Abstract

Carbon–metal composite NiCrFeC coatings, prepared with and without controlled oxygen addition, were investigated to evaluate the influence of oxygen on the structure, mechanical response, and tribological performance. X-ray diffraction revealed that oxygen-containing films (NiCrFeC + O2) exhibit a mixed metallic–oxide microstructure with CrNi, CrO, and NiO phases, whereas oxygen-free coatings show only CrNi crystalline peaks. The incorporation of oxygen led to a substantial increase in nano-hardness, from 0.84 GPa for NiCrFeC to 1.59 GPa for NiCrFeC + O2. Scratch testing up to 100 N indicated improved adhesion and higher critical loads for the oxygen-rich coatings. Tribological measurements performed under dry sliding conditions using a sapphire ball showed a significant reduction in friction: NiCrFeC + O2 stabilized at ~0.20, while NiCrFeC exhibited values between 0.25 and 0.35 at 0.5 N and 0.4–0.5 at 1 N, accompanied by non-uniform sliding due to coating failure. Wear-track analysis confirmed shallower penetration depths and narrower wear scars for NiCrFeC + O2, despite similar initial roughness (~35 nm). These findings demonstrate that oxygen incorporation enhances hardness, adhesion, and wear resistance while substantially lowering friction, making NiCrFeC + O2 coatings promising for low-friction dry-sliding applications.

1. Introduction

In modern engineering systems, the reduction in friction and wear at sliding or rolling contacts remains an important objective. In mechanical systems, frictional losses account for a large fraction of energy consumption. The resulting wear leads to component failure, maintenance cost, and resource consumption [1,2,3]. In this context, the development of advanced low-friction coatings has become a research priority. In the literature, two main solutions are proposed: the formation of an adsorbed layer or the formation of a tribofilm on the surface metals [4]. Among these, diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings have demonstrated resistance to wear and corrosion due to their high hardness and chemical stability [5,6,7,8,9]. Amorphous carbon coatings (a-C, ta-C) have been shown to exhibit low coefficients of friction (µ) under specific environmental and tribochemical conditions. For example, hydrogen-free tetrahedral amorphous carbon (ta-C) coatings paired with metallic counterparts can reach µ < 0.1 in vacuum or controlled atmospheres during short-term tests [10]. At a more fundamental level, ab initio molecular dynamics simulations have shown that the ultra-low friction of carbon-based films is closely linked to surface passivation mechanisms, including hydroxylation and the formation of thin hydrogen-bonded water layers on OH-terminated carbon surfaces during sliding [11]. More recent experimental studies have further expanded this framework by demonstrating that tailored DLC architectures can achieve macroscale superlubricity through the formation of adaptive tribofilms. In particular, Yi et al. reported extremely low friction coefficients (µ ≈ 0.002) for Si-doped hydrogenated amorphous carbon (a-C:H:Si) films lubricated with graphene oxide nanosheets, where tribochemical reactions led to the formation of silica-rich interfacial layers combined with lamellar GO films that effectively shifted the shear plane to low-shear GO/GO and silica/GO interfaces [12]. Related works have shown that Si incorporation in DLC promotes surface hydroxylation and stabilizes hydrated boundary layers, thereby extending superlubricity to ambient or liquid environments [13,14]. These studies highlight the central role of surface chemistry control, dopant selection, and tribofilm evolution in achieving ultra-low friction in DLC-based systems. Despite these advances, conventional DLC coatings remain affected by high residual stresses and limited chemical reactivity with lubricants, which can restrict tribofilm formation and long-term stability under high load or harsh operating conditions. Alloying or mixing carbon with metallic elements such as chromium or nickel has therefore been proposed as an alternative strategy to improve adhesion, reduce internal stresses, and introduce chemically active sites that enhance interfacial reactivity [8]. In such carbon–metal composite films, the carbon matrix provides hardness and chemical stability, while the metallic phase contributes to stress relaxation, load-bearing capability, and the formation of lubricious oxide or carbon-rich tribofilms during sliding, enabling low friction and wear under conditions beyond the typical operational window of pure DLC coatings.

In contrast to traditional DLC, Ni–Cr–Fe–C–O coatings derive their tribological behavior not from a fully sp2/sp3 carbon network, but from the interaction between the metallic matrix and carbon-based or oxide-derived tribofilms. While DLC achieves low friction mainly through surface passivation and the formation of hydrogenated or hydroxylated shear layers, Ni–Cr–Fe–C–O systems operate through mechanisms that are different, yet conceptually related. These include solid-solution strengthening within the Ni–Cr–Fe matrix, shear accommodation in carbon-rich regions, and the development of lubricious oxide phases such as Cr2O3, NiO, and mixed oxides formed during sliding. Ni-based alloys are already established in tribological applications due to their toughness, metallurgical compatibility, and their ability to host both hard and soft lubricating phases [12]. Chromium contributes through the formation of dense Cr2O3 surface layers that improve oxidation resistance and stabilize friction [13], while Fe enhances the load-bearing capability through solid-solution strengthening [13]. Recent work on composite Ni-based architectures further demonstrates that incorporating soft lubricants such as PTFE or MoS2 leads to significant friction and wear reductions—up to 83% and 93%, respectively—through the formation of adaptive tribofilms at the sliding interface [14]. Moreover, lamellar systems extend beyond carbon alone; graphene oxide nanosheets, for instance, were shown to reduce shear forces and improve lubrication through their high thermal conductivity and facile interlayer sliding, underscoring the broader relevance of layered lubricants for metallic composite surfaces [15]. Although the origins of low friction differ from those in classical DLC, the shared principles of tribofilm formation, shear-layer development, and surface-chemistry-driven friction modification define a clear conceptual link between DLC literature and the Ni–Cr–Fe–C–O coatings investigated in this study.

In this context, this report focuses on an anti-friction coating preparation designed for application on bearing shells used in internal combustion engines. The anti-friction layer is composed of Ni, Cr, and Fe as the main metallic constituents, combined with a solid lubricant phase (carbon) in an argon atmosphere, and compared with the same coating obtained in the Ar plus O2 gas mixture. The preparation process is based on the DC sputtering method [16,17,18] employing high-purity elemental sources for the considered depositions: (i) Inconel 600 steel (at least 72% nickel, 14–17% chromium, and 6–10% iron and (ii) the HiPIMS method [18,19] to deposit carbon as DLC/a-C mixed element. Surprisingly, the coating prepared when oxygen was added to the buffer gas shows better low friction properties. The production of carbon–metal composite coatings with minimal residual stresses, enhanced adhesion to the substrate, low friction coefficients, and uniform coverage across the substrates could be employed, for example, as semi-cylindrical bearing shells commonly employed in automotive applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Depositions

Carbon–metal composite coatings were obtained by DC sputtering using an Inconel 600 sputtering target (25 cm in diameter), operated at an applied voltage of 500 V and a DC power of 1 kW, together with a high-density graphite target sputtered by High-Power Impulse Magnetron Sputtering (HiPIMS). The HiPIMS discharge was operated at a pulse repetition frequency of 900 Hz with a pulse width of 65 µs, corresponding to a duty cycle of 5.9%, and an average power of 6 kW applied to the graphite target. A separate DC power supply was used to apply a substrate bias, operated at an average power of 1 kW. The depositions were performed in Ar and Ar + O2 atmospheres, with an Ar flow rate of 25 sccm for the oxygen-free samples, and Ar and O2 flow rates of 25 sccm and 5 sccm, respectively, for the oxygen-containing samples, resulting in NiCrFeC and NiCrFeC + O2 coatings. Prior to deposition, the samples were immersed in an ultrasonic cleaning bath containing a mixture of acetone and isopropyl alcohol. After extraction from the ultrasonic bath, they were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water and allowed to dry naturally in atmospheric air. Subsequently, the substrates were introduced into the deposition chamber and subjected to an in situ Ar plasma cleaning for 10 min, using an Ar flow rate of 25 sccm and an RF power source operating at 13 MHz, with an incident power of 500 W and a reflected power maintained between 0 and 5 W. After plasma cleaning, the chamber base pressure was set to 10−3 Pa, and the substrates were heated to 200 ± 10 °C. During deposition, a bias voltage of 50 V was applied to the substrate holder in order to accelerate ions and promote the formation of dense and adherent coatings. Neutral and ionic species generated in the plasma either moved freely or were accelerated in the electric field established between the targets and the substrates, enabling dense film growth. The working pressure during deposition was maintained at approximately 1 Pa, and the process parameters were adjusted to obtain film thicknesses in the range of 0.6–1 µm.

The substrates, consisting of Si, glass, and polished 304L stainless steel, were rotated at speeds between 10 and 60 rpm to ensure coating uniformity. The deposition geometry was kept constant for all experiments: the lateral distance between the two sputtering targets was approximately 200 mm, while the vertical distance between the target plane and the substrate line was approximately 150 mm. All C–metal films were deposited under similar conditions, with fixed source–substrate distances and real-time rate and thickness monitoring at the holder center, yielding a consistent series of samples for subsequent structural and tribological analyses. Although depositions were performed on Si, glass, and polished 304L stainless steel substrates, only the coatings deposited on stainless steel are considered in the present work, as they are directly relevant to the scope of the study.

2.2. Characterization Techniques

After the deposition was performed, the coatings were examined by morphological, compositional, microstructural, surface chemical, thickness, microhardness, and tribological analyses. The nano-hardness was measured using Histrion TI 100 nano indenter and friction properties were tested using a CSM ball bearing system in dry sliding; The scratch tests were conducted using a UMT-TriboLab system (Bruker); Phase composition was examined using a SmartLab diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with high-resolution incident beam optics and a rotating anode as CuKα1 source (λ = 1.540597 Å). Thickness and surface roughness were measured using a Dektak 150 profilometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) supplied with a 2.5 µm stylus. The surface morphology and elemental composition were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, TM3030Plus Tabletop, Hitachi (Tokyo, Japan)) coupled with a Quantax70 Bruker energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Phase Composition

Measurements were performed in a parallel-beam configuration in a 10–100° 2θ range, using an incidence angle of 1°, at a scanning speed of 3°/min and a step size of 0.04°. Figure 1 reveals differences in the phase composition and crystallinity of the investigated coatings. For the coated samples with NiCrFeC + O2, the diffractogram shows well-defined and intense peaks that can be indexed to CrNi metallic phases (JCPDS-1-071-7594), as well as evident reflections corresponding to CrO (JCPDS-1-074-6646) and NiO (JCPDS-1-080-5508), indicating that the coating contains a mixed microstructure formed by metallic and oxide components. The corresponding diffraction peaks were located at 2θ~37°, 44°, 51°, 63°, 75° and 91°. No additional diffraction peaks associated with Cr2O3 or mixed/spinel oxides were detected. As reported in the literature, Ni and Cr based oxides are known to improve tribological performance by forming stable and compact films that act as a solid lubricant and reduce contact interactions of sliding surfaces, thus limiting adhesive wear [20]. Carbon may be partially incorporated into the metallic matrix; however, based on the GIXRD results, the formation of oxide and carbide mixed phases was not detected. As observed, the appearance of Ni and Cr oxides indicates that O2 promotes oxide formation, detrimental to carbide formation. In contrast, sample NiCrFeC exhibits diffraction peaks associated only with CrNi phases, without evident oxide contributions. In this case, the main reflections were observed at approximately 44°, 51°, 75°, and 91° (2θ).

Figure 1.

Diffraction pattern of the investigated samples.

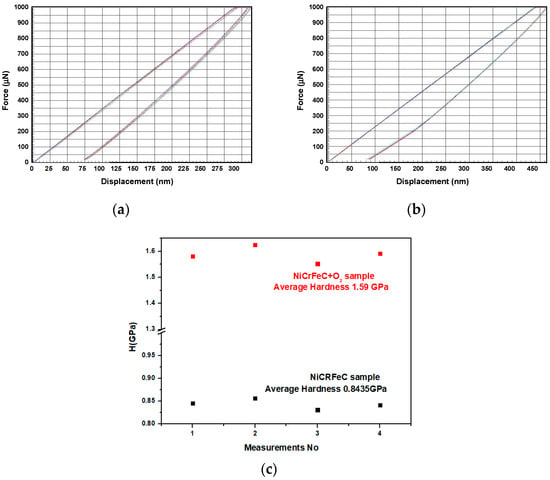

The load–unload curves obtained from nanoindentation measurements provide essential insights into the mechanical response of thin films and coated systems. The loading segment reflects the resistance of material to penetration and is strongly influenced by its elastic–plastic deformation behavior, while the unloading segment primarily captures the elastic recovery. By analyzing the slope of the initial unloading curve and the maximum penetration depth, key mechanical parameters such as hardness and reduced elastic modulus can be extracted with high precision. The load–unload graphs for the measurements for sample NiCrFeC and NiCrFeC + O2 are presented below (Figure 2a,b). The mechanical properties of the obtained coatings were evaluated using the nanoindentation technique, employing the Histrion TI 100 nano indenter with a Berkovich tip. An increase in hardness from 0.84 to 1.59 GPa can be observed for the coating with a NiCrFeC + O2 layer, thus highlighting the superior mechanical properties of the coating compared with the NiCrFeC ones (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Nanoindentation results presenting (a) the load–unload curves for sample NiCrFeC, (b) the load–unload curves for NiCrFeC + O2, and (c) the hardness for the NiCrFeC samples and NiCrFeC, containing oxygen.

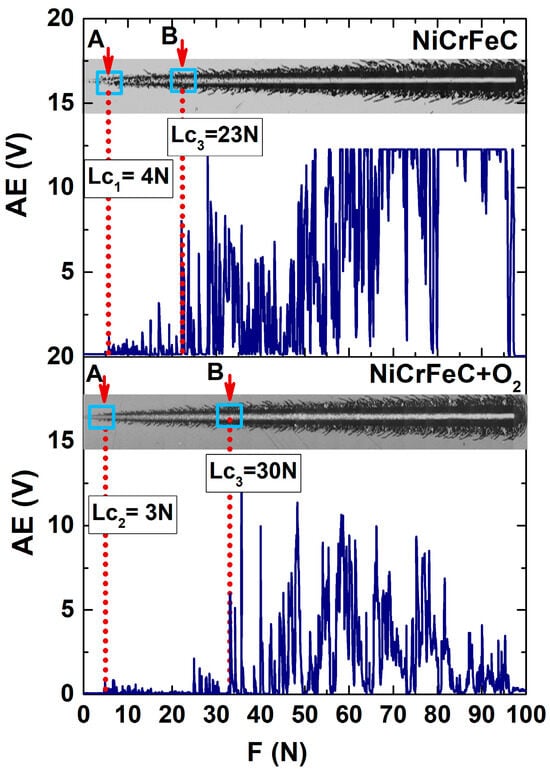

A linear-load scratch test was employed to assess the adhesion of the investigated coatings to the 304 stainless steel substrates. Following the EN1071-3:2005 standard, a progressively increasing load from 0 to 100 N was applied on a 10 mm scratch length over a duration of 1 min. The scratch tests were performed at room temperature (23 ± 1 °C) and a humidity of 52%. Multiple regions of each sample surface were evaluated, and coating failure events were detected by direct microscopic observation. The critical loads LC1, LC2, and LC3 were determined as the load at which cracks or exfoliation started to appear and, respectively, as the load at which the substrate became visible. Additionally, acoustic emission (AE) signals were recorded and evaluated for each sample, providing valuable information regarding phenomena, as presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Acoustic signal.

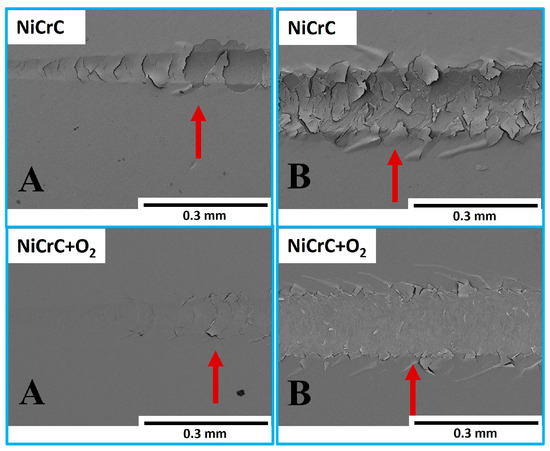

Figure 4.

SEM images of the scratch tracs on theNiCrC samples and NiCrC + O2.

For the NiCrFeC coating, the scratch track shows pronounced fragmentation at the initial stage (LC1 = 4 N), reaching a depth of 1.76 µm and a track width of 77 µm. In contrast, NiCrFeC + O2 coating shows exfoliation in the early region of the track (LC2 = 3 N), with a measured depth of 2.33 µm and an associated width of 70 µm. As the load increased, the scratch track became wider, and a sharp increase in AE amplitude indicated the propagation of coating failure. Beyond this point, exposure of the metallic substrate became evident. The higher LC3 value obtained for the NiCrFeC + O2 coating (LC3 = 30 N) demonstrates its superior adhesion to the substrate compared with the NiCrFeC coating (LC3 = 23 N).

3.2. Tribological Performance and Wear Behavior

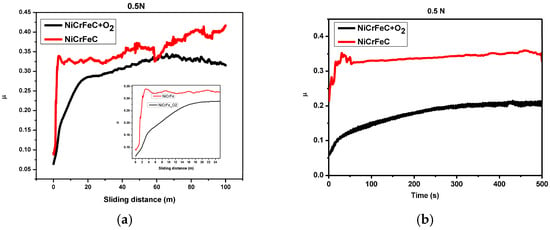

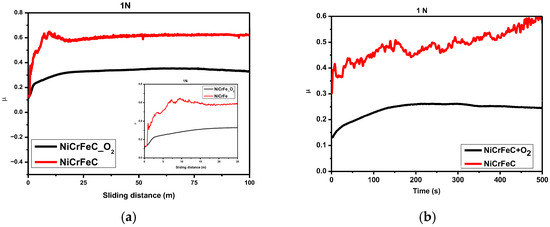

Systematic tribological measurements were performed using a ball–on–disk tribometer with a sapphire counterpart (∅ 6 mm), under normal loads of 0.5 N and 1 N, and a dry sliding distance of 10 m. During the measurements, the sliding speed was 2 cm/s, the temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and the humidity was 40%. For the NiCrFeC composite films, the steady-state friction exhibits a clear non-monotonic dependence along the composition gradient, as presented in Figure 5: µ increases from ~0.25 to a maximum of ~0.35 and then stabilizes around 0.33–0.34. In contrast, the NiCrFeC + O2 composite films show a smooth increase and stabilization of the coefficient of friction, with a maximum value of 0.20, much lower than that of the NiCrFeC layer. In the case of the NiCrFeC layer under a 1 N load (Figure 6a,b), the friction exhibits a non-uniform behavior, starting at about 0.4 and reaching 0.5, mostly due to the breaking of the coated layer. The sliding mechanism is of the rolling–sticking type. Conversely, the NiCrFeC + O2 composite film shows smooth, stable sliding at around 0.22, also significantly lower than the layer without oxygen.

Figure 5.

(a) Friction behavior in the distance of samples at 0.5 N Load, 6 mm diameter sapphire ball. (b) Friction behavior in time of samples at 0.5 N Load, 6 mm diameter sapphire ball.

Figure 6.

(a) Friction behavior in the distance of samples at 1 N Load, 6 mm diameter sapphire ball. (b) Friction behavior in time of samples at 1 N Load, 6 mm diameter sapphire ball.

In addition to these observations, the curves highlight that the initial sliding regime, up to approximately 25 m, is the most relevant for understanding the tribological response of both coatings, as explicitly shown in the inset graphs. This early stage corresponds to the transition from pure sliding to a stabilized contact, where surface adaptation, debris formation, and the onset of ball motion are dominant. At 0.5 N, within the first 25 m of sliding, the NiCrFeC coating exhibits a rapid increase in friction accompanied by pronounced fluctuations, indicating an unstable sliding regime marked by intermittent micro-instabilities and local stick–slip events. These features suggest repeated disruption of the contact, likely associated with asperity fracture and the generation of wear debris. In contrast, the NiCrFeC + O2 film shows a smoother and more gradual friction evolution in the same distance range, with significantly reduced fluctuations. This behavior indicates that oxygen incorporation promotes a more homogeneous shear interface, limiting abrupt local failures and enabling faster stabilization. Beyond ~25 m, the friction curves for both coatings tend to level off, indicating that the system has reached a steady-state regime dominated by rolling of the ball rather than pure sliding. In this regime, friction variations are minimal, and the contribution of surface adaptation processes becomes negligible compared to the established contact mechanics. At 1 N, the distinction between the two coatings in the first 25 m becomes even more pronounced. The NiCrFeC coating displays sharp friction spikes at the very beginning of sliding, consistent with early-stage coating damage or fragmentation under higher load. These abrupt increases precede the transition toward a higher steady-state friction level. Conversely, the NiCrFeC + O2 film reaches a stable friction response rapidly, already within the initial meters of sliding, and maintains a nearly constant slope throughout the critical 25 m range. This indicates that its tribological behavior is only weakly affected by the increase in normal load, pointing to enhanced mechanical integrity and load-bearing capacity. For both load conditions, an important common feature is that the NiCrFeC + O2 samples enter the steady-state regime earlier than the oxygen-free coatings, as observed in the inset graphs. The shorter transition zone up to 25 m suggests that the oxygen-modified surface stabilizes more rapidly under shear, allowing the system to quickly evolve toward a rolling-dominated motion with minimal further adaptation.

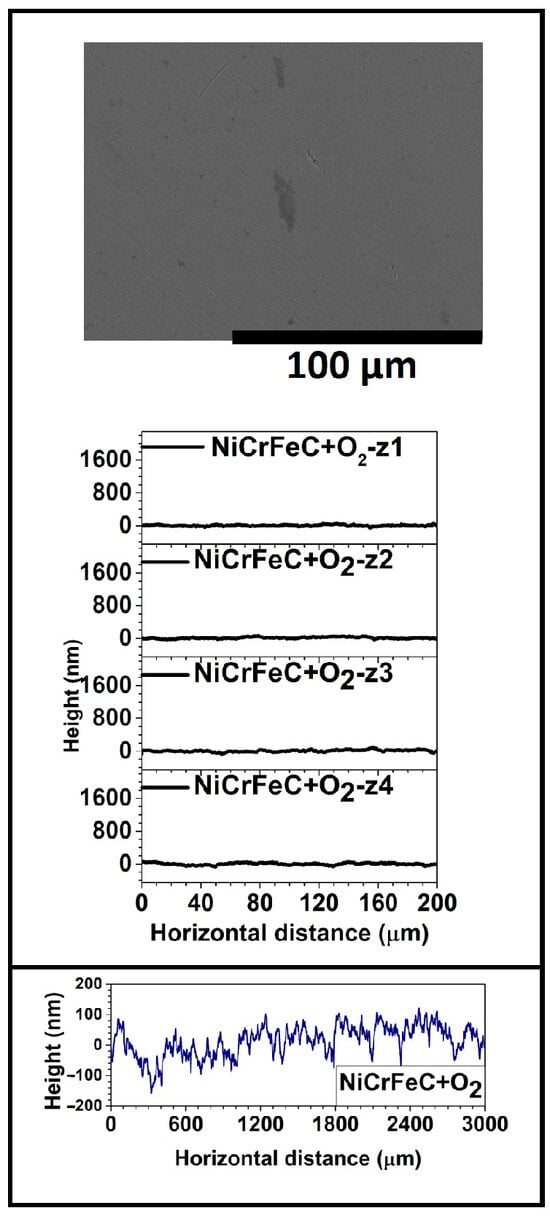

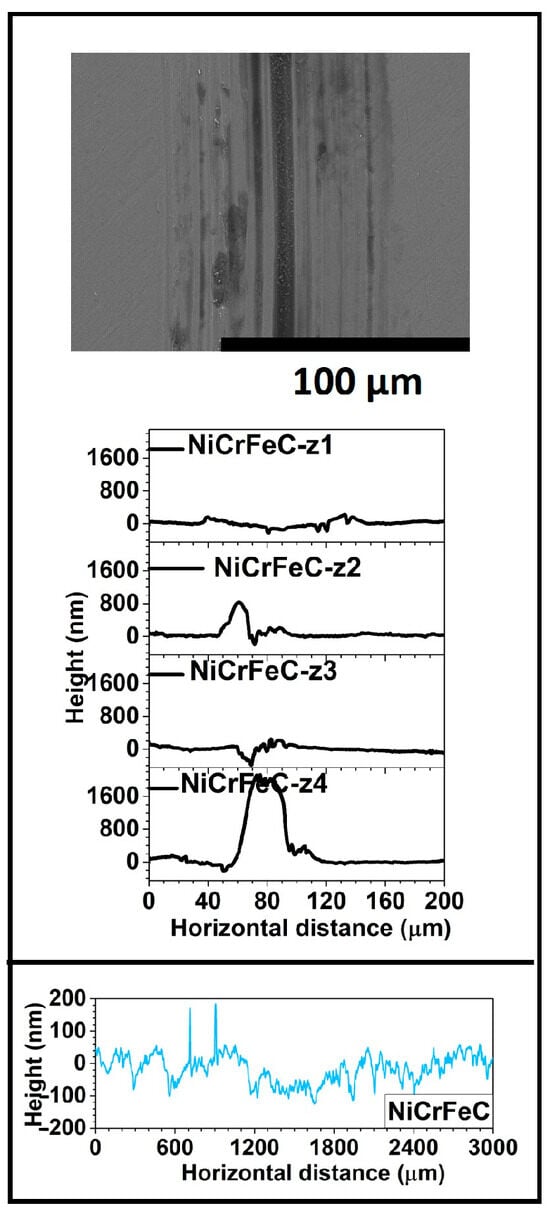

The wear track profiles shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8 exhibit lower penetration of the sapphire ball in the case of NiCrFeC + O2 compared to the NiCrFeC case. The roughness of the deposited layer was 34.17 nm (±6.47 nm) for NiCrFeC and 34.79 nm (±6.42 nm) for NiCrFeC + O2, very smooth films.

Figure 7.

SEM Image, wear track profile, and roughness of NiCrFeC + O2 film.

Figure 8.

SEM Image, wear track profile, and roughness of NiCrFeC film.

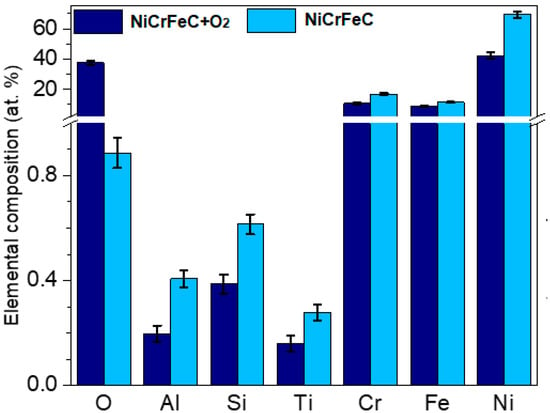

To obtain a complete picture of the processes occurring at the surface level, SEM images of the wear tracks were recorded, as seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8, along with compositional maps obtained by EDS, in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The compositional map of the deposited films of NiCrFeC, with and without oxygen.

Both the typical wear-track profiles and their corresponding images are presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively. Five-line scans, 3 mm in length and acquired over 40 s, were recorded on different regions across each area sample. For thickness evaluation, the step between the coating and the Si substrate was used to determine an average film thickness in the range of 0.6–1 µm.

For the NiCrFeC + O2 sample, only slight surface wear was observed after the tribological test at 0.5 N. The NiCrFeC + O2 sample exhibited significantly lower wear compared to the NiCrFeC sample, indicating a significantly improved tribological performance.

A significant widening of the wear track can be observed for the NiCrFeC samples compared to the NiCrFeC + O2 sample.

The conclusion of these tests is that the addition of carbon is essential, providing additional protection to the substrate, while the incorporation of oxygen leads to a further significant increase in wear resistance.

4. Conclusions

The comparative evaluation of the NiCrFeC and NiCrFeC + O2 coatings indicates that carbon incorporation contributes to the formation of a mechanically stable tribological response, while the controlled introduction of oxygen leads to a further improvement in performance associated with the presence of additional crystalline oxide phases detected by XRD. The NiCrFeC + O2 coating exhibits a pronounced increase in hardness, from 0.84 to 1.59 GPa, accompanied by improved adhesion and a significant reduction in friction and wear. From a phenomenological perspective, these changes correlate with the emergence of Cr- and Ni-containing oxide phases and with a more complex multiphase microstructure compared to the oxygen-free coating.

Beyond the quantitative improvements in mechanical and tribological metrics, the results demonstrate that the friction and wear behavior of NiCr-based coatings can be systematically adjusted through oxygen content. In particular, the NiCrFeC + O2 system shows a stable friction coefficient of approximately 0.20 together with minimal wear track degradation, defining a favorable operating regime for dry-sliding conditions. This behavior is especially relevant for applications where liquid lubrication is impractical, including elevated-temperature operation, vacuum environments, or components requiring extended service lifetimes.

Overall, the combined addition of carbon and oxygen provides a viable route for tailoring the phase composition and tribological performance of NiCr-based coatings. These findings offer practical guidance for the design of multiphase metallic coatings with optimized mechanical strength and frictional stability under demanding operating conditions.

Author Contributions

C.P.L. and C.P. conceptualization, validation, B.-G.S., A.A. and A.V. methodology and writing—review and editing and data curation, C.S. investigation, writing—review and editing, B.B., P.D., O.P., A.C.P., M.D. and L.R.C. investigations and data curation, A.S. investigations, formal analysis and data curations and C.V. investigations, formal analysis and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors greatly acknowledge the support of UEFISCDI (contract no. 13PTE, 8 January 2025 (PN-IV-P7-7.1-PTE-2024-0792)). This research was supported also by the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research, through the National Research Development and Innovation Plan 2022–2027, Core Program, Project no. PN 23 05, contract no PN11N-03-01-2023 and LAPLAS VII—contract no. 30 N/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kano, M.; Martin, J.M.; Yoshida, K.; De Barros Bouchet, M.I. Super-low friction of ta-C coating in presence of oleic acid. Friction 2014, 2, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, H.; Rodríguez Ripoll, M.; Prakash, B. Tribological behavior of self-lubricating materials at high temperatures. Int. Mater. Rev. 2018, 63, 309–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Menezes, P.L. Self-lubricating materials for extreme condition applications. Materials 2021, 14, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H. Ionic liquid lubricants: Basics and applications. Tribol. Trans. 2017, 60, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Chi, M.; Meyer, H.M., III; Blau, P.J.; Dai, S.; Luo, H. Nanostructure and composition of tribo-boundary films formed in ionic liquid lubrication. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 43, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.; Tung, S.C. Overview of automotive engine friction and reduction trends—Effects of surface, material, and lubricant-additive technologies. Friction 2016, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Deng, Q.Y.; Liu, B.; Wu, B.J.; Jing, F.J.; Leng, Y.X.; Huang, N. Wear and corrosion properties of diamond-like carbon (DLC) coating on stainless steel, CoCrMo and Ti6Al4V substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 273, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, H.; Wijanarko, W.; Cruz, S.; Evaristo, M.; Espallargas, N. Triboelectrochemical friction control of W- and Ag-doped DLC coatings in water–glycol with ionic liquids as lubricant additives. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 3573–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.H.; Aune, R.E.; Espallargas, N. Tribocorrosion studies of metallic biomaterials: The effect of plasma nitriding and DLC surface modifications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 63, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härtwig, F.; Lorenz, L.; Makowski, S.; Krause, M.; Habenicht, C.; Lasagni, A.F. Low-friction of Ta-C coatings paired with brass and other materials under vacuum and atmospheric conditions. Materials 2022, 15, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajita, S.; Righi, M.C. A fundamental mechanism for carbon-film lubricity identified by means of ab initio molecular dynamics. Carbon 2016, 103, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ding, S.; Luo, J. Macroscale superlubricity of Si-doped diamond-like carbon film enabled by graphene oxide as additives. Carbon 2021, 176, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Kato, T.; Yang, X.-A.; Wu, S.; Wang, R.; Nosaka, M.; Luo, J. Evolution of tribo-induced interfacial nanostructures governing superlubricity in a-C:H and a-C:H:Si films. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdemir, A.; Eryilmaz, O. Achieving superlubricity in DLC films by controlling bulk, surface, and tribochemistry. Friction 2014, 2, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J. Superlubricity of carbon nanostructures. Carbon 2019, 158, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Liu, X.; Qin, L.; Lu, Z. Ni20/PTFE Composite Coating Material and the Synergistic Friction Reduction and Wear Resistance Mechanism Under Multiple Working Conditions. Coatings 2025, 15, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.Y. High-Temperature Corrosion and Materials Applications; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yi, S.; Li, J.; Ding, S. Thermal and force simulation modelling of graphene oxide nanosheets as cutting fluid additives during Ti-6Al-4V drilling process. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 210, 109608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, I. Recent aspects concerning DC reactive magnetron sputtering of thin films: A review. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000, 127, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Gonuguntla, S.; Sk, S.; Iqbal, M.S.; Dada, A.O.; Pal, U.; Ahmadipour, M. Sputtering thin films: Materials, applications, challenges and future directions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 330, 103203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.