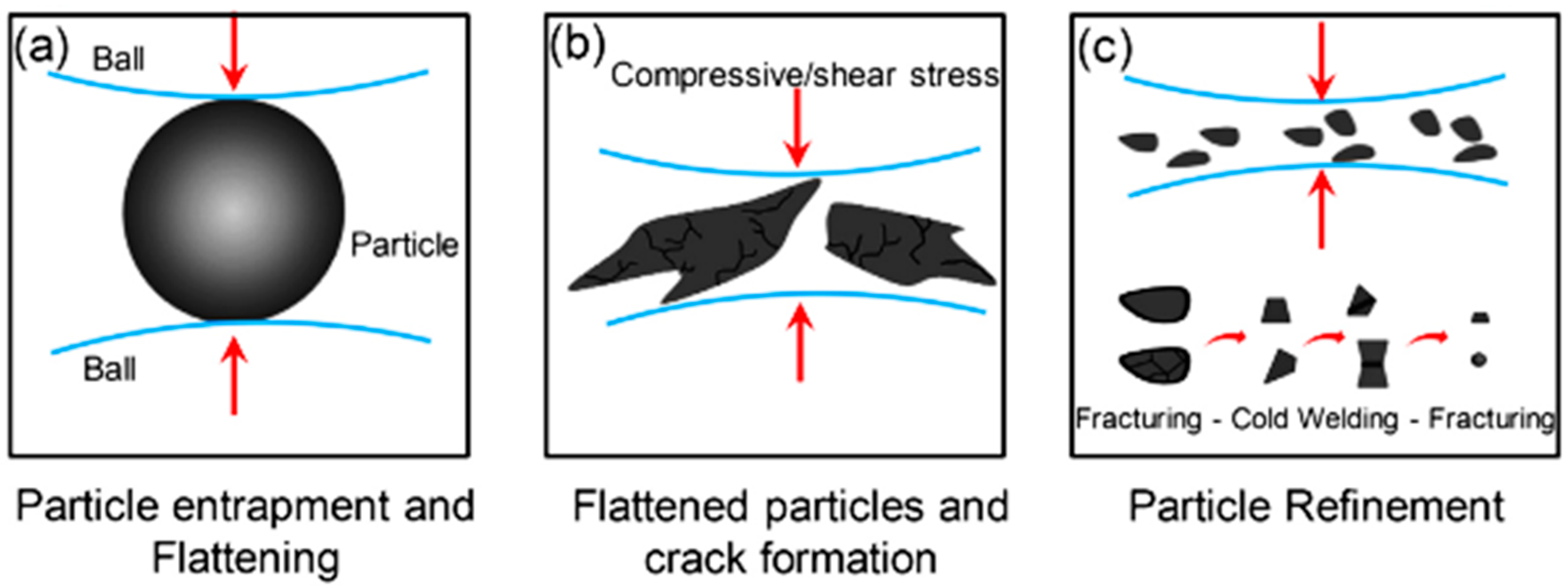

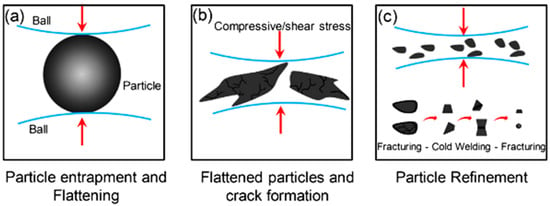

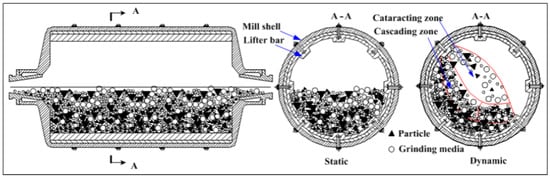

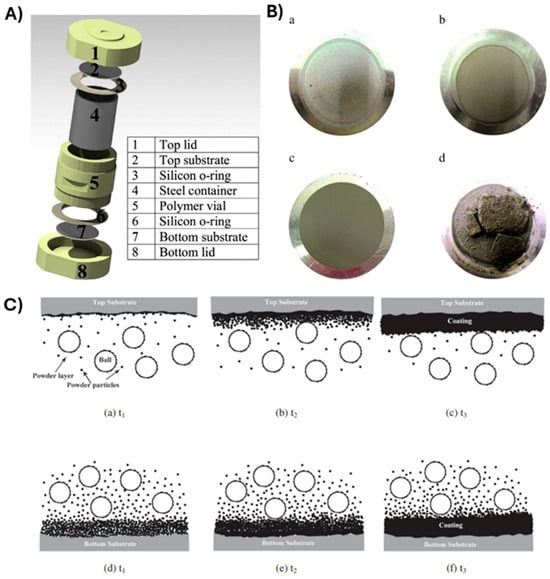

The process of ball milling utilizes a grinding vessel (container) filled with material to grind into fine powders (Figure 6). These containers are designed to produce frictional stresses that lead to creating fracture planes and removing surface layers. The efficiency of this method depends on the complex interaction and collaboration between the various components in the grinding medium and the material being worked on [26,27,45,48,49].

Figure 6.

Principle of mechanical alloying by the HEBM process. (a) Particle entrapment and flattening during ball-particle collision, (b) Deformation of particles by flattening and propagation of cracks, (c) Particle refinement undergoes cold-welding and agglomeration that increase particle size. Modified with permission from ref. [49] Copyright 2016 Journal of Environmental Management.

2.2. Types of Ball Mills

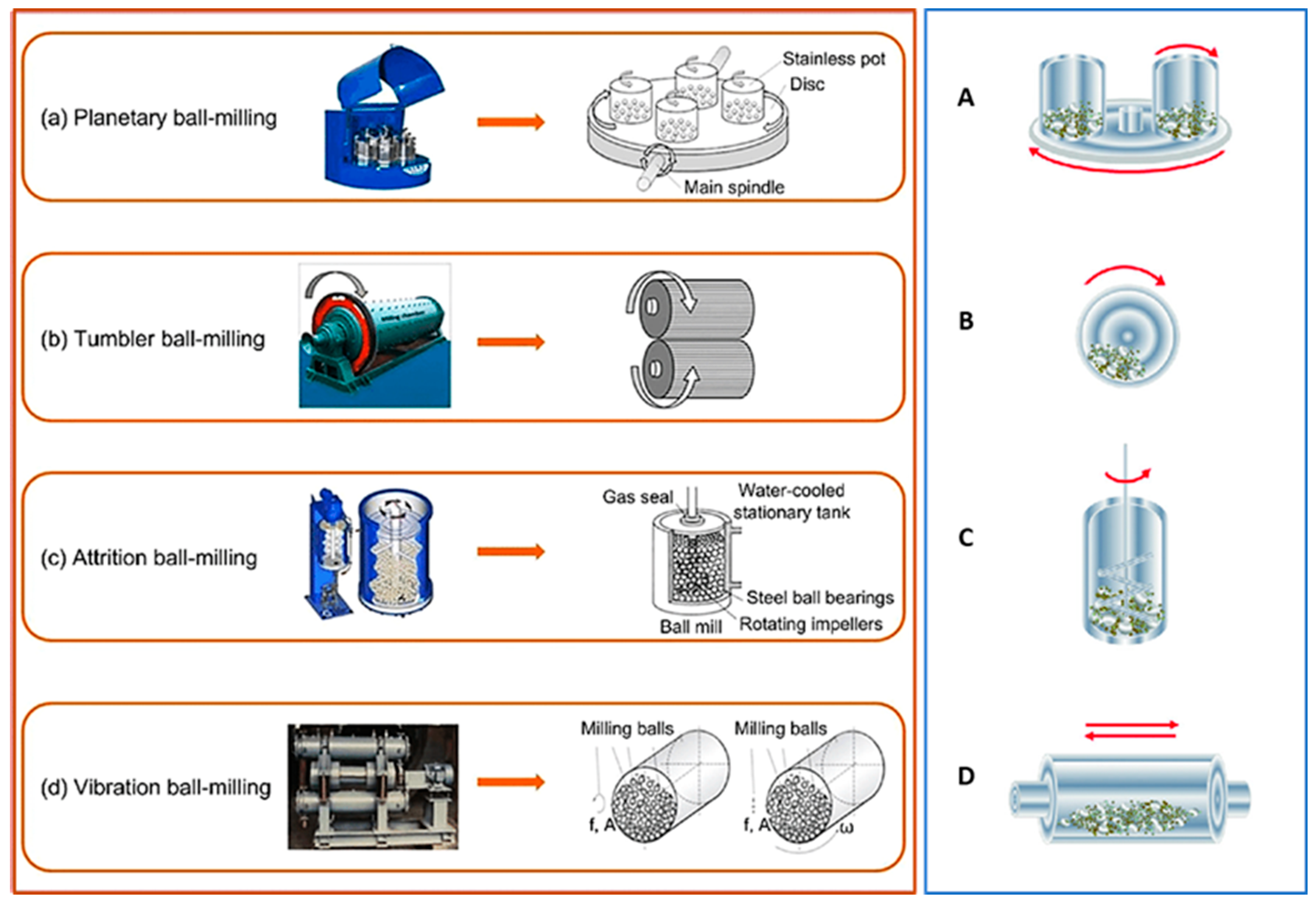

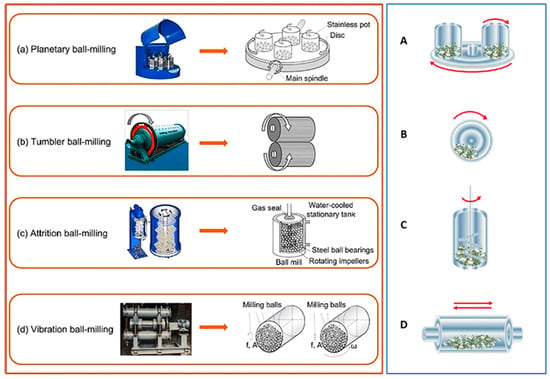

Ball mills are classified according to their design features as tumbling (cone or ball) mills, vibratory ball mills, planetary ball mills, and attrition ball mills as shown in Figure 7 [1,5,8,48,50,51]. Each type of ball mill has its own distinct set of characteristics and benefits, that make it appropriate for certain mechanical coating processes and materials. The design, size, speed, and energy input of each type of ball mill are critical in determining its suitability for a variety of industrial and research purposes.

Figure 7.

Different types of ball milling and its working principles: (a) Planetary ball milling and (A) its cylinder rotation direction, (b) Tumbler ball milling and (B) its cylinder rotation direction, (c) Attrition ball milling and (C) its cylinder rotation direction, and (d) Vibration ball milling (where f is vibration frequency, A is vibration amplitude, and ω is angular velocity) and (D) its cylinder rotation direction. Modified from ref. [24,25].

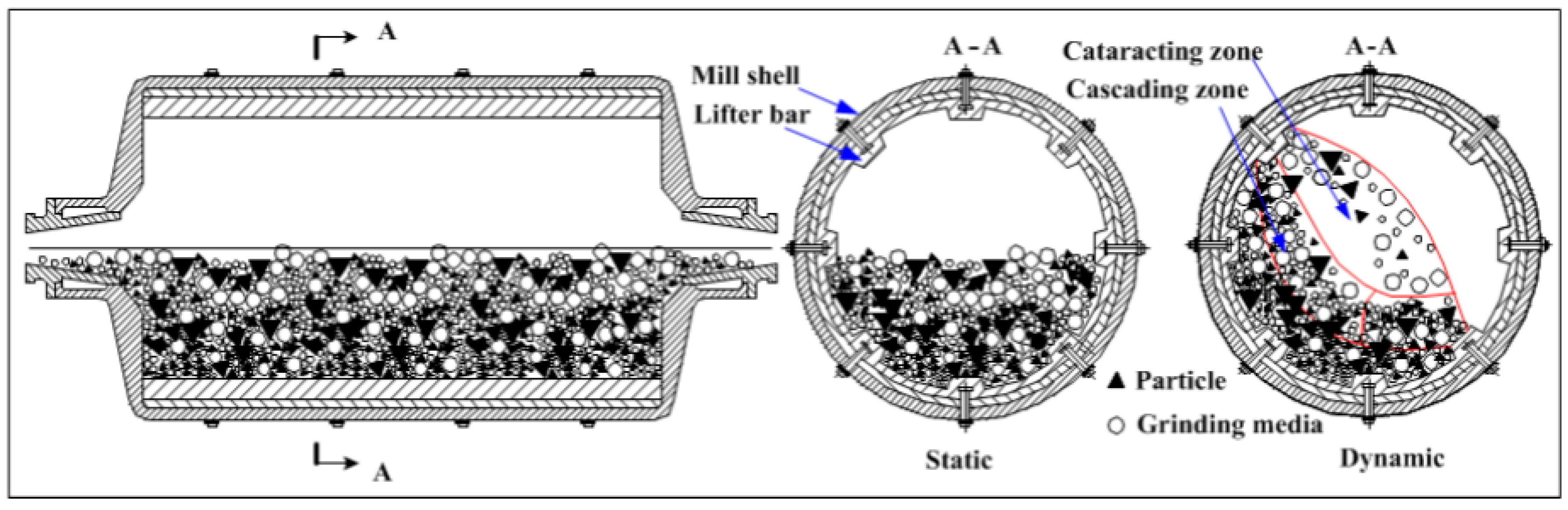

2.2.1. Tumbling Ball Mills (TBM)

Tumbling Mills, also known as ball mills or tube mills, operate by rotating a cylinder bowl filled with grinding media such as balls and the material to be coated (Figure 8). The dynamic movement of the media generates powerful impact and shear forces, allowing coating and grinding procedures to be carried out successfully. Tumbling mills are ideal for large-scale applications because of their simple design, ease of operation, and cost-effectiveness [46,48,52]. Nonetheless, they give less exact control over particle size distribution and coating homogeneity than other types of mills. They also provide less precise control over particle size distribution and coating uniformity compared to other types of mills [9,47].

Figure 8.

TBM working principle. Adapted with permission from ref. [52] Copyright 2017 Materials.

Coating Mechanism: In a TBM (a horizontal rotating cylinder), coatings form through repeated impact and friction as the balls cascade and tumble. The kinetic energy is transferred to powder particles via collisions between balls and powder, pressure loading of particles trapped between balls or against the mill wall, and shear/abrasion as the media roll over the material [9]. These repetitive forces cause ductile coating materials to cold-weld onto substrate particles. Over extended milling, the coating material first adheres in patches then coalesces into a continuous layer on the particle surface. This low-energy process proceeds gradually, but it yields a fairly uniform and homogenous coating given sufficient time. TBMs operate at relatively low speeds (typically 10–50 rpm) and impart lower impact energy, resulting in slower coating kinetics than high-energy mills [9]. However, the gentle action minimizes excessive fracturing of particles and tends to produce coatings of consistent thickness across the powder batch.

One real-world use of a TBM for coatings is in mechanical plating (also known as peen plating). In this industrial process, a rotating drum is filled with the target parts (e.g., steel nails), metal powder, additive agents, and hard media (often glass or steel beads). As the drum tumbles, fine metal particles are cold-welded onto the workpiece surfaces, building up a coating [53]. Common plating metals include zinc, tin, or cadmium for corrosion protection. For instance, small steel components can be zinc-coated by tumbling in a barrel with zinc powder and media, avoiding the hydrogen embrittlement associated with electroplating [54]. In academic studies, TBM have been used to coat metal powders with soft phases: Kim et al. demonstrated dry coating of wax onto copper (Cu) powders using a simple tumbling mill [55]. Such coatings improved the powder’s handling and thermal properties. Although hours or days of milling may be required for full coverage in a tumbling mill, the technique’s scalability and simplicity make it valuable for bulk powder coating and large-batch processes.

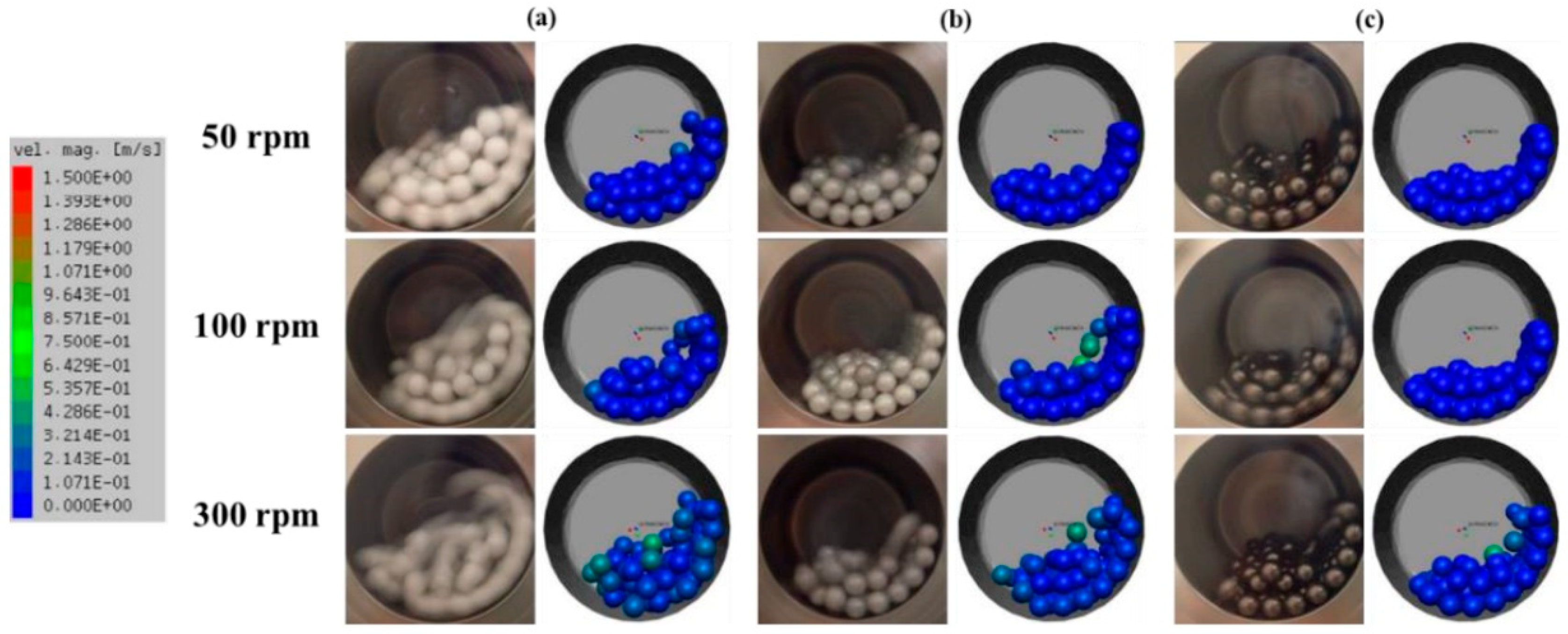

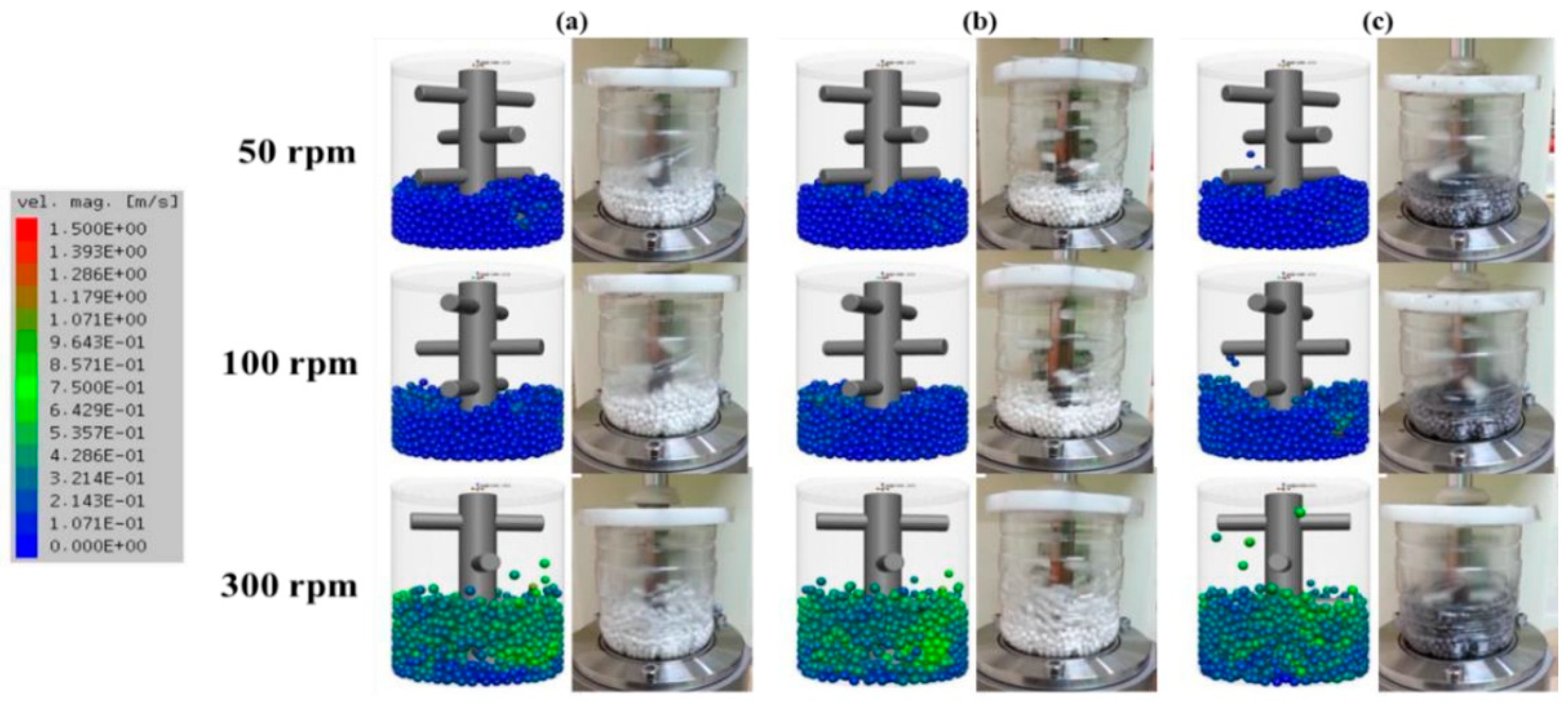

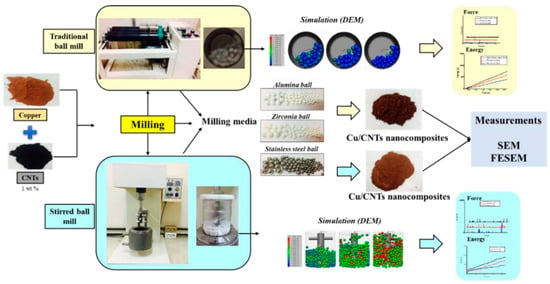

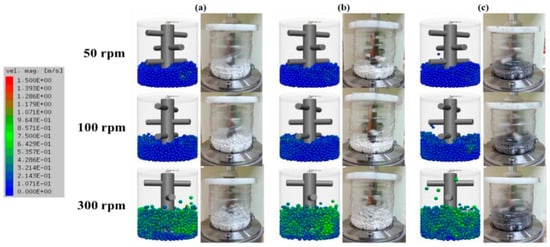

Another example is the work of Bor et al., who examined the surface coating of Cu powder using TBM with different milling media ZrO2 and Al2O3 [56]. The TBM demonstrated a more vigorous and less controlled impact-based milling environment, which led to irregular particle morphologies and weaker coating uniformity. Simulations via the Discrete Element Method (DEM) revealed that TBM generated higher collision energies, particularly near the vessel walls, causing more fragmentation and agglomeration of Cu particles (Figure 9). The analysis suggested that the choice of harder media like ZrO2 in TBM resulted in more pronounced particle deformation and surface coating inconsistencies due to the random motion and lower media-powder contact frequency.

Figure 9.

Simulation and actual snapshot photograph of the media motion by DEM simulation (a) alumina ball, (b) zirconia ball, (c) stainless steel ball with different revolution speeds in a TBM. Adapted with permission from ref. [56] Copyright 2020 Coating.

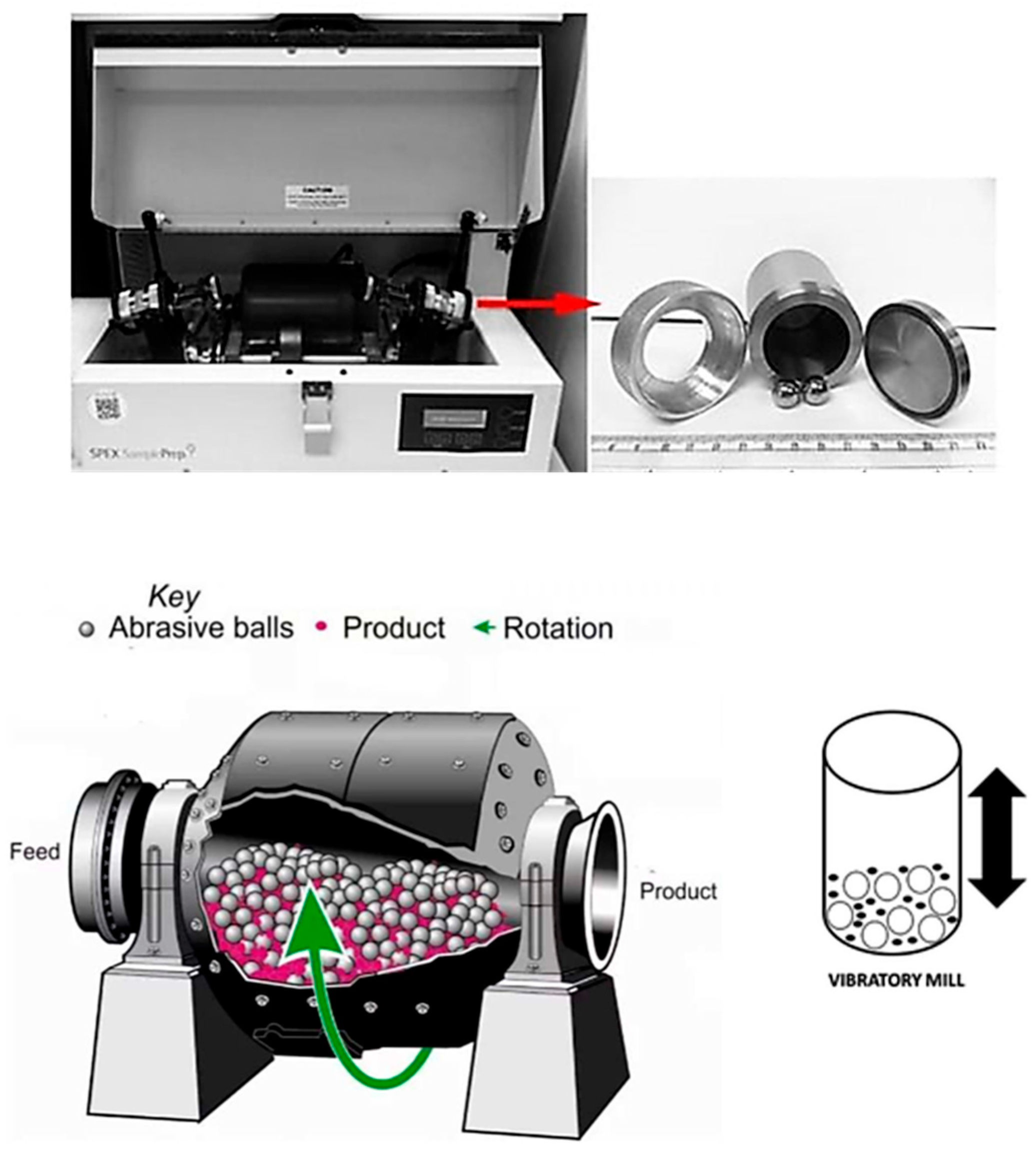

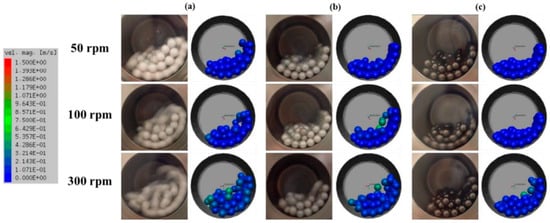

2.2.2. Vibratory Ball Mills (VBM)

Vibratory mills utilize high-frequency vibrations to agitate the grinding media and material (Figure 10). This unique method creates high friction and impact forces, resulting in the production of fine and homogeneous particle sizes. These mills excel in fine and ultra-fine grinding, as well as in coating processes requiring precision and uniformity. Their advantages include precise particle size control, high energy efficiency, and the ability to process heat-sensitive materials with minimal heat generation. However, they have higher operational costs and more complex maintenance compared to tumbling mills [1,5,7,8,9,48,57,58].

Figure 10.

(Top) photo of SPEX8000D high-energy ball mill with its milling tools (vials and balls) (Spex Sample Prep Mixer Mill 8000M, Metuchen, NJ, USA) (Bottom) principle of VBM. Modified from refs. [9] Copyright 2021 Nanomaterials and 2018 Materials Science and Engineering [57] and 2019 Nanoscale Advances [58].

Coating Mechanism: A VBM (also called a shaker mill) applies high-frequency, low-amplitude oscillation to a milling vial, agitating the ball media with intense kinetic energy. For example, the SPEX mill oscillates a sealed vial ~1200 times per minute in three dimensions [9]. This rapid vibration produces very fast impacts between the balls and particles, leading to high localized pressures and shear forces. The coating material is repeatedly hammered and smeared onto the substrate particle surfaces in a short time. Because ball velocities in a VBM can exceed those in a planetary mill [5], the powder experiences energetic collisions that promote cold-welding of coatings quickly. The mechanism is efficient: brittle phases are pulverized and embedded onto ductile surfaces, and ductile phases flatten into films. However, violent milling can also fragment coated particles if not controlled, so optimizing parameters (impact frequency, time, ball-to-powder ratio) is vital to achieve a uniform coating without significant particle damage. VBM typically handles small powder batches (on the order of tens of grams) due to their intensive energy input and heat generation, but they excel in speed of coating and particle size reduction.

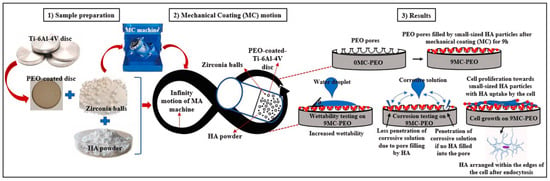

VBM is widely used in laboratory research for the rapid synthesis of coated composite powders and nanostructured materials. For instance, one study used a vibratory milling approach to deposit bioactive hydroxyapatite (HAp) ceramic coatings onto titanium alloy substrates [59]. Using a ZrO2-lined vibrating chamber with zirconia balls, researchers achieved a high-density HAp coating that covered over 95% of the Ti surface after milling [59].

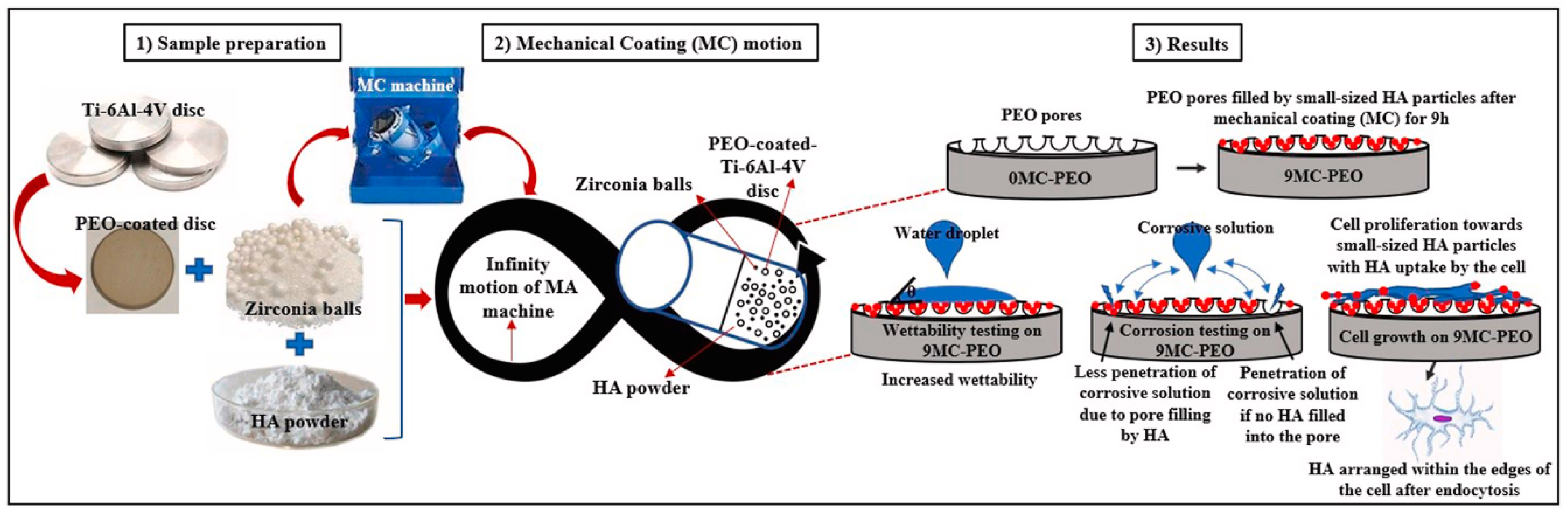

Another study conducted by Nisar et al., where he applied a porous oxide layer on Ti–6Al–4V alloy using Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation (PEO), created a rough, bioactive surface. Subsequently, HAp particles were mechanically deposited onto the PEO-treated surface via a high-energy ball impact process, enhancing the coating’s adhesion and coverage (Figure 11). The dual treatment synergistically improved surface roughness, wettability, and apatite-forming ability in simulated body fluid (SBF), indicating a significant enhancement in the implant’s potential for bone integration [60].

Figure 11.

Mechanical HAp coatings on PEO-treated Ti–6Al–4V alloy for enhancing implant’s surface bioactivity. Adapted with permission from ref. [60] Copyright 2024 Ceramics International.

This demonstrates how vibratory milling can effectively peen a brittle ceramic onto a metal substrate, producing a uniform biomedical coating at room temperature. In another example, a SPEX shaker mill was employed to embed carbon nanotubes into aluminum (Al) matrix powder, rapidly producing a nano-reinforced composite; the high-energy oscillating impacts enabled a homogeneous dispersion of CNTs on Al particles in a fraction of the time required by conventional milling [5]. Such high-energy mills have also been used to amorphize alloy powders and to coat catalytic materials on supports. The VBM’s ability to induce quick, aggressive mixing makes it ideal for small-scale applications like preparing novel composites or coatings for research, where speed is more critical than volume.

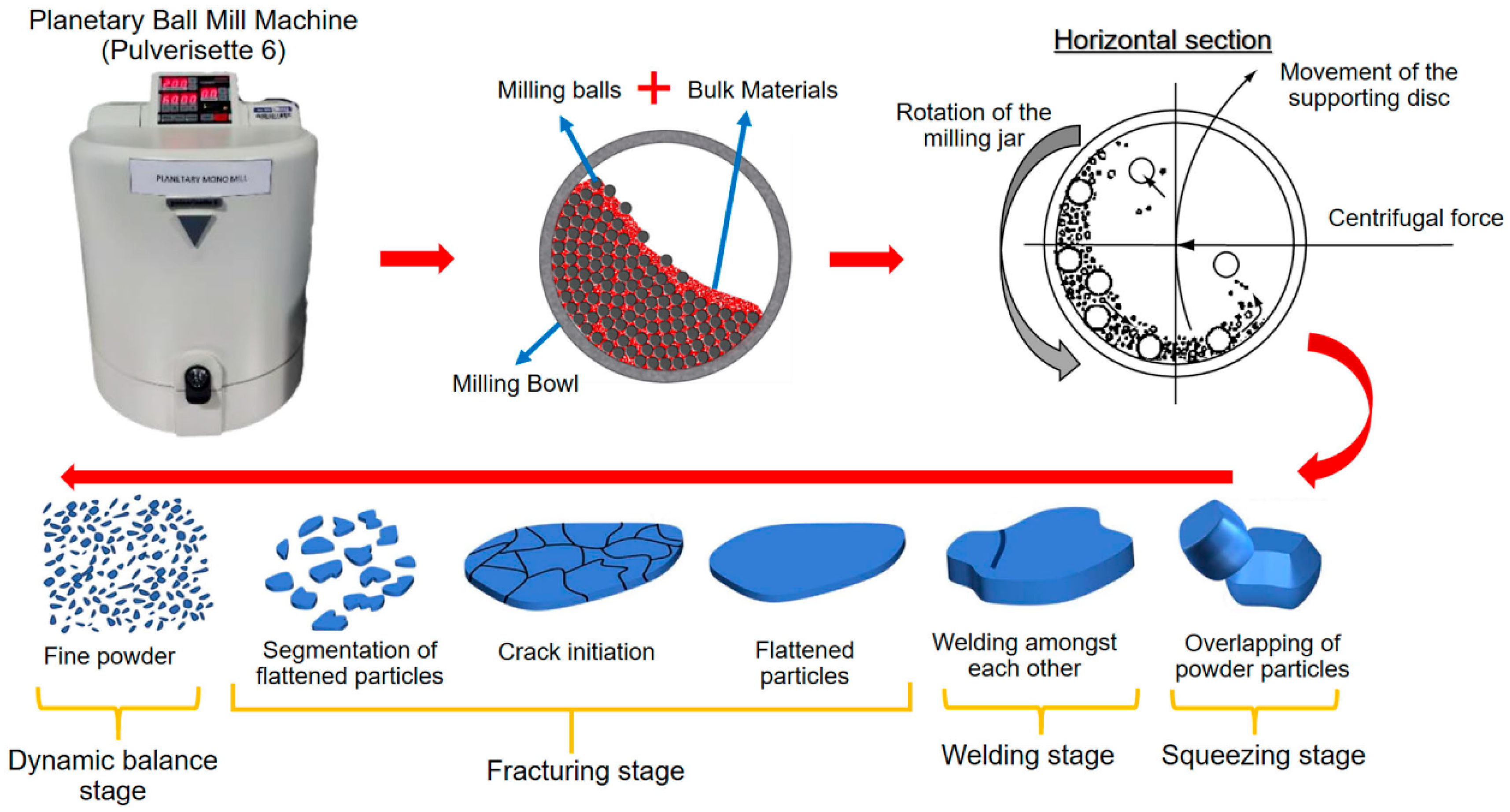

2.2.3. Planetary Ball Mills (PBM)

Planetary mills are equipped with one or more grinding jars that are carefully mounted on a rotating sun wheel. The grinding jars rotate around their axes in the opposite direction of the sun wheel’s rotation, creating intense impact and shear forces (Figure 12). This unique milling process is ideal for mechanical alloying, fine grinding, and for producing nano-sized particles. This makes PBM particularly effective for materials that demand thorough mixing and grinding. These mills are known for providing high energy input, precise control over milling parameters, and the ability to produce very fine and uniform particle sizes. Despite these benefits, PBM have limited scalability for industrial applications and higher costs for equipment and maintenance [1,5,8,48,61,62].

Figure 12.

Principles of the PBM method for reducing powder particle size. Adapted with permission from ref. [41] Copyright 2023 Materials.

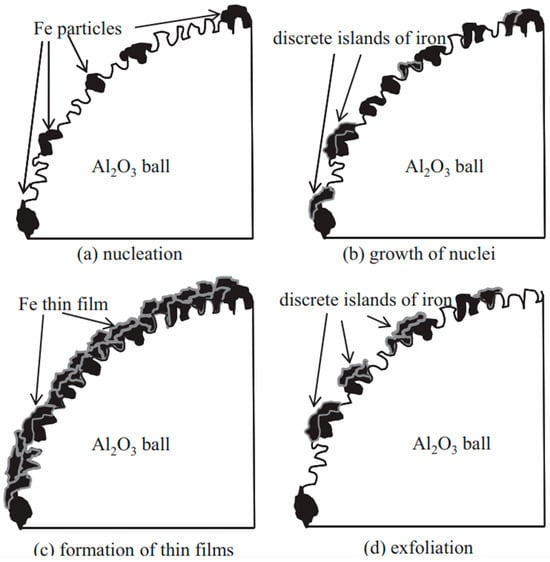

Coating Mechanism: A PBM consists of a rotating support disk on which milling jars spin around their own axes, creating complex motion of the balls. The jars and supporting disk rotate in opposite directions, so the balls experience alternating centrifugal forces that can reach ~10–20 times gravity in standard configurations [9]. This produces powerful collisions as the balls are lifted and then thrown across the jar, as well as vigorous friction as they roll along the walls [9]. Under these high-energy impacts and shear forces, coating materials are repeatedly fractured and cold-welded onto base particles. The mechanism typically involves a sequence of stages: initially, tiny fragments of the coating material adhere (nucleation by adhesion); continued milling causes these fragments to flatten and coalesce into discrete island patches; further collisions join the islands into a continuous coating film that thickens over time; if over-milled, the coating may eventually spall in places (exfoliation) due to strain buildup [12]. Because of the intense mechanical action, PBMs can coat particles much faster than a tumbling mill. They effectively embed reinforcing phases or surface layers onto host particles, often reaching nanoscale structural refinement. Careful control (e.g., periodic milling with cooling pauses) is used to prevent overheating due to the high energy input. Overall, the PBM’s combination of impact and shear provides an aggressive coating mechanism well-suited for producing mechanically alloyed coatings and nano-composites.

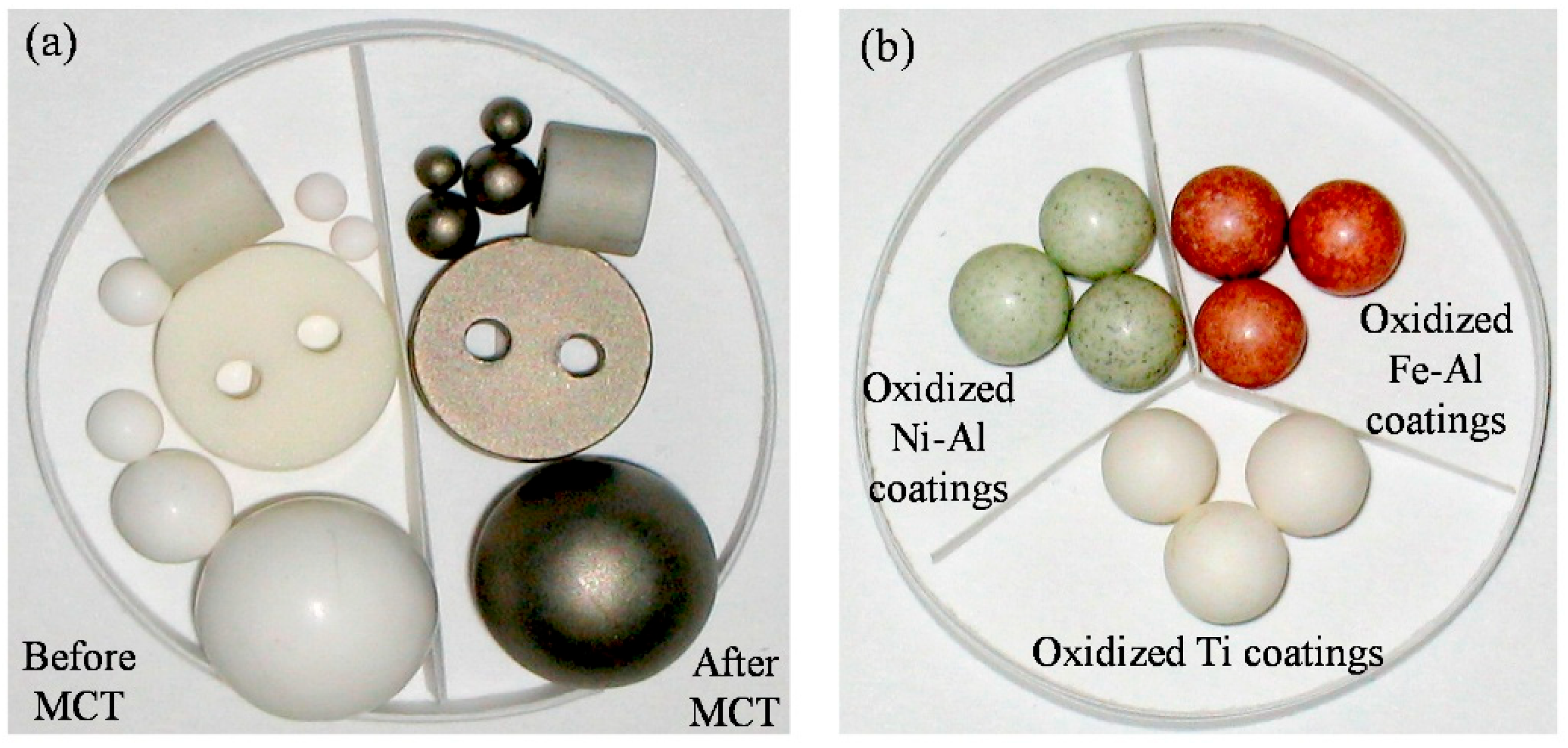

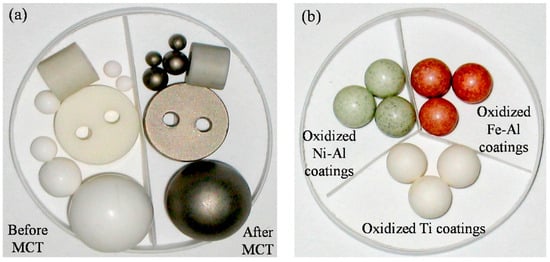

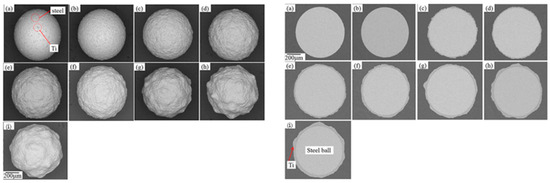

Example Application: PBMs are a staple in academic research for creating advanced coated powders and novel material phases. A notable example is the MCT to produce photocatalytic coatings: Lu et al. used a PBM to coat Ti metal onto alumina spheres, then oxidized it to form a TiO2 photocatalyst layer (Figure 13) [12]. Thanks to the high impact forces, the PBM achieved the desired coating thickness (about 10–12 µm) in only ~26 h of milling, whereas a traditional low-energy “pot” mill required on the order of 1000 h for a similar result. This dramatic reduction in processing time highlights the efficiency of PBM for coating formation [12].

Figure 13.

Appearance of samples by MCT and oxidized metal coatings. (a) Al2O3 objects before and after MCT; (b) The oxidized metal coatings. Adapted with permission from ref. [12] Copyright 2015 Coatings.

PBMs have also been employed to synthesize nanocomposite powders; for example, preparing alloyed metal-ceramic composite particles or core–shell structures for thermal barrier coatings. In one study, a PBM was used to uniformly coat silicon carbide (SiC) nanoparticles onto Al powder, creating a dispersion-strengthened Al/SiC composite suitable for powder metallurgy [9]. Additionally, battery and fuel cell materials often utilize PBM to coat active material particles with carbon or metal oxide layers, improving conductivity and stability. While PBMs are generally limited to laboratory or pilot-scale quantities, they provide unparalleled control over coating microstructure and are invaluable for investigating coating processes in a research setting.

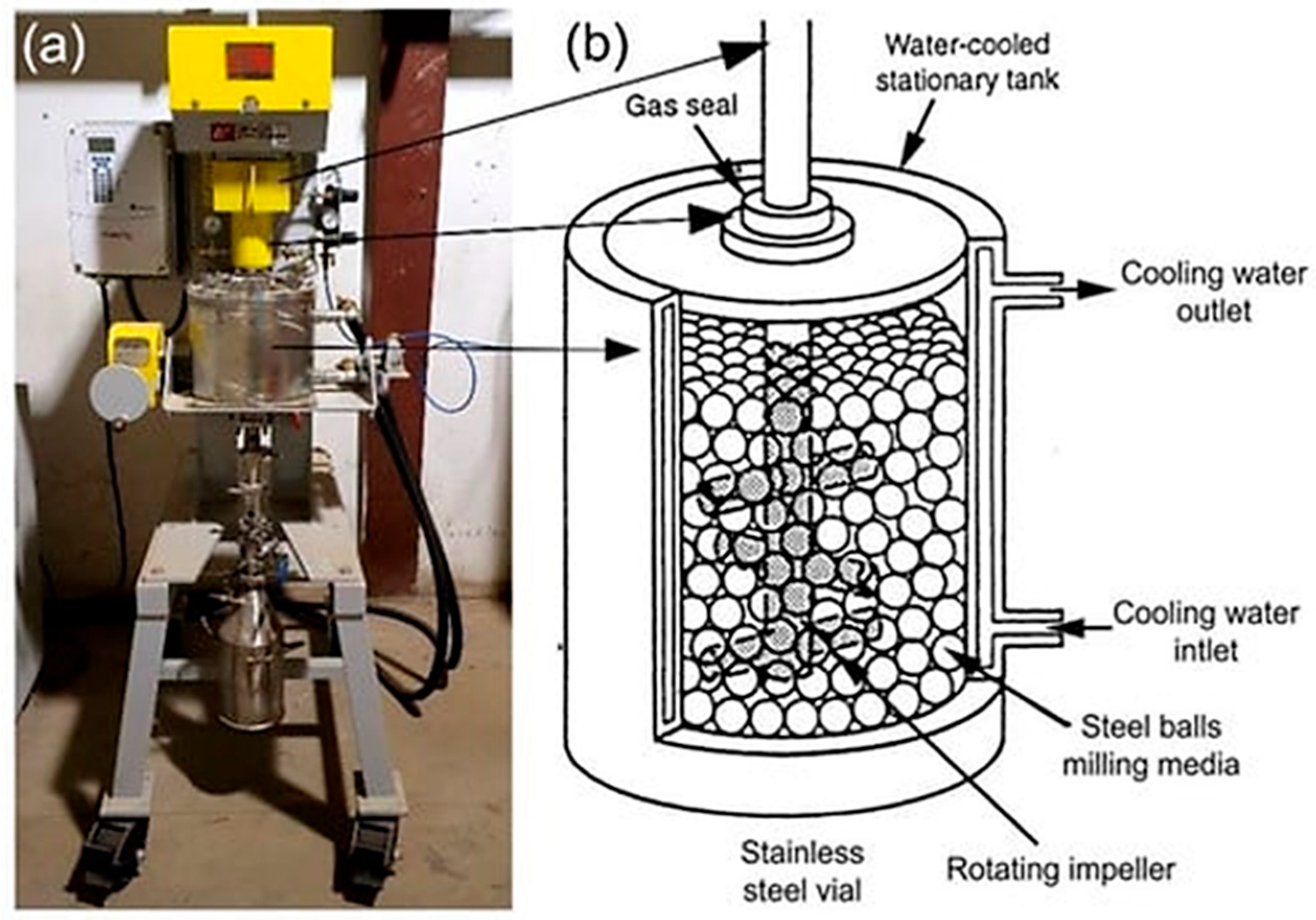

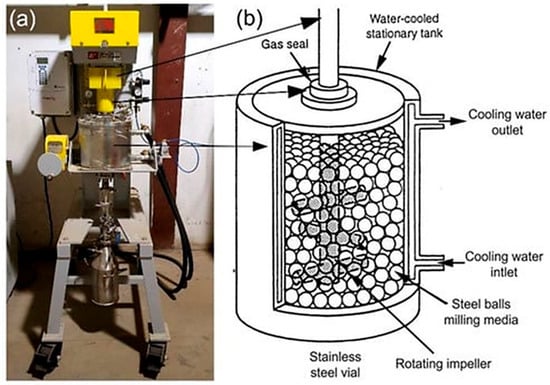

2.2.4. Attrition Ball Mills (ABM)

Attrition mills, also called stirred ball mills, are equipped with a high-speed rotor that effectively agitates the grinding media and material. The movement of the rotor causes the media to grind and coat the material through shear and impact forces (Figure 14). These mills are perfect for producing fine and ultrafine powders as well as for coating processes demanding uniform particle sizes and high surface areas. The advantages of ABMs include high energy efficiency, good control over particle size and distribution, and the capability to create homogeneous coatings. However, they have greater operational costs, a more sophisticated design, and require more intensive maintenance compared to tumbling mills [1,5,8,48].

Figure 14.

(a) A photo of an ABM; sketches illustrate (b) ball movement inside attritor ball mill. The equipment is housed in the Nanotechnology and Applications Program (NAP), Energy and Building Research Center (EBRC), Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research (KISR). Adapted with permission from ref. [9] Copyright 2021 Nanomaterials.

Coating Mechanism: An ABM (also known as a stirred media mill or attritor) uses a stirring shaft with impeller arms to agitate a dense bed of milling balls. The stationary milling tank and the rapidly rotating agitator (typically 75–500 rpm, with some high-speed attritors up to ~2000 rpm) impose continuous impact and shear on the particles [9]. The milling media in an attritor are much smaller and more numerous than in a tumbling mill, creating a large number of simultaneous collision sites. Coating in this environment occurs via repeated micro-impacts and intense rubbing: powder particles are circulated through the milling chamber and collide with the moving beads, which press coating material onto their surfaces via impact loading and shearing action [9]. The process promotes very intimate blending of dissimilar materials in fact, attritors are known for achieving “the highest intensity intimate blending” and can disperse or mechanically coat additives onto particles during grinding [63]. Compared to other mills, the attritor’s efficient energy transfer and continuous agitation lead to quicker coverage of particles with the coating material, albeit sometimes at the expense of generating smaller particle sizes. The closed, stirred configuration also ensures uniform treatment of all particles (minimizing dead zones), which tends to produce consistent coating thickness and composition throughout the batch. In summary, the ABM’s mechanism is characterized by a combination of rapid impact collisions and vigorous shear flow, making it highly effective for coating formation in both dry and wet milling modes.

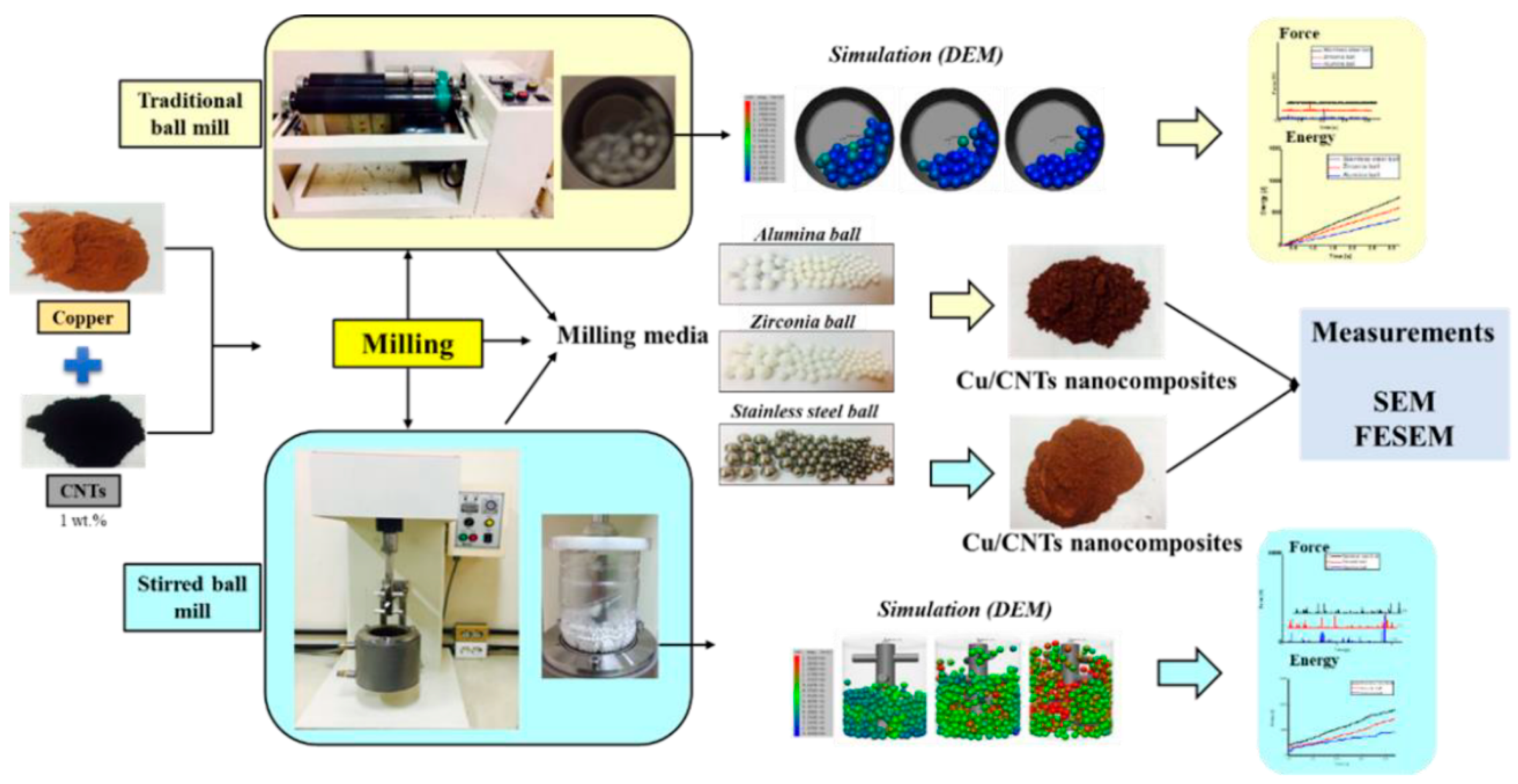

ABMs are frequently used for large-scale or rapid production of coated powders in both research and industry. For example, Bor et al. compared a traditional tumbler to a stirred ABM for coating Cu powder with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) (Figure 15) [56]. The attritor (vertical stirred mill) exhibited stronger impact energy and achieved a uniform CNT film on Cu particles after just 12 h of milling at relatively low speed, whereas the tumbler required longer durations for comparable results [56].

Figure 15.

Schematic view of the CNT coating on the metal surface powders by two kinds of ball milling processes. Adapted with permission from ref. [56] Copyright 2020 Coating.

The SBM offered a more refined and efficient coating mechanism. The continuous stirring motion resulted in higher contact frequency and a more homogeneous energy distribution among particles and milling media [64,65,66]. DEM simulations showed that the SBM produced lower collision energy but significantly improved the uniformity of coating on Cu powder, especially when using ZrO2 media (Figure 16) [56]. The spherical morphology and better dispersion of particles achieved in the SBM highlighted its superiority in promoting even coating and minimizing particle agglomeration. Overall, the SBM was found to be more effective than TBM for precise and uniform surface coating in powder processing applications.

Figure 16.

Simulation and actual snapshot photographs of the media motion by DEM simulation (a) alumina ball, (b) zirconia ball, (c) stainless steel ball with different revolution speeds in an SBM. Adapted with permission from ref. [56] Copyright 2020 Coating.

This indicates the attritor’s advantage in accelerating the coating process. In industrial contexts, ABMs are used to produce pigment-coated particles and composite powders for paints, inks, and ceramics; for instance, difficult-to-disperse pigments (iron oxides, carbon black, etc.) can be mechanically coated or finely dispersed onto extender particles using an attritor [63]. Attritors have also been employed to make dispersion-strengthened metals via mechanical alloying, where powders of different metals are co-milled to coat and embed hard phases within a ductile matrix [63]. This technique has been applied to produce oxide-dispersion strengthened alloys and composite metal powders for aerospace materials. A key benefit of ABMs is their scalability: laboratory attritors with ~100 mL vessels are available for experiment development, and the same process can be scaled up to production attritors holding hundreds of liters, all while maintaining similar shear/impact conditions. This scalability, combined with efficient energy use and uniform mixing, makes the ABM a workhorse for coating processes that require both high throughput and consistent quality of the coated product.

In summary, as shown in Table 1, planetary and vibratory mills provide superior control over particle size and their distribution, making them ideal for fine and ultrafine grinding. Furthermore, VBM and ABMs demonstrate greater energy efficiency compared to TBMs. TBMs are easier to scale for industrial applications, whereas planetary mills are more suited for laboratory and small-scale applications. In terms of cost-effectiveness and maintenance, TBMs come out on top, while vibratory and ABMs entail higher operational and maintenance expenses. Understanding these differences allows researchers and industry experts to select the most suitable milling method for their specific coating and material processing requirements.

Table 1.

Comparison of different types of ball mills based on grinding mechanism, energy efficiency, particle size control, scale, operational speed, contamination risk, and application suitability.

3. Mechanism of Metal Coating on Spherical Substrates Using Ball-Milling Process

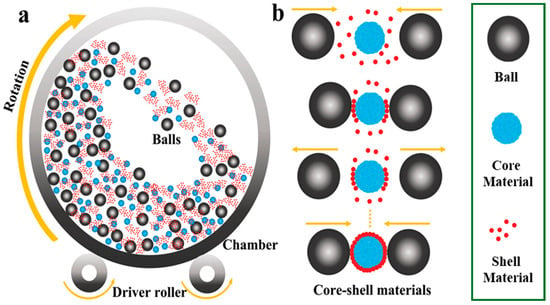

3.1. Zinc (Zn) Coating on Alumina (Al2O3) Balls

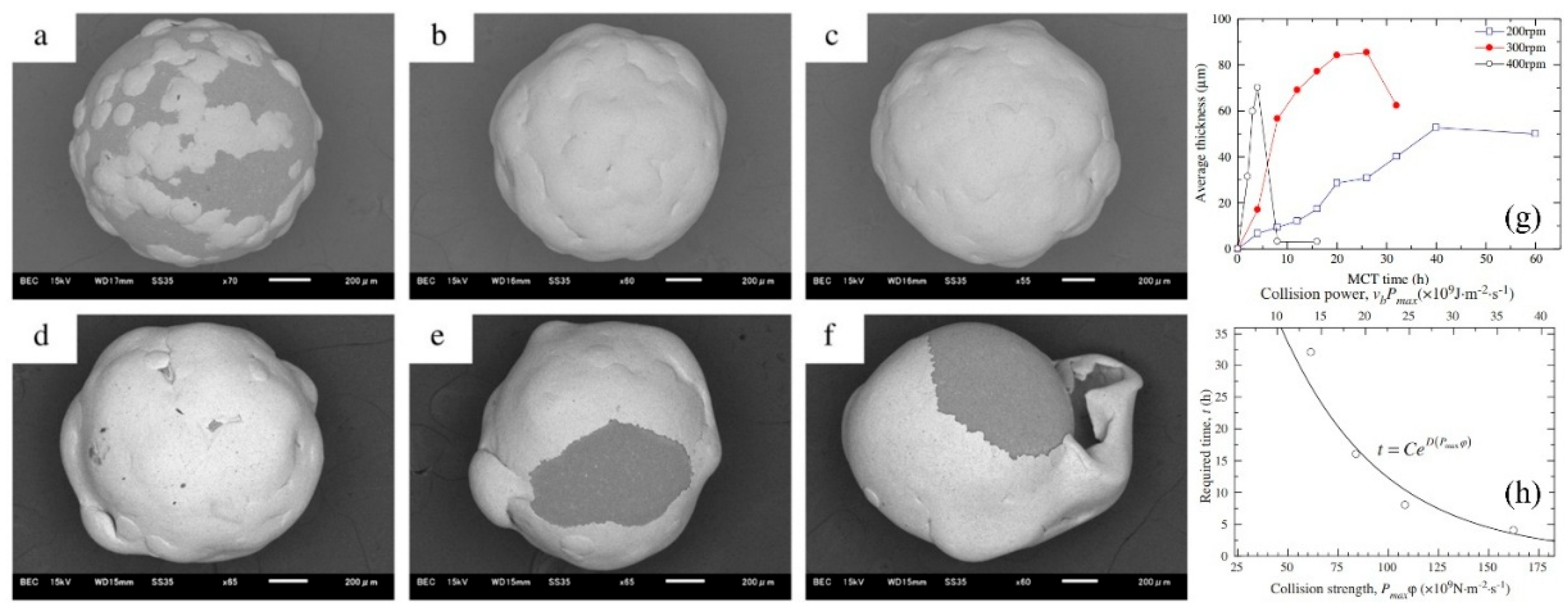

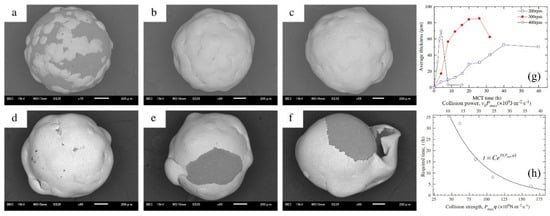

Hao et al. reported the effect of processing parameters on the detailed evolution of coating for the fabrication of Zn coatings on Al2O3 balls (Figure 17) [67]. The effect of the rotation speed of the planetary ball mill on the evolution of coatings was specifically investigated. The findings revealed that continuous and highly dense zinc coatings, averaging about 100 μm in thickness, were formed during the milling process at a speed of 300 rpm. To achieve these continuous Zn coatings, critical collision pressure, which corresponds to a critical minimum rotation speed, was essential to induce a critical plastic strain in the zinc particles. Exponential relationships between the time required to form continuous zinc coatings and both collision strength and collision power were established. These relationships indicated that the necessary time is influenced by the collision stress, or the work done on the zinc particles per unit area in unit time. The evolution of the coatings encompasses the nucleation, formation and coalescence of discrete islands, the formation and thickening of continuous coatings, and the exfoliation of those continuous coatings.

Figure 17.

The SEM images of the surfaces of the Zn-coated Al2O3 balls following the ball milling at 300 rpm: (a) 4 h, (b) 8 h, (c) 12 h, (d) 16 h, (e) 20 h and (f) 26 h, (g) illustrates the average thickness of the coatings as a function of milling time at different rotational speeds, (h) presents the required time to achieve continuous Zn coatings based on collision strength or collision power. Adapted with permission from ref. [67] Copyright 2012 Powder Technology.

The SEM images of the surfaces of Zn-coated Al2O3 balls after the milling operation at 300 rpm are presented in Figure 17. In these images, the dark areas represent the surfaces of the Al2O3 balls, while the gray areas indicate the Zn coatings. The progression of the Zn coatings during the milling process is clearly observable. As milling time increases, a greater number of Zn powder particles adhered to the surfaces of the Al2O3 balls. By the 8 h mark, continuous Zn coatings had formed (Figure 17b). However, with an increase in milling time beyond 16 h, some portions of the Zn coatings began to peel away, exposing the surfaces of the Al2O3 balls once again (Figure 17e,f).

As illustrated in Figure 17g, it can be observed that the average thickness initially increased, reached its peak, and then subsequently decreased, regardless of the rotation speeds of 200, 300, or 400 rpm. Higher rotation speeds expedited the evolution of the average thickness. These findings align well with the previously discussed analysis on the evolution of the coatings. Figure 17h illustrates the time required to form continuous Zn coatings, denoted as t, as a function of the collision strength or collision power. The constant C (h) is influenced by the characteristics of the metal powder particles and the grinding balls. D and F are negative constants determined by the geometry of the bowl and planetary ball mill, as well as the size of the grinding balls. The dimensional units for D and F are m2·s·N−1 and m2·s·J−1, respectively. In this study, C was calculated to be e4.52, while D and F were found to be −2.01 × 10−2 and −9.12 × 10−2, respectively. The variable ωp represents the rotation speed of the planetary ball mill (rad·s−1), while ωb denotes the rotation speed of the bowl, which is equal to ωp/Tr. K is a constant based on the ball diameter and is estimated to be approximately 1.5 (r−1) for balls with diameters ranging from 8 to 10 mm. Due to the lack of data for balls with a diameter of 1 mm, the influence of the ball diameter in this case is considered negligible. Therefore, the values for the 8–10 mm diameter balls will be utilized to evaluate the collision frequency for an Al2O3 ball.

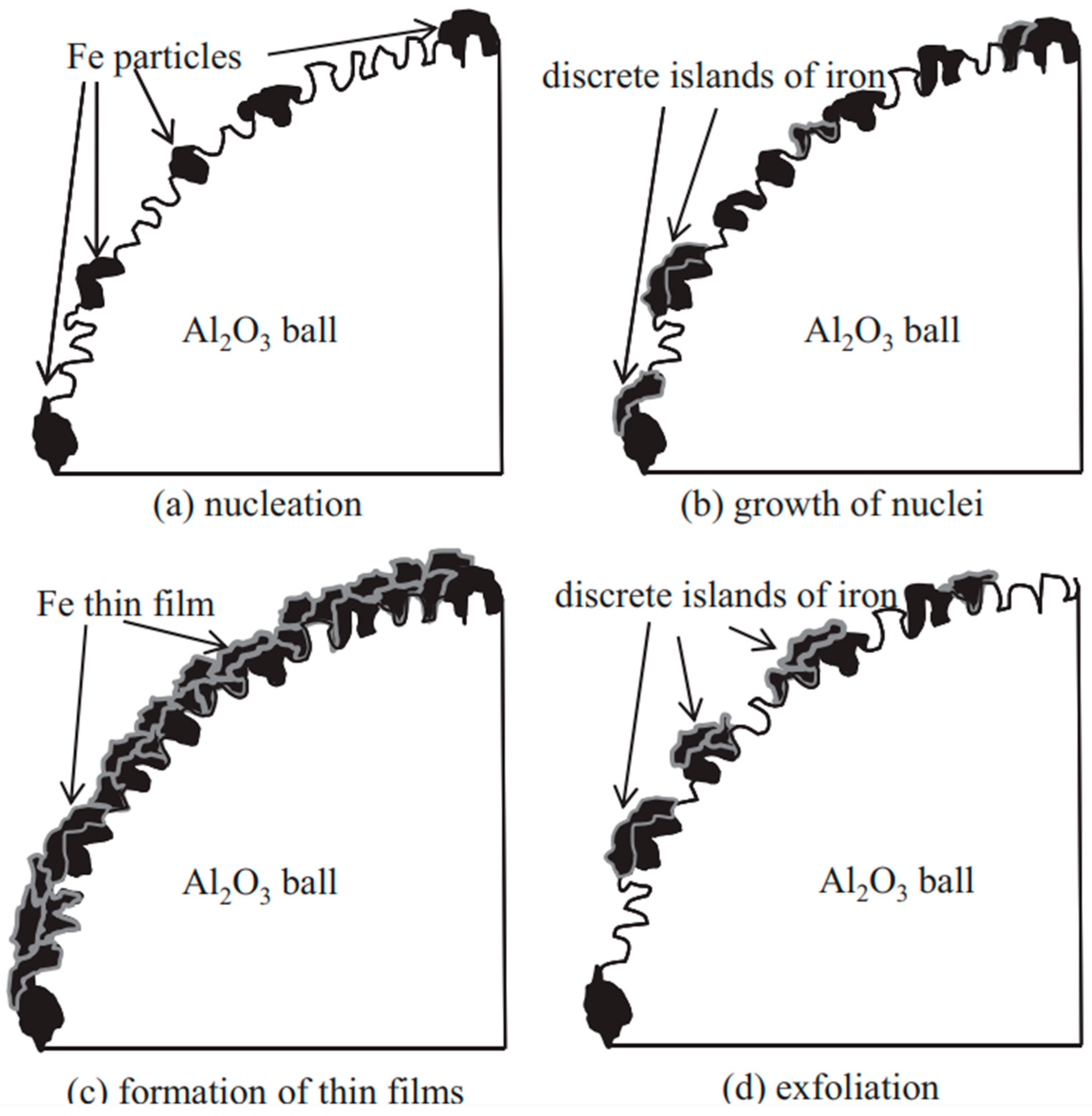

In the initial phase of the milling process, several zinc clusters transfer from Zn powder particles to the surfaces of Al2O3 balls due to friction and abrasion. The adhesive strength of metals varies, which is mainly influenced by their electronic structure and the extent of charge transfer between the adsorbed metal and the surface. The adhesion of Zn clusters to the Al2O3 ball surfaces is referred to as “nucleation.” It is important to note that this type of nucleation differs from the transition of metal from a liquid to a solid phase; it specifically involves the adhesion of solid metal clusters to the surface of solid ceramics. The size of these “nuclei” typically ranges from several nanometers to several hundred nanometers.

Subsequently, additional zinc clusters transferred and adhered to the surfaces of Al2O3 balls or to the existing Zn nuclei. The increase in size of the Zn nuclei is due to cold welding between the Zn powder particles and the nuclei, leading to the formation of discrete Zn islands. This mode of film growth is referred to as island-type or Volmer–Weber growth [68]. Following this, Zn particles attached themselves to the discrete islands and the nuclei, resulting in the coalescence of these islands; this phase is known as the formation and coalescence of discrete islands. The mechanical interlocking of Zn particles with the surface irregularities of the Al2O3 balls likely promoted the formation of these discrete islands [69]. During this stage, the surface coverage of Al2O3 balls with Zn increased rapidly. Cold welding was the predominant mechanism at this point. In the third stage, the surfaces of the Al2O3 balls became coated with Zn, culminating in nearly 100% surface coverage. This indicates the formation of continuous Zn coatings. Then, the cold welding between the zinc particles and the coatings continued, resulting in an increase in the thickness of the coatings. This phase is referred to as the formation and thickening of continuous coatings. In the final stage, the continuous Zn coatings began to peel off. During the development of these continuous coatings, internal stress was induced due to work hardening and the discrepancies in the thermal expansion coefficients of the Al2O3 ball coatings. As the thickness of the coatings increased, so did the internal stress. This internal stress subsequently weakened the adhesion of the coatings to the surfaces of the Al2O3 balls.

The process of forging fracture also plays a significant role in the exfoliation of coatings. After undergoing repetitive plastic deformation, the zinc powder particles and the continuous coatings become brittle due to work hardening. When Zn-coated Al2O3 balls collide with the inner wall of the bowl, a crack may initiate once a critical tensile strain is achieved. Following this, crack propagation occurs when the rate of plastic energy release surpasses a threshold characteristic of the material. Maurice and Courtney have outlined the fragmentation mechanisms of metal powder particles [70]. In summary, the exfoliation of continuous coatings arises from the combined effects of internal stress and external collision stress. This stage is referred to as the exfoliation of continuous coatings.

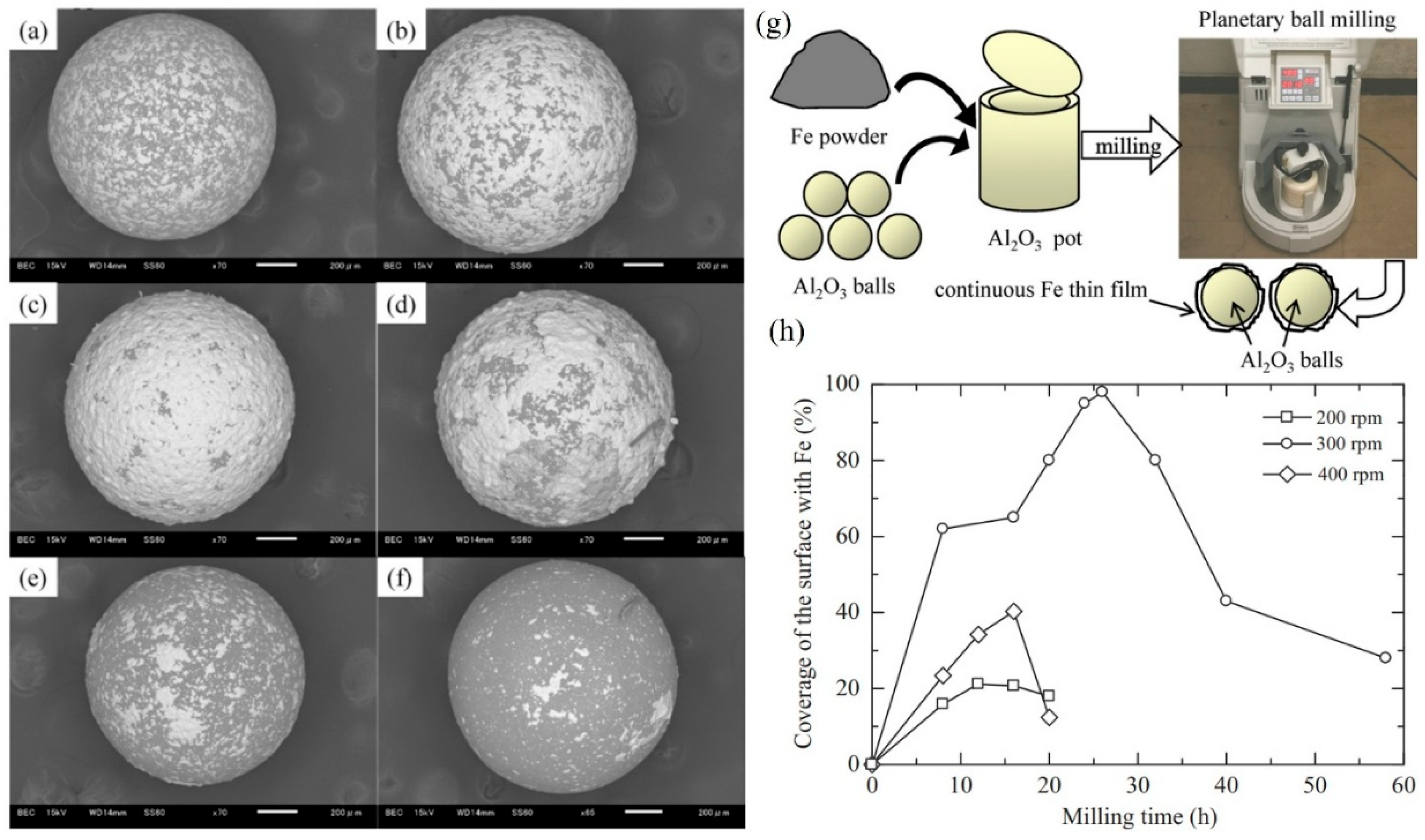

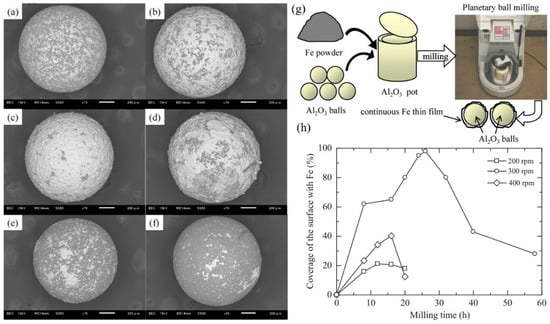

3.2. Iron (Fe) Coating on Alumina (Al2O3) Balls

Hao et al. also reported and discussed the influence of the processing parameters on the formation of iron thin films on Al2O3 balls by the ball milling coating technique (Figure 18a–g) [71]. The Fe particles reacted with oxygen in the atmospheric air, leading to the formation of ferro-ferric oxide, which impeded the creation of thin films. The rotation speed also significantly influenced the outcome. Continuous Fe thin films, with an average thickness of approximately 10 µm, were produced during the milling operation at 300 rpm; however, they could not be achieved at 200 and 400 rpm (Figure 18h) [71]. This apparent anomaly can be rationalized by considering the balance between impact energy and oxidation kinetics. At 200 rpm, the collision energy is too low to fracture the oxide barrier, preventing metallic bonding. At 400 rpm, the excessive energy leads to severe particle fragmentation and localized heating, which accelerates re-oxidation and hinders stable film growth. At 300 rpm, however, the collision energy lies within a critical window: it is sufficient to disrupt surface oxides and expose fresh metal, but not so high as to favor rapid re-oxidation. The plastic deformation that follows enables metallic contact and cold welding, allowing a continuous film to form despite the oxygen-present environment. Thus, 300 rpm represents an optimal impact-energy regime where oxide breakdown and film formation outweigh oxidation.

Figure 18.

The SEM images of the surfaces of the Fe-coated Al2O3 balls following the ball milling at 300 rpm: (a) 8 h, (b) 20 h, (c) 26 h, (d) 32 h, (e) 40 h and (f) 58 h, (g) illustrates the schematic Fe-coating onto Al2O3 balls, and (h) surface coverage as function of milling time at different rpms. Adapted with permission from ref. [71] Copyright 2012 Journal of Materials Processing Technology.

Additionally, the development of thin films was studied and analyzed. This progression was observed to involve nucleation, growth of nuclei, thin film formation, and exfoliation. It was determined that mechanical interlocking played a crucial role in the formation of these thin films.

At the beginning of the milling operation, Fe particles were immobilized either between Al2O3 balls or between the Al2O3 balls and the surface of the milling pot. Under the action of impact force, numerous small Fe particles became embedded in the pores, cavities, and other irregularities of the surfaces of the Al2O3 balls (“nucleation” Figure 19a) [71]. The air trapped at these surfaces was displaced by the Fe particles. In the initial stages of milling, the Fe particles were relatively soft and underwent plastic deformation due to repeated impact forces. This deformation led to the creation of new particle surfaces before they adhered to the Al2O3 balls. The generation of these new surfaces facilitated adhesion between the impacted Fe particles and the Fe coatings previously formed on the Al2O3 balls. This adhesion aligns with the weld theory of metal particles discussed in earlier studies [5]. This phenomenon is referred to as the “growth of nuclei” (Figure 19b) [71]. and occurs as a result of direct or angled impact forces rather than through friction. During milling at 200 rpm, the formation of thin films was unsuccessful, likely due to the insufficient impact force.

Figure 19.

Coating of Fe thin films onto Al2O3 balls using the ball milling process. Adapted with permission from ref. [71] Copyright 2012 Journal of Materials Processing Technology.

As discrete islands of iron grew, more iron particles were deposited on and around them, leading to an increased coverage of the Al2O3 ball surfaces with iron. At milling times of 16 and 26 h during operation at 300 rpm, the surface coverage reached 65% and 98%, respectively (Figure 19) [71]. Continuous thin films began to form after 26 h, and the thickness of these films continued to increase. This process is referred to as the “formation of thin films” (Figure 19c) [71]. However, as the continuous Fe thin films underwent further plastic deformation, they became work-hardened and consequently brittle. Under repeated impacts, portions of these thin films, which were mechanically interlocked with the Al2O3 balls, could fracture. The mechanical interlocking between the thin films and Al2O3 balls may have weakened over time. The mechanical interlocking force was considered the primary adhesive force. Moreover, the internal stress within the thin films increased with their thickness [68]. Once the internal stress exceeded the adhesive force between the thin films and the Al2O3 balls, the films began to peel off. This phenomenon is known as “exfoliation” (Figure 19d) [71].

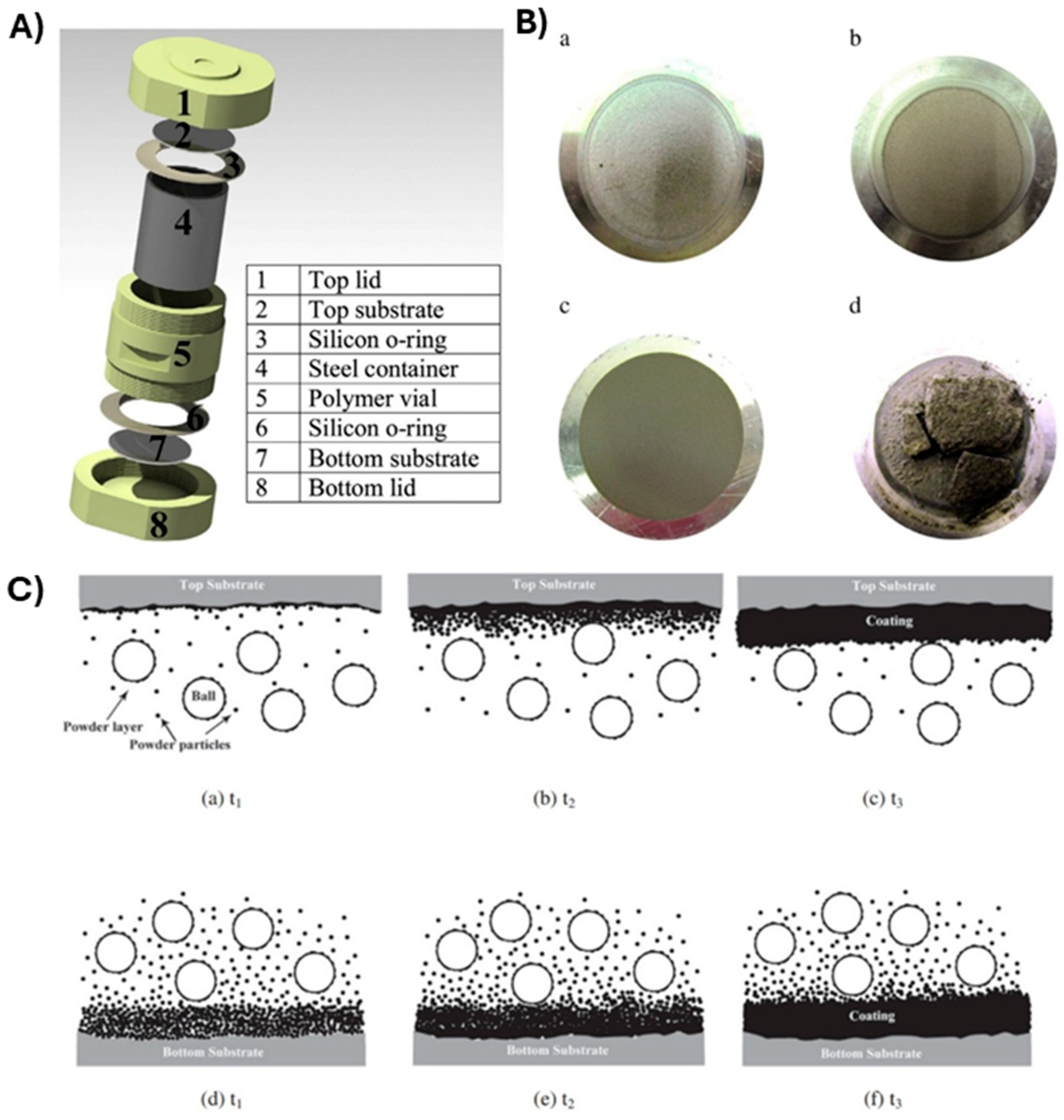

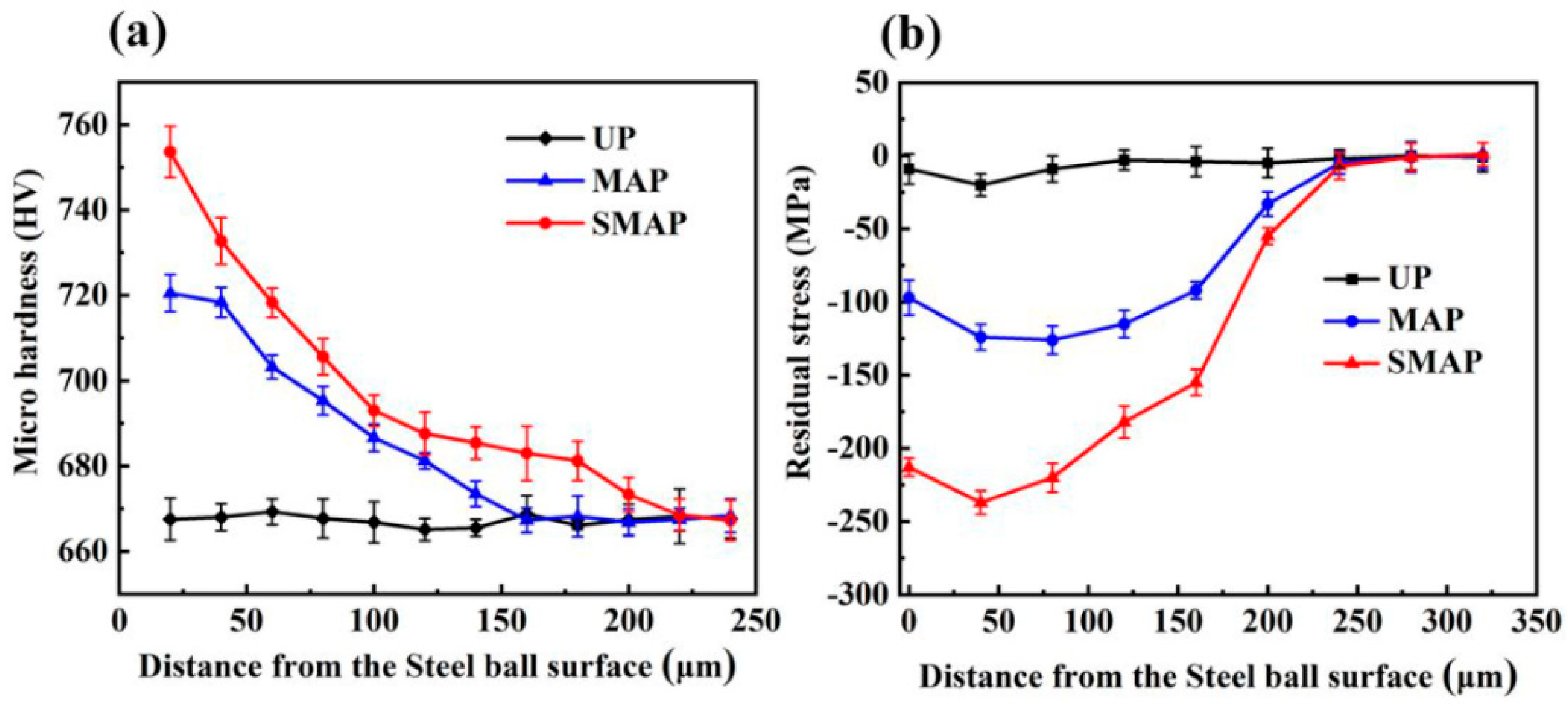

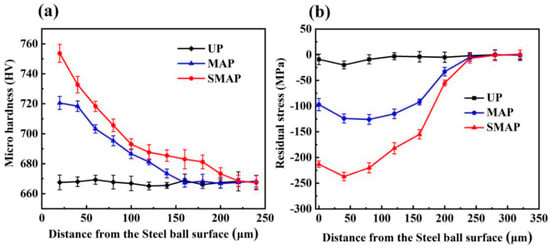

3.3. Mechanism of Formation of Nanostructured Coatings on Disk Metal Substrates Using Ball-Milling Process

Yazdani et al. studied Ni and SiC powders coating on Al disk substrates using the planetary ball-milling process [72]. Ni and SiC were individually used as coating materials that were mechanically deposited onto an Al substrate fixed at either the top or bottom of the milling vial (Figure 20A). Under the milling conditions applied in this study, the SiC coatings exhibited low microhardness and wear resistance, regardless of the substrate’s position, primarily due to inadequate consolidation (refer to Figure 20B). In contrast, the Ni coatings produced under similar milling conditions yielded excellent results (as shown in Figure 20C). It was observed that positioning the substrate at the top significantly enhanced microhardness, wear resistance, and adhesion strength. The Ni coating on the top substrate, with an average crystallite size of approximately 58 nm, demonstrated a microhardness of 422 ± 12 HV, which is at least 30% higher than that of a typical electroplated Ni coating. The variation in coating characteristics between the two substrate positions was attributed to differing deposition mechanisms.

Figure 20.

(A). Ni and SiC coating setup on Al disk substrates. (B). Photographs of (a) Ni-Top, (b) Ni-Bottom, (c) SiC-Top, and (d) SiC-Bottom coatings onto Al substrates. (C). Coating evolution on (a–c) the top and (d–f) the bottom of the Al substrate at three continued milling times (t1, t2, and t3). Adapted with permission from ref. [72] Copyright 2015 Powder Technology.

The different mechanisms for coating formation on the top and bottom substrates are illustrated in Figure 20C over three time sequences. For the top substrate, it is believed that most of the powder is transferred from the surface of the ball to the substrate. Upon impact, loosely bonded particles on the colliding ball’s surface adhere to the substrate. Subsequent ball collisions increase the compaction of the coating and reduce micro voids. As the kinetic energy of the colliding balls is imparted to a small amount of powder on the substrate (shown in Figure 20C(a)), the powder gains the chance to be compressed into the substrate, potentially leading to cold welding. This process can create a metallurgical bond between the coating and the substrate. As milling continues, the sequential deposition and compaction mechanism leads to the accumulation of coating thickness with effective adhesion and cohesion (illustrated in Figure 20C(b,c)).

The formation of the coating on the bottom substrate is thought to occur through a different mechanism. As demonstrated in Figure 20C(d–f), a significant amount of starting powder accumulates on the bottom substrate due to gravity settling. Unlike the top substrate, the impact energy of the flying balls is distributed over a larger volume of powder on the bottom substrate, resulting in a lower degree of adhesion to the substrate. However, as milling continues, the compaction of the coating improves. Extended milling times enhance the cohesion of the coating and reduce the presence of microvoids. Thus, the formation mechanism can be primarily attributed to an initial lump sum deposition followed by successive compactions. In this context, the impact energy from the colliding balls is insufficient for the effective compaction and cold welding of a relatively thick layer of nickel deposit on the bottom substrate. This leads to non-uniform densification throughout the coating thickness, resulting in lower microhardness and a higher wear rate.

Understanding the coating mechanisms in ball milling techniques properly is crucial for researchers and industry experts looking to improve coating quality and efficiency for particular applications. Every mechanism plays a vital role in enhancing the ball milling process, which in turn results in the creation of superior materials and coatings. The movement of the ball (or particles) inside ball mills is depicted in Figure 21, which sheds light on how coating balls travel inside these mills.

Figure 21.

Schematic diagram of ball milling process for coating powders. Adapted with permission from ref. [73]. Copyright 2021 Metals.

During the use of ball milling for coating, various forces, impacts, and mechanisms take part in creating the final coated surfaces or newly produced particles with each collision. These include impact and attrition forces, as well as important coating mechanisms, governed by inertial forces—primarily centrifugal force and, in planetary or vibratory mills, the Coriolis force, which are one to two orders of magnitude greater than gravity. Consequently, gravitational effects can be disregarded, and the true mechanism of coating formation is collision energy transfer, assisted by mechanical alloying [44,56].

Impact forces are created when milling balls collide with each other and with the coating material, generating high energy. This dispersion of the coating material onto the substrate results in the formation of a uniform and densely layered coating, effectively improving the coatings’ adhesion and durability.

Meanwhile, attrition forces are created when the grinding balls hit each other and against the container walls. This collision produces frictional forces that shear the particles, which helps distribute the coating substance evenly throughout the milled particles.

The gravitational effect involves movement of the milling balls within the coating material, resulting in the gradual formation of layers due to the impact of gravity.

In comparison, the rotation effect includes the rolling motion of the milling balls caused by the rotation movement of the milling container, which facilitates the uniform distribution of the coating material across the particles.

Conversely, the mechanical alloying process is used predominantly beside coatings to produce composite materials. In this process, particles are forced together by energy transfer and mechanical collisions and friction. This mechanical activity results in the formation of new alloys, which is achieved through cold welding [3,4,5,9,10,44,74].

Cold-welding phenomena contribute to the formation of agglomerates and the consolidation of particles, leading to the production of unique structures and properties. The interplay of these forces, impacts, and mechanisms not only influences the morphology and composition of the coated surfaces but also affects their functional properties, such as hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance [5,8,28,29,30,44,75]. Therefore, understanding and controlling these processes are essential for achieving desired coating characteristics and optimizing the performance of coated materials in various applications.

4. Parameters Affecting Coating Efficiency

Coating parameters play a critical role in determining the efficiency and quality of the coat produced by various coating methods. Therefore, it is crucial to thoroughly examine these parameters to enhance and optimize the coating process. There are two sets of parameters to consider: process parameters (e.g., the ratio of balls to powder, milling time and speed, ball size) and the intrinsic material properties of the coating material and the coated particle (such as hardness, structure, and chemistry) [11,76,77].

4.1. Applied Ball Milling Process Parameters

4.1.1. Ball to Powder Ratio (BPR)

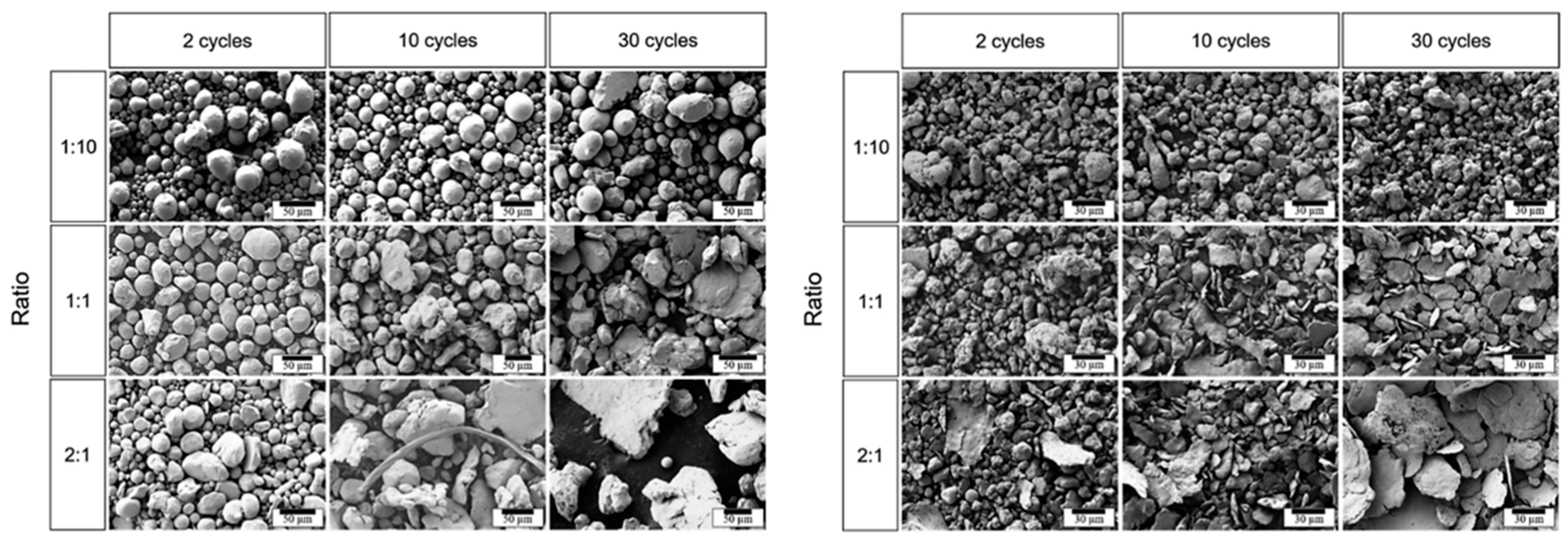

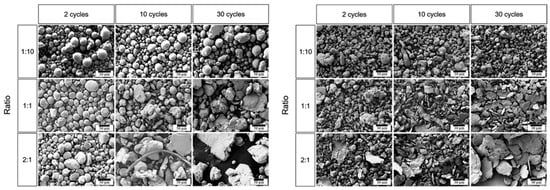

The BPR is considered a key parameter in determining the coating efficiency of ball milling, measured by coating coverage, adhesion, and minimal contamination. Increasing the BPR results in a more efficient coating process. This happens because a higher ratio provides additional energy and creates more contact surfaces, which ultimately leads to improved coating performance. Studies have shown that key powder properties (morphology, hardness) can change more with BPR than with milling duration. For example, Ansell et al. conducted a study on the impact of high-energy ball milling (HEBM) on spherical Cu and stainless steel powders. Their research focused on how varying the BPR influences several factors, including the morphology (Figure 22), particle size, and hardness of the powders. These factors are significant as they directly affect the flow characteristics and adhesion properties of the powders in additive manufacturing applications [14,25,78]. For instance, increasing BPR leads to faster work-hardening of powders: high BPR can raise powder hardness in minutes, whereas at low BPR, similar hardening may take hours. An optimal BPR promotes efficient coating by providing sufficient impacts for particle adhesion without causing excessive fracturing of either the powder or the nascent coating [14,25,78].

Figure 22.

SEM images of (Left) milled 316L stainless steel powders and (Right) milled Cu powders processed at different BPRs and under varying cycles. Modified and adapted with permission from ref. [78] Copyright 2021 Particulate Science and Technology.

It is noteworthy that the ratio of ball weight to powder weight is an important economic factor in milling processes. Increasing this ratio results in higher output, improving efficiency in terms of coating coverage and energy use, while also supporting industrial scalability. These improvements are closely connected to the properties of the final product and the specific requirements of the milling process [11,14,28,78,79].

4.1.2. Milling Time and Speed

The duration and speed of the milling process are other crucial factors in defining the final coating properties. The duration of milling significantly impacts the thickness and uniformity of the coating. Meanwhile, the speed of the milling process influences the quality of the coating.

Milling Time

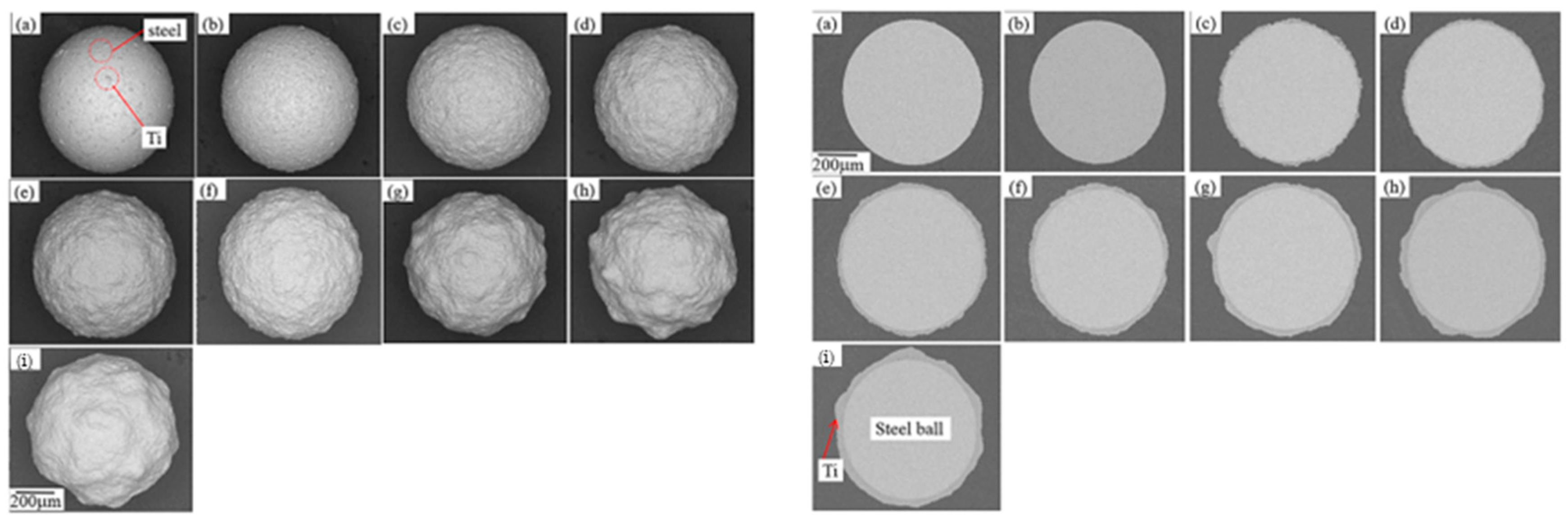

Longer milling times result in finer particle sizes and thicker, more uniform coatings due to the increased frequency of powder impacts. Initially, this process enhances both coating thickness and coverage. However, excessive milling may lead to complications such as particle agglomeration, contamination, and phase transformations caused by heat generation (Figure 23). Furthermore, beyond a certain duration, the coating may become saturated or even experience delamination, entering an exfoliation stage [25,30,80].

Figure 23.

SEM images for the (Left) surface morphologies and (Right) cross-section of the samples prepared by mechanical coating at 300 rpm after different durations: (a) 4 h; (b) 8 h; (c) 10 h; (d) 12 h; (e) 16 h; (f) 20 h; (g) 26 h; (h) 32 h; and (i) 50 h. Modified and adapted with permission from ref. [80] Copyright 2017 Coatings.

Rotational Speed

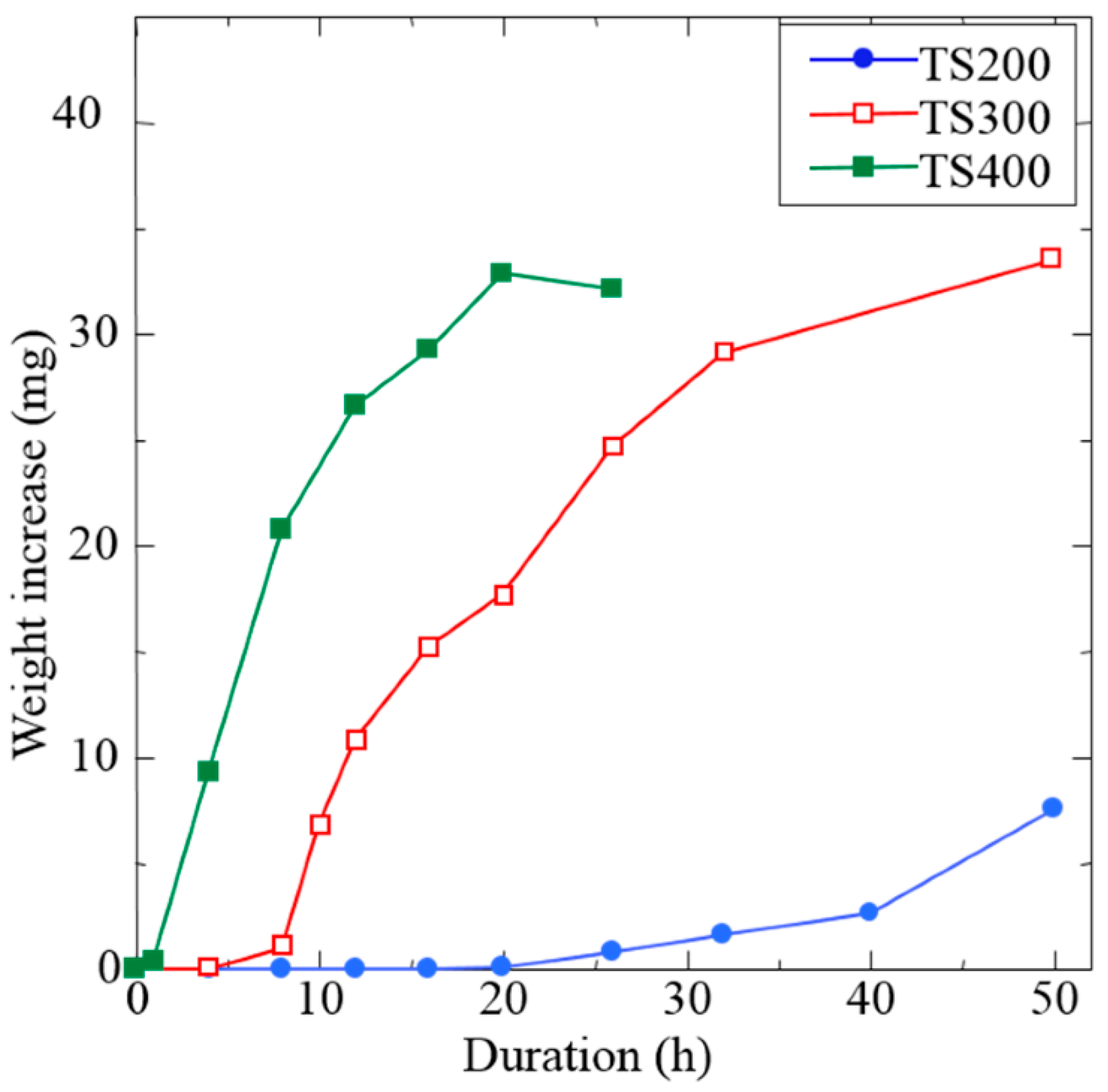

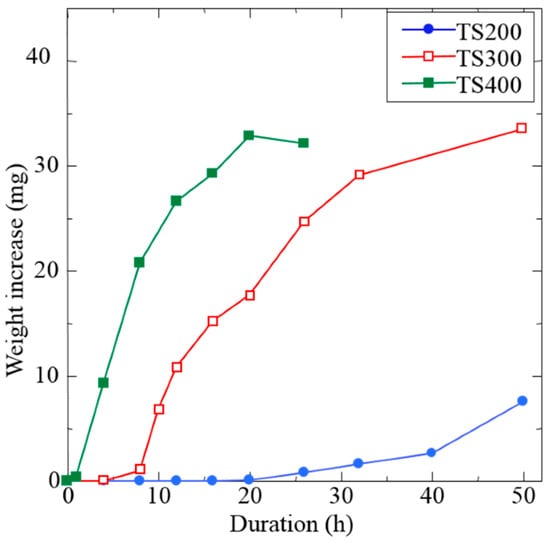

The rotation speed of the milling process strongly influences the quality of the coating. Higher speeds impart greater kinetic energy, which can accelerate coating formation; e.g., faster revolutions produce continuous coatings sooner. In one study, increasing the rotation speed from 200 to 400 rpm dramatically increased the metal deposition rate on balls [80]. Yet, excessive speed can be detrimental: very high speeds lead to early coating peeling as the intense impacts cause the formed layers to spall off. There is thus an optimal intermediate speed for maximum coating efficiency, defined by strong adhesion and minimized contamination, while remaining practical for large-scale production. For instance, Ni coating on ZrO2 balls grew fastest at ~240 rpm for 15 h, whereas at 270 rpm the coating began to exfoliate earlier [25,30]. This balance is illustrated in Figure 24, which shows the weight gain of substrate balls over time at different milling speeds. Higher speeds yield a steeper initial weight increase (faster coating) but can reach a plateau or decline once the coating starts to detach at long times [25,80].

Figure 24.

Weight increase in substrate balls versus milling time at three rotation speeds (200 rpm in blue, 300 rpm in red, 400 rpm in green). Higher rotation speed accelerates coating growth, but an excessively high speed (green) leads to an earlier saturation and slight decrease in net coating mass due to exfoliation of the over-thickened coating. Adapted with permission from ref. [80] Copyright 2017 Coatings.

Conversely, shorter milling times may lead to a thinner coating but may also result in incomplete substrate coverage [62].

Overall, a higher milling speed may result in a thinner and more uniform coating distribution, while a lower speed could lead to a thicker and less uniform coating. It is vital to note that each material system has an ideal speed range for efficient milling. Exceeding this range can cause overheating and material degradation, while speeds that are too low may not provide enough energy for effective milling [5,9,25,27,44,61,77].

4.1.3. Influence of Ball Size

The size of milling balls is a crucial factor that affects the impact energy and contact area during collisions in milling processes. Larger balls provide higher impact forces, which can enhance the deformation of powder particles and the substrate surface, making them advantageous for applications like cold welding and coating deposition [56,76]. However, excessively large impacts can also result in particle pulverization or the dislodgment of coatings if the energy is too high.

On the other hand, smaller balls generate lower force impacts but do so in larger quantities, leading to increased collision frequency and more uniform dispersion of powder impacts [56,76]. This can facilitate the formation of finer and more homogeneous coatings. Nevertheless, if the balls are too small, the impact energy may fall short of achieving the necessary plastic deformation for harder particles, which can reducing coating efficiency as measured by adhesion quality and scalability to industrial milling

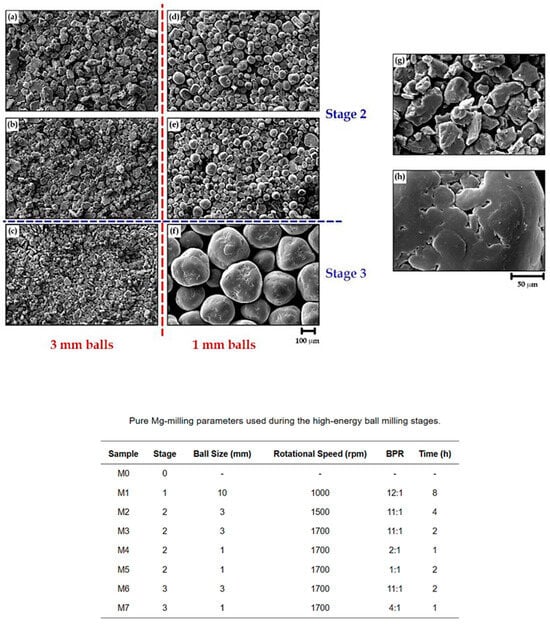

Overall, the impact energy produced during milling is closely tied to ball size, significantly influencing the final quality of the mechanical coatings. Larger balls excel at breaking down coarse particles, whereas smaller balls are more effective for grinding fine particles and achieving narrow size distributions and uniform coatings (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

SEM images show the resulting morphologies following the second and third milling stages with 3 and 1 mm balls. (a) M2, (b) M3, (c) M6, (d) M4, (e) M5 and (f) M7. (g,h) are enlargements of those in (c,f), respectively. Modified and adapted with permission from ref. [76] Copyright 2021 Metals.

In the milling process, achieving an optimal balance in ball size distribution is crucial for effective results. Fine balls are beneficial for adhering and burnishing coating particles onto surfaces, while larger balls provide the necessary impact energy to deform and weld those particles. The selection of ball size depends on several factors, including the material being milled, the desired final particle size, the duration of milling, and the intended application. By carefully tuning the ball size along with other parameters like ball-to-powder ratio, milling time, and speed, one can ensure that powder particles adhere effectively instead of being reduced to dust. Experimental studies show that utilizing a mixed particle size distribution leads to improved efficiency, reflected in more uniform coatings and reproducible performance at scale [5,30,44,48,76].

4.2. Intrinsic Material Properties

4.2.1. Material Properties

The efficiency of coated balls, understood as their ability to achieve durable coatings and scalable production, relies heavily on the properties of the materials being milled. Yet, surprisingly, there is a lack of comprehensive information on this topic in the existing literature. Key parameters related to material properties have been notably overlooked in the study of mechanical processing techniques for ball coating. The physical and chemical properties of the coating material, such as hardness, ductility, and reactivity, directly influence its ability to adhere to the balls. As an illustration, hard materials need more energy and longer milling times, resulting in increased equipment wear, while soft materials are easier to grind and require less energy. Furthermore, heat-sensitive materials require careful temperature control during milling to prevent degradation and melting, while thermally stable materials can endure higher temperatures and more aggressive milling conditions [5].

It is imperative to thoroughly understand the various properties involved in the milling operation, such as hardness, density, and particle size distribution, and optimize them accordingly. This can significantly enhance efficiency, both in terms of coating performance (adhesion, uniformity) and industrial effectiveness (cost, throughput, reproducibility). This, in turn, contributes to the improvement of key material properties, such as strength and durability, ultimately leading to enhanced performance of the milled materials in their intended applications. Furthermore, the complex and labyrinthine nature of the material’s structure and morphology significantly impacts the effective participation of balls in the coating process [28,44]. This knowledge gap underscores the urgent need for further research and data collection in this field.

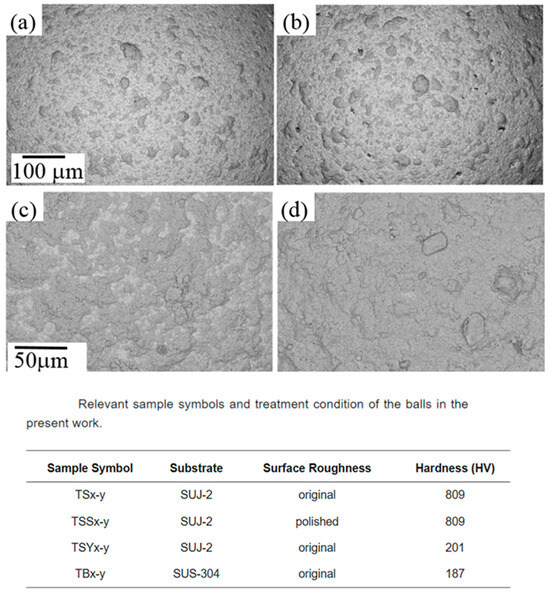

4.2.2. Hardness

The hardness of both the substrate and coating material critically determines coating efficiency. A softer substrate surface is more amenable to coating deposition as it can undergo local plastic deformation to “grab” and hold incoming particles [80]. For example, steel balls (softer than ceramic) accept metal coatings more readily than extremely hard ceramic balls, which offer little yielding or mechanical interlocking [80]. If the powder to be coated is much harder than the substrate, it may peen and indent the substrate, embedding itself more firmly. Conversely, a very hard substrate tends to cause rebounding or shattering of incoming particles rather than bonding. Thus, lower substrate hardness generally promotes coating formation in mechanical milling (Figure 26) [80]. Hardness of the coating material itself also matters: extremely hard brittle powders might not deform enough to weld onto the substrate, whereas a moderately hard but still deformable powder can flatten and adhere under impact.

Figure 26.

SEM images of morphologies of the samples: (a) TS300-4; (b) TSS300-4; (c) TS300-8; and (d) TSY300-8. Modified and adapted with permission from ref. [80] Copyright 2017 Coatings.

Ductility

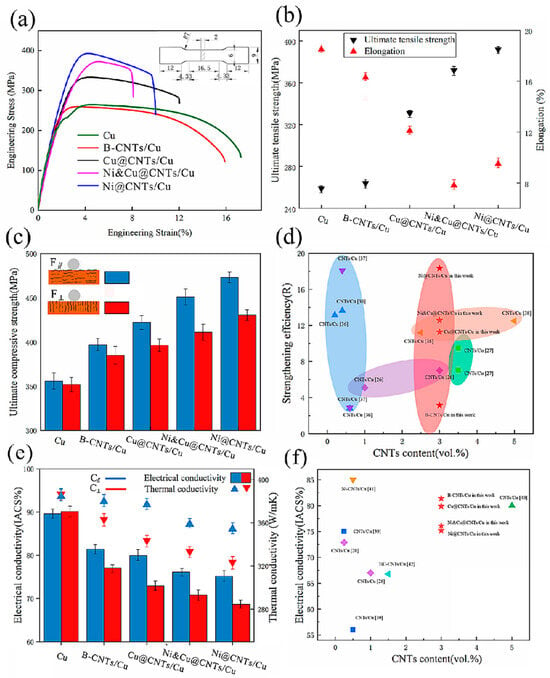

Ductility (plastic deformability) of the coating metal is a key enabler of cold welding. High-ductility metals (e.g., Au, Cu, soft Al) can endure repeated collisions by flattening and smearing onto surfaces, which fosters continuous coating build-up [81,82]. In contrast, brittle or low-ductility materials (e.g., ceramics, hard intermetallics) tend to fracture instead of plastically flowing, hindering the formation of a uniform coat. As one study noted, the better the plastic deformability of a metal powder, the easier it is for particles to cold-weld together and form thicker continuous coatings [81]. Ductile particles effectively “stick” to each other and the substrate upon impact, whereas brittle ones may pulverize into debris that does not adhere. Notably, insufficient ductility was a factor for Ni failing to form a continuous coating in a comparative experiment, where Ni’s work-hardening and lower plasticity (relative to Cu, Zn, etc.) limited its cold-weld behavior [81]. Thus, high ductility in the coating material correlates with higher coating efficiency, here expressed as greater adhesion quality and reliability under scalable milling conditions.

For example, Luo et al. showed that combining ball milling with Cu coating on CNTs and high-temperature sintering enhances the dispersion of CNTs and their interfacial bonding. This improves the ductility of the Cu matrix, addressing coating efficiency by optimizing the intrinsic material property of ductility through interfacial and processing control [83]. Figure 27 illustrates the enhanced ductility achieved through interfacial engineering. Specifically, the application of a Cu coating on CNTs, combined with ball milling and high-temperature sintering, leads to improved dispersion and stronger interfacial bonding between CNTs and the Cu matrix. This results in composites exhibiting higher elongation at fracture compared to those with uncoated CNTs, indicating improved ductility [83].

Figure 27.

(a) Stress–strain curves, (b) ultimate tensile strength and elongation, (c) compressive strength of samples. (d) Rvalue of CNTs in this work compared with data in the literature (e) Electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity of samples. F∥, C∥ test plane parallel to the drawing direction, F⊥, C⊥ test plane perpendicular to the drawing direction. (f) Electrical conductivity of samples compared with the published data. Adapted with permission from ref. [83] Copyright 2022 Nanomaterials.

Surface Energy

Materials with high surface energy (and clean, oxide-free surfaces) have a greater driving force for bonding upon contact. In mechanical coating, high surface-energy metals tend to cold-weld more readily, since clean metal–metal contacts can form metallic bonds under pressure. Conversely, metals that rapidly form stable surface oxides or possess lower surface energy present a barrier to cold welding. For example, Al powders quickly develop an oxide layer that impedes direct metal contact, making mechanical coating more difficult unless that oxide is disrupted. In general, a high surface energy and chemically “clean” surface helps particles adhere during collisions [81]. This is closely related to chemical affinity: if the coating metal can form a strong interfacial bond with the substrate (either metallic bonding or some reactive adhesion), the coating will nucleate and grow more effectively. Surface treatments or process control (e.g., milling under inert gas or adding a PCA) are sometimes used to manage surface oxide films, essentially to raise the effective surface energy of particles so that cold welding can occur. For example, Hao and his colleagues discovered that metals with higher surface energy can improve adhesion between the coating material and the substrate. This enhanced adhesion facilitates better bonding during the mechanical coating process. As a result, it contributes to the formation of uniform and durable coatings. This finding underscores the importance of surface energy as a key material property that influences coating efficiency [81].

Thermal Conductivity

The thermal conductivity of the materials influences local heating and cooling during impact events. Each collision in high-energy milling generates heat at the contact interface. Low thermal conductivity materials (e.g., ceramics, polymers, or metals like titanium with relatively lower conductivity) will retain that heat longer at the impact site, potentially softening the particle or substrate locally and promoting bonding. High thermal conductivity materials (e.g., Cu) dissipate heat quickly into the bulk, so the interface cools rapidly [84]. While milling is predominantly a room-temperature process, these rapid thermal exchanges can affect coating efficiency: a brief localized softening can assist particle bonding. In practice, the effect is subtle, but it has been suggested that harder balls with high thermal conductivity (like steel) may remove heat from the collision zone, whereas lower conductivity media (like ceramic balls) allow higher interface temperatures leading to better particle adhesion [85]. Indeed, one report identified the ball material’s thermal conductivity (along with hardness) as a key factor in coating effectiveness [85]. Overall, low conductivity of either the powder or the substrate tends to favor the “mechanical alloying” process by prolonging contact time at elevated temperature, thereby aiding consolidation of the coating.

Density

The density of the powder and substrate influences momentum transfer during milling. Higher-density particles (whether coating powder or milling media) carry more momentum at a given velocity, resulting in more forceful impacts. In mechanical coating, a dense coating powder can better penetrate any surface films and embed into the substrate upon impact. For instance, lead or tungsten-based particles (very dense) would hit with greater inertia than lighter Al particles, possibly improving their adhesion if the substrate can accommodate the impact. Similarly, dense milling balls (e.g., steel) impart larger impact forces than lighter ones (e.g., Al2O3) under the same speed [56]. This can enhance coating efficacy up to a point. However, if the density disparity is too high, lighter powder particles might simply rebound off heavy balls rather than deforming. An optimal matching of densities helps efficient energy transfer. Experiments comparing milling media found that stainless steel balls (~7.9 g/cc) generated higher collision forces and coating yields than lighter ceramic balls under identical conditions [56]. Thus, material density plays a role in how effectively kinetic energy is converted into plastic deformation and bonding in the coating process.

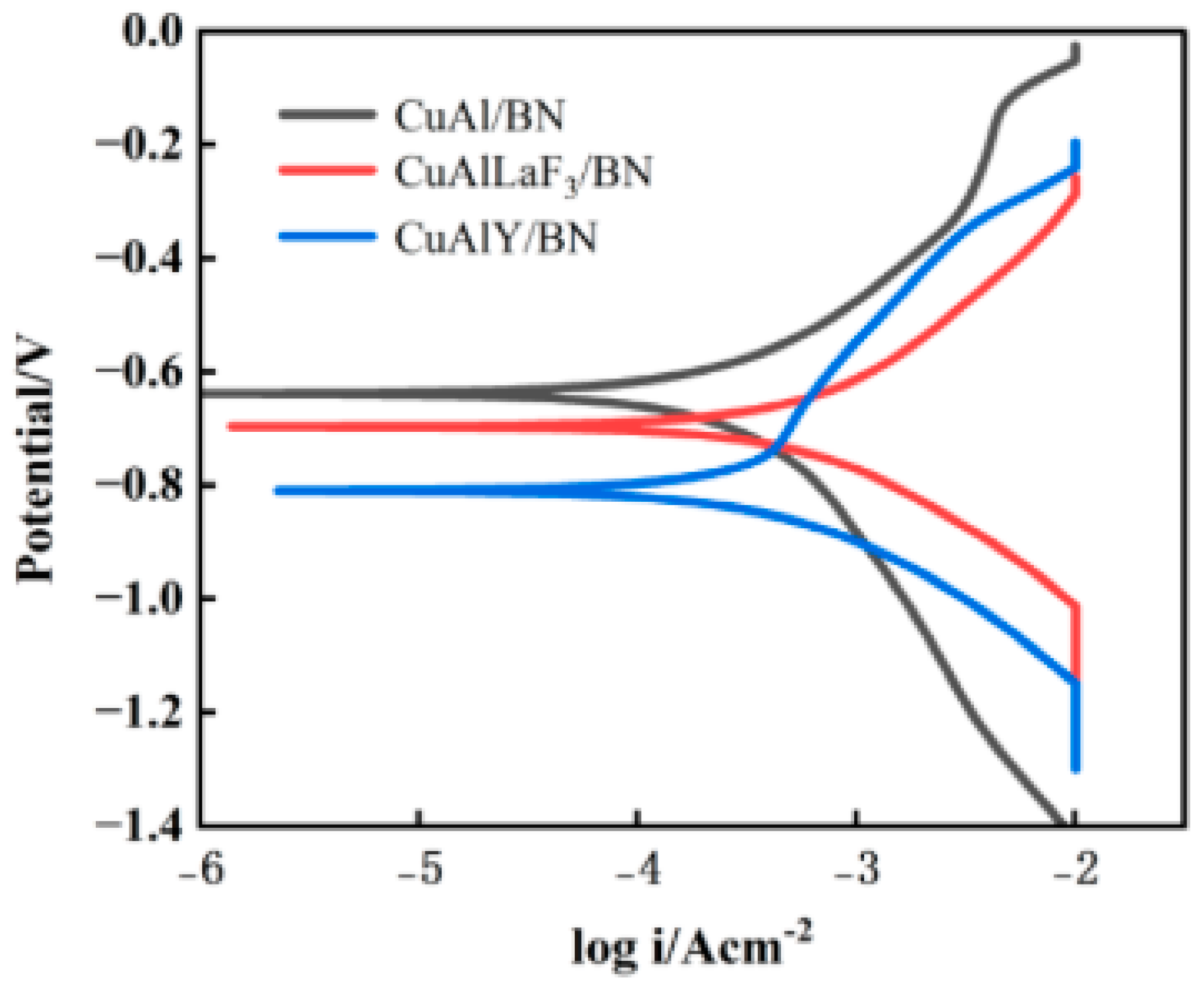

Chemical Affinity

Chemical compatibility or affinity between the coating material and the substrate strongly affects adhesion. If the two metals have mutual solubility or can form compounds, a chemical driving force may enhance bonding. For example, metals that tend to alloy or have low electronegativity can adhere more readily to ceramic or dissimilar substrates [81]. A study on coating Al2O3 balls with various metals showed that metals with lower electronegativity (more electropositive) covered the ceramic surface more completely in the initial stages [81]. This was attributed to their higher chemical reactivity leading to stronger interfacial adhesion (possibly via an oxide bridge or direct bonding). In contrast, metals like Ni (with higher electronegativity) had poorer initial attachment on ceramic, failing to form a continuous coat [81]. Chemical affinity also encompasses the tendency to avoid interfacial brittle phases: if the coating and substrate react to form a brittle intermetallic, the coating may spall. Ideally, the coating material should either inertly adhere or form a thin diffusion bond without adverse phases. In summary, coatings form more efficiently when there is a favorable chemical or metallurgical interaction at the interface (short of any deleterious reaction). This can be seen as an analog to plating materials that “wet” or bond each other, which will mechanically coat more easily than those that are chemically repellent.

Crystal Structure and Deformation Behavior