Abstract

In age-friendly furniture design, the visual characteristics of material surfaces play a crucial role in shaping the usage experience and preferences of elderly users. In response to the application requirements of decorative materials for furniture surfaces, this study focuses on polypropylene (PP) films, with the objective of investigating the visual perceptual preferences of elderly users concerning the surface color and glossiness attributes of these films. An eye-tracking experiment was initially conducted to identify color preferences among elderly participants, utilizing indicators including first fixation duration, total fixation duration, and total fixation count. Subsequently, a questionnaire survey was administered to assess user satisfaction with PP films featuring different glossiness levels—high-glossiness, semi-glossiness, and matte—and explored whether glossiness significantly influences color preference. The experimental results revealed the following: (1) red hues exhibited stronger initial visual attraction, while colors with low saturation and medium-to-high lightness sustained longer visual engagement; (2) the matte finishes received significantly higher satisfaction ratings than both semi-glossiness and high-glossiness finishes, with this preference remaining consistent across different color conditions; (3) glossiness does not exert a significant influence on color preference. The findings of this study provide consumer-oriented insights for the design of PP films that better accommodate the preferences of elderly users, while also offering guidance for the application and optimization of green and safe furniture materials.

1. Introduction

In recent years, China has witnessed a pronounced acceleration in population aging. Statistical data reveal that by the end of 2023, the population aged 60 and above in China had reached approximately 297 million, accounting for 21.1% of the total population, indicating that the country has officially entered a moderately aged society [1]. The demographic shift has profoundly influenced China’s consumer market, spurring the rapid growth of a “silver economy”. In particular, the home furnishing sector, which is closely related to the daily lives of older adults, faces increasing demands for age-adapted innovation [2]. With increasing age, the sensory functions in older adults undergo systematic decline, with the visual system being notably affected. Common issues include reduced visual acuity, presbyopia, impaired color discrimination, decreased adaptability to changing light conditions, and constriction of the visual field [3,4]. These physiological changes often interact with psychological shifts, frequently manifesting as a heightened demand for safety, comfort, and environmental familiarity [5]. The physiological and psychological transformations that occur among elderly individuals underscore the imperative for designers and manufacturers to accord special emphasis to sensory experience and emotional well-being. This entails carrying out targeted studies into sensory perception, with a focus on materials that are conducive to age-friendly environment.

In panel furniture manufacturing, solid wood, blockboard, plywood, particleboard, and medium-density fiber-board (MDF) are commonly used as substrates. These materials typically require surface decoration or finishing prior to use, with typical surface finishing materials including lacquer coatings, double-faced decorative paper, natural wood veneer, melamine-impregnated surfaces, PVC films, PET films, and acrylic finishes. However, these established decorative technologies and surface materials present several limitations in contemporary consumer contexts. These limitations include the emission of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from extensive organic solvents use during production, formaldehyde release resulting from surface abrasion during long-term use, and susceptibility to humidity and temperature, which can lead to warping and cracking. These issues not only compromise indoor air safety but also negatively affect users’ visual experience [6]. Against this background, surface finishing materials that combine environmental friendliness with strong processing potential have gradually attracted increasing attention.

Polypropylene (PP) films are a class of polymeric thin-film material primarily composed of polypropylene and manufactured through extrusion, stretching, and orientation processes, PP films demonstrate superior environmental friendliness and safety compared with conventional decorative films such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Additionally, PP films exhibit excellent mechanical properties, including high tensile strength, impact resistance, and folding endurance [7]. Furthermore, the surface glossiness and color of PP films can be precisely modulated through modification technologies, presenting significant potential for research in the field of visual perception. At the level of furniture surface applications, the suitability of PP films differs significantly among various types of furniture [8]. Relatively speaking, PP films are more suitable for furniture components used in relatively stable environments, where demands for structural load-bearing capacity and resistance to surface impact are low, and where visual experience predominates. Typical applications include desks, cabinet side panels, and the decorative surfaces of storage furniture. Such furniture components are generally subjected to constant indoor lighting and stable temperature–humidity conditions, with surface interactions mainly involving light friction and routine cleaning. Under these circumstances, the advantages of PP films in color performance and glossiness control are more readily perceived and effectively utilized. As essential furniture in daily living and working environments, the desk is characterized by its functional nature and high utilization frequency. Activities performed on desks typically involve intensive visual and manual tasks. Therefore, the texture of the desktop surface, the characteristics of light reflection, and the color environment directly exert an influence on users’ visual comfort and psychological state.

1.1. Visual Sensory Experience of Consumer Products and Materials

As consumer demand evolves, users are increasingly emphasizing not only the structural performance and durability of furniture materials, but also the sensory comfort they provide, particularly in visual, tactile, and olfactory dimensions. This shift has catalyzed the emergence of sensory-centered design approaches in the furniture industry. As the dominant channel of human perception, vision plays a core role in the cognitive and decision-making processes associated with consumer products. Jiang et al. [9] investigated whether adolescents’ color preferences influence their furniture selection, confirming that such preferences do indeed impact furniture selection, albeit with varying degrees of influence varies across furniture categories. Cui et al. [10] combined user surveys with eye-tracking technology to systematically evaluate consumer preferences and visual appeal in contemporary Chinese-style furniture. Kim et al. [11] employed eye-tracking and virtual reality to explore how spatial and design elements in immersive retail environments shape visual attention and emotional arousal. Barbierato et al. [12] applied quantitative eye-tracking metrics to identify visually salient wine bottle label designs and examined the correlation between visual attention and consumer preference. Ji et al. [13] focusing on the color and aesthetic design of leisure chairs, introduced a multimodal research methodology. This approach leveraged eye-tracking, electrocardiogram (ECG), and electroencephalogram (EEG) data to investigate factors that significantly influence consumers’ subjective preference evaluations and physiological responses. Subsequently, they proposed an evaluation model for the aesthetic association mechanism of leisure chairs. In the field of visual perception, research primarily employs subjective evaluation scales with objective methodologies such as eye-tracking. While subjective evaluations capture consumer preferences and psychological responses, techniques like eye-tracking provide mechanistic insights into visual processing. Therefore, it is essential to explore elderly consumers’ visual perception and preferences regarding surface decorations, such as PP films, by employing a combined approach of eye-tracking technology and subjective evaluation scales.

Visual perception constitutes an active, cognitively engaged decoding process rather than passive reception, wherein the brain infers the material, shape, and spatial relationships from incoming light information [14]. Within this complex perceptual mechanism, the color and glossiness emerge as two fundamental visual attributes governing material appearance. As a potent psychological cue, color directly evokes emotional responses. Variations in saturation, brightness, and hue combinations can create a tranquil, warm, or vibrant spatial atmosphere, significantly influencing emotional states and the quality of life. Glossiness, conversely, governs light–material interactions, affecting both texture perception and color interpretation through intricate cross-attribute interactions. Cho et al. [15] combined questionnaires with eye-tracking to examine how spatial application of identical color elicits various emotional reactions, quantifying the impact of color on emotions and preferences. Jung et al. [16] employed Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and EEG measurements to correlate bedroom color preferences with depression in elderly populations, revealing that psychologically healthy elderly individuals responded positively to cool-toned color schemes, while depressed elderly individuals preferred cool-warm contrasts. Tuszynska-Bogucka et al. [17] used eye-tracking to measure measured respondents’ reactions to architectural visualizations, revealing that different spatial and color arrangements in the visualizations evoked distinct emotional responses. Tamura et al. [18] explored the relationship between glossiness perception and pupillary responses through glossiness rating experiments, finding that high-glossiness object images leads to pupil constriction through illusory brightness, establishing physiological correlates of appearance perception. Bertheaux et al. [19] generated 16 material effects by varying the metallic quality and smoothness of mugs, finding that both attributes positively influenced arousal and valence through enhanced specular reflection. Honson et al. [20] conducted a systematic manipulation of surface geometry, roughness, and glossiness parameters to investigate their impact on visual perception by controlling these physical factors. Their findings demonstrated that as the roughness of mirror-like reflections increased, observers perceived significantly reduced color saturation alongside enhanced brightness perception. Certain glossiness characteristics were shown to induce measurable color deviations, confirming cross-attribute interactions between surface texture and chromatic perception. In a complementary study, Morimoto et al. [21] employed asymmetric matching under varied illumination conditions to investigate color and glossiness constancy. Their results revealed coupled effects of color and specular reflection parameters on material equivalence judgments.

From a materials science standpoint, the visual experience of consumer products is shaped not only by their intended color schemes and geometric forms but also—crucially—by the physical and optical behavior of their surface properties. Elements such as microstructural composition, texture granularity, reflectivity, and surface homogeneity act as visual stimuli that modulate the distribution and interaction of light, thereby influencing perceived chromatic stability, luminance gradients, and overall surface tactility. A growing body of empirical evidence suggests that even when chromatic parameters remain constant, differences in gloss, surface roughness, and reflectance among materials can elicit markedly distinct perceptual and emotional responses from users, particularly in terms of visual prominence, comfort, and affective resonance [22]. These findings challenge the notion of material surfaces as passive aesthetic substrates; rather, they underscore their active role in shaping perceptual interpretation through complex light–surface interactions. Fleming [23], in a seminal synthesis of psychophysical experiments and computational modeling, articulated that visual cues such as glossiness, texture, and reflectivity are integral to the brain’s material inference process—proposing that the perception of material appearance is a cognitively constructed phenomenon. Levoy et al. [24] employed synthetic image modeling to explore how variations in reflective parameters influence gloss perception, culminating in a perceptually grounded reflection model. Marcos et al. [25] examined the perceptual stability of gloss and color under varying illumination conditions, highlighting the dynamic interplay between lighting context and surface interpretation. Chadwick et al. [26] provided an interdisciplinary synthesis from visual psychology and neuroscience, identifying core visual cues that mediate gloss perception and their implications for subjective material evaluation. Motoyoshi et al. [27] utilized statistical image analysis to demonstrate how the human visual system deciphers material attributes like gloss and roughness from image-derived data, further reinforcing the active, inferential nature of surface perception.

In the domain of materials and consumer product research, color has persistently stood out as a critical determinant in shaping both aesthetic appraisal and overall user experience. Historically, investigations into material coloration were largely grounded in intuitive judgments and subjective accounts, often centered around loosely defined notions such as “visual appeal” or “appropriateness”. This reliance on qualitative descriptors rendered cross-study comparison and replication challenging, if not altogether impractical [28]. However, advancements in colorimetry and perceptual psychology have progressively underscored the necessity of adopting parameterized frameworks to decode how discrete color dimensions impact perceptual and affective responses. This methodological evolution has repositioned color from a mere stylistic artifact to a quantifiable research construct—capable of independent manipulation, systematic comparison, and empirical validation. In this vein, color is now typically analyzed along three perceptually salient axes: hue, saturation, and value (or brightness), which together facilitate controlled experimental designs and enable nuanced analysis of user preferences. Wilms et al. [29] through isolated manipulation of these three dimensions, demonstrated that emotional responses to color are not solely dictated by hue, as commonly assumed, but rather emerge from the dynamic interplay among all three components. This multidimensional perspective challenges reductive models of color-emotion association. Song et al. [30] employed a rigorously controlled design to examine evaluative differences between art and non-art students, revealing distinct group-based divergences in emotional color perception. Schloss et al. [31], by eliciting aesthetic ratings across a vast array of color pairings, concluded that preference judgments were predominantly influenced by hue and value. Camgöz et al. [32] took a contextual approach, presenting color patches against variable background tones to investigate how foreground–background configurations modulate color preference; their results emphasized the preference for combinations featuring high saturation and brightness. Ou et al. [33] applied the semantic differential method to map color stimuli onto emotional dimensions, uncovering statistically robust linkages between specific color attributes and emotional valence.

PP films, due to their excellent environmental friendliness, wear resistance, and molding processing capabilities, have found widespread applications in packaging, medical devices, food containers, and select architectural applications. Nevertheless, the application of PP films in furniture surface decoration remains at an exploratory phase, and has not yet formed a large-scale industrial trend. PP films exhibit significant advantages in color performance and glossiness control, offering new possibilities for enhancing visual comfort through systematic adjustment of surface optical properties. Introducing PP films into desk design for elderly users not only supports the green transformation of furniture material systems but also caters to the visual perception, psychological health, and quality of life demands of the elderly population. Consequently, systematically studying the impact of PP film color and glossiness on the visual perception of elderly users is of great significance for the design of age-friendly furniture.

1.2. Current Research

Existing studies on furniture finishing materials indicate that physical properties largely determine the users’ visual experience, thereby influencing their aesthetic judgments and preferences. However, previous research predominantly focused on younger consumer groups, with insufficient attention given to the rapidly growing elderly population. This study specifically targets elderly users, selecting desks—as frequently utilized furniture—to examine how the surface color and glossiness of PP films affect visual perception preferences. This study is divided into two parts and addresses three key research questions: (1) the relationship between elderly users’ visual preferences and different color attributes; (2) the relationship between elderly users’ visual preferences and glossiness; and (3) whether glossiness moderates the effect of color on elderly users’ visual preferences. The aim of this study is to identify PP films suitable for elderly users and to enhance their visual experience, while providing references for material selection and product optimization in the furniture industry.

2. Experiment 1: Color Experiment and Analysis

2.1. Methodology

This experiment employed an eye-tracking methodology to examine how elderly participants allocate visual attention during preference-oriented visual search tasks under varying conditions of hue, saturation, and value. By analyzing eye-tracking metrics including first fixation duration, total fixation duration, and fixation count, differences in elderly participants’ visual responses to various color stimuli were characterized from three perspectives: initial attention, sustained attention, and repeated attention. A within-subject experimental design was adopted, and repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) combined with post hoc multiple comparisons was conducted to statistically examine differences across levels of each color factor. Through this approach, elderly users’ preference differences toward various color attributes were identified at the level of visual attention.

2.1.1. Stimulus Materials

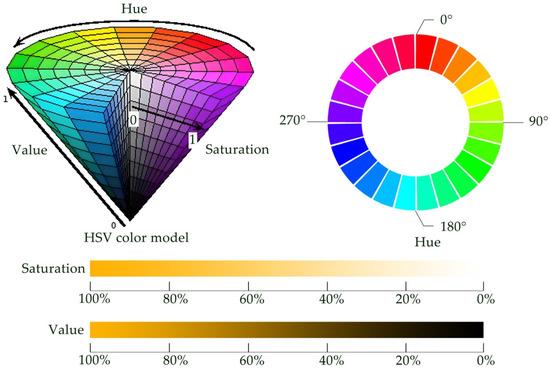

HSV represents a perceptually oriented color space consisting of three dimensions: hue, saturation, and value, organized in a conical model structure, as shown in Figure 1. The hue (H) ranges from 0° to 360°, while saturation (S) and value (V) each range from 0% to 100%. Compared to the RGB color model, HSV exhibits lower inter-dimensional correlation, offering closer alignment with human subjective color perception. Additionally, the HSV framework facilitates designers’ intuitive understanding of how parametric variations influence color appearance. Since RGB color representation remains standard in industrial design and visual stimuli were presented displayed on a computer screen, the appropriate hue, saturation, and value combinations were first defined within the HSV color model. The corresponding RGB values were subsequently derived through color space conversion. This workflow maintains consistency in sample coloration while preserving designers’ perceptual engagement with color variation.

Figure 1.

The HSV color model and Its Hue, Saturation, and Value color element space.

The hue was systematically divided into six intervals with the following value ranges: 0–60° (red), 60–120° (yellow), 120–180° (green), 180–240° (cyan), 240–300° (blue), and 300–360° (purple). Each interval represents a continuous spectrum rather than discrete values. To establish precise design specifications, the midpoint of each interval was selected as the representative value. For example, 30° was selected to represent the red hue range (0–60°) for desk color assignment. Similarly, the saturation and value were categorized into five intervals corresponding to high, high–medium, medium, low–medium, and low dimensions of saturation and value.

Following consultation with design experts and analysis of market sales data from both online and physical stores, consumer preference for warm-colored furniture was confirmed. To better reflect this tendency, the hue range was adjusted to include 0° to enrich the sample colors. The final selection of color factors is summarized in Table 1. For stimulus preparation, the most common and simplified desk design was chosen as the base model for color application. Initial generation produced 175 samples through systematic parameter combinations. These underwent manual screening to eliminate visually similar or perceptually indistinguishable variants. The final 50 experimental samples retained are presented in Figure 2, after screening, the retained stimuli still covered all factor levels.

Table 1.

Selection levels of HSV color factors.

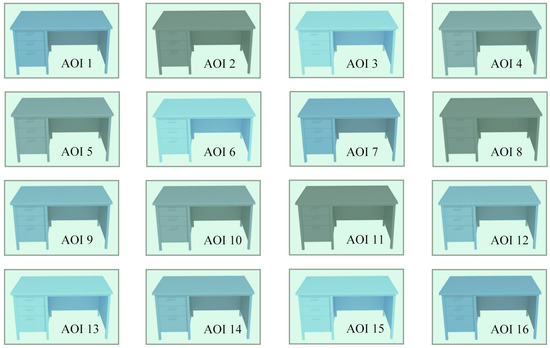

Figure 2.

Eye-Tracking experiment samples.

During the stimulus design stage, this study adopted a factor-controlled experimental strategy. A total of 13 stimulus images were developed, including 3 images for examining differences across hue levels, 5 images for examining differences across saturation levels, and 5 images for examining differences across value levels. Within each category of stimulus images, multiple images used to test the same color factor differed in the specific values of the non-target color factors. Within each individual stimulus image, the non-target factors were held constant, and only the target factor was varied. By repeatedly measuring the effects of the same color factor under different control conditions, this approach effectively reduced the influence of chance effects associated with specific color combinations.

Each stimulus image consisted of 16 desks, corresponding to 16 areas of interest (AOIs). The positions of the desks were randomly arranged, and the AOIs were generally consistent in area and shape. To enable repeated measurements of the same color factor under different control conditions, the same desk was presented multiple times across the experiment. As illustrated in Figure 3, taking the measurement of saturation levels as an example, each stimulus image contained desks with five different saturation levels, with each desk repeatedly presented three to four times within the same stimulus image.

Figure 3.

An example of AOI segmentation for a saturation measurement stimulus image.

2.1.2. Participants

According to the classification standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO), elderly population is categorized into three categories: young elderly (aged 60 to 74), elderly (aged 75 to 89), and long-lived elderly (aged 90 and above). This experiment primarily targeted the young elderly group and involved 30 participants, including 15 males and 15 females, all with normal or corrected vision and without color vision deficiencies. Before the experiment, participants were required to review and sign a written informed consent form authorizing the use of their experimental data. Only those providing explicit consent proceeded to the experimental phase.

2.1.3. Experimental Equipment

The eye-tracking experiment was conducted using the Tobii 1750 eye tracker (Tobii Technology, Stockholm, Sweden). Participant data were recorded and processed through the ErgoLAB eye-tracking analysis platform (Jinfa Technology, Shanghai, China). The host computer operated on the Windows 11 operating system and was equipped with a 1920 × 1080 LCD monitor (Lenovo, Nanjing, China) with a refresh rate of 60 Hz. Prior to the experiment, the brightness and display parameters of the monitor were uniformly calibrated and remained constant throughout the experimental procedure.

2.1.4. Experimental Procedure

(1) The experimental materials were prepared and preloaded into the eye-tracking system. (2) Participants underwent color vision screening using standard tests to exclude color blindness or color deficiency. Participants with presbyopia wear reading glasses for correction. (3) Before the experiment began, the experimenter explained the task requirements to the participants. During the presentation of the stimulus images, participants were instructed to search for desks they preferred based on their personal preferences. When a desk was perceived as particularly appealing, participants were encouraged to extend their fixation duration and to visually scan among multiple preferred desks. (4) Participants were seated approximately 65 cm in front of the display screen. After adjusting to a comfortable sitting posture, eye-tracking calibration was performed. During calibration, five red dots sequentially appeared on the screen, and participants were instructed to follow the moving dots with their eyes. The calibration quality was presented in the form of a progress bar transitioning from red to green; when the indicator turned green, the calibration was considered satisfactory and the formal experiment commenced. (5) The 13 stimulus images prepared for the experiment were presented in a randomized order, with an exposure duration of 8000 ms. After each image, a 3000 ms blank image is inserted to relax the eyes and eliminate the influence of fixation order on the experiment. The experiment concluded after all 13 images had been presented sequentially.

2.2. Results and Analysis

Fixation identification was performed using the built-in algorithms of the eye-tracking analysis software, with the minimum fixation duration threshold set to 100 ms to exclude brief saccades or noise-related data. During data cleaning, segments with lost eye-tracking signals were removed. If the proportion of valid fixation data for a participant under a given stimulus condition fell below the system’s acceptable range, the data for that condition were excluded from subsequent statistical analyses. The final analysis adopted the participant as the statistical unit. Specifically, eye-tracking metrics for each participant under the same stimulus condition were first aggregated by calculating mean values, after which repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted based on a within-subject design. This approach helped to avoid the disproportionate influence of single stimuli or individual AOIs on the overall results. For each color attribute, repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare first fixation duration, total fixation duration, and fixation count across different levels. When the assumption of sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom. When significant main effects were observed, Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted to clarify the differences among levels of each color factor.

- (1)

- First fixation duration analysis

First fixation duration refers to the time elapsed from stimulus onset until a participant’s gaze first lands on a target area of interest (AOI). This metric reflects the stimulus’s ability to automatically attract visual attention during the early stage of visual presentation. A shorter first fixation duration indicates that the stimulus is more likely to capture visual attention at the initial stage. Accordingly, first fixation duration serves as an important indicator of initial visual attention in elderly participants and was used to examine the effects of the three color factors attributes—hue, saturation, and value—on elderly participants’ initial visual attention.

The results of the repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) are presented in Table 2, indicating that hue, saturation, and value all had significant effects on the first fixation duration of elderly participants (p < 0.05). Subsequently, post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted for the different levels of each factor, and the results are presented in Table 3. The findings indicate that red hues (H0, H30) show significant differences compared with yellow (H90), green (H150), blue (H270), and purple (H330) hues. Additionally, the yellow hue (H90) showed significant differences compared with the green hue (H150), cyan hue (H210) and blue hue(H270). While the cyan hue (H210) differed significantly from the green hue (H150), blue hue (H270), and the purple hue (H330). Further examination of the mean distribution trends of first fixation duration across hue levels reveals that different hues exhibited a progressive increase from shorter to longer values during the initial attention stage. The relative order was: H30 < H210 ≈ H0 < H90 < H330 ≈ H270 < H150. This indicates that first fixation durations were relatively shorter under reddish and cyan hue conditions, whereas green and blue hues were associated with relatively longer first fixation durations. The above results indicate that, during the early stage of visual presentation, warmer hues demonstrate a clear advantage in attracting initial visual attention among elderly participants, whereas cooler hues, particularly green and blue, are relatively less effective in facilitating the formation of initial visual attention.

Table 2.

Results of repeated-measures ANOVA for first fixation duration.

Table 3.

Post hoc multiple comparisons of first fixation duration at different levels of HSV color factors.

For saturation, significant differences were observed between high saturation (S90) and low (S10), low–medium (S30), medium (S50), and medium–high (S70) saturation levels. In addition, medium saturation (S50) differed significantly from low saturation (S10) and low–medium saturation (S30). Examination of the mean trends across saturation levels indicates that first fixation duration generally followed the pattern S50 < S30 ≈ S70 < S10 < S90.These results suggest that, during the initial stage of visual presentation, moderate saturation is more conducive to the formation of initial visual attention among elderly participants, whereas excessively high saturation is clearly detrimental to the rapid establishment of initial attention.

Regarding value, medium value (V50) showed significant differences compared with the other four value levels, whereas no significant differences were observed among the remaining value levels. Examination of the mean distribution trends indicates that first fixation duration at V50 was markedly lower than at V10, V30, V70, and V90. These results demonstrate that, during the early stage of visual presentation, medium value exhibits a clear advantage in attracting initial visual attention among elderly participants, while very low and very high value conditions show relatively similar performance at the initial attention stage.

- (2)

- Analysis of total fixation duration and fixation count

Total fixation duration and fixation count respectively reflect the cumulative duration of gaze and the frequency of fixations within a target area of interest (AOI). Under preference-oriented visual search tasks, these two metrics can be used to characterize the degree of visual attention allocated to different stimuli driven by participants’ subjective preferences. When a particular color level exhibits higher values on both metrics, it indicates that the stimulus not only attracts repeated visual attention but also sustains longer fixation durations. In the context of this study, such performance can be regarded as an important indicator of a higher preference level.

First, hue, saturation, and value were treated as within-subject independent variables, and repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted separately for total fixation duration and fixation count, with the results shown in Table 4. The results indicate that all three color factors exhibited significant differences on both eye-tracking metrics (p < 0.05). Accordingly, post hoc multiple comparisons were further performed to analyze the differences among the various levels of each factor, with the results presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Repeated-measures ANOVA results for total fixation duration and fixation count.

Table 5.

Post hoc multiple comparisons of total fixation duration at different levels of HSV color factors.

Table 6.

Post hoc multiple comparisons of fixation count at different levels of HSV color factors.

In terms of total fixation duration, The red hues (H0 and H30) showed significant differences compared with all other hues, and the cyan hue (H210) differed significantly from the blue hue (H270) and the purple hue (H330). Examination of the distribution of the estimated marginal means indicates the following order: H30 > H0 > H90 ≈ H210 > H150 > H270 ≈ H330. These results suggest that warmer hues are more effective in sustaining continuous visual attention, whereas cooler hues exhibit relatively weaker attractiveness during the sustained attention stage.

High saturation (S90) showed significant differences compared with the other four saturation levels. In addition, low saturation (S10) differed significantly from medium saturation (S50) and medium–high saturation (S70), while low–medium saturation (S30) also exhibited a significant difference from medium–high saturation (S70). Examination of the distribution of the estimated marginal means indicates the following order: S10 > S30 > S50 ≈ S70 > S90. These results suggest that the attractiveness of stimuli to elderly participants decreases progressively with increasing saturation. Excessively high saturation may impose a visual burden on elderly viewers, thereby reducing their willingness to maintain sustained attention, whereas relatively soft saturation levels are more conducive to preserving stable visual attention.

Significant differences in total fixation duration were identified between low value (V10) and medium (V50), medium–high (V70), and high (V90) value levels. Medium–low value (V30) exhibited a similar differentiation pattern to low value (V10). The estimated marginal means exhibited the following order: V50 ≈ V90 ≈ V70 > V30 > V10. Medium, medium–high, and high value levels demonstrated stronger visual attraction for elderly participants, whereas low and medium–low value levels showed relatively weaker attractiveness.

The post hoc multiple comparison results for fixation count showed a high degree of consistency with those for total fixation duration. Although differences were observed in a few pairwise comparisons, the overall distribution pattern of the estimated marginal means did not exhibit substantial changes.

3. Experiment 2: Glossiness Experiment and Analysis

3.1. Method

Building upon Experiment 1, this experiment selected representative colors that elicited relatively high and low levels of visual attention in the preliminary study and introduced physical PP film samples with different glossiness levels to construct combined color–glossiness conditions. Through subjective satisfaction evaluations conducted under controlled lighting conditions, this experiment systematically examined elderly participants’ visual preference differences toward surfaces with varying glossiness, and further analyzed whether glossiness influences existing color preferences.

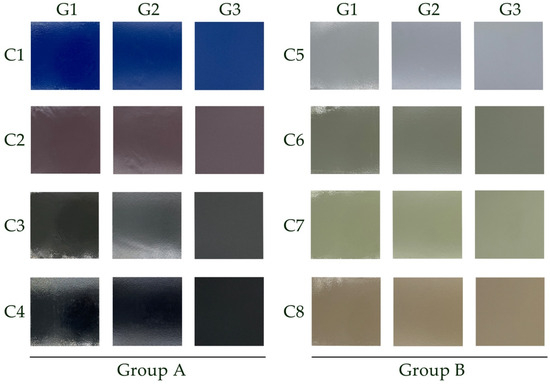

3.1.1. Stimulus Materials

Under preference-oriented visual search conditions, increased visual attention is generally accompanied by a higher level of preference. Accordingly, in this study, the high-attention colors consistently indicated by multiple eye-tracking metrics in Experiment 1 were regarded as relatively preferred colors among elderly participants, whereas low-attention colors were considered less preferred. For the PP film glossiness experiment, eight representative colors were selected from the 50 colors tested in Experiment 1 and were further divided into two groups: Group A (C1–C4) represented colors eliciting lower visual attention, while Group B (C5–C8) comprised colors associated with high visual attention. Each color was assigned three different glossiness levels, with glossiness values of 85 GU, 50 GU, and 18 GU—high-glossiness, semi-glossiness, and matte, coded as G1, G2, and G3, respectively. Each film was applied to a 10 × 10 cm sample panel with a thickness of 3 mm. Sample coding followed a color-glossiness combination system (e.g., C1G1 denotes color C1 with high-glossiness finish). As illustrated in Figure 4, the full stimulus set comprised 24 samples representing all color-glossiness combinations.

Figure 4.

Twenty-four laminated samples.

3.1.2. Experimental Environment

This experiment was conducted in an indoor environment under uniform artificial lighting conditions. During the experiment, overhead LED lighting was used, with an illuminance of 400 lx and a correlated color temperature of approximately 4000 K. The lighting conditions were kept constant throughout the experiment to avoid potential interference from illumination variations on the perception of surface glossiness.

3.1.3. Experimental Procedure

(1) The 30 elderly participants first underwent standardized color vision screening to exclude color blindness or deficiency. Presbyopic individuals used appropriate optical correction. Notably, this participants cohort differed from that employed in Experiment 1. (2) Participants were seated at standardized viewing positions, and the experimenter randomly presented the 24 samples to the participants one by one. Each sample was displayed for approximately 10,000 ms to allow comprehensive visual assessment. (3) After completing the observations, participants filled out a satisfaction questionnaire to evaluate each sample. To accommodate elderly cognitive characteristics, a five-point Likert scale (−2 to 2) was implemented to quantify subjective preferences, providing systematic data on glossiness perception across different color conditions.

3.2. Results of the Glossiness Experiment

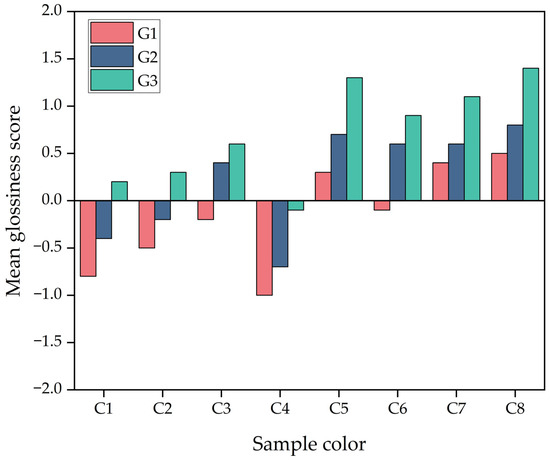

Following data collection, response frequencies for each rating level across different samples were systematically recorded. The final mean satisfaction scores for each sample are shown in Figure 5. A score of −2 represents very dissatisfied, −1 represents dissatisfied, 0 represents neutral, 1 represents satisfied, and 2 represents very satisfied. Higher scores indicate a greater level of preference, while lower scores indicate reduced acceptance.

Figure 5.

Average sample evaluation scores.

As shown in Figure 5, high-glossiness samples in Group A (C1–C4) consistently received negative mean satisfaction scores. With the exception of C3, the semi-glossiness samples also yielded negative mean scores, while all matte samples—excluding C4—achieved positive scores. For each color variant, the satisfaction hierarchy remained consistent: high-glossiness < semi-glossiness < matte. These results indicate that elderly participants showed the lowest satisfaction with high-glossiness samples and the highest satisfaction with matte samples.

In Group B (C5–C8), except for C6G1, the mean scores of all samples were positive. Consistently, the satisfaction hierarchy for each color maintained the identical pattern: high-glossiness < semi-glossiness < matte.

To examine the main effects and interaction effect of color and glossiness, ratings for multiple samples within the same color group were first averaged within each participant. Subsequently, a two-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, with color group (Group A: low-attention colors/Group B: high-attention colors) and glossiness (high-glossiness, semi-glossiness, and matte) treated as within-subject factors. The results of Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that all within-subject factors and their interaction satisfied the sphericity assumption (p > 0.05); therefore, uncorrected degrees of freedom were used for subsequent analyses.

The results of the repeated-measures ANOVA are presented in Table 7. The main effect of color group was significant, F (1, 29) = 47.618, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.621. The main effect of glossiness was also significant, F (2, 58) = 24.033, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.453. In contrast, the interaction effect between color group and glossiness was not significant, F (2, 58) = 0.010, p = 0.990. These results indicate that both color group and glossiness exert significant effects on elderly participants’ satisfaction ratings, while their effects are relatively independent, with no significant interaction observed between the two factors.

Table 7.

Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA results for the effects of color and glossiness on satisfaction ratings.

Further examination of the estimated marginal means (as shown in Table 8) reveals a clear increasing trend in satisfaction ratings across different levels of glossiness. Specifically, samples with high glossiness received the lowest satisfaction ratings (M = −0.175), those with semi-glossiness showed intermediate ratings (M = 0.225), and samples with low glossiness achieved the highest satisfaction ratings (M = 0.713).The pairwise comparison results with Bonferroni correction (Table 9) further indicate that the differences between high-glossiness and semi-glossiness, high glossiness and matte, as well as semi-glossiness and matte are all statistically significant (all p < 0.05). These findings suggest that older participants exhibit stable and significant hierarchical differences in visual preference across surfaces with different levels of glossiness.

Table 8.

Estimated marginal means of satisfaction ratings under different glossiness levels.

Table 9.

Pairwise comparisons of satisfaction ratings across different glossiness levels.

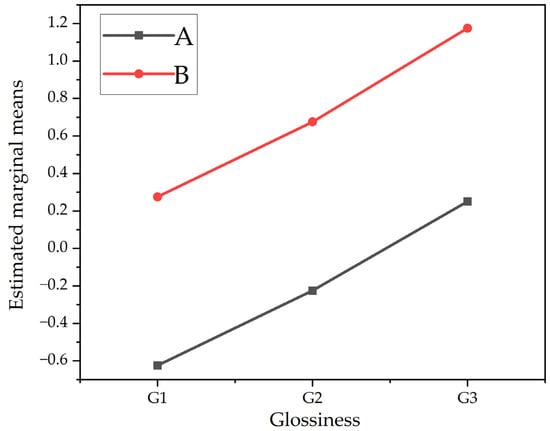

Although no significant interaction effect was found between color group and glossiness, the main effect of color group was significant, with the high-attention color group showing overall higher satisfaction ratings than the low-attention color group across all glossiness levels. An examination of the estimated marginal means for color and glossiness, together with the interaction line plot (Figure 6), shows that in both the low-attention and high-attention color groups, satisfaction ratings increase progressively as glossiness changes from high-glossiness to matte, with the two curves displaying largely consistent trends. These results suggest that older participants tend to assign higher ratings to their relatively preferred colors under all glossiness conditions, indicating that color preference primarily affects the overall level of satisfaction ratings rather than altering the preference order for different levels of glossiness.

Figure 6.

Estimated marginal means of Group A and Group B.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of PP film color and glossiness on elder visual perception and preferences using eye-tracking and questionnaire-based methods. The results indicate that color attributes and glossiness play relatively independent yet complementary roles at different stages of perception, jointly shaping elder visual experience of material surfaces. These findings provide targeted empirical evidence to inform the selection and design of age-friendly furniture materials.

4.1. Results and Analysis of the Glossiness Experiment

The results of the eye-tracking experiment revealed that red hues demonstrated a pronounced attraction, as evidenced by both first fixation duration and overall fixation metrics, indicating their ability to rapidly capture the attention of elderly participants during the nascent phase of visual processing. This observation aligns with established theories in visual psychology concerning the heightened salience of warm colors, suggesting that designers should emphasize the utilization of high-salience colors for effective information dissemination and attention guidance when designing age-friendly furniture [34]. Meanwhile, the effect of saturation on the visual perception of elderly users presented a dichotomous pattern: during the initial fixation, colors with medium saturation were more prone to attract attention, whereas in preference-related measures, low saturation showed higher acceptance. This discrepancy indicates that saturation plays different roles in initial attentional allocation and subsequent preference formation: medium saturation is more conducive to rapid stimulus recognition in the visual field, whereas low saturation is more effective in maintaining visual comfort during prolonged viewing. In terms of value, the findings indicated that medium to higher brightness levels were generally more attractive, while first fixations were more sensitive to low brightness. This could be attributed to the darkening effect of low brightness, which accentuates boundary contrast within the visual field and thereby intensifies initial attention [35]. A synthesis of the analyses across different color factors indicates that elder visual preferences tend to favor color combinations with warmer hues, lower saturation, and moderate value.

4.2. Relationship Between Elder Visual Preference and Glossiness

The results of the glossiness questionnaire indicated that elder visual preference for the glossiness of PP film surfaces exhibits a clear and stable hierarchical pattern, with matte samples showing the highest satisfaction and high-gloss samples showing the lowest satisfaction. Matte surfaces effectively mitigate glare induced by light reflection, rendering colors more subdued and stable, thereby providing a more comfortable visual experience for the elderly. Considering the common age-related conditions among elder individuals, such as lens opacification and reduced pupillary accommodation, the strong reflections produced by high-gloss surfaces are more likely to induce visual discomfort, which may be an important reason for their significantly lower satisfaction ratings. This observation is in line with previous studies, which posits that excessive glossiness can precipitate visual fatigue and perceptual discomfort [36]. Therefore, elder preference for glossiness reflects not a pursuit of strong visual stimulation, but rather a tendency toward stable and gentle visual experiences.

4.3. Combined Effects of Glossiness and Color

Although both color and glossiness showed significant main effects on elder visual preference, no significant interaction between the two was observed. This finding indicates that glossiness does not alter elders’ existing color preferences, but instead influences satisfaction by globally increasing or decreasing its overall level. Specifically, under different glossiness levels, elders consistently rated high-attention colors higher than low-attention colors, and all colors exhibited a consistent preference trend as glossiness changed, increasing from high-glossiness to matte. This suggests that color preference primarily determines elders’ relative evaluations of materials, whereas glossiness mainly affects the absolute level of these evaluations. In other words, glossiness does not operate by modulating color preference, but rather functions as an independent perceptual dimension that, together with color attributes, jointly shapes the visual experience.

This finding enriches the understanding of the mechanisms underlying the formation of elder visual preferences from a material perception perspective, indicating that in PP film applications, color selection and glossiness control can be optimized to a certain extent independently. By adopting matte surfaces while maintaining color characteristics preferred by elders, overall visual comfort can be further enhanced without compromising the advantages of color perception.

4.4. Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study systematically examined the effects of color and glossiness characteristics of PP film surfaces on elder visual preferences from a visual perception perspective, providing valuable empirical evidence for the selection and optimization of age-friendly furniture materials. However, several limitations should be acknowledged: (1) The participants in this study were primarily younger elders (aged 60–74). The applicability of the findings to older age groups or elders with pronounced visual impairments remains to be verified. Future research could expand the age range of participants to compare differences in color and glossiness perception across elder subgroups. (2) The experiments were conducted under controlled lighting conditions, whereas variations in illuminance, light source type, and color temperature in real residential environments may influence the perception of color and glossiness. Subsequent studies could incorporate multiple lighting scenarios to examine the robustness of the findings in more realistic settings. (3) This study combined a screen-based eye-tracking experiment with a subjective evaluation experiment using physical samples. While this design helps to separately reveal visual attention and material-related perceptual characteristics, differences in optical properties between the two media make direct comparison challenging. Future research could introduce eye-tracking or virtual reality techniques under physical material conditions to reduce the gap between experimental contexts and real-world applications. (4) The present study focused primarily on the visual dimension and did not include tactile feedback, duration of use, or comprehensive evaluations under real usage scenarios. Given the multisensory nature of furniture material perception, future research should incorporate multisensory measurements and long-term use experiments. (5) In the present study, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine the effects of color and gloss on visual preference. While ANOVA is appropriate for identifying overall differences among experimental conditions, it may be less effective in capturing the complex temporal characteristics of duration-based measures. Future research could consider hazard-based duration models to provide a more robust analysis of factors influencing visual attention over time.

5. Conclusions

The study focuses on the visual perception needs of age-friendly furniture surface decorative materials, examining the relationships between the color and glossiness characteristics of PP films and older users’ subjective evaluations and visual attention. Based on a systematic review and selection of PP film materials, experimental samples with varying levels of color and glossiness were developed. By integrating questionnaire-based evaluations with eye-tracking experiments, we systematically analyzed how color and glossiness influence older users’ gaze behavior, preference choices, and satisfaction ratings. This study provides insights into elderly visual preferences for furniture surface materials and is expected to offer actionable design guidelines and practical references for color configuration and process selection of PP films in age-friendly furniture, thereby promoting the application of sustainable materials in elderly living environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J. and X.C.; methodology, D.J. and X.C.; software, X.C.; validation, D.J., X.C., W.J. and Z.X.; formal analysis, D.J. and X.C.; investigation, D.J., X.C., W.J. and Z.X.; resources, D.J., X.C. and X.Y.; data curation, D.J. and X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.J. and X.C.; writing—review and editing, D.J. and X.C.; visualization, D.J., X.C., W.J. and Z.X.; supervision, D.J.; project administration, D.J.; funding acquisition, D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PP | Polypropylene |

References

- Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Zeng, X. Interpretation of the 2023 National Report on the Development of Elderly Care in China. J. Aging Rehabil. 2025, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shanat, M.b.H. Research on Design and Development of Elder-Friendly Furniture in Chinese Residential Situation. Art. Soc. 2023, 2, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almustanyir, A.; Alhazmi, M.; Aldarwesh, A.; Almutairi, M.S.; Almahubi, M.; Alateeq, A.; Alqahtani, T.; Alanazi, M.; Alotaibi, S.; Alghamdi, M.; et al. Age-Related Effects on the Color Discrimination Threshold. Life 2025, 15, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, J.E.P.; McDougall, A.; Mylonas, D.; Suarez-Gonzalez, A.; Crutch, S.J.; Warren, J.D. Pupil responses to colorfulness are selectively reduced in healthy older adults. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleury, J.; Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T.; Coon, D.W.; Komnenich, P. Feeling Safe and Nostalgia in Healthy Aging. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 843051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulker, O.C.; Ulker, O.; Hiziroglu, S. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Emitted from Coated Furniture Units. Coatings 2021, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabri, A.; Tahir, F.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Environmental impacts of polypropylene (PP) production and prospects of its recycling in the GCC region. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, W. R&D strategy study of customized furniture with film-laminated wood-based panels based on an analytic hierarchy process/quality function deployment integration approach. BioResources 2023, 18, 8249–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Cheung, V.; Westland, S.; Rhodes, P.A.; Shen, L.; Xu, L. The impact of color preference on adolescent children’s choice of furniture. Color Res. Appl. 2020, 45, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Xu, J.; Dong, H. Design preferences for contemporary Chinese-style wooden furniture: Insights from conjoint analysis. BioResources 2024, 20, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, H. Assessing Consumer Attention and Arousal Using Eye-Tracking Technology in Virtual Retail Environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 665658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, E.; Berti, D.; Ranfagni, S.; Hernández-Álvarez, L.; Bernetti, I. Wine label design proposals: An eye-tracking study to analyze consumers’ visual attention and preferences. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2023, 35, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, S.; Geng, X. Simultaneous multimodal measures for aesthetic evaluation of furniture color and form. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Goda, N. Neural Mechanisms of Material Perception: Quest on Shitsukan. Neuroscience 2018, 392, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.Y.; Suh, J. Spatial Color Efficacy in Perceived Luxury and Preference to Stay: An Eye-Tracking Study of Retail Interior Environment. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Mahmoud, N.S.A.; El Samanoudy, G.; Al Qassimi, N. Evaluating the Color Preferences for Elderly Depression in the United Arab Emirates. Buildings 2022, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuszynska-Bogucka, W.; Kwiatkowski, B.; Chmielewska, M.; Dzienkowski, M.; Kocki, W.; Pelka, J.; Przesmycka, N.; Bogucki, J.; Galkowski, D. The effects of interior design on wellness—Eye tracking analysis in determining emotional experience of architectural space. A survey on a group of volunteers from the Lublin Region, Eastern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, H.; Nakauchi, S.; Minami, T. Glossiness perception and its pupillary response. Vis. Res. 2024, 219, 108393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheaux, C.; Zimmermann, E.; Gazel, M.; Delanoy, J.; Raimbaud, P.; Lavoue, G. Effect of material properties on emotion: A virtual reality study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1301891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honson, V.; Huynh-Thu, Q.; Arnison, M.; Monaghan, D.; Isherwood, Z.J.; Kim, J. Effects of Shape, Roughness and Gloss on the Perceived Reflectance of Colored Surfaces. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Akbarinia, A.; Storrs, K.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Smithson, H.E.; Gegenfurtner, K.R.; Fleming, R.W. Color and gloss constancy under diverse lighting environments. J. Vis. 2023, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X. Investigation on Decorative Materials for Wardrobe Surfaces with Visual and Tactile Emotional Experience. Coatings 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.W. Material Perception. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2017, 3, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levoy, M.; Ginsberg, J.; Shade, J.; Fulk, D.; Pulli, K.; Curless, B.; Rusinkiewicz, S.; Koller, D.; Pereira, L.; Ginzton, M.; et al. The digital Michelangelo project. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques—SIGGRAPH, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–28 July 2000; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos, S.; Sawides, L.; Gambra, E.; Dorronsoro, C. Influence of adaptive-optics ocular aberration correction on visual acuity at different luminances and contrast polarities. J. Vis. 2008, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.C.; Kentridge, R.W. The perception of gloss: A review. Vis. Res. 2015, 109, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyoshi, I.; Nishida, S.; Sharan, L.; Adelson, E.H. Image statistics and the perception of surface qualities. Nature 2007, 447, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, N.; Holiel, A.A. Color difference for shade determination with visual and instrumental methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, L.; Oberfeld, D. Color and emotion: Effects of hue, saturation, and brightness. Psychol. Res. 2018, 82, 896–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhang, G.; Ma, L.; Silvennoinen, J.; Cong, F. Comparative analysis of color emotional perception in art and non-art university students: Hue, saturation, and brightness effects in the Munsell color system. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, K.B.; Palmer, S.E. Aesthetic response to color combinations: Preference, harmony, and similarity. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2011, 73, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camgöz, N.; Yener, C.; Güvenç, D. Effects of hue, saturation, and brightness on preference. Color Res. Appl. 2002, 27, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.C.; Luo, M.R.; Woodcock, A.; Wright, A. A study of colour emotion and colour preference. Part I: Colour emotions for single colours. Color Res. Appl. 2004, 29, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, C. Elderly-Centric Chromatics: Unraveling the Color Preferences and Visual Needs of the Elderly in Smart APP Interfaces. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhauser, W.; Konig, P. Does luminance-contrast contribute to a saliency map for overt visual attention? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003, 17, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, M.C.; Andrén, B. Effect of gloss and diffuse reflectance of display frames on visual comfort. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2012, 15, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.